K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 3

May 12, 2025

Now on Audio! Next Level Plot Structure

Today, I’m thrilled to announce Next Level Plot Structure is now available on audio!

I’ve heard from so many of you who were hoping for an audiobook from the very beginning—as soon as the print and digital versions launched last summer. Big thanks for hanging in there and cheering it on! I truly appreciate your enthusiasm and patience!

(And if you’re wondering, an updated audio version for the second edition of Structuring Your Novel is also coming soon!)

You can now listen to Next Level Plot Structure on all major audiobook platforms:

AudibleApple BooksGoogle PlayKoboAudiobooks.comNo matter where you like to listen, it’s ready and waiting to join you on your next walk, drive, or writing session.

Also, don’t forget that if you’re not already an Audible member, you can grab the book for free just by signing up!

About the Audio BookElevate Your Storytelling with Expert Plot Structure

Unlock the secrets of compelling storytelling with Next Level Plot Structure, a new guide from K.M. Weiland, author of the popular Structuring Your Novel. This comprehensive resource delves deep into the intricacies of plot structure, revealing the rich vein of narrative techniques and philosophical underpinnings that have shaped storytelling throughout history.

Delve beyond plot beats to explore deeper symmetry and symbolism in story.Discover how every plot beat and scene is composed of two mirroring halves, contributing to the narrative arc.Introduce readers to chiastic structure, a mesmerizing mirroring technique that unites the two halves of a story.Master the dual beats of each major plot point to create dramatic scene arcs.Explore innovative ways to structure scenes to keep readers engaged and eager to turn the page.Examine the symbolic significance of a story’s four “worlds” and their influence on plot and character arcs.Evade formulaic story structures by understanding the deeper meaning and purpose of each plot element.Whether you’re a seasoned writer or just starting out, Next Level Plot Structure provides invaluable insights and practical techniques to help you take your storytelling to new heights.

Want More Audio?Check out all of my audiobooks:

Outlining Your Novel Structuring Your Novel Creating Character Arcs Writing Your Story’s Theme Writing Archetypal Character Arcs Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration 5 Secrets of Story Structure Dreamlander Wayfarer (full-cast production!)P.S. If you’ve already read Next Level Plot Structure and enjoyed it, I would so appreciate it if you’d leave a rating or review!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s your favorite way to absorb writing craft info—reading, listening, or watching? And why? Tell me in the comments!The post Now on Audio! Next Level Plot Structure appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 5, 2025

Want to Write Better Action Scenes? Cut This One Thing

[From KMW: I’ve got a quick post for you today—a little storytelling snack—on how to write better action scenes. Specifically, we’re talking about what not to do if you want to keep your pacing tight and your scenes crackling with energy. (Hint: it’s all about trimming the fat, not the flavor.) I’ll be back next week with a full post and podcast on a juicy topic in response to one of your questions: “Using the Enneagram for Character Development: Avoiding Repetition for Lies Each Type Might Believe.”]

***

If you want to write better action scenes, the key isn’t just what you include—it’s what you leave out. Nothing kills momentum faster than a poorly timed info dump or an overstuffed description that stops the action in its tracks. Pacing is everything, and knowing how to control it can mean the difference between a scene that crackles with energy and one that fizzles before it even gets started.

You want readers to be sucked into the conflict so entirely they forget to close their mouths and stop drooling. You do this by deftly structuring the length and variables of sentences and by trimming unnecessary info that might slam the brakes on your runaway freight train of action-packed excitement. This is true no matter what type of “action” your story includes—whether it’s a chase scene, a love scene, or just an intense conversation.

One of the quickest ways to destroy any scene’s pacing is by interrupting the action with large chunks of description.

For Example:

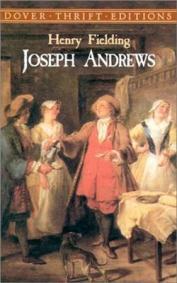

Joseph Andrews by Henry Fielding (affiliate link)

Henry Fielding’s satire Joseph Andrews (usually considered one of the first examples of the novel) acknowledges this problem, tongue in cheek.

During a tense and furious scene in which the hero helps a friend fight off a pack of attacking dogs, Fielding breaks the third wall to cheekily tell readers he would like to include a simile about now, but that he dare not interrupt the action, which he says “should be rapid in this part.”

In so explaining his reasons for not interrupting the action, Fielding, of course, brought the action screeching to a halt just as surely as if he had actually stopped to impart his simile. He was writing a satire, so he could get away with it. Most writers, however, cannot.

Writers often trick themselves into thinking descriptions are vital, when they very often are not. Just as Fielding’s action scene survived admirably without his simile, much of the information writers want to explain to readers often turns out to be deadweight.

The next time you find yourself wanting to slow down for description or explanation, double-check whether this info is vital. If you determine it is necessary, your next step should be reevaluating whether the info can be moved so it doesn’t interfere with the action. For example, if readers need this info to understand the action, make sure they’re privy to it before the bullets ever flying, the dogs ever start barking, and the train ever starts rumbling.

Trimming unnecessary description doesn’t mean stripping your scenes of depth or detail. It just means being intentional about where and how you include them. If you want to write better action scenes, focus on maintaining momentum by weaving essential details seamlessly into the flow, rather than dropping them in like roadblocks. If you keep the pacing tight, the action clear, and your readers engaged, your scenes will hit with the impact they deserve!

Wordplayers tell me your opinions! What are your favorite techniques to write better action scenes? Tell me in the comments!

The post Want to Write Better Action Scenes? Cut This One Thing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 28, 2025

The Most Dangerous Arc: Breaking Down the Corruption Character Arc

In storytelling, few arcs are as gripping—or chilling—as the Corruption Character Arc. In this arc, characters don’t just fall, they choose to fall (although, of course, they don’t generally think of it like that). Whether driven by fear, pride, or desire, they trade their integrity for a Lie, believing it will give them what they want. Even when this is true, the cost is an ever-deepening descent into self-delusion and, often, self-righteousness.

In storytelling, few arcs are as gripping—or chilling—as the Corruption Character Arc. In this arc, characters don’t just fall, they choose to fall (although, of course, they don’t generally think of it like that). Whether driven by fear, pride, or desire, they trade their integrity for a Lie, believing it will give them what they want. Even when this is true, the cost is an ever-deepening descent into self-delusion and, often, self-righteousness.

In today’s breakdown, we’ll explore how to craft this final entry—and in many ways most insidiously dangerous—in the triad of foundational Negative Change Arcs. If you’re writing a story about a character who chooses the wrong path and justifies it every step of the way, this post will offer insights into creating a devastating Corruption Arc. Throughout this month, we’ve been looking under the hood of the three foundational Negative Change Arcs.

We’ve already explored how the Disillusionment Arc bridges the Positive Change and Negative Change Arcs by forcing characters through a revelation of the thematic Truth that is so powerful it is uncertain whether they will embrace it in a way that is ultimately redemptive or will succumb to the bitterness and resistance that can lead to ever-deepening negative spirals.

We’ve also explored the Fall Arc—in which characters refuse to take that journey into the Truth at all, instead doubling down on mistaken perceptions in a way that requires an initial Lie to be bolstered many times over with further Lies, leading the character to a much more benighted state than that of the beginning.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Today, we culminate with the Corruption Arc, which presents as the mirror opposite of the Positive Change Arc. In a Positive Change Arc, characters will evolve their perceptions of themselves and the world from a limited Lie to a more expanded Truth. Oppositely, in a Corruption Arc, the character will begin in a relatively privileged and enlightened perspective, only to compromise this position through a failure in vigilance against the always present possibility of self-delusion. From there, they may well spiral ever deeper into the darkness.

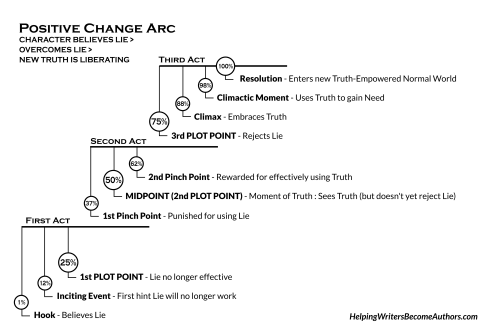

In This Article:The Corruption Arc at a GlanceIt Starts With a Lie: The Moral Weakness at the Heart of the Corruption Character ArcThe Fall Within the Corruption: Trading Truth for PowerIn the End: Self-Delusion and the Mass Spread of the LieThe Corruption Arc At a GlanceCharacter Sees Truth > Rejects Truth > Embraces Lie

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)1%: The Hook: Understands TruthThe protagonist lives in a Normal World that allows for or even encourages the thematic Truth. As a result, the protagonist starts out with an understanding of the Truth.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Temptation of LieThe Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle temptation that the Lie might be able to serve the protagonist better than the Truth.

25%: The First Plot Point: Enters Beguiling Adventure World of LieThe protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, an enticement out of the First Act’s safe, Truth-based Normal World into the Second Act’s beguiling, Lie-based Adventure World. Not realizing the danger, the protagonist is lured through the Door of No Return by the promise of the Thing the Character Wants.

The Second Act (25%-75%)37%: The First Pinch Point: Torn Between Truth and LieThe protagonist is torn between the old Truth and the new Lie. The Lie proves itself effective in moving the character nearer the Want. But the character wages an internal conflict in moving further away from old convictions and understandings of the world.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Embraces Lie Without Fully Rejecting TruthThe protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth and faces the Lie in all its power. The character recognizes the Want cannot be gained without the Lie. Although not yet willing to fully and consciously reject the Truth, the character makes the decision to fully embrace the Lie.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Resists Sacrifice Demanded by TruthThe protagonist is “rewarded” for using the Lie. Building upon what was learned at the Midpoint, the protagonist will start implementing Lie-based actions in combating the antagonistic force and reaching toward the Want. The Truth pulls on the character, demanding sacrifices too great to give. The character begins resisting the Truth more and more adamantly.

The Third Act (75%-100%)75%: The Third Plot Point: Fully Embraces LieThe protagonist utterly rejects the Truth and embraces the Lie. The character acts upon this in a way that creates a Low Moment for the world (and for the character morally, if not practically). The character is now willing to knowingly endure the consequences of rejecting the Truth in exchange for the rewards of embracing the Lie.

88%: The Climax: Final Push to Gain WantThe protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to decide whether or not the character will gain the Want. Unhampered by the Truth, the character pushes forward ruthlessly toward the plot goal.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Moral FailureThe protagonist uses the Lie in an attempt to gain the Want. The character may gain the Want and remain senseless to the evil engendered by these actions. Or the character may gain the Want only to be devastated that it wasn’t worth what was sacrificed. Or the character may fail to gain the Want and be devastated by the realization that the sacrifices to the Lie were fruitless. One way or another, the character definitively ends the conflict with the antagonistic force.

100%: The Resolution: AftermathThe protagonist must confront the aftermath of all choices. The character may turn away from the Lie, admitting mistakes and accepting consequences. Or the character may callously forge ahead, intent on continuing to use the Lie to further self-serving ends.

It Starts With a Lie: The Moral Weakness at the Heart of the Corruption Character ArcAll character arcs start with a Lie the Character Believes. This is a mistaken or limited perception of reality.

The Lie could be:

Simply a lack of information (e.g., how to overthrow the bad guy).An outright delusion (e.g., “I am the smartest person in any room”).A perspective held about one’s self that is either incorrectly positive or incorrectly negative (e.g., “I am a kind person” or “I am worthless”).An over- or underestimation of others (e.g., hero worship of a flawed leader or demeaning put-downs of certain people).An expectation of how the world works (e.g., “the deck is stacked against me” or “I deserve to have the rules bent for me”).Whatever the case, the challenge to this Lie catalyzes the beginning of every type of character arc—except the Corruption Arc. Instead, the Corruption Arc begins when a character is somehow tempted toward a more constrictive perspective. On the surface, of course, this doesn’t make sense. Why would anyone who consciously holds a relatively expanded perspective be foolish enough to willingly step into a more limited way of being?

The answer is as old as time and in many ways boils down to a Lie of its own: the characters believe they can use the Lie for their own purposes without allowing it to corrupt them. Hubris is always a factor.

Sometimes, hubris may be the main factor, in that characters feel so secure in their currently positive worldview that they believe they can risk taking a temporary step back into the shadows.

Other times, the primary motivator may be high stakes that cause characters to feel they are without choices; they understand they are not choosing an option that aligns with their integrity, but they choose anyway because they “have to” and because, again with a measure of hubris, they believe they can flirt with this seeming shortcut and still return with their integrity in tact. These characters make the fundamental mistake of believing that because they see some Truth, they are capable of seeing all of it. They believe they are capable of shining a light through the darkness they willingly choose to navigate in search of a treasure they need.

For Example:

Anakin Skywalker in Star Wars believes the Lie that power can prevent loss, leading him to embrace control as a moral justification. He also tends to conflate power with wisdom, overestimating his ability to wield power well.

Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005), 20th Century Fox.

This is what makes the Corruption Arc one of the most complex character arcs. Why? Because daring the darkness in search of a healing treasure is also the heart of the heroic Positive Change Arc, in which characters risk everything—including integrity and perspective—to seek a better way of being. In essence, that is what Corruption Arc protagonists also do—or at least this is what they tell themselves they are doing. The difference is that when the character is presented with the choice between desire and Truth (i.e., power and integrity), the Corruption Arc character’s ability to recognize or honor the latter will increasingly fail.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

The polarity of humility and hubris are present in both Positive Change and Corruption Arcs. Traditionally, Positive Change Arc characters (particularly Hero archetypes) start out with a certain measure of hubris (a form of the Lie), which they must exchange for humility as they progress the path. While Corruption Arc characters also begin with at least a hidden measure of hubris, they will end, at least in the abstract, in downfall and humiliation.

For Example:

Macbeth believes his destiny entitles him to power, which allows him to rationalize betrayal and murder.

Macbeth (2015), StudioCanal.

Ultimately, what the Corruption Arc shows us is the high cost of failing to hold our previous successes—whether material or spiritual—with the type of humility that safeguards our gains against our own capacity for delusion and regression.

The Fall Within the Corruption: Trading Truth for PowerJust as the Disillusionment Arc can be recognized as an abbreviated Positive Change Arc (stopping short before it is clear whether the character will be able to integrate a harsh Truth into a greater good), the Fall Arc (which we discussed last week) can be recognized as an abbreviated Corruption Arc. In this case, the Fall Arc represents the latter part of the Corruption Arc, after characters have adopted the Lie and now must work double-time to bolster that Lie with even more Lies.

You’ll remember that the Fall Arc shows a character who refuses to accept the challenge of the Truth and from there devolves into a much worse Lie, all in an effort to protect that initial (often quite small) Lie.

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The Corruption Arc begins before this point, revealing a character who likely has more mental or moral capacity for recognizing comparative Lies and Truths. This is a character who has achieved some level of personal integrity, which has now brought them to a place of testing. The central question is whether they will compromise their understanding of their own personal Truth (aka, their integrity) in exchange for a measure of power.

For Example:

Walter White in Breaking Bad begins manipulating, lying, and killing as he clings to power, convincing himself it’s for his family—when it’s really about ego.

Breaking Bad (2008-2013), AMC.

What always makes this invitation to power tempting is that it is, essentially, a shortcut. Whatever the practical mechanics of the plot, we know this is a shortcut on a character level because it prompts the character to take the “easy route” in defiance of a deeper sense of personal right and wrong. At some level, the Corruption Arc character will always know this, and in more nuanced stories, will often be shown to struggle with it. In short, they make an informed choice. They are not ignorant about what they are choosing. They understand it is against their deepest self, and they understand the possibility of untoward consequences to themselves, or more likely, to others. They do it anyway.

From there, the characters’ journey will begin to mirror the Fall Arc. In order to protect this one out-of-integrity choice, characters begin justifying their actions with an ever-deepening slide into delusion. From believing they “had no choice” or “no one would get hurt,” they will begin to adopt perspectives that insist “they were in the right” or even “they were acting in everyone’s best interest” or “they knew better than the ignorant masses.”

For Example:

Gollum in The Lord of the Rings slowly abandons his identity and humanity, letting the Ring reshape his very soul for the sake of possessing it.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), New Line Cinema.

In the End: Self-Delusion and the Mass Spread of the LieThe tragedy of the Corruption Arc is its excruciatingly slow slide away from wholeness into delusion. Corruption Arc characters very often end by achieving their goals. Thanks to the devil’s deal in which they sell their souls, they may well gain tremendous power and influence within their personal spheres. In the end, some characters may retain enough sense of their personal Truth to wake up to the horrors they have wrought in their own lives and others, in which case the victory for which they have sacrificed so much will prove horrifyingly empty. In other stories, characters will end by fully embracing their new Lie-based identity. Not only will they become the monster they initially believed they could resist, they may even fully condone what they have become.

For Example:

Michael Corleone in The Godfather exemplifies a Corruption Arc character who justifies his increasingly immoral actions by convincing himself they are necessary for protecting his family. He eventually becomes fully immersed in the darkness he once resisted. By the end, Michael’s self-delusion is so complete he not only believes his choices are justified, he also pulls others into his moral decay, perpetuating the destruction of those around him.

The Godfather (1972), Paramount Pictures.

Those Corruption Arcs that do not end with the characters achieving a redemptive sense of humiliation at what they have become will instead end with the character in a state of grotesque self-righteousness. They will justify their choices by any means necessary, no matter the consequences heaped upon others. Like the Fall Arc, the Corruption Arc character’s self-delusion in the end may be so complete and compelling that it also warps the perception of others, pulling them down into the darkness as well.

For Example:

By the time we meet President Snow in The Hunger Games, he’s wholly consumed by the belief that fear is the only way to ensure social stability. He’s convinced himself that this Lie is not only necessary but noble. He enforces it with ruthless propaganda, manipulation, and death. He’s not just corrupted himself; he’s built an entire system on his delusion.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

***

The Corruption Arc reminds us that character arcs are not just about change but about choice. Of all the Negative Change Arcs, the Corruption Arc may be the most haunting. It doesn’t happen to the character; it happens because of the character. The central danger isn’t ignorance or even resistance to the Truth, it’s the conscious decision to turn away from it. When well-written, these arcs offer some of the most compelling, nuanced, and tragically human stories. As writers, exploring this arc challenges us not just to understand the psychology of our characters, but to confront the darker possibilities within ourselves.

In Summary:The Corruption Arc is a powerful exploration of a character’s conscious choice to embrace a Lie, despite knowing the Truth. Unlike the other Negative Change Arcs, which often involve ignorance or self-deception, the Corruption Arc is chilling precisely because it requires awareness. The character sees the Truth, but chooses not to follow it. This makes the arc uniquely tragic, as it dramatizes not just a character’s fall, but the moral failures leading up to it.

Key TakeawaysThe Corruption Arc centers on a character who knows the Truth but deliberately endangers it.This arc is defined by conscious moral compromise in pursuit of power, security, or other personal goals.The arc usually starts from a place of strength or clarity, making the fall more impactful.Unlike the Disillusionment Arc (which involves a painful but authentic awakening), the Corruption Arc is about the willful embrace of the Lie.This arc creates deeply human and emotionally resonant stories, especially when the character’s motivations are understandable or even sympathetic.Writing a Corruption Arc challenges authors to grapple with the complexity of choice, consequence, and morality.Want more?

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

If you’re intrigued by the emotional and thematic power of the Corruption Arc, you’ll find even more in-depth guidance in my book Creating Character Arcs. It walks you step-by-step through how to craft compelling transformations—Positive, Flat, and Negative—and how to seamlessly weave them into your plot. Whether your characters are resisting change or spiraling toward it, the tools inside will help you bring their arcs to life. It’s available in paperback, e-book, and audiobook (along with its companion guide the Creating Character Arcs Workbook).

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever written a Corruption Character Arc or considered one for your protagonist or antagonist? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Most Dangerous Arc: Breaking Down the Corruption Character Arc appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 21, 2025

Writing a Fall Arc: How to Show a Character’s Moral Decline

When writing a Fall Arc, writers get to explore the slow, often heartbreaking process of moral or emotional decline. In this type of Negative Change Arc, the characters’ refusal to change or acknowledge their flaws becomes a central theme. They hold onto a Lie—a deeply ingrained belief or limited perception of the world—that drives their actions and decisions. Over time, this self-deception evolves into something darker, affecting not just their own choices, but their relationships with others. Understanding how to write a Fall Arc can help you create a character whose downfall feels deeply tragic and engaging.

When writing a Fall Arc, writers get to explore the slow, often heartbreaking process of moral or emotional decline. In this type of Negative Change Arc, the characters’ refusal to change or acknowledge their flaws becomes a central theme. They hold onto a Lie—a deeply ingrained belief or limited perception of the world—that drives their actions and decisions. Over time, this self-deception evolves into something darker, affecting not just their own choices, but their relationships with others. Understanding how to write a Fall Arc can help you create a character whose downfall feels deeply tragic and engaging.

In some ways, the Fall Arc is the darkest of the three Negative Change Arcs. Although not as potentially redemptive as the Disillusionment Arc (which hints characters may continue their growth into a completed Positive Change Arc sometime in their future) or as tragic as the Corruption Arc (which offers the character a true chance of recovery that is refused and which we will discuss next week), the Fall Arc is still, for my money, the quintessential Negative Arc.

The Fall Arc offers an extraordinarily powerful window into the dark possibilities for devolution found within humanity’s tremendous capacity for self-deception. More than that, it reveals our almost primal willingness to defend that self-deception even at crippling personal cost, certainly on a spiritual level, but often on a practial level as well.

Inspired by ponderings from my own life, I wanted to revisit this fundamental character arc to explore some of the nuances of the character’s fall from grace. What creates this fall? Why are even intelligent and “good” people susceptible to this insidious degradation? And how can you craft Fall Arcs in your own stories that ring true to the patterns of real life? Let’s take a look!

In This Article:Writing a Fall Arc: At a GlanceThe Catalyst of a Fall Arc: The Character’s Refusal to ChangeThe “Worse Lie” in a Fall Arc: How Smaller Lies Protect the Character’s Self-DeceptionIn the End: Character’s Self-Deception Decays Into an Outward Deception of OthersWriting a Fall Arc: At a GlanceLet’s start with an overview of the arc itself. Like its brethren, the Positive Change Arc and the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc begins with the Lie the Character Believes. From there, it deviates into darker and less redemptive territory, as the character proves willing to take whatever measures necessary to defend that belief—no matter how increasingly dysfunctional it may prove.

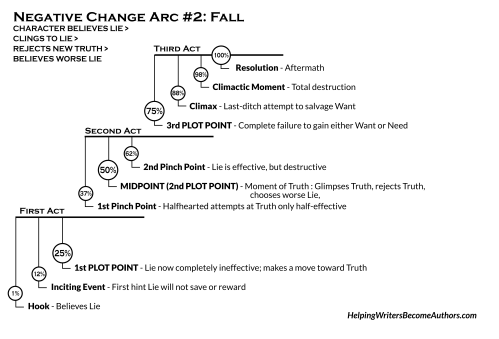

Character Believes Lie > Clings to Lie > Rejects New Truth > Believes Worse Lie

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

1%: The Hook: Believes LieThe protagonist believes a Lie that has so far proven necessary or functional in the existing (often destructive) Normal World.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Hint Lie Will Not Save or RewardThe Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle hint that the Lie will no longer effectively protect or reward the protagonist in the current circumstances.

25%: The First Plot Point: Lie Now Completely IneffectiveThe protagonist is faced with a consequential choice in which the “old ways” of the Lie-ridden First Act prove ineffective in the face of the main conflict’s new stakes. The protagonist is given an early choice between old Lie and new Truth. The character passes through a Door of No Return, which forces the character to leave the Normal World of the First Act and enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Halfhearted Attempts at Truth Only Half-EffectiveThe protagonist may try to wield the Truth as a means of gaining the Thing the Character Wants, but does so only with limited understanding or enthusiasm. The character is stuck in a limbo-land where the old Lie is no longer a functional mindset, but where halfhearted attempts at the Truth prove likewise only half-effective.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Glimpses Truth, Rejects Truth, Chooses Worse LieThe protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth, coming face to face with the thematic Truth (often via a simultaneous plot-based revelation about the external conflict). This is the first time the protagonist consciously sees the full power and opportunity of the Truth. However, the character also sees the full sacrifice demanded in order to follow the Truth. Unwilling to make that sacrifice, the character rejects the Truth and chooses instead to embrace a Lie that is worse than the original.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Lie Is Effective, But DestructiveUncaring about the consequences, the protagonist wields the Lie well and finds it effective in moving toward the Want. However, the closer the character gets to the plot goal, the more destructive the Lie becomes both to the character and the surrounding world.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

Next Level Plot Structure (Amazon affiliate link)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Complete Failure to Gain Either Want or NeedThe protagonist is confronted by a Low Moment, experiencing a complete failure to gain the Want. This failure is a direct result of the collective damage wrought by the Lie in the Second Half of the Second Act. The “means” caught up to the character before the “end.” However, even when faced by all the evidence of the Lie’s destructive power, the protagonist still refuses to repent or turn to the Truth.

88%: The Climax: Last-Ditch Attempt to Salvage WantUpon entering the final confrontation with the antagonistic force, the protagonist doubles down on the Lie in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the Want.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Total DestructionCrippled by the Lie (in both the internal and external conflicts), the protagonist is unable to gain the Want (or gains it only to discover it is useless). Instead, the character succumbs to total personal destruction.

100%: The Resolution: AftermathThe protagonist must confront the aftermath of all choices. The character may finally and futilely accept the inescapable Truth. Or the character may be left to cope, blindly, with the consequences of choices.

The Catalyst of a Fall Arc: The Character’s Refusal to ChangeLike the Positive Change Arc and the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc character’s story begins when the protagonist is prompted to examine the limitations of the central Lie the Character Believes. Although this may be a literal deception in some senses, the Lie is most properly understood as a limited perspective. As such, it begins as an entirely normal and germane part of any human’s life.

For Example:

In Les Misérables, Inspector Javert’s inability to accept moral complexity leads him deeper into his own self-deception, ultimately making him incapable of seeing a world beyond his rigid belief system.

Les Misérables (2012), Universal Pictures.

We all hold countless limited beliefs. Indeed, arguably, all our beliefs about ourselves and reality are limited. To the degree we accept this and are willing to embrace change as new information and experience allows us to refine and expand those beliefs, this is simply part of the regenerative cycle of life. However, when this cycle is derailed by an unwillingness to accept corrections to our perception of reality, the result can be increasingly destructive for both the individual and, eventually, everyone in the vicinity.

Creating Character Arcs Workbook

Although Fall Arcs often look, at first glance, to be huge stories of great downfalls, they often have humble beginnings. The initial Lie the Character Believes will likely be something quite small and innocuous.

For Example:

The original Lie could be something as simple as refusing to accept responsibility in a relationship spat: “It’s not my fault.”

From there, characters who are truly doomed will find they must bolster this initial Lie with further arguments: “It’s her fault. I’m in the right. I’m righteous. I’m a victim. She’s selfish. She’s a narcissist. Etc.”

From here, the corruption can grow to truly staggering heights, as characters’ resistance to reality may even lead them to become the worst version of the very thing they are denying: e.g., the character becomes the narcissist.

Varying stories tackle this downfall to different degrees. Some may reveal the more mundane face of the Fall Arc, in which the character’s Lies are “small” enough not to interfere greatly with everyday functionality. In other stories, the character will be shown to fall all the way into the very pit of dark possibilities.

For Example:

In Nightmare Alley, Stan Carlisle begins the story as an ambitious, though morally compromised, man. He wants to climb out of his working-class roots and build a life of wealth and influence, but he’s driven by the wrong motivations: greed, ego, and a desire for status. At first, he tries to justify his actions, believing he’s in control of the people around him. However, his increasingly manipulative behavior, deceit, and manipulation spiral out of control, leading him further down a path of moral decay and self-destruction. His delusions of grandeur and the belief that he can outsmart everyone are his undoing.

Nightmare Alley (2021), Searchlight Pictures.

In either case, the Fall Arc reveals a deadly spiral. As the character devolves from Lie to worse Lie, the possibility grows ever greater that the spiral will continue with the character veering further and further into delusion.

The “Worse Lie” in a Fall Arc: How Smaller Lies Protect the Character’s Self-DeceptionFor simplicity’s sake, I refer to the end state of a Fall Arc character as the “worse Lie.” As you can see, however, what this worse Lie really amounts to are many “smaller” Lies eventually built into a grand illusion.

For Example:

In Black Swan, Nina begins with the small self-deception that she must be “perfect.” This Lie snowballs into a worse Lie: that she must destroy herself to achieve perfection, something that happens piece by piece and moment by moment throughout her story.

Black Swan (2010), Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Understanding this important nuance makes it possible to write a much more compelling and realistic Fall Arc. In real life, it is rare for a person to grandiosely self-delude except in situations of tremendous trauma or high stakes. Most of the time, the slide into delusion is the result not of one bad decision or perception, but of a continuing refusal to accept and confront reality.

The character may do this for any number of reasons. Almost always, those reasons amount to a primal need to protect the status quo. One of the great ironies of human life is that even though change is requisite for survival, our brains and nervous systems are wired to preserve the status quo at almost any cost. We do this not just to maintain the equilibrium our nervous systems desire, but also, by extension, to preserve the ego identities we use as coping mechanisms.

Not only are we are capable of believing in just about anything, but we also tend to incorporate those beliefs into our very identities—so that to challenge the belief feels like a threat to our very existence. This is why we appreciate heroic stories of Positive Change Arcs; they demonstrate the tremendous courage required to accept challenges to our beliefs, identities, and ways of being. In most instances, it is much easier to stuff away the cognitive dissonance whenever we are presented with a piece that doesn’t fit. It is easier to ignore the (millions) of nuances that challenge our tidy narratives every single day.

The catalysts that create stories of all types are those that interrupt a character’s life with such force that change becomes inevitable. Characters must either courageously face the catalyst and learn to expand themselves—or refuse the call and instead, inevitably, change negatively by increasingly restricting their view of reality and their capacity to expand.

For Example:

In Gone Girl, Amy Dunne begins her deception by crafting a small Lie—that she’s the perfect wife. Over time, this self-image morphs into a grander fabrication, where she not only deceives herself but manipulates everyone around her into believing her version of reality.

Gone Girl (2014), 20th Century Fox.

Powerful Fall Arcs show us the peril of refusing to claim courage and Truth. They also show, poignantly, how even the smallest of initial denials can eventually snowball into “worse Lies” that utterly crack an individual’s personal integrity.

In the End: Character’s Self-Deception Decays Into an Outward Deception of OthersIn the worst scenarios, the Fall Arc character’s warping of reality can become so insistent and powerful that it harms others. Sometimes, this can be the result of others being similarly deceived by the protagonist’s insistence that the Lie is, in fact, true. Most often, the negative effect will result from the protagonist’s unwillingness to maintain crucial integrity in relationship with, first, themselves, then others, then the world at large. Depending on the power the character wields, the effect of one character’s insistence on a Lie can have truly horrifying effects upon an entire community—or even the world, as witnessed in the demagogues of World War II.

For Example:

A media mogul obsessed with power and control, Kane in Citizen Kane starts off deluded by the belief that wealth and influence can buy love and happiness. His inability to confront emotional truths and his manipulation of public opinion leads him deeper into isolation. As he clings to a distorted version of reality, his relationships deteriorate, and his empire collapses.

Citizen Kane (1941), RKO Radio Pictures.

How far you decide to take your Fall Arc will depend on the needs of your story. The effects can range all the way from characters who simply “miss the boat” because they lack the courage to hop on, to characters who severely limit or even destroy their lives, to characters who sway others into mass delusion.

In the end, the Fall Arc is a slow unraveling into self-deception. Characters cling ever more desperately to a Lie that will ultimately destroy them. The Fall Arc is a story of tragic inevitability. The character could have changed—but failed to embrace the courage of honesty before it’s too late.

Understanding this arc allows writers to craft deeply compelling character journeys that feel heartbreakingly true to life. The best Fall Arcs resonate because they reflect something deeply human: our resistance to change, our desperate need to justify our choices, and the ways in which small Lies, if left unchecked, can spiral into something far more destructive. Whether your character’s downfall is quiet or cataclysmic, mastering this arc can add powerful layers of complexity to your storytelling.

In SummaryThe Fall Arc is a Negative Change Arc that follows characters’ gradual descent into destruction as they cling to a Lie that ultimately undoes them. Unlike other Negative Arcs that allow for redemption or a conscious embrace of darkness, the Fall Arc is defined by missed opportunities for growth, making it one of the most tragic and compelling character journeys.

Key TakeawaysThe Fall Arc is a slow unraveling, marked by a character’s increasing self-deception.Unlike the Disillusionment Arc, there is no ultimate redemption.Unlike the Corruption Arc, the character is not making a conscious choice to embrace darkness, but rather resisting “the light” of a difficult Truth.The tragedy of this arc lies in the fact that the character could have changed but refused to.This arc reflects real human struggles—resistance to change, justification of bad choices, and the compounding consequences of small lies.Want more?If you’re fascinated by the darker sides of character arcs, check out my email course Shadow Archetypes: Writing Complex Fictional Characters. This course dives deep into the psychological underpinnings of morally gray characters, tragic figures, and antiheroes. Learn how to craft compelling, multi-dimensional characters who wrestle with their own inner demons.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What challenges have you encountered when writing a Fall Arc? Do you struggle more with crafting the character’s moral descent, keeping them relatable, or nailing the ending? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Writing a Fall Arc: How to Show a Character’s Moral Decline appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 14, 2025

Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth

The Disillusionment Arc is one of the most powerful and emotionally resonant transformations a character can undergo. At its core, this arc is about awakening—shedding comforting illusions to face a stark and often uncomfortable Truth. While it shares similarities with the Positive Change Arc, the Disillusionment Arc doesn’t always lead to a hopeful resolution. Instead, it challenges both the characters and the audience to grapple with the weight of reality. However, despite its seemingly bleak nature, the Disillusionment Arc isn’t inherently negative. It reflects a fundamental aspect of human growth: the process of seeing the world as it truly is and deciding what to do with that knowledge.

The Disillusionment Arc is one of the most powerful and emotionally resonant transformations a character can undergo. At its core, this arc is about awakening—shedding comforting illusions to face a stark and often uncomfortable Truth. While it shares similarities with the Positive Change Arc, the Disillusionment Arc doesn’t always lead to a hopeful resolution. Instead, it challenges both the characters and the audience to grapple with the weight of reality. However, despite its seemingly bleak nature, the Disillusionment Arc isn’t inherently negative. It reflects a fundamental aspect of human growth: the process of seeing the world as it truly is and deciding what to do with that knowledge.

Although I have always classed the Disillusionment Arc as one of the three primary Negative Change Arcs, in many ways it is more of a bridge between the two heroic arcs—Positive Change and Flat—and the two decidedly Negative Arcs—the Corruption Arc and the Fall Arc (more on the Fall Arc next week!). Because of this, the Disillusionment Arc is the “lightest” of the Negative Arcs, not only because it is the only Negative Arc to end with the protagonist’s awareness and acceptance of the story’s thematic Truth, but also because it is the only Negative Arc to end with the characters standing at a crossroads that may eventually allow them to return to a holistic and life-affirming perspective. Indeed, the comparative “negativity” of various Disillusionment Arc stories depends largely on the degree to which characters are embittered by the disillusioning new insights they have recognized.

I tend to focus most of my teaching on Positive Arcs, not only because I am more drawn to writing them, but also because they form the foundation from which the deviations of the Negative Arcs emerge. However, lately, I have been considering the intrinsic importance of the Disillusionment Arc to the human experience.

The Disillusionment Arc is unlike the other Negative Arcs, which are arguably unnecessary for growth (i.e., with awareness, skill, and arguably a little luck, they can be bypassed). In contrast, the Disillusionment Arc is another face of the Positive Change Arc—a more difficult version of the Positive Change Arc. Even though we call it the Disillusionment Arc (mostly to indicate its darker and more depressing tone), it offers a transformation that can sometimes be even more heroic than the Positive Change Arc, since it involves recognizing and accepting a Truth that does not directly benefit the protagonist.

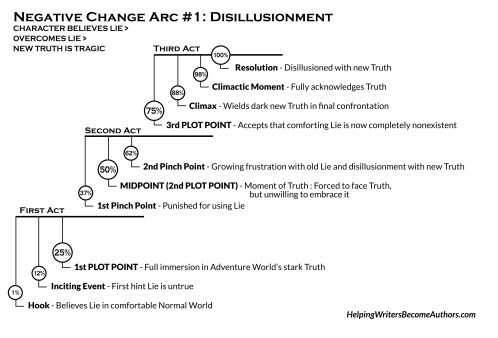

In This Article:The Disillusionment Arc at a GlanceAwakening to Truth: How the Disillusionment Arc Resembles the Positive Change ArcA Bitter Truth: Where the Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling Takes a Darker TurnIn the End: How Characters in a Disillusionment Arc Face Their New RealityThe Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling at a GlanceCharacter Believes Lie > Overcomes Lie > New Truth Is Tragic

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The First Act (1%-25%)1%: The Hook: Believes Lie in Comfortable Normal WorldThe protagonist believes a Lie that has so far proven necessary or functional in the existing Normal World, which is often a comfortable and complacent place.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Hint Lie Is UntrueThe Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle hint that the Lie will no longer serve the protagonist as effectively as it has in the past.

25%: The First Plot Point: Full Immersion in Adventure World’s Stark TruthThe protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, in which the comfortable “old ways” of the Lie-ridden First Act prove ineffective in the face of the main conflict’s new stakes. The protagonist will pass through a Door of No Return to enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act, confronted by a stark and painful new Truth.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Punished for Using LieThe protagonist is “punished” for using the Lie. In the Normal World, the character was able to use the Lie to get the Thing the Character Wants. But in the Adventure World, this is no longer a functional mindset. Throughout the First Half of the First Act, the character will try to use the old Lie-based mindset to reach important goals and will be “punished” by failures until the character begins to learn how things really work.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Forced to Face Truth, But Unwilling to Embrace ItThe protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth and comes face to face with the thematic Truth (often via a simultaneous plot-based revelation about the external conflict). This is the first time the protagonist consciously recognizes the Truth and its power. However, the character is horrified by the implications of this dark new Truth. Although no longer able to deny the Truth, the character is unwilling to fully embrace it or to surrender the comparatively wonderful old Lie.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Growing Frustration With Old Lie and Disillusionment With New TruthThe protagonist is forced to confront consistently increasing examples of the Lie’s lack of functionality in the real world. The character grows more and more frustrated with the Lie’s limitations and begins to accept the horrible Truth. The character is profoundly disillusioned by this new worldview, even as there are “rewards” for using the Truth to reach for the Want.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

Next Level Plot Structure (Amazon affiliate link)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Accepts That Comforting Lie Is Now Completely NonexistentThe protagonist is confronted by an irrefutable Low Moment, in which it is no longer possible to deny that the dark Truth is not true. The character must not only accept this new Truth, but also admit the comforting old Lie is now completely nonexistent.

88%: The Climax: Wields Dark New Truth in Final ConfrontationThe protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to discover whether or not it is possible to gain the Want. Directly before or during this section, the character consciously and explicitly embraces and wields the dark new Truth.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Fully Acknowledges TruthThe protagonist uses the Truth and all its lessons to gain the Need. Depending on the nature of the Truth, the character may also gain the Want (only to discover that, in light of all this new knowledge, it is diminished or even worthless), or the character may sacrifice the Want for the greater good. As a result, the character definitively ends the conflict with the antagonistic force.

100%: The Resolution: Disillusioned With New TruthThe protagonist either enters a new Normal World or returns to the original Normal World, but with a jaded eye in light of the new Truth.

Awakening to Truth: How the Disillusionment Arc Resembles the Positive Change ArcAs you can see, the Disillusionment Arc looks very similar to the Positive Change Arc:

Character Believes Lie > Overcomes Lie > New Truth Is Liberating

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

Apart from Disillusionment Arcs’ darker tone, the major difference is the character’s response to the newly recognized Truth at the end of the story.

From this, we can see how the Disillusionment Arc isn’t as inherently negative as it may sometimes feel. Certainly, to anyone going through a Disillusionment Arc, it can feel quite negative, since the dismantling of cherished and comfortable personal perspectives can be excruciatingly painful. Little wonder we may fight tooth and claw to avoid change, rather than courageously and consciously embracing it. Indeed, the very fact that evolution must move from unconsciousness to consciousness makes it more likely that catalysts will initially be greeted with the ignorant resistance we see embodied in Disillusionment Arcs.

In fact, we can think of the relationship between the Positive Change Arc and the Disillusionment Arc as that of nesting dolls. Within every Positive Change Arc is a Disillusionment Arc.

The Third Plot Point in a Positive Change Arc (i.e., the Low Moment) is where the character fully faces the disillusionment—and then rises above it into integration.

For Example:

In The Dark Knight, Bruce Wayne is torn apart by the Joker’s systematic attacks upon his ethos. In the end, he embraces all he has learned at great cost to himself, in order to incorporate these tragic new Truths into his larger commitment to using the Batman identity to protect Gotham.

The Dark Knight (2008), Warner Bros.

In contrast, the Disillusionment Arc’s psychological evolution ends at the low point of disillusionment, postponing future integration, perhaps indefinitely.

For Example:

In Silence, the missionary protagonist’s worldview and faith paradigm are systematically destroyed until finally he must accept that denial of his faith is the only way to survive. This is not a Truth he ever fully integrates, as he is shown to struggle between the inner and outer dissonance of these two perspectives for the rest of his life.

Silence (2016), Paramount Pictures.

A Bitter Truth: Where the Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling Takes a Darker TurnAs you can see, the major difference between the Positive Change Arc and the Disillusionment Arc is that the Truth the characters learn in the latter turns out to be distasteful and perhaps even personally destructive.

Although the Truth in a Positive Change Arc may require deep commitment and even sacrifice, the story will end with characters having fully integrated that Truth as a lost piece of themselves—allowing them to end in a place of greater wholeness.

For Example:

In Glory, Captain Shaw sacrifices his life fighting alongside his men in one of the first Black regiments in the Civil War. Despite his tragic death, he ends as a more whole and noble person, having evolved his own narrow views.

Glory (1989), Tri-Star Pictures.

In contrast, the Disillusionment Arc ends prior to integration. Characters have accepted the Truth and perhaps even acted upon it, but they have not embraced or integrated it into a new identity. Their previous worldview and ego identity have been shattered, and they have not yet been able to put the pieces back together.

For Example:

Training Day shows its idealistic rookie cop shattered by the corruption he has witnessed. Because the character was able to keep his moral core intact throughout the movie, viewers may extrapolate that he will find the strength and courage to use the difficult Truth he has learned to eventually rise into a better version of himself. But the story ends on a downbeat while the character still suffers from the destruction of what had previously seemed an intact worldview.

Training Day (2001), Warner Bros.

In the End: How Characters in a Disillusionment Arc Face Their New RealityAt the beginning, I mentioned that the Disillusionment Arc may be seen as a bridge between the Positive Arcs and the Negative Arcs. One of the reasons for this is that it is the most unfinished of the arcs. It ends with the character at a crossroads. On the one hand, they have learned something “positive”—in that Truth is always an avenue of growth and therefore healing. On the other hand, they have experienced something “negative”—in that the Truth shredded their lives and/or seems to be saying something completely undesirable about the nature of reality.

Most Disillusionment Arcs end with the character’s disillusionment. That emotion is the final beat. Where the character will go from there is left open.

There are two possibilities for the character’s future:

Option #1 is that the character will eventually integrate the difficult new Truth into a more expansive and holistic identity and ego container. In this case, the character will be primed to finish a Positive Change Arc and perhaps even move into a Flat Arc role, in which they will be capable of inspiring others who are struggling on the same path.

For Example:

We can see this in the movie Promised Land, in which Matt Damon’s character accepts what he has learned about the corruption of the natural gas companies he works for—leaving behind his well-intentioned but naive belief that he is accomplishing something positive in people’s lives. Although disillusioned, he maintains enough faith in himself and others to join a new community and keep moving forward toward a new way of being.

Promised Land (2012), Focus Features.

Option #2 is that the character’s disillusionment will sour into bitterness. Instead of integrating the new Truth and expanding into a new personality large enough to grapple with it and ultimately use it positively in the world, the character will instead resist the Truth—leading to denial, even more limited perspectives (i.e., Lies), and eventually worse corruption still. This sets the character up for a subsequent Fall Arc (which evolves from Lie to worse Lie—and which we will be exploring next week) or a Corruption Arc (which evolves from Truth to worse Lie).

For Example:

The plot of Memento is literally a search for the Truth—as the protagonist, a man suffering from short-term memory loss—struggles to remember enough to solve the mystery of his wife’s murder. By the end, he learns the Truth that he is perpetuating his violent revenge even though those responsible are already dead. The final scene indicates he will refuse to record this Truth for his future self to remember, instead sliding into an ever-deeper spiral of self-deception and corruption.

Memento (2000), Summit Entertainment.

***

In conclusion, it’s important to remember that even though this arc may end in disillusionment, it still offers a crucial space for growth. The Disillusionment Arc serves as a profound exploration of the human experience. It challenges characters—and by extension, the audience—to confront uncomfortable Truths. These uncomfortable Truths, and the realistic portrayal of how difficult it can be to integrate them, reveal transformations just as impactful as those in aspirational narratives.

Disillusionment Arcs pave the way for deeper understanding about potential transformations. The emotional depth of this arc lies in its ability to expose the fragility of our beliefs—and our own personal resilience in the face of that ongoing fragility. Ultimately, whether characters move toward integration or toward bitterness, the journey offers a powerful reflection on the complexities of facing painful Truths.

In Summary:The Disillusionment Arc in storytelling revolves around a character awakening to an uncomfortable thematic Truth, often at great personal cost. Unlike the Positive Change Arc, the Disillusionment Arc doesn’t always lead to a hopeful resolution. Instead, it challenges the protagonist—and the audience—to confront the stark realities of life. Although dark and difficult, this arc plays a crucial role in human growth, offering a transformation that involves painful yet profound insights. It serves as a bridge between the Positive and Negative Change Arcs, in that characters who face these harsh and disillusioning Truths are left at a crossroads from which they may either integrate the lessons or spiral into bitterness.

Key Points:The Disillusionment Arc in storytelling involves characters realizing a painful Truth that shatters previously held beliefs.This arc is not inherently negative, as it reflects essential human growth through facing difficult realities.It typically ends with the character at a crossroads, poised for either positive change or further resistance and denial.The Disillusionment Arc can bee seen as a bridge between the Positive Change and the Negative Change Arcs, with the potential for characters to evolve into more complex versions of themselves or to sink into corruption.Characters in Disillusionment Arcs will struggle with integrating the new Truth, leading to either deeper growth or deeper bitterness.Want More?

Creating Character Arcs Workbook

If you’re fascinated by the nuances of character development, including the Disillusionment Arc, my Creating Character Arcs Workbook is the perfect resource to help you craft complex, compelling characters. Packed with exercises and practical tips, it will guide you through detailed beat sheets and exercises for five primary character arc types—the Positive Change Arc, the Flat Arc, the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc, and the Corruption Arc. Whether you’re exploring a Disillusionment Arc or another iteration, I designed this workbook to help you structure your characters’ journeys for maximum impact. It’s available in paperback and e-book (along with its companion guide Creating Character Arcs).

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you see the Disillusionment Arc in storytelling impacting your characters’ growth? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 7, 2025

The Power of Unspoken Words: How to Write Subtext in Fiction

[From KMW: I’m taking a quick sabbatical this week. I’ll be back next Monday with a post/podcast about “The Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth.” Until then, I hope you enjoy this short post on the important topic of how to write subtext in fiction!]

[From KMW: I’m taking a quick sabbatical this week. I’ll be back next Monday with a post/podcast about “The Disillusionment Arc in Storytelling: A Powerful Tool for Character Growth.” Until then, I hope you enjoy this short post on the important topic of how to write subtext in fiction!]

One of the most powerful tools in a writer’s arsenal is subtext. This is the art of letting readers figure things out for themselves. When you know how to write subtext in fiction, you can create deeper, more engaging stories that invite readers to lean in, pick up on subtle cues, and connect with your characters on a whole new level.

But how do you strike the right balance between clarity and mystery? Let’s take a look at how to write subtext in fiction in a way that keeps readers hooked without leaving them in the dark.

It’s the writer’s job to make sure audiences have no trouble understanding what’s going on in a story. If the antagonist is ugly, maybe you make that plain by showing off his hairy wart and leering grin. If the protagonist has lived a hard life, you make sure your audience knows that by showing the fireplace your character had to sweep out and the cinders all over her dress. And if the protagonist has come up with a brilliant plan to save the day, you need, at the very least, to hint to your audience that the cavalry is on the way.

Keeping your audience in the loop is vital to presenting a pleasant and rewarding reading experience. But there are times when you do yourself a disservice by telling your audience what’s what—particularly when whatever it is may already be evident to an insightful reader.

How to Write Subtext in Fiction the Right Way

Pawn of Prophecy by David Eddings (affiliate link)

Fantasy veteran David Eddings obviously knew. About halfway through his book Pawn of Prophecy, he offers a prime example of why refraining from telling the audience something can sometimes pull them into a deeper collusion with the writer—sort of like a conspiratorial tap on the nose between writer and audience.

For Example:

In Pawn of Prophecy, Eddings makes it clear one of his characters is in love with a woman he has no hope of marrying.

But Eddings doesn’t actually say that. After having the narrating protagonist describe the lovelorn character’s interaction with the woman, all he writes is that a “self-mocking smile” flickered across the character’s face and that the narrating character then “saw the reason for Silk’s sometimes strange manner. An almost suffocating surge of sympathy welled up in his throat.”

That’s it.

But that’s enough for readers to clearly understand what’s going on beneath the surface of this scene and these characters’ interactions.

The trick to making this kind of subtext work is based primarily on the author’s ability to show readers what’s going on. If you’re able to suitably dramatize your characters’ actions and reactions, you audience will often glean such a vivid and personal picture of what’s going on that they’ll understand, without being told, exactly what characters are thinking.

However, you must also be careful not to go overboard, since you don’t want to leave your audience confused. Make certain all the pieces are in place, so your audience will be able to put them together to form a flawless picture.

Mastering how to write subtext in fiction is all about trusting your readers. When you give them just enough information to piece things together on their own, you create a more immersive and rewarding reading experience. The key is striking the right balance. You want to show enough to make your meaning clear without over-explaining. When done well, subtext draws readers deeper into your story, making them feel like insiders rather than just spectators. The next time you’re tempted to spell something out, take a step back and ask yourself: what can you show instead of tell?

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you approach writing subtext in your own stories? Tell me in the comments!Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Power of Unspoken Words: How to Write Subtext in Fiction appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 31, 2025

How Writers Can Use the Four Stages of Knowing in Character Arcs

Great character arcs are built on transformation, and one of the most powerful frameworks for understanding this journey is the four stages of knowing in character arcs. These stages map a character’s growth through initiation to enlightenment to integration in a way that feels deeply satisfying to readers. Why? Because it is yet another way in which the shape of story mirrors the patterns of real life. Once you can see how plot structure challenges characters to grow (sometimes successfully, sometimes not), you can more consciously craft resonant character arcs.

Great character arcs are built on transformation, and one of the most powerful frameworks for understanding this journey is the four stages of knowing in character arcs. These stages map a character’s growth through initiation to enlightenment to integration in a way that feels deeply satisfying to readers. Why? Because it is yet another way in which the shape of story mirrors the patterns of real life. Once you can see how plot structure challenges characters to grow (sometimes successfully, sometimes not), you can more consciously craft resonant character arcs.

Attributed to many sources, the four stages of knowing have long been one of my favorite tools for charting growth—and, often, for combatting unrealistic desires for immediate perfection. Only recently, did it occur to me these four stages map perfectly onto the four quadrants of a classic story arc. (I discuss plot structure in depth elsewhere on the site and in my books Structuring Your Novel and Next Level Plot Structure, but if you’re unfamiliar, no worries, keep reading!) If you’ve been following this site for any length of time, you know there are endless parallels between story structure/character arc and models of human development (some of which I’ve discussed here and here).

In This ArticleWhat Are the Four Stages of Knowing in Character Arcs?1st Act: Not Knowing That You Don’t KnowFirst Plot Point: Initiation1st Half of 2nd Act: Knowing That You Don’t KnowMidpoint: Enlightenment2nd Half of 2nd Act: Not Knowing That You KnowThird Plot Point: Integration3rd Act: Knowing That You KnowWhat Are the Four Stages of Knowing in Character Arcs?The four stages of knowing originate from a well-known concept in learning and personal growth, often paraphrased as:

You don’t know what you don’t know.

Then, you know what you don’t know.

Next, you don’t know what you know.

Finally, you know what you know.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

This idea has been widely used in psychology, education, and self-improvement to describe the path from ignorance to mastery. It illustrates how awareness and understanding evolve, often through experience and struggle. So it’s no surprise that, in storytelling, these stages align perfectly with the protagonist’s emotional and intellectual growth, making it a valuable tool for crafting (and double-checking) meaningful arcs. Let’s take a look at some of the parallels.

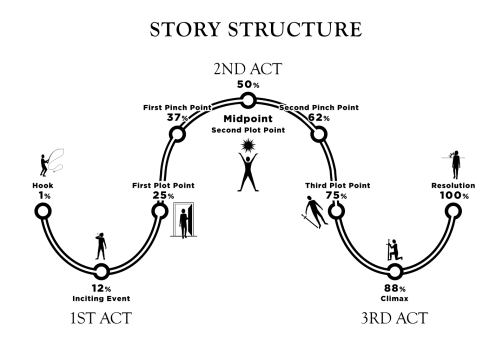

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

1st Act: Not Knowing That You Don’t KnowThe First StageThe first stage—not knowing that you don’t know—indicates unconscious ignorance. You’re ignorant of your ignorance. There is a sense of innocence and, often, a seemingly harmless hubris associated with this stage. This can feel like confidence, complacency, or simply an absence of curiosity. Without the knowledge that there’s more to learn, you have no reason to question what you think you know.

It’s impossible to be aware of the gaps in your knowledge until you first encounter a catalyst that challenges your current understanding. Only when something disrupts the seeming “wholeness” of your perspective can the journey toward deeper awareness begin.

The First Act — 1%-25%In story structure, the purpose and symbolic intent of the First Act perfectly align with this state of seemingly blissful ignorance. The First Act represents a story’s Normal World, in which the character may feel safe, familiar, content, or at least complacent. Even if the character dislikes aspects of the Normal World, it is still a lifestyle that functions reasonably well.

However, despite this basic functionality, the Normal World may be very broken indeed, as in Jane Eyre.

Jane Eyre (2011), Focus Features.

In other stories, the character may be utterly satisfied with the Normal World, as in Toy Story.

Toy Story (1995), Walt Disney Pictures.

In still others, the character may be dissatisfied with aspects of the Normal World but see no possible way of changing anything, as in Star Wars: A New Hope.

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

Whatever the case, the character is stuck, hemmed in by the status quo. This stage of “not knowing” represents the thematic Lie the Character Believes, which creates the foundation of all types of character arcs. The Lie is a limited perspective characters hold about themselves or their world. The story to come will offer them the opportunity to challenge that perspective and grow beyond it.

First Plot Point: InitiationThe stage of “not knowing they don’t know” ends with the story’s first major plot point—the First Plot Point. This moment responds to the Call to Adventure that initially challenged the characters’ worldview. A sliver of doubt is introduced into the complacency of their cohesive worldview. Perhaps all is not as it has always seemed.

Not only does this present the shocking possibility of their own ignorance, it also shines a light on areas of their lifestyles that lack functionality. If a character was previously aware of dysfunction, this moment turns the dial up until it becomes clear something must change. Even if characters adamantly wish to maintain their formerly ignorant mindsets, from here on that will become increasingly difficult. Characters will either bravely begin a slow and difficult journey into growth and expansion—or they will succumb to cowardice and resist the Truth in increasingly dysfunctional ways.

1st Half of 2nd Act: Knowing That You Don’t KnowThe Second StageIn the second stage—knowing that you don’t know—awareness begins to dawn. Now that you’ve encountered something that reveals a gap in your understanding, for the first time you begin to recognize the limitations of what you know. Depending on the gap created by this cognitive dissonance (i.e., the gap between Lie and Truth), this stage can be uncomfortable and even overwhelming. Even small challenges to one’s perspective and worldview create destabilization and uncertainty.

However, this stage also represents the beginning of real learning. Once you’ve recognized you don’t know, the door opens upon vast possibilities for growth and deeper understanding.

The First Half of the Second Act — 25%-50%

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

In story structure, the first half of the Second Act represents a stage of “reaction,” as the character struggles to respond to a new status quo without yet having all the necessary knowledge, skills, or tools. This is a stage described by Terry Pratchett’s quote:

Wisdom comes from experience. Experience is often a result of lack of wisdom.

This is a stage of fumbling around in the dark. The only advantage characters have at this point is that at least they know it’s dark—ergo, they better find a match. Previously, they didn’t even understand that much.

>>Click here to read “A Reactive Protagonist Doesn’t Have to Be a Passive Protagonist! Discover the Difference“

Even though the character’s unquestioning belief in the Lie has now been irrevocably challenged, this is a stage in which the character is still very much identified with the Lie. Because the new way of being—the Truth—is not yet clear, the character will understandably continue trying to return to the old ways. By now, however, there’s no going back. Determined ignorance or a retroactive adherence to the Lie will prove less and less effective—effectively “punishing” the character for any lack of progression.

Characters moving toward the Truth will learn to embrace the necessity and the opportunity of growth. They will (eventually) learn from their mistakes, humbly accept their ignorance, and begin gaining the knowledge, skills, tools, and experience they require in order to move forward.

This may be ideological, as in Promised Land.

Promised Land (2012), Focus Features.

Or it may be practical, as in Cast Away.

Cast Away (2000), 20th Century Fox.

Characters may willingly embrace the change, as in Harry Potter.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), Warner Bros.

Or struggle against the hard knocks, as in Toy Story.

Toy Story (1995), Walt Disney Pictures.

In stories in which the character will fail to fully progress through the four stages into positive growth, they will begin inventing stronger and more dangerous Lies in order to maintain the original Lie, as in Hamlet.

Hamlet (1996), Columbia Pictures.

Midpoint: EnlightenmentHalfway through the story—and the stages of growth—the character will encounter the Second Plot Point—or Midpoint—which represents an all-important Moment of Truth. Although this moment does not represent complete illumination, it does provide the character clarity that was so far lacking.

I like to put it like this: this is where the character recognizes and embraces the Truth but does not yet fully reject the Lie. In other words, characters do not yet understand that to step fully into this new way of being, they must first be willing to fully relinquish the old. At this point, they think they can have the best of both worlds.

What is important here is that the character is offered the opportunity to begin shifting out of ignorance into the beginnings of competence.

2nd Half of Second Act: Not Knowing That You KnowThe Third StageIn the third stage—not knowing that you know—this new knowledge is becoming second nature, but you haven’t yet fully realized or integrated your own growth. Up to now, you’ve absorbed lessons, internalized skills, and navigated challenges successfully, but you have not yet shifted your own identification with your ignorance. You may still feel uncertain, questioning whether you truly understand. This stage is often marked by imposter syndrome, doubting your competence despite clear evidence of your growth. It’s a transitional phase in which competence is building, even if you don’t fully see it yet.

Another way to look at the four stages is to see them as a journey from unconsciousness to consciousness. At this third stage, you are becoming consciously competent in this new way of being, but because these conscious skills have not fully integrated into your deepest self, they may still feel awkward, like a suit of clothes a size too big. And yet you are wearing the clothes. Although you may feel like you’re faking it, more and more you’re genuinely making it.

The Second Half of the Second Act — 50%-75%In story structure, the second half of the Second Act contrasts the “reaction” of the first half as the character moves into a more proactive and effective state of “action.” Characters are increasingly able to not just react to situations but to choose, based on their increasing stash of experience, how they want to respond—and even to initiate actions that now require responses from others. Thanks to their growing understanding of themselves and the world, they are able to make better choices—for which they will be increasingly rewarded.

However, mistakes still happen, for the primary reason that characters have not fully integrated their new Truths. You’ll remember at the Midpoint, they had yet to fully let go of their old ways of being. Now, even though they are becoming increasingly effective in their new mastery, they are still tripping over the remnants of their old ignorance. Eventually, true mastery will require them to fully embrace their new roles, represented by the Truth—which requires them to fully relinquish the old, as represented by the Lie.