Oxford University Press's Blog, page 284

January 23, 2018

Writing the first draft of history in the Middle Ages

There are times when history seems to be moving at an unusual speed, when one piece of remarkable news can hardly be apprehended before it is overtaken by another even more extraordinary. Such was the case at the end of the twelfth century and the start of the thirteenth when England was ruled by the Angevin dynasty—the era of Henry II and Thomas Becket, Richard the Lionheart and Eleanor of Aquitaine, of rebellions at home and crusade abroad. That we are able to appreciate this as a time of major incident and development is due not only to the events themselves, but to the fact that it coincided with a burst of creativity in historical writing; in writing the first draft of history chroniclers preserved a monument to those times, but also a record of how learned, curious, and politically engaged people at the time saw the world, and tried to understand the changes that were happening around them.

When Henry II became king of England in 1154 he ruled lands extending from the North Sea to the Pyrenees, thanks to his inheritance of Normandy and Anjou and his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. But historians took little interest in his early successes, and it was only when crisis began to follow upon crisis that they began, in great numbers, to write the history of his reign, and that of his successor Richard. First, in 1170, there was the shocking murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. Soon after, Eleanor and her sons leagued against the king, and although Henry crushed the rebellion, his son Richard would eventually wrest the crown from him in 1189. Then there was the series of events triggered by the Muslim leader Saladin’s capture of Jerusalem from the Christians in 1187, Richard’s expedition to the East, and his imprisonment and ransom on return. Meanwhile, England was shaken by anti-Jewish pogroms and the conspiracy of Richard’s brother John, who would eventually succeed him when the Lionheart was felled by an arrow just after ten years of rule. And throughout, there were incidents that seem less dramatic to us, but preoccupied people at the time—famines and floods, local disputes and personal rivalries—and also the fainter but yet perceptible signs of change in government, in intellectual life, and in relations between the English and their neighbours.

Contemporaries were aware that, for good or ill, these were remarkable times. In the 1190s William of Newburgh, a Yorkshire canon, explained that he had chosen to write a history of recent affairs in England because the events of his time were so great and memorable, and not to write about them would be a cause of shame to his generation. The royal courtier Walter Map declared that although every age despises its own modernity and harks back to an earlier age, the present times demanded writers to bear witness to them. His friend Gerald de Barri was so moved by the sequence of notable recent occurrences that he kept a list. It should be no surprise, then, that such a large number of writers should choose to write contemporary histories within the space of a few decades.

Illustration of Matthew Paris, historian (c.1200-1259) by the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of Matthew Paris, historian (c.1200-1259) by the British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Angevin England had the dramatic material of history, but it also had the right people to write it. Whereas England’s older religious houses had long dominated historical writing, a new kind of historian now emerged—closer to the centres of political power, with access to royal agents, senior ecclesiastics, and ample documentary evidence. The royal administrator Roger of Howden kept a diary of the king’s movements, and collected any useful records that he could lay his hands on, describing the noteworthy events of each year in exhaustive detail. Other writers took a more reflective approach, asking how the news—often puzzling and disturbing—might best be explained. They asked what it meant that a great king like Henry II should be brought low by his sons, and why God had allowed Jerusalem to be taken by the Muslims, and they answered with sophisticated interpretations, based on their extensive learning and their knowledge of earlier history. Nor did these writers concern themselves solely with matters of high politics: we are also presented with character sketches, tales of the supernatural, geographical descriptions, and discourses on everything from the eating habits of the people of Poitou to woodworm in ships’ hulls.

Though diverse in approach, the historians of Angevin England were united by a fascination with their own times, and an awareness of the importance in rendering them. Here we have a precious trove of information on a time of great incident. But, just as valuable, these contemporary witnesses give us a sense of what it was like to live through such a time, in all its exhilarating excitement and troubling uncertainty.

Featured image credit: Map of Britain by Matthew Paris, circa 1250. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Writing the first draft of history in the Middle Ages appeared first on OUPblog.

A few bad apples: Stalin, torture, and the Great Terror

Between the summer of 1937 and November 1938, the Stalinist regime arrested over 1.5 million people for “counterrevolutionary” and “anti-Soviet” activity and either summarily executed them or interned them in the Gulag. This was the period that has come to be known as the Great Terror. During this time, large waves of arrests targeted political, national, and social categories of the population as Stalin endeavored to be rid of a purported “Fifth Column” within the borders of the Soviet Union. The mass arrests of largely innocent people was accompanied by widespread torture as the security agencies (the NKVD) forced confessions, largely false, out of their victims.

On 10 January 1939, Stalin wrote that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had permitted the use of what was euphemistically called “the application of physical measures of persuasion” in interrogations from 1937. To date, there is no extant written order on the use of torture during the Great Terror. Stalin’s admission demonstrates conclusively that directives on torture came from the top. Stalin also asked in his 1939 note why the “socialist” security agency needed to be more “humanitarian” than “bourgeois” security agencies, which routinely used “physical measures of persuasion” on their enemies. Stalin’s admission therefore was not an apology for the atrocities of the “Great Terror,” but rather an attempt to prevent the total destruction of the NKVD in the “purge of the purgers” that followed the end of the terror.

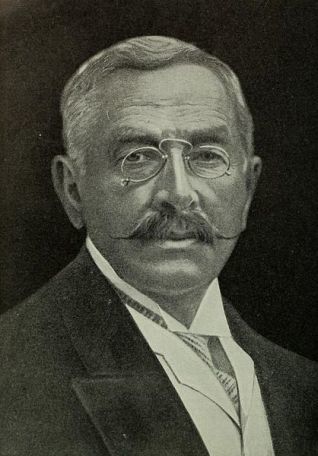

V.Ia. Grabar’, senior NKVD official in the Ukrainian republican NKVD. Image provided with exclusive permission of the State Branch Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine. Do not use without permission.

V.Ia. Grabar’, senior NKVD official in the Ukrainian republican NKVD. Image provided with exclusive permission of the State Branch Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine. Do not use without permission.Although historians had no access to Stalin’s 1939 note until the turn of this century, few doubted either the widespread use of torture on the victims of the Great Terror or Stalin’s leading role in this horrendous episode of mass repression. When, on 17 November 1938, Stalin called a halt to the mass operations, they came to a rapid, if grinding halt. Yet, at the 18th Communist Party Congress in 1941, Stalin would label this repression a “success” in creating a unified Soviet nation, stronger than ever before. At the same time, he admitted that there were individual “violations of socialist legality” in the NKVD’s conduct of the terror. Stalin charged the NKVD leadership at all regional levels for these violations, in the process destroying clientele networks within the organs as they were called, as well as serving up scapegoats for the worst of the terror operations.

Stalin’s scapegoating of NKVD interrogators and other officials removed the blame from him. It permitted him to explain away “violations” in policy implementation as the work of “a few bad apples.” It was a face-saving measure for Stalin, and not unlike similar practices used by other governments to avoid blame. The same bad-apples approach to punishment was apparent in the US government’s actions in My Lai during the Vietnam War and at Abu Ghraib during the Iraq war. This allowed Stalin to distance himself from the worst of the terror’s atrocities. It also served a symbolic purpose: Stalin cast the Communist Party as the main victim of the malfeasance of the NKVD in the Great Terror. Stalin’s bad apples approach allowed him to create a narrative that pitted the NKVD against the Communist Party, airbrushing away the majority of the terror’s victims, who were neither Communist nor elite, and, importantly, ignoring the central role of the leadership of the Party in the Great Terror. The purge of the purgers became Stalin’s gift to the Party, serving to re-legitimize its authority and its power following two years of terror. Khrushchev would use a similar narrative in his famed “secret speech” at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party in 1956, when, again, the Party would be portrayed (incorrectly) as the chief victim of the Great Terror, but this time placing Stalin (correctly) in the role of chief perpetrator and violator of “socialist legality.”

Featured image credit: “Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev, 1936.” Image scanned from: “Сталин. К шестидесятилетию со дня рождения.” Москва, Правда, 1940. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post A few bad apples: Stalin, torture, and the Great Terror appeared first on OUPblog.

Music and touch in Call Me By Your Name

A rich sensuality of touch permeates Luca Guadagnino’s new film , based on André Aciman’s 2007 novel of the same name. comes through not only in its evocative visual imagery: close-ups of hands and fingers and feet, shoulder rubs, sweaty bare skin glistening in the sun, bodies lounging on lush grass or jumping into chilly spring-fed ponds, soft-boiled eggs and ripe fruits bursting with juices, the broken limbs and pitted patina of ancient bronzes. Music also performs a crucial role in the movie’s simulations and stimulations of touch, heightening its visual vocabulary with a palpable tactility of sound, particularly that of the piano.

In a few scenes the prodigious Elio (Timothée Chalamet) plays the family’s Bösendorfer grand. This tactility through sound is especially clear in the scene of Elio playing the “Postillion’s Aria” from J. S. Bach’s Capriccio on the Departure of a Beloved Brother in the manner of Franz Liszt and Ferruccio Busoni. (Christoph Wolff suggests that Bach composed this suite as a farewell to a departing friend when he was only seventeen years old, the same age as Elio.) The original tune and the two arrangements allow Elio to touch the piano keys—and by extension to touch Oliver (Armie Hammer), who is standing directly in line with the keyboard in this frame—in a variety of expressive ways: delicately, cleverly, intently, forcefully, madly. The faces Elio makes as he plays comically mirror the gestures of his hand-crossings and emphatic octaves. Despite Oliver’s entreaties for Elio to play the version he had played on the guitar, Elio teasingly alters it in these different pianistic guises, emoting dramatically. After this passive-aggressive foreplay he finally offers the original tune, revealing his true feelings through the gentler sounds his touch produces.

When Elio plays Erik Satie’s Sonatine bureaucratique, his attitude at the piano suggests teenage insouciance, but Satie provides a running commentary in the score about a young bureaucrat’s dilemmas that ironically reflects Elio’s situation as well. According to Satie, “He is in love with a fair and most elegant lady,” but in the film we hear this music as Elio tries to ignore Oliver in the swimming pool and the camera shows us close-ups of Oliver’s swimming trunks hanging to dry in the bathtub, seemingly close enough for us to touch. Later Elio listens to the chorale “Zion hört die Wächter singen” from Bach’s cantata Wachet auf. The touch in Alessio Bax’s recording of Wilhelm Kempff’s piano transcription sounds confident and soothing, not the feelings Elio expresses in his diary about Oliver: “I was too harsh when I told him I thought he hated Bach.” This chorale celebrates the bridegroom’s arrival (“Zion hears the watchmen sing, her heart leaps for joy within her, she wakens and hastily arises”), but Elio worries about Oliver: “I thought you didn’t like me.” The musical touch contradicts the scene’s strained tension to heighten its pathos.

Timothée Chalamet as Elio and Armie Hammer as Oliver. Press photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics and Mongrel Media.

Timothée Chalamet as Elio and Armie Hammer as Oliver. Press photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics and Mongrel Media.More often there’s a symbiotic relationship between music and touch in the film. After Oliver playfully rubs Elio’s shoulder and bids him “Later!” as he bicycles away, we hear the staccato piano and pizzicato strings of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s “M.A.Y. in the Backyard” (1996) to lend a light-hearted and humorous mood to their initial interactions. Sakamoto’s “Germination” (1983) later provides the loud and percussive piano chords that punctuate Elio’s frustration with Oliver. The “brilliant, energetic, resonant” accents and interlocking two-piano rhythms of John Adams’ Hallelujah Junction (1996) evoke Elio’s confused desires, while the soft but urgent pulsations of Adams’ Phrygian Gates (1978) convey his longing to reach out to Oliver and resolve the tension between them. In the scene at the lake, the two touch the unattached arm of an ancient statue and use it to shake hands with each other. This action matches the physicality of this musical texture: the composer writes, “I treat each hand as if it were operating in a wave-like manner, generating patterns and figurations that operate in continuous harmony with the other hand.” Voluptuously rippling arpeggios in Maurice Ravel’s “Une barque sur l’océan” from Miroirs convey the sultry summer heat and the blossoming attraction between Elio and Oliver, especially in the remarkable single-shot scene at the monument where this piano music rises and fades as they draw towards and pull away from each other in a touching “dance of desire.”

A few soundtrack songs also describe a longing to touch, especially when the characters cannot find the words or the courage to do so themselves. “Lady Lady Lady” (from Flashdance, 1983) plays as Elio gazes at Oliver sensually slow-dancing with a girl; perhaps Elio wishes for Oliver to “feel love’s gravity that pulls you to my side, where you should always be,” to “Let me touch that part of you you want me to.” The three songs by Sufjan Stevens evoke a sense of tactility as well. “Futile Devices,” a remix replacing the original guitar with resonant piano strains, recalls how “when you play guitar I listen to the strings buzz” and “the metal vibrates underneath your fingers.” “Mystery of Love,” over plucked strings, describes the communicative power of touch over vision (“Oh, to see without my eyes”), its ability to bring comfort (“Hold your hands upon my head / Till I breathe my last breath”), or equally the pain of nostalgia (“Oh, woe is me / The first time that you touched me”). With the emotionally devastating final shot, Stevens’ “Visions of Gideon” begins with the resonant piano chords and pulsating repeated notes that recall other piano works by Ravel, Adams, and Sakamoto that have played previously in the film. He sings, “For the love, for laughter, I flew up to your arms,” capturing the connection between touching and feeling that this story portrays. When we hear “I have touched you for the last time” just as the closing title appears, we might never want that feeling to end.

Featured image credit: Armie Hammer as Oliver and Timothée Chalamet as Elio. Press photo © Sony Pictures Classics and Mongrel Media.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

January 22, 2018

Let’s talk about death: an opinions blog

Death and dying surrounds us, yet many of us see it as an uncomfortable taboo subject. As part of a series of articles on encouraging an open dialogue around death and dying, we asked various healthcare professionals, academics, and members of the public who have experienced palliative care the following question:

How important is it that we as a society are open to discussing death and dying?

‘It is never too soon in life to talk about death and dying: I have seen too many people regret the fact that they did not know the final wishes of a loved one – and I have also experienced the joy of attending a funeral that was a true reflection of a life lived… As a former Hospice Social Worker, but primarily as a human being, my advice would be:

For everyone’s sake – let the conversation begin!’

– Sue Taplin is a qualified social worker with a practice background in palliative care. She has held academic posts at the University of Nottingham, University of Suffolk and currently at Anglia Ruskin University, and has a Doctorate in Social Work from the University of East Anglia.

‘My mixed-race background has given me different perspectives when discussing death and dying. My Asian grandmother, totally dependent on her two sons, regularly has frank discussions about her end of life. I think these help not only her, but also close family in preparing themselves for the inevitable. Conversely, my English grandparents who live alone do not have the same level of openness about the topic with relatives, and consequently the future holds great fear of the unknown. To me, these personal examples highlight the importance of having these conversations.’

– Sian Warner is a Third-Year Medical Student at the University of Birmingham.

‘Death is certain. What is uncertain is when. So what do we do? Talking about death will help make the final stage of life as good as possible, instead of pretending it will never happen. So, advance care planning is a big part of the solution. All of us, including health and social care professionals, need to create opportunities for people to talk about the things that matters most to them, what they do and don’t want to happen. This will enable more people to live well until they die, allowing a good life to culminate in a good death.’

– Keri Thomas is the Founder and National Clinical Lead for the Gold Standards Framework Centre in End of Life Care in Shrewsbury. She is also the co-author of Advance Care Planning in End of Life Care, Second Edition (OUP, 2017).

‘I was given the news two years ago that I could not be cured of my cancer. I feel it is important to be able to openly discuss my fears and thoughts on dying. I feel that society as a whole has a taboo about the question of dying, and most people will side-step the issue when talking to me. Death is something we all face – rich and poor alike – and I think we can all do more to make the discussion more open and informative. I have found that Palliative Care is a refreshing format to further the discussion.’

– John Joyce is from Mayo, Ireland and has been fighting cancer for five years. John is a member of Voices 4 Care.

‘Palliative care should be available to anyone who needs it regardless of diagnosis or location of care. Talking about death and dying can be perceived as contentious with some suggesting that it can be distressing for people to think about their own mortality. However, recent research indicates that people appreciate the opportunity to talk about their preference for care at the end-of-life. Advance care planning provides people with the opportunity to think and talk about their wishes and provides healthcare professionals with the chance to ensure that these wishes, where possible, are met at the end-of-life.’

– Dr Julie Ling is the CEO of the European Association of Palliative Care.

‘Due to our ageing population, we can expect an increasing number of people dying in the next 25 years. Over half of these deaths will be people aged 85 years or over. It is important and timely for us to have a public debate on how we best prepare for this, to understand what aspects of care are important to people nearing the end of life, and where we should be directing investment to meet these growing needs.’

– The Palliative Care Research Society is a society dedicated to promoting research into all aspects of palliative care and to facilitating its dissemination.

‘It shouldn’t be, but it is the complete conversation stopper: “Have you thought how you would like to die?”

Death, dying, and passing on surrounds us on a daily basis in our neighbourhoods, on the television, and on social media, yet we never personalise it, never look at our own bodies and imagine them injured, ageing, or terminally ill. We never try to visualise our own non-existence and its effect on others – we shiver, shrug, and continue with our finite lives. “All living things have a designated lifespan – but not me!”’

– Elizabeth Fuller is a long-term volunteer at the Specialist Palliative Care Ward at Our Lady’s Hospice, Harold’s Cross, Dublin.

Just as life and birth is a common part of society, so too is death and dying. The celebration of life and birth promotes it as a shared experience. The birth process is very patient and family-centered with attention to social, cultural, and spiritual context. However, death and dying is not celebrated in this way and results in isolation, avoidance, and surprise. The result is many deaths are medicalized and are not guided by patient preference. Society needs to make death and dying more patient-centered.

– Constance Dahlin is the Director of Professional Practice for the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and a Palliative Nurse Practitioner at North Shore Medical Center in Salem, Massachusetts. She is a co-editor of Clinical Pocket Guide to Advanced Practice Palliative Nursing (OUP, 2017).

Featured image credit: ‘Red Cross Volunteers at work’ by Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Let’s talk about death: an opinions blog appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with Laura Knowles, marketing executive for online products

We caught up with Laura Knowles, who joined Oxford University Press in January 2017 and is now currently a Marketing Executive for the Global Online Products team. She talks to us about working on online products, her own experience in publishing, and her OUP journey so far.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started working at OUP in January 2017 as a Digital Marketing Coordinator with the UK Primary Education division. I then moved to Global Academic to work on online products in October 2017. It’s been great gaining insight and experience across different teams, and engaging with audiences worldwide.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

All the ducks! When you walk through the main entrance of OUP there is a fountain in the middle of the quad, home to lots of ducks and ducklings every year. When you look outside in summer, someone’s always on the grass trying their best to get a good picture of them. Once a group of ducks (a safe, ironically) trapped me, falling asleep around my bike—it took me ages to wake them up so I could move around them and go home.

Laura Knowles. Used with permission of the author.

Laura Knowles. Used with permission of the author.What was your first job in publishing?

I’ve worked with books and writers since finishing my MA, and I interned for around six months (five of which were spent sleeping on a friend’s sofa—thanks Sam!) before getting my first job in publishing. It was a London-based non-fiction publisher in their publicity team. It was a great experience and I was an ace with the franking machine.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Eleven from Stranger Things. A hardcore version of Matilda who can take on the Shadow Monster and rock a buzz cut? Yes.

What one resource would you recommend to someone trying to get into publishing?

An unlimited supply of patience. Also, Twitter. It’s really useful when looking for work experience or internship opportunities and for connecting with those who already work in the industry.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Psychology or social work.

What is your favourite word?

Flawless. It sounds great in every accent.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Run to the kitchen and make tea.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

I’ll make a cup of tea (notice a theme?) before heading off to a project meeting.

Bikes and ducks. Used with permission of the author.

Bikes and ducks. Used with permission of the author.Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

“New York magazine called it a ‘playful but mysterious little dish’ and I repeat this to Patricia, who lights a cigarette while ignoring my lit match, sulkily slumped in her seat, exhaling smoke directly into my face, occasionally shooting furious looks at me which I politely ignore, being the gentleman that I can be.”

– American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

What’s your favourite book?

Probably Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov. It’s a beautiful nightmare of a book that makes you empathise with one of the most depraved characters ever written. Everyone should read it. Everyone should also read Incarnations of Burned Children by David Foster Wallace—it’s a really great short story and I promise you won’t regret it. And while I’m at it (I work in publishing, I can’t just have one favourite), Atlantis by Mark Doty is all kinds of wonderful.

What is in your desk drawer?

A Skype headset and a multipack of Ripple chocolate bars. Don’t judge me.

Featured image credit: Oxford Street England by keem1201. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A Q&A with Laura Knowles, marketing executive for online products appeared first on OUPblog.

January 21, 2018

Are the gods indifferent?

It’s an old question, at least as old as Prometheus. Are the gods indifferent or is there something in the scheme of things that cares? The ancient tale of Prometheus neatly parses its reply – yes and no. Zeus is indifferent to humanity; we are small change. But not Prometheus. His concern for our plight leads him to give us fire, which as Aeschylus explains is more than the warming flames of the hearth. It is both science and technology, which moves us beyond victimhood and gives us agency.

Jump forward some 2,000 years to the middle decades of the 18th century. We find the same yes and no. On the one hand is Kant’s Universal Natural History, where he extends Newton’s Principia to explain the origins of our solar system. Any dispersed cloud of matter would collapse in on itself because of gravity. Any asymmetry would cause the condensing mass to spin about its center…spinning faster and faster as the cloud condenses until the force required to hold it together exceeds gravity. At that point some matter is spewed out, becoming the planets, the rest continued to collapse, making our sun.

On the other hand is the Comte de Buffon, who saw things differently but arrived at the same point. Long ago–Buffon would use rates of cooling to estimate some 75,000 years ago, far greater than a biblical 7,000 years–the sun was struck by a comet, the collision spewing forth the planets.

While both of these theories drew from Newton, they offered deeply different views of the workings of the universe. For Buffon the universe is Zeus-like, humanity and the solar system a matter of little consequence. The earth and its fellow planets were the debris of a cosmic accident. Across the vastness of space, imagined as a three-dimensional billiard table, one ball had careened into another. But Kant’s universe is Promethean. Not by mere accident, but by the very nature of things, a chaotic random concourse of matter achieves order. Matter, cold and indifferent to the needs of life, becomes the nurturing earth. Like the ancient myth, the Enlightenment, too, said both yes and no.

Our last item is a Cambridge tale. It begins with the Reverend Adam Sedgwick, Professor of Geology. A master scientist who forged a new way to structure the earth’s history, Sedgwick’s research led to geological systems, the chapters of the earth’s history such as the Cambrian and Devonian.

As president of the Geological Society, Sedgwick delivered an address in 1831 where he denied a central hypothesis of Cuvier’s influential work: that the signs of flooding scattered over much of the world are evidence of a single grand flood. Sedgwick explained this was not to deny Genesis, but instead to read it as a moral account. Just as one should not deny the truths within the story of Eve and the apple in the Garden of Eden because snakes don’t talk, nothing handed down in Noah’s tale justifies our looking for physical evidence of a great flood. Noah’s deluge is a moral, not a physical event.

Elsewhere, in his Discourse on the Studies of the University (1832), Sedgwick makes clear his Kantian leanings. Science and reason assure us the universe is designed with harmonies evident all around us. The Creator had taken great care in fashioning the universe.

As we chalk in Sedgwick as Promethean and Kant-like, we know there were Zeus and Buffon-like voices in the early Victorian era. Years later William Whewell would write to a friend, J.D. Forbes, how hard it was to maintain in 1864 what he had so confidently felt earlier about the harmony of a providential and a scientific history of the world. He acknowledges a reconciliation of science with the religion is still possible, but it is not so clear and striking as it used to be. And he touchingly adds “But it is weakness to regret this; and no doubt another generation will find some way of looking at the matter which will satisfy religious men.”

“It is both science and technology, which moves us beyond victimhood and gives us agency.”

Why, we may ask, had it become so hard to believe the gods are not indifferent? Darwin is one prominent reason. While the notion that life had evolved was not new in the 1859–several theories had been offered earlier in the century–Darwin had given it a new and far more compelling form. He had, in effect, shattered Buffon’s comet into countless shards of change, shards so small they approached Newton’s “fluxions.” They spewed forth across the generations of life in so many directions at once that one couldn’t speak of a goal so much as a random concourse.

Yet, while we may well imagine Buffon’s cynicism was such that he would have enjoyed the indifference of the gods and even more the discomfort of true believers, Darwin was no cynic. History has largely painted him as a ‘Darwinian’: Nature was red in tooth and claw, and marked by the indifference of the gods. But this is mistaken. There was a moral push to his work. He had uncovered a saving grace in life’s random coursing, one that placed sympathy for the plight of others deep within the human character. In short, Darwin believed evolution guaranteed that humans are innately good. Disraeli had put the question this way: are we descended from apes or angels? He was on the side of the angels. It turns out Darwin was as well.

And so the structure of things in Victorian Britain was not as indifferent as Zeus might have had it.

From Prometheus to Darwin’s Descent of Man, story-teller and scholar have sought to answer this most fundamental question on the indifference of the gods, and regularly whispered—both yes and no.

Featured image credit: Charles Robert Darwin Scientists 62911 by WikiImages. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Are the gods indifferent? appeared first on OUPblog.

Miscarriages of justice

Today we take it for granted that anyone convicted of a crime should be able to appeal to a higher court. However, this wasn’t always so. English lawyers traditionally set great store in the deterrent value of swift and final justice. Over the course of the nineteenth century, reformers pressed for the establishment of a court that could review sentencing and order retrials on points of law or new evidence. These advocates of change met with fierce resistance from the judiciary and much of the legal profession, and the cause of reform had little success until a spectacular miscarriage of justice came to light.

In 1877, a man named John Smith, who posed as an aristocrat named Lord Willoughby, was convicted of swindling London prostitutes and served five years in prison. Nearly two decades later, another group of women were tricked out of their valuables by a con man with much the same modus operandi, right down to the pseudonym (“Lord Winton de Willoughby”). The police closed in on another man, Adolf Beck, a Norwegian businessman living in London. The officer who arrested John Smith two decades earlier was certain that Smith and Beck were the same person. The victims insisted that the Norwegian was the man who had deceived them. Despite evidence that Beck had been in Peru in 1877 when Smith committed his crimes, Beck went to prison. Three years after his release, another string of identical crimes led to his second apprehension, trial, and conviction. It was at this point that he finally caught a break. While Beck was in prison awaiting sentencing, a man calling himself Captain Weis was arrested for con tricks from the same playbook. It became undeniable that Weis aka William Thomas, and not Adolf Beck, was John Smith.

Beck was granted a royal pardon and was offered £2000 in compensation. He held out for more, and eventually the government paid him £5000. His payout became a benchmark for the Home Office — the government department with oversight of criminal justice — as it arranged compensation for victims of later miscarriages of justice. Civil servants would compare each new case with exemplary ones like Beck’s, working out a ratio of time wrongly spent in prison to money paid out.

Image credit: Adolf Beck. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Adolf Beck. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The outcry over the Adolf Beck saga led to the founding of the Court of Criminal Appeal in 1907. The whole affair might have been prevented if Beck’s lawyers had been able to appeal the first trial judge’s decision to exclude evidence that would have proved that this was a case of mistaken identity. But the judges who sat on the new court were drawn from the same pool of judges who had opposed criminal appeals in the first place. They took a narrow view of the appeal court’s role. They scrutinized disparities in sentencing but they seldom overturned convictions, deferring to juries and trial judges.

This was what happened in the case of Rose Gooding, twice convicted of criminal libel and sent to prison for harassing her neighbours with obscene letters which she steadfastly insisted she had not written. When the clerk at the Court of Criminal Appeal read her file, he noted that there had been a suggestion that the writer of the letters had taken care to disguise the handwriting, and that the subject matter of some of the letters “was such as to cast suspicion on nobody except the appellant”. Nevertheless, he concluded: “It seemed to me a case for the Jury.” The judges agreed with him, and refused to entertain Rose Gooding’s appeal. When new evidence came to light that appeared to exonerate her — further offensive letters posted while she was in prison — the government began a complicated process of re-investigating the case and sending a prosecutor back to the Court of Criminal Appeal to disavow the convictions.

To call it a “re-investigation” might be going too far. The case against Rose Gooding had been a private prosecution. An aggrieved neighbour accused Gooding of writing the letters and complained to the police. They were unwilling to do more than have a stern word with Gooding and her husband, and the neighbour found the funds to bring a private prosecution. Rose Gooding was twice convicted on little more than the word of her accuser, and there was no police investigation to back up the prosecution’s case. A full investigation began only after Gooding’s appeal rights were exhausted and new evidence emerged. The houses of Gooding and her accuser were searched, and detectives discovered sheets of blotting paper, that staple of detective fiction, that ultimately led back to the libellous letters. The case against her began to unravel.

Featured image credit: Royal Courts of Justice, London by bortescristian. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Miscarriages of justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Jean-Jacques Rousseau [timeline]

This January, the OUP Philosophy team honors Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) as their Philosopher of the Month. Rousseau was a Swiss writer and philosopher, considered important for his contribution to modern European intellectual history and political philosophy. He is best known for Social Contract (1762) with its famous opening line: “Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains.”

Rousseau’s books attracted both admiration and hostility during his lifetime and exerted profound influence on French revolutionaries, his contemporaries, and later thinkers such as Kant, Hume, Wollstonecraft, Hegel, and Marx.

His contributions to political philosophy can be seen in various works such as Discourse on the Origins of Inequality (1755) and The Social Contract (1762). Rousseau’s central thinking in politics is that a state cannot be sovereign unless it is guided by the “general will,” or the collective will of its citizens, taken as a whole. The general will creates the law, promoting liberty and equality for citizens.

Another important doctrine of Rousseau was his belief that mankind was, by nature, good, but had become corrupted by society and civilisation. This thinking was evident in his first important work, A Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts (1750), which won the Dijon prize. Rousseau developed this idea further in the Second Discourse, also known as Discourse on the Origins of Inequality (1755): as society becomes more advanced, this gives way to a new type of self-interested love, amour proper (love of self/vanity), or the need to compete with each other for success and recognition.

“Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains.”

Rousseau also offered his theory on education, which is mainly explored in his novel Emile (1762). Education should be in line with Nature, meaning that education should be carried out in harmony with the development of the child’s capacities and natural goodness. This is opposed to the conventional model of education with the teacher as a figure of authority, conveying prescribed knowledge to a child. Some of Rousseau’s stages of education involve encouraging a child to find out about the world through discovery and practical experience. In this way, Rousseau believes a person can become an independent individual.

The publication of Social Contract and Emile, however, scandalised the French and Genevan authorities, with the result that Rousseau had to flee into Switzerland and England. Towards the later stage of his career, Rousseau composed more autobiographical works. Les Confessions (1764-1770), the first autobiography ever written in the history of literature deals with his childhood and adolescence, and his adventure as a young man, his career as a writer and living in exile. His last work, Reveries of the Solitary Walker (Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire, 1776-1778) which is a meditation on his life and philosophy, has become a seminal text on the development of Romantic sensibilities.

For more on Rousseau’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below.

Featured image credit: Les Charmettes. The House where Jean-Jacques Rousseau lived with Mme de Warens in 1735-6. Now a museum dedicated to Rousseau. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Jean-Jacques Rousseau [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

January 6, 2018

Emerging infectious diseases: Q&A with Michel A. Ibrahim

Defined as the branch of medicine that deals with the incidence, distribution, and possible control of diseases and other factors related to health, epidemiology is a wide-ranging field. Topics that fall under this umbrella range from incarceration and health (discussed in the upcoming 2018 issue) to environmental issues to gun violence.

In recent years, global outbreaks of infectious diseases such as Ebola and Zika have brought epidemiology to the forefront. Because of this, greater importance has been placed on research aimed at understanding both emerging infectious diseases (i.e., those that are newly identified and not know to previously infect humans) and reemerging infectious diseases (i.e., those that were previously identified and brought under control but have now begun to re-infect human populations).

To address this, Epidemiologic Reviews will be accepting review articles that fit the theme of its 2019 issue, “Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases.” We caught up with the current Editor-in-Chief, Michel A. Ibrahim, who kindly shared his thoughts on this theme, the field of epidemiology, and his experience with the Journal in the interview below.

What led you to your field of study?

I was interested in doing research on populations to gather the appropriate evidence for public-health practice and policy making. The field of epidemiology offered a great opportunity to do just that. What interested me in being editor of Epidemiologic Reviews is the Journal’s focus on systematic reviews, with or without meta-analyses, that provide the scientific basis for policy and practice.

What is the topic for the upcoming issue of Epidemiologic Reviews ?

Plans for volume 41, which will be published in 2019, are under way. Manuscripts that fit the theme of “Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases” are being solicited under the able editorship of David Celentano, our new Editor-in-Chief.

What led to the selection of this theme in particular?

We believe that the forthcoming theme represents an area of current interest. After consulting with colleagues and taking into account our familiarity with topics of concern, emerging and reemerging infectious diseases seemed to be the topic favored over all others.

Culex mosquitos (Culex quinquefasciatus shown) are biological vectors that transmit West Nile Virus. Photo by CDC/Jim Gathany (2003). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Culex mosquitos (Culex quinquefasciatus shown) are biological vectors that transmit West Nile Virus. Photo by CDC/Jim Gathany (2003). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.What is the most important issue in the field of infectious diseases today?

This question is, obviously, related to the previous one. In the past two decades, we have seen numerous outbreaks that have proven challenging to prevent and control. Outbreaks of SARS, chikungunya virus, West Nile virus, MERS, Ebola, and most recently Zika virus have arisen and waned. Other threats include pandemics of dengue fever, malaria, and diseases caused by diarrheal pathogens; in addition, some well-controlled communicable diseases such as measles are returning as childhood vaccines are being rejected by some parents, which places communities at risk.

What developments or findings would you like to see from this call for papers?

This issue will be a compilation of reviews that update and attempt to fill some of the evidence gaps in the epidemiologic literature on emerging and reemerging infectious diseases globally. The overall goal of the issue is to provide timely reviews about the current state of the evidence regarding infectious diseases, including information on new pathogens and issues confronted by health-care epidemiologists (e.g., antibiotic resistance, new control measures, problems encountered with medical devices).

What advice do you have for people interested in submitting to ER?

Read the call for papers and follow the instructions given, do an up-to-date and critical systematic review (and meta-analysis, when appropriate), and be explicit about the search method used.

Featured image credit: clinic-doctor-health-hospital by Pixabay. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post Emerging infectious diseases: Q&A with Michel A. Ibrahim appeared first on OUPblog.

Organisms as societies

In the 19th century, biologists came to appreciate for the first time the fundamentality of the cell to all life on Earth. One of the early pioneers of cell biology, Rudolf Virchow, realized that the discovery of this cell brought with it a new way of seeing the organism. In an 1859 essay he described the organism as a ‘cell state’, or Zellenstaat, a ”society of cells, a tiny, well-ordered state, with all of the accessories—high officials and underlings, servants and masters, the great and the small.” In the 20th century, the ‘cell state’ metaphor fell out of favour in biology, but three recent trends in biology suggest it is due a revival.

Firstly, there is our growing awareness of cooperation among microorganisms. Some social behaviours in microbes, such as the formation of fruiting bodies in social amoebas, result in phenomena that resemble simple multicellular organisms. Some authors have even suggested that bacterial biofilms should be regarded as organisms in their own right.

Secondly, in insect biology, there has been a revival of interest in the ‘superorganism’: the idea that we should think of an insect colony as a single organism. While this idea has always been controversial, even to consider it is to recognize the possibility that a high degree of social complexity can in principle give rise to a new, organism-like entity.

Finally, a research program called ‘major transition theory’ has led to a radical re-evaluation of the place of cooperation in the history of life. Building on foundations laid by Leo Buss, John Tyler Bonner, John Maynard Smith, and Eörs Szathmáry, major transitions researchers portray the history of life as a series of ‘evolutionary transitions in individuality’ in which integrated individuals have evolved, through social evolution, from groups of smaller entities.

When we look at evolution in this new light, we start to see social phenomena where we saw none before. We see cooperation among cells within multicellular organisms, among organelles within cells, even among genes within a chromosome. The result has been a dramatic increase in the ambitions of social evolution research—and the return of ‘cell state’ thinking.

Importantly, for social evolution theorists working on the origins of multicellular life, the ‘cell state’ is more than a metaphor. It’s the foundation for a research program. Taking a ‘social perspective’ on the organism does not simply mean describing the activities of cells in social terms. It means drawing on the concepts of social evolution theory to explain the origins of multicellular individuals.

Taking a ‘social perspective’ on the organism does not simply mean describing the activities of cells in social terms. It means drawing on the concepts of social evolution theory to explain the origins of multicellular individuals.

For one of the pioneers of major transition theory, Leo Buss, multicellular life presented the following puzzle: given that natural selection favours cells that promote their own reproduction, how did early multicellular organisms avoid being destabilized by conflict among cell lineages? His answer was that organisms have evolved, through group selection, mechanisms for controlling internal conflict, such as ‘germline segregation’, whereby the capacity to generate a new organism is limited to a very small number of cell lineages called the ‘germline’. This, however, led to a ‘chicken and egg’ puzzle. How could group selection be powerful enough to assemble such mechanisms prior to the existence of such mechanisms?

What Buss missed is that organisms are clonal groups—they are genetically identical—and the evolutionary interests of genetically identical individuals are perfectly aligned. This neutralizes the conflict. As W. D. Hamilton, creator of the theory of kin selection, observed in the 1960s:

“Our theory predicts for clones a complete absence of any form of competition which is not to the overall advantage and also the highest degree of mutual altruism. This is borne out well enough by the behavior of clones which make up the bodies of multicellular organisms.”

In other words, the cells of multicellular organisms cooperate because they are genetically identical. Let’s call this ‘Hamilton’s hypothesis.’

Hamilton’s hypothesis is complicated by the fact that few organisms are fully clonal. Clonality is a feature of organisms that develop from a single cell, but not all development is like this. For example, many plants can reproduce vegetatively, with the new individual developing from a multicellular offshoot.

In plants under cultivation, generations of vegetative reproduction lead to the accumulation of mutations in different cell layers, resulting in individuals containing internal genetic diversity. In the wild, however, plants frequently reproduce sexually, pushing their lineage through a single-cell bottleneck and restoring high relatedness. Provided this happens often enough, high genetic relatedness and low internal conflict can be maintained.

Even among organisms that pass through a single-cell bottleneck every generation, such as multicellular animals, clonality is not perfect. Within-organism genetic diversity can arise through ‘chimerism’, where cell lineages produced from a different sperm and egg mix in the early stages of development. We see this, for example, in marmosets.

Genetic diversity also arises through mutation. Sometimes, mutation events lead to cancer, and the survival of the population relies on these cancerous ‘cheater’ lineages being unable to spread between organisms. We see a grim illustration of this point in the Tasmanian devil, now threatened with extinction due to an epidemic of facial tumours. Given this, we should not be surprised to find that an ability to discriminate ‘self’ from ‘non-self’, and to attack intruding cell lineages, is present even in sponges, often regarded as among the most simple multicellular animals.

Yet for all these caveats, it remains plausible that, for any organism spawned from a single cell, genetic relatedness is high enough to stabilize cooperation among the cells. It’s also plausible that organisms which can reproduce vegetatively pass through a single-cell bottleneck often enough to maintain high relatedness. So it seems like Hamilton’s insight has stood the test of time—as has Virchow’s. The organism began as a cooperative enterprise between independently viable cells. Those cells cooperated—and, hundreds of millions of years later, still cooperate—because they are genetic relatives.

Featured image credit: Dictyostelium discoideum 43 by Usman Bashir. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Organisms as societies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers