K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 7

August 26, 2024

The First Half of the Second Act (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 6 of 12)

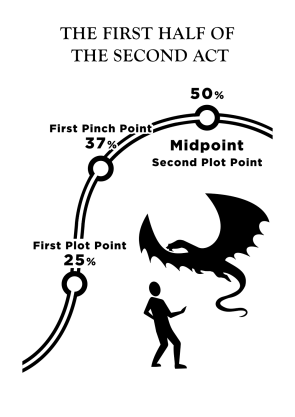

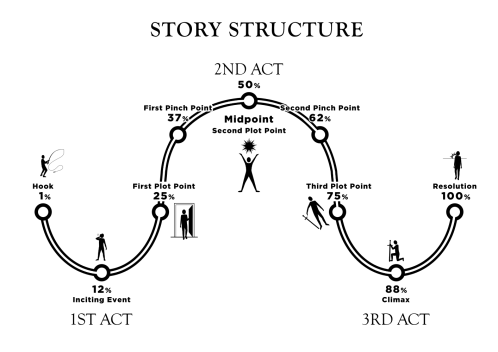

Every segment of a story offers its own challenges, but perhaps none leaves more writers bewildered than the Second Act. At least beginnings and endings provide a checklist of things to accomplish. The middle of the story, on the other hand, is a yawning blank. You may feel like you’re entirely without a guide as you try to move your characters toward where they need to be for the ending to work. Fortunately, if you pay attention to solid story structure, you’ll find that the middle of the story has a checklist all its own. The Second Act is the largest part of your story, comprising roughly 50%. It begins after the First Plot Point at the 25% mark and continues until the Third Plot Point at the 75% mark.

Every segment of a story offers its own challenges, but perhaps none leaves more writers bewildered than the Second Act. At least beginnings and endings provide a checklist of things to accomplish. The middle of the story, on the other hand, is a yawning blank. You may feel like you’re entirely without a guide as you try to move your characters toward where they need to be for the ending to work. Fortunately, if you pay attention to solid story structure, you’ll find that the middle of the story has a checklist all its own. The Second Act is the largest part of your story, comprising roughly 50%. It begins after the First Plot Point at the 25% mark and continues until the Third Plot Point at the 75% mark.

Within the Second Act, we find three structural beats, once again falling at eighths within the overall structural timing:

The First Pinch Point – 37%The Midpoint (Second Plot Point) – 50%The Second Pinch Point – 62%

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

This week, we will discuss the First Half of the Second Act, which includes the First Pinch Point. Next week, we will devote an entire post to the Midpoint, and the following week we will cover the Second Half of the Second Act and the Second Pinch Point.

The First Half of the Second Act is the “reaction phase” of your story. This is where your characters find the time and space to react to the First Plot Point. Remember how we discussed the First Plot Point being definitive because it forced the characters into irreversible reaction? That reaction, which will lead to another reaction and another and another, creates your Second Act.

The First Plot Point hit your characters hard. Now, their lives are no longer running on the same smooth paths, and they have to do something about it. If you examine the First Plot Point in a story, you will see it is the characters’ reactions to the event that change everything and create the story. Even when the First Plot Point incorporates a life-altering tragedy (e.g., the murder of Benjamin Martin’s son and the burning of his plantation in The Patriot), the characters could conceivably continue their lives more or less as they had before. It’s their reaction (e.g., Martin’s becoming the “ghostly” militia leader who terrorizes the British army) that allows the chain of events to continue—and create a story.

The Patriot (2000), by Columbia Pictures.

This is why introducing characters and other crucial elements in the First Act is so important. If you fail to properly set up the protagonist as someone who would logically react in the way necessary to facilitate the Second Act, your story will implode. When searching for the appropriate Characteristic Moment to introduce a character, consider an event that will reflect, inform, or contrast the character’s reaction to what happens later at the First Plot Point.

For the next quarter of the book, until the Midpoint, your characters will react to the events of the First Plot Point. They will take action, but all these actions are a response to what’s happened to them. They’re trying to regain their balance and figure out where their lives should go next.

For Example:

In my medieval novel Behold the Dawn, the characters spend this part of the book on the run from the bishop who wants them dead.In Brent Weeks’s The Way of Shadows, the protagonist spends years reacting to the orders of his master.In Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur, the protagonist is forced into a reactionary role as a galley slave after he’s unjustly captured and sentenced at the First Plot Point.

Ben-Hur (1959), MGM.

Just because the characters are comparatively reactive in this phase does not mean they are passive. However, even though they are making choices and trying to move forward toward the plot goal, they are not yet able to be genuinely effective in doing so. Not until they reach a Moment of Truth at the Midpoint will they see themselves and the plot conflict in a clearer light. This will then allow them to switch into an “active phase,” in which their choices and actions become increasingly informed and calibrated in the Second Half of the Second Act. This is why the First Half of the Second Act is often where the character is learning the rules of the game—whether those are the nuances of a new relationship, the tricks of the trade in a new job, survival skills, or the social structure of a new neighborhood.

The First Pinch Point The First and Second Pinch Points are paired beats, both occurring in the Second Act, one prior to the Midpoint and one after. Although pinch points are just as structurally integral as plot points, they won’t always be represented by huge scenes. Their primary role is to provide a “pinch” that reminds the protagonist of the formidable obstacle represented by the antagonistic force and what is at stake should the protagonist fail.

The First and Second Pinch Points are paired beats, both occurring in the Second Act, one prior to the Midpoint and one after. Although pinch points are just as structurally integral as plot points, they won’t always be represented by huge scenes. Their primary role is to provide a “pinch” that reminds the protagonist of the formidable obstacle represented by the antagonistic force and what is at stake should the protagonist fail.

The First Pinch Point takes place halfway through the First Half of the Second Act at the 37% mark. Here, the antagonistic force can flex its muscles and impress with its capacity to disrupt the protagonist’s forward momentum. This moment serves primarily to set up the change of tactics the protagonist will soon learn. By reminding readers of the antagonist’s power, the First Pinch Point raises the stakes and foreshadows the central turning point at the Midpoint. Like all major structural beats, the First Pinch Point should focus on the central conflict rather than a subplot.

For Example:

The antagonist might jab at your protagonist’s weakness, as in Ever After, when the wicked stepmother exults to Danielle about the probability of her daughter marrying the prince.The protagonist might fail in his fight against the antagonist and be mocked or reprimanded for it, as in the film Warrior when Brendan’s brother Tommy rejects his attempts at reconciliation.If your story features your antagonist’s POV, your First Pinch Point might simply be a reminder of what the antagonist is planning, as in Captain America: The First Avenger when the Red Skull murders his superiors and goes rogue or as in The Empire Strikes Back when Emperor Palpatine tells Darth Vader that Luke Skywalker is their new enemy.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

Character Realizations After the First Pinch PointAlthough the entirety of the First Half of the Second Act is a story’s “reaction phase,” the degree to which the characters shift out of reaction and into action will steadily evolve as they learn new skills. By the time they reach the Midpoint, they will encounter a definitive turning point that offers a concrete epiphany about themselves and the nature of the plot conflict. The events at the First Pinch Point will contribute to that process.

Whatever the characters learn at the First Pinch Point, even if it is just that the antagonist is more formidable than they thought, will fuel their continuing growth toward effectiveness in the plot. The section after the First Pinch Point and leading up to the Midpoint will solidify a state of realization for the protagonist. Think of these realizations as clues leading the characters to the major revelation at the Midpoint. A story’s most significant revelations—those that irrevocably change things for the protagonist and thus turn the plot—should be saved for the main structural turning points. However, most stories will require a chain of minor realizations that evolve the characters’ perspectives leading up to these seismic shifts.

For Example:

In Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, the Midpoint declaration of love is preceded by the section in which the protagonist must internally grapple with and admit he is in love with a woman who is not his fiancée.In Little Women, the Midpoint revelation is Jo’s quiet Truth that life inevitably changes as everyone begins to grow up; this is preceded by a section in which many smaller changes occur, including her best friend Laurie going away to college.In The Martian, the Midpoint revelation is the stranded astronaut’s acknowledgment that he will probably die on Mars if he continues his current tactics. This is preceded by a section of small tragedies that successively limit his ability to survive.

The Martian (2015), 20th Century Fox.

Examples of the First Half of the Second Act From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: After Bingley leaves Netherfield Park at Darcy’s prompting (the First Plot Point), Elizabeth and her sisters can do little except react. Jane goes to London to visit her aunt and to discover why Bingley left. In the absence of Mr. Wickham, Elizabeth pays an extended visit to her friend Charlotte (the new Mrs. Collins). While there, she again meets Mr. Darcy and is forced to react to his perplexing attentions.

Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.

It’s a Wonderful Life: Even after the First Plot Point in which his father dies of a stroke, George’s life could have progressed exactly as he wanted it to. But when he reacts to Mr. Potter’s attempts to close down the Building & Loan by agreeing to stay in Bedford Falls and take his father’s place, his life is forever changed. For the next quarter of the movie, we find George adjusting to life in Bedford Falls. When his brother Harry (who was supposed to take George’s place in the Building & Loan) gets married and takes another job, George is again forced to react. He accepts he must stay in Bedford Falls, and he marries Mary Hatch—reactions that build upon his initial decision to preserve the Building & Loan.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

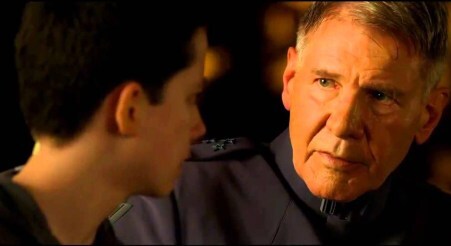

Ender’s Game: After joining Bonzo’s Salamander Army, Ender struggles to stay afloat in Battle School. He learns to fight—and win—in the zero-grav war games. He makes friends and enemies and sets in motion the events that will later cause the standoff between him and the bully Bonzo. Everything he does in the First Half of the Second Act is a reaction to his presence in Battle School in general and his promotion to Salamander Army in particular.

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: Captain Jack Aubrey and his crew spend the First Half of the Second Act reacting to their second sighting of the Acheron. After turning the tables on the enemy ship, Jack subsequently loses her during a tragic accident at Cape Horn and is forced to devise new plans and methods for managing his crew until they reach the Galapagos Islands.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the First Half of the Second ActThe characters should react promptly and irrevocably to the events of the First Plot Point.Because the characters’ lives and plans have been significantly altered, they must find new ways of dealing with the world in general and the main antagonistic force in particular.Their reactions should be deep and varied enough to create the next quarter of the story.Their reactions must be dominoes, moving the plot forward and deepening the weave of scenes, subplots, and themes.Often, this section is where the characters will gain the skills or items necessary for the final conflict in the Third Act.At the First Pinch Point, the protagonist will be pressured (either in person or even from afar and without knowing it) by the antagonistic force.The First Half of the Second Act deepens character development and foreshadows meaningful elements. Even in fast-paced action stories, this will often be the most thoughtful portion of your story as you finish building the foundation your characters will stand upon during the Climax.

Stay tuned: Next week, we will talk about the Midpoint, or Second Plot Point.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do ever you struggle with the Second Act in your stories? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The First Half of the Second Act (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 6 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 19, 2024

The Secret to Writing Strong Themes

Today, I want to talk about writing strong themes, because there’s a lot of misunderstanding around the concept of theme (which is why I wrote the book Writing Your Story’s Theme). When we think of theme, we often think of a one-word or short phrase aphorism. For example, maybe the theme of the story is “love” or maybe it’s “overcoming a sense of unworthiness” or something like that. While that is very possibly what the story is about and what the theme is pointing to, that isn’t necessarily a good roadmap for helping you learn how to write strong themes. It’s valuable to look a little deeper and to understand how theme actually operates within a story, what its function is, and therefore how you can use the other elements of your story to consciously create the theme you want to create.

Today, I want to talk about writing strong themes, because there’s a lot of misunderstanding around the concept of theme (which is why I wrote the book Writing Your Story’s Theme). When we think of theme, we often think of a one-word or short phrase aphorism. For example, maybe the theme of the story is “love” or maybe it’s “overcoming a sense of unworthiness” or something like that. While that is very possibly what the story is about and what the theme is pointing to, that isn’t necessarily a good roadmap for helping you learn how to write strong themes. It’s valuable to look a little deeper and to understand how theme actually operates within a story, what its function is, and therefore how you can use the other elements of your story to consciously create the theme you want to create.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

In the past, a common statement that has floated around the writing community is that “writers should never consciously write the theme.” There is some truth to this (which I’ll talk about in just a second), but ultimately, I adamantly disagree with this idea.

What this is really pointing to is the truth that writers never want to preach at their readers. You don’t want to try to start with some message you’re trying to share about the world and then shoehorn that into your characters’ mouths or their perspectives of the world and try to prove it through whatever is happening in the story. You don’t want to come into a story to prove, for example, some political statement. Readers don’t want that. It doesn’t work within the story because it isn’t organic or it doesn’t flow. It feels, even if the author isn’t actually preaching at you, that they’re trying to jam some specific moral message into a story that doesn’t fit.

However, I think this unfortunate effect most often happens simply because the writer has an idea of theme but doesn’t understand how it actually works within storyform. If you do understand how theme operates, you’re much less likely to end up with fragmented themes, in which your story is saying one thing while you’re trying to say something else with the theme. Likewise, you can also avoid the problem of getting to the end and realizing what you thought was your story’s theme doesn’t seem to have anything to do with what’s actually happening.

In either case, you can end up having either stories that seem very disjointed, or even two different endings that are trying to individually address the plot and the theme. This creates a story that doesn’t feel cohesive and resonant.

However, if you understand what you’re doing and how story creates them, then you can accomplish two things.

1. You can consciously create anything you want to create within the realm of your story.

2. Perhaps most importantly, you can double-check and troubleshoot what isn’t working. If you get to the end of the story and you feel your theme is off the rails or nonexistent, you can go back and check what happened by asking, “Where do I need to work with the story in order to make the theme more powerful and pertinent?”

What Is Theme, Really?The most important thing to understand about theme is that it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s not its own thing within the story. It’s part of the greater whole. Specifically, it forms what I call “the trifecta” of plot, character, and theme. These three elements of story create each other; they do not exist by themselves in isolation. One necessarily creates the other.

We sometimes hear the idea of plot versus character, as if they were two totally separate things, when really they can’t be. The plot has to create the character, the character has to create the plot. Theme is the third part of that.

Here’s the thing: if you have a functional story that’s working, what that means is that all three of those things—plot, character, and theme—are working. Even if you’re not conscious of theme—even if you didn’t do it on purpose, so to speak—if all three are in cohesion with one another, that’s what you want. If you can bring consciousness to your administration of theme, then you can do it on purpose.

Here’s how it works. Let’s say you come up with an idea for a plot. Necessarily, there must be characters in that plot. Although it may take a little time, as you flesh out that plot in your mind, you will begin to understand what kind of people are driving this plot. What kind of people are interested in going to the places and achieving the things that you want to see happen in this plot?

This works in reverse as well. If you start with an idea for a character, obviously you don’t have anything for them to do until there’s a plot. So pretty soon you start getting ideas for what these characters will do. What are they interested in? How are they interacting with other people? What do they want? What are they moving toward? Suddenly, you have a plot. Plot and character are not separate. One necessarily creates and brings with it the other.

The same is true of theme.

How Plot and Character Arc Create Theme

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The interaction between plot and character is the engine that creates theme. We talked about in the last video about the Lie the Character Believes and how that creates this entire arc of the character’s evolution as they change their perspective, as they evolve into a new way of being and a new identity within the world. That’s character arc. And this new understanding of the world is something that has to be acted upon. It’s not just something happening in the character’s head. Otherwise, there’s no reason for the change to happen within the plot. It will be just an expression of philosophy, not a story. You have to bring this change of perspective into the action of the plot. Show what the character is going through, dramatize it through the events of the plot.

The events of the plot and the arrival of the conflict prompts the need for this change within the character. And then the change inside the character also allows them to evolve and grow what they’re doing in the external plot. If they remained the same, then either they wouldn’t be motivated to go on this story’s adventure at all or, depending on the type of story, the events of the plot will destroy them. They’ve got to evolve in order to survive. They’ve got to evolve in order to reach this next level of whatever it is the story wants them to achieve, whether that’s a relationship or a new job or saving the world or whatever the case may be. Some quiet literary stories really are just about changing that inner landscape. Whatever the case, this change must be proven in some way. It must be acted out within the plot.

Using Your Plot as a Thematic MetaphorI like to think of the plot as a metaphor for whatever the character is changing internally, for the story’s Lie and Truth. Let’s say you start with the character’s Lie and Truth. And from there, you ask yourself what can the character do physically in the world that would dramatize and show this inner transformation from Lie to Truth.

An easy example of this would be The Hunger Games, in which the protagonist Katniss Everdeen follows a Flat Arc. This means she doesn’t change her perspective; she doesn’t grow from Lie to Truth. Instead, she uses her understanding of the Truth to change the world around her. In this case, that Truth would be her understanding that “oppression is no good,” that this Lie that has been fed to her country Panem by its oppressive government is that “their control is necessary to protect them” and the brutality of the Hunger Games is also necessary. Katniss begins her story understanding this is not true, as many people in her world do. What makes her an interesting character and protagonist is that her story gives her the opportunity to act on that Truth.

Specifically in this story, we can see how the entire premise of the Hunger Games—the entire scope of the plot in this story—is a very specific dramatization of her story’s Lie and Truth that allows her to go out and actively battle this oppression. She’s basically put in a cage and has to fight her way out. That’s a very explicit example of how your plot can operate as a thematic metaphor.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

When you’ve got plot and character working together beautifully, we might say one is proving the other. From this, we get a theme. Even if you try to paste on a different kind of a theme, the events of your story and how your character responds to them and interacts with them is what inevitably creates the theme. That is the point of your story; that is the message of your story. The thematic Truth that will be proved by the end of your story is whatever is shown by the events of the story. Whatever is effective in your story is your story’s Truth. This can be something very practical such as a skill, but it can also be just an effective perspective that the characters hold of themselves or the world (e.g., self-worth).

Using Plot and Characters to Identify Your Story’s ThemeWhen you approach a story from the idea that plot, theme, and character are all equal members of the equation and that necessarily one creates the other, it allows you to make sure you’re creating a cohesive cycle. And also, when you’re running into problems, it allows you to stop and check.

Let’s say you’re having problems with your theme. “I don’t know what my theme is.”

Look at your character’s arc and specifically at the Lie the Character Believes. Look at what they need to overcome by the time they get to the end of the story and therefore what Truth they’re moving toward. That Truth is usually a very specific and easy way to sum up your story’s theme.

You can also look at the events of the plot.

What are the characters doing?What is happening?What is challenging them?Where do they fail?What do they have to do to succeed?How do they have to change in order to become someone who can succeed in gaining the plot goal within your story?This is where you can start looking for a theme and vice versa.

Using Theme to Create Your Plot and Character ArcsLet’s say you start out knowing you want to write a story about “love conquers all”—that’s your theme, that’s what you want to write about. There’s no reason you can’t start with just that. Now you have a map for determining what kind of characters and what kind of character arc will help exemplify this.

How will they be challenged to grow into this?What Lie might oppose this idea?What events of the plot will be an interesting way to explore all aspects of this idea?

Story by Robert McKee (affiliate link)

Deepen Your Themes With the Thematic SquareThis is where it can be really helpful to bring in a technique that Robert McKee wrote about in his book Story, which he called the Thematic Square. Start by examining your story’s thematic Truth from multiple perspectives. This prevents it from being just this simple black-and-white approach, i.e., “this is the wrong way to do it, and this is the right way to do it.” That approach is simplistic and can be on the nose and ultimately unconvincing to readers because that’s not really how it works for most of us most of the time in real life. If it was that simple, we’d always think, Ah, truth. I want to do that. I pick that one because obviously it’s better. It’s obviously going to be more effective and help me get what I want, what I need, and what’s good for me.

But it’s not that simple, right?

There are many shades and complexities to this evolution of perspective because the Lie and the Truth are actually never black and white. Rather, they represent an evolution along the spectrum, from a limited perspective to a broader perspective. Ideally, you want to be able to explore the complexities around this idea.

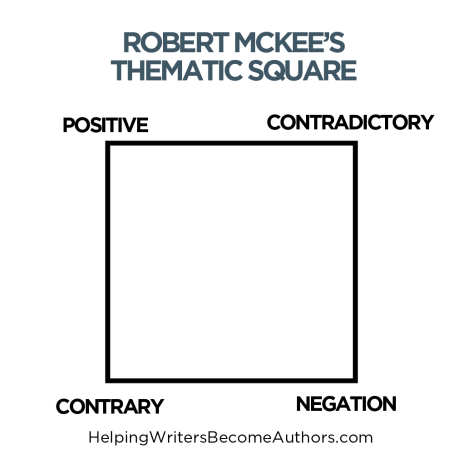

The Four Corners of the Thematic SquareYou can do this, via McKee’s Thematic Square, by creating a square with four corners that represent four different sides or points of the thematic premise you’re exploring.

First and foremost, you have the Positive corner. Positive represents the story’s Truth. This is the good stuff you’re trying to posit in your story, i.e, “this is the way we should be”—whether the character embraces it and succeeds or fails to embrace it and fails within the story. This is the positive Truth you are suggesting is the best way for the characters to behave in this story. Examples of this would be Respect or Love. These are good qualities. These are things that we recognize as something we want to to embody in our lives, because they will help us to be more effective in whatever we’re doing.

The Contradictory Thematic StatementOpposite that is the Contradictory corner. This represents something that is directly contradictory to the story’s positive Truth. At its simplest, this is the Lie. This is what stands opposed to the story’s Truth. In simple one-word explanations of what these might be, we have in opposition to Respect, Disrespect. In opposition to Love, we have Hate.

The Contrary Thematic StatementThose two are obvious; they’re an obvious polarity. From there, you can start moving down to the bottom corners of your square and think about, first of all, what would be an element within this thematic exploration that would be Contrary to the Positive.

The word contrary always makes me think of somebody who’s being contrary: they’re just being annoying. They’re just being stubborn and refusing to see things. It’s not necessarily that they represent or are directly opposed to the argument, but they’re just refusing to do it. They’re opting out, saying, “talk to the hand,” as we used to say. The Contrary perspective wants to bypass the whole thematic argument. In some ways, this makes it more dangerous than the contradictory aspect, which at least is looking at the Truth—looking it in the eye and doing battle with it. In contrast, the Contrary aspect just wants to skip it. It doesn’t even want to engage with this Truth.

An example of this for a theme of Respect, could be Rudeness. Rudeness is passive-aggressive. “I don’t respect you, but I’m not actually doing you the service of coming to your face and telling you that either.” For Love, the Contrary aspect could be Indifference, which in many ways can be more painful than Hate in some relationships. We often say love is hate flipped on its head, with the idea being that if you can dig down there in the hate, you might be able to find love in the shadow and integrate it. Indifference, however, says, “I don’t care about you. You don’t exist to me. You’re dead to me. I don’t think about you at all.” And this can be more painful and certainly more difficult to move through toward that more positive Truth.

The Negated Thematic StatementFinally, we have what McKee calls the Negation of the Negation. This is the Lie taken to its farthest extreme. It’s taken to such an extreme that it’s as if the Truth doesn’t exist. It rewrites reality. Over the course of the story, a Negation character will be given an opportunity to see the Truth and how it could potentially positively impact their life. But for whatever reason, they reject it and end up in a worse place than when they just believed the Lie or the Contradictory aspect.

In our example of Respect, the Negation of the Negation would be Self-Disrespect. Usually, even if someone disrespects someone else, there’s that place within their own ego where they are still standing within their own sense of identity and pride of self in opposition to something else. However, with Self-Disrespect, they can’t even respect themselves. If there isn’t even that ego container to hold their own identity, that is, in many ways, a worse place to be than if you’re just this egoic person disrespecting everybody else. It’s an almost plague-like effect. The seed of the Lie takes over the person’s entire being and life and perhaps beyond depending on the type of story you’re telling. The example McKee uses as the Negation of Love is Self-Hatred. Again, the Negation sees the character moving into a place where love doesn’t even exist in their universe.

How to Implement the Thematic Square in Your Story

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

One of the best ways to explore the Thematic Square is to have your protagonist represent any one of the thematic corners with the antagonistic force representing the polar opposite. Depending on whether you’re telling a Positive Change Arc, a Flat Arc, or a Negative Change Arc, your protagonist may or may not represent the Positive statement.

You can also use the Thematic Square to deepen this thematic complexity by looking for ways in which multiple characters—at least four characters—represent the different aspects of the square. This gives the protagonist a chance to interact with all of them, to be challenged by all of them, and to see the pros and the cons of each one so that they’re challenged. Their exploration of the theme will no longer be a simple binary choice between, “Oh, the Lie is bad and the Truth is better, so of course I’ll choose the Truth.” Rather, they have to move through all of these shadow aspects of the Lie and the Truth, to explore them, and to be challenged by them.

If your project uses characters to represent all four aspects, this also helps you develop and deepen the opportunities for your plot. Make sure every character’s actions, everything that’s happening, any opposition the protagonist faces from antagonistic forces is all thematically pertinent.

No thematic position in your story should be random. If the protagonist is trying to move toward a thematic Truth of “Love,” you don’t want another over here focusing on Freedom and Slavery. That’s a totally different theme. Of course, there can always be crossover—because ultimately everything is interconnected in real life. But applying the Thematic Square to your story can help you recognize which ideas don’t support the point of your story. If something doesn’t support the plot’s throughline and doesn’t support the protagonist’s individual arc, ask yourself how you could repurpose it so it informs the central theme.

Find Your Theme by Examining Your Story’s EndingWhen thinking about how best to integrate theme into plot and character arc, look at how your story ends. The ending of your story—your Climactic Moment—will prove what your story was really about. This means it will prove what your theme is really about.

The decisions your characters make in the end, the perspectives they use to inform their choices and actions, as well as their ability to gain their plot goal—all of these things reveal your story’s theme. Examine the questions your story raises and the answers it ultimately ends up giving.

This does not mean that you need to end with some kind of moral of the story or with the mentor character coming out and giving a little speech about the lesson to be learned or something like that. Your story’s “answer” is simply whether or not the characters were effective and how they end up.

Did they end in a better place physically, spiritually, emotionally, and mentally?Or is it a worse place?If it’s a better place, then the story’s Truth (i.e., the “answer” to the questions that have been raised throughout the story), is “yes, this is an effective way of being in the world. This is a good course of action.”

If the characters fail, either ambiguously or definitively, then what the story is saying is “this is not a good way of being.” Such a story becomes, even without any need to create a moral of the story, a cautionary tale.

Find Your Theme by Examining Change and Consequence in Your PlotFinally, think about how your story will develop change and consequence.

Change, both within your story’s character arcs and within the context of how your characters are able to enact change in the outer world of the story will prove what the story is really about. It will show you how your theme develops, what thematic questions are at play, and what answers the plot ultimately posits.

Specifically, think about consequences. Consequences aren’t always something negative. From a causal perspective, consequences can be something good. However, more often, consequences reveal a hard pill to swallow. Not only can consequences sometimes prove that “oops, the characters did not choose the best way of being. They did not choose the story’s Truth,” but consequences can also offer a resonant way to drive home that this path of change, this path of evolution that we’re all on within our lives, isn’t easy. It’s not cut and dried. It’s not black and white.

Again, if theme was simply “Lie versus truth—this is worse and this is better,” we’d always choose the right thing. There would be no need for stories because we’d always choose the right thing. Stories show us that there are, in fact, consequences even for choosing the right thing, for choosing what’s best for us, for choosing something we believe is in the best interest of ourselves and our communities and our world. Stories show us life isn’t simple, that there are always sacrifices, that letting go of a Lie or dealing with people who aren’t ready for us to let go of the Lie—it’s not easy. Embracing the Truth is often difficult.

Examining the consequences your characters face or could face if you deepen your story can be helpful in showing you not just your story’s theme, but how to deepen it and then explore all of the depth of it. Go into the shadows and explore the profundity of change. Ultimately, that’s what theme in story is about.

Admittedly, theme is an abstract concept. Zooming in and thinking of it in terms of plot and character makes it more concrete and easy to master within your story. Again, I’ve written a whole book about theme. So if you want more, you can check out Writing Your Story’s Theme.

Happy writing!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think is the most challenging part of writing strong themes in your stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Secret to Writing Strong Themes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 12, 2024

The First Plot Point (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 5 of 12)

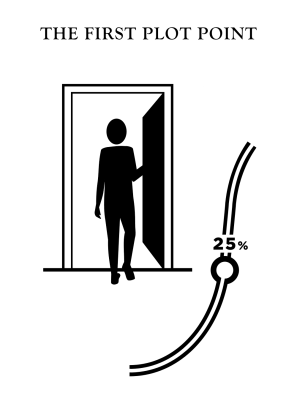

The First Plot Point is a linchpin in narrative architecture. This pivotal moment thrusts the protagonist into a new and irrevocable direction. Positioned around the 25% mark, it serves as a seismic shift, propelling the tale from the initial groundwork of the First Act into the uncharted territory of escalating tension and conflict.

The First Plot Point is a linchpin in narrative architecture. This pivotal moment thrusts the protagonist into a new and irrevocable direction. Positioned around the 25% mark, it serves as a seismic shift, propelling the tale from the initial groundwork of the First Act into the uncharted territory of escalating tension and conflict.

This juncture marks the end of the story’s setup and catapults characters and readers alike into the heart of the narrative arc. By introducing a significant development (often a challenge or revelation) that forces the protagonist to confront the core conflict head-on, the First Plot Point drives the story forward with a cascade of consequences. As a catalyst that shapes the plot’s trajectory and sets the stage for the ensuing drama, it is one of the most critical cornerstones in storytelling.

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

What Is the First Plot Point? The First Plot Point signals the transition from the setup of the First Act into the full-on immersion of the Second Act. Up to now, the story has focused primarily on setting the stage and laying the groundwork for what will follow. From here, the story will use this foundation to create the back-and-forth drama of the characters pursuing their goals and confronting obstacles.

The First Plot Point signals the transition from the setup of the First Act into the full-on immersion of the Second Act. Up to now, the story has focused primarily on setting the stage and laying the groundwork for what will follow. From here, the story will use this foundation to create the back-and-forth drama of the characters pursuing their goals and confronting obstacles.

The First Plot Point kicks off the main conflict by ensuring that two potent ingredients fuse to create the alchemy of plot. The first of these ingredients is your protagonist’s plot goal. Although the main plot goal may have been explicit throughout the First Act, it is more likely to have originated in this early section of the story as a vague or unformed desire. This could also be expressed to readers by dramatizing circumstances that need to change for your characters.

As the protagonist progresses through the First Act, and especially the Inciting Event, this desire or need will emerge more and more explicitly. By the time the First Plot Point arrives, the motivation will coalesce into a concrete intention that urges the character forward. This intention will continue to evolve over the course of the story as the character arc refines the character’s inner perspectives. What happens at the First Plot Point should create a cohesive throughline of intent to generate this forward momentum.

For Example:

In Ever After, the protagonist’s throughline goal is always saving her family’s farm, even as her desires in her relationship with Prince Henry evolve over the course of the story. Her intentions about the farm motivate and influence her every action in the relationship.

Ever After (1998), 20th Century Fox.

In order to create the plot conflict in the Second Act, the second necessary ingredient that must come into play at the First Plot Point is antagonistic opposition. When we speak about the necessity of “conflict” in a story, what we are really speaking about is the necessity of the character’s forward progress toward the goal being impeded by obstacles. When we speak of the “antagonist” or the “antagonistic force,” what we are really speaking of is whoever or whatever consistently creates those obstacles.

The true significance of the First Plot Point is that it is the moment at which the protagonist’s goal and the antagonist’s opposition join inextricably. In some stories, the antagonistic force and its obstacles may be present in full force right from the beginning of the story, in which case it is the protagonist’s full commitment to the goal that initiates the conflict at the First Plot Point. In other stories, the protagonist may be fully intent on the goal much earlier but does not fully confront opposition to that goal until the First Plot Point. In still other stories, neither the protagonist’s goal nor the antagonistic force’s opposition become fully realized until this moment.

The true significance of the First Plot Point is that it is the moment at which the protagonist’s goal and the antagonist’s opposition join inextricably. In some stories, the antagonistic force and its obstacles may be present in full force right from the beginning of the story, in which case it is the protagonist’s full commitment to the goal that initiates the conflict at the First Plot Point. In other stories, the protagonist may be fully intent on the goal much earlier but does not fully confront opposition to that goal until the First Plot Point. In still other stories, neither the protagonist’s goal nor the antagonistic force’s opposition become fully realized until this moment.

Regardless, the First Plot Point signals a shift out of the Normal World of the First Act. It moves your characters into the symbolic Adventure World of the Second Act, in which they will discover what is at stake if they remain committed to their goal. It is important to note, however, that even should the characters at some point regret their decision to pursue this goal in the face of opposition, they cannot go back to the way things were. The First Plot Point is symbolically a Door of No Return.

By committing to the plot goal and discovering opposition from the antagonist, the protagonist’s choice here changes things. Even in low-stakes stories, the characters’ choice at the First Plot Point will permanently change either themselves or the world around them. Often, this will be dramatized by a change in setting. The character will literally switch “worlds” by moving to a new and more challenging setting. In other stories, in which the main setting remains the same, this can be signified by introducing new elements into the existing setting.

For Example:

In Legally Blonde, the ditzy protagonist is accepted into Harvard Law School. Up to this point, her attempts to get her boyfriend back didn’t create permanent change in her life. By deciding to follow him to law school, the actions she takes forever alter the trajectory of her life—no matter what happens next.

Legally Blonde (2001), MGM.

Where Does the First Plot Point Belong?The First Plot Point occurs around the 25% mark, signaling the end of the First Act. As always, this timing represents an ideal and will be subject to the unique pacing needs of each story. What is most important in timing your First Plot Point is ensuring the preceding First Act has enough space to fully develop and lay the groundwork for the story to come without belaboring events.

Why place the First Plot Point at the 25% mark? Why here and not at the 10% or 40% mark? If you’ve ever watched or read a poorly plotted story that skipped or postponed the First Plot Point, you probably instinctively perceived the story was dragging. Without the turning point of the First Plot Point, the First Act will drag on too long—or, conversely, if the First Plot Point takes place too early, the Second Act will drag.

If you pay attention while watching a movie, you can time the major plot points down to the minute. This makes film an especially valuable medium for studying structure since you can view the entire story structure in one sitting and precisely identify structural beats by dividing the total running time into eighths. You can, of course, also do this with books. Divide the total page count by eight and note what happens near each section. Just remember that the timing in a book will not likely be as precise as in a shorter medium like film.

>>Click here to read structural breakdowns in the Story Structure Database.

You won’t always know exactly where the timing of a specific plot beat falls within your overall story until you have finished it, although you can create rough projections by evaluating how many scenes will take place in each section. However, once you have completed your story and can evaluate the timing of every structural beat within the whole, you can use the timing of the First Plot Point to evaluate whether the first half of the Second Act is proportionally too long or too short.

People often wonder if the First Plot Point is part of the First Act or the Second Act. My view is that the First Plot Point can more properly be seen as a transitional zone between the two. Continuing with the doorway metaphor, we can think of the First Plot Point as a portal between the Normal World and the Adventure World.

Although considered a single beat, the First Plot Point can comprise many scenes forming a cohesive sequence. Particularly if the events of your First Plot Point are shattering and/or you are dramatizing a large-scale action scene, you may require more than a few scenes to realistically create the event you’re trying to convey. I generally time structural beats at the moment the character changes within the larger scene or sequence. In the First Plot Point, this is when the protagonist’s goal becomes inextricably entangled with the antagonist’s opposition. This is the moment from which the protagonist cannot return, the moment when there is no going back.

The Difference Between Plot Points and BeatsYou may sometimes hear the term “plot point” used to reference any moment of change or impact within a story. However, I prefer to use “plot point” to refer exclusively to structural moments of change within the story. Although your story will feature only a specific few structural turning points, it can have any number of beats, some relatively minor, some shockingly huge. Beats are what keep your story moving forward. They mix things up, keep the conflict fresh, and propel your character far away from any possibility of stagnancy.

For Example:

The movie Changeling features several cataclysmic beats in the First Act (including the kidnapping of the heroine’s son at the Inciting Event, the return of the wrong boy, and the police department’s insistence that she accept the child anyway) before her decision, at the First Plot Point, to fight back against the corrupt police department.

Changeling (2008), Universal Pictures.

What differentiates a structural plot point from every other story beat is the fact that everything changes for the character. One reason I capitalize terms when referring to significant structural moments in the plot structure is to emphasize that these beats are particularly important. The First Plot Point marks a place of no return for your characters. It is the beat when the setup ends and your protagonist crosses a personal Rubicon.

Examples of the First Plot Point From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: After the ball at Netherfield Park, Darcy and the Bingley sisters convince Mr. Bingley to return to London and forget his growing affection for Jane. Much has already happened in the story. Jane and Elizabeth have stayed over at Netherfield. Lydia and Kitty have become enamored of the militia. Wickham has turned Elizabeth against Darcy. And Mr. Collins has proposed to Elizabeth. Then everything changes at the 25% mark when Darcy and the Bingleys leave. This is the event that breaks Jane’s heart and infuriates Elizabeth against Darcy. It also changes the story’s landscape, since several prominent characters are no longer in the neighborhood for the Bennets to interact with as they did throughout the book’s first quarter.

Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.

It’s a Wonderful Life: Throughout the first quarter of the story, George Bailey’s plans for his life have progressed uninterrupted. Despite his misadventures in Bedford Falls, he’s headed for a European vacation and a college education. Then the First Plot Point hits. When his father dies of a stroke, George’s plans are dashed. This moment forever changes George’s life, setting the subsequent plot points in motion. As in Pride & Prejudice, the standards that have been established in the story are dramatically altered. This is no longer a story about a carefree young man freewheeling around town. From here, this is a story about a man forced to assume responsibility by taking over his father’s beloved business.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

Ender’s Game: The quarter mark finds Ender graduating to Salamander Army after a victorious confrontation with the bully Bernard. Ender’s assertion of brains, tenacity, and leadership allow him to claim his spot at Battle School. He makes it clear to himself, the other children, and the watching instructors that he will do whatever he must to survive. This First Plot Point also changes the game (no pun intended) by once again moving Ender to new surroundings. As a member of Salamander Army, he is dropped into a new place, new quarters, and a new set of challenges.

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: After refitting the Surprise and heading back to sea to look for the French privateer Acheron, Captain Jack Aubrey is confident everything will go according to his plans. He is thrown for a loop by the First Plot Point. Instead of the Surprise finding the Acheron, the captain wakes to discover the enemy bearing down on his much smaller ship. Not only is his victory at risk but now he and his crew are in danger of being captured. They scramble to escape, and the game of cat-and-mouse that will comprise the rest of the film begins in earnest.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the First Plot PointThe First Plot Point occurs around the 25% mark.The First Plot Point is an event that changes everything and becomes a personal turning point for the main character.The First Plot Point almost always changes the story so irrevocably that even the character’s surroundings (either the physical setting or the cast of supporting characters) are altered.The First Plot Point is something to which the main character must be able to react strongly and irretrievably.The First Plot Point is one of the most exciting moments in any story. Choose a robust and cataclysmic event to which your characters must adamantly react. Hit readers so hard at the end of the First Act they won’t even think about closing the book.

Stay tuned: In two weeks, we’ll talk about the First Half of the Second Act.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What happens at your story’s First Plot Point? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The First Plot Point (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 5 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 5, 2024

The Inciting Event (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 4 of 12)

The Inciting Event is one of the most crucial turning points in story structure. It can either make or break your narrative. Many writers, however, struggle with its intricacies and timing. Is the Inciting Event the initial brush with the main conflict? Is it a Call to Adventure met with refusal? Where does it belong in the structure of your story, particularly within the context of the First Act? By analyzing examples from film and literature, we can unravel these complexities and learn to create an impactful Inciting Event.

The Inciting Event is one of the most crucial turning points in story structure. It can either make or break your narrative. Many writers, however, struggle with its intricacies and timing. Is the Inciting Event the initial brush with the main conflict? Is it a Call to Adventure met with refusal? Where does it belong in the structure of your story, particularly within the context of the First Act? By analyzing examples from film and literature, we can unravel these complexities and learn to create an impactful Inciting Event.

As the first major turning point in your story, the Inciting Event marks a transition from the setup in the first half of the First Act into the buildup in the second half, as the story begins to ramp into the characters’ full-on immersion in the conflict in the Second Act. As its name suggests, this is the event that “incites” or initiates the plot’s main conflict. Also sometimes referred to as the Inciting Incident, this all-important beat signals that this is what the story is all about.

Misconceptions About the Inciting Event (and the Key Event) For all that the Inciting Event is crucial to creating a functional plot, it is often misunderstood. My own understanding of the Inciting Event has evolved drastically over the years, and some of my own foggy ideas (as published in the first edition of Structuring Your Novel) have contributed to the confusion. I amended some of this when I offered my free e-book 5 Secrets of Story Structure as a supplement, but one of the main reasons I wanted to create an updated second edition of Structuring Your Novel, as well as updating this series, was to share a more accurate and useful approach to the Inciting Event.

For all that the Inciting Event is crucial to creating a functional plot, it is often misunderstood. My own understanding of the Inciting Event has evolved drastically over the years, and some of my own foggy ideas (as published in the first edition of Structuring Your Novel) have contributed to the confusion. I amended some of this when I offered my free e-book 5 Secrets of Story Structure as a supplement, but one of the main reasons I wanted to create an updated second edition of Structuring Your Novel, as well as updating this series, was to share a more accurate and useful approach to the Inciting Event.

The main thing that has changed about how I view the Inciting Event is that I no longer see its timing as vague. I originally taught that the Inciting Event could take place just about anywhere in or before the First Act. In that view, the Inciting Event might be an event in the character’s backstory that motivates the main plot. Or it might be the plot domino found in the first chapter. Or it might take place halfway through the First Act. Or it might coincide with the Door of No Return—the First Plot Point at the 25% mark.

This wobbly structural timing was based on a conflation of several different important motivating events within the plot’s timeline. When each of these events is given its own name, it becomes clear where the true Inciting Event really lands and what it actually is. Before we go deeper, let’s take a moment to properly identify each of these beats within the story.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Motivating event in the protagonist’s backstory: This is the Ghost (also sometimes called the wound), a term originated by John Truby, which I discuss in my book Creating Character Arcs. As something that happens before the story, it is not properly a part of the plot structure. Rather, it creates context for why characters believe a limiting Lie about themselves or their reality. This Lie will then be challenged by the events of the main plot and will create the characters’ inner journey via their character arcs.

First plot domino in first chapter: As we discussed in Part 2, this initiation of the story’s cause and effect is created by the Hook at the very beginning. This beat functions to set up the story world and the characterizations that will lead to the true Inciting Event a few chapters later.Turning point halfway through the First Act: Here we find the true home of the Inciting Event, which we will explore in the rest of the post.The Door of No Return at the end of the First Act: This beat is the First Plot Point. It is one of the three most prominent turning points in the entire story (along with the Second Plot Point or Midpoint at the 50% mark and the Third Plot Point at the 75% mark). In order for this beat to create a dramatic and irrevocable turn of events leading into the Second Act, it must be built upon a previous event that incites those events. We will explore the First Plot Point in next week’s post.

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

As we parse out the function and timing of these catalysts within the story, a clearer picture emerges of how the First Act operates. This picture also supports the pattern of timing and pacing that creates an important turning point every eighth of the story.

Some of you may notice I have not mentioned the Key Event in this lineup. In the first edition of Structuring Your Novel, I wrote:

The Key Event is the moment when the character becomes engaged by the Inciting Event…. The Key Event is the glue that sticks the character to the impetus of the Inciting Event.

Screenplay by Syd Field (affiliate link)

This was based on Syd Field’s teaching in Screenplay about the two beats:

[T]he inciting incident… sets the story in motion … [while] the key incident [is] what the story is about, and draws the main character into the story line.

At the time, I also believed in a flexible timeline for the Key Event, associating it more with the Inciting Event than any other beat. I now associate the Key Event with the First Plot Point. On the whole, I find it more straightforward to focus on the fixed beats of the Inciting Event and the First Plot Point.

I apologize for any confusion my own treatment of these terms has caused in the past. I hope this new information will clear up any perplexity.

What Is the Inciting Event?Now that we’ve explored what the Inciting Event isn’t, what exactly is it?

The Inciting Event is the turning point halfway through the First Act. Up to now, the First Act has mostly concerned itself with setup—with setting the stage, introducing the characters and their motivations, and indicating what is at stake for them. None of these introductions or the scenes they inhabit have been random. Each has been a domino knocking into the next, creating that flawless chain of cause and effect. However, up to this point, these scenes will not have particularly focused on what will become the main conflict in this story.

Although the protagonist will have a desire in the first half of the First Act, or at least a reason to desire something, this desire won’t yet have solidified into a solid plot goal.

For Example:

In The Hunger Games, Katniss starts out disliking the antagonistic Capitol and resisting them in small ways that ensure her family’s survival. She has yet to form the specific plot goal that will directly engage her with that antagonist. Therefore, the story’s main conflict has not yet begun. Rather, these early scenes lay the groundwork for that conflict.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

The Inciting Event is where the main conflict significantly intrudes upon the character’s life. I like to say the Inciting Event is where the protagonist “brushes” the main conflict. This contrasts the full-on immersion in that conflict, which the character will experience at the First Plot Point. The difference is one of degree. Even if the happenings at the Inciting Event are quite radical (e.g., Katniss volunteering as tribute to protect her little sister), they will not be as radical as what happens later at the First Plot Point (e.g., starting to train as a tribute).

The characters’ full engagement with the main conflict cannot happen until they form the main plot goal. That will happen at the First Plot Point and will signal the shift out of the First Act into the Second Act. The Inciting Event exists to set up the First Plot Point. Because the plot goal will not yet be fully formed, the character’s response to the Inciting Event will be uncalibrated and perhaps even uncertain. This “brush” with the antagonistic force knocks them off balance.

In the Hero’s Journey terminology, the Inciting Event carries the energy of what is known as the Call to Adventure. When we examine the archetypal underpinnings of story structure, we see that this is the moment when the characters are invited to step beyond a familiar comfort zone. They are challenged to push their growth edges, to step into a “wider world,” and to test their mettle.

Aptly, the forward momentum of the Call to Adventure will almost always be met with a Refusal of the Call, as the characters resist what their changing circumstances are now asking of them. In some stories, the protagonist will explicitly try to refuse the Call to Adventure by avoiding the consequences of the Inciting Event. In other stories (such as Hunger Games), the refusal may occur primarily within the protagonist, as represented by feelings of fear or inadequacy. In still other stories, the refusal may be represented by counsel or resistance offered by supporting characters who do not want the protagonist to engage with the main conflict by enacting a specific plot goal.

Where Does the Inciting Event Belong? The Inciting Event splits the First Act, taking place around the 12% mark in the story. This timing does not need to be exact. The shorter your story, the tighter your timing should be; the longer your story, the more wiggle room you will have. However, the significance of the Inciting Event’s timing is that it must allow enough space before to realistically set up whatever will happen at the Inciting Event, including what will motivate the characters to respond as they do. Most of the important elements need to be in place (or at least foreshadowed) by the time you reach the Inciting Event.

The Inciting Event splits the First Act, taking place around the 12% mark in the story. This timing does not need to be exact. The shorter your story, the tighter your timing should be; the longer your story, the more wiggle room you will have. However, the significance of the Inciting Event’s timing is that it must allow enough space before to realistically set up whatever will happen at the Inciting Event, including what will motivate the characters to respond as they do. Most of the important elements need to be in place (or at least foreshadowed) by the time you reach the Inciting Event.

The timing of your Inciting Event must also allow for the second half of the First Act to focus on scenes that develop your characters’ reactions to the Inciting Event. From here, the rest of the First Act will shift out of setting things up into building up to the First Plot Point. Structurally, the First Plot Point is a massive moment in your story and will almost always be represented by a suitably dramatic event. The second half of the First Act builds into that moment. Most importantly, this section of the story is where your characters will begin forming a concrete plot goal.

In stories in which the characters are more reactionary (i.e., are at the mercy of a much larger antagonistic force), their plot goal may not become concrete until the First Plot Point. In these stories, the focus in the second half of the First Act may be on increasing tension and raising the stakes so the characters have little choice but to engage by the time they reach the First Plot Point.

For Example:

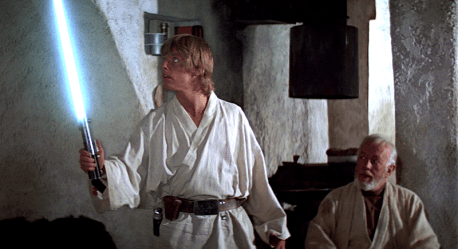

In Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke Skywalker’s Inciting Event introduces him to the opportunity of leaving Tatooine with Ben Kenobi—a Call to Adventure which he refuses—but when his aunt and uncle are murdered at the First Plot Point, he has no choice but to accompany Ben.

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

Other stories will feature a more proactive protagonist whose desire for the goal creates the conflict, rather than the conflict creating the goal.

For Example:

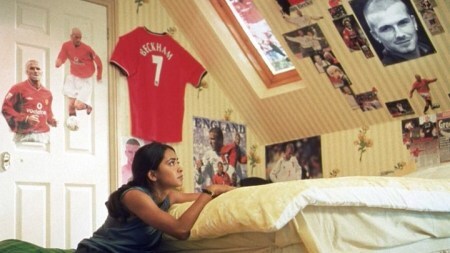

In Bend It Like Beckham, protagonist Jess joins the soccer team not because anything forces her, but because it is her dream. This puts her in conflict with her family, but she initiated the events. In stories like this, the protagonist often spends the scenes between the Inciting Event and the First Plot Point taking deliberate steps toward a full commitment to the plot goal.

Bend It Like Beckham (2002), Fox Searchlight Pictures.

In stories that feature particularly life-changing Inciting Events, such as The Hunger Games, the Inciting Event will still build up to the First Plot Point. Occasionally, in such stories, the First Plot Point will be less dramatic than the Inciting Event, but will still structurally function to fully engage the protagonist with the main plot goal.

For Example:

Even though Katniss’s dramatic Inciting Event forever changes her life, she does not fully engage with the main plot conflict of surviving the Hunger Games until she reaches the Capitol, where she begins training as a tribute.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

In most stories, the three major plot points (First Plot Point, Midpoint, Third Plot Point) will feature the story’s “biggest” scenes. It is important to remember that even in stories in which this is not true, the structural timing and the specific roles of each structural beat remain the same.

Examples of the Inciting Event From Film and LiteraturePride and Prejudice: Although Elizabeth and Darcy spar at the Meryton assembly dance, forming opinions of each other they will spend the rest of the story trying to overcome, the true Inciting Event is the scene in which Elizabeth becomes the Bingleys’ guest while her sister Jane is staying there as an invalid. This sequence “brushes” Elizabeth against the main plot conflict by initiating her relationship with Darcy. From here, their paths will become more and more intertwined.

Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.

It’s a Wonderful Life: This classic movie uses the entirety of its First Act to leisurely introduce and build its characters. Its gentle Inciting Event occurs on the night of the high school dance when George’s father asks him if he would be willing to stay in Bedford Falls to help run the Bailey Brothers Building & Loan. George promptly refuses his father’s request. This sets up the central throughline and George’s central conflict between his need to stay and help contrasted with his burning desire to leave Bedford Falls.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

Ender’s Game: The First Act frames the central conflict by introducing a world that has been under attack by the Formic aliens for over eighty years. The protagonist, young Ender, is not directly impacted by this larger conflict until the Inciting Event when Col. Graff and the International Fleet Selective Service recruit him. He is taken to Battle School, where he will be trained to outwit and outfight the aliens.

Ender’s Game (2013), Lionsgate.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World: This film’s structure is interesting in that the Inciting Event sequence takes up almost the entirety of the first eighth of the movie. This sequence of scenes features the sneak attack by the enemy ship Acheron upon the protagonist’s ship, HMS Surprise. After this attack, around the 12% mark, the protagonist must repair the ship and decide how to respond.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003), Miramax Films.

Top Things to Remember About the Inciting EventThe Inciting Event takes place halfway through the First Act, around the 12% mark.The Inciting Event is the moment when the protagonist “brushes” into the main conflict, antagonist, or goal in a way that requires a response.The Inciting Event lays the foundation for the protagonist’s subsequent full-on engagement with the main conflict.The Inciting Event is a Call to Adventure, challenging the character to either rise up in resistance against something or move proactively toward a desire.This Call to Adventure is initially refused, perhaps internally or perhaps by a proxy character, as the protagonist faces the weight of what is at stake in engaging with the conflict.The Inciting Event signals the end of the First Act’s “set up” and the beginning of the “build up” toward the Second Act.A solid Inciting Event creates the foundation for your entire story. Don’t settle for anything less than the most powerful and memorable scene you can come up with. Time it strategically within the First Act and use it to engage your readers just as irretrievably as it does your main character.

Stay tuned: Next week, we’ll talk about the First Plot Point.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify the Inciting Event in your work-in-progress? Tell me in the comments!Related Posts:

Part 1: 5 Reasons Story Structure Is Important

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Inciting Event (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 4 of 12) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 29, 2024

The First Act (Secrets of Story Structure, Pt. 3 of 12)

The First Act is the first major section within story structure. It comprises the first quarter of the story and focuses primarily on setting up and introducing the plot. As the foundation for everything, a solid First Act ensures your plot can achieve solidity and depth in subsequent acts.

The First Act is the first major section within story structure. It comprises the first quarter of the story and focuses primarily on setting up and introducing the plot. As the foundation for everything, a solid First Act ensures your plot can achieve solidity and depth in subsequent acts.

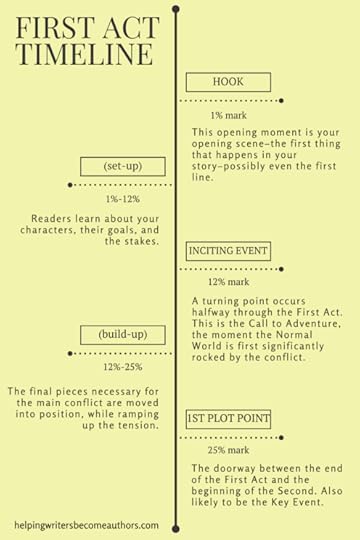

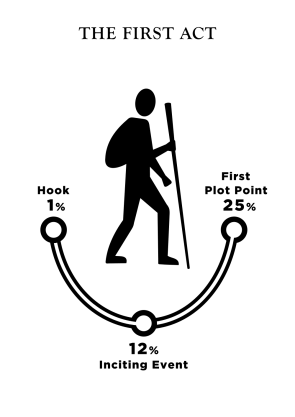

Within the First Act, we find three important structural beats:

The Hook – 1%The Inciting Event – 12%The First Plot Point – 25%

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

The Hook, which we discussed in last week’s post, begins the story by introducing the first domino in the row of causality that will allow each scene to lead into the next. At that point, the protagonist will likely not yet be engaged in the main conflict. What happens at the Hook begins to set up the conflict, providing the first bit of foreshadowing and context.

The Inciting Event, which we will discuss next week, divides the First Act in half, providing the story’s first important turning point. It symbolically represents the Call to Adventure and invites the protagonist to engage with the primary conflict.

The Inciting Event, which we will discuss next week, divides the First Act in half, providing the story’s first important turning point. It symbolically represents the Call to Adventure and invites the protagonist to engage with the primary conflict.

The First Plot Point does not discretely belong in either the First Act or the Second Act. Instead, it creates the “threshold” or Doorway of No Return between the Normal World of the First Act and the Adventure World of the Second Act. The First Plot Point is when your protagonist becomes fully engaged with the primary conflict. From here, the protagonist will not be able to turn back from the pursuit of the goal without consequences. We will discuss this all-important beat in more depth in a few weeks.

From this brief overview, you can see that the primary focus of the First Act is not the immersion of the protagonist in the story’s main conflict. Rather, the First Act is where the story develops the reasons the character will choose to engage with the antagonistic force later on. The story will go full-on in the Second Act. For that intensity to make sense, the First Act needs to provide context for what follows. You can think of the First Act as foreshadowing for the Second and Third Acts. It is the plant to the subsequent payoffs.

Setting Up the Story: Characters, Settings, and Stakes After hooking readers, your main task in the First Act is to put your early chapters to work introducing your characters, settings, and stakes. Twenty-five percent of your book might seem a tremendous chunk of the story to devote to introductions. But if you expect readers to stick with you throughout the story, you must give them a reason to care. Mere curiosity can only carry readers so far. Once you’ve hooked their sense of curiosity, you must then deepen the pull by creating an emotional connection between them and your characters.

After hooking readers, your main task in the First Act is to put your early chapters to work introducing your characters, settings, and stakes. Twenty-five percent of your book might seem a tremendous chunk of the story to devote to introductions. But if you expect readers to stick with you throughout the story, you must give them a reason to care. Mere curiosity can only carry readers so far. Once you’ve hooked their sense of curiosity, you must then deepen the pull by creating an emotional connection between them and your characters.

These “introductions” include far more than the moment of introducing the characters and settings or explaining the stakes. In themselves, the presentations of all the important characters probably won’t take more than a few scenes. After the actual introductions is when your task of deepening the characters and establishing the stakes really begins.

In one sense, the First Act is like a program for a play. Its primary purpose is to prepare readers for what’s in store. You’re using these early chapters to indicate which characters are important, what type of story readers can expect, and where the journey will take them.

The first quarter of the book is where you compile the necessary components for your story. Anton Chekhov’s famous advice that “if in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired” is just as pertinent in reverse: if a character fires a gun later in the book, that gun should be foreshadowed in the First Act. The story you create in the following acts can only be assembled from the parts you’ve shown or foreshadowed in the First Act.

Introducing Your Story’s CharactersYour first duty in the First Act is to allow readers the opportunity to learn about your characters. Who are these people? What is the essence of their personalities? What core beliefs will be challenged or strengthened throughout the book? If you introduced someone in a Characteristic Moment, as discussed last week, then you were already able to show readers who this person is. From there, the plot can build as you deepen the stakes and set up the conflict that will explode halfway through the First Act in the Inciting Event and later at the First Plot Point.

Every story spreads out the arrival of important cast members differently. Usually, prominent actors should all be on stage by the time the bell rings at the end of the First Act. You can find exceptions in which prominent characters don’t arrive until late in the story (e.g., Cynthia in Wives and Daughters), but these late arrivals must be well planned. An arbitrary new character is never a good idea.

Wives & Daughters (1999), BBC/WGBH Boston.

Try to introduce all the following players within the First Act:

ProtagonistIntroduce the protagonist as quickly as you can, in the first scene if possible (and it should almost always be possible). The early introduction of the main character signals to readers this is the person whose story they’re reading and therefore this is the person to whom they need to attach loyalty.

AntagonistYou’ll usually introduce or at least foreshadow the antagonist early on, both to get the conflict rolling and to foreshadow the opposition to whatever your character cares about.

Love InterestParticularly if your story is a romance, but even if the love story is only a subplot, you will most likely bring your protagonist’s love interest on stage in the First Act. Although you don’t have to signal these two people will end up in love, you can at least signify the character’s importance with an early introduction.

SidekickMinor characters come and go in a story. Some will be important, some won’t. Those who will be at your protagonist’s side for the majority of the book deserve at least a short intro sometime before the First Plot Point.

Mentor

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

Mentor characters (which may or may not be Mentor archetypes) can enter a story just about anywhere in the first two acts, depending on their importance and the size of their roles. When possible, avoid convenient plot twists later on by introducing, or at least foreshadowing, a mentor character’s existence in the First Act.

Introducing Your Story’s StakesAs your characters walk onto the stage, they will bring the stakes along with them. What they care about—and the antagonistic forces that threaten what they care about—must be shown or hinted at to foreshadow the deepening conflict of the Second Act.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)