Oxford University Press's Blog, page 291

December 12, 2017

Ten facts about Panpipes

The panpipes or “pan flute” derives its name from the Greek god Pan, who is often depicted holding the instrument. Panpipes, however, can be found in many parts of the world, including South America, Oceania, Central Europe, and Asia.

Panpipes are a collection of end-blown flutes of different pitches without a mouthpiece joined in a bundle or raft. The player blows horizontally across the top of the pipes.

The earliest known images of panpipes appear in drawings of animal dances from Catal Hüyük in Anatolia dating from the 6th millennium BCE.

In Europe, the panpipes were first popularized in Italy, particularly among the Etruscans.

While many panpipes include pipes of varying lengths, in Greece, the panpipe called the syrinx uses pipes of the same length but stopped at different lengths with wax to alter the pitch.

Romanian panpipes have a concave row of 20 pipes that are stopped with cork and filled with beeswax. The tuning of the instrument is dictated by the quantity of wax.

In Russia, the panpipes known as kuviklï are considered a woman’s instrument, and are played for dance music or as an accompanying instrument for singers in an ensemble.

Image credit: “Stephen Cohen (3)” by PhotoAtelier. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: “Stephen Cohen (3)” by PhotoAtelier. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.In the Solomon Islands, panpipes are played in elaborate ensembles by men and boys. Their music is based on natural sounds and events.

Panpipes were also used in ancient China where they were shaped to resemble the wings of a phoenix. The Chinese panpipes continued to have associations with the phoenix decoratively and musically.

In the altiplano high plateau of Bolivia and Peru, men typically play panpipes while women dance to panpipe music.

The Ecuadorian panpipes or “rondador” are shaped in a zigzag style that gradually becomes longer. They are usually made out of cane, but can be made from the thin feathers of a condor or vulture.

Featured image: “Image from page 648 of “Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution” (1895)” by Photo Internet Archive Book Images . Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Ten facts about Panpipes appeared first on OUPblog.

Revitalizing culture through the remnants of colonization

In the summer of 1791, Thomas Jefferson sat with three elderly women of the Unkechaug tribe of Long Island. Convinced that these women were among the last living speakers of Unkechaug, Jefferson transliterated a list of Unkechaug words on the back of an envelope alongside the English translation. The words were fairly universal: animals, plants, body parts, colors, simple verbs, and numbers. The list survives under the title of “Vocabulary of the Unkechaug Indians, 1791″ at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. It is part of a fragmentary “American Indian Vocabulary Collection,” also collected by Jefferson. Most of this collection was destroyed in 1809 when a thief threw a pile of Jefferson’s papers into the James River while searching for something more valuable.

1791 marked Jefferson’s foray into a hobby of American Indian Vocabulary collecting that, while lasting the better part of two decades, never amounted to the scientific evidence that he envisioned: irrefutable proof of the origins of North American native populations. After the incident on the James River, Jefferson let this aspiration die. Only a tiny portion – about 6% – of his linguistic papers was salvaged, dried off, and preserved—albeit mud-splattered and torn—in the American Philosophical Society archives. Even so, Jefferson’s efforts to collect and transliterate complex and primarily oral indigenous languages promoted more concerted efforts by the philologist and third president of the American Philosophical Society, Peter Du Ponceau.

These efforts to collect and preserve American Indian languages have been dismissed by scholars as instruments of colonization—agents of evangelization in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and then as a way of archiving the nation’s past as its indigenous inhabitants were being violently destroyed in the nineteenth century. American Indian language texts also present an interpretive problem. Even with language skills, it is difficult, if not impossible, to discern the accuracy of the transliteration, for the missionaries themselves did not have a firm grasp of how to record words phonetically or how to understand different syntaxes and grammars.

Yet, despite the fragmentary, elusive, and illegible qualities attributed to the archive of American Indian language texts, there is much that can be gleaned from them. What knowledge did the three Unkechaug women transmit to Jefferson in the moment of their 1791 encounter? In what form was this knowledge recorded? What if we reversed our perspective on Jefferson’s “Indian Vocabularies” and instead of viewing them as documents of colonization we saw them as evidence of indigenous interlocution or resistance?

The language revival projects practiced by linguists and indigenous descendants reverse some of the deleterious effects of colonization.

This is precisely how American Indian language texts have come to be viewed by tribal descendants as well as linguists and scholars working on projects of language recovery. Long Island Indians have recovered a language of which there are no recorded speakers since the early nineteenth century from Jefferson’s “Vocabulary of the Unkechaug Indians, 1791.” Many of the eastern Algonquian languages, long declared “extinct” by linguists, have been reconstructed through colonial texts. Using the library of Massachusett texts left by seventeenth-century missionary John Eliot, Jessie Little Doe Baird has restored Wampanoag (or Wôpanâak) to the language’s ancestral home in southeastern New England. She won a MacArthur Fellowship in 2010. Daryl Baldwin received the same honor in 2016 for his work restoring the Miami language and culture.

Colonial archives have been re-purposed, salvaged from their historical role in evangelizing, categorizing, and archiving the indigenous inhabitants of North America. The language revival projects practiced by linguists and indigenous descendants reverse some of the deleterious effects of colonization. Learning to speak the language of one’s ancestors produces a form of “rhetorical sovereignty,” said the the Ojibwe scholar Scott Richard Lyons.

In addition to revitalizing culture in the present, the archive of American Indian language texts reveal forms of rhetorical sovereignty at the moment of their creation. When trying to translate the Bible into Massachusett, John Eliot experienced firsthand the challenges of finding words to match Christianity’s purportedly universal truths. Even when a correspondence could be found, the reception of words across distinct cultures could not be controlled. Languages resist translation. Languages carry with them a cosmos that is not easily eradicated or collapsed into another system of belief. Which is why the vast archive of American Indian Language texts that has been passed down to us from the colonial era enjoys a double life. To be sure, the production of these texts worked in the service of colonization, destroying the languages that the missionaries sought to transliterate, and all in the service of evangelizing or enlisting indigenous people in imperial goals. Yet this archive is also the repository of key forms of indigenous knowledge. It records and preserves remnants of native culture and indigenous language encounters that may have otherwise been lost.

In 1792, Congressman William Vans Murray, working for Thomas Jefferson, interviewed a descendent of the Nanticoke tribe who went by the name Mrs. Mulberry. Mrs. Mulberry steadfastly refused to stick to Jefferson’s script. Rather than adhering to Jefferson’s generic list, Mrs. Mulberry ended up creating a list of words distinct to the Maryland countryside: oyster, back creek, shore, perch, crab, eel, honeysuckle, dogwood marsh. After describing the natural world of her ancestral home, she then narrated recent Nanticoke history through a vocabulary of war: blood, arrows, bows, King, Queen, War, peace, warrior. The revised list that Murray sent to Jefferson resisted the categories that Jefferson sought to impose across a vast array of indigenous tribes. In their place, Mrs. Mulberry recorded in the archive of Americana, and preserved at the American Philosophical Society, knowledge of indigenous land as well as the violence done to that land through a history of colonial warfare. In doing so, she participated in the creation of a colonial archive ripe for reappropriation and revitalization.

Featured image credit: Photograph of Washoe women working by U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Revitalizing culture through the remnants of colonization appeared first on OUPblog.

December 11, 2017

The first contracting white dwarf

White dwarfs are the remnants of solar-like stars that have exhausted the reservoir of fuel for the nuclear fusion reactions that powers them. It is widely believed, based on theoretical considerations, that young white dwarfs should experience a phase of contraction during the first million years after their formation. This is related to the gradual cooling of their interior which is not yet fully degenerate. In several million years the central temperature of a white dwarf decreases from several hundred million degrees to few tens of millions and also the surface temperature cools down. During this period the size of the white dwarf can become few hundred (or few tens, depending on mass and exact time interval) kilometers smaller. However, there were no observational indications for this important effect up to now. First, because most of the known white dwarves are much older, second because we do not have a direct and precise way to measure the radii and their variations in these stars.

However, we might have found the first observational evidence for a contracting white dwarf by studying the enigmatic X-ray source HD49798/RX J0648.0-4418, which is located at a distance of 2,000 light years, in the Puppis constellation. Despite it being known since the seventies of the last century that the 8th magnitude hot star HD49798 is a member of a binary with orbital period of 1.5 days, the nature of its companion remained a mystery for a long time. In 2009, thanks to observations with the XMM-Newton X-ray satellite, Mereghetti et al. found that the peculiar properties of this binary can be explained if the companion of HD 49798 is a rapidly rotating and fairly massive (1.3 solar masses) white dwarf, which emits X-rays due to the accretion of matter captured from the stellar wind of its companion star.

With further X-ray observations, we recently discovered that the rotational velocity of this white dwarf has been steadily increasing over the last twenty years. Its spin period of 13.2 seconds is decreasing by about seventy nanoseconds every year. This might seem a very small change, but it is actually a very large effect for a body weighing more than our Sun, but with a radius smaller than the Earth’s. Indeed, such a large spin-up rate could not be easily explained in standard ways (i.e. by the captured angular momentum of the accreting matter).

Artist’s impression of the binary system HD 49798, consisting of a fastly rotating white dwarf (the perl-like star surrounded by an accretion disc) that captures mass from the stellar wind of its hot subdwarf companion (shown in blue as it is a helium star with large surface temperature and high luminosity). Image credit: Francesco Mereghetti, background image: NASA, ESA and T.M. Brown (STScI). Used with author’s permission.

Artist’s impression of the binary system HD 49798, consisting of a fastly rotating white dwarf (the perl-like star surrounded by an accretion disc) that captures mass from the stellar wind of its hot subdwarf companion (shown in blue as it is a helium star with large surface temperature and high luminosity). Image credit: Francesco Mereghetti, background image: NASA, ESA and T.M. Brown (STScI). Used with author’s permission.So what is causing this phenomenon? We found that, just as figure skaters would bring their arms closer to their bodies to rotate faster, the high spin-up rate can be easily explained by the contracting of the white dwarf. The calculations of the previous evolution of this compact object made with a computer code and presented in our paper show that the white dwarf has an age of only about two million years. The contraction rate of about one centimeter per year expected for this age is exactly the correct amount to explain the measured spin-up rate, showing that this is the first contracting white dwarf ever identified.

Computer simulations of the formation and evolution of binary stars, performed by Alexander Kuranov and Lev Yungelson, demonstrate that there are several dozens of systems very similar to HD49798 in our Galaxy. In addition, there may be several hundreds of systems of this type with slightly different parameters. Thus, it is not surprising to find one of them within 2,000 light years from us. The discovery of new systems of this kind will allow us to learn more about the youth of white dwarfs and to advance our understanding of these peculiar compact stars ruled by the laws of quantum mechanics.

Featured image credit: White dwarf in AE Aquarii by Casey Reed / NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The first contracting white dwarf appeared first on OUPblog.

Unfitness to plead law and the fallacy of a fair trial

Cognitive disability is not well accommodated in criminal justice systems. Yet, people with cognitive disability are overrepresented in these systems. Unfitness to plead law is one legal mechanism that is purported to assist when a person with cognitive disability is charged with a crime. The aim of such laws is claimed to be to prevent an individual with cognitive disability to have to engage in a trial process.

It has been said that unfitness to plead law exists in an effort to ensure the right to a fair trial for people with disability. However, in practice, once an individual is found unfit to plead, they do not get the opportunity to engage with the trial process at all and are not afforded the same rights to due process and procedural fairness. In addition, it is common that once an individual is found unfit to plead, they are detained for longer than they could have been if they were convicted – in some jurisdictions, they can even be held indefinitely.

“Marlon Noble. He was found unfit to plead and held in prison for over ten years. Ultimately, there was no evidence of him ever having committed a crime. The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities determined that Australia has violated Marlon’s human rights.” Photo by Rory Dempster. Used with permission via University of Melbourne.

“Marlon Noble. He was found unfit to plead and held in prison for over ten years. Ultimately, there was no evidence of him ever having committed a crime. The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities determined that Australia has violated Marlon’s human rights.” Photo by Rory Dempster. Used with permission via University of Melbourne.This presents several human rights challenges. The first is that, if the aim is to preserve the right to a fair trial for people with cognitive disability, that aim is often not being met. The second is that people with cognitive disability who are found unfit to plead are being denied their right to legal capacity – to be recognised as a person before the law with rights and responsibilities and to be recognised as a decision-maker. The third is that people with cognitive disability are often not being provided the support necessary to engage with the criminal justice system in such a way that would facilitate a fair trial and the recognition of the right to legal capacity.

The right to a fair trial includes, among other elements, the right to procedural due process and the right to be free from discrimination in the trial process. The right to procedural due process includes the right to test the case against you, the right to confront and cross-examine witnesses, the right to free legal assistance, and the right to be informed of the charges against you in a language you understand, among others. In many jurisdictions, once a person is found unfit to plead, they often end up in limbo with no clear process for testing the case against the person, no appropriate legal assistance provided, and no accessible detention facilities available. Alternatively, in some jurisdictions, there are processes in place and once an individual is found unfit, they are funnelled into a ‘special’ trial process, in which evidential rules are different and the individual is often largely excluded from the trial process. While this is arguably more favourable than a state of limbo, these special processes often to not afford the individual the same level of protection for his or her right to due process as a normal trial would.

“University of Melbourne Unfitness to Plead Project Team, from left of back row: Dr Piers Gooding, Professor Eileen Baldry, Sarah Mercer, and Louis Andrews; from left of front row: Professor Bernadette McSherry, Dr Anna Arstein-Kerslake, and Dr Ruth McCausland.” Photo by Rory Dempster. Used with permission via University of Melbourne.

“University of Melbourne Unfitness to Plead Project Team, from left of back row: Dr Piers Gooding, Professor Eileen Baldry, Sarah Mercer, and Louis Andrews; from left of front row: Professor Bernadette McSherry, Dr Anna Arstein-Kerslake, and Dr Ruth McCausland.” Photo by Rory Dempster. Used with permission via University of Melbourne.The right to legal capacity mandates that all people are respected as decision-makers on an equal basis and requires states to provide support to exercise legal capacity – to make legal decisions. Unfitness to plead laws purport to avoid an unfair trial by not forcing people to undergo a trial process on the basis that they cannot sufficiently understand the charges against them and cannot meaningfully participate in the trial process. If states met their obligations to provide support to people with cognitive disability to exercise their legal capacity in the context of the criminal justice system, it could obviate the need for unfitness to plead laws. Instead people with cognitive disability who are charged with a crime would be respected as equal before the law, they would be provided with the support needed to engage in the trial process, and their rights to both legal capacity and a fair trial could be met in many instances.

The Unfitness to Plead project at the University of Melbourne provided an evidence base for implementing support for people with cognitive disability charged with a crime. The crux of the issue is that human rights law applies to people with cognitive disability in the exact same way that it applies to people without cognitive disability. Under current unfitness to plead law, people with cognitive disability are not having their rights to a fair trial or legal capacity realised on an equal basis with others. Providing support at the time of an individual being charged with a crime is one way to avoid findings of unfitness. Law reform is also needed to ensure that people with cognitive disability are not subject to a separate and unequal form of justice.

Featured image credit: Courtroom by 12019. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Unfitness to plead law and the fallacy of a fair trial appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2017

Human Rights Day: a look at the refugee crisis [excerpt]

Human Rights Day, held on On 10 December every year, honors the UN’s adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – a document which details the rights that all human beings, regardless of race, religion, nationality, or religion, are entitled to. The following excerpt from Refuge: Rethinking Refugee Policy in a Changing World takes a look at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, an agency tasked with protecting the human rights of stateless people throughout the world.

Refugee protection is a global public good: all countries benefit to some degree from the human rights and security outcomes it yields, irrespective of whether they contribute. As with all public goods – like street lighting at the domestic level – free- riding and under- provision are inevitable unless some kind of centralized institution creates rules for effective cooperation. Yet existing institutions offer insufficient mechanisms to ensure adequate overall provision. The cooperation problem in the refugee regime can be thought of as what game theorists would describe as a ‘suasion game’: one in which weaker players are left with little choice but to cooperate and stronger players are left with little incentive to cooperate.

This explains in part why fewer than 1 per cent of the world’s refugees get access to resettlement in third countries beyond their region of origin. It explains why UNHCR’s assistance programmes around the world are chronically under- funded. It explains why distant countries in the global North, who take a relatively tiny proportion of the world’s refugees, constantly compete with one another in a ‘race to the bottom’ in terms of asylum standards in order to encourage refugees to choose another country’s territory rather than their own.

Image credit: “Statue Of Liberty Landmark Liberty Statue America” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.

Image credit: “Statue Of Liberty Landmark Liberty Statue America” by Free-Photos. CC0 via Pixabay.In the absence of clear rules, attempts by UNHCR to overcome this collective action failure have had to be ad hoc and episodic. The organization relies upon annual voluntary contributions for almost all of its budget, rather than having access to assessed, multi- year funding contributions. This makes it easy for governments to change their priorities but difficult for UNHCR to plan. Meanwhile, in order to address long- standing or large- scale refugee crises, it has relied upon the UN Secretary- General convening international conferences such as the International Conferences on Assistance to Refugees in Africa (ICARA I and II) of 1981 and 1984, the International Conferences on Indochinese Refugees of 1979 and 1989, and the International Conference on Central American Refugees (CIREFCA) of 1989, intended to generate reciprocal governmental commitments for a particular crisis.

To take an example, after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, hundreds of thousands of Indochinese ‘boat people’ crossed territorial waters from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia towards South- East Asian host states such as Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the host states, facing an influx, pushed many of the boats back into the water and people drowned. Like today, there was a public response to images of people drowning on television and in newspapers, but addressing the issue took political leadership and large- scale international cooperation. In 1989, under UNHCR leadership, a Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) was agreed for Indochinese refugees. It was based on an international agreement for sharing responsibility. The receiving countries in South- East Asia agreed to keep their borders open, engage in search- and- rescue operations, and provide reception to the boat people.

However, they did so based on two sets of commitments from other states. First, a coalition of governments – the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the European states – committed to resettle all those who were judged to be refugees. Second, alternative and humane solutions, including return and alternative, legal, immigration channels were found for those who were not refugees in need of international protection. The plan led to over 2 million people being resettled and the most immediate humanitarian challenge was addressed, partly because of the political will generated at the end of the Cold War and partly because of exceptional leadership by UNHCR.

As the Indochinese example highlights, these ad hoc initiatives have sometimes succeeded when they have been accompanied by decisive leadership and a clear framework for collective action, and have met the interests of states. But such initiatives have been rare and their very existence is indicative of a broader structural weakness in the refugee regime: the absence of norms for responsibility- sharing.

In the twenty- first century, increasing opportunities for mobility and migration have further complicated the question of ‘Where to protect?’ Rather than waiting passively for governments to decide where protection should be provided, more and more refugees have been making this decision for themselves. ‘Spontaneous arrival asylum’ – including moving directly onwards to more distant countries in the North by using the service of human smugglers – has become the primary means by which refugees are redistributed beyond their ‘regions of origin’.

In response, those receiving countries in the developed world have created a range of new practices relating to where refugees should receive protection. Most of these have had in common the aim of reasserting, by fiat or coercion, the idea that refugees should have received protection nearer to home rather than embarking on independent journeys. One such example is the advent of the ‘safe third country’ concept – the idea that refugees should seek asylum and remain in the first safe country they reach and if they have passed through such a country they can be subject to removal. Another example is the idea of ‘outsourcing’, with countries seeking bilateral agreements in which they pay another country to admit spontaneous- arrival asylum- seekers and process their claims. Australia’s bilateral agreement with Nauru is perhaps the most infamous example. These techniques may well offer a convenient means to contain refugee populations but they are neither supportive of refugee protection nor sustainable.

Featured image credit: “Migrants at Eastern Railway Station – Keleti, 2015.09.04” by Elekes Andor. CC BY-SA 4.0 via

Wikimedia Commons.

The post Human Rights Day: a look at the refugee crisis [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Our Blue Planet

Over the last seven weeks, our Blue Planet II series has focused on the underwater habitats and marine life that live on “our blue planet”, featuring an assortment of captivating creatures, including manta rays, blennies, spinner dolphins, sea turtles, octopus, starfish, and whales; in many different habitats, from the darkest depths, to coral reefs, coastal tide pools, the open ocean, and underwater forests.

Blue Planet II’s final episode, Our Blue Planet, looks to the future and asks, “What will our oceans look like five, ten, twenty years from now?”, examining the ongoing issues of marine pollution, climate change, and other human activity that impacts our oceans. But despite this bleak outlook, there are messages of hope: global organisations, communities, and individuals working together to protect the future of our oceans for all the creatures who call it home. For our last installment of the Blue Planet II series, we reflect on the impact humans have had on the oceans and take a look at what the future has in store for our relationship with the vast blue planet.

Since 1979, overall ocean surface water temperatures have warmed by 0.133 ± 0.047°C. This has mainly happened in the upper 700m of the ocean, although warming has also been recorded at depths as far as 3,000m.

Signs of ‘ecosystem distress’ appear at local, coastal, and basin-wide scales. Symptoms include early signs of eutrophication in local and coastal waters, formation of local abiotic zones, reduction in species diversity, reduction in genetic diversity, increased dominance by opportunistic species, and increased disease prevalence. Despite reductions in loadings of some toxic substances in recent years, stress from human activities on the Gulf of Bothnia continues to impact the ecosystem at all spatial scales.

Landfill and dredging are two of the most harmful coastal activities for coral reefs. This is partly because of direct burial of shallow reefs, but also because sedimentation plumes arising from the activity commonly spread out over several kilometres, blanketing reefs far from the original sites of dredging or construction. The scale of this activity can be enormous: the Saudi Arabian Gulf coast is now nearly two-thirds artificial, as a result.

Sometimes it’s the little things that can cause the most damage. Those tiny microbeads in your favourite hand soap or body wash can be detrimental to sealife, such as mussels.

Mangroves by dolvita108. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Mangroves by dolvita108. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.In tropical coastal ecosystems, mangrove forests are important as feeding, spawning, breeding, and nursery grounds for many marine species. Littorinid snails live on mangrove trees, forming an important component of the mangrove ecosystem and have been used as bioindicators of environmental health and community stress. However, high human population pressure in coastal areas has led to the loss and deterioration of mangrove habitats, and an increase in salt ponds, which have a negative impact on the genetic diversity and genetic structure of Littorinid snails.

Benthic deep-sea environments are the largest ecosystem on earth. Benthic deep-sea microbes are therefore key drivers of organic matter -remineralisation and nutrient regeneration, influencing biogeochemical cycles and carbon-sink capacity. What impact could climate change have on this special ecosystem?

Widespread industrialization of the past 300 years has resulted in increased metal pollution from mining, manufacturing, and disposal operations. Seawater contains all naturally occurring metals and the impacts of metal pollution are usually restricted to near the sources. Some metals, however, are highly toxic and can accumulate up food chains, thus concentrating effects by the time humans consume the species, such as mercury building up in tuna. Many reef-dwelling species are used as monitors for toxic metals, and it is commonplace to find ‘hot-spots’ of metal pollution in the vicinity of industrial areas.

Scientists have found that there have been significant changes to jellyfish populations over the last 50 years due to climate change.

What are the key challenges in understanding marine socio-ecological systems and how can we attempt to predict the future impacts on these vital environments?

While nations are responsible for maintaining their shorelines, much of the ocean is left unregulated. Litter, particularly plastics, has been found in far reaches of the ocean, even in the depths of the Mariana Trench. New regulation from the UN aim to decrease the damage to marine ecosystems caused by human activities.

Controls of industrial wastes have been successful in halting and even reversing some deleterious trends in some regions (such as the Black Sea, Mediterranean, North Sea, and Chesapeake Bay), and most sea areas are now subject to some degree of international agreement for implementing management regimes, however, the degree of effectiveness varies.

The current geologic period is referred to as the Anthropocene, which stresses the great anthropogenic pressure on the Earth’s atmosphere, geology, and biological diversity, and in the face of threats such as habitat loss, pollution, and expansion, it is easy to feel discouraged. But could the Anthropocene in fact be seen as a good thing, balancing the preservation of the natural world with realistic societal needs and consumption? It is suggested that this optimistic approach is far more effective at galvanizing the general public into action, and encouraging young researchers to move into professional careers in conservation biology than the ‘doom and gloom’ perspective focused on so often.

We hope you’ve enjoyed exploring this fantastic series with us – you can catch up with any posts you may have missed throughout the series below:

Episode 1: One Ocean

Episode 2: The Deep

Episode 3: Coral Reefs

Episode 4: Big Blue

Episode 5: Green Seas

Episode 6: Coasts

Featured image credit: Panorama by pixexid. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Our Blue Planet appeared first on OUPblog.

The problem of colour

Colours are a familiar and important feature of our experience of the world. Colours help us to distinguish and identify things in our environment: for instance, the red of a berry not only helps us to see the berry against the green foliage, but it also allows us to identify it as a berry. Colours perform a wide variety of symbolic functions: red means stop, green means go, white means surrender. They have distinctive personal and cultural associations, and provoke a range of emotional and aesthetic responses that are reflected in the clothes we wear, the way we decorate our houses, and the choices made by designers and artists.

But although colours are a familiar feature of the world that we perceive, they are also deeply puzzling. What exactly are colours? Do colours even exist?

Colours appear to be properties of things in our environment: apples, clothes, cats, coffee, traffic lights, and so on. Moreover, it is natural to think of them as “objective” properties of things, that exist independently of our experience of them—properties, like shape, that do not exist just because we see them, and so which would exist even if there were no-one around to see them. In part, this is because colours, like shapes, exhibit “perceptual constancy”: they appear to remain constant throughout changes in the conditions in which they are perceived. If you turn on a desk lamp in an already illuminated room, the colours of the things that the lamp illuminates don’t normally appear to change, just as the shape of a table doesn’t normally appear to vary as you view it from different angles.

However, philosophers and scientists have long thought that colours are not what they seem. There are two main reasons for this.

First, there are widespread, and often dramatic, variations in colour perception. Amongst humans there are various forms of colour-blindness; and even otherwise “normal” perceivers often disagree in the identification of so-called “unique hues”: “pure” instances of red, yellow, blue, and particularly green. Variations in colour experience between members of different species appear to be even more pronounced. Humans are typically sensitive to light with a wavelength of between 400-700 nanometers, and have three types of photoreceptors in their eyes. Other species, however, are sensitive to light of different spectral wavelengths, and differ in the number of types of photoreceptor that they have in their eyes. For instance, pigeons and turtles are sensitive to light in both the ultra-violet and the infra-red regions of the electromagnetic spectrum; and whereas many mammals only have two types of photoreceptor, pigeons and goldfish have four types of photoreceptor, some butterflies have at least five types of photoreceptor, and mantis shrimp appear to have at least twelve. These differences are presumably associated with differences in the way that these creatures perceive colour.

Differences in colour experience between perceivers and across conditions present a problem for the view that colours, like shapes, are “objective” properties of things in our environment. If colours are “objective” properties of things that exist independently of our experience of them, then which perceivers, in which conditions, get it right? To say that humans correctly perceive the colours of things may seem chauvinistic—and besides, which humans are we talking about here?

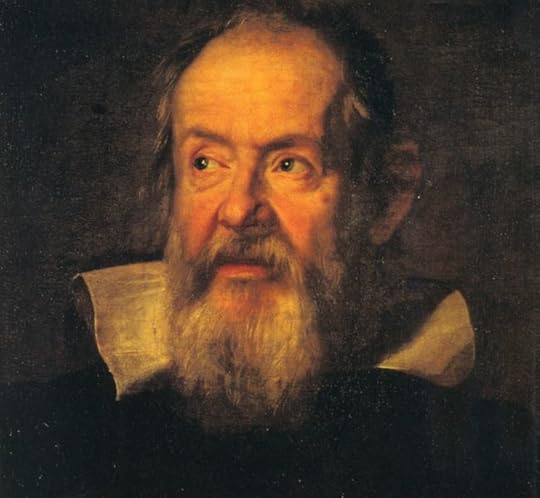

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The second problem that has led many philosophers and scientists to conclude that colours aren’t really as they appear concerns the relationship between colours and the physical properties of coloured objects. Since the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, many have concluded that science “tells us” that physical objects are not really coloured, or at least not in the way we normally suppose. Writing in 1623, for example, Galileo claimed that colours are “no more than mere names so far as the object in which we place them is concerned … they reside only in consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated” (The Assayer). Modern scientific theories do not explain experiences of colour by appealing to the colours of objects, but instead in terms of objects’ dispositions to reflect, refract, or emit light across different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. The conclusion that many have drawn is that we either need to identify colours with the physical properties of things that cause our colour experiences, or admit—like Galileo—that colours do not exist.

But can this really be right? Focus on a colour in your immediate environment and ask yourself whether that could really be only a figment of your mind, or at best radically different from the way it appears. Moreover, colour is arguably only the thin end of the wedge. One of the reasons why colours are philosophically interesting is that they provide an illustration of general problems that arise in thinking about the “manifest image” of the world, or the world as it appears to us as conscious subjects. It is not just colours that are under threat. Similar problems arise for aesthetic properties like beauty, for moral properties like right and wrong—even for what philosophers have traditionally called “primary qualities” like shape and size. Could the world really be so radically different from the way that it appears? If we want to hold on to the familiar world of experience, then we need to look again at colour.

Featured image credit: Altarpiece, No. 1, Group X, Altarpieces by Hilma af Klint. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The problem of colour appeared first on OUPblog.

December 9, 2017

Five favorite “Rainbows”

“Over the Rainbow,” voted the greatest song of the twentieth century in a survey from the year 2000, has been recorded thousands of times since Judy Garland introduced it in The Wizard of Oz in 1939. Even the most diehard fans, including myself, are unlikely to have listened to every version. But five stand out, each distinctive and compelling in its own way.

1. Judy Garland’s soundtrack recording, which was made in MGM studios in October 1938, will always be the touchstone. Only sixteen years old, Garland sang with a maturity that belied her years. She combined purity of tone with a sophisticated approach to the shaping and coloring of the song’s words and melody. Garland performs the first phrase on a single breath, as a continuous arc, like the rainbow about which she sings. In the final segment of the song, (“If happy little bluebirds fly. . .”), she sings at first in a regular rhythm, then almost as if in prayer slows the melody and thins her voice as she rises to the high note on “why oh why can’t I?” Garland’s performance, at once reserved and radiant, captures the distinctive blend of anxiety and hope, of concern and optimism that lie at the core of Dorothy’s character.

Garland sang “Over the Rainbow” throughout her career. As she herself admitted, it became her “theme song.” For Garland and her fans, it seemed to embody her struggles with—and efforts to rise above—substance abuse, depression, weight problems, hospitalizations, failed marriages, custody battles, and financial difficulties.

2. No version of “Over the Rainbow” captures this transition from the fictional Dorothy to the real-life Garland better than her 1955 recording for the Capitol album Miss Show Business. Garland’s voice has darkened and taken on more texture—more “baggage.” The tempo is slower than in 1938, and her approach to rhythm is more fluid and nuanced. There is more of what we might call psychological realism. Garland divides the opening phrase in two, with a short glottal stop after “Somewhere.” It is as if she first feels the desire to escape and only then imagines where she might go. In the final “why oh why can’t I?” Garland pauses on each word, almost sobbing. What in 1938 made for a wistful ending now becomes a wrenching existential plea for salvation.

Many singers steered clear of “Over the Rainbow.” Barbra Streisand calls “Over the Rainbow” “one of the finest songs ever written” but says she resisted singing it “because it’s identified with one of the greatest singers who ever lived.” Among many post-Garland singers (including Streisand) who did overcome hesitation to record “Over the Rainbow,” three offer very distinctive approaches to the song.

3. The composer himself, Harold Arlen, was a superb pianist and singer with a lovely tenor voice. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Arlen made commercial recordings with several important bands and even contemplated a career as a vocalist. In later years, Arlen was featured as a singer on a number of discs of his own music, including a Capitol album in 1955, Harold Arlen and His Songs. For “Over the Rainbow,” Arlen accompanies himself on piano in the introductory verse, a part of the song rarely performed (even by Garland). He then continues with the chorus as the orchestra enters with a small-scale, softly swung arrangement by the incomparable Peter Matz. Arlen takes an intimate, almost conversational approach to “Over the Rainbow.” It is as though he is revisiting an old, beloved friend—in this case his most famous song. Arlen floats his high F beautifully on “find” of “where you’ll find me.” Arlen’s singing of “Over the Rainbow” is at once elegant, technically secures, and deeply engaged, just like the songs written by this great American master.

4. Eva Cassidy, who died tragically of a melanoma at 33 in 1996, was one of the most talented singers of her generation, working at the intersection of pop, folk, country, and jazz styles. Accompanying herself on steel-stringed acoustic guitar in a performance captured on video at the Blues Alley club in Georgetown in 1996, Cassidy sings “Over the Rainbow” slowly and reflectively, but with a directness that is at once clean and highly expressive. In the New York Times in 2002, Alex Ward characterized Cassidy in words that perfectly capture her performance of “Over the Rainbow”: “a silken soprano voice with a wide and seemingly effortless range, unerring pitch and a gift for phrasing that at times was heart-stoppingly eloquent.”

5. By far the best-known version of “Over the Rainbow” today is the one released in 1993 by the Hawaiian singer Israel Kamakawiwo’ole (known as IZ) as part of a medley with “What a Wonderful World.” IZ freely recasts the lyrics—a practice some critics have called “Israelizing”— and sings the tune in his ethereally beautiful tenor voice, accompanying himself on the ukulele. His song “Rainbow” and “World” have now sold millions of digital copies and spent over 400 record-breaking weeks at or near the top of the Billboard World Digital Songs chart. The “Rainbow” portion has appeared in numerous commercials (promoting the Norwegian lottery, Dutch health insurance, Austrian sugar, Korean cosmetics, and AT&T cellular services), in television series (ER and Glee), and in films (Meet Joe Black, Finding Forrester). With IZ’s version, “Over the Rainbow” has been recast—deservedly and in an appealing performance—as a global hit.

Featured image: “Streamers” by Nicholas A. Tonelli. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Five favorite “Rainbows” appeared first on OUPblog.

The philosopher of Palo Alto

Apple’s recent product launch on 12 September has cast into the mainstream technologies that were first envisioned by Mark Weiser in the 1990s, when he was Chief Technologist at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Though Weiser died in 1999, at the age of 46, his ideas continue to inspire cutting-edge smartphone innovations. The release of Apple’s new iPhones and operating system this Fall signals a new stage in the tech industry’s commitment to making Weiser’s vision a mass market reality. Now is a good time to revisit Weiser’s ideas; his work foreshadows how our smartphones and the ways we use them may soon change.

Weiser’s pivotal role in sparking the post-desktop revolution owed much to his humble beginnings as a dropout philosophy student. (He later became a tenured professor of computer science without ever obtaining an undergraduate degree.) The three semesters Weiser spent at New College of Florida paint him as an east coast Steve Jobs, and there is much to glean from the comparison. Both were “humanities kids” of the shaggy hair variety. Around the same year Jobs sat in on calligraphy courses, Weiser penned term papers on Plato, Wittgenstein, and Heidegger. Both men went on to preach liberal arts virtues to the Silicon Valley engineers they would lead.

Their respective roadmaps for future mobile devices, however, proceeded in very different directions. While Jobs’ push to expand the digital world ad infinitum effectively defined the past decade of handheld computers, the 10th anniversary smartphones this year is paying homage to Weiser and his mission to integrate the content of the Internet with the everyday settings and locales we each inhabit here and now.

The disparate ways in which we use our mobile devices today owe much to these lasting tensions between Weiser’s philosophical ideals and Job’s design strategies. A nearly universal selling point that has spurred the rise of smartphones (and the decline of desktops) is the utter convenience of handheld hardware. Smaller form factors allow people to use computers on the go. But to what ends?

For Jobs, portable screens represented new avenues to expand the Apple universe his users had already grown to love on their stationary machines. A document created on one’s iMac carries over to one’s iPad and MacBook, via iCloud. The iPhone works hand in glove with Apple TV and Apple Watch. Job’s quasi-monopolistic insistence on “end-to-end control” bequeaths a parallel level of command to his customers in this multi-device context. If you buy into Apple across the board, then the stuff of your desktop becomes available on-demand, anytime, anywhere.

The disparate ways in which we use our mobile devices today owe much to these lasting tensions between Weiser’s philosophical ideals and Job’s design strategies.

Weiser foresaw this scenario, and he wanted little part of it. He believed that mobile interfaces and the cloud marked an opportunity to reinvent computing beyond the desktop—not to enlarge the purview of desktops. This was an odd view to hold at Xerox PARC. Desktops were more or less invented at PARC before Weiser joined the Palo Alto-based lab in 1987. Publishing articles with titles like “The Computer for the 21st Century” and “The World is Not a Desktop,” he quickly inspired his R&D colleagues to make a 180-degree turn.

During the 1990s, under the banner of ‘ubiquitous computing’, Weiser and his team prototyped entirely new categories of handheld, wearable, and embedded devices designed to “draw computers out of their electronic shells” and bring the virtuality of computation “into the physical world.” Weiser drew motivation from what he took to be the desktop’s tragic flaw. Users had to put their lives on pause in order to use it. Engaging with a PC meant disengaging from everything else. He predicted that, as people spent more time on the web in more places, the gap between our screens and our surroundings would only widen. Online chatrooms of the 90s would give way to checking Facebook while driving. If we continued to see mobile devices as tiny PCs, then our attention would be pulled increasingly in multiple directions every minute. And so, long before phones became smart, Weiser staked out his holy grail: “Could I design a radically new kind of computer that could more deeply participate in the world of people?”

So many innovations that will likely define the next decade derive, at least in part, from an odd lineage of old technologies (e.g., eyeglasses, white canes, candy wrappers) that sparked Weiser’s ideas twenty-five years ago. For example: “Eyeglasses are a good tool—you look at the world, not the eyeglasses. The blind man tapping the cane feels the street, not the cane.” Like the blind man’s cane, ubiquitous computing operates through movement and contact; both afford their beholders a mode of knowledge that is utterly dependent upon environmental input. The cane without the street is just an expensive stick. A mobile device without contextual awareness is a cheaper desktop. Candy wrappers and streets signs, too, play surprising roles in Weiser’s thought. These embedded texts envelop the objects and settings that comprise our public spaces. Through them, we read our way through the world at a glance. They are the cultural infrastructure of habit and habitus. To Weiser, candy wrappers and the like represented “the real power of literacy,” and he pioneered early efforts that brought to computing this same sense of reciprocity between texts and environments.

Good tools, in light of Weiser’s legacy, are not just extensions of one’s mind or body. More profoundly, technologies at their best may serve as liaisons, linking each of us to subtleties in the dynamic, singular, living patch of earth we inhabit right now. The apex of Weiser’s prescient ambitions are still ahead of us, unreached. We have hit a point, though, where almost every “next big thing” in tech builds on his early blueprints. With each new app inspired by Pokémon Go and every 9-figure investment in startups like Magic Leap, mobile and wearable interface stand to become a little less like miniaturized desktops and a bit more like a digital looking glass we point toward the world around us.

Featured image credit: smartphone movie taking pictures by SplitShire. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post The philosopher of Palo Alto appeared first on OUPblog.

Why physicists need philosophy

At a party, on a plane, in the locker-room, I’m often asked what I do. Though tempted by one colleague’s adoption of the identity of a steam-pipe fitter, I admit I am a professor of philosophy. If that doesn’t end or redirect the conversation, my questioner may continue by raising some current moral or political issue, or asking for my favorite philosopher. The reply “No, I’m not that kind of philosopher, my field is the philosophy of physics” typically induces silence as my interlocutor peers into the chasm separating C.P. Snow’s two cultures while I go on about how Einstein changed basic beliefs about space and time.

But now I have to be ready for a different response. “How can philosophers add anything to what physicists have been able to achieve without them? Richard Feynman made fun of philosophy, Steven Weinberg finds it useless, Neil de Grasse Tyson thinks it’s a waste of time, and Larry Krauss and Stephen Hawking say physics has answered big questions about our place in the universe that philosophers used to ask in ways contemporary philosophers simply can’t follow.” This response is a simple appeal to authority, based on scientific eminence, and lately on success in reaching a receptive mass market through popular books and TV shows. But expertise in one field is often not transferable to another, and popular science presentations are often more entertaining than enlightening.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking last year presented a six-episode series of TV programs entitled “Genius.” With jazzy production technique, the series aimed to convince viewers of reality TV shows that they can reach the same answers to big questions as contemporary physicists. Hawking is notorious for his 2011 claim that philosophy is dead, so it is not surprising that his consultant “experts” included no philosopher. A pity: a little philosophical expertise could have provided the balance and coherence the series lacked.

Take the episode “Why are we here?” A medieval Christian would say “To serve God and seek salvation”: the US Declaration of Independence suggests an alternative purpose: the pursuit of happiness. Both count as reasons for being here, though neither offers the answer toward which the episode’s three “ordinary” participants are guided. The episode suggests two kinds of scientific explanations about why we’re here before settling on a third.

First, Laplacean determinism: every last detail of the present state of the universe (including the motions of our brains and bodies) is determined by its earlier state. This is deemed incompatible with our ability to freely choose what to do, with no mention of the long philosophical tradition of compatibilism (see my colleague Jenann Ismael’s recent book How Physics Makes Us Free.)

Second, quantum indeterminism, illustrated by the selective bombardment of our hapless trio triggered by random radioactive decay. Whether this would be any more compatible with free choice than determinism is not addressed.

So why are we here? Hawking professes his belief that understanding quantum theory requires acceptance of many worlds, (some) containing a different version of each of us. Our trio of participants joins an elaborate visual display of free choices by multiple actors, each wearing a face mask matching one of the participants. Initially the actors all line up behind the participant whose mask they wear. When alerted each chooses to step to one side or the other, progressively spreading the lines. Everyone in an initial line is a metaphor for a version of the same person: their position in line corresponds to the world they’re in.

What should we conclude? If their movements mimic the results of random quantum events, then in what sense are they freely chosen? If not, then how does the existence of many worlds help make the free choice of a person in any of them any more compatible with quantum physics? (The moral is supposed to be “I’m here because I’m in my world through my own previous free choices.”)

Hawking may believe there are many worlds, but plenty of physicists, mathematicians, and philosophers don’t. There is no consensus on how quantum theory should be understood. I doubt that most experts share Hawking’s belief. Behind a façade of experimental demonstration, the episode “Why are we here?” hides an appeal to authority. What is needed is the convincing argument that it is the job of the philosopher to provide.

Featured image credit: Provided by the author and used with permission.

The post Why physicists need philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers