Oxford University Press's Blog, page 486

July 21, 2016

Culloden, tourism, and British memory

As the beginnings of large-scale travel and tourism through Scotland began within fifteen or twenty years of the battle of Culloden, it might have been expected that the conflict would become an early site of memory. Culloden would surely begin to appear as a place in which the confirmatory victory of Great Britain and British values could be implanted. This must have seemed even more likely in the context of the rise in Jacobite relics as Romantic artefacts: garters, flags, and other relics were regularly preserved, In the Highlands, Jacobite landscapes were over-dramatized: for example, British Army draughtsmen rendered Strathtay ‘more dramatic, with loftier peaks and crags’ than was in fact the case. The very geography of Scotland was rendered more alien and forbidding in order to show the importance of what had happened at Culloden, and the challenge it had represented.

Yet for all this, the battle site itself was considered too awkward to commemorate explicitly. Eighteenth century tourists tended to avoid it, even if they visited Culloden House or Clava Cairns nearby. Thomas Pennant in 1769 simply saw Culloden as a place to which ‘North Britain owes its present prosperity’. Sir Walter Scott in Waverley (1814) referred to it only in passing in a novel devoted to the last Jacobite Rising. The carried only one reference to it at all prior to 1822 and only four between 1825 and 1841, though bones began to be carried away by souvenir hunters in the 1830s.

The centenary of the battle in 1846, which-despite poor transport links attracted 3,000 people-seems to have been the start of commemoration and the development of the battlefield as a site to be visited. A memorial was discussed at the centenary dinner, although the initial design of a weeping woman and her child was not pursued. Eventually of course, a simpler and more masculine cairn and ‘clan’ gravestones (always fictional, but treated as genuine memorials even today) were erected at the beginning of the 1880s. By this time, a narrative which saw Culloden as a Scotland-England conflict had developed, and accordingly the cairn (erected by Duncan Forbes of Culloden in 1881) bears the dedication to ‘the gallant Highlanders who fought for Scotland and Prince Charlie’. This process was matched by a final withdrawal of establishment approval of the nature of the British victory. Cumberland’s statue in Cavendish Square was removed from public view in 1868, while Queen Victoria probably had ‘Culloden’ obliterated from his memorial obelisk in Windsor Great Park. Cumberland’s brutality became more and more seen as an obstacle to the premiss of modernization and British unity growing out of a Scotland/England conflict which his victory at Culloden had come to symbolize. If the battlefield was to be remembered, the brutality of the British commander could not be forgotten. As Balmoral itself was redecorated in the 1850s, with a strong royal commitment to Scottish culture and Highland Games, and even as Queen Victoria professed herself a Jacobite, it became progressively easier to incorporate Culloden more inclusively into the cultural memory Meanwhile early Scottish nationalists such as Theodore Napier focused on ‘Culloden Day’ celebrations as a means of commemorating the defeat of the Scottish nation and its way of life.

Memorial at the Culloden Battlefield near Inverness, Scotland by M. Metz. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Memorial at the Culloden Battlefield near Inverness, Scotland by M. Metz. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.From 1937 onwards, the National Trust for Scotland gradually acquired the southern part of the battlefield, and over the following decades supported the burying of telephone lines, the removal of a bungalow and teashop, the rerouting of the Inverness-Nairn road, and the removal of Forestry Commission plantations. The Trust thus recreated a kind of prosthetic version of Highland wilderness on the battlefield. Leanach Cottage, probably dating from the nineteenth century, was part of this. More of the battlefield was acquired, but the fact that the Trust did not possess the areas over which the British cavalry advanced helped to downplay the (critical) importance of cavalry to the outcome of the battle in its interpretations. Instead, the conflict was largely presented as an infantry fight between muskets and artillery on the one hand, and swordsmen on the other: a battle between modernity and the primitive, the old and the new.

By the time of the second generation Centre (1984-2007) there was a strong emphasis on the battle as ‘a civil war’ fired by the reckless dream of Charles Edward Stuart, and the battle ‘the graveyard of the dream for which men died’. This approach continues to dominate: when the 2007 Centre opened in the year of the first Scottish National Party government in Edinburgh, the civil war version of events was stressed strongly to the media. In an era of British unity, the Scottish national dimension of the Forty-five could be stressed with impunity; in the age of Scottish nationalism, it is seen as necessary to remember Culloden as a civil war in order to neutralize its force.

Despite the increasingly evident desire to frame the battle as the culmination of a civil war in order to undermine its potential utility as a shibboleth of political nationalism, the commemoration of Culloden continues to arouse strong feelings. An innocent battlefield re-enactor from Carlisle who came to the 250th anniversary and dressed as a redcoat was spat on on the battlefield, while a proposed soap statue of the Duke of Cumberland in Cavendish Square in 2012, as part of a City of Sculpture art project in London, roused tempers. The deputy leader of Westminster city council probably did not help matters by suggesting that Scots would not find it offensive as English people were not provoked ‘by statues of William Wallace or Robert the Bruce.’ These two figures had not, however, been nominated as one of the ten ‘worst villains’ of British history, as Cumberland had in 2005.

That the memory of Culloden is so highly politicized should tell us something about its continuing importance. Culloden as it happened is in fact much more interesting than Culloden as it is remembered. It was neither a sacrificial hecatomb of Highland history nor a catalyst for the triumph of British modernity. It was the last battle fought on British soil and ended the last armed conflict in which the nature of Britain-and indeed its existence-were at stake. But it was fought between eighteenth-century armies in a more or less conventional way: a simple fact we still find it hard to admit.

Featured image credit: The Battle of Culloden, oil on canvas by David Morier 1746. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Culloden, tourism, and British memory appeared first on OUPblog.

A voice in the background: remembering Margo Quantrell

The documentary Twenty Feet from Stardom (2013) gave us a glimpse of how backing singers—performers who provide vocal harmonies and responses for featured artists—have contributed to twentieth-century American popular music. Their indispensable artistry has helped other people sound good, all while they stood just out of the spotlight; however, the phenomenon of the backup singer has not been unique to the US. For a period in the 1960s, British reinterpretations of American popular music dominated markets on both sides of the North Atlantic. On many of these recordings, a select network of singers can often be heard in the background.

Perhaps the most prolific British female backing singers in this era, the Breakaways supported a wide range of performers including Petula Clark, Dusty Springfield, Lulu, Joe Brown, and Cliff Richard. Vicki Haseman, Betty Prescott, and Margo Quantrell—the original Breakaways—had been members of the Vernons Girls, a chorus of women created in part to market Vernons betting pool by appearing on 1950s British pop-music television shows such as Boy Meets Girls and Oh Boy! Margo (who passed away on 24 June at the age of 74) was perhaps the most constant Breakaway. Some married the performers they accompanied (Hasemen with Joe Brown) or music professionals (Jean Ryder with songwriter Mike Hawker). Quantrell herself would marry drummer Tony Newman, but would remain active as a performer through the 1960s.

The daughter of a truck driver and office worker in Liverpool, music played an important part in the Quantrell family, with her uncles imitating American singers like Mario Lanza and Frank Sinatra, and her father playing piano by ear. She worked as a wages clerk at Vernons where among her tasks she placed cash in individual brown envelopes for the Vernons Girls.

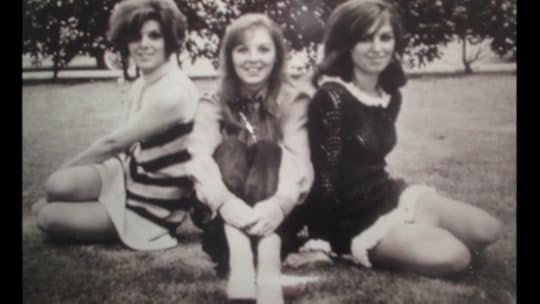

Margo Quantrell, Jean Hawker (née Ryder) and Vicki Brown (née Haseman).

Margo Quantrell, Jean Hawker (née Ryder) and Vicki Brown (née Haseman).One morning, she received an unexpected request to meet with management. “I didn’t know what for… It turned out that, without my knowing, my boss had put my name down for an audition.” Ushered into a room, she was told, “Turn around. Let’s have a look at your legs and see what sort of shape you are. And profile, and smile, see what your teeth are like.” They wanted to “see how you walked, how you held yourself.” The examination treated her more like a pony being prepared for auction than an artist capable of performing flawlessly in difficult circumstances, but, in the end, they were pleased. She would later have a musical audition where the music director told her, “You’ve got it.” Thus began an education that started with learning how to sight-read music and to follow choreographies.

As the currents of 1960s British popular music began to shift, Haseman, Moore, and Quantrell broke away from the Vernons Girls (thus, the Breakaways) to accompany singers like Emile Ford, but they also made their own recordings. Tony Hatch at Pye produced their “That’s How It Goes” and “He Doesn’t Love Me”; however, despite a television appearance on Thank Your Lucky Stars, that disc and others failed to chart. Indeed, none of their solo discs proved as successful as the recordings on which they sang backup.

They would appear on every major British label, backing Petula Clark’s “Downtown” at Pye, Dusty Springfield’s “Stay Awhile” at Philips, Cilla Black’s “You’re My World” at EMI, and Lulu’s “Shout” at Decca. Performing anonymously with Burt Bacharach and His Orchestra and Chorus on “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” and “Trains and Boats and Planes,” they even appeared unnamed on a television special featuring these recordings.

Margo, later in life.

Margo, later in life.The contexts in which they sang ranged from regular appearances on Cilla Black’s television show Cilla to backing American artists when they toured and recorded in the UK. When Jimi Hendrix recorded his first solo release “Hey Joe,” Quantrell and another singer worked through the arrangement with the music director and had a recommendation. Approaching producer Chas Chandler, she suggested that their part would be less obtrusive if sung down an octave, an idea immediately supported by Hendrix. Quantrell knew how a backing vocal should sound: “You know when you hear something and it just doesn’t gel… you know what’s right.”

The Breakaways could arrive at a session, sight-read their parts, and add their own touches to the performance, consequently watching the recording climb to success around the globe, all for a flat session fee and with humility. Quantrell in particular played important behind-the-scenes roles in British pop. For example, her connection to Tony Hatch at Pye and her origins in Liverpool led the producer to hear the Searchers, resulting in a string of British and American hits. Quantrell also put her musical skills to effect in writing “Cruel World” (1963) for singer Julie Grant, suggesting that if women songwriters in England had the same status as Carole King, Jackie DeShannon, and Ellie Greenwich in the US, she might have had another career.

However, the options for professional women musicians were limited in sixties British pop, rock, and blues, and a performer such as Margo Quantrell (who spelled her name “Margot” in the 1960s) remained mostly anonymous. Indeed, the ability that she and other backing vocalists developed was to subvert the identity of their voices so as not to draw attention away from the soloist. In that era, British popular music articulated the role of women as supportive, but not assertive—absolutely necessary, but in the background.

Photos courtesy of Martha Brown (Margo’s daughter).

Featured image: Mic by Skitterphoto, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A voice in the background: remembering Margo Quantrell appeared first on OUPblog.

July 20, 2016

As clean as what?

In anticipation of the post on clean, I decided to say something about the idioms in which clean figures prominently, but chose only those which have the structure as clean as. This means that I am not going to make a clean breast of my errors, wipe the plate clean, or engage in other theatricals. My aim is much more modest: I want to call our readers’ attention to the unimaginably high number of similes of the as…as type in English. In 1918, T. Hilding Svartengren, a Swedish researcher, defended a dissertation with the title Intensifying Similes in English. The text of the dissertation appeared in Lund: a very thick and most useful book. Specialists know and use it, but references to it are rare. Svartengren excerpted similes from the OED and Joseph Wright’s The English Dialect Dictionary. He also cited some explanations from Notes and Queries and a few other sources, but the origin of the similes did not concern him too much. The material is inexhaustible. My database of English phrases (however, I was interested only in the literature on etymology) hardly amounts to one thousandth of Svartengren’s corpus; yet it contains many similes not featured even in his work.

From Modern English Svartengren listed clean as a baby’s leg, clean as new preen, clean as print, clean as wheat, clean as a leek, clean as carrot, clean as a mackerel (or smelt), clean as a (new) penny, clean as a new pin, clean as a razor, clean as a pick, clean as a pink, and clean as a whistle. Obviously, some such phrases are occasional coinages (for instance, clean as a baby’s leg), and one can come across many more such in books (I have recently read the pronouncement of an old woman in a Russian story: “I was sitting there, clean as a doctor”). Some others have or had currency only in a limited area, but the ones in bold seem to be known widely, and Svartengren devoted considerable space to them. On the Internet, clean as a whistle has also attracted a good deal of attention. Below, I will only refer to the explanations that turned up in my reading (that is, why whistle, etc.).

In general, baby’s legs are not always clean.

In general, baby’s legs are not always clean.Svartengren’s book is a model of careful lexicography, but I did not find clean as a clock there. This case is instructive because it shows the difficulties of accounting for the comparandum. I am quoting from Notes and Queries, 5th series/I, 1874, p. 454: “As clean as a clock—A common phrase in Yorkshire, referring to the shining and clean-looking black-beetles (always called clocks in the North ), which are to be found under every piece of cow-dung which has been dropped a few hours.” We can probably assume that the explanation is correct, and it is easy to imagine what elaborate hypotheses etymologists ignorant of Yorkshire speech and the habits of black beetles would have offered for the origin of the idiom. The same questions should be and have been asked about pink (clean as a pink) and especially whistle: why are those particularly clean?

Clean as a clock.

Clean as a clock.For instance, it has been suggested that pink refers not to the flower but to the scarlet coats of foxhunters. But knowledgeable people refuted this idea: “…the generality of hunting men did not wear pink, but green, less than a hundred years ago [written in 1883]; indeed I have heard old-fashioned sportsmen declare that pink covered more cowards in the hunting fields than any other colour.” The author of the note voted for pink “flower,” which is “certainly as clean and fresh a looking flower as can well be met with.” But pink also designates the minnow. “As clean as this very common but very elegant fish would not form a bad simile.” It probably would not.

And now back to whistleblowers and their tools. “…if any flue, or other extraneous matter, gets into the narrow mouthpiece, the instrument becomes dumb. … But to this there is the obvious objection that the proverb applies to the act of cutting: he cut it through as clean as a whistle.” So the following should be taken into consideration: “If a strong and rapid cut is made with a sword, it will produce a whistling noise…” One is encouraged to heed the master’s advice: “Let me hear your blade whistle.” A clean cut is also said to be a common expression. Knowing nothing about swords except what I have read about them in medieval books and seen in museums, I find this etymology far-fetched. According to still another suggestion, clean in this simile means “clear”: “No sound is more clear than that of a whistle…. But if a man speaks of cutting anything off with perfect smoothness and evenness, he would say he has cut it off clear or sheer, or clean, with equal readiness, and he would probably add the words ‘as a whistle’ to one phrase quite as soon as to the other, without any great amount of reflection as to the congruity of his speech.”

A third suggestion has often been repeated. Allegedly, clean in our simile means “empty.” Thus, “when whale ships arrive in port after an unsuccessful fishing, they are reported as clean—they have brought no oil; they are empty.” More examples of clean “empty” follow, and the Scotch equivalent as toom’s a whistle, with toom meaning “empty,” is given. The writer was immediately rebuffed by a man from Darlington who pointed out in a rather aggressive tone that, although both toom and clean do mean “empty,” toom conveys a much more complete idea of emptiness than clean. So what? The laws of polemic never change. People are eager to show off and refer to irrelevant facts, only to demonstrate their sham superiority (in this case: “I am afraid that W. M. has still a good deal to learn of the nuances of the Scotch language”). But couldn’t whistle in the phrase under consideration be a mistake for whittle or whittal, or wittel “a butcher’s knife”? “Proverbs are often corrupted.” They certainy are (what isn’t?).

An ideal whistle blower.

An ideal whistle blower.The next note is especially revealing. “Any one who has witnessed the manufacture of a rustic whistle can be at no loss for the origin of this saying. A piece of young ash about four inches long and the thickness of a finger is hammered all over with the handle of a knife until the bark is disengaged from the wood and capable of being drawn off. A notch and a cut of [or?] two having been made in the stick, the cuticle is replaced and the instrument complete. When stripped of its covering, the dead wood with its colourless sap presents the cleanest appearance imaginable—the very acme of cleanness…. As clean as clean could not more effectually express the purity of condition than as clean as a whistle.”

The contributors to the discussion wrote letters to Notes and Queries in 1867 and 1868. The chronology deserves mention because the people who are curious about phrase origins routinely consult the most recent available books that tend to dispense with quoting their sources, except for other reference books (Brewer and others). As a result, etymology has become almost completely anonymous. But we can see that the answer requires strenuous efforts of many “non-anonymous” people. It was not my ambition to announce the derivation of the phrases I have discussed here, but only to provide some food for thought, as the saying goes. However, I think the Yorkshire man who touched on the simile clean as a clock did put his finger on it, even if in this case it was only a dung beetle.

Image credits: (1) Baby legs by Adina Voicu, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) Beetle by Zdeněk Chalupský, Public Domain via Pixabay (3) Clock by obpia30, Public Domain via Pixabay (4) Minneapolis Traffic Officer by Calebrw, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Dishes sink by Unsplash, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post As clean as what? appeared first on OUPblog.

Australia in three words, part 1-“Mateship”

“Mateship” is an Australianism – my American spell-checker doesn’t recognise it – and it’s one that captures something widely held to be distinctive about Australia.

Like many Australianisms, the word existed well before there were any Australians in the ordinary sense: it was a coinage of Elizabethan English. But the word long languished in apparent desuetude: the most exhaustive reader of the collected works of Dickens, Hardy, and Melville would never have encountered it. And it seems the European settlers of Australia had for a century no use of the word, either; it has been ventured that her colonial orators would never have heard of it.

It was in the 1890s that there was a surged sense of Australian identity, articulated most widely in the fiction of Henry Lawson. The word ‘mateship’ seemed to serve well one of the defining features of that identity: a highly developed sense of peerness; a magnification of the sphere of life that comprises the recognition of counterparts, compeers, and comrades. Every culture’s social weather map will include instances of this pressure system, but in Australia it seems to blow stronger and wider than many obvious comparator countries.

But the nature of mateship is easily mistaken.

Essentially masculine, there is, for all that, nothing ‘patriarchal’ about it. Quite the opposite. Mateship is brotherhood and a brotherhood is not family. Mateship has for this reason been implicated in Australia for being a ‘psychologically fatherless community’. A “matriduxy”, in fact. (Enter Dame Edna ….)

Cutting railway Sleepers, Woodside, Victoria, circa 1912 by Museum Victoria. Public Domain via Museum Victoria.

Cutting railway Sleepers, Woodside, Victoria, circa 1912 by Museum Victoria. Public Domain via Museum Victoria.Neither should mateship be confused by an impulse to associate, so often attributed the ‘nation of joiners’, the United States. That sort of civicness is born of ideals, and ideals are a weak current in Australian life.

Above all, mateship is not to be mistaken for a diffuse, philanthropic sociality; something for which Australians have no unusual predilection. (Cross-country surveys indicates the sympathy of the average Australian to asylum-seekers sits midway in the range of international opinion). And mateship cannot admit such a predilection: to grant everyone membership of your peer group is to have no peer group at all. Mateship, then, looks both inwards and outwards.

The ambiguity in the implications of mateship is illustrated in the revolutions in Australian attitudes towards Chinese and Aboriginals. The Australian Federation of 1901 was very much conceived as a Commonwealth of Mates. Mates were expected to be able to trace their descent from the British Isles – “the crimson thread of kinship” – and, certainly, were to be white. Two groups, then, were clearly not mates: Australia’s population of Chinese and Aboriginals. The new Federation promptly legislated to debar completely the immigration of non-whites; something Australia’s colonial parliaments of the preceding century had never done. And, complementing that, Aboriginals were swiftly made ineligible to vote; also something that largest parliaments of colonial Australia had never done.

Australia is now much changed. The Aboriginal flag flutters over just about every Australian school. Strenuous and unrelenting efforts – undiscouraged by any failure – are made to receive Aboriginals into the ordinary course of Australian life. The 2006 census revealed one utterly middle class Sydney district, that had been electing the conservative Prime Minister John Howard for 30 years, included a larger number of persons of Chinese and Korean birth and descent than English. The revolutions in policy towards Chinese and Aboriginal can be construed as persistence in this sense of peerness, combined with a revision in who will count as a peer.

Yet the strength of mateship has surely declined. There are some particular signs of this. Trade unionism, that always claimed an emotive foundation in labour camaraderie, has experienced a collapse in membership. 50 years ago there was no country larger than Australia that had a greater proportion of its workforce with union membership. That proportion is currently distinctly smaller than in the UK, and nearer that of the US than Canada. Beer drinking was always the popular and graphic Australian emblem of mateship – about half as much is drunk per head as 40 years ago.

The general hue of Australian life is also changing as one of its primary colours fades. Mateship never neatly chimed with political and intellectual authority. As its core energy was not an impulse to control, it was left unanimated by the exhortations and injunctions of those in control. Thus mateship – with its “sardonic humour” and nonchalant demeanour – constituted a humanizing force on Australian life. And if it never constituted an outright disposition for acceptance, it had the potential for it. For if it was impossible for everyone to be a mate, it was also true that it was possible for almost anyone to be a mate, by sufficient identification with the trials of the other. Indeed, the ethic seems not to have absolutely required a mate be a human being. Thus “Red Dog, The Pilbara Wanderer”, a kind of canine swagman of the 1970s, whose life has been told – in pastiche Lawson – by Louis de Bernières, and to whom a statue now stands in Western Australia, “erected by the many friends made during his travels.” With that unique sense of identifying with their owner’s estate, dogs found space in the mateship ethic; a truth epitomized by yet another dog statue, that fey piece of Australiana, “The Dog on the Tucker Box”, inspired by verse of the “bush troubadour” Jack Moses, a friend and stalwart of Lawson.

Australia is, indeed, now much changed. One member of Australia’s Senate recently called for “army snipers” (his term) to be stationed in national parks to dispose of household dogs who might stray within their boundaries. A keener, colder wind now blows.

Feature image credit: Storm clouds over Uluru by Ed McCulloch. CC-BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Australia in three words, part 1-“Mateship” appeared first on OUPblog.

Colombia: the embattled road to peace

Is absolute peace throughout a nation ever truly attainable and sustainable? Can a country ever unite as one entity in the face of extreme opposing views and ideals throughout the land, its people unable to achieve the plurality of a single bilateral, collective human interest legislative mandate?

As the country of Colombia celebrates its Independence Day on 20 July 2016, its people must also reflectively and introspectively ask these crucial questions. Simultaneously on this very day, Colombia is poised to finalize a peace agreement intended to end civil strife and human rights atrocities the country has endured over half a century, causing immeasurable violence, disenchantment, displacement and overall irreversible destruction. The nation is facing critical times that will undoubtedly leave an indelible mark on its history.

Colombia is a democratic republic, gaining self-governance from Spanish rule on 20 July 1810. Over a century later, in 1948, the assassination of Jorge Eliecer Gaitan, a prominent politician during his presidential campaign, stirred the nation and became a catalyst in the decade-long period of violent political unrest between the Conservative party and the Liberal party, that ensued throughout the country, referred to as La Violencia. Gaitan was not only a politician projected to become the next president of Colombia, he was the leader of the Liberal party, and perceived as the vital change and hope for the enduring socioeconomic disparity felt throughout the country.

The violence seen after his murder in the heart of the nation’s capital, Bogotá, was an expression of the frustration and anguish felt by an underrepresented people; thus, an even greater climate of disillusionment and neglect propagated by the government overpowered the nation, particularly in its rural areas. A man by the name of Manuel Marulanda Velez, alias “Tirofijo”(sureshot) became the leader of the community that established in Marquetalia, Tolima, in the Andean region of the country.

In 1964, in an effort to purge the country from what served as refuge for the communist guerillas and liberate the nation from these areas that had become a symbol of defiance and violence, Lieutenant Colonel José Joaquín Matallana led his troops into the region of Marquetalia; their sole purpose at all cost was of annihilating the perpetrators leading the insurgents. The troops led a treacherous journey through the countryside and eventually overtook Marquetalia by air.

Cease-fire agreement, Colombia by Presidencia El Salvador. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos (left) shakes hands with FARC Commander Timoleón Jiménez (right), after signing cease-fire agreement. President Raul Castro of Cuba observes the exchange. Public Domain CC0 1.0 via Flickr.

Cease-fire agreement, Colombia by Presidencia El Salvador. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos (left) shakes hands with FARC Commander Timoleón Jiménez (right), after signing cease-fire agreement. President Raul Castro of Cuba observes the exchange. Public Domain CC0 1.0 via Flickr.The country rejoiced after the battle and what was deemed a victory for the nation, actually led to the formal creation of The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), headed by “Tirofijo,” who managed to escape through a trail undetected by aerial observation during the conflict, along with other revolutionaries.

What began as a peasant Marxist-Leninist organization formed under an ideology based on the needs of the people and striving to create a climate of equality, has become Colombia’s largest guerrilla group, and since its creation, the FARC has terrorized the country, committing unfathomable crimes, forcing people into the organization, some as young as 9 years of age, and more than 220,000 people have died in the conflict.

Even with a peace treaty on the horizon, the country is still at odds, wondering if it will ever truly find peace, and at the same time torn by the notion of exonerating these militants who have caused such damage and destruction as a whole; the guerrillas, in turn, are faced with the obligation of integrating back into civilian life, surrendering their weapons, and many incorporating a life they have never known, but have only been exposed to war.

The notion of obtaining peace in a divided country also pertains to any established, autonomous region and it appears in recent events, many are continuously divided on major issues, as they face equally significant decisions. Theresa May has taken the role of prime minister in the United Kingdom, succeeding David Cameron, all the while the country is still recuperating from Brexit, and the divisive decision that startled the nation. In the United States, a presidential election awaits trial, amidst a sea of uncertainty and violence, in a country divided by race, politics, and inaction.

This, of course, is an oversimplification of complex underlying thematic issues that have been prevalent for many years, decades, almost centuries. For the sake of practicality, the summary of these issues serves as an effort to portray a correlation between countries that would otherwise seem unrelated, distant in geography, thought and circumstance. It is an attempt to show how nations, even while pertaining to one government under one set of specific, unequivocal rules, can still remain in discordance, and if not addressed timely and properly, can ultimately lead to self-destruction and indeterminable animosity.

Having been born and raised in Colombia, many of these concepts of war and struggle are as foreign to me as they may seem to someone with no knowledge of the country. My Colombia was one of tranquility, natural beauty, and exceptional education. The Colombia I know is characterized by acceptance and diversity. A place where there are as many beaches as there are mountains and skyscrapers, where the magnificent flora and fauna might be overlooked, as its abundance and beauty becomes commonplace.

Ultimately, just as I, along with countless others, were not directly affected by the struggles of the country, does not lessen the gravity of the situation or undermine the lives of the thousands that died prematurely because of it. Every nation has its deep-seated issues that cannot be whisked away, but rather addressed, head-on to attempt to alleviate the growing anger and disagreement arising from differences in class, race, social status, education, and gender. At what point do we realize that if one group suffers, we all suffer, being all one human race, and gain the courage to ask the ultimate question: can we all live in peace?

Featured image credit: Casa de Nariño by Miguel Olaya. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Colombia: the embattled road to peace appeared first on OUPblog.

July 19, 2016

Explaining citizenship, racism, and patriotism to the young

“Daddy,” my daughter started as we ate breakfast three weeks ago, “What’s Independence Day?”

“July Fourth, the anniversary of when the United States, our country, was founded.”

“The parade where they throw candy?”

“Yes.”

“Why do we wear red, white, and blue on Independence Day?”

“It’s a custom,” I told her. She has heard this term plenty of times, usually followed by society.

“Everyone else will be wearing it.”

“That’s right, and it’s fun.” And performing patriotism is an important skill to develop as a person of color, especially in a predominantly white state like Wisconsin. To indicate you’re a citizen.

“And they throw candy!” she cheered, then started to recount the process of collecting, gathering, and eating candy in simple terms put together in a way I barely understood. Her nouns and verbs stumbled over each other like sandal-clad feet dashing too far into the street for a Tootsie Pop. I nodded, “Uh-huh,” and returned to eating. I wondered if she was too young for this conversation, and remembered just how old she was. I wanted to clarify that it’s not that we were aspiring to be like the majority. Nor that we wanted to be the Model Minority, showing off our success in comparison to African Americans. These points would lead to a series of “whys” and my having to explain that we were vulnerable to prejudice, regardless. Acting all-American didn’t necessarily work for Muslim-looking shop owners who hung flags in their front windows after September 11. It didn’t necessarily work for Felix Longoria, or other minorities in uniform who returned (dead or alive) to the same racism they left. It didn’t work for Takao Ozawa, who believed that converting to Christianity, speaking English, and American schooling qualified him for citizenship. And it didn’t work for Homer Plessy, who made clear to that Louisiana train conductor that he was a colored person, and that he was a U.S. citizen. Through Henry Billings Brown’s majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court responded, “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences.”

On Independence Day we celebrate that our national, secular rhetoric has promised equality. But the authors of our founding documents qualified its applicability, especially when considering race. The Naturalization Act of 1790, the United States’ first law dictating who could achieve citizenship, stipulated that aliens must live in the country for two years, take an oath of support for the Constitution, possess a good character, and be a free white person. These criteria excluded indentured servants, slaves, free blacks, and American Indians. Women gained citizenship through their white fathers but, without property or the ability to vote, their status was secondary. This narrow conception of citizenship favored one segment of society. More important, it set a standard for future newcomers to attain or challenge.

Frederick Douglass as a young man. Engraved by J.C. Buttre from daguerretotyppe. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Frederick Douglass as a young man. Engraved by J.C. Buttre from daguerretotyppe. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The nation’s first census took place the same year, with local marshals surveying heads of households in the 13 states and the districts of Kentucky, Maine, Vermont, and Tennessee. The survey resulted in a population of nearly 3.9 million: 3,140,000 free whites, 694,000 slaves, and 59,000 free nonwhite people. Eighty percent of the nation was white. Our forefathers imagined that the country would remain so, and their decisions established a status quo in regard to race and citizenship. Because of their solipsism, whiteness, privilege, and citizenship bound to each other; white racial status was the fundamental requirement for citizenship, and non-whiteness meant subordination. For the most part, these definitions became standards for other groups who would encounter the American system until the McCarran-Walter Act began to eliminate racial barriers in 1952.

Can wearing red, white, and blue remind people they are not the only Americans? A dress with stars on top, stripes on bottom, and a big red bow lacks the words to explain this position. But hours of scouring the internet for shirts quoting Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Negro Is the Fourth of July?” produced nothing.

My daughter had stopped talking about candy by now, so I pounced on my opportunity to get some words in, “When someone tries to say you don’t belong, they’ll probably say you’re not really American. We wear patriotic gear to stop that conversation.” She looked me in the eye as my words followed each other like oxfords pacing the front of a lecture hall. They reached the edge of the stage and BASE jumped over everyone’s heads.

“Daddy, what’s patriotic?”

“A mixture of pride and dissatisfaction for your country.”

“But mostly pride?

“That’s right.” Class dismissed.

Featured image credit: USA flag by SnapwireSnaps. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Explaining citizenship, racism, and patriotism to the young appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten facts about the bass guitar

The bass guitar is often thought to be a poor musician’s double bass or a poor musician’s guitar. Nonetheless, luthiers and performers have explored its expressive possibilities within a wide range of musical styles and performance traditions, some of which we chart below.

1. With early versions appearing in the 1930s, the modern bass guitar was invented by Leo Fender and marketed beginning in 1951 as a cheaper, more portable, and louder alternative for double bassists playing in dance bands (Jamerson).

2. The bass guitar comes in two variants: the solid-body electric bass guitar and the hollow-body acoustic bass guitar. Both are traditionally tuned like a double bass, with the same four lowest strings (E’-A’-D-G) as a guitar, but an octave lower.

3. While the electric bass guitar is always amplified outside of personal practice settings, confusingly, the acoustic bass guitar can also be amplified electronically via pickups, usually in performance settings. The acoustic bass guitar is “acoustic” because its main amplification is its resonant, hollow body (Novoselic).

4. Both the electric and acoustic bass guitars originally and typically have fretted fingerboards, which enable ease of intonation. Fretless bass guitars enable swooping glissandi, which can approximate the sound of the double bass (DiGiorgio).

5. The bass guitar can be played with or without a plectrum (pick) (Lemmy, Kaye, Jackson). There are some ideological, as well as musical, differences: the pick more closely approximates the sound and style of the electric guitar, while the alternative—plucking the strings with the fingers—more closely approximates the sound of a double bass (Jamerson). For much of its history, the bass guitar was considered a poor musician’s double bass.

Bass Guitar. Photo by Feliciano Guimaraes. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bass Guitar. Photo by Feliciano Guimaraes. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.6. 5-, 6-, and even 10- and 12-string variants exist. While the 5-string version is often considered appropriate for rock and metal musicians seeking to extend the instrument lower than the electric guitar (and thereby creating an alternative bass part, rather than solely doubling the guitar part), the 6-string version is used primarily in jazz-rock fusion settings or in virtuoso work (Jackson). The 10- and 12-strings versions are usually considered curiosities, best used in solo work, or in bands that feature those instruments specifically.

7. Initially plucking or picking have been the primary means of creating sound on the instrument, but especially during the 1970s bass players started slapping the strings with the thumb (Clarke, Wooten); popping the strings by quickly pulling and releasing the strings with the index and middle fingers (Clarke); tapping on the strings with both or either hand; and even strumming the strings in a rasgueado style derived from flamenco guitar performance. Combining these techniques is considered a virtuoso achievement (Wooten).

8. The bass guitar enables a variety of approaches to performance: from “walking” bass lines derived from jazz; playing countermelodies or imitating the bass drum and snare parts of the drum set (Jamerson, Ndegeocello); to fully soloistic lines imitating or doubling saxophone or guitar lines (Pastorius, Wooten, Jackson); to “lead” bass guitar parts that at once solo and lay down a groove (Clarke, Ndegeocello, Roessler); to bass solos leading into doubling the guitar part, but an octave lower (Lemmy); to providing coloristic and percussive effects (DiGiorgio); and much else besides.

9. Because the electric guitar has often been considered the virtuoso instrument in male-dominated popular music, women’s contributions have often been relegated to playing the bass guitar. Despite this gendering, women have featured prominently as bassists, making important contributions in all genres—including soul, funk, hardcore punk, and doom metal—with all techniques, and expressing various subjectivities through the instrument (Ndegeocello, Kaye, Roessler, Slajh).

10. While primarily a popular music instrument, a number of composers writing in the concert tradition have included the bass guitar in their pieces (Schnittke).

Playlist

1. James Jamerson, “Standing in the Shadows of Love”

2. Krist Novoselic: “All Apologies”

3. Anthony Jackson: “Race With Devil On Spanish Highway”

4. Jaco Pastorius, “Donna Lee”

5. Stanley Clarke, “School Days”

6. Lemmy, “Ace of Spades”

7. Victor Lemonte Wooten: “The Sinister Minister”

8. Steve DiGiorgio, “Machines”

9. Meshell Ndegeocello, “Wild Night”

10. Carol Kaye: “Boogaloo”

11. Kira Roessler: “Your Last Affront”

12. Vanja Slajh: “Tree Of Suffocating Souls”

13. Alfred Schnittke: Symphony no. 1

Headline Image Credit: Person Playing Sun Burst Electric Bass Guitar in Bokeh Photography. CC0 Lisence via Pexels.

The post Ten facts about the bass guitar appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and UK company law

Most discussion relating to the referendum result has focussed on the effect that Brexit will have upon our constitutional arrangements or workers’ rights. This blog post will focus on the effect that Brexit will have upon the UK system of company law. Unfortunately, the current uncertainty regarding the terms on which the UK will leave the EU (if indeed it does) means that a definitive answer cannot be provided, but several principal possibilities can be advanced.

The UK could, despite the referendum result, decide to remain in the EU. There has been a notable backlash to the referendum result (and the method of campaigning prior to it) and it is unclear when the Art 50 notification will be triggered (indeed, a number of politicians appear keen to delay notification). If the UK does not leave, then clearly little will change. It should also be noted that, until the Art 50 procedure has been completed (irrespective of whether an agreement is reached), the UK will remain a Member State of the EU and will remain bound by EU law, both enacted and upcoming. So, for example, if the proposed EU Directive on Board Diversity is passed prior to the UK’s exit from the EU, the UK will technically remain bound to implement it, providing that the exit procedure under Art 50 has not been completed by the Directive’s implementation date.

The UK could leave the EU and not seek to participate in the single market. For obvious reasons, this is widely regarded as an extremely unattractive option

The UK could leave the EU, but retain participation in the single market, most likely through becoming a member of European Free Trade Association and then joining the European Economic Area (‘EEA’). Amongst those in favour of Brexit (and those who wish to remain, but reluctantly accept Brexit), this currently appears to be the most popular option. EEA Member States are subject to the EEA Agreement, which provides that EEA States remain bound by EU legislation relating to the four freedoms (namely goods, persons, services, and capital. As most company law directives apply to EEA states, the bulk of EU company law would still bind the UK. All told, a Brexit that involved EEA membership would not likely result in major changes to our system of company law. Of course, the disadvantage of the EEA route is that we would be bound by large sections of EU law and, whilst we could express opinions on proposed EU law reform, we would be unable to vote on such laws. For a country that has contributed so strongly to the development of EU law in financial areas, this will be a notable disadvantage.

The UK could leave the EU and not seek to participate in the single market. For obvious reasons, this is widely regarded as an extremely unattractive option, and it would potentially have the most impact upon our system of company law. The UK would no longer be bound by EU law, but the exact effect this would have upon UK law would depend upon the type of EU law in question:

EU Treaties are given legal effect under UK law by virtue of s 2(1) of the European Communities Act 1972. In the event of a Brexit that resulted in the UK not being bound in any way by EU law, the 1972 Act would either be repealed, or amended so as to provide that EU law is no longer supreme and Treaty provisions would no longer be binding.

Regulations are directly applicable and become part of UK law when passed, without the need for any further implementation. Regulations that have not been implemented via legislation would cease to apply to the UK. However, Parliament does occasionally enact Acts of Parliament or amends existing Acts in order to implement EU Regulations and such provisions will remain in effect until such time as Parliament decides to repeal, amend or replace them. Subordinate legislation made under the European Communities Act 1972 that implements EU Regulations (e.g. the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Market Abuse) Regulations 2016, which implements the Market Abuse Regulation) will be automatically revoked if the 1972 Act is repealed. However, instead of repeal, the 1972 Act could be amended to provide that such subordinate legislation will remain in effect, or the law could simply be enacted anew.

Directives must be implemented to have effect domestically (unless the implementation period has passed, in which case they can acquire vertical direct effect). Acts of Parliament that implement directives will remain in place until such time as Parliament decides to repeal, amend or replace them (e.g. Part 13, Chs 3 and 4 of the Companies Act 2006 which implement the Shareholder Rights Directive). Subordinate legislation made under the European Communities Act 1972 that implements EU directives (for example, the Statutory Auditors and Third Country Auditors Regulations 2016 were enacted primarily to implement the Statutory Audit Directive) will be automatically revoked if the 1972 Act is repealed. However, instead of repeal, the 1972 Act could be amended to provide that such subordinate legislation will remain in effect, or the law could simply be enacted anew.

The bulk of UK company law is not derived from the EU, meaning that a complete split from the EU with no participation in the single market would be likely to have notable effects in specific areas only, including the following.

UK companies that wished to merge with companies in EU states would find such mergers more difficult, as they would not be covered by the Cross-Border Mergers Directive

Perhaps the most notable impact would be to the UK’s Listing Regime, which has been strongly influenced by EU law. The Prospectus Rules implemented the Prospectus Regulation and the Prospectus Directive, and the Transparency Directive was implemented by the Disclosure and Transparency Rules. Parliament could simply decide to keep existing law in place, which would be a wise solution given the complexity of the law in this area and the desire to maintain the UK as a leading financial centre. Even if such laws were kept in place, EU law would continue to evolve meaning that, over time, EU law and domestic law could drift apart, which could have an effect upon the UK’s reputation as a leading financial centre. Currently, the Prospectus Directive allows companies with FCA-approved prospectuses to passport their prospectuses into other EEA states, which facilitates the listing of shares on multiple EU stock exchanges. If we were completely free of EU law, the UK would lose the ability to passport prospectuses in this way. Indeed, even the EEA option would result in a reduction in passporting rights.

The UK’s market abuse regime has been strongly influenced by EU law, notably the Market Abuse Regulation. Domestic laws that implement EU law in this area operate in order to maintain integrity in our financial markets and, as the UK is a leading financial centre, I would not expect the government to seek to amend these laws substantially, if at all.

Recently, the Statutory Audit Regulation and the Statutory Audit Directive were implemented in the UK by the Statutory Auditors and Third Country Auditors Regulations 2016. It seems unlikely that amending these rules post-Brexit would be a priority. What may change is that the FRC’s ability to influence EU policy would likely wane, and it would cease to be a member of the Committee of European Audit Oversight Bodies.

UK companies that wished to merge with companies in EU states would find such mergers more difficult, as they would not be covered by the Cross-Border Mergers Directive which, as the name suggests, serves to facilitate cross-border mergers between companies in differing EU Member States. A new framework would need to be created to allow UK companies to merge with companies in EU Member States.

The Takeover Directive was implemented in the UK by the City Code on Takeovers and Mergers. However, the Directive itself was heavily influenced by the pre-Directive version of the City Code, so notable changes in takeover regulation are not expected.

The Statute for a European Company allows for the creation of a European public limited liability company, known as the Societas Europaea (‘SE’). Should the UK leave the EU, then it is likely that UK companies that have adopted SE status would lose that status. In practice, this will not be a major issue as the SE has not been popular in the UK. At the time of writing, only 53 SEs are headquartered in the UK.

Insolvency law is largely domestic, but cross-border insolvency matters are largely regulated by the Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings. Cross-border insolvencies will become more complex as there will be jurisdictional issues to determine. Further, UK insolvency professionals (notably liquidators) will not be automatically recognised as competent in other Member States.

There are also practical differences worth noting, chief among them being that many multinational companies choose the UK (notably London) as their base of EU operations. A UK outside the EU and EEA is not such an attractive location for a company’s headquarters and companies, especially financial services companies, may choose to relocate their headquarters or move parts of their business to other EU States. Indeed, the Governor of the Bank of England warned as much, and a PWC report has contended that up to 100,000 financial services jobs could be lost by 2020 as a result of Brexit. The European Banking Authority, an independent EU Authority that regulates the banking sector and is based in London, is reportedly also preparing to relocate.

It cannot yet be predicted with certainty what the effect of Brexit will be on UK company law, as there is considerable uncertainty about what form Brexit will take, if indeed it happens at all. What can be stated is that it is difficult to envisage any company law-related benefits will result from the UK leaving the EU. Regulation in some areas might be reduced, but this will not be an adequate trade-off for the benefits that might be lost, especially if participation in the single market is reduced.

This post first appeared on the author’s own blog, Company Law and Governance.

Featured image credit: image used under Creative Commons CC0 licence. Image created by stux and downloaded from Pixabay.

The post Brexit and UK company law appeared first on OUPblog.

July 18, 2016

How to choose a medical school

Feeling confused? You’re not alone… Applying to medical school is like asking someone to marry you. This might seem like an exaggeration, however over your lifetime you will spend more hours working than you will spend awake with your life partner. Like marriage, being a doctor will change who you are, influence where you live, and affect what you can do. For the right person this can be a wonderful, life-affirming experience. Otherwise, divorce from a medical career can be messy, painful and upsetting.

Think you might have what it takes? Once you have decided to become a doctor, the next big decision is where to study. The years spent at medical school will be some of the most important of your life, as you acquire the necessary skills and knowledge, as well as developing professionally. The choice of medical school also greatly affects your chances of receiving an offer. So you’ll need to select medical schools that match your individual academic and non-academic skills.

Applicants commonly ask, “what is the best medical school?” To be honest, your choice will not make a huge difference to your professional career. Your knowledge, skills, and attitudes will depend much more on the amount of time you invest in the course than the institution you attend. Regardless of your school, you’ll be as free as anyone else to pursue the specialty of your choice. Choose institutions because *you* would thrive there, not because of preconceived notions of quality or status.

So how can you narrow down your options?

Here is a flow chart that, admittedly, grossly simplifies a complex thought process. But it should help to highlight some of the most important factors and the types of courses that embrace them. Medical schools have many subtle distinguishing factors though, so read up on them, and try to visit a few.

Image credit: An algorithm for choosing a type of medical school, from ‘So You Want to be a Doctor?‘ p. 95. Used with permission.

Image credit: An algorithm for choosing a type of medical school, from ‘So You Want to be a Doctor?‘ p. 95. Used with permission.The choices

Each medical school has its own character, and artificially grouping them inevitably leads to generalizations. For example, traditional Red Brick universities may sometimes teach a more modern ‘problem based learning’ (PBL) type of course. Others may lack a traditional course style – but adopt a classic collegiate structure. With this in mind, use the groupings as a guide to focusing on similar medical schools – but do make sure to visit, and find out more for yourself. Image Credit, Clockwise: ‘Carbon Fiber’ by ATM Depot. ‘Building’ by LenaSevcikova. ‘Wall’ by GregMontani. ‘Structure’ by Nebenbei. All CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit, Clockwise: ‘Carbon Fiber’ by ATM Depot. ‘Building’ by LenaSevcikova. ‘Wall’ by GregMontani. ‘Structure’ by Nebenbei. All CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Carbon fibre

Ultramodern problem-based learning courses. These are the marmite of medical schools – you either love them or hate them.

Plate glass

New, sensible, and made for the city, if somewhat commonplace. Campus- or city-based courses with a mixture of PBL and lectures.

Red bricks

These traditional tried and tested courses are likely to feature in your application. Lecture-based city courses with early clinical exposure and minimal PBL.

Stone

Established but a little stuffy; old academic (occasionally collegiate) courses with an emphasis on science.

So you’ve decided?

The next hurdle is, unfortunately – admissions tests. Most medical schools require an admission test to help identify the best candidates. You only get one chance to take each test each year, but with careful preparation it is possible to maximize your score.

The tests are very different from A-levels and appreciating this difference is the key to doing well. They do not test what you know; rather they test how well you can think under time pressure. To succeed, you must focus on answering lots of questions well rather than a few questions perfectly. Being familiar with the tests and refining your technique can make all the difference.

There are two main tests used by medical schools in the United Kingdom: the UK Clinical Aptitude Test (UKCAT) and the Biomedical Admissions Test (BMAT). The UKCAT has five sections: Verbal Reasoning, Quantitative Reasoning, Abstract Reasoning, Decision Analysis, and Non-Cognitive Analysis. The BMAT consists of three sections: Aptitude and Skills, Scientific Knowledge and Applications, and the Writing Task.

Feeling Nervous? Don’t be. Applying to medical school can be daunting, but doing your research, asking questions, and immersing yourself (as far as possible) in the culture of your profession will help endlessly. Blogs, books, periodicals, and TV shows will all aid a better understanding of the world you are going in to. Whichever medical school you end up at, like a good marriage – it’s not about finding the ‘perfect’ school – but finding the perfect imperfections for you!

Featured Image Credit: ‘Computer, Business, Typing’ by Unsplash. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How to choose a medical school appeared first on OUPblog.

Blowin’ in the wind

I am, I suppose, part of the “cognoscenti” in the area of social identity, social bias, and social justice. I’m a tenure-track assistant professor of social work, I’m a diversity, equity, and inclusion consultant, and I recently wrote a book on how to understand and overcome challenges associated with race.

In addition to my professional credentials, I navigate this world as an adversely racialized nominally black male, I’ve traversed and straddled extremely diverse racial, ethnic, religious, class, and cultural domains, and I crossed “the color line” and raised two children who represent defiance of the pernicious false binary of race.

But despite all of my knowledge and know-how, I find myself not quite sure what to do with a social justice challenge that currently confronts me.

Here’s the situation. Just down the street from where I live, in a wonderfully diverse and tolerant community, there is a house that I drive by on a regular basis from which hangs two flags, one being the flag of the United States of America, and the other being the flag of the Confederacy.

When I became aware of the Confederate flag flying just a stone’s throw from my house, I felt as anyone would who finds him or herself suddenly in the presence of a potential predator. Am I safe? Is my family safe?

After consulting with my family brain trust (composed of my wife and two grown kids) about what might be the best and safest way to approach this challenge (call the local media, knock on the door, draft a letter?), I determined that a letter would be the best way to go. Doing nothing was not an option.

So on 8 June 2016, I sent the note below to my Stars and Bars-flying neighbor. Who knows, I thought fantastically, maybe my words will be transformative, and the flag will disappear.

I had written in my note:

I’m reaching out to you in hope that you might be willing to talk with me about the Confederate flag that’s hanging from your home. It’s possible it’s been there a while, but I noticed it within the past week or so.

I try very hard not to jump to conclusions about why people feel as they feel, think as they think, and do as they do. I cannot know what the flag means to you or why you choose to fly it, but even in absence of this knowledge I feel obligated to express my distress and concern over this very charged symbol.

I am very aware of the origin and history and many perspectives that are associated with the flag. I know very well that many people see it as a symbol of heritage, pride, independence, and other positive things—and I don’t pretend to have the right or the power to change anyone’s mind about such things.

It is also the case, however, sadly but undeniably, that the flag represents a threat to many. No matter what it means to you (and I do hope we get to discuss that), it scares others and makes them feel less safe at home, less comfortable, less secure in their neighborhood.

When someone flies a flag of, say, another country (Canada, for example), we cannot know with certainty what the flag means to that person, but we can feel confident that the Canadian flag is not meant as a threat by the person flying it or felt to be a threat by anyone who sees it.

The Confederate flag is unavoidably burdened with causing dread and anxiety for many, many people, no matter what the intention is of the person flying it. That being the case, wouldn’t it be better to avoid the possibility of making folks feel bad, sad, or unsafe? Wouldn’t it be better to take it down?

Doing so would have nothing to do with your right to fly it. Instead it would be about your right to choose to do everything you can to help your neighbors feel a sense of belonging and safety in their home (dads and moms and sisters and brothers and kids who go to the schools that maybe your kids or grandkids go to, folks who repeatedly pass you aisle after aisle in the supermarket, and folks who maybe several times a day drive past your house).

I’m not into making people feel bad. I’m not into proving I’m absolutely right and others are absolutely wrong. I believe in and try my best to practice empathy, compassion, forgiveness, and humility. I think the hope of the world lives in the small chances we get to try to hear one another and make our little piece of the world as good and as safe a place as it can be.

Ten days later, the flag is still up, and I’ve received no contact from the flag flyer. Now what?

I am plagued by wondering what someone who was aware could have done to intervene when a flag was raised in the form of something said or done by the individuals who would someday fly into a murderous rage and slay twenty children and six adults in Newtown, nine parishioners in Charleston, and forty-nine young adults in Orlando. To be clear, I can’t know what’s in the heart, mind, and motives of my neighbor, but I see the flag, and it raises deep concerns. And I’m not sure what to do next.

There is a very real way in which the effects of seeing this flag on a regular basis are intimately personal—like a toxin released into the air that causes my eyes to burn and makes it hard for me to breath fully and freely. But I share this air with everyone in my community. And I wonder how this baleful banner is affecting my neighbors.

So I’m asking you: Are you aware? How are your eyes? How is your breathing? Did I approach this wrong? Would you have approached it differently? What would you do now? What should I do What should we do?

Featured image credit: Deep south by Richard Elzey. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Blowin’ in the wind appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers