Oxford University Press's Blog, page 554

February 2, 2016

The Cancer Moonshot

Can you imagine seeing the face of your unborn child at age 18?

Things are moving quickly in the field of genomics.

The first article of this column described the coming Practical Genomics Revolution as evidenced by the creation of 11 genomic medicine centres under the auspices of the 100,000 Genomes projects led by Genomics England.

Now, the initial results are in.

More than 6,000 genomes have been analysed and the project will receive another £250 million in funding in 2016. The project is releasing the first genomes back to participants and with them come diagnoses for two little girls with rare genetic diseases. In total there are an estimated 6,000 rare genetic diseases already described and more awaiting discovery.

Jessica was diagnosed with a known genetic disease, GLUT1 Deficiency Syndrome, which can now be helped through a special diet that will hopefully increase the energy to her brain and halt her epileptic seizures. “More than anything the outcome of the project has taken the uncertainty out of life for us,” said her mother.

When Georgia’s genome was compared to those of each of her parents, a novel mutation was found in a single gene. It could only be inferred at this point, that it causes her poor eyesight, weakened kidneys, dyspraxia and physical and mental developmental delays.

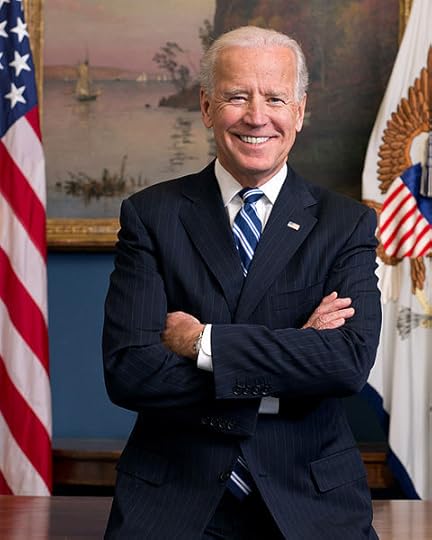

US Vice President Joe Biden. Official portrait via the United States Government. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

US Vice President Joe Biden. Official portrait via the United States Government. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Genomics England has just recruited the first cancer patients. Each contributor will have tumour and healthy cells genome sequenced for comparison. Participants include three sisters all diagnosed with breast cancer within 15 months. Their DNA is of particular interest because they lack mutations in the BRCA genes usually associated with heritable breast cancer.

The 100,000 Genomes Project in England was accompanied by the announcement of the Million Genomes Project in the US, which this year, has been sistered with the vastly larger ‘Cancer Moonshot‘ initiative.

Announced on 13 January by President Obama in his eighth and final State of the Union Address, the multi-billion dollar project will be led by US Vice President, Joe Biden, who has a vested interest in seeing new cures for cancer. His son, Beau, recently died of brain cancer at the age of 46 and Biden’s mission is deeply personal. Biden is encouraging people to come forward and tell their stories.

In Davos, Biden held a panel discussion and called on the international community to double the pace of cancer breakthroughs and end cancer as we know it.

Promising avenues of research and application include the development of vaccines, genetic circuits that modify the physiology of cells, nanotechnology delivery units that directly kill tumors without damaging the rest of the body, and gene-editing.

The panel discussion focused heavily on big data and the need to unify existing stores of data. There are already billion-dollar plus efforts underway to prevent and cure cancer, including the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s cancer ‘moon shots’ cancer program and the International Cancer Genome Consortium.

Biden acknowledges that there are many issues to tackle, including privacy, data sharing and the question of “should a person own their own genome.”

He strongly encouraged the breaking up of data silos and the open sharing of data. Genomes are actually the easiest part to digitize the panel agreed, it remains the phenotypic information that is more complex and needs much more work.

Computer algorithms that can transform raw DNA into portraits promise to provide new challenges to the concept of genomic privacy. Using information from genes for eye and hair color and ethnic background, it is possible to generate 3D faces.

While the technology is new and researchers, are finding that DNA for facial features is incredibly diverse, it takes genome sequencing one more step away from anonymous. Craig Venter even says he can determine what your voice sounds like, along with generating a 3D profile of your face.

Since it is possible to sequence the genome of fetal cells circulating in mother’s blood, he even goes so far as to say he can predict what the faces of unborn children will look like at age 18.

The Practical Genomics Revolution promises to roll on in 2016.

Using genomics to cure cancer is being held on par with JFK’s desire in 1961 to land men on the moon.

Featured image credit: Barack Obama, by mikebrice. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The Cancer Moonshot appeared first on OUPblog.

February 1, 2016

Deferring the Cadillac tax kills it

Sometimes it is gratifying to have predicted the future. Sometimes it is not. The recent postponement of the so-called “Cadillac tax” until 2020 falls into the latter category. I predicted this kind of outcome when the Cadillac tax was first enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, popularly known as “Obamacare.” I am unhappy that events have now proven this prediction correct. As a political matter, the deferral of the Cadillac tax effectively kills it.

Many serious commentators on the American healthcare system criticize the Internal Revenue Code’s treatment of employer-provided medical care premiums. Employer-paid premiums are excluded from employees’ gross incomes for tax purposes. This exclusion results in higher medical costs since employees are sheltered from the1 consequences of their employers’ greater health care outlays. Employees thus lack the incentive to help their employers control medical costs.

If employer-provided health care premiums were instead included in employees’ gross incomes, employees and employers would be forced to make hard decisions to control those premiums. By sparing employees the pain of reporting as income the medical insurance costs their employers pay for them, the Internal Revenue Code hampers the unpleasant but necessary task of confronting these costs.

The Cadillac tax is a modest effort to control healthcare outlays by penalizing expensive “Cadillac” health plans. Embodied in the now-postponed Section 4980I of the Internal Revenue Code, the Cadillac tax would tax employer-provided medical coverage costing annually more than $10,200 for an individual or more than $27,500 for a family. The tax of Section 4980I would be 40% of the excess over these thresholds. Thus, for example, if an employer-sponsored health plan pays $11,000 annually for individual coverage, a tax of $320 would be due, i.e., ($11,000 – $10,200) x 40%. The drafters of Section 4980I intended that the prospect of this Cadillac tax would encourage employers and employees to control medical costs to avoid this penalty tax.

The Cadillac tax is a decidedly modest reform compared to the real solution for the underlying problem—namely, making all health insurance premiums taxable income to the employees covered by such premiums. Nevertheless, the tax was an initial step in the right direction. The Cadillac tax would have begun the process of curbing the Internal Revenue Code’s subsidy of high medical insurance costs.

In the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2016, Congress and President Obama have now attenuated even this modest measure. They agreed that the Cadillac tax, previously scheduled to take effect on 1 January 2018, will now be delayed until 1 January 2020. As a political matter, this delay effectively kills the Cadillac tax.

Right after the adoption of the Cadillac tax, I predicted that Congress would not allow this levy to go into effect. The Obamacare statute, passed in 2010, originally scheduled the Cadillac tax to take effect eight years later in 2018. Thus, from the beginning, the tax was perceived to be politically toxic. Hence, the Congress and President Obama initially delayed the tax’s effective date into the future.

At the time, I predicted that, as we got closer to 2018, the political calculus would remain the same and that future Congresses and Presidents would be unwilling to actually impose the Cadillac tax—just as President Obama and the Congress that passed the Affordable Care Act were unwilling to implement the tax in a timely manner.

Events have now, unfortunately, proven this prediction to be correct. Republicans and Democrats alike were unwilling to enter the 2016 campaign season with the enforcement of the Cadillac tax on the political horizon. Republicans oppose the Cadillac tax because it is a tax. Democrats oppose the Cadillac tax because many of the most expensive healthcare plans are union-negotiated arrangements.

Some advocates of this recent delay argue that, before 2020, the Cadillac tax will be replaced by something better. I am skeptical. If Congress had been willing to adopt an alternative to Code Section 4980I, it could have done so now. Delaying the Cadillac tax to 2020 instead sets the tax on course for repeal.

Healthcare costs cannot be controlled until they are confronted. The Cadillac tax was a modest step in that direction. The delay of the Cadillac tax reflects an unfortunate reality: On a bipartisan basis, our elected officials denounce high healthcare costs but are in practice unwilling to take the painful steps necessary to actually control such costs.

Image Credit: “Leader Pelosi” by Nancy Pelosi. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Deferring the Cadillac tax kills it appeared first on OUPblog.

Sectarian tensions at home

The execution of the popular Shi’a cleric Nimr al-Nimr by Saudi authorities at the beginning of this year has further intensified Sunni-Shi’a sectarian tensions not just in Saudi Arabia but the Middle East generally. The carrying out of the sentence, following convictions for a range of amorphous political charges, immediately provoked anti‑Saudi demonstrations among Shi’a communities throughout the Middle East. More locally, it added to the grievances of the sizable Shi’a minority in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province.

Al-Nimr was known for his vocal criticism of both the Saudi ruling family and the country’s Sunni religious establishment. The extent of his strident anti‑government views positioned him in contrast to other Shi’a leaders such as Hassan al-Saffar, who at various times have participated in cross-sectarian conciliation efforts involving the Saudi government. Al-Nimr’s radical discourse from time to time placed him on the periphery of the country’s Shi’a leadership. But the inability of more conciliatory Shi’a clerics to secure genuine social and political change for the Shi’a population, as well as the constant anti-Shi’a sentiment fueled by government-aligned Sunni clerics, had in the years before his death provided space for the re-emergence of his rejectionist ideals.

In 2009, an incident in Medina, which saw clashes between security forces and Shi’a pilgrims from the Eastern Province, triggered a new wave of restiveness among the Shi’a population. The state sided with the security forces and blamed the pilgrims for the clashes. Disillusioned with the lack of support for their community, many Shi’a began to question their status in the kingdom. Among them was al-Nimr, who outlined demands for religious freedoms for the Shi’a. This increased his popularity among Shi’a adherents.

During the Arab uprisings that commenced in 2011, which included further protests in the Eastern Province, al-Nimr became a symbol for Shi’a resistance, especially among Shi’a activists. Protests would often feature placards and banners depicting al-Nimr.

“Mosquée Masjid el Haram à la Mecque” by Citizen 59. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Mosquée Masjid el Haram à la Mecque” by Citizen 59. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.It was al-Nimr’s speeches during this time that led to his 2012 arrest and ultimate execution. He criticised Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Bahrain in 2011 on behalf of the Sunni royal family there. He also made provocative and essentially celebratory remarks upon the June 2012 death of Crown Prince Nayef. It was the latter incident that immediately prefaced his arrest.

Many of Saudi Arabia’s influential Sunni clerics were outraged by al-Nimr. Those clerics tend to preach a doctrine of obedience to rulers; al-Nimr’s speech after the death of Nayef was thus intolerable. This intolerance was clearly also felt within the Saudi government, notoriously sensitive to criticism and ready to suppress dissent.

It was not surprising, therefore, that al-Nimr’s execution, along with those of 46 others including radical Sunni militants, was endorsed by a number of high‑profile Saudi clerics. Among them was the Grand Mufti, Abd al-‘Aziz Al al-Shaykh, who decreed that the government had acted in accordance with Islamic law. To the government’s supporters, and particularly among the Sunni clerical establishment, al-Nimr was an extremist who was in substance little different from the violent Sunni terrorists who had also been executed.

There are some Sunni clerics in Saudi Arabia, such as the prominent Salman al-Awdah, who do not participate in hostile anti‑Shi’a rhetoric and who have at times supported conciliatory efforts with Shi’a leaders such as al-Saffar. But even for these Sunni moderates (for want of a better word), al-Nimr was too radical.

Al-Nimr’s execution is yet another deterioration in the already fragile sectarian environment in Saudi Arabia. The situation in the Eastern Province was getting worse even before al-Nimr met his end. In November 2014, during a Shi’a religious celebration in the Eastern Province, an attack by Sunni militants killed five people. This was followed by two suicide attacks on Shi’a mosques, a week apart, in May 2015. Although the government and its religious establishment pledged solidarity with the Kingdom’s Shi’a in the wake of these attacks—and there is little doubt that the Saudi government is genuinely concerned by Sunni militancy—some Shi’a questioned the government’s sincerity.

Others, including the Shi’a activist and historian Hamzah al-Hassan, blamed the attacks on anti-Shi’a rhetoric propagated by Sunni polemicists, which was on the increase at the time to galvanize support for Saudi Arabia’s decision to intervene in Yemen to fight the Shi’a Houthis there. It cannot be denied that anti-Shi’a sentiment remains prevalent in the rhetoric of the kingdom’s clerical establishment. That rhetoric has increased in order to support Saudi Arabia’s sectarian-flavoured and anti-Iranian approaches to the conflicts in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. This rhetoric sees Saudi Shi’a tainted by their religious association with other Shi’a in the region, especially Iran. Ultimately, it is likely that all al‑Nimr’s execution will do is make it difficult for Shi’a leaders such as al-Saffar to convince sections of the Saudi Shi’a population that peaceful change emanating from the Saudi royal family is a viable option.

Featured image: Photo by GLady. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Sectarian tensions at home appeared first on OUPblog.

The mercy of the Enlightenment

Pope Francis recently announced a ‘Year of Mercy.’ He called on all Catholics to once again realize that God is love and that this includes infinite mercy. Yet, the message of mercy, also with its practical consequences, has been constant on the agenda of the Catholic Church, even in the eighteenth century—a time which is allegedly known for its rigid, sectarian close-mindedness. Here are four ways that the Catholic Church has emphasized ‘mercy’ over time.

Embracing an inclusive position of mercy

One of the big questions for theologians of the eighteenth century was “Who can be saved?” and whether God’s grace and mercy extended to those not Catholic or not even baptized. Many embraced an inclusivist position of mercy, such as this Austrian Catholic: “A Christian has the… duty to think, believe and act as Christian—to live and die as a Christian since God has put him out of gratuitous grace in circumstances in which he can have a better knowledge of God and his nature, … in order to become worthy of a higher happiness… From this, however, it does not follow that non-Christians will be damned, only that it is also their duty to become Christians once they have gained a sufficiently convincing knowledge of Christianity.” Even the most famous theologian of the day, Nicholas Bergier (1718–1790), stated that God’s mercy was infinite and included all people of good will, and consequently the possibility of salvation for all, albeit always through the grace of Christ.

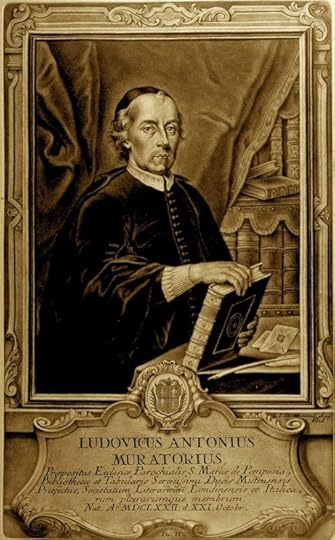

Image credit: Ludovicus Antonius Muratorius by Skara kommun. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Ludovicus Antonius Muratorius by Skara kommun. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Emphasizing the centrality of Christ’s love

Emphasizing the centrality of Christ’s love was yet another tenet of the time’s theology. Similar to evangelical thinkers, the Italian Ludovico Muratori (1672–1750) reminded his fellow Catholics: “Jesus Christ is… the grand foundation of all hopes of Christians… whose own merits move the mercy of his divine father to grant us, truly penitent, the forgiveness of our sins.”

Helping the marginalized

The Church also proved to be more merciful towards the marginalized; it provided more help for people—such as women who had become pregnant out of wedlock, orphans, the sick, and especially the poor—than many self-righteous Enlighteners. They certainly wanted to end poverty, but by the most inhuman means; workhouses and prisons were designed to keep beggars from the street, as only productive people were considered ‘valuable’ citizens. In contrast, Bishop Jacques Bossuet spoke of the “eminent dignity of the poor.” Since the world had abandoned the poor, God would take up their defense, and because people scorn them, God would “raise up their dignity.” The poor were, for Bossuet, the most genuine citizens of the Church, because Christ addressed them the most directly. Because Christ emphasized the poor so frequently, Bossuet was convinced that only through them and the sacraments did heavenly grace flow on earth. Society was not called to just help them out of pity but to have “great sentiments of respect” for them as they are the “firstborn” of the church. The Church valued the poor in principle, gave alms and set up institutions for their betterment, but ultimately did not wholeheartedly commit to reform unjust social structures.

Baptizing deformed babies

A final example of the practice of mercy is that of baptism to deformed babies. In the 1770s and 1780s, there was a discussion about whether deformed, short-lived babies who did not look “fully human” should be baptized. Of course, one was not yet aware of the different stages of embryonic development, but as usual, reason won the argument, put forth by the Catholic layman and professor of medicine, Franz X. Mezler. He made clear that a human mother can only give birth to another human—regardless of the looks of that human. “The sacraments are there for humans, not humans for the sacrament—this is a principle of reason and of Christian charity. It would be loveless heartlessness to expose such a questionable creature [as the unhumanlike baby] to the danger of losing its eternal bliss and to kill its body and soul.”

If we take a close look at the ideas of Enlightenment Catholicism, we can see how many contemporary reforms are inspired by them. Pope Francis follows in more than one way in the footsteps of Catholic Enlightenment.

Featured image credit: church altar mass religion by Skitterphoto. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The mercy of the Enlightenment appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten facts about snack foods from around the world

Did you know that in the United States, February is National Snack Food month? In 1989 a need was seen to increase the sales of snack food in the usually slow month of February, and so National Snack Food month was born.

But is snacking good for us? Eating and mealtimes are (inherently) the result of physiological needs. It takes about four hours after eating for the glucose levels in our brains to dwindle, at which point the brain starts to use glycogen, which is stored in body tissues and reprocessed by the liver. That’s when our appetite kicks in, telling us to start eating again.

In times and places when food supplies might be unreliable, it is better for us to eat one or two big meals a day. This is because these will increase the fatty deposits in our bodies, and so improve our chances of survival (as you don’t know when your next meal will come). However, where the food supply is certain our bodies can much better survive on fewer, smaller, but more regular meals. Therefore, the modern trend of snacking frequently throughout the day is seen as “nutritionally rational”.

Like anything, though, it depends on what snack food you are eating to determine how healthy this really is! We’ve collected together 10 surprising facts about snack foods from around the world, all taken from The Oxford Companion to Food.

‘Elevenses’ is a colloquial expression which entered the English language in the late 18th century, meaning a light refreshment taken at about 11 o’clock in the morning. In the Mediterranean this is called merenda (or merienda), in various German-speaking regions it’s called the zweite Frühstück (second breakfast), and in Chile there are salas de onces.

The pretzel, a snack food often found on American sidewalks, has arguably gathered more culinary mythology about its origins than any other foodstuff: from praying hands in a 7th-century Italian monastery, to a Frankish king in Alsace, to rewards for children learning their catechism.

‘Inside of pacay fruit’ by J Bradley Snyder. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr

‘Inside of pacay fruit’ by J Bradley Snyder. CC BY-ND 2.0 via FlickrLupin seeds are bitter and toxic when fresh, but they can be soaked in salted water or boiled to make them edible. Toasted and salted seeds are served as a snack food, or appetizer, today.

Okari nuts, which taste like an almond, principally grow in Papua New Guinea, can be as large as a tennis ball, and look like mini cabbages.

Pacay pods have been popular since the times of the Incas, and are still eaten as a snack among rural populations in the Andes today. They are sometimes called an ‘ice-cream bean’ because the pulp is sweet, perfumed, and white, just like ice cream.

A common snack food in Sulawesi (an Indonesian island) is nutmeg fruit. This is peeled and split into two, with the mace and nutmeg removed, leaving the fruit halves. These are then spread out, sprinkled with palm sugar, and left for three or four days in the sun until translucent, pale brown, and slightly fermented. This is called manisan pala or pala manis.

Pakora are batter-fried vegetables or fish which are usually eaten as an appetizer or snack in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. They are also known as bhajis or bhajias.

The Indian version of a samosa is the best known of an entire family of stuffed pastries or dumplings popular as a snack food from Egypt and Zanzibar to Central Asia and Western China.

A very popular street food in Canada is poutine, described by Cynthia Wine as ‘an amazing concoction of French fries, cheese and gravy’. This is not to be confused with another type of poutine – the name used in Provence for both the sardine and the anchovy in their larval state.

Popcorn as a snack has been around for a while. Archaeologists in New Mexico uncovered corn cobs and kernels, including some (dating from early in the 1st millennium BC) that were popped. Some of these ancient unpopped kernels, placed in hot oil, proved still capable of popping!

Featured image credit: ‘Rouga snack food’, by junierwong. CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay .

The post Ten facts about snack foods from around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

January 31, 2016

Wrapping up the AALS Annual Meeting 2016

The Association of American Law Schools (AALS) is a nonprofit association of 179 law schools. The association serves as the learned society for over 9,000 law faculty at its member schools, and provides them with extensive professional development opportunities, including the AALS Annual Meeting which draws thousands of professors, deans and administrators each year.

The 2016 AALS Annual Meeting took place from 6-10 January, at the New York Hilton Midtown. This year’s conference theme was From Challenge to Innovation: American Legal Education in 2016, and the program included 200 sessions, 800 moderators, speakers, and discussion leaders, seven new types of program sessions and events, not to mention 50 networking events.

This year’s outstanding array of speakers included:

A special welcome from Michael R. Bloomberg, Former Mayor of New York City and Founder, Bloomberg L.P. & Bloomberg Philanthropies

The Honorable Justice Stephen Breyer, the Supreme Court of the United States

Paulette Brown, ABA President

The Honorable Robert A. Katzmann, US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and author of Judging Statutes

Blake D. Morant, AALS President and Dean, The George Washington University Law School

Deborah L. Rhode, Director of the Center on the Legal Profession, Director of the Program in Law and Social Entrepreneurship (Stanford), and author of The Trouble with Lawyers and Lawyers as Leaders

One of the most memorable parts of the conference was getting to catch up with so many of our fantastic authors! Below is a photo slideshow of the authors that visited our booth.

Symeon Symeonides with Blake Ratcliff

Blake Ratcliff, Acquisitions Editor alongside Symeon Symeonides, author of Codifying Choice of Law Around the World: An International Comparative Analysis.

Ross Guberman with Jo Wojtkowski

Jo Wojtkowski, Marketing Manager alongside Ross Guberman, author of Point Made: How to Write Like the Nation’s Top Advocates and Point Taken: How to Write Like the World’s Best Judges.

Philip Meyer

Philip Meyer, author of Storytelling for Lawyers.

Neil H. Cogan

Neil H. Cogan, author of The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins.

Robert Katzmann

Robert Katzmann, author of Judging Statutes.

Dennis Patterson

Dennis Patterson, author of Minds, Brains, and Law: The Conceptual Foundations of Law and Neuroscience.

James Fleming

James Fleming, author of Fidelity to Our Imperfect Constitution:

For Moral Readings and Against Originalisms.

Jonathan Todres

Jonathan Todres, author of Human Rights in Children’s Literature:

Imagination and the Narrative of Law.

Ronald J. Krotoszynski, Jr.

Ronald J. Krotoszynski, Jr., author of Privacy Revisited: A Global Perspective on the Right to Be Left Alone.

And remember that we are still offering a 20% off discount for all our titles on display at the conference until 9 March 2016.

Image Credit: “Law” by Woody Hibbard. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Wrapping up the AALS Annual Meeting 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

When probability is not enough

While out driving one afternoon, I notice a bus speeding down the road towards me. As it approaches, the bus drifts into my lane, forcing me to swerve and strike a parked car. The bus doesn’t stop and, while I glimpse some corporate logo on the side, I’m shaken and I don’t manage to make it out. Later, when I’ve recovered myself, I do some investigating and find out that of all the buses operating in the area on the day in question, 90% were owned by one company – the ‘Blue-Bus’ company – with the other 10% owned by rival companies. Should I take the Blue-Bus company to court and demand compensation for the damage caused? If you were presiding over the case, would you make them pay? When people were presented with cases like this in a series of psychological studies, the majority thought that the company should not be held liable just because they happened to own the majority of buses in the area. And judges and lawyers seem to agree – this example is based upon a real, unsuccessful, lawsuit.

But there is something curious about this. After all, my evidence against the Blue-Bus company seems very strong – it makes it 90% probable that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus. Why isn’t that enough? Surely we don’t have to be 100% certain before we make the Blue-Bus company pay up – we’re rarely 100% certain of anything. Also, it seems that we would be willing to hold the company liable on the strength of other kinds of uncertain evidence.

Suppose I don’t find any general information about the buses in the area, but I do find another witness to the incident who tells me that the bus was a Blue-Bus bus. Under current legal practice, the Blue-Bus company could well be found liable on the basis of testimony like this. But witnesses don’t always speak the truth – it’s still not certain it was a Blue-Bus bus. The witness might have been hallucinating, or might have a false memory, or could just be making up a story to smear the company. The testimony undoubtedly makes it probable that it was a Blue-Bus bus that forced me to swerve but, plausibly, it doesn’t make quite as probable as 90%. Eyewitnesses are not that reliable. Viewed in one way, the situation seems very puzzling. We’re happy for the Blue-Bus company to be found liable on the basis of the testimonial evidence, but not on the basis of the statistical evidence, even though the statistical evidence makes it more likely that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus.

Though it has been widely discussed in legal theory, this puzzle isn’t just a legal one – it goes deeper. Suppose you’re not involved in any legal proceedings against the Blue-Bus company, but you’re just trying to figure out for yourself what happened. If your only evidence is that 90% of the buses operating in the area were Blue-Bus buses then you shouldn’t believe that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus – that would be jumping to conclusions. And yet, if a witness says that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus, then you would be justified in believing this. So much of what we believe is based on taking others at their word. But how could I be more justified in believing that the bus was a Blue-Bus bus on the basis of testimony, when the statistical evidence makes this more likely to be true?

But how could I be more justified in believing that the bus was a Blue-Bus bus on the basis of testimony, when the statistical evidence makes this more likely to be true?

One possibility is that our instincts about this example, and others like it, are just wrong. Maybe we should believe that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus on the basis of the statistical evidence, and we’re being irrational if we refuse to believe this. And maybe the Blue-Bus company should be found liable on the strength of this evidence too, and our legal practices need to be reformed.

Then again, maybe our instincts about the example are absolutely right – and they only seem puzzling because we’re trying to understand them within a probabilistic framework. Thinking in terms of probabilities is very natural and useful, but is it the only way to look at a piece of evidence? Here is something different to consider: If a witness tells me that the bus involved was a Blue-Bus bus, and it wasn’t, then there has to be some explanation as to how this came about. Some possible explanations have been mentioned above – maybe the witness suffered a hallucination or a false memory or was lying etc. Whatever the case, there has to be more to the story – it can’t ‘just so happen’ that the bus wasn’t a Blue-Bus bus, even though the witness said that it was. But it could ‘just so happen’ that the bus wasn’t a Blue-Bus bus even though 90% of the buses operating in the area were Blue-Bus buses. While this would in a way be surprising, given the proportions involved, no special explanation would be needed.

If you believe that the bus was a Blue-Bus bus, based on testimony then, while your belief is not guaranteed to be true, something is guaranteed: if your belief is false, then this must be due to some interfering factor. This is a feature of the testimonial evidence that has nothing to do with probabilities – and it’s not shared by the statistical evidence. If you believe that the bus was a Blue-Bus bus based on the fact that 90% of the buses in the area were Blue-Bus buses then this could turn out to be simply false, and there’s nothing more to it – you took a gamble and you lost.

Is this what makes it OK to believe things on the basis of testimonial, but not statistical, evidence? Is this what makes it reasonable to find companies liable on the basis of testimonial but not statistical evidence? Maybe, maybe not. But, at the very least, it shows us that probabilities are not the whole story when it comes to understanding our evidence.

Featured image credit: Photo by Dave Gough. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post When probability is not enough appeared first on OUPblog.

January 30, 2016

The Zika virus: a “virgin soil” epidemic

With news that the Zika virus is “spreading explosively” throughout the Americas, much of the medical community, including the World Health Organization, remains on high alert. Below, Peter C. Doherty, author of Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know, discusses the nature, characteristics, and scope of the Zika virus.

First isolated in Uganda in 1947, this normally mild, non-fatal mosquito-born flavivirus infection is characterized by transient fever, joint pain, and malaise. The current explosive Zika virus epidemic in the Americas is, however, causing great concern because of what looks to be a sudden, dramatic increase in the incidence of microcephaly (small brain/head size) in newborns. Flaviviruses are not known to cause this type of problem and the Zika link is yet to be definitively established, but indications are that the fetus is at greatest risk in the first trimester when, following a bite from a carrier Aedes spp mosquito, virus crosses the placenta to cause brain damage at this vulnerable stage of development. Early, high level viremia (virus in blood) may also explain the one known case of venereal transmission when an American traveller returning from Africa had unprotected sex with his wife. Clinically normal at the time, he soon developed symptoms, while she became ill some time later.

It’s generally thought that vertebrate hosts—in this case humans and some monkeys—have to circulate a lot of virus to infect a biting mosquito. In a healthy adult human, the developing adaptive or specific immune response will normally control the infection within seven to 14 days of initial exposure. Then, at least with other flaviviruses like West Nile virus, live Yellow Fever virus vaccine, the continued presence of neutralizing antibodies in the blood will protect in the very long term. One flavivirus, the hepatitis C virus, does cause continuing viremia, but this is a unique pathogen and, apart from some limited evidence of low level persistence for the related tick-borne encephalitis viruses, the general view is that this class of infections is completely cleared from the human body.

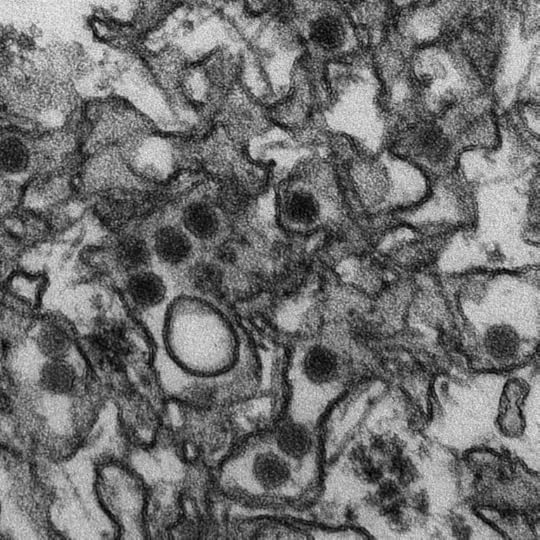

“Transmission electron micrograph of the Zika virus” by CDC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Transmission electron micrograph of the Zika virus” by CDC. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.What we are seeing in the Americas is a classic “virgin soil” epidemic. Enormous numbers of people and mosquitoes are being infected, the virus is transmitting at a very high level, and there may be as many as 4×106 cases. Apart from affected neonates, all will likely recover, with increasing “background” immunity progressively limiting the number of new infections in subsequent years. The current molecular technology is such that making a protective vaccine should be technically straightforward, but the process of safety testing and evaluation could take several years.

All cases so far in the United States, Europe, and Australia have been in travelers returning from infected areas. Though the related West Nile virus (WNV) is now endemic in North America, the difference is that Zika virus—like Yellow Fever virus—is maintained in a mosquito/primate life cycle, while WNV is primarily an infection of birds, especially corvids (crows, magpies) which it kills in large numbers. WNV can, at times, also kill us.

In the meantime, though Zika infection may spread north, any impact in the United States is likely to be limited by mosquito control measures that are particularly well established in Southern communities. The big risk will be at times of extreme summer rainfall when spraying insecticide may be less effective. But, unlike the situation for WNV, we will not see outbreaks associated with drought, as occurred recently in Texas, where birds and mosquitoes come together at scarce water sources.

The long-term prospect with Zika virus is that we will live reasonably comfortably with it, especially if there is a vaccine to protect women of reproductive age. The principal decision for responsible authorities, like National Governments in endemic areas and the WHO, is whether there is a case for fast-tracking, then funding, a vaccine to protect all young women. For the present, pregnant women are advised not to travel to these countries and, for those where this in not an issue, insect repellant also offers some protection against much nastier viruses like dengue and Chikungunya.

Image Credit: “Equipe de combate ao mosquito Aedes aegypti vai ao Lago Sul” by Agência Brasília. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Zika virus: a “virgin soil” epidemic appeared first on OUPblog.

5 facts about marriage, love, and sex in Shakespeare’s England

Considering the many love affairs, sexual liaisons, and marriages that occur in Shakespeare’s plays, how many of them accurately represent their real-life counterparts? Genuine romantic entanglements certainly don’t work out as cleanly as the ending of Twelfth Night, where Sebastian and Olivia, Duke Orsino and Viola, and Toby and Maria all wind up as married couples. However, Shakespeare’s imaginary theatrical arrangements frequently collided with significant thoughts and beliefs of 16th-century England, such as a woman’s duty as a wife and the social standing of “bastard” children.

In the late 16th century, the legal age for marriage in Stratford was only 14 years for men and 12 years for women. Usually, men would be married between the ages of 20 and 30 years old. Alternatively, women were married at an average of 24 years old, while the preferred ages were either 17 or 21.

Of Shakespeare’s eligible female characters who refuse marriage and husbands, not one of them remains single. Katherine, Beatrice, Olivia, Isabella, and Emilia all resist becoming wives, yet they all end up married by the end of their respective plays (although Isabella’s silence to the Duke’s proposal is open to interpretation).

The marriage ceremonies in Shakespeare’s plays are invariably offstage affairs. Given the London authorities’ annoyance with the perceived blasphemies conducted in theatres, staging any religious ceremony in a public playhouse would have been an invitation for trouble.

Many of Shakespeare’s plays include plots that centered on male jealousy. Examine the triangle involving Ford, Mrs. Ford, and Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor, or the conflict between Menelaus, Paris, and Helen in Troilus and Cressida. Other plays that hinge of male jealousy include Much Ado About Nothing, Othello, Cymbeline, and The Winter’s Tale.

Roughly 2-4% of children born between 1590 and 1640 in England were illegitimate, meaning they were born out of wedlock or were “bastards.” Shakespeare incorporates many bastards into his works, such as the Bastard of Orleans (1 Henry VI), Philip the Bastard (King John), Don John (Much Ado About Nothing), Thersites and Margareton (Troilus and Cressida), and Edmund (King Lear).

Featured Image: Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses by “H.E.” (1569). Hampton Court Palace, The Royal Collection, United Kingdom. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post 5 facts about marriage, love, and sex in Shakespeare’s England appeared first on OUPblog.

January 29, 2016

The evolution of breathing tests

If a person is experiencing difficulty breathing comfortably, the chances are that the difficulty stays with them no matter what they’re doing, be it sitting, standing, or walking. So it’s not surprising that conventional scans or breathing tests, carried out with the patient lying on a couch or sitting in a chair, don’t always tell us what the problem is. With an exercise test (cardiopulmonary exercise test to give it its full title, often abbreviated to CPEX or CPET) measurements are made as the patient gradually gets up to full tilt on an exercise bike or treadmill. Questions are being asked of the body. How much can it do? If there’s anything wrong, it should be easier to see when the patient is being physically pushed.

Image: Metabolic cart from COSMED by Cosmed. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Metabolic cart from COSMED by Cosmed. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.‘How much can the body do?’ could also be re-phrased as ‘how much oxygen is the body getting?’ Your body needs to get oxygen into the lungs, across into the blood, then around the body to the muscles that require it. If you can’t get any more oxygen in, then you have to switch from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, meaning your muscles are operating without oxygen. Anaerobic exercise is maintainable for a short sprint, but you may know from experience that you won’t be able to sustain this pace for very long.

Oxygen uptake is usually called VO2, with ‘V’ being the volume of oxygen. In the early days of exercise physiology, you had to collect all the air you breathed out in one minute into a large bag and then look at the oxygen content. Air contains 21% oxygen, so if you know the volume of air breathed in a minute and how much oxygen there is left in the expired air, you can work out how much has been taken up by the body. As technology has advanced and with the development of faster analysers, we can work out VO2 on a breath-by-breath basis and display the data in real time.

VO2 at the point you can’t exercise any longer is called VO2max. It is the single best indicator of your fitness, or indeed your health in general. The better your VO2max, the longer you’re likely to live and the more likely you are to survive an operation or general anaesthetic. During such tests heart rate and CO2 output are also recorded during exercise. Manipulating the data also allows us to look at how good your lungs are, how much blood your heart can pump with each beat, when you pass your anaerobic threshold, and much more. Such tests result in acres of numbers and graphs, and hopefully a diagnosis.

Featured image credit: Running Man by Kyle Cassidy. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of breathing tests appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers