Aaron E. Carroll's Blog, page 21

November 8, 2022

A Polio Case in the United States. What Does it Mean?

A vaccine-derived polio case was reported in the United States recently, despite the fact that the polio vaccine effectively eradicated polio in the US decades ago. What is polio exactly? How did a polio case crop up in the US and what is vaccine-derived polio? What does this mean for future community spread?

The post A Polio Case in the United States. What Does it Mean? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.November 7, 2022

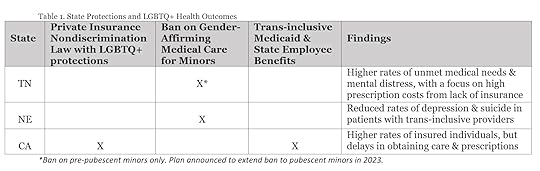

Analyzing LGBTQ+ Health Outcomes from Health Care Discrimination

Health care discrimination is not new, and the negative health impacts are well documented for some minority groups in the United States, especially Black, Indigenous and People of Color communities. While health care discrimination is also common against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and other identified (LGBTQ+) individuals, the consequences are less clear.

Expectedly, there is significant evidence of health care discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community. A national study found that, in the past year, 47% of LGBTQ+ respondents were refused care from a provider and more than 20% were denied insurance coverage on gender-affirming care (e.g., hormone therapy, reconstructive surgeries).

What’s more, different states have different protections for LGBTQ+ individuals against health care discrimination. Given the diversity, I was curious to see if health outcomes also differed from state to state. Below is the research I found. Surprisingly, there isn’t much available.

Tennessee (TN): Minimal Protections

Laws

TN remains one of 27 states where there are no LGBTQ+ inclusive insurance protections. Additionally, state Medicaid policy and state employee benefits have explicitly excluded gender-affirming care and coverage since at least 2014. There also exists a recent for pre-pubescent minors, and State Senate and House leaders plan to expand it to include pubescent minors in their first bill of 2023.

Evidence of Health Outcomes

One study from 2021 found that LGBTQ+ Nashvillians were more likely to report unmet medical needs and repeated mental distress than their non-LGBTQ+ peers, due in large part to high prescription costs from being uninsured.

Nebraska (NE): Partial Protections

Laws

44% of Americans live in states without nondiscrimination protections and NE is one of them. While NE does not ban hormone treatment for minors, it has explicitly excluded it and gender-affirming surgery for state employees and those eligible for Medicaid since at least 2014.

Evidence of Health Outcomes

A 2016 study of over 400 Nebraskans found reduced rates of depression and suicide in transgender and gender non-conforming patients who had trans-inclusive health care providers. This mirrors national trends as well.

California (CA): Full Protections

Laws

Having the most legal protections, CA explicitly prohibits insurance discrimination, covers gender-affirming surgery and hormone therapy, and is the only sanctuary state for minors seeking gender-affirming medical care.

Evidence of Health Outcomes

This year, the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research found that although LGBTQ+ Californians are now insured as much as or more than their non-LGBTQ+ peers, there are still delays in accessing prescriptions and care.

Implications

Surprisingly, the data above is all I could find on health care discrimination and health outcomes for LGBTQ+ individuals. Given the significant research on barriers to health care and the resulting physical and mental health disparities among other minority groups (e.g., higher rates of illness and death across various conditions), I expected to find more.

Even more surprising, there were no studies to report on health outcomes in the most restrictive states (e.g. Arkansas, Arizona), nor in Alabama where gender-affirming medical care for minors is considered a felony crime.

Despite the minimal data available on impact, we do have enough evidence that health care discrimination exists within the LGBTQ+ community and that is enough to try to stop it.

At the federal level, the Department of Health and Human Services is currently trying to update the Affordable Care Act to include nondiscrimination protections for sexual orientation and gender identity. It’s not finalized yet though, as public comment in the upcoming months will determine whether this revision is adopted.

At the state level, the midterm elections will present another opportunity to address LGBTQ+ inclusive health care, as several candidates are running based on their opposition to it.

In Florida, the Governor seeking reelection is currently working with the Florida Board of Medicine to ban puberty blockers, hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery for minors.In Texas, the Governor seeking reelection has directed the state to conduct child-abuse investigations on parents providing gender-affirming care to their LGBTQ+ children.In Pennsylvania, some Governor and Senate candidates have platforms that incorporate openly supporting conversion therapy.Plus, on the ballot in Nevada is a question asking voters whether or not their state should guarantee equal rights based on sexual orientation and gender .

While evidence is still thin on the health outcomes associated with health care discrimination against LGBTQ+ patients, there’s plenty to indicate that health care discrimination is happening. And plenty to vote on at the polls tomorrow.

The post Analyzing LGBTQ+ Health Outcomes from Health Care Discrimination first appeared on The Incidental Economist.November 2, 2022

Prison health care is only available if you can afford it

Often, people who are incarcerated are required to pay a co-pay for medical care that they initiate. While the cost of this co-pay may appear low, it can have high human costs, especially if it means that individuals ultimately delay seeking care. In a recent piece for Prism Reports, I talk about prison co-pays and the impact that they can have on people who are incarcerated, particularly for women and people of color:

These risks become even higher for marginalized people in carceral facilities, who tend to be Black, Latinx, and other people of color, often in poorer health than the general population, and part of a rapidly aging population that needs more specialized care. For many advocates, the removal of medical copays in prison is about more than affected individuals—it’s also about moving toward equity and justice within the carceral system.

Read the full piece, here!

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Prison health care is only available if you can afford it first appeared on The Incidental Economist.November 1, 2022

President Biden’s Executive Order isn’t enough to end Conversion Therapy

Content Warning: Sensitive topics are discussed throughout this article, including suicide.

This summer, President Biden signed an executive order to prohibit federally-funded programs from offering conversion therapy, an ineffective and unethical practice to change an individual’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity. While an important political statement, it’s likely not enough to end the practice altogether. Forward progress will only happen with legal and regulatory changes at both the national and local levels.

Originating in 1973, conversion therapy became an umbrella term to describe any psychological, physical or spiritual intervention aimed at converting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, and other identities (LGBTQ+) to traditional heterosexual and cisgender norms. Practices range from talk therapy and prayer to physical violence and exorcisms.

In the decades since its inception, conversion therapy has impacted nearly 700,000 individuals in the United States (US), with 350,000 of them subjected as minors. While estimates range considerably, tens or even hundreds of thousands of LGBTQ+ youth are currently at risk of receiving conversion therapy by religious leaders or licensed professionals.

It is well-documented that conversion therapy is ineffective, but mounting evidence indicates there are also mental health and economic implications.

Among 28 published studies including almost 200,000 LGBTQ+ individuals, 12% underwent conversion therapy as minors and experienced higher rates of depression and substance use than peers who were not exposed.

Similarly, a 2022 survey by The Trevor Project reported that, out of the thousands of LGBTQ+ youth that were threatened with or subjected to conversion therapy, more than half attempted suicide in the past year, compared to 11% of youth with no intervention.

Additional negative effects were found in a study of members of the Mormon Church exposed to conversion therapy, including worsened self-esteem, anxiety, increased distance from God, and a sense of wasted time and money.

On the economic front, a new study estimated that conversion therapy costs nearly $100,000 per person over their lifetime. Alternatively, LGBTQ+ affirmative therapy would result in a $40,000 saving per person over their lifetime.

Given conversion therapy’s harms, many reputable health associations have formally denounced the practice. This even led Exodus International, the largest host of conversion programs worldwide, to disavow conversion therapy in a public apology prior to shutting down.

Despite the evidence, 51% of LGBTQ+ Americans live in states with no bans or only partial bans on conversion therapy. With the practice remaining fully legal in 21 states, President Biden’s executive order will not solve this public health issue alone.

A federal ban on conversion therapy through legislation would be the ideal solution but it would be difficult to achieve. Bills have been introduced in Congress four times since 2015, perpetually stalling in subcommittee. Bipartisan support is challenging due to religious influence and advocacy from parental freedom fighters.

However, recent polls indicate there is growing opposition to conversion therapy from conservative-led states, with 71% of Floridians and 80% of North Carolinians supporting bans against the practice. Internationally, over 370 religious leaders from 35 countries have called for a global ban.

To build momentum for state, and ultimately federal, legislation, it may be vital to strategize on the local level. When Ohio and Utah originally failed to pass statewide legislation, licensing regulations were developed to prevent health professionals from offering conversion therapy. To date, 80 local ordinances also ban the practice in select counties and cities nationwide, including several in Kansas, Kentucky, and Alaska, historically conservative-led states.

While the United Nations has equated conversion therapy with torture, only 14 countries have created a national ban on the practice. The United States is not among them, but evidence and ethics suggests it should be.

Resources:

The Trevor Project Hotline: 1-866-488-7386Conversion Therapy Survivors Support Group: ctsurvivors.orgThe post President Biden’s Executive Order isn’t enough to end Conversion Therapy first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 28, 2022

How We Process Meat, Memories, and Nutrition Research

A recent news story covered a study about processed foods and how eating those foods relates to cognitive decline. The only problem is, they didn’t report on an actual published study. They reported on a conference abstract and presentation.

The post How We Process Meat, Memories, and Nutrition Research first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 17, 2022

Alcohol: why won’t we just give it up?

Alcohol is the “golden child” of sinful indulgences. Cigarettes give you cancer; soda rots your teeth. But enjoy that martini! Despite how destructive alcohol can be, drinking – not abstaining – is the socially acceptable choice. Why do we see alcohol as worth the risk?

It’s not because of a lack of data. The data are clear: drinking can be really harmful. For example, in 2021, a record number of Minnesotans died from excessive drinking. Over 1,100, in fact, more than homicides and suicides combined. The state’s alcohol mortality rate has doubled since 2014. What’s more, these numbers don’t even include deaths indirectly tied to alcohol consumption, like drunk driving.

At a national level, from 2015 to 2019, over 33,600 Americans died from causes fully attributable to alcohol, like alcohol dependence. Over 140,500 died from alcohol-related causes, such as various cancers.

Despite these numbers, it used to be common to hear that a glass of red wine was good for your health. Media and science both said so, throwing around buzzwords like the Mediterranean diet, antioxidants, and heart health.

But research shows that’s just not true. At best, any potential health benefit from red wine is minor and you can get the same boost from a good diet. At worst, alcohol is really bad for you.

Alcohol use can lead to injuries and violence. It impairs your cognitive abilities, increasing the risk of car crashes, other accidents, and interpersonal conflicts. It also has significant consequences on your physical body, negatively impacting your heart and liver and increasing the risk of many cancers. More superficially, it’s heavy on calories and light on nutrition.

And yet, drinking is widely accepted, even glorified. Champagne is synonymous with celebration and beer with Sunday football. Unless you abstain for religious reasons or are in recovery, not drinking is the faux pas.

Why won’t we stop drinking, given all we know?

First, alcohol is cultural, and not just in America. People have readily consumed alcohol throughout all of history. It was actually medicinal in early times and sometimes considered safer to drink than water. Nowadays, Italians love their wine, other parts of Europe love their beer, and the Japanese celebrate sake.

Peer pressure – and a desire for social acceptance – is also a compelling force. One survey in the United Kingdom found that 85 percent of participants had been pressured to drink by their friends, with younger folks feeling it most intensely. Another study suggested that this pressure “isn’t [always] malicious and may not even be conscious.” It’s as if it’s simply embedded into our social framework.

But perhaps most importantly, for many, drinking is just fun. People associate alcohol with friends and laughter, and even good old-fashioned rowdiness. In a stressful world, we’re all looking to let off some steam. While using alcohol to cope isn’t healthy, it’s understandable that many appreciate the mood-boosting properties of a couple beers with friends.

All that said, we’d be healthier if we drank less. How to accomplish that though is the trick. Some argue for increasing taxes on alcohol, shown in the past to reduce consumption. Liquor licenses are on the ballot in a few states this November; addressing where we can buy alcohol and what kinds is another approach.

Shifting the social environment could be even more effective. The mocktail scene is taking off and might be here to stay. For health and even environmental reasons, more consumers are looking for nonalcoholic options, but ones that aren’t Grandma’s sparkling cider. With delicious – and fancy – zero-proof drinks available, we might all be won over without even realizing it.

I still enjoy a good gin and tonic and you might like your IPAs. But it might be time we face the music and really think about why we drink at all.

The post Alcohol: why won’t we just give it up? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 13, 2022

Who is innovation in the US health care system actually for?

Innovation is considered one of the American health care system’s strengths. In theory, innovation makes health care better and less expensive because it leads to new treatments and lower costs. But because innovation and new therapies exist in the context of disparities in coverage and access to care, these benefits are not felt equally across the population; innovation itself has the potential to exacerbate and deepen existing disparities.

Innovation, particularly in drug manufacturing, has become a significant priority for the private industry. In 2019, the pharmaceutical industry spent $83 billion on the research and development of new drugs. Between 2010 and 2019, 60 percent more new drugs were approved for sale than in the previous decade. And in the federal government, both sides of the political aisle rally around innovation. Members of Congress have introduced several pieces of bipartisan legislation to “accelerate promising strategies to improve the health care system and ensure patients have access to cutting edge innovation.”

However, innovation in the context of American exceptionalism means that its benefits only flow to those already privileged by the system; like all other parts of the health care system, innovation is only accessible to those who can afford it.

In the US, people are at the mercy of their insurers or public programs (if they have coverage). Consequently, the regulatory approval of a new innovative product doesn’t guarantee its access.

Research has shown that there is significant variation in commercial health plan’s coverage decisions for specialty drugs, which have been touted as some of the greatest achievements in health care innovation (in recent years, more than half of the novel drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration [FDA] have been specialty drugs). Not all plans cover these drugs equally — some plans don’t cover these medications at all, while others have more restrictive coverage.

Moreover, like all things in the US health care system, access to innovation is severely restricted for certain groups of people. Coverage for innovative therapies is even more limited for people in public insurance programs.

In the Medicare program, innovative treatment for people with end stage renal disease (ESRD) — a disease that disproportionately affects people of color — is a great example. In August 2021, the FDA approved a new drug called Korsuva to treat ESRD-related severe chronic itching. But Korsuva falls outside Medicare’s existing bundled payment for ESRD-related care.

There is a special mechanism to guarantee access to it for two years, but, after that, Medicare can choose not to cover it. It’s likely that Medicare will not choose to permanently add Korsuva to its ESRD bundled payment because there already are covered anti-itching medications (which are ineffective against ESRD-related severe chronic itching). With an annual cost of $17,000, it’s unlikely that individual dialysis centers will purchase and provide the therapy on their own, leaving patients with no good options.

People with Medicaid coverage also face more restricted access to innovative therapies that are ostensibly designed to help them specifically. Coverage (or lack thereof) for innovative treatment for people with hepatitis C virus (HCV) — which disproportionately affects Black people and people in prison — clearly underscores this problem.

People with Medicaid coverage face significantly higher rates of HCV. There are incredibly effective treatments available to treat people with HCV, but the costs of these treatments are prohibitively high (some manufacturers have priced standard treatment courses at $84,000). While some states have worked to ensure access to HCV treatment for people with Medicaid, access is severely restricted, because people have to meet onerous prior authorization requirements (in most states) and strict criteria in order to gain coverage. This has led to an increased risk of mortality among people with HCV who have Medicaid coverage, compared to those with private insurance.

And for people without insurance, access to innovation is oftentimes out of reach. Some drug manufacturers have programs that make some of their products accessible to those without insurance, but new medications are (at least initially) priced in ways that severely limit access.

When life-altering therapies are available, but largely out of reach for certain groups of people, it’s worth considering who innovation actually serves. For everyone to reap the benefits of innovation, it’s critical to consider who our health care system is designed to work for (and who it isn’t). Until then, innovation will improve the health and lives of some, while being largely out of reach to others.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Who is innovation in the US health care system actually for? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 12, 2022

Why Isn’t there a Birth Control Pill for Males?

Condoms and vasectomies remain pretty much the extent of birth control options for people who produce sperm, and both have problems. So why is almost all hormonal birth control aimed at those with ovaries? There have been some successes targeting the biological feedback process for hormones that regulate new sperm production, but progress is slow.

The post Why Isn’t there a Birth Control Pill for Males? first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Without supports for direct home care workers, older adults are at risk of unwanted nursing home admissions

The need for direct home care workers — health professionals who work with individuals in their homes — is growing, and demand outpaces supply. In the US, states can use American Rescue Plan funds to expand their direct care workforce, but this funding expires in 2025. Without a sustainable plan to recruit and retain direct care workers, aging Baby Boomers are at risk of unwanted nursing home admissions.

Direct care workers include personal care aides, home health aides, and certified nursing assistants (CNAs). All provide assistance with activities of daily living — tasks like feeding or bathing oneself. Home health aides and CNAs perform additional tasks, including monitoring vital signs, transferring individuals from a bed to a chair, and wound dressing. Depending on the state, they may assist with medication administration. All of these activities facilitate independent living in one’s home or community, the settings where the majority of older adults prefer to receive long-term care. Demand for the services of direct care workers continues to grow.

Despite their critical role in independent living, direct care workers generally receive low salaries and are undervalued by society. In 2021, the median pay for a home health aide or personal care aide was $14.15/hour ($29,430/year). It was only slightly higher for nursing assistants. Salaries meeting the federal minimum wage were not guaranteed until 2015. Low salaries, along with limited opportunities for career advancement and the potential for on-the-job injuries contribute to high rates of turnover. Forty to sixty percent of direct care workers leave their jobs annually. The work is important, but difficult and inadequately compensated.

In recognition of these issues, the 2021 American Rescue Plan provided states with Medicaid funding to “enhance, expand, or strengthen” their home and community-based care services, including those provided by direct care workers. Funding for direct care workers is intended to support recruitment and retention of staff and can be used to increase worker compensation. States have flexibility in how they use the funds — example strategies include investments in loan repayment, tuition assistance, hiring bonuses, career ladder development, and enhanced training. The ability to use these funds was recently extend to 2025, but there are no long-term plans to sustain improvements in infrastructure and wages.

To meet the growing demand for the services of direct care workers, long-term funding is needed to identify and sustain effective strategies targeting their recruitment and retention. Economic models suggest that increasing compensation of direct care workers to state-specific living wages would improve both recruitment and retention. Participants in loan repayment programs targeted to health care professions report high satisfaction with the programs, but data limitations make it difficult to draw conclusions about their effect on recruitment. A comprehensive approach that focuses on compensation, career advancement, improved working conditions and recognition of the value of direct care workers is likely needed. Where possible, states should monitor the recruitment and retention approaches used and evaluate whether they have had the intended effect on the direct care workforce. Best practices identified by one state can inform other states’ resource allocation decisions.

The population continues to age. By 2035, more than 1 in 10 United States residents will be age 75 or older. The need to secure resources and identify strategies to allow individuals to receive care at home when desired while supporting the workforce that makes this possible is greater than ever.

Research for this piece was supported by Arnold Ventures.

The post Without supports for direct home care workers, older adults are at risk of unwanted nursing home admissions first appeared on The Incidental Economist.October 10, 2022

How doctors can stop overlooking patients they’ve never seen

Today the Washington Post had a Q&A with a doctor about jerking while falling asleep (hypnic jerks). Because what is described resembles my condition (about which I posted yesterday), several people sent me the link. The quoted doctor may not understand how his words can cause harm, and how easy it would be for them not to.

The doctor addresses how hypnic jerks normally occur. In doing so, he misses how they, or things like them, can occur abnormally. Therefore, his advice comes off as insulting to those of us who struggle with sleep myoclonus and don’t have anxiety, aren’t stressed, and have already optimized sleep hygiene.

All he needed to add is, “If you have tried all this and still have problems, consult a specialist.” He could say more, if he knew more, but at least this would be enough to signal to patients like me that we’re heard. Without such words, we feel unwelcome by a health system that already has too little to offer us.

This is one big thing I’ve learned about having a rare disorder. Those with my condition, and undoubtedly others with rare disorders, are sometimes purposefully and sometimes accidentally dismissed. It’s frustrating and causes harm.

The post How doctors can stop overlooking patients they’ve never seen first appeared on The Incidental Economist.Aaron E. Carroll's Blog

- Aaron E. Carroll's profile

- 42 followers