Oxford University Press's Blog, page 558

January 22, 2016

Name that plague! [quiz]

Though caused by microscopic agents, infectious diseases have played an outsized role in human history. They have shaped societies, lent us words and metaphors, and turned the tide of wars. The earliest treatments for infectious diseases relied on plants like quinine and on isolating the sick. Modern medicine, however, has enabled a whole range of treatments, from antibiotics to vaccines. Humans have eliminated some diseases, but others continue to plague us. In this quiz, find out if confusion is contagious or if you’re immune to the challenge.

Headline image: Original image by Gerhart Altzenbach of Cologne. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

January 21, 2016

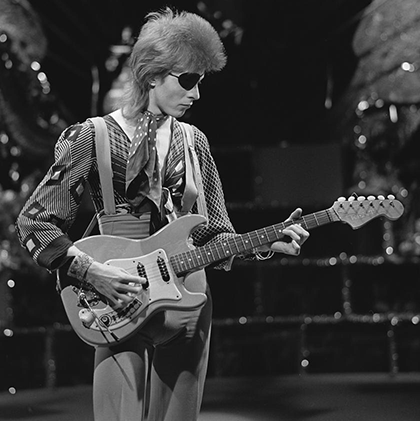

David Bowie: Everything has changed, he changed everything

Though David Robert Jones, the boy from Brixton, is no longer with us, David Bowie, the artist, through his music, films, plays, paintings, and explorations of gender, sexuality, religion, love, fear, and death, remains.

In what seemed to be a creative life constantly in flux, living up to the postmodern imperative of perpetual change, David Bowie was an utterly consistent artist. Each album noticeably has the Bowie sound, even when it sounds disparate from the others—a sound that makes them timeless. He elegantly shifted between expressing himself through music, theatre, film, and painting with an air of grand experimentation and extravagant ambition. David Bowie was an inspiration to countless artists from Marilyn Manson to Madonna, Kanye to Radiohead, all of whom cite him as an influence. His impact can be observed in many ways, be it hearing echoes of his distinctive voice, his utilization of new technologies and methods in the studio, his practice of bringing outlandish fashion to music, his ability to blend musical genres to create a novel sound, or his complete commitment to embodying a song in performance.

Outside the V&A Shop during the David Bowie exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo by Tiffany Naiman 2013.

Outside the V&A Shop during the David Bowie exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Photo by Tiffany Naiman 2013.David Bowie’s career spanned five decades and his impact on popular music since the 1960s is unmatched. In each decade of his career, Bowie brought underground music to the fore, taking the avant-garde and often making it commercially successful. Starting as a folk singer in the 1960s, he moved on to revolutionize rock and experimental music twice in the 1970s — first with glam rock and then with the arty and brooding synthesizer-infused Berlin Trilogy recordings made with Brian Eno. During the height of his commercial success in the mid-1980s, he topped the charts with modified New Wave pop music infused with the grooves of his plastic soul era. Bowie innovatively utilized the sounds of electronica, industrial, and drum & bass during his return to creating art rock in the 1990s and early aughts. An early pioneer in digital music, Bowie was among the first to offer music to purchase and download from his own website, starting with the release of his single “Telling Lies” in 1996. More recently, he made his first single and corresponding video from his critically acclaimed 2013 album, The Next Day, “Where Are We Now?” available on iTunes and his personal website with no advance fanfare — an action that demonstrated his mastery of the social nature of the Internet and would later be duplicated by Beyoncé. With his final record Blackstar (2016), he created some of the most brilliant and groundbreaking art of his career while directly confronting his own mortality. The form and structure of his recordings, music videos, and live performances explore the limits of the mediums in ways that disrupt the normative practice of rock music.

In 1996 David Bowie was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame by former Talking Heads front man David Byrne with the words “He was both kind of a shrink and a priest, a sex object and a prophet of doom. He was kind of the welcome to the new world, to the brave new world.” Madonna accepted the honor for him that night, describing her first teenage experience of David Bowie as a performance of “great theater” that changed and inspired her. As presenters and representatives of Bowie at his induction, Byrne and Madonna exemplified the dual nature of David Bowie as a musical artist: the rock star who creates art music, and the highly produced pop star reveling in artificial and visually engaging spectacle. David Bowie’s music, personae, and elaborate visuals contributed to popular music, performance, and aesthetics, pushing the boundaries of rock and pop music and expanding the definition of the modern popular musician.

David Bowie, shooting his video for Rebel Rebel in 1974. Photo by AVRO. Beeld en Geluid Wiki, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

David Bowie, shooting his video for Rebel Rebel in 1974. Photo by AVRO. Beeld en Geluid Wiki, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Scholarship on David Bowie is still nascent, but the growing body of work on him has tended to focus on themes of darkness, alienation, and death in his music, often ignoring what I see as a basic tenet that underpins his oeuvre and one of his most prevalent themes—love. Bowie stated, “When you are young you think so much is important, including oneself, but as you get older I think you find less and less is important apart from some very fundamental things—one of them being a love of one’s fellow man.” Examination of his career shows he has always emphasized this type of love. Bowie sang of alienation, but not a nihilistic or irreparable one; it was a disaffection forged from an awareness of the existence of powerful love, at times inaccessible. Bowie expressed human needs in an alien guise, opening the possibility for connection with something that is both us and “other.” From a place of deep isolation, his distinctive voice yearns for connection, allowing him to speak to all who felt they were outsiders, unable to fit into the world around them. Though his created dystopian worlds were filled with violence, perversion, and excess, there was always hope for transformation through love. This is David Bowie’s continued legacy; he pointed us toward our own transformations and potential through his own: “I’m not a prophet / or a stone age man / Just a mortal / with the potential of a superman.”

Headline image credit: David Bowie Graffiti. Photo by Louise McLaren. CC BY 2.0.

The post David Bowie: Everything has changed, he changed everything appeared first on OUPblog.

January 20, 2016

How did hiring begin?

Those who read word columns in newspapers and popular journals know that columnists usually try to remain on the proverbial cutting edge of politics and be “topical.” For instance, I can discuss any word I like, and in the course of more than ten years I have written essays about words as different as dude and god (though my most popular stories deal with smut; I have no idea why). Journalists cannot always afford such luxury and either answer the most provocative questions from their readers or react to the latest events. For example, the President or some other important person said that we should put an end to “this boondoggle” (an imaginary example). Columnists jump on the bandwagon (or waggon, depending on where they live and how archaic they want to look) and discuss the origin of boondoggle. I too want to be popular, have a huge following, and cater to (or for, again, depending on where you live) millions of readers eagerly awaiting my essays. So today I decided to be political.

The idea of treating the word in the title is topical (to me) because my department has for years been trying to replace the faculty members who retired, semi-retired, or left for the greener grass on the other side of our campus. Sadly, some of our old friends have joined the choir invisible, while students are very visible (may they remain such forever!) and need instructors, preferably faculty member rather than adjuncts. Students are not particularly rank-conscious (they may even try to ingratiate themselves with a teaching assistant by calling a graduate student professor); yet they know something about our trials and tribulations. Bearing in mind the woes of Academia, I will devote this post to the history of the verb hire.

Now and forever: very Germanic and germane to the subject.

Now and forever: very Germanic and germane to the subject.Strangely, this verb, though it existed in Old English (hyran, with long y) and has cognates elsewhere in West Germanic, has been declared a word “of uncertain origin.” In this context, no one knows the difference between uncertain, obscure, disputable, and unknown. Unknown perhaps means that nothing at all can be said about the history of the word; all the others seem to be interchangeable. In any case, no dictionary explains where Old Engl. hyran came from. But I think I do know the answer and hasten to enlighten the world. Some people may have read books with titles like Useful Knowledge (from William Bingley, 1816, to Gertrude Stein, 1929) and Nuggets of Knowledge. I am eager to supply a useful nugget.

It will be fair to say that, unrelated to the history of my department, my interest in the verb hire was piqued by a chance encounter with a note in the 1896 volume of The Nation. In the past, such periodicals regularly printed short articles on words and detailed reviews of dictionaries. Even not too long ago The New Yorker and Scientific American brought out significant publications on word histories. Today this practice seems to be dead. In The Nation, Fitzedward Hall, at that time a well-known authority and a caustic writer on the English language, suggested that the phrase hired man had been derived from Old Engl. hired “retinue, troop.” He repeated his idea in the next issue of The Nation for the same year, and, undoubtedly, believed that this idea had not occurred to anyone before him. To begin with, the idea is wrong, so that there was nothing to be particularly happy about. Second, Hall found himself in a situation familiar to most etymologists. He was not the first to connect hire and Old Engl. hired. John Minsheu offered the same conjecture in his 1617 (!) dictionary, Skeat toyed with it in 1882 but gave it up almost at once, and in 1910 Friedrich Kaufmann, a distinguished scholar of Germanic antiquities, repeated it. Both Skeat and Kaufmann were ignorant of their predecessors’ works on the verb hire. Having compiled a voluminous bibliography of English etymology, I know almost too well, how often students of word histories reinvent etymological wheels.

A look at old sources yields a most unimpressive list of the putative etymons of hire. Those Greek, Latin, and even Germanic words are not worth reproducing, let alone discussing here. Closer to our time, it has been suggested that hire is akin to Hittite kuššan “pay, fee, wages, price.” Hittite, it will be remembered, is an ancient Indo-European language that was spoken more than three thousand years ago by the people who inhabited what is now part of Turkey (Anatolia). Today it is dead. Some Hittite-Germanic parallels exist, though, as a matter of principle, it always causes surprise when we discover that an old Indo-European word has a reflex only so far in the east (in our case, in Turkey) and in the west (with regard to hire, in English, German, Dutch, and Frisian). One expects that some traces of the word would also have been extant somewhere in between. However, the discovery of the hire—kuššan parallel has been hailed as a welcome breakthrough in the difficult search for the origin of hire.

I have some vague ideas about the etymology of the Hittite noun, but they can be passed over in this essay. Suffice it say that, in my opinion, kuššan and hire have nothing to do with each other, for I believe that hire has the simplest Germanic etymology imaginable. There must have existed a West Germanic verb husján, with long u in the root and stress on the ending, for all –jan verbs had final stress. Its root was hus “house,” and the verb meant “to house.” By a rule known as Verner’s Law, Germanic spirants (a spirant is a consonant like f, s, and so forth, as opposed to a stop, that is, p, t, k, etc.) were voiced if stress followed them. Consequently, husján (whose existence I here assume) became huzján. Finally, such z in West and North Germanic became r (this process is called rhotacism); j caused umlaut, by which long u turned into long y; stress, as always in Germanic, was later shifted to the root, and the final product was hyran, the form recorded in Old English. Its modern reflex is hire.

A boondoggle: hard to produce, easy to etymologize

A boondoggle: hard to produce, easy to etymologizeI must apologize for the wealth of technical detail in the paragraph above, but etymology cannot always be discussed without recourse to such concepts as spirant, long vowel, final stress, initial stress, umlaut, rhotacism, and the like. Boondoggle would have been easier to explain. For the benefit of those who are bewildered by my presentation I will cite two parallels. Gothic has come to us as the language of the New Testament, so, naturally, the verb meaning “to save” occurs there more than once. It sounded as nasjan; its Old English cognate was nerian (e is the umlaut of a). The Gothic for “hear” was hausjan; the English etymon of hear is hieran ~ heran. Almost as though to confirm my reconstruction, speakers of Old English coined the verb husian “to receive into the house.” Husian was a late coinage, and therefore it underwent neither umlaut nor rhotacism and always had stress on the first syllable, but it was short-lived and did not continue even into Middle English, possibly ousted by its near synonym hyran.

If I am right, hire surfaced with the sense “to house,” possibly “to take into the house as a paid servant.” It was a neologism and remained confined to a rather narrow area. That is why it has no cognates in Greek, Latin, and elsewhere. Few etymological solutions are final, but the reconstruction offered above seems to possess a high degree of verisimilitude. Compare my discussion of Occam’s razor in etymology.

Image credits: (1) household staff of Curraghmore House, Portlaw, Co. Waterford, circa 1905. National Library of Ireland. Public domain via Flickr. (2) “Now hiring drug free workplace” in New Berlin, Wisconsin. Photo by jay from cudahy. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3) Yellow Boondoggle. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How did hiring begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

Q&A with Matthias Siepe

Oxford University Press is pleased to welcome Matthias Siepe as the new Editor-in-Chief of Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery (ICVTS). We got to know Matthais during an interview and discovered how he came to specialise in cardiovascular surgery, how he sees this field in the future, and what he has in store for ICTVS.

What encouraged you to pursue a career in the field of cardio-thoracic surgery?

As a third year medical student, I attended a research project of one of my fellow students. Hearts from non-heart-beating donors were transplanted into a porcine model. I was astonished by this work and thrilled to watch the heart start beating after the arrest period.

I was a member of this group for the following four years and performed several experiments while on this team, including the first surgical procedures I did myself. After finishing university, it felt natural to simply continue with my experimental work, and develop my education at the Cardiovascular Clinic – this felt like the logical career path.

What do you think are the challenges being faced in this field today?

The high degree of professionalisation in many procedures, and the new technology available for various indications have led to clear specialisation within our field. We have TAVI specialists, VATS specialists, aortic specialists, minimal-invasive mitral specialists, off-pump CABG specialists, et cetera. On top of that, there is in many fields significant overlap with our colleagues the interventional cardiologists, radiologists, pulmonologists, or angiologists. Ideally, these “neighbouring” specialists form a multidisciplinary team. Such multidisciplinary activities impact on treatment quality in a very positive way. The drafting of common guidelines informs this development.

However, the challenges occur in less advantageous circumstances, where specialist groups in centres might counteract each other. Whenever that happens, there is a chance that the quality of patient care is compromised, adequate training is impossible, and the professional atmosphere is destroyed.

Matthais Siepe, the new Editor-in-Chief for ICVTS. Authors’ own photograph.

Matthais Siepe, the new Editor-in-Chief for ICVTS. Authors’ own photograph.How do you see cardio-thoracic surgery developing in the future?

The sub-specialisation in our surgical field together with the neighbouring disciplines makes the matrix-like structures of clinics necessary. Some may think that by working together in a team to treat coronary heart disease, that the surgeon’s role is lost in the interventionist department; however this is not something that I fear. In hospital structures, this readjustment is certain to consume a lot of time and energy. We must ensure that surgical training and scientific developments are further improved in what is an undoubtedly changing environment.

What are you most looking forward to about being the Editor-in-Chief of ICVTS?

Coming into contact with and getting to know a lot of interesting people is such a major privilege in this position. Continuously being informed about leading-edge science in all fields is another privilege. I am deeply honoured to have been chosen for this position, and I will fill it with energy and respect.

How do you see the ICVTS developing in the future?

The ICVTS started as an exciting and innovative journal for the , whereby different publication types and interactive formats were tested. Most of the regular articles it published in the past few years were transferred from EJCTS. We are in the process of changing this, with an increasing rate of de novo submissions to ICVTS. With its Impact Factor allocation, the interactive Journal is in a strong position among other cardiothoracic surgical journals. I will work on sharpening the Journal’s innovative and interactive profile while enhancing its professionalism.

What do you think readers will take away from the ICVTS?

First and foremost, the ICVTS is a scientific journal, and we function from this professional perspective. We provide ICVTS readers with condensed and important practical information suitable for their daily routine (e.g. in the best evidence topic articles). I think that digesting this content should be fun. In order to make reading the ICVTS enjoyable, the aim is to make the content more appealing by including innovations, technical highlights and opinions from leaders in the field. The Journal’s appearance will not change much immediately, but it will change over time. We will continue to track the number of downloads, citations, and clicks of our content in order to adapt the Journal to its readers’ demands.

Featured image credit: Image provided by CC0 Public Domain via PixaBay.

The post Q&A with Matthias Siepe appeared first on OUPblog.

Why the junior doctors’ strike matters to everyone

Doctors in the UK are striking for the first time in over 40 years. This comes after months of failed talks between the government and the British Medical Association (BMA) regarding the controversial new junior doctor contract. We do so with a heavy heart, as it goes against the very ethos of our vocation. Yet the fact that more than 98% of us voted to do so, speaks volumes about the current impasse.

In 2012, long before any talk of a seven-day National Health Service (meaning routine services would be available all week) – our union, the BMA, began negotiating in good faith on a new contract. Two years later they walked away because the government were refusing to listen to their concerns; threatening to impose unsafe changes on doctors regardless.

Tens of thousands of us took to the streets, to social media, wrote letters to the press, met our MPs and talked to the public – we even recorded a hit single. Still, the government would not listen.

Finally, with the threat of strikes looming, and at the eleventh hour when it was too late to reinstate cancelled procedures, the government agreed to the very reasonable BMA request of talks mediated by Acas (the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service). Now these have failed because of government intransigence and, having exhausted all other options, we feel we have no choice but to strike before it is too late – and this contract is a reality.

Image Credit: ‘070809 Badge of Honour’ by Pete. Public Domain, via Flickr.

Image Credit: ‘070809 Badge of Honour’ by Pete. Public Domain, via Flickr.The latest offer is much improved. But important differences remain. Today’s effective system for monitoring our hours is being abolished. The proposed replacement is inadequate, leaving doctors vulnerable to being pressurised into working long beyond their rostered hours: something that can ultimately jeopardise patient safety. It’s like asking people to drive within the speed limit – while simultaneously removing speed cameras and fines.

There’s more. Under the new proposals, doctors working an 11 hour shift will get just one 30 minute break. Worse, there are no requirements for rest periods for those who provide an on call service overnight, when they could be called in frequently. These doctors could be asked to work both the day before and the day after one of these “non-resident” night shifts. Effectively we could be working 72 hours continuously. As this arrangement costs less and requires fewer rest provisions (less time away from work) than having resident staff, hospitals will have a powerful incentive to make such 72 hour shifts commonplace. Overworked and tired doctors make mistakes, so getting these arrangements wrong is tantamount to gambling with patients’ lives.

The government argues that these changes are needed to provide a seven-day service. Extra money is promised for the NHS, but our wage bill is set to stay constant (and for the record, we are not asking for a pay rise). The only way the sums add up, are if existing staff are stretched more thinly.

Eleven years ago, I quit my job as a management consultant in the business sector, to retrain as a doctor. I’ve lost count of the number of doctors who have asked me for advice about going in the other direction in the last six months. Morale is at a record low. Only 52% of doctors finishing their second year of work after graduating chose to stay in the NHS last year, down from 71% as recently as 2011.

Image Credit: ‘NHS Junior Doctors Protest’ by Birmingham Eastside. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

Image Credit: ‘NHS Junior Doctors Protest’ by Birmingham Eastside. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.The consequence has been vacancies in every specialty, with as many as half the posts in Accident & Emergency unfilled. The shortfall? It’s covered in part by the rapidly eroding goodwill of those doctors who stay, but increasingly by costly locum staff at the taxpayers’ expense. A new contract that encourages doctors to stay is urgently needed.

And this is the crux of it. There is a real danger that many doctors will leave rather than work under conditions they feel are unsafe and unfair. The government has refused to listen, risking patient safety in pursuit of a rash and ill-conceived manifesto commitment, to an as-yet undefined seven-day service.

As a taxpayer and a patient, I’m not worried about the strikes. Our consultants will ensure emergencies are covered, and patients are safe. I am concerned about a contract that prompts a mass exodus of doctors. That’s why, when junior doctors say they are striking to save the NHS, it’s not just rhetoric. The strikes really do matter to everyone – doctors, taxpayers, and patients alike – so if you care for the NHS, please support us.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Pedestrians, People, Busy’, by B_Me. CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post Why the junior doctors’ strike matters to everyone appeared first on OUPblog.

January 19, 2016

Miley Cyrus and the culture of excess in American history

Miley Cyrus has shocked the world anew with a recent CANDY Magazine photo shoot by over-the-top fashion photographer Terry Richardson. Cyrus sticks her tongue out with enthusiasm—and does much more. In one image, she is “dressed” in a police officer’s uniform, except that she is not wearing a shirt and a pair of handcuffs is displayed prominently. She appears to be sucking the end of a hard black police club. Such images come two years after Ms. Cyrus stunned millions of viewers at the MTV Music Video Awards in August 2013 with her twerking, and in a later performance, simulating sex with singer Robin Thicke. For many, Cyrus had gone too far or simply taken already stale assaults on taste—think here of Madonna or Iggy Pop’s on-stage performances years ago.

Going too far, pushing artistic boundaries, and blurring lines is by now a hallowed tradition, and it is useful to think about Cyrus within this context. We live in a culture of excess. Artists—especially young ones seeking a next step in their career—seek to push the envelope. Sometimes they succeed but usually after the fact. Perhaps someday Cyrus’s sexual gyrations will be seen as a Dionysian salvo in favor of sexual androgyny.

When John Cage, back in 1952, premiered his work for piano, 4’33”—the piece where a pianist sits at the piano for that time duration without striking a key—many considered the work disrespectful, childish, and an assault on musical propriety. When the piece was performed another time, John Cage’s mother was in attendance, and she remarked to a friend, “Don’t you think that John has gone too far this time?” Going too far, cutting against the grain of tradition, was Cage’s M.O. He had, earlier on, rigged pianos with nuts and bolts, had various radios tuned to different stations playing at the same time, and organized the first “Happening” (“Theatre Piece #1”) at Black Mountain College. During this 45 minutes of organized chaos, Cage, a few steps up a ladder, recited a lecture about something or nothing, painter Robert Rauschenberg played records on a Victrola (Edith Piaf songs, some recall), Merce Cunningham and some others weaved in some sort of dance, while Mary Caroline Richard and Charles Olson read poetry, and David Tudor played the piano.

“John Cage in 1988” by Rob Bogaerts. CC-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“John Cage in 1988” by Rob Bogaerts. CC-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Over 20 years later, Cage was up to his old tricks. In a new piece, Empty Words, Cage “demonstrated” that 27 different things could be done with a sentence. Parsing, splaying, and splitting sentences from Thoreau’s Journals, and employing his trusted method of using the I Ching to organize material, he offered four “lectures” to the audience. He knew that these lectures—which he read in his solemn basso voice—would confound and offend. Indeed, he had predicted as much on a radio talk show, telling listeners that tickets for the lectures would be easy to obtain soon after the start of the program: just wait outside the venue and folks would soon leave.

And with good reason. The concert was an A-bomb dropped on syntax, with silences of inordinate length punctuated by what seemed to be an occasional bird call. Meaningless, “non-syntactical writing” flowed from Cage’s lips: “Bou-a-the dherlyth gth db tgn-phl ng.” Got it?

The audience revolted at the hour-and-a-half mark, laughing, yelling, tossing objects onto the stage, and even improvising their own entertainment during lull periods. Poet Allen Ginsberg feared for Cage’s safety, so along with some pals he formed a protective cordon around the artist. Cage told the audience, “I know what limb I’m out on, I’ve known it all of my life.” The audience, he announced, needed to open itself up to the therapeutic value of boringness and meaninglessness.

Such affronts to audiences and artistic propriety have a long history in the twentieth century; think here of Dadaism in the years around the First World War. But Cage’s actions helped resuscitate art as performance and protest in the United States. This is not to argue that there is a direct line from Cage to Cyrus, but the artist as provocateur—passionate about going too far—has been a hallmark of American culture since Cage. Allow a few episodes to suffice as evidence.

The year after Cage’s 4’33”, his pal Rauschenberg displayed monochromatic paintings, as well as a box filled with dirt, on gallery walls. Most shockingly, Rauschenberg asked Willem De Kooning, then regnant in the art world, to give him, at no cost, a drawing. Rauschenberg was up front with his plans for the drawing—he wanted to erase it! DeKooning, no fool, knew that this was an act of Freudian revolt against an artistic father, as well as a wry critique of the value and permanency of the work of art. DeKooning gave Rauschenberg a work, done in charcoal, ink, crayon, grease and pencil, which he knew would resist to erasure. Rauschenberg erased away for a month—some have estimated that he employed close to forty gummy erasers – until only a taste of the original remained. The work was titled: Erased DeKooning. Today it is part of the permanent collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The tempo of artistic rebellion and willingness to go too far picked up steam in the 1960s, as would be expected. Think here of Warhol’s films, in particular, Empire (1964). Warhol set up an immobile camera in an office some 40 floors up in the Time-Life Building and then trained the lens on the Empire State Building across the street. Filming started around 8:00 p.m., just before sunset, and continued into the early morning hours. The result: a film eight hours long, focused on a building that personified the phallus. One wag remarked that the film was “an eight hour hard-on.” Excessive even for our Viagra age.

Over a few years in the 1970s, artist Chris Burden assaulted notions of what constituted art with his performances. Among his pieces: he had himself literally crucified against the sway back of a Volkswagen Beetle; in another he was contained in a two-foot high by two-foot wide by three-foot deep locker for five days. In Shoot (1971), in front of an audience of between eight and 12, Burden had himself shot in the arm. The plan had been for the bullet only to graze the arm but things did go awry. The piece was about shocking the audience, to be sure, but it also involved the audience in its logic. As art critic Maggie Nelson points out, in this piece as in many dangerous stunts by Burden, the ethical onus was on the audience to intervene. What was going to transpire was no secret to those in attendance; the invitation read: “I will be shot with a rifle at 7:45 p.m.” Burden left the performance hall bleeding, looking like he was in a state of shock. He later noted, the piece was intended to be “an inquiry” about the nature of art, the role of the body in performance, and more.

Such examples only skim the surface of outrageousness in American culture that long precedes Miley Cyrus’s gyrations and photo shoot. Perhaps someday Cyrus’s challenges will be logged into the tradition adumbrated above. Perhaps not. It is too soon to tell. But we should allow ourselves to be open to the role of artistic excess in pushing boundaries, opening minds, and trying to go too far.

Image Credit: “Miley Cyrus-Bangerz Tour” karina3094. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Miley Cyrus and the culture of excess in American history appeared first on OUPblog.

No time to think

On leaving school, my advisor reminded me to always take time to think. That seemed like a reasonable suggestion, as I trudged off to teach, write, and, of course, think. But the modern academy doesn’t share this value; faculty are increasingly prodded to “produce” more articles, more presentations, more grant applications, and more PhD students. Nobel prize-winner Peter Higgs remarked on the breakneck pace of today’s scholarship saying, “It’s difficult to imagine how I would ever have enough peace and quiet in the present sort of climate to do what I did in 1964.”

But having no time to think is not exclusive to the academy, even though the irony there is quite thick. This development is attached to a much larger phenomenon – the quickening of social time. Professional and personal life is simply moving faster and faster. Businesses have always competed to do things better, as in, quicker. Employers and managers expect minute-to-minute attention through smart phones, even on weekends and vacations. Domestic life also feels this pull, as both parents and children feel increasingly overwhelmed by ever-refined schedules which accommodate ever-expanding activities.

In the 1950s, the sociologist Pitrim Sorokin saw how modernity sped up social time, the pace of cultural change. Economic development, expanding communication, and technology cranked up the tempo of social life. And it just gets quicker with no slowing in sight. The Amazon Corporation wants to improve our lives by delivering products the same day that we order them – quicker must be more satisfying to the consumer. The Apple Corporation improved our lives with gadgets that insure we are always in earshot of the next email or text – constant contact must lead to better relationships. And to improve our lives even more, Jeb Bush, echoing overwhelmed managers around the country, warmly asserted that “we have to be a lot more productive, workforce participation has to rise from its all-time modern lows. It means that people need to work longer hours” – more work and more money must make for a better country! It all might make sense but we don’t really have time to think about it. I need to act, produce, lean in, and clean up.

But why are we doing this? What should we be doing instead? What is the purpose of life? These questions require time to think. But before I keep disparaging the lovely conveniences, wonderfully consumer-oriented corporations, and the speed of living in our post-modern age, I should ponder whether I really need time to think. Aren’t there some advantages to not thinking? Bliss, perhaps? Novelist Colum McCann notes the pitfalls of thinking too hard about our existence: “Just stand still for an instant and there it is, this fear, covering our faces and tongues. If we stopped to take account of it, we’d just fall into despair. But we can’t stop. We’ve got to keep going.” And that’s what Amazon, and Apple, and Jeb give us – something to keep us going. More stuff, more play, and more work, all without any troublesome insinuation to the meaning of it all.

Psychologist Ernest Becker asserted that “the idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else; it is a mainspring of human activity.” While in the past humans invented mythologies and religions to, as Hannah Arendt put it, create “a purpose that extends beyond the grave,” now we can avoid thinking about our grander purpose by endlessly pre-occupying our minds with schedules, emails, activities, and apps. Over 2000 years ago the philosopher Seneca could not foresee this glorious future but he did note the value of diversions. He advised that distractions, alternatingly serious and amusing, are the best way to keep one’s mind off the impermanence of it all. While the ancient Romans thought up some interesting diversions as they lolled around the Agora, modern Americans put them to shame. Our ability to buy new things, seek new entertainments, work longer hours, and just keep everything moving “forward” far exceed the relative sluggishness of Greek life.

This is the bright upside of constantly producing, consuming, and doing more and more; our relentless activity keeps us adeptly oblivious to the meaning of it all. We definitely feel stressed and overwhelmed, but isn’t that preferable to feeling despair and nihilism? In fact, the pace of post-modernity might have inadvertently solved the central human question – what is the meaning of life? Wittgenstein noted that “the solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of the problem.” That is what having no time can accomplish. Religious, philosophical, or moral guides to life are rendered obsolete because our schedules are already full. The purpose of life is simply getting to the next thing on your list. Case closed.

Featured Image Credit: Timepiece Perspective by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post No time to think appeared first on OUPblog.

What religion is Barack Obama?

On 7 January 2016, I asked Google, ‘what religion is Barack Obama?’ After considering the problem for .42 seconds, Google offered more than 34 million ‘results.’ The most obvious answer was at the top, accentuated by a rectangular border, with the large word ‘Muslim.’ Beneath that one word read the line, “Though Obama is a practicing Christian and he was chiefly raised by his mother and her Christian parents…” Thank you, Google.

Google is a treasure trove for religious historians. This search and the results alone could fuel days of conversation for my classes. What does it mean to ask an electronic aggregator to answer a question about individual values (belief) that cannot be physically discerned? How do we account for the complicated initial answer (Muslim … practicing Christian … her Christian parents)?

The Obama answer came from a Wikipedia page, a web hosting site that allows users to modify the contents. All in one, Wikipedia is democracy and anarchy, the best of information sharing and the worst. Whether you accept it as a source for citation or not, well, that’s up to you. In this case, we have the Obama religion wars in black and white print … err… in color on a screen.

I scrolled through some of the pages containing these Google ‘hits.’ There were articles from academics, newspaper reports, and blog rants. Many times, the same stories or snippets of information were ‘shared’ (is it plagiarism if it’s on the web?) It seemed that there were as many angles on this one topic – the religion of Obama – as there were voters in the elections he won.

Image credit: Screen shot of search “What religion is Barack Obama?”, courtesy of the author. Used with permission.

Image credit: Screen shot of search “What religion is Barack Obama?”, courtesy of the author. Used with permission.I’m as interested in the process by which humans search for and locate answers to our questions as the answers themselves. In the case of Obama’s religion, this process of seeking and finding may be as informative as the answers Obama gives himself,or the church or mosque or synagogue he attends, or what some pundit or academic has to say about him. The reality is, when most of us want to know something, whether it is about religion or anything else, we ask website aggregators. Years ago, ‘he’ may have been humorously named ‘Jeeves,’ but these web services play the role of priest, librarian, friend, and even god. When we want to ‘know’ something, we turn to the collective of human- and cyber-created information through search engines like Google.

When it comes to religion and politics, this new god of Google gives and gives and gives. This is particularly true for one topic that has run through my research during the past fifteen years: the question of “Was the United States established as a Christian nation?” Obama dealt with this explicitly in 2008 before he was elected president. Numerous historians have written brilliantly on the topic. But one text that has been largely neglected was a petition from African Americans in Massachusetts in 1777 for their freedom. In it, they described the land as a “Christian country.” Those searching for ‘Christian nation’ may not find the piece because of the slight (is it slight?) difference between ‘nation’ and ‘country.’ Thanks to Google (and some diligent librarians and archivists), we can locate not only transcriptions of the petition, but also scans of the original document.

But sources like this, as is the case with anything else placed and found on the World Wide Web, are not without their own set of problems to consider. First is how the documents are presented. One organization presents the petition as an example of American love for freedom and Christianity. Another sets it as an indication of white supremacy. Beyond such content framing, what would the materiality of the source tell us that we cannot see or feel on the computer monitor? Was the paper perfumed or scented at any point? Does capitalization (or lack thereof) matter? Were or are there any other pieces of data or information surrounding the page that have been removed? How heavy or fine was the paper?

All of these seemingly little things may matter, just as our ability to find more than 30 million results to the question of Barack Obama’s faith. One dilemma of the Information Age is how to deal with all of the information we have. Another is to deal with what information we think we have, when in fact we may not.

So when it comes to the religion of Obama, neither I, nor Google, nor any of us will ever ‘know.’ As to whether the United States was, is, or will be a ‘Christian nation’ (or ‘country’) is another question we cannot ‘know.’ But that’s the beauty of religion and perhaps the Internet itself: the point isn’t always to know. It’s to believe.

Featured image credit: President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama attend a church service at Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., on Inauguration Day, Sunday, Jan. 20, 2013 by Pete Souza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What religion is Barack Obama? appeared first on OUPblog.

Grove Music announces its third Spoof Article Contest

It’s that time of year again! We invite you to submit your entry for Grove Music’s Spoof Article Contest, and as usual the winning entry will be announced on April Fool’s Day.

Spoof articles have been part of Grove’s history for several decades; it seems that our authors have always had an inclination toward humor. The most recent winning entry (“Henderson, Lucas John”) was written by Joanna Wyld, and it was published on the OUPblog alongside the other top entries.

If you think you have what it takes to fool the Grove editors, here are the rules.

Submission Guidelines:

Articles must be no longer than 300 words, including any bibliography or works lists you might choose to include. There is no minimum length. Entries that do not adhere to the length limit will be folded, spindled, and rejected.

Articles will be judged by a mix of staff and outside judges including Grove Music’s Editor in Chief Deane Root, Editor Anna-Lise Santella, and a guest to be named later.

Judges will consider the following criteria:

Does the article adhere to Grove style?

Is it entertaining?

Could it pass for a genuine Grove article (maybe if you forgot your glasses and you were squinting at it)?

Submissions must be sent by email sent to editor[at]grovemusic.com as follows:

Subject must read “Grove Music fake article contest-[title]” (e.g., Grove Music fake article contest-Ear flute).

Body of the email must include the title of the article and your full name and contact information (street address, email, phone)

The article must be included in an attached document. It must not include your name. This is to facilitate blind judging. Use your article’s title as the document name (if your article includes punctuation that can’t be in a document title, replace the punctuation with a space). You may send as many as three articles, but please send each submission separately. No more than three entries will be accepted from a single author.

All submissions must be received by midnight on 29 February 2016. Manuscripts received after that time will not be considered.

The winning article(s) will be announced on 1 April 2016 on the OUPblog.

The winner will receive $100 in OUP books and a year’s subscription to Grove Music Online. The winning entry will be published on the OUPblog and also at Oxford Music Online where they will appear NOT as part of the dictionary, but alongside the historic spoof articles on a special page.

Fine print: We reserve the right not to award a prize if we feel the submissions do not meet our criteria. All submissions become the property of Oxford University Press. Additional terms may apply.

Headline image credit: Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

The post Grove Music announces its third Spoof Article Contest appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford Law Vox: Loukas Mistelis on international arbitration

In our twelfth episode of the Oxford Law Vox podcast series, international arbitration expert Loukas Mistelis talks to George Miller about current arbitration issues. Together they discuss how the international arbitration landscape has developed, how arbitration theory has attempted to catch up with practice, and ask whether the golden age of arbitration is now passed.

Below are selected excerpts from their wide-ranging discussion, and you can also listen to and download the full podcast via Oxford Law Vox on SoundCloud. Amongst the many aspects of international arbitration discussed in their conversation, Loukas and George take a look at the key issue of enforceability and relationships with existing jurisdictions.

“I think what attracted parties to arbitration originally was that arbitral awards were faster than national court decisions. That continues to be the case. Although I have argued that perhaps we are in the post-golden era of arbitration, where the first 50 years of the New York convention from 1958 to 2008 were the golden years, the fact remains that the United States does not have a single treaty with any other country for their completion of judgements. And the same is true for Japan to a large extent. So outside the European Union the movement of judgements is an issue which is quite challenging to parties who have prevailed in a case but still have to enforce them, therefore they still have to have some court procedures in another jurisdiction. Arbitration has resolved this issue, and has resolved it in quite a successful way. Of course the enforcement of awards where the parties do not voluntarily comply has to be done through the courts. But this is fairly limited – typically in about 10% of the cases that there will be some sort of court action.”

Loukas also reflects on the changes that can be seen as arbitrations become more costly and more complex, and whether this is leading parties to consider alternate dispute resolution in a way that perhaps they were less inclined to ten years ago:

“I think arbitration has become a victim of its success. It became, and still is, the natural choice for cross-border disputes. But at some point parties started feeling that their interests were not best served by the arbitration process. Too much money goes to the lawyers, quite a bit of money goes to the arbitrators and arbitration institutions, and it takes quite some time. I think the average duration of an arbitration would perhaps be anywhere between 15 and 18 months. That is much quicker than many national legal systems, but is slower than other legal systems, like for example Japan or Germany or perhaps the United States. In this country you could go through all these systems in three years – sometimes you can only go through a single arbitration in three years … the problem is simply that mediation, or alternate dispute resolution, is not suitable for all cases.”

Before the conversation turns to the final topic of the Oxford International Arbitration Series, Loukas addresses the question of whether the often confidential nature of proceedings and awards contributes or hinders the practice of business:

“Most international commercial cases … will go to arbitration. So the majority of lawyers would not be able to be privy to the development of commercial law as it develops for arbitration. Now the traditional arbitral defensive answer to that was that arbitration is a result of the dispute between the two parties, so they do not think in the bigger context of making laws for future generations. But collectively they do. And there this becomes the duty not of the arbitrators, perhaps not of the parties, but the duty of the arbitration institutions to make sure that they communicate to the bigger audience what the decisions are about. For example the International Chamber of Commerce has been by producing sanitised extracts of awards in particular topics … It doesn’t give the answers for everything but certainly we have more awards published in some form now than quite a few years ago. I think that’s started to change effectively with the ICCA Yearbook … but for sure the expectation is that there will be more and more publication of awards from this time forward.”

To hear the full interview with Loukas Mistelis, and to listen to more podcasts from a range of law experts, check out Oxford Law Vox on SoundCloud.

Feature image credit: The Night Lights of Planet Earth, by woodleywonderwork. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Oxford Law Vox: Loukas Mistelis on international arbitration appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers