The problem of colour

Colours are a familiar and important feature of our experience of the world. Colours help us to distinguish and identify things in our environment: for instance, the red of a berry not only helps us to see the berry against the green foliage, but it also allows us to identify it as a berry. Colours perform a wide variety of symbolic functions: red means stop, green means go, white means surrender. They have distinctive personal and cultural associations, and provoke a range of emotional and aesthetic responses that are reflected in the clothes we wear, the way we decorate our houses, and the choices made by designers and artists.

But although colours are a familiar feature of the world that we perceive, they are also deeply puzzling. What exactly are colours? Do colours even exist?

Colours appear to be properties of things in our environment: apples, clothes, cats, coffee, traffic lights, and so on. Moreover, it is natural to think of them as “objective” properties of things, that exist independently of our experience of them—properties, like shape, that do not exist just because we see them, and so which would exist even if there were no-one around to see them. In part, this is because colours, like shapes, exhibit “perceptual constancy”: they appear to remain constant throughout changes in the conditions in which they are perceived. If you turn on a desk lamp in an already illuminated room, the colours of the things that the lamp illuminates don’t normally appear to change, just as the shape of a table doesn’t normally appear to vary as you view it from different angles.

However, philosophers and scientists have long thought that colours are not what they seem. There are two main reasons for this.

First, there are widespread, and often dramatic, variations in colour perception. Amongst humans there are various forms of colour-blindness; and even otherwise “normal” perceivers often disagree in the identification of so-called “unique hues”: “pure” instances of red, yellow, blue, and particularly green. Variations in colour experience between members of different species appear to be even more pronounced. Humans are typically sensitive to light with a wavelength of between 400-700 nanometers, and have three types of photoreceptors in their eyes. Other species, however, are sensitive to light of different spectral wavelengths, and differ in the number of types of photoreceptor that they have in their eyes. For instance, pigeons and turtles are sensitive to light in both the ultra-violet and the infra-red regions of the electromagnetic spectrum; and whereas many mammals only have two types of photoreceptor, pigeons and goldfish have four types of photoreceptor, some butterflies have at least five types of photoreceptor, and mantis shrimp appear to have at least twelve. These differences are presumably associated with differences in the way that these creatures perceive colour.

Differences in colour experience between perceivers and across conditions present a problem for the view that colours, like shapes, are “objective” properties of things in our environment. If colours are “objective” properties of things that exist independently of our experience of them, then which perceivers, in which conditions, get it right? To say that humans correctly perceive the colours of things may seem chauvinistic—and besides, which humans are we talking about here?

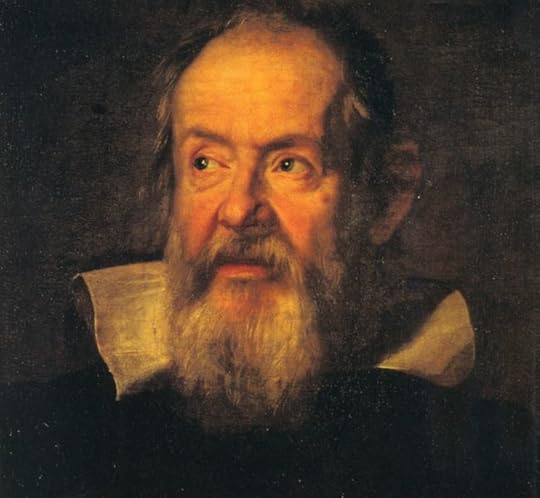

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Galileo Galilei by Justus Sustermans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The second problem that has led many philosophers and scientists to conclude that colours aren’t really as they appear concerns the relationship between colours and the physical properties of coloured objects. Since the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, many have concluded that science “tells us” that physical objects are not really coloured, or at least not in the way we normally suppose. Writing in 1623, for example, Galileo claimed that colours are “no more than mere names so far as the object in which we place them is concerned … they reside only in consciousness. Hence if the living creature were removed, all these qualities would be wiped away and annihilated” (The Assayer). Modern scientific theories do not explain experiences of colour by appealing to the colours of objects, but instead in terms of objects’ dispositions to reflect, refract, or emit light across different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. The conclusion that many have drawn is that we either need to identify colours with the physical properties of things that cause our colour experiences, or admit—like Galileo—that colours do not exist.

But can this really be right? Focus on a colour in your immediate environment and ask yourself whether that could really be only a figment of your mind, or at best radically different from the way it appears. Moreover, colour is arguably only the thin end of the wedge. One of the reasons why colours are philosophically interesting is that they provide an illustration of general problems that arise in thinking about the “manifest image” of the world, or the world as it appears to us as conscious subjects. It is not just colours that are under threat. Similar problems arise for aesthetic properties like beauty, for moral properties like right and wrong—even for what philosophers have traditionally called “primary qualities” like shape and size. Could the world really be so radically different from the way that it appears? If we want to hold on to the familiar world of experience, then we need to look again at colour.

Featured image credit: Altarpiece, No. 1, Group X, Altarpieces by Hilma af Klint. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The problem of colour appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers