Oxford University Press's Blog, page 565

January 4, 2016

The art of conversation

On 28 November 2015, I had a reading and panel discussion at Médiathèque André Malraux, a library and media centre in Strasbourg, the main city of the Alsace region of France, adjoining Germany, traditionally one of the Christmas capitals of the continent, and currently the site of the European Parliament. As I was told that my hotel was just a 20 minute walk from Médiathèque André Malraux – refreshed and armed with a map – I declined the transport offered and decided to walk to the venue. It had been raining earlier, but now cotton-wool wisps of cloud floated in a washed blue sky. The sun was out again. As I strolled, I couldn’t help noticing that there were fewer pedestrians and cyclists than I recalled from earlier visits to other French towns. This surprised me, because towns in France – or Spain or Italy – have a more vibrant culture of going out than in the North, where I have lived for close to two decades now.

After my event, my French publisher and the two hosts took me out to dinner in a Tunisian restaurant. As we walked to the restaurant, the earlier feeling came back to me – there were too few people on the streets. It looked more like a town in northern Europe than in southern Europe. Was it because Strasbourg is on the northern side of France? I put the question to my hosts, even though I suspected I knew the answer. No, my hosts replied, confirming my suspicion, it is because of the ISIS-attacks in Paris. People are not eating out or going out in the evenings as often as they were, I was told. Some are afraid; many are merely sad.

2012-03-17 Strasbourg 073 by Detlef Krause. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

2012-03-17 Strasbourg 073 by Detlef Krause. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.We walked on to the Tunisian restaurant, where my hosts were known and the Tunisian waiters kept coming to our table to say hello. Half the tables of the small restaurant were occupied. When we left two hours later, I saw a long table on one side of the restaurant that seemed to contain at least three generations – maybe four – of a French family. There was a bearded grandfather, who bore a striking resemblance to a white-haired Karl Marx, at one end, teenagers at another end, and family members of various ages in between. They were engrossed in conversation, as were my hosts and publishers, now taking their time bidding goodbye to the owner/cook and two waiters.

* * *

When I was younger, I read Amartya Sen’s The Argumentative Indian with a large degree of agreement. I still believe in the need for the articulation and acceptance of difference that the book championed. And yet, with the years, I have come to wonder if the only paradigm available to us is that of the argument, with its possibility of a negotiated settlement that is, at best, a tactical compromise on all sides. How about another paradigm? How about the paradigm of the conversation?

The argument, and any negotiated agreement that it may lead to, is based on a resistance to the other. The conversation, on the other hand, suggests openness to the other. In a conversation, you need not agree, but you have agreed not to argue in such a way that the conversation breaks. You have agreed to step into the other person’s shoes, and the other person has agreed to step into yours. A degree of civility is presumed in the conversation. The agreement you reach at the end of a conversation is neither tactical, nor begrudging. It enfolds all the parties equally: the conversation goes on. As the great 19th century Delhi poet, Ghalib put it in a lighter, amorous context, “Har ek baat par kahte ho tum ki tu kya hai / Tumhi kaho yeh andaaz-e-guftagu kya hai.” [On every issue you say, ‘You’re nothing in my estimation,’ / Tell me truly, is this a style of conversation?] What he suggests is that even in a domestic or amorous setting, the dismissive argument – ‘tu kya hai’ – impedes any true conversation.

What the ISIS terrorists did in Paris – what Islamic fundamentalists do every day when they insist on their particular interpretation of Islam – is deny the possibility of conversation. Many Hindutva supporters do something similar, as do some extreme leftists. Perhaps the very nature of the Internet impedes the art of conversation too. A conversation assumes a setting, the civility of sitting down and listening, waiting for your turn to speak, or considering the other person’s position and not dismissing it outright (tu kya hai), maintaining a civil space of free enunciation, no matter what the differences. The Internet with its isolated networking makes it easier to argue than to converse because the civil space demanded for conversation is not fully available when you face only a computer screen. I think we are losing the art of conversation, an art that was never too fully developed in some societies in any case. Apolitical as this may sound, one of the solutions to many of our political problems is exactly this – we need to cultivate the art of conversation, domestically, locally, regionally, nationally, and globally.

I increasingly see conversation as the backbone of civilisation. I use civilisation in a large sense: many hunting-gathering tribes, for instance, had elaborate rituals of conversation. The ‘pow-wow’ of Indian American tribes is the one that has seeped – in caricatured form – into popular global culture, but there were similar traditions among the Santhals in India, the Maoris in New Zealand, the Australian aborigines, and many other peoples. These traditions were spatially and temporally limited: they usually frayed when faced with rapid change across time or a totally different cultural context.

But there are more culturally complex examples too. It is customary – and not incorrect – to consider a degree of bullying and xenophobia to be at the core of all modern nations. And yet, one can argue that the extent to which a nation succeeds depends on its ability to cultivate and sustain a national conversation – across tribal, ethnic, linguistic and other divides. This, inevitably, cannot be done on the basis on the bullying of one or more dominant segment of the nation. What one needs is not an argument about beef, pork, chicken, and cabbage, but a conversation – in which everyone can speak freely and with consideration. The conversation is always a public unitary act which works only when personal differences are fully accepted. I would argue that many European nations have managed to do this better than almost all Third World countries, and even frayed rich nations like the United States. Europe has managed something else at a larger level. At its best, despite the xenophobes, Europe has created space for a larger European conversation. European Christian sects do not fight each other despite major doctrinal differences – a process that is the result of a tentative conversation first attempted, after centuries of conflict, in the 17th century. Similarly, European nations – after the Second World War – have managed not only to avoid fighting one another but also to avoid arguing in ways that lead to the end of the conversation.

* * *

Later that night, as I left my hotel room for a stroll around the centre of Strasbourg, I thought of this. Some cafes were still open. I could see couples or groups, sitting over their glasses and plates, talking. I thought of other places in the world where this is not possible – or at least subject to greater pressures. I was sure there would not be similar groups in Syria or Iraq. I doubt that a real conversation could take place even in places like Saudi Arabia and Iran, for only some things can be said there. I even thought of places in India or Bangladesh where some conversations could be easily frayed and dissolve into shouting. I thought of the Internet, with its legions of abusive trolls.

I was grateful to this space of Strasbourg where conversation was still possible. Conversation depends on civility, not capital or power, and it is from civility that any civilisation grows. The personal act of conversation – a free, courteous exchange – is the most politically enabling action you can perform or demand.

This is something that fundamentalists of all ilk cannot see. They are deafened by their anger, hatred, conviction, ideology, book. They can only shout, not even really talk, because they are afraid to listen. They cannot converse, and they do not want us to converse. Light a candle against this trend now. Shut your laptop, go to a café or dhabba with friends, address a friendly stranger, listen, talk, listen. Learn to have a family dinner – as the French very often do even today – without the TV on. Don’t let arguments end your conversations: say, with Ghalib, in that case, ‘Tumhi kaho yeh andaaz-e-guftagu kya hai?’

We will be saved not by our arguments but by our conversations.

Featured image credit: “Strasbourg – la nuit” by dhodho.net. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The art of conversation appeared first on OUPblog.

The world’s most (in)famous exoplanet vanishes

In 2012, a team of astrophysicists led by Xavier Dumusque caused a sensation when they announced the discovery of Alpha Centauri Bb: an Earth-sized planet in the Alpha Centauri star system, the star system closest to the Sun. If verified, Alpha Centauri Bb would be the closest known exoplanet to our own Solar System, and possibly also the lowest mass planet ever discovered around a star similar to the Sun.

Media coverage of this “landmark” discovery was widespread and ebullient. Popular astronomy writer Phil Plait exclaimed: “Huge news…Holy crap! A planet for Alpha Cen[tauri]. Wow.” I certainly shared Plait’s enthusiasm. Another author referred to the planet, 4.3 light years away, as being “almost close enough to touch.” Many even spoke of the possibility of sending an unmanned probe to the newly discovered exoplanet.

Fast forward to 2015, though, and there’s a catch: Alpha Cen Bb no longer seems to exist.

Where’d it go? Our recent analysis of the original data suggests the planet was never there in the first place, and was instead an unfortunate by-product of the way the observations were made.

To understand how such problems can arise, it’s worth considering just how difficult it is to detect a planetary signal similar to the one initially claimed by Dumusque’s team.

Alpha Cen B, the “Sun” around which the claimed planet orbits, is 4.37 light years from Earth: by astronomical standards, that’s really close — yet it’s still more than 40 trillion kilometres away. With current technology, an unmanned space probe would take tens or even hundreds of thousands of years to make the journey. Driving there, if that were possible, would take longer than the known Universe has been around!

To infer the presence of a planet orbiting Alpha Cen B, Dumusque’s team used the radial velocity method to look for characteristic, periodic changes in the star’s motion (“wobbles”) caused by the gravitational tug of an orbiting planet. The size of the wobbles they ascribed to Alpha Cen Bb? About 50 centimetres per second, repeating every 3.24 days. It’s a remarkable testament to modern instrumentation and analytical techniques that we do have the capability of detecting such tiny wobbles from stars trillions of kilometres away.

As it turns out, though, an orbiting planet is hardly the only thing that can cause such apparent wobbles; other sources of variability include magnetic activity internal to the star itself, the gravitational pull of companion stars, instrumental noise, and more. The effects of these ‘nuisance’ signals can often be hundreds of times greater than the effects of hypothetical exoplanets. So Dumusque’s team had to work really hard to try to model and remove all nuisance signals, to isolate the tiny signal eventually ascribed to a planet. Indeed, this prompted much initial scepticism about their claimed planet.

Where’d it go? Our recent analysis of the original data suggests the planet was never there in the first place, and was instead an unfortunate by-product of the way the observations were made

But the modelling of the nuisance signals wasn’t the problem: our recent re-analysis of the data led us to much the same conclusions about the properties of the nuisance signals, even though we used very different techniques to Dumusque’s team. Instead, the source of the problem appears to be the times the observations were made.

It’s a rather contrived analogy, but imagine you’re trying to listen to a distant orchestra playing a tune, and for some reason, you’re only able to listen to the occasional note. If you’re lucky, you might hear a few very distinctive notes, and correctly identify the tune being played. If you’re unlucky, the same few notes might happen to match a few different tunes, and you could be led to the wrong conclusion. You might even mistake the noise of passing traffic for a real tune! On the other hand, if you could’ve listened to far more notes, and perhaps without having to contend with lots of noise, you’d likely have had no trouble identifying the tune. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Illustration of how the sporadic observation of a signal can lead it to being mistaken for a signal with a different period. Here, the blue signal is aperiodic, while the red signal contains patterns that repeat every 3.24 days. Image by Vinesh Rajpaul

Figure 1: Illustration of how the sporadic observation of a signal can lead it to being mistaken for a signal with a different period. Here, the blue signal is aperiodic, while the red signal contains patterns that repeat every 3.24 days. Image by Vinesh RajpaulIt was much the same with the Alpha Cen B data: Dumusque’s team could only observe Alpha Cen B on clear nights, using a ground-based telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile, and only when this telescope wasn’t booked for other observations.

To demonstrate that the discrete observing times were the source of the bogus signal, we used computer simulations to create a fake star, with properties very similar to Alpha Cen B — including binary companion star, Alpha Cen A — but which, by careful design, had no planets around it. Whenever we ‘observed’ such a fake star at the same time as the real observations, we reliably identified a 50 cm/s signal with 3.24 d period — identical to the planetary signal claimed by Dumusque’s team. Thus we concluded that this signal was a mere “ghost” arising from the nature of the observations themselves, rather than from any real planet.

More observations are probably necessary to rule out Alpha Cen Bb’s existence with 100% certainty, but our analysis does make it seem very, very unlikely that the planet is real.

Our work has relevance to future efforts to detect exoplanets (can we choose our observing times more carefully to avoid such bogus signals from arising? if not, which tests can we run to help identify potential problems?), and also to archival data (are any other supposed exoplanets really just artefacts?)

Yet it’s not all doom and gloom. Based on current confirmed detections of exoplanets, we estimate conservatively that there is at least one exoplanet for every star in our galaxy — that’s a minimum of hundreds of billion exoplanets in our galaxy alone, and the real number might be much higher! Don’t book your interstellar flight just yet, but it’s probably safe to say that it’d be weird if there were not any planets in the Alpha Centauri system.

PS: despite some conspiracy theories to the contrary, I was not paid by aliens from Alpha Cen Bb to cover up their planet’s existence.

Feature image credit: “Artist’s impression of the planet around Alpha Centauri B.” By ESO/L. Calçada/N. Risinger CC BY 4.0 via European Southern Observatory.

The post The world’s most (in)famous exoplanet vanishes appeared first on OUPblog.

Repentance and the Bible: A Q&A with David Lambert

Many people assume that repentance is and always has been a substantial part of the Bible, but that has not always been the case. In the following interview between Luke Drake, a doctoral student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and David Lambert, an assistant professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture, the two discuss how repentance came to be seen as a part of the Bible, and the early history of repentance as a concept.

How did you first decide to write about repentance?

For a long time, I had been interested in the kinds of narratives that we tell about our lives. We often see ourselves as experiencing not just developmental growth, from childhood to adulthood, but also spiritual or moral progress. What surprised me as a historian was that, despite its importance to us today, this sense of personal development—individual biography—was not always obvious in Judaism and Christianity, especially in their earliest formulations. One important exception seemed to be the concept of repentance, so I set out to study it.

And, what did you find?

Well, actually, what I found was that repentance didn’t really appear in all of the places that I expected. I noticed this first with regard to fasting in Hebrew Bible. People fasted for all different kinds of reasons, including mourning the dead. Fasting was especially common in contexts of prayer, often without any connection to sin. But, for many of us today, fasting is all about atonement and feeling sorrow for sins. I also came to realize that the biblical, prophetic phrase—’return to the Lord’—which we have come to associate with repentance and from which the Rabbis claimed to derive their notion of repentance, teshuva, had little to do with repentance in its original context.

The New Testament sources also appear to differ in striking ways over the role of repentance. There seems to be some disagreement: did Jesus preach repentance or not? Finally, I found it significant that, in the Bible, Adam and Eve never bother to repent as a way of dealing with their sin, and Noah never warns his generation about the Flood. But, Jewish and Christian readers of the Bible, from around the turn of the Common Era, made a concerted effort to read repentance into these narratives and many others. All of these discrepancies clearly pointed to the fact that something important was going on!

It seems like a big part of your claim is that we read repentance into the Bible, a tendency you label ‘the penitential lens’. Could you tell us more about how this ‘lens’ works?

Sure. The first thing to realize is that the importance of repentance as a concept within Judaism and Christianity means that scholars of the Bible, from ancient to modern times, are predisposed to seeing repentance as biblical. The Bible, after all, is often assumed to be a source of our values. And there is remarkable agreement, even among contemporary academics, that phenomena such as fasting, prayer, confession, and prophecy all involve repentance in some way, even though repentance as a concept is never mentioned.

Image credit: Jonah Preaches to the Ninevites by Gustave Dorѐ. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Jonah Preaches to the Ninevites by Gustave Dorѐ. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Even more interesting, however, are the particular strategies we use for reading repentance into the Bible. So, for instance, you have a commandment that the Israelites fast and afflict themselves on the day that the high priest cleanses the Temple—the Day of Atonement. Our impulse is to assume that such bodily performances are significant in so far as they express inner feelings of sorrow, which the text, in fact, shows no interest in depicting. Or, again, we’ll read some utterance of the prophet, Amos, declaring that Israel is doomed because of its sin and say to ourselves that there must be some deeper purpose behind the prophet’s words: he must really be trying to get Israel to repent and save themselves.

In both cases, we’re convinced that a good reading of the passages demands that we look beyond the actual words of the text. But why do we do this? Really, it has more to do with our contemporary notions of the self than with the Bible. We tend to think of ourselves as having a split between mind and body, with the mind (or ‘soul’, or ‘heart’, or ‘self’, or whatever you want to call it) being our dominant and most essential component. So when we analyze human behavior, we tend to look past it and see it as a way of expressing what really matters, namely what is ‘inside’. We also tend to view religion as deeply concerned with moral and spiritual improvement, so we assume that the prophets’ words must be aiming at this greater good even if nothing in their language or context suggests so.

If biblical practices such as fasting and confession were not about repentance, what were they about?

I mentioned earlier the connection between fasting and prayer. If you were King David, say, and wanted to save your condemned son, you had a fundamental problem. God responds to the needy. But, you’re a powerful king! For David to have any hope of God responding to his appeal, he needs to become like someone who is afflicted. To do so he descends from his throne, removes his royal robes, and fasts. Fasting is not about self-expression but is a ritual means of changing your very identity or status as a person: you’re someone on the brink of death. Or, again, when you approach someone and declare, ‘I have sinned against you‘, the aim of your utterance is not so much to express sorrow, which is completely absent in the standard confessional formula, but to declare that you exist in a state of culpability vis-à-vis the person against whom you have sinned—you are at their mercy. This move sets up the possibility for forgiveness through repayment or other forms of reconciliation.

So when does repentance first start to appear?

Repentance has some antecedents in the Hebrew Bible, but it only comes into its own as a product of the Hellenistic period, when Jews lived under Greek and then Roman rule. For instance, as a technique for self-improvement, repentance or metanoia, in Greek, was particularly important to the forms of Platonism represented in the writings of Philo and Plutarch. However, the important point here is less a question of the origins of repentance but how and why it became such a pervasive, basic component of both Judaism and Christianity, each of which promote the power of repentance and incorporate it into their lexicon of religious terminology. So much more can be said, but the basic point was that you could enter a group through a mental act rejecting your past life and remain within it, even after possible sin, through the same. And so an idea was put forward, one that remains to this day, that a real transformation in identity is possible—that ‘repentance’ exists—and that it can be used as a powerful tool for self-governance, our selves monitoring and reprimanding our own selves.

The post Repentance and the Bible: A Q&A with David Lambert appeared first on OUPblog.

January 3, 2016

The problems with democracy – continuing the conversation into a new year

An invitation from the British Library to give the first in a new public lecture series called “Enduring Ideas” was never a request I was going to decline. But what “enduring idea” might I focus on and what exactly would I want to say that had not already been said about an important idea that warranted such reflection? The selected concept was “democracy” and the argument sought to set out and unravel a set of problems that could – either collectively or individually – be taken to explain the apparent rise in democratic disaffection.

Such is the world we live in that a lecture is no longer a lecture but rapidly becomes a multi-media “artefact” and the beginning of a global discussion. I suppose this is probably not quite true of all lectures, I’ve been to quite a few that really do need to be forgotten, but I’m pleased to say that the intellectual ecosystem seems to have exploded in all sorts of ways that I could never have imagined. Within hours the lecture was available to a global audience via a British Library podcast. Within weeks the lecture was published on-line by the Oxford University Press journal Parliamentary Affairs and within a month or so the same journal had published a number of response pieces by an array of leading scholars.

I had not given a public lecture at the British Library, I had started a conversation.

It was therefore a source of some delight and contentment when the latest instalment of this conversation appeared on-line in the form of a University of Manchester blog by a former student of mine, Dr. Kevin Gillan. Now some scholars might snort and snuffle at the idea of a former student seeking to challenge his former professor in such an open and accessible arena but I say ‘well done, that chap!’ Kevin was always a bit of a livewire but the way he tries to turn my arguments and ideas upside-down and inside-out, to get to the basic core of my logic in both an empirical and normative sense, is really a joy to read.

To my relief, Gillan’s approach is less concerned with sharpening the knife with which he seeks to butcher my argument but, to the contrary, is concerned with sharpening my argument by bringing in inter-disciplinary insights from the sphere of critical social movement studies.

The problem with my “problems with democracy” from Gillan’s perspective is that my analytical lens is too narrow. I stand-up and decry the loss of “what we might call our democratic or political imagination…our capacity to re-imagine a different way of living; to re-connect with those around us; to re-interpret challenges as opportunities or to re-define how we understand and make democracy work” [italics in the original] but for Gillan this argument reflects my own failure to look beyond the standard framework. “The political imagination is already being exercised outside of the mainstream,” he argues, “developments in the alter-globalisation and social forum movements and, latterly, among the indignadas of Spain and the occupiers of the public squares across Europe and the US.”

With this basic argument in place Gillan proceeds to highlight three issues – representation, institutional change and the internet – that add extra tone and texture to the problems I identify in my original lecture, podcast, article, T-shirt, etc.

It is true that the concept of representation is hardly mentioned in my original lecture but it is, as Gillan suggests, “squarely in the sights of those for whom some form of direct democracy…is part of their activism.” The interesting reflection here, however, lies not in simply focusing attention on the concept of representation itself but in relating this to my original critique of market-driven individualisation and its corrosive impact of collective social values. And yet Gillan reveals the existence of a parallel paradox in the sense that many of the contemporary critical social movements have their ideological roots in anarchism, although for many protestors this may be a less relevant grounding for the fact that, for them, it fits with a deeply held respect for the individual as sovereign bearer of rights. This is a line of argument that chimes with William Gairdner’s position in The Trouble with Democracy (2001) but if anarchist-inspired values and practices have really ‘overtaken revolutionary socialist ones in influence in most of today’s critical social movements’, then The Trouble with Representation qua. Gillan is that a large proportion of the ‘new’ politics beyond the mainstream is imbued with its own form of individualism that grates against the logic of democratic collective action.

The issue of institutional change posits and equally thorny problem as Gillan paints a picture of an increasingly labyrinthine institutional architecture in which functions and responsibilities are spread across many governing levels and within many types of organisation. The topography of this terrain is undeniably dense. In Walking Without Order (Oxford University Press, 2008) I attempted to map this territory but the structures are so fuzzy and fluid that I achieved little more than a rough sketch of the terrain. In light of this the public’s shift away from mainstream politics and political parties to a form of issue-based activism can be seen as completely rational. The problem, if one exists, lies not with the public in Gillan’s analysis but in the failure of the dominant institutional structure of representative democracy to keep pace with social and economic shifts. “So the dominant institutional structure of representative democracy, with its blend of representation-via-geography with representation-via-political-tribe is inherently unappealing for the denizen of the liquid modern: for many it is not education that is required [my main prescription for the democratic malaise] but institutional change.”

I cannot help but think of Michel Maffesoli’s wonderful The Time of the Tribes (1996) and especially his systematic theorisation of “everyday politics” by interpreting emergent forms of participation as what he terms “neo-tribes.” The tribal metaphor of “new-tribes” or “post-tribal politics” resonates with much of what Gillan seems to be arguing and Maffesoli’s focus on forms of political power (what he terms “puissance” or “intrinsic” power) and political legitimacy (what he terms “underground centrality” or “bottom-up” legitimacy) provides a fresh and innovative way of interpreting both “alternative” and “mainstream” forms of engagement. But then the shadow of individualism emerges once more in Gillan’s reflection:

But outside of mainstream political channels the activist autodidacts have already recognised that the ‘young and poor’ are hardly a homogenous group, even if they share the objective conditions of precarity. Perhaps they also recognise that even if there were an effective party of the precarious, the very one-dimensionality that would make it appealing to the young and the poor, would be the feature that made it problematic in relation to a whole gamut of other policy domains.

Which brings us to Gillan’s focus on the internet as a way not of overcoming individualism or issue-based politics but of embracing them and turning the deliberation they encourage to the service of the (inherently collective) polity. And he is certainly correct that in Defending Politics (Oxford University Press, 2010) I did dismiss ‘digital democracy’ with great polemical force. While I rage against ‘echo chambers’ and ‘cyber-citizens’ Gillan draws upon Jeffrey Juris and Manuel Castells to paint a quite different account of the internet revealing shared interests and common bonds. On-line movements have from this position ‘begun to re-imagine different ways of living, to re-connect with those around them and to re-define how they make democracy work’. In essence, Gillan believes that critical social movements are forging new forms of on-line mass mobilisation with the capacity to transform democratic politics.

So where does the conversation go from here? How would I respond to former student’s elegant essay? Where are the points of overlap and contestation and why might they matter?

Put very simply, I think a large intellectual and normative gap exists between me and Kevin Gillan that might in some ways reflect the gap that seems to have emerged between the governors and the governed. This is a gap I am happy to try and close or bridge through further conversations and possibly collaborations but there is something of “the politics of pessimism” that lurks beneath the words and between the sentences of his reflections. My thoughts on this topic remain embryonic but they seem to revolve around the themes of individuality, pace and people. Individuality in the sense that Gillan’s analysis appears to accept individualism as, irrespective of its intellectual roots, inevitable whereas my sense is that there is a shared collective sense of being human, a natural desire for social bonds beyond the immediate family and an innate amount of empathy that cuts across social classes, countries and religions. The inevitability of fragmentation within Gillan’s proposition is underlined by his comments on the ‘activist autodidactics’ who recognise that the young and the poor are by no means a homogenous group. Their shared objective conditions of precarity – the lack of permanent employment, low wages, constant re-skilling, frequent relocation, etc. – might form the basis of a new political party – “The Precarious Party” – but for some reason “the one-dimensionality that made it appealing to the young and the poor” would also be the feature that made it “problematic in relation to a whole gamut of other policy domains.” But why? Gillan defends the individualised issue-based activist on the basis that this does not mean they fail to take account of the way that focus overlaps with a range of broader issues so why would the Precarious Party not achieve a similar balance of breadth and depth?

In relation to pace Gillan agrees with my original statement that “our institutions and processes of democracy seem to evolve and change at a glacial pace while the world around it seems to move at an ever increasing pace” but then makes an argument that promotes the hyper-fast low-cost capacities of networked communications: “It is precisely the networked nature of movements that have sprung up across the world since 2011 that mean individuals can recognise…the commonality of their bonds.” But then this “politics of optimism” is dashed upon the Procrustean reality of life as he notes, “These movements remain relatively marginal in liberal democracies and have had limited impact on mainstream political thinking.” Pace…, pace…, pace… democratic politics may well be “the strong and slow boring of hard boards” but surely something has to pick-up the pace when it comes to democratic change which brings me to “the people,” social interaction and the internet. Gillan suggests that “for a very large number of (especially young) people in the advanced liberal democracies the online and the offline are now so thoroughly inter-twined that pretty much the whole human experience is reflected in, and partially lived through, online networks.” That may well be true (I am not so sure) but that does not make it a “good thing.” Or, more precisely, it appears that the blurring Gillan refers to manifests itself in the adoption of a set of expectations that are derived from on-line behaviour but are increasingly projected into off-line relationships. News in 140 characters, immediate location-based dating, real-time live gambling, virtual reality and lives lived through avatars. Technology-mediated-citizenship does little to fire my political imagination.

Featured image: “Parliament” by David Martyn Hunt, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The problems with democracy – continuing the conversation into a new year appeared first on OUPblog.

The rich and the poor in Shakespeare

George Bernard Shaw considered himself a socialist, but was apt to make surprising remarks about the poor. “Hamlet’s experiences simply could not have happened to a plumber,” he wrote in the preface to his play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets in 1910, and “A poor man is useful on the stage only as a blind man is: to excite sympathy.” Shaw’s Aristotelian ideas became increasingly unfashionable in early-twentieth century Western theatre and before his death in 1950 a new kind of tragedy of the working man emerged with Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. Bertolt Brecht embraced Shaw’s ideas when he first read them–while serving as dramaturg on the Berlin production of Shaw’s Saint Joan in 1924–and in particular he admired Shaw’s appeal to the reasoning faculties of his audiences rather than their emotions. Brecht came to believe that the best way to keep the audience thinking rather than empathizing would be to abandon Shavian realism and surprise his audience with unexpected violations of the conventions of drama. He found that Shakespeare had got there first: “Richard III Act V scene 3 shows two camps with the tents of Richard and Richmond and in between these a ghost appearing in a dream to the two men, visible and audible to each of them and addressing itself to both. A theatre full of Alienation effects!” (The Messingkauf Dialogues). For Brecht, revolutionizing the means of dramatic storytelling became more important than the kinds of people–rich or poor–that the stories were about.

Shaw always looked down upon the poor as an oppressed mass who could not be relied upon to save themselves, being too “dirty, drunken, foul-mouthed, ignorant, gluttonous, [and] prejudiced” (Dark Lady, Preface) to put the world to right. The conditions in which the poor live make them the way they are, he thought, trapping them in physical and mental squalor. Generally, socialists are rather more optimistic about the poor than that, and instead of focussing on what a lack of money has turned the poor into they focus on the perplexing properties of money itself that make this possible. Karl Marx, no stranger to poverty himself, found money to be all the more thoroughly paradoxical the more he thought about it. “That which I am unable to do as a man, and of which therefore all my individual essential powers are incapable, I am able to do by means of money,” wrote Marx, and “Money thus turns each of these powers into something which in itself it is not–turns it, that is, into its contrary” (“Money” in Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts III: Private Property and Labour).

For Marx, it was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust and especially Shakespeare and Middleton’s Timon of Athens that best captured this mysterious quality of money to turn things into their contraries:

Thus much of this will make

Black white, foul fair, wrong right,

Base noble, old young, coward valiant.

Ha, you gods! Why this, what, this, you gods? Why, this

Will lug your priests and servants from your sides,

Pluck stout men’s pillows from below their heads.

This yellow slave

Will knit and break religions, bless th’accursed,

Make the hoar leprosy adored, place thieves,

And give them title, knee, and approbation

With senators on the bench. This is it

That makes the wappered widow wed again.

She whom the spittle house and ulcerous sores

Would cast the gorge at, this embalms and spices

To th’ April day again.

(Timon, Timon of Athens 14.28-42)

Alcibiades is appalled to find Timon in his dishevelled, self-exiled state and asks how he came to this change. “As the moon does by wanting light to give”, replies Timon, “But then renew I could not like the moon; / There were no suns to borrow of” (Timon of Athens 14.67-69). The moon borrows light of the sun because it generates none of its own, which makes it a kind of thief. As Timon ponders this, he begins to find a kind of thievery in Nature:

The sun’s a thief, and with his great attraction

Robs the vast sea. The moon’s an arrant thief,

And her pale fire she snatches from the sun.

The sea’s a thief, whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears. The earth’s a thief,

That feeds and breeds by a composture stol’n

From gen’ral excrement. Each thing’s a thief.

(Timon of Athens 14.436-442)

If every circuit of exchange we find in the world is theft, the notion of theft loses all meaning since no-one is innocent of it. This revelation Timon shares with a group of thieves, encouraging them to steal on the justification that their victims must all be thieves too so it seems only right they should lose their ill-gotten gains. Marx had a pithy expression for it: “The expropriators are expropriated” (Capital volume 1, Chapter 32 “Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation”). An impoverished German intellectual pondering the origins of wealth gets his answer from an impoverished Athenian for whom universal lending and borrowing look much like theft. 400 years after his death, in the turmoil following an international credit crisis, Shakespeare retains the power to surprise us with such topicality.

Featured image: “Timon Laying Aside the Gold” by Johann Heinrich Ramberg (1829). Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rich and the poor in Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

A world with persons but without states

I have a question for you: what do Caesar, Genghis Khan, Napoleon, Hitler and the Nazis, Stalin, and ISIS all have in common? Answer: they’re all ultra-statists.

This is the third in a trilogy of OUP blog posts. The two earlier posts were also serious exercises in “entry-level” Kantian ethical anarchism.

Kantian ethical anarchism is ethical anti-statism. It says that there is no adequate rational justification for political authority, the state, or any other state-like institution, and that we should reject and exit the state and other state-like institutions, in order to create and belong to a real-world, worldwide ethical community, aka humanity, in a world without any states or state-like institutions.

I’ll start my argument with the basic Kantian premise that all human persons, aka people, are (i) absolutely intrinsically, non-denumerably infinitely valuable, beyond all possible economics, which means they have dignity, and (ii) autonomous rational animals, which means they can act freely for good reasons, and above all they are (iii) morally obligated to respect each other and to be actively concerned for each other’s well-being and happiness, aka kindness, as well as their own well-being and happiness.

Therefore, it is rationally unjustified and immoral to undermine or violate people’s dignity, under any circumstances.

Now I’ll quickly define some important terminology.

By political authority I mean the existence of a special group of people, aka government, with the power to coerce, and the right to command other people and to coerce them to obey those commands as a duty, no matter what the moral content of these commands might be.

By coercion I mean using violence (e.g. injuring, torturing, or killing) or the threat of violence, in order to manipulate people according to certain purposes of the coercer.

By the state or state-like institution I mean any social organization that not only claims political authority, but also actually possesses the power to coerce, in order to secure and sustain this authority.

And by the problem of political authority I mean: “Is there an adequate rational justification for the existence of the state or any other state-like institution?”

This problem applies directly to all kinds of political authority, states, and state-like institutions—basically, any social institution with its own army, navy, air-force, police-force, or armed security guards.

Here is my argument:

Immanuel Kant. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Immanuel Kant. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.If it is rationally unjustified and immoral for ordinary people to undermine or violate the dignity of other people by commanding them and coercing them to obey those commands as a duty, then it must also be rationally unjustified and immoral for governments to undermine or violate the dignity of people by commanding them and coercing them to obey those commands as a duty, no matter how those governments got into power.

But all governments claim political authority in precisely this sense.

Therefore, there is no adequate rational justification for political authority, states, or other state-like institutions, and Kantian ethical anarchism is true.

To make this even clearer, here is the same argument, by way of an analogy.

It is well known since Plato’s Socratic dialogue, the Euthyphro, that what is called divine command ethics is rationally unacceptable.

Divine command ethics says that God’s commands are good and right, just because God says that they are good and right, and God has the divine power to impose these commands on people, no matter what the moral content of these commands might be.

But this means that God can command anything, including commands that undermine or violate the dignity of people, which is rationally unjustified and immoral.

So divine command ethics is rationally unacceptable.

Correspondingly, statist command ethics says that governments’ commands are good and right, just because governments say that they are good and right, and they have the coercive power to impose these commands on people, no matter what the moral content of these commands might be.

In other words, governments play exactly the same functional and logical role in statist command ethics as God does in divine command ethics.

So, just as in divine command ethics, God can command anything, including commands that undermine or violate of the dignity of people, so too in statist command ethics, governments can command anything, including commands that undermine or violate the dignity of people.

Therefore, statist command ethics is just as rationally unacceptable as divine command ethics, and again, Kantian ethical anarchism is true.

This conclusion might seem incredible! But please consider this.

Since the time of the pharaohs and pre-Socratic tyrants, humanly-created states and other state-like institutions have explicitly claimed to possess political authority, and then have proceeded to use the most awful, cruel, and monstrous kinds of coercive power, thereby repressing, detaining, imprisoning, enslaving, torturing, starving, maiming, or killing literally millions of people, in order to secure their acceptance of their authoritarian claims.

Even allowing for all the other moral and natural evils that afflict humankind, it seems very likely that there has never been a single greater cause of evil, misery, suffering, and death in the history of the world than the coercive power of states and other state-like institutions.

Now imagine a world without states or other state-like institutions, in which all the members of humanity freely form various dignity-respecting sub-communities built on kindness, mutual aid, personal enlightenment and rational enlightenment, and the pursuit of authentic happiness, and then freely link them all together in a worldwide network of partially overlapping sub-communities, the worldwide web of humanity.

Isn’t that an infinitely better world than the world of states?

Jesus preached the ethical gospel of universal human love. Yet he also said: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

Kantian ethical anarchism says: “If Caesar and God can command things that undermine or violate human dignity, why should we render anything unto them? Render unto humanity the things that respect human dignity.”

But at Christmas time, isn’t it obvious that this is the ethical gospel of universal human love?

Featured image: 045 – Border Road, by Ian Wright. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A world with persons but without states appeared first on OUPblog.

January 2, 2016

A glimpse into the world of Shakespeare and money in the 16th and 17th centuries

What would it be like to live in Elizabethan England? One might be lucky enough to dress in embroidered clothing and commission portraits, or one might be forced to beg for alms in order to survive. Art in the 15th and 16th centuries, whether in paintings, maps, sketches, or engravings, gives us some idea of the social and economic structure of England at the time. They also provide insight into how money and wealth influenced Shakespeare and his work, ranging from his depiction of royalty to tradesmen, actors to beggars.

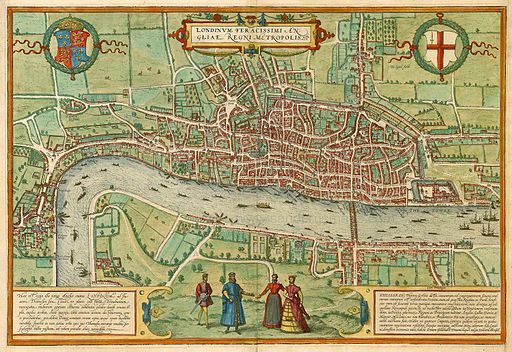

Antique map of London

Another work by Braun and Hogenberg, this antique map illustrates London during the Tudor dynasty.

(Image: “Antique map of London” by Braun & Hogenberg (1572-1624). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

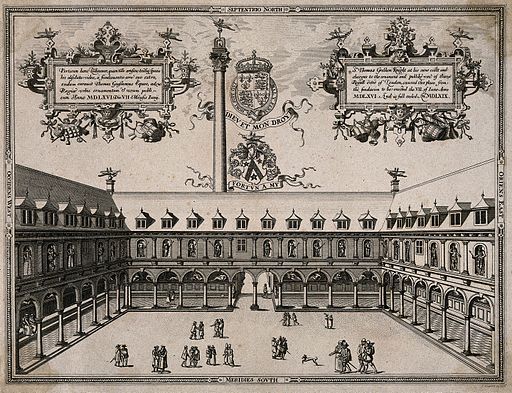

The Royal Exchange, London; view from roof height, with vari

Officially opened in 1571, the Royal Exchange of London was designed to be the center of commerce. This etching, which is modeled after a 1507 version, shows various people conducting business in the courtyard.

(Image: “The Royal Exchange, London; view from roof height, with vari” by B. Howlett. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Venice

This view of Venice was engraved and hand-colored by Hogenberg and Braun in 1565. It is based on the engravings of Bolognino Zaltieri, which demonstrate the wealth and naval power of Venice at the time.

(Image: “Venice” by G. Braun and F. Hogenberg (1565). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Allegory of America

Amerigo Vespucci, whose Latinized name ‘Americus’ later termed America, first demonstrated that the New World was not Asia, but a different continent altogether. In this engraving, based on the drawing by Stradanus, Vespucci awakens, or “discovers,” a sleeping America, a source of tremendous riches in the age of exploration.

(Image: “Allegory of America” by Stradanus (1575-1580). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Allegory of Fortune

Fortuna, or Lady Fortune, was the goddess of fortune and fate, and was often associated with good or bad luck. Shakespeare even references her in his Sonnet 29, lamenting that Fortune has abandoned the speaker. In this painting, circa 1530, Fortune balances the orb of sovereignty between her fingers.

(Image: “Allegory of Fortune” by Anonymous (circa 1520-1530). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Elizabeth Vernon, Countess of Southampton

This portrait of Elizabeth Vernon, the Countess of Southampton, circa 1600 represents her wealth and status not only in the quality and colors of her embroidered clothing, but also in her ability (or her husband’s) to have her portrait commissioned by an artist.

(Image: “Portrait of Elizabeth Vernon, Countess of Southampton” by Unknown. Private collection Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Card Players

Unlike most activities in England at the time, card playing was enjoyed by nearly all social classes. As seen in this oil painting, even women participated in card games and gambling.

(Image: “Card Players” by Lucas van Leyden (1508-1510). National Gallery of Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Jost Amman, A barber's shop

Jost Amman (1539-1591), a celebrated woodcutter, created most of his works for book illustrations. In this image, he depicts a typical barbershop.

(Image: “Jost Amman, A barber’s shop” by Jost Amman. Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

Giving Alms to a Beggar

In this illustration for “Of Pride” in John Day’s A christall glasse of christian reformation, a gentleman gives alms to a beggar.

(Image: “Giving Alms to a Beggar” by Unknown (1569). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Featured Image: “Take the Fair Face of Woman, and Gently Suspending, With Butterflies, Flowers, and Jewels Attending, Thus Your Fairy is Made of Most Beautiful Things” by Sophie Gengembre Anderson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A glimpse into the world of Shakespeare and money in the 16th and 17th centuries appeared first on OUPblog.

January 1, 2016

Simulation technology – a new frontier for healthcare?

While myriad forces are changing the face of contemporary healthcare, one could argue that nothing will change the way medicine is practiced, more than current advances in technology. Indeed, technology is changing the entire world at a remarkable rate – with mobile phones, music players, emails, databases, laptop computers, and tablets transforming the way we work, play, and relax.

Despite this, it is generally acknowledged that the adoption of technology in healthcare is slow and disparate. The Healthcare Industries Task Force, for example, has described the National Health Service as “a late and slow adopter of technology.” This is not that surprising, given the large costs and investments often involved – but a reassessment of attitudes needs to take place.

In 1834, the London Times described the stethoscope in the following manner:

That it will ever come into general use, notwithstanding its value, is extremely doubtful; because its beneficial application requires much time and gives a good bit of trouble both to the patient and the practitioner; because its hue and character are foreign and opposed to all our habits and associations.

Even today, we still tend to treat new technologies with restraint; a menace to time-honoured – if imperfect – ways of doing things. But in essence, such items are simply there to make life easier. To reassess, healthcare professionals must look at the ways technology can benefit their patients, colleagues, and themselves. After more than fifteen years of my own involvement in the field of simulation based learning, I felt it was time to reflect on the field’s progression.

‘Confucius’, circa 1770. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Confucius’, circa 1770. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Simulation-based medical training essentially involves learning with items or machines – instead of the patient. A simple example would be teaching students to handle needles, and sutures using a pig’s foot or a piece of simulated skin. A more complex example is the use of the famous Resusci Anne, a resuscitation manikin, to teach a partial task such as chest compressions and positive pressure ventilation. Today, computerized full-body manikins are considered the mainstay of simulation-training; they aim to represent patients, their signs, and symptoms.

Confucius made the case for the utility of simulation some 2,500 years ago, by observing that real experience, however profound in nature, was always tinged with risk. He further suggested that rehearsal was one of the best methods of learning:

By three methods we may learn wisdom: first, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest.

It would appear, therefore, that the concepts supporting the value of simulation are nothing new. The only thing that’s changed is the technology underpinning such practices.

Over the last decade, simulation has moved from being an emergent and disruptive educational innovation, to a mainstream element of most healthcare curricula. Whilst manikins have been widely available for practices such as CPR and airway management training, over the last decade – new simulators have been produced that are unprecedented in their functionality. New features reproduced many, but not all, of the signs seen in deteriorating patents. It became possible to interface them to commercial physiological monitors, anaesthesia machines, ventilators, and even cardiac defibrillators. Consequently, it became feasible to recreate most medical emergencies with acceptable realism.

Despite the feast of newer, increasingly sophisticated simulators and training aids, the adoption of such devices was not all smooth sailing. Funding was hard to come by (as initial investments were principally for hardware and buildings), and provision for educators was often missing from business plans. Universities could not exist without paid academics, but hospital-based training was frequently unfunded or buried within nonclinical time. Some simulation centres became starved of funding to implement and develop courses, improve their teaching skills, and train the next generation of educators.

One of the more obvious reasons why simulation-technology was characterised by a large trough after its initial adoption was the failure to develop strong partnerships with academic educators at an early stage. It is now common to hear of clinicians undertaking formal university-based education degrees, or more recently, medical education with simulation training. However, the early days of simulation-based education were populated by enthusiasts who were self-taught or learned from others in this new field – relatively isolated from the broader medical profession.

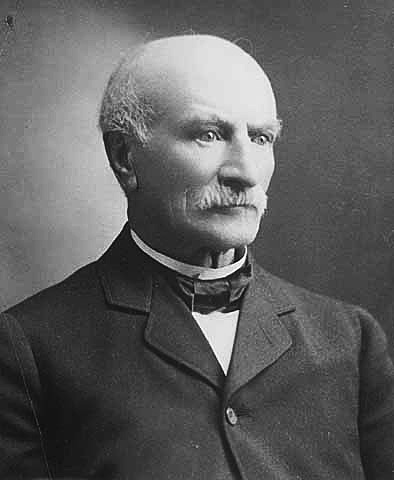

William Worrall Mayo, uploaded by BrandonBigheart. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Worrall Mayo, uploaded by BrandonBigheart. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Notwithstanding these difficulties, the benefits of simulation in medical training are easy to see. Clearly, it is self-evident that traditional medical education was (and still can be) lacking in many ways. Thinking back to my own medical internship fills me with some horror. The phrase ‘patient safety’ was never heard. Not only did I feel completely unprepared for my first year in a teaching hospital, I remember being mostly fearful of sick patients and accepting that on several occasions, I was probably contributing to their demise. At a personal level, this was not unexpected after several years of varying degrees of intimidation by clinical teachers. Internship was a new phase of trial-and-error care, and I often looked back at my own medical education and wondered why it did not prepare us better. Like many before me, I made a promise that I would try to be a better teacher than some who taught me.

As Dr William Mayo (one of the seven founders of the Mayo Clinic), stated more than ninety years ago, “There is no excuse today for the surgeon to learn on the patient.” With the rise of new, simulation-based technologies, this is now truer than ever. Clinical simulation training and assessment encompasses a range of tools, such as task trainers, virtual reality simulators, standardized patients, virtual patients, and computerized full-body manikins. As with any tool however, the effectiveness of simulation technology depends on how it is used. Those of us who have experienced both traditional and simulation-based learning, know that there’s a place for both. There is no going back, and it is imperative to actively foster the next generation of simulation champions, as well as the technology they rely on. Anything less is doing an injustice to future healthcare practitioners – and their patients.

Featured Image Credit: GlideScope practice by AllieKF. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Simulation technology – a new frontier for healthcare? appeared first on OUPblog.

Very Short Resolutions: filling the gaps in our knowledge in 2016

Why make New Year’s Resolutions you don’t want to keep? This year the Very Short Introductions team have decided to fill the gaps in their knowledge by picking a VSI to read in 2016. Do you agree with their choices and reasons below? Which VSIs will you be reading in 2016? Let us know in the comment section below or via the Very Short Introductions Facebook page.

Katie Stileman. Image used with permission.

Katie Stileman. Image used with permission.“This year I’m going to read Algebra: A Very Short Introduction. An unlikely choice for a History grad but author Peter M. Higgins convinced me of its importance in his article on mathematical literacy. Bad math can lead to silly mistakes and poor choices that are easily avoided otherwise!

—Katie Stileman, VSI Publicity

“This year I’m going to read Classical Mythology: A Very Short Introduction. I have an embarrassing lack of knowledge in this area so it’s definitely time. It will also help me to hold my own in conversations with my classics loving chum Malcolm!”

—Julie Gough, VSI Marketing

Amy Jelf. Image used with permission.

Amy Jelf. Image used with permission.“This year I’m going to brush up on my Shakespeare in time for the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death by reading William Shakespeare: A Very Short Introduction by Stanley Wells and eagerly anticipating Shakespeare’s Comedies: A Very Short Introduction after enjoying Much Ado About Nothing at the Bodleian last summer.”

—Amy Jelf, VSI Marketing

“Next year I want to find the time to read Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction. My interest was first piqued by reading the top ten facts about Buddhism, and I look forward to learning more about meditation and mindfulness in the new year. Any tips I can glean to remove the stress from my life would be welcome too!”

—Dan Parker, VSI Social Media

Chloe Foster. Image used with permission.

Chloe Foster. Image used with permission.“After working on VSIs for a number of years, not having them as part of my day-to-day life for the first time this year meant some pretty serious withdrawal symptoms from this incredible series. In 2016, I plan to fill the gap by reading Circadian Rhythms: A Very Short Introduction. The same author wrote the VSI to Sleep, which I think we’re all fascinated by – not getting enough, getting too much, and the quality of it.”

—Chloe Foster, VSI Publicity (2012-15)

“Next year I am going to read Exploration: A Very Short Introduction which was recommended to me by Nancy Toff, who commissions VSIs from the US office. As a VSI commissioning editor in the UK, it’s really nice to read a VSI from the other side of the pond!”

—Andrea Keegan, VSI Editorial

Wishing you a happy new year from everyone in the VSI team!

Featured image credit: VSIs, by the VSI team. Image used with permission.

The post Very Short Resolutions: filling the gaps in our knowledge in 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 31, 2015

Top ten OUPblog posts of 2015 by the numbers

On Tuesday, we shared our editors’ selections of the best of OUPblog publishing this year, and now it’s time to examine another measure: popularity, or in our case, pageviews. Our most-read blog posts of 2015 are… not published in 2015. Once again, Galileo, Cleopatra, antibiotics, and quantum theory dominated our traffic, and of our publishing this year, none of our most-trafficked articles made the editors’s picks. (This is something of a pattern. When we compiled our selections of the best of OUPblog’s publishing for our tenth anniversary, only one of the articles was in our list of top articles in terms of traffic.) Here’s the list of our top article published in 2015 in terms of number of pageviews.

#10 Women in Philosophy: A reading list

A reading list of key feminist and female philosophers

#9 Does philosophy matter?

The Philosophy in Action series editor speaks about the importance of philosophy

#8 The impossibility of perfect forgeries?

Although perfect forgeries might well be possible, we can never know, of a particular object, that it is a perfect forgery

#7 Four myths about the status of women in the early church

Author Susan Hylen discusses common myths concerning women and the church

#6 Ten myths about the French Revolution

Marisa Linton, author of ‘Choosing Terror’, debunks ten of the most pervasive myths regarding the French Revolution

#5 Seeing things the way they are

John R. Searle discusses the tough philosophical questions surrounding perception.

#4 Does a person’s personality change when they speak another language?

Arturo Hernandez on language, culture, memory, context — and personality changes

#3 The Ku Klux Klan in history and today

David Cunningham talks about the most common questions he gets as a Ku Klux Klan scholar

#2 Our exhausted (first) world: a plea for 21st-century existential philosophy

Kierkegaard’s diagnosis of our age (originally of his ‘early 19th-Century backwater of Europe’ age, but plus ça change…) is correct: we are failing to think in the right way about the demands of subjectivity, and indeed what it is to be a subject.

#1 10 academic books that changed the world

Which academic books do you think had the biggest impact on the world?

Featured image: Desk. Photo by Rayi Christian Wicaksono. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Top ten OUPblog posts of 2015 by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers