Oxford University Press's Blog, page 279

February 14, 2018

The weight of love: ‘love locks’ as emotional objects

On the night of 8 June 2014, a section of the metal barrier on the Pont des Arts in Paris collapsed under the weight of thousands of padlocks which had been attached to it. Since the first decade of the twenty-first century, it has become increasingly common for famous (and sometimes less famous) bridges, and, increasingly, other monuments, to become encrusted with small padlocks in celebration of romantic love. The genesis of the practice is obscure, with a number of bridges claimed as the original site, but the ritual is generally consistent: an ordinary padlock is engraved or marked with the names or initials of a pair of lovers, and often a date. The lock is then attached to the structure of the bridge, and the key thrown into the water so that the unlockable padlock becomes a symbol of an enduring relationship.

The practice of depositing these ‘love locks’, as they have become known, has parallels with much earlier rituals. As public performances of emotion, they resemble the medieval practice of hanging votive offerings around the shrines of saints; the throwing of the keys into the water resonates with the ritual deposition of weapons, coins, and pilgrimage badges into rivers and wells from the Iron Age to the modern period. As with these, the ritual attaching of the lock and discarding of its key may represent not just a commemoration of love, but a way of empowering hope, or enacting a wish.

Love locks have been considered as contemporary examples of archaeological depositions and ritual behaviour, but here I want to approach them from the perspective of the intersection between the history of emotions and the history of material culture, in order to focus on them as ‘emotional objects’. Emotional objects are things which humans use to symbolise, express, produce, and regulate their emotions. In the process, objects can acquire, or lose, ‘emotional value’, which can be positive or negative, different for different people and groups, and can change over time. Such objects may become powerful, able to produce emotional as well as material effects. Often their materiality is essential to the way they function emotionally, but their emotional value may be unrelated to their economic or aesthetic values.

The most obvious way that love locks function as emotional objects is in representing romantic love. The small, cheap, usually quite unremarkable padlocks acquire emotional value in several ways — they represent the relationship between two people, and in many cases commemorate a significant date. In this sense they rely on memory and an existing relationship for their value. They also derive emotional value from their association with a particular place. Most of the sites where there are major accumulations of love locks are tourist attractions, which are places of significant beauty or historical importance. The locks serve to represent the lovers in these desirable places once they are no longer present, and the setting adds emotional value to the lock and to the ritual.

Detail of love locks on the Pont des Arts, Paris, July 2014 by Sarah Randles. Used with permission.

Detail of love locks on the Pont des Arts, Paris, July 2014 by Sarah Randles. Used with permission.The material nature of the locks is integral to their use in this practice. They must be able to be secured to the structure of the bridge or other monument, and must be unable to be unlocked without their keys (or in some cases without the code for a combination padlock). But the sturdiness of the padlocks and another characteristic of emotional objects — their propensity to attract other, similar objects to themselves — has also contributed to their negative emotional value for some people. Collectively they threaten to overwhelm the monuments to which they are attached, both visually and materially. Civic authorities have attempted, largely unsuccessfully, to ban their use, or have resorted to cutting them off the structures. In some cases these measures have been prompted by a concern for the integrity of the structures and the safety of the people using them, but there have also been protests against the love locks on the basis of aesthetics, arguing that they destroy the visual appeal of the monuments which attracted the locks in the first place. The antipathy towards love locks has itself been expressed with emotional objects, including giant padlocks and hubcaps. Some cities have attempted to deflect the practice away from significant monuments by building custom structures for love locks. In Paris, the weight of the love locks forced a redesign of the railings on the Pont des Arts so that it would no longer be possible to attach locks to the bridge.

The removal of the locks from bridges, however, also prompted outcries, providing a testament to the emotional value of the padlocks, not just to those who deposited them, but to wider communities who have come to see them as a material and emotional enhancement to their cities. Even in their afterlife, the lovelocks have retained emotional value, which has led, in some cases, to their preservation. In Melbourne, concern for the integrity of the Southbank footbridge was matched by a concern for the materiality of the padlocks, so that they were not cut off, but rather slid from the support wires which were then replaced. Artists were commissioned to make objects from some of the lovelocks, ensuring their continued existence, and others were distributed via a lottery to raise funds for charity. The emotional value of the love locks now centred on a direct relationship with them as objects of desire, repurposed as representing the ‘heart of the city’, and a love which had shifted from eros to caritas.

Love locks may start out as small, quotidian, inexpensive, and not particularly attractive items, but through their emotional context, they can be transformed into powerful objects with the ability to change both the material and the emotional worlds around them. In doing so, they demonstrate the cyclic nature of the relationship between emotions and materiality: emotions produce objects, and objects produce emotions.

Featured image credit: Love locks on the Pont des Arts, Paris, July 2014 by Sarah Randles. Used with permission.

The post The weight of love: ‘love locks’ as emotional objects appeared first on OUPblog.

February 13, 2018

Simon of Montfort and the Statutes of Pamiers

“Kill them. The Lord will know those that are his.” This statement, attributed to a Cistercian abbot at the sack of Béziers in 1209, encapsulates for the modern mind the essence of the Albigensian Crusade (1208-1229). No doubt the bloody reputation of the crusade is well-earned: the conflict had as its object “to abolish heretical perfidy” in those lands deemed to be most afflicted, namely the region of modern France between the Garonne and Hérault rivers. This abolition was to be accomplished by dispossession: “when the heretics have been banished, Catholic inhabitants should be substituted, who may serve in holiness and justice before God according to the discipline of [the crusaders’] orthodox Faith.” This substitution was unlikely—indeed, never intended—to be peaceful: blood would be shed to do the Lord’s work.

However, a view of the Albigensian Crusade that encompasses only its violence will miss a great deal of the movement’s significance. The Catholic elected by the crusader army to inhabit and rule the land conquered in 1209 was Simon of Montfort, a middling French lord and veteran of the Fourth Crusade. He was undoubtedly a man of blood. He sacked and fired villages and towns, burned both unrepentant and—in at least one case—repentant heretics, and massacred captured garrisons. Perhaps his most infamous act was the calculated cruelty of blinding and mutilating one hundred men taken at the fall of Bram. But the investigation that looks no further than Simon’s blood-spattered chainmail ignores the remarkable legislative programme of reform that he introduced under the shadow of his sword. This is not to write an apologetic for the man, but rather to emphasise how the causes of Christian reform and baronial violence in the Albigensian Crusade were linked.

The boldest statement of Simon’s vision can be found in the constitution he issued on 1 December 1212 in order to consolidate his conquests. Known as the Statutes of Pamiers, named after the town to which he called a parliament of bishops, knights, and local burghers to compile the legislation, the document is a remarkable blend of martial law and reform charter. Two and a half years before the first issue of Magna Carta, the Statutes guaranteed the free provision of justice for all. Moreover, “no man shall be sent to prison or kept captive as long as he can give sufficient pledges that he will stand in court.” Others insisted on the importance of the accused “being convicted of or having confessed to” a given crime. Condemnations for heresy were restricted to the judgement of competent clergy. As neither Simon nor, to our knowledge, any of the other member of the parliament had taken a legal education—though he and others had important connections to Parisian theologians—the inclusion of such concerns suggests a practical engagement with good government.

Pope Innocentius III excommunicating the Albigensians (left), Massacre against the Albigensians by the crusaders (right) by Chroniques de Saint-Denis. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.

Pope Innocentius III excommunicating the Albigensians (left), Massacre against the Albigensians by the crusaders (right) by Chroniques de Saint-Denis. Public domain via

Wikimedia Commons

.For example, a series of clauses limit the amount of tallage — a semi-arbitrary tax on tenants — that a lord might exact, permit those subject to tallage to abandon their lord for another in protest of excessive demands, and prevent lords from extorting pledges to force their tenants to stay. This allowed at least a modicum of agency to the peasant in the agricultural labour market at the expense of the very baronial class of which Simon was a member. Those subject to tallage could also take collective action against oppressive lords, in which case Simon would call a parliament in order to investigate their claims and impose and enforce limits.

Of course, the Statutes had more pressing concerns than the free provision of justice and the amelioration of serfdom; on some level these clauses probably served to cajole support for a regime that was exceedingly unpopular among the citizenry of Toulouse and nobility of the surrounding region. More clauses stressed martial measures and the promotion of orthodoxy than enshrined liberties. Enforcement of the latter could also be spotty. Despite the limitations on tallage and mechanisms for its relief, the villagers of Rieux would have to wait almost fifty years until the reign of King Louis IX to find redress for the extortion imposed by one of Simon’s French followers. On the other hand, Simon reversed the unjust dispossession of a Pons Peyre of Bernis upon appeal in 1217, suggesting that an accountable government was working, at least in places. Moreover, the only known execution of heretics after the promulgation of the Statutes and before Simon’s death, the burning of seven Waldensians discovered at Morlhon in 1214, took place after the victims had been examined and refused to recant before the cardinal and papal legate Robert of Courson. Grisly as the final example is, it contrasts with the mass spontaneous burnings of the years before Pamiers noted above. As revealed to us by the limited sources of Simon’s perpetually martial and short-lived regime, the Statutes had indeed been implemented, if not uniformly.

The juxtaposition of the redress of Pons Peyre’s grievance and the burning of the Waldensians is a useful one for understanding not only the implementation, but also the conception of the Statutes of Pamiers. Simon’s anxieties about defence, orthodoxy, and justice were inseparable from each other; they are jumbled without distinction in the document itself. To some extent, the guarantees of due process and restraints on arbitrary power were undeniably attempts to placate a resentful and fractious conquered populace. But they also mirror a wider development of governmental accountability and righteousness among the ruling classes in the thirteenth century. Much of the Statutes of Pamiers anticipates—and probably served as a model for—measures undertaken by the royal administration of Saint Louis of France (r.1226-1270), a man of a similarly violent piety. Simon’s legislation at Pamiers demonstrates that Louis’ famed pursuit of Christian government later in the century was by no means novel; moreover, Simon’s trailblazing suggests that the exceptional baron could have just as much interest in such political projects as that exceptional king.

Featured image credit: Carcassonne castle walls by Philipp Hertzog. CC BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Simon of Montfort and the Statutes of Pamiers appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of precision medicine

In April 2003, researchers from the Human Genome Project published the result of their painstaking work; a complete sequencing of the human genome. This ground-breaking feat has ushered in the current “post genomic” era of medicine, whereby medical treatment is becoming increasingly personalised towards an individual’s specific lifestyle and genetic makeup.

Precision medicine has a particularly important role in the treatment of inherited diseases and cancer, as physicians often screen for genetic makers in their patients, such as the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Genomics can also be used to guide oncologists to determine which drugs will be most effective in shrinking a malignant tumour, creating a precise form of attack against the faulty cells.

Yet, it is increasingly clear that clinicians are only tapping the surface of what precision medicine can offer. Despite huge advances in the underlying science, research and development of new medical products has steadily fallen – leaving patients at the mercy of life-limiting illnesses. In the video series below, Professor Richard Barker discusses why precision medicine is so important, and offers some solutions to the problems it faces today.

Richard Barker discusses his vision for the future of precision medicine and the challenge of turning huge research projects into routine medical practice.

Is there a need for public education on precision medicine, especially the importance of data security?

Should the biomedical industry be less regulated?

In this final video, Professor Barker explains his worries over the “innovation gap” in bioscience, the five potential causes behind it, as well as the solution: precision medicine.

Featured image credit: DNA-String-Biology by qimono. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The future of precision medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy, healthy, and empowered in love

If, as Tolstoy says, all happy families are alike, then why is it so challenging to identify what it is—psychologically and sociologically—that makes them so happy? We can easily identify the markers of unhealthy relationships; for example, domestic violence—commonly known as intimate partner violence in an academic setting—is controlling behavior rooted in the power and control by one person over another that is manifested through physical, verbal, psychological, isolationist, and sexual violence. I’ve spent twenty years working to empower women experiencing intimate partner violence, and so, to celebrate Valentine’s Day this year, I want to focus on the positive characteristics experienced in intimate romantic relationships. Nothing says romance like individual empowerment and the cultivation of healthy, supportive, and interpersonal practices.

Characteristics of healthy relationships might be experienced differently across groups of women and might look different throughout cultures around the world. What we do know about the characteristics of healthy relationships is that interactions and exchanges that occur between two people are rooted in three universal principles: respect, effective communication, and awareness of self and identity. When individuals—particularly women—learn to identify and pursue these relational markers, not only do their relationships improve, but they also benefit from widely felt improvements in the rest of their lives.

First, persons in intimate relationships want to respect their partner and feel that they are respected in return. This involves understanding your own values and beliefs, standing up for the things you believe in, and the ability to express those ideals to another person. Respect means the other person understands your values and beliefs and, tries to fully examine why those values and beliefs are important to you. Over the years as a clinical social worker and educator, I’ve listened to women from different cultures explore their own value systems and discover how sharing these values with their partners and letting that shape the relationship has improved their happiness. All stories led me to believe that respecting your partner and respecting yourself can lead to a more fulfilling relationship.

The characteristics of healthy relationships is that interactions and exchanges that occur between two people are rooted in three universal principles: respect, effective communication, and awareness of self and identity.

Second, relationships thrive when both individuals practice effective communication. It is important for women to express their thoughts, feelings, and wishes throughout intimate relationships. Both persons in the relationship need to express what they want, what they need, their interests, passions, and desires. Using I statements is key and using what I call “wise mind” is imperative. Wise mind—a concept that is used in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy—is simply the ability to be aware of one’s emotions and thoughts and keep both in balance as you communicate with your partner. As either obvious or counter-intuitive as it may seem, without attentive listening there is no communication. We all want to be heard. I remember participating in a workshop several years ago in which the presenter described how we should listen: “Listen with your heart; listen with your ears; listen with your mind; and listen with your body.” It’s necessary to be present and attentive when your partner speaks to you and when you are trying to convey a wish or desire to your partner.

Finally, persons in intimate relationships need to foster their own self awareness and identity. The old saying is true: “We are products of our past.” Upbringing, successful attachment and bonding with our parents or other caregivers, and the positive development of self-esteem impact us as adults. Many women who experienced adversity during childhood and/or adolescence develop an empathic stance. Working through those adverse experiences will impact how we feel about ourselves and improve self-esteem. The more we understand how we feel about ourselves (i.e., self-esteem assessment), the easier it will be for persons in intimate romantic relationships to express what they want, their personal and professional wishes in life, and to expect respect.

As women experience these characteristics in intimate romantic relationships, they become more aware of their talents and gifts, and they are empowered to pursue dreams and goals personally and professionally. The process of experiencing empowerment becomes real because women are respected, heard, supported, and encouraged by their partners in their intimate relationships. And, as women assess their self-esteem and identify what they want in life—whether it is pursuing educational opportunities, job promotions, starting a family, or chasing a dream—women become more confident, take more risks, and find new adventures in life. Women essentially become empowered to make choices, to create change, and are more confident because they are experiencing positive healthy characteristics in intimate romantic relationships.

Featured image credit: Take this flower by Evan Kirby. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Happy, healthy, and empowered in love appeared first on OUPblog.

February 12, 2018

Saving Butch Cassidy’s charitable legacy

Paul Newman died in 2008, leaving behind a wonderful legacy of films and philanthropy. Of his many iconic movie roles, my favorite is Butch Cassidy. Every time I introduce a child or a grandchild to Butch and Sundance, as the climatic ending scene approaches, I quietly hope to myself that this time it will conclude differently with the heroes escaping alive.

Unfortunately, Mr. Newman’s death in real life triggered a tax problem which now threatens his charitable bounty. Congress almost solved this problem in the new tax law passed in December 2017 but, at the last minute, failed to do so. Congress should now move quickly and in bi-partisan fashion to protect Mr. Newman’s philanthropic enterprise by permitting the charitable foundation he established to continue owning the Newman’s Own food brand.

The story is a tale of unintended consequences which starts in 1969, the year in which Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid debuted. In that year, Congress amended the Internal Revenue Code to stop perceived tax abuses using private, family-controlled charitable foundations. Among the abuses Congress targeted was the tax-favored transfer of family businesses to private foundations. Before the Tax Reform Act of 1969, many families conveyed their closely-held businesses to such foundations, took the resulting income and estate tax deductions, but then contributed little or nothing to charity.

Congress discouraged this behavior in several ways including a new provision in the Internal Revenue Code, Section 4963. This provision prohibits a private foundation from owning more than 20% of any business. This 1969 reform has largely worked, stopping abusive transfers of family enterprises to private foundations.

Fast forward to 2008. Paul Newman’s food products under the Newman’s Own label had generated significant brand loyalty, not least because consumers trusted Mr. Newman’s commitment that all profits will be devoted to charity. On his death, Mr. Newman left his food products business to the Newman’s Own Foundation which continued his charitable legacy. Unfortunately, that transfer of the Newman’s Own family business to this legitimate charity triggered Section 4963’s prohibition on private foundations owning more than 20% of any business.

HK CWB zh:銅鑼灣 Causeway Bay 時代廣場 Times Square basement CitySuper Supermarket in November 2017 by Glearybarsim. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

HK CWB zh:銅鑼灣 Causeway Bay 時代廣場 Times Square basement CitySuper Supermarket in November 2017 by Glearybarsim. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In a version of the recently passed tax bill, then known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the US House of Representatives voted to amend Section 4963 to permit the kind of business transfer Mr. Newman made to his private foundation. Because of the Senate’s procedural rules, this provision was not included in the final legislation. Unless Congress acts soon, the Newman’s Own Foundation will be forced to sell the Newman’s Own food brand to a for-profit corporation.

Such a sale would destroy a critical aspect of the brand – all its profits go to charity. Had the drafters of Section 4963 foreseen in 1969 a situation similar to the one of the Newman’s Own Foundation, they would likely have crafted an exception for bona fide transfers of family businesses to private foundations. The legislation which almost passed Congress in December contained many safeguards to ensure that a family business transferred to a private foundation will be genuinely devoted to charity. Under this legislation, all business profits must be distributed to the foundation, and the foundation must be governed independently of the family of the business’s founder.

There is little time to solve this problem. If Congress does not act this year by amending Section 4963, the Newman’s Own Foundation must sell the Newman’s Own food business this year. That would be regrettable.

In our unfortunately polarized environment, there is today little on which Democratic and Republican members of Congress agree. This is one of these rare areas of bi-partisanship.

The legislation which Congress almost adopted in December passed the Republican-controlled House. Connecticut’s Democratic senators, Richard Blumenthal and Christopher Murphy, have also called for legislation to amend Internal Revenue Code Section 4963 to allow the Newman’s Own Foundation to retain the Newman’s Own business.

It doesn’t get more bi-partisan than this. Congress should amend the Internal Revenue Code to permit the Newman’s Own Foundation to retain the Newman’s Own brand. Butch’s charitable legacy is worth saving.

Featured image credit: 171011-D-SW162-1001 by Chairman of the joint chiefs of staff. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Saving Butch Cassidy’s charitable legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

My author. My friend?

Imagine you’ve sat down with your favorite novel. While you’re reading, what do you feel? If, in part, it’s an emotional connection with a character, you’re not alone. This is a common experience; and plenty has been written about it, in both popular and scholarly spaces. Because it’s powerful and strange, this feeling. Powerful enough to make you cry. Strange in that it’s fictional characters we’re talking about.

But I’m interested in a different feeling we can have while reading fiction, something that sure seems like an emotional connection with the author, the real person responsible for those characters who make us cry. When we read, we might feel as though we are in a conversation with the author, a conversation that is both intimate and emotionally rich. Sometimes this apparent relationship might even be powerful enough to feel like a peculiar form of friendship. As a character in John Green’s novel-turned-movie The Fault in Our Stars says, “My third best friend was an author who did not know I existed.”

Now you may be quick to dismiss this so-called relationship with an author as mere teenage melodrama. But I don’t think you should. Sure, as David Foster Wallace noted, it’s “very strange and very complicated and hard to talk about.” And yes, there is no actual way you could be friends with someone who knows nothing of your existence. Friendship talk in this context is metaphorical at best. But like Wallace and Proust, I think there’s something legitimate at play here, something very real.

But hey, wait, you say, melodrama aside, it’s still fiction. Real author or not, they’re still making stuff up. Someone’s behind the curtain; but there’s still the curtain. That emotional connection you’re feeling to an author is likely a connection to a persona the author constructed, another level of artifice.

Yes. This is a problem. The problem. But bear with me.

Colin Lyas argues that there are limitations to how much an author can fake when they’re writing. If you sense a deeply sensitive, perceptive, or emotionally mature person working in the pages of your favorite novel, it’s hard to imagine that the author could have manufactured those traits. Maybe the author isn’t that way in their non-writing life, but at least at the time of writing, they had to be.

“When we read, we might feel as though we are in a conversation with the author, a conversation that is both intimate and emotionally rich. Sometimes this apparent relationship might even be powerful enough to feel like a peculiar form of friendship.”

If this is right, then when we feel emotionally connected to an author, we are connected to something and someone real. This someone may differ from their everyday self, and may even be a better version of them-self, someone who surfaces only when fingers hit the keys or pick up a pen to make all the tiny adjustments that are so often part of the writing process. But it is some version of them, nonetheless.

Maybe this is part of what makes reading so special. When we read, we have the chance to connect, intimately so, with human beings at their best, their very finest, their most articulate and compassionate and funny and insightful.

Recently, there’s been debate over the possibility of literature making us better people, whether when we read, we become more moral, empathetic, or wise. It’s yet another complicated issue, and one I have nothing to say about today. But at bottom, it’s part of that well-worn debate on why we should read literature and keep it in our schools. On why literature matters. And I do have something to say about that. Read literature to connect. Read literature to find someone who understands the way you see the world and thereby makes you feel less alone. Read to celebrate the fact that we are deeply social creatures, however introverted some of us are. Read to experience a kind of emotional intimacy I’ve experienced nowhere else, an intimacy that is at once peculiar and powerful, quiet and oh so loud.

Featured image credit: book by Patrick Tomasso. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post My author. My friend? appeared first on OUPblog.

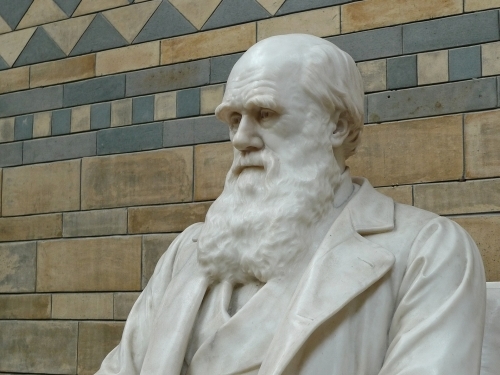

Darwin Day 2018

Monday, 12th February 2018 is Darwin Day, so-called in commemoration of the birth of the father of evolutionary biology, Charles Darwin, in 1809. The day is used to highlight Charles Darwin’s contribution to evolutionary and plant science. Darwin’s ground-breaking discoveries have since paved the way for the many scientists who have come after him, with many building on his work. As a testament to his lasting legacy, Darwin’s Origin of Species was voted the most influential academic book in history in 2015, remaining as ground-breaking and relevant as ever, over 159 years since it was first published.

To celebrate and commemorate Darwin Day 2018, we have put together a collection of academic research about Darwin’s theories and works – including several papers written and co-authored by the great man himself…

A manuscript that requires no introduction: ‘On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection,’ a paper on natural selection, was co-authored by Darwin alongside Alfred Russel Wallace. The paper was first read in front of the Linnean Society on 1st July 1858 before publication on the 20th August in that same year.

Darwin’s ground-breaking text, On the Origin of Species, was published on 24th November 1859. As suggested by the title, the concept of ‘species’ was central to this text. However, definitions evolve – is the concept of ‘species’ taxonomically valid, as Darwin believed, or does it better suit a hierarchical structure as part of a biological organisation, rather than taxonomic rank?

An alternative to Darwin’s theory of evolution, Lamarck’s theory, proposes that the environment of an organism can directly alter traits which are then inherited by offspring, rather than suggesting evolution is a result of random mutations. These two theories may not work in opposition but rather in conjunction through a process known as ‘epigenetics’, which describes how environmental factors can affect gene expression. Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance has now been observed across the many organisms, including insects, fish, birds, rodents, pigs, and plants.

Darwin-Natural-History-Museum by aitoff. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Darwin-Natural-History-Museum by aitoff. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.The Galápagos archipelago is synonymous with Darwin and his research. Since the classification of the genus Geospiza – the so-called ‘finches’ that now bear Darwin’s name – evolutionary research into gene flow of this species has progressed and evolved. Now, there are 16 different species with varying characteristics, such as size and beak structure. Although some mutations have been found in the DNA of the different species, a higher number of epigenetic changes were found between closely-related species of Darwin’s finches.

Darwin’s finches first evolved from an ancestor of the modern Tiaris grassquit, found in South America and the Caribbean. The group of finches diverged from the Tiaris group on the Caribbean islands before spreading to Central and South America, before the finches departed for the Galápagos Islands over two million years ago.

Islands played a key role in Darwin’s observation and experiments on plant dispersal, expunging the old idea that a given species could originate at multiple times and in multiple places. He also saw the capabilities for the dispersal of plant seeds, fruits, and branches, developing ideas of how plants reach islands – earning him the title of one of the founders of plant biogeography.

Darwin focused much of his energy on studying the behaviour of animals, including humans, exploring the role of behaviour in evolution. However, not all of Darwin’s intellectual energy was spent developing his evolutionary ideas. Did you know he devoted a surprising amount of time studying the biology of barnacles?

Not only fascinated by evolution and the biology of barnacles, Darwin was also a keen botanist, and published several papers within in the discipline, investigating the movement and habits of climbing plants, and writing about the complex relationships that the angraecoid orchid group have with specific pollinators within On the Origin of Species. But what impact has Darwin’s legacy had on the history of orchid pollination biology and why is his idea of reciprocal evolution arguably put forward as one of the great contributions to evolutionary biology?

Darwin’s fascination with botany and plant life is well documented, and he described the Venus fly trap as ‘one of the most wonderful [plants] in the world’. Research has shown that carnivory has evolved at least six times independently in plants. Despite this, independently-evolved carnivorous plants show similar mechanisms for digesting and assimilating their prey, and their ‘traps’ can range from being a complex mechanism to simply being sticky.

Darwin was well known for the vast array of scientific papers, studies, and research he published throughout his life. Given the undiagnosed ill-health he suffered with for most of his life, this makes his body of work all the more remarkable. Over 40 medical conditions have been suggested as the reason for his ill-health, but none have received widespread acceptance. Although one 2015 study suggests that Darwin was suffering from lactose intolerance (a condition that has contributed to our own understanding of natural selection).

Featured image credit: Finches by nuzree. CC0 public domain via Pixabay .

The post Darwin Day 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

Who keeps the dog in a divorce?

In the 1937 film The Awful Truth, Irene Dunne and Cary Grant are getting divorced and arguing over Mr Smith, their terrier. ‘Custody of the dog will depend on his own desires’ says the judge. ‘Send for the dog!’ Put in the middle of the courtroom, the dog eventually runs to Dunne – who has snuck a dog toy up her sleeve.

Who gets the dog (or cat, rabbit, etc.) on divorce is an issue I get asked about frequently by students and, in my past life as a divorce solicitor, by clients. A 2011 survey by the Co-operative Bank found that 20 percent of separating couples who had pets had sought legal advice about them.

For unmarried couples, the welfare of the pet and the love of the parties involved are not factored into the situation: it’s simply about who owns the pet. In England, pets are property – they’re chattels rather like the dining room table or – as we shall see below – a butter knife. Of course, ownership isn’t always easy to ascertain. People get pets through purchase, gift, adoption, inheritance – and sometimes the pet chooses them rather than the other way round. One person in a couple may pay for the pet food and vets’ fees while the other paid the breeder.

If the couple is married, the court has the power on divorce to transfer ownership of the pet to the other party as a type of property adjustment order. In fact, I once conducted a divorce case on which there was a clean break financial settlement on everything but who got the dogs. There are, however, no specific legal principles to guide court decisions on this issue apart from the general judicial obligation under the Matrimonial Causes Act to be fair. A number of academics have suggested ways in which principles relating to children could be applied to pets.

While we know about some celebrity pet disputes courtesy of the tabloids, there don’t seem to be any reported English or Welsh judgments we can analyse. Anecdotally, there seems to be some evidence that judges are seeking to find a way forward that gives both parties time with the pet, but it’s not clear whether this is based on a finding of joint ownership or whether judges are using principles that are similar to the way in which we decide where a child should live and when they should see the other person. What we do know is that such disputes can be extremely expensive. Reality TV contestants Alex Sibley and Melanie Hill reportedly spent £25,000 arguing over their rescue Staffordshire bull terrier and that is a drop in the ocean compared to some U.S. cases. Some couples have turned to drafting ‘pet nups’ – agreements about who gets the pet if the relationship breaks down.

There is now a body of case law from the United States and other countries giving principles on how to decide the issue. This not a universal trend, however. Despite the wife in one Canadian case alleging that her husband should not get the dog because he was ‘a cat person’, The Guardian reports that the judge declined to get involved. Dogs are different to children, he said, noting that:

“In Canada, we tend not to purchase our children from breeders. In turn, we tend not to breed our children with other humans to ensure good bloodlines, nor do we charge for such services. … When our children act improperly, even seriously and violently so, we generally do not muzzle them or even put them to death for repeated transgressions.“

Instead, he saw the dogs as no different to any other kind of chattel.

“Am I to make an order that one party have interim possession of (for example) the family butter knives but, due to a deep attachment to both butter and those knives, order that the other party have limited access to those knives for 1.5 hours per week to butter his or her toast?” Justice Danyliuk wrote. “A somewhat ridiculous example, to be sure, but one that is raised in response to what I see as a somewhat ridiculous application.”

Feature image credit: Dog pet cute by Staffordgreen0. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Who keeps the dog in a divorce? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 11, 2018

Beware the thesaurus

Someone recently asked me if I knew another word for entertaining.

“What’s the context?” I replied, wondering if the writer was looking for an adjective like enjoyable or interesting or a gerund like wining and dining or possibly even a verb like pondering. “Use it in a sentence.”

“Never mind,” she said, “I’ll just use the thesaurus button.”

The what?

I was familiar with a lot of word processing features—the phonetic symbols, page breaks, strikethroughs, track changes and comment balloons, but the presence of a thesaurus had slipped by me. I was aghast.

I’m not a fan of using thesauri when writing (though I rather like the word, especially in its Latin plural). The word itself seems to have been a Latin borrowing of a Greek term for treasury and was used originally to refer to all sorts of books of knowledge. That was before Peter Mark Roget published his 1852 Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases, Classified and Arranged so as to Facilitate the Expression of Ideas, which we know today as Roget’s Thesaurus. Dr. Roget, an English physician, had intended the work to be a classification of knowledge along the lines of Carl Linnaeus’s zoological taxonomy. He offered 1,000 concepts divided into a six super categories: Abstract Relations, Space, Matter, Intellect, Volition, Affections. Roget’s work was an instant success and evolved over the years into its present incarnation as a dictionary of synonyms.

That’s where I have a problem. I’ve got nothing against taxonomies of concepts, and works like the Oxford English Dictionary’s Historical Thesaurus, for example, are terrific research tools. They let scholars and students and writers research the words used for concepts at different times in order to trace the evolution of vocabulary or just find the right period term.

My frustration with thesauri is when they are used as shortcuts for thinking about words. When that happens, writers can trip themselves up with not-quite synonyms. Consider the word incarnation that I used earlier to refer to the “present incarnation” of Roget’s work. A thesaurus will suggest materialization, manifestation, avatar, or embodiment, none of which quite work. I once made this mistake as a student, writing about “another avatar” of a particular theory. Oops.

Another problem with thesauri is that writers sometimes use them not just to vary their vocabularies but to dress them up too much. Imagine the writer who takes a simple sentence like “The word itself seems to have been a Latin borrowing of a Greek term for treasury and was used originally to refer to all sorts of books of knowledge” and renders it as “The aforementioned expression appears to have existed as a Latin appropriation of Greek nomenclature for cache of riches and was employed formerly to denote any of a multitude of tomes of erudition.” Such a clunky rewording clogs the readers’ brain and makes the writer seem to be trying much too hard to impress with diction rather than ideas.

And perhaps writers should be asking whether repetition of words is always something to be avoided. Controlled repetition can actually be a way to keep the reader’s eye on the conceptual ball, as in this paragraph, from Joseph Williams and Rosemary Hake’s classic article “Style and Its Consequences”:

This is not the place, of course, to speculate in detail about the local and immediate causes of our every stylistic infelicity, much less suggest ways to correct them. But in whatever personal motives they immediately originate—insecurity, an ignorance of how to write any better, or a misguided belief that this heavily nominal style is the only style appropriate to significant subjects…

If we replace the second and third occurrences of style with other words, we run the risk of confusing the reader:

This is not the place, of course, to speculate in detail about the local and immediate causes of our every stylistic infelicity, much less suggest ways to correct them. But in whatever personal motives they immediately originate—insecurity, an ignorance of how to write any better, or a misguided belief that this heavily nominal patterning is the only design appropriate to significant subjects…

Are we talking about one thing (style) or several (style, design, and patterning)?

As writers, we need to worry about words. But we should put our worries about repetition in the context of the rhetorical purpose of exposition. Controlled, intentional repetition can make a topic pop out and stick with the reader. Worrying too much about varying our words can make us appear pretentious (or showy, ostentatious, affected, exaggerated or highfalutin).

Featured image: “Dictionary” by greeblie. CC by 2.0 via Flickr

The post Beware the thesaurus appeared first on OUPblog.

How and why to study folk epistemology

Folk epistemology may be roughly characterized as the (mostly tacit) principles, presuppositions, and principles that involve epistemological notions such as knowledge, evidence, justification etc. Folk epistemological notions have not been as empirically well-studied as folk psychological notions such as belief, desire, and intention. Consequently, epistemologists and psychologists have until recently worked in relative isolation. As explained in On Folk Epistemology: How we think and talk about knowledge, the rapidly changing dynamic of the study has raised methodological questions.

Just as our folk psychological judgments may be biased, so may our folk epistemological judgments: Since humans have limited cognitive capacity, we rely heavily on heuristics–cognitive shortcuts by which we form intuitive judgments on the fly. Such heuristics are generally useful because they are cost-effective and reasonably accurate. But they are associated with biases–roughly, systematic patterns of error. Heuristics and their associated biases are ubiquitous in human cognition. So, we should expect that our folk epistemological intuitions are also driven by heuristics and, therefore, biased.

To make this abstract point more concrete, consider an example: Assume that Kim pours herself a glass of water and leaves the room to fetch a book. When she returns, she clearly sees the glass of water on the table. Now consider the knowledge ascription:

A: Kim knows that there is water in the glass.

Fairly plausible, right? But consider now the same situation and the following knowledge ascription:

B: Although she cannot rule out that her husband substituted the water with gin, Kim knows there is water in the glass.

If you find it less natural to ascribe knowledge to Kim in case B, you are not alone. Empirical evidence indicates that when an error-possibility (the gin scenario) is made salient, we are inclined to deny that someone knows. This effect is called “the salient alternatives effect on knowledge ascriptions.”

As you can imagine, philosophers disagree about the salient alternatives effect. But many epistemologists hold the following view: Kim knows that there is water in the glass in both cases, and the fact that an unlikely error-possibility is mentioned in Case B does not alter this. But this philosophical account raises a puzzle: Why does it seem so unnatural to judge what Kim knows in Case B? This needs explaining. In On Folk Epistemology, I argue that epistemologists may draw on cognitive psychology to provide an explanation in terms of a cognitive bias.

Specifically, I argue that a focal bias is to blame. Very roughly, this is the phenomenon that when an error-possibility is made salient, we automatically process it as if it is relevant to knowledge–even when it is not. If the focal bias hypothesis is right, it has important social ramifications. For example, whether we regard someone as a knower has very significant bearings on how we will treat her. However, from a methodological point of view, philosophers who invoke biases to account for a pattern of folk epistemological judgments must ensure that the account aligns with what we know empirically of such biases. So, unsurprisingly, a philosophical account of our folk epistemology stands in need of empirical input.

Some philosophy-hating philosophers argue that philosophy should be entirely replaced by cognitive psychology. In contrast, I argue that a fruitful empirical study of folk epistemology requires epistemological theorizing. Let me try to briefly illustrate one reason why: In classic studies of the heuristics and bias literature, the researchers invoke a “gold standard” answer which often represents a rule of logic or probability theory. If the study participants systematically violate the rule, a bias is a candidate explanation. But similarly, a folk epistemological bias may only be postulated if there is a good theoretical reason to think that the participants’ judgments are mistaken. So, without some theoretical grasp of what knowledge is, it is hard to assess empirical findings.

Of course, “gold standard” epistemological principles are hard to come by. But one of my aims in On Folk Epistemology is to argue that epistemology may nevertheless provide epistemological principles that are relevant for interpreting folk epistemological judgments. Even though such epistemological principles are debatable and in principle revisable, they may provide a motivation for investigating whether a certain pattern of folk epistemological judgments is exemplifying a bias.

Consequently, folk epistemological biases are discovered by a complex interplay between our best epistemological theories, our folk epistemological intuitions, and what we know empirically about the psychology underlying such intuitions. However, biased folk epistemological judgments impact our life. They can get people fired, hired, silenced, or selected. They may even get presidents elected. So, we should embrace the interdisciplinary work required to identify our folk epistemological biases. Fortunately, the area is blossoming with fascinating research by empirically-informed philosophers and philosophically-inclined psychologists. Indeed, it is fair to say that a new and exciting interdisciplinary research field is emerging: the study of folk epistemology.

Image of Scotland 6 by Mikkel Gerken. Used with permission.

The post How and why to study folk epistemology appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers