Oxford University Press's Blog, page 285

January 5, 2018

Putin and patriotism: national pride after the fall of the Soviet Union [excerpt]

Following the fall of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Putin undertook the formidable task of uniting a restless and disorganized Russia. Throughout the early 1990s, the national narrative behind USSR’s regime remained unclear—causing national pride to deteriorate in the confusion. In the following excerpt from The Long Hangover, journalist Shaun Walker sheds light on how Putin used Russia’s victory in World War II to reestablish patriotism within the new Russia.

The fifteen nations to emerge from the Soviet collapse all took different approaches to dealing with their pasts as they built new national identities. In the three Baltic states, where Soviet rule had been imposed only in 1940, and large swathes of the populations had always been strongly antipathetic to rule from Moscow, new governments worked feverishly to undo the Soviet legacy. Museums opened that equated the Soviet period with the Nazi occupation. The old KGB archives were opened, and monuments erected to the victims of the occupying regime. The national narratives saw 1991 as an unequivocally celebratory date: the end of oppression, the restoration of a past, interrupted independence, and a return to the European family.

The only two of the fifteen countries not to come up with a coherent, unifying national- historical narrative in the first two decades after the collapse were Russia and Ukraine. The events of 2014— the revolution in Kiev, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and the war in eastern Ukraine— were, at least in part, a clash between competing Russian and Ukrainian attempts to transcend the conundrum of 1991 and mint new national identities.

By the time Putin took over, Russian attitudes to the Soviet past were ambivalent and confused. Back in 1991, crowds in Moscow had toppled the monument to Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder of the Cheka (the Bolshevik secret police that would later be called the NKVD and then the KGB), which stood outside the Lubyanka, the KGB headquarters in central Moscow. Leningrad reverted to its imperial name, St Petersburg. But after this initial flurry of activity, the disposal of the iconography of the Soviet past came to a halt. Most cities still had a Lenin striking a stirring pose in their main squares; many streets retained their Soviet names. There were Lenin, Marx, Komsomol, Red Partisan, and Dictatorship of the Proletariat streets across the country. Russia was like a party host who awoke the morning after, started making a cursory effort to clean up the mess all around, but after a while simply gave up and slunk back to bed to nurse its hangover.

“Russia was like a party host who awoke the morning after, started making a cursory effort to clean up the mess all around, but after a while simply gave up and slunk back to bed to nurse its hangover.”

The visual representation of history was dizzying and disorientating. Lenin’s mummified corpse remained on display in a glass case inside his marble mausoleum; stern soldiers watched over visitors to ensure they treated the embalmed Soviet leader with respect (no talking, no hands in pockets). Meanwhile, on the other side of Red Square, the new rich dropped obscene amounts of money in the upmarket boutiques of a flashy department store. The last tsar and his family were made saints by the Russian Orthodox Church, and yet a Moscow metro station still bore the name of Pyotr Voikov, the man who was directly responsible for organizing their execution.

Hammer and sickle motifs adorned dozens of government buildings; sumptuous mosaics of happy collectivized peasants and stoical workers lit up metro stations. Looked at through contemporary eyes, it was hard to say if they should be taken merely as culturally valuable artefacts of a bygone age, or if they still celebrated the achievements for which they had initially been designed.

The Moscow of the early 2000s was a palimpsest; the monumental buildings and heroic archetypes of the Soviet past were still visible beneath the tacky veneer of modern construction and the gaudy capitalist hoardings advertising casinos, loans, and burgers.

The new president’s nation- building task was unusually thorny, as he inherited a multi- ethnic, post- imperial state with a recent history that was as bewildering as it was painful. Putin took a selective approach to the Soviet past, picking out individual elements that could help provide a sense of continuity, starting with the old Soviet national anthem, which was restored in 2001, albeit with new lyrics. But simply creating a Soviet Union 2.0 was not going to work. While there was much nostalgia for the Soviet period, calling for its return would alienate the business community and younger Russians, who enjoyed the opportunities that capitalism and Putin’s oil wealth had brought them. Putin tapped into the sense of injustice among many Russians, famously calling the Soviet collapse the ‘greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century’. But he also equivocated, saying that while only a person without a heart could fail to miss the Soviet Union, only someone with no head would want to restore it.

In the new Russia, the old Soviet pantheon of revolutionary heroes and dates was no longer applicable, and it was not clear from where new ones might emerge. The Orthodox Church could help provide some kind of moral code and a new sense of purpose for a portion of Russians freed from the confines of official Soviet atheism. Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, blown up under Stalin in 1931 and later replaced with a swimming pool, was rebuilt during the 1990s and reopened during the first year of Putin’s rule. The Church became an important part of Putin’s identity project for modern Russia, but it could not alone unify the nation, especially in a country with large Muslim and smaller Buddhist regions.

“Only a person without a heart could fail to miss the Soviet Union, only someone with no head would want to restore it.”

Putin enjoyed reading history books and came across many figures in the tsarist past whom he admired, mainly those who had strengthened the state and ensured political continuity. At different times he would reference various statesmen and thinkers as inspirations, and draw from both the tsarist and Soviet periods. But in all of Russia’s long and complicated history, there was only one event that had the narrative potential to unite the country and serve as a foundation stone for the new nation, something that could help to foster a sense of national pride, just as the oil revenues led to improved economic indicators. That was the victory in the Second World War, or in the Soviet parlance that was still used in modern Russia, the Great Patriotic War.

Pride in the defeat of Nazism transcended political allegiance, generation, or economic status, and had been used by the later Soviet leaders to cement the regime’s legitimacy. Putin would once again draw on the war victory as the key to creating a consolidated, patriotic country. Only as this kind of country could Russia regain its rightful place as a first- tier nation, Putin felt, and as the years of his rule over Russia continued, the role of the war victory in official rhetoric grew steadily. The answer to the implosion of 1991, it turned out, was the triumph of 1945. The ideology of victory would become the touchstone of Putin’s regime: an anchor of national legitimacy in an ocean of historical uncertainty.

Featured image credit: “Flag (4770416043)” by Roman Harak. CC BY-SA 2.0 via

Wikimedia Commons.

The post Putin and patriotism: national pride after the fall of the Soviet Union [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Drive-through healthcare: Is retail thinking what patients want?

Retail thinking is spreading quickly in health care. It promises greater convenience and speed for delivering basic health care services — but it isn’t what patients really want.

Retail thinking views patients as consumers: faceless targets for buying services and products that aren’t always health-related. It’s the thinking behind technology-assisted health care services, like ZocDoc, Amwell, and One Medical, which quickly triage symptoms or serve up medical advice. It’s the thinking that makes it possible for me to walk in, no appointment needed, to a retail chain pharmacy to have a cough or sore throat examined.

At the same time, it gives web-based apps opportunities to sell some of your information to advertisers, who want to sell you other things. It gives brick-and-mortar organizations cross-selling opportunities for everything from allergy medications to Halloween candy as I walk down the store aisle to get my flu shot from the pharmacist or have the nurse practitioner apply guideline-driven diagnosis and treatment. The providers I see during these interactions know nothing about me, offer little tailored advice, and the services they provide will be both limited and standardized in how they are delivered.

Being viewed through the retail lens also means that I am asked to consume other offerings pitched to me by whoever provides me with health care, be it my insurance company or my employer. They do this to help them earn more of my loyalty, generate more revenue for themselves, or reduce their costs. The hospitals and medical offices I visit seek to keep me within their system of care delivery, make me a long-term customer, and refer me only to their providers and services, both of which they control.

Retail thinking has its place in health care today because there are some services and products that people need quickly and which do not require a personal touch. Such services might be low-level acute care (think strep throat), flu shots and immunizations, and some forms of simple chronic disease management, such as blood sugar checks or foot and eye exams for people with diabetes. There’s no question that retail thinking can also create purchasing opportunities for things patients find useful, if not always essential, and perhaps do so in ways that are cost-effective or convenient for us.

Holding by Matheus Ferrero. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

Holding by Matheus Ferrero. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.I interviewed 80 patients and doctors in order to better understand the doctor-patient relationship in the era of efficiency-driven innovation, corporate care, and retail medicine. Neither group with whom I spoke wanted transactional care at the expense of relational care. Sustained personal experience between two people who know something about each other, and who are motivated to really talk and listen as care partners, is something retail thinking does not do well.

Yet existing research demonstrates that these are the very features that are good for patients. For example, care continuity through a stable doctor-patient relationship improves health care quality and patient satisfaction. Doctor-patient trust, established through extended interpersonal contact, helps patients become more engaged in their care and creates a positive patient experience. Extended dialogue between patient and doctor positively affects health outcomes ranging from high blood pressure to mental health problems. Physician empathy is linked to more accurate diagnoses, better health outcomes, and an enhanced patient experience.

If you don’t believe the literature, just ask the patients I interviewed. Teddy, a healthy man in his 30s, believed that without feeling trust towards a specific doctor — which for him was forged over time through regular face time and conversations with that doctor — little could be uncovered of the more intimate, life story information that he felt was most important for keeping him healthy. He said he had never been completely honest with clinicians he didn’t know.

Can an industry that wants to use retail tactics also deliver on the relational excellence that patients and research say is important? It’s not easy, given retail thinking’s focus on speed and efficiency. Here are four ways that might meld these two approaches.

“Look for innovative ways to strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, not undermine it”

First, put more thought into where not to use retail thinking in health care. It may make sense for care delivery that is routine, care that can be standardized in a straightforward way, and in situations where the patient wants convenience above all else. But that actually amounts to a limited menu of services, and even routine care can often reveal deeper problems in patients, requiring the kinds of relational features I’ve described.

Second, better measure and monetize the components of relational excellence, making it matter to health care organizations and third-party payers. That means carefully assessing dynamics like interpersonal trust between doctor and patient; analyzing those data to see how they positively affect health outcomes; and then giving this metric the same relative importance in high-quality care delivery compared to other things like prescribing a particular drug for a particular condition.

Third, look for innovative ways to strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, not undermine it. For example, the industry should experiment with using technology as a tool to give doctors more face time and direct contact with their patients. Right now, both doctors and patients perceive technology, primarily the electronic health record, as interfering with their relationship.

Fourth, and most important, the patient voice must be heard. This could include adopting greater transparency with respect to assessing patient satisfaction with retail tactics, say through Yelp-type accountability mechanisms, and conducting market research that goes beyond simple binary questions of “would you use this” or “would you like greater convenience in accessing your care”.

In thinking about my discussions with patients, there is one other important thing they want. They want to decide when their health care should work like the drive-through at McDonald’s or buying with one click at Amazon and when it should be more personal than that, involving extended human-to-human interaction, highly trained experts who know their patients, and an abundance of the time, trust, and soft skills required to make us healthier long-term and see health care as the important part of our lives that it really is.

A version of this post was originally published on STAT.

Featured image credit: Drive Thru Neon Sign by gabriel12 via Shutterstock .

The post Drive-through healthcare: Is retail thinking what patients want? appeared first on OUPblog.

Why visit Vermeer?

An exhibition of paintings by Johannes Vermeer caused a frenzy in Washington DC in 1995. The National Gallery of Art was booked to capacity, and there were lines of hopeful visitors round the block, despite sub-zero conditions outside.

Vermeer has just returned to Washington, and the gallery staff expects a full house, but have things changed now? Why would you bother to go to a museum to see great art? With the tap of a finger, you can see masterpieces up close on your screen; you can get nearer than any museum attendant would ever allow.

In seventeenth-century Holland, public exhibitions of pictures were rare. People generally saw paintings in private collections, in artists’ studios, for sale at fairs, or sometimes as prizes in lotteries. They would be astonished to see the careful hanging conditions in today’s galleries: the spacious rooms, the special lighting, the deep colours on the wall, and the huge crush of people kept at a respectful distance.

Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting presents one of the world’s most famous painters in context amongst other artists of his day. But Vermeer himself never saw so many of his contemporary’s paintings together. He never saw so many of his own all at once, either. They were sold and left home. His pictures were made for individuals, who viewed them in darker, much smaller spaces. They may have been seen in daylight when the weather was good, but otherwise, they were appreciated in the dimness of a gloomy afternoon, or lit by candlelight, on a cold dark evening. Some would have been protected by a curtain or a box and maybe were only taken out to be enjoyed in private.

This personal quality endures in Vermeer’s pictures. There is something in them that encourages each viewer to feel that these paintings were made for them alone. We have to wonder then, what would propel anyone to come and see them amongst a crowd? What is it that cannot be conveyed in a poster or photograph?

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance c.1663-1664, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Public domain via Wikimedia.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance c.1663-1664, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Public domain via Wikimedia.Paintings say more to us in person than they ever can in reproduction. As we present ourselves to the canvas, so it presents itself to us. Its size relates to our size; we judge its scale; and we read it naturally, as we see it vertically in front of our eyes. We now understand how the artist moved his arm to work, how he moved towards his canvas and away; we see the change and direction of the brush and the texture and weight of the paint.

Vermeer may have borrowed themes from other painters. But his work is different. Unlike the others on show, his pictures blaze from the walls, as if lit internally. The subjects draw us in close and make us stand and look. Gradually, we become attuned and start to understand the rhythm of the image. We let our eye wander only where the artist allows: we stop where he stops; we move when he moves. We find and re-find the focus, and see the repetitions of shapes, and their perfect fit in the structure of the composition; see the slight shifts of hue, the depth of tone. We feel the light cool air of Delft stream in around us, feel the smoothness of pearl and pewter, feel the softness of feather, fur, and silk. We block out the hubbub around us and listen to the silence.

The women stand in radiant rooms, caught in moments of thought. Will they smile at us; will they speak? We wait to see, torn between disbelief at the illusion and a longing for it to be real. We stand a breathing space away from the place Vermeer stood when he created them.

We turn our face towards the light in the painted window and wait for the image to develop on our retina, wait for it to leave an indelible impression on our memory.

What do we hope for when we go to a gallery to see a painting by Vermeer?

We hope to make a connection with something that is greater than ourselves, with something that will outlast us. We want to have been close to genius.

Featured image: “ Seventeenth-century Dutch pigment pot and traditional hand-made brushes.” Collection Jane Jelley.

The post Why visit Vermeer? appeared first on OUPblog.

How many ‘Earths’? Rich findings in the hunt for planets of other stars

Ever since it was realised that the stars are other suns, people have wondered whether any of them are accompanied by planets, or ‘exoplanets’ as we now call them. Speculation along these lines were among the charges that led to Giordano Bruno being burned at the stake in the year 1600. It is only since the 1930s that astronomers seriously thought they had the observational tools to be able to find out. Exoplanets are almost impossible to see directly, because they are so close in the sky to a vastly brighter star, so the majority of the exoplanets that have now been catalogued are known only by indirect measurements.

The Dutch-American astronomer Peter van de Kamp (1901-1995) thought he had found at least one exoplanet, orbiting Barnard’s star just 5.9 light-years away, by measuring tiny changes in the star’s position in the sky – a technique known as astrometry. He attributed these to the gravitational effect of the star’s invisible planet, but other scientists were sceptical and the star’s apparent positional displacements were later shown to be artefacts caused by telescope modifications.

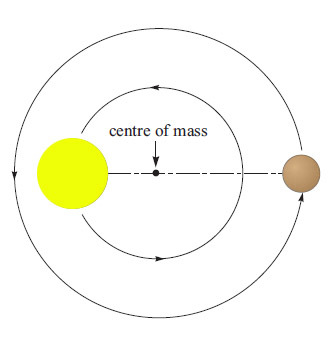

A planet and a star orbit around their common centre of mass. The star is much more massive than the planet, so its orbit (greatly exaggerated here) is only a tiny wobble. Image by David Rothery.

A planet and a star orbit around their common centre of mass. The star is much more massive than the planet, so its orbit (greatly exaggerated here) is only a tiny wobble. Image by David Rothery.It was not until 2010 that the first (and so far, the only) astrometric detection of an exoplanet was made, by which time other methods had become fruitful. Rather than measuring the star’s precise position by looking for side-to-side displacement while the planet orbits, it has proved easier to measure the associated changes in the star’s velocity as it is tugged towards and away from us. This is done by means of spectroscopy, using shifts in the star’s spectral lines to track its changing velocity. This is the ‘radial velocity method’, and works only if we are seeing the orbit at least partly ‘edge on’. It can also tell you the planet’s mass and its distance from its star.

There are surely more exoplanets than stars in the Galaxy.

In October 1995, two Swiss astronomers at Geneva Observatory, Michel Mayor (1942-) and Didier Queloz (1966-), announced the first successful use of the radial velocity method to find a planet in orbit around a Sun-like star (called 51 Pegasi). An initial trickle of discoveries swelled to a torrent, and by the end of 2017 over 3600 planets of other stars had been found – over 700 by the radial velocity method, and most of the rest by ‘transit photometry’, which detects the tiny dip in the star’s brightness when one of its planets passes in front of it. This happens only if the orbital plane happens to be nearly edge on to our line of sight, but ground-based and space-based telescopes are now automated to the extent that they can survey vast numbers of stars to detect and measure this phenomenon.

There are about a twenty billion Sun-like stars in our Galaxy, and although most are too distant for exoplanet detection, there are enough that are nearby which have now been surveyed for us to be certain that more than half of all stars must have planets. In a surprising twist, over the past three or four years we have discovered that among red dwarfs (low-mass stars that are fainter than the Sun, and which outnumber Sun-like stars by a factor of about ten) around 90% have planets.

Most of the first exoplanets to be discovered were giant, Jupiter-like planets. There was no surprise in this, because large and massive planets are the easiest to detect. What was surprising was that many of these are very close to their stars. These ‘hot jupiters’ probably formed further out before migrating inwards. However, exoplanets of Earth-size (and indeed smaller) are now beginning to be detected. There are several stars where as many as seven exoplanets have been documented and one, Kepler-90, where the tally was bumped up to eight (the same as in our own Solar System) by a discovery announced in December 2017.

Thus there are surely more exoplanets than stars in the Galaxy, and some of them (probably between 1% and 10%) will be at the right kind of distance from their star for the temperature to be suitable for at least simple life, such as microbes. This is amazing prospect. For me, the biggest question left to answer is, given the right conditions, how often does life actually get started on other planets? Unless life is an incredibly rare fluke, there ought to be life of some kind all over the Galaxy. We haven’t found signs of it yet, but are on the verge of being able to detect the effects of life on the atmosphere of an Earth-like exoplanet as it passes in front of its star. An exciting, though possibly tantalising, decade lies ahead, as we are still a long way from being able to go and take a closer look.

Featured image credit: sunrise space outer globe world by quimono. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post How many ‘Earths’? Rich findings in the hunt for planets of other stars appeared first on OUPblog.

January 4, 2018

Getting high on virtual reality

It’s a chilly November evening, but inside Apiary Studios in East London, things are heating up as the venue gradually fills with people. The atmosphere is electric; everyone is here for the Cyberdelics Incubator, an event aimed at showcasing the latest in psychedelic arts projects using immersive media and techno-wizardry. Through the course of the evening, eight speakers will showcase their projects, which are united by the use of immersive media as a tool for transforming conscious experience.

Following a tightly packed schedule, the speakers discuss psychedelic virtual reality (VR) experiences, augmented reality paintings, sound-to-light digital artworks, and more. For instance, the PsychFi collective situates VR booths at events such as the Liverpool International Festival of Psychedelia, eliciting hallucinatory experiences through digital media. Their Dionysia experience considers VR as analogous to an LSD trip; the user turns on, boots up, and jacks into a trippy alien world. Another project by Virtual Awakening called Death is only the Beginning takes a more radical approach, as the creators aim to simulate a near-death experience. Drawing upon Rick Strassman’s studies, which argued that reported experiences of tunnels of light were caused by endogenous DMT (dimethyltryptamine, a powerful hallucinogen), Death is only the Beginning aims to simulate a death-trip in order to make the user re-evaluate their life in positive ways. If this sounds a bit heavy, later on in the evening we also hear about choreographed drone-dances and Kerouac-style road-trips across America depicted in VR.

What unites these various projects is the idea of using the latest immersive technologies as tools for altering consciousness. This idea is not entirely new; the ‘expanded cinema’ movement of the 1960s and 1970s explored a similar idea using analogue audio-visual equipment. Indeed, the term ‘cyberdelic’, a portmanteau of cybernetics and psychedelics, was popularized in the techno-hippie cyberculture of the 1990s, as figures such as Timothy Leary claimed that computers would be to the nineties what LSD was to the sixties. Douglas Rushkoff’s classic book Cyberia (1994) explored this area, documenting the activities of the self-proclaimed ‘technoshamans’ such as RU Sirius, founder of Mondo 2000, the cyberpunk magazine par excellence in which one could find frenetic writings on everything from smart drugs, house music, and digital sampling; to VR, hyperlinks, and cybersex.

Lately, this whole area has been seeing something of a revival. Immersive arts seem to have come-of-age, as new holographic mixed-reality technologies tease at the possibility of bringing the futuristic worlds of science-fiction to life. The Cyberdelics Incubator is just the tip of the iceberg. In the past year, we have seen a growth in fulldome, a form of 360-degree cinema that is increasingly popping up at digital arts festivals. As showcased at FullDomeUK, fulldome productions such as Android Jones’ Samskara are explicitly psychedelic, taking the audience on hallucinatory voyages through immersive video. Elsewhere, video mapping has been transforming music festivals into synesthetic wonderlands. Over the summer I visited Mo:Dem in Croatia, a psytrance festival which delivers rolling waves of hypnotic electronic dance music to swathes of bronzed hippies. What stands out at Mo:Dem is not so much the music, but the huge, intricate video-mapped sculpture that looms above the dance floor like a crash-landed UFO. As day fades into night, this sculpture comes alive with pulsing neon lights and shamanic Amazonian patterns, becoming a shrine to the alien gods of psytrance.

So can you really get high on technology? The answer is yes, but not in exactly the same way that drugs or alcohol get you high.

So can you really get high on technology? The answer is yes, but not in exactly the same way that drugs or alcohol get you high. These are media-induced states of consciousness. Sound and music produce powerful emotional responses that set the pulse racing, while visual images that construct hallucinatory worlds that frame these with meaning. But hold on — couldn’t we argue that watching the latest Hollywood blockbuster does the same thing? What then, if anything, makes these ‘cyberdelic’ experiences unique? I shall venture a few things. First, the artists are seeking to emulate the form of hallucinatory experiences, and in doing so they offer explorations that might draw the nature of human consciousness into focus.

Second, by placing an emphasis on how media can affect us in potentially powerful ways, they might also cause us to re-evaluate the wider digital media-scape we exist within, and understand how this is affecting us. In a world where the emotional ‘hits’ we get from social media are increasingly monetized based on intelligent algorithms, such re-evaluations might be just what the doctor ordered. Not everything at the Cyberdelics Incubator hits the mark; some of the projects take a more ‘spiritual’ approach and make bold claims regarding the healing properties of their work that lack scientific support. Yet taken as a whole, these artists might be on to something. If the 1990s saw an optimism towards computers, the decades since have seen this fade as the darker side of internet technologies has reared its ugly head. A bit of idealism about how we can use media technologies in positive ways might not be such a bad thing — at the very least, if you get the chance to try out one of these immersive experiences, it will probably be worth ten minutes of your time to find out for yourself.

Featured image: “Mo:Dem festival, Croatia, 28th July 2017” by Jonathan Weinel. Image used with permission.

The post Getting high on virtual reality appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten steps to take when starting out in practice

Starting out in practice is challenging; especially if your training did not include much of an emphasis on practice development. Most training programs don’t as they have very tight curriculums and focus on teaching the core knowledge and skills needed to prepare one to be a competent and effective clinician. Leaving out the core business of practice skills needed to create a sustainable practice environment can make the transition into private practice quite challenging and anxiety provoking.

We share ten basic steps to take if you are thinking about getting into practice or have just begun. It doesn’t replace reading all you can and getting professional consultation, but it can help get you started.

Create your vision: Before doing a lot of planning and making major business decisions, create the vision for your practice. Why are you in practice? Go further than simply saying “to help people” or “to earn a living”. Those are outcomes that you are hoping to achieve. What is the deeper purpose? Being clear about this can help you align the many decisions ahead with your core vision.

Carefully choose your practice, clinical mentors, and consultants: Private practice is not a do-it-yourself venture. Even if you are going into solo practice, it is important to get input and support to avoid the many pitfalls that you may not even know exist. You can stumble through it, or you can respect the great investment you have made in time, energy, and money, and other sacrifices you have made, to be sure you have your advisors and their expertise and support in place to in order for you to make the most of your career. While many clinicians think of working with an accountant and an attorney, we often recommend seeking out mentors who can help you with clinical issues while also having a practice management consultant to help with set up, marketing, and operational issues.

Build your clinical expertise: Many mental health professionals are generalists. They don’t have unique skills compared to their colleagues, and are not seen as offering unique services in the community (or marketplace). Keeping in mind your vision, develop a niche as part of your practice and offer something that is new and of benefit to members of your community.

“Keeping in mind your vision, develop a niche as part of your practice and offer something that is new and of benefit to members of your community.”

Determine the structure of your practice: Are you going to go into solo practice? Are you going to have a partner or form a group practice? If so, be sure to specifically address such things as how decisions will be made (especially if you disagree), what your responsibilities will be, how each of you will be compensated, and even how you will terminate your relationship down the road if one of you desires to do so.

Develop a well thought out business plan: Decide on the specific strategies you’ll take to build a successful practice. How will you be different from the competition? What will your “brand” be? How will you market the practice and to whom? Also focus on how your practice will operate financially during the startup phase and beyond. How much greater will projected revenues be compared to your expenses based on how you are structuring your practice? Will that net provide enough compensation for you to make ends meet in your personal life? Do the math to make sure the decisions you are making also are sensible financially. Meeting your personal financial needs is crucial to building a sustainable practice.

Get it in writing: Whether you are signing a lease, setting up a partnership agreement, or renting equipment, be sure to have your agreements in writing. Be sure that you and your attorney read, fully understand, and agree to all the fine print in advance of signing the document. Contracts that are presented to you are generally not written to protect your interests. What you allege is said by a corporate representative (e.g., in provider relations at a managed care company) is not what will prevail if there is a written agreement that says something else.

Carefully plan your office administration policies and procedures: Be attentive to such things as how you will process new cases, how you will assure regulatory compliance, how you will track key business metrics, how will you make the administrative tasks run efficiently and in a cost-effective manner, and how you will protect against fraud and loss. Having written policies and procedures in place will be helpful both to prevent problems and to ensure you and others who work in your practice respond appropriately when difficulties arise over time.

Let’s shake on this by rawpixel.com. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

Let’s shake on this by rawpixel.com. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.Take your time: Practices grow like plants. They have different stages of development. Too often practice owners want to go too fast and make bold decisions in advance of being ready and in advance of having thought out the prerequisites for such a decision (as well as the pros and cons). The adage “first things first” certainly applies. For example, taking on associates before you have established a strong referral base can lead to major problems. Having unhappy associates because they don’t have enough work and aren’t making enough income can lead to turnover and a community image that you have an unstable practice. Similarly, not handling the flow of referrals because you don’t have an associate can lead to a sense that your practice is never available. Take the time and care needed to build a strong base to your practice before making decisions that you are not fully prepared to implement.

Prepare for things to change: As excited as you may be to start your practice, or to take it to the next level, always consider how you will shift from what you are planning to your next stage of development. Make sure you have an “exit strategy” to help you with the transitions that are down the road and out of sight. For example, how might you leave the practice if your life partner gets a different job in another state, or the practice partnership does not work out? Thinking this through at the start can help you structure your practice in a way that allows room for things to change.

Build your relationships: While most mental health clinical activities are done in private, your practice is both its own system and also part of the other systems in the community. What is your relationship with your community? Are you visible in your community, actively engaged in it, and do you regularly contribute to its welfare? Be attuned to how you are coming across to others and interacting with your colleagues. In essence you are always marketing, as virtually everyone you come in contact with can be a potential referral source when they are asked by a loved one or friend, “Do you know someone who is a good mental health professional?” Your relationships will be impacted by how you function in them, and so will your practice.

Featured image credit: Calculator by Alexander Stein. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Ten steps to take when starting out in practice appeared first on OUPblog.

National Trivia Day [quiz]

Each year, National Trivia Day is observed across the United States on 4 January. To celebrate, we cracked open books from our What Everyone Needs to Know series and pulled some facts. From facts about advertising to tidbits about the human brain, put your knowledge and trivia skills to the test by taking our quiz below!

Featured image credit: “Banner, Header, Question Mark” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post National Trivia Day [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The first “Citizen Enemy Combatants” and the war on terror today

The United States Department of Defense has acknowledged that it is holding a natural-born United States citizen in its custody in Iraq as an enemy combatant. The prisoner, who the government states were fighting for ISIS and turned himself over to United States allies in Syria, has now been in military custody for over three months. Meanwhile, the government has declined to reveal the prisoner’s identity and also denied his request to consult with a lawyer. Early in the fall, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a habeas petition on his behalf in federal court seeking to represent him. The court has yet to rule on the matter.

Against this backdrop, the Supreme Court’s fractured decision in the 2004 War on Terror case of Hamdi v. Rumsfeld has taken on renewed importance. Writing for a plurality of four Justices in Hamdi, Justice O’Connor concluded that “[t]here is no bar to this Nation’s holding one of its own citizens as an enemy combatant,” even in the absence of a suspension of habeas corpus. Many legal commentators point to this proposition as having settled the legality of the practice. Far from it.

To begin, the two concurring Justices who joined Justice O’Connor to make a Court in Hamdi, Souter, and Ginsburg, made clear that they did so without joining the full breadth of her conclusions. This kind of fractured opinion is a poster-child for precedent likely to be revisited by the Court in a future case.

There are also serious problems with the conclusions reached in Justice O’Connor’s opinion. To understand them, one must look back to study the first Americans who arguably could have been categorized as citizen enemy combatants — the American Rebels who waged war for their country’s very independence.

The story begins in 1775 when Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys stormed Montreal in a poorly-planned attempt to capture the city. The British quickly apprehended the group and put them on a ship bound for England. Then, after less than two weeks in England, Allen and the others were sent back to the American colonies. Why? Because, as the government surely knew, prominent attorneys with habeas expertise and ties to the American cause were preparing to file habeas petitions on their behalf.

Constitution of the United States (page 1) by Constitutional Convention. CC0 public domain via Wikimedia.

Constitution of the United States (page 1) by Constitutional Convention. CC0 public domain via Wikimedia.The British legal elite knew well that this posed a serious legal threat. This is because the English Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 promised to those who could claim its protections — citizens being at the top of the list — that the crown could not detain them outside the criminal process in the absence of a suspension of the Act. Notably, the Act applied to those suspected of treason and it contained no exceptions for wartime. Concerned that the Americans would claim to be British subjects and invoke the Act’s protections, the government turned to its longstanding practice of moving prisoners to avoid the reach of habeas courts. In Allen’s case, this meant dispatch back to the colonies, where the crown had long claimed that the Habeas Corpus Act did not apply.

As increasing numbers of American prisoners came to English shores, the government needed legal imprimatur for detaining them on English soil outside the criminal process. To this end, Parliament enacted a suspension. The government deemed such legislation necessary to detain Americans on English soil “like other prisoners of war.” Of the approximately 3,000 Americans subsequently detained in England during the war, no one was ever tried for treason or other crime. (Those imprisoned included the former president of the Continental Congress, Henry Laurens, and the cousin of Gouverneur Morris, who some six years later authored the United States Constitution’s habeas provision, known as the Suspension Clause.)

Accordingly, during the American Revolutionary War, where the Habeas Corpus Act applied and had not been properly suspended, it dictated that there could be no such thing as a “citizen enemy combatant.”

All too aware of how the suspension framework operated during this pivotal episode in American history and educated in William Blackstone’s glorification of the English Habeas Corpus Act as a “second Magna Carta,” those who wrote the United States Constitution imported that framework into the Suspension Clause, providing that the habeas privilege could only be suspended “when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” Indeed, in promoting the draft Constitution, Alexander Hamilton lauded the fact that the Constitution provides for “trial by jury in criminal cases, aided by the habeas corpus act.” And a few decades later, Chief Justice John Marshall declared that in interpreting the Suspension Clause, we must look to “that law which is in a considerable degree incorporated into our own” — specifically, “the celebrated habeas corpus act” of 1679. Even the “great Suspender,” President Abraham Lincoln, did not believe that he could detain Confederate soldiers and sympathizers outside the criminal process without a suspension.

To the extent that the English suspension framework proved the foundation for the Constitution’s Suspension Clause — and there is every reason to believe that it did — it is difficult to see how the law distinguishes between the situation posed in Hamdi and the plight of Ethan Allen in 1775. Accordingly, as things unfold, should the government continue to lay claim to the power to hold a United States citizen as an enemy combatant in the present case (and particularly if the government transfers the prisoner to American soil), it will need to confront the backdrop against which the Founding generation wrote the Constitution. Indeed, this history suggests that it is time to reconsider Hamdi v. Rumsfeld and with it, the very notion of a “citizen enemy combatant.”

Featured image credit: “US-supreme-court-building-2225766” by Mark Thomas. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay.

The post The first “Citizen Enemy Combatants” and the war on terror today appeared first on OUPblog.

January 3, 2018

First things first

I seldom, if ever, try to be “topical” (I mean the practice of word columnists to keep abreast of the times and discuss the words of the year or comment on some curious expression used by a famous personality), but the calendar has some power over me. The end of the year, the beginning of the year, the rite of spring, the harvest—those do not leave me indifferent. Last Wednesday, I wished our readers all the best in 2018. Now 2018 has come, with its rosy dreams and dark forebodings. This is the first post of the New Year, and I decided to return to one of my old topics and write a few lines about why the ordinal numeral of four is fourth, of ten is tenth, but of one…. Why not oneth? And two is coupled with second instead of the much more natural twoth.

In grammar, forms tend to form clusters in a rational way, for example, cat—cats, purr—purred, come—came. But sometimes this system breaks down, as in I—we, go—went, one—first, two—second. The forms that belong to the same paradigm but go back to different roots are called suppletive. The reason for their appearance is far from clear. See my post of 9 January 2013. (I have now reread it and discovered, as always, several new comments. May I repeat my usual request never to add comments to old posts? I have no chance to discover them. If you want to discuss an old post—and there are many of them: this is already No. 625—add your remarks under the latest one with an appropriate reference.)

It is not quite clear why, but all over the Indo-European world the words for first and second were not understood as belonging with one and two. The idea of “first” was expressed by an adjective meaning “the foremost one,” and of “second” by “the next one.” After that, counting went on without any trouble. Engl. three and third do not sound close enough, but the difference between them is due to their phonetic history and can be easily explained; the root is the same (r should have stood before the vowel, as in German dritte—this is a trivial case of metathesis).

Two’s company, three’s a crowd: the spirit of suppletion. Image credit: “Three’s a Crowd” by Rodney Campbell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Two’s company, three’s a crowd: the spirit of suppletion. Image credit: “Three’s a Crowd” by Rodney Campbell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.It is instructive to look at what happened to the designations of one ~ first and two ~ second in the Old Germanic languages, especially in the Western group, to which English belongs, and Gothic. The Old English for “one” was ān (reminder: ā stands for long a, that is, the vowel as in Modern Engl. spa; the so-called macron over a vowel indicates length). For “first” several old words have been recorded: forma, formesta ~ fyrmesta, fyresta, and æresta (æ was also long). Formesta ~ fyrmesta are the superlatives of forma, and we recognize Modern Engl. former and foremost in forma and formesta. The root of all them is fore-, as in Modern Engl. forefather. Today’s adjective foremost is really form-ost; it acquired its familiar pronunciation under the influence of most.

Æresta, too, has a recognizable root, even though today we need some effort to detect it in the archaic ere “before” (from ær), early, that is, ear-ly, and erst(while). (Isn’t it ridiculous that we spell ear–ly and er–st differently, though they have the same root and the same pronunciation? To be sure, ere and ear are also spelled differently, but they were also different a thousand years ago.) One views with a feeling akin to wonderment the efforts of the Anglo-Saxons to drive a wedge between “one” and “first.” In English, first eventually supplanted its competitors, the more so as not all of them occurred in the same dialects and at least some could have disappeared in peace. Alejandro Casona once (that is, long ago, in 1949) wrote a play titled Los árboles mueren de pie (“Trees Die Standing”). Words die in the same heroic way.

This is one of the most amusing books in English. Here is a good New-Year resolution: read it. The smart travelers have found a way to get rid of the suppletive forms. Image credit: Three Men in a Boat courtesy of Oxford University Press.

This is one of the most amusing books in English. Here is a good New-Year resolution: read it. The smart travelers have found a way to get rid of the suppletive forms. Image credit: Three Men in a Boat courtesy of Oxford University Press.The other languages offer no surprises. Old High German had ein “one” and ēristo ~ furisto “first.” It is only curious that the later norm chose first for English and erst– for German. But furisto did not quite drop out of German. We know it as the noun Fürst “prince.” Incidentally, prince traces to Latin princeps, and it is possible that Fürst came to mean what it does under the influence of the Latin word. Gothic was recorded in the fourth century; the pair we need sounded in it as ains ~ fruma. In Old English, fruma was a noun and meant “beginning, origin.” It had many cognates that do not interest us at the moment.

In Old Germanic, the first four numerals (one, two, three, and four) were declined and had different forms for the masculine, feminine, and neuter (naturally, two, three, and four only in the plural). The system has continued into Modern Icelandic. That is why foreigners trying to go shopping in Iceland and pretending to speak Icelandic are advised to buy five specimens of what they need, for they may not know the gender of the noun following the numeral of their choice. Providentially, the word for “five” is the same for all three genders. The same holds for the other numerals.

The Old English for “two” was twegen, pronounced as twayen (masc., of which the modern reflex is twain), and twā for the other two genders. Modern Engl. two is the continuation of twā. Their Old High German counterparts were zwene (m.), zwei (n.), and zwa ~ zwo (f.). Zwei is the modern form (the reflex of the neuter, as is Engl. two). Zwo also exists but has the status of a poor relative. I won’t discuss it here but will note why the neuter form prevailed in both languages.

It has been pointed out above that some numerals had three genders. No problem arose when people spoke about two, three, or four boys, bulls, etc., as opposed to the same number of girls and cows. The same usage determined the pronoun they. But in referring to mixed company (for instance, three men and two women or even many men and one woman) the Germanic speakers used the neuter (a most rational solution). The same rule prevailed for inanimate objects: the generalizing pronoun was the neuter. Consequently, the neuter plural had the best chance of survival.

A classical duel is unthinkable without seconds. Image credit: Sabre duel of German students of about 1900 by Georg Mühlberg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A classical duel is unthinkable without seconds. Image credit: Sabre duel of German students of about 1900 by Georg Mühlberg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The ordinal numeral for “second” had two forms in Old English: ōðer (read ð as th in this), easily recognizable as Modern Engl. other, and æftera (with long æ), more or less corresponding to the modern form after (-ter is the suffix of the comparative degree). It is curious to watch how language clings to its suppletive forms instead of making life easier. The Old English form was lost or rather superseded in the thirteenth century by its Old French synonym, and, as a result, we still have suppletion: two versus second. The story about how such a minute unit of time as one minute acquired its name and how its sixtieth part came to be called second deserves a special story.

Numerals are tough words for an etymologist. Those interested in the origin of six and hundred will find some musings on this subject in the posts for 12 and 19 July 2017.

Last week, I quite forgot about New-Year predictions. Here is one that will certainly warm the cockles of your heart in this cold weather. In 2018, the Oxford Etymologist will discover the origin of the word twaddle.

Featured image: While shopping in Iceland, buy five of everything if speaking Icelandic to avoid gender confusion. Image credit: “Little Shop on the Corner” by Les Williams. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post First things first appeared first on OUPblog.

Quotes of the year: 2017 [quiz]

2017 certainly was a year to remember – from Donald Trump being inaugurated as the 45th President of the United States of America, to the United Kingdom formally triggering Brexit with Article 50; from Britain releasing its first new pound coin in 30 years, to Facebook reaching two billion monthly users. Celebrities, politicians, and athletes were as vocal as ever last year when it came to current events, but do you know Theresa from Trump, or Putin from a pensioner? Which famous face tried to discourage middle-aged men from wearing Lycra, and who assumed their new role would be easier?

As we look back on last year, we’ve gathered a selection of some of 2017’s most memorable quotes to test your knowledge. Do you know who said what?

Featured image credit: “Quote” by Maialisa. CC0 Creative Commons via Pixabay .

The post Quotes of the year: 2017 [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers