Oxford University Press's Blog, page 549

February 14, 2016

Shakespeare and sex

Shakespeare made many gifts to the English language, but his most memorable gift in the particularly rich and rarefied area of euphemisms for sexual intercourse comes in the opening scene of Othello, when Iago strives to provoke Desdemona’s father Brabantio to outrage with the news that “your daughter and the Moor are now making the beast with two backs.” Shakespeare seems to have borrowed the phrase from the French writer Francois Rabelais, who refers to “la bête à deux dos“. Thomas Urquhart memorably translated Rabelais’s account of the characters Grangousier and Gargamelle towards the end of the seventeenth century as “These two did oftentimes do the two-backed beast together, joyfully rubbing and frotting their bacon ‘gainst one another.” It is easy to see what drew Shakespeare, like Rabelais before him, to the fine mixture of the monstrous and the silly that this phrase contains. Though it has passed into common parlance, it is still prone to prompt a ripple of laughter or an outright snicker from a modern audience.

One of the remarkable features of Shakespeare’s work, however, is his ability simultaneously to provoke a response, and a response to the response; we both laugh, and scrutinize ourselves laughing, particularly when it comes to sex, or the language of sex. Euphemism is a particularly powerful case in point. We titter at the mental image conjured up by Iago’s words because it hints at an uncomfortable truth: sex is awkward and ungainly, twisting those who engage in it into strange and contorted shapes. Laughing at Iago’s line in a theatre is at once a discomforting and a comforting experience. It is discomforting because each person who laughs confirms that she or he recognises exactly the strange activity to which he is referring, and has likely engaged in it, probably many times, and possibly plans to do so later that evening following a nice night out at the theatre. But it is comforting because laughing in the dark while facing the stage exorcizes the danger of such an admission, allowing each person tacitly to acknowledge the commonality of sexual activity, without doing anything as awkward as talking about it or even making eye contact.

Like anything that is truly interesting, but for a distinctive set of historical and cultural reasons, sex is both something that we cannot stop talking about, and something that is extremely difficult to talk about properly, to feel that we can (or should) adequately bring into language. There is a whole register of linguistic indirection – euphemism, bawdiness, obscenity – which emerges from this basic fact, and in which Shakespeare had an obvious interest. The proposition that we should read a playwright from four centuries past in order to think harder about sex and its role in human life and language is not obviously compelling, but there are various reasons to consider doing so. One reason, though rightly the least respectable, would be because Shakespeare’s works give us insight into his own sexual orientation or proclivities, the most elusive aspect of an all-round elusive biography. Stephen Booth gave this prospect short shrift when he wrote that “William Shakespeare was almost certainly homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual. The sonnets provide no evidence on the matter.” Even Booth’s brusque dismissal assumed that these categories are theoretically applicable to Shakespeare, and a second reason for considering sex in his works would be in part to question this assumption, to use them as a basis for historicising the very categories through which we understand sex, and stress the inescapably historically specific dimensions of this biological necessity. And a third reason, effectively a version of the old claim for Shakespeare’s timelessness, would be to assert that he grasped something essential and unchanging about human sexuality and sexual behaviour, and can therefore help us understand our own, very different time.

Desdemona Cursed by her Father by Eugène Delacroix. Brooklyn Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Desdemona Cursed by her Father by Eugène Delacroix. Brooklyn Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsNone of these options seem satisfactory to me, nor have they satisfied the many scholars who have written very well on the topic in recent years. I began with euphemism and the responses that it provokes in the theatre because Shakespeare seems persistently interested in sex as a route into the realm of the unsaid and the knowing, the entire world of unspoken assumptions and silent rituals that serve as the glue for social interaction of all sorts – including, but not defined by, sexual interaction. Precisely because these assumptions are tacit, they are both immensely important, and fraught with danger.

This is one way of understanding Shakespeare’s recurrent concern with jealousy, which returns us to Othello. Iago’s opening euphemism is actually unusual in its directness, for his favourite technique involves convincing his auditors that gestures of courtesy and esteem in fact bespeak deeper desires and lusts. Describing Desdemona’s treatment of Cassio to Roderigo, he asks “Didst thou not see her paddle with the palm of his hand? Didst not mark that?” Roderigo replies “Yes, that I did; but that was but courtesy,” but Iago waves this away: “Lechery, by this hand; an index and obscure prologue to the history of lust and foul thoughts.” The meaning of the paddling of palms depends not only upon Iago’s commentary, but on how it has been played in this particular performance; it is a powerful and chilling moment precisely because Shakespeare insists that there can be no absolutely clear line drawn between the sexual and the rest of human life, or between sexual and non-sexual actions. Paddling a person’s palm might no longer be an accepted gesture of courtesy, but it is easy to find modern equivalents: a handshake or a casual embrace can be entirely unthinking or formulaic, but if either of them is drawn out for a few seconds too long, or if a fleeting kiss on the cheek is too fervent or lands too close to the mouth, they can silently change into something quite different. This is difficult territory to navigate, precisely because is usually has to remain unspoken in order to function normally (if one comments on the quality of a particular kiss, hug or even a handshake, things get awkward quickly). The ambiguity created can be enjoyable for both parties – as with mutually pleasurable flirting – but it is open both to unfortunate misunderstanding and deliberate abuse, as in many cases of sexual harassment. Shakespeare’s own persistent interest lies as much in this fraught, unspoken realm of pleasure, risk, discomfort and danger, as in the sexual act itself.

In his other great treatment of jealousy, The Winter’s Tale, Leontes shrieks indignantly at his wife’s behaviour towards Polixenes, without even an Iago to prompt him: “Is whispering nothing? / Is leaning cheek to cheek? is meeting noses? / Kissing with inside lip?” These are the impossible questions towards which Shakespeare’s treatment of sex recurrently prompts us; he knew all too well that such tiny gestures could indeed be nothing, but, between certain people at certain times, they could very well be everything.

Featured image credit: Desdêmona by Rodolfo Amoedo. Museu Nacional de Belas Artes. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare and sex appeared first on OUPblog.

Fences and paradox

Imagine that you are an extremely talented, and extremely ambitious, shepherd, and an equally talented and equally ambitious carpenter. You decide that you want to explore what enclosures, or ‘fences‘, you can build, and which groups of objects, or ‘flocks‘, you can shepherd around so that they are collected together inside one of these fences.

As you build fence after fence, and form flock after flock, you begin reflecting on how your fences, and the flocks enclosed within them, work. Three things about building fences stand out:

First, you discover that you can not only collect together everyday objects to form flocks by building fences around them, but you can also form flocks of flocks by building large fences around smaller fences. For example, if you have built a fence around St Paul Minnesota, and you have built another fence around Minneapolis, Minnesota, then you can build a third larger fence that encircles both the fence around Minneapolis and the fence around St Paul, and a new flock is formed that contains both of the original city-flocks.

Second, you discover that you can subdivide flocks into smaller flocks. For example, if you have built a fence around Minneapolis, then you can build a smaller fence separating South Minneapolis from the rest of Minneapolis. And in fact you can do this for any flock and any sub-collection of objects in the flock: If X is some collection of objects contained in a flock you have already formed by building a fence, you can build a second fence inside the confines of the first fence that separates the objects in X from the other objects that are in the flock but not in X, to form a new, smaller flock that contains exactly the objects in X. You can even do this when X is empty, by building a fence so small that it contains nothing at all within its borders.

Third, you discover that fences don’t have a privileged side. Of course, sometimes fences look different on one side than another. But this is only an aesthetic concern–from the perspective of using fences to separate objects into flocks, there is no difference between one side of a fence and the other. As a result, if you build a fence that separates some collection of objects X from all other objects (the non-Xs) and forms the Xs into a flock, then that same fence also collects together the non-Xs and forms them into a flock.

Reflecting further on these three discoveries, however, you suddenly discover something disconcerting: building fences is impossible!

Occasionally you have doubts about this third discovery. But anytime you do, you imagine a fence built along the equator. You then ask yourself: would such a fence be a fence around all of the objects in the Northern Hemisphere, or a fence around all of the objects in the Southern Hemisphere? The only reasonable answer is that such a fence would be both, and what holds for the equator-fence should hold for all fences whatsoever.

Reflecting further on these three discoveries, however, you suddenly discover something disconcerting: building fences is impossible! Imagine that you build a fence–any fence–enclosing some collection of objects X. Then, by the second discovery, you could build a second fence that collected all of the objects in the first flock that are not identical to themselves–since there are no such objects, this would be a small fence forming a flock that had no objects whatsoever in it (what we might call the empty flock). But by the third discovery, if this fence separates all of the objects in the empty flock from every other object–that is, all objects whatsoever–then this same fence fences in a second flock that contains every object whatsoever (what we might call the universal flock). According to the first discovery, flocks are themselves objects that can be collected together and used to form other flocks. In particular, if the universal flock collects together all objects whatsoever, then the universal flock is in fact one of the objects that is contained in the universal flock. Thus, some flocks are in fact contained in themselves! Hence, by the second discovery, we can build a fence around exactly those objects contained in the universal flock that are themselves flocks that are not contained in themselves. But now we need only ask: Is this final flock contained in itself or not? By definition, it is if and only if it isn’t, and we are faced with a contradiction.

Now, at this point we could argue about whether it is the principles of carpentry, or the principles of shepherding, or both that are to blame. But this would be silly. The puzzle just described is a variant of a familiar set-theoretic paradox that has nothing to do with either carpentry or shepherding: The Russell paradox. We have formulated the puzzle a bit differently than is normally done, however. Instead of merely laying down a comprehension principle that states, loosely put, that for any condition C there is a set that contains exactly the objects that satisfy C, and then constructing the contradictory Russell set from there, we instead arrived at the paradox via combining two independently plausible set-theoretic principles:

Given any set S, and any subcollection of objects X all of which are members of S, there exists a set that contains exactly those objects in X.

Given any set S, there exists a set that contains exactly those objects that are not in S.

The first principle is an informal version of the Axiom of Separation, which is one of the standard axioms of the widely studied and widely accepted theory of sets known as Zermelo Fraenkel Set Theory with Choice (or ZFC). The second principle is the Axiom of Complement, which is not an axiom or theorem of ZFC (since if it were we could derive a version of the paradox above). But it is an axiom of other, alternative set theories, such as W.V.O. Quine’s New Foundations (NF).

Now, obviously we can’t have both Separation and Complement as axioms of our set theory. Most of us trained in mainstream contemporary mathematics have been taught that there is something natural and almost inevitable about rejecting Complement and retaining Separation in the face of the Russell paradox. But that seems wrong to me. As I have tried to show with the fence-building story told above, both of these axioms have a rather strong appeal grounded on basic intuitions one might have about collecting objects. Perhaps we–that is, the philosophical and mathematical community–have been too quick to opt for Separation (and hence ZFC). Separation does seem intuitively obvious, but then so does Complement–or at least it does to me.

So what exactly are we to do?

Featured image credit: ‘Sheep’, by Hans. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Fences and paradox appeared first on OUPblog.

February 13, 2016

The many deaths of David Bowie

On 8 January 2016, on his 69th birthday and two days before he died, David Bowie released Blackstar, an album replete with images of death, but also hints of the possibility of its transcendence. “Lazarus,” the third track sung from heaven where he was as free as a bluebird, appeared to announce his rebirth into yet another of the series of personae he inhabited throughout his career. And, even though he was himself absent from it, his death and the music and videos in which he dramatized it together precipitated the most extensive media storm of his career. For the previous 45 years, Bowie’s public fabrication and annihilation of alter egos always aspired to such visually and aurally innovative media spectacles.

After his early mod dabbling with the blues, his first rejection of the period’s rock ’n’ roll personae was met with little success. Fey Dylanesque folk ditties performed by a long-haired waif in a dress—albeit, he insisted, a man’s dress—had few links to late 1960s cultural touchstones. And so, when his early musical efforts failed to attract attention, he turned to mime and acting, gaining small roles in several film projects, including one in a short experimental melodrama, The Image (Michael Armstrong, 1969). Here, Bowie haunts an artist who is painting a portrait of him, driving the artist to such a point of distraction that he stabs his inspiration to death. The same year, Bowie’s manager, Kenneth Pitt, produced a promotional film, Love You till Tuesday (Malcolm J. Thomson), featuring the recent hit, “Space Oddity,” and seven more Bowie compositions, including “The Mask,” in which Bowie mimes in accompaniment to his spoken voice-over story. Bowie recounts how his performances with a mask he finds in a junk store become so popular that he is invited to appear at the London Palladium—where the mask strangles him.

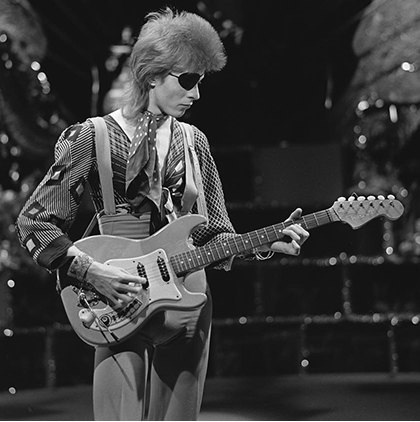

David Bowie, shooting a video for “Rebel Rebel” on AVRO’s TopPop, a Dutch television show, in 1974, after he killed his famed alter-ego, Ziggy Stardust. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

David Bowie, shooting a video for “Rebel Rebel” on AVRO’s TopPop, a Dutch television show, in 1974, after he killed his famed alter-ego, Ziggy Stardust. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Bowie persevered with the combination of death and doppelgänger motifs, and when he abandoned the shibboleths of expressive authenticity that the counterculture prized to create Ziggy Stardust, the progress of his future career was assured. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars (1972), his fifth album, changed everything: his music, his persona, and his position in the mass media. Recorded in late 1971 and early 1972, ten of its eleven songs were his own compositions, featuring a harder rock sound than he had recently favored. But rather than identify with it himself, Bowie projected the music onto the alter ego of an extra-terrestrial rock star. His performances as Ziggy—a star, but also an alien “Starman“—created a cult around him that he sustained for over a year, before he abruptly dispatched Ziggy in a “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide.”

Projections of these multiple alter egos in strongly visual, dramatic performances that culminate in death were integral to Bowie’s Ziggy concerts, and thus to D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary film of the last of these shows at Hammersmith Odeon on 3 July 1973, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1973). Enacting a utopia of communality within a dystopia of artifice, Ziggy’s performance was, like the countercultural spectaculars it invoked, a ritual event both within and beyond the alienation of commodity relationships, one celebrated jointly by David Jones, David Bowie, Ziggy, the Spiders, his fans, and Pennebaker’s crew—and the film’s viewers. As Ziggy brought these together, the summary performance of communal suicidal redemption occurred twice: once immediately before the intermission, when in the last stanza of “My Death,” after the line “for in front of that door, there is…,” one audience member then another calls out, “Me!” and Bowie smiles slightly and says, “Thank you.” And again just before “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” the climactic final song of the concert and the film, when Bowie made an astonishing announcement: “Not only is this the last show of the tour, but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do.”

Terminating Ziggy’s career freed Bowie to develop the personae that made him arguably the most important musician of the 1970s, as well as a leading innovator in the period’s distinctive form of audio-visual composition, the music video. He had already written his own best epitaph in “The Man Who Sold the World,” when his alter ego replied to the voice who thought him dead: “Oh no, not me, I never lost control.”

Image Credit: “David Bowie – Aladdin Sane” by Piano Piano! CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The many deaths of David Bowie appeared first on OUPblog.

The shame of marriage in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure

When the Supreme Court concluded the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges hearings with a 5–4 vote to legalize same-sex marriage, the majority and dissent disagreed as on the place of marriage in constitutional law, a question related to divergent views of the institution’s historical purpose. The majority insisted that marriage has always been about love and companionship, the dissent that it has always been procreation. The two sides did, however, find one striking point of agreement: the Justices were unanimous in their conviction that marriage is a relationship of unique virtue and dignity. This general agreement that marriage has always been a sign of virtue and dignity overlooks a key moment in the history of marriage as well as the that of the founding of the United States as an independent nation — that of the early Protestant Reformation.

The Protestant Reformation is conventionally understood as elevating conjugal love above lifelong celibacy. In this view, Catholics had distrusted marriage as a sign of attachment to the world, the flesh, and the devil and seen virginity the mark of a pure, uncompromised faith that set the clergy apart from the laity. By contrast, this story goes, Protestants deemed marriage the highest spiritual state for clergy and laity alike.

This narrative of the rise of companionate marriage overlooks much of the actual writing of leading reformers like Luther and Calvin as well as the views of many sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English Protestants. To be sure, there were many popular pamphlets supporting clerical marriage as part of the institution of Protestantism in England. And Luther, Calvin, and other Reform theologians did insist on the holiness of clerical as well as lay marriage. But their reasoning was more complex and less celebratory than we have supposed.

In fact, following St. Augustine, Protestant Reformers affirmed that, in Luther’s words, since the fall, “the sin of lust… flows beneath the surface” of matrimony. Whereas our prelapsarian parents could Augustine argues, control their sexual organs as voluntarily as their hands and feet, postlapsarian humanity cannot follow the command to “go forth and multiply” without also indulging the shameful passion that followed original sin.

Mariana by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Aberdeen Art Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Mariana by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Aberdeen Art Gallery. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsAccordingly, the Protestant claim that marriage may be holier than virginity rested on the conviction that although celibacy remained the spiritual ideal, it was possible only for the chosen few who, by singled out by God’s special grace, were “eunuchs for heaven,” preternaturally free from carnal desire. For the vast majority of humanity, attempts to remain celibate would result only in secret masturbation, fornication, and resentment toward God. Marriage, if followed, was a sign of holiness because it offered a humble, public acknowledgment of one’s innate human depravity and absolute dependence on God’s grace for salvation. In England, doubt over the spiritual status of sex even within marriage was manifested in the refusal of many Protestants, including Elizabeth I, to accept communion from married clergy.

We get one expression of this ambivalence about marriage in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Rather than celebrate marriage, Measure for Measure treats it as a form of salutary public shame. The title of this play, as we know, derives from Matthew 7:1–2: “Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged, and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.” Most obviously, this sentiment addresses the hypocrisy of Angelo, who has been left by the Duke of Vienna to enforce long-ignored laws prohibiting fornication and prostitution. Angelo abuses his authority, demanding that the novice nun Isabella sleep with him in exchange for the pardon of her brother, Claudio, who along with his pregnant betrothed, Juliet, has been condemned to death for premarital fornication. Isabella consults with a Friar who is, unbeknownst to her, the Duke in disguise. The Friar/Duke arranges a bed-trick in which Mariana, Angelo’s discarded fiancée, will replace Isabella; Angelo, according to this plan, will believe he has slept with Isabella and pardon Claudio. Angelo, however, refuses to honor the bargain. Amidst multiple pardons and punishments that converge in the play’s conclusion, the Duke pardons Claudio and Juliet, and orders Angelo to marry Mariana. He thereby transforms hypocrisy and sin into legitimate matrimony.

At least, that would be the Duke’s account of the play’s conclusion. Yet insofar as Angelo is one of three characters compelled to marry, he is aligned with Lucio, a gentleman forced to marry a prostitute, and Isabella, whom the Duke himself is determined to marry. The forced marriages with which Measure for Measure concludes not only yoke together partners who do not love each other; read in light of Protestant theology, they also punish Angelo, Lucio, and Isabella for refusing the humility that characterizes the true Christian. According to patristic and Reform writing, even if the avowed celibate didn’t succumb to secret sin, those who maintained physical virginity could still be guilty of pride in their own purity. In ordering all of the major characters to marry, the Duke compels them to recognize the sinful humanity they share with the pimps, perverts, prostitutes of Vienna.

Measure for Measure was first performed in 1604, just three years before English Protestants made their initial attempt to establish a permanent settlement in America. Attention to the theological resonances of this notorious problem play allows us to appreciate the paradoxical relevance of Christian theology to a queer challenge to the idealization of marriage as an institution. For, unlike Obergefell opinions, or the (imagined) American mainstream they address, the English who funded and participated in the colonization of the Americas were aware of a deeply held suspicion that the sexual impulse could not be sanctified by marriage; it could only be confessed. Attention to the complex history of marital ideology—Measure for Measure is but one example—can help us to think anew about the sexual values we take for granted, as well as the politics they imply.

Featured image credit: Golden bond by Abhishek Jacob, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post The shame of marriage in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure appeared first on OUPblog.

Divine Command Theory and moral obligation

‘Divine Command Theory’ is the theory that what makes something morally right is that God commands it, and what makes something morally wrong is that God forbids it. This is the second part of my original OUPblog post.

Of the many objections to this theory, the four main ones are that it makes morality arbitrary, that it cannot work in a pluralistic society, that it makes morality infantile, and that it is viciously circular. This article is a reply to the first of these objections, that divine command theory makes morality arbitrary.

This objection is often tied to Plato’s dilemma, stated in the Euthyphro (10a-11b): Is the holy loved by the gods because it is holy, or is it holy because it is loved by the gods? Socrates makes it clear that he favours the first of these options. But his actual argument is unsatisfactory. He uses, without justification, the premiss that the holy is loved because it is holy, and then shows that once this is admitted, the holy and the god-loved are not the same. But what the objection to divine command theory needs is a justification for this premiss. The closest the dialogue gets to a justification is in the earlier discussion of divine disagreement (7e-8a), where Euthyphro concedes that disagreement requires that the parties think different things to be just, beautiful, ugly, good, and bad, and therefore love different things. But this is only an argument against divine command theory if we accept that all evaluative properties are in the same way ‘real’ in the Platonic sense, and that is just what is at issue here.

John Mackie already saw that the best reply to the objection from arbitrariness is to distinguish different evaluative properties (Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong, Penguin, 1977). God is not arbitrary if God selects which good things to require, and so to make obligatory for us. The term ‘arbitrary’ is a trap here. A decision can be arbitrary in the antique sense that it is within God’s proper discretion (in Latin, arbitrium) but not arbitrary in the modern sense that implies that some relevant consideration has been ignored.

If we say that God selects which good things to require of us, does that simply return us to Plato’s preferred horn of the dilemma, that the holy is loved by the gods because it is holy. This threatens to put some standard of goodness or holiness over the divine, and so threatens idolatry. We will have fallen into this same danger if we make God’s decision about obligation depend upon some standard of goodness independent of God. But nothing has yet been said about what goodness is. It may be that goodness depends upon God just as obligation does, but the dependence is of a different kind. Robert M. Adams (in Finite and Infinite Goods, OUP, 1999) argues that goodness (in the sense of excellence) is resemblance to God. This is probably too restrictive an account, since it does not cover well the excellences of natural kinds. We might add that goodness includes what draws us to God, and what manifests God (or shows God to be present). These suggestions all give criteria for goodness, and this needs to be distinguished from giving the meaning of goodness. Perhaps to say that something is good means that it draws us and deserves to draw us, and our criteria then tell us which things are good in this sense.

All this is philosophical work still to be done. The present point is that if we distinguish in this way between evaluative properties like ‘good’ and evaluative properties like ‘obligatory’, and if we make both depend upon some relation to God (different in the two cases), we will have responded to the arbitrariness objection to divine command theory while still making morality depend upon religion. We can say that there are two different priority relations within divine command theory between goodness and obligation. On the one hand, the good is prior to the obligatory because everything that is obligatory is good, but not vice versa. We might call this ‘priority in account’, since goodness will enter into the account of what God chooses to require. On the other hand, obligation is prior to goodness, because it is, so to speak, trumps. We might call this ‘priority in accountability’, since we are finally accountable to what God requires of us.

Featured image credit: Photo by Richard Walker. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Divine Command Theory and moral obligation appeared first on OUPblog.

February 12, 2016

Queering America and the world

“We had him down as a rent boy,” remarked a bartender in Brussels about Salah Abdeslam, one of the suspected jihadists in the recent Paris attacks. Several reports noted that Abdeslam frequented gay bars and flirted with other men. These revelations were difficult to slot into existing media narratives and stood in uneasy relation to his posited allegiance with the group best known in the United States as ISIS. After all, there have been numerous credible reports of ISIS’s violent condemnation and abuse of queer people. In many instances, the penalty for homosexuality has been death.

Meanwhile, a select number of those who have fled war-torn Syria to seek resettlement in the United States have identified as LGBTQ. Their fears are many: the violence of a state takeover by ISIS, the oppressive regime of President Bashar Assad, being “found out” as queer, and becoming stateless, among others. But the process for resettlement is long, tenuous, and mired with red tape meant to keep them from entering the United States, where expressions of populist anti-Islamic sentiment (and pushback against gay marriage) are mainstream news. Furthermore, refugee policies in North America favor heteronormative families, while popular culture often pathologizes both migrant sexualities and foreign regimes of LGBTQ oppression.

A few months ago, we were invited to contribute to colloquy in the journal Diplomatic History on the topic of “Queering America and the World.” With all of these realities so pressing, it seems like queering US diplomatic history in its various expansive manifestations shouldn’t be particularly hard. But it is. Although the reasons are many, one is particularly significant: What do we mean by queer and queering? The field of queer studies has tackled this question for over two decades. We are not reinventing the wheel, but rather emphasizing what the United States and the World field has to contribute to this conversation, and how it may be implicated in it.

Of course we mean to insist on a focus on queer people—the soldiers, state department officials, transnational activists, aid workers, merchants, artists, and those, like Ugandans targeted by Christian leaders, who find themselves under the shadow of US influence. At times, this includes those who identify, or are identified, as queer, as well as those whose lives and work are shaped by that reality. Perhaps they are vulnerable to attack: roughed up, tortured, or fired from work and harassed at home. Perhaps, even at the same time, they are involved in sexual rights movements, protests, and the creation of new domestic and international politics.

All the while, queer perspectives also acknowledge the kinships, passions, and playful and sexy encounters—oftentimes jumbled together—that lead to new understandings in the United States and across borders. When satirists send dildos to Oregon militias or use Photoshop to superimpose them on terrorist or GOP-wielded AK-47s we are treated to a different vision of US militancy. But beyond such mockery, imperialist and foreign affairs have long been loaded with tropes and practices of seduction, intimacy, dominance, and penetration, as well as binary models of gendered power. Whether we’re talking about the secrets shared by spies, the partnerships between statesmen and women, or the transnational bonds linking gay activists, we aim to take the relationships part of special relationships seriously.

In the end, we also want queering the United States in the World to mean asking hard questions about the archive, about how stories are told and meanings are stabilized. It isn’t enough to talk about sex, although we want that too. We imagine also asking about what kinds of narratives the archives allow us to tell, and what is gained by viewing them askew, newly, or in a way that is off the straight and narrow path. The richness of queer life, after all, rarely finds reflection in official records, even when they speak strongly to its probing and regulation. Reversing that dynamic and queerly interrogating our source base aligns us to the important work of many others unwilling to be shaped by the priorities and orientations of history’s victors.

Some might fear that moves to queer the field of the United States and the World may trivialize its work, but we think the opposite: queerness is and should be everywhere, including queer people, and sexual politics, and methods of thinking queerly. It’s urgent to examine how power, including manifestations such as settler colonialism and consumer capitalism, both shapes and works through sex, intimacy, and affective life. But queering, while informed by political needs in the present, also helps us understand many historical events and processes that continue to exert tremendous effects in the world. Recent stories from Europe and the Middle East only remind us of that longer history. Like earlier revelations about US torture, they reveal sexuality’s complex imbrication with transnational circulations and geopolitical affairs, including US-sponsored wars and their aftermaths.

Like any intervention in a scholarly field, the practices of queering the history of US foreign relations will evolve as they are tested and reoriented. And we have to remain vigilant to ensure that in queering the study of the United States and the World we don’t court ahistorical thinking about what queerness means or looks like, or encourage forms of US exceptionalism. Yet it is exciting to imagine how US diplomatic historians’ skills and strengths—including their attention to international relations, creative use of multi-sited archives, and interest in changing power relations between people and nations—might enhance ongoing processes of queering happening in other subfields and disciplines. Our colloquy points to keywords, research questions, and methodologies through which queering promises to provide fresh impetus and complexity, even as it acknowledges that the bounds and definitions of the term “queer,” much like the fates of many LGBTQ refugees and activist projects, remain in flux.

Image Credit: “Bandeira LGBT no Congresso Nacional” by Antonio Cruz. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Queering America and the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Why ‘ageism’ is bad for your health

According to research conducted by Levy, Slade, Kunkel, and Kasl in 2002, the average lifespan of those with high levels of negative beliefs about old age is 7.5 years shorter than those with more positive beliefs. In other words, ‘ageism’ may have a cumulative harmful effect on personal health. But what is ageism – and what is its impact, both for society and healthcare?

Although it may at first seem paradoxical – that a fear of old age actually brings our twilight years nearer – it does make sense. If one’s self perception of the ageing process is more positive, then dealing with these inevitable changes will be that much easier. Despite this, in our youth- and beauty-obsessed culture, old age can look very frightening. It appears, like Shakespeare’s grim vision of the ‘last scene of all’ as a:

Second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

– Jacques’ speech from ‘As You Like It’, Act II, Scene VII (1599)

As is evident, ageism (the stereotyping and discriminating against individuals or groups on the basis of their age) can be directed just as much against the self, as others. Yet we all know that old age can be, and indeed is, so much more than this. It should be cherished just as much as any other time of life.

The many dimensions of old age have been valued in societies around the world, throughout recorded history. For instance, in a passage from the Insinger Papyrus from Egypt’s Ptolemaic period (c. 305-30 BCE), it was stated that ‘old age’ (anything above 40 years old!) was what ‘Thoth has assigned to the man of god.’ The attainment of old age was evidence of special divine favour, and (as is common across many societies), old people were well-respected both for their experience and wisdom. Similarly, in the English ballad ‘The Ages of Man’ (c. 1775), although failing health is acknowledged:

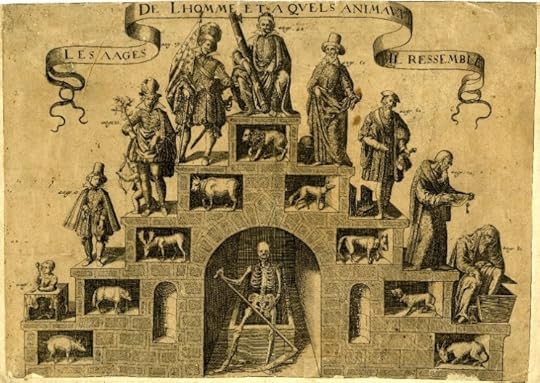

Image Credit: ‘Les Aages de Lhomme et a Qvels Animavx il Ressemble’ (Late Sixteenth Century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Les Aages de Lhomme et a Qvels Animavx il Ressemble’ (Late Sixteenth Century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Age did so abate my strength,

That I was forced to yield at length.

It is also noted that:

My neighbours did my council crave

And I was held in great request.

Akin to such views, perhaps the pendulum in our society is swinging back at last, away from anxious (and unhealthy) aversion, towards a greater realism and warmer acceptance of age. Not a week seems to pass without old age making the headlines – whether it is the latest demographic data on our ageing society, the contested budgets and policies for the care of older people, a famous novelist calling for euthanasia as defence against the ‘silver tsunami’, or polarised debates about assisted dying. Whilst this may seem initially negative in tone (and a great deal of it is) – it does foster debate, awareness, and public understanding of the issues surrounding ageing. Nowhere is this more evident, than in the medical profession.

During the past century, life expectancy in many parts of the world rose from 50 to 80 years. As more and more people live longer in their old age, the impact on general practitioners, medical wards, operating theatres, and community initiatives grows. For accurate diagnosis and treatment, older people who are ill need more intensive examination and more tests than younger people. Add to this the complexity of increased incidence of adverse effects of drugs, and the need for specialist medical and nursing care in high technology hospital environments becomes obvious.

If we approach these problems in a positive, constructive manner, the whole of society benefits – not just ‘the old’. Geratological medicine is concerned with quality of living, but is not centred on prolongation of life at any cost. To every life an end must come, and ensuring that the end is comfortable, calm, and dignified, and that families and loved ones are not left a legacy of guilt and regret, is part of the duty of a geratological team.

Image Credit: ‘Old Age, Youth, The Hand’, by debowscyfoto. CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

Image Credit: ‘Old Age, Youth, The Hand’, by debowscyfoto. CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.The medical understanding of ageing has evolved as well – now generally defined as ‘what sets the morbidity process into action.’ Behind the news, a debate about ‘successful’ versus ‘usual’ ageing is ongoing, and flourishing. Such debates revolve around the concept identified by Cicero’s Cato Maior de Senectute (‘On Old Age’) over two centuries ago – that old age, if approached properly, harbours opportunities for positive change and productive functioning. Much ink has been spilled in the quest to define these terms, perhaps usefully, but a workable conception of ‘successful’ ageing, when it emerges, will have to take account of current issues surrounding disability, dying, and our attitudes towards age.

The task for geriatricians remains the optimal treatment of all aspects of ageing: social as well as clinical. In terms of clinical, educational, research, and spending priorities there have been new developments in emergent models of care – with better evidence for the treatment of many geriatric conditions, and the greater importance of social and ethical issues. Our task today is to better understand, and therefore better treat the problems associated with age. If such positive attitudes are maintained – of both society’s and our own self-perception – we can all look forward to those extra 7.5 years!

Featured Image Credit: ‘The Three Ages of Man’ by Titian (c. 1512), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why ‘ageism’ is bad for your health appeared first on OUPblog.

The importance of long-term marriage for health and happiness

Each year around Valentine’s Day, a new crop of romantic comedies hit the silver screen. Viewers wait in anticipation for the on-screen couple’s first kiss, or the enviably lavish wedding. But what happens to that couple, many decades after the first kiss or exchange of rings? Recent research shows that long-married couples exchange love and emotional support, but also regularly engage in spats or minor conflicts which affect older adults’ health in both expected and surprising ways.

In recent years, research has flourished on long-married couples, with attention to the complex ways that marital support and strain affect both partners’ health, happiness, and even cognitive functioning. Due in part to the collection of large sample survey data sets that obtain information from husbands and wives over time, researchers are moving away from studies that focus on just one partner’s appraisal of the marriage, and instead look at the ways both partners’ marital experiences affect their own and one another’s health.

A special section of Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences recently featured three studies that explored linkages between marital quality and health. The first study showed that supportive marriage is an important resource that protects against poor health, disability and functional limitations in later life. Choi, Yorgason and Johnson examined changes in marital quality and health among couples in their 50s and older, based on data from the Health and Retirement Study. They found that over a four-year period, increases in marital quality were linked with improvements in self-rated health and declines in disability. They also found that increases in positive aspects of marriage, such as feeling loved and supported by one’s partner, led to declines in disability and functional limitations of the other partner, such as difficulties getting up out of a chair. Why would having a happy and satisfied spouse improve our own physical health? The results suggest that a spouse who feels loved and supported may enhance the other spouse’s sense of competence as a husband or wife. Knowing one’s relevance and value in the significant other’s life may also bolster physical well-being.

When researchers expand their foci to include psychological health, including daily feelings of frustration, worry, and sadness, they find similarly that one partner’s marital happiness may affect the other partner’s mood, but in surprising ways. Carr, Cornman and Freedman explored how older husbands’ and wives’ feelings of marital support and strain affected both their own and their spouses’ daily mood. Using daily diary data from the Disability and Use of Time study, they found that wives reported high levels of frustration when their husbands reported strain in the marriage; unhappily married men may create frustration for their wives, or alternatively, frustrated wives may criticize their husbands, undermining the men’s happiness with the marriage. Surprisingly, though, when wives reported high levels of marital support, their husbands reported higher levels of frustration, perhaps because the help they exchanged undermined husbands’ feelings of autonomy or competence.

While Carr and colleagues showed the potentially troubling aspects of high marital support, a third study found surprising protective effects of marital strain for older adults’ cognitive health. The research team of Xu, Thomas and Umberson explored whether negative and positive interactions in marriage were associated with one’s cognitive limitations over time. Using data from the Americans’ Changing Lives (ACL) study, they discovered a surprising finding: husbands and wives who reported higher levels of strain in the marriage went on to have slower increases in cognitive limitations. What would explain this curious finding? The authors suggest that marital strain can be protective, as these strains may come in the form of nudging one another to take better care of their health. In other cases, the demanding situations or verbal sparring that accompany marital conflicts may sharpen the spouses’ attention, reasoning, and speed of processing – the core components of cognitive functioning in later life.

In the movies, romantic relationships are portrayed as all hearts and flowers. Yet mature couples who have stayed married for four or five decades find that love encompasses both supportive moments and moments of strain and scolding. Strain and support are not opposite sides of the coin, but are tightly interwoven components of long-term marriages that may bolster (or threaten) older adults’ physical, emotional, and cognitive health in complex ways.

Image Credit: Old People, Elderly Couple, Rain by marmax. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The importance of long-term marriage for health and happiness appeared first on OUPblog.

The romance of chocolate

Is chocolate an aphrodisiac? Gifts of chocolate are given usually with that intent at this time of the year. Does it work? Well, maybe; gastronomy is known as the sister art of love.

Women often crave chocolate. In 1648, according to the diary of English Jesuit Thomas Gage, the women of Chiapas Real arranged for the murder of a certain bishop who forbade them to drink chocolate during mass. Not long after, ironically, the bishop was murdered by someone who had added poison to his daily cup of chocolate.

In order to understand why chocolate is so enjoyable we need to consider the contents of chocolate. Chocolate contains an array of compounds that contribute to the pleasurable sensation of eating it. Many of these compounds are quite psychoactive if they are able to get into our brain. Are they the reason that we love chocolate so much? Yes.

Chocolate usually contains fats that may induce the release of endogenous molecules that act similar to heroin and produce a feeling of euphoria. German researchers reported that drugs that are able to block the actions of this opiate-like chemical produced by eating chocolate prevented the pleasure associated with eating chocolate. Chocolate also contains a small amount of the marijuana-like chemical called anandamide. Although this molecule can easily cross the blood-brain barrier, the levels in chocolate are probably too low to produce an effect on our mood by itself.

In contrast to its effects on men, women more often claim that chocolate can lift their spirits. In a study of college students and their parents, 14% of sons and fathers, and 33% of daughters and mothers met the standard of being substantially addicted to chocolate. Women seem to have very strong cravings for chocolate just prior to and during their menstrual cycle. Chocolate may provide an antidepressant effect during this period. In one study researchers found that women in their fifties often develop a sudden strong craving for chocolate. Why?

Chocolate contains magnesium salts, the absence of which in elderly females may be responsible for the common post-menopausal condition known as chocoholism. One hundred milligrams of magnesium salt is sufficient to take away any trace of chocoholism in these women, but who would want to do that? Finally, a standard bar of chocolate contains as many anti-oxidants as a glass of red wine. Clearly, there are many good reasons for both men and women to eat chocolate to obtain its indescribably soothing, mellow, and yet euphoric effect.

Chocolate contains phenethylamine (PEA), a molecule that resembles amphetamine and some of other psychoactive stimulants. When chocolate is eaten, PEA is rapidly metabolized by the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO). Fifty percent of the PEA you consume in a chocolate bar is metabolized within only 10 minutes. Thus very little PEA usually reaches the brain, consequently contributing little or no appreciable psychoactive effect without the use of a drug that can inhibit MAO. Could this happen? Possibly yes. MAO levels are at their lowest level in premenstrual women, which is the time when women most crave the soothing effects of chocolate.

The main point is that plants, such as the pods from the cocoa tree, contain a complex variety of chemicals that, when considered individually, are not likely to impact our brain function. However, when considered in aggregate they may exert complex and multiple effects throughout the body. Sometimes other ingredients are added to the chocolate to enhance it effects. Long ago, chili was used as a key ingredient in the fortifying chocolate drink the great ruler Montezuma. He claimed it made his tongue dance and his pulse quicken in preparation for his daily visit to his beautiful concubines. At least for Montezuma, chocolate was an effective aphrodisiac.

Featured image credit: Chocolate. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The romance of chocolate appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond the noise barrier

Noise barriers are not regarded with a great deal of affection. In fact, they’re not much regarded at all; perhaps not surprisingly, given that the goal of their installers is to ensure that those who benefit notice neither the barrier nor the noise sources it hides. The majority are basic workmanlike structures, built according to tried and trusted principles: their ability to reduce sound depends primarily on density and dimension. In order to reduce the noise level by about 5 dB a barrier must have 10 kg under each square metre of surface, and be high enough to hide the sound source from view. Adding extra height provides further reductions of about 1.5 dB per additional metre. (A 5 dB reduction corresponds roughly to halving the perceived loudness).

Just like every other kind of noise reducing element, introducing noise barriers at the earliest design stage of a noisy new project is far superior to retrofitting them. But in reality, at least in the UK, most barriers are sticking-plasters rather than structural elements. This is because, by the time anyone (with any relevant authority) realised that roads, railways and airports are none too pleasant to listen to, most of them had already been built. The widespread introduction of noise barriers to UK roads and airports was triggered largely by the efforts of pioneering noise campaigner (and creator of the Noise Abatement Society) John Connell. Hence their usually uninspiring appearance (as you can see in the image included).

Noise barriers along a highway near Sharon, Israel, by Mattes. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Noise barriers along a highway near Sharon, Israel, by Mattes. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.But maybe we should learn to love noise barriers, or at least to consider their potential. In principle they offer a canvas for artwork, for the collection of energy (solar, acoustic, vibratory), for noise measurement (and hence sound mapping), for the absorption of chemical pollutants from engines exhausts, for illumination, planting, and wildlife habitats.

Carefully designed noise-barriers can reduce annoyance in other ways than simply by reducing noise. For example, while planting vegetation on the quiet side of barriers will not attenuate noise significantly unless the layer is very deep (it takes about 25 metres of forest to reduce noise by 5 dB), a natural-looking screen can significantly reduce the number of people whom the remaining noise annoys. Installation of such a barrier can have the same effect as a 5 dB noise reduction according to one study, simply because of the positive reactions most of us have to natural (or natural-looking) scenery.

With HS2 on its way, Heathrow expansion on the table, new roads being planned, and old transport infrastructures crumbling, maybe now is the time to rethink our barriers and even — who knows — to love them.

Featured image credit: The elevated Fushi freeway with soundproof wall on the left-hand side, by Hat600. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beyond the noise barrier appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers