Oxford University Press's Blog, page 277

February 20, 2018

Should public health leaders get on the genomics train?

In the past eight years – a time of swiftly moving advancement in applications of genomics in cancer treatment – the Society of Behavioral Medicine’s Annual Meeting has had one paper session and one plenary on genomics annually (among the average of 270 sessions offered). Additionally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention recommendations of genomic applications that are ready for implementation also went largely unnoticed by the health promotion community. Why might these recommendations be important to health promotion? Tier 1 genomic applications, backed by strong evidence of their clinical utility, support population screening to identify those at heightened risk for inherited cancers and cardiovascular disease. While accounting for less than 10% of the population, these individuals and families account for disproportionate morbidity and mortality and can benefit from targeted prevention efforts. Thus, the reticence of highly respected public health leaders is worth considering.

Critique 1: Use of genomics applications will eclipse social determinants of health

It is now widely acknowledged that current and historical living conditions and other social factors actually become biologically embodied. In this rendering, genes are followers of social and historical influences rather than the generative force driving health outcomes.

The profile of a patient with inherited breast cancer is reflected in a younger patient presenting with a high-grade tumor that is hormone receptor-negative – characteristics more common among African American women with breast cancer than white women. Some argue this arises as the perfect storm of biology, behavior, and service access. Biology is part of reciprocal and synergistic processes where social exposures turn on gene expression and worsen health outcomes.

Person from dots by mcmurryjulie. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Person from dots by mcmurryjulie. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Critique 2: It is infeasible to disseminate high-tech and expensive genomic applications to populations that bear the greatest burden of common disease

Tier 1 screening for hereditary cancer and cardiovascular disease risk relies on relatively low-tech family history-based risk assessments. Indeed, a number of low-cost tools are in use with a broad array of audiences. Only a small subset of these individuals will be appropriate for referral to genetic counseling and testing. Moreover, the potential of these tools to broaden reach beyond the individual disease prevention efforts to engage the broader family in considering risk offers the potential for getting a bigger bang for the buck.

Critique 3: Genomic applications are unlikely to improve health promotion interventions

Systematic reviews of genomics risk information now show that, regardless of the behavior (smoking cessation, dietary habits, and physical activity), there appears to be little benefit of genetic risk information to motivate behavior change. However, health promotion researchers were well poised to conduct this rigorous line of research, work that also provides creative and theory-based approaches to convey a technical jargon not well understood by the public.

Ongoing commercialization of genomics (e.g., companies like 23andMe), high-profile celebrities’ experiences with hereditary cancer syndromes, and popular press coverage will reinforce public expectation that genomics be included in health promotion discussions. Unfolding discovery in the burgeoning field of epigenetics is showing individual variation in response to interventions and propensities to relapse. Whether this new information can inform innovation in health promotion interventions is worth considering.

Conclusions

Health promotion researchers have critical expertise and decades of evidence that will be vital in genomic translation for health promotion. Thus, we will bear some responsibility for inappropriate translation and dissemination if we dismiss genomics. Recognizing this, the Society of Behavioral Medicine leadership has convened a presidential working group to gather members’ perspectives on genomics and how this disciplinary expertise could help shape an optimal translation vision. As health promotion researchers, we have to decide whether to show up and shape research and practice, or sideline ourselves, knowing that both have consequences. In the words of legendary historian and social activist Howard Zinn, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.”

Featured image credit: Geometric by Manuchi. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Should public health leaders get on the genomics train? appeared first on OUPblog.

Putting George Enescu back on the musical map

Even by the standards of musical genius, George Enescu (1881–1955) was quite an extraordinary figure. A musician of a precocity that rivals Mozart or Mendelssohn, Enescu was equally proficient as a composer, performer, and teacher. Remembered nowadays primarily as a violinist, he numbers securely among the foremost instrumentalists of the twentieth century, though by all accounts Enescu was no mean pianist, and a very capable cellist besides. Distinguished colleagues such as Alfred Cortot, Pau Casals, Nadia Boulanger, and Arthur Honegger held his gifts in an admiration that bordered on awe. Evidence as to his conducting skills is preserved on a number of recordings in which he accompanied his young pupil Yehudi Menuhin (he was apparently in the running for chief conductorship of the New York Philharmonic in the late 1930s), and post-war radio broadcasts that have resurfaced in recent decades have lead to considerable critical acclaim. Enescu’s musical memory, meanwhile, was proverbial.

Numerous reports attest to his ability to memorise a new score at sight, and by his own account if left on a desert island with sufficient manuscript paper and a pen, he could have preserved the greater part of the Western musical repertory from memory. It was as a composer, however, that he really wanted to be remembered by others. As a teenager Enescu was writing works of thrilling complexity (witness the Octet for Strings, written at the age of eighteen), which already foreshadow the mature composer’s mastery of musical movement, the contrapuntal richness of his part-writing, and facility at varying his melodic ideas almost constantly throughout this fifty-minute work. When the Royal Opera House staged the composer’s magnum opus, the monumental opera Œdipe, at Covent Garden last year, the event caused quite a stir (“a masterpiece”, “spellbinding”, “truly one of the great operas of the 20th century” enthused the press). Just who was this neglected master capable of writing music of such power and refinement?

Enescu’s gifts and accomplishments were remarkable, yet he is not alone in failing to attain the international status his musical achievements would seem to deserve. Indeed, Enescu’s case is typical of a number of highly talented musicians of his generation, several of whom, like Enescu, hailed from central or Eastern Europe, who have largely been passed over in accounts of twentieth-century music and are only now emerging from relative international obscurity. One reason is geographical and political. As a native of Romania, Enescu has more or less inevitably become typecast to Western European audiences as an “exotic nationalist”, a purveyor of colourful folk-rhapsodies, appealing but ultimately “peripheral” (a fact not aided by the later political divisions of the Cold War). His most famous piece—the widely played and still highly popular ‘Romanian Rhapsody No. 1’—is after all just such a composition, and audiences are rarely given chance to hear any more of his music than this. Conversely, Enescu is understandably celebrated in Romania as a symbol of national pride: statues to the composer abound throughout the land, his birthplace, Liveni, has been renamed in his honour, a leading symphony orchestra is named after him while his name is likewise given to Romania’s showcase music festival, and his image (and music) can even be found gracing the common five lei banknote.

Violinist George Enescu (1881-1955) and pianist Alfred Cortot (1877-1962) by E. Joaillier, Paris 1930. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Violinist George Enescu (1881-1955) and pianist Alfred Cortot (1877-1962) by E. Joaillier, Paris 1930. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Yet in many ways Enescu is more international than national as a figure, both in training and outlook. The precocious child musician had left Romania at the age of eight to study first in Vienna and then in Paris, and for the majority of his life called the latter city his home (he is also commonly known under the French form of his name, Georges Enesco), returning to his native land as an adult for comparatively brief periods. Attempts by Western critics to marginalise him as different (or “other”), as with Romanian audiences to claim him as uniquely theirs, do him equally a disservice.

Secondly, familiar critical categories by which the twentieth century has sought to compartmentalise composers—as late-Romantics like Strauss or Mahler, as impressionists like Debussy, radical modernists like Schoenberg, and neo-classicists like Stravinsky—have little hold on his compositional output as a totality. If Enescu is not simply a Nationalist, he is no more a late-Romantic, an Impressionist, a Modernist, or a Neo-Classicist. Or rather, his music can show elements of all of these—and yet is something else. The richness and diversity of his musical oeuvre collapses such distinctions, leaving him outside our usual narrative framework for understanding its place in history.

How do we understand a figure like George Enescu? Or more specifically, how might we seek to promote such a composer’s music, to create more fitting contexts for understanding it and carving out a unique place in the landscape of twentieth-century music? One such approach may simply be to bypass the familiar, if not now hackneyed, historiographical terms, letting such compartmentalisations quietly rest, and instead listen more attentively to how the music appears to be operating. In particular, we might consider how Enescu’s music seems to be fashioned from a distinctive, if not highly idiosyncratic, relation to the concepts of time and space (an approach with notable precedent in an important recent account of musical modernity). This need not be understood in a manner divorced from history, from the composer’s own cultural surroundings, for he lived in a period in which these notions of time and space were being subjected to radical questioning. For instance, the philosophical thought of Henri Bergson and the debates that it stimulated in France around the time the composer was living there provide ample contexts for interpreting the dynamic, evolving quality of Enescu’s music, as equally the writing of Enescu’s compatriot Lucian Blaga, may prove useful in understanding the gently undulating lines and variative expanse of his art.

Such an approach may allow us to open up the customary narratives of music history in order to provide a conceptual space—a dwelling place as it were—for this most cosmopolitan and prodigiously gifted musician. Even more importantly, it might give some welcome attention to a still unsung but major figure of twentieth-century music, one whose achievements are just beginning to be appreciated now.

Featured image credit: Town castle by Alisa Anton. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Putting George Enescu back on the musical map appeared first on OUPblog.

On our craving for generality

Ludwig Wittgenstein, in his Blue Book, chastised philosophers for what he called “our craving for generality.” Philosophers (including the earlier Wittgenstein of the Tractatus) certainly have exhibited this craving, and despite his admonishment, we continue to do so. Philosophers seek general accounts of the nature of propositions, properties, virtues, mental states–you name it.

Wittgenstein portrays the craving for generality as a kind of philosophical sin, but it is not that. First, it is hardly confined to philosophy–scientists crave generality, as do humans generally. Second, it can’t really be a sin–or at least an unpardonable sin–for without knowing anything general, we cannot succeed in understanding or acting in the world. But sinful or not, the craving can be dangerous, because the world often does not cooperate with our generalizations.

The crux of our predicament is this: nature is heterogeneous and particular, but epistemic and practical needs require us to generalize. To say that nature is particular is just to say that one thing is not like another. Each cell, each bird, each child, each family, each society is different from the next. Even in the physical sciences, anything with any complexity is heterogeneous–no two materials or solutions are just the same. But in spite of this heterogeneity, we must generalize, and often do so with great success. We use randomized controlled trials on one population to predict the effect of an intervention (like a medication) on a different or larger population. We use model organisms from e coli to drosophila to rats to understand our own biology. We use information from one earthquake or volcanic eruption to predict the behavior of the next. But such generalizations have their limits. A treatment that works on one patient does not work as well on the next, and our knowledge of past earthquakes and eruptions are far from sufficient to predict when the next one will happen, and how bad it will be.

Wittgenstein thought that philosophers are drawn to make general claims in part because they wish to emulate “the method of science,” which he took to involve “reducing the explanation of natural phenomena to the smallest possible number of primitive natural laws.” Wittgenstein’s vision of science is in the spirit of logical empiricism and the unity of science movement–conceptions of science that dominated philosophical thinking for much of the twentieth century.

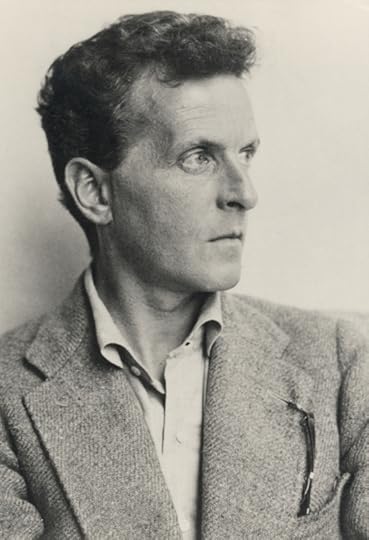

Ludwig Wittgenstein by Moritz Nahr. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ludwig Wittgenstein by Moritz Nahr. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Reflection on the practices of the sciences suggest a different picture. First, most scientists are concerned chiefly not with finding laws, but with understanding mechanisms. Consider Mendel’s so-called laws. These are generalizations that hold broadly, but are subject to many breakdowns and exceptions. To understand why and when they hold, one must understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie gene transmission. Second, and related, scientists are chiefly concerned with the development of models rather than theories. On the logical empiricist conception, theories were understood to be, ideally at least, collections of general laws that truly hold of the domains they describe. Models, on the other hand, are tools scientists use to represent–in partial, abstract and idealized ways–natural phenomena and the mechanisms responsible for them. They offer generality, but of limited scope.

Wittgenstein’s worries about the craving for generality are in some ways reminiscent of Hume’s worries about the principle of induction. Hume argued that inductive inferences are grounded in our unwarranted commitment to a principle of the uniformity of nature. We use past experience to make predictions about future experience, but this can only work if the future is like the past, and we cannot, on pain of circularity, establish by induction that the future is like the past. Nonetheless we persist with our inductions. It is just habit.

The problem with Hume’s way of putting it is that it suggests that in the past nature has always been uniform; we know it has not. The real question is not whether the future will be like the past, but when it will be. On the mechanistic view of generalizations, we get some account of when we can expect the future to be like the past: generalizations about future or unseen phenomena will hold when the mechanisms responsible for those phenomena are similar enough to responsible mechanisms past, and when the conditions that allow for their functioning obtain. Once, for instance, we know how the cytological mechanisms work, we will understand when generalizations like Mendel’s laws will work, and when they will fail.

The Humean puzzle may ultimately be unsolvable, but reflections on when and why generalizations hold and when and why they fail, suggest a more scientifically interesting and empirically tractable version of the Hume’s problem. So, rather than chastising philosophers or scientists for their craving for generality, we should look for an account of nature and of science that make sense of how they manage to satisfy it.

Featured Image credit: Barnacle Geese flock during Autumn migration. CC-BY-SA-2.5 via Creative Commons.

The post On our craving for generality appeared first on OUPblog.

February 19, 2018

A new generation wrestles with the gender structure

What’s happening with kids today? A few years ago, liberals were confidently– and conservatives dejectedly– predicting that Millennials were blurring traditional distinctions between the sexes both in the workplace and at home, operating on “the distinctive and historically unprecedented belief that there are no inherently male or female roles in society.” While 55% of the youth vote went to Hillary, that is 5% less than who voted for Obama. More important, over a third of Millennials voted for Donald Trump despite his having bragged about harassing women on tape. The #MeToo movement’s amazing popularity, with the women involved chosen as 2017 Person of the Year at Time Magazine, suggests that feminism has risen again. Is this feminism a youth movement or still led by Millennials’ mothers? Are young people on board with today’s feminism?

Some sociologists are arguing that today’s young people may be getting more conservative when it comes to gender equality. They noticed that between 1994 and 2014 high school seniors had become more traditional in their ideas about how to organize family life and decision making in the home (Pepin and Cotter 2017). Another report published by the Council for Contemporary Families (Fate Dixon 2017), showed similar slippage between 1994 and 2014 but only for young men. This led to a New York Times headline asking worriedly whether millennial men now wanted stay-at-home wives, and a Washington Post op-ed assuring conservatives that the rediscovery of “gender specialization” is a natural development that reflects the way most families actually work, replacing the egalitarian feminist vision of sharing caregiving and breadwinning responsibilities equally.

So what are the Millennials’ gender politics? My colleagues and I examined the results of a nationally representative sample, the General Social Survey, which asks the same questions every year, allowing us to track tends over time analyzing data from 1977 to 2016. What stood out to us was the virtual collapse of support for the traditional notion that women are suited only for motherhood and homemaking and should be “protected” — or excluded — from the public sphere. Our analysis suggests that the major change in our society is that those who used to believe women belonged in the home and did not deserve equality at work no longer believe that (or at least they no longer admit to doing so on surveys). But those people still do believe that mothers should be primarily responsible for children.

The most important division today is not between feminists who champion women’s right to do everything in the public sphere that men do, and traditionalists who endorse men’s dominance in the world of work and politics, something supported by most Americans for more than 150 years. Today’s debate is between the minority of people who believe mothers are primarily responsible for children and those who wholeheartedly support the sharing of duties in both private as well as public life. Even the most conservative Republicans accepted Sarah Palin’s right to be a vice-presidential candidate, although they did not necessarily accept the feminist premise that marriage itself should be egalitarian, and husbands should be equally responsible for the housework and child care.

The major change in our society is that those who used to believe women belonged in the home and did not deserve equality at work no longer believe that.

Where the Millennials stand on these questions is still being debated. I argue that the Millennials are a generation with as divided gender politics as the rest of the country. In interviews with 116 Millennials, I found that gender stereotypes and discrimination still shape their experiences. The fear of being stigmatized for challenging gender stereotypes is still widespread, but far more among young men than women. Nearly everyone felt the powerful constraint of gender stereotypes when it came to how they display their bodies, from the clothes they wore to the mannerisms they used, to what they weighed and where they had muscle.

Beyond that similarity, there was great diversity in how Millennials wrestled with the gender structure. But that diversity wasn’t really based on the sex of whom I was talking too. Some were very traditional, both women and men, especially those who subscribed to literalist faith traditions. They supported different norms, opportunities, and constraints for men and women as family members. Others were innovators, feminists in belief. They talked the talk, and walked the walk — or claimed to. What makes these innovators different from 2nd wave feminists is that this does not seem to be a women’s movement, but rather a feminist one that includes men.

Perhaps even more distinct, an emergent trend in this generation is a small but vocal group of young adults who reject gender entirely, refusing to “do gender” in how they present their bodies. Some adopt a genderqueer identity, between the binary of man and woman, and dress accordingly. I interviewed several female-bodied, genderqueer Millennials who felt their female body dressed in male clothes became androgynous. Others mixed feminine and masculine styles, such as male bodied persons donning high heels with a beard, or a female bodied person wearing combat boots and short cropped hair, long earrings and a feminine lacy scarf. There is no accurate count of how many identify as genderqueer or non-binary, but a new study from the Williams Institute, a think tank within the UCLA school of law, found that a quarter of California youth were gender non-conforming.

The majority of the young people I interviewed, however, were somewhat unsure about what gender means for them today. Their answers were full of inconsistencies, as full of chaos such as the world they are trying to navigate. Girls today are told they can be anything they want to be, but still feel pressure to be thin, accessorized, and attractive to men. Perhaps this paradox between freedom of career choice and continued expectation to be eye candy helps to explain the continued sexual harassment they face. Gender equality has meant opportunity, including the opportunity to remain an object for male gaze. Boys continue to be stigmatized for doing anything that even hints at femininity, from playing with dolls, to studying to be a nurse. And yet, those same boys are expected to be involved fathers and nurturing fathers. The result is much confusion of just who expects what, and why.

Millennials are as divided in their beliefs about gender as is the rest of America. But while some Millennials may be ambivalent about how far to push the gender revolution, this is not your grandparents’ ambivalence. My data suggest one more commonality among this generation. Whatever they want for their own lives, they are not interested in forcing other people into gendered boxes, or condemning them for choices that violate traditional beliefs about what males and females should do. They seem to have an unprecedented acceptance of the choices other people make to either meet or reject the constraints of gender expectations. What was very clear is that even Millennials who make traditional choices are unlikely to accept a political agenda that penalizes people who do not.

A version of this article originally appeared on The Society Pages .

Featured image credit: Bonding break casual by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post A new generation wrestles with the gender structure appeared first on OUPblog.

George Washington and eighteenth century masculinity

We want George Washington—the President of all Presidents, the Man of all Men—to be a certain way. We want him to be an unalloyed male outdoing, singlehandedly, all the other competitors. We want him strong and rude, rough and rugged, athletic and hypersexualized, a chiseled torso, a Teddy Roosevelt, a Tarzan, and a John Wayne: “a man’s got to do what a man’s got to do.”

The notion that muscular and athletic bodies must define the perennial essence of masculinity has been debated, and increasingly so. Yes, Washington was hard, a real soldier. But we should not overlook that men in the past have lived by different standards. And that men in the future will live, hopefully, by different standards.

We are biased, at best: how many times have we heard Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s famous eulogy, “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen”? How many times have we interpreted this picture as a twentieth century celebration of man’s confrontational “instinct”?

And yet, eighteenth century practices of masculinity—especially white, higher classes masculinity—flirted with femininity and softness, or delicacy, in a way that Hollywoodian idols would deem inappropriate.

Let us start from the beginning. The real George Washington, in his prime, was immensely impressed by Lawrence, his elegant half-brother, a man who could have been easily mistaken for an aesthete. In many ways, George sought to emulate him. Lawrence was graceful and flaunted cosmopolitan habits. He had a soft face and round shoulders. He was slightly paunchy and did not look either muscular or particularly rugged.

In what he sought to embody, in his conscious body language, in his corporeal strategies, in the type of gracious man he eventually became, George was closer to Lawrence than it has been generally assumed: George Washington was this eighteenth century man, after all. Those who had met him, such as the Marquis de Barbe-Marbois, never failed to notice not only his “gentle urbanity,” but more importantly, his graciousness, “which seems to be the basis of his character. … He is masculine looking, without his features’ [sic] being less gentle on that account.”

George Washington had publicly avowed his goal that he wanted to achieve “delicacy”: “I always wished [delicacy] should form a part of my character.” And this meant more than just paying lip service to politeness. Delicacy and gracefulness, for this particular man, were more than a manufactured show cut loose from inner morals. Washington’s graciousness, in fact, reinvigorated the link between inner virtue and outer manners: he was the gracious and delicate man he wanted to appear.

“Portrait of Lawrence Washington, older half-brother of George Washington” possibly painted by Gustavus Hesselius. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Portrait of Lawrence Washington, older half-brother of George Washington” possibly painted by Gustavus Hesselius. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Stiff and distant, when exceptional circumstances dictated, he could effortlessly become approachable and maternal. Unannounced visitors at Mount Vernon marveled at the amount of time this busy man could spend with them talking and smiling—and at the fact that he could easily get quite merry over a few glasses of champagne. It was far from exceptional that guests could be lighted up to their bedroom by the General himself.

This is a savory episode: one guest, oppressed by a severe cold and excessive coughing, had retired to his room. “When some time had elapsed, the door of my room was gently opened, and on drawing my bed-curtains, to my utter astonishment, I beheld Washington himself, standing at my bedside, with a bowl of hot tea in his hand.”

Little acts of kindness, graciousness, and softness such as these show that there was much more in George Washington’s masculinity than hard power and an imposing physique. On this last score, most portraits of him give to his person burliness and size that real Washington did not possess. Certainly not slight, the analysis of his extant apparels, waistcoats, in particular, demonstrates that John Trumbull, in the equestrian portrait of 1790, got Washington better than many other painters.

Cockades, gilded buttons, and the rather narrow cut of the suit made him French and à la mode without turning him into a downright molly. Wary of excesses, Washington nonetheless spent an inordinate amount of time and energy (and certainly money!) to fashion up every aspect of his personal vêtements. In the 50s, as well as in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, the invoices he sent to tailors and purveyors abroad reveal that he cared for fancy, expensive, and tasty items.

The mythic brown inaugural wool broadcloth suit made in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1789, was an episode, as on that particular occasion he wanted to reenact the age of homespun. But in general, he made sure the supply of fashionable items, “directly from France” could flow unhampered: superfine broadcloth, ribbons, silks, cambric, plain lawns, linens, flowered patterns, and printed goods had to reach him no matter what.

Of silk was made the “dress bag” that held the president’s queue on dress occasions. Silk stockings, marble colored silk hoses, silk breeches, and silk handkerchiefs adorned his persona. All in all, Washington’s masculinity was smooth and silky—softer than we may at first think.

Featured Image credit: “Washington at Verplanck’s Point” by John Trumbull, 1790, Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post George Washington and eighteenth century masculinity appeared first on OUPblog.

Will common law dispute resolution bring banks to Paris after Brexit?

The European continent operates a legal system derived from the Napoleonic Code, first enacted in 1804. Napoleon was, I venture to point out, and without meaning to be too critical, a revolutionary dictator. He gathered four eminent jurists together and, as dictators are wont to do, ordered that they produce an all-encompassing system of law for his judges to administer to the nation. Here in England, we had the good fortune to have monarchs who were too busy enjoying the life of a monarch to want to get involved with the minutiae of promulgating comprehensive legal codes. They took an altogether more relaxed approach: they chose the people they trusted, appointed them as judges, and told them to go forth and work out the answers for themselves.

Perhaps by luck rather than good judgment, then, there are significant differences between the work done by judges in these two systems, which, makes the common law attractive to international markets. Both common law judges and their civil code colleagues have the task of administering statutory law that the legislature passes by applying relevant statutes to the facts of each case. This task involves interpreting and occasionally improving the pale letter of the statute so that, through public judgments, the laws passed by Parliament come to be understood in practice and observed by those who are subject to them. That much is plain sailing. Common law judges, however, have an additional function – as a result of their monarch’s initial generous terms of reference – which goes well beyond their European colleagues’ remit of administering an all-encompassing statutory scheme to a grateful nation: to make law through the very cases they decide. This is the common law doctrine of binding precedent – ‘case law’ – in its pure form. The common law courts are therefore a separate source of law in common law jurisdictions, independent of and additional to the legislature.

So what is attractive to international financial markets about the common law courts’ law making powers? There are, no doubt, those within the FSI who will be familiar with the expensive and difficult task of influencing governments to pass legislation – and regulation, its younger sister – which enables the FSI to thrive. There is an electorate on the other side of the process which often attempts to influence governments in different directions; those electorates are very properly vigilant to protect their interests by parliamentary and extra-parliamentary means, as they know there is no one else looking out for them. Ask any former President of France who has tried to tinker with the labour market: legislating is a difficult, expensive, and often unrewarding business. And when the ink finally dries on the vellum, bringing one political event to a close, the nation state has at last settled the terms it will dictate to the market until the next political event, whenever that may be. When viewed in that context, the remote and anonymous corridors of Brussels, which the UK is about to quit, must seem like an Elysium in comparison. No wonder so many people are so furious.

What is attractive to international financial markets about the common law courts’ law making powers?

Judge-made case law, on the other hand, arises independently of the political process. It is law created in response to demand for it in the marketplace. It operates like this. Counterparties in a marketplace enter into an agreement. On occasion they fall into disagreement about the meaning of the agreement they struck. At that moment – i.e. at the point of dispute – demand for law arises. The parties approach the court, the court hears argument, then gives its judgment in public. At that point – the point of resolution of the dispute – the court supplies law in response to market demand. Over time, as similar disputes go through the common law system, principles for deciding those types of cases emerge. The market observes those principles closely and adjusts its behaviour in accordance with the norms established by the court. Parliamentary activity plays no part.

So it is that common law judges provide what we can fairly describe as a constant ‘feedback loop’ for the markets they serve; they can adapt, refine, or create – and occasionally change – the law at any time upon a market participant issuing a claim form before the common law courts. This constant ability for the supply of law to meet demand in the market place for its creation means the common law courts are the friend of market innovation. The common law process of law-creation is independent of the political cycles. The fact that an electorate trusts judges to have a significant role in law-creation tends to make parliamentary politics more stable. In turn, stable politics creates stable markets. Stable markets attract more market activity. When it works, it creates a virtuous circle.

European civil code law gives no scope for judges to create law. Instead the civil code is imposed by the state intermittently on the market when national politics allows. Did I say intermittently? I do not wish to be unfair. On 1 October 2016, the French civil code received its first major revision, 212 years after it was first proclaimed by Napoleon. So the role of common law judges in making law may explain in President Macron’s decision: international markets do not want to be dependent on any national parliament for the development of the law to keep up with the innovation of international markets; like British monarchs before them, they prefer to put that work in the hands of judges they trust.

Featured image credit: “Paris, France, Eiffel Tower, City” by Free-Photos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Will common law dispute resolution bring banks to Paris after Brexit? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 18, 2018

Taking stock of the Catalan independence bid

With the high drama of October now in the rear view mirror, the push for Catalonia’s independence has largely receded from international headlines. Yet, it leaves in its wake a number of open questions. In this brief piece, I consider three that are particularly illuminating of broader patterns of politics in multinational states.

Why no compromise?

Outside observers found the inability of Catalan and Spanish governments to reach a compromise before October’s showdown concerning and puzzling in equal measure. The incomprehension was understandable: economically advanced liberal democracies do not normally produce this level of open political conflict. Surely, breaching the constitutional framework (as the Catalan government did), and responding to such a breach with force and unprecedented institutional intervention (as the Spanish executive did) would prove too costly to contemplate. Yet this is precisely what took place. Why?

The answer has to do with the stories used to mobilize around specific political projects, and the party-political dynamics with which these stories intersect. Proponents of Catalan independence built their support by arguing that a federal compromise, the default institutional preference of many Catalan nationalists prior to 2012, was simply no longer viable. In making their case, they offered a number of ‘proofs’, including the 2010 decision of the Spanish Constitutional Court, widely perceived in Catalonia as having reduced the scope of Catalan autonomy.

This discourse was mainstreamed amid heated competition between two major nationalist parties, the Republican Left (ERC) and Democratic Convergence (today Catalan Democratic Party (PDeCat). Once a sufficiently large segment of the Catalan public internalized the ‘end-of-compromise’ narrative, the outbidding dynamic propelled the two parties toward increasingly radical options.

On the other hand, Spain’s governing Popular Party (PP) has traditionally viewed itself as the ‘protector of the Spanish state.’ A significant proportion of its constituency is hostile to multinational federalism, to say nothing of secession. It is therefore not surprising that the party spent the past five years steadfastly refusing successive Catalan governments’ demands for a referendum on the region’s status.

PP’s resolve was further stiffened by the prospect of losing ground to Citizens, a party even more unrelenting on national unity than PP itself. Recently, these fears have started to come true, first in PP’s electoral wipe-out in Catalan elections last December, and subsequently in the Citizens’ surge in Spain-wide opinion polls. This combination of mutually exclusive narratives and party politics made compromise between Spain and Catalan exceedingly difficult.

2012 Catalan independence protest on September 11th by Kippelboy. CC-BY-SA-.30 via Wikimedia Commons.

2012 Catalan independence protest on September 11th by Kippelboy. CC-BY-SA-.30 via Wikimedia Commons.The dog that did not bite

The ensuing confrontation between Spanish and Catalan governments created a political climate in which it was reasonable to expect a spike in support for independence and even greater instability. Recent scholarship suggests that loss of autonomy tends to energize secessionist movements instead of weakening them. If there ever was an unambiguous reduction in the scope of Catalan self-government over the past four decades, it came with the application of Article 155 of the Spanish constitution. The suspension of Catalan autonomy was preceded and followed by several other actions that were framed as assaults on self-government, including the dismissal and arrest of members of the government and parliament last October and November.

Yet despite this, Catalan secessionist backlash failed to materialize. Support for independence did grow, but only to a previous high of just under 50%. This result was affirmed in the recent regional elections, where pro-independence parties obtained much the same level of support as two years prior (47.6%, with a thin majority of seats). What accounts for this seemingly counter-intuitive outcome?

The most obvious answer is the fear of rising economic uncertainty. Over three thousand companies moved their headquarters from Catalonia to other parts of Spain since 2 October 2017. The story gets more complicated when we consider that national identity and traditional party affiliations predispose people to discount economic costs of risky decisions. This could explain why so many Catalans voted for secessionist parties on 21 December, apparently undeterred by the potential economic perils of their choice.

However, I believe we need to dig deeper. Rather than confining our inquiry to the impact of ‘objective realities’ of politics, such as the change in the levels of territorial autonomy, we ought to pay far more attention to how these ‘realities’ are interpreted and packaged in political discourse. A constructivist approach to nationalist mobilization might reveal that raw data on, say, institutional change may mean something completely different under dissimilar circumstances.

Groundhog Day scenario, with a twist

The last open question is what happens next? As noted, the recent regional election produced roughly the same balance of pro- and anti-independence forces that existed before the application of Article 155. Catalan independentists control a slim majority of the seats and may return to government (provided they are able to select an eligible candidate for the region’s presidency). If all one did was read the numbers, it might appear that everything was set for a replay of the past round of clashes. This would then probably result in the same response from the Spanish institutions – in other words, a Groundhog Day scenario.

Yet, despite superficial similarities, it is clear that Catalonia’s political landscape has been transformed. Criminal charges against – and the arrests of – regional officials and civil society figures, the now much more tangible economic cost of secession, and the suspension of Catalan autonomy, present the pro-independence parties with a new reality. Unilateral action on independence is off the menu. At the same time, the activism of the past decade, combined with recent events, has transformed the identities and raised the expectations of many Catalans. This makes it difficult for the nationalist parties to reverse course and renounce independence altogether.

Instead, their strategy will entail treading water – they will likely continue advocating independent statehood while extending the time horizon within which that statehood is to be attained. Indeed, both ERC and PDeCat have been revising their strategies and cautioning that the road to independence will be long. What this will mean in practice is difficult to predict, but it may be that the worst confrontations are now in the past.

Featured image credit: Long expo Barcelona photo by Javier Bosch. Public domain via Unsplash .

The post Taking stock of the Catalan independence bid appeared first on OUPblog.

10 tips for getting your journal article published

Writing a paper that gets accepted for publication in a high-quality journal is not easy. If it was, we’d all be doing it! Academic journals publish articles that are well-written, and based on solid scholarship with a robust methodology. They must present well-supported stories and make significant contributions to the knowledge base of the journal’s specific discipline. Often, manuscripts are rejected before even going out to review because they are poorly written or fail to meet a journal’s publication requirements. Publication requirements don’t just mean submission guidelines, which, of course, need to be followed, but also the more fundamental aspects of composing a publishable article.

Here are 10 recommendations on how to effectively write papers that will be considered for publication in high-quality journals:

1. Who is your audience? This is the first question you should ask yourself. Is it the experts in your specific field or scientists in other disciplines? Is it the reading public, or policy makers? Each of these audiences will bring different background assumptions or knowledge to your piece, so how you write for each of them will differ. Ask yourself the questions your audience may ask: Why am I reading this? Why should I keep reading this, rather than reading something else, or doing something else entirely?

2. Respect your audience. Do not make them have to work to figure out what you’re trying to say or what the structure of your story is. The people you are submitting your manuscript to are busy people, especially journal reviewers and editors. If your article is hard to read and follow, it makes their job harder than it should be – increasing the likelihood that your work will be rated poorly or rejected if being considered for publication.

3. Outline your ideas. Use this step to get down the order of your ideas, identifying the main and supporting points of your article. Outlining does not have to be in an orderly, linear fashion, if that does not work for you. Using post-it notes, the mind-map technique, or writing on a blackboard are all techniques you can use to ensure your ideas form a coherent structure.

4. Start with your idea, then expand upon and support it. Academic writing should not be like a mystery novel that reveals the outcome only at the end. Effective scientific narratives start from a stated focus, move through a clear structure of support, and bring the story to fruition. The organization and order of ideas should be clear throughout. If you find yourself circling back or repeating details, that likely means the structure of your work needs to be revised.

5. Keep it simple. Just because the topic is complex does not mean the writing should be. Simple, straightforward sentences are better than long, convoluted ones. Exact, plain words are better than vague ones. Do not use jargon or acronyms – especially when submitting to multi-disciplinary international journals. Make sure every word plays a role in presenting your case and that you know the meaning of any unusual words you use. If you are looking to publish in a language that requires heavy translation on your part, seek help from your advisor, colleagues, university writing centres and professional writing services to improve your article.

6. Practice makes perfect. It might seem like a clichéd answer, but it really is the key. Write regularly; practice it as a discipline in and of itself. Writing a high-quality, publishable article requires confidence in your ideas, and practice and skill which takes time to acquire. You can learn to write well, but you need to increase the amount of time spent writing, too. This doesn’t have to be at your desk or in front of a computer, though. Make good use of time spent walking, waiting for the bus, or commuting on the train to think of how you can improve what you are currently writing.

7. Pay attention to good and bad writing. Which academic writers produce work that engages you? Which ones do not? What is the difference in how they present their arguments? What is the difference in how they use words and lay out sentences? Thinking carefully about other people’s writing is a step toward improving your own.

8. Write now, edit later. Some people are able to compose and edit at the same time, but if this is not the case for you, keep the two functions separate. The first draft of your research might be horrible, and nothing you would show anyone else. It doesn’t matter. Get something down. Work on it every day to get more down until you have your story or argument complete. Wait until later to edit it.

9. Give your manuscript ‘drawer time’. This is the time your manuscript spends in the dark of your file cabinet or unopened on your hard drive. This is one of the most valuable tools you can use when writing, because it allows you to become a better editor of your own work. Letting your manuscript sit for a while means that when you come to read it again, you should be able to identify any problems with it.

10. Stick at it. It is undoubtedly true that it is more important than ever for students and early career professionals to develop good writing skills and a thorough knowledge of the journals publication process. However, developing those skills and putting them into practice takes time, so don’t get discouraged. We all had to start somewhere!

Featured image credit: home-office by Free-Photos. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 tips for getting your journal article published appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten things you may not know about women and liberty

Imagine that you’re a married woman living in a bleak dystopian world in which you’re barred from higher education, you’re forbidden from owning your own property, you have no freedom of movement outside your own home, and your husband might sexually assault you at any time, with impunity.

Only three or four hundred years ago, this was not some fantastic fictional scenario from The Handmaid’s Tale. This was the historical reality for married women in western Europe (sadly, it’s still the reality of some women in some countries today).

But while the early modern era was a period of domination, oppression, and subjugation, it was also a period of resistance, criticism, and feminist protest. Our sisters of the past were much like the sisters of today: they could spot injustices, they got angry about them, and they wrote about how things could change.

Here are ten things that you might not have known about women’s thoughts on liberty during this historical period (1600-1800).

Women used republican ideas to criticize marriage. Defenders of republican liberty claim that a person is free provided that no-one else has the power to dispose of that person’s property (her “life, liberty, and estate”) at his arbitrary will and pleasure. Eighteenth-century women writers, such as Sarah Chapone and Mary Wollstonecraft, highlighted married women’s lack of liberty in this republican sense. Chapone pointed to the fact that every husband in her period had the power to horse-whip his wife, to keep her confined to the basement in near-starvation conditions, and then gamble away her money and estate—all with legal impunity. Funnily enough, she thought the law should be changed.

Women argued that marriage was slavery. Some women writers of this period argued that a married woman was enslaved by her husband, even if her husband were kind and benevolent and generally a jolly nice fellow. Their arguments were built on the republican insight that an agent isn’t strictly free in those situations in which someone else has the power to interfere in their lives, even if that person never exercises his power. To the male republicans of her time, Mary Astell famously posed the question: “If all Men are born Free, how is that all Women are born slaves?” It was her nice way of suggesting they were abominable hypocrites.

A woman anticipated the positive/negative liberty divide. In the 1950s, Isaiah Berlin made a famous and influential distinction between freedom from external interference or constraint (negative liberty), and freedom to achieve something or become someone (positive liberty). In the late eighteenth century, a woman named Sophie De Grouchy prefigured this famous modern-day dichotomy in her own distinction between positive property rights and negative rights. De Grouchy wrote her Letters on Sympathy at least twenty years before Benjamin Constant’s essay on ancient and modern liberty, a key inspiration for Berlin.

Women found inspiration in metaphysical ideas about freedom. Women thinkers of the period embraced popular Cartesian ideas about freedom to argue in favor of women’s intellectual competence. Gabrielle Suchon and Mary Astell both echo the French philosopher René Descartes’ insights about the radical freedom of the will. In a nutshell, they argue: “I think, therefore … I have the power to affirm or deny, pursue or avoid the ideas of my intellect, so that I can follow the right way of thinking in any circumstances.” OK, so it wasn’t as pithy as “I think, therefore I am,” but it was inspirational for other women.

Writers called for higher education opportunities for women. Drawing on the aforementioned insights about women’s freedom of mind, several thinkers—including François Poulain de la Barre, Margaret Cavendish, Mary Astell, and Catharine Macaulay—argued that women were capable of being educated for higher pursuits.

Visionary men travelled the road to feminist emancipation with women. Speaking of Poulain de la Barre—hats off to male feminists, past, present, and future.

Women contributed to the invention of autonomy. Gabrielle Suchon argued that women should lead the life of a “neutralist” who is radically free from external commitments and thus at liberty to follow her inner rational law of nature rather than the dictates of outside social institutions. That is, she contributed to the invention of autonomy a century before a man named Immanuel Kant arrived on the scene.

Historical women anticipated many present-day feminist ideas. Astell, Eugenia, and Mary Chudleigh all recognized that marriage promotes the “merger of egos,” a kind of slavish subservience that leads to women’s interests being sacrificed for the sake of men’s concerns—something that modern-day feminists, like Sandra Bartky and Marilyn Friedman, still subject to critique. The idea of autonomy being exercised against a consideration of our relations with others—current-day relational autonomy—was already driving Astell’s idea of the importance of female friendships in a religious retreat of higher learning and Cavendish’s idea of female-only communities.

Some women were committed to building large-scale philosophies in which metaphysics, physics, morals—and freedom’s place therein—are integrated into a single, systematic vision. Anne Conway’s interests lie in thinking about women’s and men’s freedoms against a consideration of their relations with God. Catharine Cockburn’s philosophical projects include a fascination with the theological, including thinking about the nature of God’s freedom. And Emilie Du Châtelet was keen on thinking about women’s lives and freedoms within a systematic account of the nature world.

Women philosophers used a wide range of genres and methods to write philosophically about women and liberty in order to reach a variety of audiences against a backdrop of skepticism regarding women’s philosophical abilities. Astell’s use of irony allowed her to sneak dangerous ideas into the conversation about marriage. Cavendish’s plays play with subversive ideas of women divorced from the company of men. And Wollstonecraft’s novels vividly capture the emotional cost to women deprived of human liberty.

It might also be added that these women thinkers themselves found liberty in exercising their intellects—in exercising their freedom to philosophize.

Featured image credit: A Lady Writing by Johannes Vermeer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten things you may not know about women and liberty appeared first on OUPblog.

February 17, 2018

The economic relationship between Mexico and the United States

Mexico and the United States share a highly integrated economic relationship. There seems to be an assumption among many Americans, including officials in the current administration, that the relationship is somehow one-sided, that is, that Mexico is the sole beneficiary of commerce between the two countries. Yet, economic benefits to both countries are extensive.

Mexico has played a significant role in the rapid expansion of US exports in the 1990s and 2000s. It alternated between the second and third most important trade partner of the United States in the last decade. In 2014, the United States exported a total of $240 billion worth of goods to Mexico, with the largest products coming from the computers and electronics, transportation, petroleum, and machinery sectors. By contrast, China only purchased $124 billion of US exports. Exports to Mexico accounted for approximately 1,344,000 jobs in the United States.

California alone, boasting the eighth largest economy in the world, exported more than 15% of its products to Mexico by 2014, exceeding what it trades with Canada, Japan, or China. As of 2014, Mexico’s purchases of California exports supported nearly 200,000 jobs in the state. In fact, 17% of all export-supported jobs in California, which account for a fifth of all individuals employed in the state, are linked to the state’s economic relationship with Mexico. More than half of those export-related positions can be traced to the North American Free Trade Agreement. California and Texas – the two largest economies in the United States, and two of the three largest state/provincial economies in the world – are significantly influenced economically by Mexico.

In 2014, a heavy portion of exports from six US states were purchased by Mexico: 41% in Arizona, 41% in New Mexico, 36% in Texas, 25% in New Hampshire, 23% in South Dakota, and 23% in Nebraska. As Senator John McCain noted several weeks ago, the Trump administration’s decision to renegotiate, rather than withdraw from NAFTA, prevented a horrific economic impact on Arizona. The GDP of the United States and Mexican border states accounts for a fourth of the national economy of both countries combined, exceeding the GDP of all the countries in the world except for the United States, Japan, China, and Germany.

The United States provides the single largest amount of direct foreign investment in Mexico, but what I want to stress, and to educate Americans about, is that Mexican entrepreneurs and venture capitalists invest heavily in the United Sates. By 2013, Mexico had invested $33 billion, the only emerging economy among the top fifteen countries with direct foreign investments in the United States. In 2015, Pemex, the government oil company, opened the first retail gasoline station in the United States, in Houston, and plans on opening four more in that city. This is a pilot project to test the American market nationally. OXXO, another Mexican firm, has opened two convenience stores in Texas, and plans on investing $850 million to open 900 stores in the United States.

Finally, Mexico also influences the US economy through tourism in the same way that American tourists play a central role in Mexico’s economy. In 2014, 75 million foreigners visited the United States, generating $221 billion dollars. Canada accounts for the largest number of visitors each year, followed by Mexico, which provided 17 million tourists in 2014, who spent $19 billion. Along the border, at the end of the decade, Mexican visitors generated somewhere around $8 billion to $9 billion dollars in sales and supported approximately 150,000 jobs.

Another way to look at the relationship between Mexico and the United States is through cultural influences. Mexico exerts impact through music, food, film, and language. For example, there are multiple fast-food chains that specialize in Mexican food. Grocery stores stock more items originating from Mexico than any other ethnic cuisine in the world, including beers, beans, hot sauces, peppers, and tortillas. Corona is the best-selling foreign beer in the United States. Mexican foods such as guacamole and caesar salad are so commonplace that they have lost their identity as Mexican cuisine.

Food drink wood mexico by Rafa_Chakas. CC0 via Pixabay.

Food drink wood mexico by Rafa_Chakas. CC0 via Pixabay.The use of Spanish words and Mexican slang is evident in everyday language in the United States; such terms range from “mano a mano” to “macho,” “enchilada” to “margarita,” and “rancho” to “hacienda.” According to a Pew Center study in 2011, 38 million individuals in the United States five years or older showed that the majority of them were Mexican, and were speaking Spanish at home. Spanish is also the most widely spoken non-English language among Americans who are not from a Hispanic country. The size of the Spanish-speaking audience in the United States has also influenced the growth of Mexican films. The musical influence has kept pace with cuisine. In 2010, the New Yorker magazine ran an extensive article about Los Tigres del Norte, a musical group from San Jose, California, who represent the norteño musical style. They boast a huge following among music fans. Selena, who died two decades ago, has sold more than 60 million albums, including songs representing the mariachi and ranchera genres, and the number of copies of her posthumous best-selling album of all time, Dreaming of You, reached five million by 2015. Among young adults (18 to 34 years of age) who listen to the radio, Mexican regional music ranks seventh in popularity.

The relationship between the United States and Mexico has become more complex over time, incorporating cultural, musical, economic, familial, political, and security relationships beneficial to both countries and its citizens. But the most dramatic change in those many facets of our relationship with each other is the degree to which Mexico’s impact on and within the United States has grown in importance. Equally important to consider is that in spite of President Trump’s public criticisms of Mexico, our relationship at numerous levels, public and private, remains strong.

Featured image credit: “Plugs, Mexican, Food” by samuelfernandezrivera. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay .

The post The economic relationship between Mexico and the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers