Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 33

October 11, 2021

Better Ways to Cut Healthcare Waste

This video was adapted from a column Austin wrote for the Upshot. Links to sources can be found there.

The post Better Ways to Cut Healthcare Waste first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

October 7, 2021

Can medical scribes help increase access to care for veterans?

Paul Shafer is an assistant professor of health law, policy, and management at the Boston University School of Public Health and tweets at @shaferpr. Alex Woodruff is a Health Science Specialist at the Boston VA Healthcare System and tweets at @aewoodru. Both are members of the evaluation team for the MISSION Act scribes pilot described in this article.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health system in the United States serving over 9 million Veterans each year, though access to care is a persistent concern.

Electronic medical record systems were supposed to make health care more efficient and portable, but they have doctors spending a lot of time staring at screens—leading to burnout and less attention on patients. What happens when we give doctors more time to focus on their patients?

What are medical scribes and how can they help?

According to a 2016 study, providers in ambulatory care spend about half on administrative tasks (49.2%), including more than one-third of their time in the exam room with patients (37.0%). A newer study from 2020 estimated that physicians spend an average of over 16 minutes in the EHR per patient visit.

Medical scribes join doctors, nurses, and other providers in patient visits to help ease administrative burdens on providers by documenting visits and entering orders, allowing the provider to spend more time focusing on the patient instead of the electronic health record.

By shifting some of that administrative time away from the provider, scribes ideally allow them to be more present with patients and potentially see more of them without compromising quality of care.

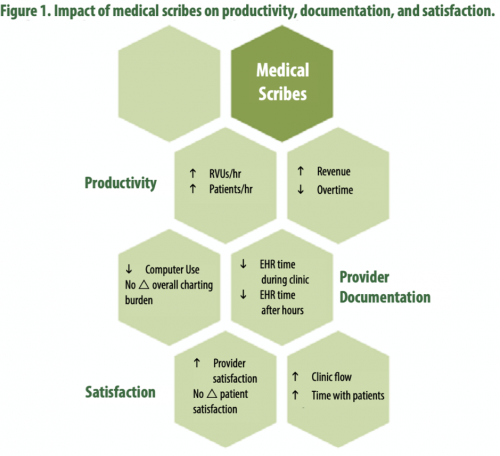

Scribes have not been used widely in the VHA before but have been deployed (and studied) in community hospitals and clinics, both in the United States and worldwide. A 2018 VHA policy brief highlighted promising associations found in scribe evaluations thus far (Figure 1), including increased productivity, reduced documentation time, and greater provider satisfaction with no effect on patient satisfaction.

However, a robust systematic review of the effect of medical scribes used in emergency departments, cardiology, and orthopedics, completed last year by VHA found relatively poor strength of methods and evidence in evaluating potential effects of clinic efficiency, productivity, and patient and/or provider satisfaction. None of the studies that either report cites took place in the VHA, which means those results may not be generalizable to the VHA even if the strength of evidence concerns were not a significant problem.

Source: Pearson, Frakt, and Pizer, 2018. Reprinted with permission.

What is VHA doing?

Section 507 of the MISSION Act of 2018 required VHA to “carry out a 2-year pilot program under which the Secretary shall increase the use of medical scribes”. The evaluation team, comprising multiple Centers and Offices at VHA, designed a cluster randomized trial around the requirements of the law to generate causal evidence of the effect of medical scribes. The pilot includes the hiring of 48 medical scribes across 12 facilities. These facilities include four urban, four rural and two underserved facilities that were randomly selected among a pool of interested VA Medical Centers.

Thirty percent of the scribes are allocated to emergency departments and seventy percent to the high wait time specialties of cardiology and orthopedics. Each medical facility is supposed to hire four scribes, two as VHA employees and two as contractors, with an eye towards how to scale this up if the results are promising.

As the study continues, the impact of medical scribes will be observed across a number of outcomes — evaluated quantitatively to see how scribes affect productivity, wait times, etc., but also qualitatively to provide needed context to what the data do and do not tell us. The goal is to see if deploying scribes can improve productivity and reduce wait times without compromising patients’ satisfaction with their care. This would provide a proof of concept in the VHA before any decision is made about a larger investment.

Early Implementation

The implementation of the MISSION 507 program has not been without turbulence. The official study launch, originally planned for March 2020, was delayed because of COVID-19, finally beginning in late June 2020. Scribes began to be hired well before the official pilot start date but despite the early start, hiring has fallen well short of its targets. Almost half of the scribe positions are vacant.

Hiring scribes as contractors has been much more successful than as employees to date, although their onboarding time is nearly 50% longer. These difficulties tell two important stories—1) with fewer scribes than expected, it may be more difficult to detect any real benefits (or harms) and 2) this raises concerns about the ability to scale the intervention, if the pilot proves to be successful.

What’s next?

Implementing a new wrinkle to health care delivery is never an easy task, even in a large integrated health care system. Expanding facilities and hiring more providers are easy solutions to point to, but harder to do. Scribes could be a lower cost way to expand access by preserving one of the most valuable resources that we have—face-to-face time between providers and their patients.

The MISSION 507 scribe pilot is approximately halfway done and to date, implementation challenges have been the most observable outcome. This trial holds a lot of promise for learning whether scribes really are a potential avenue for increasing access to care for veterans, time will tell if evidence supports that promise.

The post Can medical scribes help increase access to care for veterans? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 6, 2021

Using e-values to strengthen inferences from observational vaccine data

Melissa Garrido, PhD is the Associate Director of the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center (PEPReC) at the Boston VA Healthcare System, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and a Research Associate Professor with the Department of Health Law, Policy, and Management at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @GarridoMelissa.

In the New England Journal of Medicine, Yinon Bar-On and colleagues describe the ability of a third dose of the BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) to protect against severe illness and cases of Covid-19 in adults 60 or older, relative to receipt of a two-dose regimen. Although Bar-On et al.’s study leverages a unique population-level dataset, the study was observational — individuals were not randomized to receipt of the booster. As a result, unobserved variables associated with likelihood of both receiving a booster and infection, such as occupation or concern about COVID, may at least partially explain the findings.

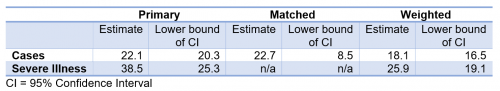

To strengthen our ability to act upon observational data, we can use e-values. E-values characterize the degree of unobserved confounding that would need to exist before we change our inferences from an analysis. The table below includes e-values for the primary, matched, and weighted effect estimates and for the lower bounds of the confidence intervals from Bar-On et al.’s study.

Table. E-values for Bar-On et al.’s study of BNT162b2 third dose effectiveness

In the matched analysis, which most carefully controls for time of booster receipt, the e-value for the cases’ confidence interval lower bound is 8.5. This means that for the cases’ confidence interval to include a value of 1 (indicating no evidence of booster impact), this sample would need to include unobserved variables that are associated with both 8.5 times the likelihood of booster receipt and 8.5 times reduction in becoming infected, after controlling for the variables Bar-On et al. used.

Elsewhere, surveys of vaccine attitudes suggest a relationship between greater perceptions of Covid-19 risk and greater willingness to be vaccinated. Perceived Covid-19 risk may also lead individuals to reduce participation in activities that include a high chance of transmission. The degree to which these relationships exist in decisions about boosters and are possible confounding factors in observational studies of booster effectiveness should be clarified and acknowledged as longer-term outcomes are monitored.

The post Using e-values to strengthen inferences from observational vaccine data first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 4, 2021

Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: October 2021 Edition

Below are recent publications from me and my colleagues from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. You can find all posts in this series here.

October 2021 Edition

Bhanja, A, Lee D, Gordon SH, Allen H, Sommers BD. Comparison of Income Eligibility for Medicaid vs Marketplace Coverage for Insurance Enrollment Among Low-Income US Adults. JAMA Health Forum. 2021; 6(2):e210771. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0771.

Avoundjian T, Troszak L, Cave S, Shimada S, McInnes K, Midboe AM. Correlates of personal health record registration and utilization among veterans with HIV. JAMIA Open. 2021 Apr; 4(2):ooab029. PMID: 34278241.

Belok SH, Bosch NA, Klings ES, Walkey AJ. Evaluation of leukopenia during sepsis as a marker of sepsis-defining organ dysfunction. PLoS One. 2021; 16(6):e0252206. PMID: 34166406.

Biondi BE, Anderson BJ, Phillips KT, Stein M. Sex Differences in Injection Drug Risk Behaviors Among Hospitalized Persons. J Addict Med. 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34282080.

Cahill SR, Wang TM, Fontenot HB, Geffen SR, Conron KJ, Mayer KH, Johns MM, Avripas SA, Michaels S, Dunville R. Perspectives on Sexual Health, Sexual Health Education, and HIV Prevention From Adolescent (13-18 Years) Sexual Minority Males. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021 Jun 19. PMID: 34154868.

Calhoun Thielen C, Slavin MD, Ni P, Mulcahey MJ. Development and initial validation of ability levels to interpret pediatric spinal cord injury activity measure and pediatric measure of participation scores. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2021 Jul 03. PMID: 34250956.

Cohen AB. 2020-The Year of Living Dangerously in a COVID-19 World. Milbank Q. 2021 06; 99(2):333-339. PMID: 34185919.

Damschroder LJ, Knighton AJ, Griese E, Greene SM, Lozano P, Kilbourne AM, Buist DSM, Crotty K, Elwy AR, Fleisher LA, Gonzales R, Huebschmann AG, Limper HM, Ramalingam NS, Wilemon K, Ho PM, Helfrichfcr CD. Recommendations for strengthening the role of embedded researchers to accelerate implementation in health systems: Findings from a state-of-the-art (SOTA) conference workgroup. Healthc (Amst). 2021 Jun; 8 Suppl 1:100455. PMID: 34175093.

Elwy AR, Maguire EM, McCullough M, George J, Bokhour BG, Durfee JM, Martinello RA, Wagner TH, Asch SM, Gifford AL, Gallagher TH, Walker Y, Sharpe VA, Geppert C, Holodniy M, West G. From implementation to sustainment: A large-scale adverse event disclosure support program generated through embedded research in the Veterans Health Administration. Healthc (Amst). 2021 Jun; 8 Suppl 1:100496. PMID: 34175102.

Jette AM. Reflections on the Wisdom of Profession-Specific Diagnostic Labels. Phys Ther. 2021 Jun 01; 101(6). PMID: 34157121.

Levengood TW, Yoon GH, Davoust MJ, Ogden SN, Marshall BDL, Cahill SR, Bazzi AR. Supervised Injection Facilities as Harm Reduction: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2021 Jul 01. PMID: 34218964.

Marc LG, Goldhammer H, Mayer KH, Cahill S, Massaquoi M, Nortrup E, Cohen SM, Psihopaidas DA, Carney JT, Keuroghlian AS. Rapid Implementation of Evidence-Informed Interventions to Improve HIV Health Outcomes Among Priority Populations: The E2i Initiative. Public Health Rep. 2021 Jun 29; 333549211027849. PMID: 34185594.

McInnes DK, Troszak LK, Fincke BG, Shwartz M, Midboe AM, Gifford AL, Dunlap S, Byrne T. Is the Availability of Direct-Acting Antivirals Associated with Increased Access to Hepatitis C Treatment for Homeless and Unstably Housed Veterans? J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Jun 25. PMID: 34173193.

Morgan JR, Quinn EK, Chaisson CE, Ciemins E, Stempniewicz N, White LF, Larochelle MR. Potential barriers to filling buprenorphine and naltrexone prescriptions among a retrospective cohort of individuals with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021 Jun 17; 108540. PMID: 34148756.

Outterson K, Orubu ESF, Rex J, Årdal C, Zaman MH. Patient access in fourteen high-income countries to new antibacterials approved by the FDA, EMA, PMDA, or Health Canada, 2010-2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jul 12. PMID: 34251436.

Pimentel CB, Clark V, Baughman AW, Berlowitz DR, Davila H, Mills WL, Mohr DC, Sullivan JL, Hartmann CW. Health Care Providers and the Public Reporting of Nursing Home Quality in the United States Department of Veterans Affairs: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021 Jul 21; 10(7):e23516. PMID: 34287218.

Rencken CA, Rodríguez-Mercedes SL, Patel KF, Grant GG, Kinney EM, Sheridan RL, Brady KJS, Palmieri TL, Warner PM, Fabia RB, Schneider JC, Stoddard FJ, Kazis LE, Ryan CM. Development of the School-Aged Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (SA-LIBRE5-12) Profile: A Conceptual Framework. J Burn Care Res. 2021 Jun 11. PMID: 34228121.

Trangenstein PJ, Peddireddy SR, Cook WK, Rossheim ME, Monteiro MG, Jernigan DH. Alcohol Policy Scores and Alcohol-Attributable Homicide Rates in 150 Countries. Am J Prev Med. 2021 Jul 03. PMID: 34229927.

Tripathi S, Christison AL, Levy E, McGravery J, Tekin A, Bolliger D, Kumar VK, Bansal V, Chiotos K, Gist KM, Dapul HR, Bhalala US, Gharpure VP, Heneghan JA, Gupta N, Bjornstad EC, Montgomery VL, Walkey A, Kashyap R, Arteaga GM. The Impact of Obesity on Disease Severity and Outcomes Among Hospitalized Children with COVID-19. Hosp Pediatr. 2021 Jun 24. PMID: 34168067.

Vashi AA, Orvek EA, Tuepker A, Jackson GL, Amrhein A, Cole B, Asch SM, Gifford AL, Lindquist J, Marshall NJ, Newell S, Smigelsky MA, White BS, White LK, Cutrona SL. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Innovators Network: Evaluation design, methods and lessons learned through an embedded research approach. Healthc (Amst). 2021 Jun; 8 Suppl 1:100477. PMID: 34175094.

Walkey AJ, Law A, Bosch NA. Lottery-Based Incentive in Ohio and COVID-19 Vaccination Rates. JAMA. 2021 Jul 02. PMID: 34213530.

The post Recent publications from Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management: October 2021 Edition first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 27, 2021

Mask Promotion and Covid Prevention

Mask-wearing is one of a set of measures that helps slow the spread of respiratory disease. This is particularly important in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, but mask uptake has been low in some areas. In today’s episode we discuss a recent study that examines strategies to successfully increase mask usage, and how that increase affects the spread of Covid-19.

The post Mask Promotion and Covid Prevention first appeared on The Incidental Economist.

September 20, 2021

How Comfortable are Veterans Disclosing Their Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity?

Izabela Sadej, MSW, is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. She tweets at @IzzySadej.

There is a long history of discrimination against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) individuals serving in the U.S. military. Until September 2011, the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy prohibited active-duty personnel from being asked about or discussing their sexual orientation for fear of retaliation and possible discharge. After former President Donald Trump banned transgender individuals from serving in the military, the U.S. Department of Defense updated their guidance to prohibit discrimination based on gender identity, particularly transgender identity, in March 2021.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) does not routinely collect or document sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) information from Veterans, despite known physical and mental health disparities among both sexual and gender minority individuals and the Veteran population. The intersection of these two identities, especially considering the military’s treatment of this group, has resulted in questions about reluctancy among sexual and gender minority Veterans discussing SOGI information in VHA settings.

New Research

A recent study explored Veteran’s comfort in disclosing and responding to questions about SOGI information, particularly when asked 1) on VHA surveys and 2) in clinical discussions with VHA providers.

(Affiliations of the authors for this study include Mollie A. Ruben at the University of Maine Department of Psychology and the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research at VA Boston Healthcare System; Michael R. Kauth at VHA LGBT Health Program, South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Baylor College of Medicine Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and VA Houston HRS&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety; Mark Meterko at VHA RAPID SHEP Patient Experience Survey Program and Boston University School of Health Law, Policy and Management; Andrea M Norton at the Aleda E. Lutz Veteran Affairs Medical Center; Alexis R. Matza at VHA LGBT Health Program and Boston VA Research Institute Inc; and Jillian C. Shipherd at VHA LGBT Health Program, VA Boston Healthcare System National Center for PTSD, and Boston University School of Medicine.)

An online survey was administered to the Veteran Insights Panel (VIP), a group of Veterans who have voluntarily agreed to provide feedback to VHA for improvement purposes. VIP participants are of various ages, gender identities, sexual orientations, races, and ethnicities. The researchers contacted 3255 Veterans and received 806 responses. The study’s sample population is said to be representative of the general Veteran population, with slightly more representation of older age groups.

The survey included multiple-choice style questions to identify four sociodemographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, sex assigned at birth, and sexual orientation) of participants, followed by questions concerning their comfort level in responding to SOGI- and race/ethnicity-related questions on VHA confidential surveys and in discussion with VHA providers. Participants rated their comfort in reporting their identity characteristics on a 5-point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

Descriptive statistics were used to quantify patient perceptions of answering SOGI and race/ethnicity questions. Stratified analyses (independent samples t-tests and analysis of variance) examined differences in comfort answering SOGI and racial/ethnic identifying questions across sociodemographic groups. Paired samples t-tests examined differences in comfort between a confidential VHA survey and clinical interactions with VHA providers.

Findings

With average scores ranging from 4.20–4.35 on the 1-5 scale, participants generally reported favorable perceptions answering SOGI questions on both confidential VHA surveys and in discussion with their VHA providers. There was a slight preference for in-person discussion versus a survey. Some additional findings are below.

Reporting on a VHA Confidential Survey:By gender expression: In comparison to gender-diverse participants, cisgender men and women reported feeling more comfortable sharing their identity across all characteristics, except race/ethnicity.By sex at birth: Female-born participants were significantly more comfortable reporting their sexual orientation and race/ethnicity than male-born participants.By sexual orientation: Compared to sexual and gender minority participants, heterosexual participants were significantly more comfortable reporting their sexual orientation, gender identity, and birth sex, and marginally more comfortable reporting their race/ethnicity.In Discussion with a VHA Provider:By gender expression: Cisgender men and women were more likely to feel comfortable discussing their identities with VHA providers compared to gender-diverse Veterans.By sex at birth: Male- and female-born participants did not differ significantly in their comfort levels.By sexual orientation: Heterosexual participants, when compared with sexual and gender minority participants, were significantly more comfortable discussing their sexual orientation, gender identity, and birth sex, and marginally more comfortable discussing their race/ethnicity.An unexpected finding showed that disclosing race/ethnicity on a confidential VHA survey had the lowest comfort rating among participants (lower than disclosing SOGI information). Participants who identified as multiracial or “other” reported significantly less favorable perceptions reporting race/ethnicity on a survey or with providers compared with all other racial identities. Black participants reported less favorable perceptions of reporting race/ethnicity on a survey compared with White participants, while Native American participants reported significantly less favorable perceptions reporting race/ethnicity in discussion with providers compared with White participants.

Limitations to this study include a small number of sexual and gender minority participants, particularly those that are gender-diverse, which hindered the ability to examine the intersection of SOGI identities and race/ethnicity. Additionally, there is a possibility of selection bias and/or response bias among both VIP participants in general and study participants, with the possibility that participation in either favors those who are more comfortable discussing their identities. A more qualitative and/or observational approach would allow for gaining a better understanding of other factors that could impact Veterans’ comfort in discussing identity characteristics.

Conclusions

While participants were generally comfortable discussing their SOGI identities on VHA surveys and with VHA providers, cisgender and heterosexual participants were significantly more comfortable compared with sexual and gender minority participants. The unexpected observation that participants were less comfortable reporting their race/ethnicity on a VHA survey indicates that there is more work to be done to better identify and understand how Veterans’ identities intersect.

Understanding Veterans’ comfort in disclosing all types of sociodemographic information in VHA settings is essential to improving providers’ abilities to deliver appropriate care. Practices such as electronic health record modernization can aid in the collection of SOGI information and identifying health disparities among sexual and gender minority patients. This is well needed, as the trickle-down effects of discriminatory practices during military service can still be felt by the Veteran community.

The post How Comfortable are Veterans Disclosing Their Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Does giving money to people with substance use disorder ‘enable’ them? It’s complicated.

Alex Woodruff is a health science specialist at VA Boston Healthcare System and the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center. He tweets at @aewoodru

Our lexicon is full of phrases that justify cutting-off financial support to people who use drugs. Phrases like “they’ll just go spend it on drugs” and “enabling” are a mainstay in the public conversation about addiction. But the evidence surrounding substance use and spending tells a more complex story. Financially disenfranchising people who use drugs can drive high risk behaviors, hinder access to necessities, and perpetuate a cycle of poverty that can be an anchor for people with addiction.

In this Boston Globe article, I address the historical mindset that financially supporting people who use drugs will enable their drug use and challenge the multitude of ways that this “tough love” approach is integrated into the way we treat people with addiction. Most importantly I discuss the hurt this causes for families, communities, and people with addiction that are searching for a way to help.

Check out the full article here.

Alex Woodruff’s research is supported by Arnold Ventures

The post Does giving money to people with substance use disorder ‘enable’ them? It’s complicated. first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 17, 2021

Finally, A Randomized Trial of Mask Wearing

Paul Shafer is an assistant professor of Health Law, Policy, and Management at the Boston University School of Public Health. He tweets @shaferpr.

A recent article I published in Tradeoffs looks at a recent working paper of a randomized intervention designed to increase mask wearing in rural Bangladesh. Given that COVID-19 cases are back on the rise and vaccination rates remain low, I also discuss what these findings might mean for the United States.

In it, I write:

The study also weighed in on two other hotly debated questions about masks. First, the intervention increased physical distancing by 5 percentage points (24.1% versus 29.2%), countering concerns that increased mask wearing may lead to more risky social behavior. Second, the study provided suggestive evidence that surgical masks may be more effective in the real world at reducing COVID-19 spread than cloth masks, building upon prior lab-based studies.

Read the full piece at Tradeoffs!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Finally, A Randomized Trial of Mask Wearing first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 16, 2021

Diabetes Management – Is Medicare Advantage really Advantageous?

Stuart Figueroa, MSW, is a policy analyst at Boston University School of Public Health. He tweets at @RealStuTweets.

Turn on the TV to your favorite mid-day programming and there is a good chance you’ll see Joe Namath gracing the screen, selling Medicare Advantage. Far removed from gridiron glory with the New York Jets, 78-year-old Namath is less ‘Broadway Joe’, and a little more Medicare Joe. The question begs – what exactly is he selling and who actually benefits?

Background on Medicare Advantage

Medicare Advantage, also known as Medicare Part C, is a program that allows Medicare eligible beneficiaries to enroll in health plans offered by private insurers. These plans contract with Medicare and receive a capitated payment based on enrollment. Aside from its payment structure, MA differs from traditional Medicare (TM) in several important ways.

First, MA enrollees tend to have fewer health care provider options; this differs substantially from TM beneficiaries who have access to a broader network. From a benefits standpoint though, many MA plans offer more expansive benefits. For example, plans may include dental coverage, audiology, and other perks such as fitness programs and gym memberships. There are also significant differences when it comes to enrollee cost burden. In particular, MA plans cap out-of-pocket costs; such a cap does not exist under traditional Medicare.

As of June 2021, more than 26 million persons, approximately 42 percent of all Medicare enrollees, were enrolled in MA plans. Current enrollment projections anticipate that the proportion of beneficiaries participating in MA plans will increase to nearly 50% of all enrollees by 2029. Recent growth in MA enrollment has been disproportionately higher among racial/ethnic minorities and other traditionally marginalized groups, though the reasons why are not entirely clear.

But how do the two differ in treating chronic disease? And how about across racial and ethnic subpopulations? As the nation’s population ages, there is an urgent need to understand how well MA serves beneficiaries with chronic disease, and whether MA participation translates into improved disease management and health outcomes when compared to traditional Medicare.

Background on Diabetes

Let’s take diabetes. It is estimated that one in four dollars spent on health care is spent on diabetes related costs. Diabetes is a progressive disease that if untreated or mismanaged leads to serious complications such as stroke, cardiovascular disease, nerve issues, and kidney and liver problems. The risk of developing diabetes and experiencing complications increases dramatically with age, and those affected by the disease and its comorbid conditions are likely to require escalated care including more frequent and longer hospitalizations, increased outpatient care, and prescriptions.

Health Disparities in Diabetes Management

Racial and ethnic health disparities have been found to exist both between different MA plans and between TM and MA. Studies have documented differences in the management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose, as well as hospital readmission following complications from surgery. When it comes to diabetes management, it is difficult but important to ascertain the extent that racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes exist in MA.

In TM, numerous studies have explored the racial and ethnic health disparities associated with diabetes. Early studies found that, even as TM improved preventative care practices overall, non-White beneficiaries, especially Black beneficiaries, were less likely to receive preventative services. This resulted in a higher likelihood of both short- and long-term complications.

A 2019 study in Health Equity found that among traditional Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes, Hispanic beneficiaries fared significantly poorer across a number of health metrics when compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts. The economic manifestation of this disparity was increased costs, utilization of acute care, and longer inpatient hospitalizations.

When considering the long arc of diabetes management under MA, the results are mixed. When the MA program was still in its infancy, many of the same issues found in TM were prevalent in MA. A 2007 study examining racial and gender differences on process of care and intermediate outcome measures (e.g., A1C screenings, cholesterol screenings, eye exams) found that, when compared to White beneficiaries, Black MA enrollees consistently fared poorer on five of six measures. This disparate performance relative to race and ethnicity and diabetes outcomes has been observed repeatedly. Complicating the picture further, MA plans are not created equal and significant variation in outcomes has been found both between and within plans.

More recent efforts comparing diabetes management more broadly between MA to TM have found improvements in the quality of diabetes care as well as reduced costs for MA beneficiaries. Studies found decreased utilization of diabetes services in MA health plans, as well as higher quality of care than in TM. In addition, MA plans tend to manage diabetes care with less expensive medications than TM, resulting in lower out-of-pocket costs for enrollees. (Caveat: as with all studies of MA, there’s a thorny issue of the extent to which beneficiary risk is adequately controlled for or reflects coding differences between MA and TM or in MA over time.)

Looking at diabetes care as a whole, MA would appear to be trending in the right direction. It is not clear, however, that the racial and ethnic health disparities previously identified have been eliminated.

Conclusion

Medicare Advantage has its…advantages. It reduces enrollees’ costs while offering greater benefits, and recent studies show improved quality, at least for diabetes management. These are among the arguments used by private health plans who are looking to expand their MA lines of business.

However, traditionally underserved populations continue to lag behind White beneficiaries in both care and access. As is the case with almost every facet of the healthcare system, MA plans still have a lot of work to do in addressing health equity. For this reason, non-White beneficiaries will want to evaluate their MA options carefully before taking Medicare Joe at his word.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Diabetes Management – Is Medicare Advantage really Advantageous? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.September 11, 2021

20 Years Since 9/11: Why the U.S. Should Vaccinate the World

Earlier this week, David States and I argued that the U.S. should lead the developed nations in a program to immunize the entire human population. The Washington Post reported that President Biden is expected to call for a global vaccine summit conference.

David and I wrote that we should do this because it would save many lives. Perhaps this is all that needs to be said. We also argued that the U.S. stood to benefit if we could substantially reduce the number of global covid cases. This would reduce U.S. coronavirus exposure and slow the rate of evolution of new coronavirus variants. The economic cost to the U.S. of a more severe pandemic could easily be greater than the cost of making and distributing the vaccine. If so, the global vaccination effort would pay for itself.

There is, however, another moral argument for global vaccination, this one tied to 9/11 and the ensuing global war on terror. Since 9/11, the U.S. has engaged in 20 years of warfare in countries across the world.

A member of the former Afghan Special Forces.

The consequences of that war have been catastrophic. According to the Watson Institute at Brown University,

At least 801,000 people have been killed by direct war violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, and Pakistan… The U.S. post-9/11 wars have forcibly displaced at least 38 million people in and from Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, the Philippines, Libya, and Syria. This number exceeds the total displaced by every war since 1900, except World War II.

Of course, much of that violence was committed by al-Qaeda, ISIS, or the Syrian government. Some of the civil wars that have followed 9/11 might have happened anyway. Nevertheless, Americans failed to limit their 9/11 response to the specific individuals who carried out the attacks. This was a principal cause of the ensuing death and displacements.

So now, the U.S. is known not only for baseball and democracy but also for drone strikes and torture. If we led an effort to vaccinate the world, it would be one of the largest humanitarian actions in history. We should do this to set an example and balance the effects of the global war on terror.

The post 20 Years Since 9/11: Why the U.S. Should Vaccinate the World first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers