Oxford University Press's Blog, page 484

July 26, 2016

Top 10 tips to tackling and transforming piano technique

We have all attended concerts where a performer dazzled us with technique that seemed hardly humanly possible – a phenomenon that has been a part of musical performances throughout history. In a 1783 anecdotal memory by Johann Matthias Gesner, the ability of J. S. Bach’s playing was described to “effect what not many Orpheuses, nor twenty Arions, could achieve.” And who can resist the Franz Liszt caricature in the April 3, 1886 edition of La Vie Parisienne, replete with eight arms flailing about in technical wizardry, to showcase a talent some say resulted from a pact with the devil? Although achieving Lisztian or Bach-like technique may be elusive, by turning to the wisdom and advice from eighteenth-century keyboard masters, tackling and transforming one’s personal technique is within reach.

Eighteenth-century musicians instruct that music must have something to say and technique or “good execution,” as it was described, is the means to this end. Although the fortepiano (the eighteenth-century instrument) had a lighter, quicker, and more responsive action with a more immediate attack and decay than today’s piano, much of the technical approach is directly applicable to the modern piano. By incorporating these tips, performing repertoire from all eras and genres will be substantially elevated.

Deportment. Commonly held beliefs regarding the body at rest are timeless: calmly address the keyboard in the middle, at an appropriate distance from the keys, at a comfortable height on the bench to facilitate ease of movement. Descriptions of Mozart and Beethoven support this natural posture and Türk ruthlessly warned against distorted facial expressions, grimaces, snorts, and grunts!

The Gesture. Most musical concepts are germinated through small gestures (oftentimes delineated by two-four note groups slurred together) that combine and develop into phrases, sections, and the complete whole. Physical gestures should match the music.

From the Neck Down. The forearm lies naturally, just as it is attached to the arm, and the hand extends naturally from the forearm. The arm supports the hand, the hand the fingers. The forearm carries the hand sideways to each new location. The full arm works from the shoulder and is used to shift the hand into or back from the raised keys and navigate large shifts in keyboard location.

The Wrist. Execution of the gesture is initiated by a supple wrist. Using Beethoven’s advice, develop the feeling of musical impulse while playing two-note slurs. “The purpose is to withdraw the hand lightly. This will be achieved if it [the hand] is always placed firmly on the first of the two slurred notes and is lifted almost vertically [by the wrist] as the second note is touched.”

The Hand. The best position is with a compact hand. It is the default position. The calmer the arm and hand, the more sure the motion of the fingers.

The Fingers. The fingers do the lion’s share of the work, with a natural arch and relaxed muscles as when in a D major pentachord with fingers on the outer edges of the black keys: a constantly curved, at-the-ready attitude, resting lightly on the keys unless extending for a large interval.

Fingering. For most instruments wrong fingering equals wrong note. Sadly, pianists can stumble along, playing the right pitches, while all the while making a complete mess of the musical message! And, fingering is unequivocally interconnected to musicality and is inseparable from interpretation. Fingering serves a musical function that is equally important to, and may surpass, the technical role. The best musical effect trumps the easiest fingering choices. Determining the best fingering oftentimes produces the easiest means. For instance, using legato fingering in a passage that contains breaks in the line with gestures articulated by slurs is not the best effect and actually creates execution difficulties.

Consistency. Keeping a consistent hand shape provides greater reliability in outcomes. For instance, if a gesture is repeated in a different place on the keyboard and the hand shape (and fingering) remains consistent, it is more likely that the same type of sound will be duplicated in the new location. Or, as dynamics change, the focus of the tone will be sustained with a consistent hand shape.

Structural Function. The bass line (or left hand) is the foundation. It is responsible for setting the tempo and rhythmic energy, providing direction and timing, and clarifying harmonic rhythm. Listen and build from the bass up. Many technical difficulties will melt away.

Willingness. Willingness to develop and incorporate concepts from the eighteenth century will result in a style that is easier to execute, contains new palettes of color, and provides unimagined sound energy. Weaknesses will be exposed, magnified, and become quite transparent; for there is no hiding behind the long legato line, the thick pedal, or weighty chords. Yet, working through these issues provides great opportunities for improvement. The hand and body will adjust. Improved responsiveness and control will emerge. Technique on all repertoire will become better. It is well-worth the effort.

Image credit: “fortepiano” by Giovanni Morelli. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Top 10 tips to tackling and transforming piano technique appeared first on OUPblog.

Post-award remedies before the arbitral tribunal: a neglected means of streamlining arbitration

One of the reasons why parties choose arbitration is its time-efficiency. This is mainly due to the fact that the arbitral award decides the dispute in a final and binding manner and is subject to no appeal. The award can rather be attacked only by an application for setting aside which is mainly limited to procedural irregularities. Although time-efficiency belongs to the traditional advantages of arbitration, the users of arbitration have over the last years significantly increased the pressure to control time (and cost) in arbitration. While the main focus has rested on the arbitral proceedings, the post-award stage also merits a closer look. In this context, a recent holding of the German Federal Supreme Court has drawn the attention to an innovative stipulation.

Each setting aside application entails a double risk for effective and timely dispute resolution: if successful, setting aside of the arbitral award leaves the parties with nothing but costs and efforts after at times long and expensive arbitral proceedings. And even if (as often) the setting aside application finally remains unsuccessful, its pendency alone extends the period of uncertainty and increases the costs of dispute resolution.

Under the most radical approach, the parties are given the freedom to abandon the entire setting aside remedy already in their arbitration agreement. This route has been chosen by Switzerland, Belgium, Sweden (each notably only for non-nationals of their states), and France in order to promote these countries as locations for effective dispute resolution. While abandoning setting aside proceedings indeed accelerates the final resolution of the dispute, such acceleration comes at a high price, namely that arbitral awards that violate public policy or are otherwise evidently flawed remain in existence. It is true that such arbitral awards cannot be enforced against their debtors unless they are declared enforceable – which has little prospect of success given that the grounds for denial of recognition and enforceability mirror the grounds for setting aside. This, however, is of no avail if the arbitral award lacks enforceable content. It is also not in the parties’ best interest to eliminate from the outset any risk that procedural violations will be sanctioned.

Instead of excluding remedies against the violation of procedural rules, implementation of additional remedies is the more efficient way to accelerate the final dispute resolution

Instead of excluding remedies against the violation of procedural rules, implementation of additional remedies is the more efficient way to accelerate the final dispute resolution. As that may sound odd at first, it merits further explanation: the arbitration agreement may add a remedy according to which each party can file objections against the arbitral award which would qualify as grounds for setting aside with the arbitral tribunal within a short deadline. The arbitral tribunal therewith gets a second chance to revisit irregularities in the arbitral proceedings (in particular if it had not been aware of them in the pre-award stage) and to remedy them. The arbitral tribunal has a strong incentive to cure procedural defects in order to avoid that its award will be set aside subsequently. Even if the arbitral tribunal decides to adhere to its previous decision, it can substantiate why it does so and thus effectively reduce the number of subsequent setting aside proceedings.

This additional remedy becomes a means of accelerating the proceedings if the parties are precluded in subsequent setting aside proceedings with objections that they could have brought (but didn’t bring) under the additional remedy. Despite its exclusionary effect, such an additional remedy doesn’t limit the parties’ legal protection. If the arbitral tribunal doesn’t remedy the alleged procedural shortcoming, the party can still file a setting aside application with the competent state court.

Such an additional remedy is suitable for all grounds for setting aside that the arbitral tribunal may cure, in particular for violations of due process. Due process violations indeed represent the single most important ground raised in setting aside applications – and they could be better dealt with initially by the arbitral tribunal: the tribunal is already familiar with the dispute and with its own proceedings while the state court needs to gather the facts first. That is why the arbitral tribunal can make a faster decision than the state court. A decision by the arbitral tribunal will also avoid additional court fees.

A similar effect can be achieved if the state court suspends the setting aside proceedings and gives the arbitral tribunal the opportunity to eliminate the grounds for setting aside (art 34 para 4 of the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration) or remits the case to the arbitral tribunal after it has set aside the award (s 1059 para 4 of the German Code of Civil Procedure). This route does, however, cause additional delay and court fees as compared to an additional remedy that is to be filed directly with the arbitral tribunal. Such a direct remedy therefore remains the first choice.

Accordingly, an additional remedy to the arbitral tribunal may contribute to preventing both founded and unfounded setting aside applications. It does, however, need to be implemented either by law, by party agreement or in institutional rules. The German Federal Supreme Court (order of 16 April 2015, file no. I ZB 3/14) has recently recognized such a stipulation in an arbitration agreement. There are no reasons evident why other courts should decide differently.

Feature image credit: Nearly Ten by Lewis Dowling. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Post-award remedies before the arbitral tribunal: a neglected means of streamlining arbitration appeared first on OUPblog.

July 25, 2016

The lifelong importance of nutrition in pregnancy for brain development

The importance of a healthy diet for proper functioning of the brain is increasingly being recognized. Week in, week out studies appear recommending a high intake of certain foods in order to achieve optimal brain function and prevent brain diseases. Although it is definitely no punishment for the most of us to increase our chocolate consumption to boost brain function, the most important period during which nutrition affects our brain may already be behind us.

Nutrition affects the brain throughout life, but it is potentially most important during the critical prenatal period, during which the lion’s share of our brain development takes place. During the time we spend in the womb, our brains undergo dramatic changes. The fetal nervous system from which the brain and spinal cord progress is one of the first systems to develop. Its foundations are laid down during the very first days of pregnancy. At the end of pregnancy, the brain has grown exponentially and is capable of learning and forming memories. It is actually not very hard to imagine that to lay a good foundation for the brain it is of utmost importance to receive the best building blocks through proper nutrition of the mother.

A very dramatic illustration of the consequences of not receiving adequate nutrition was shown in a study from the seventies in which Zena Stein and colleagues investigated the effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on the development of babies. The Dutch ‘Hungerwinter’ was a period of severe famine that struck the Western part of the Netherlands at the end of World War II. There was so little food available that even pregnant women suffered from severe undernutrition. Stein and her colleagues found that babies that had been exposed to the famine during the first trimester of pregnancy had increased rates of birth defects of the central nervous system.

The babies who were born around the time of the Dutch famine are currently about 70 years old. In Amsterdam, we have been following a cohort of people who were all born around the time of the famine from the age of 50 onwards and investigated their health during four waves of research. In each of these studies we compared people who had been exposed to the famine during early, mid-, or late pregnancy to people who had been unexposed to the famine during pregnancy. At age 50, the men and women who had been exposed to the famine in early gestation were shown to more often have heart disease accompanied by risk factors for heart disease such as increased cholesterol levels and obesity. At age 63 years, it also appeared that sadly the women who had been exposed to the famine early gestation, had died more often than their contemporaries.

Instigated by the research of the late David Barker and his colleagues who showed that low birth weight as a marker of a poor (nutritional) fetal environment was associated with an increased risk for heart disease and type 2 diabetes, we initially focused our studies in the Dutch famine birth cohort on cardio-metabolic health. At age 58 years, the participants of the cohort underwent a cardiovascular stress testing procedure and as a part of the procedure they performed a so called Stroop task. In this task, you have to name the color of the ink in which a color name is written. Doing this requires selective attention. People who had been exposed to the famine in early gestation, performed much worse on this task. As selective attention is a cognitively ability that is one of the first to deteriorate with increasing age and performance on a computerized Stroop task has been shown to be a predictor for development of Alzheimer’s Disease, we suspected that those who had been exposed to famine in early gestation may not only be at increased risk for cardio-metabolic disease but may also be at higher risk for accelerated ageing of the brain.

To investigate this further, we studied a subsample of our cohort by performing MRI scans of their brains. The first analyses of these scans showed that the intracranial volume and total brain volume in men exposed to famine in early gestation was smaller than the volumes in the control group. We did not find this difference in women, which may be due to the fact that we have studied a relatively healthy sample of exposed women as the more unhealthy women may have already died.

When we adjusted our analyses on total brain volume for the differences in intracranial volume, the effects of famine exposure on brain volume disappeared. This means that the effect of famine exposure seems to apply to intracranial volume predominantly. Intracranial volume is presumed to be a measure of the maximum size that the brain has reached during lifespan. While brain volume tends to decrease with age, intracranial volume tends to stay the same, although recent studies have cast doubt over this assumption. It is therefore difficult to say whether the smaller brains in the exposed men have been smaller from the start or have become smaller with increasing age. Smaller brain size attained in childhood has been shown to be associated with the development of Alzheimer’s Disease which makes us wonder whether prenatal exposure to undernutrition also increases the risk for Alzheimer’s Disease.

In general, we think that it is striking that the effect of a period of undernutrition in early life is still visible in the brain after almost 70 years. It underscores the vital impact that nutrition in early life has on the brain and may have for the rest of your life.

Featured image credit: Pregnancy by Greyerbaby. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The lifelong importance of nutrition in pregnancy for brain development appeared first on OUPblog.

The perpetual Oxford tourist: what to see and do in the city of dreaming spires

This week, the International Association of Law Libraries is holding its 35th Annual Course in Oxford, United Kingdom. Oxford University Press is delighted to host the conference’s opening reception in our own offices on Great Clarendon Street. I hope that delegates will be sure to speak to my UK colleagues about fabulous restaurants, shops, and sites that they enjoy in the City of Oxford.

In my 17 years as an Oxford University Press employee, based in our US offices, I have my own fairly unique relationship with this wonderful city. Unlike my UK colleagues who know the city intimately as their home, I am someone who finds themselves both a perpetual and enthusiastic Oxford tourist.

While I heartily endorse visiting the world class Ashemolean Museum or inspecting Christopher Wren’s Tom Tower at Christ Church College, below are just a few of my favorite sites which may be more easily missed in a first trip to Oxford.

Museum of the History of Science

Museum of the History of Science – This free museum is in the original home of The Ashmolean and is tucked next to Christopher Wren’s majestic Sheldonian theatre. The permanent collection at the museum is a delight for enthusiasts of both history and science. From ancient ornate astrolabes to Marconi’s radio equipment, to the actual chalkboard (behind glass) that captured Albert Einstein’s handwritten equations, there are ample opportunities to enjoy a close encounter with great moments in science. My favorite visits to the museum, however, have involved their fascinating temporary exhibits which they also curate virtually. From the oddity of Nostradamas’s astrolabe to the heartbreaking note in a mother’s journal of the death of Henry Moseley, these exhibits are ones I remember long after my visit.

The Bodleian Library

The history of the Bodleian Library is as rich as the history of Oxford, and a tour of the library is a must. While admittance into the Radcliffe Camera alone would be worth the price of admission, knowledgeable tour guides will also point out gargoyles in the shape of beloved children’s book characters, and sites featured in the Harry Potter films. Even if one does not have time for a tour, the new Bodleian Treasures should not be missed! Among the many treasures are copy of the Magna Carter, a Gutenberg Bible, drafts by Kafka, Milton, and Mary Shelley, and even a hand drawn map of Narnia by C.S. Lewis.

New College Lane

After a visit to the Bodleian or Blackwell’s Bookshop, I love to take a stroll around New College lane. Every good tourist should take a moment for a photo with Oxford’s own Bridge of Sighs, just a few steps from both the Bodleian and the Sheldonian theatre. Walking under the bridge, one may duck down the St. Helen’s Passage as it winds its way to the medieval Turf Tavern. After a pint or a meal, you can return to continue down the lane. On the left a small marker notes the home of Edmund Halley. As the road passes the entrance to New College itself, the greatest treat is to look up and enjoy some of Oxford’s famous gargoyles and grotesques, particularly those that appear to be inspired by exotic Australian wildlife. If one signs up for the excellent ghost tour offered nearby, they may also point out what is rumored to be the most haunted spot in all of Oxford on this winding road.

Magdalen College

Magdalen College—Oxford University is not made up of one large campus but instead 38 separate colleges, all with their own histories and distinguished alumni. While a visit to Merton College is a delight for lovers of Tolkein, and Lincoln College is a happy pilgrimage for my fellow Wesleyans, I have a great fondness for Magdalen College. Walk in the footsteps of C.S. Lewis, Oscar Wilde, and Lawrence of Arabia while taking in the views of the college’s stunning Deer Park and the River Cherwell.

Oxford University Press Museum

OUP’s own museum has fantastic displays charting our own 500 year history. With historic printing equipment, a first edition of Alice in Wonderland, and displays on the history of the Oxford English Dictionary, a visit is a must for any book lover. The best way to enjoy the museum is to have tour from OUP’s own archivist, Martin Maw. His enthusiasm for OUP’s history is only exceeded by his knowledge of hundred- year-old office intrigue.

Featured image: “Oxford street” by Abdulhakeem Samae, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The perpetual Oxford tourist: what to see and do in the city of dreaming spires appeared first on OUPblog.

French language in International Law

French is the language of diplomacy, German the language of science, and English the language of trade.

Whereas German has been displaced by English in science, French continues to occupy a privileged position in international diplomacy. Its use is protected by its designation as one of the two working languages of the United Nations (UN), the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, and ad hoc UN-backed tribunals. At these courts and tribunals, documents and oral submissions may be presented in French or English and must be translated into the other language, at great expense.

Since the entrenchment of French, population and economic growth in the developing world, combined with the now pervasive use of English, have changed where and how languages are used. This justifies—or one might say necessitates—an assessment of whether French should continue to enjoy its privileged position within international law.

On a generous measure, French is the sixth most spoken language globally with 220 million French-speakers (including ‘partial-speakers’), ranked only after Chinese Mandarin, English, Hindi, Spanish and Arabic. By comparison, there are approximately 1.5 billion people who speak English, of whom 339 million are native English-speakers.

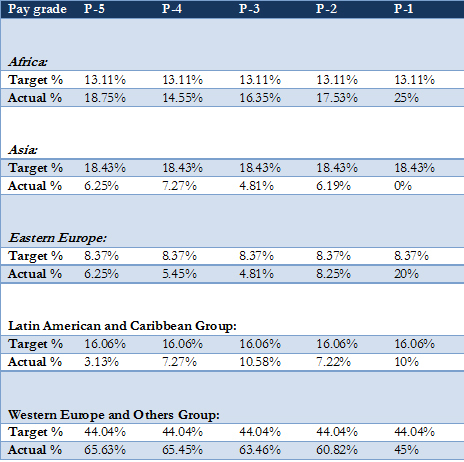

One might conclude that using two working languages brings diversity. But the data below on the national origin of personnel at the International Criminal Court (ICC) suggests otherwise. At international courts and tribunals, one hears both French and English, coupled with an expectation that personnel are able to converse in both. One can imagine a Venn diagram consisting of an English-speakers’ circle of 1.5 billion people and a French-speakers’ circle of 220 million. The use of two working languages encourages the ICC and other bilingual courts to draw their personnel from the overlapping portion.

This French-English bilingual club is an exclusive one with very sparse membership in Asia and Latin America. According to the French Government, only 1.16% of the 220 million French-speakers are in Asia and Oceania. This amounts to a mere 2.6 million people among the 4.3 billion people of that region. Similarly, only 7.66% of French-speakers are found in the Americas and the Caribbean, i.e. 16.9 million people.

With these statistics in mind, it is little wonder that the ICC reports a serious underrepresentation of personnel from Asia and Latin American at each of its pay grades, P-1 to P-5 (as at March 2014). The underrepresentation of Asians is severe. At the P-1 grade, the ICC attracted a dismal zero employees from Asia.

Image credit: table reproduced with kind permission from the author.

Image credit: table reproduced with kind permission from the author.Conversely, the Africa and Western Europe groups are overrepresented at each grade. Again, this may leave little wonder, as these are the regions where French-speakers are concentrated: 39.87% of whom are in Europe and 36.03% are in sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean. English-speakers, on the other hand, are more globally spread.

The use of the French language looks to be at least a partial cause of the inequitable participation at the ICC, and the deficit in cultural diversity and different values, ideas and ideologies that results. The current bilingual arrangement risks imposing the thoughts and culture of only a narrow pool of humanity onto the international community, calling into question the legitimacy of the ICC and other bilingual courts.

If English were the sole working language, the ICC would be free to recruit from a pool of 1.5 billion people, without regard for whether candidates happen also to speak French. It is also arguable that the ICC having a well-oiled, bilingual French-English machine risks a disproportionate allocation of resources to African jurisdictions. If the system of international criminal law were more open to those who speak English plus any other language this might spur the broader allocation of investigative resources across the globe.

Of course, there are arguments for retaining French, such as the current workload of the ICC focusing on Francophone Africa. But, if French were discontinued as a mandatory second working language, it can still be used when needs must. Article 50 of the Rome Statute allows any of the six UN languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish) to be used as a working language if the court case dictates.

Whereas the bilingual French-English system may once have aimed at diversity, it now appears to produce the opposite effect. Remaining reasons for retaining French might stem from a desire to maintain the status quo, national prestige, or motivations of national interest. These factors should not take priority over the interests of the international community at large.

Featured image credit: The Allée des Nations in front of the Palace of Nations by Tom Page. CC-BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post French language in International Law appeared first on OUPblog.

July 24, 2016

Announcing the winner of the 2016 Clinical Placement Competition

The study and practice of medicine is an increasingly global pursuit – and experience abroad is a crucial component of any young doctor’s training. In our increasingly interconnected world, improving these links is vital to better healthcare, improved knowledge, and patient outcomes. This May, our 2016 Clinical Placement Competition came to a close. In partnership with Projects Abroad, we offered one lucky medical student the chance to practice their clinical skills, with £2,000 towards a clinical placement in a country of their choice.

We asked entrants to send a photograph with a caption, explaining “What does being a doctor mean to you?” From over 100 submissions, we are proud to announce that this year’s winner is Iona Maxwell. Iona impressed the judging panel with her well-framed and eye catching image, which really captured the challenges, adversities, as well as opportunities for innovation and adventure – faced by modern medics. We caught up with Iona, to find out more about her aspirations in medicine.

2016 Clinical Placement Competition winning photo submission by Iona Maxwell. Used with permission.

2016 Clinical Placement Competition winning photo submission by Iona Maxwell. Used with permission.Can you tell us some more about your winning photograph?

This photo was taken in the remote village of Rio Cana, Panama, last summer. I was working with an amazing charity – Floating Doctors – that provides basic medical care to the people of Panama, who otherwise have very limited access to healthcare. Each day we packed up our ‘cayuco’ or canoe with our basic pharmacy and diagnostic kit and headed out to a different village where we set up a clinic, and saw whoever wanted to be seen. We usually would end up with a queue of locals around the block waiting to see one of our team. The team was made up of volunteer medical students, doctors, nurses, and some volunteers with no medical experience but excellent Spanish, who could help us with translating.

You really are back to basics when working in such a remote setting, and a child comes in with symptoms of asthma – unable to play football with his friends without starting to wheeze. We had some inhalers in the pharmacy box but no spacers, so another volunteer cleaned out a plastic bottle and cut it into shape to fit perfectly around the inhaler. Using a spacer optimizes delivery of the drug to the lungs, and makes it a bit easier to use for younger children. Obviously his friends immediately all gathered around and wanted one for themselves!

Plastic bottles – more useful than you’d think! Image Credit: “Plastic Bottles” by Hans. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Plastic bottles – more useful than you’d think! Image Credit: “Plastic Bottles” by Hans. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.You state that being a doctor means ‘working with what you’ve got’ – can you expand on that?

Being a doctor is all about assessing the patient in front of you, and then doing the best you can to alleviate their symptoms and cure their disease if possible. In the Western world we have access to incredible diagnostic equipment and advanced medicines, but once you strip all that away you are left with the most basic equipment – your eyes, ears, hands, and if you’re lucky a stethoscope and some medicines. We had a box of inhalers but this young patient would have struggled to use them correctly, so using the only material available to us we came up with a solution to help him out – a plastic bottle. This thought process still applies in the most developed countries – what simple things can we do as doctors to help the patient sitting in front of us – how can we best work with what we’ve got?

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

I’m 25 and am now a final year medical student at Southampton University, currently on placement on the Isle of Wight. My parents live in Eastbourne with our two border terriers and I have two lovely sisters. I’ve been involved with the medical society at university, and last year I was Medsoc President – the best part of which was organising our annual Medics Ball. When I’m not on placement I play mixed hockey and love to travel.

What drew you to medicine?

I actually initially went to university to read Classics – but after a year I decided it was Medicine that I wanted to do. I love languages and so studying classics seemed a good choice, but I realised I had no idea what I would have done with that degree and more and more wanted to be doing a course like medicine. Hopefully it will be such a fulfilling and rewarding career, and the options within it are endless.

Do you have any advice for those starting out?

Get as much experience as you can – both of what doctors do day to day, but also what goes on behind the scenes. It’s a long old slog, so make sure it is what you want to do before you sign up – and remember there is a lot of flexibility within it, so keep an open mind!

Where are you planning to take your placement, and what are you hoping to achieve?

I’m hoping to maybe go to Tanzania or Nepal – I’m lucky to have been able to travel around Central and South America and South East Asia already, so Nepal was next on my list but the placements in Tanzania look amazing too! I’ve worked on medical placements in Vietnam and Panama so I’m hoping to further my knowledge of how medical systems work in different countries, and perhaps get some experience with conditions that we might not see in the United Kingdom.

Aside from traveling for clinical placements, where would you most like to travel to – and why?

I am lucky enough to have traveled to all of the continents except Antarctica so that is top of my list! I’d also love to go North and see the northern lights.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Fiji, Beach, Sand’ by tpsdave. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Announcing the winner of the 2016 Clinical Placement Competition appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and the border – problems of the past haunt Ireland’s uncertain future

On 23 June 2016 a majority of people in England and Wales voted to Leave the European Union. A majority of Scottish voters opted to Remain and, so too, did a clear majority of voters in Northern Ireland. These results have produced uncertainty about the future direction of relationships across these islands.

Irish concerns played a very small part during the referendum debate and, since then, much of the related commentary has focused on its possible implications for the peace process. British-Irish relations and human rights legislation, both framed within a European context, provide much of the architecture for the Good Friday Agreement and subsequent accords. EU funding has promoted community relations on the ground, and the practical invisibility of the border up to now has helped to make partition feel less provocative to its opponents. Obviously there are possible consequences to any unravelling of those things, but Brexit will not automatically lead to the return of watchtowers or army patrols. What it might mean in the immediate term can be better understood, less through the prism of the recent Troubles (although the memory of those times remains strong), than the fifty-year period until 1972, after which, both Britain and Ireland joined the European Economic Community.

The Irish border was created and confirmed by the Government of Ireland Act 1920 and the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. That followed a protracted political dispute and shorter military conflict over the constitutional relationship between Ireland and Britain. Its shape and location reflected the inheritance of the past and the balance of social and political forces on and between both islands. Following true to the old county lines, in place but of no great significance since the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, it sliced through houses, parishes, and at least one village; cutting towns from their hinterlands and homesteads from their farms. Initially it was expected that the worst of these glitches would be ironed out by the Irish Boundary Commission provided for in the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Although it was established in 1924, that commission collapsed in failure a year later, leaving these anomalies behind.

Cars queue at Belleek border crossing by Museum Services, Fermanagh and Omagh District Council. Used with permission.

Cars queue at Belleek border crossing by Museum Services, Fermanagh and Omagh District Council. Used with permission.By that time, the economic border had already taken shape, with the advent of a customs barrier on April Fool’s day 1923. Significantly in the current context, this was not directly desired by either party, but arose indirectly in consequence of the anti-partitionist Irish Free State government’s desire for fiscal sovereignty. John Simms of Lifford, County Donegal complained to the Irish Boundary Commissioners of ‘the performances going on’ at the bridge separating that town from its near neighbour, Strabane in County Tyrone. Legally passing the border meant inconvenience; delay, long detours in places, and frustration at the hands of an often inflexible officialdom. For those carrying goods, even non-dutiable commodities had to be recorded ‘for statistical purposes.’

In sharp contrast to most contemporary boundaries, the Irish border in this period was primarily a regiment of things. Whereas – with very few exceptions – efforts to arrest the passage of living human bodies were virtually unknown (dead bodies could be more complicated), anything that might adorn them – jewellery, watches, consumer products, and even certain types of clothing such as fur coats or uniforms – was potentially subject to restriction.

Not only were local shops and services effected. Imported goods brought into one jurisdiction on journey to the other were held in bond until the duty was paid. Derry tea trader Neill McLoone explained how the flow of his most global of merchandize was regularly brought to a standstill:

If we get an order for 3 chests of tea from Co. Sligo or Cavan, – we have this tea in bond in Derry – we have to go to the customs authorities here. The bonded warehouse only opens 2 days in the week, and if we want to get an order on a Friday, we cannot get it out of bond until the following Tuesday. If we do not get it out in sufficient time to make it to the border, we then have to wait till Wednesday.

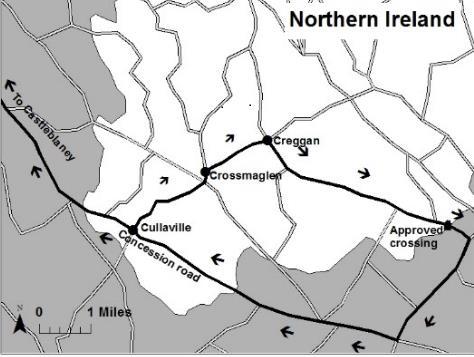

That people were free to cross the Irish border, did not mean that movement itself was not impeded. Although some 180 roads cross the border, of these, just sixteen crossings were ‘approved’ – equipped with customs facilities, and the only routes by which dutiable goods could legally be brought over. From 1925 this included motor vehicles, with car owners required to deposit a bond and acquire a three-part ‘triptyque’ pass to be stamped in and out during daylight hours (after dark the customs men remained on duty – not to enable cars to pass but to stop them).

In addition to these sixteen approved crossings, there also existed a handful of ‘concession’ roads. These linked either two places in the South or two places in the North, but passed through the other territory on the way. The ‘concession’ allowed through traffic to transit South-to-South or North-to-North without restriction, but not to travel South-to-North or North-to-South.

The most direct legal route from Cullaville, South Armagh, to nearby Castleblaney, County Monaghan in the early 1960s, and alternative ‘unapproved’ crossings. Map by Peter Leary, used with permission.

The most direct legal route from Cullaville, South Armagh, to nearby Castleblaney, County Monaghan in the early 1960s, and alternative ‘unapproved’ crossings. Map by Peter Leary, used with permission.On the concession road between Dundalk and Castleblaney, for example, residents of the South Armagh village of Cullaville who wished to travel to Castleblaney were compelled ‘to set off in the opposite direction . . . making a legal detour of close on thirty miles.’ Having entered the South via an approved crossing – and had their passes duly stamped – they had then to ‘get back on to the concession route and motor past their own doors without stopping, because motor traffic using the concession route [was not permitted to] stop on it anywhere along its length in Northern Ireland’ (Irish News, 3 Aug. 1963). It was, as one American wartime observer put it, ‘one of the worst examples of frontier bureaucracy in existence.’

How much of all of this is likely to return will depend on the Brexit negotiations. It certainly has the potential to destabilise the wider situation. Long before the recent Troubles, republicans regularly targeted customs stations for destruction as one locally-popular act, through which, ‘the border’ might symbolically be erased (Irish Independent, 19 Aug. 1937). Past experience suggests that bringing the border back as a ‘hard’ reality of everyday life will generate opportunities – not least for smugglers, cockfight enthusiasts, and anyone hoping to evade the authorities in either state or make a career in the customs services. But it may leave many others having to make the most of challenging circumstances.

Headline image credit: River Mourne, Strabane, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland looking upstream from the Mourne River Bridge by Ardfern. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Brexit and the border – problems of the past haunt Ireland’s uncertain future appeared first on OUPblog.

Why God would not send his sons to Oxford: parenting and the problem of evil

Imagine a London merchant deliberating whether to send his ten sons to Oxford or to Cambridge. Leafing through the flyers, he learns that, if he sends the boys to Cambridge, they will make “considerable progress in the sciences as well as in virtue, so that their merit will elevate them to honourable occupations for the rest of their lives” — on the other hand, if he sends them to Oxford, “they will become depraved, they will become rascals, and they will pass from mischief to mischief until the law will have to set them in order, and condemn them to various punishments.” Never doubting the truth of these predictions, he still decides to send the lads to Oxford, and not to Cambridge. “Is it not clear, according to our common notions, that 1) this merchant wants his sons to be wicked and miserable; and 2) that, consequently, he is acting in a way that is contrary to goodness and to the love of virtue?”

This is not an excerpt from a Cambridge undergraduate prospectus. It is a version of the problem of evil: the age-old question of how an all-good, all-knowing and all-powerful God could permit the presence of evil in the world. It was formulated in the early eighteenth century by Pierre Bayle, a controversial French philosopher living as a refugee in Rotterdam.

The basic argument is as follows: it’s as rationally impossible for a good father to have knowingly, lovingly and wilfully sent his sons to this depraved version of Oxford, as it is for God to have committed mankind to a fallen state and a corrupted earth. Being God, he must have known with perfect foresight that, if he placed Adam and Eve in a paradise where they would be tempted, they would succumb to this temptation; being God, he was perfectly able to prevent the moment of the Fall; being God, he was obliged by his own goodness to prevent it. Nevertheless, says Bayle, the evidence suggests that he did not. Ergo, we must either throw reason out of our considerations altogether, and love God blindly and submissively in the face of all evidence against him; or we must conclude that God intended man to suffer; that evil is the work of God. (Or even: that God does not, cannot, exist).

Portrait of French writer and philosopher Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) by Louis Ferdinand Elle the Younger, circa 1675. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of French writer and philosopher Pierre Bayle (1647-1706) by Louis Ferdinand Elle the Younger, circa 1675. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Thinking these things, today, may not strike us as so outrageous, but to the readers of the time, a more obscene argument was hardly conceivable. The element of comparison, especially, was sensitive: Bayle adamantly and obsessively drew parallels between God and a variety of bad fathers, heartless mothers, wicked stepmothers, and cruel kings. Imagine, for instance, a mother who has given her daughters permission to go to a ball, and then discovers that they will necessarily “succumb to temptations and lose their virginity there”. If she nevertheless allowed them to go dancing, would this not prove that she was acting rather as “an irritated, cruel stepmother” than as a loving mother, just like the merchant of London would act irresponsibly, and even wickedly, in sending his sons to that supposed bastion of depravity: Oxford?

But surely, one might object, that’s not true for the human condition. Yes, there is evil; yes, there is suffering — but that’s not all there is. Can’t we justify God’s creation by pointing at its better, brighter side?

Bayle bites the bullet. First of all, he argues, if God is infinitely good and wise and powerful, then even the smallest grain of misfortune is incompatible with the nature of the divine being. Second, and more importantly: there is much more evil and suffering than there is goodness and happiness in the world. This is true quantitatively, since “history is nothing but the crimes and misfortunes of the human race”, as well as qualitatively, since “one hour of misery contains more that is bad, than there is good in six or seven comfortable days.” (Bayle suffered from terrible migraines.) This is philosophical pessimism in the highest voltage, though it did not yet receive that label: in fact the terms ‘optimist’ and ‘pessimism’ were coined a few decades afterwards, as a direct result of Bayle’s discussions.

These days, the problem of evil still features in theological and philosophical discussions, but it is often seen as antiquarian, no longer a central topic for a secular age. Unlike Bayle and his contemporaries, ‘we’ of the modern, Western world don’t tend to see natural disasters as a form of ‘natural’ evil; we see it as bad luck. Even moral evil is sometimes reduced to genetics or circumstances; criminals are conditioned by genes or traumas; who is ultimately responsible for anything? And yet it seems that Bayle’s ideas have made an inadvertent comeback in recent years, in a philosophical context that is apparently wholly different, and at the same time, strangely related. This is the debate on anti-natalism: whether having children is morally permissible.

This may seem like a topic that couldn’t be further away from the problem of evil, but in fact the two problems are more closely related than appears at first sight. After all, the traditional problem of evil is essentially an attempt to address an ethics of creation: how could God be justified in creating a being destined to experience suffering? Bearing this in mind, it is perhaps not so surprising that Bayle uses the example of bad parenting in order to make his point. God should be the perfect parent, and a perfect parent would not create a child knowing that it would suffer (either a little or a lot). One might go further: on this line, a perfect parent would decide not to (pro)create.

At this point, the step from the problem of evil (ethics of creation) to the problem of parenting (ethics of procreation) is smaller than it seems. This becomes clear if Bayle is compared to another, more recent philosopher: David Benatar, who provoked widespread outrage by arguing that procreation is never morally permissible; that it is true for every person that it would have been better never to have been.

Bayle could not have agreed more. Both philosophers (who share a talent for footnotes as well as for pessimism) argue along similar lines in order to make their highly controversial points. Both agree that there is more suffering in the world than there is happiness to compensate. The sheer evidence of our own experience — we have all seen or heard of people suffering unimaginable hardships, cruelties, or diseases — should be enough to prove the point that it is infinitely better not to create a being susceptible of such misfortunes. If this evidence does not convince, both argue that even the smallest possibility of such suffering (or, indeed, of any suffering) should convince a truly responsible prospective parent, whether human or divine, to desist from creating. We may take risks in our own lives: we are never justified in placing such risks, and their consequences, on another person, even if — especially if — that person does not yet exist.

It is a temptation, when confronted with philosophers such as Bayle or Benatar, who challenge the most fundamental assumptions of their respective age, to dismiss their arguments as absurd or heretical or contrary to common sense. This was an insufficient response to Bayle; it is an insufficient response to Benatar. The problem of evil will and should continue to haunt philosophy, humanity, and religion, in whatever shapes and guises it still has in store for us. It is the test of every age if we can take it seriously.

Headline image: View of Oxford city from South Park, east Oxford. Photo by Kamyar Adl. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why God would not send his sons to Oxford: parenting and the problem of evil appeared first on OUPblog.

July 23, 2016

Preparing for ISME Glasgow

This weekend, the 32nd International Society for Music Education World Conference will be hosted in Glasgow, Scotland. Researchers, practitioners, and performers will gather to present concerts, talks and discussions. We asked Alice Hammel, co-author of Teaching Music to Students with Special Needs: A Label-Free Approach; Gary McPherson, co-author of Music in Our Lives: Rethinking Musical Ability, Development and Identity; Janice P. Smith, co-editor of Composing Our Future: Preparing Music Educators to Teach Composition; Maud Mary Hickey, author of Music Outside the Lines: Ideas for Composing in K-12 Music Classrooms; William I. Bauer, author of Music Learning Today: Digital Pedagogy for Creating, Performing, and Responding to Music; and Norm Hirschy, Senior Editor at Oxford University Press for their pre-ISME thoughts and plans.

What are you looking forward to at the conference?

Alice Hammel: I am very excited about attending ISME in Scotland. I will be presenting two projects at the Commission in Edinburgh the first week and then another presentation in Glasgow. This will be my very first international conference presentation. I plan to visit Lochness, Loch Lomond, and perhaps the Highlands of Scotland while I am there. I am also looking forward to meeting many other music educators from around the world.

Gary McPherson: Seeing so many wonderful friends. I love ISME conferences because they allow me to catch up with people I know and admire and often only see every second year at these world conferences. The keynotes are always superb and we get to hear and learn from many young and emerging music educators who will become the next generation of leaders within the world of music education.

Janice P. Smith: I am mostly looking forward to meeting up with old friends, making new ones, dining, and hearing wonderful music.

Maud Mary Hickey: I’m looking forward to catching up with old friends and meeting new. ISME allows me to connect with my international friends and researchers.

William I. Bauer: I am very much looking forward to conversations with colleagues from around the globe during the 2016 ISME conference. The program looks fantastic and it will be a pleasure to learn about the myriad of interesting projects conducted by individuals who are are shaping the future of music education. I am also looking forward to experiencing the natural beauty of Scotland, its music, and other cultural traditions.

Norm Hirschy: One of my favorite parts about ISME is the opportunity to meet people in music education from all across the globe. I am energized by the cross-cultural dialogue; we all have so much to learn from one another. I also look forward to attending panels and clapping, chanting, and even yes singing along.

If you’ve attended before, what were some of your favorite memories?

Gary McPherson: We get to hear performances from the finest young musicians worldwide, and experience music in ways that we could never experience in our home country. The Finish and South African choirs, musical performances from first national ensembles, and styles of music that I didn’t even know exist. Such wonderfully rich concerts are the hallmark of ISME World Conferences. These leave memories which last a life time.

Janice P. Smith: My only other ISME conference was in Thessaloniki and my favorite memories are of the music from many areas of the world, the wonderful yogurt and olive oil, swimming in the Aegean Sea, and showing a cab driver my iPhone to get me to the concert hall.

Maud Mary Hickey: I just love meeting new researchers from all over the world. I especially enjoy meeting people who I have read but never met in person! I also love trying out new food in whatever country ISME happens to be!

What else do you plan to do or see in Glasgow, time permitting?

Gary McPherson: Because I love Thai food, I’m on a mission to have a Thai meal with my friends in every cite across the globe where ISME has its world conference. I’ve still got a bit to go, but I’m getting there! And because of my Scottish heritage (my ancestors came to Australia in 1848) I want to get out and about in Glasgow – listen to the locals talk in the pubs and restaurants, and learn more about the Scottish way of life. This will surely be one of the most enjoyable ISME Conferences ever.

Janice P. Smith: Looking forward to seeing Glasgow Cathedral, Rouken Glen, National Piping Centre, George Square, Botanic Gardens (and tea room), vegan restaurants for me, and Venison Haggis for my companion. Maybe a Clyde River Cruise as well.

Maud Mary Hickey: My husband and I plan to golf four days in Edinburgh before going to Glasgow for the conference. Can’t wait!

If you’re attending the conference, we hope to see you by the Oxford University Press booth! You’ll have the chance to check out our books, including our new and bestselling titles on display at a 20% conference discount, and get free trial access to our suite of online products. To learn more about the ISME conference, check out their official website and follow along on Twitter @OUPMusic and with the #isme2016 and #ismeglasgow2016 hashtags.

Featured Image: Glasgow Cathedral by Michel Curi. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Preparing for ISME Glasgow appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond Brexit panic: an American perspective

By now, the early Brexit panic based on assumptions of catastrophe, disaster, and apocalypse, is giving way to more positive attitudes in the science fields. Yes, there are changes coming, sometimes painful, but there are also opportunities for new partnerships, fresh collaborations, and bolder directions.

I was on a month-long visit to the United Kingdom when the Brexit vote took place, immersing me in intense discussions with British researchers who have long-standing partnerships with European universities. The main immediate concerns of senior management at UK universities seem to be the uncertain status of the academics working, or planning to work, in the United Kingdom on European Union passports. They worry about the uncertain future of the considerable collaborative research funded by the EU, students planning to come from or go to the EU, and the status of students, staff, and faculty whose visa status may have to change. These are serious and legitimate concerns.

But university managers could also think about the potential new opportunities. The good news is that students, staff, and faculty have become comfortable in spending time in other labs to learn new methods and pursue new topics. These relationships often produce positive results, but not always. Now it is time to reconsider these choices, working hard to keep the good ones and shedding the weaker ones to try new possibilities.

As a US-based researcher, I hope to build stronger partnerships with colleagues at Southampton, Swansea, Nottingham, University College London, City University London, Edinburgh, Oxford, and other universities where I have visited and spoken in recent years. Having more regular British visitors and supported projects would be a welcome positive step for our lab. The recent announcement of the EPSRC and NSF agreement to allow projects with UK and US collaborators is a useful step. Our Computer Science Department at the University of Maryland had hundreds of post-graduate student applicants from China, India, Korea, etc., but not one from the United Kingdom. I’m eager to change that.

Scientist by FotoshopTofs. Public domain via Pixabay.

Scientist by FotoshopTofs. Public domain via Pixabay.While there will be challenges to obtaining funding and visas, many valuable European collaborations will continue. At the same time, increased possibilities of British collaboration with Commonwealth partners such as Canada and Australia could open up new directions. Increasing collaborations with international leaders such as Brazil, South Africa, China, and India could also stimulate novel projects, such as Swansea University’s FITLab on mobile devices in South Africa and India.

Another positive step is the EPSRC Industrial Cooperative Awards in Science & Technology (CASE), which support closer collaboration between academia and industry. These awards enable PhD students to work on problems generated by industrial needs, while carrying out advanced research. When well-designed, these kinds of collaborations are likely to produce the “twin-win” of valuable publications that also are on the fast track to commercialization. Instead of uncertain technology transfer, these twin-win projects can rapidly generate peer-reviewed papers and new or improved commercial products. An encouraging example that I learned about this past month was at the Edinburgh University’s Farr Institute, which pursues health informatics research. The poster at the entrance celebrated their “Innovative Industrial Collaborations: From licensing agreements to joint ventures and research collaboration, we foster partnerships between academic clinicians, medical researchers and industry”. I support the idea that more academics should take on real problems, with real data, and real users.

I believe that ideas developed with industry and civic partners can have the benefit of theories that are validated in the living laboratories of commerce and professional practice. Further support for close collaboration between universities and industry is based on growing evidence that papers co-authored between academics and industry professionals produce higher quality and greater impact than those written by all academics or all industry professionals.

So instead of Brexit panic, it’s time to invoke the inspirational phrase: “Keep Calm and Carry On”, which calls for resilience and resourcefulness in difficult times. Britain has a great tradition of research and academic leadership, so taking on fresh partners can be a hope-filled possibility.

Featured image: Brexit by Foto-Rabe. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Beyond Brexit panic: an American perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers