Oxford University Press's Blog, page 482

August 1, 2016

Changing tropical forest landscapes: A view from a small plane

We emerge from the thick tropical clouds that perpetually hang over Kota Kinabalu at this time of year. I crane my neck to get a good view through the plane window of the surreal profile of Mount Kinabalu, its multi-pronged rocky top standing well aloof of the surrounding clouds and forest. It seems as if the mountain, aware of its own splendour, has shaken off all vegetation from its peaks to better show off their plutonic immensity. Neighbouring lesser hills are overwhelmed by forest which runs rampant up and over all ridges and tops, but not on Kinabalu. As the plane skirts round Kinabalu’s southern edge the mountain slowly recedes, as does the cloud which clings to the coast. I turn my attention to the forest below. It is unbroken, filling valleys, and rising up and over ridges. Different shades of green linger in the forest canopy — lighter on the ridges and darker in valley bottoms. A large tree catches my eye, standing proud of the forest as if emulating Kinabalu itself. The view continues unchanged for forty minutes as the plane carries me across to Sabah’s east coast. The monotony of the forest is broken only by the glint of an occasional river. My interest is suddenly rekindled by a small dirt road, a rough settlement, white rock exposed in a small quarry — shockingly bright against the dark forest — then some fields, and a plantation of some sort. Settlements now come thick and fast as the forest is dissected by small roads and tracks. The forest quickly falls away in the few minutes before touch down, and collapses into a patchwork of small fragments before giving way entirely to fields and buildings, more roads, plenty of people, shops and traffic, and the runway. It is 1995, and I have arrived, for the first time, in Lahad Datu.

I have made the same journey to Sabah’s east coast many times in the 20 years since. My most recent visit was last year in 2015. While the mountain has changed little, the view beyond is completely transformed. Little by little, that monotonous green canopy has become increasing dissected. Gaps formed where trees were felled, and a filamentous network of logging roads penetrated the forest. Later, fields appeared within the forest, but over the years these grew in size and number until they enclosed patches of remnant forest. A new crop, oil palm, became firmly established at the outskirts of Lahad Datu, then gradually spread westwards towards the mountain on the other side of Sabah.

Other changes were apparent. In 1995 Kota Kinabalu was little more than a three street town, albeit pleasantly vibrant. It is now a regionally important centre. Industries and small businesses have proliferated, and tourists throng the markets and restaurants. There are two universities and, to my great appreciation given my student days are long past, several excellent hotels. Kota Kinabalu’s development reflects the increasing wealth of the region, and it is the lowland dipterocarp rain forest that I see below my plane that has provided this wealth.

Dipterocarp is the critical term. On Borneo, the Dipterocarpaceae comprise around 270 species of mostly massive trees. There are a further 200 species across Asia, and a few more in Africa. It is in Borneo, however, where they are most impressive. Over half the tree canopies that I saw through the plane window were dipterocarps. Crucially for our story, dipterocarp trees have excellent timber, and have been sought out all over Southeast Asia by logging companies. The unprocessed timber from a single tree can be worth over a thousand dollars. Malaysia’s timber export market is around US$1.3 billion annually. In dipterocarp forests, money really does grow on trees.

Mount Kinabalu by NepGrower at the English Language Wikipedia. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Mount Kinabalu by NepGrower at the English Language Wikipedia. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Logging of Sabah’s dipterocarp forest was the initial driver of Kota Kinabalu’s current prosperity. Rural people took advantage of the logging roads to access degraded forests which were cleared, initially in small patches, for agriculture. Later development led to the wholesale clearance of logged forest by companies intent on planting oil palm. This highly lucrative crop, with an export value of US$16 billion, now dwarfs timber values. Development, responding to global market demand for timber, oil palm, and other commodities, has alleviated poverty and generated unprecedented opportunities and wealth.

We have, however, also lost something. Dipterocarp forests are among the most biologically rich habitats anywhere on Earth. Orang-utans loom large in tourist brochures, but they are but the most charismatic of a great many forest denizens. When the gloom of the deep forest is alleviated by a gap in the canopy, we see birds, butterflies, beetles, and bees come and go. Lizards cautiously peer round tree trunks, while ants obliviously follow regimented schedules. A silent exclamation declaims a green viper in the undergrowth, motionless and poised. Canopy cacophonies of morning birds and evening frogs reveal much that we do not see. The trees underpin this biological wealth. Dipterocarps surround us, some with immense buttresses, and trunks that soar high into the canopy. None is quite the same as the next, and close inspection reveals a plenitude of forms. There is, literally, value in this view of life, as tourists flocking to Malaysia’s natural parks contribute US$12.3 billion to its economy.

My flights across Sabah have witnessed the loss of much of this forest. We should not be despondent — much still remains. What remains is often degraded, but it will recover with time. Indeed, Sabah has recognised its imperative to safeguard its biological heritage for the global community, as well as for its own citizens.

Research with our Malaysian partners in Sabah has taught me much about dipterocarps, but I have also learned something about society. True, logging and oil palm plantations have devastated large swathes of tropical dipterocarp forest, but in Sabah at least it is also the case that policy makers, land managers, and scientists, are working together to restore degraded forests to their former states.

Featured image credit: Logging road East Kalimantan 2005 by Aidenvironment. CC BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Changing tropical forest landscapes: A view from a small plane appeared first on OUPblog.

Culture change for women in Afghanistan

When Laura Bush said in April 2016 that she wanted the President of the United States to care about Afghan women, one could reasonably infer that she would rather see Hillary Clinton elected President than Donald Trump. Hillary has proclaimed that women’s rights are human rights, meaning that to the extent that human rights have become a part of mainstream political discourse, so should women’s rights. Human rights are universal rights under international law. If women’s rights are also human rights, then the violation of women’s rights cannot be merely an issue of cultural differences that must be accommodated under the mantle of cultural relativism.

Violations of women’s rights, however, often have a cultural component. For example, in 2014, a ten-year-old girl was raped by a mullah in a mosque in Kunduz, Afghanistan, and then subjected to the threat of “honor killing” from her own family; the mullah offered marriage to the ten-year-old victim instead, and the shelter where she had been staying returned her to her family. As the New York Times accurately observed, “The case itself would just be an aberrant atrocity, except that the resulting support for the mullah, and for the girl’s family and its honor killing plans, have become emblematic of a broader failure to help Afghan women who have been victims of violence.” Anger in Kunduz has been unleashed not against the mullah or the girl’s family but against the shelter that had given her sanctuary and against women activists who supported her and the shelter.

Modern laws have been enacted in many parts of the world but few have overcome entrenched customs. Many of the life-and-death problems women face cannot be solved by the usual template: laws and more laws. Sometimes laws can change even deeply embedded attitudes. Despite often vicious opposition to the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education in the United States, this case arguably transformed the cultural landscape in the South. But that presumes a robust rule-of-law tradition in which most people will obey even laws they disagree with, which may in turn create positive norm change. But this rule of law tradition is often weak if non-existent in many poor countries where rule of law projects are being pursued. Strong cultural norms, especially those that perpetuate women’s subordination, cannot be changed by passing laws declaring women’s equality or outlawing violence against women. Such norms must be explicitly and directly changed, through culture change projects.

Human rights are universal rights under international law

Culture is not homogeneous nor is it static and unchanging. Cultural traditions have changed over the years. What is now deemed “authentic” culture is most likely the result of multi-layered changes through the years. Once culture change is understood to be a part of every cultural landscape, it can be deliberately changed, to reflect respect for freedom and equality of all human beings. For example, there are many consciousness-raising campaigns to get men and boys to relate to women differently, to end domestic violence. Work to end female genital mutilation has included efforts to reframe the practice so that it can be less culturally charged and viewed as a health issue that is damaging to young girls. Cultural norms that see daughters as an economic burden to be married off and hence not truly one’s own have resulted in a devaluation of girls in many cultures. When there is not enough food for sons, daughters are the ones who go hungry. When there is not enough money for school for all the children, sons are sent and daughters kept at home. Daughters are married off at an early age, as if they are a burden to be shed. Girl fetuses are aborted.

These are problems that laws alone cannot solve. The underlying deeply embedded cultural norms that support these practices must be changed. But before this can be done, it is imperative that cultural issues move from the margin of international law to the center. It is imperative that violations of women’s rights in the name of authentic national culture be viewed for what they are: human rights violations that cannot be justified by using culture as a shield. And it is also imperative to recognize that cultural norms and practices are not static but rather fluid. They have changed in the past and can change now and equally important, can be purposefully changed. The Grameen Bank, for example, founded by Nobel Peace winner Mohammed Yunus, has for years engaged in micro lending to poor women in the developing world. In addition to the financial dimensions of micro lending, there is also a social development agenda. The Bank does not require the usual safeguards that conventional banks require before lending, such as collateral and a good credit history. But it does require that borrowers, most of whom are poor women, commit to attend consciousness-raising meetings and to abide by 16 decisions, many of which have cultural dimensions. For example, one of the 16 Decisions is “We shall not take any dowry at our sons’ weddings, neither shall we give any dowry at our daughters’ weddings. We shall keep our centre free from the curse of dowry. We shall not practice child marriage.” Given the fact that a woman is killed every hour in India over dowries, dowry is a significant problem that Grameen is addressing through deliberate culture change.

Cultural norms that impede the human capability and voice of any marginalized person can and should be changed. Many of the poor and marginalized in the world today are women. The Convention of the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women takes both a legal and cultural approach to this problem. It urges ratifying states to enact the necessary laws but also notes that “a change in the traditional role of men as well as the role of women in society and in the family is needed to achieve full equality between men and women.” CEDAW then obligates state parties to take all appropriate measures “[t]o modify the social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices and customary and all other practices which are based on the idea of the inferiority or the superiority of either the sexes or on stereotyped roles for men and women…”

Whether in Afghanistan or elsewhere, women matter. International law cannot rely on treaties and legislation alone to ensure equality of women. It must also focus on the cultural norms that thwart women’s capability and reject any claims that culture change is illegitimate or inauthentic.

Featured image credit: Afghanistan, by Ricardo’s Photography. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Culture change for women in Afghanistan appeared first on OUPblog.

July 31, 2016

How the Iraq Inquiry failed to follow the money

In 2007, I published an article that sought to show in detail how the Iraqi economy had been opened up to allow the transformation of the economy and the routine corruption that enabled a range of private profit-making companies to exploit the post-invasion economy. The article argued that the illegal war of aggression waged by a ‘coalition’ headed by George Bush and Tony Blair was tied to a series of subsequent crimes of pillage and occupation. These included the transformation of the economy and the political system that was explicitly illegal under the terms of the Geneva and Hague Convention; and the mobilisation of political and economic instruments to ‘liberate’ the oil. The recently published Chilcot Report recognizes this corruption – and indeed UK joint legal responsibility for the corruption – and yet the evidence for it has been buried.

A key focus was what has subsequently been described by one British administrator as the “free money” that the country was awash with in the first year of occupation. Just weeks after the invasion, UN Security Council Resolution 1483 established the Development Fund for Iraq (DFI). The Resolution permitted the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) to spend this revenue on the reconstruction of the Iraqi economy, as long as it was “audited by independent public accountants approved by the International Advisory and Monitoring Board.”

DFI revenue was available to the CPA immediately, in the form of $100,000 bundles of $100 dollar bills, shrink wrapped in $1.6m ‘cashpaks.’ Pallets of cashpaks were flown into Baghdad direct from the US Federal Reserve Bank. The CPA held a proportion of this cash in the basement of its premises in Baghdad Republican Palace, famously in an unlocked room. One consequence of the use of cash payments and transfers was that the CPA transactions left no paper trail and therefore they remained relatively invisible.

At the time, a report by the Open Society Institute noted that around 85% of the contracts over $5 million paid for Iraqi oil revenue and disbursed by the CPA for ‘reconstruction’, went to US and UK firms. Just 2% of those contracts went to Iraqi firms. The Chilcot Report notes that by the end of the CPA’s first year of occupation, there were over 60 UK companies working in Iraq on contracts worth an estimated total of US$2.6 billion.

The UK government played a key role in the financial mechanisms that were so corrupted.

Showing a very explicit disdain for UN Security Council Resolution 1483, disbursal of DFI revenue was conducted with little or no adequate system of monitoring or accounting. The CPA kept no list of companies it issued contracts to. In addition to the discrepancies noted above, a report by the International Advisory and Monitoring Board (IMAB) found evidence of incomplete DFI accounting records; untimely recording, reporting, reconciliation and follow-up of spending by Iraqi ministries; incomplete records maintained by US agencies, including disbursements that were not recorded in the Iraqi budget; lack of documented justification for limited competition for contracts at the Iraqi ministries; possible misappropriation of oil revenues; and significant difficulties in ensuring completeness and accuracy of Iraqi budgets and controls over expenditures. Essentially the CPA enabled the reconstruction economy to exist without reference to international conventions of auditing and legal scrutiny, or its UN mandate.

The Chilcot Report is of course, primarily concerned with the role of the British government. Yet when it considers the role of British officials in facilitating the corruption of the reconstruction economy, it displays remarkable cunning. In the summary of the Report it notes: “The resolution’s [UNSCR 1483] designation of the US and UK as joint Occupying Powers did not reflect the reality of the Occupation. The UK contribution to the CPA’s effort was much smaller than that of the US and was particularly concerned with Basra.”

If this appears on the surface to be an unremarkable statement, it is drawing a remarkable conclusion: that the UK’s legal responsibility could not be really taken seriously since the UK’s role was “smaller.” Actually, the UK government played a key role in the financial mechanisms that were so corrupted.

Buried deeper in the Report there is evidence that a whole host of British officials and politicians were acutely aware of their responsibilities under international law, not least in relation to the Geneva and Hague conventions. The most senior British civil servant at the CPA, Jeremy Greenstock, recalls “a lot of cash was going round in suitcases…not all of which was accounted for.” It is an assertion that passes without comment in the Report. The next most senior British civil servant Andy Bearpark, when reflecting on the way the oil money was audited, said in his evidence “the IAMB, the International Accountability something or other… was the international body set up to monitor those funds, but that body never met until, I think, January 2004, by which time we had spent most of it.”

So it seems the British government cannot plausibly claim that it was unaware of its legal responsibility for the corruption of the reconstruction economy, or plausibly claim that it was powerless to do anything about it. Yet the Chilcot Report only mentions in passing the way that Iraqi oil money was disbursed in a way that fuelled endemic corruption. It recognises the corruption – and indeed UK joint legal responsibility for the corruption – without considering it to be particularly important. Although the evidence was available to the Iraq Inquiry it has simply been buried.

There can be no doubt, if Chilcot had followed the oil money he would have exposed how it was, quite literally, carried off in bags, under the watch of British government officials and British politicians.

Featured image credit: Soldiers Iraq camoflage by AngieJohnston. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How the Iraq Inquiry failed to follow the money appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about Milton Friedman? [quiz]

Milton Friedman is regarded as one of the most prominent economists of the twentieth century, contributing to both economic theory and policy. 31st July is his birthday, and this year marks 10 years since his death, and 40 years since he won the Nobel Prize for Economics for his contributions to consumption analysis and to monetary theory and history. Friedman was well-known for his publications such as ‘Capitalism and Freedom’, as well as advocating policies such as schools vouchers and floating exchange rates. See how much you know about Friedman by taking this quiz!

Quiz image credit: Portrait of Milton Friedman by The Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Money by Pictures of Money. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How much do you know about Milton Friedman? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: René Descartes

This August, the OUP Philosophy team honors René Descartes (1596–1650) as their Philosopher of the Month. Called “The Father of Modern Philosophy” by Hegel, Descartes led the seventeenth-century European intellectual revolution which laid down the philosophical foundations for the modern scientific age. His philosophical masterpiece, the Meditations on First Philosophy, appeared in Latin in 1641, and his Principles of Philosophy, a comprehensive statement of his philosophical and scientific theories, also in Latin, in 1644.

Born in La Haye, France, Descartes was educated at the Jesuit College of La Flèche and at the University of Poitiers. Much of Descartes’s early work as a “philosopher’ was what we now call scientific. The World, composed in the early 1630s, explored physics and cosmology, but Descartes cautiously withdrew it from publication in 1633 after the condemnation of Galileo by the Roman Inquisition for his heliocentric hypothesis (which Descartes too supported).In the Discourse on Method, a popular introduction to his philosophy, Descartes developed his celebrated method of doubt. By doubting all his ideas, he reached one unquestionable proposition: “I am thinking”, and from this that he existed: cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”).

Developing the theory later known as Cartesian dualism, Descartes maintains that there are two different kinds of substance: physical, or that which has length, breadth, and depth and can therefore be measured and divided—and thinking substance, which is indivisible. Mental phenomena, for Descartes, have no place in the quantifiable world of physics, but have an autonomous, separate status. Fascinated by the problems of ascertaining natural knowledge, Descartes’s metaphysics can be seen as an attempt to make a mathematical physics possible while paying tribute to traditional metaphysical and theological concerns like the existence of God and the immateriality of the soul.

His later works develop the ideas of the Discourse. The Meditations is a work of pure philosophy, and attempts to establish more firmly the metaphysics of the Discourse, in particular the existence of God and the mind‐matter distinction. The Principles is Descartes’s fullest account of his philosophy, devoted to metaphysics, physical science, and cosmology. The work was designed to replace existing school manuals, declaring that all people are capable of philosophy.

Although the structure of Descartes’s epistemology, theory of mind, and theory of matter have been rejected many times, their exposure of the hardest issues, their exemplary clarity, and even their initial plausibility, all make him the central point of reference for modern philosophy.

Featured image: photo of Chateau de Chenonceau – Indre-et-Loire, France by Ra-smit. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Philosopher of the month: René Descartes appeared first on OUPblog.

July 30, 2016

Teaching teamwork

The capacity to work in teams is a vital skill that undergraduate and graduate students need to learn in order to succeed in their professional careers and personal lives. While teamwork is often part of the curriculum in elementary and secondary schools, undergraduate and graduate education is often directed at individual effort and testing that emphasizes solitary performance.

I think we can improve undergraduate and graduate students’ educational experiences by giving them the benefit of working in teams. This can be implemented in short-term (two-hour to two-week) or longer term (2-12 week) projects. I believe that working on a larger project with 2-4 other students, for at least 15-35% of their coursework in several courses, would build essential professional and personal skills. I agree that it is easier to plan and execute team projects in smaller graduate courses than larger undergraduate courses.

Unfortunately, many faculty members were trained through lecture, individual homework, and strictly solitary testing. They have weak teamwork skills and are little inclined to teach teamwork. In fact, they have many fears that increase their resistance. Some believe that teamwork takes extra effort for faculty or that teams naturally lead to one person doing most of the work.

Teamwork projects may require fresh thinking by faculty members, but it may be easier to supervise and grade ten teams of four students, than to mentor and grade 40 individuals. Moreover, well-designed teamwork projects could lead to published papers or start-up companies in which faculty are included as co-authors or advisers. In my best semester, five of the seven teams in my graduate course on information visualization produced a final report that led to a publication in a refereed journal or conference.

Another possible payoff is that teamwork courses may create more engaged students with higher student retention rates. Of course teams can run into difficulties and conflict among students. These are teachable moments when students can learn lessons that will help them in their professional and personal lives. These difficulties and conflicts may be more visible than individual students failing or dropping out, but I think they are a preferable alternative.

So if faculty members are ready to move towards teaching with team projects, there are some key decisions to be made. Sometimes two-person teams are natural, but larger teams of 3-5 allow more ambitious projects, while increasing the complexity. I’ve also run projects where the entire class acts as a team to produce a project such as the Encyclopedia of Virtual Environments (EVE), in which the 20 students wrote about 100 web-based articles defining the topic. Colleagues have told me about their teamwork projects that had their French students create an online newspaper for French alumni describing campus sports events or a timeline of the European philosophical movements leading up to the framing of the US Constitution.

Image Credit: Students collaborating at Albany Senior High School in New Zealand by Mosborne01. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: Students collaborating at Albany Senior High School in New Zealand by Mosborne01. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Team formation: I have moved to assigning team membership (rather than allow self-formation) using a randomization strategy, which is recommended in the literature. This helps ensure diversity among the team members, speeds the process of getting teams started, and eliminates the problem of some students having a hard time finding a team to join.

Project design (student-driven): Well-designed team projects take on more ambitious efforts, giving students the chance to learn how to deal with a larger goal. I prefer student designed projects with an outside mentor, where the goal is to produce an inspirational pilot project that benefits someone outside the classroom and survives beyond the semester. I’ve had student teams work on software to schedule the campus bus route or support a local organization that brings hundreds of foreign students for summer visits in people’s homes. Other teams helped a marketing company to assess consumer behavior in a nearby shopping mall or an internet provider to develop a network security monitor. Two teams proposed novel visualizations for the monthly jobs report of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, which they presented to the Commissioner and her staff. I give a single grade to the team, but do require that their report includes a credits section in which the role of each person is described.

Project design (faculty-driven): Another approach is for the teacher to design the team projects, which might be the same ones for every team. With a four-person team, distinct roles can be assigned to each person, so it becomes easier to grade students individually. Just getting students to talk together, resolve differences, agree to schedules, etc. gives them valuable skills.

Milestones: Especially in longer projects, there should be deliverables every week, e.g. initial proposal, first designs, test cases, mid-course report, preliminary report, and final report.

Deliverables: With teams there can be multiple deliverables, e.g. in my graduate information visualization course, students produce a full conference paper, 3-5 minute YouTube video, working demo, and slide deck & presentation.

Teamwork strategies: For short-term teams (a few weeks to a semester), simple strategies are probably best. I use: (1) “Something small soon,” which asks students to make small efforts that validate concepts before committing greater energy and (2) “Who does what by when,” which clarifies responsibilities on an hourly basis, such as “If Sam and I do the draft by 6pm Tuesday, will Jose and Marie give us feedback by noon on Wednesday?” Teamwork does not require any meetings at all; it is a management strategy to coordinate work among team members.

Critiques and revisions: I ask students to post their preliminary reports on the class’s shared website two weeks before the end of the semester. Then students sign up to read and critique one of the reports, which they send to me and the report authors. They write one paragraph about what they learned and liked, then as much as constructive suggestions for improvements to the report’s overall structure, to proposed references and improved figures, to grammar and spelling fixes. When students realize that their work will be read by other students they are likely to be more careful. When students read another team’s project report, they reflect on their own project report, possibly seeing ways to improve it. I grade the critiques which can be 3-6% of their final grade. My goal is to help every team to improve the quality of their work. Sometimes the process of preparing their preliminary reports early and then revising does much to improve quality.

Concerns: I know that some faculty members worry that one person in a team will do the majority of the work, but if projects are ambitious enough then that possibility is reduced. Grading remains an issue that each faculty member has to decide on. I find that having students include a credits box in their final report helps, but other instructors require peer rating/reporting for team members.

In summary, anything novel takes some thinking, but embracing team projects could substantially improve education programs, engage more marginal students, and improve student retention rates. Learning to use teamwork tools such as email, videoconferencing, and shared documents provides students with valuable skills. Working in teams can be fun for students and satisfying for teachers.

Featured image credit: Harvard Business School classroom by HBS 1908. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Teaching teamwork appeared first on OUPblog.

What would Shakespeare drive?

Imagine a Hollywood film about the Iraq War in which a scene at a clandestine Al-Qaeda compound featuring a cabal of insurgents abruptly cuts to a truck-stop off the New Jersey Turnpike. A group of disgruntled truckers huddle around their rigs cursing the price of gas. An uncannily similar coup de thèâtre occurs in an overlooked episode in 1 Henry IV. From the rebel camp where Hotspur has hatched his treasonous revolt, the action shifts to a roadside inn outside London, where we eavesdrop on a conversation between two carriers.

Second Carrier: Peas and beans are as dank here as a dog, and that is the next way to give poor jades the bots. This house is turned upside down since Robin Ostler died.

First Carrier: Poor fellow never joyed since the price of oats rose; it was the death of him.

This curious exchange is more than just a tour de force display of Shakespeare’s mastery of working class argot. As a key ingredient in fodder, oats were in effect the petrol of the early modern world, and a horse’s daily ration of a peck per day was roughly equivalent to nine litres. As demand for travel grew, an increasing proportion of the nations’ arable land had to be diverted for oats cultivation. Oats grow well in dank soil, and were thus the major crop in places such as the Peak District, the Staffordshire moorlands, the Yorkshire dales, parts of Wales, West Morland, Northumberland, and Scotland—the very counties in revolt in Shakespeare’s two Henry IV plays. Meagre harvests of this crop would breed unrest in the north, whilst a northern rebellion would inevitably catapult the price of oats skyward.

The affordability of oats was also subject to vicissitudes of the British climate. During the “Little Ice Age,” Britain experienced three dismal harvests in the mid-1590s. As a consequence, the already exorbitant price of oats doubled in 1596, skyrocketing to a rate eleven times what it had fetched at the start of the century, a staggering eighty-two per cent above the norm. In fact in 1596 it hit the highest price ever recorded for oats in England in a two hundred year span between 1450 and 1649. Peas and beans—two other fodder ingredients mentioned by Shakespeare’s carriers—also soared to unprecedented levels at this time. 1 Henry IV was written in late 1596 or early 1597, in the midst of what might be considered the greatest fuel crisis in early modern English history.

Viewed under these conditions, the equestrian imagery in 1 Henry IV takes on a new significance, as does the fact that two of the main characters misuse horses. In the two plus hours’ “traffic” of the play, the aptly named Hotspur travels from the Scottish border to Windsor to Northumberland to Wales: a journey of over a thousand miles. At Shrewsbury, he commits the tactical error of engaging in battle with “journey-bated horses” (4.3.28). His rebellion fails because he is oblivious to the physical suffering he causes and the energy he consumes by over-exerting his horses.

Desidia (Sloth), 1557 by Pieter Bruegel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Desidia (Sloth), 1557 by Pieter Bruegel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.By the end of the sixteenth century, the art of equestrian manège embodied by Hotspur was already becoming an anachronism, as the nobility gradually transformed itself from a warrior class into a leisure class. Throughout the early modern period the horse underwent a corresponding transformation from a weapon of war to a means of personal transport. The character in 1 Henry IV who most obviously reflects this transformation is Falstaff. During the Gad’s Hill robbery, Poins plays a practical joke on the fat knight the importance of which has not been given the attention it deserves: he steals his horse. The “uncolted” Falstaff seems to parody Richard III’s outburst in a line that should be equally notorious: “Give me my horse, you rogues, give me my horse, and be hanged!” (2.2.29-30). Accustomed to riding everywhere, Falstaff underscores his distress at having to walk by punningly protesting that the robbery was “so forward and afoot too” (2.2.46-47). The play also comments on how Falstaff’s massive girth increases the burden of his mount. Among the colourful insults hurled at Falstaff “horse-back-breaker” (2.5.246) serves as a retrospective justification of Poin’s gag. Whereas the travellers he robs decide to walk to “ease” their horses’ legs (2.2.79), Falstaff thinks only of his own discomfort: “I’ll not bear my flesh so far afoot again for all the coin in thy father’s exchequer” (2.3.35-36). The verb “bear” here is highly suggestive. It bespeaks Falstaff’s centaurian consciousness of his own body as both vehicle and rider. In a culture where vehicular travel has become the norm, walking comes to be perceived as onerous. Falstaff, the play insinuates, has not grown fat on sack alone. His “uncolting” is not simply a ploy to avoid bringing horses on stage or a comment on the obsolescence of chivalry. It is a theatre of punishment directed at environmentally irresponsible behaviour that was aggravating an Elizabethan energy crisis.

In Sonnet 44 Shakespeare voices a wistful fantasy that humans possessed the power of teleportation––a capacity to leap through space instantaneously with no other fuel than thought. The inability of our body to do this is a source of melancholy for Shakespeare as it is for the environmentally conscious today. The remorse the spur-clad Shakespeare expresses in Sonnet 50 for causing his horse to groan may not be exactly similar to that which prompts academics to purchase carbon offsets for travelling to professional conferences, but his works reminds us–with its homophonic pun on travail–that travel was not and should not be easy. In an era when transportation took place on the back of sentient creatures–what if our cars moaned in pain each time we stepped on the accelerator?–and was fuelled by the sweat of animals and local farmers who grew their food, the energy required to generate such horse-power could not be hidden under the hood. Although in the symbolic calculus of the Henriad, medieval chivalry dies with Hotspur, we are, nonetheless, committing the same mistake in the post-chivalric era of the automobile. We are all Hotspur now.

The post What would Shakespeare drive? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 29, 2016

How do performance-enhancing drugs affect athletes?

Performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) are drugs that improve active performance in humans, known colloquially in sports as ‘doping’.

Perhaps the most famous abuser of PEDs to date is Lance Armstrong, a seven-time Tour de France champion, who in 2013 confessed to using performance-enhancing drugs during his cycling career, and was stripped of the seven Tour de France titles he won from 1999 to 2005. More recently, Maria Sharapova has tested positive for Meldonium, an anti-ischamic drug used to treat neurological disorders. This has resulted in her ban from tennis for two years, including the Olympic Games.

The use of performance-enhancing drugs in sports can be traced back as far as the 8th century CE Olympic Games when Greek Olympians are believed to have eaten sheep testicles to boost energy levels.

Goldman’s Dilemma

Goldman’s Dilemma was posed to elite athletes by physician and author of “Death in the Locker Room”, Robert Goldman. He asked athletes whether they would take a drug that would guarantee them overwhelming success in sport, but would cause them to die after five years. He found that approximately half of the athletes stated that they would take the drug.

In the United States, there are an estimated three million anabolic-androgenic users of whom 60% are non-competitive recreational bodybuilders or non-athletes, who use these drugs for cosmetic purposes. The most recent data from the British Crime Survey 2010 estimates that in the United Kingdom 226,000 people in the 16-59 age group admitted to having used anabolic steroids, with 19,000 using them in the past month. The figures are likely to be a gross under estimation. PED misuse is not unique to adults and steroid abuse prevalence has also been reported in teenagers.

Image credit: Tennis court by tenisenelatlantic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: Tennis court by tenisenelatlantic. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.So what are the implications of PEDs – both on professional athletes and amateurs?

The big players

Anabolic steroids

Anabolic steroids are available commercially. They are popular with sprinters, weight lifters, and body builders. They are similar in structure to the male sex hormone (testosterone) and therefore they enhance male reproductive and secondary sex characteristics, allowing athletes to train harder and longer. In addition, they increase muscle mass and strength.

The main systems affected are the secondary sex characteristics, the heart, and the liver. In men, anabolic steroids may interfere with normal sex function, resulting in baldness, infertility, and gynaecomastia. In women, it may cause male characteristics to develop. There is an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes. Users are also prone to dependence and behavioral outbursts also known as “roid rage”.

Protein hormones: human growth hormone (HGH), insulin like growth factor (IGF-1), and insulin

HGH is produced naturally by the body and is important for growth and development in adolescence. It stimulates an increase in muscle mass and bone strength, and reduces body fat. It is a popular PED as it is difficult to detect. An artificially increased level of this hormone is detrimental. HGH is associated with acromegaly and enlargement of organs such as the kidneys, liver, and tongue, as well as heart disease, diabetes mellitus, impotence and osteoporosis.

IGF-1 stimulates protein and bone synthesis, and has a similar side effect profile to HGH.

Insulin is important in the breakdown of carbohydrates, fat, and protein and can be used in combination with anabolic steroids or HGH to promote muscle mass by further stimulating growth. High dose insulin can lead to hypoglycaemia, nausea, shaking, and weakness, which may then progress to coma and death.

Erythropoietin (EPO) and blood doping

These PEDs are used to increase delivery of oxygen to exercising tissues. Recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO) is a hormone normally secreted from the kidneys. It is popular with endurance athletes, such as cyclists, and marathon runners. EPO stimulates bone marrow to increase the number of red blood cells in the body. This increases oxygen carriage by as much as 7-10%. It can be tested for in the blood and urine, but is removed from the body within a short time making detection difficult.

The increase in red blood cells from use of these PEDs leads to sludging of blood through blood vessels. The heart has to work harder, which increases the risk of a heart attack. In the brain, sludging reduces blood flow, significantly increasing the risk of a stroke. In addition, users may develop a reaction to rHuEPO and it has been associated with sudden death during sleep in a number of pro cyclists.

Blood doping is the practice of infusing whole blood into an athlete. It has a similar effect to training at high altitude and is also popular with endurance athletes. Risks are the same for non-athletic blood transfusion patients, in particular the risk of acquired viral infections and blood volume overload. There is currently no guaranteed way to detect blood doping.

The new kids on the block

New undetectable forms of erythropoietin, genetic doping, and xenon

There are a number of different forms of erythropoietin, EPO-alpha, beta, delta, omega, and zeta are the most common in clinical use. EPO Z (Zeta), currently undetectable in urine, was patented in Italy by Aifa, an Italian medicines agency, in September 2010. The Chinese have also manufactured an undetectable form of EPO.

Gene therapy, usually used to treat diseases, is also being utilized by athletes in genetic doping. This technology makes use of synthetic substances to manipulate the muscle building gene to enhance performance.

Xenon is a noble gas commonly used as an anaesthetic agent, but in sports its use has been associated with endurance athletes. Xenon binds to a specific region of the DNA and boosts erythropoietin levels. It first came to light in the 2014 Winter Olympics when it was revealed that Russian skiers were using it to increase the O2-carrying capacity of their blood.

Recent events have highlighted the extent of PED use in sport. To keep doping in check, we may have to resort to severe measures, such as with the expulsion of the Russian team from the Brazilian Olympics, 2016. However, this does seem unfair to those athletes who do not use PEDs and train hard.

With the drive for faster times and the demands placed on athletes for higher placement, however, I think the future will lead to cleaner, undetectable PEDs rather than cleaner players.

Featured image credit: Twilight cyclists by weesun. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How do performance-enhancing drugs affect athletes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oral history for youth in the age of #BlackLivesMatter

The #OHMATakeover of the OHR blog comes to a close as Andrew Viñales discusses the benefits of youth listening to activists in their communities. Thanks for following along as we invited our East Coast colleagues to shake things up a little, and come back in August for a return to our regularly scheduled program. For more from Columbia’s oral history program, visit them online or follow their blog.

As students in Columbia University’s OHMA program we are often urged to consider Oral History projects that not only serve to archive interviews for future use, but that “do something.” Indeed, many in my fellow cohort, myself included, have participated in community organizing, activism, and pushing for social change. On Thursday 24 March 2016, Paul Ortiz presented his talk “Oral History in the age of Black Lives Matter” as part of the OHMA workshop series. In the talk, he presented much of the work he and his students at the University of Florida are conducting, within the frame of the current political climate. He says what is special about this political climate is that young people, particularly students, are asking if they see a place for themselves in the world. I related heavily to this as a young student also interested in using oral history for social change. Ortiz provided many examples of how he and his students have used oral history to not only document the lives of people fighting for social justice, but also as a tool to inspire young people to act. He gave an example of his students being connected to former members of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the civil rights movements. Many of his students maintained contact with these civil rights veterans as they pursued their own activism and community organizing.

I was inspired to consider the possibilities of experienced activists and community organizers participating in public oral histories with young folks. This is already being done with the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. As part of their Mississippi Freedom Project they have facilitated interviews with residents of the Mississippi Delta, and veterans of the civil rights movement. One of the most impressive outcomes of this project was the community investment in McComb, Mississippi, in which high school students were able to experience the history of the SNCC and Freedom Summer by listening to folks who lived through it. Not only was this a more tangible way to learn the history, but it was a chance for high school students to draw connections with what is going on in the world around them. If they could see people who were their age in the 1960s actively participating in civil disobedience, planning actions and celebrating victories, perhaps some would be moved to participate in current struggles. In fact, as Ortiz mentioned in his talk, some of the participants in that program went back to Florida and founded their local chapter of the Dream Defenders!

What is special about this political climate is that young people, particularly students, are asking if they see a place for themselves in the world.

As for myself, a young Afro-Latinx who grew up in the Bronx and attended high school on the campus of Hostos Community College, I was always surrounded by active participants in social movements. I knew I went to school in a place that existed because of activism including the Hostos Take Over, but I would have benefitted from listening to the these veterans. Although I’m sure not all students would be too pleased to attend a lecture, assembly or class in which an interviewer takes a life history approach to get a narrator’s story, I can imagine a wealth of creativity to make this an active and participatory oral history project.

“Black Lives Matter” by Gerry Lauzon, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Black Lives Matter” by Gerry Lauzon, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.A great example of a community based youth program using oral history is the McComb Legacies Project in McComb, Mississippi which collaborates regularly with the University of Florida’s Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. According to the McComb Legacies Project website they aim to give youth an “opportunity to learn about, document, and share their local civil rights movement and labor history” and with this history they urge the students to “examine and take action to improve their world today.” In essence, they use oral history to not only archive the important history of the civil rights movement, but to inspire the youth to participate in social movements relevant to them. The best part is the participants seem to enjoy it! Students were even able to work with the Urban School of San Francisco, and the Telling their Stories Oral History Archives Project, to film and transcribe interviews they conducted with McComb veterans of the civil rights movement. For an example of the work McComb students have done, please see their interview with Ms. Jacqueline Byrd Martin, note that in “Part 4” Ms. Martin describes her experiences being arrested and traveling around the country to bring light to what was going on in her Mississippi community.

The McComb Legacies Project, and the Telling their Stories Oral History Archives Project have developed what I believe could be a great tool for oral historians to not only inform students of important local history, but as a way for them to understand that the civil rights movement has never ended, that social justice movements always build from movements of the past. As an oral historian doing work in the age of Black Lives Matter, I believe this approach can be a crucial tool in getting people to contextualize the world around them, but also encourage them to act!

This post was originally published on the OHMA blog. Add your voice the conversation by chiming into the discussion in the comments below, or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Photograph of Butler Library, Columbia University’s largest single library.” by JSquish, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oral history for youth in the age of #BlackLivesMatter appeared first on OUPblog.

Violent sports: the “most perfect of contests”?

The “most perfect of contests” is the praise given to pankration, the ancient forerunner of modern “Mixed Martial Arts” (MMA) which employs a brutal blend of boxing, wrestling, judo, and karate. This acclaim is found in an inscription from Asia Minor (Aphrodisias) from the 3rd century CE (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum, 1984). The big money prize for pankration in this period suggests that the event was also the most popular. Another inscription from the same city lists the cash prize as greater than that for boxing or wrestling (3000 denarii vs. 2000 for the other slightly less violent events) and much more than the 1200 denarii for the traditionally esteemed 200 metre footrace, the stadion. Finger-breaking and even strangulation to death were known to occur in such contests. Greek ‘combat sports’ (boxing, wrestling and pankration) held a prominent place among the games from the earliest period, evident from the intense drama of boxing matches in Homer’s Iliad 23 and Odyssey 18 (about 700 BCE).

Violent sports like American football, ice hockey, rugby, boxing, and MMA are perennially among the most popular. Their status is a frightening indication of the flowering of violence in sports in the 21st century, booming to a level unknown since ancient Greece and Rome. In the ancient Mediterranean, the audiences both in the Greek East and in the Roman West mutually enjoyed Greek athletic contests and Roman spectacles. Roman chariot races were famous for their fatal collisions, and gladiatorial battles were also held in the chariot ‘circus’ venues, as well as in arenas, and even in Greek theaters throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The only concern of the populace was “bread and circuses,” according to Juvenal (Satire 10; ca. 100 CE), while the “circuses” included not only chariot races, but gladiator games and even Greek athletics. Greek athletic performances were regularly held in the western Mediterranean, especially in Italy [S. Remijsen. 2015. The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity]. Gladiatorial bouts in the eastern Roman empire were regularly given the Greek terms for boxing (pugmē and pukteuein) in inscriptions, a usage that points to the popular equation of gladiatorial bouts to combat sports. [L. Robert. 1940. Les gladiateurs dans l’Orient grec]. The audience cared little for what was Greek and what Roman; the brutality itself was the draw. Violent sports are to be sure evidenced in other historical cultures like Mesoamerica, Egypt, the Middle East, and East Asia, but none match the popularity and legacy of the Greco-Roman phenomena.

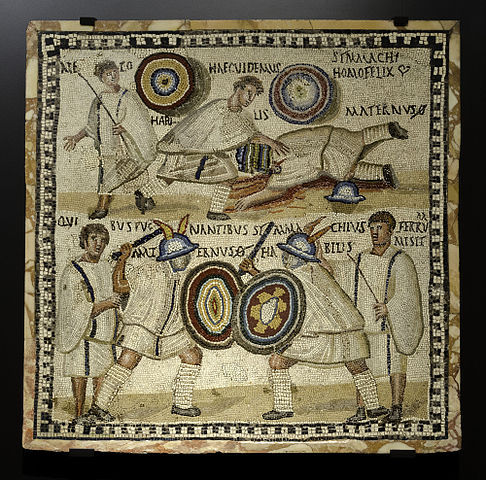

Gladiatorial mosaic from Mérida, Spain. Death of Maternus, killed by Symmachus. 3rd century CE. Photo by Ángel M. Felicísimo, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Gladiatorial mosaic from Mérida, Spain. Death of Maternus, killed by Symmachus. 3rd century CE. Photo by Ángel M. Felicísimo, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The reason for the lure of violence shared by our western ancient and modern cultures is a more complex question that has puzzled scholars. The ancient and modern cases all coincide with affluence among the elite who funded the expensive games, in antiquity with free admission. The spread of sports also occurs in cultures with numerous occasions for leisure among the general populace, namely religious festivals in antiquity and the free time enjoyed by a bigger middle class today.

These conditions partly explain the spread of public contests then and now. But they do not explain the passion to witness physical aggression. What we can establish is that the ancient contests were, with few exceptions, an almost exclusively male space for Greek and Roman participants and fans. This fact is perhaps not surprising in societies where the public presence of women was hugely limited by our standards. More amazing is that today’s sports have been maintained as a male enclave; Professor Cheryl Cooky of Purdue University has dubbed sport media outlets “‘mediated man caves’… a space where men can go and know it’s going to be by, for, and about men.”

In the last hundred years, and especially in the last half century, women have slowly been admitted to physical education, athletic training and participation in many sports. But the delay in admission is startling. It may be, unfortunately, that the contemporary inclusion of women in public sports is a gesture to social equity, not a response to public demand. Public interest measured by media presence and by the salaries of top women players indicates that most fans, male and female, prefer watching men compete. The example to the contrary is in Mixed Martial Arts where female combat athletes, most notably starting with Ronda Rousey (2.2. million followers) have gained a fandom. But this is marginalized in comparison with MMA fans for males. Women’s games are, for a minority of men (and for me), as exciting to watch as men’s. So why the discrepancy?

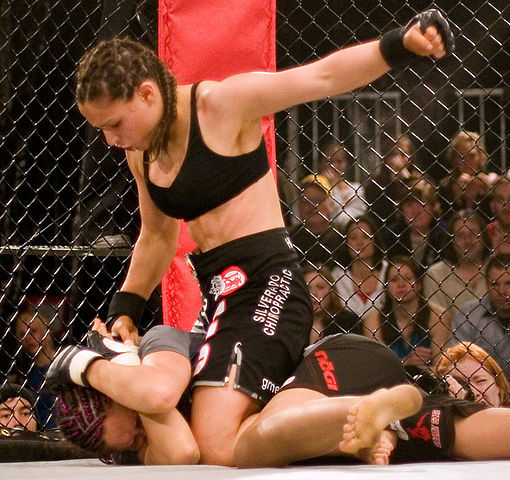

Gina Carano in full mount position performing ground and pound. Photo by Matthew Walsh. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Gina Carano in full mount position performing ground and pound. Photo by Matthew Walsh. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The image of sporting machismo has been long established in the past century, fed in part no doubt by testosterone and by the custom of the more heavily muscled gender that evolved for hunting and tribal fighting. Fitness is still crucial, but the aggressive expression of physical violence is ever less required in our mechanized society, far less required than among the Greeks and Romans. But when daily life places fewer demands for strong physical force for aggression or defense, there seems to be an even greater compulsion for men’s sporting spectacles today. Two reasons suggest themselves: the attempt of the male to re-claim physical esteem in the face of his shrinking value in the industrial and information ages, and the longing of fans to share in the honor and glory of the hero on the playing field, aided in the last half century by television and the internet.

The historical comparisons here suggest that it is culture more than nature that fosters violent games. In each society different social forces are at play, encouraging the wealthy and powerful to exploit the visceral lure of violence among men. Greek games offered male athletes a venue to obtain fame resembling that of military heroes, and to do it for the glory of the state as well as themselves. Romans forced male non-citizens to brutalize and kill one another with some promise of freedom or reward, but more self-interestedly to display the power of empire and to put on show to citizens their status above the outlaws. The flood of violent games today evidences no clear social benefit to the state. Yes, local municipalities fund sports programs, as do schools and universities. But the serious money for professional sports is in the hands of corporate conglomerates, e.g. NFL team revenues of over $9 billion per year, and the sale of Ultimate Fighting Championships for $4.2 billion in June 2016.

Professional teams and sporting associations of course thrive on the team or national loyalties of the fans, and provide entertainment in return, but the revenues are their main raison d’etre. Yes, pro-sports can inspire fitness among non-professionals, but the most popular non-pro sports are non-violent. The reality is that violent professional sports represent an anachronism of a brutal past to which our global era has not yet adapted. These sports are in effect a restoration of the bread-and-circus strategy of the Romans that pandered to the baser (and mainly male) instincts that are drawn to view violence. Modern concerns about the deleterious effects on the brain from concussions (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy) in US football and in boxing have heightened collective concerns about the tolerable limits of sanctioned violence. Surely we cannot say, as the Greeks did of pankration, that our violent sports are “the most perfect of contests.” Unless we realize their anachronism, we have missed an opportunity for more productive physical activity and for the better expenditures of such large sums.

Featured image credit: Boxers, side B from an Attic black-figure amphora of Panathenaic shape. Antimenes Painter, circa 520 BC. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Violent sports: the “most perfect of contests”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers