Oxford University Press's Blog, page 489

July 13, 2016

When Shakespeare’s plays call for music, what kind of sound should we imagine?

The following is an excerpt from ‘Music and the Stage in the Time of Shakespeare’, a chapter written by Ross Duffin that appears in the Oxford Handbook of the Age of Shakespeare. This passage looks at how music was used in Shakespeare’s plays and what it would have sounded like.

What instruments were used, either onstage or ‘in the pit’, to use modern parlance? There is evidence that the standard instrumental band for the theatre at this period evolved to be a very particular kind of ensemble that had its roots in the 1560s. Such an ensemble first gets mentioned in the play Jocasta, by George Gascoigne and Francis Kinwelmarsh, first acted at Grays Inn in 1566 and printed in Gascoigne’s A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres of 1573:

“First, before the beginning of the firste Acte, did sounde a dolefull and straunge noyse of violles, Cythren, Bandurion, and suche like…”

In fact, the bandurion (bandora, pandora, etc.) had reportedly been ‘invented’ by the London instrument-maker John Rose in 1562, so it was a new sound, and was a bass counterpart to the smaller, wire-strung cittern. The ‘suche like’ instruments in the band become clearer with subsequent reports. The cittern and bandora are related as plucked, wire-strung instruments, but the rest of the band was of more disparate character. That may be why Robert Laneham’s (or Langham’s) letter concerning music at the Entertainment for Elizabeth at Kenilworth Castle in 1575 refers to ‘sixe seuerall instruments’, meaning that they were mostly of different types.

Those six instruments first seem to have been named explicitly in the description of the music at the entertainment for Elizabeth at Elvetham in 1591:

“After this speech, the Fairy Queene and her maides daunced about the garland, singing a song of sixe partes, with the musicke of an exquisite consort, wherein was the Lute, Bandora, Base-violl, Citterne, Treble-violl, and Flute…”

So, this ‘ideal’ consort consisted of one bass and one treble bowed string instrument, a woodwind instrument, a flexible gut-strung plucked instrument with a wide range, and two wire-strung plucked instruments for texture and percussive effect. This is the basic plan and, though the ensemble is small, its textural resources are rich and substantial. But substitutions occur. Some musical sources assign the flute consort part to recorder, and some sources refer to vyalyn, or violan, instead of viol, suggesting that the treble bowed instrument might have been a violin as an alternative to the treble viol. The original German of the description given here of a pre-play concert at Blackfriars in 1602 uses ‘Geigen’, which I have translated as viols but which might just as well be rendered as ‘fiddles’, meaning generic bowed-string instruments:

“For a whole hour before the play began we heard a delightful consort of organs, lutes, pandoras, citterns, viols and flutes. When we were there, a boy with a warbling voice sang so charmingly to the accompaniment of a bass viol that with the possible exception of the nuns at Milan, we heard nothing to equal him on our journey.”

The inference of having the consort in the theatre is that, having performed before the play (such pre-play performances at some American festivals today are called ‘green shows’) they would stay and provide music during the production as well. In recent decades, mostly because of the influence of film underscoring, we have become accustomed to almost constant use of orchestral music, filling the silence, and manipulating the moods and expectations of the audience. As Julie Sanders says of the underscoring in Branagh’s Henry V: ‘Throughout this film the audience is highly conscious of the epic orchestration that underlines, and sometimes in terms of volume overlays, the events and exchanges being witnessed’. It is very clear, however, that, as important as music was, this kind of constant musical background was not part of the sound experience in late Renaissance theatre.

As Tiffany Stern notes, ‘no Shakespearean ghost’s entrance is flagged by sinister music — or by music of any kind — as would happen in a modern film’. Actors speaking without amplification could not compete with a musical ensemble, whether in an indoor or outdoor theatre, though it is possible that a lute or viol might occasionally continue through portions of dialogue. Moreover, without the ubiquity of recorded music that we enjoy today, music at that time was special— magical even— and its effect would have been diminished by constant presence even if that were possible for the musicians, which it was not. David Lindley, indeed, points out that, in contrast to the modern use of filmic underscoring, music in Shakespearean theatre was ‘always part of the world of the play itself, heard and responded to by the characters on-stage’.

Featured image credit: ‘Man drawing a lute’, by Albrecht Durer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post When Shakespeare’s plays call for music, what kind of sound should we imagine? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 12, 2016

Are Americans information junkies?

It would seem so obvious that Americans are information junkies. With 70 plus percent of the population over the age of 10 walking around with their smart phones—more computer than telephone—they often hold them in their hands so they can instantly keep up. E-books are popular, while the sale of hardcopy books continues to rise. The New York Times boasted in 2016 that it now had over a million online subscribers. A number close to that reads the Harvard Business Review.

But a junkie? We think of junkies as people addicted to something. Teenagers addicted to Facebook or to their video games, and the images of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton checking her e-mail seem to appear daily in the press. But what does history teach us?

It turns out Americans have been googling since the eighteenth century. Historians are learning more about what information Americans have consumed over the centuries and how. The original settlers in North America had high rates of literacy—well over half the adult population—and so were used to the idea that information was organized into logical groupings, such as about medicine, farming, or cooking, and that they were available in some common formats. These formats included broadsides, newspaper articles, pamphlets, and books. In the nineteenth century, they added electronic formats, such as telegrams and telephone conversations. Cheap printing costs and the invention of photography enhanced the collections of information.

Image credit: Phone by Richard Leeming. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Phone by Richard Leeming. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Americans had to be a practical people as they established their lives in the colonies and later young nation. So they developed the practice of looking up things in two ways. First, they searched for information that would allow them to solve a specific immediate problem, such as how to survey a property or how to care for a sick cow. Cookbooks based on North American ingredients began appearing in the late 1700s, books on how to care for children by the 1820s, and manuals on how to repair new machines within a few years of an invention. Books about “car diseases” became the stuff of modern life by 1910.

Second, they acquired the practice of informing pending decisions by examining facts. The U.S. Congress established the Post Office in the 1790s convinced that one could not exercise their civic responsibilities without being informed about economics, politics, and military affairs. The Post Office had to get newspapers to people. By the end of World War I, the nation was on a mission to keep children in school past eighth grade, increasingly to graduate from high school. By the end of the twentieth century, over a quarter of the nation’s adult population had gone to college, while today, analytics and “learning computers” are seeping into the routine work of managers in business and government.

Googling, which is the act of going to the Internet to look up a fact or how to do something, is the latest manifestation of Americans using almanacs, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and how-to publications, among others, to inform their actions and decisions.

The nation has always been willing to invest in these sources of information. First came the Post Office, then thousands of newspapers and magazines, such that almost every topic one can think of had its own publications by the start of the twentieth century, and today literally millions of websites. The American government invested in roads, canals, transportation technologies, even helped jumpstart the computer industry faster than anywhere else in the World, installation of satellites and the most spectacular infrastructure of all, made the initial investments in the Internet.

The nation could afford to google, too. The Second Industrial Revolution began in the United States in the 1840s and by the end of World War II Americans had the largest, wealthiest economy in the World. They had industrialized, created a network of over 2,000 colleges and universities, acquired more Nobel Prizes in sciences than any other nation, essentially created many of the information technologies we take for granted: telegraphy, telephones, television, PCs, of course Apple’s smart phone, among others. Historians will qualify these statements with reminders that similar developments were going on in other countries, but it seemed the Americans exploited them faster, earlier, or more extensively.

Why? Because they wanted access to information sooner, “just-in-time,” and wherever they were if at home, work, school, or in a bar settling a argument over who hit more home runs than Babe Ruth, or determining when was Nixon president.

Historians like to answer the same impatient question Americans often ask: “So what?” The question speaks to the relevance of a topic. In this case, the answer rests on the twin notions of people wanting to solve problems in a practical way and to inform their decisions, even simple ones such as where to go to dinner if it is Monday night and half the restaurants in town are closed. They are learning that seeking facts has remained both a remarkably consistent behavior dating back to the 1700s. It is a major feature of American culture. They are discovering that the thirst for information and its use are right up there with immigration, colonization of North America, creation of a democratic society, and in recent times, becoming a nation of cities, were the essential building blocks of American society.

So, are Americans information junkies? Possibly, but at a minimum they are extensive users of facts. Even my 7-year old grandson goes to the Internet to find out facts about Ninja characters or about how animals live in the wild. Are you an information junkie? What does that say about how you live and work?

Featured image credit: A farm worker traveling to California during the Great Depression of the 1930s studies a map—an important source of information for Americans in all periods—to look up instructions on how to get to his destination. Source: Public Domain from the U.S. Library of Congress.

The post Are Americans information junkies? appeared first on OUPblog.

Turning waste into resource: a win-win situation that should not be missed

Soon after the Flinstones’ cartoon period, formally called the Stone Age, humans started to use metals for constructing tools, weapons, or ornaments which tremendously boosted human development. Since then, metal utilization has been evolving and nowadays, metals are a central pillar for all kind of routine and technological uses. You can find aluminium in most of your pots and pans; copper as conductive material in wires or as heating sinks in computers, TV sets or disk drives; platinum in car catalysts to reduce air pollution; gold, silver, platinum, palladium, copper, tin, and zinc in cell phones. These are just a few examples of the extensive metal utilization to which society has succumbed. Look around you right now and try to picture your world without metals…difficult, right?

The metal mining industry needs to satisfy this increasing societal demand for metals. However, most of the high quality ores have been mined already. That leaves only ores with lower quality (low content of target metal and high content of undesired metals like arsenic) for future generations. This results in more metal-ores being processed and, therefore, a large amount of solid waste generated, around 20,000-25,000 megatons per year. This mining waste is often contaminated with high amounts of non-recovered metals. This represents a serious threat to the environment because many toxic metals easily mobilize upon contact with water.

Careless management of this solid waste in the past and present has resulted in formation and release of acidic water, contaminated with a wide range of toxic heavy metals, also known as acid mine drainage. This acidic water continuously threatens the health of many life-forms on earth including humans (for example via contamination of drinking water sources). Release of these hazardous waste streams by failure or absence of storage facilities has created big environmental problems in the last century, and continues to do so. We have recently witnessed terrible accidents related with mine waste storage failures. On 5 November 2015, a tailing dam containing iron ore failed, and around 60 million cubic meters of iron and other metals flowed into the Doce River. This destroyed the nearby village of Bento Rodrigues (Minas Gerais), killed 13 people, and caused huge environmental pollution. Additionally, over a hundred other tailing-related accidents took place in the last century. Local communities had to watch metal-coloured waters from mines flow into their pristine mountain streams on which they relied for drinking water and agriculture. Besides mine tailing failures, there were many other critical mine-associated problems all over the world. For instance, in South Africa, acid mine drainage affected the drinking water supply in 2012 with low-pH water contaminated with uranium. This led to an interrupted drinking water supply that lasted for months. With water stress already being a worldwide challenge, the water that still is available should be protected and not polluted with toxic metals.

Bento Rodrigues, Mariana, Minas Gerais. Photo by Rogério Alves/TV Senado. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Bento Rodrigues, Mariana, Minas Gerais. Photo by Rogério Alves/TV Senado. CC BY 2.0 via FlickrSurely many factors contributed to these tragedies, but there is a direct connection with the careless mismanagement of governments and companies that often operate in developing countries, far away from their administrative centres. In the Environmental Justice Atlas (filtered by “Mineral Ores and Building Materials Extractions”) we can visualise the amount of conflicts (protest and accidents) related with mine industries. We can also see the “Not In My Back Yard” effect; usually the biggest mining companies are from Australia/UK (BHP Billiton or Rio Tinto) or China (China Shenhua Energy) but most of the problems took place in Central and South America. Even when mining takes place in developed countries, the remoteness of metal affected areas still keeps it away from the top of the political agenda.

We have to face the fact that we need metals if we want to keep our standard of living or increase it in developing countries, so mining is just necessary, now and in the foreseeable future. But what is unacceptable is that our society keeps on ignoring the vast environmental and socio-economic problems that are a direct effect of mining activities. We are still in time to prevent new disasters by raising awareness and taking the right measures; this is the right and the duty that we have as citizens of our society.

Since most of the problems are legacies of past mining activities with huge ongoing impact on environment and society, we should demand that our governments find solutions, even if this means taking over the management of those wastes. Secondly, governmental bodies should force operating mining companies to stop offloading the global environmental costs of their activities. Thirdly, and most importantly, more sustainable mining and recovery of metals should be stimulated where metals get a sustainability certificate, just like hard wood.

It will take time to make the change, and it will require funding and other resources. The positive side about advocating for metal recovery is that it will even be economically beneficial for companies. As mentioned, after mining activities, a leachate with a mixture of heavy metals is generated. Usually, one specific mine focusses on one specific metal and the rest of the ore is considered waste and disposed of as such. But this toxic waste contains many metals that can be recovered and used in a sustainable way. A way to do it is using sulfate-reducing microorganisms, which are able to reduce sulfate and produce sulfide. The sulfide reacts with metals and forms metal sulfides. A peculiarity of metal sulfides is that different metals precipitate at different pH values (copper is very insoluble even at low pH while iron needs higher pH to precipitate). Therefore, if the metal-laden leachate is consequently treated at different pH values using sulfate-reducing microorganisms, we will precipitate selectively different metal sulfides. The metals in the form of sulfides are very stable and dense enough to be separated and reused again in smelters or other applications. Since many metals are valuable resources, the mining companies can use this metal recovery for economic benefit. There are numerous examples in scientific literature and on-going technological applications which have proven the successful implementation of microorganisms for treating metal wastes. In this way, not only do we focus on waste treatment, we also aim to avoid waste generation altogether by turning potential waste into resource. We can change mining practises by using microorganisms and we can decrease the hazards of mining waste storage, thereby respecting the planet where we and future generations have to live.

Since this sustainable technology is available and even economically attractive, we encourage innovation and application by the industry from the beginning of the design of their mines. For the cases where the economic benefit threshold is smaller, governments should implement adequate laws in order to prevent further unnecessary environmental accidents linked to human industrial activities. It is time for a change.

Featured image credit: View of the Tinto River, an acid rock drainage environment. The rust-brown color is due to dissolved ferric iron. The water column has a pH of around 2.3 and contains elevated concentrations of several other transition metals, including copper and zinc. Photo taken by Jose Luis Sanz. Used with permission from the author.

The post Turning waste into resource: a win-win situation that should not be missed appeared first on OUPblog.

Ready to explore the unknown

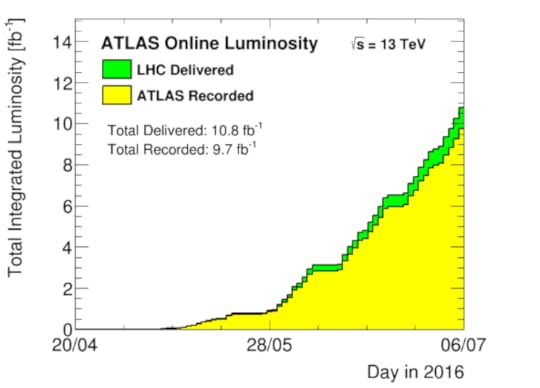

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN has already delivered more high energy data this year than it had in 2015. To put this in numbers, the LHC has produced 6.5 fb-1, compared to 4.2 fb-1 last year, where fb-1 represents one inverse femtobarn, the unit used to evaluate the data sample size. This was achieved in less than two months compared to five months of operation last year.

With this data at hand, and the projected 20-30 fb-1 by November, both the ATLAS and CMS experiments can now explore new territories and, among other things, cross-check the intriguing events they reported having found at the end of 2015. If this particular effect is confirmed, it would reveal the presence of a new particle with a mass of 750 GeV, six times the mass of the Higgs boson. Unfortunately, there was not enough data in 2015 to get a clear answer. The LHC had a slow restart last year following two years of major improvements to raise its energy reach. But if the current performance continues, the discovery potential will increase tremendously. All that is to say that everyone is keeping their fingers crossed.

The total amount of data delivered in 2016 at an energy of 13 TeV to the experiments by the LHC (blue graph) and recorded by the ATLAS experiment (yellow graph) as of 23 June. Public domain via ATLAS experiment.

The total amount of data delivered in 2016 at an energy of 13 TeV to the experiments by the LHC (blue graph) and recorded by the ATLAS experiment (yellow graph) as of 23 June. Public domain via ATLAS experiment.If any new particle were found, it would open the doors to bright new horizons in particle physics. Unlike the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, if the LHC experiments discover an anomaly or a new particle, it would bring a new understanding of the basic constituents of matter and how they interact. The Higgs boson was the last missing piece of the current theoretical model, called the Standard Model. This model can no longer accommodate new particles. However, it has been known for decades that this model is flawed, but so far, theorists have been unable to predict which theory should replace it, and experimentalists have failed to find the slightest concrete signs from a broader theory. We need new experimental evidence to move forward.

Although the new data is already being reconstructed and calibrated, it will remain “blinded” until close to 3 August, the opening date of the International Conference on High Energy Physics. This means that until then, the region where this new particle could be remains masked to prevent biasing the data reconstruction process. The same selection criteria that were used for last year’s data will then be applied to the new data. If a similar excess is still observed at 750 GeV in the 2016 data, the presence of a new particle will make no doubt.

Even if this particular excess turns out to be just a statistical fluctuation, which is always possible since physics obeys statistical laws, there is enough data to explore a wealth of possibilities. Everyone knows there is something beyond the Standard Model. But no one knows if we will luck out and at long last find the first evidence for it this summer. The good news though is that there is enough data at hand to explore new phenomena. Meanwhile, you can follow the LHC activities live or watch CMS and ATLAS data samples grow.

Featured image: Particles abstract glass by gr8effect. Public domain via Pixabay.

A version of this post originally appeared on Quantum Diaries.

The post Ready to explore the unknown appeared first on OUPblog.

The new jazz films (and their old models)

Recent months have seen the release of two movies about great jazz trumpeters from the 1950s and 60s: Miles Ahead (Don Cheadle, 2015) focusing on Miles Davis, and Born to Be Blue (Robert Budreau, 2015) focusing on Chet Baker (although Miles plays an important role in the latter too: his second cinematic revival in one year). The similarities don’t end there: both films are semi-fictional, homing in on a moment of crisis in their respective protagonists’ real lives and spinning a mostly fictional story around it. Likewise, both rely structurally on extensive flashbacks to tell their story. Both invented or enlarged a female character in a nod to a conventional monogamous redemptive love narrative. Both are slumming it in their graphic depiction of the destruction and misery wrought by drugs and the attendant crime. But perhaps the most significant parallel between the two films is the moment of crisis itself, showing their stars’ inability to produce anything more than squeals and grunts from their trumpets – in Davis’s case due largely to drug and alcohol abuse, in Baker’s to the loss of his front teeth in a drug-related mugging.

Miles Ahead and Born to Be Blue were preceded by Whiplash (Damien Chazelle, 2014), which likewise centres on jazz, although its narrative and setting are different. Casual cinema-goers may be forgiven for not being aware of the tradition these films respond to: the jazz film, a genre that is almost as old as film itself. Jazz and film were born at roughly the same time, both are the products of the modern age and quickly established themselves as the first quintessentially American art forms. No wonder, then, that they shared more than a passing fling, particularly during both their hey-day during the 1920 to 40s. Nevertheless, it could be argued that the jazz film comes into its own only once the music was overtaken by rock ‘n’ roll in terms of popular appeal and commercial success. The classics of the genre tend to feature tortured male geniuses, struggling with popular rejection or a creative crisis and alcohol or drug addiction while perfecting their craft. This type of narrative could not have much appeal as long as jazz had genuine mass appeal: by way of comparison, it is difficult to imagine teen idols from Elvis Presley to Justin Bieber in similar roles. Young Man with a Horn (Michael Curtiz, 1950), based loosely on trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke, created the mould, and many of the tropes present in Miles Ahead and Born to Be Blue more than sixty years later can be found here: the creative crisis, the battle with alcoholism, the woman whose love redeems the hero, the triumphant happy ending in which all the struggles are overcome (which the more recent films slightly undercut without eschewing it altogether). Like Young Man with a Horn, most jazz films are biopics in the widest sense, although many are based on fictional, not real-life musicians.

So why, when we’ve been waiting for so long – Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown (1999) was the most recent notable example – do three jazz films come along at once, when the music itself leads but a niche existence? This may indeed come as a surprise, particularly since, although there is no shortage of fine examples, not a single representative of the genre has really set the world alight. The reason for that may lie in the fact that, for all its attractions, jazz is remarkably resistant to being captured visually: it is a child of the gramophone and, somewhat paradoxically, prioritises live performance over recording, as epitomised in its most distinctive feature: improvisation. Thus, while it promises to reveal its secrets, the essence of the music always eludes the cinematographer’s grasp. Or rather, jazz’s potential is only revealed in films that aren’t about jazz at all: for instance, in no other film does Miles Davis’s music come to life like in Louis Malle’s Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (1958), where it accompanies Jeanne Moreau’s nocturnal wanderings through Paris (supposedly improvised by Miles to the images). Compared to this seemingly effortless lyricism, seeing a fictional Miles play his actual music, as in Miles Ahead, must always appear prosaic, even if it’s done with the conviction that Cheadle brings to his role.

It would appear as if it is the very marginality of jazz in today’s culture that makes it interesting for filmmakers again. Throughout its more than a hundred years of history, jazz has constantly renewed itself, from communal music-making, through commercial success to artistic and avant-garde status. Not coincidentally, it entered conservatoires, universities and museums as a respected art form only when it no longer rivalled rock ‘n’ roll and its successors in terms of sales, and its celebration in documentaries in film and television followed suit. It is its afterlife, a nostalgic memory, that is presented in film. Herein lies the single most significant difference between Miles Ahead and Born to Be Blue on one side and their swing era precursors on the other: while the latter featured a then current music, the former are firmly set in the past. To be fair, the final scene in Miles Ahead is set in the present and features many contemporary, including young, musicians, yet this does not seriously affect the elegiac, nostalgic tone of the film. Indeed, it is revealing that both movies rely so much on flashbacks, particularly in performance scenes: it is as if the music is doubly removed from the present; even in the past, it existed already only as a memory. Jazz movies, like the music itself, will be with us for a while yet, but let’s not deceive ourselves that this proves jazz’s vitality.

Featured image credit: “Paris Jazz” by Pascal Subtil. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The new jazz films (and their old models) appeared first on OUPblog.

July 11, 2016

Strategic narratives and war reading list

One area of research in Foreign Policy Analysis is the study of war. In contemporary wars strategic narratives provide a grid for interpreting the why, what and how of the conflict in persuading story lines to win over various audiences – both in the area of operations and at home. The point of departure for scholars utilizing the concept of strategic narrative is that people make sense of war by means of stories through which shared sense is achieved. A strategic narrative presents a construct in the form of a story to create a shared meaning of the past, present and future and to interpret a presented obstacle and a desired end-point. Political elites can utilize narratives strategically to tie together otherwise disjointed events and structure the responses of others to developing events by providing an interpretative structure through which the war can be understood.

The concept of narrative fits neatly within the increased focus of scholars to study the non-physical aspects of war in order to try to explain why “big nations lose small wars.” One of the central arguments in the debate is that, in contemporary wars that no longer end with a victory parade through the enemy’s capital, it is increasingly important to explain what success will look like to the local population, opponents, the international audience and the public at home, and to convince them of the official storyline. A key development in the debate was Lawrence Freedman’s introduction of narrative into strategic discourse in 2006. A vast body of literature on strategic narratives has been published since. We’ve created a reading list of books and journal articles so that you can read some of the latest ideas on the subject.

‘Fighting the War at Home: Strategic Narratives, Elite Responsiveness, and the Dutch Mission in Afghanistan, 2006–2010’ published in Foreign Policy Analysis. George Dimitriu and Beatrice de Graaf demonstrate that political elites can shape public opinion with regard to the use of force by strategic narratives. They suggest that narrative dominance (the combination of narratives and counternarratives) accounts for the waxing and waning of public support in the Netherlands for the Afghan mission. They explain the political consequences of dominating counternarratives and the ensuing drop of public consent by introducing the notion of “elite responsiveness”.

‘The War That Wasn’t There? Italy’s “Peace Mission” in Afghanistan, Strategic Narratives and Public Opinion’ published in Foreign Policy Analysis. Fabrizio Coticchia and Carolina De Simone assert that existing cultural perceptions of frames on strategic affairs are crucial to incorporate in the manufacturing of strategic narratives.

‘Public Contestation and Policy Resistance: Canada’s Oversized Military Commitment to Afghanistan’ published in Foreign Policy Analysis. Justin Massie shows that ineffective strategic narratives and strategic subcultures explain Canadian public opposition to Canada’s combat mission in Afghanistan. Second, elite consensus, and hence an unmobilized public opinion, best accounts for Ottawa’s policy unresponsiveness.

The Transformation of Strategic Affairs by Lawrence Freedman discusses the complexity of fighting irregular wars and the imperative role of compelling narratives in order to explain events convincingly to different audiences.

In War from the Ground up Emile Simpson argues that strategy doesn’t merely need to orchestrate military actions, but also construct the interpretive structure which gives them meaning and links them to the end of policy. The key is to match military actions and words so as to influence target audiences to a given strategic narrative.

In ‘Strategic Narratives, Public Opinion and War: Winning domestic support for the Afghan War’, Beatrice De Graaf, George Dimitriu and Jens Ringsmose (eds.) explore the way governments endeavoured to build and maintain public support for the war in Afghanistan, combining new theories on the origin and effects of strategic narratives with a collection of thirteen case studies on the effects of strategic narratives on the public opinion of the contributing countries on the Afghan War.

In Strategy, a History Lawrence Freedman traces the origin of strategy as a special kind of narrative. Since the 1960s and 1970s the idea has come into vogue that wars couldn’t be controlled by means of a central plan. Convergence has since grown around the idea that best strategic practice may consist of forming compelling strategic narratives of how to turn a developing situation into desirable outcome. Freedman notes that strategy is increasingly conceptualised as an interpretative framework and a constructed story in the future tense to give meaning to events.

‘The virtual dimension of contemporary insurgency and counterinsurgency’ published in Small Wars & Insurgencies. David Betz explains that the West is faltering in the ‘War of Ideas’ as their messages lack narrative coherence while their opponents and belligerents manufacture strategic narratives which are more compelling and better at structuring the responses of audiences to the development of events.

‘Shaping public attitudes towards the deployment of military power: NATO, Afghanistan and the use of strategic narratives’ published in European Security. Jens Ringsmose and Berit Kaja Børgesen argue that public support for a given military mission can be shaped by political leaders by means of strategic narratives. Their research suggest that strong strategic narratives increase the likelihood of popular support, while weak story lines are likely to result in a souring public opinion environment.

In Strategic narrative: A new means to understand soft power, Alister Miskimmon, Ben O’Loughlin and Laura Roselle provide an intellectual exercise along the complexities of international politics today, especially in regard to how influence works in the new media environment. They believe that the study of media and war would benefit from more attention being paid to strategic narratives, which they understand as a communicative tool for political actors to construct a shared meaning and to shape the perceptions, beliefs and behaviour of the public.

Image CC0 Public Domain by Defence-Imagery via Pixabay.

The post Strategic narratives and war reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Drones, the Mullah, and legal uncertainty: the law governing State defensive action

The 21 May 2016 drone strike that killed Taliban leader Mullah Mansour riding in a taxi in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province, raises questions about the law governing State defensive action. Fourteen years after the first US counterterrorist drone strike in Yemen, legal consensus remains elusive.

Possible analytical frameworks can be termed the restricted “Law Enforcement” theory, the permissive “Conduct of Hostilities” approach, and the “Self-Defense” option. The “Law Enforcement” theory applies traditional highly restrictive interpretations of State self-defense. While accepting drone use within existing “combat zones”, external action is limited to human rights law based policing and is largely reliant on territorial State consent. Drone strikes are seen as being incompatible with policing. “Terrorist” groups are viewed as small organizations using low levels of force. This perspective applies a 20th Century view of terrorism that avoids the case law threshold justifying State self-defense, or finding an armed conflict exists when applying the Tadić based criteria of group organization and intensity of violence. For Afghanistan a variation of this theory accepts a limited “spillover” into some of Pakistan’s border regions, but this would not include Baluchistan. Exceptionally, drone use in a law enforcement context is viewed as possible, but without permitting collateral casualties. The “Law Enforcement” model seeks to restrict drone use to “hot battlefields” spawning debate about the “geography of war”. Notably it runs afoul of Sun Tzu’s principle of knowing your enemy. Transnational terrorists are part of broader insurgencies organized as hierarchical, horizontal and cellular armed groups, rather than independent components of a “leaderless jihad”. “Law Enforcement” proponents rely on international boundaries to limit violence involving Salafi jihadists. Unfortunately, as recognized by the United Nations, this enemy has more global aspirations.

The “Conduct of Hostilities” approach authorizes action where a State is “unwilling or unable” to police transnational threats emanating from within its borders. The historical “unwilling or unable” principle finds new life in contemporary debate. This theory depends on a post 9/11 recognition of the right to act in self-defense against non-State actors, an importation of neutrality law principles to non-State conflict, and the use of hostilities rules against targets seen as directly participating in an armed conflict. The State self-defense principle of imminence and the humanitarian law concept of direct participation in hostilities (DPH) appear to blend with targets seen as continuously planning attacks. Unfortunately, the potential for overbreadth is enhanced by failing to fully address neutrality law requirements of considering feasible and timely alternatives, and only a strictly necessary use of force; consider the restraining impact State self-defense principles; or transparently articulate the DPH criteria applied. Finally, the “Self-Defense” option, whether described as “naked self” defense or a more robust application of self-defense principles, appears as a form of “gap filling” where law enforcement rules are not applicable to drone strikes, and an armed conflict is seen technically not to exist. Effectively, humanitarian law based rules are applied under the rubric of self-defense.

Problematically, over-reliance on the territorial State under the “Law Enforcement” theory means non-State actors can gain impunity in poorly policed territory forcing the threatened State into a reactive mode enhancing the risk to its own citizens. A security “black hole” has to be avoided. Unfortunately, the more permissive “Conduct of Hostilities” and “Self-defense” approaches appear to exclude policing options and introduce a potentially broader use of force in otherwise “peaceful” territory. It also raises the legal issue of applying of hostilities rules outside of armed conflict.

What is the solution? One approach, the 2013 US Drone policy, applies the “unwilling or unable” test, but limits an armed conflict based approach through a restraining application of human rights principles, and a stricter test of “near certainty” than the “reasonable belief” standard applicable under either human rights, or humanitarian law. As seen in the Syria context States have started to embrace the “unwilling or unable” theory justifying defensive action. However, to gain wider acceptance it cannot be unfettered. It must include a holistic application of all available bodies of law including an overarching application of State self-defense principles; consideration of feasible alternatives (e.g. capture); applying law enforcement where required (e.g. non-DPH civilians), or when feasible; using appropriate DPH criteria, and demonstrating greater sensitivity to the strategic impact of collateral casualties. These criteria could readily be applied to the Mansour strike.

A May 2016 UK Parliamentary Committee report demonstrates consensus on the law may be far off. That report accepted the UK right to act in self-defense against members of the Islamic State in Syria, but raised a number of questions including the basis for applying the “law of war” outside of an armed conflict, and whether such action was governed by the European human rights law. The European Court of Human Rights has previously sought to regulate aerial attacks, however, this raises questions of human rights law overreach, whether a traditionally restrictive authority to use force can effectively counter group threats and attendant threats of violence; and the longer-term normative impact should human rights governing principles be expanded. Human rights law may be more effectively applied in situations of governance, such as in post invasion Iraq, than extended to areas beyond a State’s physical control by means of a Hellfire missile fired at threatening members of an organized armed group.

Meanwhile strikes are occurring, people are dying. Fundamental questions need to be asked about whether the threshold for armed conflict is properly set, how civilians can be effectively protected from “one off” non-State actor attacks, the limits of human rights law, and how best to win a conflict that is ultimately about governance and values.

Featured image credit: ‘Valley of Kohlu’. Photo by Umer Malik. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Drones, the Mullah, and legal uncertainty: the law governing State defensive action appeared first on OUPblog.

July 10, 2016

“All grammars leak”: How modern use and misuse are changing the English language

Anthropologist Edward Sapir once wrote, “Unfortunately, or luckily, no language is tyrannically consistent. All grammars leak.” Sapir was talking about the irregularities of language. For me, this leakiness is especially evident in what I think of as doppelgrammar words.

Many of our most common words have come to serve more than a single grammatical role, so a word serving one part of speech will often have a homonym—a grammatical doppelganger—that serves as a different part of speech. Often this arises from what is called functional shift, when we take a noun and make it into a verb as in to adult or to gym. This shiftiness makes it hard, and perhaps impossible, to think of a word as having just one categorization.

Here’s an example. Recently, a friend told me that her daughter’s teacher had told her to never use the word that. She wondered if the advice was legit.

It depends, I said, which that we are talking about. This humble four-letter word can serve as a pronoun, adjective, conjunction or even an adverb. When we say Hand me that, the word is functioning as a demonstrative pronoun, referring to something oriented away from the speaker (as opposed to this). But if we say, Hand me that book, it is functioning as an adjective, though again indicating orientation. If we say Have you seen the person that was just here, the word is a pronoun again, a relative pronoun linking the noun person to the clause that was just here. Whew.

That can also be a straight up subordinating conjunction introducing a clause functioning as a noun: I told you that I would be right back. This that is the one that writers often cut to make prose move along more quickly: I told you I would be right back is often preferred on grounds of conciseness. This is what my friends’ daughter’s teacher was talking about. And, last but not least, that can even be an intensifying adverb, as in “Yes, it is that complicated.”

Now, we might quibble about these characterizations—perhaps the adjective that and the demonstrative pronoun that are related, Hand me that being a reduced form of Hand me that book. But the larger point is pretty clear: our simplest words serve more than a single function. Grammar leaks, and words have doppelgangers.

Magnetic Fridge Poetry by Steve Johnson. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Magnetic Fridge Poetry by Steve Johnson. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.That is not the only word that does double (or triple or quadruple) duty. The words have, be, and do, for example can be auxiliary verbs (you may know these as “helping” verbs because they help the main verb”) or the main verbs themselves. In I have just arrived, the word have helps the main verb (arrived), but in I have a question, it is the main verb.

Sometimes words are so common and we don’t even think to question their status. Take the word up. It’s a preposition, right? I walked up the block for a cup of coffee. But up can also be an adverb as in He jumped up. Or it can be part of a compound verb We fixed up the house or She wrote up the report. Up can even be used as an adjective or verb: It was an up day for the markets or The university has upped tuition again. The stereotypical characterization of up as a preposition doesn’t do justice to its flexibility.

The flexibility and homonymy of English words is pervasive: words like yesterday, today, and tomorrow can be nouns or adverbs. Compare Tomorrow is another day with I’ll finish the work tomorrow. The word who can be an interrogative pronoun (Who left?) or a relative one (I saw the person who you mentioned). Before and after can be prepositions or subordinating conjunctions: I left after class or I left after I saw them. Well can be an interjection or an adverb, as in Well, I never would have believed that! and The old car runs well. And of course, you and they can be singular or plural pronouns.

So if you expect a word to have a unique meaning or function, you are likely to be disappointed. Words are pressed into service for new functions all the time and the list of such grammatical doubles goes on and on.

Sometimes, though, the status of a word becomes a matter of minor controversy. A librarian I know was called out on social media for using fun as an adjective (a fun event). “As a librarian, you should know better,” her on-line scolder remarked. Well, fun has been an adjective for quite some time. Others get annoyed about the shift of a super from adjective status to intensifying adverb (as in She was super smart).

And a few years ago, the media was abuzz with concerns about the word because being used as a preposition (as in because reasons or because science) rather than sticking to its more traditional role as a subordinating conjunction (because language changes). People who thought the usage was an abomination when they first heard it were using it regularly within a few weeks, at first ironically and then routinely. And Oxford Dictionaries lists these uses of because, super, and fun, tagging them—for now—as informal.

So before we get too judgmental about nouns being used as verbs, or adjectives being used as nouns or as adverbs, let’s take a moment to appreciate the flexibility of the parts of speech. As Edward Sapir put it, the multiplicity of ways in which we express ourselves may be a “welcome luxuriance” or “an unavoidable and traditional predicament.” Which it is may depend on our temperament.

Featured Image: “Bookshelves” by Alexandre Duret-Lutz. CC BY SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post “All grammars leak”: How modern use and misuse are changing the English language appeared first on OUPblog.

Republican’s five stages of grief

Republicans have suffered a death in their family. Sixteen established party candidates have slowly ended or suspended their presidential candidacies in the 2016 presidential election, and party leaders are trying to divine whether Donald Trump’s unthinkable ascent actually spells the end of their party as we have known it since the late 1960s.

Journalists have indulgently chronicled the tortured reactions of Republican diehards, replaying their vows to support the nominee and their earlier assurances that their party would eventually come to its senses. However, as with any death, this one appears irreversible.

Each election cycle for the past two decades, Republicans have carefully embarked on the tightrope walk in which they court the support of the moderate suburban business bourgeoisie with libertarian economic stances, all while wooing largely white working class voters with wedge social issues related to immigration, homosexuality, and religion.

This election cycle marks a (likely terminal) heart attack.

To white working class constituents who are exhausted by career politicians, the Republican Party simply cannot credibly sell itself as Washington outsiders after an obstruction-ridden four years of Congressional control, and holding executive power for the eight years that preceded an economic catastrophe.

To moderates who are turned off by the party’s culture wars, the Republican Party is torn about whether to acknowledge that they are now on the wrong side of wedge issues that previously distracted white working class constituents from their economic plight.

Still feeling the after-effects of the 8-year-old financial crisis and the 40-year collapse of US manufacturing, white working class people have recognized that neither Democrats nor Republicans have done much to ameliorate their economic situation. And cultural conservatives have recognized that Republicans are only paying lip service to social causes that are slowly being invalidated by courts, or are politically untenable.

We are now about halfway through the Five Stages of Grief, as described by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying.

Denial and Isolation

The initial reaction to a loved one’s death is to deny the reality of the circumstances. This was present throughout the Presidential primary season, when Republican candidates, advisors, and donors assured themselves (and the world) that Donald Trump’s popularity was ephemeral.

All the theories emerged after Trump’s second place finish in Iowa: The polls’ respondents were not likely voters. Trump’s supporters were not dedicated enough to endure the caucusing process. Trump lost nearly all last-minute deciders in a race with record turnout.

As Trump won victories in New Hampshire and beyond, new theories emerged: Trump will be bitten by the things he has said and done in the past, and the public will clamor for honesty. Trump will not accrue a majority of delegates and party elites could stage a coup at the convention in Cleveland. This denial lasted longer for some (i.e. Ted Cruz and John Kasich) than others (e.g. Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush). However, denial is a normal way to cope with overwhelming emotions and carry ourselves through the initial pain of loss.

Anger

Eventually, the pain reemerges from behind the illusions of denial. Republicans were not ready for the reality.

This anger has been expressed by a number of GOP luminaries: John McCain, Lindsey Graham, Jeb Bush, Mitt Romney, and Karl Rove.

Anger is directed at Trump, but also at his white working class supporters. They have been called “non-Christian”, “vicious, selfish” voters subject to “incomprehensible malice” who “deserve to die”.

Why haven’t Trump’s supporters come to their senses? Why haven’t they been turned off by Trump’s record? Why don’t they realize that he is not really a Conservative? Deep down, party leaders know that his supporters are not really Conservatives either. Conservatism, as they have come to understand it, is dwindling.

Bargaining

In this position of helplessness, some Republicans have sought a way regain control.

Paul Ryan, the Republican Speaker of the House, has withheld his support for his party’s presumptive nominee to demonstrate to his colleagues that he too is discomforted by Trump’s platform and record. Rather, Ryan is forcing Trump to kiss the ring. Trump shrugged. Cruz has thus far refused to concede his delegates, seeking to use them to fight for a more conservative platform at the convention.

Others have held their nose and endorsed the Trump campaign, many in the hopes that they may subsequently secure a high-level position in a possible Trump Administration, where they may steer the Republican Party back.

Still, others would rather focus on preserving the party by dismissing the current election cycle, and focusing their attention on how the Grand Old Party may make a deal with the American people to postpone their inevitable demise: Next time, we’ll embrace Latinos. Next time, we’ll tweak the election rules again.

Depression

Soon, we will enter the stage of depression. Many Republicans will slog through the remainder of 2016. Others will seek closure by creating some separation from politics. This may entail extended summer holidays or greater involvement in the lives of their families.

Acceptance

Ultimately, the truths that produced Donald Trump’s meteoric rise since June 2015 will remain. In hindsight, there have been many symptoms: The Tea Party rebellion, Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s district loss, John Boehner’s exasperated resignation.

The Republican Party cannot remain everything to everyone. And while all large political parties are effectively coalitions of multiple stakeholder groups, this is only sustainable to the extent that there is coherence between these groups. Democrats’ support for gay rights has not unnerved conservative, religious minorities enough to leave the party. Union voters know that moderate Democrats are better for their interests than any Republican. (Ditto for environmentalists and peace activists.)

On the contrary, Republicans will lose white working class voters (to abstention or revolt) if they continue to be tightly associated with Wall Street. But they will lose Wall Street (to moderate Democrats) if they seek to galvanize the white working class voters fueling Trump’s popularity.

And the difference between Democrats and Republicans is that, thanks to demographic change and urbanization, the Democrats have calculated that they no longer need white working class voters to win.

Comfort for Republicans will only come from acceptance. Change is coming.

Featured Image Credit: Republican Party debate stage by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Republican’s five stages of grief appeared first on OUPblog.

The enduring evolution of logic

Logic is a deep subject, at the core of much work in philosophy, mathematics, and computer science. In very general terms, it is the study of what (conclusions) follows from what (premises)—logical consequence—as in:

Premise: All men are mortal

Premise: Socrates is a man

Conclusion: So Socrates is mortal

The Early Modern philosopher, Immanuel Kant, held that Aristotle invented logic, and at his hands it was complete. There was nothing left to be done. As he says:

“Logic, by the way, has not gained much in content since Aristotle’s times and indeed it cannot, due to its nature… In present times there has been no famous logician, and we do not need any new inventions in logic, because it contains merely the form of thinking.”

— From the introduction to his lectures on logic

He was notoriously wrong.

In the development of Western logic, there have been three very significant phases interspersed with two periods of stasis—and even forgetfulness. (Logic in Eastern philosophy has its own story to tell.) The first was in Ancient Greece, where logic was developed quite differently by Aristotle and the Stoics. The second phase was at the hands of the great Medieval logicians, such as Jean Buridan and William of Ockham. They took up their Ancient heritage, but developed it in many new ways, with theories of suppositio (truth conditions), insolubilia (paradoxes), consequentia (logical consequence), and other things. The rise of Humanism in Europe had a profound effect. Scholasticism was swept away, and with it went all the great Medieval advances in logic. Indeed, it was only in the second half of the 20th Century that we have come to discover the many things that were lost. All that remained in the 18th Century was a somewhat stylized form of Aristotelian logic. That is what Kant knew, and that is why he believed that there had been no advances since Aristotle. Portrait of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The third great period in the development of logic is the contemporary one. The ground for this was laid in the middle of the 19th century by algebraists, such as George Boole. But, driven by questions in the foundations of mathematics, a new canon of logic was invented by Gottlob Frege, taken over by Bertrand Russell, and then polished by some of the greatest mathematicians of the first half of the 20th century, such as David Hilbert and Kurt Gödel. The view that emerged came to be called classical logic—somewhat oddly, since it has nothing to do with Ancient Greece or Rome. Indeed, it is at odds with elements of both Aristotle’s logic and Stoic logic. At any rate, by the middle of the 20th Century it had become completely orthodox. It is now the account of logic that you will be taught if you take a first course in the subject in most places in the world.

However, this very orthodoxy can often produce a blindness akin to Kant’s. The way that logic is taught is usually ahistorical and somewhat dogmatic. This is what logic is; just learn the rules. It is as if Frege had brought down the tablets from Mount Sinai: the result is God-given, fixed, and unquestionable. No sense is provided of the fact that logic has been in a state of development for two and a half thousand years, driven by developments in philosophy, science, and mathematics—and now computer science.

Indeed, many of the most intriguing developments in logic for the last 50 years are in the area of non-classical logic. Non-classical logics are logics that attempt to repair various of the inadequacies perceived in classical logic—by adding expressive resources that it lacks, by developing new techniques of inference, or by accepting that classical logic has got some things just plain wrong. In the process, old certainties are disappearing, and the arguments generated in new debates give the whole area a sense of excitement that is rarely conveyed to a beginning student, or understood by philosophers not party to these debates.

What generated the third phase in the development of logic was its mathematization. Techniques of mathematics were applied to the analysis of logical consequence, to produce theories and results of a depth hithertofore unobtainable. For example, the work of Kurt Gödel and Alan Turing in the first half of the 20th century, established quite remarkable limitations on axiomatic and computational methods. But, for all its mathematical sophistication, the developments in logic were driven by deep philosophical issues, concerning truth, the nature of mathematics, meaning, computation, paradox, and other things. The progress in this third phase shows no sign, as yet, of abating. Where it will lead, no one, of course, knows. But one thing seems certain. Logic provides a theory, or set of theories, about what follows from what, and why. And like any theoretical inquiry, it has evolved, and will continue to do so. It will surely produce theories of greater depth, scope, subtlety, refinement—and maybe even truth.

Featured image credit: ‘Logic Lane’ by Adrian Scottow. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The enduring evolution of logic appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers