Oxford University Press's Blog, page 564

January 7, 2016

We should all eat more DNA

2016 is here. The New Year is a time for renewal and resolution. It is also a time for dieting. Peak enrolment and attendance times at gyms occur after sumptuous holiday indulgences in December and again when beach wear is cracked out of cold storage in summer.

As the obesity epidemic reaches across the globe we need new solutions. We need better ways to live healthy lifestyles.

From crazy diets of yore that included the cigarette diet, the cotton ball diet, and the Sleeping Beauty diet (a programme of coma induced weight loss associated with Elvis Presley), it seems every possible caloric manipulation has been proselytized over time.

Luckily, trends are moving towards more sensible diets that stress high nutritional value. Among the most famous is the low-fat diet of the 1980’s, which encouraged us to fill up on carbohydrates, and the Atkins diet that later encouraged us to fill up on protein (i.e. eating our hamburgers without buns). The more recent Paleo diet mimics the food culture of our hunter-gatherer ancestors and is heavy on meats, fruits and vegetables but eschews grains, but whether this is historically accurate is debatable.

Today, science is filling in more details about how our bodies metabolize food and store fat. It could be that any of these diets is best for you. In 2016 it is possible to take ‘healthy eating’ to the next step and optimize diet according to DNA. It is also increasingly apparent that we need to take our microbiomes into account too.

But there is a far more fundamental way that all of us can benefit from paying attention to DNA in deciding what we eat.

Slice of cake, by Blondinrikard Froberg. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Slice of cake, by Blondinrikard Froberg. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.I would like to propose a generic “Eat-DNA Diet” as a healthy life-style guide. It follows one simple tenet:

‘Avoid anything that lacks DNA.’

Humans aren’t designed to eat things without DNA. At the most extreme, this includes toxins, poisons, cleaning detergents – well, the list goes on to span the inanimate universe. In our modern diets this means avoiding refined sugars, fats, preservatives, additives, and bulking agents.

A diet “high in DNA” is a living diet packed with fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts and seeds, grains and meats, and to a lesser extent dairy (only milk will have a bit of DNA, from shed cow cells, and higher fat items like whipped cream will have trace amounts if any). Eating foods rich in DNA cuts processed foods from ones diet. By rule, the more processed a food is, the less DNA it will have so this is a great guideline.

If you need any proof that all living things have DNA you can extract it yourself. This is a staple demonstration at science fairs today. Strawberries and bananas are favourites. Little fingers can mush them easily. Just stick a chunk in a plastic bag, add fairy liquid and squish. Physical force and soap break the cell membranes which releases the DNA. Add high proof alcohol, mix, and watch for the spidery strands of DNA that will appear in the top layer of alcohol. Use a toothpick to swirl your prize up. Even a single strawberry will produce a clump of DNA about the size of an ant. The grown up version of this makes a great cocktail party trick.

Interestingly ripeness plays a role in the quality of the DNA. A ripe banana will give loads but an overripe one won’t. This is because the DNA starts to break apart in the cells as part of the natural process of decay. The DNA is all still there, just broken down, so the extraction doesn’t produce the very long gossamer threads that cling together in this type of extraction. This is a reminder that most animals eat fruits at the peak of ripeness and humans should too.

It’s obvious that salad is a better nutritional choice than a piece of chocolate-fudge cake. The DNA-0-meter agrees: a garden salad will have more DNA, and more diverse DNAs. If totally processed you might be hard pressed to find any DNA in cake except a bit in the flour – more if it is whole wheat, which still contains the wheat germ. But who eats whole-wheat cake? The point is as we optimize for taste, we often strip out DNA.

The word ‘diet’ comes from the Latin word dieta, or “a daily food allowance”. The related diaeta (and Greek diaita) means “a way of life, a regimen”.

The best thing about the “DNA Diet” is that it’s not a fad. It never goes out of fashion. It has been here since life evolved. It just seems many of us have forgotten it.

Featured image credit: Fruit, by Alex M. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post We should all eat more DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

January 6, 2016

If “ifs” and “ands” were pots and pans….

If things happened as they are suggested in the title above, I would not have been able to write this post, and, considering that 2016 has just begun, it would have been a minor catastrophe. People of all ages and, as they used to say, from all walks of life want to know something about word origins, but they prefer to ask questions about “colorful” words (slang). By contrast, our indispensable conjunctions don’t seem to attract anyone’s attention, though and, but, if, whether, and so forth have a long and intriguing history. (Let me mention in parentheses that of all the words I have investigated, yet was the hardest.)

You may remember that “The old Grey Donkey, Eeyore, stood by himself in a thistly corner of the forest… and thought about things. Sometimes he thought sadly to himself, ‘Why’ and sometimes he thought ‘Wherefore’ and sometimes he thought ‘Inasmuch which’—and sometimes he didn’t quite know what he was thinking about.” Smart creatures ruminate on such questions only when they lose their tails (and this is of course what happened to Eeyore in Chapter 4). Unlike them, etymologists ponder similar problems every day, for thereby hangs their tale.

Inasmuch as…. What an unwieldy, ugly creation, even worse than whereas! Another equally graceless monster is notwithstanding. The Grey Donkey might have asked: “Not with whom standing near what?” The briefest look at inasmuch and notwithstanding will suggest that they cannot be old. As a matter of fact, they don’t even have to be fully native. Thus, notwithstanding owes its existence to a French model, and so does because (from by cause). Nonetheless and its inordinately long German analog nicthsdestoweniger are even more frightful. However, we need not tarry in the freak museum of conjunctions and misshapen adverbs. Of greater importance is the fact that subordinating conjunctions are in general late additions to the Germanic languages. One can say: “She came too late, and, unfortunately, I could not ask her anything” or “She came too late, so that, unfortunately, I could not ask her anything.” In the first sentence, the two parts are connected by means of a coordinating conjunction (and). This type of syntax is called parataxis, and children, in describing events, prefer it: “John saw me, and he said he will beat me up, and I said ‘no way’, and we fought, etc.” “When John saw me, he said, etc.” sounds more literary and “sophisticated”; the use of subordinating conjunctions (and, as a result, of subordinate clauses) is called hypotaxis.

A classic type of parataxis

A classic type of parataxisIn the Germanic languages, ramified subordination developed late. A classic example of nascent hypotaxis has been retained by Old Icelandic. That language had two conjunctions for all types of subordination: er and the less frequent sem. Er functioned as a jack of all trades. Therefore, in translating a saga into Modern English, one has to guess whether, from our point of view, it meant which, when, how, because, though, if, or whatever. Although his indeterminacy did not bother the speakers, characteristically and perhaps deservedly, er did not continue into Modern Icelandic.

We can wonder how those people managed to understand one another, but we don’t notice similar cases in our own language. Take Modern Engl. as: “She smiled at me as [when] she passed,” “As [because] this task is too hard for you, we have to think of something else,” “The examples are as follows,” “You know it as well as I do,” “As often happens in early childhood…” Since is only slightly better: “Many years have passed since we met,” “Since you cannot do it, I’ll have to hire someone else.” In German, wenn means ‘when’ and ‘if’. A fragment like wenn sie kommt can mean “when she comes” or “if she comes.” No one complains. On the other hand, we sometimes have subtle distinctions that hardly anybody needs. What is the difference between for and because? Old grammars taught that for is a coordinating conjunction and needs a colon before it (“I cannot answer your question: for I never studied French”), while because denotes subordination and, if it requires a punctuation mark, it should be a comma—a classic example of an artificial rule. Anyway, for is a preposition (compare forever)!

Jack of all trades: the beginning of hypotaxis

Jack of all trades: the beginning of hypotaxisToday I’ll touch on the history of the conjunction if, a short word, and shortness never augurs well in etymological research (one has too little space for guesswork and maneuvering). Old English had gif (pronounced as yif); it lost its first sound only in the Middle period. Gothic used two similar conjunctions: one began with j- (jabai “if, although”), the other did not (ibai ~ iba “lest, that…not,” a word that implied a negative answer). It is hard to imagine that jabai and ibai were not congeners or that they did not occasionally get into each other’s way. Nibai, the negative counterpart of ibai, meant “if not, unless, except.” The Old High German forms were iba, oba, and ube; finally, Old Icelandic had ef. From our perspective, all of them meant “if.” As a rule, when monosyllabic and dissyllabic forms of the same word coexist and there is good reason to believe that they are allied, the shorter forms are the result of abridgment. Consequently, the earliest conjunction probably contained two syllables and was closer to the Gothic form. Its meaning seems to have fluctuated between “if” and “whether.” Ob, the Modern German continuation of oba, means “whether,” not “if”; as we have seen, the German word for if is wenn, the same as for “when.” The vowels in it perhaps alternated depending on stress conditions.

But why should a word like ibai have meant “if”? Old Icelandic had the noun if ~ ef and ifi ~ efi “doubt,” and it corresponds perfectly to the meaning of if. However, there is a strong suspicion that it was derived from that conjunction, rather than the other way around. Or perhaps it has an etymology of its own. As I never tire of repeating, one obscure word cannot shed light on another word of undiscovered origin. It can come as a surprise that such short words as yet and if at one time consisted of two parts. As regards yet, we can be almost sure that –t was at one time added to ye-. In all likelihood, a similar development underlies the history of if. Its i- can be a pronominal root (that is, a root occurring in pronouns), as in it (also a two-morpheme form!), whereas ba-, as in Gothic and Old High German, is, according to the great German philologist Karl Brugmann, akin to both (from Old Engl. ba-th; its root was ba-, with long a, pronounced as in the modern noun spa). If so, ibai meant something like “these both”; hence the possibility of choice and the emerging sense “if.” But less convoluted approaches to ibai also exist. One of them calls our attention to Slavic and Baltic ba ~ bo, a particle with a broad range of meanings, from “yes” to an exclamation of surprise. Kindred forms have been attested in several languages, and its Germanic cognate looks like a possible candidate for the second element of ibai. In any case, the English conjunction is the result of the curtailment of a longer, dissyllabic word.

If not you, who will? Do you read and comment on the blog ‘The Oxford Etymologist?’

If not you, who will? Do you read and comment on the blog ‘The Oxford Etymologist?’Does any of the iffy solutions offered above look probable? Yes, at least partly. “If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you….” What else is left for a historical linguist who dissects the shortest words in order to reassemble them and emerges with a meaning like “if”?

Image credits: (1) Château d’If in Marseille (1890-1905). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Two yoked oxen (1860-1900). Public domain via Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. (3) Very busy businesswoman. (c) jesadaphorn via iStock. (4) I want you for U.S. Army : nearest recruiting station. James Montgomery Flagg, c. 1917. Public domain via Library of Congress.

The post If “ifs” and “ands” were pots and pans…. appeared first on OUPblog.

Gender politics of the generic “he”

There’s been a lot of talk lately about what pronouns to use for persons whose gender is unknown, complicated, or irrelevant. Options include singular they and invented, common-gender pronouns. Each has its defenders and its critics. Then there’s the universally indefensible option of generic he. We avoid it today because generic he is sexist, but although that was the form approved by many eighteenth-century grammarians, some of them objected to it. Both the grammar politics and the gender politics of he have always been complicated, and he probably shouldn’t have become generic in the first place. But the politics of he turned literal too in the United States when women sought, and won, the vote.

Generic he first derived its authority from a rule about Latin gender that was applied to English even though gender in Latin, which has to do with word classes and suffixes, has nothing in common with gender in modern English, which is based entirely on chromosomes and social construction. Here’s how William Lily states the rule, called “the worthiness of the genders,” in the grammar he wrote for English students of Latin in 1567:

The Masculine Gender is more worthy than the Feminine, and the Feminine more worthy than the Neuter.

William Lily, A Short introduction of grammar, 1567, rpt 1765, p. 41; Lily actually lists seven Latin genders, including two types of common gender, along with the doubtful and the epicene. Later readers—men—explained it by saying “The masculine embraces the feminine.” It was like they were still in junior high school.

When grammarians applied this Latin rule to English in the eighteenth century, it fit all too neatly with a society that found males more worthy than females and had no problem with he meaning ‘everyone’ except when it came to voting, or having any rights, or being, like, a person.

Eighteenth-century grammarians also specified a pronoun concord rule which requires pronouns to agree with their antecedents—the words they refer to—in gender and number. That means singular they, in a sentence like “Everyone loves their mother,” violates the number agreement part of the agreement rule, since everyone is singular and their is plural. But in the 1790s, some commentators began to notice that generic he was also ungrammatical: in “Everyone loves his mother,” his agrees with everyone in number, but not in gender, since everyone is a common-gender noun, but his is masculine. A couple of writers thought that one way to solve the problem of generic he would be to invent a new pronoun, but that just hasn’t worked out very well.

In the nineteenth century, the politics of feminism is finally brought to bear on generic he, in politics. In 1875, one anonymous writer, who can’t avoid sounding paternalistic, manages to realize that generic he may be good grammar, but it’s also sexist. In contrast, singular they may be ungrammatical, but at least it’s not unfair to women:

The instincts of justice are stronger than those of grammar, and hence the average man would rather commit a solecism than ungallantly squelch the woman in his jaunty fashion. [Findlay [OH] Jeffersonian, 14 May, 1875, p.1]

Later that same year, another writer, also perhaps snarkily, connects generic he with the growing feminist movement:

We think the next Woman’s Rights convention would and should object to [it]. [Somerset [PA] Herald, 29 Dec., 1875, p. 1]

The politics of he began to move from grammatical to literal as the issue of women’s suffrage gained more attention, and both supporters and opponents of women’s rights focused on the scope of the pronoun he. At least one suffragist sought to make traditional grammar work for women. Equal Rights Party member Anna Johnson argued that, if he was generic, if he could refer as well to she, then statutes describing voters as he could not be used to bar women from voting. Here is what Johnson told John J. O’Brien, Chief of New York City’s Election Bureau:

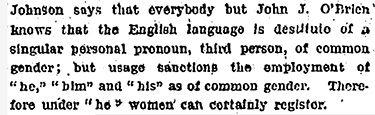

[T]he English language is destitute of a singular personal pronoun, third person, of common gender; but usage sanctions the employment of “he,” “him” and “his” as of common gender. Therefore under “he” women can certainly register. [“The last days of registry.” New-York Tribune, 26 Oct., 1888, 4]

Although Johnson said she managed to register, her argument didn’t make it easier for other women to get on the rolls, because the registrars thought it was fine for he to be generic in grammar but not in politics. Women didn’t get the vote in New York State until 1917, three years before the Nineteenth Amendment.

If he really did mean ‘men only’ when it came to voting, then any laws with masculine pronouns could mean ‘no women.’ With no common-gender pronoun available to clarify a law’s intent, courts and public opinion were divided on the inclusiveness of he. In 1902, the Maryland Supreme Court ruled that women couldn’t be lawyers because the law on eligibility refers to lawyers as he. According to the court, “unless this can be interpreted to include the feminine gender, then the court can find no legislation upon which to base a right to admit the present applicant” (from the Biloxi [MS] Daily Herald, 6 Feb., 1902, 2). In response, the Maryland legislature promptly changed the law, and the first woman was admitted to the Maryland bar later that same year. But erasing sexist language won’t erase sexism: women could practice law in Maryland, to be sure, but they weren’t admitted to the Maryland Bar Association until the 1950s.

Generic he came up as well in American politics when women sought elected office. The Nineteenth Amendment wasn’t passed until 1920, but women got the vote in Colorado in 1893. In 1909, prominent Denver resident Sarah Platt Decker considered a run for Congress, prompting a pundit to ask whether, if she won, the use of he in the United States Constitution would prevent her from serving in the House.

The Constitution provides that “no person shall be a representative . . . who shall not, when elected, be an inhabitant of that state in which he shall be chosen” (Art. I, sec. 2, emphasis added). According to the writer, originalists would say this means Congress is a boys club, no girls allowed:

Strict adherents to the letter of the Constitution maintain that the presence of the masculine pronoun, and the absence of any other, obviously renders ineligible any person of the feminine persuasion.

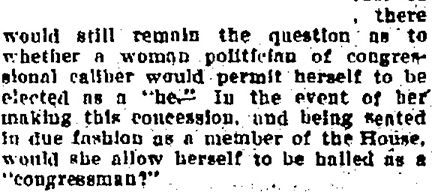

Even if he is found to be generic, the writer goes on to wonder,

whether a woman politician of congressional caliber would permit herself to be elected as a “he.” In the event of her making this concession . . . would she allow herself to be hailed as a “congressman?” [“Gender in politics,” Manchester Union, rpt., Baltimore American, 7 Aug., 1909, p. 8]

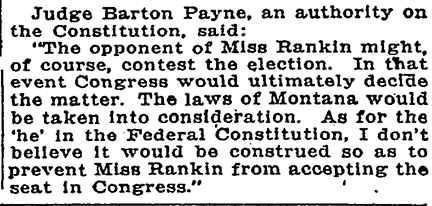

Platt Decker didn’t run after all, but in 1916, Jeanette Rankin, from Montana, became the first woman elected to Congress, prompting another look at Article I, sec. 2. The Washington Post cites “students of the Federal Constitution” who warn that the masculine pronoun might prevent Rankin from being seated by the House of Representatives. But the Post quotes Barton Payne, a prominent Chicago jurist, who dismisses this objection:

As for the “he” in the Federal Constitution, I don’t believe it would be construed so as to prevent Miss Rankin from accepting the seat in Congress. [“Argue That ‘He’ in Constitution Might Bar Miss Rankin From House,” Washington Post, 12 Nov., 1916, p. 6]

Another writer clearly uncomfortable with a woman in the House comments on the “dilemma” of what to call Rankin when she is seated: the “lady from Montana,” the “person from Montana,” or “the member from Montana”? (Morning Oregonian [Portland], 26 Nov., 1916, p. 12). As it turned out, Rankin was seated, and neither the world, nor the English language, exploded.

Today, the literal politics of generic he is settled. As the second-wave feminist slogan puts it, “A woman’s place is in the House, and in the Senate.” And in the White House, as well. And the gender politics of the form is settled as well: all the major grammars, dictionaries, and style guides warn against generic he not because it’s bad grammar (which it is), but because it’s sexist (which it also is). The authorities don’t like the coordinate his or her, either: it’s wordy and awkward. The only options left are singular they or an invented pronoun. None of the 120 pronouns coined so far over the past couple of centuries has managed to catch on. And despite the fact that there are a few purists left who still object to it, it looks like singular they will win by default: it’s a centuries-old option for English speakers and writers, and it shows no sign of going away. Many of the style guides accept singular they; the others will just have to get over it if they want to maintain their credibility.

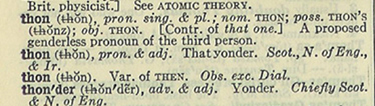

Thon, a common gender pronoun coined in 1884, made it to Webster’s Second (1934), but never succeeded. So much for “it’s in the dictionary.”

A version of this blog post first appeared on The Web of Language.

Featured image credit: “Writing” by tookapic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Gender politics of the generic “he” appeared first on OUPblog.

How do people read mathematics?

At first glance this might seem like a non-question. How do people read anything? All suitably educated people read at least somewhat fluently in their first language – why would reading mathematics be different? Indeed, why would mathematics involve reading at all? For many people, mathematics is something you do, not something you read.

But it turns out that there are interesting questions here. There are, for instance, thousands of mathematics textbooks–many students own one and use it regularly. They might not use it in the way intended by the author: research indicates that some students–perhaps most–typically use their textbooks only as a source of problems, and essentially ignore the expository sections. That is a shame for textbook authors, whose months spent crafting those sections do not influence learning in the ways they intend. It is also a shame for students, especially for those who go on to more advanced, demanding study of upper-level university mathematics. In proof-based courses it is difficult to avoid learning by reading. Even successful students are unlikely to understand everything in lectures – the material is too challenging and the pace is too fast – and reading to learn is expected.

Because students are not typically experienced or trained in mathematical reading, this returns us to the opening questions. Does this lack of training matter? Undergraduate students can read, so can they not simply apply this skill to mathematical material? But it turns out that this is not as simple as it sounds, because mathematical reading is not like ordinary reading. Mathematicians have long known this (“you should read with a pencil in hand”), but the skills needed have recently been empirically documented in research studies conducted in the Mathematics Education Centre at Loughborough University. Matthew Inglis and I began with an expert/novice study contrasting the reading behaviours of professional mathematicians with those of undergraduate students. By using eye-movement analyses we found that, when reading purported mathematical proofs, undergraduates’ attention is drawn to the mathematical symbols. To the uninitiated that might sound fine, but it is not consistent with expert behaviour: the professional mathematicians attended proportionately more to the words, reflecting their knowledge that these capture much of the logical reasoning in any written mathematical argument.

Another difference appeared in patterns of behaviour, which can best be seen by watching the behaviour of one mathematician when reading a purported proof to decide upon its validity (see below). Ordinary reading, as you might expect, is fairly linear. But mathematical reading is not. When studying the purported proof, the mathematician makes a great many back-and-forth eye movements, and this is characteristic of professional reading: the mathematicians in our study did this significantly more than the undergraduate students, particularly when justifications for deductions were left implicit.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Mathematician2.mp4

This work is captured in detail in our article Expert and Novice Approaches to Reading Mathematical Proofs. Since completing it, Matthew and I have worked with PhD and project students Mark Hodds, Somali Roy and Tom Kilbey to further investigate undergraduate mathematical reading. We have discovered that research-based Self-Explanation Training can render students’ reading more like that of mathematicians and can consequently improve their proof comprehension (see our paper Self-Explanation Training Improves Proof Comprehension); that multimedia resources designed to support effective reading can help too much, leading to poorer retention of the resulting knowledge; and that there is minimal link between reading time and consequent learning. Readers interested in this work might like to begin by reading our AMS Notices article, which summarises much of this work.

In the meantime, my own teaching has changed – I am now much more aware of the need to help students learn to read mathematics and to provide them with time to practice. And this research has influenced my own writing for students: there is no option to skip the expository text, because expository text is all there is. But this text is as much about the thinking as it is about the mathematics. It is necessary for mathematics textbooks to contain accessible text, explicit guidance on engaging with abstract mathematical information, and encouragement to recognise that mathematical reading is challenging but eminently possible for those who are willing to learn.

Feature Image: Open book by Image Catalog. CC0 1.0 via Flickr.

The post How do people read mathematics? appeared first on OUPblog.

Economic trends of 2015

Economists are better at history than forecasting. This explains why financial journalists sound remarkably intelligent explaining yesterday’s stock market activity and, well, less so when predicting tomorrow’s market movements. And why I concentrate on economic and financial history.

Since 2015 is now in the history books, this is a good time to summarize a few main economic trends of the preceding year. And, bearing in mind the caution offered above, to speculate a bit about what may be coming down the road in 2016.

Inflation, unemployment, and oil prices

Historically, inflation and unemployment move in opposite directions, because a growing economy typically puts upward pressure on prices and employs more people.This pattern can be seen in the graph below of US inflation (red line) and unemployment (blue line) during 1948-2005.

![US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items [CPIAUCSL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/CPIAUCSL/, December 23, 2015.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452216151i/17662525._SX540_.png) US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items [CPIAUCSL]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 23, 2015.

US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items [CPIAUCSL]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 23, 2015.Compare this historical pattern with the experience of the past decade, presented below. Since the end of the recession (shaded gray), and particularly since 2011, both inflation and unemployment have declined.

![US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Civilian Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/UNRATE/, December 23, 2015.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452216151i/17662526._SX540_.png) US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Civilian Unemployment Rate [UNRATE]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis December 23, 2015.

US. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Civilian Unemployment Rate [UNRATE]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis December 23, 2015.The conflicting signals given by inflation and unemployment since 2011 put the Federal Reserve (Fed) in a bit of a bind. Should short-term interest rates be kept near zero, as they had been for almost a decade, until inflation picks up, or increased slightly in response to the strengthening job market? In mid-December, the Fed raised the target for the federal funds rate from 0-0.25% to 0.25-0.5%. This is seen as the beginning of a gradual return of interest rates to pre-crisis levels, however, the pace at which the Fed raises rates will depend crucially on the path of inflation and unemployment throughout 2016. If the economy falters, don’t expect a second rate increase too soon.

Some of the decline in inflation has been due to the fall in energy prices (see the graph below). Oil prices, which were over $100 per barrel in mid-2014, fell to $35 per barrel in mid-December 2015. Low oil prices have resulted from reduced global demand, due to the ongoing worldwide economic slowdown, and increased US production as a result of the shale/fracking revolution.

Declining energy prices have provided a boon for consumers and non-energy industries in the US and have been particularly costly for the energy producing countries of the Persian Gulf, Russia, and Venezuela. They have also reduced incentives to conserve energy and investments in alternative energy technologies, and probably led to more pollution. It is hard to imagine oil prices falling much further; in the absence of robust world-wide economic growth, which is probably not imminent, or a major war in the Middle East, there is no obvious reason why they would return to the $100-level in 2016. Energy prices, then, are unlikely to boost inflation or become a drag on economic growth.

![US. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) - Cushing, Oklahoma [DCOILWTICO], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/DCOILWTICO/, December 23, 2015.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452216151i/17662527._SX540_.png) US. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) – Cushing, Oklahoma [DCOILWTICO]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 23, 2015.

US. Energy Information Administration, Crude Oil Prices: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) – Cushing, Oklahoma [DCOILWTICO]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, December 23, 2015.The dollar and the euro

By initiating an increase in interest rates, the Federal Reserve stands in stark contrast to the European Central Bank (ECB). The Fed ended its quantitative easing (QE) bond-buying program in October 2014 and, as noted above, began to raise short-term interest rates in December 2015. The ECB has done the exact opposite by lowering interest rates into negative territory and beginning its own QE program in January 2015.

The consequences of these Fed and ECB policies, which appear likely to persist, are easy to forecast. The US-European interest rate spread will encourage money to flow from Europe to the US, thereby increasing the value of the dollar relative to the euro–an appreciation of the dollar and depreciation of the euro. The graph below, which shows the price of the euro vis-à-vis the dollar, demonstrates that the dollar has been appreciating since 2014, largely because economic growth has been more robust in the US than Europe. The contrasting monetary policies should accelerate that trend moving into 2016. This will likely hurt US exporters, since their products will become more expensive for Europeans, and will be a drag on US economic growth. It will, at the same time, provide some support for European economic growth.

![Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), U.S. / Euro Foreign Exchange Rate [DEXUSEU], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/DEXUSEU/, December 23, 2015.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1452216151i/17662528._SX540_.png) Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), U.S. / Euro Foreign Exchange Rate [DEXUSEU]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis December 23, 2015.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), U.S. / Euro Foreign Exchange Rate [DEXUSEU]. Public domain via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis December 23, 2015.Count the votes

There are, of course, many other factors that will affect the world economy in 2016, particularly elections.

We have not yet seen the full effects of watershed legislative elections in Venezuela and an important presidential election in Argentina. These were decisive and potentially game-changing elections, which have the potential to bring sound economic policy to two important Latin American economies, where sound economic policy has been sadly absent for many years. Two 2016 elections will be crucial. The 8 November presidential election in the US will offer a choice between Hillary Clinton, representing continuity with current economic policy of the Obama Administration, and…a Republican candidate. That Republican could be a serious and thoughtful politician, who could provide a competing vision for the US. Or it could be Donald Trump.

Another important election that is on the agenda, but has not yet been scheduled, is the British referendum on exit from the European Union, also known as ‘Brexit.’ Prime Minister David Cameron has recently indicated that the referendum, which he had promised to hold by 2017, will now probably take place in mid-2016. With the PM’s Conservative Party—and even his own cabinet—divided on the issue, and the opposition in disarray, this is shaping up to be one of the more important events of 2016.

There is a Chinese curse, probably apocryphal, that you should live in interesting times. With sharply contrasting monetary policies on both sides of the Atlantic, declining unemployment and low inflation in the US, an appreciating dollar, and low energy prices which seem unlikely to rise anytime soon, 2016 is shaping up to be an interesting, and not a especially predictable, year.

Featured image credit: computer summary chart by Negativespace. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Economic trends of 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

January 5, 2016

In memoriam: Sidney Mintz

Professor Sidney Mintz passed away on 26 December 2015, at the age of 93. “Sid,” as he was affectionately called by his acquaintances, taught for two decades at Yale University and went on to found the Anthropology Department at Johns Hopkins. His best-known work, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, was published in 1985; other major publications include Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History (1974), Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Power, and the Past (1997), and Three Ancient Colonies: Caribbean Themes and Variations (2010).

Sweetness and Power established Mintz as a leading cultural anthropologist. At a time when food was academic anathema and generations of anthropologists ignored food in their field surveys, Professor Mintz took the opposite tack. His fascination with sugar grew out of his fieldwork in Puerto Rico, where he studied the lives of sugarcane cutters. As Professor Mintz explained, he was “awed by the power of a single taste, and the concentration of brains, energy, wealth, and — most of all, power — that had led to its being supplied by so many, in such stunningly large quantities, and at so terrible a cost in life and suffering.” Sweetness and Power had an immediate impact not only on anthropology, by expanding the boundaries of acceptable study in that discipline (“food anthropology” became a common descriptor), but also on the emerging field of food studies. Dr. Marion Nestle, who co-founded the NYU food studies department, notes in her personal remembrances of Sid that the department “polled academics working on food issues about what should be included in a Food Studies ‘canon’—a list of books that every student ought to master. Only one book appeared on everyone’s list: Sweetness and Power.”

I never met Sid, and I wish I had. By all accounts he was warm, generous, and witty. But I did get a glimpse of what he was like over the past year and a half when I served as the managing editor for The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. This A-Z reference book covers not only pastries, candies, ices, preserves, confections, and so forth, but also describes how the human proclivity for sweet has brought richness to our language, our art, and, of course, our gastronomy. And, on the flip side, how demand for this commodity has spurred some of the darkest impulses in human history. Darra Goldstein, the Editor in Chief, and I knew immediately that Sid, who had spent his life studying our desire for sweetness, needed to write the Foreword. He was already in his 90s when we first asked him, long since retired and saying no to every new writing request. He said no to us, too. But he was intrigued by the project, and that emboldened us to ask a second time. This time I stretched the deadline as far back as our production schedule allowed, and he agreed.

What he wrote needed no editing; it was a masterful synthesis of all of the themes of the book, woven together with personal anecdotes and reflections. It begins with his fieldwork in Puerto Rico: “I can remember easily the first time I stood deep in a field of sugarcane in full bloom, a field already marked for harvesting.” It ends with a scholarly flight: “[Sugar] is a food that has meant much to humans, one that supplanted its predecessor worldwide, and that is a metaphor for so much, its history brimming over with the cruelty of man to man, but also with thoughts of sweetness and all of the pleasures that taste connotes.”

I find it extremely humbling to think of Sid, in his nineties, putting pen to paper and teasing out all of the contradictory threads collected over a lifetime of studying this deceptively simple foodstuff. Sid once wrote, “Had it not been for the immense importance of sugar in the world history of food, and in the daily lives of so many, I would have left it alone.” Good thing for us he did not.

Featured image: Sugarcane fields. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post In memoriam: Sidney Mintz appeared first on OUPblog.

National Cancer Institute’s new tool puts cancer risk in context

Type “cancer risk assessment” into Google, and you’ll come up with a list of assessment tools for particular cancers, most with a strong focus on personal risk factors related to lifestyle, exposures, and medical and family history. Would it help also to get a broader view of cancer risk? The National Cancer Institute thinks so. NCI has teamed with Dartmouth researchers Steven Woloshin, MD, and Lisa Schwartz, MD, to create “Know Your Chances,” a website that aims to put cancer risk in perspective.

“We want to get people to understand the risks of dying from specific cancers in comparison to each other and to noncancer causes of death, and at different times in their lives,” said Eric J. (Rocky) Feuer, PhD, chief of the Statistical Research and Applications Branch in NCI’s Surveillance Research Program and the senior investigator in this project. Without this larger picture, it’s hard to make sense of cancer statistics, according to Woloshin and Schwartz, both professors at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice and codirectors of its Medicine in the Media Program.

“It’s difficult to read a newspaper or magazine, watch television, or surf the Internet without hearing about cancer,” they say in the introduction to the website. “Unfortunately, these messages are often missing basic facts needed for people to understand their chance of cancer: the magnitude of the chance and how it compares with the chance of other diseases.”

The Charts

“Know Your Chances” has four sections:

Big-picture charts give the chance of dying over ten-year periods, by age, sex, and race for different cancers; other major causes of death; and all causes combined.

Custom charts allow users to generate charts by age, sex, and race for different causes of death and over different time frames.

Your chances let users see leading causes of death by sex, race, and exact age.

Special cancer tables show the risk of diagnosis, as well as death, for particular cancers and across cancer sites.

The data and estimates for the new charts come from NCI’s DevCan statistical algorithms and database. DevCan calculates probabilities of developing and dying from specific cancers by using incidence data from the agency’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program; mortality counts from the National Center for Health Statistics; and US census data.

The idea of comparing probabilities and using other ways to provide a broader context builds on earlier work by the Dartmouth researchers, who have published widely on the communication of medical and statistical information, especially in relation to risk.

“We saw an opportunity to marry the kind of calculation we do to the kind of risk communication messages they do,” said NCI’s Feuer.

Accurate risk communication messages are based on several principles, Schwartz and Woloshin said. One is to put the number of deaths in numerical context—e.g., three of 100 people, or 3%—rather than the absolute number of people expected to die of a disease. Give the denominator, in other words, as well as the numerator. Another is to avoid making statements of relative risk without giving actual figures. A 50% risk reduction sounds large but may not mean much if risk is reduced from 4% to 2%. But if risk is reduced from 60% to 30%, a 50% reduction can mean a lot.

A guiding principle is to put risks in accurate perspective. “We wanted to put risk in context,” Schwartz said, “by using denominators, by comparing each specific cancer to other cancers and other major causes of death, and by using standardized time frames and formats.”

The ten-year time frame is arbitrary but makes sense, they said, because it avoids the exaggerated risk that comes with time frames that are too long as well as those that are too short. “Over-a-lifetime risk distorts the picture, but so can too short a time frame,” Woloshin said. That can cause you to underestimate your risk.”

The ten-year time frame also allows people time to do things such as make lifestyle changes or consider proven screening tests, they note on the website.

Setting Priorities

The charts present risk by age, sex, and race, but so far not by factors related to lifestyle or heredity. However, NCI plans to add smoking, the single most important risk factor for a variety of cancers and other causes of death.

In an earlier version of the charts, the Dartmouth authors included how smoking affects risk. Data and methods are now being updated using National Health Interview Surveys that include smoking status and follow-up data on mortality and cause of death. As for family history, lifestyle, and other risk factors, finding comparable data sources may be more problematic.

“We have to consider feasibility,” Schwartz said. “Right now we don’t have good data for all of them. But even with extra risk factors we might not know that much more.”

In any case, “Know Your Chances” is not designed to do exactly the same thing as other risk assessment tools, which may provide estimates for a single disease as a function of several risk factors. Instead, it could complement them, Feuer said. “We see it as providing breadth, giving the broad landscape. It could help a person make decisions about priorities—diabetes, lung cancer, heart attack, for instance—before making decisions about lifestyle changes or screening.

“Both facts and values go into decision making,” Woloshin noted. “These charts give facts. The values are individual, how you process the facts. Research has shown people process the same facts differently.”

That finding suggests that the charts’ facts could be the basis for doctor–patient discussions of risks and what to do about them.

In fact, “the charts could be the first step in a huge educational process,” said Otis Brawley, MD, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society. He said physicians could use the charts to help patients avoid the common pitfall of exaggerating the chance of dying from one disease, such as prostate cancer, while minimizing the greater chance of dying from others. For instance, a 55-year-old white man has a one in 1,000 chance of dying from prostate cancer within ten years, compared with two in 1,000 for high blood pressure, three in 1,000 for stroke, and ten in 1,000 for lung cancer, according to the charts.

“One of the great problems we deal with in our society is that people don’t understand or they misperceive risk,” Brawley said. “These charts could reduce a lot of mental anguish and a lot of concern.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured Image credit: Cancer by PDPics. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post National Cancer Institute’s new tool puts cancer risk in context appeared first on OUPblog.

The Irish Trollope

There are times when it feels like Anthony Trollope’s Irish novels might just as well have fallen overboard on the journey across the Irish Sea. Their disappearance would, for the better part of a century, have largely gone unnoticed and unlamented by readers and critics alike. Although interest has grown in recent times, the reality is that his Irish novels have never achieved more than qualified success, and occupy only a marginal place in his overall oeuvre. Yet Ireland was central to Trollope, both as a writer and a civil servant, and he had no hesitation in acknowledging his genuine affection for the country and its people. As he wrote in North America:

It has been my fate to have so close an intimacy with Ireland, that when I meet an Irishman abroad I always recognize in him more of a kinsman than I do in your Englishman. I never ask an Englishman from what county he comes, or what was his town. To Irishmen I usually put such a question, and I am generally familiar with the old haunts which they name.

While nobody disputes the importance of Ireland for Trollope, the man, many still do not see its importance for Trollope, the writer. He lived for almost twenty years in Ireland, having gone there to take up a position in the Irish Post Office in the remote rural town of Banagher, County Offaly in the early eighteen-forties. He travelled the length and breadth of the famine-stricken island, mostly on the back of a horse, mapping out postal routes and probably knew its physical layout – its villages and towns, its houses, great and small, its roads and lanes, Churches, inns and hostelries – better than the vast majority of the Irish themselves. His move to Ireland belatedly kick started what had been, until then, an unpromising Post Office employment and a non-existent literary career. His first two novels (the tragic MacDermots of Ballycloran and the comic The Kellys and the O’Kellys) were written and set in Ireland. Despite his publishers’ opposition, Trollope would persist with Irish themes, settings, and characters throughout his career and there is a considerable Irish strain even in his evidently English novels.

Image credit: Portrait of Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) by Napoleon Sarony. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Portrait of Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) by Napoleon Sarony. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1859 he published a deeply problematic but revealing Famine novel, Castle Richmond, which combines deeply empathetic description of hunger and death with a jarring Providentialist political interpretation of the tragic events. His final novel was the unfinished The Landleaguers which he wrote as an ailing elderly man, and which gives voice to his alarm for an Ireland in the grip of the Land War. Whereas his early Irish works depict various social strata of society from peasants to landlords, both Catholic and Protestant, Unionist and Nationalist, his final, far more conservative work is firmly on the side of the entrenched Ascendancy class.

The ‘Irish’ works that get the most persistent attention are Phineas Finn and Phineas Redux, two of the great central novels of the ‘Palliser’ series. But in the Pallisers, Finn’s Irishness, although initially important, is increasingly diluted, partly because Trollope himself wrote that it had been a “blunder” to make Phineas Irish. If Trollope later saw it as a blunder, at the time it was wholly intentional and signalled the central importance of Ireland to Trollope as a young man emerging from John Bull’s other island, into a central position within the Post Office, and onto the English literary scene.

Phineas Finn, an opportunistic young Irishman who manages to insert himself into the English political system, stands as a symbol for his creator of how the Union between the two countries can work to the benefit of the Irish. In a sense, Phineas is a version of Trollope himself who used his writings to act as a cultural go-between between the two countries in a period distinguished by prolonged mutual misunderstanding. Among his writer peers, he was uniquely equipped to carry out this role, coming to know Ireland almost as an insider, albeit one with strong personal and political opinions, many of which were often paternalistic. His Irish novels never fail to be critical of the absentee English landlords who bore so much of the responsibility for Ireland’s impoverished condition. Later Trollope would react with mounting despair to Ireland’s exorable slow march towards Home Rule.

Trollope engages in far less anti-Irish prejudice than his peers, although he regularly apologises to his readers for inflicting Irish subjects upon them. He was unusually supportive of the Irish Catholic Church, and saw Irish priests as having a crucial role to play in containing the political aspirations of an increasingly nationalist population. Much like Aubrey de Vere, he felt they were “the chief barrier . . . between us and anarchy.”

Although the standard view is that Trollope novels are, as Nathaniel Hawthorne put it, “as English as beef-steak”, serious consideration of Trollope’s Irish novels show that he was a genuine border-crosser who sought to understand Irish politics, religion, language, and culture, and to present that to an English audience. In so doing, he made a valuable contribution to the canon of the Irish novel and is deserving of attention as a key figure connecting English and Irish literary traditions in the nineteenth century.

Featured image credit: Glendalough Lower Lake by Shever. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Irish Trollope appeared first on OUPblog.

The music parenting tightrope

Walking the music parenting tightrope isn’t easy for music moms and dads. Figuring out how to be helpful without turning into an overbearing nag can be tricky, especially during a youngster’s early adolescent years. Those often-turbulent years can upend many aspects of a child’s life, including music. Kids who had previously enjoyed making music may find themselves with a bad case of the doldrums, leading to a practice slowdown and threats of quitting.

For parents who sense that their threatening-to-quit youngsters really love music, the challenge becomes how to tactfully help disgruntled kids reconnect with music. A variety of strategies can work. One approach that is particularly effective involves hitting the pause button. Both parents and kids take a step back and ease up on expectations for a while. Then together they and the youngsters’ music teachers can figure out what is really going on and how to plot a new course. Below are four accounts of this strategy in action.

Instrument switch. When her older daughter announced during middle school that she didn’t want to play violin anymore, especially not classical violin pieces, this mother bought sheet music for fiddle tunes that she knew her daughter liked and encouraged her daughter to sight read them whenever she threatened to quit. The girl’s violin teacher was onboard with this repertoire change, too. However, soon mother and teacher recognized the crux of the problem: sibling issues. “It’s not uncommon for an older sibling to be overtaken by a younger one and that’s what happened to my older daughter,” says this mother. The older girl felt “so frustrated” because a younger sister, also a violinist, had “caught up and surpassed” her. The teacher suggested that in order to sidestep the sibling competition, the older girl, who was quite a good musician, could switch to viola. She gave it a try, fell in love with viola, and did so well on it during high school that she won a scholarship at a conservatory, where she is now majoring in viola performance.

Being part of a youth ensemble is a terrific way to help adolescents stay as excited about music as these members of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City. Photo courtesy of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City, Artistic Director/Founder Francisco J. Núñez; photograph by Stephanie Berger.

Being part of a youth ensemble is a terrific way to help adolescents stay as excited about music as these members of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City. Photo courtesy of the Young People’s Chorus of New York City, Artistic Director/Founder Francisco J. Núñez; photograph by Stephanie Berger.Genre switch. The first piano teacher that Betsy McCarthy’s son had during elementary school encouraged him to improvise and write music. “It was very freeing and fit him exactly,” she says. When this teacher quit teaching, her son moved on to classically-oriented piano teachers. They didn’t suit him as well. Although he liked the teacher he had during middle school, his mother notes, “They butted heads a lot because he was born to improvise. We realized jazz fit him better than classical. We asked around and found a jazz teacher who is classically trained.” The result: He became a terrific jazz pianist, excelled in his high school jazz band, and continued classical piano too. For his college years, he has been in a jazz program at a major conservatory, where he studies with a classical piano teacher as well as with top-level jazz mentors.

Practice moratorium. Marion Taylor’s daughter, who played flute and was also into sports, announced during seventh grade that maybe she should quit flute lessons because she wasn’t practicing. Her mom recalls, “I told her, ‘We don’t mind continuing to pay for lessons. Let’s just keep music as part of your life.’ The teacher kept plugging away, and Becky rode past that hump.” She continued to play in her school ensembles, where the social aspect of making music with other kids helped rekindle her interest in flute, especially when she won spots in all-county and all-state honor bands. She did so well in flute during high school that she earned a full music scholarship at a conservatory, followed by admission to a master’s degree program in flute performance.

Lesson on demand. A young cellist with mild learning disabilities had enjoyed playing cello during elementary and middle school. He benefitted from a private cello teacher who adapted her teaching to his needs. His mother found creative ways to help him with focus when he practiced at home. His success in music was a morale booster. His mother notes, “Here’s a kid who’s not supposed to be able to focus, but he gets on stage and plays beautifully a five-minute cello piece he has memorized.” However, adjusting to high school was stressful. “He almost quit cello his freshman year,” she says. “To take the pressure off, his cello teacher had him switch from weekly lessons to ‘lessons on demand.’ My son would contact the teacher whenever he felt he was ready for a lesson.” He kept playing in the orchestra at his music school and after a year and a half, “he returned to weekly lessons with renewed enthusiasm.” He also discovered a new interest—teaching music. He had fun volunteering as a music tutor for younger kids at an after-school music program. “He’s very patient and has always been good with kids,” his mother adds. “He is now applying to college as a music education major.”

Featured Image: Sheet Music, Piano. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The music parenting tightrope appeared first on OUPblog.

January 4, 2016

The Department of Labor awakens

At President Obama’s urging, the US Department of Labor (DOL) has proposed a new regulation condoning state-sponsored private sector retirement programs. The proposed DOL regulation extends to such state-run programs principles already applicable to private employers’ payroll deduction IRA arrangements. If properly structured, payroll deduction IRA arrangements avoid coverage under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) and the employers implementing such arrangements dodge status as ERISA sponsors and fiduciaries. Similarly, a state-sponsored private sector retirement savings program following the DOL’s proposed regulatory guidance will, in the DOL’s judgment, fall outside the coverage of ERISA.

As enacted by California and Illinois, such plans require private sector employers who do not offer their employees 401(k) or other retirement plans to participate in the state savings program. Some hail the DOL’s proposed regulation for state-sponsored private sector retirement plans as facilitating potentially useful arrangements to encourage needed retirement savings. Others denounce the DOL regulation for succoring state-sponsored plans which will unfairly compete against the retirement savings arrangements offered to private employers by private sector pension providers.

I suggest an additional perspective: The proposed DOL regulation, if finalized in its current form, will undermine California’s current statute which uses formula-based, cash balance-style accounts for the Golden State’s private sector retirement savings program. The DOL’s proposed regulation requires that participants in state-sponsored retirement savings programs possess the same unrestricted right to withdraw their retirement savings as IRA participants possess. This unrestricted right of withdrawal will create the possibility of a “run on the bank” if the assets in the proposed California state retirement plan are insufficient to pay larger formula-based claims established by the California statute.

A true IRA continuously adjusts on a dollar-for-dollar basis for investment gains and losses as they occur. In contrast, cash balance accounts do not reflect investment gains and losses as such gains arise and as such losses accrue. Rather, a participant’s formula-style, cash balance account is a theoretical construct which is credited with the participant’s cumulative contributions augmented by an assumed rate of interest regardless of actual investment performance. The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings Trust Act in its current form provides for the California private sector savings retirement plan to use such formula-based cash balance accounts.

As a statutory matter, cash balance accounts (whatever their benefits as a matter of retirement policy) do not qualify as IRAs under the Internal Revenue Code. These theoretical accounts do not receive or reflect actual investment gains and losses but, rather, are governed by formulas based on interest rate assumptions which may or may not prove true in practice.

The California statute uses the cash balance format. Thus, the accounts to be established under the California plan will not qualify under the Internal Revenue Code as true IRAs, which must be adjusted to reflect actual investment gains and losses.

Moreover, the right of withdrawal required by the proposed DOL regulation now undermines California’s cash balance format in practice. The unrestricted right of withdrawal required by that regulation can encourage a “run on the bank” when participants’ entitlements in their formula-based cash balance accounts exceed the resources available to pay the larger promised amounts.

To see this possibility, suppose that the California retirement savings plan is up and running under the current statute and that a particular participant in the plan has an account balance of $10,000. This formula-derived total reflects the participant’s cumulative contributions withheld by her employer plus interest accumulated at the presumed rates assumed by the board administering the California plan.

Let us further suppose a decline in the value of the assets held by the California trust which invests the plan’s resources. Suppose, in particular, that the pro rata trust assets supporting this participant’s account decline to $9,000. Finally, let us further assume that this participant, unsettled by this stock market decline, understands that the State of California by law does not guarantee her formula-based retirement entitlement of $10,000. Consequently, she elects to protect her financial interests by withdrawing the full $10,000 pursuant to her withdrawal right required by the proposed DOL regulation.

If this were a true IRA, the participant would only be able to withdraw $9,000, the current value of the trust assets allocable to her account. However, under the California statute as it now reads, this participant would be entitled to the full $10,000 determined by formula even though the pro rata share of the trust assets allocable to her notional account come to only $9,000.

Suppose now that other participants, seeing the trust’s assets decline and watching this first participant withdraw her formula-based account balance, emulate her and protectively withdraw their respective account balances as well to guard against the California trust’s potential insolvency. In this scenario, a “run on the bank” starts because participants’ claims under their cash balance accounts are determined by formula, not by actual (potentially smaller) asset values.

The drafters of the California statute were evidently aware of this kind of possibility. Hence, under the California statute, the California trust can purchase insurance to guarantee participants’ formula-derived account balances. It is, however, not inevitable that such insurance will be obtained at affordable rates nor is it assured that such insurance will be kept in force. It is, moreover, not foreordained that such insurance, even if purchased, will prevent a “run on the bank” when total formula-based account balances exceed the actual investment values in the California trust funding those theoretical accounts. An insurance company’s guarantee is only as good as the insurer’s solvency or, perhaps more precisely, the perception of that solvency.

Even before the proposed DOL regulation was announced, the California statute required amendment to replace the statute’s formula-based cash balance accounts which do not qualify as true IRAs under the Internal Revenue Code with investment-based accounts which do. By mandating that participants must have unrestricted rights of withdrawal, the proposed regulation now creates the possibility that the California statute’s formula-based accounts will trigger a “run on the bank” when trust assets are less than the total claims represented by those cash balance accounts. If the California legislature undertakes the second vote necessary to effectuate the Golden State’s private sector retirement savings plan, the legislature should emulate the decision of the Illinois general assembly, should jettison the formula-based cash balance accounts now established by the California statute, and should make the retirement savings accounts of the California plan true IRAs which directly receive and reflect investment gains and losses as they occur.

Image Credit: “San Francisco” by Kārlis Dambrāns. CC BY 2.o via Flickr.

The post The Department of Labor awakens appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers