Julia Robb's Blog, page 7

September 19, 2014

Paulette Jiles Sings A Mountain Song

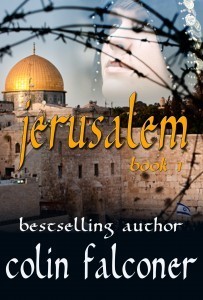

Readers, I love and admire

Enemy Women

, the 2002 novel by Paulette Jiles. Ms. Jiles has written books of poetry, a memoir (

Cousins

) and three other novels, but

Enemy Women

is my favorite.

Readers, I love and admire

Enemy Women

, the 2002 novel by Paulette Jiles. Ms. Jiles has written books of poetry, a memoir (

Cousins

) and three other novels, but

Enemy Women

is my favorite.It’s about a young woman, Adair Colley, who lives in the Missouri Ozarks during the Civil War, and the events which destroy her family, her farm and most of her neighbors and friends.

The Union militia is butchering and burning the Ozarks and jails Adair and dozens of other Missouri women in a St. Louis prison, demanding information about Confederate guerillas.

But Adair and her interrogator fall in love and agree to meet after the war.

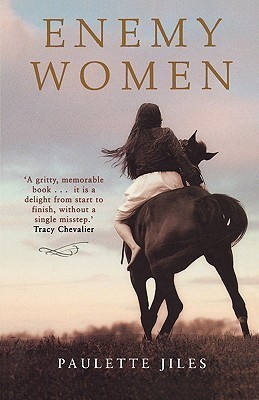

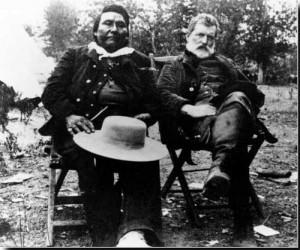

Jiles

Major William Neumann then arranges Adair’s escape and she starts for home.

I admired this book for its riveting story, for its beautiful descriptions, and for the way it shows readers exactly what the Ozarks were like in 1864.

I also love the way the novel sings to us and that song is a mountain song; the Ozarks’ blue folding ridges, its culture, its poetry and its people.

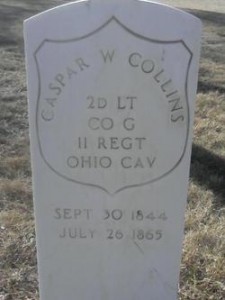

Thomas Moody, 11th Missouri State Militia Cavalry.

Hi Paulette Jiles: Thanks for talking to me.

You got excellent reviews for Enemy Women , but most of them never mentioned one of the novel’s most interesting characteristics.

The Missouri Union militia was revealed as murderous and criminal (murdering civilians, among other things, and stealing everything that wasn’t nailed down) while Confederate Col. Timothy Reeves and his men (State Guard 15th Cavalry Regiment) were portrayed in a sympathetic light.

The Militia also helped drag dozens of Missouri women to prison.

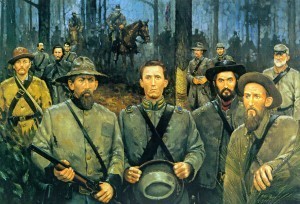

Col. Timothy Reeves

Q. Did you think it was odd reviewers didn’t mention your historic point of view?

A. That’s true. Very few reviewers mentioned it. That is, in the major papers like the New York Times. However it did cause a bit of a storm in southeastern Missouri where these old conflicts are still being re-fought, apparently.

The storm was among local historians. I won’t go into it. It’s too tedious. But there was mini-lightning and mini-thunder.

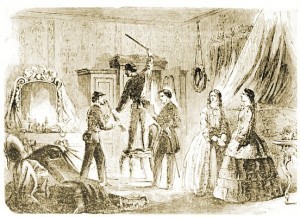

Harper’s Weekly’s 1861 version of Federal soldiers searching the home of rebellious Southern women for incriminating weapons and letters.

Q. Did jailing the women actually help the Union destroy the guerrillas?

A. It’s impossible to know, but I don’t believe it did.

The real reason for imprisoning the women was to deny the rebels and/or the local Confederate-sympathizing home guard their commissary.

The women were their supply and their unofficial quartermaster department.

By throwing them in prison, the local Confederates would be denied supplies.

But it didn’t seem to have worked that way. (The guerrillas) got supplies anyway.

Rebs wearing their butternut uniforms

Thus the familiar ‘butternut’ uniforms instead of gray because the uniforms were home-made with home-made dyes.

The important thing about having proper uniforms was that General Halleck, of the St. Louis Union command, had published an order stating that anyone found not wearing a uniform was to be considered an outlaw and shot without trial.

Union troops executing Confederate guerrillas.

Q. How did you become interested in the history of the Missouri Ozarks?

A. I was raised there.

Missouri quilt

Q. At the end of the book, although Adair and Major Neumann manage to reunite, the future looks grim.

Did Adair recover from consumption and did the major recover from his injured hand?

Missouri Ozarks

A. Yes for both. TB is something one can live with. Many people had long lives despite TB.

So Adair is young and strong and so we hope for a long life for her.

The Major’s hand injury was not very serious or crippling.

Q. Did you really look at tintypes of St. Louis, made during the Civil War era, and use them to describe the historic city?

Q. Did you really look at tintypes of St. Louis, made during the Civil War era, and use them to describe the historic city?A. Yes, it was the most amazing fun thing.

Between two coffee-table-sized books, Likeness And Landscape; Thomas M. Easterly and the Art of The Daguerrotype and Saint Louis Illustrated; Nineteenth Century Engravings and Lithographs of a Mississippi River Metropolis I could trace Adair’s escape from the city almost block by block.

Levee during the 1860’s

For instance there is a Daguerrotype of the St. Louis levee in 1853, not so different from 1865, at the foot of Poplar Street,

Also, a view of Fourth Street south from Olive Street, taken in 1866 with big advertisements for pianos and an engraving establishment.

I found a Daguerrotype of an inn at Eleventh and Locust, which was where the Major was staying. At that time it was at the edge of the city.

I enjoyed it enormously.

Then in St. Louis Illustrated , there’s the Compton and Dry map of about 1870 shows you where Fourth and Olive was and where Adair would go from there to get to the levee and so on.

Q. Did you base the cures suggested by the “botanical steam doctor” on a real steam doctor and his methods?

A. Yes, this was from a book written by Dr. Gideon Lincecum, who journeyed through Texas in the 1840’s.

He was a self-taught biologist and physician. He discusses the controversy at that time between ‘steam doctors’ who tried to cure by natural herbs, and the more traditional doctors who used a great deal of heavy chemicals and drugs like mercury, sugar of lead, etc.

Q. The readers’ guide provided by the publishing company suggested you used the description of the moon, on the novel’s last pages, to imply hope for Adair and the major.

Did you insert the moon as a symbol of hope, or was the publishing company just throwing something out there?

A. Throwing something out there.

But I use the phases of the moon a lot in my writing. It marks the passage of time, it is beautiful and apparently erratic (note where it rises on the horizon, this changes very quickly but in a very long cycle).

Many different cultures have seen different things in (moon) markings.

Q. I adored the “confessions” Adair wrote. I suspected those were written in an intuitive stream-of-consciousness, at least on the first draft. Were they?

Q. I adored the “confessions” Adair wrote. I suspected those were written in an intuitive stream-of-consciousness, at least on the first draft. Were they?A. Yes, they were. She has in her head quite a lot of phrases and symbols from her folk culture (my folk culture) that come readily to mind.

Q. You have been referred to as Canadian because you spent eight years living in Canada. But you grew up in the Ozarks and live near San Antonio.

Do you consider yourself Canadian?

Ojibwe

A. Not really, but kind of.

Hard to say. I spent formative years there working with the Ojibwe people in the Canadian north, and there was first recognized as a poet and I have a following there and many dear friends.

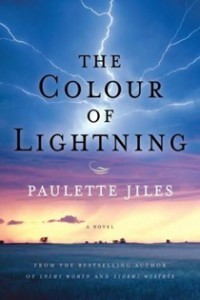

Q. In The Color of Lightning Britt Johnson, a former slave, searches for his wife and children on the Texas frontier: Comanches have kidnapped his family. (Readers, this really happened).

How did you become interested in Britt’s story?

A. I was thinking of doing a sequel to Enemy Women and was researching Texas in the 1860’s to see where they might have gone, to start over, and read Lone Star, Fehrenbach’s history, and came upon his story.

I found it both sad and upsetting that Britt Johnson’s story had not been told in fiction. Or non-fiction for that matter.

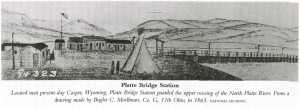

A few yards from the spot Britt Johnson was killed by Comanches

Q. One of your protagonists in Lightning is a Quaker, in charge of the Fort Sill (Comanche/Kiowa) Indian reservation.

(This also really happened. The government put the Quakers in charge of the reservations, at least for a time).

After researching the Quaker era, did you draw a conclusion about the policy?

A. Well, yes, the same conclusion that everyone else finally came to, which is that it was basically really stupid.

But then again, there was nothing that would ‘work’, that is, a policy that was kind, generous, and in which the Comanche and the Kiowa would be amenable to friendly persuasion.

They were warriors. They had been warriors for about 40,000 years.

Q. What are you working on?

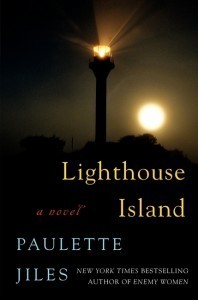

Readers, Paulette’s last book was Lighthouse Island , a dystopian novel (meaning civilization as we know it has been destroyed).

A. Dystopian fiction. I am having a lot of fun with a future dystopia in which bureaucracies have finally absorbed all of human endeavor and are completely incompetent in supplying human needs.

The majority of people live in third-world conditions, and then there are always the elites.

The majority of people live in third-world conditions, and then there are always the elites. And the people living in the vast city-slums are in reality far more interesting, vital, funny and lively than the buttoned-up elite.

The city-slums were much more fun to write about.

They are ruled by various local Big Men and there are open-air black-markets, etc. completely sub rosa and below the view of the controlling elites.

What engaged me as a writer was that in #1 ( Lighthouse Island ), Our Heroine is an evader. She uses deception, forgery and the impersonation of officials to escape. This makes her funny and lively.

But even better and more challenging was #2, in which Our Hero is a fighter. This brought about a whole new set of fictional opportunities.

Different things happen. He is of the elites, but is thrown out of his privileged world into the slums. He has to survive. He does quite well.

Of course if you are 6’4” and have had fight training you would probably do okay.

Of course if you are 6’4” and have had fight training you would probably do okay. But this was a very different kind of writing. Very different. I really enjoyed learning how to do it.

The temptation is ever before us to have our protagonist shrink back, evade confrontation. It seems more ‘intelligent.’

And people who are fighters tend to be regarded as dim.

But in actuality, having a pro-active main character leads to a whole other writing discipline.

I learned much that was new to me but old, I know, to others.

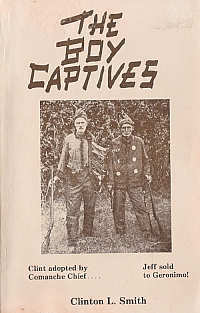

I learned much that was new to me but old, I know, to others.And then I have also completed a short novel about a girl who was a captive of the Kiowa.

I looked at the intriguing question of the white captives of the Comanche/Kiowa and the changes in self; in who they thought they were, who their white relatives thought they were.

That has puzzled me ever since I wrote The Color of Lightning .

Former Kiowa captive Millie Durgan

Thank you for having me on your blog Julia.

The post Paulette Jiles Sings A Mountain Song appeared first on .

September 6, 2014

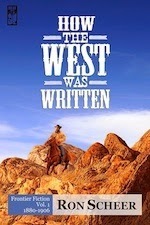

Ron Scheer: HOW THE WEST WAS WRITTEN

This is “How The West was Written,” said Ron Scheer, from violent to free from Eastern social structures, to egalitarian, with a democratic spirit.

Hi Ron Scheer: Thanks for talking to me.

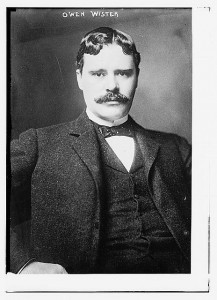

Readers, Ron runs Buddies in the Saddle, or buddiesinthesaddle.blogspot.com, where he reviews Western books and movies, specializing in books published between 1880 and 1915.

He also reviews (mostly) older Western movies.

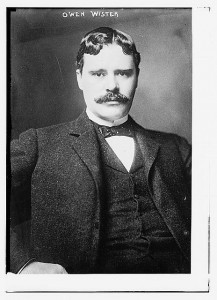

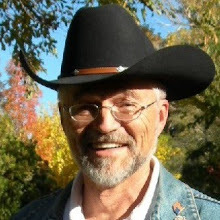

Ron Scheer

Ron also publishes lists of words he’s gathered from the books, almost all of which vanished with the frontier.

This year, Ron published How The West Was Written, examining how writers have historically presented the West.

(Readers: full disclosure. I commented on Ron’s book in early draft forms and he was kind enough to mention me, and others, in a forward to the published edition).

Q. Ron, can you tell us about the various ways authors have presented the West?

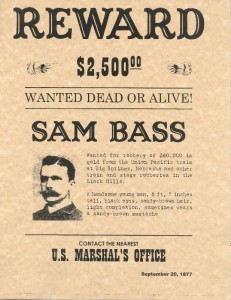

A. From the beginning, there were many Wests, some actual, some mythical. In the dime novels of the 19th century, it was a wild terrain populated by hostile tribes and outlaws, well suited in fiction for action and adventure.

A. From the beginning, there were many Wests, some actual, some mythical. In the dime novels of the 19th century, it was a wild terrain populated by hostile tribes and outlaws, well suited in fiction for action and adventure.But as the frontier became a setting for mainstream fiction, it took on other associations.

(Authors) described freedom and independence from the rigid social structures and crowded living conditions of the East.

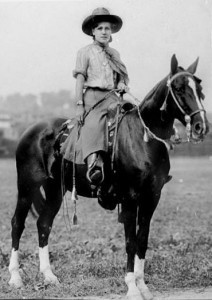

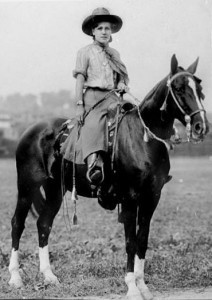

Freedom from social constraints was especially true for women

(they wrote), who could dress more informally, ride astride a horse rather than sidesaddle, and use firearms.

(they wrote), who could dress more informally, ride astride a horse rather than sidesaddle, and use firearms.The egalitarian, democratic spirit of frontier settlements also allowed for a degree of social mixing frowned on elsewhere.

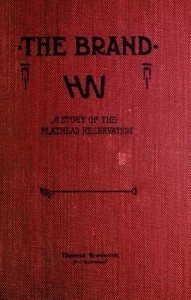

The young heroine of Therese Broderick’s The Brand (1909), newly arrived in Montana, is enraptured by the promise of “untrammeled freedom” and will hear nothing of “don’ts and can’ts.”

The young heroine of Therese Broderick’s The Brand (1909), newly arrived in Montana, is enraptured by the promise of “untrammeled freedom” and will hear nothing of “don’ts and can’ts.”Women writers often voiced strongly feminist views. Some actively supported the temperance movement, which eventually led to the closing of the saloons and Prohibition.

Several writers were advocates of social reform and even identified as Socialists. In their novels, they decried the corruptive dominance of a robber-baron economy, which flourished in the West.

(Also authors wrote about) a healthful climate, especially for those with pulmonary afflictions, like TB; a land of opportunity, where homesteading made land ownership within the reach of so many; and a place to get rich quick through exploitation of natural resources, monopolies of services like railroads, and mining for gold and silver.

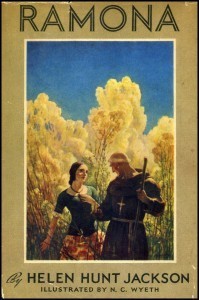

An 1884 novel about the plight of California’s Indians.

Q. It seems many more women wrote Westerns in the past. Is that’s so, why aren’t women writing westerns like they used to do?

A. Women writers contributed generously to the outpouring of frontier fiction a century ago. But they were far less likely to write cowboy westerns.

B. M. Bower (Chip of the Flying U, 1906) is an exception.

And even her novel is more properly a ranch romance. It doesn’t venture into the male world of saloons, gunfights, outlaws, and the outdoors.

Miss Bower

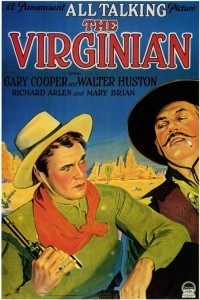

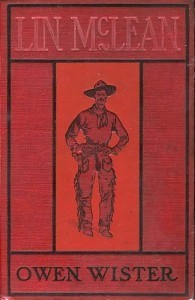

Owen Wister was able to straddle both worlds of action and romance in The Virginian (1902), but the two strands have remained largely separated along a gender divide ever since.

Look at the cover art for most western-themed fiction today. It’s

either a fully dressed cowboy firing six-guns or a shirtless one who looks like he spends most of the day at the gym.

either a fully dressed cowboy firing six-guns or a shirtless one who looks like he spends most of the day at the gym.Q. Many Westerns have been highly influential in American culture; can you tell us about them?

A. If we’re talking books, it’s been argued that Owen Wister’s The Virginian had the biggest impact on how Americans imagined, understood, and were excited by the West—as much as by Bill Cody’s traveling Wild West show.

The book was the no. 1 bestseller for the year it was published and appeared again on the same top-10 list the following year.

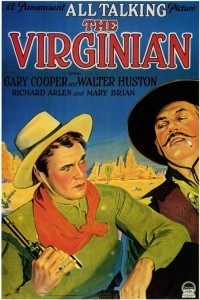

The book was the no. 1 bestseller for the year it was published and appeared again on the same top-10 list the following year. It was made into a hugely successful stage play and adapted to film several times, not to mention providing a cast of characters for one of the longest-running western series on TV.

As for the influence of western movies, I’d name the cowboy actors who portrayed most vividly an ideal of manhood, probably starting with Tom Mix and ending with John Wayne.

Q. If you had to recommend one Western book for readers (published between 1880 and 1915), what would it be and why?

A. It would have to be The Virginian, for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. Plus the fact that it’s enjoyable to read.

Wister was writing from personal experience of the West. He had both a good eye for authentic detail and a sense of humor—neither of which a reader is likely to find in Zane Grey.

Wister was writing from personal experience of the West. He had both a good eye for authentic detail and a sense of humor—neither of which a reader is likely to find in Zane Grey.The Virginian was the first romantic cowboy hero. He completely changed the stereotype of the cowboy in the popular imagination.

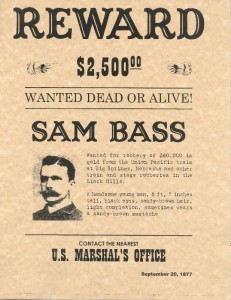

Before him, the cowboy was portrayed as either a comic figure or as a hooligan—especially the Texas drovers who rode into trail towns to get drunk and raise hell.

In the 1880s, there were frequent stories in eastern newspapers about cowboys wanted for robberies and shootings.

In Owen Wister’s hands, the cowboy became someone likable, who with his inborn Southern chivalry was able to win the heart of a young woman.

A man of both wit and grit, the Virginian puzzles over how some good men go bad, mourns the loss of his friend Steve, who gets hanged as a horse thief, and finally defends his own honor, proving he is not a coward, in a gun duel with the novel’s villain.

All of this, so familiar after a century of westerns, established a character type that was brand new in 1902.

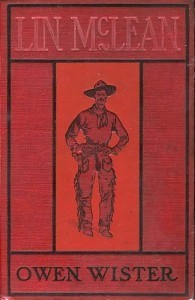

(Readers, a personal note here. I didn’t care for The Virginian, but I loved Lin McLean, by the same author)

(Readers, a personal note here. I didn’t care for The Virginian, but I loved Lin McLean, by the same author)Q. Have Westerns influenced the way this country feels about tribal peoples?

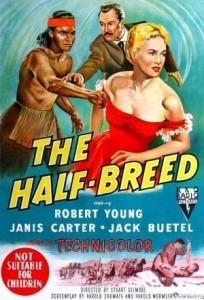

A. In 1900, tribal peoples were regarded as a “vanishing race,” and this notion was reinforced in fiction, some writers sentimentalizing them as “noble savages.”

Others wrote of them using widely accepted derogatory stereotypes.

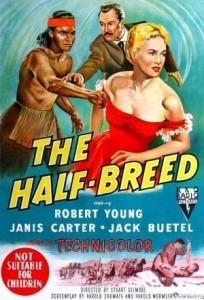

Held with particular distaste and scorn were so-called “half-

breeds,” who were believed to exhibit the worst traits of both races.

breeds,” who were believed to exhibit the worst traits of both races.Today, you will find whites who are proud to claim any native ancestry, which I think would have astounded white Americans 100 years ago.

And while we may see a shift in the media, I wouldn’t be willing to say whether you can attribute much of that to the western itself.

Q. You have published lists of Western words in your blog (hundreds) that you’ve garnered from your reading, most of them dating from the late 19th century and early 20th. Can you tell us what some are and what they mean?

Q. You have published lists of Western words in your blog (hundreds) that you’ve garnered from your reading, most of them dating from the late 19th century and early 20th. Can you tell us what some are and what they mean?A. Here are a few I’ve just added to the list:

ranikaboo = nonsense; prank.

scrag = to hang (on a gallows); throttle, choke.

skew-gee =crooked, slanted, cockeyed.

snuffy = wild or spirited.

solemncholy – solemn and melancholy, woe-begone, troubled.

spotted pup = rice pudding.

spotted pup = rice pudding.Q. Do you enjoy these words?

A. I enjoy the glimpse they give us into the common culture of the turn of the last century, things like children’s games, songs, dances, fashion, historical figures, myth and biblical references that were common knowledge.

Then there’s the evolution of language itself, with the constant tide of new slang, idioms, and informal expressions.

Q. You have reviewed hundreds of Western books and movies. Could you recommend five great Western movies and tell us why you enjoyed them?

A. I am a Randolph Scott fan. He carries himself and expresses himself with so much class. He can be stoic or wryly amused; you’re always getting a solid performance.

Favorite film: SEVEN MEN FROM NOW.

Favorite film: SEVEN MEN FROM NOW.Of John Wayne’s films, I like the later ones when he wasn’t acting and seems to just be himself, with what seems like a relaxed, natural sense of humor.

Best film: EL DORADO. Robert Mitchum, another favorite, also makes that film A+.

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE is terrible as history, but I love Henry Fonda. He’s such a warm-hearted Wyatt Earp. And it’s got to be Walter Brennan’s best role.

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE is terrible as history, but I love Henry Fonda. He’s such a warm-hearted Wyatt Earp. And it’s got to be Walter Brennan’s best role.THE WILD BUNCH has a wonderful big cast, is well written and is just a handsome and exciting film. Of Peckinpah’s efforts, it stands out as the best for me.

The original 3:10 TO YUMA is a personal favorite. It shows the richness and depth of the western genre, and how you can make a compelling story out of just two men talking in a hotel room, waiting for a train.

The remake proved that you can’t improve on that by adding a mess of senseless and bloody violence.

Q. Are Westerns dying?

A. As long as writers and filmmakers keep reinventing the western, as they have been, I think it will continue to show signs of life.

The post Ron Scheer: HOW THE WEST WAS WRITTEN appeared first on .

HOW THE WEST WAS WRITTEN

Hi Ron Scheer: Thanks for talking to me.

Readers, Ron runs Buddies in the Saddle, or buddiesinthesaddle.blogspot.com, where he reviews Western books and movies, specializing in books published between 1880 and 1915.

He also reviews (mostly) older Western movies.

Ron Scheer

Ron also publishes lists of words he’s gathered from the books, almost all of which vanished with the frontier.

This year, Ron published How The West Was Written, examining how writers have historically presented the West.

(Readers: full disclosure. I commented on Ron’s book in early draft forms and he was kind enough to mention me, and others, in a forward to the published edition).

Q. Ron, can you tell us about the various ways authors have presented the West?

A. From the beginning, there were many Wests, some actual, some mythical. In the dime novels of the 19th century, it was a wild terrain populated by hostile tribes and outlaws, well suited in fiction for action and adventure.

A. From the beginning, there were many Wests, some actual, some mythical. In the dime novels of the 19th century, it was a wild terrain populated by hostile tribes and outlaws, well suited in fiction for action and adventure.But as the frontier became a setting for mainstream fiction, it took on other associations.

(Authors) described freedom and independence from the rigid social structures and crowded living conditions of the East.

Freedom from social constraints was especially true for women

(they wrote), who could dress more informally, ride astride a horse rather than sidesaddle, and use firearms.

(they wrote), who could dress more informally, ride astride a horse rather than sidesaddle, and use firearms.The egalitarian, democratic spirit of frontier settlements also allowed for a degree of social mixing frowned on elsewhere.

The young heroine of Therese Broderick’s The Brand (1909), newly arrived in Montana, is enraptured by the promise of “untrammeled freedom” and will hear nothing of “don’ts and can’ts.”

The young heroine of Therese Broderick’s The Brand (1909), newly arrived in Montana, is enraptured by the promise of “untrammeled freedom” and will hear nothing of “don’ts and can’ts.”Women writers often voiced strongly feminist views. Some actively supported the temperance movement, which eventually led to the closing of the saloons and Prohibition.

Several writers were advocates of social reform and even identified as Socialists. In their novels, they decried the corruptive dominance of a robber-baron economy, which flourished in the West.

(Also authors wrote about) a healthful climate, especially for those with pulmonary afflictions, like TB; a land of opportunity, where homesteading made land ownership within the reach of so many; and a place to get rich quick through exploitation of natural resources, monopolies of services like railroads, and mining for gold and silver.

An 1884 novel about the plight of California’s Indians.

Q. It seems many more women wrote Westerns in the past. Is that’s so, why aren’t women writing westerns like they used to do?

A. Women writers contributed generously to the outpouring of frontier fiction a century ago. But they were far less likely to write cowboy westerns.

B. M. Bower (Chip of the Flying U, 1906) is an exception.

And even her novel is more properly a ranch romance. It doesn’t venture into the male world of saloons, gunfights, outlaws, and the outdoors.

Miss Bower

Owen Wister was able to straddle both worlds of action and romance in The Virginian (1902), but the two strands have remained largely separated along a gender divide ever since.

Look at the cover art for most western-themed fiction today. It’s

either a fully dressed cowboy firing six-guns or a shirtless one who looks like he spends most of the day at the gym.

either a fully dressed cowboy firing six-guns or a shirtless one who looks like he spends most of the day at the gym.Q. Many Westerns have been highly influential in American culture; can you tell us about them?

A. If we’re talking books, it’s been argued that Owen Wister’s The Virginian had the biggest impact on how Americans imagined, understood, and were excited by the West—as much as by Bill Cody’s traveling Wild West show.

The book was the no. 1 bestseller for the year it was published and appeared again on the same top-10 list the following year.

The book was the no. 1 bestseller for the year it was published and appeared again on the same top-10 list the following year. It was made into a hugely successful stage play and adapted to film several times, not to mention providing a cast of characters for one of the longest-running western series on TV.

As for the influence of western movies, I’d name the cowboy actors who portrayed most vividly an ideal of manhood, probably starting with Tom Mix and ending with John Wayne.

Q. If you had to recommend one Western book for readers (published between 1880 and 1915), what would it be and why?

A. It would have to be The Virginian, for the reasons I’ve already mentioned. Plus the fact that it’s enjoyable to read.

Wister was writing from personal experience of the West. He had both a good eye for authentic detail and a sense of humor—neither of which a reader is likely to find in Zane Grey.

Wister was writing from personal experience of the West. He had both a good eye for authentic detail and a sense of humor—neither of which a reader is likely to find in Zane Grey.The Virginian was the first romantic cowboy hero. He completely changed the stereotype of the cowboy in the popular imagination.

Before him, the cowboy was portrayed as either a comic figure or as a hooligan—especially the Texas drovers who rode into trail towns to get drunk and raise hell.

In the 1880s, there were frequent stories in eastern newspapers about cowboys wanted for robberies and shootings.

In Owen Wister’s hands, the cowboy became someone likable, who with his inborn Southern chivalry was able to win the heart of a young woman.

A man of both wit and grit, the Virginian puzzles over how some good men go bad, mourns the loss of his friend Steve, who gets hanged as a horse thief, and finally defends his own honor, proving he is not a coward, in a gun duel with the novel’s villain.

All of this, so familiar after a century of westerns, established a character type that was brand new in 1902.

(Readers, a personal note here. I didn’t care for The Virginian, but I loved Lin McLean, by the same author)

(Readers, a personal note here. I didn’t care for The Virginian, but I loved Lin McLean, by the same author)Q. Have Westerns influenced the way this country feels about tribal peoples?

A. In 1900, tribal peoples were regarded as a “vanishing race,” and this notion was reinforced in fiction, some writers sentimentalizing them as “noble savages.”

Others wrote of them using widely accepted derogatory stereotypes.

Held with particular distaste and scorn were so-called “half-

breeds,” who were believed to exhibit the worst traits of both races.

breeds,” who were believed to exhibit the worst traits of both races.Today, you will find whites who are proud to claim any native ancestry, which I think would have astounded white Americans 100 years ago.

And while we may see a shift in the media, I wouldn’t be willing to say whether you can attribute much of that to the western itself.

Q. You have published lists of Western words in your blog (hundreds) that you’ve garnered from your reading, most of them dating from the late 19th century and early 20th. Can you tell us what some are and what they mean?

Q. You have published lists of Western words in your blog (hundreds) that you’ve garnered from your reading, most of them dating from the late 19th century and early 20th. Can you tell us what some are and what they mean?A. Here are a few I’ve just added to the list:

ranikaboo = nonsense; prank.

scrag = to hang (on a gallows); throttle, choke.

skew-gee =crooked, slanted, cockeyed.

snuffy = wild or spirited.

solemncholy – solemn and melancholy, woe-begone, troubled.

spotted pup = rice pudding.

spotted pup = rice pudding.Q. Do you enjoy these words?

A. I enjoy the glimpse they give us into the common culture of the turn of the last century, things like children’s games, songs, dances, fashion, historical figures, myth and biblical references that were common knowledge.

Then there’s the evolution of language itself, with the constant tide of new slang, idioms, and informal expressions.

Q. You have reviewed hundreds of Western books and movies. Could you recommend five great Western movies and tell us why you enjoyed them?

A. I am a Randolph Scott fan. He carries himself and expresses himself with so much class. He can be stoic or wryly amused; you’re always getting a solid performance.

Favorite film: SEVEN MEN FROM NOW.

Favorite film: SEVEN MEN FROM NOW.Of John Wayne’s films, I like the later ones when he wasn’t acting and seems to just be himself, with what seems like a relaxed, natural sense of humor.

Best film: EL DORADO. Robert Mitchum, another favorite, also makes that film A+.

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE is terrible as history, but I love Henry Fonda. He’s such a warm-hearted Wyatt Earp. And it’s got to be Walter Brennan’s best role.

MY DARLING CLEMENTINE is terrible as history, but I love Henry Fonda. He’s such a warm-hearted Wyatt Earp. And it’s got to be Walter Brennan’s best role.THE WILD BUNCH has a wonderful big cast, is well written and is just a handsome and exciting film. Of Peckinpah’s efforts, it stands out as the best for me.

The original 3:10 TO YUMA is a personal favorite. It shows the richness and depth of the western genre, and how you can make a compelling story out of just two men talking in a hotel room, waiting for a train.

The remake proved that you can’t improve on that by adding a mess of senseless and bloody violence.

Q. Are Westerns dying?

A. As long as writers and filmmakers keep reinventing the western, as they have been, I think it will continue to show signs of life.

August 23, 2014

Colin Falconer: Witches, Wagah and History

Hi Colin Falconer, thanks so much for talking to me. You’ve seen more exotic stuff than anyone I know and also written more novels (which I love).

Readers, Colin migrated from his home country, England, to Australia, where he spent most of his adult life, then moved to Spain.

Now he’s back in kangaroo country, thanks to a romance (it’s a secret, don’t ask).

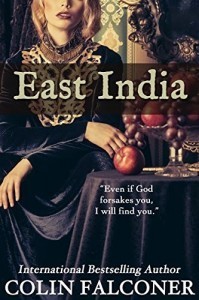

In the meantime, he’s written more than thirty historical novels and thrillers, traveled the world for research and been translated everywhere.

Q. Colin, What’s the most interesting historical facts you’ve run across?

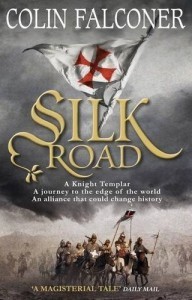

A. That Xanadu was a real place and not just Coleridge’s drug habit (and an Olivia Newton John song). That there was a Christian church in China in the thirteenth century (SILK ROAD). That the Sultan’s mother ran his harem (HAREM). That Isabella of France invaded England (ISABELLA)!

A. That Xanadu was a real place and not just Coleridge’s drug habit (and an Olivia Newton John song). That there was a Christian church in China in the thirteenth century (SILK ROAD). That the Sultan’s mother ran his harem (HAREM). That Isabella of France invaded England (ISABELLA)!I went to school in England and the teachers only ever told me about William the Conqueror. They didn’t mention that one out of every 200 living males share Genghis Khan’s DNA (SILK ROAD again). That sort of stuff.

Or that the British MI6 conspired to keep World War Two going and sabotaged German peace efforts (ISTANBUL).

(Because MI6 was thoroughly infiltrated by the Russians – and Stalin didn’t want the war to end until he’d annexed half of Europe).

Q. How do you write so many books?

A. I don’t know. I just have so many ideas, once I’ve started on something I want to get it done.

Also, I am very strong on structure, I believe, so a book is pretty much written in my head before I even write Chapter One. It means there’s no getting stuck halfway through or rewriting whole chunks of book any more. That helps. Plus I have seven fingers on each hand, it means I can type faster.

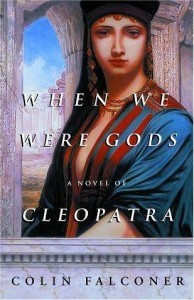

Q. You seem more attracted to women historical figures than men. Why?

A. Two reasons; one is very prosaic, the other less so. First, more women read historical fiction than men and they mostly like reading about women.

Cleopatra

But second, I find the women more interesting. Their predicament was much more complex than mens’ situations, historically speaking. They had to be extraordinary to stand out – men just needed a bloodline and some sort of sharp weapon.

Q. Is there any one historical period you enjoy more than another, and why?

A. I’ve always loved the twenties and thirties. Perhaps I read too much

Somerset Maugham as a kid. I’ve written a few books about that period but they don’t do as well as earlier time periods so I don’t do them much now.

Somerset Maugham as a kid. I’ve written a few books about that period but they don’t do as well as earlier time periods so I don’t do them much now. A publisher once told me not to write about anything after 1800 and now I see why. At the time I thought (the publisher) was just being difficult.

Q. You’ve seen a lot of things; such as the Mexican witch you told us about on your blog. Can you tell us a few stories, including the one about the black witch?

A. The witch was a scary individual. He looked more like a gangsta rapper than a refugee from Macbeth; he was also quite hard to find. His ‘office’ was a room in a huge house in the back streets of this little Mexican town, filled with skulls and statues of native Indians and lit with hundreds of red candles.

His first words to me were: ‘Is this business or love?’ I really didn’t have anything in mind so I said love.

He said: ‘Do you want her back or do you want her to die?’ Just like that.

I stammered a bit.

Colin, in 2012 interview

Colin, in 2012 interview

He said: ‘Give me a picture of her and twenty dollars and I will bring her back to you.’

It happened that I still did have a photo of her, and I did want her back in my life, but I wasn’t giving it to him, no matter how badly I wanted things to be different. (Even though it’s all superstitious nonsense, of course).

So I walked out.

But THE BLACK WITCH OF MEXICO is about a guy who hands over the photo and the twenty bucks even though he doesn’t believe in it … and what happens next.

That was an interesting trip, but then Central and South America are interesting places; I got to dance with a voodoo queen in a favela in Salvador and take ayahuasca with a shaman in the Peruvian jungle – the real stuff (not the crap they give to backpackers that’s laced with cocaine.)

Prepared ayahuasca

I asked the shaman if ayahuasca was dangerous: ‘He said no, only if you see a purple jaguar and run away screaming into the jungle. But that’s why he’s here.’

He pointed to the young guy with him. ‘He’ll run after you and catch you before you jump in the river.’

Fortunately I never saw a purple jaguar.

But Don Antonio was an interesting guy, he taught me and my mate a lot about shamanism.

I also went to see a guy called John of God, a famous Brazilian faith healer. So far I’ve only used the witch in a story; I’m sure these others will work their way in somewhere.

John of God

I make out I’m a pagan, but I am actually fascinated with all forms of spirituality. I’m always asking questions about the Unseen, it’s there as a shadow in many of my books.

Q. What’s the most interesting two things you’ve ever witnessed?

A. Well one would have to be John of God. He does these insane things, like sticking forceps up people’s noses and cutting them open with rusty scalpels.

John of God working on a patient

People say it’s all a conjurer’s trick; but the odd thing is, that’s what he says too.

He asks people ‘Do you want a visible or invisible healing?’ So he pulls these stunts only on request, he says he can heal without all the sideshow, that they don’t need the magic tricks.

And he gets these amazing results on the people he chooses to heal; yet he doesn’t choose everyone.

The original John of God

You can be picked first time up; other people have been living at his ‘casa’ for six months and he’s never chosen them once.

It was one of the most fascinating places I’ve been, like nothing I’ve ever experienced.

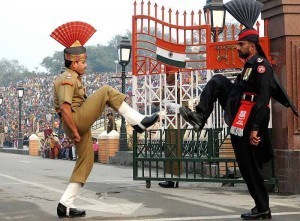

The other interesting thing, for a very different reason, is the flag lowering ceremony at Wagah, on the Indo-Pakistan border near Amritsar.

It takes place every sunset and starts with all this posturing by soldiers from both sides, and ends in the perfectly coordinated lowering of the two nations’ flags.

There are thousands of people – mainly Indians – who watch it from the bleachers, screaming and yelling abuse at the other side through the fence.

I saw the ceremony in 2003; the theatrics have since been toned down. The ceremony I saw was just as Michael Palin described it; ‘a display of carefully choreographed contempt.’

It also featured something that British comedian John Cleese once made famous on television; the Silly Walk, performed by an Indian sergeant major.

Silly walk

I have a video of it somewhere. I just sat there, astounded. Never seen anything as ridiculous – or as scary – as that ceremony, before or since.

Q. You volunteered for the ambulance service in Australia. Was that a deepening experience?

A. It was a highly rewarding one. I did it for 13 years and I’m proud of what our team achieved. It wasn’t easy; because we lived in a country beachside town, with many retirees and tourists, we had a high proportion of car smashes, beach rescues and cardiac events.

I’d be tapping away at my laptop one moment, half an hour later I’d be crawling into an overturned car.

But we had a brilliant team of people that it was a privilege to work with, and I know there’s people walking around today who wouldn’t be if our guys hadn’t given up the time and effort to train and volunteer to go on call.

Once three of the crew spent a night shivering up a cliff and finally got help to haul, drag and heft their guy down at four in the morning, then got up at six to go to work the next day. And their guy made it. I’m proud I was a part of it all.

Q. You were formerly published by a traditional publisher, but seem to have launched out on your own. Is that correct? Why have you done that?

A. I got heartily sick of traditional publishers. I’m sure they work just fine for Lee Child and James Patterson, but if you’ve not made that sort of breakthrough and don’t have a key to the liquor cabinet in Hachette’s lunch room, then the whole experience of trad pub is probably going to leave you feeling a little frustrated.

I had an appalling experience last time out with a British publisher, but since I’ve been with Bob and Jen at CoolGus – great people – I’m actually enjoying being a writer again. I have control of my own destiny to a large degree.

It helped that I had a large backlist to start with; but I’ve produced new books such as ISABELLA with them that has gone gangbusters, and also brought SILK ROAD to the US.

They promoted the hell out of (SILK ROAD) and got a result, while in the UK they managed to stuff it up completely despite great reviews. It would have broken my heart if that had been the end of it because it was a fantastic book.

Bob and Jen still encourage me to remain a hybrid author, but as I can easily put out four-five books a year, I’m keeping all my options open and I love being a CoolGus author.

Q. Are you staying in Australia or moving to yet another country?

A. Australia for the time being. It’s a brilliant place – a hundred million bush flies can’t be wrong.

A. Australia for the time being. It’s a brilliant place – a hundred million bush flies can’t be wrong. Q. What are you working on?

A. I have three at different stages.

One is set in 18th century Africa and India; I’ve just come back from a long research trip to finish the research. The backdrop is the Coromandel Coast of India, the British East India Company, the beginning of the Raj.

But what’s it about? It’s about losing everything and still finding the strength to keep going and win out.

The post Colin Falconer: Witches, Wagah and History appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

August 9, 2014

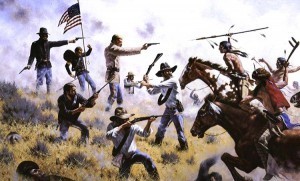

Custer’s Last Stand and The Strategy of Defeat

Hi Fred, thanks so much for the interview.

Hi Fred, thanks so much for the interview.You’ve done pretty amazing work on Custer’s Last Stand.

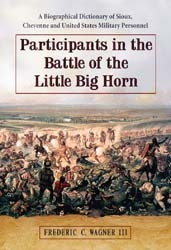

First, you wrote “Participants in the Battle of the Little Big Horn: A Biographical Dictionary of Sioux, Cheyenne and United States Military Personnel,” a 2011 reference work identifying every participant in the Little Big Horn battle, published by McFarland & Company.

The biographical dictionary is so thorough it includes civilians, civilian employees, scouts, horses, uniforms and weapons, among other things.

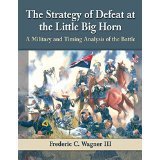

Now, you’re produced “The Strategy of Defeat at the Little Big Horn: A Military and Timing Analysis of the Battle,” also to be published by McFarland.

The latest book, headed for a January release, contains 53 pages of charts and 18 pages of source notes. Another 1,200 or 1,300 endnotes are included as well as 23 photos, four appendices, seven additional charts and 12 maps.

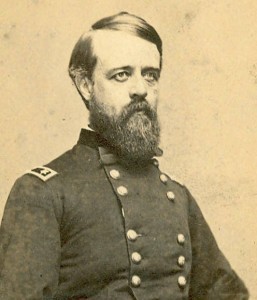

The latest book, headed for a January release, contains 53 pages of charts and 18 pages of source notes. Another 1,200 or 1,300 endnotes are included as well as 23 photos, four appendices, seven additional charts and 12 maps. Fred spent ten years as a Regular Army officer and an officer in the New York Army National Guard. He’s a former paratrooper, Army ranger, and Special Forces-trained psychological operations expert as well as a decorated Vietnam combat veteran and company commander. He wrote the divisional Standing Operating Procedures (SOP) manual for convoy operations in a guerilla warfare environment, First Infantry Division, Di-An, Vietnam, 1966 – 1967. Following that, he spent twenty-four years on Wall Street. He’s now on the Little Big Horn Associate Research Review editorial board.

Fred spent ten years as a Regular Army officer and an officer in the New York Army National Guard. He’s a former paratrooper, Army ranger, and Special Forces-trained psychological operations expert as well as a decorated Vietnam combat veteran and company commander. He wrote the divisional Standing Operating Procedures (SOP) manual for convoy operations in a guerilla warfare environment, First Infantry Division, Di-An, Vietnam, 1966 – 1967. Following that, he spent twenty-four years on Wall Street. He’s now on the Little Big Horn Associate Research Review editorial board.Q. How did you gather this much information? Did you have a method?

A. I have always been a prolific note-taker… probably because of my Catholic education, but maybe because I have always been interested in collecting “names” associated with certain events.

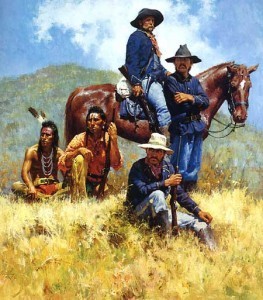

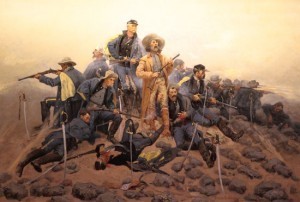

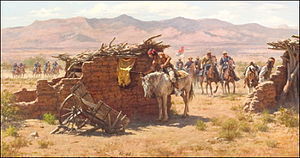

“Before The Little Big Horn” by Howard Terpning

“Before The Little Big Horn” by Howard Terpning

Whenever I find interesting anecdotes associated with a name or event, I add to it and after a while compelling stories develop. Today’s computers and their programs facilitate this collection process and the organizing of the data becomes fun for me.

Q. What did you conclude about the battle? What WAS the strategy of defeat?

A. The “strategy” of George Armstrong Custer’s defeat at the Little Big Horn lies in the interpretation of the orders he received from his boss, Brigadier General Alfred Howe Terry.

Gen. Alfred Terry

Controversy rages here, for there are some who feel Custer, because of a certain operational latitude Terry granted him in his orders… this, despite Terry’s expressed wishes to the contrary, was justified in not ascending the full length of the Rosebud Creek valley once he discovered the direction of the Indian trail.

Others feel that latitude did not pertain to subverting Terry’s desires, especially in light of the commander’s known wishes for concerted action involving his infantry forces.

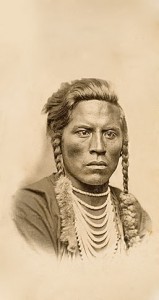

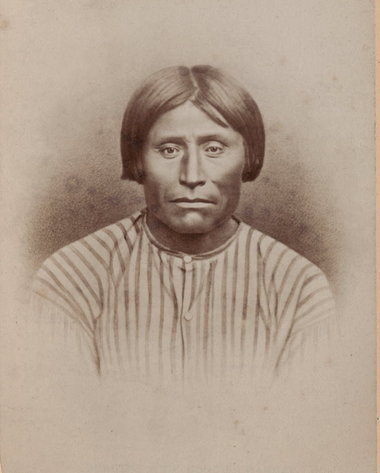

Curley, Custer’s Crow scout

Custer’s tactics must be viewed with this in mind, for had he followed the letter of his instructions his tactics would have been invariably different.

The strategy employed to accomplish his mission was sound—as were the ultimate tactics employed—but it was the subversion of that strategy—leading to those tactics—and then the subversion of the tactics that led to his defeat.

Chief Brave Bear of the Southern Cheyennes, was “elected” by other Indians as the man who killed Custer, although nobody really knew.

Had George Custer followed his orders as intended, his tactics would have changed, clearly, and while no guaranty of success, the outcome could have very well been different.

Q. Custer has many critics and many defenders. Which are you?

A. I am a critical defender of George Custer.

His orders aside, Custer performed as many military men would have… with some exceptions.

Unfortunately, those exceptions got him killed, but they were exceptions within the man’s make-up, within the man’s history, and within the man’s experience.

Unfortunately, those exceptions got him killed, but they were exceptions within the man’s make-up, within the man’s history, and within the man’s experience.Custer was an aggressive commander, but on this day he took too many risks and committed the classic blunders of an over-confident commander: refusal to heed the signs his scouts warned him about; underestimating the size and intentions of his enemy; not keeping his subordinate commanders informed; and allowing his divided command to fall away from mutual support.

Too many people blame both this division of command and his tactics for the regiment’s defeat, but neither, specifically, is the case.

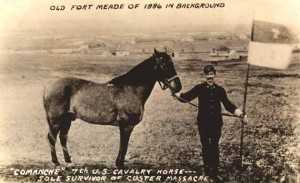

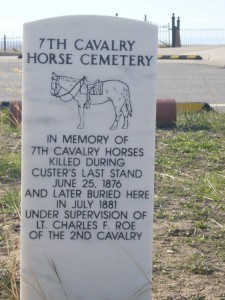

Comanche, one of only two or three horses which survived the battle

As he subverted the strategic plans, so he subverted his tactical plans by allowing these subordinates to fall away with no support.

Q. How did you figure out when each event occurred in the battle?

A. This was a long, hard, time-consuming process, aided substantially by organizing within computer software.

For some time I have believed if you do not understand the time events occurred—as precisely as possible—you cannot understand the battle of the Little Big Horn: too many events and too many personalities are interwoven.

Therefore, I set out to accumulate as much primary source material as I could find, and I developed 233 individual “profiles” (more than 80 of which are Native Americans)—some 810 pages—of battle participants and contemporaries, making a record of what they had to say.

Kicking Bear’s visual depiction of Little Big Horn.

Kicking Bear’s visual depiction of Little Big Horn.

From there, I broke the battle into 37 separate events which I labeled “incident reports” and culled the “profiles” to fill the “incident reports.”

This turned into some 605 Excel pages of 5,583 lines forming 33,498 separate Excel modules of data and descriptive explanations to draw from.

Armed with all this, I set out to draw up a time study for every significant occurrence of June 25, 1876, including the movements of single individuals.

Julia Robb, Novelist.

Julia Robb, Novelist.

July 27, 2014

Katie Hammons Waltz: The Undying Song

Last night I woke from a dream with a piano tinkling a waltz somewhere in the house, still seeing the dancers whirling behind my eyes, the ladies’ skirts flaring as they turned.

Last night I woke from a dream with a piano tinkling a waltz somewhere in the house, still seeing the dancers whirling behind my eyes, the ladies’ skirts flaring as they turned.And I knew Katie Hammonds had been here.

It wasn’t the first time.

This all started in October, 2012, when I flew to San Angelo, Texas for a writers’ conference at Stephens Central Library.

I flew in on the puddle-jumper and saw a country with more land than people, flat, dusty, dotted with mesquite trees and, improbably, crossed by the Concho– a skinny river running through scrubby banks and occasional cottonwood.

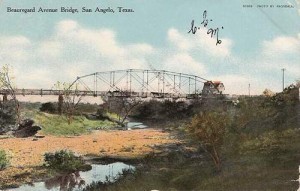

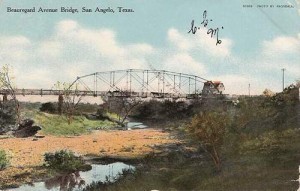

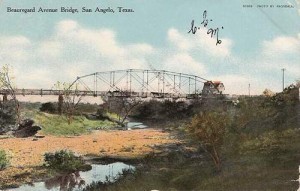

Beauregard Avenue Bridge over the Concho River

I had no transportation, couldn’t afford it, so one of the lovely library people gave me a ride to my bed and breakfast.

I didn’t like the B&B. The only lullaby was traffic. It was crowded with so much furniture I had to weave through the room. Doodads covered every surface and potpourri penetrated every crack.

A soundtrack featuring harps drove me crazy.

Nope, I thought, and turned to tell the hostess I was moving on.

Then I saw a piano, and the sheet music sitting in the rack was so old the parchment was yellow.

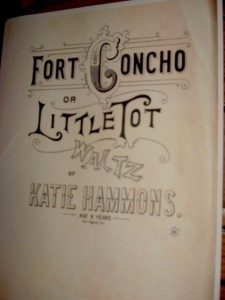

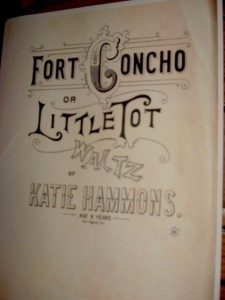

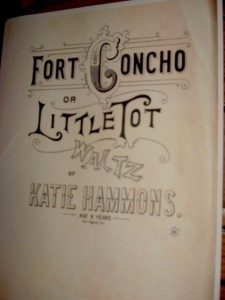

Then I saw a piano, and the sheet music sitting in the rack was so old the parchment was yellow.I wandered over to the piano and saw “Fort Concho or Little Tot Waltz By Katie Hammons. Age 9 years. San Angelo, Tex.”

Inside the sheet music it said, “Copyright, 1888, by E.W. Hammons.”

I played the piece. The waltz was written in b flat, and its tempo was allegro. It was simple and plaintive, evoking couples gliding on hardwood floors, candles fluttering, men and boys holding their partners oh so carefully.

Just discovering the music made me change my mind about the B&B. I felt like someone was telling me to stay: So I did, and got used to the smell of potpourri.

I badly wanted a copy of Katie Hammonds’ music, but the B&B owner did not give me permission to take the waltz to a copy shop.

But I had a feeling.

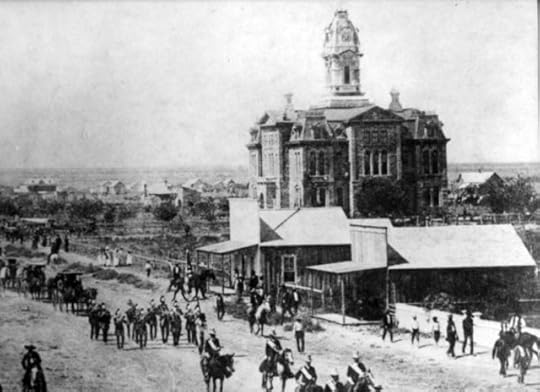

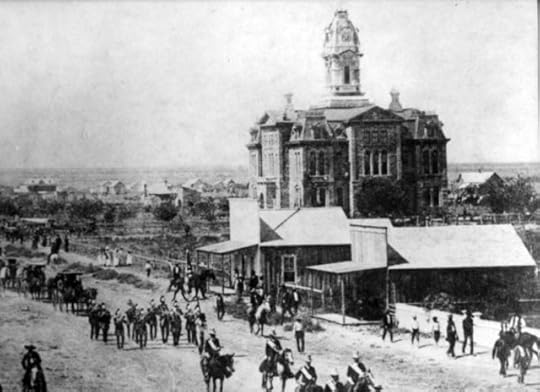

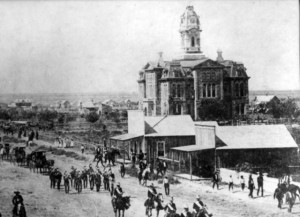

Parade passes the Tom Green County Courthouse on Sept. 17, 1888, celebrating the arrival of San Angelo’s first train.

I went to the West Texas Collection Archives at Angelo State University to research and the first thing I did was ask about Katie.

To my joy and amazement, they had an original “Little Tot Waltz” and gave me a copy! That made my week.

The collection also contained several undated newspaper stories about the Hammons’ family.

The Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad built this depot in San Angelo in 1888.

E.W. (Elijah Watkins) Hammons, Katie’s father, was a traveling piano salesman and owned shares in the local Artesian Wells Company.

E.W. also sold pianos in San Angelo and the nearby towns of Abilene and Ballenger, the paper said, and actually included the dates he was there.

E.W. must have done well. He bought a house and two lots in the “Miles Addition” for $225.

Drilling an artesian well on the Francisco Ranch

We know Katie had a B average in fourth grade, and no wonder. School principal H.V. Moulton bragged, to the paper, the grammar school had “A fine globe, fine sets of maps and charts, and our school board has ordered a set of philosophical apparatus.”

One more thing. The family eventually moved to Waco.

What happened to Katie? Did she die from some dread disease and was photographed in her coffin, as was often done in the 19th Century?

Katie’s fate could have been an eternal mystery, but I know so much, thanks to the kind folks at Waco Historical Society.

The Hammons lived in Waco one year then moved to Tarrant County (Fort Worth), where the family was listed on the 1920 census.

In 1930, the family lived in Dallas, on Roseland Street.

In the 30s, Katie, and her father and mother, Dorinda, lived in the same house on Roseland, as did sisters Dora, Ray and Rilla, as did Rilla’s husband and three little boys.

In 1930, Katie, 43-years-old, was an organ teacher.

E.W. died on June 30, 1934, of heart disease, and her mother died in 1941, both still living on Roseland Street.

Katherine Nanette Hammons died Aug. 21, 1962, of colon cancer. She was 83.

Both Katie and E.W. are buried at Restland Memorial Park, in Dallas.

There you go, two quiet lives.

We have no evidence, but I believe they were a happy father and daughter.

E.W. was musical, Katie was musical, and they lived together all their lives.

How he loved her. He was so proud of his nine-year-old that he published her music.

Katie, I played your waltz today and you seemed so close, as if you stood right by the piano.

The post Katie Hammons Waltz: The Undying Song appeared first on .

Katie Hammons Waltz: The Undying Song

Last night I woke from a dream with a piano tinkling a waltz somewhere in the house, still seeing the dancers whirling behind my eyes, the ladies’ skirts flaring as they turned.

Last night I woke from a dream with a piano tinkling a waltz somewhere in the house, still seeing the dancers whirling behind my eyes, the ladies’ skirts flaring as they turned.And I knew Katie Hammonds had been here.

It wasn’t the first time.

This all started in October, 2012, when I flew to San Angelo, Texas for a writers’ conference at Stephens Central Library.

I flew in on the puddle-jumper and saw a country with more land than people, flat, dusty, dotted with mesquite trees and, improbably, crossed by the Concho– a skinny river running through scrubby banks and occasional cottonwood.

Beauregard Avenue Bridge over the Concho River

I had no transportation, couldn’t afford it, so one of the lovely library people gave me a ride to my bed and breakfast.

I didn’t like the B&B. The only lullaby was traffic. It was crowded with so much furniture I had to weave through the room. Doodads covered every surface and potpourri penetrated every crack.

A soundtrack featuring harps drove me crazy.

Nope, I thought, and turned to tell the hostess I was moving on.

Then I saw a piano, and the sheet music sitting in the rack was so old the parchment was yellow.

Then I saw a piano, and the sheet music sitting in the rack was so old the parchment was yellow.I wandered over to the piano and saw “Fort Concho or Little Tot Waltz By Katie Hammons. Age 9 years. San Angelo, Tex.”

Inside the sheet music it said, “Copyright, 1888, by E.W. Hammons.”

I played the piece. The waltz was written in b flat, and its tempo was allegro. It was simple and plaintive, evoking couples gliding on hardwood floors, candles fluttering, men and boys holding their partners oh so carefully.

Just discovering the music made me change my mind about the B&B. I felt like someone was telling me to stay: So I did, and got used to the smell of potpourri.

I badly wanted a copy of Katie Hammonds’ music, but the B&B owner did not give me permission to take the waltz to a copy shop.

But I had a feeling.

Parade passes the Tom Green County Courthouse on Sept. 17, 1888, celebrating the arrival of San Angelo’s first train.

I went to the West Texas Collection Archives at Angelo State University to research and the first thing I did was ask about Katie.

To my joy and amazement, they had an original “Little Tot Waltz” and gave me a copy! That made my week.

The collection also contained several undated newspaper stories about the Hammons’ family.

The Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad built this depot in San Angelo in 1888.

E.W. (Elijah Watkins) Hammons, Katie’s father, was a traveling piano salesman and owned shares in the local Artesian Wells Company.

E.W. also sold pianos in San Angelo and the nearby towns of Abilene and Ballenger, the paper said, and actually included the dates he was there.

E.W. must have done well. He bought a house and two lots in the “Miles Addition” for $225.

Testing a Texas artesian well

We know Katie had a B average in fourth grade, and no wonder. School principal H.V. Moulton bragged, to the paper, the grammar school had “A fine globe, fine sets of maps and charts, and our school board has ordered a set of philosophical apparatus.”

One more thing. The family eventually moved to Waco.

What happened to Katie? Did she die from some dread disease and was photographed in her coffin, as was often done in the 19th Century?

Katie’s fate could have been an eternal mystery, but I know so much, thanks to the kind folks at Waco Historical Society.

The Hammons lived in Waco one year then moved to Tarrant County (Fort Worth), where the family was listed on the 1920 census.

In 1930, the family lived in Dallas, on Roseland Street.

In the 30s, Katie, and her father and mother, Dorinda, lived in the same house on Roseland, as did sisters Dora, Ray and Rilla, as did Rilla’s husband and three little boys.

In 1930, Katie, 43-years-old, was an organ teacher.

E.W. died on June 30, 1934, of heart disease, and her mother died in 1941, both still living on Roseland Street.

Katherine Nanette Hammons died Aug. 21, 1962, of colon cancer. She was 83.

Both Katie and E.W. are buried at Restland Memorial Park, in Dallas.

There you go, two quiet lives.

We have no evidence, but I believe they were a happy father and daughter.

E.W. was musical, Katie was musical, and they lived together all their lives.

How he loved her. He was so proud of his nine-year-old that he published her music.

Katie, I played your waltz today and you seemed so close, as if you stood right by the piano.

The post Katie Hammons Waltz: The Undying Song appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

July 26, 2014

Katie Hammonds’ Waltz-The Song That Didn’t Die

Last night I woke from a dream with a piano tinkling a waltz somewhere in the house, still seeing the dancers whirling behind my eyes, the ladies’ skirts flaring as they turned.

And I knew Katie Hammonds had been here.

It wasn’t the first time.

This all started in October, 2012, when I flew to San Angelo, Texas for a writers’ conference at Stephens Central Library.

I flew in on the puddle-jumper and saw a country with more land than people, flat, dusty, dotted with mesquite trees and, improbably, crossed by the Concho– a skinny river running through scrubby banks and occasional cottonwood.

Beauregard Avenue Bridge over the Concho River.

I had no transportation, couldn’t afford it, so one of the lovely library people gave me a ride to my bed and breakfast.

I didn’t like the B&B. The only lullaby was traffic. It was crowded with so much furniture I had to weave through the room. Doodads covered every surface and potpourri penetrated every crack.

Could pass for my B&B

A soundtrack featuring harps drove me crazy.

Nope, I thought, and turned to tell the hostess I was moving on.

Then I saw a piano, and the sheet music sitting in the rack was so old the parchment was yellow.

I wandered over to the piano and saw “Fort Concho or Little Tot Waltz By Katie Hammons. Age 9 years. San Angelo, Tex.” Inside, it said, “Copyright, 1888, by E.W. Hammons.”

I played the piece. The waltz was written in b flat, and its tempo was allegro. It was simple and plaintive, evoking couples gliding on hardwood floors, candles fluttering, men and boys holding their partners oh so carefully.

Just discovering the music made me change my mind about the B&B. I felt like someone was telling me to stay: So I did, and got used to the smell of potpourri.

I badly wanted a copy of Katie Hammonds’ music, but the B&B owner did not give me permission to take the waltz to a copy shop.

But I had a feeling.

Parade passes the Tom Green County Courthouse on Sept. 17, 1888, celebrating the arrival of San Angelo’s first train.

I went to the West Texas Collection Archives at Angelo State University to research and the first thing I did was ask about Katie.

To my joy and amazement, they had an original Little Tot Waltz and gave me a copy! That made my week.

The collection also contained several undated newspaper stories about the Hammons’ family.

The Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad built this depot in San Angelo in 1888.

E.W. (Elijah Watkins) Hammons, Katie’s father, was a traveling piano salesman and owned shares in the local Artesian Well Company.

E.W. also sold pianos in San Angelo and the nearby towns of Abilene and Ballenger.

The newspaper actually noted what dates E.W. traveled to other towns.

E.W. must have done well. He bought a house and two lots in the “Miles Addition” for $225.

Testing an artesian well in El Campo, Texas

We know Katie had a B average in fourth grade, and no wonder. School principal H.V. Moulton bragged, to the paper, the grammar school had “A fine globe, fine sets of maps and charts, and our school board has ordered a set of philosophical apparatus.”

One more thing. The family eventually moved to Waco. Drat.

What happened to Katie? Did she die from some dread disease and was photographed in her coffin, as was often done in the 19th Century?

This could have been an eternal mystery, but I know so much, thanks to the kind folks at Waco Historical Society.

The Hammons lived in Waco one year then moved to Tarrant County (Fort Worth), where the family was listed on the 1920 census.

In 1930, the family lived in Dallas, on Roseland Street.

In the 30s, Katie, and her father and mother, Dorinda, lived in the same house on Roseland, as did sisters Dora, Ray and Rilla, as did Rilla’s husband and three little boys.

In 1930, Katie, 43-years-old, was an organ teacher.

E.W. died on June 30, 1934, of heart disease, and her mother died in 1941, both still living on Roseland Street.

Katherine Nanette Hammons died Aug. 21, 1962, of colon cancer. She was 83.

Both Katie and E.W. are buried at Restland Memorial Park, in Dallas.

There you go, two quiet lives.

We have no evidence, but I believe they were a happy father and daughter.

E.W. was musical, Katie was musical, and they lived together all their lives.

How he loved her. He was so proud of his nine-year-old that he published her music.

Katie, I played your waltz today and you seemed so close, as if you stood right by the piano.

The post Katie Hammonds’ Waltz-The Song That Didn’t Die appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

July 12, 2014

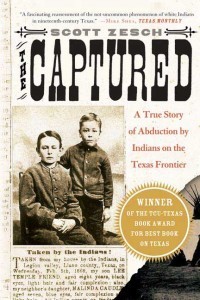

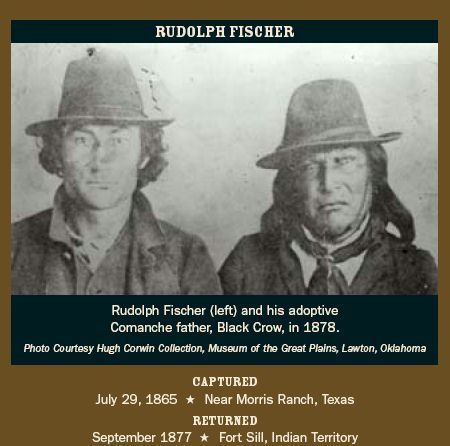

The Captured: Children Kidnapped by Comanches

Scott Zesch, thanks so much for the interview. “The Captured” is a fascinating book about ten children taken (mostly) by Comanche Indians and what happened to them when they were returned to their families.

Q. Can you tell us what made these children interesting to you?

Q. Can you tell us what made these children interesting to you?Scott Zesch: There were two things. First, one of these children was an ancestor of mine. Our family knew very little about him, and I wanted to see if I could follow his trail.

Second, I was a Peace Corps teacher in Kenya when I first got out of college. One of the clichés of Peace Corps is that coming home is harder than going over. These captured young people had that same experience, so I felt a sort of kinship with them.

Q. You did an excellent job investigating what happened to these children, both how they were kidnapped and their later life. You discovered none of the children did well after they were released.

They couldn’t stay married, they couldn’t keep a job, some of them never learned to read and write, they couldn’t stay in one place, they had a hard time communicating and generally seemed like unhappy people.

Can you explain why being a captive had this effect on the children?

A. I think the children responded very positively to the freedom of the Comanche way of life.

Most of them had known nothing but hard work on frontier farms before they were captured, and they discovered for the first time that there was another way to live.

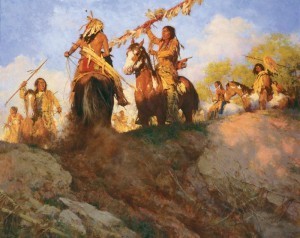

“Sunset for the Comanche,” by Howard Terpning

Once they got back home, I think they felt terribly confined. By then, their Comanche friends had been sent to the reservation, so there was no way the former captives could go back to the roving life they had known with them.

Q. The children did not seem angry at the Comanches, although the Comanches killed some of the children’s families, and committed atrocities in front of them. Can you explain why?

A. They didn’t seem to transfer their hatred of the individuals who killed their relatives to the Comanche people as a whole. Former captive Dot Babb put it best: “You wouldn’t want to kill every white person you saw because some white person had killed your mother.”

Former captive Dot Babb

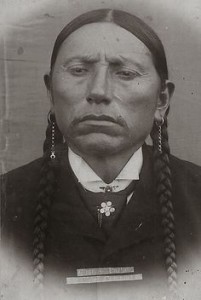

Q. Quanah Parker, who was born half-Comanche and led the tribe as it was fighting the U.S. Army, led a well-adjusted life after his surrender, becoming a prosperous land and cattle owner and maintaining successful relationships.

Why did Quanah do well compared to the children?

Quanah Parker, in mid-life

A. Quanah, unlike his white mother and the other captured children, hadn’t grown up in two worlds.

For all practical purposes, Cynthia Ann Parker was a Comanche by the time he was born. When Quanah came onto the reservation, he knew who he was, and he wasn’t torn between competing ways of looking at the world.

Q. You presented the Comanches in a sympathetic light, yet these children’s lives were seemingly ruined by their captivity. Can you explain more about this?

A. It’s interesting that you used the word “ruined,” because one of my fellow volunteers once told me half-jokingly: “Peace Corps ruined my life.”

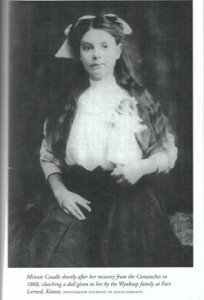

Former captive Minnie Caudle, holding her doll

In my opinion, immersing yourself in a very different culture is one of the most rewarding experiences you can have, but it comes at a cost, and that cost is usually a sense of rootlessness, of never completely belonging to one place or one people.

Q. The chapter about the two white women who were gang-raped and tortured is horrific. Didn’t Texans hate the Comanches because the Indians did regularly rape white women and keep them in their camps as sexual slaves?

A. Those incidents certainly fueled the fire, but when you look at the actual numbers, the capture and torture of adult women was relatively rare.

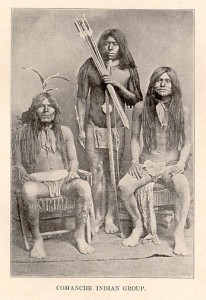

The Comanches preferred to take children who were young enough to be re-trained and would eventually come to identify with them. They seemed to think that grown women could never become assimilated, so when they did take them as prisoners, they used them as menials.

Former captive Banc Babb Bell

Q. It’s difficult for me to understand how a people can rape women (and they almost always did before killing them, as well as keeping them as sex slaves in camp), and practice lengthy torture, both on the trail and in camp, but at the same time love their own children, as well as adopted children. Do you have any thoughts on this?

A. Julia, the closest analogy I can draw is wartime atrocities. And, of course, what was happening in Texas at that time was war. There seems to be something in the human character that provokes people to brutalize and dehumanize “the enemy” in that situation (including civilians), but I’m afraid I can’t explain it.

Scott Zesch at the cave where Adolph Korn spent his last days.

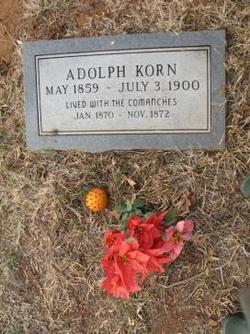

Q. Adolph Korn, your relative, had the most difficult time adjusting to white society. For instance, at the end of his life, he chose to live in a cave near Mason, Texas. Have you ever understood why adjusting was so difficult for him?

A. His fellow captive Clinton Smith described him as “about as mean an Indian as there was in the tribe at that time.”

Clinton Smith, socializing with Comanches

According to Smith, my ancestor’s exploits during horse-stealing raids were more daring than those of the natural-born Comanches. This was probably a form of conversion zeal. Because his assimilation was so extreme, I think he had a harder time readjusting.

Q. You seemed to feel a closeness and compassion for Adolph (which you also elicited from readers). Can you tell us more about that?

A. He was plunged into an amazing but bewildering experience at a young age, and I think he went through too many changes too fast.

Later in life, there was no one who knew how to reach out to him, and people saw him as a freak. I think that’s very sad.

Q. You said you sensed Adolph’s spirit in his cave. Did you mean that literally?

A. I felt a sense of invading his space. I already had qualms about putting the story of my very private and reclusive relative before the public, but visiting his home in the bluff seemed like too direct an intrusion.

Several people have asked me to take them to the cave, but I don’t want to go back.

Q. How did Adolph die?

A. I don’t know. He spent his last days in the home of his stepsister, my great-great-grandmother. His obituary mentioned “an illness of several months,” but no one in my family knows the actual cause of death. He was only 41.

Q. You wrote some of the children’s real families did not treat them with a great deal of love, but the children’s adopted Comanche families often did. You seemed to feel that might have something to do with why so many of the children were not happy with their white families when they were returned. Did I understand that correctly?

Clinton Smith wrote this book many years after he was returned to his family.

A. Basically, yes. It’s not that their white families didn’t love them, but the parents were working so hard to survive on the frontier that they didn’t have a lot of what we would call “quality time” to spend with their kids.

The children’s adoptive Comanche parents, on the other hand, invested a lot of time teaching them how to ride, hunt, shoot, swim, etc.

Q. What do you do for a living and are you writing? If you are writing, what are you working on?

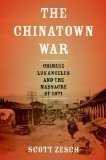

A. My last book was another narrative history about culture clash in the Old West, called “The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871.”

I’m currently working on a novel set in East Africa. My creative writing doesn’t pay the bills, so I am also a legal researcher and writer.

The post The Captured: Children Kidnapped by Comanches appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

June 27, 2014

“No Greater Calling” Total Indian War Guide

Eric Johnson, thanks for the interview. I’m so impressed by your book, No Greater Calling. You’ve provided something I’ve never seen before, a comprehensive guide to the Western Indian Wars.

Eric Johnson, thanks for the interview. I’m so impressed by your book, No Greater Calling. You’ve provided something I’ve never seen before, a comprehensive guide to the Western Indian Wars.Readers, Eric has provided the date and place for every hostile encounter between tribal warriors and the U.S. Army (1,400) that occurred between 1865 and 1898, plus the number of men killed and wounded, their names and the kind of wounds the men sustained.

Some of the reports include information on the battle and the names of men who earned promotions due to their conduct on the field. Medal of Honor winners are also included.

Medal of Honor: 1862-1896

Medal of Honor: 1862-1896Q. What inspired you to write this book?

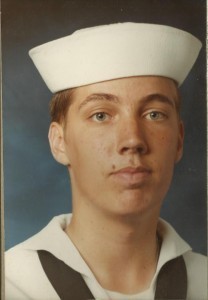

A. Of all that I’ve done in life, I am most proud of the time I spent in service to this nation in the United States Navy, having served nearly six years between 1985 and 1990.

As a veteran, I truly believe that all those who answer their nation’s greatest call deserve being honored, they deserve the simple dignity of having their names remembered.

I believe this to be the case regardless of the pursuits that placed these men in harm’s way, regardless of who these men were.

I hope in some small measure my work restores these men that dignity!

Post-Navy Eric, with his father

Post-Navy Eric, with his father

Q. Can you tell us where you got your information and how you put it together?

A. Early on, I had a vision of what I wanted to accomplish, that being to list the names of those men killed in action. Everything else was added as I continued my research!

The Adjutant Generals Chronological List provided me a frame around which to build my data. To that, I cross-referenced Francis Heitman’s Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army and Record of Engagements with Hostile Indians within the Military Division of the Missouri.

And finally, I further cross-referenced the resulting list to the Annual Reports of the War Department and, to a lesser degree, Indian Affairs.

Now that I had my list, a framework around which to frame my data, I had to fill in the names of those killed, and later wounded, in action.

This involved a total of three trips to the U.S. National Archives.

My primary source in providing names were individual files in Report of Diseases and Individual Cases or F-Files.

Also helpful were the Registers of Army Dead, a number of large volumes in which were alphabetically listed the names of Army dead for a certain period.

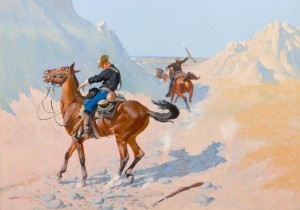

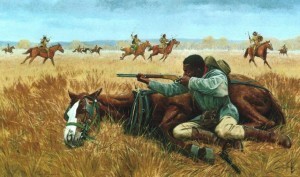

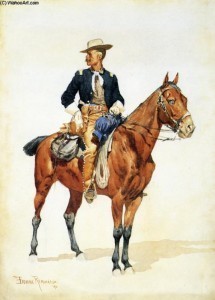

by Frederic Remington

by Frederic RemingtonThe F-Files were the reports filed by the attached medical officer immediately following the fight.

There’s a certain power in reviewing these documents, wondering about the condition of those filing these reports. Were they exhausted, having spent hours treating the wounded?

Finally, I tried to list one or more Secondary Sources for each fight…from both the Public Library and The Ohio State University Library in Columbus, Ohio.

I will say I am very, very proud of what I accomplished.

Q. Is it possible to estimate how many died of their wounds?

A. An accurate answer would require studying the carded medical files, a study involving countless hours at the National Archives.

Reno defense site, where more than sixty were wounded.

Reno defense site, where more than sixty were wounded.

That said…At Little Big Horn, the Reno defense site, sixty-five were wounded. I was only able to identify four who died of their wounds; Private William George on July 3, Private James Bennett on July 5, Private David Cooney on July 20 and Private Frank Braun on October 4.

During the Modoc War, of which I write more below, in a disastrous fight at Hardin Butte on April 26, 1873, twenty men were wounded.

Fortifications leading to Hardin Butte

Fortifications leading to Hardin Butte

I was able to identify three who later died; Private William Denham on May 6, 1st Lieutenant George Harris (who lived long enough for his mother to travel from Philadelphia to be at his side when he died on May 12), and First Sergeant Malachi Clinton on June 14.

And finally, during the Nez Perce War, thirty-eight men were wounded on August 9 and 10, 1877, near the Big Hole Basin, Montana Territory.

Big Hole Valley This battle became the turning point for the Nez Perce.

Big Hole Valley This battle became the turning point for the Nez Perce.

I identified two who died of their wounds; Sergeant William Watson on August 29 and 1st Lieutenant William English on September 19.

So, I look at three fights, a truly limited sample size. One hundred and twenty-three men were wounded and nine later died of their wounds. Just over seven percent?

Chief Joseph and Col. John Gibbon met again on the Big Hole Battlefield site in 1889.

Chief Joseph and Col. John Gibbon met again on the Big Hole Battlefield site in 1889.Even harder to represent are those who died of their wounds several months or even years later.

One such soldier was 2nd Lieutenant Franklin Yeaton, wounded by Apache Indians on December 26, 1869. He died nearly three years later on August 17, 1872. His obituary states his death was the result of that wound.

Should I have included him? I did not. Earlier versions did. If my publisher ever tasks me to do a second edition, perhaps I will include him again!

Q. Did you come to some personal conclusions about the Indian Wars and the Army by compiling the information?

A. I went into No Greater Calling with the belief that the Indian Wars were the inevitable result of the meeting of two cultures which little understood, and even less respected, each other. I have found nothing to make me believe anything different.

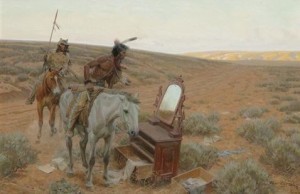

The Heirloom, by Tom Lovell

The Heirloom, by Tom Lovell