Oxford University Press's Blog, page 487

July 18, 2016

Jewish identity – the Israeli paradoxes

Is Judaism a religion and a culture or is it also a nationality? To this question the Zionist movement, which led to the establishment of the State of Israel, gave a clear positive answer. This approach has been adopted by Israel.

The Israeli Declaration of Independence of 1948 states that the “Land of Israel, was the birthplace of the Jewish people… Here they first attained to statehood… and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.” The declaration further provides that it is “the natural right of the Jewish people” to have their own sovereign State, which “would open the gates of the homeland wide to every Jew.”

The promise was made good in the Law of Return enacted in 1950, which provides that: “Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an oleh [immigrant].” This legislation turned the question of who is a Jew into a legal one and led to extensive litigation.

“Every Jew has the right to come to this country as an oleh [immigrant].”

One of the most important cases was that of Benjamin Shalit, decided in 1970. Shalit, an IDF officer, married a non-Jewish woman. Under the halakhic orthodox rule their children could not be listed as of Jewish religion, given that their mother was not Jewish, but Shalit demanded that they be registered as being of Jewish nationality. The Interior Ministry maintained that the two went hand in hand; a person who was not of Jewish religion could not be of Jewish nationality.

The registration had no practical legal significance, but it was at the center of a profound ideological controversy. The Supreme Court, by a five-to-four decision, allowed Shalit’s petition and ordered the ministry to list the Shalit children as being of Jewish nationality.

The decision, which was strongly opposed by the National Religious Party, set off a public and political storm. Finally, a compromise was reached, and the law of Return and the Population Registry Law were amended in line with the orthodox halakhic standard that a Jew was “a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion”.

Nonreligious Jews received compensation for the adoption of the halakhic rule in the form of another provision according to which the rights of a Jew to immigrate to Israel and to acquire Israeli citizenship “are also vested in a child and a grandchild of a Jew, the spouse of a child of a Jew and the spouse of a grandchild of a Jew, except for a person who has been a Jew and has voluntarily changed his religion.” It was this provision that made possible, two decades later, the mass immigration of close to a million immigrants from the Soviet Union, many of whom were not Jewish by Orthodox standards but who nevertheless view themselves as Jews and Israelis.

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem by SarahTz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem by SarahTz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The legislative amendment also recognized the possibility, which was never disputed, that a non-Jew can join the Jewish people by conversion. But the question of what kind of conversion is required and whether it had to be an Orthodox conversion was left open.

Throughout Jewish history rabbinic courts have been the gatekeepers in this regard. Since Judaism has no central authority, a conversion authorized by one set of rabbis will not necessarily be recognized by others. Israel’s official rabbinical courts, who enjoy monopoly over marriage and divorce of Jews in Israel, are controlled by the Orthodox and Haredi communities. These courts have always refused categorically to accept conversions performed by Jewish movements they consider heretical, most notably the Conservative and Reform movements to which most affiliated American Jews belong. As far as Israel’s rabbinic courts are concerned, a person who undergoes Conservative or Reform conversion has, when it comes to marrying or divorcing in Israel, the status of a non-Jew. But is such a convert a Jew within the meaning of the legislation, which permits every Jew around the world to immigrate to Israel?

To this question the Supreme Court has consistently given a positive answer. Initially, the ruling applied to people who had undergone Conservative or Reform conversions overseas and afterward sought to immigrate to Israel. In these cases the Supreme Court ruled that, for the purposes of registration and the Law of the Return, the state must recognize conversions carried out in recognized Jewish communities in accordance with their accepted procedures.

A new stage was reached in 2005, in a suit brought by people who had immigrated to Israel from several countries and who commenced conversion procedures in Israel. They later chose to go overseas to undergo Reform or Conservative conversion, after which they returned to Israel. The Interior Ministry refused to recognize them as Jews. But the Supreme Court ruled by majority that their conversions, popularly referred to as “hop-over conversions,” should be recognized for the purpose of registration and the Law of Return.

A further step was recently taken. The Supreme Court has been petitioned by foreign workers and residents who have undergone conversion by private religious courts operating in Israel outside the official rabbinate. The Supreme Court dealt first with conversion done by private orthodox courts and held by majority that a person who came to Israel legally and undertook such conversion in good faith should be recognized as a Jew under the terms of the Law of Return. The issue regarding private conversions performed in Israel by Conservative or Reform Rabbis is still pending.

This leaves us with two paradoxes of the Israeli system. The one is that a person can be officially recognized as Jewish for the purpose of registration and the law of Return and yet considered non-Jewish by another official body, the Rabbinical courts, and thus not be able to get married in Israel.

The second paradox stems from the fact that Secular Zionism had never instituted its own procedure for acceptance into the Jewish people. Neither had the Israeli state done so—it remained dependent on religious bodies on this fundamental question relating to the right to immigrate to Israel. The key to entering the Jewish people and consequently also the State of Israel and receiving its citizenship is in the purview of divergent religious bodies who disagree with one another—some of which do not even recognize the state and over which Israel has no control.

Featured image credit: ‘Western Wall Plaza – Jerusalem Israel’. Photo by David King. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Jewish identity – the Israeli paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

July 17, 2016

Measuring sun exposure in outdoor workers

Sun exposure is a key feature of summer for many people, especially in countries like Canada where pleasant weather can seem so fleeting. Unfortunately, sun exposure (in particular ultraviolet radiation) is the primary cause of skin cancer, the most common cancer in Canada. Skin cancer is also one of few cancers where diagnoses are increasing. Some people are willing to take the risk in their leisure time, but for those who work primarily outdoors, choice is not an option. Consequently, outdoor workers have a much greater chance of getting skin cancer later in life. Outdoor work is very likely one of the reasons that men are at higher risk of skin cancer than women in Canada, given that men are employed in approximately 80% of outdoor jobs. This includes work in construction and farming industries, as well as building services, recreation, and the public service.

While cancers caused by a person’s work are taken seriously in general, skin cancer isn’t often thought of as an occupational disease. This is even the case in countries where workers can access compensation for a skin cancer diagnosis. This dichotomy may have something to do with the complicated relationship that we have with the sun; for example, outdoor workers often select their jobs because they like being outdoors and in the sun. Therefore, they may be more likely to blame this preference for the exposure they received at work and in their leisure time. In addition, there aren’t any formal exposure limits for sun exposure in Canada (nor in most countries). Perhaps most importantly though, outdoor workers often work in jobs that pose a more immediate risk to safety than a potential skin cancer diagnosis years in the future. Construction workers and their supervisors, for example, are more concerned about losing a finger or falling from a height than they are about a skin lesion.

Image credit: Working by Skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: Working by Skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Because of these considerations, until recently, there had never been any measurement of outdoor workers’ exposure to ultraviolet radiation in Canada. This is important for two reasons. Firstly, if we want to do something to reduce exposure to a carcinogen at work, we need to know what the levels workers are being exposed to; otherwise we have no way of evaluating the effectiveness of efforts to reduce that exposure. Secondly, when we don’t have objective measurements of an exposure, it hinders our ability to actually quantify the risk of that exposure. In skin cancer epidemiology, the only “measurement” of exposure is typically a self-reported estimate of how much time a person has spent outdoors on a typical day over their lifetime. Our estimates of skin cancer need better, more objective measures of exposure (at work and otherwise).

Recently, we shared exposure monitoring results from the Outdoor Workers Project, a study involving construction and horticultural workers in and around Vancouver, Canada. The results indicated that even in a location not typically considered risky from a sun exposure perspective, workers are at risk of skin cancer in the summer months. A person’s job title, age, and the weather forecast all contributed to higher sun exposure measurements; younger construction workers on sunnier days had the highest exposure levels. The mean exposure level was around one SED (standard erythemal dose, a typical measure of sun exposure), which puts fair-skinned individuals at risk of sunburn and subsequent cancer. The highest measurement in the study was 19 SED, a dangerous level of exposure for even darker-skinned workers.

As our summers continue to heat up and become drier and drier, the risk of sun exposure at work will continue to increase. Sun safety for outdoor workers will need to be a top priority. Many people living at higher latitudes (including Canada, but also much of northern Europe) need to protect themselves if they work primarily outdoors, and employers should be aware of their responsibility to protect their workers. Tips for employers and workers need to be practical, since we can’t eliminate sun exposure (nor would we want to)! The Sun Safety at Work Canada project is helping to enhance the capacity of workplaces to address this challenge. Going forward, we need more research on how to reduce the risk of skin cancer in outdoor workers, and we need to better quantify exposure levels by job type and location to improve skin cancer epidemiology overall.

Featured image credit: Construction by Skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Measuring sun exposure in outdoor workers appeared first on OUPblog.

The evolution of international criminal justice

In commemoration of International Criminal Justice Day, it is worth pausing to reflect on the evolution and impact of the field in just two decades. Of course the history goes back much further, and it remains painstakingly challenging to realize in many contexts, but it is without question that accountability is now a key feature of the global response to atrocity.

With the establishment of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 1993 and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1994, to the passage of the Rome Statute in 1998, major advances in the field have been made. These international courts paved the way for hybrid courts that brought international and domestic laws, judges, and lawyers together. Examples of these courts include the establishment of the Special Court for Sierra Leone in 2002 and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia in 2004. The field has evolved further with the move toward domestic prosecutions that have international support, such as the Bosnian War Crimes Chamber, which began work in 2005.

Building of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in Scheveningen, The Hague by Julian Nitzsche. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Building of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in Scheveningen, The Hague by Julian Nitzsche. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The move toward domestic processes is important. Given contexts with limited resources and high need, a focus on support for domestic decision-making and ownership about accountability priorities cannot be under-estimated. The related field of transitional justice can be helpful in this regard. Transitional justice — a field aimed at addressing a legacy of atrocity often through measures like trials, truth commissions, and reparations – has been imperfect in its support of the priorities of a population that has experienced abuse. But it has raised the profile to some degree on the need for accountability mechanisms that not only punish perpetrators, but also consider the needs of victims and communities affected by violence.

Advocates of international criminal justice must also take on the question of atrocity prevention. Although many rightfully argue for the need to set narrow expectations for justice mechanisms, we also know that the likelihood of a recurrence of violence in contexts that have experienced atrocity is high. This challenge requires prevention be at the forefront of the minds of those advocating for, designing, and implementing accountability processes, as well as other efforts undertaken in post-atrocity contexts.

Featured image credit: Justice by Jason Taellious. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The evolution of international criminal justice appeared first on OUPblog.

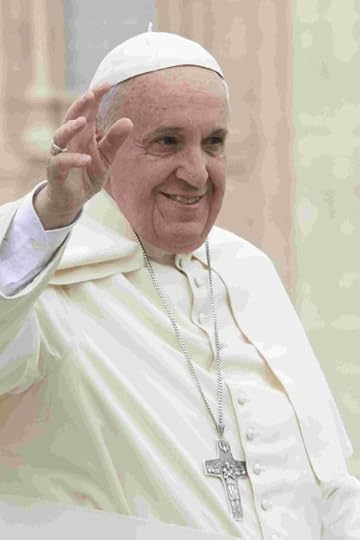

Ethical change in the Catholic Church

In just a little more than three years as the Bishop of Rome, Pope Francis appears to have disrupted what many thought was a straight and unchangeable course of moral teaching in the Catholic Church. Some of the more conservative members of the church are worried that the fundamentals of that teaching are being ignored, or worse, thrown overboard. Francis’s call for a ‘poorer’ church and a world that cares about the environment displays a significant turn in Catholic politics. But it is his frequent comments about personal and sexual morality that seem to upset people the most. Instead of talking about rules and behaviours, he has very clearly shifted the emphasis to people who find themselves in difficult situations.

While some are worried about these changes, others, like myself, are delighted that the reforms in moral theology called for in Vatican II are finally being allowed to take place. The last two documents of that council, Gaudium et spes and Dignitatis humanae, specifically avoided appeal to ‘natural law’ as a source for moral insight, something that both Humanae vitae and Veritatis Splendor attempted to reinstate. Both conciliar documents put forth respect for the human person and human dignity as the fundamental norm of morality. Although the Decree on Priestly Training, Optatam totius, specifically called for more input from scripture in teaching moral theology, hardly any hierarchical document issued under the last two pontificates made any attempt to carry out this recommendation.

Pope Francis recognizes that pre-conciliar moral theology was much too tied up with sins and the laws that were supposedly broken when a sin is committed. He has called attention to the spirit of the laws rather than the sometimes crushing letter of a law being imposed on persons who may not have the opportunity to live up to perfect standards. He appeals to the mercy that God shows to all of us and entreats us all to show mercy to each other. He is continuously looking for new visions to help define ethical living rather than new restrictions on human creativity.

In addressing the contemporary world, the area to which Francis is responding is actually at the level of ethics: how does one talk about morality in the first place? Pre-Vatican II (textbook) morality was about identifying sins that needed to be confessed in the sacrament of penance. It was developed by priest-confessors who taught future pre-confessors how to distinguish what constituted a sin. Their ethical method started with making a judgment about what they heard the penitent confess: what they did or failed to do. The process then moved on to considering any circumstances that might mitigate the guilt of the person, not necessarily the gravity of the sin itself. Finally, they might ask the penitent why they ever considered doing or omitting what they did: what were they attempting to accomplish? In schematic form:

action → circumstances → intention

Canonization 2014-The Canonization of Saint John XXIII and Saint John Paul II by Aleteia Image Department. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Canonization 2014-The Canonization of Saint John XXIII and Saint John Paul II by Aleteia Image Department. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The type of ethics that Francis is using first asks what people are attempting to accomplish. He recognizes that people won’t do anything if they are not motivated, so unearthing one’s motivation is of primary importance. When motivations are concretized, they are expressed as intentions. The next thing to consider is all of the circumstances within which persons find themselves. What is possible and what is not? What are the available tools or mechanisms at hand to accomplish one’s goals? Finally, it is only in light of all these factors that one can choose which course of action might be the most appropriate. In schematic form:

intention → circumstances → action

The change that has taken place in the way that Francis approaches moral issues is a change in ethical reflection. It is not simply substituting one set of rules for another. It consists in recognizing that why we do what we do is just as important as the course of action upon which we finally decide.

Textbook morality listed laws and rules that had to be followed without ever explaining where they came from or why they might be important. Addressing people’s motivations and encouraging them to think about what they are attempting to accomplish puts moral issues into an entirely new light. Whereas behaviours are addressed by laws, motivations and intentions are addressed by virtue and character ethics. The most pertinent question is: what kind of persons are we attempting to become and how can we build a community that encourages persons to adopt virtuous attitudes and motivations?

The task that the church now faces is reforming the way that it tries to teach people to deal with moral issues. Simply issuing condemnations or invoking a law is an inadequate way to deal with the complexity of people’s lives and the decisions that need to be made.

Featured image credit: The Vatican by Jeroen Bennink. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ethical change in the Catholic Church appeared first on OUPblog.

Transitions in transitional justice: reflections on International Criminal Justice Day

Today we commemorate International Criminal Justice Day to of the Rome Statute, the treaty that created the International Criminal Court (ICC), the world’s first permanent international war crimes tribunal. This year we should take the opportunity to reflect on various transitions in transitional justice. With the recent closure, creation, and consideration of several ad hoc war crimes tribunals, this year marks an unusual historical period.

Two ad hoc war crimes tribunals—the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) within the Senegalese courts—have recently concluded their trials. The significant institutional and legal precedents each tribunal set are worth enumerating. On November 8, 1994, the UN Security Council (UNSC) established the ICTR to prosecute individuals suspected of committing genocide and other egregious offenses in Rwanda as well as Rwandan citizens who allegedly perpetrated such crimes in neighboring states in 1994. The ICTR thus became the second-ever ad hoc court to be created by the UNSC after that body founded the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) the previous year. However, in contrast to the ICTY, as well as the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals, the ICTR was the first international court to exercise jurisdiction over atrocities committed during an internal conflict.

“This year has been significant not only for the concurrent conclusion to historic trials of multiple atrocity contexts but also because the Rome Statute approaches its adoption’s twentieth anniversary.”

In addition, the ICTR was the first tribunal to issue a legal finding of fact establishing genocide against Tutsi in 1994; to receive a guilty plea for genocide (from former Rwandan Prime Minister Jean Kambanda); to impose a genocide conviction on a man (Jean-Paul Akayesu, former mayor of Taba, Rwanda), a woman (Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, former Rwandan Minister of Family and Women’s Development), or a clergyman (Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, former head of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in western Rwanda); to codify rape in international law and hold that it can constitute genocide (in the Akayesu case, the subject of a new documentary, “The Uncondemned”); and to convict journalists of genocidal incitement (Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza and Ferdinand Nahimana, founders of the radio station Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines, and Hassan Ngeze, editor of the newspaper Kangura). On December 31, 2015, over 21 years after its creation, the ICTR closed and handed over remaining matters to the UN Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT). The MICT’s tasks include tracking and prosecuting remaining fugitives, conducting appeals and retrials, protecting victims and witnesses, supervising the enforcement of sentences, assisting national jurisdictions, and preserving and managing archives.

On January 30, 2013, the African Union (AU) and the government of Senegal jointly established the EAC to try international crimes committed in Chad between June 7, 1982, and December 1, 1990. A month and a half ago, on May 30, 2016, the EAC convicted Hissène Habré, Chad’s former president and the only person the EAC tried, of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, torture, rape, and sexual slavery. The Habré trial represents the first time a former head of state has been found guilty of rape or has been prosecuted (under the legal principle of universal jurisdiction) for human rights abuses in a country other than his own. The trial also reinforced the codification—and condemnation—of sexual and gender-based violence as violations of international criminal law. Last month, Habré’s lawyers appealed the verdict; the EAC plans to hear that argument in the near future.

This year has been significant not only for the concurrent conclusion to historic trials of multiple atrocity contexts but also because the Rome Statute approaches its adoption’s twentieth anniversary. On the one hand, the ICC is likely to assume even more prominence since the ICTR and the EAC have completed their trials. On the other hand, because of the ICC’s limited capacity as well as subject-matter, temporal, personal, and geographic jurisdictions, alternative transitional justice mechanisms will still be utilized. Indeed, just as the ICTR and the EAC have been winding up, new ad hoc war crimes tribunals have recently been created or at least considered, further indicating that the establishment of the world’s first permanent international war crimes court did not sate the international community’s appetite to continue proliferating such temporary tribunals. On April 22, 2015, the interim parliament of the Central African Republic (CAR) voted to establish a Special Criminal Court (SCC), a tribunal featuring domestic and foreign staff, to investigate serious crimes committed in CAR since 2003. The SCC is the first ad hoc “hybrid” war crimes tribunal to be created by a state government through national law to try serious crimes within its own country and to operate alongside the ICC, to which CAR referred the situation. Also last year, in September, the AU stated that an ad hoc hybrid war crimes tribunal would be established for South Sudan. The United States and the United Kingdom have pledged to support the AU’s efforts. Last year, as well, on August 4, the Kosovo parliament approved the creation of a court, the Kosovo Relocated Specialist Judicial Institution (KRSJI), to try members of the Kosovo Liberation Army for serious crimes they allegedly committed in 1999 to 2000 against ethnic minorities and political opponents. This ad hoc hybrid war crimes court, which will be staffed by international judges but created under Kosovo law, will be established in The Hague later this year and financed by the European Union.

The achievements of the ICTR and the EAC—which likely include inspiring the creation of the KRSJI and the SCC as well as the proposed tribunal for South Sudan—have not been flawless. Critics of the ICTR, for example, have charged that it was plagued by nepotism, mismanagement, incompetence, inefficiency, waste, insensitive treatment of witnesses, bias, and ineffective outreach to Rwandans. The full legacies of these tribunals—along with the ICC, the KRSJI, the SCC, and, if it comes to fruition, the court for South Sudan—will become clearer in the years and decades ahead. In the meantime, as we commemorate another International Criminal Justice Day, and as atrocities rage from Syria and South Sudan to Burma and Burundi, we should pause to consider how far we have come, and how much further we have yet to go, in achieving justice for the world’s worst crimes.

Featured image credit: The scales of justice, by James Cridland. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Transitions in transitional justice: reflections on International Criminal Justice Day appeared first on OUPblog.

The obscure objects of mass production

The objects of mass production – screws, nails, cell phones, cars – are everywhere. They are, for the most part, humdrum and insignificant and beneath the notice of philosophers. But in fact, I shall suggest, they are deeply mysterious from an ontological point of view.

Here is something that actually happened this morning, I folded a piece of origami paper (square and uniformly coloured) in a complicated way, made a single cut across the result, and ended up with two paper decorations. As I made the cut, one of them fell to my left – decoration A. The other fell to my right – decoration B.

But suppose, hypothetically, that the piece of paper I grabbed had been put into the packet the other way round, rotated by 180˚. I would have grabbed the same piece and gone through the same process of folding and cutting. One decoration would have fallen to my left, one to my right. Would I have produced the same two decorations I in fact produced, namely A and B? And, supposing the answer to this is “yes” (as I think it is) would I have made A on the right and B on the left? Or would A still have been the one on the left, but now made out of the paper B was actually made out of (and vice versa)? What is so strange is that there is no determinate answer to these questions.

Many philosophers, following the lead of Saul Kripke, think that it is essential to an object’s being the very object that it is that it be made out of whatever matter it is actually made out of. On such a view, we can never truly say “that object might have been made out of different matter.” At most, another object just like it might have been made out of different matter. Let us call this the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter. If the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter is true, it is essential to A, the decoration that fell to my left, that it have been made out of the bit of the piece of paper it was actually made out of. So, when we consider the hypothetical alternative in which the paper I grab is rotated by 180˚, the decoration that falls to my left cannot be A – it is not made out of the paper which it is essential that A be made out of. In that hypothetical alternative, the decoration that falls to my right is made out of that bit of paper. That doesn’t yet establish that it is A, though, because there might be other things essential to being A that it lacks. But at least it meets the necessary condition for being A, so if we embrace the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter we might well want to say that in the hypothetical situation, I do make A and B, but that A ends up on my right and B on my left.

Should we accept the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter? It is a very commonly held principle but here is an example that I hope will give you pause. Suppose I am casting a small metal object, perhaps a silver bullet with which to kill a werewolf. I melt some silver in a pan, more than enough for the one bullet I am making, and pour off some into a bullet mold. I make the bullet out of a certain sub-portion of the molten silver. But surely I might have made the very same bullet if instead a different sub-portion of the silver had issued from the pan. Can I not truly say, holding up the bullet I have made: “This very bullet might have been made out of different silver”? It seems as if which silver happens to run out of the pan first is irrelevant to the identity of the bullet I make. What, then, does fix the identity of the bullet? How would things have to be different, in a hypothetical scenario, for us to say that in those circumstances, I would have made a numerically different bullet, albeit indistinguishable from the one I do make?

Nails by cocoparisienne. Public domain via Pixabay.

Nails by cocoparisienne. Public domain via Pixabay.My own view is that what is essential to the bullet, and in general to the things we make, is not the identity of the matter they are made from, but the identity of the actions by which they are made. If the hypothetical bullet-making scenario involves the same action on my part, then it produces the same bullet, regardless of whether the silver is the same or not. And the reason for this is that an artifact like a bullet or a paper decoration isn’t just some silver or paper, arranged in a particular way. Such things are externalizations of the intentions and wills of their makers. What is important about them is their origins in the acts by which they are made, not their origins in the matter that makers resort to in order to express themselves.

But if this is correct, the case of the paper decorations poses a curious and interesting challenge. In that case, a single act of making is associated with two objects of the same kind. In the hypothetical alternative in which the paper is rotated, we surely have the same act as the act I actually performed. The only difference was the orientation of the piece of paper. But nothing about the act can help us answer whether, in the hypothetical case, I have made A on the right instead of on the left, or whether I have made A out of B’s actual paper, and B out of A’s. One might think that such cases will drive us towards accepting the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter. With it, we can at least say definitively, in the hypothetical case, that the decoration on my left is not A. Without it, we are unable to say definitively of either of the decorations that it is or is not A.

Strange as these consequences are, if we accept my view about artifacts as externalizations of their makers and reject the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter, I think we should embrace them enthusiastically. Think now, not of two paper decorations made by hand, but thousands of metal screws produced by a single human action in a factory. To insist of each such screw that it has its own essence, tied to the matter that it happens to be made out of, seems to make too much of it. With one pull of a lever, I produce a thousand screws. If, hypothetically, the metal had run out differently into the molds, I would have produced those very same thousand screws. But it is absurd to think we should expect to be able to say, of this hypothetical situation, that in it, the screw that ends up in slot 186 of the mold is the screw that actually ended up in slot 942 (even assuming that in the hypothetical situation, all and only the steel that actually went into slot 186 goes into slot 942). The thousand screws produced by my single action don’t have that much individuality to them! Rejecting the Necessity of Origin-as-Matter, I contend, gets us closer to understanding the nature of mass produced objects, strange and indeterminate as that nature may be.

Featured image: Car by niekverlaan. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The obscure objects of mass production appeared first on OUPblog.

July 16, 2016

Westminster professor takes home law teaching prize

Professor Lisa Webley of the University of Westminster has been named Law Teacher of the Year 2016, fending off strong competition from lecturers from Bangor, Leicester, Nottingham Trent, Oxford, and Sheffield Hallam.

The prestigious national award, which is sponsored by Oxford University Press, was presented at the end of the inaugural Celebrating Excellence in Law Teaching conference held in Oxford on Friday 1 July 2016.

Lisa is Professor of Empirical Legal Studies at Westminster Law School, and particularly impressed the judges with the way she weaves skills education into her teaching.

The six finalists shared a stage during a panel session at the conference attended by over 70 law academics, to explain their differing approaches to teaching and give delegates the chance to see exactly why they were nominated.

Accepting the award, Lisa said “this has been a wonderful opportunity to reflect on why we [teachers] do what we do, what we want to achieve, and what we stand for”. She also gave a special thanks to her colleagues and the Head at Westminster Law School for their openness to experimentation and creativity in teaching.

The five other finalists were:

Jo Boylan-Kemp, Nottingham Trent University

Steve Evans, University of Leicester

Lucinda Ferguson, University of Oxford

Yvonne McDermott Rees, Bangor University

Jennifer Sloan, Sheffield Hallam University

Judge Alison Bone

discusses the Teaching Excellence Framework

Delegates during a content session

Judge Alastair Hudson

chairs an afternoon session

Jo Boylan-Kemp

Nottingham Trent University

Participants from the student panel

with previous winner Jane Holder

Steve Evans

University of Leicester

Lucinda Ferguson

University of Oxford

The finalists' panel

moderated by 2014 winner Luke Mason

Yvonne McDermott Rees

Bangor University

Judge Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos

asks a final question of all six finalists

Jennifer Sloan

Sheffield Hallam University

Lisa Webley

University of Westminster

2015 winner Jane Holder

prepares to announce the 2016 Law Teacher of the Year

Jane Holder

congratulates winner Lisa Webley moments after the announcement

A round of applause

for Lisa Webley

The six finalists

L-R: Jo Boylan-Kemp, Steve Evans, Lisa Webley, Jennifer Sloan, Lucinda Ferguson, Yvonne McDermott Rees

Lisa Webley

Winner of the 2016 Law Teacher of the Year Award

All images by Simon Halliday for Oxford University Press. Used with permission.

The post Westminster professor takes home law teaching prize appeared first on OUPblog.

The Enlightenment and visual impairment

Blindness is a recurrent image in Enlightenment rhetoric. It is used in a political context to indicate a lack of awareness, seen in a letter from Edmund Burke to the chevalier de La Bintinnaye, in poetic rhetoric, with the stories of the blind poets Milton, Homer, and Ossian circulating among the intelligentsia of the time, or simply as a physical irritation, when writers with long lives and extensive correspondences frequently complained of their eyesight deteriorating.

The reception of those with total blindness, however, changed during the course of the long eighteenth century. The experiences of three people (acknowledged as blind) serves to show the ways Enlightenment thinkers, and eighteenth century society in general, responded to those who were rendered separate by their blindness.

The first is John Vermaasen, who plays a small but fascinating role in the evolution of Enlightenment epistemology, appearing as a living thought experiment in Robert Boyle’s Experiments and Considerations Touching Colours (1665). An organist, Vermaasen was blind from the age of two. He came to the attention of Robert Boyle when it was discovered that he had what may be considered a case of synaesthesia; he was able (allegedly) to experience colours using his sense of touch. When presented with a selection of coloured ribbons, and asked to give their colour, Vermaasen would “place them betwixt the Thumb and the Fore-finger…his most exquisite perception was in his Thumb, and much better in the right Thumb than in the left” (Robert Boyle, Experiments, p. 45) and then describe the colours to Boyle and his companion, determining them on the basis of the asperity, or roughness, of the material. Boyle was also sent another anecdote about an encounter with Vermaasen by Henry Oldenburg, in 1665.

Boyle would go on to use this experiment to hypothesise a continuity between the experiences of the five senses, a concept that would have a profound impact on the investigation into the nature of empiricism conducted by figures such as David Hume, George Berkeley, and the French Philosophes in the eighteenth century, most notably Denis Diderot, who in 1749 would write his Letter on the Blind, advancing a theory of education for the blind based on these principles.

A less endearing postscript to this story comes from Jonathan Swift, who included a possible reference to Vermaasen in Gulliver’s Travels (1726), as part of his satirical portrait of the Royal Society in the academy of Lagado (Bk. III: Ch.5), implying that Swift, at least, didn’t believe a word of Boyle’s story:

“There was a man born blind, who had several apprentices in his own condition: their employment was to mix colours for painters, which their master taught them to distinguish, by feeling and smelling. It was indeed my misfortune to find them at that time not very perfect in their lessons, and the professor himself happened to be generally mistaken. This artist is much encouraged and esteemed by the whole fraternity.”

— Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels, Bk. III: Ch.5

We can see the identity of Vermaasen being torn between the theoretical implications of his synaesthesia and his own playful means of adapting that synaesthesia into a self-representation of his own. Ultimately though, as far as we can tell, his blindness does not appear to have damaged his professional or social life. It was transcended by the unique and philosophically interesting sensory experiences he had in place of sight.

Thomas Blacklock (1721-1791), nineteenth-century engraving based on eighteenth-century painting. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Thomas Blacklock (1721-1791), nineteenth-century engraving based on eighteenth-century painting. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The same cannot be said for the second of our cases, however: Thomas Blacklock. Blacklock was a Scottish poet and clergyman who lost his sight to smallpox in infancy, but went on to become an advocate and pioneer of unique educational techniques for the blind. In 1760, he was nominated to the ministry of Kirkcudbright, only to find his potential congregation turned against him because of his blindness, creating an environment so toxic that his ordination was delayed until 1762, and he was only able to hold the position for three years, before resigning in 1765.

Blacklock’s understandable outrage at this rejection manifested itself in a satirical poem which he wrote in 1765, but which remained unpublished until 1903, so damning was it of the members of his congregation who had rejected him, out of nothing more than a prejudice against his blindness. This satire, called ‘Pistapolis’, is filled with evocations of the aural nature of sermonizing, highlighting the degree to which sight is irrelevant. A typical stanza runs as follows, addressing the poetic Muse:

“…if in thy view their procession should pass,

Though thy Tongue were of Iron, and thy Lungs were of brass,

To praise them in strains, like thy subject refin’d,

Were to p—ss in the ocean, or f—rt at the wind.”

— ‘Pistapolis’, (1765), unpub.

Though he was clearly embittered by his experiences, Blacklock went on to re-invent himself under the patronage of the poet and essayist James Beattie, becoming an expert on Scottish musical culture at Marischal College, Aberdeen, again exploiting his finely tuned ear.

In the case of Blacklock, we can see the liberating potential in the Enlightenment, particularly in Scotland. Blacklock was able to realize his secular, religious, and pedagogical potential by turning to the figures of the Scottish Enlightenment like James Beattie. He was able to move towards improving society for those marginalized like himself through a programme of pedagogy and publication, an early form of disability rights activist.

Later in the eighteenth century support for the blind became institutionalized. However, this also had its limitations. Anna Williams (our third case) was a Welsh poet who lost her sight later in life, and was given an annuity to support her by the bluestocking socialite and Shakespeare critic Elizabeth Montagu. In a letter of thanks, Williams says:

“I may with truth say I have not words to express my Gratitude as I ought, to a Lady whose bounty has by one act of benevolence doubled my Income, & whose tender Compassionate assurances, has removed the future anxiety of trusting to Chance, the terror of which only Could have prompted me to stand a publick Candidate for Mr Hetheringtons Bounty.”

Elizabeth Montagu, mezzotint engraving, by John Raphael Smith, after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, published 10 April 1776. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Elizabeth Montagu, mezzotint engraving, by John Raphael Smith, after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, published 10 April 1776. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It is the reference to Hetherington’s Bounty which is particularly significant here. This was an annuity of £10, to be given to one of 50 blind people “objects of charity, not being beggars, nor receiving alms from the parish” (London Evening Post, March 29, 1774–March 31, 1774) from a bequest of £20,000 given by Hetherington to Christ Church Hospital. While Hetherington’s intentions were praised as noble, the extent to which his charitable donations were able to ameliorate the conditions of those both poor and blind in London as a whole was called into question.

The celebrated philanthropist Jonas Hanway quantified the blind poor of the metropolis, organizing them into categories based on age and ability to sustain themselves. Hanway finds that the poor urban blind in need of Hetherington’s bequest amounted to over 600, concluding that “we must turn our thoughts to a more practicable mode, distinguishing the most distressed, and appealing to the most affluent and charitable” (Jonas Hanway, Defects, p. 262).

Anna Williams is clearly aware of the excessive demand being placed on the Hetherington annuity, as well as its informal process of deciding who was a valid candidate, claiming that submitting to it would be “trusting to Chance”, making it little more than a lottery.

Thus we can see, in these three stories, the ways in which those recognized as blind responded to the changes in society within their own communities and times across the period of the Enlightenment. Vermaasen recognized the public and philosophical potential of his unique sensory gift, and exploited it to build an identity in the early Enlightenment scientific drive to investigate and elucidate the strange or unknown of the previous generation. Blacklock saw the potential in new secular power structures developing in the universities and formal or informal circles of intellectual patronage to develop a political and pedagogical identity outside of the church. Williams, while herself benefitting from the informal patronage of the eighteenth century social network, was witness to the burgeoning impersonal, “telescopic philanthropy”, which would become a standard model of Victorian social enterprise.

A different version of this blog post appeared on Electronic Enlightenment.

Featured image credit: ‘The Dark Streets Of Bokeh’ by A Guy Taking Pictures. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Enlightenment and visual impairment appeared first on OUPblog.

July 15, 2016

Oral history and social justice

The #OHMATakeover of the OHR blog continues as Sara Loose explains her origins in oral history and how the skills and perspectives she gained at Columbia have influenced her career so far. Stay tuned to the OHR blog throughout the month of July for additional pieces from OHMA students and alumni, and come back in August for a return to our regularly scheduled program. For more from Columbia’s oral history program, visit them online or follow their blog.

How did you become interested in oral history?

I conducted my first oral history with a U.S. Catholic bishop who had been active in the Salvadoran solidarity movement in the 1980s for an undergraduate history paper. But I really fell in love with the power and practice of the field when I moved to El Salvador in 2001 to coordinate a multi-year, participatory oral history project exploring one rural community’s experiences in popular education during the country’s civil war.

How did you hear about OHMA?

After a long stint working as a community organizer and popular educator in the Pacific Northwest, I was eager to more fully integrate oral history into my organizing practice and further develop my skills as an interviewer. I found OHMA through an internet search!

Tell us a little about your master’s thesis.

In 2011, I organized a two-day gathering of some fifteen activist oral historians to share our experiences and explore the possibilities of oral history as a method for movement building and social change. Eventually, that gathering grew into Groundswell, now a national network of over 600 oral historians, activists, cultural workers, organizers, and documentary artists who work at the intersections of oral history and social justice.

Please share one experience from OHMA you find to be particularly memorable.

I relished the quiet, early mornings sitting in a rocking chair in my Washington Heights apartment, listening to interviews and doing course readings—and then rushing off from a thought-provoking class discussion on interviewing ethics to catch a bus to the suburbs of D.C. to convivir and do another round of interviews with Salvadoran immigrants who had come from the community I had worked with there a decade earlier.

Describe your current job and tell us how you came to it.

Currently, I co-direct Amamantar y Migrar, an oral history/organizing project exploring the connections between motherhood and migration and, more specifically, the impacts of immigration policy and enforcement on breastfeeding practices among immigrant women. I also serve as the co-coordinator for the Groundswell network, together with Amaka Okechukwu.

How are you applying oral history approaches to your work?

In our project, oral history interviews with immigrant parents serve as the basis for collective analysis to surface barriers that immigrant mothers face in exercising their autonomy in infant-feeding decisions and their potential solutions. From there, we are engaging project narrators in the creation of oral history-based media to share their stories and analysis via forums designed to support grassroots organizing, shift policy, and enact systems change.

What oral history projects have you worked on since graduating OHMA?

Rural Organizing Voices is the other major oral history initiative I’ve directed since graduating from OHMA. The project documents and shares the stories, organizing tools, and wisdom amassed through the Rural Organizing Project’s (ROP) history of grassroots, progressive organizing in rural and small town Oregon. Over the course of four years, I worked with a small group of volunteers to record nearly fifty oral history interviews with former and current ROP affiliates.

How do you think your year in OHMA has influenced your life and contributed to your career path?

OHMA provided me with an important theoretical foundation and the opportunity to refine my skills as an interviewer. It also established connections to a broader community of oral history practitioners that has helped ground and propel me forward as I map out a new path for myself and my work as a movement oral historian.

What is one thing you think would be helpful for current or prospective students to hear from someone working in your field?

In this emerging field of applied oral history, risk-taking and innovation are central. OHMA is a great place to experiment with new ideas with some solid institutional support and resources behind you.

How do you think the field of oral history will continue to develop?

My hope is that the field will build on its radical foundations to create even more dynamic opportunities for individuals and communities to preserve, share, and interpret their own histories, in ways that actively further the collective liberation of all peoples.

Add your voice the conversation by chiming into the discussion in the comments below, or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Photograph of Butler Library, Columbia University’s largest single library.” by JSquish, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oral history and social justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Masculinity, misogyny, and presidential image-making in the US and Russia

Masculinity is a characteristic that many people associate with political legitimacy; we expect politicians to be “strong” and to “protect” the country’s citizens and national interests. Politicians (male and female) thus make an effort to demonstrate their strength and toughness on various issues. But masculinity can also be used as a tool to undermine the perceived legitimacy of opponents. This trope is exhibited in the politics of many states. We can see it in play in the current presidential race in the US; for example, when a presidential candidate or his/her supporters question their opponents’ masculinity (suggesting they’re insufficiently manly). Donald Trump’s repeated suggestion that Jeb Bush was “low energy” and his use of the “little Marco” moniker to refer to Marco Rubio embody this notion. So did Marco Rubio’s remark that Donald Trump had “small hands” and his suggestion that Trump’s demand for a full-length mirror during a break in the CNN debate in late February was spurred by the desire to make sure his pants weren’t wet. Efforts to undermine an opponent’s masculine image can also come out in homophobic or misogynistic terms, such as a Donald Trump supporter in New Hampshire referring to Ted Cruz as a “pussy” when Cruz refused to wholeheartedly endorse the use of waterboarding. Witness to a variety of then-presidential candidates making fun of the ostensibly effeminate boots that Rubio received from his wife for Christmas (this teasing reportedly then pushing Rubio to fondle guns and talk football in public).

Male candidates are also affected by claims that the women affiliated with them aren’t doing femininity or womanliness “correctly” — meaning that the women on their side aren’t sufficiently attractive, or that they’re accused of violating a sexual norm, usually by being “slutty” or “cheap.” This is an indirect way of trying to undermine the male politician associated with the woman or women in question. Trump’s reference to Carly Fiorina’s face, or his supporters’ tweeting photos comparing images of Melania Trump and Heidi Cruz fit in the first part of this category. In the latter case, the argument is, “Mine’s hotter than yours,” and the implication is that a male politician’s masculine credibility and status can hinge on the sexual attractiveness of the women on his team. The Facebook advertisement aimed at Mormon voters and posted by Ted Cruz’s SUPERPAC that featured a nude photo of Melania Trump, saying, “Meet Melania Trump. Your Next First Lady — Or, You Could Support Ted Cruz on Tuesday” (in the primary) is an example of the second technique, the message being – in this case – Don’t vote for Donald Trump, because his wife is a slut.

Along similar lines, female candidates can be targeted as insufficiently manly. Donald Trump’s repeated labeling of Hillary Clinton as “weak” is the most straightforward example. Women running for office can also be reduced to sex objects who don’t deserve to be taken seriously as politicians. For instance, Bob Sutton, the Chair of the Broward County, Florida, GOP, stated in late April that when Hillary Clinton debates Donald Trump, “she’s going to go down like Monica Lewinsky.” Female candidates’ proper femininity or heterosexuality can also be questioned as a means of undermining their legitimacy. An example of this was a statement Carly Fiorina made early in the race, aimed at Hillary Clinton: “Unlike another woman in this race, I actually love spending time with my husband.” And like male politicians whose legitimacy can be undermined by their female partners’ supposedly improper behavior as women, so too can female politicians be criticized for their husbands’ alleged deviance from the norm. Donald Trump and Sean Hannity’s efforts to paint Bill Clinton as a rapist and abuser of women are intended indirectly to impugn Hillary Clinton’s character as a potential presidential candidate. By saying that her husband has gone overboard in his interactions with women, they suggest that he’s not doing masculinity correctly, and that this behavior reflects badly on Hillary, making her unfit for the presidency.

Male symbol silhouette by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

Male symbol silhouette by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.The prevailing means of asserting political legitimacy by means of masculinity, of course, is the assertion of strength and toughness, both of which are qualities typically associated with manliness. This is common across geographic areas and types of political regimes, from dictatorships to democracies. In the current presidential election, a number of commentators have drawn the “masculinity” parallel between Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin, both known for their “shoot from the hip” style and occasionally crude remarks.

Masculinity in these senses has been a key component of the image-crafting in Donald Trump’s campaign and Putin’s presidency. The plethora of images in the media where Putin’s masculinity is on display are well known. Whether he is saving a TV camera crew from a Siberian tiger, taking a shirtless fishing trip in Tuva, or fighting fires outside Moscow from a helicopter, Putin’s manliness was stressed as part of his image as a strong leader who would protect Russia’s national interests at home and abroad, regardless of any Western governments’ objections. Putin’s masculine image also came out in his choices of words, which early on emphasized his toughness. Following the brutal apartment bombings in Russia in September 1999, which served as one impetus to renew the war in Chechnya, Putin (who was Russian Prime Minister at the time) made it clear that the terrorists would be found and “wasted” wherever they were discovered, even in their “outhouses.”

In the US, while Donald Trump has not been pictured shirtless, he has become known for talking “tough,” such as in his comments against Mexico and Mexican immigrants in his presidential announcement speech in June 2015, saying that he would build a wall to keep out Mexican drug criminals and rapists, and that he would force Mexico to pay for it. Sometimes his endorsement of violence has been more direct, such as when he encouraged his supporters to use violence against anti-Trump protesters, saying at a rally in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in February – “if you see somebody getting ready to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of them, would you?” and then promising to pay any legal fees that resulted. Both Trump and Putin have projected a “tough guy” masculine image, and in both cases, found mainstream media and social media sources eager to promote it.

Image-crafting with regard to masculinity, then, may entail displays of muscles or bravery, or of tough talk in addition to (or in lieu of) either one. As we have seen, masculinity is also a weapon to use against opponents, visible when a president or presidential candidate or their supporters question rivals’ masculinity as a way to try to undermine their political authority. With Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump as the presumptive nominees for their respective parties, we can be sure that this presidential campaign will continue to constitute a gathering of lightning rods for the further exploration of masculinity and misogyny in elections and in politics more broadly.

Featured image credit: Presidential podium by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Masculinity, misogyny, and presidential image-making in the US and Russia appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers