Oxford University Press's Blog, page 556

January 26, 2016

Shadows of the digital age

The Bodleian recently launched a festival celebrating drawing. As part of this, the artist Tamarin Norwood retreated to our Printing Workshop, turned off her devices and learned how to set type.

Tamarin Norwood setting tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Tamarin Norwood setting tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.She proceeded, in her inky and delightful way, to compose a series of Print Tweets.

Metal tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Metal tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.At the end of the day, she launched Twitter and shared with the world what she had done. For the eight hours she was offline, it must have felt lonely being digital in our human age.

Print tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Print tweet. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.The shadows of the digital age have us looking – even longing for – the tangible. We seek to embrace what the artist and poet David Jones described as the ‘actually loved and known’.

I see the implications of this every day in the Weston Library, where we house almost 40 kilometres of rare and unique material. We teach increasingly from objects to satisfy the academic and student appetite for material culture. While we digitise in order to share collections and offer practical surrogates, we remain alive to the demand for the artefact which digitisation often stimulates. A scholar recently requested access to a collection of children’s games, images of which were readily available. How otherwise, she argued, could she assess patterns of use? Our exhibitions draw larger and larger crowds, and our reading rooms have never been busier – indeed last year, across the Bodleian libraries as a whole, we saw a 7% increase in physical visits.

When pursuing new acquisitions from specialist dealers, we have to compete harder and faster with peer institutions. It is a relief when an electronic sale catalogue lands in the inbox first thing in the morning, because it gives me a jump on sleeping competitors across the pond. The print catalogue, interestingly, continues to thrive despite its declining commercial utility. The things that get snapped up the quickest are those which, if you like, have a concentrated thingness. We recently had to fight hard at auction for a copy of John Aubrey’s Miscellanies annotated by his friend Robert Hooke.

Suffragetto. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Suffragetto. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.Thankfully we didn’t have to compete for a recent donation of over 1500 games and puzzles dating from as early as 1791. The public interest generated by this collection has been considerable. Until 6 March people can visit our current display of a selection of these, including Suffragetto, an apparently unique strategy game of 1917, in which the police and suffragettes compete to take control of the Albert Hall and the House of Commons.

Outside the library we see vibrant sales of vinyl and a wide variety of 35mm film. Spotify, the audio streaming service, now offers its subscribers its own version of the mix tape – that old-fashioned way of anthologising music, often as tokens of friendship or love.

Digital algorithms are seeking to emulate the human heart. People demand the online stuff, but they cherish what’s offline.

It’s interesting looking at trends in our legal deposit intake – that is, the books that UK publishers are obliged to send us under legislation. They can elect to send copies electronically now, and an increasing number do so, particularly academic publishers. Oxford University Press sends in both formats, for which we are grateful. But alongside the rise in electronic deposit, we are seeing a renaissance in new titles with high production values and alluring often self-referential design. Those slyly nostalgic Lady Bird books for adults could never be given or received for Christmas digitally.

A satisfaction in the durability and relevance of the analogue does not, of course, mean that the opportunities and challenges represented by the digital should not be fully embraced. Our digital stock across the libraries is on the increase, purchased as well as deposited, and we have a particular responsibility to meet the needs of those researches whose library spaces are defined more in the virtual than the physical sphere, and whose texts are streamed rather than bound.

But if some forms of content are shifting towards the electronic, digital also enables new means for the interpretation of the analogue materials we continue to value so much.

Shelley. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Shelley. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.We recently announced the acquisition of a long-lost poem by Percy Shelley, printed in Oxford in 1811 but never actually seen until the only known copy resurfaced in 2006. In order to protect its commercial potential – absolutely locked into its analogue status – the dealer handling it embargoed any form of access. When we finally got hold of it we were able to digitise and encode it and offer it up freely to the world.

Such enabling opportunities abound. We are undertaking mass digitisation of Greek and Hebrew manuscripts to add to the millions of images already shared. We teach electronic editing of documents and seek ways to exploit increasingly sophisticated innovations – for example, using image-match technology to trace genealogies of print and at some point, we hope, to identify and collate handwriting spread across a large corpus of material.

Facilitating this deeper understanding of the analogue through innovative digital tools forms an increasingly important element of our work. But I want to come back to and conclude with the question of digital content and in particular the challenge of its preservation.

Early on artists and writers seized upon the new media’s potential to subvert notions of permanence embodied in the book form and enshrined by collectors, curators and librarians. One of the most notable examples is Agrippa A Book of the Dead.

Agrippa. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Agrippa. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.This project, dating from 1992, was a collaboration between the writer William Gibson, the artist Dennis Ashbaugh, and the publisher Kevin Begos. Their intention was to create a physical book whose images were designed to fade and whose embedded floppy disk played a poem which ate itself as it scrolled along. You see here that the typographical structure imitates that of the Gutenberg Bible – although the text in this case gives us the genetic make-up of the fruit fly.

Agrippa Verse. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.

Agrippa Verse. Courtesy of Chris Fletcher.Satisfyingly, the experiment was not wholly successful. The self-immolating verse escaped onto the web; the ink fading technology was never, I think, achieved beyond prototype; and collectors, curators, and librarians now carefully conserve examples of the very book intended to mess with their heads. Our two copies were generously presented by Kevin Begos a few years back and exert a powerful presence in seminars on material culture.

The digital obsolescence Agrippa set out to achieve has, of course, been happening on a massive scale; and I echo an observation made recently by Vint Cerf of Google that unless we all ramp up our efforts to capture, preserve and make accessible the born digital traces we increasingly generate, future historians are going to struggle.

In particular, I am thinking of the sorts of materials we would term special collections in the analogue world: ephemera, corporate records, correspondence, diaries and archives detailing our social networks. It is interesting to note that just this week Friends Reunited wound up business. What is happening to the data accumulated by that social network – perhaps, through its re-match making, the very genesis of a number of people reading this piece?

We collect the archival paper record of Oxfam (ten thousand boxes and counting), but the accruals of material are increasingly electronic. The collections of contemporary scientists come with datasets and their correspondence usually exists only in the cloud. We can trace the history of the Marconi Company through the physical records we hold – but where do we look to explain the financial crash from the inside out? How do we reconstruct the electronic unfurling of the Arab Spring? The Library of Congress has recently risen to the challenge of collecting Twitter and we must see how that works out.

The Bodleian made a start some while back. We harvest websites and extract emails and files from obsolete hardware. We are training up a new generation of Digital Archivists equipped to make incursions into the ether. But there is a great deal more to do. I accept to some degree the Darwinian position that what will last, will last; and acknowledge that the delete button can be a valuable friend. But as the present rages with debate about what we choose to remember or forget of the past, I still believe we need to leave the future something to think about.

After all, we’re curious. Human.

This is an edited extract from Chris Fletcher’s address at the launch of the Humanities and Digital Age programme, led by The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities at Oxford University, on 21 January.

The post Shadows of the digital age appeared first on OUPblog.

New Year’s Resolutions for the music classroom

It’s a bright new year and time to shed off the old, but that doesn’t mean we can’t partake in some favored traditions – especially making New Year’s resolutions. If you’re a teacher or professor, the New Year usually means a new semester, and the opportunity to start fresh by teaching a new class, or bring rejuvenation to your students post-holiday.

In this spirit, we asked some Oxford University Press music education authors for their thoughts on this time of year, their advice or inspiration for other educators, and their own goals for 2016. Here’s to a bright new year and a productive spring semester!

* * * * *

“A new year. A new semester. A time when teachers throughout the world are designing new lessons and experiences for their music classrooms. A music educator’s role is to provide highly engaged, relevant, and innovative learning opportunities and to instill and inspire in each student a lifetime pursuit of learning and of music. Students can reach educational goals when provided opportunities to be productive and successful learners. Enthusiasm for all music genres, enjoying collaborations, celebrating successes – these are things that inspire students to continue learning beyond the confines of the classroom.”

–Shelly Cooper, Professor, Music Education at the Fred Fox School of Music, University of Arizona and author of Becoming a Music Teacher: From Student to Practitioner

* * * * *

“If you are anything like my students, you have a great love for music, whether it’s creating it, performing it, or perhaps a little of both. In addition you most likely became a music teacher because you wish to share your passion for music with others, just as one of your music teachers lit that spark for you. As we begin a new year, my advice would be to never lose sight of why you began your musical journey in the first place or the emotional hold that music has over you. Smile more, move more, make more music, and talk less about music. Be open to a diversity of modes of musicianship and try to help all your students tap into their innate musicality.”

–Gena R. Greher, Ed. D. Professor, Coordinator of Music Education, 2014-15 Nancy Donahue Endowed Professor of the Arts, Education Supervisor, UMass Lowell String Project, and co-author of Computational Thinking in Sound: Teaching the Art and Science of Music and Technology

* * * * *

“Happy New Year! This time of year, I am often asked how to address issues between music educators and special education faculty and staff. Unfortunately, this question is sometimes posed as a thinly disguised statement of blame regarding a co-worker. The shiny new school year has sometimes worn off and differences in teaching style, professional behaviors, and personal issues sometimes bubble up once winter sets in. In these instances, I stand ready to immediately start speaking before another teacher chimes in with an approving and complimentary statement. During this quick moment, I restate the question and flip it to convey my baseline stance that every one of us is doing our very best each day. I know this is true for me and assume it is true for everyone else.

“In fact, I state that I go to work every day with an external presence that conveys my belief that everyone in my educational environment is as committed to the group goals as I am. I continue to project that authentic and optimistic truth until I am thoroughly proven wrong or until those around me rise to my enthusiastic commitment to teaching and learning. Through this work hard and be nice strategy, my students have achieved greater successes and my medication for hypertension has been avoided. However, I have also sometimes been proven wrong and have then extricated myself from teaching situations that were personally and professionally toxic. Our mental and physical well-being is necessary to be able to change the lives of our students.

“The reward is still in the eyes of our students. This is why we teach.”

–Alice Hammel, instructor at James Madison and Virginia Commonwealth Universities, and co-author of Teaching Music to Students with Special Needs: A Label-Free Approach and Teaching Music to Students with Autism, and co-editor of Winding It Back: Teaching to Individual Differences in Music Classroom and Ensemble Settings

* * * * *

“I’m both a practicing musician and an educator. I’ve long found that by working on my own skills as a cellist, singer, pianist, improviser, and composer, my pedagogical skills benefit automatically. Let me tell you three things I’ll do as a musician in the weeks and months to come. I hope these ideas will be useful to you, too, and above all to your pupils!

Deepen my friendship with the metronome. I use an old analog Dr. Beat, with settings for beats, time signatures, subdivisions, and triplets. It’s a real help to listen to the metronome and organize my musical impulses and physical gestures according to the information the metronome offers me. Getting the hang of hemiolas, three-against-four, five-per-beat, accented off-beats, and all the others puts me on the path to rhythmic, technical, and musical freedom.

Deepen my friendship with slow practice. I don’t mean slow and plodding, but slow and smart, slow and alert, slow and beautiful. The fastest way to master a difficult passage is to practice as slow as necessary, as many times as necessary. And besides being productive, slow practice is incredibly pleasant.

Deepen my friendship with the stage. Recently I decided to practice in front of people, so to speak. I invited a handful of friends to come and watch me practice. In their presence I tried a number of new pieces, as well as a number of different interpretations of the same piece. Here and there I repeated a phrase or part of a phrase if I thought it merited a little editing or a little affirming; here and there I played a piece or a long section of a piece in a somewhat slower, more careful version; and here and there I took a piece and turned into a repeating loop, playing it three or four times in a row. I asked my friends for their feedback as regards the pieces, my interpretations, my stage management, and so on. We all had a wonderful time. It was so good that I’ve decided to make a habit of it.”

–Pedro de Alcantara, musician, writer, and author of Indirect Procedures: A Musician’s Guide to the Alexander Technique

* * * * *

“No doubt you’ve heard the old saying, ‘If you aim at nothing you’re sure to hit it.’ The New Year is a great time to reflect professionally and think about what you’d like to accomplish in the short and long term. Periodically setting and revisiting professional goals (such as building a course website, committing to sending a personal note to the parent of each student during the semester, or applying for a graduate program) is an action itself that will make you more productive.

“Ask yourself: ‘Where do I want to be professionally one, three, and 10 years from now?’ List tangible action points for each of your goals and start chipping away at your list. I set and keep track of goals (in a variety of categories) using a Google Doc, but there are many other ways (paper and pen, mobile apps, etc.) to do the same. Keep your list short; too many goals can be daunting.

“Maybe you’ve set some worthy goals, but the busyness of the daily grind diverted you. Living day-to-day but not looking at the ‘bigger picture’ is easy to do, but the New Year provides an opportunity to reset! I look at it this way: Even if you do get a little distracted and fall short of a goal, at least you’ve made some progress. When I began my doctorate at Temple University in Philadelphia, for example, I expected it would take five or six years. For a variety of reasons it ended up taking eight, but I’m still glad I set out on what ended up being a rewarding journey.

“Try setting some short and longer term goals this year. I know when you look back next year you’ll realize that setting goals made a difference!”

–Scott Watson, music teacher at Parkland School District, Allentown, PA, adjunct instructor for University of the Arts and Cairn University and Central Connecticut State University, and author of Using Technology to Unlock Musical Creativity

* * * * *

“As music educators, there is always more that we can do for our students and profession–form a new music group, create more community and outreach opportunities, provide additional one-on-one assistance to our students, join another important committee. However, in the grand scheme of things, music educators tend to act and give at their own detriment, risking burnout and, ultimately, a different career path. Therefore, it is important to treat each new semester as an opportunity to take stock in how our personal energies are invested and to refresh intentions of self-care, not only for our own well-being, but also for our music students. In my music education courses, my students speak of plans to care for themselves after they graduate: ‘When I am done with school and only teaching, I will be better about taking care of myself.’ We talk about how life becomes more rich and more complicated with each passing year, especially for music educators, and that if they do not start to take care of themselves now–to carve out a small piece of time for just themselves–then they probably never will, and fantastic music teachers will become victim to exhaustion and weariness. Therefore, to help them in their efforts, there is an unrequired requirement in my classes that everyone spend three consecutive hours each week doing something completely unrelated to school or work. They can sleep, cook, exercise, binge-watch a television show, hang with friends or family, read for fun … whatever they want, guilt-free. Each week, my students report back to the class and share what they did for themselves; each week, they are more excited to share and increasingly speak about how special that time was for them. As a new semester is now upon us, I am preparing my own agenda of ‘me’ activities to weave into the coming weeks to help keep me grounded, mentally healthy, and aware of myself in the midst of the craziness. As a result, I know that my thinking, teaching, and research will be deeper and stronger, which not only benefits me, but my students as well.”

–Bridget Sweet, Assistant Professor of Music Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and author Growing Musicians: Teaching Music in Middle School and Beyond

* * * * *

Image Credit: “Fall Middle School Orchestra Concert 2013” by Meredith Bell. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post New Year’s Resolutions for the music classroom appeared first on OUPblog.

Should design rights protect things you can’t see?

Although many EU IP lawyers are currently concentrating on the trade mark reforms, the Commission is quietly getting on with its study of the design protection system in Europe.

The remit of the study is wide-ranging, but perhaps the most surprising issue that has arisen is whether design law in the EU should protect things that you can’t see.

Design law has long been considered the junior partner to some of the other IP rights – patents (which protect inventions), trade marks (which protect brands) and copyright (which protects literary, artistic and musical works). Design rights (called design patents in the USA) protect how something looks. Readers may recall that the appearance of the Samsung tablet computer was one of the main issues in the design dispute between the Korean powerhouse and Apple.

At first blush, the EU’s answer on invisible designs seems easy – Article 3 of the Designs Regulation says that design law protects the appearance of a product or part of a product. So one would have thought that invisible designs can’t be protected – they can’t have an appearance because they can’t be seen.

But this is complicated by a provision of the same EU-wide legislation that removes protection for spare parts. The debate about whether or not spare parts should be protected has been long and vigorous, in the simplest terms pitching EU member states with large car manufacturers against the rest. Those against protection for spare parts say that competition is required in the market to keep prices down. Those in favour say that safety is enhanced by ensuring spare parts are manufactured under licence from the car maker. Motorists, unsurprisingly, say that they want spare parts to be both safe and cheap.

In the end, in passing the Regulation in 2001, the legislators engaged in something of a fudge – they removed protection for invisible spare parts – spark plugs, carburettors and the like, whilst maintaining EU-wide protection for spare parts that are visible, including wing mirrors, bumper-bars and the like. To be protected, a spare part (called in the legislation “a component part of a complex product”) must remain visible whilst in “normal use”.

The somewhat clumsy formulation for what is a spare part has created all sorts of litigation around what is normal use, and just how visible does something have to be to be protected. But what has sometimes been ignored is the corollary of the spare parts limitation – if spare parts have to be visible to be protected by design law, that means that anything that is not a spare part does not have to be.

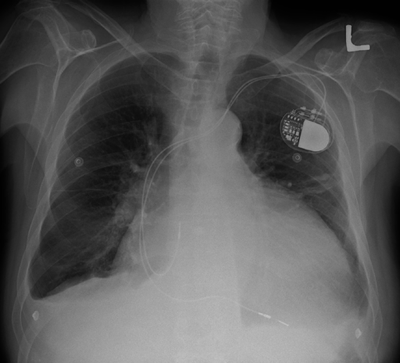

Image credit: ‘Cardiomegally’ by James Heilman. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: ‘Cardiomegally’ by James Heilman. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Take, for example, a pacemaker, which is fitted by a surgeon into the human body to keep the heart functioning. Once fitted, the pacemaker is not visible – except perhaps on an X-ray machine of some sort. EU design law currently protects the appearance of the pace maker (if it is otherwise valid), because it is not a spare part – it does not have to be visible whilst in normal use.

Our early simple answer is therefore incorrect. Rather, EU design law does protect invisible designs, so long as the design is not for a spare part. And one can readily see why. There are plenty of good examples of “invisible” designs that are currently protected, and which have a real economic value. In the food field, there is customer drive for innovative designs inside gateaux, ice-cream cakes and sausages. In building industries, design adds value to many materials which will eventually be wholly encased in concrete, plaster or grout.

It was a case about biscuits that can perhaps be credited with causing at least some of the confusion referred to above. Biscuits Poult applied to register a design for half a chocolate chip cookie, with the broken edge showing chocolate fondant or similar inside. A rival baker sought to invalidate the registered design, producing earlier designs showing either whole chocolate chip cookies, or cookies with interior fondant – but not the combination of the two. When the matter got to the General Court (the second highest court for EU-wide design registration matters), it was, thankfully, no longer seriously argued that the fondant was a “spare part” of the cookie. But the General Court decided this:

“Therefore the Board of Appeal did not err in stating … that the non-visible characteristics of the product, which do not relate to its appearance, could not be taken into account in the determination of whether the contested design could be protected, nor in concluding … that ‘it [was] not necessary to take into account, in the examination of the individual character of the design, of the filling inside the cookie, as portrayed’.”

Thus the interior fondant was ignored, even though it appeared quite strikingly on the registration certificate, because of some notion of it not being visible at some point.

The General Court’s decision is clearly wrong – and it is a shame that Biscuits Poult didn’t appeal further to the Court of Justice to have it overturned.

Where does that leave the study? It is widely expected that the study will not suggest a wholesale re-write of EU design law. By many accounts, the key issue is harmonising spare parts law as between member states. As mentioned above, the Designs Regulation removed EU-wide protection for invisible spare parts. But at member state level, the Designs Directive took a different approach, leaving it to member states to decide. Until that can be harmonised, there can be no single EU market in any product with spare parts. Currently some member states provide protection for spare parts, and stop the shipment of non-originator spare parts across their territories. Whichever side you’re on, a single system across the EU has to be better for consumers than the current complicated patchwork.

The result of trying to obtain harmonisation of the national spare parts regime is that we’re unlikely to see any attempt to remove design protection from invisible designs that are not spare parts. But if that is proposed, serious thought will need to be given to the concept of “normal use”. When applied to spare parts, that’s pretty obvious – the normal use of a car will be driving it. And in most cases with machinery, the interior spare parts won’t be visible whilst in normal use. It’s a little harder with a biscuit – many would say that normal use is eating it – when the interior will be visible.

The report of the study is due out shortly.

Featured image credit: ‘Festive cookies’, by stevepb. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Should design rights protect things you can’t see? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 25, 2016

‘Mate’ in Australian English

In anticipation of Australia Day, 26 January, we spoke to our colleagues down under what they would be celebrating. The answer: Australian English, of course. The following is an extract from What’s Their Story?: A History of Australian Words by Bruce Moore.

Mate is one of those words that is used widely in Englishes other than Australian English, and yet has a special resonance in Australia. Although it had a very detailed entry in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (the letter M was completed 1904–8), the Australian National Dictionary (AND) included mate in its first edition of 1988, thus marking it as an Australianism. A revision of the OED entry for mate was posted online in December 2009, as part of the new third edition, and this gives us the opportunity to test the extent to which the word can be regarded as Australian. Not one of the standard presently used senses of mate in OED is marked Australian. What are they doing to our Australian word?

One of the OED senses that matches an AND sense is mate used as a form of address. OED says: ‘used as a form of address to a person, especially a man, regarded as an equal.’ This sense has been in use since the sixteenth century. The OED notes that mate is not used in this sense in the United States, and Australians will be aware from its use in British television programs that it is not exclusively Australian. It is interesting, however, that the OED’s one quotation to illustrate the sense after the 1940s is from the Australian novelist Peter Carey in 1981, in an example that demonstrates its use by a woman: ‘“Come and sit here, old mate.” She patted the chair beside her.’

The AND definition differs slightly from the OED one: ‘a mode of address implying equality and goodwill; frequently used to a casual acquaintance and, especially in recent use, ironic.’ Examples of the ‘ironic’ usage include: (1953) ‘I’ll remember you, mate. You’ll keep!’; (1957) ‘I’ve just been sweating on an opportunity to do you a damage, mate.’ The quotations chosen to illustrate the OED entry, do not include this ironic, and sometimes hostile, use of the term. This range of usage with the primarily positive mate is analogous to the range of usage with the primarily negative term bastard in Australia. Bastard is mainly used in a derogatory way, as it is in all Englishes, but in Australia it can also be used in a good-humoured and even affectionate way. Sidney Baker captured the range of meaning when he wrote in 1943: ‘You are in a pub knocking back a few after work and being earbashed by a mate. At length he reaches the point he has been rambling round so long and, after a pause, you (the bashee) say: “You’re not a bad old bastard—for a bastard!”’ The heavily ironic Australian use of mate is enshrined in a famous quotation from Australian political history. In 1983, Labor Party leader Bill Hayden recalled a moment when there were rumours that he was to be dumped as leader, and a colleague comforted him ‘Oh, mate, mate’. Hayden commented: ‘When they call you “mate” in the N.S.W. Labor Party it is like getting a kiss from the Mafia.’ Although possibly not exclusively Australian, this ironic and sometimes hostile use of mate is certainly more common in Australia than elsewhere.

The primary Standard English sense of mate is illustrated by this OED definition: ‘a companion, fellow, comrade, friend; a fellow worker or business partner.’ It is this part of the sense that receives special attention in the Australian National Dictionary. The first thing AND does is to separate out some shades of meaning, and so one of them is: ‘an acquaintance; a person engaged in the same activity.’ This sense covers quite a range of relationships, but the essential point about it is that the relationship involves no close bond of friendship. Typical examples include: (1919) ‘The boy had joined his mates in one of the little cemeteries on the Western front’; (1934) ‘Seventeen of our mates were killed in the mining industry last year’; (1972) ‘A mate in Australia is simply that which a bloke must have around him. Mates do not necessarily want to know you.’

This separation prepares the way for the essential Australian sense of mate, and the sense that validates its inclusion in a dictionary of Australian words: ‘a person with whom the bonds of close friendship are acknowledged, a “sworn friend”.’ Some of the central quotations that establish the sense are these:

(1891) Where his mate was his sworn friend through good and evil report, in sickness and health, in poverty and plenty, where his horse was his comrade, and his dog his companion, the bushman lived the life he loved.

(1977) ‘He’s me mate. I gotta help ’im,’ he stated simply and incontrovertibly.…

There was no answer to that, Gunner knew: the outcome of this incident had been predetermined by the peculiar chemistry of compatibility, by social mores and by the almost tribal ties of marriage, all pledged with countless beers. It was personal, traditional, and deeply masculine.

GOLD COAST, AUSTRALIA – APRIL 25 : Memorial service with War Veterans Remembers Anzac Day on March, 25 April 2011 in Gold Cost, Australia.

GOLD COAST, AUSTRALIA – APRIL 25 : Memorial service with War Veterans Remembers Anzac Day on March, 25 April 2011 in Gold Cost, Australia.Especially in many of the early examples of this kind, the emphasis is, as in these passages, strongly masculine. Henry Lawson writes in 1913: ‘The man who hasn’t a male mate is a lonely man indeed, or a strange man, though he have a wife and family.’ And a writer in the Bulletin in 1945: ‘You can’t kid me that a woman could ever be a mate like you an’ me know it.’ In 1960: ‘“My mate” is always a man. A female may be my sheila, my bird, my charley, my good sort, my hot-drop, my judy or my wife, but she is never “my mate”.’ In the early records there are occasional references to women, but when they do occur they lack the intensity of emotion associated with the male references: (1923) ‘My wife is standing at the gate—No man could have a better mate’; (1946) ‘Sally was elated by his recognition that she could be a good mate.’ It is intensity of emotion that characterises the male references: (1986) ‘Silence was the essence of traditional mateship. … The gaunt man stands at his wife’s funeral; his mate comes up, says nothing but rests a gentle hand briefly on his shoulder.’

In addition to mate, the word mateship appears in the quotation at the end of the last paragraph. In Standard English, mateship can mean ‘the state of having a mate; a pairing of one animal with another’ (OED), but it is the human sense of mateship that is exclusively Australian. The OED defines it as ‘the condition of being a mate; companionship, fellowship, comradeship’, and labels it ‘chiefly Australian and New Zealand’. AND defines it: ‘The bond between equal partners or close friends; comradeship; comradeship as an ideal.’ Some of its seminal and early uses, not surprisingly, come from Henry Lawson, since it is a concept that was forged in the bush tradition. In ‘Shearers’ (1901) Lawson writes:

They tramp in mateship side by side—

The Protestant and Roman

They call no biped lord or sir

And touch their hat to no man!

And in ‘Before We Were Married’ (1913):

River banks were grassy—grassy in the bends,

Running through the land where mateship never ends.

It is a tradition that is continued in the First World War, and memorialised in the remembering of that war: (1935) ‘The one compensating aspect of life as then lived was the element of mateship. Inside the wide family circle of the battalion and the company were the more closely knit platoon groups.’

When in 1999 Prime Minister Howard proposed a draft preamble to the Constitution that included the sentence ‘We value excellence as well as fairness, independence as dearly as mateship’, there was some public outcry over the inclusion of a term that, because of its role in a male tradition, appeared to exclude half the population. Prime Minister Howard argued that mateship was ‘a hallowed Australian word’, although his co-author in the draft preamble, the poet Les Murray, confessed that it was ‘blokey … a man’s thing’. This debate was a sign that the Australian myth, which mateship embodies, perhaps no longer has the power that it held in the past. The association of mateship with Australian egalitarian traditions was articulated most clearly by Russel Ward in The Australian Legend (1958): ‘He believes that Jack is not only as good as his master but, at least in principle, probably a good deal better. … He is very hospitable and, above all, will stick to his mates through thick and thin, even if he thinks they be in the wrong.’

The power of this myth may have weakened, but it is only through an understanding of the historical background of terms such as mate and mateship that we can understand why they have such a central place (even when contested) in the Australian psyche, how their Australian meanings differ from their Standard English meanings, and why they belong to the core set of terms that the core set of terms that help to express Australian values.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Oxford Australia blog and the OzWords blog.

The post ‘Mate’ in Australian English appeared first on OUPblog.

Time to follow through on India and Japan’s promises

It is no secret that India-Japan relations have been on a strong positive trajectory over the past 18 months. Soon after taking office in 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made Japan his first foreign destination outside of India’s immediate neighborhood and while in Tokyo, he and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe upgraded the India-Japan relationship to what they called a “Special Strategic and Global Partnership.” Indeed, with a broad array of common or complementary interests ranging from the need to respond to the rise of China, to the need to manage their opposite demographic and economic trajectories (India has a large youth population and a rapidly growing but capital-poor economy, whereas Japan has a long-stagnant but capital-rich economy and ageing population), the two countries have numerous potential avenues for mutually beneficial cooperation.

At the time of Modi and Abe’s first official meeting as prime ministers in 2014, the two sides agreed to deepen their cooperation in a wide range of areas such as defense, nuclear issues, economics, and people-to-people exchanges. From the Indian perspective, the meeting was widely deemed a success, particularly in terms of Abe’s pledge to generate roughly $30 billion worth of Japanese official development assistance (ODA) and foreign direct investment (FDI) into India over a five-year span. Yet there were still areas with visible gaps between the two sides, for instance with the long-negotiated civil nuclear cooperation remaining unfinished and the Indian side refusing to upgrade the defense and foreign ministries’ “two plus two” dialogue to the ministerial level. Indeed, these outcomes were symptomatic of the broader historical relationship between India and Japan in that lofty rhetoric of increased cooperation were made with relatively little attention being paid to the minutiae of how such promises would be turned into reality.

PM and Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe, at the Restricted Meeting, at Akasaka Palace, Tokyo by Narendra Modi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

PM and Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe, at the Restricted Meeting, at Akasaka Palace, Tokyo by Narendra Modi. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The second prime ministerial meeting between Modi and Abe, which took place in Delhi last month, appeared to move forward on a number of big-ticket items. Several days before Abe’s arrival, Delhi announced that it had accepted a roughly $15 billion Japanese plan to build India’s first high-speed rail, choosing the Japanese plan over a Chinese proposal. The deal appeared to be a win for both sides, with Japan beating out its most significant rival in implementing the project, while India is now set to benefit from Japan’s widely acknowledged prowess in railway technology. Once Abe arrived in India, the elusive civil nuclear agreement between the two governments also appeared to approach a conclusion, with the two prime ministers announcing that the deal would be signed pending the finalization of technical details.

Still, it bears repeating that grand pronouncements by heads of governments frequently fail to produce any real change on the ground once the media attention surrounding an official visit wanes. Although friendly rhetoric and gestures have an important place in international relations, the India-Japan relationship has long been hampered by a lack of concrete and ambitious action to follow through on promises, rather than a lack of amicable discourse. Despite the fact that the two countries have pledged to improve their economic cooperation for over a decade, their bilateral trade has remained paltry, with both countries having a far more robust economic relationship with China, which is also a major strategic competitor for both sides. As such, rather than patting themselves on the back, the Indian and Japanese governments must now turn to the difficult task of translating words into action. For instance, the agreement in principle on civil nuclear cooperation is certainly a positive step forward, but, as the saying goes, the devil is in the details, and those are yet to be worked out. Similarly, Abe’s promise of Japanese FDI will be heavily reliant on the private sector, so the natural question to ask is how Japanese firms—which tend to be somewhat risk-averse compared to their Korean counterparts, whose ventures in India have been largely successful—will be coaxed into investing in an Indian market that lacks the level of infrastructure, predictability, and efficiency that these firms are used to at home. There are many such outstanding questions but the most important is how soon will the Indian and Japanese people be able to palpably reap the benefits of their countries’ political embrace?

In this context, the relative lack of rigorous, policy-relevant academic analysis on the India-Japan relationship is problematic. Whereas several of India’s other important international relationships, for instance with Pakistan, China, and the United States, have been studied and written about at great length, there remains a dearth of literature on India-Japan relations that would pave the way for successful implementation of the two prime ministers’ stated commitments. In doing so, it is important to acknowledge not just the boundless opportunities for cooperation that exist between the two countries, but also the real challenges that preclude them from fully translating intent into outcomes. Chief among these challenges are a mutual wariness of antagonising China; cultural differences in the way business, politics, and society operate; and basic normative differences over key issues such as climate change and nuclear energy. A true accounting of the potential of the India-Japan partnership would do more than exhort the two countries to embrace each other ever more tightly in their proclamations. It would acknowledge that actions speak louder than words.

Featured image credit: “Eastern end of longest platform in Kollam Junction railway station in India. This is the world’s second longest railway platform.” by Arunvrparavur. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Time to follow through on India and Japan’s promises appeared first on OUPblog.

The truth about “Auld Lang Syne”

“…I may say, of myself and Copperfield, in words we have sung together before now, that

‘We twa hae run about the braes

And pu’d the gowans fine’

‘—in a figurative point of view—on several occasions. I am not exactly aware,’ said Mr. Micawber, with the old roll in his voice, and the old indescribable air of saying something genteel, ‘what gowans may be, but I have no doubt that Copperfield and myself would have frequently taken a pull at them, if it had been feasible.'”

Over the years since it was written, many millions must have sung ‘Auld Lang Syne’ (roughly translated as ‘days long past’) while sharing Mr. Micawber’s ignorance of what of its words actually mean. Most of us go through the year without singing a single song by Robert Burns, and then, within the space of 25 days, sing this one twice on January 1st and 25th. ‘Auld Lang Syne’ has become a fixture of the New Year, Burns night, and many a wedding and ceilidh. It is often sung in the same way: the singers in a circle, holding hands and crossing arms for the last verse (“And there’s a hand, my trusty fiere! / And gie’s a hand o’ thine!”) and has become a ritual to round off a convivial evening, a prelude to farewells and a promise that we will do this again sometime.

Of course it is usually only the first and last verses of Burns’s song that are sung, with the chorus repeated after each. The verse with the gowans (or dasies), the third of five, is rarely aired to perplex contemporary Micawbers; the second is also best omitted, since it encourages listeners, not to go home, but back to the bar:

And surely ye’ll be your pint stowp!

And surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

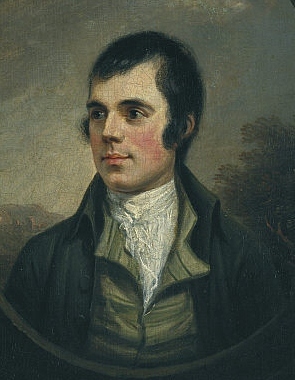

Portrait of Robert Burns, Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840). Scottish National Portrait Gallery, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Robert Burns, Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840). Scottish National Portrait Gallery, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This verse points to a curious fact about this paradigmatic song of parting, that its full lyric actually presents a song of reunion. There was, in Burns’s own time, a traditional Scottish song of farewell, but it was not this one. It was called ‘Goodnight and joy be with you a,’’ and Burns instructed James Johnson to include it as last song in their collaborative collection, The Scots Musical Museum. Burns had already set a lyric to this tune called “The Farewell,” which appeared near the end of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, the volume that shot him to fame. This was written in apparent anticipation of Burns’s emigration to Jamaica:

Tho’ I to foreign lands must hie,

Pursuing Fortune’s slidd’ry ba’,

With melting heart, and brimful eye,

I’ll mind you still, tho’ far awa.

This lyric, accompanied also by the traditional words, is the one used at the end of The Scots Musical Museum.

There are plenty of songs in the Scottish tradition before Burns that are set to a tune called “Auld Lang Syne” but, despite his frequent adaptations of traditional material, Burns’s song does not seem to be based on any of these. He claimed in a letter to his friend Frances Dunlop that “Auld Lang Syne” was “an old song and tune which has often thrilled thro’ my soul” however the words of “Auld Lang Syne” are almost certainly an original composition despite Burn’s claims to the contrary. The fact that he was willing to consider different tunes to accompany these words might confirm this: they first appear in the Museum set to one traditional air, but Burn’s was happy to suggest a quite different one to publisher George Thomson, and it is the latter tune which we use today. This does not suggest his usual reverence for a traditional unity of “old song and tune.”

Burns’s most obvious influence in “Auld Lang Syne” is from an original song by Alan Ramsay, “The Kind Reception” which first appears in a collection of Scots Songs published in Edinburgh in 1718:

Should auld Acquaintance be forgot,

tho’ they return with Scars,

These are the noble HEROE’s lot,

Obtain’d in Glorious Wars. […]

Ramsay’s song is, like Burns’s, a dramatization of reunion: it consists of four verses in the voice of a woman welcoming back her lover from foreign battlefields.

Why did “Auld Lang Syne” come to supplant “Goodnight and joy be with you a’” as the traditional Scottish song of parting, then? Perhaps the answer lies in the differing nature of the absences that they imagine. The speaker of “Goodnight and joy be with you a’” seems to be a criminal going into exile:

The night is my departing night,

The morn’s the day I maun awa:

There’s no a friend or fae o’ mine

But wishes that I were awa.—

What I hae done, for lake o’ wit,

I never, never can reca’:

I trust ye’re a’ my friends as yet,

Gude night and joy be wi’ you a’!

When Walter Scott included a version of this song in The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border under the title “Armstrong’s Goodnight” he ascribed it to one of that notorious border family on the eve of his execution for murder: in the context of The Scots Musical Museum it is more likely to evoke a Jacobite rebel fleeing arrest after Culloden. But political exile in France, like fighting in foreign service in Flanders, was a game for the gentry. “Auld Lang Syne” imagines the end of a more distant absence: “But seas between us braid hae roar’d / Sin auld lang syne.” This song was written and published at the beginning of an age of mass emigration from Scotland. Hundreds of thousands of ordinary people journeyed to America, Australia and New Zealand, in pursuit of “Fortune’s slidd’ry ba.'” Many of them must have taken this song with them, in their luggage and their memories: a song of parting to be shared with new friends and neighbours, but which imagines a reunion with those left behind in the old country, a reunion most of its singers were destined to experience in no other way.

Featured image: Scotland, creative commons license via Pixabay

The post The truth about “Auld Lang Syne” appeared first on OUPblog.

Time and perception

The human brain is a most wonderful organ: it is our window on time. Our brains have specialized structures that work together to give us our human sense of time. The temporal lobe helps form long term memories, without which we would not be aware of the past, whilst the frontal lobe allows us to plan for the future. In addition, we have a powerful sense of the present, the enigmatic ‘moment of the now’, that generates the sensation that time ‘flows.’

But the brain is limited. It cannot handle all of the vast amount of information flooding in through our senses from our environment, so it takes shortcuts and makes approximations. It filters and redacts that data, simplifying it so as to best match pre-existing mental models of expectation. Some of these models will be of genetic origin and some will be conditioned by experience and education. The net result is that the world around us appears stable and consistent with a classical mechanical view of reality: we see objects and observe them moving around a relatively fixed spatial background. Generally, this is a most excellent and reliable model of a reality that we believe is ‘out there.’

But there is an enormous price to pay for this excellence: it is a lie, a complete fabrication. It is such a convincing deception that until about a hundred years or so ago, humans were completely taken in by that classical image of reality. What happened then was the discovery of the quantum. With sophisticated new technologies, scientists managed to prize open the lid of Pandora’s Box and catch a fleeting glimpse of processes that the brain had not been hitherto conditioned to model. And so the situation remains. Our brains have not caught up with the data, with the result that, to quote Feynman, “no one understands quantum mechanics.”

We remain victims of our evolutionary history. We are conditioned to see things in particular classical ways and it is enormously difficult to break free of them, to become converts to new ways of thinking. Of course, resistance to change is usually desirable, for two reasons. Firstly, change is another word for instability, which can be dangerous. Secondly, we should not be gullible to the extent that we believe everything we are told. But on the other hand, lack of change can be just as bad, because that is synonymous with stagnation.

Image credit: Wrist watch men’s by Gadini. Public domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: Wrist watch men’s by Gadini. Public domain via Pixabay.What can we do about it? How can we accommodate significant developments in science?

It seems to me that part of the solution is to try to understand how we think and not only what we think. We should at least be aware of the mental traps set for us by our conditioning. For example, is it reasonable to talk about elementary particles as being waves and particles, and then getting perplexed about that paradox? I think not. We should instead talk only about the signals that our detectors have picked up, because at the end of the day, that’s all we’ve got. Likewise, we should see through metaphysical imagery, such as the frequently stated idea that a particle takes two different paths simultaneously in a double slit experiment, and see such assertions for what they are: unprovable conjectures. Precision in our language is critical here, because our words represent our thoughts and the way that we understand things. For instance, it seems to me that quantum mechanics is not a theory of objects described as if they were wibbly-wobbly matter waves but it’s actually a mathematically based theory of entitlement, a theory that tells us what we can legitimately say in the laboratory, and it is no more than that. That these rules of entitlement do not match our classical, pre-conditioned expectations of reality is a commentary on our evolutionary history and not on the nature of reality.

I am by no means unique in my concern about the way that time and reality are debated: the rise of science and the scientific method can be attributed directly to this debate. For me, one of the most important historical developments was the rise of scientific societies during the seventeenth century. During an age when innocent people were being burned for alleged witchcraft, great thinkers attempted to throw off the shackles of conditioning and start to think in new ways. We would do well, in this day and age, to keep in mind the great motto of the Royal Society of London: Nullius in verba, which means “take no one’s word for it.”

This brings me back to my theme, time. It is an enigma experienced by everyone. It structures our lives, our thoughts, our experiences. We do so want to understand it, to comprehend it, that we will eagerly listen to any exciting conjecture about it, especially if it is presented to us in a slick way. And there’s the rub. How can we distinguish the sound theory from the fairy story, the good from the ‘not even wrong’? How do we know when we are being misled? Is every fanciful view of time legitimate, or can we see when we are being spun a baseless conjecture? It is my proposition that we can train ourselves to think more carefully about time. But that requires patience, and can be very painful.

Featured image credit: Time for a change by Brian Smithson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Time and perception appeared first on OUPblog.

The transcendent influence of law in military operations

From the perspective of military legal advisors, law serves as an enabler in achieving logical military outcomes. Rather than simply focusing on a restatement of law, it is important to offer insight into how Judge Advocates (military lawyers) think about the relationship between law and effective military operations.

Based on the consistency between legal compliance and operational effectiveness, law should not be thought of as impeding military operations. While there are legal and moral reasons a military commander seeks to ensure the conduct of hostilities and other aspects of military operations comply with international and domestic law, first and foremost such compliance enhances the probability of mission accomplishment.

No competent military commander wants to waste resources, whether munitions, personnel, time, effort or morale on actions that are not intended to produce effects that contribute to mission accomplishment. Instead, the efficient allocation of such resources is central tenet of effective military operations, and ultimately rapid and efficient mission accomplishment. What military legal advisers understand is that legal compliance will ultimately contribute to mission effectiveness and resource efficiency, even when the law may be perceived as an impediment to achieving micro-level success.

Law also provides the essential foundation for a well-disciplined force, and the individual and unit accountability. It is this, “good order and discipline” which is the hallmark of a professional military, a component of unit readiness that all military commanders should strive to achieve. True good order and discipline is built on respect for and compliance with law, a foundation that ensures operations are executed effectively not only from the perspective of achieving a tactical outcome, but also from the perspective of doing so in a manner that contributes to strategic legitimacy.

Desired operational effects range from lethal (killing an enemy belligerent) to non-lethal (improving local governance and the corresponding attitudes and perceptions of those in local towns and villages). If a commander doesn’t know what his or her units are doing in the pursuit of these effects; if subordinates are permitted to stray into the inevitably self-defeating abys of an, “ends justify any means” mentality in the conduct of operations, both discipline and mission effectiveness will inevitably be compromised. As a result, commanders must hold subordinates accountable, and law provides the foundation for this accountability.

For example, when an inauspicious incident occurs, it is the commander who has the greatest interest in investigating, establishing true facts, and where appropriate, imposing disciplinary sanctions. Of course, there will frequently be others interested in investigating and assessing responsibility for such incidents. And, when an incident seems to be consistent with a pattern of legal violations, or where there is objective evidence of willful blindness on the part of the military command, external investigation may certainly be appropriate. But for professional armed forces, and certainly US armed forces, this has (and should) rarely be the case.

It may be difficult for those outside the military to appreciate this relationship between law, accountability, and operational effectiveness. Commanders want to know, indeed must know, that they are operating in accordance with law and policy if they are to achieve the desired effects in the battle space. This legal and policy framework impacts every aspect of military operations, not just the conduct of hostilities.

Contemporary discourse on military legal issues often creates the impression that law is the dominant consideration in military operations. This is misleading, not because law is not important in the conduct of operations, but because it distorts the true primary focus of military action: mission accomplishment. Law and policy must, therefore, be understood within this broader context. The nature of contemporary military operations demands commanders who understand this essential relationship between law and mission accomplishment.

Like General McCrystal, the very best commanders understand this nuanced relationship between law and military operations, and the role of military and civilian legal advisors in mission-oriented implementation of legal obligations. Such commanders are fully vested in the actions their unit takes and constantly assess their efficacy, inevitably relying on law and legal advisors to aid in this process.

Featured image credit: Law Enforcement Support missions. US National Guard. Public domain via Flickr.

The post The transcendent influence of law in military operations appeared first on OUPblog.

January 24, 2016

A tale of two militias: finding the right label for the Oregon protests

When an armed group occupied a federal building in Oregon to protest against the US government’s land management, the media quickly seized on the word “militia” to describe them. The Guardian reported the incident with the headline “Oregon militia threatens showdown with US agents at wildlife refuge“; The Washington Post listed the “Key things to know about the militia standoff in Oregon“; and The New York Times described the group as “armed activists and militiamen“. Commenters on social media quickly picked up on this use of language, with one question repeatedly voiced: why were the Oregon group members not being described as terrorists?

Echoing the debate about the use of the word mastermind in the wake of the Paris attacks, the argument about the correct term for the Oregon protestors highlights the politically loaded nature of labels. Words carry potent associations and images, and have the power not only to express the speaker’s views on the subject, but also to influence and form the listener’s opinion. So what are the histories and associations of the two key words in this particular debate: terrorist and militia?

Army or armed rebels?

Militia is by far the older term. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) currently gives a first citation from 1590, at which point it described the body of soldiers in the service of a sovereign or a state. This use—which is basically synonymous with “army”—is now obsolete, having been overtaken by the sense of “a military force that is raised from the civil population to supplement a regular army in an emergency.” It is used to distinguish such civilian groups from professional soldiers, and up until the twentieth century it described official forces raised by order of a monarch or government.

In the 1920s, however, an additional (and in many ways opposite) sense surfaced: militias had emerged that did not work alongside the professional, official army of a country, but rather against it. A militia could now be described as “a military force that engages in rebel or terrorist activities in opposition to a regular army.” The OED’s current first citation for this new sense comes from the Daily Telegraph, where it refers to Italy’s Fascist Militia, also known as the Blackshirts. In the 1930s the term was used to describe both the Republican and Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War. By the 1990s, the term had gained a specifically US association, and was applied to a number of right-wing groups opposed to gun control and distrustful of the federal government.

Revolutionaries and the reign of terror

The term terrorist is nearly 200 years younger than militia, though its associations with political rebellion were present from its inception. The OED’s current first citation dates from 1794 and the era of the French Revolution, where it was used to describe “an adherent or supporter of the Jacobins, who advocated and practised methods of partisan repression and bloodshed in the propagation of the principles of democracy and equality.”

The word quickly gained a more general use, and by the first years of the nineteenth century was being used, in the words of the OED’s definition, to refer to “a person who uses violent and intimidating methods in the pursuit of political aims; especially a member of a clandestine or expatriate organization aiming to coerce an established government by acts of violence against it or its subjects.” The OED’s current first citation for this sense is from 1806, and refers to Republicans in Ireland, but through the intervening 200 years it has been used of countless groups from both ends of the political spectrum. As the OED notes, the word is generally considered to be derogatory and deeply critical. It is rarely seen as a self-applied label, instead reserved as a term to be assigned to opponents and enemies.

Constitutional rights and wrongs

Unsurprisingly, the Oregon protestors do not identify themselves as terrorists, though many on social media have used the label to describe them. Ammon Bundy, the leader of the Oregon protest, responded to this in a phone interview with CNN, stating: “We are not terrorists. We are concerned citizens and realize we have to act if we want to pass along anything to our children.” He distances the protest from both the violence and lawlessness associated with terrorism by emphasizing his role as a “concerned citizen” and family man. Bundy states that the group’s aim is to “restore the people’s constitutional rights,” presenting himself as a “defender” of those rights. By doing so, he attempts to give his cause a legitimacy and justification that would never be associated with terrorists.

This notion of constitutional rights is at the very heart of the protestors’ self-identity, and is intimately connected to their avowed role as a militia. On 29 December, Bundy appeared in a video titled “Breaking alert all call to militias! And Patriots! Bundy Ranch!” where he asked his supporters to gather in Oregon to “make a stand” against the government. In this video, Bundy appears with a copy of the US constitution in his shirt pocket. The second amendment to that constitution famously states: “A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” This statement is, of course, the subject of extensive and ongoing debate, but one thing is clear: “militia” here is being used in the sense: “a military force that is raised from the civil population to supplement a regular army in an emergency.” When the Bundy Ranch blog described the occupation, it stated that: “approximately 100/150 (and growing) armed militia (former US service members) have taken control of Malheur Wildlife Refuge Headquarters in the wildlife reserve.” In their self-identification as a militia, the Oregon protestors are using the term in a solely positive sense, presenting themselves as righteous defenders of their country and constitution.

As we saw earlier, though, there is an ambiguity at the heart of the term militia. When the media use that label of Bundy and his supporters, they are, most likely, thinking of the later sense—that of “a military force that engages in rebel or terrorist activities in opposition to a regular army.” Used in this way, the term loses its sheen of legitimacy, and takes on associations of lawlessness, violence, and fear—the same concepts associated with terrorism. This is a case where two people saying the same word can mean two very different things. It is often said that one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter. Here, it seems that one person’s militia is simply another person’s militia; though it is clear that very different forces may stand under that same label.

Image Credit: “Cliven and Ammon Bundy” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A tale of two militias: finding the right label for the Oregon protests appeared first on OUPblog.

The Guru’s warrior scripture

The scripture known as the Dasam Granth Sahib or the ‘Scripture of the Tenth King,’ has traditionally been attributed to Guru Gobind Singh. It was composed in a volatile period to inspire the Sikh warriors in the battle against the Moghuls, and many of the compositions were written for the rituals related to the preparation for war (Shastra puja) and for the battlefield. The verses generally consist of battle scenes and equate weapons with God, where the sword symbolises the victory of good over evil. War, according to the Tenth Guru, should only be a righteous war or dharam yudh, and it is true that the Sikhs throughout their history have been noted for their exemplary ethics in warfare. Guru Gobind Singh writes in his epic letter known as the Zafarnama that it is only justified to ‘raise the sword once all means have been exhausted.’ The compositions were written in mostly Braj Bhasha, and some smaller compositions are composed in Persian and Punjabi. In contrast to the primary Sikh scripture, the Adi Guru Granth Sahib, which is written in Shanti ras or verses that inspire peace, the Dasam Granth has a heroic strain of expression or Vir ras.

A portrait of the Tenth Guru hunting from the ‘Anandpuri’ recension of Dasam Granth from 1696 AD by Joginder Singh Ahluwalia. Used with permission.

A portrait of the Tenth Guru hunting from the ‘Anandpuri’ recension of Dasam Granth from 1696 AD by Joginder Singh Ahluwalia. Used with permission.In recent times, the Dasam Granth has been of much interest and volatile debate. This debate has its roots during colonialism in the Sikh reformist movement, known as the Singh Sabha. The most controversial and volatile discussion is that of the authorship, which is the most polemic and opinionated argument that one could ever experience. Rather than being concerned with this issue of authorship, it is better that discussions are based on primary sources, like manuscripts and relics.

There is an intrinsic relationship of the scripture to the maryada (traditions), which includes the shastras (weapons), the Takhts (thrones of polity), and the warriors known as the Akali Nihangs. It is important to consider the historical context that the scripture was written in, and its link with battlefield sciences of the period. Whilst the primary scripture is now predominantly seen in Gurdwaras or Sikh temples across the world, during colonialism the Dasam Granth was removed from its ceremonial role, and it actual contents have been overshadowed by the rhetoric of reformist movements.

Illuminated frontispiece of the Dasam Granth, a scripture of Sikhism containing many of the texts attributed to tenth Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh (16661708). (Image credit: “Dasam Granth” from Or. 6298. © The British Library Board, used with permission.)

Illuminated frontispiece of the Dasam Granth, a scripture of Sikhism containing many of the texts attributed to tenth Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh (16661708). (Image credit: “Dasam Granth” from Or. 6298. © The British Library Board, used with permission.)The Sikh warriors practised a martial art known as Shastarvidia and the weapons of choice were the Kirpan and Khanda. The Khanda, or the double edged sword, is also employed in the Sikh initiation ceremony of Khande ki pahul. The sacred ambrosial water is stirred with a Khanda while verses from both scriptures are recited. The initiate drinks the sacred water, and joins the Khalsa or the fraternity of the pure. This new born Khalsa would follow kshatriya ideals and thus be a saint soldier. The Tenth Guru institutionalised both the scripture and the community as the Guru (Granth and the Panth), which put an end to human Guruship. His leadership gave birth to the Sikh Commonwealth or Misals who fought against the Moghals in the eighteenth century.

During and after initiation a Sikh is required to wear the 5 K’s, emblems which start with the letter K, notably the Kesh – long and uncut hair, the Kacchhera – long breeches, the Kirpan – sword, Kangha – comb, and the kara – steel bracelet to be worn around the wrist. In the so-called apocryphal compositions of the Dasam Granth, these emblems are recorded in the composition Nishan-i-Sikhi or ‘Emblems of the Sikhs.’ The composition Rag Asa, defines a Sikh warrior as one who wields the sword and keeps their hair uncut, ‘it is my strict order you should keep kesh and glisten like form of the sword’. This composition is only found in some of the oldest manuscripts of the Dasam Granth:

nishān i sikhī īṁ paṁja haraph i kāph.

These five letters beginning with K are the emblems of Sikhism.

hargez nabāshad azīṁ paṁaz muāph.

A Sikh can never ever be excused from the great five Ks.

kaṛā kārd o kac-cha kaṁghā bidāṅ.

The Bangle, Sword, Shorts and a Comb.

bilā kesa hec ast jumalā nishān.

Without unshorn Hair the other lot of symbols are of no significance.

The Granth of Guru Gobind Singh: Essays, Lectures and Translations (OUP, 2015), pp. 61-62.

The Dasam Granth contains a composition named Shastra Nam Mala or ‘The Rosary of Weapons.’ The verses weave the reader through the names of various weapons together with a cunning set of riddles. This includes the Chakkar or quoit, which Sikhs would adorn their Turbans with. The Chakkar was thrown in battle which was noted by the British during the Anglo-Sikh Wars in the nineteenth century, as well as in the First World War.

Our recent work explores the Dasam Granth Sahib, and is one of the few published works on the scripture in English.

Featured image credit: “Guru Granth Sahib” by J Singh – originally posted to Flickr as _DSC0172-01. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Guru’s warrior scripture appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers