Oxford University Press's Blog, page 287

December 28, 2017

A Q&A with the Editor of Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, Susan Easterbrooks

Susan Easterbrooks is Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. We sat down with Susan to discuss her background, the developments in deaf education, and the challenges scholars face in the field.

Can you tell us a little about your background?

Thank you for asking. I have worked in the field of Deafness for 45 years as a teacher, evaluator, administrator, author, and researcher. Recently I retired from my position as a Regents’ Professor at Georgia State University. It has been my privilege to have worked in 5 different states and at several universities, which has given me the benefit of seeing multiple perspectives and a variety of consumers.

How did you get involved with Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education ?

JDSDE has been the preeminent journal in my field since its inception 23 years ago. As a young professional, I read the journal and was thrilled to have my research accepted for publication. As with many professors, I took my turn as a reviewer, was then invited to be on the editorial review board, and after several years, was invited to be an Associate Editor. It was around this time that I chanced to meet the founding editor of the journal, Dr. Marc Marschark. The fields of deaf education and deaf studies are small but mighty fields and because we are so few yet so active, I already knew many of the other AEs either personally or professionally, and so when I was approached about considering the editorship, I felt honored to be able to provide this last service to my wonderful field and equally wonderful colleagues.

Susan Easterbrooks. Used with permission.

Susan Easterbrooks. Used with permission.How has the field changed in the last 20 years?

The field has changed dramatically in the last 20 years, yet in many ways it remains the same. We have benefitted from advancements in technology that have improved listening technology, from laws and policies that require early identification as well as intervention, and from the maturity within the broader human culture that reaches out to diverse individuals. Along with these improvements, the field also experiences challenges within the cultural context such as changing political landscapes and increasing challenges to funding sources. Regarding research, we are seeing a new, vibrant group of researchers who are picking up where we left off. I have the highest regard for all that has come before and great hope for all that will unfold in the future.

From your experience, what are the challenges that deaf education scholars face today?

As with many subject areas, we appear to be struggling with the gap left by the exit of the baby boomers from the field and the diminished number of mid-career professionals available to provide guidance to early-career researchers and authors. For this reason I am calling upon my recently-retired colleagues to offer their services to guide the generation of early career researchers in establishing their track records so they may continue to provide the field with excellent research.

What do you think the journal will look like in 10 years’ time?

Ah, so you are looking for the crystal ball answer? Well, let me consult my resources and see what the future holds. This is no easy task given the plethora of changes we are undergoing in response to governmental, environmental, social, and global forces. But my crystal ball reminds me that we have already seen an upswing in submissions from international contributors, and I hope to see this trend continue. We have done a great job in addressing many of the long-standing challenges, yet many remain and I hope to see us, as a field, address many of the problems that have appeared to be intractable. I have confidence that we will continue to make advances.

Featured image credit: classroom guiyang tables textbooks by weisanjiang. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post A Q&A with the Editor of Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, Susan Easterbrooks appeared first on OUPblog.

December 27, 2017

Etymology gleanings for December 2017

At the end of December, it is natural to look back at the year almost spent. Modern etymology is a slow-moving coach, and great events seldom happen in it. As far as I know, no new etymological dictionaries have appeared in 2017, but one new book has. It deals with the word kibosh, and I celebrated its appearance in the November “Gleanings.” I also want to tell our readers that after fifty-four years the great and magnificent Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) has closed shop in the direct sense or the word. It has been said that in the history of the English language three names stand out: the Bible (I think the King James Version is meant), Shakespeare, and the OED. Perhaps so. Views on American English have changed radically over the years. Not too long ago, it was understood as the language of hicks, unworthy of scholarly attention. But the prestige of a language depends on the prestige of its speakers, and together with the importance of the United States the importance and glamour of American English grew. Also, in the course of the last 150 years, the status of so-called Americanisms has been understood (most words labeled so turned out to be British provincialisms brought to the New World), while the media made many words coined on American soil known everywhere.

Dictionary of American Regional English is a treasure trove of local words and pronunciations. Many entries also contain hints of etymology. Numerous maps enhance its value. Thousands of volunteers traveled all over the country recording the answers of the natives. Countless books, journals, and newspapers were read in search of regional words. DARE’s model was to a certain extent Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary, another work of permanent value. The five volumes of DARE read like thrillers. For more than half a century, several agencies and an army of individual sponsors have made the work of this great national monument possible. Now DARE has run out of funding. There is money for a picture that costs half a billion and for rewarding the winners of bizarre lawsuits, but not for the work that will stand as a permanent monument to the language of the richest country of the world. Read DARE, read about DARE, admire it, and tell your friends about it. The history of DARE is being written. The history of Joseph Wright’s dictionary was written by his wife. Not every dictionary has a wife, but enthusiastic scholars have not yet died out.

Odds and ends

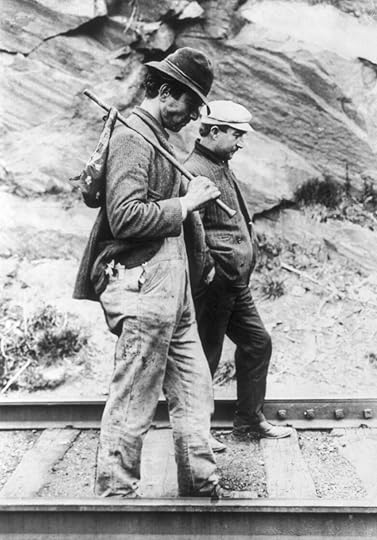

First an Americanism. Nowadays, I seldom receive regular mail (holiday greetings can be discounted), but several days ago a postcard came to my university address from a faraway city. The correspondent, a specialist in Japan, asked me what I thought about the Japanese etymology of the word hobo. Fortunately, I can direct him to my old post of 12 November 2008. In it he will find a great number of fanciful suggestions about the etymology of hobo but no solution. The Japanese hypothesis is also there.

A hobo: an Americanism. Image credit: Two hobos walking along railroad tracks, after being put off a train. One carries a bindle via The Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A hobo: an Americanism. Image credit: Two hobos walking along railroad tracks, after being put off a train. One carries a bindle via The Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Now the aftermath. Once I mentioned the fact that math in aftermath means “mowing.” A correspondent took my comment for a bad joke and even expressed satisfaction that The Oxford Etymologist sometimes stumbles. No, The Oxford Etymologist never stumbles: when he errs, he falls flat (full length) on his face. I have a pen friend, who writes me only when I say something wrong. I fear his emails, because he is always right. But as regards aftermath, I have nothing to apologize for. Aftermath is the second crop of grass. The word has been known from books since the early 1500s, and a century later it acquired its familiar figurative sense. The Old English for math was mæþ (with a long vowel). It shares its root with the verb mow “to cut grass” (Old Engl. māwan), and its suffix is the same as in warmth, breadth, width, and length.

A bad joke…. Some time ago, I wrote a three-part cycle on the history of the word bad: 24 June, 8 July, and 15 July 2015. This past November, a correspondent asked me what I think about the mysterious male name Badda, which, according to Ekwall’s 1947reliable but not infallible etymological dictionary of English place names, can be detected in Badbury, Baddeley, and several others in many parts of England. Who was this Badda? Ekwall says: “A legendary hero, who was associated with ancient camps.” He gives no references. The question from our correspondent runs as follows: “Might he have been some bogeyman whose name was invoked to keep children away from the fire? Or someone more sinister? An old god, perhaps…. Was he a hermaphrodite or a god of battles or oppression or sleeping (bædd, a bed)?” The Old English form of bed was bed(d), and I wrote about it in the post for 10 June 2015. This spoor is cold. Hermaphrodites, I believe, are also out of the saga (for the reasons discussed in the post). A great legendary hero with the name Badda hardly existed. Such a figure might have been mentioned in Beowulf or by Venerable Bede. A demon seems a more realistic candidate: in Eurasia, there are many monosyllabic demonic names beginning with b. and words like bad, dab, and their likes are easy to coin. But why should anybody give such a name to many places, unless all of them were burial mounds? Perhaps some demon filled people with fear, and Badda was only an apotropaic name, used to avert the influence of the evil creature, but with time the name acquired the sense known to us. All this is guessing, popular at yuletide but devoid of value. Though who knows? Perhaps there is a grain of truth in this guesswork.

Was this the Old English Badda? Image credit: The wolf blows down the straw house in a 1904 adaptation of the fairy tale Three Little Pigs by L. Leslie Brooke. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Was this the Old English Badda? Image credit: The wolf blows down the straw house in a 1904 adaptation of the fairy tale Three Little Pigs by L. Leslie Brooke. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Between the languages

Why can there be no direct connection between Greek kópos “labor” and Engl. job? We have no evidence that such a late English word was borrowed from Greek, and, if it were borrowed, it would have sounded kop, not job. The origin of kópos, though not obscure, is not quite clear. Related words mean “cut down; dig.” So it seems that kop– is indeed an onomatopoeia like job “to peck.” No Greek etymological dictionary suggests the connection with the Greek word for “oar.” Greek etymology has been studied so long and so thoroughly that, if that connection looked promising, somebody would have probably tried to explore it. Another example I have discussed many times is Engl. know, from cnāwan. Old Engl. long a (ā) always goes back to the diphthong ai. Greek had (gi)gnóskein. The forms—cnaiw and gnos—obviously represent different grades of ablaut and, as in the previous case, can only be related (and not quite directly). A loanword would have been identical or almost identical to its source. My newspaper tells me that “a citizen should vote only if they have a reasonable understanding of the issues and candidates.” In the same spirit I would suggest that an etymologist should posit borrowing only if they have a close correspondence between the source and the end product.

Do they have a reasonable understanding of the issues and candidates? Image credit: Voting in election to the State Duma by Marina Krasotkina. CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication via Wikimedia Commons.

Do they have a reasonable understanding of the issues and candidates? Image credit: Voting in election to the State Duma by Marina Krasotkina. CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication via Wikimedia Commons.Nonsense etymology for the holiday season

Is it true that in the proverb “He won’t set the Thames on fire,” temse “sieve,” rather than the name of the river Thames was meant? This question was discussed for decades. No, no one tried to kindle, inflame, or burn down a sieve.

The Oxford Etymologist thanks its readers and correspondents for their attention and interest and for the twelfth time wishes them a Happy New Year. 2017 was rather odd. Let us hope that 2018 will be more even.

An epitaph to 2006-2017, to finish Blog 624:

There was once an unwearying gleaner,/ Whose fatigue made him meaner and leaner./ Flame and fame were not meant for his temse:/ Not a spark from the asterisked stems./ Love a reaper, steer clear of a gleaner.

Featured image credit: The Great Fire of London by Philip James de Loutherbourg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for December 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

Does the route to equality include Indigenous peoples?

At the time of writing, many Australians are preoccupied with the recent result of the same-sex marriage survey (with 61.6% voting in favour of marriage equality). The survey’s result is indicative of a shift in the thinking about ‘rights’ in general, but also about ‘equality’ and what it means in practice. Unsurprisingly also, and as evidenced throughout the public and social media, all those who advocate for more open and inclusive society are pleased by what looks like a public surge for a social change. How then does that affect, if at all, Indigenous peoples in Australia?

Shireen Morris of the Cape York Institute argues that the same as the matter of recognition is important to the same-sex couples (who otherwise can legally co-habit in Australia), the time for recognition has also come for Indigenous Australians: The case for marriage equality is just and right. The case for Indigenous people having a guaranteed voice in their affairs is just and right.

Australians are ready to say ‘yes’ to all groups in the society to be equally represented and be given equal opportunity to participate in the making and shaping of Australian society. However, for the time being at least, the Government sees otherwise.

Do Indigenous peoples need (more) welfare or recognition?

At the global level, there is the political will to recognise what is otherwise obvious. The United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) calls upon States to promote their full and effective participation in all matters concerning them. It has been widely recognised that the protection and promotion of rights of Indigenous peoples contribute to the strengthening of democracy and consolidation of peace. In the same vein, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which overall focus is on reducing inequality within and among countries, in its political declaration identifies Indigenous peoples as one of the vulnerable groups who require to be ‘empowered’.

Despite those political commitments to ensuring that ‘no one is left behind’, any closer interrogation of the available data shows that we are far from reaching those goals. There are over 370 million Indigenous peoples living across the globe, and although they represent 5% of the world’s population, they also represent 15% of the world’s poorest people. Indigenous populations continue to be the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in the world.

At the national level, and taking the example of Australia, despite the many positive steps being taken, the latest UN Human Rights Committee’s report on Australia’s human rights record under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) concluded that Australia continues to struggle to protect basic human rights of the most vulnerable members of the society.

If we look at the life expectancy of Indigenous peoples in Australia it is estimated to be 10.6 years lower for male and 9.5 years lower for female than for non-Indigenous population. This is despite Australian government launching the Closing the Gap Campaign in 2007. The annual reports indicate some improvements in some of the key areas, but the ultimate aim of offering the same opportunities in life to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children as there are for other Australian children by 2030 might be still far away.

Shifting social inequalities

Where lies the problem then? There is no denying that there is a close link between development, empowerment, enjoyment of rights and freedoms, and access to education and health. This relationship is also circular, in that it is much more difficult to enjoy good health if the person’s other rights are not upheld. Also, one’s agency will be significantly curtailed when denied equal access to education or when not able to take up opportunities due to (preventable) health conditions. Any debate about legal justice (and fulfillment of one’s civil and political rights) is necessarily intertwined with social and economic justice (thus one’s enjoyment of social, economic, and cultural rights).

But, power imbalance and inequalities in a society can be moved and changed. The most obvious ways are through education, the law, but also through more targeted social interventions leading to changing norms and behaviours, i.e. social marketing. Social marketing has been used for over 40 years to influence behaviour, ranging from tobacco use cessation, to encouraging healthy eating, to the use of car seat belts. Governments, international organisations, and public bodies use social marketing to shape our ways of thinking and doing. Given the prevailing inequality gaps, Indigenous peoples are often the target of the varied legislative interventions, policies as well as social marketing campaigns.

The latest study into the social marketing campaigns targeting Indigenous peoples reveals that the identified campaigns were carried out in a diverse range of contexts, but mostly focusing on social issues relating to improving health of Indigenous populations. Yet again, the issue of lack of inclusiveness or limited opportunities for the Indigenous population to fully engage with and participate in the development and implementation of these interventions was identified as a pressing issue requiring greater attention by social marketers and governmental or public bodies that invest considerable amounts of public funding in these programmes.

“The time has come for the principle of ‘nothing about me without me’ to be actioned upon. Equality denotes not only the lack of discrimination but also, in practical terms, availability of choice.”

The way forward

Giving voice to Indigenous peoples and their ways of knowing (including Indigenous methodologies) is not necessary only in relation to political recognition but also to social recognition, which affects the everyday decision-making that adds up to the totality of the fabric of the society.

The time has come for the principle of ‘nothing about me without me’ to be actioned upon. Equality denotes not only the lack of discrimination but also, in practical terms, availability of choice. Yet, for choices to be truly exercisable by individuals, it requires lifting the political, social, and economic constraints that impact on individual action.

We need to re-conceptualise the way we think about ‘equality’. The treacherous experience in Australia, and elsewhere for that matter, with Indigenous affairs shows that offering ‘welfare’ is not the same as ‘empowerment’ and creating opportunities for one to be able to exercise their agency. Leaving anyone behind means that the equality route is not travelled at all.

Featured image credit: Australia Aboriginal Culture 002 by Steve Evans. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Does the route to equality include Indigenous peoples? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 26, 2017

New year, new you: 13 books for self-improvement in 2018

Last year, twitter highlighted the most popular New Year’s resolutions for 2017—which included losing weight, reading more, and learning something new among the most common goals.

With 2018 quickly approaching, people all over the world are taking the time to reflect on themselves and determine possible resolutions for the coming year. We’ve put together a reading list of self-improvement books to help our readers reflect and stick to their goals in the New Year.

Boost! How the Psychology of Sports Can Enhance your Performance in Management and Work by Michael Bar-Eli

Sometimes hidden, often neglected, psychological forces drive human performance. Drawing on his career as a sports psychologist, Michael Bar-Eli reveals the skills practiced by elite athletes, and explains how these same tactics can be applied in the boardroom.

An Intelligent Career: Taking Ownership of Your Work and Your Life by Michael B. Arthur, Svetlana N. Khapova, and Julia Richardson

Across industries, navigating career obstacles often proves to be difficult. An Intelligent Career serves as a playbook for the modern worker: offering clear guidance and support on taking charge of opportunities, seeking continuous learning, collaborating with others, and determining when it is time to move on.

Thriving Under Stress: Harnessing Demands in the Workplace by Thomas W. Britt and Steve M. Jex

Workplace stress is common. But does it help or hinder us? Thriving Under Stress emphasizes the surprising ways that stress at work can be used to promote growth—including exercises to help improve the way we respond to stress.

Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World by Iddo Landau

When it comes to meaning in life, we have let perfect become the enemy of the good; we have failed to find life perfectly meaningful, and therefore have failed to see any meaning in our lives. Finding Meaning in an Imperfect World addresses this flawed mindset. With a mix of practical advice and examples from film, literature, and history, this book aims to help people who feel that their lives are not meaningful enough.

Night Call: Embracing Compassion and Hope in a Troubled World by Robert Wicks

Compassion is not easy. Although caring for family members, neighbors, and friends is a central part of a rewarding life, it can also lead to emotional fatigue, or “secondary stress.” In Night Call, acclaimed psychologist Robert Wicks offers stories and principles gleaned over thirty years in the helping and healing industry. The book includes a “personal resiliency retreat,” a five-day guide to self-care and compassion.

Happy holidays 2018! by NordWood Themes. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

Happy holidays 2018! by NordWood Themes. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.Innovating Minds: Rethinking Creativity to Inspire Change by Wilma Koutstaal and Jonathan Binks

From entrepreneurs to teachers, engineers to artists, almost everyone stands to benefit from becoming more creative. Innovating Minds reveals a unique approach to harnessing creative ideas and putting them into action. It offers a fascinating exploration of the science of creativity along with new and valuable resources for becoming more innovative thinkers and doers.

Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory: What’s Normal, What’s Not, and What to Do About It by Andrew E. Budson, MD and Maureen K. O’Connor, Psy.D

Age-related memory loss is common. But how much can be expected? To help you navigate through age-related memory loss, follow the seven factors of memory: (1) Learn what is normal memory, (2) Determine if your memory is normal, (3) Understand your memory loss, (4) Treat your memory loss, (5) Modify your lifestyle, (6) Strengthen your memory, (7) Plan your future.

Mindlessness: The Corruption of Mindfulness in a Culture of Narcissism by Thomas Joiner

The practice of mindfulness has become a key approach to addressing life’s challenges. But have we gone too far? Using examples from popular culture, literature, and social media, Mindlessness exposes the misuse of mindfulness, and considers how we as a society can salvage this valuable technique for improving mental and physical well-being.

The Character Gap: How Good Are We? by Christian B. Miller

We like to think of ourselves, our friends, and our families as decent people. However, hundreds of recent studies in psychology tell a different story: that we all have serious character flaws that prevent us from being as good as we think we are—and we often do not even recognize that these flaws exist. The Character Gap draws on the latest research in psychology to show how most people are not good enough to be virtuous but not bad enough to be vicious, and offers practical strategies for trying to become better people.

Good People, Bad Managers: How Work Culture Corrupts Good Intentions by Samuel A. Culbert

There’s far more bad management behavior taking place today than the well-intentioned doling it out realize. With MBA programs focusing on “success” skills, far too many graduates are entering the workforce without well-practiced managerial skills. Good People, Bad Managers addresses this issues by breaking down the bad habits of today’s managers, and offering practical advice for achieving change.

When Doing the Right Thing Is Impossible by Lisa Tessman

Contrary to what most moral philosophers believe, there are situations in which doing the morally right thing is impossible. Drawing on real-world examples, When Doing the Right Thing Is Impossible explores how and why human beings have constructed moral requirements to be binding even when they are impossible to fulfill.

The Elephant in the Brain: Hidden Motives in Everyday Life by Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson

Human beings are primates, and primates are political animals. Our brains are designed not just to hunt and gather, but also to help us get ahead socially, often via deception and self-deception. The Elephant in the Brain confronts our hidden motives directly: tracking down the darker, unexamined corners of our psyches and blasting them with floodlights.

Presence: How Mindfulness and Meditation Shape Your Brain, Mind, and Life by Paul Verhaeghen

Mindfulness and one of the roads to it, meditation, have become increasingly popular as a way to promote health and well-being. Presence integrates meditation concepts and research evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience literature to help you better understand the science of mindfulness.

Featured image credit: “blur-book-girl-hands” by Leah Kelley. CC0 via Pexels.

The post New year, new you: 13 books for self-improvement in 2018 appeared first on OUPblog.

December 24, 2017

Animal of the Month: Reindeer around the world

We all know Dasher and Dancer, Prancer and Vixen, Comet and Cupid, Donner and Blitzen. But do you know about the different subspecies of reindeer and caribou inhabiting the snowy climes of the extremes of the northern hemisphere? As Santa Claus travels the globe, here’s an exploration of the possible types of reindeer that are pulling his sleigh.

Map background: Winter Abstract Snowflake Background in Blue by Olga Maksimava via Shutterstock. W atercolor map of the world isolated on white by mainfu via Shutterstock .

Featured image credit: Caribou by Free-Photos. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Animal of the Month: Reindeer around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Normative thought and the boundaries of language

Consider this little story. On a planet somewhere far away there’s a community, the Tragic. The Tragic are deeply moral, in the sense of caring deeply about doing the right thing, even when that isn’t in their self-interest. They are also very successful in figuring out what’s the “right” thing, in their sense of right. So they very often do what’s “right” in their sense. Perhaps in both these respects they are better than us.

Another difference between them and us, more importantly, is that their “right” doesn’t mean what our “right” means. It is true of different actions. In what follows, I will call their concept right “right”, their concept ought “ought”, etc. For purposes of illustration, suppose that their “right” is actually true of some actions you would find quite odious. For example, it may be the brutal sacrifice of a small child for the sake of some supposed greater goal.

There’s a clear sense in which the Tragic really seem tragic. Even if they are moral in their sense, they often fail to perform what we judge to be the right actions. Since they use the wrong concepts, we may well pity them.

However, consider now how they might feel about us. They might pity us for corresponding reasons. They might say, “Those Earthlings, they use the wrong concepts! One ought to do what’s right, not what’s right! They perform the wrong actions!”

Who are the pitiable ones, we or they? The situation is symmetrical, for all that’s been said. Evaluating matters using our concepts, they seem tragic. Evaluating matters using their concepts, we seem tragic. Who seems pitiable depends on what concepts are employed.

“Our normative concepts are arguably just some of all the possible normative concepts there are.”

The Tragic is of course a merely fictional community. But the example of the Tragic serves to illustrate a basic point. Our normative concepts are arguably just some of all the possible normative concepts there are. Using our actual concepts, we can judge that it would be misguided to use certain other possible concepts. But similarly, from the point of view of someone who uses other normative concepts, it can seem misguided to use our concepts. Which concepts are the proper ones to use?

Ordinary moral theorizing, of a familiar kind. tries to figure out things like what’s good and what’s right. Attention to alternative normative concepts shows that this isn’t the end of the story. There’s also the question of which concepts are the proper ones to use. If our concepts of good and right aren’t the proper ones to use to guide action, then the investigation into what’s good and right doesn’t have the significance that ordinary moral thinking invests it with. Finding out what’s good and right doesn’t settle how to act, for maybe other concepts are the ones we ought to employ when settling such matters.

So far I have emphasized the possibility of alternative normative concepts, and the importance of this issue for thinking about ethics. But there’s a problem with how I have presented matters. Some may be inclined to take this problem as reason to simply dismiss the problems I have raised here. I think on the contrary that the problem just shows the depth of the problems raised.

Faced with the possibility of alternative concepts, it is natural to wish to ask the questions I have raised. Which normative concepts are the proper ones to use? Ought we to abandon our normative concepts in favour of some alternative ones? But normative concepts are used in the very statement of these questions. And it’s my “proper” and my “ought” that I use (and for that matter my “pitiable” and my “tragic”). But if I frame the questions using my normative concepts, I use some of the concepts that are being questioned, and even if the answer to the question as posed is yes, what can I reasonably do with such an answer? It may be like a corrupt administration asserting its own legitimacy. And of course the problem isn’t avoided if one instead were to use “ought.” The supposed issue of what concepts are the proper ones to use threatens not to be statable. Whenever we try to state what the issue is supposed to be, we fail.

There are different possible reactions to this. Let me close by just briefly mentioning some. One is to say that there is no issue of the kind I have been after: there are facts about what’s right and good, and also facts about what falls under alternative normative concepts, but the idea that there’s a further issue about which concepts are “proper,” in some objective or neutral sense of “proper,” is misguided. Another reaction is to seek to find some way of stating the supposed further issue after all. A third reaction is to say that while there’s this further issue, it’s impossible to express what this further issue is.

The sentiment behind the third reaction is well stated using the words of Ludwig Wittgenstein, from his Lecture on Ethics:

My whole tendency and I believe the tendency of all men [sic] who ever tried to write or talk Ethics … was to run against the boundaries of language. This running against the walls of our cage is perfectly, absolutely hopeless.

Featured image credit: Peter Brueghel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Normative thought and the boundaries of language appeared first on OUPblog.

December 23, 2017

Advertising in the digital age

Although advertising is not new, due to digital technologies people are now attacked with ads every day, 24 hours a day. As more data about us continues to be collected through these digital means, the issues of privacy and surveillance tend to arise. In the following excerpt from Advertising: What Everyone Needs to Know®, Mara Einstein helps us understand how marketers are tracking us, and how to potentially stop it.

How come ads seem to follow me around the Internet?

This is what is known as retargeting. In the sales funnel paradigm, marketers want to interact with you as far down the funnel as possible, the best place being the point of sale. Online, that means the shopping cart. If you put an item into the cart— say, a pair of jeans or the latest bestseller— and then decide you don’t have time to buy it right away, an ad for that product will begin to follow you around the Internet. And it will go from your computer to your cell phone to your iPad or other tablets. The same holds true if you are doing research for something to buy. You begin looking into vacations on Cape Cod or a bicycle trip to Ireland and you can be sure that competitive advertising will follow—even after you book your trip.

When I am being tracked, do marketers really know that it is me by name?

Marketers claim they do not know who is connected to an IP address, nor do they care—at least not beyond the behavior that occurs on the computer, particularly as it relates to product purchases.

While this rings true and, from my discussions with people in the industry, I think it is, this does not mean that the information connected to our computer is anonymous. A number of books, and certainly Edward Snowden, have proved this point.

Two New York Times reporters were able to identify a sixty-two-year-old Georgia woman using anonymous search data from AOL. University of Texas researchers have “de-anonymized” information from Netflix’s database, including information about political preferences. One particularly concerning fact from Julia Angwin’s book Dragnet Nation is that “75 percent of the top one thousand websites included code from social networks that could match people’s names with their Web-browsing habits.” What this means is that if you don’t sign out of Facebook, whenever you are on a site that has the “like” button, Facebook can track you to the site—even if you don’t click the button. This holds true for other social sites as well. Speaking of “likes,” researchers analyzed those seemingly innocuous “likes” of 58,466 Americans and were able to accurately “predict a range of highly sensitive personal attributes including: sexual orientation, ethnicity, religious and political views, personality traits, intelligence, happiness, use of addictive substances, parental separation, age, and gender.”

This is not to scare you, but to make you aware. Every click is tracked. Every post is noted, even to the point of knowing when you have edited your ideas.

Companies know what, where, and how we search. They know how long we spend on a page, a site, and where we move to when we’re done. In addition to tracking our moves, companies experiment with what we do online. One example is the A/B testing of advertising. It can be more personal than this, however. In one example, online dating site OkCupid manipulated data to lead people to believe they were a good match when they weren’t. Given this wrong information, people “liked” the mismatches. This is a well-known type of experiment called priming. It is rarely used in this way to play with emotions. In a true research setting, an experiment like this wouldn’t be allowed. Online, though, we are fair game. As Christian Rudder, OkCupid’s founder, put it: “Guess what, everybody: if you use the Internet, you’re the subject of hundreds of experiments at any given time, on every site. That’s how websites work.” Truer words were never said.

Unfortunately, none of this is done for our benefit. The data and the research and the emotional manipulation are all in the name of selling more products—most of which we probably don’t even need.

Is there a way to stop marketers from tracking me?

On your computer, the best thing to do is to clear out your cookies every day. If you don’t, the information will stay attached to the cookies for three months. You can also stop using your phone for anything except phone calls (I realize that’s probably hard to imagine).

What are ad blockers?

Ad blockers can help you from being tracked both online and on your mobile device. Adblocker Plus is one of the most popular products. However, an increasing number of sites will not allow you to view their content if you are using an ad blocking extension.

Whether you choose to use the technology to block ads or not, it is useful to see how and how many companies, like data brokers and ad exchanges, are attempting to gain access to your computer. Two that I find helpful are Ghostery and Disconnect. When you put these extensions on your browser, they will enable you to see how many organizations are accessing your computer by listing them as the website populates. With that information, you can decide which sites you want to interact with. One site I visited listed more than 6,000 companies trying to access my computer; I did not go back to that site again. As well as listing companies such as DoubleClick (an ad network owned by Google), big data firms like AddThis, and ad exchanges like BrightRoll, Disconnect gives you the option of presenting the data as an infographic. In the middle of the illustration is a circle representing the site you are on, and coming off that circle are spokes that have circles on the end that contain the name of the company tracking you. Seeing dozens of bubbles floating on the screen gives you a visceral sense of just have surveilled you are.

However, even ad blockers are turning out to be not all they were cracked up to be. In September 2016, AdBlocker Plus announced that it would begin selling “acceptable” ads.

Featured image credit: “Close up code computer” by Lorenzo Cafaro. CC0 Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Advertising in the digital age appeared first on OUPblog.

Questioning the magical thinking of NHS RightCare

When drafts of Sustainability and Transformation Plans (STP) for the 44 “footprints” of the NHS in England began to surface last year, a phrase caught my eye: “Championing the NHS Right Care approach to others within commissioner and provider organizations and building a consensus within the teams of those organizations”. This was the first bullet point for clinical leadership, from the 30 June 2016 version of the Cheshire and Merseyside STP.

The leaked draft became a hot topic. The Liverpool Echo headlined a “£1bn black hole” in the Merseyside NHS, and exposed a £300k fee paid to management consultants PwC for their work on the STP. When it was eventually published, the STP mentioned RightCare repeatedly, with no details.

According to Liverpool Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG), “The NHS Five Year Forward View modelled the need for the health system to generate £22 bn of efficiencies by 2020/21. The NHS RightCare programme is a critical part of NHS England’s approach to driving allocative efficiency in order to meet this need.”

In other words, RightCare is one component in a massive efficiency savings plan. NHS England instructed CCGs to identify targets for improvement, using RightCare, and most CCGs appear to have done so.

In the opening line of a New Statesman article, NHS RightCare national director Prof. Matthew Cripps describes this NHS England programme as “a proven approach that delivers better patient outcomes and frees up funds for further innovation,” a phrase appearing on RightCare webpages and echoed in CCG documents.

What does “a proven approach” mean? It might mean a convincing majority view from peer-reviewed articles in mainstream journals, in favour of the methodology which CCGs are now instructed to follow. Despite the fanfare, endorsement by NHS England, and the involvement of Public Health England, no such articles turn up in PubMed.

For each CCG, RightCare assigns a fixed comparator group of ten “similar” CCGs, and then, for any particular outcome, finds the “Best 5” of those ten. The CCG is invited to measure itself against the Best 5 average, and potential savings and/or quality improvements are calculated by comparison with that average.

When it comes to lung cancer mortality for those below 75 years (Directly age-standardised against the European standard population), Liverpool’s Best 5 are Brighton, Bristol, Sheffield, Newcastle, and Stoke. The Cancer and Tumours Focus Pack suggests that 80 lives per year could be saved if Liverpool CCG matched their average mortality.

But Liverpool isn’t Brighton, Bristol, or even Sheffield. If the areas exchanged populations and Liverpool eradicated environmental and occupational hazards, lung cancer mortality might improve dramatically. In reality, the NHS in each area has to deal with incidence in the existing population, using proven diagnostic and treatment regimes, and implement preventative measures for the future. In fact, Liverpool has better one-year survival and smoking cessation rates than the Best 5 averages, but its high mortality is driven by incidence, which is largely outside the CCG’s control.

If there are good reasons to think a CCG is comparable to some others, then investigating unexpected observed differences may identify real issues which planners may be able to address. No one would object if quality improvements and potential savings are found, if they can be achieved without other adverse impacts. But what does “comparable” mean?

‘Perhaps NHS England never expected RightCare to be a “proven approach”, but welcomed it to justify budget cuts.’

I argue that CCGs are only comparable for a particular outcome if a model which succeeds in fitting the national data for that outcome makes similar predictions for the CCG and its comparators. A model which doesn’t fit the data can’t be used. Finding a suitable model is a first step before making comparisons. If a good model predicts dissimilar values, and such differences actually occur, that can help confirm the model without indicating a problem. Compared with Liverpool, Brighton has much lower values of lung cancer incidence and health deprivation, key factors which influence lung cancer mortality; their different performance is predictable, and doesn’t signal an opportunity for Liverpool CCG.

RightCare doesn’t specify any models, and its method of identifying the “Similar 10” just once for all outcomes relies on a general measure of differences in standardised demographic variables and deprivation. For any particular outcome, these factors may be insufficient, some may be irrelevant, and the relevant factors may have different impacts. Using an appropriate model for lung cancer mortality leads to different comparator groups, and most of the purported opportunities vanish.

In a simulation comparing hypothetical CCGs with the “Best 5” average from a “Similar 10” whose populations all have identical risks, the RightCare method finds significant opportunities over 12% of the time, when there are none.

Can anything be rescued from this morass? As long as generating £22 bn of efficiencies by 2020/21 remains the goal, service improvements are virtually impossible. Freed from that constraint, comparisons between localities may help if they draw on models able to predict specific data, rather than magically assuming that a fixed set of demographic peers is useful for all outcomes. However, even with appropriate comparators to point the way, CCGs may be unable to control deprivation, stress, occupational and environmental hazards, or undiagnosed disease, either immediately or in a few years’ time.

Perhaps NHS England never expected RightCare to be a “proven approach”, but welcomed it to justify budget cuts. But the NHS is supposed to deliver evidence-based medicine, and clinicians are trained on the basis that science underpins therapy. If RightCare is to be a “proven approach”, its proponents should address questions of methodology openly in the public health literature. Isn’t that how science works?

Keep Our NHS Public by Tony O’Sullivan. Reproduced with permission via Keep Our NHS Public .

The post Questioning the magical thinking of NHS RightCare appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know your December celebrations?

In many countries throughout the modern world, December has become synonymous with the celebration of Christmas. Despite this focus, there are many other December celebrations including the Buddhist Rōhatsu and Jewish Hanukkah, secular festivities such as Kwanzaa in America and Hogmanay in Scotland, and ancient Roman rituals such as Saturnalia. To wrap up this festive season, discover some fascinating (and lesser-known) facts on these December celebrations.

Rōhatsu

Buddhism has been practiced in Japan ever since its official introduction in 552 CE, exerting a major influence on the development of Japanese society and culture. The birth of the historical Buddha is celebrated on 8 April in the Hana Matsuri festival, his enlightenment on 15 February (Nehan) and his death on 8 December (Rōhatsu). Many Buddhist festivals also coincide with New Year festivities, such as the Tibetan “Great Prayer Festival” which falls on the 4th-11th day of the 1st Tibetan month.

Hanukkah

Hanukkah (12-20 December) is a Jewish festival celebrated all over the world, observed by the kindling of lights in a menorah. But did you know that there is also a unique culinary tradition? Popular cheese-based dishes such as kugel and cheesecake are eaten during Hanukkah to honor the Biblical figure Judith, who gave the General Holofernes wine and cheese – cutting off his head once he became drunk. This encouraged the Israelites to defeat Holofernes’s terrified troops.

Saturnalia

Although it is not celebrated today, Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival which lasted for seven days around 17-23 December. During this time Roman life was inverted; slaves were granted temporary liberty and were allowed to dine with their masters, leisure-wear was worn instead of togas, and presents were exchanged. Each household chose a mock king to preside over the festivities and feasting – a feat repeated in the medieval Feast of Fools.

Winter Solstice

Taking place on 21 December, the Winter Solstice (also known as midwinter) is an astronomical phenomenon marking the longest night of the year. It has been celebrated since the late-Neolithic period, and many myths and rituals have developed around this event. For instance, the Greek poet Hesiod warned that waiting too long to plough, particularly during the winter solstice, would yield a poor crop.

Box, Card, Celebrate by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay.

Box, Card, Celebrate by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay.Yuletide

“Yuletide” is a phrase synonymous with the festive season, with an interesting history in the US. It was only during the 1820s that the Yuletide season (21 December – 1 January) became popular when modernization in terms of communication and transportation helped to spread beliefs about the birth of Christ. When new railroads and roads were constructed, Americans started to feel connected, and this provided an effective avenue for the birth of a new Christmas tradition.

Newtonmas

Some atheists and sceptics have referred to 25 December as “Newtonmas”, a humorous reference to Christmas and Isaac Newton’s birthday. Participants send cards wishing “Reason’s Greetings!”, and swap boxes of apples and science-related items as presents. Sir Isaac Newton was the most eminent physicist of his day, but he was also a religious man. He was an unorthodox believer however, denying the doctrine of the Trinity in private.

Kwanzaa

In 1966 Maulana Ron Karenga created the holiday of Kwanzaa (26 December – 1 January), believing that black people in the United States needed a holiday that celebrated their African heritage. The word “Kwanzaa” is derived from the Swahili word kwanza meaning “the first.” It is spelled with an additional “a” at the end to make it a seven-letter word, so that it corresponds with the theme of seven which occurs throughout the holiday and its celebrations. Kwanzaa lasts for seven days, and the seven principles of Kwanzaa are umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith).

Boxing Day

Boxing Day (26 December) originated in the United Kingdom, and is celebrated amongst friends and family. This has not always been the case though, and Boxing Day presents used to be given as gratuity for services rendered, rather than of a gift between equals. In the 1620s to 1640s, apprentices and servants received money as gifts from their employers on Boxing Day. By the 18th century employers were complaining loudly of the amount they were expected to pay out. The satirical magazine Punch included regular pieces mixing good humour and complaint, for example: “How much longer, we ask with indignant sorrow, is the humbug of Boxing-day to be kept up for the sake of draining the pockets of struggling tradesmen…”

Hogmanay, or New Year’s Eve

Traditionally, the most important day of the year in Scotland was New Year’s Eve (31 December). The name Hogmanay was not in use until the 1600s, but the celebration dates back to ancient times. The name is derived from the Old French word aguillanneuf, which meant “a gift at the New Year.” Before the 1850s, the celebration of the New Year was very different, and similar to the Scottish Hogmanay in its gift-giving.

Featured Image credit: Xmas, Background, Celebrate by rawpixel. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post How well do you know your December celebrations? appeared first on OUPblog.

Some of the mysteries of good character

The topic of character is one of the oldest in both Western and Eastern thought, and has enjoyed a renaissance in philosophy since at least the 1970s with the revival of virtue ethics. Yet, even today, character remains largely a mystery. We know very little about what most peoples’ character looks like. Important virtues are surprisingly neglected. There are almost no strategies advanced by philosophers today for improving character. We have a long way to go.

We do know, though, that matters of character are vitally important. Consider the news these days, dominated by people like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey. Or consider the behavior of our heroes, like Lincoln and King, or our villains, like Hitler and Stalin. Or consider the latest scandals in the entertainment world, professional sports, or politics. So much of what has happened can be traced back to the character of the people involved. And to take it one step further, thanks to the latest psychological research, character traits have been linked to all kinds of things that we care about in life: optimism, academic achievement, mood, health, meaning, life satisfaction…the list goes on and on.

To say that philosophers—who have been studying character extensively for thousands of years—are mostly in the dark about the topic, surely sounds like I am exaggerating, right? Maybe that’s true, but let me offer two concrete illustrations.

1. Neglected Virtues. The moral virtues are good character traits like justice, temperance, and fortitude. Here are two questions (among many others) you can ask about these virtues. First, conceptually, what do they involve? How, for instance, would you characterize a temperate person? Or a heroic one? Secondly, on empirical grounds, do people actually have the virtues (and if so, how many people and which virtues)? For instance, are there actually any temperate people today?

To help with the empirical question, there has been a recent flurry of interest among philosophers in consulting studies in psychology, and thinking about whether the behavior displayed in those studies is virtuous or not. For a virtue like compassion, real progress has been made in reading the relevant studies carefully, with the conclusion being that most people are not in fact compassionate. Unfortunately, philosophers don’t have much of an idea about what is going on empirically with most of the other virtues (and I’m not sure anyone else does either, for that matter). Part of the reason why is that for some moral virtues there just isn’t the wealth of existing studies to analyze, in the way that there is for compassion. Stealing is a good example—as you might imagine, it is hard to do helpful experimental studies of theft.

But part of the reason is also that some virtues have simply not been on our philosophical radar screens. The attention of philosophers has been elsewhere.

Carte de visite of Sojourner Truth by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Carte de visite of Sojourner Truth by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Take the virtue of honesty, for instance. If any virtue is on most people’s top five list, it is that one. Yet it has had no traction at all in the philosophy literature. In fact, there has not been a single paper in a mainstream philosophy journal on the moral virtue of honesty in over fifty years.

Or take the virtue of generosity—just three papers in the past forty years (by way of comparison, there are over two dozen papers on the virtue of modesty—who would have expected that to happen!).

So the upshot is that compassion is likely to be a rare virtue. But at this point it is not at all clear how we are doing with the rest of them. Indeed, in some cases we are not even clear what the virtues look like in the first place.

2. Virtue Development. The natural suspicion, of course, is that across the board we are not doing very well when it comes to being people of good moral character. History, current events, the local news, and social media all seem to confirm this. Hence it seems apparent that there is a sizable character gap:

There are moral exemplars, people like Abraham Lincoln and Sojourner Truth, whose character is morally virtuous in many respects.

Examining their lives ends up reflecting badly on most of us, myself included, since it illustrates in vivid terms just how much of a character gap there really is.

To try to at least reduce this gap, it would be helpful to have some strategies which can, if followed properly, help us to make slow and gradual progress in the right direction. Naturally philosophers needn’t be the only ones who can come up with these strategies, but it would be nice if we had something to say that is practically relevant, empirically informed, and actually efficacious if carried out properly.

By and large, we haven’t had much to say. But there are signs that this is beginning to change, thanks to the work of Nancy Snow, Julia Annas, Jonathan Webber, and a few others. In fact, the development of character improvement strategies strikes me as one of the most promising areas of philosophy in the coming decade. Many good and innovative dissertations are there for interested graduate students to tackle.

My hope is that this groundswell of interest in how to cultivate the virtues will continue to expand in the coming years. These are indeed early days in the philosophical study of character. And exciting days too, full of so many worthwhile possibilities to explore.

A version of this post originally appeared in The Philosopher’s Magazine.

Featured image credit: Railway platform by aitoff. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Some of the mysteries of good character appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers