Oxford University Press's Blog, page 566

December 31, 2015

Top ten OUPblog posts of 2015 by the numbers

On Tuesday, we shared our editors’ selections of the best of OUPblog publishing this year, and now it’s time to examine another measure: popularity, or in our case, pageviews. Our most-read blog posts of 2015 are… not published in 2015. Once again, Galileo, Cleopatra, antibiotics, and quantum theory dominated our traffic, and of our publishing this year, none of our most-trafficked articles made the editors’s picks. (This is something of a pattern. When we compiled our selections of the best of OUPblog’s publishing for our tenth anniversary, only one of the articles was in our list of top articles in terms of traffic.) Here’s the list of our top article published in 2015 in terms of number of pageviews.

#10 Women in Philosophy: A reading list

A reading list of key feminist and female philosophers

#9 Does philosophy matter?

The Philosophy in Action series editor speaks about the importance of philosophy

#8 The impossibility of perfect forgeries?

Although perfect forgeries might well be possible, we can never know, of a particular object, that it is a perfect forgery

#7 Four myths about the status of women in the early church

Author Susan Hylen discusses common myths concerning women and the church

#6 Ten myths about the French Revolution

Marisa Linton, author of ‘Choosing Terror’, debunks ten of the most pervasive myths regarding the French Revolution

#5 Seeing things the way they are

John R. Searle discusses the tough philosophical questions surrounding perception.

#4 Does a person’s personality change when they speak another language?

Arturo Hernandez on language, culture, memory, context — and personality changes

#3 The Ku Klux Klan in history and today

David Cunningham talks about the most common questions he gets as a Ku Klux Klan scholar

#2 Our exhausted (first) world: a plea for 21st-century existential philosophy

Kierkegaard’s diagnosis of our age (originally of his ‘early 19th-Century backwater of Europe’ age, but plus ça change…) is correct: we are failing to think in the right way about the demands of subjectivity, and indeed what it is to be a subject.

#1 10 academic books that changed the world

Which academic books do you think had the biggest impact on the world?

Featured image: Desk. Photo by Rayi Christian Wicaksono. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Top ten OUPblog posts of 2015 by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Traveling to provide humanitarian aid: lessons from Nepal

Just before noon on 25 April 2015, a violent 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Nepal, killing almost 9,000 people and injuring more than 23,000. Hundreds of aftershocks followed. Entire villages were razed, destroying communities and leaving hundreds of thousands of people homeless. Relief quickly began pouring in from countries around the world, in the form of supplies, equipment, and humanitarian aid workers.

As is often the case after a devastating natural disaster, the brave people who arrived to provide aid were themselves at risk for illness and injury. Doctors, nurses, and other health professionals traveling to provide care for victims after a natural disaster must carefully plan and prepare to stay healthy and safe while providing lifesaving care under extreme circumstances. Without adequate preparation, humanitarian aid workers may not be able to effectively care for those in need or may unintentionally place additional strain on local services.

First, aid workers must realistically assess their fitness level for this work, as well as safeguard their own health while they travel. Aid workers must be in excellent physical health to work in a stressful and demanding environment. Health care facilities are often strained beyond capacity in a natural disaster, and aid workers who become sick or injured will divert limited resources (or may not be able to get care at all). Travel health and medical evacuation insurance should be a strong consideration for aid workers in disaster zones, should they need to be evacuated to a facility where definitive care is available.

Aid workers must be resilient, flexible, and able to improvise. In Nepal, landslides obliterated road access to many remote villages, and workers and supplies had to be delivered by helicopter. Stories abound of aid workers that had to insert a catheter by candlelight or suture wounds with only a little iodine to sterilize instruments.

Pretravel research, care, and preparation are essential for aid workers going to disaster zones. They should be up-to-date on all routine vaccines and receive any travel vaccines recommended for the destination. Malaria prophylaxis is recommended for some destinations, and people going to high altitudes should consider prophylaxis against altitude illness. Aid workers can research these and other travel health recommendations on the CDC Travelers’ Health website.

Aid workers should also prepare a travel health kit that is more extensive than a typical kit. It will most likely need to include supplies or equipment to disinfect water, since safe water is often unavailable after a disaster. It may also need to include gloves, gowns, and goggles if sufficient personal protective equipment will not be available at the disaster site. Aid workers may also wish to carry a supply of calorie-dense, non-perishable food in case of emergency. Those who require medication for a preexisting condition should bring an ample supply, taking into account the possibility of travel delays.

Finally, mental health is an underappreciated aspect of providing care in a disaster zone. Providers often work long hours in extreme conditions and are exposed to profound suffering. These experiences can lead to depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and anxiety. Before deploying, aid workers should think about coping strategies; after deploying, they should stay in touch with a support network of friends and family as much as possible. Those who have witnessed mass casualties may wish to consider counseling after they return.

Nepal is rebuilding, but the road to recovery will be long and challenging. The Nepalese people are committed to restoring their communities and lives, and the contributions of humanitarian aid workers are essential to this recovery.

Featured image credit: “USAID DART Searches Collapsed Structure in Bhaktapur, Nepal” by the U.S. Department of State. Public domain via Flickr.

The post Traveling to provide humanitarian aid: lessons from Nepal appeared first on OUPblog.

Terrorist tactics, terrorist strategy

For the past decade I have been studying representations of terrorist violence in literature, and especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Britain and France. Terrorism in the early modern world was rather different from terrorism today. In the first place, there wasn’t any dynamite or automatic weaponry. It was harder to kill. In the second place, the idea of killing people indiscriminately, without regard to their identity, didn’t seem to occur to anyone yet. But still, there was lots of violence using terrorist tactics, and there was lots of writing – and worrying – about it.

Of course, there was no word for terrorism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The word terrorism, in the modern sense of an act of violence intended to convey a political message and thus alter a society’s power relations, was not current until the nineteenth century. Political conspirators usually understood that they were trying to change their societies through a swift and signal act of violence – an assassination, a staged execution, an act of sabotage, a mass murder – but they could not be and were not called “terrorists”. Nor could any perpetrators think of themselves as being involved in a strategy of terrorist agitation. Every major case of violence was unique, the deployment of a tactic that seemed to fit the needs of the moment, and seemed to belong to no set category of political action.

One of the things the early modern situation tells us today is that we have to be very careful distinguishing between the tactics of political violence and something more general that might identified with a long term goal of terrorization. No one in the early modern period ever espoused such a thing, or a strategy equal to carrying it out. The detractors of terrorist violence were similarly limited. They could excoriate evil when they saw it, but only with great difficulty could they come to terms with something like a strategy of evil. Often they pooh-poohed the idea.

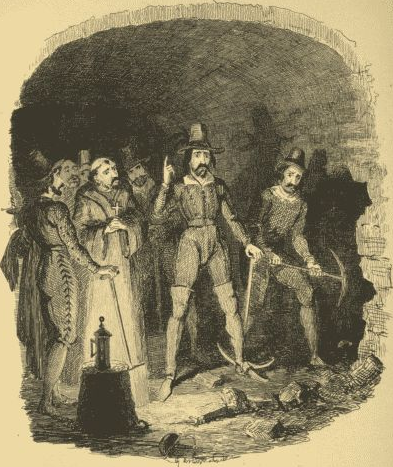

Guy Fawkes and the other Conspirators alarmed while digging the mine. Made by George Cruikshank (1792-1878). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Guy Fawkes and the other Conspirators alarmed while digging the mine. Made by George Cruikshank (1792-1878). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The most notorious case of terrorist violence in English history was the abortive Gunpowder Plot of November 1605 — an incident that brings up very starkly the difference between tactics and strategies. Literally hundreds of pages were written about it over the years. It inspired plays by William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Thomas Middleton, and Thomas Dekker. Dialogues in verse, narratives in verse, some satirically aimed against the folly of the conspirators, some celebratory of Britain’s victory in having escaped the Plot by providential intervention, appeared regularly for years to come. The young John Milton wrote a long poem in Latin about it. Catholic priests wrote memoirs of the event. Protestant ministers wrote and recited Gunpowder sermons once a year from the pulpit. As late as the 1680s the legacy of the Plot was a common literary topic, sure to arouse patriotic outrage at a dastardly bit of treason.

The Gunpowder conspirators were extremely angry at what they considered to be repressive policies. The open practice of Catholicism in England had been illegal for years, and the men, all of them devout Catholics, believed that ever more repressive measures were soon to pass into law, finishing off their faith in England once and for all. The conspirators felt they had no choice but to act, and act now. And so they came upon a terrific tactic. With thirty-six casks of gunpowder stored beneath the House of Lords, in one blow they would murder most of the royal family, along with hundreds of others – parliamentarians, aides, visitors, including foreign dignitaries. Nothing would ever be the same again.

Surely the conspirators were right about that. But their strategy was terrible. They thought that their tactic, successfully executed, with such massive destruction, would trigger a revolution and bring England back to Catholicism, in league with Spain, France, and the Papacy. But it is very unlikely that their aims would have been successfully achieved over the long term. Very few people, including English Catholics, were happy about the idea once it was discovered. Not even Catholic foreign governments were happy about it. And none of them had plans in hand to arm themselves and invade England. Spain in fact was eager for peace with its Protestant rival.

The conspirators, in short, were ready to die for their cause, and to bring about the deaths of many others. But they weren’t ready to bring about the kind of revolution they wanted. They didn’t have the backing. They didn’t have the means. Fortunately, many writers and politicians, including King James himself, recognized this failing. Although in the short term some anti-Catholic hatred was stoked in the aftermath of the plot, writers and politicians of the time consistently distinguished between what the conspirators felt they had to do and what they could have reasonably achieved. The Gunpowder Plot was put down as a terrible error. A misreading of the meaning of Christianity was part of it, and of certain Catholic doctrines perhaps – but only among those for whom a misreading of something even deeper could have incited violence: a misreading of what it means to be human. That is what Shakespeare’s Macbeth among other texts has to teach us. Don’t mistake a tactic undertaken out of delusion for a strategy undertaken out of a plausible desire to change the world. Some writers, especially later on, insisted that the conspirators must have in league with something like the devil, and must have been well along in a strategy of destroying the Protestant faith. But during the crisis and its immediate aftermath cooler heads prevailed. The best defence against the power of a delusion, people from King James to Shakespeare seemed to agree, is not to be deluded oneself.

Featured image credit: The Gunpowder Plot conspirators – Warhafftige Beschreibung der Verrätherey (1606). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Terrorist tactics, terrorist strategy appeared first on OUPblog.

December 30, 2015

Etymology gleanings for December 2015

I often refer to the English etymological dictionary by Hensleigh Wedgwood, and one of our correspondents became seriously interested in this work. He wonders why the third edition is not available online. I don’t know, but I doubt that it is protected by copyright. It is even harder for me to answer the question about the changes between the second and the third edition. Most unfortunately, few lexicographers of old said anything about the revisions they made from year to year. Whenever I write an etymology, I have to open all the editions of Webster, Wedgwood, Kluge, and others, for who knows: what if the treatment of the word I need has changed? This is a long and often frustrating process. Sometimes my efforts yield worthwhile results; other times they are wasted. With regard to Wedgwood, my general impression is that the main alterations are between his First and Second, and even those are few. His dictionary is admired by those who trace multiple words to sound symbolism and sound imitation. The role of those factors in word formation is great, but beware of his shortcuts! He is indifferent to regular sound correspondences, strings look-alikes from Basque and Finnish to English in cavalier fashion, and is not interested in how a word changed in any given language. Even if Latin plumbum is in some general way akin to Engl. plop and if blunt has something to do with such words (see my post on it), we still have to find out how blunt acquired its present form, when it appeared in English, and whether it is native of borrowed. To know Wedgwood’s opinion is always interesting and sometimes useful. However, even if he is a good servant, he is a dangerous master.

Different editions of an etymological dictionary are sometimes hard to distinguish.

Different editions of an etymological dictionary are sometimes hard to distinguish.Linguistic Mythology

I received the following question: “A […] friend of mine told me that the sound ts is very ancient and is the source of many words that now have only t. Is this right?” I am the constant recipient of similar queries and always wonder about their sources. Who could propose that old ts changed to t in many words and even offer this statement as a kind of universal law? No, the idea of our correspondent’s friend is wrong. On the contrary, ts, as in German Katze “cat,” is a composite sound. In the classification of consonants, it is called an affricate. Some other affricates are ch, as in English chick; (d)ge, as in Engl. bridge, jam, and gentle; and pf, as in German pfui (an interjection). They are the product of late development: t to ts; t and k to ch; p to pf, and so forth. Affricates are occasionally simplified and again become p, t, and k, but this is the end, rather than the beginning of a long way.

Etymology also suffers from the grapevine. A popular but fanciful opinion becomes part of common knowledge. Anyone curious about the origin of our slightly overused F-word must have encountered several ingenious hypotheses that have nothing to do with its real history. Another such mishandled word is tip “gratuity.” My omnivorous database absorbs not only scholarly articles on the history of English words but everything that comes to my mill, for a bibliography is like a telephone book: anyone with a telephone has to be entered into it, regardless of the person’s virtues or lack thereof. Among the publications on the economic value of tipping or, conversely, about its drawbacks, I ran into two articles published in New York: one in Everybody’s Magazine 16, 1907, 209-213, the other in The Survey 47, 1921-22, 533-38. Both began with the authoritative statements that tip is an acronym of To Insure Promptness. No doubt, boxes with such an inscription did stand in restaurants, but T.I.P. was a witty decipherment of tip and has nothing to do with the word’s origin. Of course, “everybody knows” where tip came from? No, no one really does. I once wrote a post on the etymology of tip.

Mind our tip: the word tip has nothing to do with insuring promptness. Anyway, tip it is now called gratuity or even more euphemistically service.

Mind our tip: the word tip has nothing to do with insuring promptness. Anyway, tip it is now called gratuity or even more euphemistically service.From My Trashcan

Interesting cases of multiplying by division

From the Department of Public Safety website (quoted in the Star/Tribune, Minneapolis, 15 November 2015): “In very cold weather a person’s body can loose (sic) heat faster than they can produce it.” Very true: in cold weather, one body is bad, two bodies are worse. The writer was of course misled by the recollection of somebody and person, and a person, one would think, is always they. But, as most people learned in their childhood, don’t generalize! Cass Sunstein, Bloomberg View, says: “If a person were to say ‘the U.S. government should be overthrown’ or ‘the more acts of terrorism, the better’ or that ‘all Muslims should join ISIL’, she could not be punished unless those statements were likely to produce imminent lawless action.” Cass is a unisex name, so I don’t know whether Cass Sunstein is a man or a woman, but I am so happy that s/he could not find a single male person ready to issue such terrible statements even for the sake of the First Amendment. I feel relatively more comfortable in the presence of Mr. L. W.: he finds it hard to believe that “‘an informed voter’ would put their trust in a candidate who is only viewed as trustworthy by just over 30 percent of a sample group.” I certainly wouldn’t.

There is a website called Academia.edu. It allows people to download scholarly papers and do other useful things. Recently I have read that Mr. X downloaded their paper (title given). Poor Mr. X, a man suffering from multiple personality disorder or with himself at war! People have been stultified by political correctness to such a degree that I once read (and quoted in a very old post) the sentence: “If John calls, tell them I am not at home.”

From the BBC article (10 November 2015) “Fit Legs Equally Fit Brain Study Suggests,” sent me by Peter Maher: “Generally, the twin who had more leg power at the start of the study sustained their cognition better and fewer brain changes associated with ageing after 10 years.” Here the plot thickens considerably: twins can be male or female, or one can be male, the other female (or vice versa), and even identical twins can be, if I remember correctly, of different sexes. Are pluralized twins whose sex is unknown to the writer called quadruplets, or is there a disease called singularophobia?

All the New’s That’s Good to Print?

From the New York Times: “Russia, Turkey risk spit over plane. Russia prepares to sever its economic ties as both nation’s leaders stoke confrontation.”

I have received a few interesting questions but will answer them in January, because I wanted to finish 2015 on a light note. We, your obedient servant The Oxford Etymologist, thank those who read the blog in 2015, commented on it, and sent questions. May 2016, though a leap year, bring all of us a modicum of peace and relative quiet.

Image credits: (1) Toggle wall calendar. (c) mars58 via iStock. (2) Watching the ducks. (c) XKarDoc via iStock. (3) Glass bank for tips. (c) vinnstock via iStock.

The post Etymology gleanings for December 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Can one hear the corners of a drum?

Why is the head of a drum usually shaped like a circle? How would it sound if it were shaped like a square instead? Or a triangle? If you closed your eyes and listened, could you tell the difference? The mathematics used to prove that “one can hear the corners of a drum” are founded on the study of two everyday phenomena: vibrations and heat conduction. These phenomena can be described by two mathematical equations, in the sense that if one can solve these equations, then one can predict the behavior of vibrations and heat conduction.

At the heart of both of these equations is the Laplace operator, ∆, also known as the Laplacian, named for Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (1749-1827). It turns out that if one can solve the Laplace equation: ∆f = λf, then one can solve both the wave and heat equations.

It is not necessary to understand these mathematical symbols and jargon because they are connected to something everyone understands: music. The sound produced by a stringed instrument is made by the vibration of the strings. The note one hears, such as an A, C, or B-flat, depends on how long the string is, and of what material it is composed. This note is also referred to as the fundamental tone or fundamental frequency.

Bass Guitar by egonkling, Public Domain via Pixabay.

Bass Guitar by egonkling, Public Domain via Pixabay.The vibration of the string also produces overtones, known as harmonics, and these play an important role in creating the sound we hear. The collection of values obtained from solving the Laplace equation provide all these different frequencies: the fundamental frequency and all of the harmonics. Altogether these determine the sound of the string.

In the case of a string, the Laplace equation can be solved rather easily, and it turns out that all the harmonics are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. This mathematical fact is one of the reasons that stringed instruments and pianos are so popular: it causes the sound that we hear from such instruments to have a pleasant and “clean” quality. In fact, every other instrument in a classical orchestra also has this property, with the exception of the percussion instruments.

Drums are fundamentally different. The sound created by beating a drum comes from the vibrations of the drumhead. Mathematically, this means that the Laplace equation is now in two dimensions. Acoustically, you may observe that the sound produced by vibrating drums is “messier” in a certain sense as compared to the sound produced by a vibrating string. The reason is that for drums it is no longer true that the harmonics are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency.

Although we can mathematically prove the preceding fact, we cannot, apart from a few notable exceptions, solve the Laplace equation in two dimensions. Facing this impasse, mathematicians have turned to investigate questions such as: if two drums sound the same, in the sense that their fundamental frequencies as well as all their harmonics are identical, then what geometric features do they have in common? Such features are known as geometric spectral invariants.

Figure 1: Identical sounding drumheads. Used with the permission of the authors.

Figure 1: Identical sounding drumheads. Used with the permission of the authors.Hermann Weyl (1885-1955) discovered the first geometric spectral invariant: if two drums sound the same, then their drumheads have the same area. About a half century later, Åke Pleijel (1913-1989) proved that the perimeters of the drumheads must also be the same length. Shortly thereafter, M. Kac (1914-1984) wrote the now famous paper, “Can one hear the shape of a drum?” He wanted to know whether or not the drumheads must have the same shape? It took about a quarter century to solve the problem, which was achieved by Carol Gordon, David Webb, and Scott Wolpert in 1991. The answer is no.

In contrast to a nice round drumhead, the “identical sounding drums,” in Figure 1 both have corners. A natural question is therefore: can one hear the corners? This means, is it possible for two drums to sound the same, and one of them has a nicely rounded, but not necessarily circular, shape, whereas the other has at least one sharp corner? In other words, can one hear the corners of a drum? We have proven that the answer is yes. The sound produced by a drumhead with at least one sharp corner will always be different from the sound produced by any drumhead without corners. Mathematically, this marks the discovery of a new geometric spectral invariant.

Inquiring minds still have several questions to investigate. For example, if we now assume that both drums have nicely rounded, not necessarily circular shapes, and no sharp corners, is it possible that they can sound identical but be of different shapes? Can one hear the shape of a convex drum? What happens when we consider these types of problems for three-dimensional vibrating solids? We continue to work alongside our fellow mathematicians on problems such as these, and there is plenty of room for further investigation by young researchers.

Image credit: Drum by PublicDomanImages, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Can one hear the corners of a drum? appeared first on OUPblog.

New Year’s Eve fireworks cause a mass exodus of birds

As the days get shorter, the Netherlands, a low lying waterlogged country, becomes a safe haven for approximately five million waders, gulls, ducks, and geese, which spend the winter here resting and foraging in fresh water lakes, wetlands, and along rivers. Many of these birds travel to the Netherlands from their breeding ranges in the Arctic. Many of these wetlands are part of the European Natura2000 network, which is an initiative that aims to assure the long-term survival of Europe’s most valuable and threatened species and habitats.

Every New Year’s Eve the people of the Netherlands, like many countries around the world, seem to be taken over by a fireworks frenzy. People are allowed to light their own fireworks on New Year’s Eve and they do it with great zeal. It has become anintegral part of New Year’s celebrations, with an estimated 10.8 million kg of fireworks ignited each year. While the negative impact of fireworks on public health is often discussed in the media, the potential negative impact on wildlife is rarely considered.

Over the last several years, ecologists at the Royal Netherlands Air Force have been registering unusual flights of thousands of birds on military surveillance radar on New Year’s Eve, with birds appearing to flee in response to New Year’s Eve fireworks. These bird movements are monitored by radar in order to develop forecast models of bird migration, and provide near real-time warnings to alter flight planning and reduce the risk of collisions between birds and military aircraft. In 2010 a multi-disciplinary team, with researchers from the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) and the Royal Netherlands Air Force (RNLAF) got together to carefully document the reaction of free living birds to fireworks on New Year’s Eve for the first time, and try to quantify the number of birds involved.

This study found that each year on New Year’s Eve, birds alight from water bodies en mass just after midnight and climb to altitudes of 800 metres above the ground surface. These altitudes far exceed any these birds would usually reach during local flights, and are in fact comparable to flight altitudes measured during migration. Birds fleeing to these unusual heights appear to remain there for up to 45 minutes in dense flocks, and it is likely that these flights are energetically quite costly and stressful for the birds. It is an unexpected investment in flight and birds then the need to resettle somewhere safe in the middle of the night. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of birds take flight, just within a 40 kilometre radius of where the radar was taking measurements. If we consider the entire country using this statistic, millions of birds could be affected. These figures are quite staggering, especially when considering that birds are disturbed from areas that are otherwise designated for conservation of the species, especially during the winter and migration season. This phenomenon has also been observed in Belgium, so this issue is clearly not isolated to the area where this particular study took place.

Greater white-fronted geese, by Gregory Smith. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Greater white-fronted geese, by Gregory Smith. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.While the long term impact of these findings on birds is not yet clear, journalists and policy makers would like a decisive answer to the question, “what is the impact on the birds, and is this a serious problem?” However the answer to such a question is still elusive. Based on the flight behaviour that’s been measured, it is clear that there is an immediate energetic cost for the birds while sleep or foraging activities may be disrupted. While we do not expect that these evasive flights are generally life threatening, there may be other indirect effects. For example, immune capacity could be reduced, which might increase the risk of acquiring diseases or the ability to deal with harsh weather conditions. Furthermore, there could be physiological costs resulting from a stress response to fireworks.

Occasionally, the evasive response in combination with adverse weather conditions reducing visibility, or flight capacity, could have detrimental results ending in collisions with static objects in the landscape or with aerial vehicles, for example. This was observed in a recent report about red winged blackbirds seemingly falling out of the sky in Beebe, Arkansas, due perhaps to similar circumstances, and showing that occasionally such a response can be deadly. Direct and indirect impacts aside, we have seen that birds, just like dogs and cats and perhaps many other animals can have an acute response to fireworks and do their best to flee from this perceived threat. The observations in the Netherlands are perhaps extreme due to the high concentrations of birds found in waterbodies in the winter and the close proximity of human activity, and we can expect responses on such a grand scale in other parts of the world where conditions are similar. Initiatives such as the European Network for the Radar surveillance of Animal Movement, could help elucidate the scope of such problems in the future, while the use of radar remains an extremely powerful tool to reveal aerial behaviour that would otherwise remain invisible.

Featured image credit: “Fireworks” by jeff_golden. CC by SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post New Year’s Eve fireworks cause a mass exodus of birds appeared first on OUPblog.

December 29, 2015

Atoning for the Wounded Knee Massacre: General Nelson A. Miles and the Lakota survivors’ pursuit of justice

Today, 29 December 2015 marks the 125th anniversary of the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, when the US Seventh Cavalry killed the Lakota Chief Big Foot and more than two hundred of his followers in South Dakota, ostensibly for their adherence to the Ghost Dance religion. In the years since 1890, Wounded Knee has become one of the most contested events in American history, with the US Army claiming it was the final heroic victory in the 400 year “race war” between civilization and savagery, while the Lakota survivors argued that it was a horrific massacre. For three decades after Wounded Knee, the most prominent advocate for the survivors’ compensation claims was army general Nelson A. Miles, who, ironically, also created the tense environment that preceded the massacre. What explains this contradiction?

As the Ghost Dance spread through Native American communities in the American West during the late 1880s, Miles was assigned to investigate the new phenomenon for the War Department. Miles wrote alarming reports describing a vast Indian conspiracy, which, if not checked, would lead to the greatest Indian war in the nation’s history. Acting on the commander’s reports, the war department sent 7,000 troops to maintain control of the Lakota reservations in North and South Dakota, avert the feared uprising, and protect neighboring settlements. It was also Miles who issued the fateful order commanding the US Seventh Cavalry to apprehend Big Foot—who Miles believed was a “hostile” Ghost Dancer—and disarm his followers. If the Lakota chief resisted, Miles authorized the cavalrymen to “destroy him.”

When the Seventh Cavalry captured Big Foot at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, the troops found a pneumonia-stricken chief with his cold and frightened followers. Big Foot explained that he was not a hostile, but instead was trying to meet with other chiefs to arrange a peaceful solution to the crisis with the soldiers. When the troops moved to disarm Big Foot’s warriors, a deaf and confused Lakota fired his gun into the air, a shot that led the troops to unleash overwhelming force onto the bed-ridden chief and his fleeing people. More than 200 Lakota men, women, and children died that day. Later, one of the cavalry’s defenders argued that the soldiers had simply followed Miles’s orders.

Nelson A. Miles in 1898. Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Nelson A. Miles in 1898. Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia CommonsRather than praise the Seventh Cavalry for following his orders, however, Miles condemned Wounded Knee as “the most abominable military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children.” He relieved the Seventh Cavalry’s colonel, James W. Forsyth, from command and instituted a military court of inquiry. Despite strong discouragement from top War Department officials, who ordered Miles to discontinue the investigation, the general doggedly insisted that the inquiry would continue. Why did Miles pursue this course? One possible answer is that the general knew that his rhetoric and orders had contributed to the tense atmosphere that led to the massacre, and he may have believed that the Forsyth inquiry would deflect attention from Miles himself. While there is likely some truth to this, it is also true that for decades prior to 1890 Miles had been on record as opposing the excessive use of violence when dealing with Native peoples. He had long advocated negotiation and diplomacy rather than massacre to resolve difficulties with Indians. When viewed from this perspective, Miles’s actions after Wounded Knee come into focus.

Ultimately, Miles was unable to control the outcome of the court of inquiry. Based primarily on testimony from Forsyth’s own officers, the court exonerated the colonel. The War Department restored Forsyth to his command, awarded 20 Medals of Honor to his troops, and erected a monument to honor the soldiers killed at Wounded Knee.

Although Miles had lost the struggle over the meaning of Wounded Knee in 1891, he would subsequently emerge as the Lakota survivors’ most prominent champion as they pursued justice for the wrongs committed against them. In the years following 1890, brothers Joseph Horn Cloud and Dewey Beard had led the survivors’ engagement in the politics of memory. Horn Cloud and Beard had lost their parents, two brothers, and a niece at Wounded Knee. Beard also lost his wife and newborn child, aside from sustaining multiple gunshot wounds. Relying on Horn Cloud’s literacy, the brothers had erected a monument in honor of Big Foot’s people at the Wounded Knee mass grave, had dictated several accounts to sympathetic whites describing the killings, and had filed multiple claims seeking compensation from the government.

In the late 1910s, Horn Cloud and Beard sought Miles’s assistance in hopes that his prominence would help their cause. Miles obliged, asking the federal government “to atone in part for the cruel and unjustifiable massacre of Indian men and innocent women and children at Wounded Knee.” Miles’s advocacy led to government investigations in 1917 and 1920, in which bureaucrats recorded dozens of statements from the remaining survivors. Although the 1920 inquiry concluded with a modest proposal that the government compensate the Lakotas $20,000 for property stolen from the killing field by artifact seekers, the government took no action.

Miles passed away in 1925 without seeing justice awarded to the Lakotas. His advocacy for the survivors’ claims was doubtless a result of his longstanding opposition to the use of excessive force against Native peoples. Yet his support for the Lakotas may have also been motivated by a desire for redemption for his role in the events leading to the massacre. Whatever his motivation, Miles’s comments on Wounded Knee would subsequently be quoted in the halls of Congress in support of bills designed to “liquidate the liability of the United States” for the massacre. These bills did not ultimately become laws, but Miles’s words in favor of the Lakota survivors continue to call upon the nation to atone for the wrong committed at Wounded Knee.

Featured image: Burial of the dead at the battle of Wounded Knee, S.D. (c1891 Jan. 17). Northwestern Photo Co. (Trager & Kuhn) Chadron, Neb. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post Atoning for the Wounded Knee Massacre: General Nelson A. Miles and the Lakota survivors’ pursuit of justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Complicating Rosie the Riveter

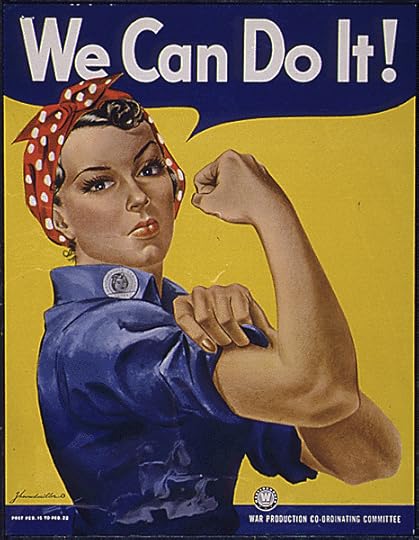

The roles of American women during World War II were much more complicated than the iconic Rosie the Riveter image suggests. The popular poster does, however, serve as an intriguing starting point for discussing a more complex history, one which reveals ongoing attempts by those in authority to rein in disruptive and unruly women.

The Rosie image itself—the J. Howard Miller “We Can Do It!” poster—wasn’t created to celebrate the female factory workers that Americans were already referring to as Rosie the Riveter. The Westinghouse Electric Company hired Miller in 1942 to create posters that would discourage its workers from skipping their shifts and from organizing strikes. One of Miller’s posters featured 17-year old Geraldine Hoff Doyle, who was working as a metal presser in a Michigan defense factory when a UPI wire service photographer snapped her picture.

Miller’s illustration, based on that photo, emphasized Doyle’s beauty rather than her skills. There are no tools or equipment in the image, only a lovely young woman with a look of pride and determination on her face. The poster, with its slogan “We Can Do It!” was displayed in-house at Westinghouse for two weeks in February 1943. It didn’t become associated with Rosie the Riveter until several decades later, after the postwar women’s movement pushed along the changes in women’s lives that had begun during the war. Since the 1980s, Miller’s Rosie image has been reproduced on everything from coffee mugs to mouse pads.

Image Credit: “Rosie the Riveter” by War Production Board. Public Domain via The National Archives Catalog.

Image Credit: “Rosie the Riveter” by War Production Board. Public Domain via The National Archives Catalog.During the war years, the image of Rosie the Riveter that Americans were most familiar with appeared on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1943. Using a photograph of a petite red-haired telephone operator named Mary Keefe as his model and inspired by Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling painting of the prophet Isiah, Norman Rockwell drew a muscular female riveter surrounded by the tools of her trade, her foot resting nonchalantly but firmly on a copy of Mein Kampf while she ate a sandwich from the lunchbox that bore her name, Rosie. The illustration was used throughout the rest of the war to promote war bond sales, serving as a reminder that this gender role change (and the resulting masculinized features) were only for the duration of the war.

Miller’s poster, featuring an attractive young woman and boasting the zippy “We Can Do It!” slogan, presents a comfortable, comforting image of how Americans prefer to remember women’s contributions to the war. It’s too complicated to remember why the real reason the poster was created in the first place: women weren’t submissive, obedient workers. They didn’t behave like “proper” women.

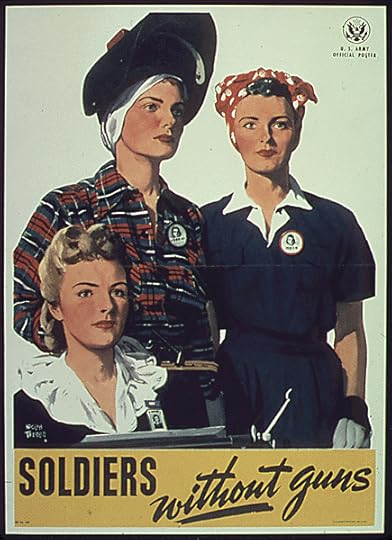

The real Rosies of World War II—almost all American women, in fact—challenged existing gender conventions at every turn. For the first time in their lives, millions of women heeded the call to step into the work force for reasons that included but were not specific to patriotism. In general, those jobs provided more opportunities, independence, and pay than peacetime employment. They understood the value of their labor and expected to be treated and paid accordingly. Yet at work women endured sexual harassment from male co-workers who resented their presence and their competence. Women of color encountered the racial discrimination endemic in American society, and were often not hired for well-paying factory jobs despite the great need for labor.

Image Credit: “Soldiers without Guns” by War Production Board. Public Domain via The National Archives Catalog.

Image Credit: “Soldiers without Guns” by War Production Board. Public Domain via The National Archives Catalog.Race also dictated assumptions about patriotism. Thousands of women of Japanese descent living on the West Coast never had the chance to work at a war production factory. Instead, they were compelled to demonstrate their loyalty to the US government and prove they weren’t security threats by submitting to internment for the duration of the war. They were reminded over and over that they couldn’t be “real” Americans, despite having been born in the United States, because their ancestors were from Japan.

As women changed their lives to meet the realities of a wartime society, businesses reminded them of their traditional roles. Every day women were barraged with advertising images that linked the ideals of beauty and femininity (increasingly identified as white, young, and middle-class) to patriotism. To be a good American woman during the war meant using certain cosmetics and buying particular clothes to please the man in your life. Fears that women exercised too much control over their own sexuality while their men were off fighting the war resulted in public campaigns to shame “Victory Girls” and force them to get tested for sexually transmitted diseases.

Allowing women the traditionally male prerogative of demonstrating their patriotism through military service also upset the gendered status quo during the war. As women joined the newly created Women’s Army Corps, their sexual lives were scrutinized by politicians and military officials who worried that WACs were either over-sexed heterosexuals or “deviant” lesbians. Some of these women, especially the military nurses who served overseas, were celebrated as heroines or as angels for the sacrifices they made to tend to sick and injured soldiers. Emphasizing the angelic nature of the overseas nurses’ work diverted attention from the fact that they were at or very close to the front lines, areas which traditionally marked the dividing line between men’s military duties and women’s civilian, domestic ones.

Throughout World War II, American women crossed dividing lines, whether on the job in a factory, at home with their families, out in public socializing, or in uniform to work for Uncle Sam. They challenged gender conventions and succeeded in changing their own lives. To understand all of that, we have to critically examine Rosie the Riveter, not take her at face value.

Image Credit: “Group of Women Service Air Force Service Pilots and B17 Fortress Flying” by US Air Force. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Complicating Rosie the Riveter appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond the rhetoric: Bombing Daesh (ISIS)

Last week, I wrote about the presidential campaign rhetoric pledging to “carpet bomb” Daesh (ISIS), focusing on what it really means and why it is now generally irrelevant to the problems at hand. Today, I want to return to the present problems in more detail: What can be bombed? To what lasting end? And how has Daesh responded to our bombing thus far?

Always begin with some history. Daesh was born from the remnants of Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) whose surviving members went to ground during the so-called surge campaign in Iraq from 2007 to 2009. AQI survivors selected new leaders to replace the dead, moved their considerable funds into cyberspace, and awaited their next opportunity. Even as the United States withdrew from Iraq, the civil war in Syria heated up, and the combination of chaos and the sectarian cause of ousting Assad drew in Daesh. It initially funded itself from banked reserves, and then, as it became territorially successful in northern and eastern Syria, it expanded revenue operations into extortion, theft, expropriation of property, antiquities sales, “taxation,” and increasingly, oil production and sale—primarily to the population in Syria. Success in Syria led Daesh to invade western and northern Iraq from January to August 2014 which in turn led to a surge of revenue based on smuggling oil from the Ajeel oil fields near Tikrit.

In evaluating Daesh, it helps to lay out the key differences between it and Al-Qaeda. A foundational difference is the former’s insistence that an Islamic state (the caliphate) could and would be achieved in the immediate future, and indeed its leaders formally declared its existence in June 2014. Al-Qaeda had long argued for a future caliphate, but imagined it to be something that would happen much further in the future, for which they were igniting the embers. This difference is important for several reasons. One is that Daesh is now actually a territorial entity, a self-declared state, with its own flag and its own designated sovereign ruler. It controls a large population (somewhere between 3 and 8 million in Iraq and Syria, primarily in large cities), organizes its army into units, collects taxes and enforces law, and notoriously operates a substantial “public affairs” arm via social media. Al-Qaeda was and is a multinational cellular organization, operating from ungoverned spaces, but not in any way dependent on territory or a population base, nor did it mobilize large numbers of fighters. Another difference is that Daesh followers believe they are fulfilling an apocalyptic prophecy and that a final battle will occur when anti-Islam forces are lured into a climactic battle around the city of Dabiq.

All of this is relevant to bombing and presidential campaign rhetoric. What does one bomb to destroy Daesh? In most military strategies you can choose among attacking an opponent’s armed forces, their war making resources, or their will to continue fighting.

Daesh has a military of sorts and that would seem the most obvious target. Bombing it, however, is not as easy as it sounds. Since the destruction of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in 2001, insurgents throughout the world have learned to avoid detection as much as possible. By far the easiest environment in which to do so are cities, surrounded not only by the physical concealment of buildings, but also the humanitarian cover of a large civilian population. When US forces were operating on the ground in Iraq they were capable of calling in very precise firepower (both from the air, from helicopters, and from new forms of precision artillery) and could contain collateral damage relatively well (although never perfectly). Without forces in contact on the ground, air power is a far less certain instrument, however capable of precisely hitting a target. The exact grid coordinate of the right target, right now, is often unavailable. Indeed, when the United States did make mistakes during its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, quite often it was because targeting information was already outdated. The actual enemy had moved on. That sort of real time information requires forces in contact, or, increasingly, constant drone surveillance backed by armed platforms already tasked to the area of operations or mounted on the drone itself. For any of those conditions to exist, air bases need to be in relatively close proximity. Most of Daesh’s operations are occurring deep in the interior of Syria and Iraq, hampering the effectiveness of US bombing (which began in earnest in August 2014) until Turkey opened its airbases to that purpose in July 2015—almost a year later. American bombing, especially when in cooperation with Kurdish or Iraqi Army forces on the ground, has grown markedly more effective. But Daesh, like insurgents throughout history, continues to adapt, learning to hide from airstrikes, disperse its forces, and hide among the people.

Daesh has similarly adapted to air strikes on its war-making resources, in this case primarily their revenue stream, since they don’t “build” things on their own. The first adaptation was simply diversification; something it was doing from the beginning of the organization. US and allied forces are not about to start bombing the taxable population, nor the ancient cities being plundered by Daesh for artifacts to sell abroad. That leaves oil, something that Donald Trump has been trumpeting as what he would “bomb the shit” out of. Effectively bombing oil production, however, has long been a problem. As I mentioned in my last article, the allies in WWII struggled to effectively degrade German oil production, although they did eventually severely damage it. Bombing the oil fields themselves is relatively ineffective; well heads are not good targets; they are easily repaired; and the oil itself is still underground. The most vulnerable link in the chain of oil production and distribution is the refinery, where the oil is the most concentrated in the most fragile type of facility and where it is also being rendered into something more flammable. (Coincidentally, my father was assigned at the Pentagon to research this problem of targeting oil production back in the early 1980s; the details of such research remain classified, but historical examples make this conclusion clear.) US bombing and Iraqi forces’ actions removed the Ajeel oil fields (and the Baiji refinery) from Daesh hands in October 2015, and whatever oil revenue Daesh is raising now comes from fields in Syria. The Daesh operation may seem relatively profitable by the standards of what the world considers simply a terrorist organization, but in the larger scheme of things it is quite small. Their production is fully consumed by the local Syrian population (it is not being smuggled abroad for sale). Relatively small refineries, built on skids in a modular fashion and shipped in from the manufacturer in crates, can be set up on a very small footprint and are easy to camouflage or simply set up next to civilian facilities. (As an aside, however, I can only assume that US intelligence agencies are working with the manufacturers to identify their thermal signature.) Such modular refineries were apparently a key part of getting the Daesh oil operation in Syria going, although it is now hoped that no more are being delivered. Attacks have also been launched against convoys of oil trucks, to persuade the drivers of the dangers of such a job (such convoys have been leafleted first, and then bombed as the drivers flee).

Attacking Daesh’s will is more complicated, and its will to fight may indeed be its “center of gravity,” the thing most important to sustaining its war effort. Daesh is a low-tech, low-numbers operation, that recruits through international social media by hyping martyrdom and an opportunity for seemingly independent manhood for disaffected youth. What’s worse, its recruitment system hopes to generate independent lone wolf attacks abroad, something that bombing is only likely to make worse (especially when paired with Islamophobic political rhetoric).

So what does all this mean? It means that we are bombing Daesh, and indeed we are hitting all three prospective target types. We have hit some 16,000+ targets with 20,000 weapons at the cost of more than $5 billion. Many of the targets have been explicitly military, and the tempo and effectiveness of our attacks has been increasing in recent months, especially as our Kurdish and Iraqi partners on the ground have stepped up their own operations and we have provided more direct assistance in calling in air power. We have cut off their access to oil from Iraq and are degrading their ability to refine and distribute oil. Finally, we have attacked “will” primarily through targeted attacks on key leaders—both with commando raids and with drone strikes. Nevertheless, and despite the cost, it is as yet unclear whether any of these lines of attack will bring decisive victory. There are many variables in play here, and the history I have given is greatly simplified. But the one thing that should be clear from this discussion is that this is a campaign that requires patience. The conditions simply do not exist for shock, awe, or carpet bombing, however much certain candidates might wish to flex their rhetorical muscles.

Featured image: Ruins of Kobane in northern Syria. (c) RadekProcyk via iStock.

The post Beyond the rhetoric: Bombing Daesh (ISIS) appeared first on OUPblog.

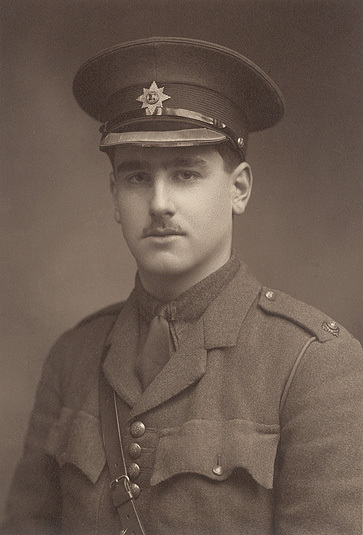

“Our fathers lied”: Rudyard Kipling as a war poet

The privileged poets of the Great War are those who fought in it—Rosenberg, Owen, Sassoon. This is natural and human, but it is not fair. Kipling is one of the finest poets of the War, but he writes as a parent, a civilian, a survivor—all three of them compromised positions. “If any question why we died,/Tell them, because our fathers lied,” he writes. It is widely believed that Kipling was, himself, one of these lying fathers—that his jingoism promoted the War, that his propaganda supported the prolongation of its madness, and that he shepherded—bullied—his only son, John, into the front line, where he died at Loos in 1915. None of this is true, but Kipling’s grief, and the guilt that all survivors feel, have made him an easy target. Of the grief, at least, he made extraordinary art, in stories as well as poems. He writes of bereavement, of compulsive memory, of what we now call ‘post-traumatic stress’, and he knew that we are haunted most by ourselves:

I have a dream—a dreadful dream—

A dream that is never done,

I watch a man go out of his mind,

And he is My Mother’s Son.

He could write about the business of war, too, answering its savage economy with his own:

The ships destroy us above

And ensnare us beneath.

We arise, we lie down, and we move

In the belly of Death.

The ships have a thousand eyes

To mark where we come . . .

But the mirth of a seaport dies

When our blow gets home.

John Kipling in 1915, the year that he died. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Kipling in 1915, the year that he died. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Three soundless dots give us the track of the submarine’s torpedo; when it gets home, we are reminded by a dreadful pun that the sailors on the stricken ship never will. The pity of war? Yes, but its pitilessness, too.

The Garden called Gethsemane

In Picardy it was,

And there the people came to see

The English soldiers pass.

We used to pass—we used to pass

Or halt, as it might be,

And ship our masks in case of gas

Beyond Gethsemane.

The Garden called Gethsemane,

It held a pretty lass,

But all the time she talked to me

I prayed my cup might pass.

The officer sat on the chair,

The men lay on the grass,

And all the time we halted there

I prayed my cup might pass.

It didn’t pass—it didn’t pass

It didn’t pass from me.

I drank it when we met the gas

Beyond Gethsemane!

John Lockwood Kipling and Rudyard Kipling. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Lockwood Kipling and Rudyard Kipling. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I have long thought this the greatest poem of the Great War. Its imaginative empathy is not surprising—Kipling could think himself into almost any human condition, and voice it from within—but the poem has another voice than that of the soldier, or rather Kipling lends him the poet’s masterful tact. Nothing in the poem is overstrained (except, perhaps, the final exclamation mark) yet the whole is unbearable. The soldier’s blank gaze takes in the scene with homely dread, from the ‘pretty lass’ whose words he cannot really hear, to the enduring English comedy of manners by which officers and men each contemplate their death from the proper vantage point. He is Jesus, this young man, praying in the Garden of Gethsemane; but Kipling was not a Christian. When Jesus prays, in Matthew 26: 39, he does so in terms that the poem implicitly rejects: ‘O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me: nevertheless not as I will, but as thou wilt’. Kipling has no nevertheless, no acceptance of God’s will, no embrace of sacrifice. The soldier’s anguish is wholly human.

The craft of words mattered enormously to Kipling. The small word ‘pass’ begins by meaning ‘to pass through’ (the little village), though even here a little chill accompanies it, as ‘the people’, with their curious unconscious cruelty, come ‘to see the English soldiers pass’—pass away, into what lies ‘beyond Gethsemane’. Then the word changes its meaning, burdened by its biblical idiom: ‘I prayed my cup might pass’, that I might be spared; yet ‘my cup’ (altered from Matthew’s ‘this cup’) already tells us that this won’t happen. These two meanings of ‘pass’, apparently unrelated, are joined in the poem by the song-like rhythm of the lines in which they are repeated: ‘We used to pass—we used to pass’ in the first stanza; ‘It didn’t pass—it didn’t pass’ in the last. Here poetry does its utmost, gives everything that can be given by the sounds of words and their cadence, and by that most difficult servant of poets, metrical art. The poem is written in one of the oldest English metres, sometimes called ‘common metre’, an alternating pattern of eight and six syllables which is the foundation of many of our hymns and popular songs. It is the metre of the common man, who speaks here, as he should, with impersonal authority.

Featured Image: Canadian soldiers in a trench, in 1916 during WWI, by Bibliothèque nationale de France. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Our fathers lied”: Rudyard Kipling as a war poet appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers