Oxford University Press's Blog, page 569

December 23, 2015

It’s not a crime, it’s a blunder

The author of the pronouncement in the title above is a matter of dispute, and we’ll leave his name in limbo, where I believe it belongs. The Internet will supply those interested in the attribution with all the information they need. The paradoxical dictum (although the original is in French, even Murray’s OED gave its English version in the entry blunder) is ostensibly brilliant but rather silly. We will avoid a comparative analysis of crime and blunder because we have our own ax to grind. The present post will serve as an addendum to the previous two, which were devoted to the troublesome history of blunt. For quite some time old etymologists tried to connect blunt and blunder and both of them with the Old English verb binnan “to stop,” a procedure that doesn’t deserve being called criminal, but blundering it certainly was.

Blunt, as we have seen, always ended in –t, and its presence here cannot be ignored or explained away. Also, though this is not absolutely certain, blunt, despite its comparatively late attestation in a 1200 poem, seems to be a native English word, while blunder is, most probably, a Middle English borrowing from Scandinavian. At first sight, blunder doesn’t pose great difficulties. In the fourteenth century, when it first turned up in texts, it meant “to confuse” and “to move blindly or stupidly.” Old Icelandic blundra “to shut the eyes” is a derivative of blunda “to blink” (so approximately “to blink many times until the eyes close”; a so-called frequentative verb, like stutter, quiver, along with many others ending in the suffix –er), and nearly identical forms occur elsewhere in the Scandinavian languages. But whether blunda and blink are related is far from clear. The hard question is not the history of blink but whether the sense “shut the eyes” could develop into “confuse.”

This a dead end, or a cul-de-sac, or a blind alley. It can indeed be rather confusing to a driver.

This a dead end, or a cul-de-sac, or a blind alley. It can indeed be rather confusing to a driver.Very close to blund-, as in Engl. blunder, is bland, not the adjective meaning “smooth” but the verb today better known from its doublet blend “to mix, mingle,” another word of Scandinavian descent. (The adjective bland is a borrowing of Latin blandus, and its etymology, irrelevant in the present context, remains a matter of speculation.) The gloss “move stupidly,” used above, makes one think of Engl. flounder (of course, the verb, not the fish name), and in some old dictionaries blunder and flounder were compared. The idea is not so bad, considering that flounder is sometimes believed to be a blend of founder “stumble” and blunder. But despite the fact that flounder was recorded much later than blunder and from an etymological point of view can offer no support to it, it is useful to remember how many fl- words denote unsteady or rough movement. The long list goes all the way from flow, flutter, flicker, and flounce to flip-flop.

It appears that one of the false leads in the search for the etymology of blunder was provided by the noun blunderbuss “a gun.” Blunderbuss came to English from Dutch, where its form is donderbus (donder “thunder” and bus “gun”). Why on its way to England a good, usable gun, despite the not too great phonetic similarity between donder and blunder, was associated with blunder will remain one of the mysteries of the capricious and unpredictable folk etymology. Engl. blunderbuss made some people think that blunder, in so far as it is connected with thunder via blunderbuss, is onomatopoeic. At the Indo-European level, the word thunder does seem to imitate the sound we hear from the sky (compare Latin tonare), but nothing follows from this fact about Scandinavian blundra or Engl. blunder, regardless of whether they are related or not. All things considered, Murray might have been right in thinking that blunder had absorbed the connotations of two verbs, one of them meaning “shut the eyes,” the other meaning “blend.”

Blind-man’s buff: most confusing!

Blind-man’s buff: most confusing!Germanic bland– (with the expected vowel variation, or ablaut, in the root) appears in many words. In this context, the most important of them is blind. As a rule, the names of perceived physical defects and all kinds of deformities are hard to trace, because people were afraid to pronounce them (for fear of “inviting” deafness, muteness, diseases, etc.) and intentionally garbled the sounds. This is what is meant by taboo. The same process affected the names of some wild animals, such as bear in Germanic (bear, unlike Latin ursus, is euphemistically “the brown one”). Centuries or millennia later we have no way of reconstructing the arbitrary changes in such words. But blind and also French aveugle seem to be exceptions to the grim rule (the origin of Latin caecus and Russian slep– is much more problematic). As already noted, the root bland- ~ blend- ~ blund- meant “to mix” and, by possible extension, “to confuse.”

There is some disagreement about both the oldest form and the original meaning of this root. I have cited the interpretation that appears to be the simplest and the most plausible one. Given this interpretation, “blind” means “confused.” Here too the consensus is not absolute, but once again it is perhaps reasonable to refer to the least involved solution. To blend obviously means “to mix, merge,” and no one doubts that blind and blend are related. If what is said here is correct, the definition of blunder “to move blindly” (in addition to “move stupidly”) is not only accurate from a semantic point of view; it also does justice to the word’s etymology, so that blind and blunder end up in close proximity both as words connected by ablaut and as neighbors in their reference to the real world: a blind man is said to “blunder.” For a change, today the conclusion does not inform the readers that here is one more word of unknown and almost unknowable origin. Although some difficulties remain, the whole carries a satisfying measure of conviction.

The triumph of nature rather than one of its blunders!

The triumph of nature rather than one of its blunders!In 1851 C. W. G., an active correspondent to Notes and Queries, sent the following letter to the journal:

“Blunder.—What is the origin of this word? In Woolston’s First Discourse on Miracles (London, 1721), at p. 28, I find the passage: ‘In another place he intimates what are meant by oxen and sheep, viz., the literal sense of the Scriptures. And if the literal sense be irrational and nonsensical, the metaphor we must allow to be proper, inasmuch as nowadays dull and foolish and absurd stuff we call Bulls, Fatlings, and Blunders’. This would seem to imply that in Woolston’s days blunder was the name of some animal; but in no dictionary have I been able to find such a signification attributed to it. The Germans use the words bock and pudel in the same sense as our word blunder.”

No one responded to this query, and I also wonder what Thomas Woolston could have meant. What animal did he have in view? Is it possible that he heard the Gothic word ulbandus “camel” (from an etymological point of view, it is a variant of elephant) and remembered it as blunder? The Russian name of the camel, allegedly borrowed from Gothic, is verbliud (stress on the second syllable). It is even closer to blunder. Mr. C. W. G. won’t hear our answer, but it would be good to clarify an old mystery.

Image credits: (1) dead end sign cemetery. Photo by Martin Alonso. CC BY 2.0 via martinalonsophotography Flickr. (2) Blindemannetje. Jongensspelen. H.A.M. Roelants, Schiedam ca 1860-1870. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Image from page 258 of “Notes of lessons on the Herbartian method (based on Herbart’s plan)” (1902). Internet Archive Book Images. No known copyright restrictions via internetarchivebookimages Flickr.

The post It’s not a crime, it’s a blunder appeared first on OUPblog.

Climate change poses risks to your health

When heads of state and other leaders of 195 nations reached a landmark accord at the recent United Nations COP21 conference on climate change in Paris, they focused primarily on sea level rise, droughts, loss of biodiversity, and ways to decrease greenhouse gas emissions in order to reduce these consequences. But arguably the most serious and widespread impacts of climate change are those that are hazardous to the health of people.

Climate change is already posing a variety of human health risks. It is increasing heat-related illness and death, not only among older people with underlying chronic diseases, but also among otherwise healthy workers exposed to extreme heat. The frequency and intensity of heat waves is expected to increase dramatically by 2050. Vector-borne infectious diseases, such as malaria carried by mosquitoes, are highly influenced by climate variability; with global warming, some of these diseases are spreading to areas where they have not previously been endemic. Water-borne infectious diseases may increase when torrential rainfall events are accompanied by flooding and resultant sewage contamination of water supplies. Rising temperatures increase ozone pollution, which exacerbates chronic respiratory disease, and increase pollen and other airborne allergens, which exacerbates chronic allergic disorders.

Climate change results in more droughts in some areas and more flooding in others, all of which threatens crop yields and food security and ultimately leads to increased rates of malnutrition. By creating scarcity of food, safe water, and other necessities, climate change can lead to political and social instability and, in turn, collective violence.

Climate change is raising sea levels, forcing more and more people to migrate, especially those in low-lying coastal areas in countries like Bangladesh and in island nations like Vanuatu; by 2050, there could be tens of millions of “climate refugees,” whose health is threatened in multiple ways. Increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, like Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy, will also lead to displacement of people as well as injury, illness, and death. And, as a result of all these problems, rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders will increase.

Not everyone is equally affected by health problems caused by climate change. These problems disproportionately affect people in low-income countries as well as poor people in the United States, European nations, and other high-income countries. The United States and China together account for approximately 40% of greenhouse gas emissions globally; however, low-income countries that emit the smallest amounts tend to have the highest rates of “climate-sensitive diseases,” such as malnutrition and malaria. Climate change is a risk multiplier, making populations already at high risk of illness and death to suffer even more.

Physicians, nurses, public health workers, and other health professionals need to increase their understanding of the health impacts of climate change. They need to play important roles in responding to climate change by supporting measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and measures to help the public adapt to and prepare for the effects of climate change. They need to raise awareness by the public and policymakers of the serious health impacts of climate change, and team up with people in other sectors to plan and support policies and programs to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change.

Many policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions offer large “co-benefits” for human health. For example, promoting renewable sources of energy, like solar and wind power, not only reduces climate-disrupting emissions from burning fossil fuels, but also decreases air pollutants that cause respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. Promoting walking, bicycling, and other forms of “active transport” – and promoting urban environments designed for people, not motor vehicles – not only reduces reliance on transportation based on fossils fuels, but also improves physical fitness and reduces cardiovascular disease and cancer. Finally, promoting less meat consumption helps to conserve environmental resources while improving nutrition and health.

So, as you hear more about how climate change is adversely affecting the health of the planet, think about how it is also adversely affecting the health of people. And find opportunities to support adaptation and mitigation measures that will both address climate change and provide “co-benefits” for health.

Featured image credit: “Solar power” by lenulenac. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Climate change poses risks to your health appeared first on OUPblog.

How the stories got their name: Kipling and the origins of the ‘Just-So’ stories

The storyteller has always been a figure of magic, and the circle a magic figure. This is Rudyard Kipling, casting his spell around 1902, the year the Just So Stories for Little Children were published. He is on a liner sailing from Southampton to Cape Town in South Africa, where the Kipling family had taken to spending the winter. It is a haunting image, because what lies behind the Just So Stories is another voyage, across the Atlantic to New York, four years earlier in the winter of 1898-99. Soon after their arrival, both Kipling and his firstborn child, Josephine, fell ill of pneumonia. The father lived; the child died. She was six years old.

The Just So Stories began as bedtime stories told to ‘Effie’; when the first three were published in a children’s magazine, a year before her death, Kipling explained:

. . . in the evening there were stories meant to put Effie to sleep, and you were not allowed to alter those by one single little word. They had to be told just so; or Effie would wake up and put back the missing sentence. So at last they came to be like charms, all three of them,—the whale tale, the camel tale, and the rhinoceros tale.

These are stories of origins: ‘How the Whale got his Throat’, ‘How the Camel got his Hump’, ‘How the Rhinoceros got his Skin’—stories that answer the kinds of question children ask, in ways that satisfy their taste for primitive and poetic justice. After Effie’s death, Kipling added nine others, so the number published in the first edition was twelve—a magic number, as everyone knows. Some were like the first three —‘How the Leopard got his Spots’, ‘The Elephant’s Child’, ‘The Sing-Song of Old Man Kangaroo’—and as a group these stories span the map of the Empire, from the High Veldt to the middle of Australia, from the shores of the Red Sea to the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees. Other stories, however (‘The Crab that Played with the Sea’, ‘The Cat that Walked by Himself’), take us to places of myth or fable: the Time of the Very Beginnings, when the Eldest Magician calls on the Animals to come out and play, and talks to a hunchbacked old man who sits in the Moon, spinning a fishing-line with which he hopes one day to catch the world; or the time when the Tame animals were wild, and walked in the Wet Wild Woods by their wild lones, and in which a woman makes the First Singing Magic in the world, gazing at the wonderful marks on the bone of a shoulder of mutton. In these different and darker tales the child’s simplicity is doubled like a garment with adult knowledge.

Kipling on board ship in 1902 en route to South Africa. © National Trust / Charles Thomas.

Kipling on board ship in 1902 en route to South Africa. © National Trust / Charles Thomas.Children take delight in order and method, in things worked out and resolved, in hierarchy and proper authority. They also delight in rebellion and recalcitrance. The Elephant’s Child returns home after his encounter with the crocodile on the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, and spanks his entire extended family with his newly-lengthened trunk—the reward, not of virtue and obedience, but of curiosity and undeserved luck. In Kipling the yearning to obey and belong is matched by the yearning to transgress and escape. These yearnings are not falsely ‘balanced’ against each other, but form unstable compounds. The figure of the outsider, Kipling’s great and perennial subject, can never be fully assimilated by any group. The storyteller in the photograph is both within and outside the circle.

On the title page of the first edition he gave to his two surviving children, Kipling crossed out ‘for Little Children’ and wrote ‘for John and Elsie’. But this was not true. Kipling loved these children, and Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) and Rewards and Fairies (1910) were indeed written for them. They are wonderful books, but they are ‘children’s literature’, and the Just So Stories are something other. They were written for Effie, their genius loci. In ‘Merrow Down’, the poem that follows ‘How the Alphabet was Made’, she is metamorphosed into the goddess of spring, dancing through the fern, her brows bound with bracken-fronds. She is ‘Unfearing, free and fair’, but her father lags far behind, ‘So far she cannot call to him’. (It is an astonishing reversal, for what we would expect him to say is that he cannot hear her—not that she cannot speak.) Like the lame child at the end of Robert Browning’s ‘The Pied Piper’, Kipling is left alone; for the storyteller is always a survivor.

Image Credit: Elephants, Creative Commons licence via Pixabay

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Can history help us manage humanitarian crises?

People frequently ask whether the study of history can help in managing humanitarian crises. This question is particularly timely given the massive outflow of refugees from Syria and the problems of admitting large numbers of refugees to other countries, including the United States. Millions of refugees overwhelm normal administrative, legal, and political procedures.

We have no option but to use past events, since we lack sufficient knowledge or instincts to solve present problems without any frame of reference. But different people will select different episodes, and they will come to understand them to different degrees. Those who speak confidently of a single lesson of the past most often mislead their audiences.

Nonetheless, there is some merit in the popular saying usually misattributed to Mark Twain, “History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes.” The mastermind of the 13 November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris was Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a Belgian of Moroccan origin, who had traveled to Syria and returned surreptitiously to a Europe in the midst of a refugee crisis. The self-proclaimed Islamic State’s ability to exploit confusion and chaos in Europe set off alarm about refugees generally, a concern that quickly spread to the United States. Those who had studied the history of refugee movements knew that in some ways this was reminiscent of the events of mid-1940.

The sudden German conquest of France in May-June 1940 shocked many outside observers. They concluded that a conspiracy lay behind the French collapse, and the Nazis, as (alleged) masters of subversive methods, were obvious suspects. William Bullitt, the outgoing US ambassador to France, told a Philadelphia audience that more than half the spies captured in France were refugees from Germany. There was little evidence to support this claim, but Bullitt could pass as an expert.

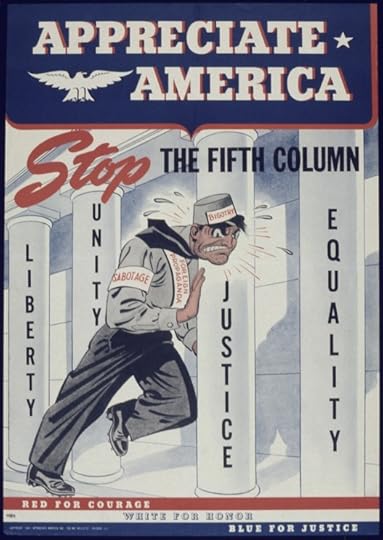

A few years earlier, the Spanish Civil War had given rise to the term Fifth Column. In addition to four contingents of nationalist military forces fighting to overthrow the Republican government, there was a fifth element—secret nationalist supporters within Madrid, who would rise up at the appropriate moment. In mid-1940 American authorities quickly concluded that a Nazi Fifth Column already was operating in the US, and that Jewish refugees were part of the problem. Some believed that Jews would do whatever was in their financial interest. Others thought that the Nazis were coercing Jewish refugees to serve as spies through threats to shoot their relatives still in Germany. According to polls, almost half of the public feared a Fifth Column in America.

“Appreciate America Stop the Fifth Column” by U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Appreciate America Stop the Fifth Column” by U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The Fifth Column scare in a presidential election year led to a series of decisions in the State Department to cut immigration radically—mostly by throwing up new security barriers and bureaucratic requirements. Within a short time any visa applicant with close relatives in totalitarian countries—Germany, Italy, and the USSR—was considered a security risk. Among those caught by new barriers in 1941 was Otto Frank, who sought American visas for himself and his family. The Franks lived in Amsterdam, but they still came under the immigration quota for their native Germany, and there was room for them under the German quota. But despite having a high-level friend within the Roosevelt administration, they could not manage to overcome the obstacles. After the Nazis intensified persecution and began to deport Jews from the Netherlands, the Franks went into hiding in the house on the Prinsengracht, and Anne Frank produced her now famous diary. In 2007 the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research commissioned me to write the story of the Franks’ efforts to obtain visas.

In late November 2015, (without my involvement) Elahe Izadi from the Washington Post drew on my research to suggest a parallel between American reaction to the threat posed by Syrian refugees and American reaction to Jewish refugees in 1940–1941.

Studying the past is useful in various, subtle ways. It helps us to know that current problems often are variants of earlier ones. It gives us some sense of what has not worked in the past. It can help us understand the intellectual and emotional reactions of people in earlier eras, and that understanding can allow us to deal more carefully with immediate pressures. Bringing past studies of refugees together with present concerns thus allows us to see in clearer light.

In a peculiar way, the current refugee crisis also helps us grasp the past better. I used to struggle to convince people that fears of a Nazi Fifth Column were real and not simply a cover for anti-Semitic prejudice. (Of course, a substantial number of the fearful, such as William Bullitt, were antisemitic, too.) After the current terrorism in Paris, it is not hard to imagine even larger fears in 1940. It is a coincidence and an irony that events in France set off both backlashes against refugees. Perhaps the United States will succeed this time in screening refugees individually.

Only a handful of Nazi spies posing as refugees made it to the US. So, is this 1940 all over again? Large numbers of Jews could not simply walk away from a Nazi-dominated Europe. A European Union with relatively open borders has problems very different from those of the nation-states of World War II Europe, and the threat from the Islamic State is real, not imaginary. History does not repeat itself; it merely rhymes.

Image credit: “Syrian refugees strike in front of the Budapest Keleti railway station” by Mstyslav Chernov. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Can history help us manage humanitarian crises? appeared first on OUPblog.

Aesthetics and the Victorian Christmas card

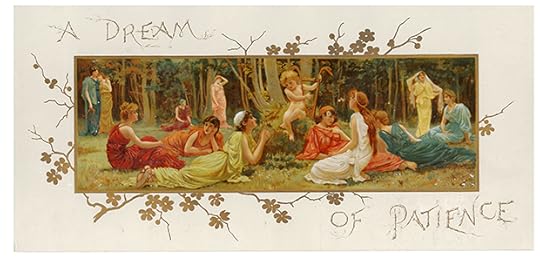

When we think of Christmas cards, we usually picture images of holly, robins, angels, and candles, or snow-covered cottages with sledging children, Nativity scenes with visiting Wise Men, or benevolent Santas with sacks full of presents. Very rarely, I imagine, do we picture a summer woodland scene features lounging female figures in classical dress and a lyre-playing cherub [see figure 1]. This classical scene, however, featured on one of the most successful Christmas cards of the 1882 holiday season.

Figure 1. Alice Havers, ‘A Dream of Patience’, Hildesheimer & Faulkner, 1882. First prize winner. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.

Figure 1. Alice Havers, ‘A Dream of Patience’, Hildesheimer & Faulkner, 1882. First prize winner. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.While the traditional images that grace contemporary Christmas cards have always been popular decorative motifs, the Victorian Christmas card industry also embraced a much more varied and experimental set of design practices. Some nineteenth-century innovations are fairly familiar to us, such as pop-up cards or mechanical movement cards where a pull-tab makes an image move. Other novelties may seem somewhat more alien. There were shaped cards that imitated a range of items such as ladies’ gloves, a fan, luggage tags, slices of bacon, and extracted teeth, and cards that were decorated with a profusion of added-on materials such as samples of lace, bits of sparkling glass, grass, seaweed, dried flowers, velvet, and cigar ends. There were scented cards, cards which were painted on ivory tablets, and cards that included packets of needles, a needlework design, and piece of decorative textile that could be used as the centrepiece of any number of needlework creations from d’oyleys and table mats to cushions and footstools.

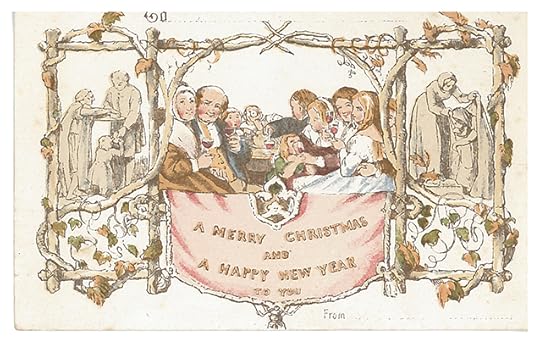

The eclecticism and oddity of these objects was partly a consequence of the greeting card industry’s attempts to attract more interest in what was a fairly new and still developing industry. Though Christmas cards are now an intrinsic and almost mundane convention of the Christmas season, the Christmas card was an innovation of the Victorian publishing industry. The first card was designed in 1843 by the artist John Callcott Horsley at the request of Henry Cole, the great Victorian champion of the industrial arts who was largely responsible for both the building of Victoria and Albert Museum and the creation of the Penny Post [see figure 2]. And it was only in the 1870s that the exchange of Christmas cards became a more common activity as technological developments in industrial colour printing, known as chromolithography, made elaborate, highly-coloured images easier and cheaper to produce.

Figure 2. J.C. Horsely, ‘A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You’, produced for Henry Cole, 1843. Reproduced De la Rue & Co, 1881. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.

Figure 2. J.C. Horsely, ‘A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You’, produced for Henry Cole, 1843. Reproduced De la Rue & Co, 1881. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.The beauty and vibrancy of a card such as “A Dream of Patience” was made possible by such industrial developments, but the design of such a card, which had more in common with the conventions of fine and decorative art rather than holiday sentiment, was driven by other factors. “A Dream of Patience” was created, like many other decorative objects in the 1880s, to satisfy increasing consumer demands for everyday items produced the decorate the “House Beautiful,” the Aesthetic Movement’s concept of interior design that sought to transform the middle-class Victorian interior into a haven of beauty and good taste.

Figure 3. Alice Havers, ‘A Christmas Greeting with Love’, Hildesheimer & Faulkner, 1881. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.

Figure 3. Alice Havers, ‘A Christmas Greeting with Love’, Hildesheimer & Faulkner, 1881. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.Such aesthetic cards [see figure 3] present themselves as beautiful objects, to be appreciated as much for their artistic merit as for their function in spreading seasonal good wishes. But can a Christmas card be considered an example of fine art? Card publishers certainly tried to draw such comparisons. The publisher Raphael Tuck & Sons, for instance, created a number of card series that directly referenced the practices and conventions of fine art, such as a “Royal Academy” series, which featured only the designs of artists who were members of the Royal Academy, and an “Easel Series,” in which the card came with its own papier-mâché easel so that it could be elegantly and appropriately displayed on a mantelpiece.

Raphael Tuck was also the first publisher to hold a design competition which culminated in November 1880 in an exhibition in which 925 drawings for Christmas cards were shown for ten days at the Dudley Gallery. The first prize winner, Alice Squire, was awarded £100, and her design was commissioned for the next holiday season [see figure 4]. Other publishers soon followed suit with bigger and better competitions in the years that followed.

Figure 4. Alice Squire, ‘With Many Merry Christmas Greetings” Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1881. 1880 Christmas card competition first prize winner. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.

Figure 4. Alice Squire, ‘With Many Merry Christmas Greetings” Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1881. 1880 Christmas card competition first prize winner. Image used with permission from Peter Wadham.Whether or not such cards could ever be considered as examples of fine art, throughout the 1880s they circulated widely and among all classes as beautiful decorative objects that fulfilled the Aesthetic Movement’s aspiration to bring beauty to the masses. Writing in the 1890s, the artist and editor of the art magazine The Studio, Gleeson White, pictured the ‘bewildered breakfast tables in the suburbs, in the year of grace 1884’ who opened their Christmas cards only to be taught lessons in art. Such cards circulated, as Christmas cards do now, in their millions, and in doing so they attempted to bring with them into the wider public domain lessons in art that sought to inform the average, middle-class consumer of the aesthetic value of the decorative arts, teaching bewildered bourgeois suburbians how to discriminate and how to find beauty in even the humblest of everyday objects.

The post Aesthetics and the Victorian Christmas card appeared first on OUPblog.

December 22, 2015

A history of black actors in the Star Wars universe

Nowhere is media’s influence on social attitudes more evident than among the millions of fans following Star Wars. Decades after the franchise’s creator, George Lucas, made his first iteration of the fictional galaxy filled with aliens, Stormtroopers, and the Force, his vision has captivated fans with countless iconic moments. Few of these moments, however, feature black actors. “George, is everybody in outer space white?” filmmaker John Landis is quoted as saying after seeing the first film. The gradual inclusion of diversity in the series’ latest installments, including its prequels, has been a boon for many fans. From the off-screen performance of James Earl Jones in the original trilogy to John Boyega’s central role in The Force Awakens, black representation in films has evolved over the decades, ultimately coming to play a vital role in the trilogy.

Billy Dee Williams

Character: Lando Calrissian

Appears In: The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi

The New York-born actor was a household name from movies like Brian’s Song, Mahogany, and Lady Sings The Blues when he was chosen to be the smooth-talking Calrissian, a pseudo-sidekick to Harrison Ford’s Han Solo. Critics pointed out his character was on the stereotypical side, with his penchant for gambling and womanizing. Nonetheless, his depiction of the charismatic ladies’ man left a lasting impression on fans as the only black character with a speaking role in the original trilogy.

James Earl Jones

Character: Darth Vader (Voice)

Appears In: Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi

It wasn’t just the visuals of space that captivated fan imaginations, but the sounds as well. From the light sabers to the battles between The Galactic Empire and rebel forces, no other sound was more iconic than James Earl Jones’ voice as Darth Vader. The actor who played Darth Vader on screen had a strong regional English accent, so Lucas hired Jones to lend his deep, baritone voice to the character, giving Darth Vader authority and menace.

Samuel L. Jackson

Character: Mace Windu

Appears In: Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, Revenge of the Sith

Samuel Jackson was already a star when he lobbied for the role. Though moviegoers already knew the character wouldn’t survive to Episode IV, seeing a black man have one of the highest statuses in the Star Wars universe was still important for many fans. In keeping with his on- and off-screen “badass” persona, Jackson used his influence to negotiate a more “spectacular” death scene.

Ahmed Best

Character: Jar Jar Binks

Appears In: Phantom Menace, Revenge of the Sith

When speaking of African-American characters in the Star Wars universe, this particular entry is often raised as a negative example. Like Andy Serkis provided the movements and voice for Gollum in the Lord of the Rings, African-American Stomp actor Ahmed Best was Jar Jar Binks in the Star Wars prequel trilogy. While his character was created as comic relief he was not well received by fans and critics alike, in part due to his stereotypical Jamaican accent.

John Boyega

Character: Finn

Appears In: The Force Awakens

While Landro Calrissian was a major character, Finn is the first protagonist of the series played by a black actor. 38 years after the release of the first film, some fans were upset to learn that the First Order Stormtrooper and eventual hero would be black, prompting a call on social media to boycott the movie using the hashtag #boycottStarWarsVII, with some calling the decision “anti-white propaganda.” The response to this prompted a more positive hashtag, #CelebrateStarWarsVII, that praised the casting decision, as tweeted by Selma director Ava DuVernay.

Lupita Nyong’o

Character: Maz Kanata

Appears In: The Force Awakens

Reports of Nyong’o nabbing the role of an alien pirate who provides refuge for freedom fighters came fresh off her Oscar win for her role in 12 Years A Slave. Like Ahmed Best, the stunning beauty lends her voice rather than her physical likeness to her character. Most notably, while co-star Boyega received much criticism for his role as Finn, not much negativity was lobbed at the actress. Perhaps critics of the imaginary world are more comfortable with black stars in smaller, more morally dubious roles than they are with them at the forefront as heroes.

Hugh Quarshie

Character: Captain Panaka

Appears In: Phantom Menace

Relatively unknown in the United States (unless you’re a Highlander fan),the Ghana-born actor and member of the Royal Shakespeare Company portrayed the loyal Head of the Naboo Security Forces who was in charge of Padmé Amidala. While Captain Panaka is not as significant of a character as Lando Calrissian, Quarshie provided much needed diversity to the supporting cast.

Image Credit: “Stars Sky Night.” Public Domain via PublicDomainPictures.net.

“James Earl Jones” by SJ Mayhew, U.S. Embassy London. CC BY ND 2.0 via Flickr. “Billy Dee Williams at the Phoenix Comicon in Phoenix, Arizona” (1), “Samuel L. Jackson” (2), “John Boyega” (3) by Gage Skidmore. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr. “

Ahmed Best at the Big Apple Convention in Manhattan” by Luigi Novi. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. “Lupita Nyong’o” by Gordon Correll. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A history of black actors in the Star Wars universe appeared first on OUPblog.

The Big Picture and “The Big Short”: How Virtue helps us explain something as complex as the Financial Crisis

The star-studded new film The Big Short is based on Michael Lewis’s best-selling expose of the 2008 financial crisis. Reviewers are calling it the “ultimate feel-furious movie about Wall Street.” It emphasizes the oddball and maverick character of four mid-level hedge fund managers in order to explain what it would take to ignore the rating agencies’ evaluations and bet against the subprime industry—that is, their own industry. The men depicted made a lot of money from hoping that the housing bubble would burst, which would, as they themselves acknowledge, harm countless people. Nonetheless, they are the heroes of the story. As the director Adam McKay says, “you’re rooting for these guys,” even though they are “kind of doing their job. The way the market’s supposed to work is, if there’s a bad investment, you short it.”

But if this is the way the market is supposed to work, someone needs to explain this to the hedge fund managers on whom the film is based, who, in real life as in their cinematic depictions, cannot get over the insanity of their situation. If anyone is likely to defend the upside of the housing crisis, it would seem to be a person who is benefitting in the tens of millions from it. And yet these men continue to cite greed, stupidity, and arrogance as the reasons for the housing bubble that earned them millions.

Perhaps it is wrong to expect that the financial crisis, or any crisis at all, can be explained through a few characters or clever dialogue. For example, there were more ‘players’ involved in the financial crisis than can be included in any dramatic depiction. Even economists using the most abstract mathematical tools can’t seem to penetrate the complexity of the crisis, especially the ethical (or unethical) dimensions of the behavior that contributed to it. No matter how complex the processes, the psychology of the players, or the motivations behind the actions organizations take, if we cannot make moral sense of our own roles and behaviors, we are in an uneasy position, unable to answer the simplest of questions, such as:

Shorting the housing market was a bold thing to do, but what makes it a good thing to do?

Not seeing through the implications of various policies put in place was an imprudent thing to do, but what makes it an immoral thing to do?

Defrauding investors or tempting clients into unworkable arrangements is recognized as wrong by even those engaging in the behavior, so if it makes a profit, or sustains a system, does that override personal discomfort with the effort?

‘The Big Short’ shows us that virtue has an important role in explaining behavior,… even in fields as technical and apparently ethically ‘sterile’ as modern finance.

These are questions that ultimately need answering with an account of moral psychology, something philosophers working in virtue ethics are well suited to provide. An account of virtue is a way of proposing and then testing an account of moral psychology that can be incorporated into traditional economic analysis. An account of virtue will answer what counts as good behavior, what motivates it, and even what justifies it, moreso than the traditional modelling of economic choice as a cost-benefit problem.

When developed in isolation from the actual ‘players’ in the financial market, moral psychology can seem like a quaint guide to living well. Applied to the questions we want answered about our financial system, however, it gains a new relevance. It proposes that behavior that makes agents uncomfortable is presumably wrong, and perhaps even imprudent, and allows us to test the implications of this. It asks us to defend our systems in terms of human good, wherein long-term financial well-being is a part but not the entirety of that. To think of virtue in relation to economics—even the bewilderingly ‘scary and very complicated’ aspects that no one explains easily without math and the film’s characters refer to as ‘the abyss’— is the only way to fully explain our roles within a complex system such as modern finance. After all, even our most advanced economic methods, so complex that the public is never likely to learn them, are still part of our shared and social world. We do not have to pretend they are simpler, or that it all boils down to character, to question the role they play for us all. We want to know, after all, the contribution that economic spheres of life make to the rest of it.

The film’s main characters are ambivalent about their ability to profit from others’ losses. How can we convince them otherwise? First, we would point out that it is a mistake to assume that virtue is nothing more than living up to the standards of the economic model of the human actor—that is, pursuing one’s self-interests while staying within minimal bounds of morality. Not even those who developed this approach for economic modelling meant it to amount to a model of character, identity, or virtue. No real person behaves exactly as the homo economicus of economic models would predict, and failing to measure up to that standard is no real failing.

Second, no one sphere of life, not finance or business, is capable of working as a guide to life in general. When we replace an account of human good with one meant to explain only economic behavior, we can become confused about what the good means to us. The explanation that shorting the market was ‘business as usual’ is not a comfort to those buffeted by the financial crisis, either.

The Big Short shows us that virtue has an important role in explaining behavior, even in fields as technical and apparently ethically ‘sterile’ as modern finance. More broadly, even though it dates back several millennia, virtue ethics can provide us with new ways to understand modern phenomena such as the recent financial crisis. It does so, not by replacing mathematical economic analysis, but by supplementing it with an explicit normative framework to help explain what went ‘wrong’—in all senses of the word.

Headline image credit: Wall Street sign by Rev Stan. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Big Picture and “The Big Short”: How Virtue helps us explain something as complex as the Financial Crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

The politics of “carpet-bombing,” the ignorance of history, and the usefulness of modern air power

Seemingly all the US presidential candidates, in both parties, agree that “something more” should be done about Daesh or ISIS. Most of them, especially the Republican candidates, seem to think that doing more involves more unrestrained bombing (it is unclear if any of them recognize the similarity to demands for unrestrained bombing of Vietnam). Senator Ted Cruz rendered a particularly vivid version when he called for “carpet bombing” ISIS until the sand glowed, first in a speech on 5 December, and then again during the debate on CNN on 15 December. On 12 November Donald Trump opined that we should “bomb the shit” out of them. I privately hoped that some future debate moderator might challenge this sort of meaningless rhetoric.

At first, my hopes were raised. CNN moderator Wolf Blitzer challenged Mr. Cruz, asking whether his call for carpet bombing would mean “leveling the ISIS capital of Raqqa in Syria where there are hundreds of thousands of civilians?” After some rhetorical dodging and a bit of misplaced historical comparison, to his credit, Mr. Cruz clarified: “You would carpet bomb where ISIS is — not a city, but the location of the troops. You use air power directed — and you have embedded special forces to direction the air power. But the object isn’t to level a city. The object is to kill the ISIS terrorists.” We will return to the problems with this clarification in a moment, but as a historian I was disappointed in the next day’s “Debate Fact Check” in the Washington Post. The fact-checkers rightly pointed out that carpet-bombing is not much used these days, but they also claimed that it had essentially gone out with the advent of precision-guided munitions (“smart bombs”) that debuted in the 1991 Gulf War. Thus even the fact checkers missed the real point and mucked up the history.

This isn’t just historical nitpicking. This matters. When frighteningly viable presidential candidates talk about making the sand glow, responsible voters need to take note. When otherwise responsible media outlets can’t get their facts straight while fact-checking, those voters are poorly served by the fourth estate. These kinds of fallacies, mis-rememberings, and outright failures to understand either the history or the current nature of violence applied from the air matter, because that is how America applies its hard power these days. Yes, we have a variety of other means, and we do use them, but political rhetoric and very often the first recourse of the commander-in-chief is to strike from the air. So let’s review.

Avro Lancasters carpet bomb a road junction near Villers Bocage, Normandy, France, 30 June 1944. Imperial War Museum Collections. Collection No.: 4700-19; Reference Number: CL 344. Royal Air Force. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Avro Lancasters carpet bomb a road junction near Villers Bocage, Normandy, France, 30 June 1944. Imperial War Museum Collections. Collection No.: 4700-19; Reference Number: CL 344. Royal Air Force. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.American planners for the bombing campaign in Europe during World War II hoped to bomb industrial targets with great precision and thereby degrade or even destroy German war fighting capacity. They quickly discovered that weather, German air defenses, and technological shortcomings in the bomb sights and navigation systems meant that those raids were far from precise. Achieving results, against either industrial plant or troops deployed to opposed the Normandy landings, meant essentially bombing areas. Waves of planes dropped bombs in dense patterns over wide areas, hoping that enough of them would hit something of importance–thus “carpet-bombing.” There was no other real choice. The lack of precision combined with the massive numbers of bombs led not only to the indiscriminate destruction of German cities, but also the killing of tens of thousands of French civilians, and occasionally fratricide when the bombers released too soon over friendly troops. Similar use of bombers against area targets occurred at times in Korea, Vietnam, and during the 1991 Gulf War. This is where the Washington Post errs. Something like 92 to 94% of the weapons dropped in 1991 were old-fashioned “dumb” bombs. Media coverage at the time emphasized the use of seemingly new precision-guided munitions (generally laser-guided bombs and cruise missiles, actually first used in the early 1970s), but dumb bombs dominated. Furthermore, at times the United States “carpet-bombed” Iraqi troops in defensive positions along the Kuwait-Saudi Arabia border. Survivors attested to those attacks being particularly terrifying, as had their North Vietnamese predecessors.

In 1991, however, those Iraqi troops were literally in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by empty desert, and relatively easy to see from the air. There was virtually no possibility of collateral damage from the carpet-bombing raids (some collateral damage did occur from mis-directed raids in more urban areas, but no carpet-bombing took place in Iraqi cities). This difference is what really matters in critiquing Mr. Cruz’s comments. He ignores several key realities about modern air power. One is that precision bombing of the kind we are currently doing in Iraq and Syria is much more effective than any form of area bombing. During World War II, it took some 50,000 sorties over German oil refineries to cut their oil production by 60%. In 1991, using precision weapons, the United States reduced Iraqi oil production to near zero after ten days of attacks and only 500 sorties. Another reality, however, is that precision munitions aren’t cheap. In 1991, although comprising only roughly 8% of the munitions, precision weapons accounted for 84% of the cost of the air campaign. Some of our precision munitions are now cheaper, but that has not kept us from beginning to expend them faster than we are making them, as recently reported by the Air Force Chief of Staff. Finally, Mr. Cruz’s effort to clarify that we would not bomb Daesh in the cities, but only their troops, ignores the reality that Daesh is perfectly aware of their vulnerability in the open, and now rarely if ever masses troops outside of cities. Urban fighting is not just the current reality in Syria and Iraq, it is the wave of the future (a reality also recognized in emerging US Army doctrine). Urban environments, surrounded by civilians, provide the best protection for insurgent or terrorist forces from US air power. There is no sand to make glow, only civilian populations. The same civilian population we hope to persuade of American democratic values.

Featured image: Exploding bomb. (c) MADIA via iStock.

The post The politics of “carpet-bombing,” the ignorance of history, and the usefulness of modern air power appeared first on OUPblog.

Did comedy kill Socrates?

2015 has seen a special landmark in cultural history: the 2500th anniversary of the official ‘birth’ of comedy. It was in the spring of 486 BC that Athens first included plays called comedies (literally, ‘revel-songs’) in the programme of its Great Dionysia festival. Although semi-improvised comic performances had a long prehistory in the folk culture of Athens, it was only from 486 that comedy became, alongside tragedy (which had an older place in Athenian festivals), one of the two defining archetypes of theatre – and, with the passage of time, a concept applicable not just to an artform but to a way of thinking or feeling about aspects of life in general.

Yet if comedy has been an indispensable category in both art and life ever since, it has always been a controversial and problematic one too – a source of mirth and celebration, but with a darker, potentially troubling side that stems from the capacity of collective laughter to humiliate and wound. The history of comedy, both inside and outside the theatre, is littered with attempts to curb or prohibit the power of mockery and satire. Even in classical Athens, the culture that had given comedy a prestigious place in its public festivals, there were intermittent concerns about how far the city could tolerate ridicule of its democratic institutions and policies.

It would be naive, though, to think that when comic freedom is at stake, it is always pitted against those in power. Comedy can just as easily be populist: on the side of the majority, and against individuals or groups who don’t fit in or conform. A fascinating early test-case of such issues is Aristophanes’ play The Clouds, staged in 423 BC, in which the philosopher Socrates is presented as a remote, haughty figure who repudiates normal Greek religion, worships private deities of his own, and runs a special school (the Thinking Institute) in which ideas subversive of traditional morality are taught. Is Clouds, then, a maliciously anti-intellectual comedy? Might it even have contributed to popular hostility against Socrates and the shattering fact of his execution in 399 BC on charges of rejecting the city’s gods and corrupting the young. Can comedy really be that powerful?

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Philip-Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Philip-Joseph de Saint-Quentin, 1762. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Two things in particular have conspired to give these questions a disturbing historical edge. The first is that the surviving version of Clouds ends with the burning down of Socrates’ school (including, so some have supposed, the ‘death’ of Socrates and his pupils) by a disgruntled Athenian who thinks he has been cheated by Socrates: an incitement to violence against dangerous intellectuals, some critics of the play have believed. The second is a notorious passage in Plato’s Apology, a fictionalised version of Socrates’ defence speech at his trial, where the philosopher claims that his slanderers are too numerous to name – ‘unless one of them happens to be a comic poet’. Later in the Apology, Socrates refers explicitly to Clouds as a work which represents him ‘spouting a lot of nonsense on matters about which I know nothing whatsoever’. So we have a document written soon after Socrates’ lifetime’that tells us that Clouds had contributed to the hostile, anti-intellectual prejudices that led to the death of Socrates. Or do we?

Well, the first problem is that Plato’s Apology was written about 25 years after the first and only performance of Clouds. Plato himself was only about four years old in 423 BC and can’t have witnessed the play’s original reception (which was in fact, we know, something of a theatrical failure.) Over that intervening quarter-century, many of those who had seen Clouds on stage must have died (not least in the devastating losses of the Peloponnesian War.) Very few of the jurors who condemned Socrates in 399 can have known much if anything about Aristophanes’ comedy.

Still, it might be countered, Plato could have known, as he grew to adulthood, the sorts of things people said about Socrates, so he could have observed the insidious influence of Clouds in helping to corrode the philosopher’s reputation among his fellow Athenians. Why else would he have inserted those passages in the Apology? But matters are not so simple; even scholars are vulnerable to the uncritical repetition of received ideas. If one rereads those passages of the Apology with sensitivity to context and nuance, it ceases to be clear that they attribute to Clouds any serious influence on popular beliefs about Socrates. The first passage actually goes on to contrast Aristophanes, the unnamed comic poet, with those who have ‘maliciously’ slandered Socrates. And the second passage uses Clouds to drive home the point that it is precisely in a world of comic ‘nonsense’ that certain ideas about Socrates belong.

It’s doubtful, in fact, whether the historical Socrates ever mentioned Clouds at his trial: there is no suggestion of this in Xenophon’s Apology, an alternative version of the defence speech. But whatever Plato’s motives for making him do so, they cannot be shown to involve the claim that comedy helped to ‘kill’ Socrates, only that Aristophanes’ play offered a ludicrously distorted image of the man. But what about the ending of Clouds itself – the burning down of the Thinking Institute? Isn’t that proof of the work’s populist appeal to anti-intellectual sentiment?

No, it isn’t. It is a piece of pantomime theatre (the text proves, for one thing, that Socrates and his pupils do escape), and its dramatic significance only emerges when we read the whole play and take the measure of the Athenian bumpkin, Strepsiades, who perpetrates the arson. Strepsiades is himself mocked remorselessly for ignorance and stupidity at least as much as Socrates is caricatured for hyper-intellectualism. Much of Clouds requires the audience to ‘get’ intellectual ideas that Strepsiades fails to get, and all of it invites them to relish the absurd gap between intellectual and ignoramus, not side with one against the other. Aristophanic comedy, with its heady mixture of fantasy and satire, is too slippery to be reduced to a consistent agenda. It aims to expose almost everything to the bracing challenge of laughter. But it did not encourage the Athenians to kill Socrates: Aristophanes could never have envisaged the very different circumstances in which that tragic event came about.

The post Did comedy kill Socrates? appeared first on OUPblog.

Carol: a “touching” love story both literally and musically

Todd Haynes’ new film Carol is an adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s semi-autobiographical novel The Price of Salt, first published in 1952 under the pseudonym Claire Morgan. Daring for its time, the novel depicts a passionate lesbian romance between Carol Aird (Cate Blanchett), a well-off middle-aged New Jersey housewife divorcing her husband, and 19-year-old Therese Belivet (Rooney Mara), who works as a department store salesclerk. Despite differences between the novel and the film, one powerful element of “feeling” not often noted in discussions of literary or cinematic techniques carries over from the page to the screen in this masterful adaptation: the expressive potential of tactility, of touching, in the novel and in specific visual and musical elements of the film.

A pair of women’s gloves becomes an important catalyst in the film when Carol leaves her gloves behind on the store counter where Therese works. In the novel, though, “the woman picked up her gloves from the counter, and turned, and slowly went away, and Therese watched the distance widen and widen.” In the novel Therese decides to mail Carol a greeting card from the store, motivated only by her fascination, and later lies to her boyfriend Richard, telling him, “she left her billfold on the counter and I took it to her, that’s all.” The filmmakers chose to have Carol leave her gloves so that Therese could have a reasonable excuse to get in touch with Carol; indeed, the gloves symbolize the potential communicative power of the fingers and the hands to touch another person both literally and figuratively. Highsmith thematizes this power of touch in the opening of the novel when Therese recalls her attempts to connect with unresponsive people “who never touched a string that played” and who give a blank look “when one tried to touch a live string.” This symbolism of responsive physical touch permeates the novel and the film too.

Highsmith often mentions Carol’s hands in describing what Therese notices about the body of this woman she loves. When Carol is holding a cigarette lighter, Therese sees “the slim hand with the oval red nails and a sprinkling of freckles on its back.” As Carol drives, “Therese looked down at the faintly freckled fingers that dug their strong cool tips into her palm.” We are told that “Carol’s hands were strong, and they moved with an economy of motion,” but they are also gentle, as when “Therese looked at Carol’s hand, the thumb and the tip of the middle finger resting on the thin rim of the candlestick, as she had seen Carol’s fingers on the saucers of coffee cups in Colorado, in Chicago, in places forgotten.” When Therese feels revulsion towards other characters, Highsmith also mentions their hands: a woman in the cafeteria whose “plump, aging hands” are chapped, with “dirt in the parallel creases of the knuckles,” or Mrs. Robichek’s “stiff” hands that seem “trembling and importunate” (and later, “her dry, rough-tipped fingers pressed against Therese’s arms”). Richard’s “thick,” “moist,” “cold” hands touch Therese “in the same inarticulate, blind way if they picked up a salt shaker or the handle of a suitcase,” or with more aggressive intent as “Richard took her hands, pinned her hands to the bed on either side of her” just before he kisses her. There is the desiring touch between the two women as “Therese ran her thumb down Carol’s side, from under the arm to the waist,” or when she wants “to put out her hands, to touch Carol’s hair and to hold it tight in all her fingers.” But even her lover’s touch can be painful at times: “Therese felt the sting of Carol’s thumbnail in her wrist as she released her.”

The film depicts a very erotic tactility when Therese and Carol sleep together for the first time, but it also highlights a more poignant touching in the restaurant scene that frames the story. Leaving soon after Jack interrupts their discussion, Carol places her hand on Therese’s shoulder in a subtle gesture of longing and deep affection. This repeated scene references Brief Encounter, where Alec discreetly touches Laura’s shoulder when he leaves her for the last time in the station cafe. Expressive touch comes to the fore in the pivotal seduction scene of the film, when Therese plays the piano for Carol. In the novel she awkwardly plays a Scarlatti sonata, but in the film she plays “Easy Living,” a song recorded by Billie Holiday. Her playing is another kind of touching that carries a powerful emotional charge. “It was suddenly too much, her hands on the keyboard that she knew Carol played,” Highsmith writes, “and the music that made her abandon herself, made her defenseless. With a gasp, she dropped her hands in her lap.” Carol, meanwhile, comes to the piano and places her hands on Therese’s shoulders as she plays, saying “That’s beautiful.”

In both the novel and film Therese is a quintessential “piano girl,” innocent and attractive in her piano-playing, feeling the music and her own emotions deeply but unpracticed in the ways of performing her desires for others. Carter Burwell’s soundtrack score conveys this depiction of Therese and her “touching” expressivity through the piano sounds that permeate the background music in many scenes, from the throbbing rhythmic piano chords of the “Opening” main theme to the achingly sparse intervals that resonate into the distance in the “Taxi” and “Train” tracks or the pointillistic notes in the treble like blurred drops on the rain-streaked car window in the cues “To Carol’s” or “Reflections.” In his score Burwell works with the Romantic piano’s symbolism as an icon of romantic desire and attraction or loss and nostalgia. One of the popular songs on the soundtrack also plays into this tradition: Jo Stafford’s “No Other Love” (1950) based on Frederic Chopin’s Étude in E major, op. 10 no. 3.

Throughout this film, piano sounds pulse with a sense of the feeling touch that we know makes those sounds, whether we watch Therese’s fingers stroking the keys while Carol puts her hands on her shoulders or we hear in the background music the kind of sounds that we associate with someone’s fingers (or perhaps our own) playing the instrument. The tactility of the piano’s expressivity fits in perfectly with the hands and gloves and touching in this romantic love story.

Featured image: Scene from the film Carol. (c) The Weinstein Company.

The post Carol: a “touching” love story both literally and musically appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers