Oxford University Press's Blog, page 561

January 14, 2016

Getting (active) welfare to work in Australia and around the world

In the 1990s Australia began reforming its employment assistance system. Referred to as welfare-to-work, at the close of last century Australia had a publically owned, publically delivered system. By 2003, that system had been fully privatised and all jobseekers received their assistance via a private agency, working under government contract. To this day, Australia is the only country with a fully privatise quasi-market in employment services.

We have previously referred to this field of policy as ‘the reform that never ends’; in Australia, as in other parts of the world, policy makers have enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to design and re-design the way in which jobseekers receive employment assistance. Our research team has been closely following these reforms for more than 15 years. In particular we surveyed frontline employment services staff in Australia, the UK and the Netherlands in 1998, 2008 and 2012. We asked them how they do their job; how they interact with jobseekers; how they link up with other service providers; and how they respond to changes in services delivery policy. What we discovered is a fascinating insight into social policy restructuring and service delivery adaptation.

In the Netherlands the focus has been on devolution. In the UK, the public provider has remained at the centre of the system, although private providers now have increased influence on the system. In Australia, emphasis has been placed on service standardisation and service guarantees. Across all three countries, ‘activation’ has been the catch cry and can be found at the heart of welfare-to-work policy reform in most countries of the OECD.

Activation policy is linked to a ‘work-first’ world-view. Those who subscribe to a work-first philosophy believe that keeping jobseekers busy will generate employment solutions. To be activated is to be engaged – applying for jobs, undertaking training, meeting with employment agency staff – and to be engaged is to be ‘work ready’. To be activated is to be engaged – applying for jobs, undertaking training, meeting with employment agency staff – and to be engaged is to be ‘work ready’. So-called ‘passive’ welfare system have long been criticised as sloppy, inefficient and associated with the old welfare state. In the new era of service privatisation the system is designed to inject energy into the jobseekers’ search for work.

To be activated is to be engaged – applying for jobs, undertaking training, meeting with employment agency staff – and to be engaged is to be ‘work ready.’

Of course, an active system must include penalties. If jobseekers are required to complete certain tasks, then penalties will be linked to non-compliance. This is the ‘stick’ side of the ‘carrot and stick’ paradigm so often associated with social policy. In Australia, we asked employment services staff how often they sanction jobseekers for non-compliance. They told us that in 1998 they sanctioned 2 per fortnight. By 2008 that had increased to 6 jobseekers per fortnight, and it had remained at 6 by 2012.

We also asked Australian frontline staff the extent to which they felt that management in their private agency would encourage jobseeker to take the first job available; i.e. the extent to which their agency is ‘work-first’ in its approach to employment assistance. We found that in 1998, 61% of frontline staff felt that management would strongly encourage jobseekers to get off benefits. By 2012, that had increased to 69%. We also asked frontline staff what their personal advice would be to jobseekers. In 1998, 50% of frontline staff said that they would strongly encourage jobseekers to get off benefits as quickly as possible, even if the job was not ideal. By 2012, that proportion had increased to 64%.

But activation isn’t the only shift we have observed. Over the past 15 years we have witnessed the emergence of what we call ‘double activation’. Double activation refers to a process whereby jobseekers are activated to ensure that they are engaged in the practice of looking for work; while, at the same time, other mechanisms are in place to activate service delivery staff to ensure that they are actively engaged in the practice of encouraging jobseekers to be active. The state, as purchaser, develops policy that activates client-facing staff, and they in turn activate jobseekers.

In Australia, policies designed to activate frontline employment services staff are closely linked to service standardisation and an increased administrative and ‘red tape’ burden. The most common criticism made of Australia’s private employment services system is that it has become a compliance focused, overly prescriptive system. In other words, to ensure that frontline staff are actively doing their job, the Australian government has created a system in which frontline staff must record every and all interactions with jobseekers. This recording requirement has become a large component of the job.

We asked Australian frontline staff the extent to which they felt that they have autonomy in how to work with jobseekers. In 1998, 27% described themselves as ‘free to decide what to do with jobseekers’. By 2012, that proportion had decreased to 11%. As discretion was lost at the frontline agencies became more hierarchical. In 1998, 11% of frontline staff said that if they were unsure they would refer it to their supervisor. By 2012, that proportion had increased to 29%. Our data suggests that as double activation emerged as the overarching principle guiding welfare-to-work, autonomy at the frontline was lost as frontline staff became increasingly focused on doing what they are told; demonstrating that they are active; and ensuring that they are compliant.

Australia now has a newly designed employment assistance system called JobActive. The next task for our research team is to investigate how agencies learn to deliver enhanced services and how they provide assistance to the hardest to help. Australia, like the UK and the Netherlands, struggles to place the long-term unemployed into sustainable jobs. Uncovering how this can be done better is our focus now and we look forward to reporting those new results as soon as possible.

Headline Image: Scrabble – Profession by flazingo_photos. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post Getting (active) welfare to work in Australia and around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Lulu at the Met (November 2015): A good thing becomes too much

Alban Berg’s Lulu is generally acknowledged as one of the master pieces of twentieth century opera. However, because of its many musical and theatrical challenges, it is seldom performed. The last time Lulu was seen at the Metropolitan opera was in 1980. Therefore I looked forward to attending the Met’s 2015-16 production with eager anticipation. The experience was a mixed one, but it was gratifying to hear and see it performed with a sincere commitment and a broad vision.

Artist/director William Kentridge is given star billing for the production. Unfortunately the billing is far too accurate. Although his drawings are gorgeous and often used with wit as they are projected over the entirety of the stage, there are far too many. Constantly changing, they distract from the music, the singing and the story, which should be allowed to be the focus of our attention.

Admittedly there are some wonderful visual effects, among them an amusing moment in the opening scene when a projected door fools us into thinking it’s a real one opening and closing, the magical opening of the second act when the set seems to be peeled back to reveal a steep staircase disappearing up into the unknown, and a moment of perfection after Lulu is stabbed, when the line drawing projected on the panel hiding the deed develops a tiny drip like a black tear.

The final moments were also handled elegantly. The projections stopped. Susan Graham (Countess Geschwitz) sang her last lines with poignant beauty. Suddenly, the touching quiet was shattered by Lulu’s scream, and the projections changed in perfect co-ordination with Berg’s music. Then after the last chord of the piece, Kentridge put up one final projection: “Der Tanz ist aus” (“The dance is over”).The unexpected change kept the audience from beginning to applaud, and so we had the all-too-rare treat of a long moment of silence after the piece was over.

Unfortunately, the orchestra did not maintain an appropriate balance on opening night. All too often the musicians played so loudly that the singers could not be heard. For this I hold conductor, Lothar Koenigs, responsible, although he deserves kudos for his overall phrasing of the piece.

The cast, while solid, was seldom gripping either in their singing or acting. Outside of differentiating the men by different colored costumes, it seemed that Kentridge gave them little support in creating unique characters. We didn’t experience the particular needs or fantasies that make Lulu irresistible to each of them. As a result the pattern of men falling in love with her and then dying, which marks Lulu’s ascent during the first half of the opera, felt slightly repetitious. Of six men who court Lulu, the two vocal standouts were Elizabeth DeShong and Alan, Oke. Ms. DeShong has a clear, brilliant soprano. Unfortunately her characterization of the School Boy consisted of throwing her body about like a strange rag doll. Mr. Oke, on the other hand, not only sang excellently but used his voice and body to delineate the Prince and the Marquis as two unique and memorable characters.

Marlis Peterson as Lulu, although stronger vocally on the top of her register than the bottom, had all the notes, good articulation and sang accurately, but failed to use her voice to create a complex character of variety and mysterious femininity. Indeed, with tedious regularity she behaved as if, by waving her attractive legs, old and young, male and female would be drawn to her. Again I am forced to wonder if Kentridge is not at fault here, since he also added a female character sitting on a grand piano at the side of the stage who also did little more than wave her legs about throughout the show. Perhaps he thought that in building on the Acrobat’s line to Alwa, one of Lulu’s admirers, “You have written a melodrama in which my fiancée’s (Lulu) two legs play principal parts,” he was illuminating the piece. Instead he simply created yet one more distraction.

I am perplexed by Kentridge’s vision of the Countess, who is supposedly enormously wealthy, but whom he clothed as a dowdy Hausfrau. He also consistently staged her so she was hard to find–until the end, when, as I said, Ms. Graham was allowed to create the kind of magic that we have come to expect of her. It is hard to believe that Kentridge is uncomfortable with a lesbian character, but his handling of the Countess deprived us of the chance to experience that Lulu’s seductive attraction is not limited by gender or person. (At one point Lulu sings provocatively. “When I saw myself in the mirror, I wished I was a man–a man married to me.”)

Mounting Lulu is a difficult undertaking. The cast and orchestra are large, its libretto dense, and its extraordinary music challenging. It is most unfortunate, therefore, that the Metropolitan threw away this opportunity to explore this opera’s depths and musical beauty. Rather it continued its descent into “Koncept” productions. It offered us plenty of alluring spectacle, but deprived us of the special aesthetic and emotional satisfactions unique to opera at it best, when it combines great music, evocative singing, engaging story, believable acting, and supporting spectacle to bring human passions to life.

Featured image: Marlis Peterson in Lulu. (c) The Metropolitan Opera via metopera.org.

The post Lulu at the Met (November 2015): A good thing becomes too much appeared first on OUPblog.

January 13, 2016

…whether the wether will weather the weather

It so happens that I have already touched on the first and the last member of the triad whether –wether—weather in the past. By a strange coincidence, the interval between the posts dealing with them was exactly four years: they appeared on 19 April 2006 (weather) and 21 April 2010 (whether) respectively. The essay on weather dealt with the origin of the word, and the one on whether discussed the pronunciation of wh– by English speakers. But the story of the conjunction if, posted last week, gave me a new idea: I decided to say something about the etymology of whether, regardless of its initial group. Also, the eagerly awaited World Spelling Congress is supposed to take place this year, and it has been long since I shed online tears about the horrors of written English, so that here I am back with etymology and orthography, true to the title of my other essay, that is, ready to whet the spelling reformers’ blunted purpose.

To begin with: Why are the words in the title spelled differently but pronounced alike? How did all three of them become homophones in the speech of those who “confuse” which and witch, wen and when, and so forth? The distinction between wh- and w- is preserved by relatively few people, but weather and wether are homophones under all circumstances. Of course, whether once began with hw– rather than wh-, but this is a minor point. More important is the fact that, in Middle English, d between vowels became th (as in Modern Engl. the). This process was part of the wave of consonant weakening that swept over all the Germanic languages, though with different force and with different results. For example, at one time, Engl. is rhymed with hiss and has with lass, but the weakening (or, to use a technical term, lenition) changed them to iz and haz. In Old English, father had d in the middle, and so did weather.

Once again, to use technical terms, in the phonetic classification of sounds d is a voiced stop, while th, as in the, this, thy, is a voiced spirant, or a voiced fricative. It follows that in weather lenition turned a voiced stop (d) into a voiced fricative. By contrast, at a rather remote time, whether and wether had þ (= th in Modern Engl. thick) in the middle, and lenition voiced it (in Old English, the full forms were spelled hweþer ~ hwæþer and weþer). Those who bemoan Spelling Reform because it obscures the past of the English language should insist on returning to weder “weather” and hwather “whether,” though the restitution of æ and þ is also a good idea. A glance at the alphabets of Modern Icelandic, Norwegian, and Danish (especially Icelandic) will show that this idea is fully realistic.

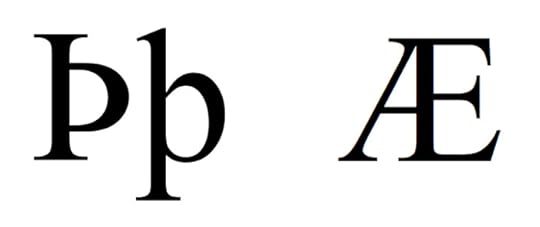

The letters ‘thorn’ and ‘ash’.

The letters ‘thorn’ and ‘ash’.Now, why does weather have ea in the middle? Here we are again in Middle English. (Incidentally, those who intend to study the history of English may consider beginning with the Middle period. The language of Chaucer is incomparably more transparent to modern speakers than the language of Beowulf, and it is not too difficult to move forward and backward from it. Old English often makes little sense without reference to Proto-Germanic and other related languages, whereas Middle English is, to a certain extent, self-sufficient.) In Middle English, vowels followed by a single consonant were usually lengthened, but before –er a great deal of vacillation occurred. In words like feather, heather, leather, weather, the vowel must sometimes have been pronounced short and sometimes long. The spelling with ea reflects length, but, as ill luck would have it, the modern language generalized short e in weather and the rest, so that the traditional spelling gives us wrong ideas.

Some cases are truly outrageous. The worst is of course read, the past tense of read. But everyone who deals with undergraduate papers also knows the horror of lead. For some mysterious reason, the name of the metal seems to baffle no one, but its homophone, the past of the verb lead, invariably appears as lead, perhaps on analogy of read—read. On December 31, 2015, I read (!) a reprint of an article by Angela Fritz from The Washington Post, titled “Storm spikes polar temperatures,” in which the author wrote: “A powerful cyclone—the same storm that lead to two tornado outbreaks in the U.S. and disastrous river flooding, has driven the North Pole to the freezing point this week….” If I were mean enough to make an ad hominem remark, I might say that something is on the fritz in the process of proofreading in the offices of even our best newspapers, but of course I cannot even think of doing such a thing. (How many people know the name of the rhetorical device to which I have resorted, that is, of making a statement while pretending not to do so?)

This wether will certainly weather the weather.

This wether will certainly weather the weather.Something should also be said about the origin of wether and whether. The etymology of the animal name is disputable but not hopelessly obscure. The word may have been coined as the name of a sexually inactive goat or ram (not yet mature or made impotent by castration). But perhaps the Indo-European root of the word meant “year”; the Gothic cognate of wether means “lamb.” If so, wether signified a year-old animal. Such names, designating very young, two-year old domestic animals (for example, twinter—from two and winter— and yearling), a cow that has not yet calved and has to be protected from bulls (such is one of the proposed etymologies of Engl. heifer), and so forth are common.

Whether at its inception meant “one of the two”; hence the conjunction introducing alternatives. Its ancient root was the same as in the pronoun who; –er is the comparative suffix, as in other. Russian kotoryi “which one” (stress on the second syllable), allied to whether, has retained the word’s initial sense. The idea of the alternative also comes to the foreground in German weder, which today occurs only in weder… noch “neither… nor” and entweder… oder “either… or.” Earlier, it could stand at the beginning of a sentence and mean “which one?” like its Slavic congener and analog. The comparative suffix is also present in some words in which we don’t notice it. But when we are told that it occurs in other and either, we realize that the etymology must be correct because each of them suggests choice. The suffix –er formed such a strong association with expressing an alternative that it attached itself to the conjunction or. The Old English for “or” was oþþe. In the Middle English poem Ormulum (see the post on blunt, part 1 on it), three forms occur: oþerr, oþþr, and (before consonants) its shortened variant orr. Our or is its reflex (continuation). German oder “or” went the same way, from eddo. But German also has aber “but,” which reinforced the er-group.

So one wonders whether the wether will weather the weather or whether the weather the wether will kill. I hope the animal will do just fine. We have a harder time weathering the onslaught of Modern English spelling. Shall we overcome?

Featured image: (1) Three Polar bears approach the starboard bow of the Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine USS Honolulu (SSN 718) while surfaced 280 miles from the North Pole. Photo by Chief Yeoman Alphonso Braggs, US Navy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Letters ‘thorn’ and ‘ash’. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Sheep and lamb jumping. (c) MaXPdia via iStock.

The post …whether the wether will weather the weather appeared first on OUPblog.

A memorial for Gallows Hill

We now know the precise location where 19 innocent victims were hanged for witchcraft in Salem in 1692. I am honored to be a member of the Gallows Hill Project team who has worked with the City of Salem to confirm the location on a lower section of Gallows Hill known as Proctor’s Ledge. And I am pleased too that the city has already begun planning to properly memorialize the site.

The executions on Gallows Hill were the climax of one of the most famous events in American history, but the hangings themselves are poorly documented. The precise location and events surrounding the executions have been, until this point, generally lost to history. Tradition has simply placed it broadly on Gallows Hill, which covers many acres of land. In the seventeenth century, Gallows Hill was common land located just outside the boundary of the City of Salem, then defined by a protective palisade (a fortified wall). Most people have traditionally placed the execution site at the top of Gallows Hill.

In the early twentieth century, the eminent Salem historian Sidney Perley studied the issue and settled on the Proctor’s Ledge location, an area bounded today by Proctor and Pope Streets, near the foot of Gallows Hill. The City of Salem even acquired a small parcel there in 1936 “to be held forever as a public park” and called it “Witch Memorial Land.” As it was never marked, most people erroneously assumed the executions took place on the hill’s summit. Over time, the spot became forgotten again.

In 2010, Elizabeth Peterson, Director of Salem’s Corwin House, also known as the Witch House, brought together a team of experts to re-examine Perley’s research. In addition to myself, that team included Benjamin Ray, Professor of Religion, University of Virginia; Marilynne Roach, Salem witch trials historian and author; and Peter Sablock, Emeritus Professor of Geology, Salem State University. The team’s analysis brought together multiple lines of evidence to confirm Proctor’s Ledge as the execution site.

Memorial lookout tower at Little Round Top, Gettysburg, to the soldiers of the 12th and 44th New York Infantry regiments, who helped save the Union’s flank. Image Credit: “Little Round Top 12th New York lookout” by Emerson Baker.

Memorial lookout tower at Little Round Top, Gettysburg, to the soldiers of the 12th and 44th New York Infantry regiments, who helped save the Union’s flank. Image Credit: “Little Round Top 12th New York lookout” by Emerson Baker.Marilynne Roach had years ago called attention to the testimony of accused witch Rebecca Eames. She testified that on her way into Salem for questioning on the morning of 19 August 1692, she and her guards had traveled along the Boston Road which ran just below the execution site. Five people were being executed at the time, and from her location at “the house below the hill” she saw some “folks” at the execution. Roach determined that the “house below the hill” was most likely the McCarter House, or one of its neighbors on Boston Street. The McCarter house was still standing in 1890 at 19 Boston Street.

Professor Benjamin Ray conducted research that pinpointed the McCarter house’s location and worked with geographic information system specialist Chris Gist of the University of Virginia’s Scholars Lab to determine whether, in fact, it was possible for a person standing at the site of the house on the Boston Street to see the top of Proctor’s Ledge, given the rising topography of the northeastern slope of the hill. Gist produced a view-shed analysis, which determined that the top of Proctor’s Ledge was clearly visible from the Boston Street house, as well as from neighboring homes. However, the traditional site on the top of Gallows Hill was not visible from the houses.

Meanwhile, Professor Peter Sablock carried out geo-archaeological remote sensing on the site with a team of his Salem State geology students. Ground-penetrating radar and electronic soil resistivity do not disturb the soil, but can tell us about the ground underneath. His tests indicate that there is very little soil on Proctor’s Ledge. There are only a few small cracks in the ledge, and here the soil is less than three feet deep—certainly not deep enough to bury people.

Although it is admittedly negative evidence, this finding is in keeping with oral traditions that the families of the victims came under cover of darkness to recover loved ones and rebury them in family cemeteries. There is no indication that there are any human remains on the Proctor Ledge site.

The witch trials have cast a long shadow over Salem’s history. For generations, many residents wanted to forget the trials, and refused to acknowledge their community’s role in one of the great injustices in American history. The fact that the execution site has been “lost” more than once speaks to a collective amnesia and desire to forget. Yet, others, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, have tried to have the site properly marked. In 1835, in “Alice Doane’s Appeal,” Salem’s famous son laments the lack of memorial for “those who died so wrongfully, and, without a coffin or a prayer.”

In 1892, on the bicentennial of the trials, an effort was made to build a memorial on Gallows Hill, but it failed. The memorial was to take the form of a lookout tower—a popular monument of the day, as they were constructed on the high ground of Civil War battlefields to honor the dead and provide a peaceful and reflective place to view the battlefield. Indeed, the large lookout memorial at Gettysburg’s Little Round Top was dedicated in 1893. This is just one of many interesting comparisons between Gettysburg and Salem—two communities whose identities and economies are linked to a great American tragedy.

We are seeking a much more modest memorial for Gallows Hill than the Civil War veterans proposed in 1892. The City of Salem, led Mayor Kim Driscoll, plans to clean the heavily wooded Proctor’s ledge parcel up, maintain it, and install a tasteful plaque or marker. I believe that marking and maintaining this site is a long overdue step in Salem’s acknowledgement of the role the community played in the loss of innocent lives in 1692. The healing process continues 324 years after the trials.

I concluded my recent book on the Salem witch trials, A Storm of Witchcraft, by lamenting the fact that despite efforts going back to the nineteenth century, there still was no memorial on Gallows Hill. I am delighted that the last line of my book will soon be out of date.

Image Credit: Proctor’s Ledge on Gallows Hill, Salem. Photo courtesy of Emerson W. Baker.

The post A memorial for Gallows Hill appeared first on OUPblog.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense turns 240 years old

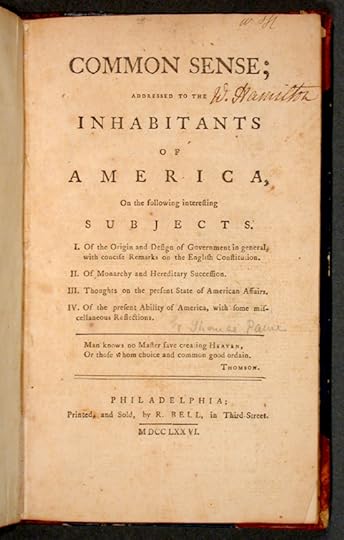

This extract is taken from Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense, published 10 January 1776.

Of the Origin and Design of Government in General, with Concise Remarks on the English Constitution

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not only different, but have different origins. Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness; the former promotes our happiness positively by uniting our affections, the latter negatively by restraining our vices. The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions. The first a patron, the last a punisher.

Society in every state is a blessing, but government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence; the palaces of kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of paradise. For were the impulses of conscience clear, uniform, and irresistibly obeyed, man would need no other lawgiver; but that not being the case, he finds it necessary to surrender up a part of his property to furnish means for the protection of the rest; and this he is induced to do by the same prudence which in every other case advises him out of two evils to choose the least. Wherefore, security being the true design and end of government, it unanswerably follows that whatever form thereof appears most likely to ensure it to us, with the least expence and greatest benefit, is preferable to all others.

In order to gain a clear and just idea of the design and end of government, let us suppose a small number of persons settled in some sequestered part of the earth, unconnected with the rest, they will then represent the first peopling of any country, or of the world. In this state of natural liberty, society will be their first thought. A thousand motives will excite them thereto, the strength of one man is so unequal to his wants, and his mind so unfitted for perpetual solitude, that he is soon obliged to seek assistance and relief of another, who in his turn requires the same. Four or five united would be able to raise a tolerable dwelling in the midst of a wilderness, but one man might labour out of the common period of life without accomplishing any thing; when he had felled his timber he could not remove it, nor erect it after it was removed; hunger in the mean time would urge him from his work, and every different want call him a different way. Disease, nay even misfortune would be death, for though neither might be mortal, yet either would disable him from living, and reduce him to a state in which he might rather be said to perish than to die.

Thus necessity, like a gravitating power, would soon form our newly arrived emigrants into society, the reciprocal blessings of which, would supersede, and render the obligations of law and government unnecessary while they remained perfectly just to each other; but as nothing but heaven is impregnable to vice, it will unavoidably happen, that in proportion as they surmount the first difficulties of emigration, which bound them together in a common cause, they will begin to relax in their duty and attachment to each other; and this remissness, will point out the necessity, of establishing some form of government to supply the defect of moral virtue.

Image credit: Scan of cover of Common Sense, the pamphlet, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Scan of cover of Common Sense, the pamphlet, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Some convenient tree will afford them a State-House, under the branches of which, the whole colony may assemble to deliberate on public matters. It is more than probable that their first laws will have the title only of Regulations, and be enforced by no other penalty than public disesteem. In this first parliament every man, by natural right, will have a seat.

But as the colony increases, the public concerns will increase likewise, and the distance at which the members may be separated, will render it too inconvenient for all of them to meet on every occasion as at first, when their number was small, their habitations near, and the public concerns few and trifling. This will point out the convenience of their consenting to leave the legislative part to be managed by a select number chosen from the whole body, who are supposed to have the same concerns at stake which those who appointed them, and who will act in the same manner as the whole body would act were they present. If the colony continue increasing, it will become necessary to augment the number of the representatives, and that the interest of every part of the colony may be attended to, it will be found best to divide the whole into convenient parts, each part sending its proper number; and that the elected might never form to themselves an interest separate from the electors, prudence will point out the propriety of having elections often; because as the elected might by that means return and mix again with the general body of the electors in a few months, their fidelity to the public will be secured by the prudent reflexion of not making a rod for themselves. And as this frequent interchange will establish a common interest with every part of the community, they will mutually and naturally support each other, and on this (not on the unmeaning name of king) depends the strength of government, and the happiness of the governed.

Here then is the origin and rise of government; namely, a mode rendered necessary by the inability of moral virtue to govern the world; here too is the design and end of government, viz. freedom and security. And however our eyes may be dazzled with show, or our ears deceived by sound; however prejudice may warp our wills, or interest darken our understanding, the simple voice of nature and of reason will say, it is right.

Image credit: “Thetford (Norfolk), Thomas Paine statue” by Ziko-C, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thomas Paine’s Common Sense turns 240 years old appeared first on OUPblog.

What are the hidden effects of tax-credits?

UK tax-credits are benefits first introduced in 1999 to help low-paid families through topping up their wages with the aims of ‘making work pay’ and reducing poverty; although they also cover non-working families with children. Recently the Chancellor of the Exchequer proposed cutting the annual tax-credit budget, which would have reduced the average annual tax-credits and benefits claim of working households by around £750 per year. After being rejected by the House of Lords, the proposed changes have now been abolished. Rightly, public debate has been directed towards the immediate effects of the cuts on poverty and household incomes. But tax-credit programmes can also create and change the incentives associated with lifestyle choices and behaviours in a number of socio-economic domains that also have implications for the wellbeing of recipients and their children.

Evidence shows that in many cases UK tax-credits helped individuals into work, which raised the income and consumption of poor households. However, it may be that this impacts the decision to have children, and it will also affect how much time parents have available to spend with their children. Already, we can see that the incentives created by tax-credits may lead to a chain of events that are complicated, and enter corners of people’s lives that may have been unintended.

Whilst tax-credits have often been portrayed as a brainchild of the last Labour government in the UK, a number of other Western countries, including the United States, Canada, New Zealand, France, and Belgium successfully operate their own versions of the programmes. Academics have thought carefully about the ways in which tax-credit programmes may change incentives, and how the wellbeing of recipient families and their children are affected. So what are some of the less obvious potential impacts of tax-credit changes that could be of public concern?

Image credit: Penny Guts, by Johanna Hardell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Penny Guts, by Johanna Hardell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Higher birth-rates: Could tax-credits programmes encourage recipients to have more children, or as one peer claimed in the previous parliament “encourage the poor to breed?” Whilst it is true that tax-credit programmes would lower the price of having an additional child and therefore increase the ‘demand for children’, there are also effects that operate in the other direction. For example, when having an additional child, women induced into employment by tax-credits now have more to lose in terms of foregone earnings. What does the UK evidence tell us about these effects? Some studies have found that work conditions have raised the fertility of certain subgroups of the population, whilst others have found the opposite for different subgroups. Overall, the picture is complicated and it is not possible to conclude that tax-credit programmes universally encourage or discourage families to have more children.

Increase in children’s scores on academic tests: One study found that children in low- to middle-income families who benefitted most from expansions of US tax-credits in the late-1980s and mid-1990s saw improvements in maths and reading scores, relative to higher-income families. Other researchers similarly found that increases in family income generated by differences in child tax benefit rules across Canadian provinces lead to improvements in educational achievement. In so far as this raises the future productivity and wages of disadvantaged children, the programme should foster economic growth in the countries concerned.

Low income families become more like middle income families in their expenditure patterns: Gregg et. al (2006) analysed how household spending patterns changed following the introduction of UK tax credits (and other anti-poverty programmes) in 1999. They find that low-income families with children increased their spending on children’s clothing and footwear, fruit and vegetables, and books. Perhaps more surprising is that their evidence shows that low income families reduced spending on alcohol and tobacco, and so became more like middle income families. It is not clear why this should be the case, but it could be due to a decrease in stress given their improved financial position.

Negative effects of family break-up on mothers and children are cushioned: since the introduction of UK tax credits, there is evidence of substantial beneficial effects for adolescent children growing up in lone parent families, showing improvements in measures of self-esteem, unhappiness scores, truanting measures, smoking, and planning to leave school at age 16.

Determining the influence each spouse has in family decision making: Because a household is composed of various individuals, conflicts of interest arise. One recent UK paper finds that when tax-credits were paid to women instead of men, the composition of household spending changed in a way that favoured women and children over men.

While the Government has been interested in cutting spending on tax-credits to reduce the budget deficit and much of the public discussion has focused on the direct effects on household incomes, there is likely to be a complex set of other behavioural changes. As many of these relate to the wellbeing of children and their future productivity, they deserve serious discussion.

Featured image credit: British Coins by William Warby. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What are the hidden effects of tax-credits? appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe

The OUP Philosophy team have selected Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe (18 March 1919 – 5 January 2001) as their January Philosopher of the Month. Anscombe was born in Limerick, Ireland, and spent much of her education at the University of Oxford and University of Cambridge. An analytical philosopher, Anscombe is best known for her works in the philosophy of mind, action, language, logic, and ethics.

Anscombe had a close relationship with her mentor, Ludwig Wittgenstein. She would end up translating many of his books and papers, including Philosophical Investigations. Much of his influence can be seen in her writings, including her seminal monograph, Intention. Anscombe was a formidable debater and engaged with long discussions with students and faculty members while a professor at the University of Cambridge. She is also known for her high profiled debate with C.S Lewis, which resulted in Lewis re-writing parts of his book, Miracles.

Anscombe was a social activist, much of this guided by her Catholic religious beliefs. She opposed Britain’s entering World War II and the deployment of the atomic bomb because of the amount of civilian deaths it caused. She was staunchly against abortions and attended various sit-in protests.

Anscombe died at the age of 81 on January 5, 2001 in Cambridge, England. She was survived by her husband, philosopher Peter Geach, and their seven children.

Featured image credit: ‘The Thinker’, by Rodin. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Gertrude Elizabeth Margaret Anscombe appeared first on OUPblog.

January 12, 2016

Cultural foreign policy from the Cold War to today

When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its nominees for the 2015 Academy Awards, the James Franco/Seth Rogen comedy The Interview wasn’t on the list. That the Oscars spurned this “bromance” surprised nobody. Most critics hated the film and even Rogen’s fans found it one of his lesser works.

Those audiences almost didn’t have a chance to see the film. The Interview, of course, centers on a half-baked but accidentally successful plot to assassinate North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. North Korea, though, didn’t like jokes about the murder of its leader. In one of the most remarkable episodes in the recent history of the entertainment industry, a group of computer hackers calling itself the “Guardians of Peace” (linked later with the North Korean government) infiltrated the computer servers of Sony Pictures, shutting down the studio’s communications and throwing its data open for anyone to see. The “Guardians” demanded that Sony scrap The Interview, and the studio acquiesced if only for a moment.

Apart from some of the obvious questions here—has Hollywood so convinced itself that the Kims are cartoon villains that it thought it could play up the assassination of a sitting foreign leader for laughs? Would a studio greenlight a comedy about the killing of Vladimir Putin or Bashar al-Assad?—this incident evokes the larger issue of the place of art and popular culture in international relations. Does the US really want smirking irony to be the face of our culture? What sorts of art and culture would tell the stories we want to tell foreign populations about who we are?

Currently, two of our greatest foreign-policy challenges (the confrontation with fundamentalist Islamism, and the standoff with an expansionist Russia) have important cultural dimensions. Both Islamism and Putinism put themselves forward to the world as defenders of traditional values, and depict American popular culture as a threat to those values. How should the US respond to this? As the Cold War began, both adversaries and allies viewed the US as having nothing to offer the world but military and economic domination and a crude, violent, hypersexualized popular culture. American cultural diplomats had to win over skeptical intellectuals in allied nations, and counteract enemy propaganda generated by the Soviet Union that we were just Mickey Mouse and cowboy movies. Even American politicians were concerned with this. In House and Senate hearings, elected officials worried about the effect of exporting movies like The Blackboard Jungle and Tobacco Road, books like Edmund Wilson’s Memoirs of Hecate County, or trashy paperbacks with lurid covers. In response, the US offered up not just high culture, but avant-garde high culture. The US government and cultural organizations organized exhibitions full of abstract expressionists and non-figurative painting, subsidized publication of American modernist writers abroad, sent William Faulkner on goodwill tours, and asked modernists like William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore to talk about their hometowns on Voice of America radio.

It worked. By the end of the 1950s, Europeans who had scoffed at the very idea of “American culture” were enthusiastic about its writers and artists, and—perhaps more importantly—about how American art expressed the values of freedom and individualism.

What relevance does “Cold War modernism” have today? Primarily, that what makes popular culture so appealing and satisfying—its snappiness, its immediacy, its ironic comments that so quickly become dated—are also its dangers. Pop culture, whether The Blackboard Jungle or The Interview, is ephemeral. Pop culture seeks a quick and intense response from a broad public; whether that response is rapturous or furious doesn’t matter.

Cold War modernism, by contrast, was aimed at cultural elites, intellectuals, opinion-makers. Strategists in the State Department and Ford Foundation reasoned that once they converted those people, their influence would sway the larger populations. Then, positively disposed toward the US, these larger populations would see that America wasn’t just its shallow—but often appealing—pop culture. We sometimes tell ourselves the glib story that Coca-Cola, Levi’s, and Bon Jovi brought the USSR down, but that leaves out decades of careful work by cultural diplomats who won the respect of dissident intellectuals.

Of course, it’s likely that no kind of cultural diplomacy would work with North Korea, whose regime needs to foment periodic confrontations with the West in order to maintain control. Putinism seems to have a similarly cynical basis. The Middle East, though, could be different. For decades, even as our diplomacy supported repressive governments in Egypt and Iraq and Iran, cultural diplomats simultaneously reached out to liberals and intellectuals and—through exchange programs and cultural events and American libraries and the like—earned their admiration. A revival of that program could help the forces of moderation in at least some of those volatile places.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Columbia University Press blog.

Featured image credit: “Visitors bowing in a show of respect for North Korean leaders Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il on Mansudae (Mansu Hill) in Pyongyang, North Korea.” by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cultural foreign policy from the Cold War to today appeared first on OUPblog.

Infiltrating the Dark Web

Law enforcement agencies are challenged on many fronts in their efforts to protect online users from all manner of cyber-related threats. Through constant innovation, cybercriminals across the world are developing increasingly sophisticated malware, rogue mobile apps, and more resilient botnets. With little or no technical knowledge, criminals now occupy parts of the Internet to carry out their illegal activities within the notorious Dark Web.

Publicly available, but with highly sophisticated encryption, the specific group of websites that coalesce as the Dark Web provide an environment for contemporary villains to anonymously carry out their illegal activities. From inciting violence to human trafficking, the use of cyber space to plan, conduct and commit crime significantly stretches the traditional physical, legal, and structural boundaries of policing practices. Cybercrimes cut across the current tiers of police prioritisation frameworks, from lower level crimes of online bullying, to the more serious and organised crimes of sexual exploitation of children, drug trafficking, and terrorism.

The totality of cybercrimes organised within the Dark Web now requires a fresh approach to bring cybercriminals to justice and to restore law and order to the Internet. While law enforcement agencies across the world are in reality just beginning to understand the full extent of online crimes, and are gaining a richer picture of the challenges they face in policing cyberspace, significant investment in their capacity and capability is required to effectively tackle and infiltrate the Dark Web.

The plotters and conspirators who frequent the Dark Web will continue to evolve at a pace beyond the reach of traditional law enforcement methods.

Unfortunately, there is no technological or legislative ‘silver-bullet’ solution to tackling the Dark Web. Criminals conducting online abuses, thefts, frauds, and terrorism have already shown their capacity to defeat Information Communication Technology (ICT) security measures, as well as displaying an indifference to national or international laws designed to stop them. The uncomfortable truth is that as long as online criminal activities remain profitable, the miscreants will continue, and as long as technology advances, the plotters and conspirators who frequent the Dark Web will continue to evolve at a pace beyond the reach of traditional law enforcement methods.

There is, however, some glimmer of light amongst the dark projection of cybercrime as a new generation of cyber-cops are fighting back. Nowhere is this more apparent than the newly created Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce (J-CAT) within Europol, who now provide a dynamic response to strengthen the fight against cybercrime within the European Union and beyond Member States borders. J-CAT seeks to stimulate and facilitate the joint identification, prioritisation, and initiation of cross-border investigations against key cybercrime threats and targets – fulfilling its mission to pro-actively drive intelligence-led actions against those online users with criminal intentions. Supporting INTERPOL last year, cybercrime fighters from Europol have already struck back at cybercriminals by helping to take down the servers of the infamous Darkbot botnet, which has been infecting millions of computers since 2011.

The J-CAT model of operating now provides a blueprint for combating cybercrime trends. Law enforcement agencies are increasingly in favour of intelligence-driven security approaches which can operate in mobile and cloud environments. Such an approach makes greater use of behavioural analytics and takes full advantage of smart device capabilities to protect users and data. Even if attacks cannot be blocked completely, having access to the right intelligence makes it possible to detect an attack more quickly, significantly reducing the attacker’s window of opportunity and minimising the potential for loss or damage.

While law enforcement agencies continue to prepare and equip themselves for the future fight against users of the Dark Web, they are taking positive strides to disprove the incorrect perception that real world laws do not apply online. The police are now showing that online harassment, intimidation, threatening behaviour and organised crime will not go unpunished. Furthermore, they are developing increasingly effective collaborative approaches to bring cybercriminals to justice – all of which requires a dedicated and determined response to pursue them to the very darkest corners of the web.

Featured image credit: deep cover graphic base by Jeff Mikels. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Infiltrating the Dark Web appeared first on OUPblog.

In memoriam: Pierre Boulez

I’ve been very struck over the past couple of days listening to the testimony of so many musicians who worked with Pierre Boulez. They all seem to say the same thing. He had a phenomenal understanding of the music (his own and that of others), he had an extraordinary ear, and he was a joy to work with because he gave so much. You can see evidence for this in footage of him with young musicians at the Lucerne Academy he founded. Yes, he’s tough, because he has the highest of expectations, but at the same time he’s warm, kind, and generous.

It’s rather a pity, then, that – in the popular imagination at least – Boulez’s initial reputation as an ‘angry young man’ seems to have coloured the reception of his entire career. It’s true that in his earlier years he was combative. There was much to which he took exception. And how many students worthy of the name have not fought against the dominant values of the preceding generation? It was certainly clear in 1945 to Boulez (then aged 20) and his avant-garde peers that their forebears had got much wrong. Boulez organized booing and whistle blowing at a performance in Paris of Stravinsky’s Four Norwegian Moods. In ‘Schoenberg est mort’, the least generous obituary ever, he condemned the Viennese reformer for having reneged on his own revolutionary ideals. And he famously told his own teacher Messiaen that he thought little of the Turangalîla Symphony, describing it as ‘brothel music’. As recognition and influence came his way, Boulez became less pugilistic, though the tendency never entirely deserted him.

It’s fascinating, then, to look at video footage of Boulez conducting. Early on, his hard, mechanistic gestures (in one film even wearing dark glasses to keep any facial expression hidden) seem to embody his high-modernist aesthetic: no room for emotion; structure is everything. His readings of Webern are instructive in this regard. Structures Ia and the Second Piano Sonata breathe similar air, brazenly rejecting or destroying the traditions of the past in favor of a new structural order. But when you watch later films, you see that his movements have become more fluid, encouraging a balance between the structural and the decorative, the expressive even. And I find the same in his later music. Répons, a work I adore, is on the face of it another product of the high-modernist aesthetic of progress, pushing at boundaries, responding to the challenges of the latest technology. Yet its musical gestures – even those generated by the machines – often appear to take pleasure in the moment, in the shape and color of the sound, dwelling on the beautiful. In fact, that tendency had always been there in Boulez, stemming in part from an understanding of Debussy, so important to anyone who had passed through La classe de Messiaen. If in doubt, then listen to the gorgeous first song of Le Soleil des eaux.

It’s all too easy for musicologists to ‘fix’ through the labels they apply. The ‘avant garde’ and ‘integral serialist’ tickets attached to Boulez (often encouraged, it has to be said, by the man himself) place him squarely within a still-dominant narrative of modernity that goes back at least to Beethoven via Schoenberg and Brahms. But this, for me, hides the richness of the musical legacy he leaves, which opened up a dialogue of exceptional subtlety with all manner of music and ideas from across the 20th century. Boulez as structuralist, Boulez as high modernist: these accounts ultimately fail to do justice to a body of work that, for me, speaks with generosity of the uncertainties, vulnerabilities, and pleasures of what it means to be human in the 21st century.

Pierre Boulez

26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016

Image credits: (1) Abstract. (c) dimapf via iStock. (2) Pierre Boulez, 28 February 1968. Photo by Joost Evers / Anefo, Nationaal Archief. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In memoriam: Pierre Boulez appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers