K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 5

December 16, 2024

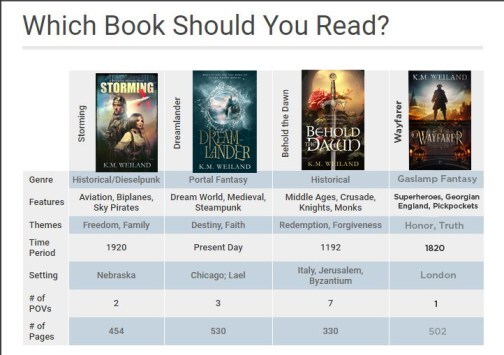

Top 10 Books I Read in 2024

I wasn’t sure how my reading was going to fare in 2024. This year was a such a different year for me. I spent the first half cramming a year’s worth of work into a few months, and the second half settling into a new house. But, not surprisingly, reading remained my anchor throughout all the hectic change. I reignited my love of fantasy, after having fallen away from it in recent years after some disappointing series, and I went down many a fascinating rabbit trail that originated from my interest in exploring the witch trials after visiting Salem, Massachusetts, last November.

I wasn’t sure how my reading was going to fare in 2024. This year was a such a different year for me. I spent the first half cramming a year’s worth of work into a few months, and the second half settling into a new house. But, not surprisingly, reading remained my anchor throughout all the hectic change. I reignited my love of fantasy, after having fallen away from it in recent years after some disappointing series, and I went down many a fascinating rabbit trail that originated from my interest in exploring the witch trials after visiting Salem, Massachusetts, last November.

Today, I’m sharing my top five fiction and top five non-fic for the entire year. I’ll hope you’ll chime in at the end with some of your faves!

Total books read: 70

Fiction to non-fiction ratio: 46:20

Number of books per rating: 5 stars (5), 4 stars (17), 3 stars (24), 2 stars (12), 1 star (2).

(Note: All links are Amazon affiliate links.)

My Top 5 Fiction Books of 2024 Fourth Wing by Rebecca YarrosI was not expecting to like this so much, but the characters sucked me in to the point where I couldn’t stop reading. It has its clunky moments, mostly in explaining the worldbuilding, but it’s a smart, well-realized fantasy that is noticeably grounded in the author’s understanding of the military. Can’t wait for the sequel!

When I skimmed through this to begin with, it didn’t grab me, and I almost didn’t read it. I’m so glad I did! Beautifully executed love story with excellent characters and an aching realism in the Afghanistan war scenes. The story is masterfully crafted, rising above genre tropes into an ode that seems to have come from deep within the author’s heart.

It wouldn’t be an end-of-year book list without a Pratchett novel. Pratchett does this thing where his comic fantasy books just sort of ramble along. They’re funny and enjoyable, but not amazing. And then the Third Act hits, AND THE WHOLE THING GETS EPIC. Granny Weatherwax bumbling through most of the book, fooling even the readers into thinking she’s just a dealer in folk remedies and superstitions, only to have her best the entire school of wizardry in an epic show of skill, was one of the best things I’ve seen so far in the series.

Truly, this is one of the most powerful narrative voices ever put on paper. The nuance and complexity of Holden’s pain, the dissonance between what he says, what he believes he believes, and what he really believes is beautifully captured. The love between him and his sister is deeply touching, and the overall effect tragically thought-provoking.

I wasn’t expecting this one to get me in the feelz so hard, but it surely did. The characters were beautiful, the unfolding relationship always felt spot-on without any unnecessary drama, the characters felt true and well-realized, and the FMC’s relationship with the baby boy had me in tears multiple times. Beautiful.

After visiting Salem, MA, last fall, I have felt a driving need to understand the history of the witch trials. This is, so far, the single best resource I’ve found. It is dense and extremely conscientious in its details, but the scholarship is top-notch. It speaks less to the actual historical events and more to the anthropological development of the circumstances and cultures that led to the European witch hunts. Fascinating, disturbing, and ultimately hopeful, it moves beyond pop culture or pat answers to shed light on a dark time, the details of which are too often painted with a thin brush.

This book presents a relatively simple approach to basic holistic good health practices, but I definitely picked up some new tips and inspiration. I have to admit I hadn’t even really considered that many of the most basic premises of healthy living are different for women than they are for men. Gave me lots of food for thought and has helped me hack some of my own health practices to better effect.

Exceptionally thought-provoking, even though the title might more appropriately (if less punchily) have been, simply, Food Production. The book creates a new baseline through which to understand ancient history and particularly the course of social development. It gets a bit repetitive in areas, but at the end of the day, I didn’t mind since the information is dense and there’s a lot to process.

Despite its title, this is the most detailed and useful feng shui guide I’ve read so far. It gets down to the practicalities while still presenting the larger system and philosophy. It’s what finally helped me “get” it.

The only thing I didn’t like about this book was… it was for Australians. If it had been country-specific to me, I would no doubt have found it as useful as Haddow’s countrymates probably do. As it is, much of the specific info wasn’t of much use to me. However, I did felt her approach offered me information and ideas that were invaluable for carrying over to my own financial structure, especially since surprisingly few books exist on this topic as yet.

And if all these goodies aren’t enough to fill your To Be Read pile next year, here are a few more!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What were your top books of 2024? How many books did you read? Tell me in the comments!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What were your top books of 2024? How many books did you read? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Top 10 Books I Read in 2024 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 9, 2024

Top 8 Lessons I’ve Learned as a Writer in 16 Years

Today, I want to take a moment to talk about eight of the lessons I’ve learned over my years of being a writer. Particularly, I want to share some of the the biggerepiphanies and moments that have impacted me in a way that’s changed my life. These are lessons that have been meaningful on a deep level and that I think are valuable to hear about and perhaps recognize as part of your writing journey as well.

Today, I want to take a moment to talk about eight of the lessons I’ve learned over my years of being a writer. Particularly, I want to share some of the the biggerepiphanies and moments that have impacted me in a way that’s changed my life. These are lessons that have been meaningful on a deep level and that I think are valuable to hear about and perhaps recognize as part of your writing journey as well.

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

This is something I learned relatively early on in my writing journey. Obviously, it completely changed my life since I’ve built a career around teaching story theory and story structure!

When I first encountered story structure, I’d written four or five novels without really knowing anything about writing. I hadn’t read any how-to books or encountered any ideas from other people. My stories up to that point were simply ones that came from my own heart and my own imagination and the osmosis from being a lifelong reader. But I didn’t have any concept that there were systems through which you could view writing and storytelling.

I remember when I first learned about structure, my first thought was, This is amazing! This is incredible! It absolutely just made sense. I could immediately see how plot structure was reflected in so many of the stories that I read and watched and loved.

My second thought was, Oh, darn, I’ve written all these books. I’ve published a couple at this point, and I didn’t know anything about structure. So they’re probably a mess.

And the most exciting thing was the moment when I went to my bookshelf and pulled out a couple of my books that were already published. I started flipping through the pages to get to the estimated timing points of say the First Plot Point or the Midpoint or the beginning of the Third Act. And it was amazing! The structure was there, even though I hadn’t consciously had any understanding of the terms or the timing or any of it. I was already intuitively and instinctively creating stories around this principle.

That just blew my mind. Honestly, that completely changed the trajectory of my life, not just because it allowed me to become passionate about teaching story structure and story theory, but also because it changed my view of how the world worked and how story was a reflection of life.

So my first lesson was, again, story structure is not just important, but amazing. I think that can be something writers miss because they’re so focused on the rules and “the way to do it” rather than asking, “Why? Why is this important?”

For me, digging into the why has been one of the greatest joys and pleasures of my life, not just as a writer, but just generally.

Lesson #2: Character Arcs Will Change Your LifeAfter discovering story structure and how that completely impacted my whole view of story, the next step was the character arcs. The lesson here for me was that character arcs will change your life.

Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic by K.M. Weiland (Amazon affiliate link)

As I started digging into character arcs, where that really solidified for me was when Writer’s Digest asked me to collaborate on a short series of what they called Annotated Classics. They would take classic novels and have someone go through from a writing perspective and comment on what the author was doing and sometimes the historical pertinence and things like that. They asked me to work on Jane Eyre. That book is still in print, if you’re interested.

In studying Jane Eyre for this project—just going through looking at the story structure and what Charlotte Bronte did with it, I began to see and understand how character arc worked on a deeper level. I could see how the character evolves from a Lie or a limited perspective that they believe into a more expanded perspective representing the story’s thematic Truth. I recognized how the beats of this character evolution interacted with story structure.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Writing that book completely changed my life. I never looked at character arc the same way. I would go on, of course, to write my book Creating Character Arcs. Once again, not only was that exciting from a writing perspective—being able to get under the hood and see how character arc worked at a story level—it also was one of those things that changed my life because again, we have this partnership and this reflection between life and story.

In being able to understand how character arc worked, it also completely changed how I looked at transformation within my own life. I began to be able to recognize the character arcs I was taking. I could see, Oh, this is the Lie I’m believing. And this is what I’m overcoming. And maybe I’m on a Disillusionment Arc over here and maybe I’m on a Flat Arc over here.

That has been a useful and empowering way to view my own life. We hear this thing about “being the hero of your own life.” As a writer, being able to take all of these tools and techniques we use in enhancing our stories and our characters and progressing to seeing our own lives through that lens is just an incredible gift.

And then, of course, we get to mine all that life experience and bring it back and put it into our stories with a deeper understanding of what our characters are going through. We have a lived experience of the steps of transformation .

Lesson #3: Define Your Own Idea of SuccessThe third lesson is more about the writing life than writing techniques. This lesson is “define your own idea of success.” Why are you doing this?

For me—and I think for many writers who want to or are able to make the transition into writing full-time—it’s important to understand what your goals are and to be in touch with your own values. Why?

Number one, there’s a lot of resistance in this lifestyle. It’s an uphill climb in many ways. There will be lots of nos. There will be lots of times where you’re querying agents or whatever, when you’ll be rejected and you won’t be able to gain entry into traditional publishing. On the flipside, if you’re self-publishing, it’s easy enough to put your book out there, but it’s much harder to actually sell copies.

The point is that the writing life can be very discouraging. It can feel like you’re not making any traction if you’re putting all of your emphasis on questions such as: How many books am I selling? How much money am I making?

Now, of course, all of that is important. I’m able to do this full-time, and I’m incredibly grateful for that. But it’s been a long road to get where I’m at. Particularly in the beginning, you don’t have a lot to show for what you’re doing. It might be other people are judging you for different choices that you’re making, such as choosing to self-publish. That was a big thing when I was first starting out. Self-publishing wasn’t as legit as it is now, and there was a lot of judgment about choosing to go that route. Self-publishing automatically made you less of a writer.

No matter how successful you are at any given point, there’s always somebody who’s more successful, somebody who’s making more money selling more books, having bigger book signings or winning more awards or whatever. You look at their writing and it’s amazing. You think, I would like to write like this.

Writing in itself is such a vulnerable act. More than that, it’s very hard to judge its worth. There is no hard and fast rule for saying what measures up and what doesn’t. There’s no level of books you can sell that says you’ve made it. There’s no guidelines that somebody can apply to your story and say, “This is a perfect story.”

There’s always something that has you asking, “Am I measuring up? Is it good enough?” And because there’s so much rejection involved and so much uncertainty about how you’re able to measure your success, something I had to learn early on in order to survive in the business was to define my success by my own terms. I had to learn to dig deep down deep inside of myself and ask, “Why am I doing what I’m doing? Is it to sell X amount of books? Is it to make X amount of money? Is it to win a particular award? Is it to be traditionally published?” I had to get really real with myself about the choices I was making and why. I had to learn to identify where I was making choices that weren’t actually in alignment with my own values and desires, but were instead based on some projected ideal “out there” that seemed to be what everybody else would respect as an established writer.

Being able to do that is a process. It’s something I refine all the time in my life. Certainly, as my career has progressed and gotten more stable to the point I have seen a certain measure of success, it has gotten easier to deal with some of the demons of doubt. But when things aren’t going the way I want them to, being able to come back to this lodestone question of “Why am I doing this? What is my guiding principle? What is underlying it?”—that has always been helpful to me in measuring the effort I’m putting in and asking, “Is it worth it? Is the stress worth it?” Sometimes it is. Sometimes it isn’t. It totally depends on my value system.

I also think you have to have the ability to advance those goals. They need to be realistic in the beginning. If your goal is to be a New York Times best-seller, then that’s probably not going to be something that’s going to happen in the first year. So you set smaller goals. It’s not so much about whether or not you’re reaching your goals as whether or not you are in alignment with why you’re doing what you’re doing. Are you writing for the love of it? Are you writing because you have something to say? Or are you writing because you believe stories are important? Are you writing because you believe it’s important for you to tell this story?

I used to say that I would write stories even if I knew no one would ever read them. And that’s still true. (In fact, sometimes it’s easier to write stories if no one’s going to read them!) That was something that was always a guiding principle for me. I would tell myself, “I’m not doing this to be read.” That’s not true for everyone, and that’s fine. But for me, being able to always come back to that and to remember that I’m doing this for my own reasons for—because I have something to say, because the stories want out—was always really helpful. When there was judgment or there was criticism or there was just some amazing writer I was comparing myself to, I could come back to that and just remember, “No, I’m doing me.”

Particularly, when you’re going to do this for the long haul, you have to have some kind of foundation like that to keep you on track with where you’re at and where you’re going.

Lesson #4: Writer’s Block Is Part of the Process

Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration (affiliate link)

If you have been following me for any length of time, then you know that starting around 2018, I went through a massive bout of writer’s block that lasted several years. It coincided with a difficult time in my life. There were just a lot of stressful things going on and my fiction writing fell apart for me for a while.

It was very disconcerting. This had been such a huge part of my identity up to that point, and then suddenly I couldn’t write. I was questioning my value system. “Do I want to keep doing this?”

What I’ve learned as I’ve worked through this process and have been able to overcome that block and return to writing fiction is that I think we stigmatize writer’s block. We make it sound like it’s something that should never happen. Certainly, it can become something that’s undesirable, but a lot of that is because we don’t recognize the ebb and flow of creativity.

Rest periods are important. They’re part of the process. But if you are writing full time, there’s this pressure to write constantly—to produce book after book after book after book. Now maybe that’s your natural rhythm and that’s great, but for most of us—for me—that’s not true. At the end, because I did push really hard for many years, the well emptied out and I didn’t have the creative juice to come up with another story.

Because of my lifestyle up until that point, my writer’s blog was extreme. But if we need to realize that being a writer doesn’t mean you always have to be writing. That’s something people ask me all the time, “Do I have to write every day to be a writer?” And my answer is, “Absolutely not.” You can write two weeks out of a year, and if you’re really into it and what you’re producing is really important to you, of course, you’re a writer. But if you are a professional writer, it’s a job, and you have to take some time off.

More than that, creativity is something that rises up from the subconscious. It’s not something we necessarily have conscious control over. Therefore, we have to give it space to come to us. We have to cultivate lifestyles that allow for it to really thrive and grow.

This has been a huge lesson for me because I naturally have a personality that tends toward workaholicism. It’s been a huge lesson for me to recognize that down periods of creativity are important; that they are part of the cycle; that creative cycles are necessarily like the cycle of the seasons. We have to come down into winter and be willing to take time and space without constantly trying to harness our creativity as if it’s an endless resource, rather than recognizing it as a gift and a partner and something that needs to be nourished and taken care of.

Lesson #5: Take Care of Your Creative HealthIf you have ever gone through an extensive period of creative burnout, then you know it’s brutal. It’s so difficult and scary and sad because, number one, creativity is a life force and to lose connection with that is very devastating on a purely primal level.

Second, to whatever degree “I am a writer” is a major identity for you, then losing connection with that and being in a place where you wonder if you’re ever going to get it back is scary. When you’re there, you don’t know who you are anymore. That in itself, for me anyway, was an extremely valuable process. I learned so much about myself and experienced so many ego deaths. Ultimately it was full of richness and blessing, but it’s still very scary and very difficult.

Finally, if you make your money doing this as this is your livelihood, then if you’d get disconnected from your creativity and your ability to be productive with that, that’s endangering your very survival at a certain level. And that is definitely scary.

We hear so much these days about taking care of your mental health, and I think more and more we’re also hearing about taking care of your emotional health as part and parcel of that. But another nuance is starting to think more consciously about taking care of our creative health. However you may be expressing your creativity—storytelling, in this context—you have to take care of that. You have to cultivate a lifestyle and an awareness that allows that to thrive.

That looks a little different for everybody. Honestly, just having good habits in general is a good place to start. Taking care of your physical health and your mental health and your emotional health clears your energy. It clears the space in your life to allow that creativity to emerge.

You can think of creativity as giving birth. It’s a very vulnerable act, and you don’t do it out in the open where there’s danger and all kinds of stuff happening. In the olden days, you’d go to a cave, someplace private, probably with people guarding the entrance. Creating a story or a piece of art is kind of like that. The story doesn’t want to come out if it doesn’t feel safe.

So if there’s all this stuff going on in our brains—stress and distraction and all of that—it’s hard to birth something. It’s hard to get into that space where you can birth the story idea and put in the work to, not just type out the words, but to channel it up from your own deep creativity.

For me, particularly in these years since my writer’s block, it’s been a huge lesson and a huge process of learning how to cultivate a creative life. It’s an ongoing thing. I still enjoy being productive and love doing the work aspects of my job and showing up for that, but I also have learned to put so much more emphasis and care into taking care of myself in service to the creativity.

Something I’ve learned about burnout is not so much that it happens because “the well is empty,” as because “the well is clogged with junk.” Basically, it’s too full. It’s not that the well is empty; it’s that it’s too full with junk. Returning to creative health is a process of clearing stuff out.

Sometimes what’s clogging the well is emotions, but sometimes it’s just life. Sometimes there’s just too much going on, and you need to be able to say, “No.” You have to be able to set those boundaries with yourself so that you have space, you have downtime, you have the ability to just be with yourself and your creativity. Just stare out the window and dare to daydream—things like that.

I think we miss that sometimes in hustle culture, and certainly the writing industry in general has a lot of hustle culture. And yet the essence and the foundation of what we do as creatives requires stillness. It requires space, and we have to be willing to take care of our creative health if it’s going to supply and fuel all the things we want to do and put out into the world.

Lesson #6: Your Fellow Writers Are Not the CompetitionNow, this was never a huge problem for me, but I’ve definitely refined my perspective over the years. Again, I think much of the potential problem here is that what it means to be successful as a writer is often so undefined. Writers often aren’t sure what we’re trying to get out of the experience—and so we sometimes borrow definitions from the world or from other people. It’s easy to only look up to people who are making millions of dollars and selling massive amounts of books and getting huge movie deals and and things like that. Even on a smaller level, when people in our genre or maybe our writers group gets a book deal before we do something like that, it can be easy to feel less than, and, automatically by that token, to then feel a certain resentment or envy toward our fellow writers. We may feel, Well, because they got what I wanted or they got something better than I did, then their success is somehow endangering my opportunity to do the same.

Particularly within the writing field, however, this is categorically untrue. For one thing, every time somebody reads another book they love—every time a reader has a great reading experience—all that’s doing is opening the door for another book to come into their lives. They’re thinking, That was great! I want to do that again! And they’re looking out there for something else—and that could be your book. So whenever a fellow writer is successful, it’s a win for everybody. The demand for stories is insatiable. It’s only a matter of if you can put out good ones that people like and get them into readers’ hands.

Being able to look at it that way can help with sometimes this tendency we have to resent fellow writers’ success or let it make us feel less than, because if we flip that on its head and start looking at our fellow writers—particularly those we admire or want to be like—as inspiration, they become “way showers” for what is possible for us.

More than that, you can study what they do. They’re presenting a model of how to do it, and you can study that to figure out what fits you and what is actually in alignment with why you’re doing this and what you’re doing.

Reframe any of this insecurity that arises in response to a fellow writer’s success into an opportunity to get where we want to go to. View them as someone who’s ahead of us on the path and therefore breaking trail. They’re breaking trail and showing the way for us.

Lesson #7: Writing Is the Most Challenging Mirror of AllWhen we dig deep into the lifestyle and really commit to it, we can use it in this meta way to grow our own lives.

Writing is difficult by nature. It requires discipline and consistency. It shines a light on the parts of ourselves that are insecure or where our ego is in control. It is also, by nature, an extremely vulnerable act.

Writers have to be very brave to go into the authenticity of showing parts of ourselves, whether it’s our characters or whatever else that we’re putting into these stories. To share them with other people, who could say or think anything about it, we are putting ourselves out there in such a real and raw and honest way. That requires profound courage.

Now sometimes, we don’t look before we leap. We don’t realize what we’re doing. We put the book out there, and Whoa. I feel that way every time I put out a new project or book. I’m happily writing it and then I put it out there and feel, Oh my gosh, what have I done?

But for me, the writing life has been such an incredible experience for deepening my understanding and my relationship to myself. So basically the lesson here is don’t become a writer and go deep in this lifestyle unless you’re able and willing and want to have the full experience of human life and what it means to be here in the range of emotions and the ups and the downs and to face those deep challenges

Being a writer will offer those challenges. Now, these challenges are not insurmountable. I don’t intend this caveat to imply, “Oh, writing is too hard.” No, it’s glorious. It’s just that it’s not easy.

Something I’ve learned and will probably always be learning in different nuances as I go through as I continue to write is that there’s always more to learn about the writing life and that it’s such a mirror for myself and my own experience. As long as I’m brave enough to look in the mirror, there’s so much there for me to be able to learn and expand and to grow. The never-ending story of our own lives is basically what is being reflected back to us.

Lesson #8: “Being Published Isn’t All It’s Cracked Up to Be. But Writing Is.”

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott (affiliate link)

Finally, lesson number eight is a quote from Anne Lamott in her book Bird by Bird, which I just have always really appreciated and loved.

Being published isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. But writing is.

I come back to that again and again. I mean, being published is great. I fully love it, but at the end of the day, making the most of the writing life comes back to knowing why you’re doing what you’re doing.

For me, publication is not why I’m doing it. I’m doing it for the journey. It’s the idea that it’s not about the destination; it’s about the journey. When I can stay in that place and remember that and be present with the journey, then it just elevates the entire experience. It allows what I’m able to bring to my stories or to my teaching to be so much richer and deeper and more valuable.

***

You can see a theme in all of my eight lessons. I suppose basically we could sum it up like this: For me, writing has been so much more than just about telling stories or writing books. It has been this incredible journey through the depths, the heights, the lows of life itself. Being able to look at it that way and see it in that light is so powerful and so exciting.

I hope some of this is food for thought, that it’s interesting or helpful to you on your writing journey. I’d love to hear some of the most important lessons you have learned in your writing life!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are some of the top lessons you’ve learned as a writer? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Top 8 Lessons I’ve Learned as a Writer in 16 Years appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 2, 2024

The 5 Gift Rule for Writers at Christmas

Christmas gifts are one of my favorite traditions—and so is this yearly round-up of gifts for writers at Christmas. Sometimes, however, it can be difficult to balance the joy of giving with the desire to give mindfully and sustainably. Although I used to love browsing the Internet for fun and silly writer-themed gifts that I could share with you all in these posts, at a certain point, I eventually felt that approach was out of integrity with how I try to live my own life and choose my own Christmas gifts for my loved ones.

Christmas gifts are one of my favorite traditions—and so is this yearly round-up of gifts for writers at Christmas. Sometimes, however, it can be difficult to balance the joy of giving with the desire to give mindfully and sustainably. Although I used to love browsing the Internet for fun and silly writer-themed gifts that I could share with you all in these posts, at a certain point, I eventually felt that approach was out of integrity with how I try to live my own life and choose my own Christmas gifts for my loved ones.

Over the last few years, I’ve shared some sustainable-themed Christmas gifts for writers posts, including the following:

17 Eco-Friendly Gifts for Writers This Christmas10 Best Books to Buy a Writer For ChristmasThe Best Christmas Gifts This Writer Has Ever ReceivedDigital Christmas Gifts for WritersThis year, while searching for gifts for my nieces and nephews, I ran on to the clever “5 Gift Rule.” Since I (quite obviously) adore rule-based systems that simplify planning processes, this got me quite excited. I decided to adapt it for this year’s Christmas gifts for writers post.

The 5 Gift Rule for Writers at ChristmasThe 5 Gift Rule suggests a limit of five varied gifts per person, based on the following little ditty:

1. Something they want.

2. Something they need.

3. Something to wear.

4. Something to read.

5. Something to do.

Today I’m conjuring my imaginary writer friend (who looks like a Picasso conglomeration of me and all of you) and choosing the five(-ish) gifts I’d love to give all of you this Christmas! Perhaps you will find just the right gift for your best writing bud or a little something to add to your Santa list (since I know you’ve been nice this year, yeah?).

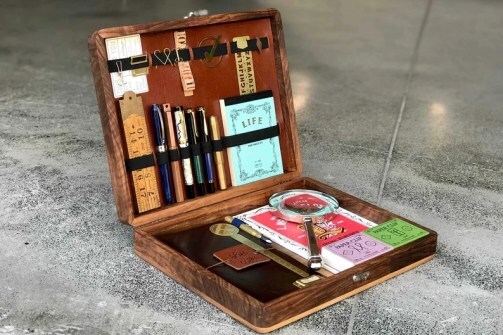

Gift #1: Something Writers WantEveryone wants something a little different. And sometimes one writer’s want is another’s need—and vice versa. But since the essence of this gift idea is a splurge, I’m picking something that’s just so beautiful it makes you want to purr. After all, most writers are all about the aesthetic. For sheer luxury and pampering, my gift suggestion is a writing box or tote from Galen Leather Co. They gifted me a Writer’s Medicine Bag a few years ago for an unboxing video, and I still feel incredibly writerly whenever I pull it out. In searching their store today, this incredibly beautiful Portable Writing Box jumped out at me.

Portable Writing Box from Galen Leather Co.

Gift #2: Something Writers NeedIn truth, a writer’s needs are pretty small. A notebook, a pen, and some time to ourselves is all we really need. But if you’re on the path to independent publication, you’ll need a top-notch cover too. Depending on my needs, I use and recommend two different book-cover companies.

Damonza has created most of my covers, including all my non-fiction covers.

In the last few years, I commissioned Ebook Launch to redesign a couple of my novel covers, and I have been thrilled with the results.

And if you know a writer who isn’t quite ready to publish their book, I can guarantee nothing would make a more delightful and thoughtful gift than a custom-commissioned cover.

Gift #3: Something Writers Can WearA good cotton T-shirt goes with anything, offers a good conversation starter (maybe even an opportunity to tell others about your book), and might even turn into your lucky writing shirt. Here were a few of my faves:

“That’s What I Do. I Write and I Know Things” T-shirt (affiliate link)

“In My Author Era” T-shirt (affiliate link)

“Do the Write Thing” T-shirt (affiliate link)

“I Am a Writer. I Dream While Awake” T-shirt (affiliate link)

Gift #4: Something Writers Can ReadHonestly, this gift could just be the whole list, ya know? There are just so many great books for writers—not just writing how-to or marketing how-to, but all the stories too. A few years ago, I shared my definitive list of books to buy writers for Christmas. This year, I’m sharing my most recent favorite, which I absolutely devoured and enjoyed from beginning to end, not just for its story wisdom for its life wisdom.

The Anatomy of Genres by John Truby (affiliate link)

As I wrote that last line, it made me think of another long-term favorite that I didn’t include in that (apparently not-so) definitive list. This oldie-but-goodie gets equal props for speaking to a larger purpose than simply that of writing an amazing story (which it does as well). (It inspired this post from a few years back: A Challenge to Write Life-Changing Fiction).

The Emotional Craft of Fiction by Donald Maass (affiliate link)

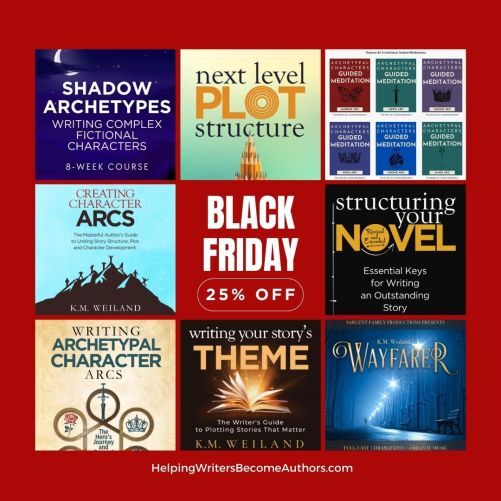

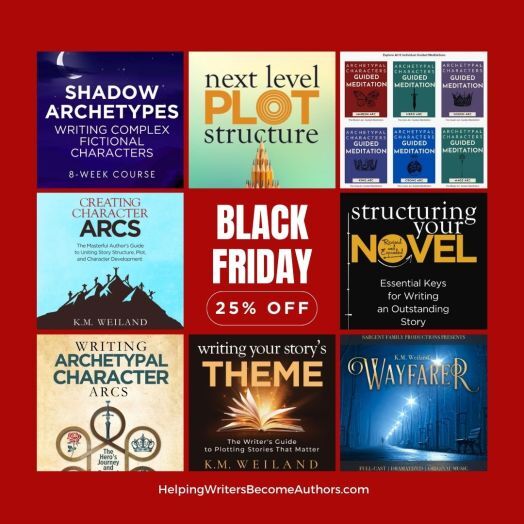

And then, of course, there’s always a few books which readers of this blog might already be familiar with—all of which are on sale for one more day (December 2nd) during my sitewide 25% off Black Friday sale.

Gift #5: Something Writers Can Do

Gift #5: Something Writers Can DoNaturally, the most important thing writers do is write. So why not give the gift of a fun contest entry? Amanda Scotland, co-host of the Not Quite Write Podcast suggested their flash-fiction contest for my Christmas gifts for writers post, and I thought it fit perfectly this year. The Not Quite Write Prize for Flash Fiction looks like a creative and inspiring opportunity to challenge your storytelling skills—and break a few writing rules. With its unique format, this competition invites writers to craft up to 500 words in just 60 hours, using two prompts and one “anti-prompt” for an exciting twist. You can also gain (or gift) access to an exclusive lounge with members-only content and a vibrant community. Winners enjoy cash prizes, podcast features, and even anthology publications. Gift cards are available to cover entry fees and critique upgrades.

Not Quite Right Flash Fiction Contest Gift Card

May you have as much fun giving as receiving this Christmas, and may Santa fill your stocking with just what you want and need (and wear and read and do). Merry Christmas!

P.S. Today is the last day of my Black Friday sale: 25% off every product in my store, including my books, workbooks, courses, software, and writing meditations.

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The 5 Gift Rule for Writers at Christmas appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 25, 2024

Happy Thanksgiving, Wordplayers!

Here in the U.S., Thanksgiving is celebrated this Thursday. One of my most meaningful rituals for this holiday is writing you this email.

Every year, I sit down to feel the depth of my gratitude for what has passed in the last twelve months.

This year, the depths are deep. After years of wrestling with my living situation, I bought a house that’s pretty darn close to being my dream home. It has been a incredible experience, a roller coaster of some of the highest highs and lowest lows I’ve ever experienced. The stress has been insane. I’ve had to surrender so much of my desire for control. But on the other side of facing some of my deepest fears, I am overwhelmed with gratitude for everything I’ve achieved, been given, and am getting to live into.

One thing I am always grateful for is… you.

If this year has taught me anything, it’s that the stories we tell ourselves—both good and bad—are only faint reflections of life’s deeper Truths. Meaning shapes and reshapes itself. Fears and hopes dance an endless tango. The great irony is that even though all we can truly lay claim to is this one moment and its one breath—there is a depth there, if only we can learn to see it, that is everything.

As my life radically reshapes itself with this move, I come back again and again with gratitude for all of you who let me do what I do—who show up to read the blog posts and to support my work by purchasing books or joining my Patreon. But it’s more than that.

Our stories may be ever-changing, but they are what grant meaning to it all. One of the stories I get to live is that the spinning of good tales matters—and I am blessed to get to examine that deeply, to teach, to share, and to walk with all of you in your own stories—both those on paper and those out here in the wind and fire of real life.

This has been an intense year for pretty much all of us, for many reasons. As those of us in the Northern Hemisphere wander into the darkness of the winter months, may we seek the truths in the shadow on our way back to the light. If the archetypal shape of story teaches us nothing else, it teaches us that this is the way.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! Thank you for being here with me. Thank you for listening and learning. Thank you for telling your stories!

You know what I always say…. “There’s no such thing as just a story.”

P.S. Only a handful of days left on my Black Friday sale: 25% off every product in my store, including my books, workbooks, courses, software, and writing meditations.

The post Happy Thanksgiving, Wordplayers! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 18, 2024

25% Off All Books, Courses, Software, and Meditations for Black Friday

This holiday season, I’m offering 25% off every product I’ve ever created! This means that for a limited time (November 18th–December 2nd), you can grab every book, course, and tool I sell here on my site at this special holiday price. The discount has already been applied sitewide, so no need to worry about coupons.

The sale starts out with my writing books on plot, character, and story structure, including my brand new book Next Level Plot Structure. Then you can take it a step further with interactive workbooks (including the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software) that can turn your knowledge into practical skills. Dive deep into character development with the Creating Character Arcs Course and this year’s brand new eight-week email course Shadow Archetypes: Writing Complex Fictional Characters. And don’t miss the Archetypal Character Guided Meditations for delving into your characters’ minds and dreaming up new story ideas.

Plus, you can grab all my novels and even the full-cast audio dramatization of my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer (which is not available on my site but via the producer here and requires the code BLACKFRIDAY2024).

Please note that I only sell digital products (e-books, etc.) on my site. However, if you’re interested in paperback versions of my books, those are available on Amazon. Audio versions of many of the books can also be found on Amazon and Audible.

Whether you’re a budding writer or a seasoned wordsmith or just in search of a good read, it is my hope and intention that these tools will enhance your storytelling prowess. Or maybe they’ll just help you figure out what to get your writing buddies for Christmas.

You can find more details about the products below, and if you’re still not finding what you’re needing right now in your writing journey, keep scrolling for seasonal offerings from other writing brands.

25% Off My Full Arsenal of Writing ResourcesUnlock the secrets of exceptional storytelling with this extensive suite of writing tools and resources, which I’ve spent the last 16 years designing to help you refine your craft and bring your creative vision to life.

Writing Books: Dive into my acclaimed guides, including Outlining Your Novel, Structuring Your Novel (now in a revised and expanded second edition), Creating Character Arcs, Writing Your Story’s Theme, Writing Archetypal Character Arcs, and my brand-new book Next Level Plot Structure for insights into plot development, character creation, and story structure.

Workbooks: Take what you learn to the next level with the interactive workbooks Outlining Your Novel Workbook, Structuring Your Novel Workbook, and Creating Character Arcs Workbook. These practical companions empower you to apply your insights directly to your work, ensuring you can turn your knowledge into tangible skills.

Shadow Archetypes Course: Unlock the power of character transformation with my new Shadow Archetypes Course, an eight-week journey into the depths of archetypal character arcs. Ideal for writers at any stage, this course reveals how mastering the psychological balance between passive and aggressive shadows can elevate your characters’ emotional depth and bring them to life in powerful, relatable ways.

Character Arcs Course: Character development is paramount, and the six-hour Creating Character Arcs Course can help you create dynamic, relatable characters. You’ll learn to craft authentic character arcs that will resonate with readers and make your stories unforgettable.

Archetypal Character Guided Meditations: Take a unique journey into your characters’ minds with my unique Archetypal Character Guided Meditations (sold separately or as a discounted bundle) based on my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. Bring unparalleled depth to your writing by gaining deep insights into your characters’ motivations, desires, and fears.

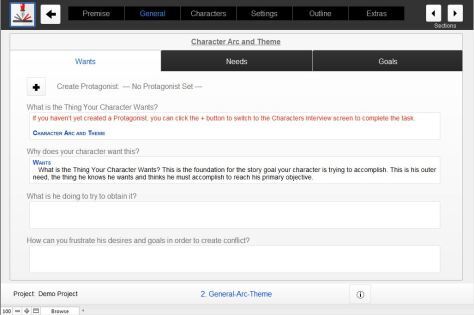

Outlining Software: Use the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software to streamline your writing process, organize your thoughts, plan your plot, and track character development.

Novels: Embark on journeys through time and imagination with my historical and fantasy novels Behold the Dawn, Dreamlander, Storming, and Wayfarer. (The full-cast audio dramatization of Wayfarer is also 25% off here with the code BLACKFRIDAY2024.) Adventure awaits!

Transform your storytelling abilities, captivate your readers, and make your mark in the world of writing! Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

More Black Friday Deals!I’m participating in a joint promotion for deals on writing programs, courses, and moret. Following, you can find dozens more seasonal deals for writers. Please make note of the dates, as not all of these sales are live at the same time.

Note: These are not personal recommendations, and I do not have personal experience with all of these products and companies. If you have questions about any of the below offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

ProWritingAid: 50% offDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 3

ProWritingAid is the essential toolkit for storytellers, helping you to craft your story and bring it to life. Real-time feedback and in-depth analysis will show you how to strengthen your story, give your characters depth, add impetus to your plot and so much more. ProWritingAid provides the tools, resources and inspiration you need to unlock your potential. It’s like having an English teacher, editor, critique partner and writing buddy all in your favourite writing app.

Fictionary: 40% offDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

Fictionary’s StoryTeller Software and Live Courses offer a comprehensive process to improve story structure, pacing, character development, and settings.

Women in Publishing Summit: $25 off the early bird pricing with code WIPBF25Dates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

The largest virtual summit designed to support women in the publishing industry. Authors, editors, publishers, book marketers, etc., come together to build community, network, learn together, and support each other.

One Stop for Writers: 35% off with code BLACKFRIDAY24Dates: Nov. 14–Dec. 1

Whether you’re designing rich, complex characters with the Character Builder, structuring your plot with Story Maps or penning masterful description using the iconic show-don’t-tell thesaurus database, One Stop for Writers’ arsenal of tools ensures you will write with confidence. Use BLACKFRIDAY24 at checkout to get 35% off 6-month plan. Writing can be easier!

Shut Up and Write the Book by Jenna Moreci: $.99 E-BookDates: Nov. 27–Dec. 2

Writing a book can be daunting, but it doesn’t have to be. Are you struggling to finish, or even start your novel? Are you overwhelmed by the many steps in the writing process, drowning in endless drafts, or creatively blocked? Shut Up and Write the Book is a step-by-step guide to crafting a novel from your first spark of an idea to the final edit. Whether you’re brand new to writing or wanting to hone your skills, this action plan provides straightforward advice while demystifying the art of storytelling. Enjoy bestselling author Jenna Moreci’s no-nonsense guidance and saucy sarcasm as she walks you through every step of the writing process. If you want to finally hunker down and finish your novel, read Shut Up and Write the Book today.

Book Funnel: $50 OffDates: Nov. 25–Dec. 2

The fundamental tool for your author business, BookFunnel delivers reader magnets, delivers direct sales e-books and audiobooks, and helps authors reach new customers through group promos and author swaps. Take advantage of their best in the industry support and take $50 off an annual subscription to the Mid-List Author and Bestseller Author plans.

Atticus: Free Course With PurchaseDates: Nov. 28–Dec. 2

Transform your writing journey with Atticus.io—the all-in-one powerhouse for book writing and formatting. Forget juggling multiple tools; Atticus brings you a sleek, intuitive platform that takes you from draft to publish-ready masterpiece effortlessly. Atticus.io is your non-negotiable companion if you’re ready to publish like a pro.

Novlr: 30% off with code BLACKFRIDAY24Dates: Nov. 1–Dec. 31

Novlr is the first writer-owned creative writing workspace that lets you focus on what’s most important; your words. Our smart design is distraction-free, writing streaks and goals keep you motivated, advanced analytics provide insights into your best writing times, and automatic cloud syncing keeps your work safe. You will be more productive with Novlr.

Novel Factory: 30% off with code BLACKFRIDAY2024Dates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

The Novel Factory app is designed to help writers turn their ideas into fully developed, captivating novels. With powerful planning tools, in-app guidance, and a simple, intuitive design, it’s everything you need to bring your story to life—from first draft to final edit.

Inkspired: 25% OffDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

Inkspired is a dynamic storytelling and publishing platform designed specifically for emerging authors. Whether you’re crafting serialized fiction, novels, book series, webcomics, or experimenting with other creative formats, Inkspired provides you with the perfect space to write, publish, and share your work with a global audience. Our platform is dedicated to helping you grow as an author by connecting you with passionate readers from around the world, expanding your reach, and offering the tools to monetize your content.

Publisher Rocket: $30 Off (and free course)Dates: Nov. 28–Dec. 2

Your book deserves to be read! Join other authors using Publisher Rocket to sell more books through optimizing keywords, categories, and your ad campaigns.

Write|Publish|Sell: 40% OffDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

Instagram for Authors is a power packed course providing authors with all the tools they need to successfully use Instagram to Market and grow their author platforms… which helps to sell their books. Since implementing these strategies, our authors have been selling FOUR TIMES as many books at launch. It has thrilled us to see the results that our efforts have taken. Led by our IG strategist, this course is power-packed with all the tools you need to start and grow your Instagram account, and how to sell a ton of books at launch.

Dabble: 30%–40% OffDates: Nov. 29–Dec. 2

Dabble offers a streamlined writing experience, perfect for authors who value simplicity and efficiency. With its clean interface, this cloud-based platform ensures your work is always accessible, both online and offline. Key features like story notes and goal tracking help organize your ideas and track progress, while the platform’s automatic backup provides peace of mind. Ideal for writers at any stage, Dabble is the essential writing tool for crafting and refining your stories.

MasterWriter: 40% OffDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 3

MasterWriter is the most powerful suite of writing tools ever assembled in one program. Why struggle to find the right word when you can have all the possibilities in an instant?

Book Brush: Two Months FreeDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

Your schedule is jam packed with writing, marketing, and everything else on your plate. Book Brush services can help lighten your load with your choice of two all-inclusive social media plans: Meta Plan: We’ll manage your Instagram and Facebook, creating eye-catching graphics and reels to build a strong, branded presence in the author niche and keep your fans engaged. Video Plan: We’ll produce 15 custom reels each month for your TikTok and YouTube channels, tailored to capture your unique style and audience.

Writing Mastery Academy: 20%–50% off with codesDates: Nov. 18–Dec. 2

Transform your writing journey with the Writing Mastery Academy, your complete writer support system, created by bestselling author Jessica Brody (Save the Cat! Writes a Novel). Get comprehensive guidance from idea to published novel through 13+ on-demand courses, live office hours, webinars, and a supportive writing community. Black Friday Special: Save 20% on annual membership with code BLACKFRIDAY20 or get 50% off your first 3 months of monthly membership with BLACKFRIDAY50.

Miblart: 20% off with code MIBL20BLACKDates: Nov. 25–Dec. 1

Don’t miss a chance to get a professional book cover for an affordable price! Miblart is a book cover design company that creates book covers for different genres. Our services includes stock-photo manipulated cover design, illustrated cover design, logo design and branding, author swag design, formatting and layout. Everything in one place to make your book look amazing and atttact your target audience

Getcovers: 25% off with code BLACKDEALSDates: Nov. 25–Dec. 1

On a tight budget for book launch? Try Getcovers! Getcovers is a book cover design company that provides book cover design packages for a shockingly low price – just $10-$35, depending on the package you choose. Don’t miss a chance to save big this Black Friday and get a book cover with a 25% OFF discount!

Note: If you have any questions about any of the offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

The post 25% Off All Books, Courses, Software, and Meditations for Black Friday appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 11, 2024

Antagonist vs. Villain: What’s the Difference?

Is the antagonist always the bad guy? So often, we use the terms interchangeably. But this practice can lead to confusion about the true function of the antagonistic force within a story. Contrary to common parlance, the antagonist vs. villain dynamic isn’t a straightforward equation. Although the roles often overlap, a character can be an antagonist without being a villain—or be a villain without being an antagonist.

Is the antagonist always the bad guy? So often, we use the terms interchangeably. But this practice can lead to confusion about the true function of the antagonistic force within a story. Contrary to common parlance, the antagonist vs. villain dynamic isn’t a straightforward equation. Although the roles often overlap, a character can be an antagonist without being a villain—or be a villain without being an antagonist.

The same is true for protagonist vs. hero. Although many writers use the terms interchangeably, the truth is obvious: not all protagonists are heroic, just as not all antagonists are villainous. In fact, as I often point out, it is entirely possible for your protagonist to be the most morally objectionable person in your story, while your antagonist is the most morally upright. We see this in stories such as Catch Me if You Can, in which the protagonist is a con man and the antagonist is the FBI agent trying to stop him.

Catch Me if You Can (2002), DreamWorks Pictures.

This is an important distinction. For one thing, it allows writers to step out of the boxes they may sometimes feel they have to cram characters into. Allowing stories to explore morally gray areas not only deepens thematic opportunities but also brings in greater realism and a more accurate exploration of life.

More than that, making this distinction helps writers understand the true role of the functional antagonist (and protagonist) within a story. What is a “functional antagonist”? Here, we’re talking about not simply the character of antagonist, but stripping it back to understand its function within the equation that is story. Basic story theory doesn’t care about the specifics of your antagonist’s personality or motivations. Story theory only cares about the bottom line. Is this character fulfilling the role of antagonist in a way that creates story?

Definitions: Antagonist vs. VillainWhat’s the difference between the oh-so-technical antagonist and the oh-so-colorful villain?

First, let’s examine what plot, at its most basic, actually is: a protagonist whose forward momentum is met by opposition. Usually, this forward momentum is the result of the protagonist’s goal (or at least intention), and the opposition is what creates the conflict. (I’ve written elsewhere about the true definition and function of conflict in story.)

The antagonist is the opposition.

In technical discussions, I often prefer the term “antagonistic force,” since this emphasizes that this opposition does not necessarily have to be characterized as a person. It might be the weather, the “system”, mental illness, or any number of other options. Any number of stories can be pointed out as lacking human antagonists, but this does not mean they don’t still feature antagonistic forces.

The antagonistic force is something that creates obstacles to the protagonist’s forward momentum. These obstacles can be as simple as a flat tire, freezing rain, or a bounced check. Most of the time, such obstacles will be unified by a common cause, even if this is something as thematically vague as “bad luck.” The most direct approach is to personify the cause of the obstacles as a specific character. This character is the antagonist.

Often, when we think of the type of character who might cause obstacles for another character, we think of someone with malicious intentions. After all, if a person is the cause of that flat tire, the motives at play aren’t likely to be morally positive. Therefore, it only makes that such a character must be… a villain.

Particularly, when we create stories in which the protagonist is blatantly heroic or at least morally positive, we often want to create an opposing character who can provide the contrast of immorality. Not only does this contrast make the protagonist more sympathetic and admirable, it also creates the opportunity to explore both sides of whatever moral issue is at stake. Both characters can exist on a moral spectrum, ranging from angelic hero and demonic villain to characters who share more in common than not, such as with Leonardo DiCaprio’s and Matt Damon’s cop and mobster characters in The Departed.

The Departed (2006), Warner Bros.

However, because “villain” has no specific correlation to the antagonistic force, it’s equally possible to see a villainous character who is not the antagonist—functioning either as the protagonist (e.g., Alex DeLarge in Clockwork Orange) or as a supporting character who is not opposing the protagonist’s forward momentum (e.g., Mr. Wickham in Pride & Prejudice).

Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.

What Is the Purpose of an Antagonist in a Story?The antagonistic force exists to oppose the protagonist’s forward momentum toward a goal and to create conflict. From this recipe, we get plot. When these elements are all thematically harmonized, we get a tight, well-focused plot.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Without the antagonistic force to create opposition, the protagonist would be able to immediately gain the plot goal—and the story would be over. The opportunity for the protagonist to transform as a result of overcoming this opposition would also be over, which means not only do we lose plot, we lose character arc as well.

In most stories, the antagonist’s motivation will pre-date the protagonist’s, creating the framework that forces the protagonist to learn more effective tactics for overcoming the existing obstacles. We see this obviously in stories in which the protagonist must take on a much larger system, such as Katniss Everdeen overthrowing the Hunger Games or John Dutton defending his ranch against developers.

Yellowstone (2018-), Paramount Network.

We also see it in stories in which the antagonistic force makes its first move before the protagonist is even aware of the antagonist as an opposing element, such as we see with Lt. Daniel Kaffee prosecuting a case for a crime that was committed prior to his knowledge of it, or Harry Potter joining a magical war that began before he was born.

A Few Good Men (1992), Columbia Pictures.

It also exists in conflicts that may seem, at first glance, to be initiated by the protagonist’s actions. For example, The Fugitive features a perfect example of an antagonist who is not a villain. Deputy Sam Gerard blatantly represents justice, law and order, and an adherence to duty. He has no knowledge of or interest in the protagonist—wrongly accused convict Dr. Richard Kimball—until Kimball escapes and comes under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Marshalls. At first glance, this might seem like Kimball initiated the conflict between himself and Gerard. However, when we zoom back, we can see that Gerard’s opposition always existed, via the U.S. Justice System, and was already engaged against Kimball, even before Gerard showed up as the personified antagonist.

The Fugitive (1993), Warner Bros.

The Fugitive pits Kimball and Gerard against each other in a tightly woven conflict, in which Gerard does everything in his power to create obstacles to Kimball’s goal of learning who murdered his wife so he can clear his name. In essence, Gerard and Kimball are morally aligned throughout this story, both working in the name of justice and using only tactics that are in accordance with that principle. All that differentiates Gerard as the antagonist is that he is the one creating opposition to the protagonist’s forward momentum toward a goal.

From this, we also see how necessary the role of a good antagonist is to a story. Without Gerard’s presence, this story would have lacked its intense throughline—something the story’s villain could not have provided since he was offscreen for 90% of the movie.

The Fugitive (1993), Warner Bros.

What Is the Purpose of a Villain in a Story?The villain is a morally reprehensible person, motivated to act maliciously and with cruelty. The degree of villainy can vary wildly, spanning the gamut from Regina George’s high school bully in Mean Girls to Amon Goeth’s concentration camp commandant in Schindler’s List. The essential quality is simply: this is a person who crosses the line into social immorality.

Mean Girls (2004), Paramount Pictures.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Not every story will feature a villain. However, most will, if only because a villain character provides the readers a more multi-faceted exploration of the story’s themes. The primary villain in a story will often represent what Robert McKee calls the “negation of the negation”—or the worst possible stance that can be taken to the story’s theme.

Because this negation of the negation offers the most blatant contrast to the story’s thematic Truth (as ultimately embraced by a morally positive protagonist), it is common enough for the antagonist to represent this most negative version of the story’s Lie and to, therefore, be presented as a villain. In this instance, the antagonist not only opposes the protagonist in the plot but does so in a way that is morally problematic. This provides writers with the opportunity to up the stakes, since not only will a villainous antagonist use any variety of horrifying means to defeat the protagonist, but in facing the antagonist, the protagonist will also be facing a representative of a greater evil to society.

There’s little wonder we so easily conflate antagonists and villains. Villainous antagonists are truly effective in many types of stories. The Lord of the Rings could not have been so memorable without Sauron as its representative of true evil. Batman would probably never have become a classic in his own right without the contrast of the mind-bending sadism of the Joker. The Hunchback of Notre Dame required its chilling rendition of the hypocritical and corrupt judge Frollo.

Dark Knight Rises (2012), Warner Bros.

However, it is equally possible to utilize all the drama of a good villain in your story without making that character the main antagonist. For starters, you may decide to cast the villain as the protagonist (as you might in stories with Negative Change Arcs such as The Godfather and Wuthering Heights).

The Godfather (1972), Paramount Pictures.

You may also realize that, like in The Fugitive, the best rendition of the story is served by opposing your protagonist with a morally neutral or upright antagonist, while the villain(s) are represented by supporting characters. In this film, we can know the antagonist is Gerard by examining the structural throughline, which shows Kimball consistently facing the larger antagonistic force of the U.S. Justice System, which, by the beginning of the Second Act, is personified by Gerard at all of the major structural beats.

The primary villain is kept hidden for most of the story, until his identity is revealed [SPOILER] as Kimball’s friend and fellow doctor Charles Nichols, whose hitman Frederick Sykes murdered Kimball’s wife. For most of the story, even Kimball doesn’t suspect his friend, while Sykes provides the element of immorality.[/SPOILER] The presence of a villain in what is otherwise a straightforward conflict between two morally positive men deepens the story’s palette. It raises the stakes and increases suspense by adding that element of “chaotic evil” to the mix.

Which Is Right for Your Story—Antagonist vs. Villain?Put simply, the antagonist represents the primary force that generates conflict and obstacles by opposing the protagonist’s goals, while the villain brings in the added element of objective immorality.

Every story with a forward-moving plot must include an antagonistic force. This isn’t optional. Even if your conflict is low-key, such as in cozy romances, the presence of opposition to your protagonist’s goals is what creates the story arc. In some stories this antagonistic force will be represented by a specific person who directly opposes the protagonist’s goals, sometimes not.

What is optional is whether or not your story features a villain—and whether or not this villain is the same person as your antagonist. Many stories are furthered by the inclusion of a comparatively villainous character, whether a mean neighbor or a serial killer. However, just as many stories do not require a villain, and, in some instances, might even be damaged by the inclusion of a sinister or overly dramatic element.

What’s important is for writers to understand the distinction of antagonist vs. villain and to examine their stories to determine what type of antagonist will create the most effective and entertaining plot. There are myriad ways storytellers can craft characters with depth, allowing antagonists to emerge as individuals driven by their own distinct motivations, moral quandaries, or even senses of duty. Departing from the stereotypical villain archetype allows for narratives in which the antagonist becomes a vehicle for exploring shades of gray, challenging preconceived notions, and ultimately contributing to the narrative’s richness through nuanced character development.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think is the most important distinction between antagonist vs. villain? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Antagonist vs. Villain: What’s the Difference? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 4, 2024

The 3 (Structurally) Most Important Characters

Today, I want to talk about the three most important characters from a structural perspective within your story.

Very often, two of the most common questions writers will ask about characters in their story is, “How many characters do I need and or can I have and which characters do I need? What characters are important to my specific story?”

What I’m going to be sharing in this post is definitely the stripped-down answer to this question. We’re going to be getting under the hood and looking at some of the mechanics of how story works. What I’m going to share is not necessarily meant to be taken literally. Rather, it’s meant to show you the foundation upon which you can build your entire cast of characters.

So when I say your story’s structure only needs three characters, don’t freak out! This doesn’t mean you can only have three characters in your story.

Character #1: The ProtagonistFrom a structural perspective, what actually creates plot and makes your story move?

There are three specific types of character who are important in running a story’s engine.

The first and most obvious is of course your protagonist. When we hear the word “protagonist,” very often what we think of is the hero, the main character, the good guy, something along those lines. We think of a specific type of person; we have a visual idea of what a protagonist is. Maybe you even see your protagonist from your story. However, although who your protagonist is in your story is very specific, sometimes this can distract from the deeper understanding of what “protagonist” is and how it functions within the story.

What Defines a Protagonist?Within story, all that defines the “protagonist” is that this is the person creating the forward momentum in the plot. They do that by wanting something. They have a desire, which will translate into the story goals that move them forward. In some stories, the desire may be that they want to move away from something else, but it could also be that they have something specifically in mind they’re moving toward.

You can think of this as the change you’re going to see within your story. Whether your characters know it or not, what they’re moving toward is the end of your story. They’re moving toward whatever state they’re going to be in—wherever the plot finds them—at the end of the story.

The protagonist is the one who creates that throughline and that momentum of moving through the story. Without a protagonist, we really don’t have a story. The protagonist is the person who is defining what this story is about. Theoretically, you could pick any number of specific characters within your story to be that protagonist. Each character would slightly change the nature of your plot because different characters will want different things, which drives and creates different plot. Regardless, the protagonist is the throughline.

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

You want to make sure the protagonist lines up with all of your major structural beats throughout the story. Usually, that means the character will be present at these beats, but more specifically it means that what’s happening at those structural beats needs to be in alignment with the protagonist’s forward momentum toward the end state of the story. If you can identify any particular structural beat within the story where that really isn’t happening—where they’re not moving toward that end state—then it’s probably a good sign that structural beat is off in some way.

From this perspective, the protagonist is the single most important character for defining your story’s structural throughline. They create the throughline (and the throughline should be created for them by the author). It’s a vehicle for them.

Character #2: The AntagonistThe second most important character (although really this character is equally as important as the protagonist because you need both of them) is the antagonist.

Similarly to the protagonist, we often hear that word and we think “bad guy.” We think of a morally negative person—a villain. However, this has nothing to do with being an antagonist. We only think this because, generally speaking, the protagonist is someone who’s morally positive and with whom we sympathize with from a moral point of view—and therefore the antagonist stands in opposition to that and is often characterized as someone who’s morally negative or at least ambivalent in some way.

What Defines the Antagonist?However, within storyform, functionally speaking, the antagonist is simply whatever or whoever is creating the obstacles between the protagonist and their momentum.

I often to use the term “antagonistic force” rather than “antagonist” because this also reminds us that the antagonist doesn’t have to be human. It doesn’t have to be a specific character within the story. Usually, the antagonist will be human and will be at the very least be represented at certain points throughout the story by proxy characters, which we’ll talk about in just a second. However, fundamentally, the antagonistic force is nothing more or less than whatever is creating the opposition through which the protagonist has to move.

Without the antagonistic force, without this opposition, the protagonist can move unhindered. They will move easily and smoothly toward whatever the end state is within the story. When they reach that end state, the story is over. The very fact that we have a lengthy tale to tell means that must be roadblocks—obstacles—difficulties. Conflict is encountered as the protagonist moves through the story. The antagonist is that necessary counterforce that creates that opposition for the protagonist to have to work through. This, in turn, is what creates the conflict and the interest in the plot.

Character #3: Relationship CharacterThe third character is a little more interesting in some ways and not as obvious. The third character is the relationship character. This character can actually take quite a few different forms within the story.

What Defines the Relationship Character?You might immediately think of love interest or something like that. This character could also be a sidekick. It could be any relationship within the story, but fundamentally what we’re talking about from perspective of story is a motivating force for the protagonist within the story.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Again, this can take many forms. This could be an Impact Character representing the story’s thematic Truth and prompting or inspiring change. For instance, a love interest very often will act within a character arc as someone who “rewards” or “punishes” based on the protagonist’s effectiveness within the plot (based on the protagonist’s relationship to the Lie and the Truth and how that allows them to either move forward or not against the antagonistic force).

However, the relationship character doesn’t have to be a love interest. This character simply represents a relationship that is important to the protagonist and is creating motivation for what they’re doing. This relationship character shines a light on the “why” of the protagonist’s motivation. The antagonistic force shines a light on all of the things the protagonist hasn’t dealt with or hasn’t figured out yet as a way to be able to move forward toward the end goal, whereas the relationship character is shows the broader context of why the protagonist is doing this—what they’re trying to build, why they’re trying to expand.

Again, this isn’t necessarily something the protagonist is conscious of. You’ll see this dynamic in stories, in which there needs to be that relational level so that there’s a catalyst—there’s a why behind the protagonist’s motives.

Using the Three Characters When Your Protagonist Is the Only Person in the StoryAgain, just as with the antagonistic force, this doesn’t necessarily have to be characterized. It’s entirely possible to create a story that’s about just one character. If you have just one character on stage, in that case these other two forces within the story will either be internalized within the protagonist as aspects of the protagonist ‘s own self, or they’ll be reflected somehow in the world around them, in the setting. We see this in stories such as the Tom Hanks movie Cast Away, in which he is all alone on an island.

Cast Away (2000), 20th Century Fox.

The whole story basically is him lost on an island. He’s stuck in the middle of nowhere and has to survive. The antagonistic force is mostly just the weather and the elements, with him trying to figure out how to make the island work in a way that he can survive off of it. Then later on in the story, we also see, within himself, his own difficulties, as his fear and anger and frustration also work against him. He has to work through that as a way to continue toward his end goal of getting off the island and surviving.

The relationship aspect—creating a context of meaning—is represented by his relationship with the volleyball Wilson, who he personifies—but who is, of course, really just him. Wilson gives him something to care about something, onto which he can project meaning and purpose out into the world, so he doesn’t feel so alone.

That’s a great example of how all these three of these elements work within a story without necessarily having to be represented by actual characters.

Using the Three Characters When Your Story Features a Cast Larger Than ThreeObviously, most stories will feature many, many more characters than just these three. In these cases, what is happening is that every single character within your story—even if you have hundreds of them—are related to these three primal forces within the story. They are all representing, in some way, one of these forces within your story.

What If You Have Multiple Protagonists?First, I want to talk about stories with multiple protagonists. This is an important question. From the foundational perspective of story structure, there is really only one protagonist. That is what creates the structural throughline. So if you have more than one protagonist, you necessarily have more than one structural through line—as happens in stories with multiple plotlines, which I talked about in a previous video this year.