K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 6

November 4, 2024

The 3 (Structurally) Most Important Characters

Today, I want to talk about the three most important characters from a structural perspective within your story.

Very often, two of the most common questions writers will ask about characters in their story is, “How many characters do I need and or can I have and which characters do I need? What characters are important to my specific story?”

What I’m going to be sharing in this post is definitely the stripped-down answer to this question. We’re going to be getting under the hood and looking at some of the mechanics of how story works. What I’m going to share is not necessarily meant to be taken literally. Rather, it’s meant to show you the foundation upon which you can build your entire cast of characters.

So when I say your story’s structure only needs three characters, don’t freak out! This doesn’t mean you can only have three characters in your story.

Character #1: The ProtagonistFrom a structural perspective, what actually creates plot and makes your story move?

There are three specific types of character who are important in running a story’s engine.

The first and most obvious is of course your protagonist. When we hear the word “protagonist,” very often what we think of is the hero, the main character, the good guy, something along those lines. We think of a specific type of person; we have a visual idea of what a protagonist is. Maybe you even see your protagonist from your story. However, although who your protagonist is in your story is very specific, sometimes this can distract from the deeper understanding of what “protagonist” is and how it functions within the story.

What Defines a Protagonist?Within story, all that defines the “protagonist” is that this is the person creating the forward momentum in the plot. They do that by wanting something. They have a desire, which will translate into the story goals that move them forward. In some stories, the desire may be that they want to move away from something else, but it could also be that they have something specifically in mind they’re moving toward.

You can think of this as the change you’re going to see within your story. Whether your characters know it or not, what they’re moving toward is the end of your story. They’re moving toward whatever state they’re going to be in—wherever the plot finds them—at the end of the story.

The protagonist is the one who creates that throughline and that momentum of moving through the story. Without a protagonist, we really don’t have a story. The protagonist is the person who is defining what this story is about. Theoretically, you could pick any number of specific characters within your story to be that protagonist. Each character would slightly change the nature of your plot because different characters will want different things, which drives and creates different plot. Regardless, the protagonist is the throughline.

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

You want to make sure the protagonist lines up with all of your major structural beats throughout the story. Usually, that means the character will be present at these beats, but more specifically it means that what’s happening at those structural beats needs to be in alignment with the protagonist’s forward momentum toward the end state of the story. If you can identify any particular structural beat within the story where that really isn’t happening—where they’re not moving toward that end state—then it’s probably a good sign that structural beat is off in some way.

From this perspective, the protagonist is the single most important character for defining your story’s structural throughline. They create the throughline (and the throughline should be created for them by the author). It’s a vehicle for them.

Character #2: The AntagonistThe second most important character (although really this character is equally as important as the protagonist because you need both of them) is the antagonist.

Similarly to the protagonist, we often hear that word and we think “bad guy.” We think of a morally negative person—a villain. However, this has nothing to do with being an antagonist. We only think this because, generally speaking, the protagonist is someone who’s morally positive and with whom we sympathize with from a moral point of view—and therefore the antagonist stands in opposition to that and is often characterized as someone who’s morally negative or at least ambivalent in some way.

What Defines the Antagonist?However, within storyform, functionally speaking, the antagonist is simply whatever or whoever is creating the obstacles between the protagonist and their momentum.

I often to use the term “antagonistic force” rather than “antagonist” because this also reminds us that the antagonist doesn’t have to be human. It doesn’t have to be a specific character within the story. Usually, the antagonist will be human and will be at the very least be represented at certain points throughout the story by proxy characters, which we’ll talk about in just a second. However, fundamentally, the antagonistic force is nothing more or less than whatever is creating the opposition through which the protagonist has to move.

Without the antagonistic force, without this opposition, the protagonist can move unhindered. They will move easily and smoothly toward whatever the end state is within the story. When they reach that end state, the story is over. The very fact that we have a lengthy tale to tell means that must be roadblocks—obstacles—difficulties. Conflict is encountered as the protagonist moves through the story. The antagonist is that necessary counterforce that creates that opposition for the protagonist to have to work through. This, in turn, is what creates the conflict and the interest in the plot.

Character #3: Relationship CharacterThe third character is a little more interesting in some ways and not as obvious. The third character is the relationship character. This character can actually take quite a few different forms within the story.

What Defines the Relationship Character?You might immediately think of love interest or something like that. This character could also be a sidekick. It could be any relationship within the story, but fundamentally what we’re talking about from perspective of story is a motivating force for the protagonist within the story.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Again, this can take many forms. This could be an Impact Character representing the story’s thematic Truth and prompting or inspiring change. For instance, a love interest very often will act within a character arc as someone who “rewards” or “punishes” based on the protagonist’s effectiveness within the plot (based on the protagonist’s relationship to the Lie and the Truth and how that allows them to either move forward or not against the antagonistic force).

However, the relationship character doesn’t have to be a love interest. This character simply represents a relationship that is important to the protagonist and is creating motivation for what they’re doing. This relationship character shines a light on the “why” of the protagonist’s motivation. The antagonistic force shines a light on all of the things the protagonist hasn’t dealt with or hasn’t figured out yet as a way to be able to move forward toward the end goal, whereas the relationship character is shows the broader context of why the protagonist is doing this—what they’re trying to build, why they’re trying to expand.

Again, this isn’t necessarily something the protagonist is conscious of. You’ll see this dynamic in stories, in which there needs to be that relational level so that there’s a catalyst—there’s a why behind the protagonist’s motives.

Using the Three Characters When Your Protagonist Is the Only Person in the StoryAgain, just as with the antagonistic force, this doesn’t necessarily have to be characterized. It’s entirely possible to create a story that’s about just one character. If you have just one character on stage, in that case these other two forces within the story will either be internalized within the protagonist as aspects of the protagonist ‘s own self, or they’ll be reflected somehow in the world around them, in the setting. We see this in stories such as the Tom Hanks movie Cast Away, in which he is all alone on an island.

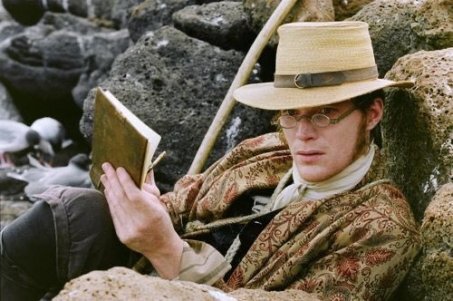

Cast Away (2000), 20th Century Fox.

The whole story basically is him lost on an island. He’s stuck in the middle of nowhere and has to survive. The antagonistic force is mostly just the weather and the elements, with him trying to figure out how to make the island work in a way that he can survive off of it. Then later on in the story, we also see, within himself, his own difficulties, as his fear and anger and frustration also work against him. He has to work through that as a way to continue toward his end goal of getting off the island and surviving.

The relationship aspect—creating a context of meaning—is represented by his relationship with the volleyball Wilson, who he personifies—but who is, of course, really just him. Wilson gives him something to care about something, onto which he can project meaning and purpose out into the world, so he doesn’t feel so alone.

That’s a great example of how all these three of these elements work within a story without necessarily having to be represented by actual characters.

Using the Three Characters When Your Story Features a Cast Larger Than ThreeObviously, most stories will feature many, many more characters than just these three. In these cases, what is happening is that every single character within your story—even if you have hundreds of them—are related to these three primal forces within the story. They are all representing, in some way, one of these forces within your story.

What If You Have Multiple Protagonists?First, I want to talk about stories with multiple protagonists. This is an important question. From the foundational perspective of story structure, there is really only one protagonist. That is what creates the structural throughline. So if you have more than one protagonist, you necessarily have more than one structural through line—as happens in stories with multiple plotlines, which I talked about in a previous video this year.

Basically, you’re telling multiple stories, which means you have multiple different story forms with each of these three story characters/forces happening in each of those plotlines until the plotlines coincide at some point later in the story.

It’s important to recognize this because you need to have a solid throughline to your structure, you may in some instances have two characters operating within the same plotline together who seem to share equal weight (romances are an obvious examples where the weight is shared equally by two different characters points of view). What’s happening in these stories is the two characters are sharing the role of protagonist within a single shared structural throughline. They’re not pulling in opposite directions. Even if they have smaller goals that are separate, they’re working toward the same structural goal or desire (e.g., being together and making the relationship work)

The same would be true in a mystery where you feature two detective characters equally. They’re working toward the same goal, so they share the weight of the protagonist’s role throughout the story. In this case, you want to make sure this shared role is represented in a unified way at each of your structural beats.

Multiple Characters Fulfilling These Three Roles (aka, Character Proxies)The most common way to use these three structural character roles in a large cast is for each character to act as a proxy for one of the three main roles—protagonist, antagonist, main relationship character.

For example, your story may feature a unified antagonistic force that is not represented by just one character. You may have a Big Bad, and then he may have doing his bidding. These minions are not separate antagonists within the story; they are proxies for the main antagonist and therefore acting in his stead. The antagonistic force is still a unified force within the story.

Again, that’s harder to do with protagonists. You have to be careful because the protagonist is your throughline and your structural anchor throughout the story.

On the other hand, you may have many different relationship characters. Obviously, you’re always going to get the tightest effect in a story when you narrow these things down as much as possible, so you don’t have a lot of extraneous characters. But for instance, you may have a protagonist whose context and reason and why for what they’re doing—therefore representing that relationship aspect—could be a whole town. It could be you are perhaps interested in showing a broader setting, where there isn’t a specific relationship character within the story.

What comes to my mind right now is The Andy Griffith Show, in which protagonist Andy is involved with this entire town. He’s in a relationship with many different people throughout Mayberry. There are primary relationships, such as his son Opie, his deputy and best friend Barney, and his aunt Bea, but all of the characters within the entire show relate to him and interact with him as either an antagonistic force or a relationship character.

The Andy Griffith Show (1960-68), CBS.

***

In very simplified terms, you could think of the relationship character as the one the protagonist is doing things for, while the antagonist force is the one they’re doing it against.

I hope that’s helpful. However, sometimes oversimplifying things can be the opposite of helpful, so if this doesn’t resonate or if it feels confusing, then just forget about it. The essence of what I’m trying to communicate here is that there are three engines kind of within your story. If you’re ever confused about whether or not a character is useful or is extraneous, or you have too many characters or not enough characters, this is a good place to come back to so you can examine your cast. You can go through each one and say, “Okay, this character is a protagonist. These characters are representing the antagonistic force. These characters are representing the relationship aspect within the story and reflecting back to the protagonist the required growth qualities.”

You can ask:

Would my story be stronger if I got rid of some of these characters and just focused in on one specific character to represent each of these categories?Would it create a stronger dynamic for my protagonist, or do I need more characters?How do I do that in a cohesive way that is still structurally pertinent?Thinking about putting each character in the little box where they belong can be helpful in organizing them and seeing where maybe some things are misplaced and not fulfilling their optimum job and or where they’re completely extraneous.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Who are the most important characters in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast , Amazon Music , or Spotify ).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The 3 (Structurally) Most Important Characters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 28, 2024

What Would You Like Me to Write About?

Hey, everybody!

Hey, everybody!

I can’t believe we’re already into the final stretch of 2024. What a wild year this has been for me! I moved to my dream house this summer, something I’ve been working on manifesting for years now. The early part of the year was a bullet train of intensity and determination as I did a year’s worth of work (two books, a course, and fifty+ posts/podcasts/videos) in four months.

And then… moving!

It has taken my nervous system all summer to come back to a place of centeredness from which I can truly look around me through eyes wide with gratitude.

Every day now I am finding new depth in the simple meditation: “Thank you for everything. I have no complaints whatsoever.”

I’ve had so much fun with the content I’ve gotten to share so far this year, and I’m already starting to think about what I want to share here on the blog next year. I’d love to hear what you would like me to write about!

So…

What would you like me to write about?

Is there a writing subject that’s really got your interest right now?

How about a gnawing question you just can’t figure out?

In short, as I start gearing up for a new round of posts and podcast episodes, I’d like to make sure I’m serving your needs as best I can.

You can also let me know if there’s a book, webinar, or other resource you’d like me to create on a particular topic. What would best serve you in your writing journey?

I’d also love to know what format of content you like best: written posts, audio podcasts, videos? What length of material is most accessible for you?

Leave me a comment and tell me what post you’d most like me to write for you. (If you phrase your request as a question, I may be able to quote you if I end up using it as inspiration, unless of course you specify that you’d rather I not do so.)

As always, thank you all so much for your engagement here with me and your passion for telling stories to a world that needs them!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What writing topic or question would you like me to talk about in future posts? Tell me in the comments!The post What Would You Like Me to Write About? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 21, 2024

Learn About the Different Types of POV (+Head-Hopping)

Today we’re going to be talking about a topic all writers have questions about at one point or another—and that is POV.

Today we’re going to be talking about a topic all writers have questions about at one point or another—and that is POV.

POV stands for “point of view.” It is the perspective through which you tell your story’s narrative. Specifically, we’re going to talk about which “person” you might want to use when choosing your POV. By that, what’s meant is either you’re going to choose to tell the story through first-person, second-person, third-person, or omniscient.

Characters, Emotion, & Viewpoint by Nancy Kress (affiliate link)

There are many other questions that come up around POV, such as which characters’ POVs you should choose to filter story through, but that’s a whole other topic. I recommend the books Characters, Emotions, and Viewpoints by Nancy Kress and Characters and Viewpoint by Orson Scott Card.

Today, we will cover the differences and the advantages and the disadvantages of these different approaches to POV.

Characters & Viewpoint by Orson Scott Card (affiliate link)

Types of POVTo get us started, let’s go over each one quickly, and then we will talk about some of the reasons you might or might not choose them, depending on the type of story you’re writing. At the end, we’re also going to talk just a little bit about head hopping.

Second-Person POVI want to talk about second-person POVs first, since they’re the easiest to cover. Second-person is when you would tell a story using the pronoun “you,” as if telling the story is from the perspective of the reader.

For example, “you are opening the door, you are doing this thing, you are fighting in the battle,” whatever the case may be.

Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney (affiliate link)`

Obviously, this is quite unusual. You see this very rarely within books, and it’s almost always gimmicky. There are only a couple novels relatively well-known for having used it. One is Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney. Another is If on a Winter’s Night… by Italo Calvino.

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller by Italo Calvino (affiliate link)

Second-person is an interesting approach. It’s kind of like the Choose Your Own Adventure stories you may have read as a kid. It’s highly stylistic and therefore can be quite gimmicky. As a result, it’s used very rarely and isn’t recommended for most fiction, particularly mainstream fiction. However, it’s good to be aware of it because it is out there.

That leaves the two main and most popular points of view you can use. These are the two that are seen and used most often.

First-Person POVThe first is first-person, in which you use the pronoun “I,” telling the story from the protagonist’s point of view.

For example, “I went through the door, I bought groceries.”

Third-Person POVThis is contrast to third-person, in which you’re using pronouns like “he” or “she” or “they” to tell what’s going on/

For example, “he knocked on the door, and she opened the door.”

For all intents and purposes, first- and third-person are actually quite similar to execute. The advantages or disadvantages that you might gain from the way you write the story in a deep third-person POV is very similar to those of a first-person POV. The only major difference is the pronouns. In these POVs, what you’re trying to achieve is the effect that the entire story is more or less being told through the thoughts and the voice of the narrating character.

Again, this can be very stylistic in the sense that the voice you’re trying to create on the page is the character’s voice. It’s the same voice the character would use when speaking dialogue, only you’re in his or her head. You can still share what they’re actually thinking through direct thoughts which are told in present tense and usually italicized or something like that, but in these deep POVs everything that’s coming across the page is from the character’s point of view.

Tips & Tricks for Writing in First-Person POVFirst-person is always deep. It’s always right there inside the character’s head. Every word is intended to be seen as the character’s point of view. Because of this, first-person is the most intimate of all of the POVs. It puts the readers right there in the character’s head. Sometimes that’s exactly what you want. That level of intimacy between readers and characters rarely a bad thing. You want readers to identify with the characters and understand what they’re thinking and feeling.

This particular approach is very popular right now in romance, alternating first-person POVs between the two love interests. Just because you’re writing in first-person doesn’t mean the whole story has to be told from the same POV. You just have to make it very clear when you switch—which is usually done chapter by chapter, with a heading on at the beginning of the chapter indicating which character’s POV you’re in.

The more advanced side of the technique is that, ideally, you want readers to be able to tell which POV they’re in just because the characters’ voices are distinct. That can get tricky because ultimately it’s all your voice. The more personalized each of the voices in a multi first-person narrative, then the more characterized those people become. They pop off the page as dimensional and separate people, rather than just kind of facets of same person with the same voice and the same personality.

Downsides of First-Person POVOne of the downsides of first-person is basically too much intimacy. There are stories in which maybe you don’t want readers to be that close to a character. This could be for a number of reasons. It could be because the character is so unsavory, readers won’t enjoy being in this person’s head. That’s not always true because obviously there are stories about horrible people, in which it can be fascinating to explore a dark psyche.

1. Can Make Unlikable Characters Even More UnpalatableI actually think the most complicated characters for deep or for first-person POVs are characters that in between: they’re not entirely lovable, but they’re also not fascinatingly evil. Their foibles are more along the lines of pride or self-obsession or insecurity. If that’s not handled just right, that can become very grating within a first-person POV, because all the bad things the character may be thinking either about themselves or others is just constantly there in the reader’s face. Sometimes that’s fine. Sometimes that’s part of what the character is working through in the story. But be aware that sometimes first-person can actually have the unintended effect of distancing readers from the character, simply because they don’t like the character that much. In these instances, the character might actually be more likable if there was a little more distance in the narrative.

2. Can Give Away Plot Twists Too EarlyAnother limitation of first-person is that sometimes you don’t want readers to know what’s happening in the character’s head. For example, maybe the character knows something and you don’t want the reader to know it. There are definitely ways to get around this when you’re writing a deep POV.

Generally speaking, you do want readers to know what your character knows, so they can advance through the story with the the characters and identify with them as the story progresses. However, there are definitely stories where you don’t want readers to know. And in those instances, first-person might not be your best choice.

3. Can Create a Flat Narrative ToneIf you don’t have a really good voice for the character-–if it’s flat or monotone—then first person is probably not your best choice. This is not always true. But generally speaking, this can flatline your entire narrative in a way that wouldn’t necessarily happen in a different kind of POV. First-person can sometimes lend itself to staccato prose, which will just be exacerbated by flatness in the narrative voice.

If you’re going to write in first-person, find a character or create a voice for a character that’s really interesting, that is lively and has personality and isn’t a monotone recording of what they see and what they do and how their thoughts are reacting.

Tips & Tricks for Writing in Third-Person POVThird-person can be quite similar to first-person if you’re doing a deep POV. One of the advantages of third-person is that it’s quite flexible. You can do a lot with third-person. Again, third-person is where you are telling a story about someone else. You’re using third-person pronouns like “he” or “she.” That is how you’re addressing the POV character.

If you’re going deep with a third-person POV, then you’re essentially just as deep in their head as with first-person, reporting what they’re experiencing and what they’re thinking and feeling in pretty much the same way. Again, you can do direct thoughts that are italicized, but you don’t have to because the whole narrative is still in their voice. It’s coming through the character. In contrast to first-person, you’ve just chosen to take that one little step back and use third-person pronouns instead of first-person pronouns.

There’s a whole gamut of depth and shallowness you can play with within third-person POV. You may choose to go really deep and be completely inside a character’s head, or you may choose to draw back to varying degrees and not be so deep in their head. In the latter case, you’d still be using the third-person pronouns and reporting what they’re doing, but you’re not so deep in their head and you can still tell what they’re thinking. You share that with readers, but it becomes more that you are reporting their thoughts rather than that you’re recording them through their voice.

In most stories, you’ll zoom in a little bit here and zoom out a little bit there. You want consistency, but you can think of it in a similar way to what you would see in a movie, in which sometimes there’s close-ups and then sometimes it’s a wide shot. What’s important is that the voice remains consistent, so readers always have a sense of who’s talking to them, that it feels like it fits with the narrative voice that’s been used up until this point.

Multiple POVsAgain, with third-person, you can totally do multiple POVS. You can go deep within the perspective of any number of characters and show what they’re seeing in different scenes.

One thing to think about with POVs of any type, is that if you’re going to do multiple POVS, really consider why you’re putting them all in. POVs create your narrative; they frame every piece of your narrative. It’s true that putting in random POVs or a POV from a character who’s going to have a POV scene just once (just so you can show something that’s happening that the protagonist isn’t on stage) can be effective. I can definitely help you show information that the reader wouldn’t be able to access through the protagonist’s point of view. But you have to be careful with this because it can easily scatter your narrative.

Generally speaking, the fewer POvs you can get away with, the better. The use of a single POV is really, in my opinion, very underestimated. These days, we tend to want huge sprawling POV stories, but a single POV story, when done well can be unparalleled for the effect it creates.

Again, multiple POVs are great in romance, in which you will generally have two. In other types of story, it’s fine to have dozens. What’s important is that you’re aware of how these POvs are interacting with the story’s overall structure. We talked a few months ago in the video about multiple timelines and plot lines about how it can be really effective to bring minor characters in at the structural moments as kind of a subplot, sewing them in at regular intervals so they don’t just show up once randomly. You want each POV to feels like it was on purpose and that there’s a thematic reason and a structural reason for why these POVs are in here rather than them just being convenient for the author.

That’s always something to think about when you’re choosing how many or which characters are going to get POVs within a story.

Tips & Tricks for Writing in Omniscient POV

H.M.S. Surprise by Patrick O’Brian (affiliate link)

With third-person, you can zoom all the way out, and when you get all the way out, that is generally what’s called omniscient POV. Omniscient POV is where you’re not really in any one specific character’s head. As the name suggests, the story is being told from an all-knowing point of view—that point of view generally being the author, although it can on occasion be a specific narrator within the story, who knows everything that’s happening and they’re just kind of reporting it back.

The advantage of omniscient POV is that you can go anywhere and tell anything. It isn’t as confined. It doesn’t have to play by as many rules, in a certain sense, as the more limited povs of first-person and deep third. The disadvantage is that it isn’t as intimate. By nature, it’s more distant. Even though you can dip into a character’s head here or report on what they may be thinking there, you aren’t following a character through the entire story and experiencing it from the inside out.

Deep POVs—first-person and deep third—offer an inside-out experience of the story. Omniscient is an outside-in. You’re looking at the story from an outside perspective and sometimes delving into characters’ heads and thoughts. It’s more like you’re reporting what they’re thinking rather than trying to create an experience where readers are equally experiencing it.

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke (affiliate link)

Omniscient was very popular back in the day. Victorian novels, etc., were almost all told from an omniscient point of view. Omniscient has grown more out of favor to where mainstream fiction is more in a deep POV these days. However, it’s still used and it can be very effective at creating more of a stylistic tone for a story. Particularly if you are trying to give it a historical flavor. Omniscient can be very effective at doing that. In the Aubrey Maturin series, Patrick O’Brian this masterfully. Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell comes to mind also as a story that does this really well.

Downsides of Omniscient POVThe major downfall is that when omniscient is done poorly, it lacks focus. It feels like an author who doesn’t have control of their narrative, like they’re using omniscient because they just want to tell everything—versus it being a cohesive choice.

Good omniscient story is still limited. It’s still choosing to focus on very specific things for very specific reasons. It’s not just jumping from this character to that character to that character because it’s convenient to tell a bigger story.

I feel like the random omniscient narratives that don’t really work are doing that because they’re more plot-based. They’re just using the characters and jumping from character to character to character as a way to just tell what’s happening. They focus on what’s “out there” and what the characters are seeing rather than the characters themselves and what they’re doing. In contrast, a more controlled and contained omniscient narrative is one that is still focused on the characters. It has a good grasp of how to integrate character, plot, and theme and is using its POV choices to accomplish that.

What to Know About Head-HoppingPart and parcel of omniscient narratives that don’t work and that are just jumping around all over the place is a POV mistake or pitfall that you will often hear called head-hopping. Head-hopping can happen in any of the different POV types that we’ve talked about. Basically, head-hopping is when you’re breaking the rules you have set for your story and your POV use within your story. Instead, you’re jumping out of the established POV into a different character’s head.

Head-Hopping in Deep POVsThis is most obvious if you are writing a deep third-person or first-person. Head-hopping occurs when you’re writing a deep POV, in which you’re telling a scene from within one character’s head, and then all of a sudden there’s a thought or an observation from another character. Maybe this other character is watching your protagonist, or maybe you’re including this other character’s thoughts because you want an outside perspective on your protagonist (e.g., you want somebody to describe how they look or offer a perspective on what they’re doing or why they’re doing it). And so you jump real quick over into this other person’s head and give their thoughts and their perspective, and then you jump back to the original character. That’s head hopping.

This can be very jarring and confusing for readers. At the very least, it does not contribute to a cohesive narrative. The simplest way to avoid head-hopping is to recognize that you can use other characters’ POVs, but you need to do so in a structured way, such as by ending one character’s POV with a scene or a chapter break and then switch to the next character’s. Generally, because this is indicated by scene breaks, each characters’ POV needs to constitute a scene or at least a big chunk of the scene to be worth the break. Jumping to another character’s POV for a paragraph or something generally isn’t a good idea. It can be kind of quirky and funny if that’s the kind of story that you’re writing, but otherwise it’s basically head hopping just sort of disguised.

If you want to include multiple POVs, the best approach is usually to create a scene from one character’s POV, then switch to the next character’s POV and remain consistent with each character within their section.

Head-Hopping in Omniscient POVThe topic of head-hopping becomes a little more complicated when you’re writing an omniscient POV that by nature is able to look into any character’s head. The rules do blur a little here. It’s a little harder to be able to say, “Well, that’s omniscient and that’s head hopping.” The basic bottom line is always to ask yourself:

Does it work?Does it feel jarring?Does it feel like you’re just jumping from character to character to character?Does it feel seamless?Studying how authors have done this in omniscient narratives and made it work can be very helpful in recognizing the difference between head-hopping and omniscient.

Although not a hard and fast rule, a general way to test whether you are head-hopping versus using an omniscient POV is to ask yourself:

Are you going deep into the characters’ heads when you shift?Are you explicitly saying “this character is thinking this” and then “this character is thinking this“?Are you using direct thoughts (e.g., maybe the one character is thinking, I really want ice cream for breakfast, and then you go over Sally’s thinking, I really want eggs for breakfast.)?Are you trying to switch into a deep POV for multiple characters?

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak (affiliate link)

Again, you will see exceptions to this, but often that’s going to be a pretty jarring approach to readers versus maintaining a consistent POV. Think about who is telling the story. What is the specific narrative perspective? This creates a unified cohesive perspective, whether that perspective is a specific character within the story or an actual narrator, such as in Marcus Zusak’s The Book Thief, in which Death narrates the entire story. In this case, Zusak is ultimately the narrator, since he’s the one writing the book, but he uses Death as an omniscient character within the story who can examine everything that’s happening and give a big picture view of what’s going on.

POV is arguably one of the trickiest techniques within narrative fiction. There’s a lot to get your head around and learn. The best way to learn is studying how it’s done. It’s one thing to read it casually, because if you’re not paying attention, a good POV is very seamless. As a reader, you’re not normally thinking about it. You’re not thinking, Oh, that’s in first-person. You want the effect to be so seamless that readers don’t have to think about it.

However, as you’re trying to figure out how to write it, you need to go back and study. Ask, “What is the writer doing to create this cohesion and this seamless effect, whether they’re writing first-person or third- or omniscient.” Always pay attention to how you respond and react to these various POVs, so you can understand which effect you want to convey within your own story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Which different types of POV have you used in your stories? Which did you enjoy most? Which did you find most challenging? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Learn About the Different Types of POV (+Head-Hopping) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 14, 2024

The Resolution (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 12 of 12)

The Resolution is a bittersweet moment. You’ve reached the end of the story. You’ve climbed the mountain, and now you can plant your flag of completion at its peak! But as the finale of all your work, this is also the finale of all the fun you’ve experienced in your wonderful world of made-up people and places. The Resolution is where you must now say goodbye to your characters and give readers a chance to also say goodbye.

The Resolution is a bittersweet moment. You’ve reached the end of the story. You’ve climbed the mountain, and now you can plant your flag of completion at its peak! But as the finale of all your work, this is also the finale of all the fun you’ve experienced in your wonderful world of made-up people and places. The Resolution is where you must now say goodbye to your characters and give readers a chance to also say goodbye.

Your story and its conflict officially ended with your Climax. Most stories require a subsequent scene or two to tie off loose ends and, just as importantly, to guide readers to a final emotion. Like those great ensemble scenes at the ends of the original Star Wars movies, this is the last glimpse readers will have of your story world and its characters. Make it one they’ll remember!

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

What Is the Resolution?

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

Conceivably, you could close your story at the Climactic Moment since your story and its conflict officially ended there. But if most stories were to end immediately after the Climax, the result would be some very disgruntled readers.

After all the emotional stress of the Climax, readers want a moment to relax. They want to see the characters rising, dusting off their pants, and moving on with life. They want to glimpse how the ordeals of the previous three acts have changed your characters; they want a preview of the new life your characters will live in the aftermath of the conflict. And if you’ve done your job right, they’ll want this extra scene just to spend a little more time with characters they’ve grown to love.

As its name suggests, the Resolution is where everything is resolved. In the Climax, the protagonist overcame the villain and won the love interest; in the Resolution, readers now get to witness how these actions will make a difference for the characters moving forward.

For Example:

The film Serenity ends by showing Captain Mal Reynolds and his surviving crew heading back to space, now free of the Alliance’s dogged pursuit, while Mal and Inara and Simon and Kaylee take a step into their future relationships together.

Serenity (2005), Universal Pictures.

The Resolution is not just the ending of this story but also the beginning of the story the characters will live in after readers close the back cover. The Resolution performs its two most significant duties in capping the current story while also promising the characters’ lives will continue. This is true of standalone books and even truer of individual parts in an ongoing series.

For Example:

Ship of Magic, the first book in Robin Hobb’s The Liveship Traders trilogy, is open-ended: its Resolution promises protagonist Althea Vestritt will pursue and rescue her liveship Vivacia, which has been captured by pirates.The standalone book Empire of the Sun by J.G. Ballard ends with a few short scenes explaining the protagonist Jamie’s adjustment to his post-war life outside of the Japanese POW camp and hinting at his future growing up in England.

Empire of the Sun (1987), Warner Bros.

Where Does the Resolution Belong? Creating the perfect ending boils down to one essential objective: leave readers satisfied. The Resolution begins directly after the Climax and continues until the last page. Resolutions can vary in length, but shorter is generally better. Your plot is over. You don’t want to test readers’ patience by wasting their time.

Creating the perfect ending boils down to one essential objective: leave readers satisfied. The Resolution begins directly after the Climax and continues until the last page. Resolutions can vary in length, but shorter is generally better. Your plot is over. You don’t want to test readers’ patience by wasting their time.

The length of your Resolution will depend on a couple of factors, the most important being the number of remaining loose ends. Using the scenes leading up to your Climax to resolve as many subplots as possible will free up your Resolution to take care of essentials.

Another factor to consider is the tone with which you want to leave readers. This is your last chance to influence their perception of your story. How do you want to end things? Should the final emotion be happy? Sad? Thoughtful? Funny?

One of my favorite Resolutions is the final scene in Disney’s The Kid. Its closing scene promises reconciliation between the main character and the woman he loves, indicating the future progression of his transformed life. It strikes the perfect note of happiness, hope, and affirmation. Strive to leave your readers with a similarly powerful and memorable scene.

Disney’s The Kid (2000), Walt Disney Pictures.

Examples of the Resolution From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: After Darcy and Elizabeth proclaim their love for one another in the Climax, Austen ties up her loose ends in a few tidy scenes that include the Bennet family’s reaction to the engagement. From her perch as an omniscient and distant narrator, Austen caps her story with a final witty scene in which she covers the book’s two culminating weddings and comments on Mr. and Mrs. Darcy’s and Mr. and Mrs. Bingley’s future lives together. Her Resolution is a beautiful example of hitting a tone that sums up the story and leaves readers feeling exactly how she wants them to.

Pride & Prejudice (1995), BBC1.

It’s a Wonderful Life: The closing scene of this classic has viewers crying all over the place every Christmas. The movie wastes no time moving on from the Climax, in which George’s friends bring him above and beyond the $8,000 he needs to replace what was stolen by Mr. Potter. The Resolution immediately fills in the remaining plot holes by bringing the entire cast (sans the antagonist) back for one last round of “Auld Lang Syne” and hinting that the angel Clarence has finally earned his wings. This tour de force of an emotionally resonant closing scene leaves readers wanting more while fulfilling their every desire for the characters.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

Ender’s Game: Card takes his time with a lengthy Resolution. In it, we’re given what essentially amounts to both an epilogue explaining some of Ender’s life after his defeat of the aliens (he leaves Earth to try to make peace with both his superstar status and his guilt over his xenocide of the aliens) and an introduction to the sequels that will follow (in which Ender takes charge of finding a new home for the sole remaining alien cocoon).

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: After tying off all existing loose ends from the plot’s overarching conflict, the story closes with a surprising scene in which Jack realizes the Acheron’s captain masqueraded as the ship’s surgeon in order to attempt a takeover of the ship once it sailed away from the Surprise. The final scene—in which Jack matter-of-factly orders his ship to once again pursue the Acheron, while he and Stephen play a rousing duet—gives us both a sense of continuation and a perfect summation of the movie’s tone.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the Resolution The Resolution takes place directly after the Climax and is the book’s last scene(s).The Resolution ties off all prominent loose ends and answers all salient questions. However, it must also avoid being too pat.The Resolution offers a sense of the characters’ continuing lives. Even a standalone book should hint at this forward momentum.The Resolution gives readers concrete examples of how the characters’ journey has changed them. If someone transforms from a selfish jerk, the Resolution needs to dramatize this change of heart.Finally, the Resolution strikes an emotional note that pays tribute to the book’s tone (e.g., funny, romantic, melancholy, etc.).

The Resolution takes place directly after the Climax and is the book’s last scene(s).The Resolution ties off all prominent loose ends and answers all salient questions. However, it must also avoid being too pat.The Resolution offers a sense of the characters’ continuing lives. Even a standalone book should hint at this forward momentum.The Resolution gives readers concrete examples of how the characters’ journey has changed them. If someone transforms from a selfish jerk, the Resolution needs to dramatize this change of heart.Finally, the Resolution strikes an emotional note that pays tribute to the book’s tone (e.g., funny, romantic, melancholy, etc.).As you write your closing lines, consider all the words that have come before. Dig deep to cap your story with an intellectual and emotional Resolution. Congratulations, you now know how to structure a story!

***

And now we’ve come to the end of our series! I hope you’ve enjoyed these last few months’ journey through the exciting landscape of story structure. You now have the tools to identify and understand the important plot points in any story and to consciously apply them to your own books. With the knowledge of story structure in your writing toolbox, you can deliberately craft and tweak your stories to make certain you’re giving readers the rise and fall and ebb and flow that will suck them into your story world and convince them of the credibility of your characters’ strong arcs. Happy writing!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How many scenes does your story’s Resolution contain? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Part 6: The First Half of the Second Act

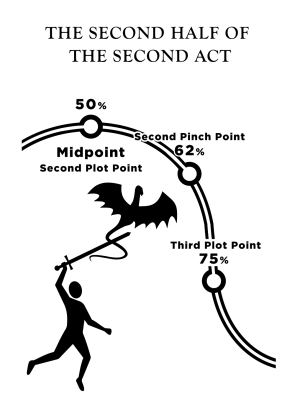

Part 8: The Second Half of the Second Act

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Resolution (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 12 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 7, 2024

The Climax (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 11 of 12)

The Climax is the pièce de résistance of your gourmet meal of a novel. When you wheel out the Climax and lift the serving dish’s gleaming silver lid, this is the bit that gets all the oohs and aahs.

The Climax is the pièce de résistance of your gourmet meal of a novel. When you wheel out the Climax and lift the serving dish’s gleaming silver lid, this is the bit that gets all the oohs and aahs.

The Climax should have readers on the edge of their seats. They should be breathless, tense, and curious to bursting. They should have a general idea of what’s coming but also suffer the exquisite torture of a little doubt. What’s gonna happen? Will the characters survive? Will they save the world/their families/the battle/their lives in time?

What Is the Climax?Starting with the Third Plot Point, the action will rise to a fever pitch. The characters will have been backed to the wall with limited choices about how to respond. The Climax begins when the two speeding trains driven by protagonist and antagonistic force begin hurtling toward a final collision.

The function of the Climax is to conclusively end the plot conflict by deciding whether or not the protagonist will attain the plot goal. Although some genres (such as romance) predetermine the protagonist’s success, it is not structurally important whether or not the character gains the plot goal.

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

In some stories, the protagonist may decide the true victory is found in not seizing the plot goal even once it is within reach. What is important is that the protagonist reaches a moment in the story in which it no longer makes sense to pursue the plot goal. Either because the protagonist reaches the plot goal or because the antagonistic force creates a permanent block to the plot goal or because the protagonist decides to relinquish it—whatever the case, this is where the protagonist’s pursuit of the goal ends.

In some stories, the protagonist may decide the true victory is found in not seizing the plot goal even once it is within reach. What is important is that the protagonist reaches a moment in the story in which it no longer makes sense to pursue the plot goal. Either because the protagonist reaches the plot goal or because the antagonistic force creates a permanent block to the plot goal or because the protagonist decides to relinquish it—whatever the case, this is where the protagonist’s pursuit of the goal ends.

For Example:

In Lois McMaster Bujold’s The Curse of Chalion, the Climax is reached when the protagonist Cazaril and the antagonist Martou dy Jironal clash in the duel that kills dy Jironal, which allows Cazaril to achieve his goal of breaking the curse upon the royal family.In the classic film The Thomas Crown Affair, insurance investigator Vicki Anderson fails to achieve her plot goal when the trap she set for her master thief lover fails. She waits to arrest him as his Rolls Royce arrives to pick up the stolen bank money, only to discover he left the country and sent a decoy in his place.In Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess, the protagonist Sara’s central plot problem is solved when she returns the neighbor Mr. Carrisford’s monkey and reveals herself to be the long searched for daughter of Carrisford’s dead business partner. This allows her to escape her servitude to the evil Miss Minchin and return to a loving family.

A Little Princess (1995), Warner Bros.

In some stories, the Climax will involve a drawn-out physical battle. In others, the Climax might be a simple admission that changes everything for the protagonist. Almost always, it is a moment of revelation for the main character. Depending on the story’s needs, the characters will reach a life-changing epiphany directly before, during, or after the Climax. They will then act definitively upon that revelation, capping the change in their character arcs and ending the primary conflict physically, spiritually, or both.

The Climactic Moment The Climax is a sequence of scenes comprising the final eighth of the story. This sequence is designed to funnel the characters into the pivotal Climactic Moment. The Climactic Moment is the climax of the Climax. It is the exact moment when the conflict ends.

The Climax is a sequence of scenes comprising the final eighth of the story. This sequence is designed to funnel the characters into the pivotal Climactic Moment. The Climactic Moment is the climax of the Climax. It is the exact moment when the conflict ends.

The Climactic Moment is one of your story’s most structurally essential beats. This is so not just because the plot cannot end without it but because the Climactic Moment reveals what your story is really about and whether the structure you’ve designed has worked.

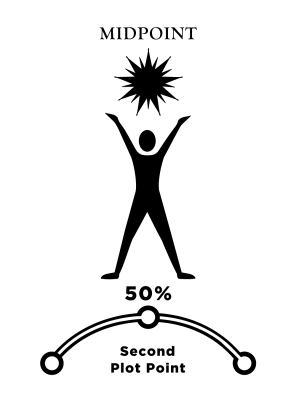

Whatever happens in the Climactic Moment is what your story has been building toward. Every beat in the story’s structure (starting with the Hook and moving through the Inciting Event, the First Plot Point, the Pinch Points, the Midpoint, and the Third Plot Point) has been leading up to the Climactic Moment. If you were to write an outline that featured just these main structural beats, you should see a consistent pattern. Everything at these beats should thematically align with what happens at the Climactic Moment. If they do, you know you’ve created a story structure that works. If they do not, you now have a map to guide you to which structural pieces need to be revised to create cohesion and resonance within your plot.

The Climactic Moment tells you three things:

1. What your main conflict is really about.

2. What your protagonist’s main plot goal really is.

3. Who is the true antagonistic force.

These three elements should be presented consistently throughout the story. By the same token, if you have consistently presented a conflict, goal, and antagonist at every other plot beat, these elements must be featured in your story’s Climax.

The Climactic Moment signals the end of the story. Although you will likely tie off loose ends in a final Resolution scene (to be discussed next week), the Climactic Moment is the true ending. There is no plot left after this.

Where Does the Climax Belong?The Climax occurs in the Third Act, beginning around the 88% mark. More often than not, the Climactic Moment at the end of the Climax will be the penultimate scene, just before the Resolution. Because the Climax says everything to be said except for a little emotional mopping up, there’s no need for the story to continue long after its completion.

Some stories will include a faux climax, in which the characters think they’ve ended the conflict, only to realize they haven’t addressed the true obstacle standing between them and the goal. For example, in Toy Story, Woody and Buzz defeat the evil neighbor kid Sid in a faux climax, only to realize they may still miss the moving van that will take them to Andy’s new home. Faux climaxes do nothing to change the requirements of the actual Climax.

Toy Story (1995), Walt Disney Pictures.

Examples of the Climax From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: As in most romantic stories, the Climactic Moment of this classic novel occurs when the two leads come together, admit their love for each other, and commit to a long-term relationship. After Darcy’s gallantry in patching up Lydia’s elopement with Wickham and his efforts to reunite Bingley and Jane, he and Elizabeth are at last alone on a walk, during which they put straight their former misconceptions, repent of their misconduct to one another, and get engaged.

Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.

It’s a Wonderful Life: After receiving the gift of seeing the world without himself in it, George races back to the bridge and fervently prays, “I want to live again!” This moment is both his personal revelation and a bit of a faux climax. It properly caps the unborn sequence (which follows a mini plot and structure of its own) and leads into the true Climax in which the town rallies to help George make up the lost $8,000 before he can be arrested.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

Ender’s Game: After Ender and his team graduate from Battle School, they enter a new series of what they all believe to be tactical games training them to face the aliens. Pushed to the limit of his physical and emotional endurance, Ender triggers the Climactic Moment when he breaks what he perceives as the rules. He looses his frustrated aggression on the game and annihilates the enemy. Then comes the revelation that he wasn’t playing a game at all, but rather commanding faraway troops fighting the aliens in real time.

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: The climactic battle between the HMS Surprise and the Acheron takes up a lengthy section of the Third Act, rising to a single red-hot point. The Climactic Moment occurs when Captain Jack Aubrey enters the Acheron’s surgery to find the French captain, his long-pursued enemy, dead. He takes the captain’s sword from the surgeon and organizes the mopping up.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the ClimaxThe Climax occurs near the end of the story, beginning around the 88% mark and ending only a scene or two away from the last page.The Climax comprises a sequence of scenes leading to the Climactic Moment.The Climax decisively ends the primary conflict with the antagonistic force (whether the protagonist wins or loses).The Climax is the fulcrum around which the character arc turns. Whatever happens here is the direct result of the protagonist’s personal revelation.Depending on how many layers of conflict you’ve created, your story may feature a faux climax leading up to the Climax proper.Cut loose with your Climax. Have fun with it and think outside the box. Make sure you’ve checked off all the essential elements of structure so you can give readers an experience that will cement your story in their memories.

Stay tuned: Next week, we will talk about the Resolution.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How does your story’s Climax fulfill all your promises to your readers? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Part 6: The First Half of the Second Act

Part 8: The Second Half of the Second Act

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Climax (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 11 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 30, 2024

The Third Plot Point (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 10 of 12)

The Third Act begins with another life-changing plot point. More than any preceding it, this plot point sets the protagonist’s feet on the path toward the final conflict in the Climax. From here, your clattering dominoes form a straight line as your protagonist hurtles toward an inevitable confrontation with the antagonistic force. Because the entire Third Act is full of big and important scenes, this opening plot point, by comparison, can sometimes seem less defined than the First Plot Point and the Midpoint. However, its thrust must be just as adamant.

The Third Act begins with another life-changing plot point. More than any preceding it, this plot point sets the protagonist’s feet on the path toward the final conflict in the Climax. From here, your clattering dominoes form a straight line as your protagonist hurtles toward an inevitable confrontation with the antagonistic force. Because the entire Third Act is full of big and important scenes, this opening plot point, by comparison, can sometimes seem less defined than the First Plot Point and the Midpoint. However, its thrust must be just as adamant.

The Third Plot Point represents a Low Moment for your characters. The thing they want most in the world will be almost within grasp—only to be dashed away—causing them to question their investment in the conflict. The subsequent Climax will be the period in which the characters rise from the ashes, ready to do battle from a place of inner wholeness. The Third Plot Point is the place from which they must rise.

What Is the Third Plot Point?

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

As the portal between the Second Act‘s end and the Third Act’s beginning, the Third Plot Point represents one of the story’s most significant shifts. Back at the 25% mark, the transition between the First and Second Acts signaled that the characters had left behind their Normal World and, with it, whoever they used to be. Now, this bookending transition into the Third Act signals they have entered the final proving ground. Everything they have learned, experienced, gained, and lost in the Second Act will be put to the final test.

Symbolically within the transformational arc of a story, the Third Plot Point represents death—with the possibility of rebirth, if the character manages to complete a Positive Change Arc. Often, this beat is referred to as the Dark Night of the Soul, indicating an intense period of internal suffering and questioning as the characters grapple with external losses while struggling to unify all the pieces of their newly evolved selves.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

If they can successfully manage this, they will be able to embrace the story’s thematic Truth and rise into a new version of themselves, one with the capability to achieve moral and perhaps practical victory in the Climax. If they fail this intense test and cannot fully rebirth into a more coherent version of themselves, they will struggle to find a complete victory in the Climax. This weakness may cause them to lose the plot goal altogether. Even if they manage to seize the plot goal (perhaps through dubious means), they will experience a fatal moral failure that poisons their achievements.

The intensity of the character’s suffering at the Third Plot Point will depend on the nature of your story. Generally, whatever takes place here should be “the worst thing that has ever happened” within the scope of the story.

For Example:

In Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, the vigilante Ra’s Al Ghul announces his intentions to destroy Gotham, then burns Bruce Wayne’s mansion and leaves him for dead.In Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Jane discovers, on her wedding day, that Mr. Rochester is already married to a madwoman. This prompts her to flee her life at Thornfield, ending her relationship with the man she loves.In Charles Portis’s True Grit, young Mattie finds her father’s murderer and is captured by a gang of outlaws who threaten her life.

True Grit (2010), Paramount Pictures.

The symbolism of death is important and can be used literally. The characters may lose a loved one or perhaps even suffer significant injuries themselves. The death may also be metaphoric: perhaps they experience the death of a career or a relationship. This symbolism can emerge subtly through cues in the exterior setting that reflect the character’s inner questioning (e.g., perhaps they pass a funeral or observe a crushed flower on the sidewalk).

It is important that the characters face the “death” of the person they used to be. The challenge here is whether or not they will embrace this death and claim the subsequent rebirth.

The False Victory and the Low Moment The Third Plot Point is made up of two important beats. The thematically crucial Low Moment is preceded by the equally important False Victory. One of the most significant features of this pairing is that it creates a natural arc to the beat. It begins in a seemingly positive state before plunging the characters into darkness. (I talk about this in more detail in my book Next Level Plot Structure.)

The Third Plot Point is made up of two important beats. The thematically crucial Low Moment is preceded by the equally important False Victory. One of the most significant features of this pairing is that it creates a natural arc to the beat. It begins in a seemingly positive state before plunging the characters into darkness. (I talk about this in more detail in my book Next Level Plot Structure.)

Even more significant is that this pairing creates the bridge between the “action phase” of the Second Act into the full-on transformation of the Third Act. Throughout the Second Act, particularly after the Midpoint, the characters have been rapidly progressing in their ability to understand the nature of both the internal and external conflict. Thanks to the Moment of Truth at the Midpoint, they recognized the potency of the story’s central Truth and began integrating it into both their internal landscape and their tactics in the external plot.

But there’s a catch.

Even though the characters claimed the Truth at the Midpoint, they have not yet fully rejected the Lie. Throughout the Second Half of the Second Act, they continued to cling to certain of their old limited perspectives from the First Act. More than that, as they became more and more proactive toward the end of the Second Half, they failed to see their blind spots. This leads them directly to the False Victory at the beginning of the Third Plot Point.

Whatever happens here is the result of a tactic the characters deliberately employed to reach their goal. They may have believed this gambit was the one that would finally lead them to success. Even if they were back on their heels and making a desperate choice, they acted according to everything they learned up to this point—but without realizing they have yet to fully face their blind spots.

This leads them to the Low Moment. In some stories, the False Victory will be only a short moment of hope before everything falls apart. Even in stories in which the False Victory is truly victorious in some way, the characters will suffer collateral damage. Sacrifices will be made, sometimes willingly, but usually because the characters’ choices create dire consequences. This will lead them to their soul-searching and, if they successfully transform, the complete death of their old Lie and complete rebirth into the New Truth.

For Example:

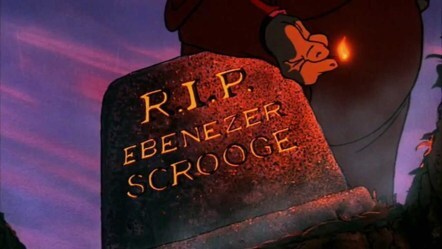

In What About Bob?, the protagonist Bob shows clear signs of improving his neuroses, but this leads directly to the mental breakdown of his psychiatrist Leo, which prompts Leo’s family to ask their friend Bob to leave.In Toy Story, Woody is on the brink of escaping from Sid’s room back to Andy’s house, only to have his plans thwarted when the rest of Andy’s toys see Buzz’s dismembered arm and believe Woody has hurt him once again.In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge joins the third and final spirit, having been much changed by his previous visitations, only to be shown a doomed future that includes his own death and that of Tiny Tim.

Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983), Walt Disney Pictures.

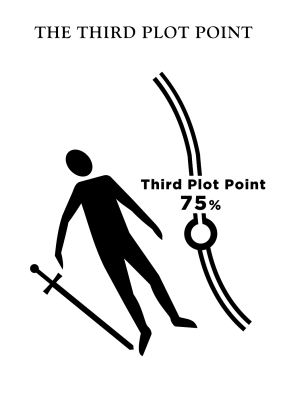

Where Does the Third Point Belong?The Third Plot Point takes place at the 75% mark. Like the First Plot Point’s threshold between the First and Second Acts, the Third Plot Point creates a threshold between the Second and Third Acts. It is not properly a part of either act but provides the portal between them.

Timing becomes trickier the closer you get to the end. In longer works, such as novels, it can be easy to get carried away in the Second Act, but this can sometimes cramp the Third Plot Point. Alternately, in shorter works such as films, we often see an overemphasis on the Climax that ends up short-changing either the Third Plot Point’s Low Moment or trying to get it over with as early as the Second Pinch Point at the 62% mark. Although timing and pacing are never hard and fast propositions, it is important to evaluate the big picture of your story’s structural timing. Assess whether any structural sections are getting short-changed. Particularly when it comes to the transformational beats—the First Plot Point, the Midpoint, and the Third Plot Point—ensure they receive the spotlight they deserve.

The events of the Third Plot Point may create a lengthy sequence comprising the first half of the Third Act, leading right up to the Climax. There is much for the characters to experience and react to in this beat, all of which will lay the groundwork for their ability to take definitive conflict-ending action in the Climax. In action stories, most character arc adjustments should be completed before the Climax begins. In more relational stories, the Climactic Moment may be the character’s final decision about how to act upon the story’s Truth. Regardless, the Third Plot Point and subsequent scenes must be fully developed to provide a sound foundation for the story’s ending.

Examples of the Third Plot Point From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: Just as Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy begin to grow closer while spending time at his Pemberley estate, word comes that Elizabeth’s youngest sister Lydia has run away with the scoundrel Mr. Wickham. Elizabeth must return home, not only fearing the worst for her sister and her family, but also believing Lydia’s scandalous actions have caused Mr. Darcy to revile her family forever.

Pride & Prejudice (1995), BBC1.

It’s a Wonderful Life: After looking everywhere for the money Uncle Billy lost, George is forced to his lowest point when he approaches his nemesis Mr. Potter for a loan. When he offers his life insurance policy as collateral, Potter scoffs, “Why, you’re worth more dead than alive!” George sinks into soul-wrenching desperation as he drives to the river and contemplates killing himself so the policy can be cashed to repay the money.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

Ender’s Game: Ender is forced into a fatal confrontation with the bully Bonzo. In a display of the ruthlessness that has made him so successful at Battle School, he kills Bonzo. He is devastated by his actions and nearly gives up on Battle School, fleeing to his family on Earth to contemplate who he is becoming.

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: This film provides an example of a Low Moment timed to take place at the Second Pinch Point, as Captain Jack Aubrey’s best friend Dr. Stephen Maturin is accidentally shot aboard ship. For the first time, Jack abandons his obsessive pursuit of the French privateer and takes his friend to the Galapagos Islands so he can be safely operated upon. The later turning point into the Third Act occurs when the Acheron is sighted nearby, setting up the final confrontation. This is not a Low Moment for Jack, but still sketches the beat’s emotions by being told through Stephen’s perspective and showing his disappointment that he will now have to abandon his long-awaited expedition to the Galapagos.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the Third Plot PointThe Third Plot Point occurs at the 75% mark, providing a bridge between the Second and Third Acts.The Third Plot Point may be an utter upheaval of the gains the characters thought they made in the Second Half of the Second Act (as in Pride and Prejudice), an unexpected event (as in It’s a Wonderful Life), a personal decision (as in Ender’s Game), or a meeting between protagonist and antagonist (as in Master and Commander).The Third Plot Point begins with a False Victory, in which the characters use what they learned in the Second Act to try to gain the plot goal. They may experience a win or just the expectation of one.The Low Moment follows on the heels of the False Victory and prompts the characters into deep soul-searching as they contemplate their choices and actions.If the characters can successfully see through their blind spots to reach the story’s central thematic Truth, they can rise back up to definitively approach the plot goal in the Climax.The Third Plot Point proves how far your characters have come on their personal journeys and whether they can integrate everything they’ve learned. The Climax is coming up next, and they will need to consolidate all their growth to reach their plot goal.

Stay tuned: Next week, we will talk about the Climax.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What happens in your story’s Third Plot Point? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Part 6: The First Half of the Second Act

Part 8: The Second Half of the Second Act

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Third Plot Point (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 10 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 23, 2024

The Third Act (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 9 of 12)

The Third Act is what readers, writers, and characters have all been waiting for. This final section of the story is the point. It’s what you’ve been building up to all this time. If the First and Second Acts were engaging and aesthetic labyrinths, the Third Act is where X marks the spot. You’ve found the treasure. Now it’s time to start digging. Like the previous acts, the Third Act opens with a bang, but unlike the other two acts, it never lets up. From this point on, everyone is in for a wild ride. All the threads you’ve been weaving up to this point must now be artfully tied together.

The Third Act is what readers, writers, and characters have all been waiting for. This final section of the story is the point. It’s what you’ve been building up to all this time. If the First and Second Acts were engaging and aesthetic labyrinths, the Third Act is where X marks the spot. You’ve found the treasure. Now it’s time to start digging. Like the previous acts, the Third Act opens with a bang, but unlike the other two acts, it never lets up. From this point on, everyone is in for a wild ride. All the threads you’ve been weaving up to this point must now be artfully tied together.

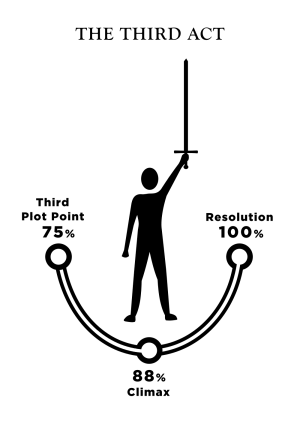

The Third Act occupies the book’s final quarter, beginning around the 75% mark and continuing until the end. This is a relatively small portion of the story, particularly when considering all that must be accomplished.

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

Within the Third Act, we find the final four structural beats:

The Third Plot Point – 75%The Climax – 88%The Climactic Moment — 98%The Resolution – 100%

The Third Plot Point, which we will discuss next week, is the final major turning point within the story. Like the First Plot Point, it does not explicitly belong to either the Second Act that precedes it or the Third Act that follows it. Rather, it creates the threshold between the two. Often referred to as the Dark Night of the Soul, the Third Plot Point is a moment of reckoning in which the protagonist faces the consequences of previous choices and decides how to re-commit to a final pursuit of the plot goal.

The Climax, which we will discuss in Part 11, begins roughly halfway through the Third Act. It signals the protagonist’s final push toward the plot goal and the final confrontation with the antagonistic force. It will decide the outcome of the conflict once and for all, determining whether or not the protagonist will gain the plot goal.

The Climax, which we will discuss in Part 11, begins roughly halfway through the Third Act. It signals the protagonist’s final push toward the plot goal and the final confrontation with the antagonistic force. It will decide the outcome of the conflict once and for all, determining whether or not the protagonist will gain the plot goal.

Finally, the Third Act ends with the Resolution, which we will discuss in Part 12. After the conflict has been decided in the Climax, the Resolution offers a last moment to tie off loose ends and show how the characters have been affected by the story’s events.

One reason the Third Act picks up the pace compared to the previous acts is the simple necessity of cramming in everything that needs to be addressed before the book runs out of time and space.