Oxford University Press's Blog, page 550

February 11, 2016

Celebrating African American inventors

It’s been over 195 years since Thomas Jennings received a patent for a dry cleaning process, and black inventors have continued to change, innovate and enhance day-to-day life. This Black History Month, the team behind the Oxford African American Studies Center is excited to explore some of the many inventions dreamed up, brought to life, and patented by black inventors.

Thomas L. Jennings

Invention: Dry Cleaning Process

The first African American patent holder for an invention was Thomas L. Jennings. Born free in New York, Jennings was a well-known reformer who worked in the tailoring and dry cleaning trade, received his patent for a new dry cleaning process in 1821.

Alexander Ashbourne

Invention: Biscuit Cutter

Alexander Ashbourne of Oakland, California emphasized that his 1876 invention “relates to a novel domestic utensil, which I term a biscuit or cake cutter; and it consists of a molding-board, having hinged to one side or end a cover, which is provided with the desired shaped cutters upon its lower side.”

Jan Earnst Matzeliger

Invention: Automated Shoe Making Machine

Born in Paramaribo, Surinam (Dutch Guiana), Jan Earnst Matzeliger immigrated to the United States on the 1870’s. In 1883, Matzgeliger invented an automated shoemaking machine that quickly attached the top of the shoe to the sole. Although he remained active in the developing shoe-machinery technology Matzeliger’s financial benefit from the work was relatively modest.

Judy W. Reed

Invention: Dough Kneader and Roller

The first African American woman to receive a patent (No. 305,474), Washingtonian Judy W. Reed was completely illiterate, signing only “X” in place of a signature on her 1884 application. Reed created the “Dough Kneader and Roller,” a music box-like, crank-powered contraption that mixed and smoothed dough. The device was fairly complicated, employing multiple rollers of different shapes, metal strips, hinges, screws, and elastic.

Sarah Goode

Invention: Cabinet Bed

On 14 July 1885, Sarah Goode received her patent for a “Folding Cabinet Bed,” comparable to modern sofa or hideaway beds. The first of five black women to patent new inventions in the nineteenth century, she was a pioneer, and her efforts inspired other women and African Americans to pursue patents and take control over their creative contributions to American culture.

Sarah Boone

Invention: Ironing Board

Although little is known about her early life, at the time of her patent filing in 1891, Sarah Boone lived in New Haven, Connecticut. Boone’s patent application describes a complex design intended for a specific purpose. “My invention relates to an improvement in ironing‐boards, the object being to produce a cheap, simple, convenient, and highly effective device, particularly adapted to be used in ironing the sleeves and bodies of ladies’ garments,” she once said.

Garett Morgan

Invention: Gas Mask & Automatic Traffic Sign

Born Garrett Augustus Morgan on a farm in Claysville, Kentucky, Morgan was an astute inventor and a pragmatic businessman who dealt with racial prejudice by trying to work around it. At a later time, he probably would have gained greater renown. His life is a measure of how far an enterprising person could advance despite the color barrier, yet it also serves to illustrate how far American society would have to progress before race would be much less of a factor in the judgment of someone’s worth.

Marjorie Stewart Joyner

Invention: Permanent Waving Machine

In 1916, Marjorie Joyner became the first black graduate of the A.B. Molar Beauty School, later opening her own beauty shop in Chicago, at 5448 South State Street, where she served primarily white clientele. After enrolling in the Madame C.J. Walker Beauty School at the advice of her mother-in-law, Joyner became one of the company’s most trusted employees becoming vice president and chief instructor. Joyner’s invention, the mechanical device known as the Permanent Waving Machine, consisted of an electrically powered device with cords, metal curling irons, and clamping devices suspended from a dome, worked on the hair of both blacks and whites, and looked better and lasted longer than any other method available at the time.

Patricia Bath

Invention: Laserphaco Probe

Born in Harlem, Ophthalmologist Patricia Bath created the Laserphaco Probe, a tool which is used during eye surgery to correct cataracts, an eye condition that clouds vision and can lead to blindness. Since her first patent, Dr. Bath has improved on her original invention, patenting two updated versions including a laser apparatus for use during cataracts lenses surgery.

Lonnie G. Johnson

Invention: Super Soaker© Water Gun

Born and raised in Mobile, Alabama, inventor, entrepreneur, businessman, and nuclear engineer Lonnie Johnson, has received over 40 patents for multiple inventions including a hair drying curler apparatus and a smoke detecting timer controlled thermostat. A retired veteran on the US Air Force, Johnson’s most notable invention is the Super Soaker© water gun.

Image Credit: “Gears” by William Warby. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Celebrating African American inventors appeared first on OUPblog.

Whose chat-up line is it anyway?

Along with death and trees, love is probably the most commonly explored theme in literature. So many of our favorite maxims and aphorisms about love are drawn from classical fiction. But how well do we really know these quotes or the novels and poems from which they derive? When it comes to romance do you know your Shakespeare from your Shelley, your Byron from your Brontë? Test your knowledge of literary love quotes with this Valentine’s Day quiz from Oxford World’s Classics. Don’t be too confident, though. This one is a bit tough.

Image credit: Literature and Love, in the public domain via Pixabay.

The post Whose chat-up line is it anyway? appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of humans [infographic]

Where did we come from? How did we become human? What’s the origin of our species? It is hard to imagine our understanding of humanity without, of course, Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Writing in his iconic The Origin of Species, Darwin said:

“I think it inevitably follows, that as new species in the course of time are formed through natural selection, others will become rarer and rarer, and finally extinct.”

Our own family tree testifies to this age-old pattern of extinction, adaption, and evolution. The modern human, Homo sapiens is just one branch of the Homo genus, and our ancestors were as diverse as they were varied —from the grandparent of the Homo genus, Australopithecus afraensis, to Homo habilis (who managed to tame fire) and the famous Neanderthal, which, as scientists and archaeologists are beginning to uncover, were a far more complex and developed species than we first imagined.

To celebrate his birthday and Darwin Day, the University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) team has read through the hundreds of academic works available to delve into the history of humanity. View our infographic below and find out for yourself how we became human.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPEG.

Do you want to discover more about the evolution of humans? Read the chapters we used to create this graphic, now available for a limited time: ‘Henri’s Cave: On Our Origin‘ from How Life Began, ‘Adapted Individuals, Adapted Environments‘ from The Evolved Apprentice, ‘The Origins and Evolution of Homo sapiens‘ from Evolution and Religious Creation Myths, ‘Who Were the Neanderthals?‘ from Darwinian Detectives, and ‘Thinking from an evolutionary perspective‘ from How Homo Became Sapiens.

Featured image credit: Hands at the Cuevas de las Manos upon Río Pinturas by Mariano. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The evolution of humans [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten facts about the cornet

Sometimes mistaken for the trumpet, a near relation, the cornet has had a fascinating and diverse history. Popular from military and jazz bands to the 19th century European stage, the cornet has had a home in the American music scene for generations of musicians and music styles.

The “cornett”, a wooden wind instrument with a cup-shaped mouthpiece, appeared in the late 15th century and remained popular for about 200 years, even remaining in use through the end of the 19th To differentiate from the cornet, F. W. Galpin insisted on continuing to spell cornett with the extra “T”.

At four and a half feet long, the cornet is a more compact and shorter instrument than its cousin, the trumpet.

When the cornet was invented, nobody bothered to take a patent out on it. It can be traced to Jean-Louis Antoine, however, and was in use throughout Paris by the 1820s. By 1830s, horn player Dufresne performed solos on the cornet at regular gigs.

In addition to Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke and King Oliver were the best-known cornet players of the 20th century.

Variations on the cornet began to appear in the late 19th century, such as the “butterfly model”, “circular cornet”, and “echo cornet”.

During the Civil War, military band players often played with the cornet over their shoulders, bells facing backwards.

Until the radio became mainstream around World War I, town bands were the most common form of local musical entertainment in the United States. They often featured the cornet, some of them even called “silver cornet bands”. John Herald, an American cornet-maker, provided many of these instruments at the turn of the century, and his cornets are still known as some of the finest ever made.

After the decline of town bands, cornets found their vogue in African American musical groups and a new emerging style: jazz. Louis Armstrong famously switched from the cornet to the trumpet in the 1920s, possibly due to a recording environment that favored the latter instrument.

In the Victorian era, cornets usually had deep, funnel-shaped mouthpieces, called the “shepherd’s crook style”; after the Second World War, mouthpieces gradually shrunk and became much more shallow, and thereby more similar to the trumpet. A more recent wave of “nostalgia” has entailed a revival of the Victorian mouthpiece.

Although the popular French cornets of the 18th century pitched from C or B♭ down to D, or up to E♭, American cornets have since shifted pitches to E♭, C, and B♭.

The above are only ten facts from the extensive entry in Grove Music Online. Did we leave out any fun facts about the cornet?

Featured image: Cornet Patent Drawing from 1901. Photo by Patents Wall Art. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ten facts about the cornet appeared first on OUPblog.

Illusions for survival and reproduction

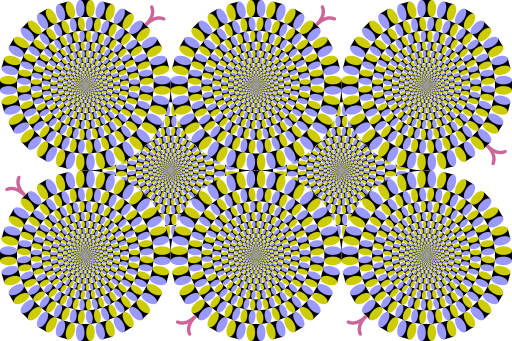

Much of what we think we see is not real – it’s an illusion. A favourite pastime for many visual psychologists and artists is to baffle and confuse our perception by making things appear that are not really there, or manipulating the way that we might see patterns or colours. The origin of many illusions lies in the fact that the brain often receives incomplete or conflicting information from the visual system and has to ‘fill in’ or rectify the missing information. Most of the time it gets it right, but sometimes, especially with artificially constructed scenes, it can be misled. We know that a vast range of illusions trick human perception, but what about other animals? Researchers are now beginning to shed light on whether non-human animals see visual illusions, and whether they might even use them in nature to deceive and exploit others.

The first reason why animals may utilise illusions is for defence against predators. Back in the 1970s a series of studies on snakes suggested that particular stripes and zig-zag markings created the impression that a snake was either moving at a different speed, or even in the opposite direction to reality. Something about the banding patterns and colours seemed to fool observers into misjudging speed. It is perhaps not surprising then that a now famous visual illusion by Kitaoka Akiyoshi, the ‘rotating snakes illusion’, is broadly based on the idea of contrasting bands of colour. These create the very strong impression of movement where none truly exists.

‘Rotating Snakes peripheral drift illusion, based on design by Kitaoka Akiyoshi’, by Cmglee. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Rotating Snakes peripheral drift illusion, based on design by Kitaoka Akiyoshi’, by Cmglee. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This illusion has recently been shown to work on other animals too. A recent study trained fish to discriminate between motionless or moving stimuli. When they were then shown an image of the rotating snakes illusion the fish categorised the stimulus as moving. Rather more observational video evidence shows that kittens are also fooled by this illusion.

So what might all this mean for animals in the wild? Many species of snake, fish, some insects, and of course zebra have prominent stripes and banding patterns. Perhaps these help them to avoid being captured by predators? A few years ago, along with several colleagues including Graeme Ruxton at the University of St Andrew’s, I tested whether humans’ ability to capture moving objects would be affected by the patterns that the targets had. We gave subjects the chance to play a computer touch screen game, whereby they tried to capture erratically moving rectangular ‘prey’ against a range of visual backgrounds. The findings were not completely clear-cut, but we consistently found that striped and zig-zaged targets were caught less and missed more than objects with other patterns, like spots and blotches. Most recently, Martin How from Bristol University and Johannes Zanker from Royal Holloway University made a computer model based on how animal vision might encode motion. They then ran through the model shifting images of zebra and unpatterned horses, and found that the model responded with much higher levels of erroneous motion when presented with the zebra. These and other strands of evidence suggest that striped patterns in nature may at least sometimes confuse and ‘dazzle’ predators into misjudging speed and direction, allowing the prey to escape, in much the same way as some dazzle painted warships in WWI.

A male great bowerbird (Ptilinorhynchus nuchalis) standing in front of his bower. Bottom: the grey and white decorations of the bowerbird, arranged according to a size gradient, with small objects closer to the bower structure. Photograph by Laura Kelley. Do not use without permission.

A male great bowerbird (Ptilinorhynchus nuchalis) standing in front of his bower. Bottom: the grey and white decorations of the bowerbird, arranged according to a size gradient, with small objects closer to the bower structure. Photograph by Laura Kelley. Do not use without permission.Obtaining protection is just one possible use of illusions. Another is to manipulate potential mating partners. The colour patterns of many animals play an important role in mate choice, often with females choosing to mate with brighter or more gaudy individuals. However, perception of colour is affected by many factors, including light conditions and even the colour of any adjacent colours, among other things (remember the debate over ‘The Dress’ last year?).

As we might expect, some animals use this phenomenon to their own advantage. Recently, a study on guppy fish (the brightly coloured tropical species often kept as a pet) showed that males preferred to associate with rival males that a female would not be strongly attracted to. In doing so, he may make his own appearance look better (more colourful), and improve his own mating chances. Males also manipulate female perception of size and distance. Work in the last few years at Deakin University by Laura Kelley and John Endler has shown that bowerbirds can manipulate female choices through creating illusions. Bowerbirds, found in New Guinea and Australia are famous for males building elaborate bower structures often decorated with gaudy objects. Females inspect the male’s bower and decide whether to mate with him or not. In the great bowerbird (Ptilinorhynchus nuchalis) males build a tall bower of sticks with an ‘avenue’ running through it. Females stand at one end and watch as a male waves colourful objects at her from the other end. He does this against a backdrop of plain grey objects (stones, bones, and other things; which presumably enhances the colour of his displays).

Importantly, the male arranges the objects in size order and creates something called a ‘forced perspective illusion’. If the male simply scattered different sized objects on the ground randomly then those pebbles further away would on average look smaller. In a forced perspective illusion, the male creates a gradient of increasing object size with distance, which creates the impression of a uniform arrangement of object sizes and may make the male look larger. Kelley and Endler showed that males who create better illusions are likely to be fitter males, and in turn, they are more likely to successfully mate

Overall, illusions come in many forms work in a range of complex ways. At present, only a handful of studies have started to ask whether they exist in nature and why. We are only just scratching the surface of a method by which animals may exploit, trick, and manipulate others.

Featured image credit: Zebra pattern, by Martin Stevens. Do not use this image without permission.

The post Illusions for survival and reproduction appeared first on OUPblog.

February 10, 2016

Between language and folklore: “To hang out the broom”

We know even less about the origin of idioms than about the origin of individual words. This is natural: words have tangible components: roots, suffixes, consonants, vowels, and so forth, while idioms spring from customs, rites, and general experience. Yet both are apt to travel from land to land and be borrowed. Who was the first to suggest that beating (or flogging) a willing horse is a silly occupation, and who countered it with the idea that beating a dead horse is equally stupid? We will probably never find “the author,” even if we catch the earliest citation in print or dispose of such idioms as so-called familiar quotations (a great wit may have coined one or both of those sayings or used the phrases already current and thus made them famous). Who in the past kicked the bucket and when? Who sowed wild oats, and why just oats? Occasionally I discuss such matters. Raining cats and dogs, pay through the nose, no room to swing a cat, whip the cat, and a few more have turned up in this blog.

While dealing with the numerous phrases containing the word Dutch, I ran into the expression to hang out the broom (what Dutch has to do with this phrase will become clear later). In England, a broom was sometimes hung out of the window to signify a family quarrel. However, one wonders whether the idiom to hang out the broom “to have fun while the master is away; to announce being cuckolded by the wife, etc.” goes back to this custom and even whether it exists in Modern English. At one time, it certainly did (borrowed from Dutch?) but was not widespread. Similar questions have been asked and occasionally answered about many sayings. For instance, in bird hunts, some people’s work is to beat about the bush. The birds fly from the bush, so that the rest of the company can catch them. With time, this practice was understood as a sign of evading the real work and prevarication, the birds were forgotten, and all that is left is the idiom, despite the fact that the time-honored practice has survived.

The same holds for hanging out the broom. For comparison: when we say that we succeeded in cutting the mustard (once mentioned in passing in this blog), we are aware of only the ultimate meaning of the phrase rather than of its origin, as also happens when we use separate words (for example, cut, the, and mustard). Whether to hang out the broom exists as an idiom depends on whether anyone still uses it as such, forgetting about the broom (compare show the white feather, throw the gauntlet, throw in the towel, and the like). Below I will only say what I have read about the practice of hanging out the broom, so that, if the antiquated idiom again comes to life, our readers will have an idea of how it might have originated.

Van Tromp, a famous Dutch admiral, who was fond of broom symbolism.

Van Tromp, a famous Dutch admiral, who was fond of broom symbolism.A correspondent to Notes and Queries wrote in June 1850:

“This custom exists in the west of England, but is oftener talked of than practised. It is jocularly understood to indicate that the deserted inmate is in want of a companion, and is ready to receive the visits of his friends. Can it be in any way analogous to the custom of hoisting a broom at the mast-head of a vessel which is to be disposed?”

At the moment I am especially interested in the question asked at the end of the note. Half a year later, the custom was described in more precise terms: it was, we are told, “applicable to all ships and vessels for sale or hire, by the broom (an old one being generally used) being attached to the mast-head.” Those letters were followed by a report, according to which the custom originated from the period of English history when the Dutch admiral Van Tromp (he was actually Tromp, not Van Tromp) appeared with his fleet on the English coast. This takes to 1652 or 1653. The rest is a popular legend whose authenticity is dubious. Tromp allegedly hoisted a broom as indicative of his intention to sweep the ships of England from the sea. In answer to this insolence, the undaunted and eventually victorious English admiral hoisted a horsewhip.

Even if such an exchange occurred under the circumstances described, it does not explain why a broom attached to a mast signifies that the ship is for sale or for hire. According to a rather plausible theory, it had been customary since very old days for servants who looked for employment to wear a hat with a piece of broom on it (broom here means “bramble”; the two words are related). The navy supposedly took over this custom, so that, although the horsewhip is indeed the distinguishing mark of English ships of war and can be traced to the engagement with the Dutch, it fails to account for the practice of announcing that the ship is for sale. In any case, the civil use of the phrase, in at least one situation, may go back to its use at sea (“for sale” or “for hire”). In 1895 an author characterized hanging out the broom as a well-known (!) cant (!) phrase to express the husband’s unwonted enjoyment and hospitality to his friends during his wife’s absence. We note that, although the idiom was understood as low slang (“cant”), it referred to an outwardly innocent pastime (a man is a temporary bachelor and would like to spend some time with his companions while his wife is away). He is not “for hire” (or “sale”) as far as other women are concerned. But the Dutch say zij [she] steekt den bezem uit “she hangs out the broom [besom],” and that means “she wants a new husband.”

This is a besom, and that is a broom.

This is a besom, and that is a broom.Sidney O. Addy, a distinguished folklorist, whose books are interesting to read but whose reconstruction of myths should be taken with a sizable grain of salt, wrote as early as 1895 that, if in the neighborhood of Sheffield (South Yorkshire) a girl strides over a broom handle, she is said to give birth to a child out of wedlock. Addy continued: “Now it is evident that we have here an instance of sympathetic magic, the broom representing the phallus. This being the case, the object of the husband in hanging out a broom in his wife’s absence was to give notice that he could be happy with another whilst his lawful charmer was away.” I won’t discuss how “evident” this conclusion is, but I notice that, according to one version, it is the woman who displays the (phallic?) broom, while according to the other, it is the man. And, returning to the naval metaphor, we observe that a vessel is for hire or sale when an asexual broom is attached to the mast. These pieces of information do not cohere too well; at least they don’t do so at first sight. As in the history of words, facts clash and confuse rather than elucidate the initial hypothesis.

I’ll finish with a short passage, dated 1896, on marital bliss and conjugal felicity:

“I have seen the broom hanging out many times in Derbyshire villages [the East Midlands, England]. But on these occasions the broom was always a besom—pronounced bey-som—the old sort made out of heather, the only rough brush [so not a real broom or a broomstick] known in those days, when I was a boy. To put out the beysom was the climax of a quarrel, and a sign of the utmost contempt on the part of the woman who did it. The beysom never came out except at the end of right royal word combats, and either out of window or reared outside the door was a defiance which sometimes lasted days long. […] I never knew the besom thus used in men’s disputes—only in those carried out by the women folk.”

Well, a ship is also a she, but this is probably beside the point. Other than that, who would say that the study of idioms is a quiet academic pursuit? It looks more like a tempestuous marriage.

Image credits: (1) Sharing their pleasures by Eugenio Zampighi. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp, 1597–1653, after an engraving by Jan Lievensz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Віник. Photo by teteria sonnna from Obukhiv, Ukraine. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Broom. (c) Antagain via iStock.

The post Between language and folklore: “To hang out the broom” appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is addiction treatment so slow to change?

The US taxpayers fund the overwhelming majority of addiction research in the world. Every year, Congress channels about $1 billion to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). An additional almost $0.5 billion is separately given to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), my own workplace for the past decade. That may sound impressive, and in many ways it is. With the help of these resources, there have been truly amazing advances in the understanding of how addiction works. “Brain reward systems” have become part of the general parlance. The NIDA director has become a celebrity who has appeared on 60 Minutes. New findings on how alcohol and drugs get people hooked have shown a rare ability to fascinate people far outside the circle of scientists. And there has been perhaps a more modest, but still significant progress in figuring out better treatments.

But the size of the addiction research enterprise is dwarfed by a $35 billion a year or so treatment industry in this field. This is a booming entrepreneurial world, where treatment centers charge people tens of thousands of dollars for various offerings. And despite all the investment in science, few of those treatments make much use of the scientific advances in the area of addiction. In fact, treatment approaches have not changed much at all over the past quarter century. If someone were to be pulled out of a 12-step meeting then and transported through time to one today, he or she would probably not notice much of a difference. Here is, perhaps unsurprisingly then, something that the investment in research has not bought us: Any measurable dent in the damage done by addictions.

Some basic facts: Alcohol continues to kill about 80,000 Americans each year. Death from prescription pain killers adds almost 20,000 more, and has been on the rise for over a decade. As we have begun clamping down on these prescriptions, heroin has become resurgent instead. Why is it that all the passionate research efforts by dedicated scientists have such a hard time producing much of a change in the lives of real people with addictions? Only about one in ten people with alcoholism ever receive treatment. For most of those, that is synonymous with joining Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), a movement formed three-quarters of a century ago, when medicine had little to offer addicts beyond perhaps treating the shakes of acute alcohol withdrawal.

Why is it that all the passionate research efforts by dedicated scientists have such a hard time producing much of a change in the lives of real people with addictions?

As I wrote in an op-ed in the Washington Post almost two years ago, we now know that the effects of behavioral treatments for alcoholism are modest at best. The favored therapy in the US, 12-step treatment, fares even less well in scientific evaluations. A rigorous analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration, the original source of the evidence based medicine concept, found that “available . . . studies did not demonstrate the effectiveness of AA or other 12-step approaches in reducing alcohol use and achieving abstinence compared with other treatments.” In fact, AA’s own surveys have indicated that for every 100 alcoholics entering their first meeting, only about 30 will be attending and sober a year later. That is very close to the spontaneous relapse rates consistently found by research over the past four decades.

Addiction, in its more severe forms, is simply very hard to treat. On a good day, AA-groups still offer a lot that is simply priceless for people who otherwise have little: A community, a context, and the support of others. But given how hard addiction is to treat, one would think the arrival of science-based addiction medications would be greeted with great enthusiasm. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Let’s for a moment forget the Lasker-award winning advance, methadone maintenance for heroin addiction, or its younger cousin buprenorphine. These, after all, would require us to discuss the trade-off between lives saved, and the provision of medications that are addictive themselves, a worthy topic for another day. But the FDA determined already in 1994 that naltrexone (Revia) is an effective treatment for alcoholism. And naltrexone is completely non-addictive, safe, well-tolerated and cheap. It is by no means a panacea, but reduces the risk of heavy drinking by about 20%, even more in the right patient. Yet fewer than 10% of patients with alcoholism receive a prescription for naltrexone or, for that matter, any alcoholism medication. Medications that target brain function simply continue to be viewed unfavorably in most 12-step programs. Because of this, patients lose out on the benefits of treatment. Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry gets a clear message to stay away from investing in alcoholism therapies. What then, one might ask, is the point of devoting so much research to addictive disorders?

To change this, some of us doing the science will have to get out of the lab and try to get a public conversation going. If not before, this was clear to me some seven years ago, when I saw a broadcast of Larry King Live. This was years after the FDA had determined that naltrexone is beneficial in treating alcoholism. That did not prevent Susan Ford Bales, then-chair of the Betty Ford Center, from bluntly dismissing it. “We do not use [these medications] at the Betty Ford Center,” she pronounced, as if that fact was its own justification. There is no other area of medicine where disregarding easily available evidence would be tolerated.

Equally problematic, as recently pointed out in a beautiful piece in The Atlantic by Gabrielle Glaser, is the uncompromising AA tenet that “once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.” Its implication that abstinence is the only worthwhile treatment outcome continues to feed catastrophic thinking and a sense of being powerless when people slip, instead of promoting self-efficacy, learning, and harm-reduction. Sure – many alcoholics remain highly susceptible to relapse for life. Abstinence is always the safest bet. But many patients are not ready to pursue abstinence. Attempting to impose on them a treatment goal they are not ready for goes against reports from solid behavioral research, and turns people away from treatment.

As I wrote in my Washington Post piece: The system is broken. It must be fixed before too many more people die. The first step toward fixing it is trying to bring together what science has taught us about addiction over the past quarter century with the everyday experiences of people with addictions, their families, and their treatment providers.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Columbia University Press blog.

Featured image credit: ‘Wine and hard liquor bottles photographed through a multiprism filter’ by Kotivalo. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why is addiction treatment so slow to change? appeared first on OUPblog.

Marriage equality in Australia: will 2016 bring a change in the law?

A series of landmark events in 2015 sustained prevalent interest in the campaign for marriage equality. In May, Ireland became the first country to legalise same-sex marriage via a referendum. Shortly after this, the US legalised same-sex marriage with a momentous Supreme Court ruling – widely proclaimed as the biggest victory for gay rights activists to date.

Elsewhere, 2016 will see the campaign for marriage equality continue with renewed determination – perhaps nowhere more so than in Australia.

Hopes for change on the issue in Australia were raised and quickly dashed following September’s leadership spill in the centre-right Liberal Party, in which Malcom Turnbull defeated Prime Minister Tony Abbott, 54 votes to 44. Once seen by advocates of law reform as a champion of marriage equality, the new Prime Minister stated his intention to maintain the coalition’s position on the issue. Liberal MPs would not be allowed a ‘conscience vote’, rather the issue would be put to the Australian people through a plebiscite. The move was considered by several Australian Labor Party MPs – including the Party Leader Bill Shorten who has introduced legislation on the issue – to be a delaying tactic. By contrast, Labor MPs will maintain a conscience vote for the next two terms of government (until 2019), when they will be bound to vote in favour of law reform. Shorten also made a commitment to legalise same sex-marriage within his first 100 days, if elected prime minister.

These developments have brought one question to the fore amongst those following the debate in Australia: Where now for same-sex marriage under Turnbull? Coinciding with the Liberal leadership challenge, although largely overshadowed by those events, a Senate committee released its report on a crossbench bill for a plebiscite on the issue. Unexpectedly, it rejected the idea. The report, authored by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee and chaired by independent Queensland Senator Glenn Lazarus (a co-sponsor of the bill), found holding a referendum or plebiscite on the issue unnecessary, as a public vote is not required to change the law. The report also found that a vote would involve unnecessary expense (the cost to the taxpayer could run up to $158 million) and could potentially cause harm to vulnerable groups by providing a platform for homophobic views. The Liberal Party continues to advocate the use of a plebiscite to resolve the issue. However, as George Williams argues, Turnbull may be saved by the fact that Senate support is required to allow the public vote, and opposition there might prevent him from having to implement a policy that ‘he knows is a step in the wrong direction’.

The Committee recommended that a same-sex marriage bill be ‘introduced into the Parliament as a matter of urgency, with all parliamentarians being allowed a conscience vote’. To this end, groups such as Australian Marriage Equality (AME) are focused on ‘securing the numbers’ if a bill were to be put to a conscience vote. This is a vital tactic, as evidence suggests that the support of ‘unwhipped’ small ‘l’ Liberal MPs could be pivotal. In New Zealand, the support of 26 MPs (44% of the Party) from the centre-right National Party, alongside 31 Labour and 20 MPs from other parties, at the Second Reading stage was key to reaching the majority of 61 required to pass the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Act 2013. Similarly, in the UK the votes of 126 Conservative MPs (48% of those that voted) at Second Reading significantly contributed to the majority of 326 needed to change the law in the House of Commons. The position of Liberal MPs remains to be tested in an ‘unwhipped’ vote in the Australian Parliament, but several of the Party’s MPs aligned towards the centre have demonstrated their willingness to take a progressive position on other issues attracting a conscience vote.

At the close of 2015, AME announced that their campaign had gained the support of 71 MPs in the House of Representatives – just five short of the majority required. With 21 MPs (14% of the House) ‘undecided’ 2016 will be a busy year and the campaign to secure their votes will undoubtedly continue. The group believes it already has a majority of support for reform in the Senate.

The result of a conscience vote on marriage equality in the Australian Parliament during 2016 might still be too close to predict. What seems certain is that, with polls demonstrating record levels of support amongst Australians, pressure on politicians to change the law will continue to mount.

Headline image credit: Rally for Marriage Equality – Brisbane – November 2013 by Nimal Skandhakumar CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

The post Marriage equality in Australia: will 2016 bring a change in the law? appeared first on OUPblog.

“The experience of chocolate craving”- an extract from The Economics of Chocolate

The following is excerpted from The Economics of Chocolate which provides an economic analysis, as well as an interdisciplinary overview on all things chocolate. We are constantly being told that chocolate is bad for our health– but is it bad for our mind? This extract details on the benefits of chocolate consumption and the impact chocolate cravings have on our moods.

It is indisputable that chocolate consumption gives instant pleasure and comfort, especially during episodes of ‘emotional eating’, which involves searching for food (generally in large amounts) even if not physiologically hungry in order to get relief from a negative mood or bad feelings (e.g. stressful life situations, anxiety, depression).

The pleasure experienced in eating chocolate can be, first of all, due to neurophysiological components. Chocolate is high in branch-chain amino acids, and especially in tryptophan, which increases the blood level of serotonin, the neurotransmitter which produces calming and pleasurable feelings. The increase in plasma serotonin concentration has been observed especially in white chocolateeating people, probably because of the higher content of carbohydrates in this type of chocolate rather than dark chocolate. Moreover, the presence of magnesium improves the body’s ability to adapt to stress.

But the pleasure experienced in eating chocolate cannot be justified solely by neurophysiological components. Chocolate can be desired because it provides a unique sensory experience. It has a hedonistic appeal to most people, based on sight, preparation, memories of past chocolate experiences, texture, and taste. Therefore, we should not underestimate the idea that chocolate consumption assumes a positive value because it is primarily linked to memories of childhood, maternal instinct, affection, moments of celebration, and emotional contexts, such as festive situations and family gatherings. In fact, there is a reciprocal relationship between mood and food: food can influence the mood of an individual and, conversely, specific emotional states can lead to the choice of a particular food. So it is no wonder if, on some occasions, we consider ‘chocolate cheaper than therapy, with the appointment not necessary’ (Molinari and Callus 2012).

Parker and colleagues (2006) indicate that chocolate is one of the most craved foods. The experience of ‘craving’ can be defined as an intense desire for a particular item. Chocolate craving was reported also by Wurtman and Wurtman (1989) to have an interesting impact on brain neurotransmitters, with antidepressant benefits, and has been used as a form of self-medication in atypical depression and in seasonal affective disorder.

Image credit: Chocolate Heart Cookies by Bianca Moraes. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Chocolate Heart Cookies by Bianca Moraes. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.Nearly three thousand individuals who had experienced clinical depression were interviewed about food cravings when depressed. Of the whole sample, 45 per cent reported craving chocolate when depressed, especially among females, with the following related explanations: its pleasure-enhancing role; its capacity to improve depression and to decrease irritation and anxiety; its unique taste; its ‘feeling in the mouth’; its texture; its smell; and finally its colour (Parker and Crawford 2007). A specific association between cravings for sweets in general and, more specifically, for chocolate products during the menstrual period has been found. Women eat more and seem to have very strong cravings for chocolate just prior to and during their menstrual cycle, when feelings of tension or depression occur. This is when progesterone levels are low and pre-menstrual symptoms tend to appear as well. It has been demonstrated that there is a physiological and hormonal basis for this kind of craving (i.e. a pre-menstrual desire for chocolate) (Tomelleri and Grunewald 1987). Chocolate may provide an antidepressant effect during this critical period and also when women enter menopause, when, in fact, they often develop a sudden strong craving for chocolate.

Rozin and colleagues (1991) believed that chocolate contains pharmacologically active substances responsible for the craving. However, it is still not clear whether the secret of the ‘chocolate craving’ can be only attributed to a pharmacological effect or whether sensory properties are more important with regard to the psychological aspects of this food. It is still unknown whether these substances are present in sufficient amounts to play a major role in chocolate consumption or to cause physiological addiction. Smit (2011) thought that some publications have only fed myths about chocolate craving.

Weingarten and Elston (1991) reported that, while the craving for carbohydrates can be satisfied from any fatty or sweet food, including chocolate, the majority of the chocolate cravers cannot replace chocolate with any other food in times of strong desire. This is why it is very important not to deprive someone completely of chocolate if he/she desires it. Doing it could lead to the opposite effect: the subject, not having the opportunity to eat chocolate at will, will overconsume it as soon as it becomes available (Polivy et al. 2005). This confirms the fact that chocolate is a unique food which inspires unusually strong desires in people. It is therefore important to distinguish the phenomena of ‘pure’ chocolate craving from the one of ‘general’ carbohydrate craving in the context of emotional eating. It is probable that each phenomenon is driven by different motivations and so produces different outcomes.

A neologism referring to a perceived physical or psychological addiction to chocolate and/or its chemical composition has been devised: ‘chocoholic’ combining the word ‘chocolate’ with the word ‘alcoholic’ (Wilson and Hurst 2012). Chocoholics tend to be female rather than male because they are more susceptible to the effects of the two compounds phenylethylamine and serotonin, which can be mildly addictive (Salonia et al. 2006).

However, since depriving one of chocolate fails to produce scientifically relevant withdrawal symptoms, chocolate is not technically classed as a physically addictive substance.

Featured image credit: chocolate lindt box by GlenisAymara. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post “The experience of chocolate craving”- an extract from The Economics of Chocolate appeared first on OUPblog.

Which mythological creature are you? [Quiz]

Classical mythology has been prominent in popular culture for thousands of years. For every God or Goddess there would be a mythological creature — or several in the case of Hercules — that they would have to overcome in order to display their prowess, power, and divinity. This was particularly the case in Ancient Greek mythology. Today, we’re looking at the less fashionable side of this partnership and focussing our attention on the creatures that mortals feared and heroes vanquished.

Does your gaze turn others to stone? Do you prefer ignorance or vengeance? Have any wings? Take this short quiz to find out which mythological creature or being you would have been in the ancient world.

Featured image credit: Mythical Creatures, by Friedrich Johann Justin Bertuch (1747-1822). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz background image credit: Hydra. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Which mythological creature are you? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers