Oxford University Press's Blog, page 282

February 3, 2018

Community healing and reconciliation: a tale of two cities

Community healing and reconciliation has been a focus of many nations in response to civil war, genocide, and other conflicts. Over the past 12 years there has been a growing number of high profile murders of African American youth in the United States. Recently the mood of the country has become more acrimonious and the mounting tension has splintered some communities. The rise in murders by police officers have continued unabated and no one has been tried for these crimes, while the continuing climate of senseless shootings of black males gives pause to understanding the reason why.

Some communities have responded to the incidents offering examples of how communities may work together to move forward. Citizens need to feel their presence resonated, their voices heard, and their pain felt in a safe forum if we are to approach healing and reconciliation. That was the charge and commitment of the communities of Sanford, Florida and Cleveland, Ohio. These two cities addressed the strain and strife pronouncing that this was a senseless tragedy for the entire community, not just the grieving family of the Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice. The fork in the road for these two cities was: hatred or healing. They chose healing.

In 2012, the City Manager’s Office of the City of Sanford developed a Nine-point Plan in response to the killing of Trayvon Martin. The City of Sanford sought to transform the community through opportunities to encourage civil dialogue and citizen participation in the planning and transformation of the city.

The Nine Point Plan included the Sanford Police Department working with the Department of Justice in developing a community policing approach. A Police Community Relations Blue Ribbon Panel composed of citizens from all neighborhoods reviewed and recommended best practices for reducing violence in the City. Sanford also developed an anti-violence campaign that recommended initiatives to improve awareness about the effects of violence and its impact on community equilibrium.

The fork in the road for these two cities was: hatred or healing. They chose healing.

The Director of Community Relations established the Office of Community Relations (OCR). OCR addresses past and new disputes to facilitate healing and reconciliation between citizens and the city. An Inter-Racial Inter-Faith Alliance (IRIFA) was established to foster interfaith dialogue. The city expanded its Youth Training and Employment Opportunities by inviting partners to assist the City to help young people with employability skills and opportunities. The reactivation of Sanford Neighborhood Action Partnership (SNAP) aided in improving services to neighborhoods, and empowered neighbors to build their neighborhoods.

Then, in 2014, there was senseless shooting by police of a 12-year-old boy holding an Airsoft replica toy gun in Cleveland. Was he just being a boy or was he threat? Although this debate still resonates, he did not deserve to die. To help heal the wounds of this loss a community efficacy model called CE3 or the Community Engagement, Empowerment & Education framework evolved through a city grant awarded by the federal Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation (BCJI) program. The CE3 model built on the ability of residents to connect with one another, as well as with the police, to establish a network of interconnected programs dictating the willingness of local residents to intervene for the common good, and to hold their local law enforcement accountable based on trust, talking, and transparency. CE3 offered an innovative, trauma-informed approach woven together targeting intergenerational programming and neighborhood pride to help establish positive social norms emphasizing safety, neighborhood advocacy, authentic engagement, and inclusive healing.

Exposure to pervasive community violence greatly impacts the developmental challenges of adolescence, especially black males. Most urban youths will be exposed to some form of trauma related to law enforcement contact and community violence in their lifetimes. This must be addressed. Healing is not a one-time event or experience but rather an ongoing journey where citizens can discuss and envision a future that involves different ways of relating where social justice is a key focus of concern. It’s well understood in the black experience that it takes a village to raise a child. Maybe that local police officer needs to be part of that village. Maybe that officer needs to spend time in the community when not patrolling in order to feel connected to the community, and in return for community residents to see him/her as a normal person. Once this occurs, the potential surfaces for a strong community to build and unite together based on mutual respect and responsibility.

The future requires that social workers, educators, public health practitioners, and police officers join forces to substantially improve the effectiveness of violence prevention programs by acknowledging and addressing the behavioral and emotional consequences of exposure to local neighborhood conditions.

Featured image credit: We are better than this by Jerry Kiesewetter. Public Domain via Unsplash .

The post Community healing and reconciliation: a tale of two cities appeared first on OUPblog.

February 2, 2018

How well do you know Jean-Jacques Rousseau? [quiz]

This January, the OUP Philosophy team honors Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) as their Philosopher of the Month. Rousseau was a Swiss writer and philosopher. He is considered one of the most important figures for his contribution to modern European intellectual history and political philosophy. His books have attracted both admiration and hostility during his lifetime and had an immense influence on his contemporaries and other thinkers.

You may have read his work, but how much do you really know about Jean-Jacques Rousseau? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz background image credit: Jean-Jacques Rousseau by Allan Ramsay. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Featured image credit: Chateau d’Ermenonville 2. Photo By PhotoBobil. CC-by-2.0. via Wikimedia Commons

The post How well do you know Jean-Jacques Rousseau? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

World Cancer Day 2018: Is prevention worth more than cure?

World Cancer Day is on the 4th of February. The purpose is to increase global awareness and get as many people talking about the disease as possible. Essentially, unite people from all around the world in the fight against cancer—and with worldwide incidence set to increase to 21.7 million by 2030, the fight is now. 2018 is the last in the three year ‘We Can. I can.’ campaign and consists of many small goals for both patients and others, all towards the larger objective of reducing cancer’s global burden.

Cary Adams, CEO of Union for International Cancer Control, the organizers of World Cancer Day, says

“Chances are, at some point in our lifetime we will either know someone who has had cancer or is currently fighting it. It affects us all – be it through a colleague, family member, or friend. The good news is that we know more about cancer today than ever before. Thanks to extraordinary breakthroughs in medicine, diagnostics, and scientific knowledge, we know that more than one third of cancer cases are preventable and another third of cancer cases can be cured if detected early and treated properly”.

Of all the goals outlined in the campaign, such as asking for support or creating healthy cities and workplaces, one really stands out. Prevent cancer. Mentioned almost nonchalantly, it’s easy to forget about the importance of actually preventing cancer in the first place. Accountable for 8.8 million deaths per year, cancer is one of the major causes of death worldwide – yet over a third of these could be completely avoided. Cancer Research UK estimates that this equates to over 600,000 cases in the last five years; around 42% in the United Kingdom and United States and 38% in Australia. By adopting simple lifestyle changes a large proportion of cases would simply disappear. Surely if we focus on this then overall global burden would be reduced?

Most people are aware of the relationship between smoking and lung cancer or sun damage and skin cancer but other lifestyle choices, such as poor diet or alcohol consumption, can also increase the risk of developing a tumour. Of course some risk factors, like age and genetics, can’t be avoided but let’s concentrate on those that can.

Researchers investigating claims of a relationship between Body-Mass-Index (BMI) and the risk of developing cancer found convincing evidence that a higher BMI increases risk of some types of cancer; including endometrial, pancreatic, and oesophageal cancer. However, the exact mechanism of how obesity may cause cancer is not wholly understood. Excess body fat may affect hormone levels (eg insulin or estrogen) and growth factors (such as IGF-1), which can lead to increased cell proliferation. By lowering our body weight, not only should it help keep these processes in check, but added advantages include lower blood pressure, lower cholesterol, and even better sleep. Perhaps we should look to lowering obesity rates as prevention, rather than to chemotherapy as treatment when it’s already too late.

Smoke by 4924546. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.

Smoke by 4924546. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.A recent survey claimed that only one in ten British people knew that alcohol could cause cancer. When metabolised in the body alcohol has been found capable of causing seven different types of cancer, namely bowel, breast, and oral cancers. Enzymes known as alcohol dehydrogenases convert ethanol to acetaldehyde – a toxic chemical that is then further processed into other molecules. If accumulated in stem cells, acetaldehyde can cause rearrangement of chromosomes, DNA deletions, or strand breaks. Whilst these modifications to DNA may not always result in cancer – they do increase the risk significantly. Current guidelines for both men and women are to consume no more than 14 units of alcohol per week (approximately six pints of beer) to keep at a low risk level.

Tobacco smoke contains in excess of 250 harmful chemicals amongst thousands, over 25% of which are carcinogenic. The toxic combination of the other chemicals in cigarettes, add fuel to the fire and work jointly with carcinogens to accelerate damage. This happens mostly via free radicals and reactive oxygen species (toxic by-products) contained in tobacco smoke, causing mutations in DNA. The most common outcome is the development of lung cancer, which is true for four out of five cases in the United Kingdom. Apart from lung cancers, at least 13 other types have increased risk as a result of smoking – mostly gastrointestinal-related tumors.

Processed meat is not something that springs to mind when talking about cancer, but was classed as a carcinogen in 2015 by the WHO. This largely relates to the risk of developing post-menopausal breast cancer and should be looked at relatively. Eating two rashers of bacon probably isn’t going to be as harmful as smoking 30 cigarettes a day.

“Greater public understanding of cancer risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol consumption, poor diets, sedentary lifestyles, and excessive exposure to the sun, is one step toward effective cancer prevention. It is with knowledge and information, combined with appropriate public policies, such as tobacco control laws and health and safety in the workplace, that individuals and policy makers are empowered to reduce their individual cancer risk and build a healthier nation and world.” – Dr. Cary Adams, CEO, Union for International Cancer Control

Benjamin Franklin famously said “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”. And he’s right. However, just because you adapt all these lifestyle changes or are doing so already, it doesn’t guarantee you are protected against cancer. It simply means your chances of developing the disease are lowered, in some cases considerably. Regardless, the additional health benefits that could be reaped make this a no-brainer. That’s easy to say. We need to understand why people live like they do. Maybe the affordability of healthy produce is a stretch for some, and maybe the night shift worker can’t get to a gym. Identifying the cause behind these ‘choices’ equips us better to support rather than judge.

Featured image credit: We Can. I Can. CC BY-SA 4.0 via World Cancer Day.

The post World Cancer Day 2018: Is prevention worth more than cure? appeared first on OUPblog.

Composer Alan Bullard in 10 questions

From time to time we ask our composers questions about their musical likes and dislikes, influences, and challenges. We spoke to Alan Bullard about who or what inspires him, his writing habits, and what he likes to do when he’s not composing.

What pattern does a typical day in your life take?

Emails, admin, some composing — usually in my studio in the garden.

What do you like to do when you’re not composing?

I enjoy country walks, going on holiday, and spending time with my family.

How do you prepare when you are beginning work on a new piece?

If it’s a vocal piece, finding an appropriate text can take as long as writing the music: but whether it’s vocal or instrumental, thinking of the mood that I wish to create, and how best to achieve that, is an important preliminary before the notes hit the page.

Do you treat your work as a 9 to 5 job, or do you compose when you’re inspired to do so?

As a 9 to 5 job, though these hours often stretch into the evening. If I’m ever ‘inspired’, it comes in short bursts, so I am often working on more than one thing at a time.

Alan Bullard © Oxford University Press.

Alan Bullard © Oxford University Press.How do you know when a composition is finished, and it’s time to stop editing?

With computer software it’s much easier to continually revise than when you’re working on manuscript paper, so it is difficult to know when to stop. After a certain amount of editing I like to leave a piece for a few days and then come back to it. Then I quite often find that my earlier thoughts were better than my later ones! Having said that, there are always things in published works which one wishes one had done slightly differently.

What or who has influenced you most in your life as a composer?

The realisation that performers and audiences also have a part to play in the creative process, and a growing awareness that it is good to consider one’s music from their point of view.

What made you want to be a composer?

At junior school, aged about 8, I learned the recorder and soon discovered the joys of improvisation. Then, in a music shop, I saw that you could buy books of blank music paper. I asked my parents to buy me one and I soon filled it up. My parents were not musicians, but they were artists, and seeing them create in their way – in paintings or textiles – made me naturally gravitate towards musical creativity.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

Although my music was never complex, I think and hope that I have gradually learnt to pare down my ideas and approach each task with greater simplicity and clarity, whether writing for professionals or amateurs.

What was the last concert you attended?

A piano recital of Grieg’s music at Troldhaugen, Grieg’s country house near Bergen, Norway.

What do you listen to as a ‘guilty pleasure’?

Stanford’s ‘Songs of the Sea’ for its sheer exuberance and unfashionable non-PC text – closely followed by his ‘The Revenge’ for the same reasons!

Featured image credit: Sheet music recorder by 2204574. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Composer Alan Bullard in 10 questions appeared first on OUPblog.

February 1, 2018

The joys and challenges of compiling a new organ anthology

Faced with a blank sheet of paper, how does one begin when an invitation is received to compile an anthology of music? Compiling the two recent volumes, Oxford Book of Christmas Organ Music for Manuals and Oxford Book of Lent and Easter Organ Music for Manuals, has been a rewarding journey of musical discovery, which I decided had to begin at Perry Barr in north east Birmingham, on the campus of the University of Central England, at the library of the Royal College of Organists. My days there amongst the moveable stacks proved invaluable, hopping up and down steps and sifting through the boxes of this unique and sizeable resource. I became completely absorbed as my eyes were opened to some previously unknown repertoire that would be suitable for inclusion, enabling me to disregard the temperature of an air-conditioned archive store, pleasantly cool in summer but freezing in winter.

I went through the entire collection three times, not only searching for suitable music for organists looking to extend their seasonal repertoire, but also set on finding attractive pieces that would lie within the grasp of pianists who have been coerced into the role of organist. Some original compositions were straightforward candidates for inclusion, but most music required arrangement—in some cases adapting a composition for manuals and pedals so that it could be playable by hands alone. Maintaining the artistic integrity of the composer was a fundamental principle here, which was also applied when making transcriptions from seasonal oratorios.

Robert Gower. Photo used with permission.

Robert Gower. Photo used with permission.For the Christmas book, J. S. Bach, the organ, and December are inseparable (come back BBC Radio 3’s 2005 “Bach Christmas”!) and it seemed entirely right to open the anthology with the aria “Prepare thyself, Zion” from Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. His lesser-known Prelude (originally for trumpet and organ) on the Advent chorale “Wachet auf” provides an attractive alternative to its more famous relative. Pieces from Berlioz and Liszt were similar must-haves, with some strong writing from the less familiar names of Balbastre, Greiss, Hänlein, Kneller, and Wolfrum. Those like myself who take pleasure from English music, can enjoy music based on familiar Christmas hymns by two 20th-century cathedral musicians, Clement Charlton Palmer (Canterbury) and Ambrose Porter (Lichfield).

Commissioning new work is an exciting privilege: how good it is to introduce an arrangement of “Jingle Bells” by the international jazz pianist Alexander Hawkins (who also holds a PhD in Law); a vibrant, dancing Toccata on “Good King Wenceslas” by Matthew Owens of Wells Cathedral; a reflective atmospheric reflection on “Forest Green” (O little town of Bethlehem) by rising star Owain Park; together with Malcolm Riley’s characteristically witty, ingenious, and playful “I saw three ships in Sussex”, its humour matched by the tinsel glitter of Germain Rivière’s “Ding dong! Merrily on high” variations. Working through the RCO’s catalogue from A to Z, I was amazed that one significant personal discovery should appear in the very last box with the music of Dutch organist-composer Jan Zwart. Persistence pays!

Bach’s Chorale Prelude on “Erbarm dich mein, o Herre Gott” from Oxford Book of Lent and Easter Organ Music for Manuals.

Bach’s Chorale Prelude on “Erbarm dich mein, o Herre Gott” from Oxford Book of Lent and Easter Organ Music for Manuals.Bach opens the Lent section of the second book, but pieces on Lutheran chorales are balanced by music based on well-known tunes to hymns such as “Forty days and forty nights”, and “Be Thou my guardian and my guide”. An ebullient Palm Sunday flourish by Chris Tambling (whose sadly premature death in 2015 was such a loss for church music) and a moving reflection on S. S. Wesley’s “Hereford” by centenarian and doyen of the organ world Francis Jackson appear in print for the first time, whilst appetites will surely be whetted on playing, for example, the music of Robert Groves, Adolphe Marty, Alec Rowley, and Paul Vidal.

Featured image credit: church organ by nickelbabe. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The joys and challenges of compiling a new organ anthology appeared first on OUPblog.

January 31, 2018

Truth, lies, and the Reformation

We are obsessed with lying, a subject which has been much in the news recently. A main concern has been the production of ‘fake news’, news that is a lie. The issue is of fundamental importance: if we don’t have proper evidence and accurate testimony then we can never get to the truth. Of course, sometimes that is not possible however hard we try, but that does not mean we can abandon conceptions of truth. Without a belief in truth there can be no conception of lying and all behaviour becomes morally relative. This is why there is a widespread belief that lying is such an awful crime, that to be exposed and labelled a liar singles out the perpetrator as scarcely human. It is little wonder that there are so many lists of famous liars easily available on the internet debating whether Richard Nixon is worse than Lance Armstrong, Bill Clinton more pernicious than Jeffrey Archer, or Zeus more culpable than Odysseus. Lying generates easily justifiable anger as it violates a fundamental human contract which demands that we tell the truth when asked.

Lying has a history; it is just not one that can be easily recognised or narrated.

Debates about lying are venerable, and in many ways they never change. There are two extreme positions. On the one hand there is the argument that one should never lie, most famously articulated by Immanuel Kant, who argued that one had a duty to tell the truth even to the murderer at the door. Then there is the opposite position which argues that we need to face up to the fact that people lie all the time, and, perhaps, even the ability to tell lies is a sign of civilised sophistication.

Most of us live in between these positions and simply tilt one way or the other, depending on circumstances. Fleeing his pagan persecutors down the Nile in a boat, the wily Church Father, Saint Athanasius of Alexandria, was asked if he knew where Athanasius was. “I believe he is in the area,” he told his pursuers, who set off to find him as he made good his escape. Persecuted Jesuits in Elizabethan England were instructed in these cunning arts, enabling them to avoid lying while not actually telling the truths that the authorities wanted to hear. If asked if they were a priest, they could vehemently deny it, silently adding “Of Zeus”, which God, but not the men eager to execute them, would hear and understand (mental reservation). If a sympathetic householder harbouring a priest was asked if one “lay (lived) in his house” he could exploit the pun and deny it in good faith, because the priest was standing up (equivocation). For the Protestant authorities these were simply lies; for Catholics, smart thinking endorsed by God to preserve the true faith.

Lying generates easily justifiable anger as it violates a fundamental human contract which demands that we tell the truth when asked.

Crises of authority, when no one is sure who is really in charge and who guarantees truth and reality, place pressure on issues of truth and give rise to anxious debates about whether it is permissible to lie, as well as numerous instances of lying. Probably the greatest and most widespread crisis was the advent of the Reformation five hundred years ago when Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the Church door in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517, an event which still haunts the world today. With the authority of the church attacked and Protestants arguing that men and women had to communicate directly with God, it is easy to see why issues of truth and lying assumed an even greater importance than they normally did. Catholics taunted their rivals that they had the church to guide them whereas Protestants were on their own. They might tell lies which resulted in eternal damnation.

More and Rich

In England, Henry VIII assumed control of the English church after he inaugurated the split with Rome in 1532. One of the first to be tried for denying Henry’s supremacy was Thomas More, executed on 6 July 1535. At his trial More famously accused the main prosecution witness, Richard Rich, of being a liar. Perhaps this is fair, but both More and Rich agreed that he had spoken exactly the same words, denying that the king had the right to declare himself head of the church. More and Rich both agreed that they had had a conversation while More’s books were being removed when he was imprisoned in the Tower for refusing to swear the Oath of Supremacy declaring that Henry VIII was the Head of the English Church. More asked Rich if he would accept parliament’s judgement if the assembled body declared that God was not God. When Rich declared that parliament had no such power, More countered that neither political body had the right to make the king the head of the church. For More this was the sort of hypothesis that any decent common law lawyer would discuss; for the crown, in the febrile and terrifying days after the Reformation, this was treason, words uttered with malice designed to damage the crown. More protested his innocence but was found guilty. Rich was, he asserted, a liar, because he had misrepresented his innocent, truthful words. More was, according to the crown prosecution relying on Rich’s testimony, lying about his motives and meaning. We have the same words, but different ideas about meaning, context, and what constituted a lie.

Future lies

It is hard to see that we will sort out the problem of truth and lying in the near future. Mary McCarthy’s famous accusation that everything that Lillian Hellman said was a lie including ‘and’ and ‘the’ is a recognition that lying is an endemic problem as well as a vicious attack on someone she despised. Narrating the history of lying will never provide satisfying, certain answers. Instead, we should explore particular historical moments and discover what happens to truth and lies in times of crisis.

Featured image credit: Renaissance schallaburgfigures by bogitw. Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post Truth, lies, and the Reformation appeared first on OUPblog.

Etymology gleanings for January 2018: Part 1

My most recent post (mad as a hatter) aroused a good deal of criticism. The reason is clear: I did not mention the hypothesis favored in the OED (mercury poisoning). Of course, when I quoted the medical explanation of long ago, I should have written the last set of hypotheses… instead of the last hypothesis. I find all medical explanations of the idiom untenable, and I should have been explicit on this point, rather than hiding behind polite silence.

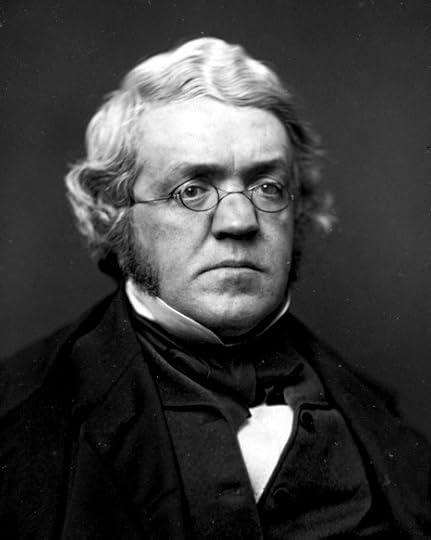

The phrase (as) mad as a hatter turned up in print some time in the late twenties of the nineteenth century. One of the earliest authors to use it, as stated in the OED, was William M. Thackeray. He probably wanted to arouse a laugh by using a piece of the most recent street slang, as was his wont. Charles Mackay, whose pronouncement I ignored in the previous post, wrote, after confessing that he did not know the origin of the idiom: “There is no reason to accuse hatters of madness in a greater degree than any other artificer or trader” (1877). This means that almost half a century after Thackeray, the connection between mercury poisoning and hatters was not common knowledge, to say the least.

William M. Thackeray, a lover of the most recent slang. Image credit: William Makepeace Thackeray by Jesse Harrison Whitehurst. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William M. Thackeray, a lover of the most recent slang. Image credit: William Makepeace Thackeray by Jesse Harrison Whitehurst. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.My database, which I mined for the essay, contains notes and articles published in the periodical press between 1869 and 1913. They came from England, Australia, and the United States. No one suggested mercury poisoning as the source of the idiom’s use. Characteristically, by the time the OED had reached hatter, James Murray had not formed an idea, however tentative, about the etymology of the phrase and promised an answer at mad. But no light came in the intervening years, and the first edition of the OED skipped the etymology of as mad as a hatter. For general orientation: Murray was born in 1837.

Even though hatters’ exposure to mercury and its deleterious effects were noticed rather long ago, the term mad hatter disease (erethism) is relatively recent. I could find no information about who coined it. Nor do I know why some websites are so positive about the origin of the phrase. Do they copy their verdict from the OED online? To use James Murray’s favorite dictum, the hypothesis now accepted by nearly everybody is, at least in my opinion, at odds with chronology.

I have another argument against the medical etymology. For centuries, even for millennia, until the most recent past, when people had become a bit more civilized in their everyday behavior, madmen were feared and mocked in public. It is not for nothing that we have the word giddy. The root of this adjective is the same as in the noun god: derangement was looked upon as a punishment by the gods. Anyone interested in learning more about this connection should look up the etymology of the word enthusiasm. It is hard to judge, because the initial context is lost, but, most likely, the phrase mad as a hatter has always been humorous, something like gaga, he is not all there, kooky, to go bananas, bats in the belfry, and a host of others. The as…as phrases contain an array of the most incredible characters, many of them probably fanciful.

Mercury poisoning is a terrible thing. I happen to know a good deal about the subject, even without consulting Wikipedia (but many thanks for the recommendation to consult it: I am always grateful for bibliographical suggestions), because in my childhood and even much later only mercury-in-glass thermometers existed, and we were constantly admonished not to drop and break the instrument we held under the arm. According to a persistent rumor, Stalin had one of his closest associates (Valerian Kuybyshev) poisoned by the mercury rubbed under the rug in his office. It is inconceivable to me how such a terrible thing as an occupational disease, if its causes were known to the public, could have become the source of a joke.

Alice in Wonderland was published in November 1865. I assume that Lewis Carroll had no idea of the origin of the idiom. The attempts to find the prototype of his character point in the same direction. I assume that, in the words of Mackay, there was no need to accuse hatters of madness in a greater degree than any other trader or artificer. Nor would Lewis Carrol have treated such a grim subject facetiously: to him the phrase probably meant not more than mad as a March hare (incidentally, the origin of this bizarre simile has also been the object of much learned speculation) or as pleased as Punch.

Alice and the famous mad hatter: no visible signs of mad hatter disease. Image credit: “Vintage Book Illustration Alice In Wonderland” by Prawny. CC0 via Pixabay.

Alice and the famous mad hatter: no visible signs of mad hatter disease. Image credit: “Vintage Book Illustration Alice In Wonderland” by Prawny. CC0 via Pixabay.So, in the spirit of the subject at hand, I’ll stick to my folly, reject the reference to medicine, and repeat what I said a week ago, namely, that we should perhaps look for an explanation in some incident (now hopelessly forgotten: the etymological cat is gone, but the smile is still with us), a music hall joke, or some change in the wording. It is not altogether improbable that the longer version as mad drunk as a hatter once existed and, after drunk was dropped, turned into a meaningless but colorful simile. One of the correspondents to Notes and Queries wondered: “Does a mad hatter make madcaps?” I would be more inclined to derive mad as a hatter from mad drunk or madcap than from mercury poisoning.

To reinforce my conclusion, I would like to mention another idiom, connected with derangement. Today, this idiom is probably known to few. To sham Abraham means “to feign madness or sickness.” Abraham seems to have been the name of the ward in which deranged patients were confined in the hospital of Saint Mary of Bethlehem in London or any similar institution. How the ward’s name originated is not quite clear. It is said that on certain occasions, some inmates were allowed to leave the hospital, and many of them went a-begging in the streets. Naturally, they were harassed by crowds of jeering boys and shunned by respectable people. The patients of that ward received the name of Abraham men.

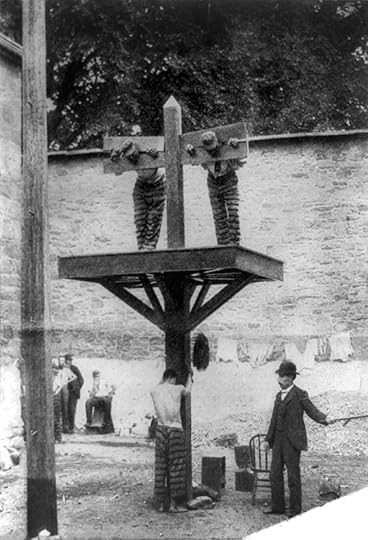

As time went on, the plight of those who occasionally roamed the streets of London began to arouse pity rather than ridicule and horror, and they were given money or otherwise taken care of. Feigning madness became a lucrative occupation for ingenious scoundrels. They would put on the Bethlem dress that indicated their status and impersonate madmen. This trick became an offense punishable by the whipping-post and confinement in the stocks. In Act II, Scene 3 of King Lear, Edgar, now disguised as Poor Tom, explains: “The country gives me proof and precedent/ Of Bedlam beggars, who with roaring voices,/ Strike in their numb’d and mortified bare arms/ Pins, wooden pricks, nails, sprigs of rosemary;/ And with this horrible object, from low farms,/ Poor pelting villages, sheep-cotes, and mills/ Sometimes with lunatic bans, sometimes with prayers,/ Enforce their charity.” Later, to sham Abraham “to malign” became part of sailors’ slang. Note the absence of the light-heartedness that characterizes the idiom as mad as a hatter.

This is what medieval stocks looked like. And another barbarous tool of punishment: a whipping post. Image credit: Digital ID cph.3b44982 via United States Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is what medieval stocks looked like. And another barbarous tool of punishment: a whipping post. Image credit: Digital ID cph.3b44982 via United States Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In sum: I have no doubt that hatters suffered from mercury poisoning, but I don’t believe that this fact has anything to do with the emergence of our phrase in the 1820s. From the critics of this conclusion I would like to hear where I have gone wrong in my reasoning.

Featured image: Royal…. before it moved….. Image credit: Most of Bethlehem Hospital by William Henry Toms. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for January 2018: Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Legal rights are not all right: when morality and the law collide

In early November 2017, media outlets hailed the Paradise Papers as a major scoop: 13.4 million leaked documents revealed the financial details of some of the world’s leading brands, politicians, sports stars, and musicians. But this was to be no repeat of last year’s Panama Papers, in which well-known names appeared relating to criminal acts like “corruption,” “tax evasion,” and “money laundering”; the Paradise Papers failed to reveal a single crime.

So why was it considered news?

The general public’s views of “right” and “wrong” are on this and many other occasions at odds with lawful definitions of “legal” and “illegal.” While the latter express a state’s interests in sanctioning certain exchanges or behaviours (i.e., are an expression of power and an attempt to manufacture a specific type of social order), the former are social beliefs about the legitimacy of certain acts, which may or may not coincide with the legal definitions. Bono buying a stake in a Lithuanian shopping mall, or Lewis Hamilton importing his private jet to the Isle of Man might be perfectly legal, but the general public does not accept it as moral or legitimate. These are extraordinarily wealthy people who, with the help of tax advisors, avoid their public duty of contributing the same rate as lower earners to the common pot. When a private estate acting for the Queen invests in offshore private equity funds, operating in infamous tax havens like the Cayman Islands and Bermuda, it appears that she is maximizing financial gains by using a service closed to, and at the expense of, the majority of her own subjects.

Such discrepancies between the practices of the wealthy and the moral repulsion felt by ordinary citizens are common. The practice appears to be illegitimate, but it is legal. The opposite phenomenon can also be observed. A practice may be considered morally legitimate, but is in fact outlawed. Cannabis use is illegal in most countries, where significant parts of society see it as completely legitimate. Since legitimacy refers to moral beliefs that are not necessarily shared uniformly in a society, social attitudes towards illegal products and services often vary considerably between social groups and at different points in time. Take the history of cocaine, which went from medical breakthrough to scourge of society within a hundred years. Discovered in Germany at the end of the 19th century and used legally as an anaesthetic for several decades, it was prohibited in the mid-20th century as a result of religious and moral concerns, especially in the US. Currently, UK law lists cocaine as a class A drug in which possession can result in seven years in prison, and its supply and production is punishable by life behind bars.

La Salada Market. Party of Lomas de Zamora. Great Buenos Aires Argentina. by Claudio Vallori. CC-BY-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

La Salada Market. Party of Lomas de Zamora. Great Buenos Aires Argentina. by Claudio Vallori. CC-BY-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Changes in the law in line with changes in public morality work in both directions. Where cocaine went from legal and accepted to illegal and unacceptable, homosexuality, for instance, followed the opposite trajectory. Punishable by the death penalty until the 19th century, homosexual behaviour has been gradually decriminalised in the UK to reflect prevailing social attitudes, culminating in the legalisation of gay marriage in 2014. But simply legalising something—be it a product, service, or behaviour—due to a change in social attitudes is far from simple.

To give an example of the complexities involved, consider the case of La Salada in Argentina, Latin America’s largest market for counterfeit clothing. Argentine society has rather ambivalent attitudes towards the market, but on the whole tolerates it because it provides clothing for mid- to low-income families that could otherwise not afford such goods. Politicians tolerate it on the one hand for the same reason, and on the other hand because tolerating it generates political support and employment. So why not legalise it? Legalising La Salada would involve lifting regulations on safe working practices (clothing is produced in sweatshops that break numerous labour laws), lifting trademark laws (clothing is illegally branded with logos such as Nike, Adidas, and Disney), and enforcing business taxes. The effects of this would raise the prices of clothing, thereby nullifying the positive effects of the market, and the very reason for it being socially acceptable. Besides that, lifting trademark laws is simply impossible.

In the case of the Paradise Papers and offshore tax havens, following public morality would mean making such arrangements illegal, as in the case of cocaine. However, like in the case of La Salada, changing the law around tax havens presents an enormous challenge that no state can hope to undertake alone. Offshore financial activity is a result of other states offering tax breaks to lure business into their jurisdictions—without an agreement on tax regimes involving many countries, preventing this is impossible. Where tax breaks continue to be available, we can expect anyone who can to take advantage of their legal right to do so. Meanwhile, the court of public opinion will continue to make up its own mind about what’s “right” and what’s “wrong.”

Featured image credit: good bad opposite choice by Ramdlon. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Legal rights are not all right: when morality and the law collide appeared first on OUPblog.

January 30, 2018

Dr. William H. Harris reflects on his career advancing orthopedic surgery

To mark the release of Vanishing Bone, in Part One of our Q&A with Dr. William H. Harris we discussed the fascinating story of how he came to identify, and later cure, the severe bone destruction affecting individuals who had undergone total hip replacement surgery.

In this second interview, Dr. Harris reflects on his remarkable career; including what inspired him to pursue orthopaedic surgery, how he balances his two roles as a surgeon and clinician-scientist, and his advice for aspiring surgeons.

What inspired you to become a physician and later, what led you to specialize in orthopaedic surgery?

I was inspired to become a physician primarily through unbounded admiration for my father. Initially he had been a general practitioner and then during the depression he undertook additional training in radiology. Although he adored being a radiologist and, indeed, was an excellent radiologist, he never lost the original instincts of being a general practitioner. A striking example of this was his common practice of leaving the radiology department to go anywhere throughout the hospital to do his own examination of the patient under circumstances when he felt that his ability to accurately interpret the x-rays without seeing the patient was compromised. This was, at that time and remains now, a most uncommon attribute. He loved being a physician and that showed through in every feature of his life. It also inspired me.

Dr. William H Harris. Photo used with permission.

Dr. William H Harris. Photo used with permission.My original interest in the field of orthopaedic surgery grew from an unusual experience. My dad had told intriguing stories of his time during World War I in France when he had at his command a motorcycle. My brother and I begged for a motorcycle during our teenage years, requests which were always rebuffed with an explanation of the high risks involved. To prove his point, dad took me to the hospital on a Sunday afternoon and into the operating room to observe a patient badly damaged by a motorcycle accident. Among other things, the injury to his hand had stripped the skin off a large segment of his wrist, hand and fingers. When I saw the complex and intricate anatomy of the hand and could envision the interplay between that anatomy and the function of the hand, I was hooked. The devotion to details of human anatomy and its broad interrelationships to human function at all levels has sustained my career over all these decades.

You created the ‘Harris Hip Score’, and you performed the very first total hip replacement in a patient with a total congenital dislocation of the hip – among many other achievements. What do you consider to be the most defining moments of your surgical career?

The development of the Harris Hip Score, which is used worldwide in evaluating hip function both preoperatively and postoperatively, grew out of the compelling need, if true progress was to be made, for a rigorous method to quantify the effects of hip disease and of hip surgery. There was substantial dissatisfaction with previous efforts along this line, and so I introduced the concept of the Harris Hip Score early in my career (1969), the same year I founded the Harris Orthopaedic Laboratory.

Another defining moment was the initiation of and the pursuit of (over six decades) the prevention of fatal pulmonary emboli following hip surgery. At the beginning of total hip replacement surgery 2 percent of all patients died of a fatal pulmonary embolus. That really is one patient out of every 50 operations. This is a terrible price to pay for the surgical solution of a non-malignant disease, arthritis of the hip. Following my initial efforts, through the massive efforts of our research and the work of many investigators, this risk has been virtually eliminated. The current risk is very close to zero, three patients out of 1000.

Yet another rewarding area of contribution was that of my work on implant designs which is for total hip replacements. Among many of these advances, particularly satisfying is the design of the cement-less hip socket which Jorge Galante and I designed, now the worldwide standard, adopted by every manufacturer.

But perhaps the most surprising answer to your question would be this: the training and inspirations transferred to a most remarkable group of 100 highly talented young hip surgeons, the Harris Hip Fellows. Their contributions and their successes are my most enduring legacy.

Follow your dream. Select a career that simultaneously stimulates and challenges you. Be excited by what you are doing and do exciting things.

In addition to being an orthopaedic surgeon, you are also a researcher and have authored over 500 scientific articles, and several books. How do you balance the very different characteristics needed to excel in a patient care setting, versus those needed in a research environment?

The rewards, both intellectual and emotional, of being a clinician scientist can be very rich, especially so are the potential rewards to a surgeon-scientist. The surgeon-scientist is both emotionally and intellectually driven by his or her failures, but is also provided the opportunity of taking the limitations and failures that he sees his own patients into a laboratory setting to see if creative efforts can solve those problems. But the key requirements for success in each endeavor, namely surgery versus innovation, are vastly different. In the first instance the surgeon must instil in the patient a deep sense of trust, and important interpersonal attribute. Then he or she must combine technical skills with a crisp capacity at decision-making and extensive equanimity under intense pressure. The results of the surgeons’ labor are generally fully recognized at relatively short durations after the operations. Society demands of the surgeon that only those operations with a high probability of success should be undertaken.

Contrast that with the requirements for successful innovation. If the investigator only does those things which have been shown to work in the past, the entire adventure is a failure. The innovator, by definition, is only successful if things which have never been done before can be brought to fruition. In contrast with the surgeon, the innovator has the freedom to run 100 different trials to see which path has the greatest success. The interplay of these two remarkably different, and challenging, forms of human endeavor makes the role of the surgeon-scientist uniquely intriguing.

Finally, what advice would you give to any new surgeon trainees?

Follow your dream. Select a career that simultaneously stimulates and challenges you. Be excited by what you are doing and do exciting things.

A fundamental necessity is to seek and obtain the best possible surgical training in a very rigorous program dedicated to the highest possible standards. It is also key to foster and sustain an abiding interest in continuously improving both the craft of surgery itself and your skills in that craft. Finally, it is essential to retain a deep commitment to every human being in your care. Within those parameters, follow your dream. Select a career that simultaneously stimulates and challenges you. Be excited by what you are doing and do exciting things.

Featured image credit: “xray” by rawpixel.com. Public domain via

Unsplash.

The post Dr. William H. Harris reflects on his career advancing orthopedic surgery appeared first on OUPblog.

Knowledge of the Holocaust: the meaning of ‘extermination’

Did ordinary Dutchmen know of the Holocaust during the war? That might seem an easy question to answer. Research has shown that the illegal press, Dutch radio broadcasts from London, and even exiled Queen Juliana characterized the deportation of the Jews almost from the beginning in the summer of 1942 as mass murder, destruction and, in the Queen’s words, “systematic extermination.” Allied warnings and even German propaganda also spoke of destruction and annihilation. So did Dutch diarists. Analysis of 164 wartime diaries finds 67 that used such terms to describe the Jews’ fate. That seems to answer our question and confirm what has been the conventional wisdom since Walter Laqueurs path breaking The Terrible Secret (1979): the Holocaust in fact never was a secret at all.

Or was it? Let us look at one telling, and typical, example of such a diarist: Etty Hillesum, a young Jewish aspiring writer and student of Russian, whose diaries and letters written in 1941-1943 have gained some renown, and have been translated in many languages. When she heard about the upcoming deportations in early July 1942, she wrote, “What is at stake is our impending destruction and annihilation, we can have no more illusions about that. They are out to destroy us completely.” On 11 July she cynically reported “lovely stories” of Jews being killed by poison gas.

However, on the very same day, she wrote:

I catch myself making all sorts of minor but telling adjustments in anticipation of life in a labor camp. Last night when I was walking along the quay beside him [her lover] in a pair of comfortable sandals, I suddenly thought, ‘I shall take these sandals along as well, I can wear them instead of the heavier shoes from time to time.’

Which, she added a little later, was necessary, because:

My biggest worry is what to do with my useless feet. And I just hope my bladder heals up in time, or else I’m bound to be a nuisance when we are all herded together. And I must go to the dentist soon – so many essentials that I have put off endlessly but are now, I think, urgent.

Urgent because “that would really be awful: suffering from toothache out there,” she wrote a few days later. She decided to get a good-quality backpack and pondered what to take along—her Russian dictionary for sure, so she could keep up her language skills. Perhaps, she mused, those language skills would render her a ”special case”, and might even land her in Russia, “although God alone knows by what circuitous route.” To deal with her “most difficult moments” she was determined to keep in mind “that Dostoevsky spent four years in a Siberian jail with the Bible as his only reading matter. He was never allowed to be alone, and the sanitary arrangements were not particularly marvelous.”

What to make of this? Etty believed herself to be under “no more illusions” about the “impending destruction and annihilation” of the Jews. But she clearly had no idea what awaited in Auschwitz and Sobibor. “The East” to her meant a new and difficult life in a camp where one could probably not get a toothache or bladder treated, but where one could store an extra set of shoes and some books, and where there might be employment for a teacher of Russian. It might in fact resemble Dostoevsky’s banishment.

So how, then, do we explain her use of terms like “extermination” and “destruction”? Was she of two minds? Did she recognize the truth one moment, and repress it the next? I think the answer is less complicated: to her, “extermination” and “destruction” did not mean what it means to us, namely immediate murder. Extermination to her meant forced emigration to some uninhabitable place, where in the long run many would die.

And she was not alone. Two-thirds of the diarists who used such terms to describe that fate of the Jews also suggest they would be put in camps and put to work. None clearly state that the deportees would be killed upon arrival. When they envisioned the “annihilation” or “destruction” of the Jews, they imagined a deadly combination of expulsion and forced labor. Which should not surprise us, as that is how, up to the summer of 1941, the perpetrators themselves imagined the future extermination of the Jews would come about.

Thus the widespread use of terms like “extermination” and “destruction” is less revealing than it seems, and does not justify the conclusion that ordinary people in occupied Europe knew of the Holocaust.

Featured image credit: Architecture bridge building dawn by Pexels. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Knowledge of the Holocaust: the meaning of ‘extermination’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers