Oxford University Press's Blog, page 278

February 17, 2018

Has “feminism” beaten “complicity” or are feminists complicit too?

According to Merriam-Webster Dictionaries,“Feminism” is Word of the Year 2017,” as announced by a headline in The Guardian. “Complicit” was a strong runner-up in Merriam-Webster’s Competition though, and came in first place on the Dictionary.com list. Both “feminism” and “complicit” have been around for some time, so it is not as if 2017 gave birth to either word. Feminism came on top both because of a number of significant spikes in searches as well as a general increase in usage. According to Dictionary.com “complicit” won because it “serves as a symbol of the year’s most meaningful events and lookup trends”. The somewhat bizarre, though amusing notion of a competition between words, and the slightly opaque criteria that determined the winner should not detract from the value of reflecting on “feminism” and “complicit” together.

Those who hankered for some good news to end what had been a pretty bad 2017, might read Merriam-Webster’s announcement as a political victory. Pussy hats beat faux-feminism. Ivanka Trump lost to Scarlett Johansson. The gloomy reality of political entanglements was pushed to second place by the tiny glimmer of hope we felt when marching the streets together in Women’s Marches all over the globe. In fact, both “feminism” and “complicit” reference some of the political resistance that confronted the rampant racism, misogyny, and dispossession. Feminism’s gained new significance and resonated with people who might previously not have identified with the movement, in the face of the explicit condoning of violence against women. Scarlett Johansson’s spoof promotion of “Complicit” perfume was not just a funny sketch but a political statement.

However, let’s not forget that it wasn’t just a good year for feminism. Not only because of the exposure of widespread violence against women and the loudness of anti-feminist voices. (Merriam-Webster does not tell us how many trolls and anti-feminist websites appear when people type “feminism” in their search engines). It was also not a good year because Ivanka Trump called herself a feminist, following a long tradition of the co-optation of feminism. It isn’t that long ago, for instance, that Laura Bush helped justifying a war in Afghanistan by claiming to save Third World women.

Women’s March 2017 by Bonzo McGrue. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Women’s March 2017 by Bonzo McGrue. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.But Ivana Trump is not the only one who should be questioned about complicity. Various feminists have also shown themselves to be complicit with the anti-Muslim racism fuelled by Europe’s migration crisis. Some “feminists” reinforced the oppression and exclusion of trans people. 2017 further reinforced what had already become obvious in 2016, namely that some white women are happier to stand by racist and misogynist men rather than fight against them with their sisters of colour.

Beyond those blatant examples, the narrow competition between “complicit” and “feminism” should invite us to think about the two together and critically interrogate our own feminist practices. Too often liberation is premised on the marginalisation of other women. And our silence on issues that don’t seem to concern the privileged among us, such as the dispossession of large populations in the global North and South for increased wealth for the few, and the fortification of the borders of rich nation-states, is harmful to those who are directly affected. In a complex world in which our lives are intertwined on a global scale, there is no pure position where to stand or from which to speak. Instead of feeling resigned, this should encourage us to formulate some ambitious New Year resolutions.

Let’s make “solidarity” and “feminism” the winning words of 2018.

Featured image credit: DC Women’s March by Liz Lemon. Public domain via Flickr .

The post Has “feminism” beaten “complicity” or are feminists complicit too? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know George Berkeley? [quiz]

This February, the OUP Philosophy team honours George Berkeley (1685-1753) as their Philosopher of the Month. Berkeley was born in Ireland but travelled Europe, lived in America, and eventually settled in London. He is best known for his work in metaphysics on idealism and immaterialism. Berkeley also worked on a range of other philosophical areas, including ethics, natural law, and physics.

How much do you know about the life and work of George Berkeley? Test your knowledge with our quiz below.

Quiz image: Bishop George Berkeley by John Smybert. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

Featured image: Kilkenny castle by Christian B. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post How well do you know George Berkeley? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

February 16, 2018

The neurology of the Winter Olympics

The human brain is a wonder and a marvel. At the same time, it is enigma and frustration. Given all it has accomplished, it continues to perplex. This is why I became a neurologist. For me, combining the apex of all organic structures with the vast unknown of cerebral neuroscience produces a daily wonder that is worth dedicating a life’s work to. To that end, I find myself somewhere over the North Pole hurling towards PyongChang, South Korea.

Four years ago, roughly, I was on a similar flight to Sochi, Russia for my first experience as a physician for the US Olympic Team. Then, despite all of the preparation, work, dedication, and sacrifice it took to be on that flight, I felt a degree of uneasy apprehension.

“The Olympics!” people would say when they found out why I’d be away from work and family for three weeks, “So amazing…what an honor!”

So, mid-flight jitters were created, mainly on the backs of others’ vicarious attestations. In the end, when faced with that same dichotomy of known vs. unknown and the responsibility of caring for the brain of another human, I fell back on what I first learned as a medical student and intern at Charity Hospital in New Orleans. Stay within yourself. Adjust to the unknown. First, do no harm. You may not have every answer in front of you or on the internet (which didn’t exist when I was at Tulane)… so solve the problem best you can! These are valuable lessons for all physicians, to be sure, but even more so for neurologists.

These lessons served me well in Sochi, as a foundation wrapped in the premise that it doesn’t matter to the person you’re caring for whether they were hurt in an Olympic halfpipe, a neighborhood skate park, or a French Quarter misstep. In the end, it comes down to the same thing: understanding the brain well enough to appreciate the scope of its complexities while simultaneously having the humility and perspective to admit what you don’t know, expect to be a challenged, yet still find a way to provide medical care to the best of your abilities.

Stephanie Beckert at the Women’s 5000m final by Robert Scoble. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Stephanie Beckert at the Women’s 5000m final by Robert Scoble. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In the past week, you may have already had the chance to watch some of the world’s best athletes do some truly amazing things. In the days to come, hopefully you can watch some more. When you do, take a moment to appreciate what is allowing them perform, at the brain level. Wonder at how many neurons it takes to twist and flip an athlete while first they go skyward, their skis launching them up, and then continue their contortions as they come down again when gravity wins the day. Consider the cerebral networks involved in an ice-hockey game: the visuo-spatial, motor, cognitive, proprioceptive, balance networks (to name a few!). Marvel at what it takes to land a quad jump, have the reaction time and attention to navigate a downhill course at 90 mph, produce the fluidity of movement to win a gold medal in ice dancing. Dancing…on millimeters-thick razor blades!

Then stop and consider what happens when any one of those brains experiences a sudden stop, a deceleration caused by ice, or snow, or an opponent’s elbow. Normal physiological function is impaired if not temporarily halted. The eloquent firing of neurons, allowing each to participate in the formation of a purposeful network, is replaced by sluggish, inefficient recruitment. Inside the brain, the injury is obvious… if only one could be there or measure it! In the outside world, however, we rely on the clinical manifestations of the injury to guide diagnosis and management. Sometimes the clinical effect is obvious; other times its subtle. Still for others, although the injury is present, there is simply no clinical effect at all. The marveled married with the unknown. This is why I love what I do!

Tonight, from the Olympics standpoint, I have the advantage of experience and perspective, so no in-flight uneasiness this time around! From the medical perspective, however, in the weeks to come I’ll really be where I always am, practicing medicine in the intersection of reverence for human accomplishment and respect for the unknown.

Featured image credit: Ivica Kostelić at the 2010 Winter Olympic downhill by Jon Wick. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The neurology of the Winter Olympics appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with composer David Bednall — part 2

We like to get an insight into the musical lives of Oxford composers by asking them questions about their artistic likes and dislikes, influences, and challenges. In part 1 we spoke to composer David Bednall in August 2017 about what motivates him, and how he approaches a new commission. Here he tells us why he wanted to be a composer, the challenges he faces, and his musical guilty pleasures.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments.

Working with Jennifer Pike and Benenden Chapel Choir under my great friend Edward Whiting on Stabat Mater is certainly up there, as was writing my BBC Commission for the Hull City of Culture Festival 2017 (performed by James Gilchrist, Philip Dukes, and Anna Tilbrook). Another was hearing performances of my 40–part motet, Lux orta. Perhaps the proudest moment of all was being at the premiere in Gloucester Cathedral of the Nunc dimittis that I wrote to accompany Finzi’s Magnificat. Gloucester Cathedral is probably the most important place on earth for me in terms of music. Finishing my first Times Crossword was one of them as well!

Which of your pieces holds the most significance for you?

Hard to say – there are a number of “staging posts.” My milestones are probably Missa Sancti Pauli, Requiem, Welcome All Wonders, Stabat Mater, and Lux orta. Some of my other pieces, written about someone close to me, have great personal significance.

David Bednall by Jerry Butson. Used with permission.

David Bednall by Jerry Butson. Used with permission.What or who has influenced you the most in your life as a composer?

Herbert Howells and Vaughan Williams, without a doubt. I consider Beethoven to be the greatest composer who ever lived, and I would not be one without Wagner or Puccini. In terms of people I know, David Briggs, Malcolm Archer, and Dr Naji Hakim are those who most formed my musical personality, and Professor John Pickard (who was my PhD Supervisor) has had an immense impact on my approach to composition. None of this would have happened at all without my parents, of course, whose love and support have been constant and absolute. They, along with other family members and friends, have sat through many hours of concerts in freezing buildings on hard chairs over the years. I’m immensely grateful to them all.

Have the challenges you face as a composer changed over the course of your career?

I think composing gets tougher as you progress in your career for two main reasons. Firstly, as bands always say, you have a lot of time to make your first album and a lot less for the second. You have many ideas when first starting out and usually pour them all into every piece. I don’t like repeating myself, so I try to avoid doing so whenever possible which makes thinking of new ideas inevitably tougher. Secondly, your own standards become more and more stringent as you begin to demand more of yourself. You also have the challenge of living up to earlier successes and this spurs you on, I think.

What made you want to be a composer?

My first piece of serious writing was Behold O God Our Defender, which was written the day after the 11 September terrorist attacks in the US. My call to be a cathedral organist came while listening to Howells’s Collegium Regale Te Deum. At the word ‘comforter’ I had the call!

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

Being an astrophysicist was on the cards for a long time. I also quite fancied law, and possibly forensics.

Is there an instrument you wish you had learned to play, and do you have a favourite work for that instrument?

Viola, probably. Vaughan Williams’s Flos campi is the last piece I would like to hear before I pass, if it is possible. I am totally in love with the instrument, and have been fortunate to work closely with Philip Dukes, who played the solo viola part in my Requiem.

What would be the top three pieces on your desert island playlist?

Howells: Hymnus Paradisi, Wagner: The Ring (can I have that?), and Vaughan Williams: Flos Campi. I’d want to take an Oasis album as well . . . And Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis would be sorely missed.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

I’ve strived for clarity more and more, and also tried to keep things “thinner” if that makes sense – less is more. This doesn’t mean any less richness of harmony, but I’m always considering whether it’s possible to create the same effect without simply resorting to thicker chords. I am also more interested now in avoiding the constant “vertical” (which seems to be a feature of a lot of music these days) by trying to incorporate a strong contrapuntal element.

What was the last concert you attended?

It was a concert entitled “Untune the Sky: A Hymn to St Cecilia” performed in Clifton Cathedral, Bristol by the choir of a friend of mine; it was very beautiful. The last major performance I went to was Verdi’s Otello at the Royal Opera House with Jonas Kaufmann in the lead role.

Which composer, dead or alive, would you most like to meet?

I would like to have met Howells, and to have been in a room with Wagner once – he was (in my opinion) obviously a bizarre and in some ways deeply unpleasant person, but I would love to have seen the charisma in action. The composer I would most like to have met though would undoubtedly have been Ralph Vaughan Williams – a genuinely great man as well as one of the greatest of composers.

What do you listen to as a “guilty pleasure”?

The Beatles, Oasis, Led Zeppelin, and the Rolling Stones don’t count! ABBA, Meat Loaf, and a fair bit of 80s pop. I don’t suffer any guilt though!

Featured image credit: Music Notes manuscript pencil by Labutin Art © via Shutterstock.

The post A Q&A with composer David Bednall — part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Freemasonry and the public sphere in the UK

Freemasonry once again hit the headlines of UK media on New Year’s Eve 2017, revealing the contentious nature of the place of secrecy in public life. Just having concluded the celebration of its tercentenary anniversary year, the United Grand Lodge of England found itself at the center of a new (and simultaneously very old) controversy (in fact dating back to 1799). How far can membership in a masonic lodge be regarded as incompatible with the exercise of a public office? Is there any place of a secretive organization in a society demanding transparency? Or are the perceptions of incompatibility rather a sign of broken societal and mutual trust in times of political crisis?

The outgoing president of the Police Federation, Steve White, on 31 December 2017 made claims in the UK media that freemasons were blocking reform in the police force, particularly when it comes to a better integration of women, black, Asian, and ethnic minorities (BAME). Membership of predominantly white and male police officers in masonic lodges was to be regarded as an old boys’ network for self-promotion, posing an obstacle for reform. It should be noted that BAME-people are not excluded from membership in contemporary English freemasonry and that even women have their own masonic orders in England, which a recent BBC-documentary screened in November 2017 revealed to the general UK public.

What followed upon White’s sweeping claims was a string of reactions in the form of further articles, opinion pieces, and official statements culminating in early February 2018. This is not the place to counter White’s and other opinions (and circumstantial evidence) on the matter, but rather to look back at the UK-specific context that charge them with meaning and a long history of ideas dating back to the decade immediately after the French revolution.

In a nervous attempt to identify scapegoats who could be blamed for the outbreak and violent development of the French revolution between 1789-1793, the spotlight was almost immediately directed towards groups in society that appeared to have undermined the ‘old regime’ of Crown and Church, or even worse: to plot against human society as a whole. For a host of post-revolutionary writers, it was important to explain how reason and rationality of the enlightenment in a (weird) combination with heated esotericism had created an atmosphere preparing for the ultimate collapse of conventional social, cultural, religious, and political order.

Whereas freemasonry previously had been attacked by both Catholic and Protestant authorities and in some European states had been subject to governmental regulation, masonic lodges were now amalgamated with the first and powerful political conspiracy theory in modern history. Together with the infamous Bavarian Illuminati, freemasons were accused of pulling the wires behind a profound and game-changing political event with repercussions for political order across Europe. These ideas were popularized and disseminated during the 1790s and reached the UK through the writings of a French exiled Jesuit, Abbé Barruel and his friend, the Scottish professor John Robison, and his influential book with the self-explaining title Proofs of a Conspiracy (1797). Under the impression of imminent French invasion (one of the master narratives in British political mythology), in connection with the Irish Rebellion and the revelation of revolutionary groups in Britain, such as the societies of United Irishmen/Englishmen/Scotsmen, the public opinion turned against the existence of secret societies in general and against freemasonry.

Freemasons Hall 2 by Tony Hisgett from Birmingham, UK. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Freemasons Hall 2 by Tony Hisgett from Birmingham, UK. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.It appears as if Prussian legislation against secret societies from 1798 prompted the British parliament in 1799 to adopt the ‘Unlawful Societies Act’. The Unlawful Societies Act outlawed any societies with secret forms of organization that required their members to take an oath of fidelity, or to pledge allegiance to unknown superiors. In both regulations however, freemasonry was exempted but placed under governmental scrutiny. But more importantly the Unlawful Societies Act (in place until 1967) made it mandatory for masonic lodges to report their membership to the Clerk of the Peace in different counties.

This could all have been history if not two books appearing during the 1980s and 1990s, The Brotherhood and Inside the Brotherhood which made serious allegations against the British police force and its alleged collusion with freemasonry, a motif percolating down to popular culture. Prompted by perceived miscarriages of justice, the Home Affairs Committee at the end of the 1990s issued two reports together with a recommendation of disclosure of masonic membership for offices in the judiciary. These rules were later to be found conflicting with European Human Rights Standards and withdrawn in 2007. Only ten years later, the debate has obviously retrograded to the status just before the new millennium.

The question remains why membership in freemasonry still is imagined to be incompatible with holding a public office in the UK? What creates the persistent uneasiness in the public perception of freemasonry today and what might it tell us about contemporary political culture? To this there are a number of possible explanations: First of all, we must understand the imagined incompatibility in its UK-specific historical context that had a legislation of disclosure in place between 1799-1967. Secondly, it appears as if the Home Affairs Committee reports around 2000 and the European Human Rights jurisdiction from 2007, together with a greater transparency from the side of masonic organizations as well as the increased availability of sound research into freemasonry has not removed deeper societal fears among the general UK public. Without taking the issue too far, it is furthermore possible to identify persistent fears towards secretive forms of association as a token of broken mutual and societal trust. In the contemporary and confusing times of post-Brexit and fake-news, the suggestibility exercised by conspiracy beliefs remains high and is a gauge of the prevalent level of ‘paranoid styles of politics.’

Featured image credit: Praha Nekazanka Freemason Symbolism by Txllxt TxllxT. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Freemasonry and the public sphere in the UK appeared first on OUPblog.

February 15, 2018

Outreach ideas by librarians, for librarians

For university libraries, it can sometimes be difficult to get students—especially new students—comfortable with coming into the library and engaging with library staff. We asked some librarians how they get creative with their student outreach to welcome students to campus and to the library.

Maria Atilano, Marketing and Student Outreach Librarian, Thomas G. Carpenter Library, University of North Florida

The University of North Florida’s Thomas G. Carpenter Library hosts an annual “Week of Welcome” event targeted to new and returning students. Titled “Breakfast at Tommy G’s,” the event takes place during the first week of classes and is planned with and marketed by the University’s Office of Campus Life. Major objectives of the Breakfast include interacting with students in a fun and personal way, while also introducing elements of learning and assessment.

Students are asked to visit three information stations where they are told about key library services and resources, such as research help, collections, ITS support, and more. After visiting the stations, they fill out a quick survey before receiving their free food. Survey questions include how they learned about the event, their class year, what they learned during the event, and what ways can the library help them succeed academically.

For the past four years, the event has reached a growing number of students. This past year’s event on 22 August reached a total of 223 students, and survey results were extremely positive. Not only are students thankful for the donuts, coffee, fresh fruit, and free items, but they also always learn something new about the library they can use throughout their college career.

Photo courtesy of Maureen Rust, Student Engagement and Community Outreach Librarian, James E. Brooks Library, Central Washington University.

Photo courtesy of Maureen Rust, Student Engagement and Community Outreach Librarian, James E. Brooks Library, Central Washington University.Liz Svoboda, Interim Head of Circulation & Reference Librarian, Frances Willson Thompson Library, University of Michigan-Flint

At the University of Michigan-Flint, we are trying to revive our outreach to students. Over the past three years, we have had a couple of standard events for finals (90 Hour Library and therapy dogs), but we wanted to do more throughout the semester. We started small by getting some promotional items and attending summer orientation resource fairs as well as the annual Fall Mgagement fair, where all the departments and student clubs have tables. Our goals were being present and friendly and trying to reach as many new students as possible.

This past fall, we kicked it up a notch by handing out candy to students who activated their student ID in our ILS for National Library Card Sign-Up Month and held the event “Selfie with a Skeleton,” which highlights our newest student suggested acquisition, while being quirky and fun. We’re trying to make the library seem more approachable and to be more responsive to student needs and requests, but at a slow pace so that we can sustain our efforts.

Maureen Rust, Student Engagement and Community Outreach Librarian, James E. Brooks Library, Central Washington University

Brooks Library welcomes our students back to campus the second day of each quarter by hosting a food and information giveaway at the library entrance. If the weather is warm, that may entail ice cream or Freezie Pops. The chilly temps of winter quarter means cocoa and cookies are served. We set up a table in our entrance and fill it with sweet treats and handouts, and staff it with friendly library faculty, administrators, and staff. It gives us an opportunity to wish our students “good luck” for the coming term, and to promote our student events planned for that quarter.

In early fall 2016, we partnered with Student Success to promote their new “Traditions Keeper” program by setting up tables outside the library entrance to distribute popcorn, traditions booklets, and library information, all accompanied by tunes from our campus radio station, 88.1 The ‘Burg.

We post promotional flyers throughout the library and across campus and campus online events calendars, and schedule radio announcements on 88.1.

By welcoming our students back with these events every quarter, we remind them they are the reason we are here, that the library is a welcoming space, and that we care about their success in reaching their educational goals.

By welcoming our students back with these events every quarter, we remind them they are the reason we are here, that the library is a welcoming space, and that we care about their success in reaching their educational goals.

Jessica Hayes, Head of Public Services Librarian, Auburn Montgomery University Library

In the summer of 2017 we organized a Board Game Day that would not only welcome students and introduce them to the library, but also provide them with a fun and relaxed time to hangout with librarians, library staff members, and other students.

On the day of the event, library staff members were active participants. They greeted students, popped popcorn, gave library tours, and provided detailed assistance with learning how to use the library resources. However, the volunteers’ main task during the entire event was to assist in creating a comfortable and relaxed environment for attendees, most of whom were new AUM students, and help reduce the innate library anxiety most students have when encountering academic libraries/librarians. In this task, the volunteers succeeded greatly.

To encourage the students to relax, librarians and library staff members dressed in jeans and t-shirts or their AUM Library polo shirts. I typically wear business formal or business semi-casual attire, but at this event, I wore a pair of jeans, tennis shoes, and a Doctor Who t-shirt, which thrilled a lot of the students who attended, and started discussions about the “Whovian” universe. The library volunteers actively participated in all games. This led to a lot of joking and laughing, which allowed students to see that library employees are just humans and there is nothing of which to be afraid.

As a closing example of this event’s success, the very next day after the board game event, two students who attended came to my office seeking help. There had been someone at the Reference Desk but because they already felt connected to me, they specifically sought me out for assistance. That entire first week, they visited me to receive help on various other new semester issues. Weeks later, we still interact and engage with each other when we see one another in the Library or around campus.

Featured image credit: La Trobe University Library by andrew_t8. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Outreach ideas by librarians, for librarians appeared first on OUPblog.

Cosplay is meaningless

Consider the first of the two images on this page. It’s a photo of a young woman in Japan. She is wearing a recognizable look — in this case, the “French Maid” look. We might be tempted to say this girl is play-acting with her clothes. But let’s be clear that this is not the same as wearing a costume on stage or screen; the girl is not turning herself into a ham-actor, as people do at fancy dress parties. An actor in a drama is taking part in a fiction. The audience, as they follow the plot, draw their inferences from the actions of the character the costumed actor is depicting. But for spectators of the “French Maid,” the inferences will be about the action of wearing that particular look, much more than about the imagined action of the character suggested by the look. This young woman is sending a message about herself; she is intimating group affiliation and something about her character and tastes.

Maid In Japan by ThisParticularGreg, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Maid In Japan by ThisParticularGreg, CC BY-SA 2.0 via FlickrNow consider the contrast between the first and the second of the two images. The second is a photo of a “cosplayer” dressed in character as a girl-warrior. (Alas, the photo is uncaptioned, so I cannot tell you which girl-warrior.) “Cosplay” is short for “costume play”; players dress up as a favourite character, typically a fictional character taken from manga, comics, anime, or computer games. Cosplayers gather for photo and video shoots and compete at formal events, where they strike poses suited to their chosen character. Differently from the “French Maid,” their costume play represents a particular character rather than just a style.

yls_6019 by Neef. Public domain via Flickr

yls_6019 by Neef. Public domain via FlickrThere is still a difference, though, between what the cosplayer does and what an actor in a movie does. Cosplayers use only their appearance to evoke the imagined action of the character they play; they strike poses, but those poses do not make up a story. At some competitions, admittedly, cosplayers may perform brief skits or mimes in character. None of this amounts to a story, but it does resemble what a guest at a fancy dress party might get up to — and I compared that behaviour to the performance of a ham actor. Some cosplayers, then, do at times cross the line and turn themselves into actors. But the essence of the practice seems rather to consist in costuming yourself for the perfect character-pose.

What, then, are the inferences generated in an audience by that core practice? On the one hand, because there is no story to follow, they are, in their way, inferences about the action of wearing that particular look, as with the “French Maid.” Those in the know will recognize which fictional character the player is evoking and judge the player’s skill in reproducing and realizing the look of that character. Despite the vividness of the reproduction, the audience continues to draw its inferences from the actions of the person playing the role, rather than directly from the role being played. The player does not disappear into the imagined action of a story as an actor would.

On the other hand, there is an aesthetic simplicity, a wholeheartedness to cosplay that is absent from our “French Maid’s” style. However devoted she is to perfecting her style, she is also sending a message about herself (which, too, is a good thing in its own way). Cosplayers, by contrast, I’d say are not out to intimate something about themselves, or, for that matter, about anything else. Cosplayers are dressing primarily for beauty, or at least for visual impact. They are out to capture the sheer excellence of a very particular look — the look of a known fictional character. Of course, which character they choose to reproduce implies something about their enthusiasms and helps them meet fellow enthusiasts. But to say that this is the point of their efforts would be like saying Monet’s paintings of water-lilies were made to show the world his enthusiasm for gardening and to score an introduction to the local horticultural society. No: instead, cosplayers are aiming to perfect the pure art of dress-up. Their art is pure in the sense that it is free from the need to send messages, to make meaning. Its beauty is delightfully meaningless.

To be sure, some people in their ordinary, daily lives strive to make an art of dressing themselves, guided by an eye for beauty. You don’t have to be a cosplayer to have this ambition. And dressing purely with an eye for beauty—dressing in a way that is satisfying to the senses, flattering to the form, and constitutes an exercise of intelligence—is not something people do in order to send a message. They will surely want to satisfy the viewer as well as themselves, and they may also want the beauty of their outfit to impress or even to astound. But effects like this are a matter of using your clothes to get others to feel a certain way; and that is different from using your clothes to get something across to others.

But dressing as an art can almost never be aesthetically wholehearted. That’s because an actual life, the life of the clothed person, is crucially involved. To dress yourself is inevitably a matter of choosing, say, a jacket where you might have chosen a cardigan, décolletage where you might have chosen a turtleneck. It’s to choose a look; and the look will trigger inferences about the actual person wearing the clothes. It can’t simply be to choose beauty—not unless you take extraordinary measures. Cosplayers take those measures. For the rest of us, sending messages with our clothes—intimating something about ourselves or about the situation in which we find ourselves—will be a normal part of why we wear clothes in the first place.

Headline image credit: Photo by Matias Tukiainen CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr

The post Cosplay is meaningless appeared first on OUPblog.

The US led liberal international order is in crisis

One year into President Trump’s administration serious questions are being asked about the nature and extent of the ‘crisis’ of the US-led liberal order, and its hegemonic state. The most fervent proponents of that order – liberal internationalists – are in varying states of despair. According to their Whiggish narratives, the order was supposed to be open, universal, prosperous for most, and integrative. After the Cold War’s end, the triumph of liberalism seemed all but certain. Though success bred its own international challenges, liberals were ready for them. China, India, and the rest of the BRICS, not to mention South Korea, Indonesia, Mexico, and Turkey (until recently), among others, continue to be seen as success stories of the order. Despite dark Realist mutterings of inevitable military conflict between extant and rising hegemons, liberal optimism remained. Until November 2016.

What is most shocking to liberals is that the significant threat appears to be at ‘home’, i.e., in the western heartlands: First, Britain voted to ‘Brexit’ the EU; then Trump defeated liberal-order champion Hillary Clinton. For the first time since 1945, a US President won office by attacking the principal relationships that are the very sinews of established order – NATO, American Middle eastern policy, East Asian security treaties.

President Trump’s “America First” foreign policy and a governing style favouring illiberal and racialized authoritarian-populism, rather than tolerance and diversity, is narrowing American identity around the macho (angry) white male, being restored after decades of ‘humiliation’ at the hands of “usurpers.” Women’s rights, civil rights, immigrants, and liberal elite social engineering that ‘emasculated’ the American white man, tampered with the constitution and under the banner of diversity changed the very face of America.

The ‘other’ is a Muslim, refugee, terrorist, Mexican immigrant, the unwanted African and Haitian – when the immigrants Trump wants look like Norwegians, a position applauded by white supremacists. A recent Gallup poll shows the effects – collapse in America’s global approval from 48% in 2016 to 30% today, just above Russia, slightly behind China and significantly trailing Germany (43%).

The levels of social and economic inequality at home – alongside the crisis of ‘immigration’ and forced migration – much of it driven by war, poverty and military violence – makes a lethal political cocktail that has bred and encouraged leaders promoting right-wing xenophobic populism, challenging liberal norms.

Yet, those crises may have been predictable given fault-lines fundamental to the liberal order. Some are inherent in an expansionist liberalism – spreading its democracy and market economics across the world, creating its own competitors and challengers in the process, leaving nowhere for American and other western states to export their crises.

Other crises occurred because the promise of the liberal order was unequally shared. The liberal world order turned out to be the West plus Japan and pro-US South Korea. Large parts of the ‘periphery’ (across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, for example) did not share in the liberals’ bounty. That post-1945 era sublimated its colonial-era racialised-imperial impulse – embedded in the distribution of power within international institutions and the terms of trade, as well as the extraordinary violence during the North American-Western European ‘long peace.’

For the first time since 1945, a US President won office by attacking the principal relationships that are the very sinews of established order – NATO, American Middle eastern policy, East Asian security treaties.

Yet the western ‘fix’ in the 1970s to the challenge of post-colonial nations’ demands for a New International Economic Order – leading to the export of capital to the global south through loans and investment in ‘middle class’ third world states, not only created competitors but also aided the industrial job-destruction process kick-started by automation: rust belt areas lost jobs and suffered socially. White working and middle classes drifted politically towards the Republicans, whose subliminal racialised appeals – against ‘reverse discrimination’, for example, nurtured a grievance at loss of position, viewed as others gaining unfair advantages over ‘real’ Americans. The seeds of the Trump triumph of 2016 were sown in the decline of the postwar social contract that initially fuelled Reaganism – and small government and low taxes conservatism. The wages of whiteness however delivered little in material terms to Reagan Democrats. And combined with globalisation and automation, their living standards fell, along with other large swathes of American society, as corporate wealth and political power increased.

President Trump’s ‘principled realism’ – sketched out in his inaugural address through the speech to the UN General Assembly in September, to his first National Security Strategy of December 2017, and General Mattis’s National Defense Strategy of January 2017 – is unilateral, selectively internationalist, and heavily militarised. It is also extractive, transactional, and based on American hard power. Trumpism is a kind of social Darwinism: unregulated corporate power with militarised policing at home; armed and dangerous states abroad eschewing diplomacy, loosening the bonds of international norms, underpinned by a survival-of-the-fittest mentality.

As his support erodes in practically all parts of the electorate, the legitimacy of American political and financial elite declines, and America’s global standing slips below China’s, Trump is pursuing a more militarist strategy against China and Russia – which he has labelled ‘revisionist’ powers, and closing down diplomatic pathways in dealing with major global crises. The growing threat of war, the downgrading of diplomacy and extolling the virtues of a global ‘national awakening’, augurs ill for the future of world politics, with strong undertones of worship of ‘strength’, ‘nation’ and ‘God’.

There is little room for soft power in Trump’s foreign policy; diplomacy has been side-lined in favour of military solutions. And America’s attitude to international organisations is ambivalent. Thus far, however, the effects have not fundamentally altered the international order – but President Trump’s withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Climate Accord, UNESCO, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and selective engagement with other international institutions suggests a loosening of the international order created by Anglo-American power after World War II.

The title of a major report for discussion at the January 2018 meetings at Davos, based on a survey of global elite opinion, is ominous for the future of the international system: “Fractures, Fears and Failures.” The report’s subheadings include: “Grim Reaping,” “The Death of Trade,” “Democracy Buckles,” “Precision Extinction”, “Into the Abyss”, “Fears of Ecological Armageddon” and “War without Rules.”

Featured image credit: Flag of the United States by Quintin Gellar. Public domain via Pexels.

The post The US led liberal international order is in crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

February 14, 2018

Questions and answers: January 2018 etymology gleanings

The question concerned the root rō– that is said to underlie the English words oar and row. Where did the root come from? This question is almost equal to the more basic one, namely: “How did human language come into being?” The concept of the root is ambiguous. When we deal with living languages, we compare words like work, works, worked, rework, worker, and the rest and call their common part their root. The botanical metaphor in linguistics (root, stem, branch, etc.) is old. But when we open a historical dictionary, we are given the impression that the roots existed before the words that contain them, that roots generate words. Rō– looks fine as the root of the ancient forms of oar and row, but did this egg come before the chickens we can observe? Only sound-imitative and sound-symbolic roots are “real”: oink-oink, bang, kap ~ kop, and their likes. The question about the origin of rō– cannot be answered with certainty. Perhaps it indeed existed and imitated the sound made by an oar in water, but we cannot know.

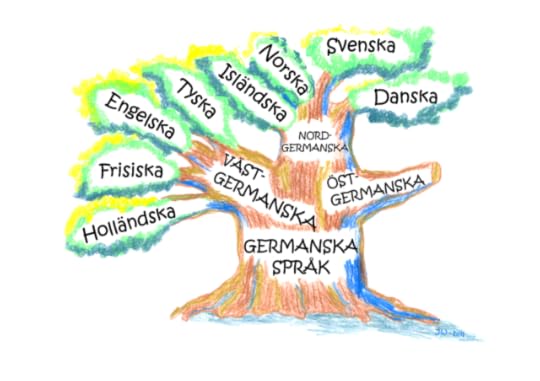

Triumph of the botanical metaphor. Image credit: A simplified language tree covering the Germanic languages, intended for elementary school by Ingwik. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Triumph of the botanical metaphor. Image credit: A simplified language tree covering the Germanic languages, intended for elementary school by Ingwik. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The origin of the verb to have

This verb has exact cognates in all the Germanic languages, but initially it did not mean “to possess.” For “possession” Germanic used the verb that in fourth-century Gothic sounded as aigan, so that Modern German eigen and Scandinavian eiga (as in Icelandic) are its closest relatives. Their English congener (owe, from āgan) has changed beyond recognition, and its checkered history need not concern us here. The adjective own shares the root with the homonymous verb. Another descendant of Old Engl. āgan is ought; its connection with owe has been forgotten.

The oldest form of the verb have was haban (so, for instance, in Gothic). Two clues to its origin exist. Clue No. 1. Next to haban, Gothic had the verb hafjan “to lift” (its cognates are Modern Engl. heave and German heben). I will state the next fact without any explanation, in order not to clutter the story with cumbersome details. Hafjan is a derivative form, traceable to haban. One can expect some connection in meaning between the initial and the derivative forms, but a tie between “lift” and “possess” is weak. This is the first indication of the fact that Germanic haban did not mean “to possess.” Clue No. 2. In dealing with Germanic, we always try to find a word’s cognate outside the Germanic group: some related word in Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Celtic, Slavic, or elsewhere. Here we immediately notice Latin habeo “to have.” But our joy is premature. According to the rule of the First Consonant Shift, Germanic h should correspond to non-Germanic k. For instance, the Old English cognate of hwæt is Latin quod (that is, kwod). Both mean “what.”

Oink-oink: an ideal etymology. Image credit: “Pig Alp Rona Furna Sow Happy Pig Animals Nature” by Mutinka. CC0 via Pixabay.

Oink-oink: an ideal etymology. Image credit: “Pig Alp Rona Furna Sow Happy Pig Animals Nature” by Mutinka. CC0 via Pixabay.Before the discovery of such basic rules as the rule (or law) of the First Consonant Shift, look-alikes constantly seduced language historians. We now know that too much similarity can be detrimental to establishing affinity. Though a possibility exists that in such cases we are dealing with a borrowing, it would be rash to posit a loan of such a basic word as have. Also, as I have noted more than once, if we suspect that a word wandered from one language to another, we have to explain why a borrowing was needed and under what circumstances the process took place.

To return to our law: for h in haban we need k outside Germanic, and for b (which in this word designates v, from f) we need p. Latin obliges us at once with the verb capio “to catch, seize, grab.” Habere remains an odd man out, and I’ll return to it in a moment. The etymological match between haban and capere suggests that the verb’s initial meaning was approximately “to catch.” The connection between haban “to catch” and hafjan “to lift” poses no difficulties. Apparently, the recorded meaning of haban and its Germanic cognates is the result of a later development.

Latin habeo is not only an odd man out but also a thorn in the flesh. Granted, haban and habeo are a bad phonetic match, but their phonetic and semantic proximity (actually, near-identity) is almost too good to be untrue. That is why many moderately successful attempts have been made to connect them. Similarities between Latin and Germanic are many. The same is true of their legal systems. It is not impossible, even though not very probable, that, while the two tribal unions remained in close contact, the original meaning of haban fell under the influence of its Latin near-homonym. Or there may have existed a common (“Indo-European”) verb beginning with gh– that was conflated with the reflexes (descendants) of the kap– forms. All this is intelligent guessing. Only one thing is clear, the earliest Indo-European kap– verb did not mean “possess.”

Hemingway predicted our dilemma but did not solve it. Image credit: 1st edition cover via The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.

Hemingway predicted our dilemma but did not solve it. Image credit: 1st edition cover via The Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association. Fair use via Wikimedia Commons.Mad as a hatter

I have now read the comment by Mr. Pascal Tréguer concerning the idiom mad as a hatter (the post for 24 January 2018). He too expressed doubts about the connection between this idiom and mercury poisoning, and what he said was partly new to me. I did not know that the reinforcing phrase like a hatter had at one time been used so broadly in northern and Scottish dialects. I am grateful for his remarks, especially because they led me to his blog “Word Histories,” of which I had been unaware. However, let me repeat: I have no chance of discovering the comments added some weeks, months, and years after the appearance of a certain post. This time, I was licking my plate clean for “questions and answers” and went a month back. Those who have late comments are tearfully asked to alert me to their existence in some way or another. The discussion about a mad hatter is for the moment closed. Those who disagree with my reasoning are welcome to believe in the now current theory. And no, I don’t use this phrase and never heard it from anyone.

The German family name Fartle

A German family having this name arrived quite some time ago in America and for obvious reasons did not want to retain it (they changed it to Hartle). The question was about the name’s origin. I have several very full explanatory dictionaries of German surnames, but none of them mentions Fartle. The parts of my own suggestion, unfortunately, do not cohere. The –le in Fartle made me think that those people had come from Swabia or some other southern part of Germany, and I thought that the root meant “fart” even in their homeland. The German for “fart” is furzen. Its z is the product of the specifically German change known as the Second Consonant Shift (compare Engl. to and German zu), so that t in Fartle poses no problems, but only assuming that the name is northern (the German shift loses its force around Cologne/ Köln). Thus, I ended up with a northern German root (t for z) and a southern suffix. Nor is the vowel too good for my conjecture: a is English, as in fart; Swedish has fjärta and dialectal fräta, and I could not find a German dialectal form of this verb with the vowel a. But that obstacle is not fatal. If some of our readers know the origin of the puzzling name, their response will be welcome.

German ß

I did not quite understand the comment on my remarks. The pair (ver)ließen ~ (ver)lasen probably has different consonants everywhere in Germany (voiceless ~ voiced, strong ~ weak, or whatever). Given the traditional German spelling, ambiguity arises in words like Fluß “river” (the old spelling) versus Fuß “foot,” because Fluß has a short vowel, while in Fuß, u is long. Foreigners confronting words like Ruß “soot” cannot know how to pronounce it. For consolation, I may add that foreigners coming across the English word soot don’t know the vowel length either: oo designates a long vowel in mood, but a short one in foot and good.

Finally, I would like to thank our correspondent from Hong Kong, who assured me that, even though I receive relatively few questions, many people read the blog.

Featured image: Hong Kong, we appreciate friends from far and near. Image credit: “Hong Kong China Night Cityscape Coastline Coast” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Questions and answers: January 2018 etymology gleanings appeared first on OUPblog.

Want to know the Latin for “true love”?

Then Ovid is your man – and woman, as the case may be …

Fidus amor. That’s “true love” in Latin. Historically, such love is often claimed to have emerged with the troubadours of twelfth century Provence. The troubadours used the Occitan term fin amor for this kind of love rather than the more famous amour courtois, “courtly love”, which is a modern concoction. However, “Fin amor”, is “derived from Latin fidus, ‘faithful’. Originally, fin amor was admirable and refined because it was faithful, by definition.” So the term, fin amor, comes from Latin, as do many in the romance languages.

But did the ancient Romans, for whom Latin was their mother tongue, have an idea of “true love”? A search for the combination fidus plus amor in the database Classical Latin Texts, yields only one exact match.

This match is however as unique as it is significant: it occurs in a line from the Roman poet Ovid’s second Heroides (“Heroines”), an elegiac letter written from the Thracian princess Phyllis (the aforementioned “woman”) to the Athenian king Demophoon. They had been lovers, but he has sailed off – and promised her to return within the month. When Phyllis writes her Heroides letter, however, many months have passed. How could it take her so long to realize that he has abandoned her? Her fidus amor, “true love” – as in “true to”, “faithful”, and “loyal” – she has been inventing all kinds of imaginary obstacles hindering Demophoon from returning to her. Thus, the idea of fidus amor is linked to a female figure besieged by deceit, lament, and tragedy. Eventually accepting that she has been abandoned by her beloved, Phyllis will end her life by hanging.

Phyllis abandoned by Demophoon. Miniature from the Heroides of Ovid (Octavian translation Saint-Gelais, 1496-1498). National Library of France (BNF). Riveriera: French 874, Folio 15v. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Phyllis abandoned by Demophoon. Miniature from the Heroides of Ovid (Octavian translation Saint-Gelais, 1496-1498). National Library of France (BNF). Riveriera: French 874, Folio 15v. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ovid is the most prolific Latin poet of antiquity and one of the greatest writers on love of all time. Strikingly often, he merges his voice with that of female figures, as in his Heroides, which is among his earliest extant works and rewrites the entire literary history up until his own time – from a female perspective.

Notably, Phyllis, the first known figure in Western literature who claims to possess fidus amor, re-emerges in all of Ovid’s works that are conventionally known as his love poetry. In the Amores (“Loves”), the poetic “I” roams ancient Rome under the poet’s , Naso, in pursuit of the elusive Corinna – and brags about earlier literary achievements, such as his second Heroides and its evocation of Phyllis’ tragic, faithful passion. In his Ars amatoria (“The Art of Love”), Ovid poses as a Professor of Love (praeceptor amoris), and in his Remedia amoris (“Cures for Love”), he tries to renounce his favorite theme, love, possibly due to the censorship of the emperor Augustus. In the two last works, Ovid professes that he could have saved Phyllis if he had only had the chance to teach her to love wisely (sapienter amare).

The rich variety of Ovid’s portrayal of love – as violent and tender, hetero- and homoerotic, beastly and divine – means critics have sometimes denied him the honor of calling him a champion of “true love”.

A disheartening example of the antipathy towards the erotic Ovid is the case of the Norwegian poet Conrad Nicolay Schwach (1793-1860). During almost all his adult life, Schwach tried to publish his translation of Ovid’s Art of Love. His handwritten, still unpublished manuscript lies in the Gunnerus-library in Trondheim and between its leaves there are letters from potential publishers, who all praise the quality of Schwach’s translation, yet turn him down due to the work’s lascivious content. However, although Schwach never reached a wider audience with his Ovid translation, the very fact that he tried proves that even in the nineteenth century, which was oddly Ovid-hostile, the poet still had his friends.

And how could he not? For even if Ovid’s love is cynical, it is also innocent, if it is plight, it is also pleasure. And, if someone should contend that all these kinds of love are not really “true love”, then, in the midst of it all, there is Phyllis, ever-ready to guide us through Ovid’s love poetry – with her fidus amor.

Featured Image credit: Statue of Roman poet Ovid in Constanţa, Romania (ancient Tomis, the city where he was exiled). Created in 1887 by the Italian sculptor Ettore Ferrari. Kurt Wichmann, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Want to know the Latin for “true love”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers