Oxford University Press's Blog, page 276

February 24, 2018

Alain Locke, Charles S. Johnson, and the establishment of Black literature [excerpt]

In March of 1924, Charles S. Johnson, sociologist and editor of Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, approached Alain Locke with a proposal: a dinner was being organized with the intention to secure interracial support for Black literature. Locke would attend the dinner as “master of ceremonies” with the responsibility of creating the bridge between Black writers and potential White allies. Both Johnson and Locke recognized that a literary movement centered on the Black experience in America would need White support in order to gain momentum. The following excerpt from The New Negro details how Locke secured a space for Young Black writers within the larger literary community.

As March 21 approached, participants became nervous. A week before the dinner, Bennett wrote Locke, “I am so glad that you have agreed to come. I feel the utter necessity of your being there.” Bennett was even more grateful he would be out front when the day of the event arrived. “You are particularly appreciated,” she wrote to Locke, “because of the tremendous and unswerving confidence that you have in us. Your faith in our utter necessity is particularly helpful as I find that my mind is not clear on the eve of this momentous event.” Even Johnson seemed nervous. After confiding in Locke that “the thing has gone over big, nothing can be allowed to go wrong now,” Johnson asked him to come up early that day to help him finalize the evening’s program. “I would like to see you as early as possible to have the first talk about plans, and probably, we shall have to do most of the arranging of the program then.” After a short introduction by Johnson, Locke would discuss the significance of these new writers, and then introduce Carl Van Doren who would outline his hopes for the Negro writer. Then, Horace Liveright, the publisher of Cane and There Is Confusion, would make a few remarks about the publishing scene for Negro books, a market-reassuring strategy most likely recommended by Johnson. After, Gwendolyn Bennett, Countee Cullen, and a few others would read poems and give testimonials. Jessie Fauset would give the closing remarks.

Work on the program concluded, two of the smallest African Americans—Johnson was only 5´2˝—proceeded to the Civic Club dinner, dressed to the nines that Friday evening. Locke began his remarks by arguing that a new sense of hope and promise energized the young writers assembled, because they “sense within their group—meaning the Negro group—a spiritual wealth which if they properly expound will be ample for a new judgment and re-appraisal of the race.” Although Locke’s optimism has led critics to claim that he promised Black literature would solve the race problem, his language was actually quite cautious. Negro literature would “be ample,” that is, sufficient, to contradict those Whites who claimed Blacks were intellectually inferior “if they [i.e., the Black writers] properly expound [it].” Their success would allow “for a new judgment . . . of the race” if Whites were willing to render it. But there are no guarantees.

“Carl Van Doren then laid out what the White literary press wanted from the younger Negroes: art not anger.”

More powerfully expressed was Locke’s belief that by avoiding a literature of racial harangue, the new group of writers could make a broader contribution than those who had come before them. Locke advanced a new concept, that of generation, to suggest this was a new cohort of Black writers possessed of a devotion to literary values that set them apart from their forerunners. For example, Locke introduced Du Bois “with soft seriousness as a representative of the ‘older school’ ” of writing. That seemed to put Du Bois slightly on the defensive and felt called upon to justify writers of the past as “of necessity pioneers and much of their style was forced upon them by the barriers against publication of literature about Negroes of any sort.” Locke introduced James Weldon Johnson—a writer of poetry, music lyrics, and a novel—“as an anthologist of Negro verse”—another dig, since Johnson was a novelist, a lyricist, and a poet, in addition to editing The Book of American Negro Poetry and writing a powerful introductory essay. Locke did acknowledge him for having “given invaluable encouragement to the work of this younger group.” By defining these NAACP literary scions as elderly fathers and uncles, Locke implied their virtual sons and daughters were Oedipal rebels whose writings rejected the stodginess of their literary parents. Against the backdrop of an ornate Civic Club dinner, with its fine china, polished silverware, and formally attired White patrons, Locke issued a generational declaration of independence for the emerging literary lions of the race.

Carl Van Doren then laid out what the White literary press wanted from the younger Negroes: art not anger. Gingerly but tellingly, Van Doren ventured that the literary temperament of the African American, whether produced by African or American conditions, was distinguished by its emotional transcendence, its reputed ability to avoid haranguing White America for its obvious wrongs and turning suffering into works of unparalleled beauty. Young Black writers had to sit and listen to Van Doren declare that “long oppressed and handicapped, [Negro artists] have gathered stores of emotion and are ready to burst forth with a new eloquence once they discover adequate mediums. Being, however, as a race not given to self-destroying bitterness, they will, I think, strike a happy balance between rage and complacency—that balance in which passion and humor are somehow united in the best of all possible amalgams for the creative artist.” A certain amount of condescension was the cost of liberal White support.

Featured image credit: “Books Notepad Pen Education Notebook Student” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Alain Locke, Charles S. Johnson, and the establishment of Black literature [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

The counter-revolution in Europe

Several months after the fall of the Berlin Wall Ralf Dahrendorf wrote a book fashioned on Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France called Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. Like Burke, he chose to put his analysis in the form of a letter to a gentleman in Warsaw. The intention was to explain the extraordinary events taking place in Europe around 1989, reflecting on this turbulent period from his study at St Antony’s College in Oxford. Dahrendorf did not share Burke’s liberal conservatism and his book does not read like Burke’s political pamphlet. He saw a liberal revolution evolving in Eastern Europe and he tried to identify opportunities that this revolution created, as well as possible traps lying in its path.

Today we are witnessing an equally turbulent period in Europe, however heading in the opposite direction. Under assault are key pillars of the liberal revolution analysed by Dahrendorf: parliamentary democracy and free trade, migration and a multicultural society, historical ‘truths’ and political correctness, moderate political parties and mainstream media, cultural tolerance and religious neutrality; multilateral diplomacy and European integration. In essence: we are witnessing a counter-revolution.

I decided to reflect on this European predicament in a way (and location) Dahrendorf had done it three decades ago. Can open society survive? Is Europe disintegrating? How to overcome the economic crisis? Will Europeans feel secure again?

Why is this a counter-revolution? There are neither barricades raised on European streets nor sit-in strikes in factories. There is no singleideology inspiring and uniting protest movements. There is much talk about anti-politics, but those who lead the protest create parties and try to win elections. Yet, it would be a mistake to assume that revolution or counter-revolution must always involve mass mobilizations and violence culminating on a certain date. Communism collapsed with little if any violence. Poland’s Solidarity movement was able to organize mass strikes in 1980, not a decade later. Change came chiefly through pacts between old and new elites and through elections. And yet it is hard to deny that this relatively peaceful process changed Europe beyond recognition. History did not end, but the old order has gradually been replaced by a new one. Although some of the former communists were able to stay in power, they were able to do so only after endorsing the new liberal order. This is why Dahrendorf rightly called it a revolution despite all qualifications. And since he wrote his book in 1990 the revolution has greatly progressed.

Professor R. G Dahrendorf, 1980 by Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science. No known copyright restrictions via Wikimedia Commons.

Professor R. G Dahrendorf, 1980 by Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science. No known copyright restrictions via Wikimedia Commons.The Soviet Union and Yugoslavia disintegrated, Germany has been reunited, and the European Union as well as NATO have been vastly expanded. Western armies, laws, firms, and customs moved eastward. Many people enthusiastically welcomed new regimes on their territory, but some felt disadvantaged either because of their ethnic background (e.g. Russians in Latvia, Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina) or because they lacked adequate professional skills to function in the new competitive environment. A long-standing balance of power in Europe had been effectively reshuffled. Russia soon began to see herself as an underdog, but also France found herself in a weaker position vis-à-vis Germany than before.

Geopolitical revolution has been followed by economic revolution. With the fall of communism some of its more universal ideals came under fire: collectivism, redistribution, social protection, and state intervention in the economy. This paved the way for neo-liberal economics to assume a dominant position throughout the entire continent, not just in Great Britain. Deregulation, marketization, and privatization became the order of the day even in states run by socialist parties. The private sector has subsequently expanded at the expense of the public sector. Markets and market-values moved into spheres that used to be the domain of the public sector in Europe such as health, education, public safety, environmental protection, and even national security. Social spending has been contained if not slashed altogether for certain disadvantaged groups. Even in countries like France or Spain, once home to powerful unions, less than 10% of the workforce is unionized now. Membership of Poland’s Solidarity trade union has fallen five-fold since 1989. Today less than 5% of Poland’s workforce is unionized.

Across Europe, politics was increasingly being presented as an art of institutional engineering, not as an art of political bargaining between the elites and the electorate. More powers were delegated to non-majoritarian institutions – central banks, constitutional courts, regulatory agencies – to make sure that “reason” rather than “passion” guided political decisions. Politics seen as giving in to public pressure was considered irresponsible if not dangerous. Majorities were said to spend money they didn’t have, to discriminate against all kind of minorities, to support such ethically knotty causes as the death penalty or torture. Citizens were to be educated rather than listened to. The notion that public interests need to reflect public wishes has been questioned. Interests were said to be best identified by experts: generals, bankers, traders, lawyers, and of course, leaders of the ruling parties.

The EU with its enlarged powers following the 1991 Maastricht Treaty has been a prototype of a non-majoritarian institution led by “enlightened” experts largely independent from electoral pressures. True, the European Council consisted of democratically elected politicians, but the introduction of majority voting has made it difficult for member states to veto some decisions. In fact, national executives proved eager to bypass their respective parliaments by making decisions in the European Council.

Today this liberal legacy is under fire, not only in the post-communist democracies of Eastern Europe and indebted democracies of Southern Europe, but also in the most affluent European countries such as Austria, Finland, Germany, and Holland. This is because liberals compromised, if not perverted, many of their ideals. They refuse to look in the mirror and recognize their own shortcomings, which led to the populist surge across the continent. Populists have neither charismatic leaders nor credible programs; they are strong because liberals have been doing poorly for several years.

My response to Dahrendorf is that Europe and its liberal project need to be reinvented and recreated. There is no simple way back. Europe failed to adjust to enormous geopolitical, economic, and technological changes that swept the continent over the past three decades. European models of democracy, capitalism, and integration are not in sync with new complex networks of cities, bankers, terrorists, or migrants. Liberal values that made Europe thrive for many decades have been betrayed. The escalation of emotions, myths, and lies left little space for reason, deliberation, and conciliation. Another “valley of tears” is therefore ahead for Europeans. But there is a way out of the current European quandary.

Featured image credit: blue and yellow round star by freestocks.org. Public domain via Pexels .

The post The counter-revolution in Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Making babies: 21st century reproduction

Half a century ago, technological advancements challenged our understanding of life’s end. At what point does death occur for human beings? Prior to the 1960s, the answer was simple. The biological concept of death was defined as that which happens after one’s heart stops beating. But when technological advancements allowed the heart to beat even after the brain had died, it was no longer clear whether death occurred when the heart stopped beating or when the brain stopped functioning.

Today, it is our understanding of the start of life, not its end, that’s being challenged. What does it take to reproduce? Once again, technological advancements are challenging one of our most familiar biological concepts. It used to be that there were only two ways for something to reproduce: either through the sort of sexual reproduction typical of most animals or through the asexual reproduction characteristic of things like bacteria. Advancements in biological technology, however, are forcing us to rethink what it means to reproduce.

Consider, for example, “third-party reproduction,” which is a technique for assisting individuals who are having difficulty conceiving. Using genetic material from someone other than the hopeful parents, scientists can help correct biological problems that previously prevented a couple from having children. For example, when an intending mother is known to have disease-linked mitochondrial DNA, a donor can contribute her healthy DNA to replace the unhealthy portion of the DNA of the intending mother. The result is a child with three genetic contributors: one male and two females. Rather curiously, however, the mitochondrial donor is required to acknowledge, by consent, that she won’t be the child’s genetic parent. Apparently, she hasn’t reproduced even though the other two genetic contributors have. In fact, the UK-based Nuffield Council on Bioethics concluded, “[this type of] donation does not indicate, either biologically or legally, any notion of the child having either a ‘third parent’, or ‘second mother’.” But this conclusion seems odd: if a child belongs to his or her parents in virtue of inheriting their genetic material, why isn’t the mitochondrial DNA donor one of the child’s genetic parents?

Today, it is our understanding of the start of life, not its end, that’s being challenged.

One reason offered by the Nuffield Council is that mitochondrial DNA comprises only a small fraction of overall DNA. But it’s hard to know what to make of that reason. As it happens, the fraction of DNA transferred between generations can vary significantly and, according to law, apparently not undermine parent/offspring relations. Compare, for example, the amount of DNA passed from parent to offspring in two standard forms of reproduction: sexual and asexual. In asexual reproduction, the offspring inherits 100% of the DNA of its parent, but in sexual reproduction, that amount drops by half. The offspring of sexually- reproducing parents inherits only half of a parent’s DNA, yet the process is still considered an instance of reproduction. Now, if the amount of DNA passed from parent to offspring can vary this dramatically and still count as reproduction, what prevents even smaller amounts of DNA transmission from being considered reproduction? What amount of DNA is sufficient for the contributor to have reproduced? What if we develop a method of replacing stretches of DNA constituting 40% of overall DNA, or 30%, or 10%? How much is enough for the reproductive process to involve three parents, rather than two? If there is no principled way of drawing a boundary between instances of DNA transmission that are large enough to fall within the boundaries of “reproduction” and ones that aren’t, then we need some other justification for denying that mitochondrial DNA transfers fall under the scope of the concept.

Third-party reproduction is just one of numerous methods available to “assist” reproduction. It’s one of many technological innovations that are forcing us to rethink outdated biological concepts. In the same way that the invention of the ventilator forced us to reimagine our concept of death, so too, inventing new ways of merging biological parts is forcing us to rethink what it means to reproduce.

Featured image credit: IVF by DrKontogianniIVF. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.

The post Making babies: 21st century reproduction appeared first on OUPblog.

February 23, 2018

In memoriam: Jimmie C. Holland, MD

Jimmie C. Holland, MD, internationally recognized as the founder of the field of Psycho-oncology, died suddenly on 24 December 2017 at the age of 89. Dr. Holland, who was affectionately known by her first name, “Jimmie,” had a profound global influence on the fields of Psycho-oncology, Psychosomatic Medicine, and Oncology.

Dr. Holland was the Attending Psychiatrist and Wayne E. Chapman Chair at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and Professor of Psychiatry, Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York. In 1977, she was appointed Chief of the Psychiatry Service in the Department of Neurology at MSK. The Psychiatry Service at MSK was the first such clinical, research, and training service established in any cancer center in the world. In 1996, Dr. Holland was named the inaugural Chairwoman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at MSK Cancer Center, also the first such department created in any cancer center in the world. Over 25 years ago, Dr. Holland founded and co-edited the international Psycho-Oncology journal.

Dr. Jimmie Holland. Image courtesy of Dr. William Breitbart. Not to be reused without permission.

Dr. Jimmie Holland. Image courtesy of Dr. William Breitbart. Not to be reused without permission.Dr. Holland edited the first major textbooks of Psycho-oncology, and in 1989 edited the Handbook of Psychooncology: Psychological care of the patient with cancer. This landmark textbook was notable for several reasons; it established a “new” field, a subspecialty of both Psychosomatics and oncology. I remember being a young faculty member in Dr. Holland’s service and the very real sense that we were creating something that had not existed before. I remember her asking me to write multiple chapters, including several in which I had very little expertise. I expressed my concern, “I’m not an expert on the psychiatric complications of head and neck cancer!” She calmly reassured me, “Well, Bill, no one is. So when you finish researching and writing the chapter I suppose then you’ll be the world’s expert!”

Psycho-oncology was born and named with the publication of this textbook and with Dr. Holland’s founding of the International Psycho-oncology Society (IPOS) in 1984, then the American Psychosocial Oncology Society in 1986. Subsequently, Dr. Holland edited, with a group of co-editors, what became known as the “Bible” of Psycho-oncology; Psycho-oncology was published in 1998, and represented the most comprehensive, multidisciplinary, and international encyclopedia of a field entering its adolescence. 2010 saw the publication of the second edition followed by the third edition in 2015. Every card-carrying “psycho-oncologist” (in 57 countries with national psycho-oncology societies) had to have the latest edition in their library to demonstrate their link to Jimmie Holland. Dr. Holland also co-wrote two well received books for the public: The Human Side of Cancer and Lighter as We Go: Virtues, Character Strengths, and Aging, the latter reflecting her interests in Geriatric Oncology as she approached her 90th birthday.

Dr. Holland was born in the small farming community of Nevada, Texas in 1928. She credits the local family physician in that community for her interest in medicine and caring for those who were suffering. She was one of only three women in her class at Baylor College of Medicine. In 1956, Dr. Holland married the renowned oncology pioneer James Holland, MD, who was then Chief of Medical Oncology at Roswell Park in Buffalo, NY. She would chide James, complaining that cancer patients were asked every conceivable question about their physical functioning but never, “How do you feel emotionally?” Dr. Holland pioneered the inclusion of psychological and emotional well-being patient-reported outcomes in quality of life measures and as a component of clinical outcomes in clinical trials.

Dr. Jimmie C. Holland. Image courtesy of Dr. William Breitbart. Not to be reused without permission.

Dr. Jimmie C. Holland. Image courtesy of Dr. William Breitbart. Not to be reused without permission.Dr. Holland has received too many awards to list, however some notable ones include: The Medal of Honor for Clinical Research from the American Cancer Society, The Marie Curie Award from the Government of France, and the Margaret L. Kripke Legend Award for contributions to the advancement of women in cancer medicine and cancer science from the MD Anderson Cancer Center. She served as President of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine (APM) in 1996 and was the recipient of the APM’s Hackett Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994. She was also the inaugural recipient of the Arthur Sutherland Award for Lifetime Achievement from IPOS.

Over a 40-year career at MSK Cancer Center, Dr. Holland created and nurtured the field of Psycho-oncology, established its clinical practice, advanced its clinical research agenda, and through her pioneering efforts, launched the careers of the leaders of a national and worldwide field who mourn her passing and continue to work in what has become a shared mission to emphasize the care in cancer care.

After stepping down as Chairman of the MSK Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in 2003, she kept working full time, seeing patients, conducting research, training and supervising fellows, and traveling the world lecturing and teaching. She also helped bring Psycho-oncology to Africa through her work with the African Organization for Cancer Research & Training in Cancer (AORTIC).

Born in a humble farming community with a one room school house, Dr. Holland created a life that led her to New York and the capitals of the world, honored by so many organizations and societies. She was teaching and seeing patients up until two days before her death. I think we’ll all remember her for various reasons. I certainly have many memories from a 34 year career working beside her. But on that list was her generosity and loving attitude towards her family, her patients, her colleagues, trainees, and everyone who crossed her path. Those who worked alongside her in medicine have made her mission our mission. We will continue this mission’s work, always remembering and honoring Dr. Jimmie Holland. Her death is a profound loss for all of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Medicine, Psycho-oncology, and Oncology. We’ve lost a pioneer, a remarkable woman, a once-in-a-generation influencer.

Featured image credit: Sunflower by Conner Baker. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post In memoriam: Jimmie C. Holland, MD appeared first on OUPblog.

Facts about Shakespeare’s sonnets and poems

Shakespeare’s sonnets and poems may often feel less familiar than his plays, but they have also seeped into our cultural history. Within them, they reveal much about the Bard himself and include a number of surprises. Here are a few lesser known facts about Shakespeare’s sonnets and poems:

1. Frequency of publication: Of all Shakespeare’s great plays–Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, and Othello–the most frequently published work in his lifetime and for approximately a half century after his death in 1616 was not a drama but his erotic poem, Venus and Adonis. First published in 1593, this fast-paced narrative, based on an incident from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, went through no fewer than ten editions by 1617 and another six by 1640. By comparison, the most frequently published of the plays, Richard III, went through six editions by 1622, the year before the great Folio edition of the plays appeared in print, thus ensuring the separation of the drama from the poetry for several centuries to come.

What was the reason for the extraordinary popularity of Venus and Adonis? Sex, of course, or rather, the tantalizing prospect of sex between the mythical goddess of love and the most handsome of mortals, a violently erotic death of Adonis by the boar, and some flashy writing by an author already known in some circles as an “upstart crow.” The audience for this racy narrative was mostly educated young men, often on their way up to or down from Oxford or Cambridge, a readership that initially constituted a sizeable share of the emerging book-buying population in Shakespeare’s day. As the century wore on, though, women too became frequent readers of the poem.

2. The same is true of Shakespeare’s more serious poetic “sequel” with its noble heroine, The Rape of Lucrece, initially published in 1594, and only slightly less popular than Venus and Adonis. The Rape of Lucrece, or Lucrece, as stated more simply on the original title page, is Shakespeare’s only work in which a woman’s name appears alone in the title. With the drama, even Cleopatra has to share top billing with Antony. The same is true for Juliet and her Romeo. The other named persons in the play titles are all men. In naming his narrative poem after a woman, and a noble Roman woman at that, Shakespeare was signaling his poem’s affiliation with the highly popular tradition of female complaint poems that circulated widely under Queen Elizabeth.

3. Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1609), often considered to contain the finest lyrics in the English language, was barely noticed in his lifetime and for nearly two centuries thereafter. Why so? Theories abound, usually to do with changing literary tastes in Jacobean England, but this and other mysteries continue to envelope these wonderful poems, including questions of the identity of the “young man” as well as the “dark lady.”

4. Should the Sonnets be read as telling a true story of Shakespeare’s loves? Many scholars say no, but this hasn’t stopped the impulse to do so—so real and immediate their passions seem, and so up-to-date in their sexual preferences and transgressions.

5. On the general question of authorship, did the person we call Shakespeare write the poems generally attributed to him? There seems little doubt that he was the author of the two narrative poems. His name appears on the dedicatory page to each. With the Sonnets, his name is likewise conspicuous, crawling boldly and possessively along the top of the page. As for that most mysterious of poems, “The Phoenix and Turtle,” Shakespeare’s name appears at the end of the poem in the original 1601 publication. So not much doubt here.

But what about the narrative poem placed at the end of the 1609 edition of the Sonnets called A Lovers Complaint, in which a seduced maid plaintively—and not quite repentantly–recounts her seduction at the hands of a young man? So close to the situation in the Sonnets and yet, stylistically, to some readers not quite close enough to banish doubts about the poem’s authorship. But, if it’s not Shakespeare, then who? Suppose we accept, as many do, that Shakespeare occasionally collaborated with others in writing some of his plays, might not the same be the case here, and that what we have is something of a workshop poem? Shakespeare in the company of another, the master teaching the apprentice. And just who might that other person be? Maybe, just maybe, the “dark lady” herself, sometimes identified with the poet, Aemelia Lanyer, the first female, in fact, to publish a volume of verse in England just two years after the sonnets appeared? A guess, of course, with no evidence to back it up, but anyone who travels very long in Shakespeare-land is entitled to a fantasy or two. But, nevertheless, it’s an ongoing question that will continue to be debated and examined by scholars.

Featured image credit: Royal Park of the Palace of Caserta – Venus and Adonis Fountain by Livioandronico2013. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Facts about Shakespeare’s sonnets and poems appeared first on OUPblog.

February 22, 2018

Animal of the Month: Interactive guide to polar bear anatomy

From white fur to large paws, we all know what the largest bear species in the world looks like, but how much do you actually know about the anatomy of polar bears?

So far this month, we have explored how climate change affects our Animal of the Month. Now, we would like to take some time to appreciate the anatomy of the polar bear, particularly the ways in which the bear has adapted to its environment and lifestyle. Hover over the magnifying glasses in the picture below to learn more about this beast of the Arctic.

Background image credit: Polar Bears on Thin Ice by Christopher Michel. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Featured image credit: Hey, I can see myself! by Smudge 9000. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr .

The post Animal of the Month: Interactive guide to polar bear anatomy appeared first on OUPblog.

February 21, 2018

An’t please the pigs

My database on please the pigs is poor, but, since a question about it has been asked by an old and faithful correspondent, I’ll say about it what I can. Perhaps our readers will be able to contribute something to the sought-for etymology.

When a word turns out to be of undisclosed or hopelessly obscure origin, we take the result more or less in stride, but it comes to many as a surprise to hear that the circumstances surrounding the emergence of an idiom are beyond reconstruction. In this blog, I have discussed quite a few puzzling phrases (it is raining cat and dogs, pay through the nose, kick the bucket, by hook or by crook, whip the cat, it makes nine tailors to make a man, to put a spoke in someone’s wheel, and so forth), and, although sometimes I ventured to share the opinion that seemed the most reasonable to me, I could never insist on it: the situation in which this or that picturesque phrase was coined happens always or nearly always to be forgotten. Our ignorance is especially irritating because words may be millennia old, while our idioms, unless they are so-called familiar quotations from Classical antiquity or translations of Greek and Latin adages (those people could coin wise sayings and aphorisms with the ease incomprehensible to us), rarely antedate the seventeenth century. Metaphors (as in whip the cat and their likes) in our languages are in general post-Renaissance phenomena.

This is the legendary church in Winwick, Lancashire. Image credit: St. Oswald parish church in Bad Kleinkirchheim by Popie. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is the legendary church in Winwick, Lancashire. Image credit: St. Oswald parish church in Bad Kleinkirchheim by Popie. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In the phrase an’t please the pigs, an is an obsolete synonym of “if.” Unexpectedly, “if (should) it please the pigs” means “if circumstances allow; Deo volente, that is ‘with God’s will’”. Why? Where do pigs come in here? Today, hardly anyone uses this phrase, and not many people know it. Yet it is included in all big dictionaries, none of which offers an explanation, while sometimes pointing out that the old conjectures make little sense. Even the indomitable E. Cobham Brewer did not risk a hypothesis. My database on please the pigs spans the period between 1780 and 1884, with most contributions going back to 1852.

Since pigs in please the pigs makes so little sense, it has been suggested time and again that the word stands for pyx or pixies, or piga. A Pyx is a container in which the reserved Eucharist is kept. The change from Pyx to pigs might have occurred, given the militant anti-Catholic mood of the Reformation, but no facts bear out this etymology, and the entire hypothesis seems most unlikely. Pixies, the second candidate, are well-known creatures of folklore. Though they may lead astray a wayfarer (who will then be pixie-led), unlike so many other figures of popular imagination, they are usually not malicious, and there seems to be no reason why they should be or have been “pleased,” propitiated, or gratified. The change from pixies to pigs would also be hard to account for. Finally, Old Engl. piga “girl, maiden,” with reference to the Virgin, is a ghost word. Danish pige indeed exists, but its English cognate does not. And once again, such a sacrilegious change would be beyond comprehension.

It would be hard to confuse such pixies with pigs. Image credit: Scan illuatration on page of book in a series of fairy tales. A warning to children by John D. Batten. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It would be hard to confuse such pixies with pigs. Image credit: Scan illuatration on page of book in a series of fairy tales. A warning to children by John D. Batten. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.There is a sizable body of legends about how people wanted to build a church in a certain place, but some animals intervened, and, as a result, the construction site was changed. One such legend concerns Winwick, Lancashire. The parish church “stands near that miracle-working spot where St. Oswald, king of the Northumbrians, was killed. The founder had destined a different site for [the church], but his intention was overruled by a singular personage….” The foundation of the church was laid. Yet “the approach of night brought to pass an event which utterly destroyed the repose of the few inhabitants around the spot. A pig was running hastily to the site of the new church; and as he ran he was heard to cry to scream aloud ‘We-ee-wick…!’ Then, taking up a stone in his mouth, he carried it to the spot sanctified by the death of St. Oswald, and thus employing himself through the whole night, succeeded in removing all the stones which had been laid by the builders…. Thus the pig not only decided the site of the church, but gave a name to the parish. In support of this tradition, there is the figure of a pig sculptured on the tower of the church, just above the western entrance….” The author of the article asks: “May not the phrase please the pigs have originated in the above tradition?” I find the plot familiar, the story entertaining, but the etymology fanciful.

John Bradford (1510-1555). Image credit: Life of Master John Bradford, 19th century via Ptolemy Caesarion. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John Bradford (1510-1555). Image credit: Life of Master John Bradford, 19th century via Ptolemy Caesarion. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Perhaps the following observation, made in 1850, deserves attention. Alfred Gatty (1813-1903), vicar and an author, quoted the sixteenth-century Protestant martyr John Bradford. Here are a few of Bradford’s pronouncement’s: “And so by this means, as they save their pigs, which they would not lose (I mean theri worldly pelf), so they would please the Protestants, and be counted with them for gospellers, yea, marry, would they”; also: “Now are they unwilling to drink of God’s cup of afflictions… lest they should love their pigs with the Gergenites,” and: “This is a hard sermon: ‘Who is able to abide it?’ Therefore, Christ must be prayed to depart, lest all their pigs be drowned. The devil shall have his dwelling again in themselves, rather than in their pigs.” The biblical reference is to the pigs of Gergesenes (Mark VIII: 28 and the following). As we can see, there have been pious and impious pigs in history.

Vicar Gatty wrote: “These and similar expressions in the same writer without reference to any text upon the subject, seem to show, that men loving their pigs more that God, was a theological phrase of the day, descriptive of their too great worldliness. Hence, just as St. Paul said ‘if the Lord will’, or as we say ‘please God’, or as it is sometimes written, ‘D. V.’ [= Deo Volente], worldly men would exclaim ‘please the pigs,’ and thereby mean that, provided it suited their present interest, they would do this or that thing.”

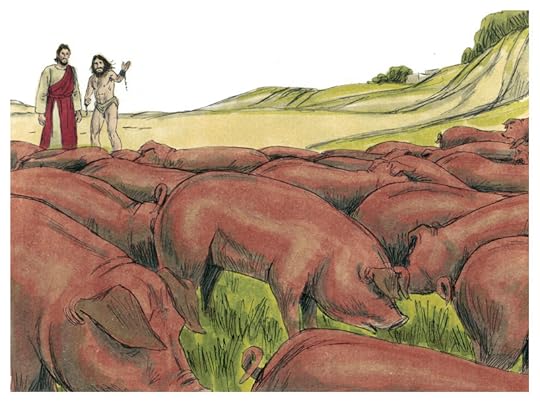

Perhaps this is how our idiom originated. Image credit: Biblical illustration of Gospel of Mark Chapter 5 by Jim Padgett. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps this is how our idiom originated. Image credit: Biblical illustration of Gospel of Mark Chapter 5 by Jim Padgett. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.I don’t think this explanation sounds too convincing, but there may be something in it. In any case, it sounds much more interesting than references to pixies and Pyx. A minor problem with our idiom about which Alfred Gatty wrote in 1850 that it is “too vulgarly common not to be well known” to the readers of Notes and Queries but which now seems to have fallen into desuetude concerns the alliteration (please the pigs). It happens only too often that in such phrases the second word is chosen for the sake of the euphonic effect.

Those who won’t be satisfied with the material presented above are advised to mediate on the origin of the phrase to save one’s bacon and the pub name pig and whistle, and remember that, however hard etymological research may be, pigs, contrary to conventional wisdom, occasionally fly.

Featured Image: Can’t they fly? Yes, they can. Image credit: “Pigs Fly Funny Hog Piggy Wings Pork Swine Hoof” by DigiPD. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post An’t please the pigs appeared first on OUPblog.

The ‘most wonderful plants in the world’ are also some of the most useful ones

In the popular imagination, carnivorous plants are staples of horror films, high-school theater productions, and science-fiction stories. Many a child has pleaded with her parents to buy yet another Venus’ fly-trap to replace the one she has just killed by over-stuffing it with raw hamburger rather than the plant’s natural diet of flies, ants, and other small insects.

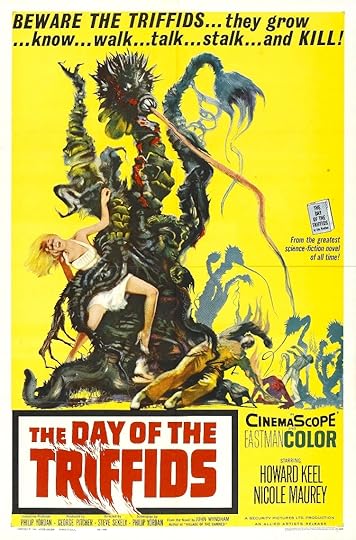

Poster for the 1962 film, The Day of the Triffids by Joseph Smith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Poster for the 1962 film, The Day of the Triffids by Joseph Smith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Botanists likewise have been fascinated by these evolutionary oddities that have seemingly turned the natural order of things on its head. Rather than being eaten by herbivores, these plants have evolved a bewildering away of adaptations to attract, capture, kill, and digest animal prey—usually insects—and then to use the digested and absorbed nutrients to enhance the plant’s growth and development.

These adaptions—which so fascinated Charles Darwin that he wrote an entire book on what he referred to as ‘the most wonderful plants in the world’—include the sundew’s moveable tentacles coated with sticky glues to ensnare passing insects; the slippery, waxy coatings of the inside of pitcher plants’ pitchers that prevent prey from escaping their watery grave; the fluid-filled leaves of the Venus’ fly-trap that change their shape when an insect touches them, buckling closed in less than a tenth of a second; and many, many more. These adaptations also are inspiring biotechnologists to create biomimetic devices that are finding a variety of uses in our daily lives and novel drugs to treat a broad spectrum of diseases.

In recent years, researchers have looked to the myriad ways that carnivorous plants trap and digest insects to develop biomimetic materials with a surprisingly diverse range of uses.

For example, one of the primary attractors of prey to pitcher plants is the fleshy, often brightly-colored ‘peristome’ (literally ‘around the mouth’) that surrounds the gaping mouth of the plant. When the peristome is dry, insects can walk about it with abandon. But when it gets wet, from rain, fog, dew, or secretions of nectar by the plant itself, it becomes super-slippery and insects ‘aquaplane’ off of it and fall into the pitcher. Not only has the peristome led to the development of a range of natural, non-stick surfaces called ‘slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces’ (SLIPS)—think Teflon without the PFOAs—but because water flows in only one direction along the peristome, it also is leading to the development of controllable microfluidic devices, including drug-delivery systems, self-lubricating machines, and new types of agricultural drip-irrigation systems.

The ‘snap-buckling’ Venus’ fly-trap provides similar inspiration. Although scientists have been studying the fly-trap for more than a hundred years, it is only in the last decade that a detailed understanding of its inner workings. Briefly, when the trap is open, the leaf is curved outward, bent and stretched in two directions across the leaf. But when an insect touches the trigger hairs at the base of the trap—not just once, but at least twice, to avoid false alarms—the stretched leaf relaxes, causing the leaf to quickly buckle and snap shut.

A Venus’ fly-trap (Dionaea muscipula) occasionally captures prey much larger than the plant can swallow. Photograph by the author.

A Venus’ fly-trap (Dionaea muscipula) occasionally captures prey much larger than the plant can swallow. Photograph by the author.Snap-buckling is a low-energy way to change the shape of a variety of structures. For example, microscopic lenses can be fabricated that use snap-buckling to shift between convex and concave states. Because convex and concave lenses have different focal points, users of these micro-lenses could quickly re-tune micro-optical devices on the fly (so to speak). At a much larger scale, snap-buckling has been suggested as a way to design and develop complex shades for the outer, free-form façades of modern buildings.

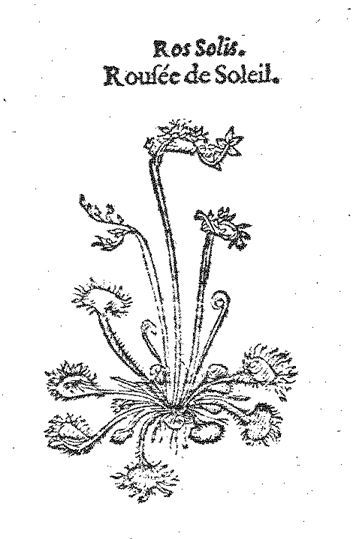

Medical devices often deliver medicines, and as evolutionary biologists uncover the biochemical secrets by which carnivorous plants kill and digest prey, they have also revived interest in their pharmacopeia. Extracts of sundews (Drosera species) have been used since at least the 16th century to treat respiratory diseases, including tuberculosis. A sundew was the first carnivorous plant to be illustrated in Rembert Dodoens’ 1554 L’Histoire Des Plantes, although Dodoens did not remark on its medicinal properties. In 1636, the English botanist John Gerard summarized its known ‘vertues,’ in his Herbal, including its use for `treating consumption.’

First illustration of a carnivorous plant, the sundew Drosera rotundifolia (from Dodoens 1554). Public domain via Project Gutenberg.

First illustration of a carnivorous plant, the sundew Drosera rotundifolia (from Dodoens 1554). Public domain via Project Gutenberg.Native peoples and early colonists of North America alike were familiar with the curative properties of the American pitcher plants (Sarracenia species). For example, the Cree First Nation of Eeyou Istchee in Northern Quebec use a decoction of the leaf of the northern pitcher plant (S. purpurea) to treat Type-2 diabetes. In 1849, the South Carolina botanist, physician, and secessionist Francies Peyre Porcher made a detailed study of the uses of roots of the yellow pitcher plant (S. flava) to treat gastric upset, including indigestion, nausea, headache. And most Sarracenia species synthesize coniine, which may both attract insects and stun them once they are captured by the plant. Although coniine is perhaps better known as the poison that most likely was used to kill Socrates, it also is being studied as a next-generation, non-addictive pain reliever.

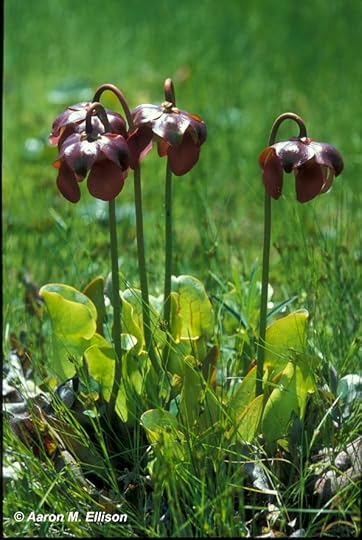

The northern pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea). Photograph by the author.

The northern pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea). Photograph by the author.As carnivorous plants have moved from the fanciful, across the scientists’ workbenches, and into everyday utility, it is imperative that we conserve them in the wild and take care of their natural habitats. Poachers regularly deplete or extirpate natural populations, and carnivorous plant enthusiasts often plant them in sites where they would not otherwise occur (and yes, like John Wyndham’s triffids, real carnivorous plants can become noxious weeds with knock-on effects on native fauna, including our native bumble bees).

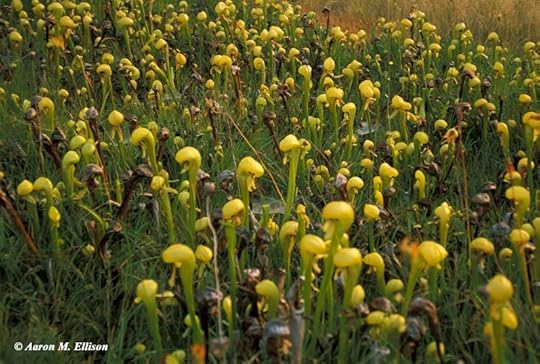

A field of carnivorous Cobra Lilies (Darlingtonia californica) in southern Oregon, USA. Photograph by the author.

A field of carnivorous Cobra Lilies (Darlingtonia californica) in southern Oregon, USA. Photograph by the author.So, while you’re enjoying carnivorous plants in books, the stage, and the big screen, or learning to cultivate them on your windowsill, remember that nature not only has value to us, but also simply has value.

Featured image: “Carnivorous Plant Nature Macro 217187” by PublicDomainPictures. CCO Creative Commons via Pixabay .

The post The ‘most wonderful plants in the world’ are also some of the most useful ones appeared first on OUPblog.

February 20, 2018

200 years of Parkinson’s disease

The 200th anniversary of James Parkinson’s seminal Essay on the Shaking Palsy gives cause for commemoration and reflection. Parkinson’s astute observation and careful description of only six patients led to one of the earliest and most complete clinical descriptions of Parkinson’s disease. With the concept of a syndrome still not fully realised, Parkinson was among the first writers to unify a set of seemingly unrelated symptoms into one diagnosis.

Parkinson was a true polymath; his biography reveals a colourful life even for the time: from botanist and palaeontologist to political and medical reformer. His extensive writings on patient autonomy, the role of the clinician, and the public management of health portray a professional deeply concerned with the responsibilities of health care specialists in the widest sense.

He challenged the medical community to find therapeutic interventions for the syndrome he described and rightly suspected progress would require better understanding of the underlying pathology. Over the last 200 years, some of the most eminent names in the neurosciences have risen to Parkinson’s challenge. From the great French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who named the condition in Parkinson’s honour, to Konstantin Tretiakoff, Arvid Carlsonn, and Oleh Hornykiewicz there has been an iterative improvement in understanding. A traceable narrative builds on the foundations laid by Parkinson.

Featured image credit: Signature James Parkinson 1805, Royal Medical Chirurgical Society Obligation Book 1805 by Whispyhistory. CC via Wikimedia Commons

The post 200 years of Parkinson’s disease appeared first on OUPblog.

The Reformation and Lutheran baroque

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century has long been associated with a reprioritization of the senses; a shift from visual to verbal piety, and from religious images to words. In many parts of northern Europe, the rich visual culture of the late-medieval church — sculptures, altarpieces, paintings, stained glass, and ecclesiastical treasures—fell victim to the purifying zeal of iconoclasts. Martin Luther was himself no iconoclast, but even in Lutheran territories religious life after the Reformation was built around the spoken and printed word: around the sermon, around the use of catechisms, prayer books and hymnals, and around Luther’s translation of the Bible.

How, then, are we to explain the flourishing of Lutheran visual culture that occurred in Germany during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries? Why did Lutheran patrons commission costly images and richly decorated churches? How can we reconcile Lutheran emphasis on the simple hearing of God’s Word with magnificent visual monuments such as Dresden’s Frauenkirche, built between 1726 and 1743?

The seeds of this rich visual culture—of the Lutheran baroque—were sown in the sixteenth century by the reformer himself. Although he was no great fan of religious images, Luther was moved to defend them by the iconoclasm of some of his fellow evangelicals, the ‘fanatics’, as he termed them. Images became, for Luther, a matter of Christian freedom and a sign of moderation in the face of radical threat. Luther also recognized that images could help Christians to understand and experience faith. Many of his key religious texts, including his 1534 complete German Bible, contained elaborate illustrations, woodcuts that served not only to visualize but also to interpret the texts that they accompanied.

However, the writings of theologians can go only so far towards explaining the evolution of confessional consciousness and the shaping of religious identity. Lutheran attachment to religious images was a result not only of Luther’s own cautious endorsement of their use, but also of the particular religious and political context in which his Reformation unfolded. After the reformer’s death in 1546, the image question was fiercely contested once again. But as Calvinism, with its iconoclastic tendencies, spread, Germany’s Lutherans responded by reaffirming their commitment to the proper use of religious images. In 1615, Berlin’s Lutheran citizens even rioted when their Calvinist rulers removed images from the city’s Cathedral.

Bronze statue of Martin Luther, in front of the Frauenkirche in Dresden by Ad Meskens. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bronze statue of Martin Luther, in front of the Frauenkirche in Dresden by Ad Meskens. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Images also came to play a key part in the new forms of Lutheran piety promulgated during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by figures such as Johann Arndt. The crucifix in particular became an important devotional image. Crucifixes—which had been objects of particular hatred for Calvinist iconoclasts—adorned Lutheran churches and homes, and Lutherans prayed, meditated, and even wept before them.

The flourishing of Lutheran visual culture was fostered not only by transformations in Lutheran piety but also by patrons’ desire for representation. Princes, nobles, and prosperous burghers sought appropriate forms of visual commemoration for themselves, their families, and their wider communities. In seventeenth-century Saxony, Lutheran patrons chose artists who introduced the visual idioms of the Catholic baroque into Protestant painting and sculpture. Elsewhere, the quest for modern, stylish representation took other forms. In neighbouring Brandenburg-Prussia, for example, the presence of a Calvinist court and the prominence of Pietism held the exuberance of the Lutheran baroque in check. The development of a rich Lutheran visual culture was not, as these two examples suggest, pre-determined by the events and ideas of the Reformation itself, but was rather the result of long-term changes and of particular local circumstances.

As historians of religion increasingly turn their attention from doctrine and devotional life to the broader examination of mental worlds shaped by a sense of religious belonging, the importance of images as a source will continue to grow. Images provide a lens through which to examine what it meant to be Lutheran at different times and in different places; they serve as a yardstick to measure the development of confessional consciousness. Nothing conveys the contradictions inherent in early modern Lutheranism, and the complexity of the Reformation’s long-term impact, as effectively as a quick trip to Dresden’s Frauenkirche.

Featured image credit: Interior of the Frauenkirche in Dresdenby Gryffindor. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post The Reformation and Lutheran baroque appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers