Julia Robb's Blog, page 5

July 23, 2015

Alamo heroes–Writer Talks about Travis, Crockett and Bowie

Readers, William C. Davis is here to talk to us about his book Three Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie and William Barret Travis, all three of whom died in the Alamo on March 6, 1836.

Davis is a professor of history at Virginia Tech and Director of Programs at that school’s Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, and has written many non-fiction books about historical figures and events.

I loved Three Roads to the Alamo; it is detailed, balanced and informative and I urge interested persons to pick up a copy.

Good job Mr. Davis, and thank you for agreeing to this interview.

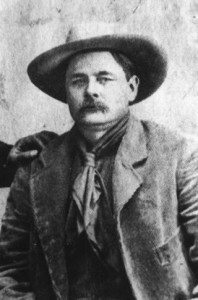

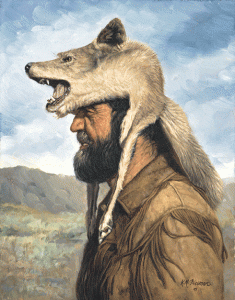

David Crockett

Question–Why do so many Alamo authors/historians criticize Travis, Crockett and Bowie, accusing them of not really being heroic and being flawed people; for instance, that Travis came to Texas fleeing from debt, leaving his wife and son behind?

Davis–I can’t answer that for all historians. Many, I think give in to the notion that in order to be a hero, someone must be perfect in all respects, and live up to the standards and ethical-moral expectations of our day, not just their own. That is virtually impossible.

Judging people of the 1830s by the standards of the 2000s is just foolish, and self-defeating. Yes they were all flawed. Travis was a lousy husband and skipped out of Alabama to evade debt. Bowie was a compulsive white collar criminal with his land frauds.

Crockett was another lousy husband, and pretty much irresponsible throughout. But such are the sort of men and women who built America.

Q–Has anyone ever found out what Travis and his wife were quarreling

about when he left Alabama?

Davis–Travis was not explicit. As I recall, there were hints of a possible romantic flirtation (between his wife) with another man or men, but that story appeared well after the fact as I recall. I suspect his habitual insolvency did not help, and it does seem that he had an impulsive nature that may not have helped.

Q–Travis’s critics say he left due to debts he couldn’t pay, but you point out Travis did pay the debts when his law practice became prosperous in Texas. Is that correct?

Davis–Yes, that is correct. As I recall, he finally retired all of his old Alabama debts before his death.

Q–As you say, nobody knows how or where Crockett died in the Alamo compound. Do you have an opinion?

Davis–Not really. We only know that at one point in the defense—some days before March 6—he and his Tennesseans were posted at the defensive line erected immediately in front of the Alamo church.

Davis–Not really. We only know that at one point in the defense—some days before March 6—he and his Tennesseans were posted at the defensive line erected immediately in front of the Alamo church.

Even if they were still there on March 6, however, that does not tell us where he died. The possibility has to be considered that he was taken alive and then executed, but that is only a theoretical possibility.

Q–A Mexican officer supposedly left a diary in which he wrote Crockett (or somebody in a coonskin hat) was captured and executed. Is this diary authentic? What do you think about it?

Davis–José de la Peña wrote a memoir in diary form some time after the Texas campaign. I believe the document is authentic, but that does not mean it is accurate, or that de la Peña actually witnessed everything he wrote about.

Santa Anna, Mexican dictator who led the Mexican army

There were already stories in the press about Crocket being taken alive and executed, and he could certainly have incorporated one of the stories into his narrative. This was commonplace for supposed memoirs and even “diaries” in the era.

Q–What previously undiscovered information did you find in the Mexican archives? I understand you were the first author/historian allowed access.

Davis–I think I may have been the first since Eugene Barker back in the 1920s or thereabouts. I found Mexican inventories of weapons and munitions captured in the Alamo, so we know now what the Texians were armed with—and they were well armed indeed.

There were also Mexican hospital reports totaling the numbers of dead and wounded, which had been wildly exaggerated previously.

And the reports by Mexican dragoon officers of the breakout attempts by two or three parties of Texians had been little mentioned previously, but now we have a good bit of detail on how the very last defenders died.

Q–Reading the book, I felt you admired and were fond of Crockett and Travis. Is this true?

Jim Bowie

Davis–I came to admire all three of them. Bowie was to me the most interesting and most complex.

I liked watching Travis grow up from the feckless youngster in Alabama, to the budding attorney and politician (he became) in Texas.

Crockett, for all is failings, was irresistibly interesting and entertaining.

Q–Some historians have charged David was not really a frontiersman, but a politician, so I was surprised reading the book that David (and his family) really were typical frontiersman, they embodied the typical American experience.

David’s grandparents were killed by Indians, his father fought in the American revolution and David was an avid hunter (eighty bears in one hunting season!) who typically moved up and down the frontier. Correct?

Davis–I don’t remember about the 80 bears in a season, but in all other respects Crockett was a typical poor white frontiersman, ever on the move looking for better and cheaper land, and never content to stay put on it or work it consistently.

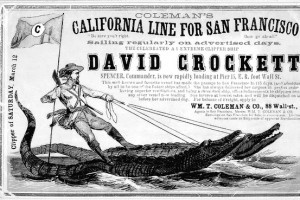

“Davy” Crockett was so famous in his own lifetime that ships were even named after him. And he was credited with superman-like feats, like riding an alligator. All this was due to “The Lion of the West,” a play written about him (but didn’t really portray David or anything he said about himself).

He became a politician, of course, though not a very sophisticated one, and was a bit out of his depth in Washington.

Q–Why did the three men you wrote about venture their lives at the Alamo (and for Texas independence generally). They didn’t have to do it.

Davis–None of them went to the Alamo to die, nor did any of the other 200 or so there. They all wanted and expected to live, and up until the end they were hoping for an anticipated reinforcement that would lift the siege.

Texian independence promised all of them a fresh start, as in the case of Crockett who hoped to rekindle his political career there, or a continuation of current prosperity as with Bowie, who saw great potential for land deals.

As for Travis, he was the only state-builder of the three, and he saw creating a new nation to be worth the risk.

Travis, as sketched by a friend a few months before his death.

Q–A friend of Travis sketched him a few months before the Alamo battle; our one likeness. Do you believe it looks like Travis?

Davis–It is the only likeness we have, so we’re stuck with it. It does superficially resemble a description of Travis left by one who knew him, but that’s all we can say.

Q–Bowie was a scoundrel, but he also fought for Texas. What do you make of this contradiction? He sold fake land grants, yet seemed like a courageous man.

Davis–He was a very courageous man. Again, we need to stop expecting our heroes to be cardboard cutouts from comic books.

They were all complex. I see no contradiction in Bowie being a land fraudster and being a Texian patriot. After all, if Texas succeeded, he stood to profit enormously by continuing his schemes.

All patriotism is a bit intermixed with self-interest.

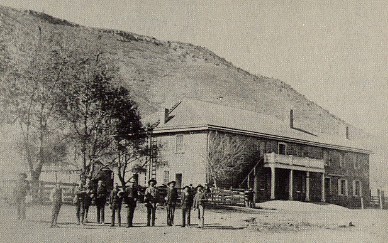

A reproduction of the original Alamo mission fortress

Q–For years, historians have claimed Sam Houston ordered Travis and company blow up the Alamo and retreat. But you say Houston did not order that but suggested it would be a good idea, and Provisional Governor Henry Smith ordered the Texas Army (in which Travis was an officer) to hold the fortress. How did historians make this mistake?

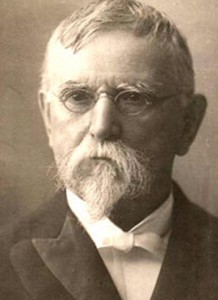

Texas Provisional Governor Henry Smith

Davis–Carelessness, to which we are all heir occasionally.

Q–Do you believe the Texas Revolution would have ended differently if the Alamo defenders (and the men at Goliad) had not been massacred?

Davis–I’m not keen on counterfactual history. However, I don’t see that the “massacres” necessarily changed things.

If Santa Anna had captured both garrisons and just kept the defenders as prisoners, I see no reason for that to have altered his leisurely timetable or moved in any fashion different from the fatally slow pace he adopted.

Q–You mentioned David and his group of friends stopping for the night in Bolivar, Tennessee, on David’s way to Texas (where he enlisted in the Texas army). You said, “In his coming there was something out of the ordinary, as sensed by everyone.”

What something did those people sense, in your opinion?

In His Own Words

Davis–Just the arrival of an American legend in his own time.

Q–Crockett impressed me, through your book, of having been an extraordinary man. Is this what you think?

Davis–In many ways yes. I think he was a pioneer in American idiomatic humor, that there is a fairly direct through-line from him to Mark Twain, to Will Rogers, to Garrison Keilor. Crockett is still funny today.

Q–David said, more than once, “I am rejoiced at my fate.” Do you believe he had a premonition about his fate?

Davis–No. The fate he was talking about was having landed in the middle of a revolt that looked like being successful, giving him a chance to be a military hero—as he had been, sort of—in the Creek War, and that would give him a platform from which to launch himself back to elective office.

Q–What about Travis? It seems so predestined that Travis was a man who wrote so well that his inspirational letters from the fortress have gone down in history.

Davis–Had he lived, I think Travis would have been a Senator or Governor inevitably. He had the instincts of a publicist, knew how to arouse emotions with words, and was genuinely committed to Texian independence.

Susanna Dickinson, who lived to tell the tale.

Q–Travis seemed fortunate to die in the beginning of the battle (his death witnessed by his slave Joe). Do you agree?

Davis–Joe is our only witness, or claimed witness. We do have a Mexican account soon afterward that seems to agree with what Joe said about where and how Travis died, so we can reasonably accept Joe’s account.

Q–Bowie reminds me of Moses, who was not allowed to enter the Promised Land because he had killed. Bowie could not fight at the final battle because he was (probably) dying of Typhoid.

Davis–That is my conclusion. A Mexican account written just days later says Bowie was hiding under a blanket when he was killed. I think that should be interpreted to mean that he was too ill to get up and fight, and conceivably could have died before the attack.

Q–Travis had a slave, Bowie was a slave trader and a dishonest man and David Crockett specialized in hunting and killing bears. Should we repudiate them for these reasons?

Davis–Of course not. As I said above, no hero is a saint, and these men were not.

They were men of their time, and in their time slavery was lawful, and in the South a mark of social status. As for killing bears, well Crockett didn’t do it to have them stuffed or mounted on walls. He fed his family with them.

David Crockett

The post Alamo heroes–Writer Talks about Travis, Crockett and Bowie appeared first on .

July 5, 2015

Del Norte Review, by Ron Scheer

This dark western novella from Texas writer Julia Robb begins appropriately with the gravestone of a murdered man. The stone leans against an interior wall of a saloon, the Del Norte of the story’s title, owned and operated by a Mexican woman, Magdalena Chapas. We’re in a dusty garrison town in West Texas. The year is 1870.

This dark western novella from Texas writer Julia Robb begins appropriately with the gravestone of a murdered man. The stone leans against an interior wall of a saloon, the Del Norte of the story’s title, owned and operated by a Mexican woman, Magdalena Chapas. We’re in a dusty garrison town in West Texas. The year is 1870.Characters. Robb gives us an ensemble of characters, several men and women who have fetched up on this isolated outpost. The battlefield carnage of the Civil War is recent history for two of the men, who share a memory of deprivation and disgrace in a POW camp in far-off Elmira, New York. Thomas, a decorated Union officer, bears wounds to both body and spirit. Wade is a doctor, a consumptive, and unable to practice his profession because of injuries to his hands.

Another man, an immigrant from China, takes an American name, Johnny, and tries vainly to assimilate as a westerner. A fourth man, Cortez, is a devil-may-care lothario with his boots under the beds of more than one woman unable to resist his charms. Meanwhile, married to Magdalena, he continues to lay claim to her as his wife, as well as all the rights and privileges due him as her lawful husband.

With a wayward spouse, Magdalena has given up on romance and marriage. Having killed her first husband for good reason, she has no confidence that offers of wedlock from her business partner, Thomas, will lead to anything but more grief and disappointment. Besides, she has responsibilities as the mother of an 8-year-old-son, born with a disability.

Themes. This is not the West of myth but a terrain where the social upheaval of the Civil War continues to be felt. West Texas, with its cultural origins in Mexico has been invaded by a ragtag occupying army, as well as civilian drifters from the South and North, and immigrants from Europe and Asia. Meanwhile, Comanches haunt the hills.

The isolation is profound. We are far from the nearest U.S. marshal or anyplace resembling civilization. And the unsettled, lonely lives of the handful of strangers who have converged here offer little in the way of community. The owner of the saloon across the street from the Del Norte is openly contemptuous of his competitor, Magdalena. Her partner, Thomas, reviles the doctor, Wade, who was once found guilty of stealing food from his fellow Confederate prisoners.

Julia Robb

Racial hatred is another subject. The Chinese man, Johnny Lan, is its victim as he blithely attempts to make of himself a rich man by marrying a white woman. And a Chinese woman, traveling with him, who has escaped being sold into slavery in America, has memories of witnessing the killing of whites in her homeland.

All of this and a good deal more produce a resolution that involves the use of firearms on the dusty street that separates the two rival saloons, and a reading from the Song of Solomon follows at a burial. It is a conventional ending that seems almost freshly contrived given the complexities of characters and their issues that precede it.

Robb’s graphic narrative style is suited to her portrayal of life on the frontier. Here a character rides onto an army post:

A pack of dogs snapped at the legs of his horse as he rode into the fort, barking so loudly he couldn’t hear the troopers drilling on mud-flecked horses. Laundresses in long, white aprons lugged piles of shirts and long johns from the barracks toward the washhouses.

In a saloon, the floor is stained with tobacco spit, and the contents of the spittoons are emptied by a hired swamper into a privy out back.

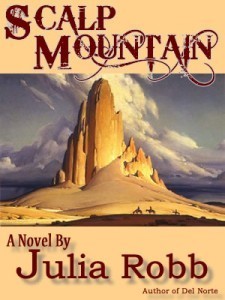

Wrapping up. Robb has an imagination that breathes life into the western in unexpected ways. Her novel Scalp Mountain (reviewed here a while ago, with an interview) took on racial animosities between whites and Apaches and told a grim adventure story of an abduction in the Rio Grande border country.

Del Norte is currently available in ebook format at amazon.

The post Del Norte Review, by Ron Scheer appeared first on .

July 2, 2015

Julia Robb, Scalp Mountain – Review and Interview by Ron Scheer

This is a fine novel. If you drew a line between Lonesome Dove and All the Pretty Horses, you would find Scalp Mountain somewhere along the way. Robb immerses you in a West that is saturated in violence and the sorrows that violence brings with it.

It is the 1870s in the border country along the Rio Grande and points west. The killing fields of the Civil War are a fresh memory, and the atrocities of the Indian Wars continue to haunt the days and nights of both whites and Apaches.

Plot

In the midst of all this, a young man, Colum McNeal, is pursued by killers. A fugitive, he has blood on his hands, having done the unspeakable, killing his own brother. He believes his pursuers are gunmen hired by his enraged father. One of them, Lohman, is a man he’s known for many years, who has mysterious reasons of his own for stalking him.

He has also been picked out for revenge by an Apache, Jose Otero, whose family has been killed by whites and his infant son taken. A fierce warrior, he thinks of himself as already dead. He is driven only by his last desire to break the hearts of those who have broken his own and his people’s spirits.

Ocotillo, Big Bend National Park, Texas

A well-meaning ranger, Captain Henry, complicates matters by saving the life of Otero’s infant son and giving him to the care of a childless couple, Michael and Clementine. When Otero abducts Clementine and his son, there follows a long chase into the Big Bend country, an arid and unpopulated desert region along the Mexican border.

Among this party of soldiers and civilians, lives are lost in firefights with Otero’s men. When Clementine is found, most of the surviviors turn back, leaving Colum and a handful of others to follow Otero. Among them are the generous and fatherly Captain Henry and the mysterious Lohman.

There are still many treacherous miles to cover and several turns of plot before the story reaches its end, steeped in more bloodshed and sorrows. Robb leaves a reader with this feeling you get sometimes from both McMurtry and McCarthy, that the West was won at a terrible cost, whether men or women, Indian or white, living or dead.

Heroism

The novel is compelling for the way it takes the elements of the traditional western and casts them in an unaccustomed light. Elmer Kelton would do something similar in his Texas Ranger trilogy, Lone Star Rising, but his focus is on the heroism found on both sides of the Indian Wars.

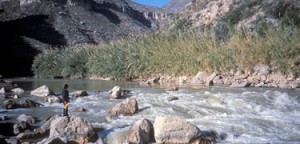

Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park, Texas

Robb looks past that, not to deny it, but to shake us to the core with the uncertainties and anxieties of living in those times. Also, to strip away some of the myth that obscures history. She humanizes the heroism, and doing so bonds us to her characters as people with hopes, fears, and mixed motives little different from our own.

Some might call her central character, Colum, an anti-hero. He harks back to Cain, the brother-murdering son of Adam and Eve. Alone in the world, he is haunted by guilt, regrets, and painful memories. A sexual urgency in him draws him powerfully to the wife of his friend Michael. We admire him finally for the courage to face whatever threatens to kill him, including his unforgiving father.

Wrapping up

As I began by saying, this is a fine novel. I rarely say about a novel that it was hard to put down. That’s no reflection on good writing; I’m just easily distracted. But there were times when this one had me and refused to let go. For anyone who likes their westerns well grounded in history, this is one you don’t want to miss.

Julia Robb describes herself as a former journalist and magazine writer, who grew up in small-town Texas. She now lives in Marshall, Texas, where she works as a free-lance editor. You can read about her life growing up at her blog. Scalp Mountain is currently available as an ebook for the kindle.

INTERVIEW

Julia Robb

Julia Robb has generously agreed to talk here today about writing and the writing of Scalp Mountain, so I’m turning the rest of this page over to her.

Fellow Texas writer Larry McMurtry has said, “Backward is just not a natural direction for Americans to look—historical ignorance remains a national characteristic.” Would you share that opinion?

Absolutely. Americans do not know or understand their history, and they have been brainwashed to believe in good guys and bad guys: Somebody has to be right. Liberal thinkers enjoy exposing notables as imperfect and more traditional thinkers believe in the myth of the heroic.

The truth is in between. From the beginning of the world, humans have been imperfect and complicated, thus our history has been imperfect and complicated. Thomas Jefferson was an impressive person and one who, with many others, risked everything to fight the English, but he was also human and probably had a slave mistress. Was he a bad man or a good man? Do we judge him by 21st Century standards, or by the standards of his time?

Much of this ignorance stems from America’s eagerness for the future, which produces a reluctance to look back even one day. It’s easier to put things in categories and go on. Mass media also trains people to want pablum. On the other hand, Americans (and probably most of the world) have always preferred the cheap seats.

Big Bend National Park, Texas

How do you define the term “traditional western,” and is Scalp Mountain an example of one?

I tried to write Scalp Mountain as a historical novel, meaning a book which helps explain events during a specific time period, and one which embodies themes. Many novels which appear to be Westerns are not; for instance, Tom Lea’s very fine The Wonderful Country.

I urge anyone interested in the frontier, Texas, Mexico and/or art, to read this book (Lea was a visual artist as well as a writer and he illustrated Wonderful Country). Lea never got the recognition he deserved for The Wonderful Country.

I guess I don’t know what a traditional Western is. I just take books for what they are.

To what extent did growing up and living in Texas help or hinder the writing of this novel?

I couldn’t have written Scalp Mountain without growing up in Texas, with the distances, the sky spreading to the end of the world. It shaped my spirit, although I’m not sure what shape it took. And Texans are not like other Americans and that has to do with their history; particularly the long, barbaric Comanche wars. It shaped the culture. (Read Empire of the Summer Moon, by S.C. Gwynne, to understand this).

I was exiled in Maryland for fifteen years, working, and I can tell you Maryland is wonderful, but its people were shaped by a whole different ethos.

In reading western fiction, can you tell those who write of Texas from a lifetime of first-hand experience and those who don’t?

I’m not sure, I haven’t read that many historical novels or westerns about Texas. There’s really not a whole lot of them. I can sure tell the late Tom Lea grew up in Texas. His tone, meaning the feel of the place, is perfect.

I’ve found women and men write different kinds of books about Texas, and/or the American West. Women writers tend to be sloppily sentimental about Indians and their culture (by the way, I’ve asked many Indians what they want to be called, Native American, etc. and they always told me they are comfortable with “Indian”).

Men tend to be more rigorous, although not always. One Texas writer wrote a novel from the Comanches’ point of view and he didn’t even mention Comanche raped their women captives to death, or kept them in sexual slavery. This kind of stuff is important because it’s truth.

Santa Elena Canyon, Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park

Did any of the characters surprise you as they took shape in the writing?

Henry surprised me. He turned out to be such a character; a man willing to do what he had to do, but loving in his attitudes, poetic (although a terrible poet) and whimsical. I missed him so much after, well, you know…

How closely does the finished story compare to the way you originally conceived it?

It’s pretty much the way I thought it out. The characters grew a little. And the research produced complete surprises. It was a revelation to find that everybody on the frontier scalped everybody else; white men scalped other white men, whites scalped Indians, Indians scalped Indians, Indians scalped whites. In one instance, some Indian even scalped a white man’s dog. That’s true.

Big Bend National Park, Texas

Talk about how you decided on the novel’s title.

This story is about the Indian Wars. I wanted to tell a balanced story and that meant demonstrating that both sides were right, both were wrong and everybody got hurt. The wholesale scalping was the perfect symbol for this. Do you remember the scene where Henry and Colum were riding past “Scalp Mountain,” and Colum told Henry why it was given that name?

Pima caught two Apache and crucified them on the mountain. They used real crosses and tied the Apache to the crosses with green rawhide, then left them to die in the sun. That really happened. I went a step further, to illustrate the book’s theme, by having the Pima decorate the crosses with scalps; white, Indian, Mexican.

To what extent was writing this novel influenced by western movies and TV?

I think all American writers have been influenced by film. We’ve had movies now more than one hundred years and it has trained everyone to see cinemagraphically. I know that’s the way I see, when I’m writing.

Talk a bit about the creative decisions that went into the cover of the novel.

I looked online for Texas landscape painters and found the wonderful David Forks. When I looked through his online gallery, I found the book cover. It seemed like a perfect illustration for the book, a somber mountain in West Texas.

I’m grateful to David for letting me use his painting and for designing the book cover for me. I urge everyone to go to his online gallery and look at his work. His website is at fineartstudioonline.com, or write him at davidforks.com.

Do women writers bring something to the writing of western fiction that male writers generally don’t?

No.

How would you hope to influence other western writers?

I don’t know how to answer that. We just all do what we do. I guess I do hope writers would delve deeper into events and produce books which are more complex and nuanced about cultures and people. Some idiot, writing on Facebook, recently declared that Custer was a psychopath. Total ignorance. Custer was not a psychopath.

What can readers expect from you next?

I’m not sure. I’ve written sixty pages of a novel I’m not happy with and it’s in a drawer. I have another finished novel, about Texas in the 1960s, about the power struggle between Anglos and Hispanics, but nobody will publish it. Agents say it’s not a genre novel, it isn’t mystery, it isn’t thriller, it isn’t fantasy, it isn’t a Western, etc., so we can’t sell it. I’m almost finished with a movie script based on Scalp Mountain. No telling what will happen to it.

Anything you’d like to talk about that we didn’t cover?

Yes, I believe life is tragic, but tragedy can produce redemption. Art, at its best, produces transcendence. And that’s what I’ve tried to do with this book.

Thanks, Julia. Every success.

Photo credits: Wikimedia Commons

The post Julia Robb, Scalp Mountain –

Review and Interview by Ron Scheer appeared first on .

June 19, 2015

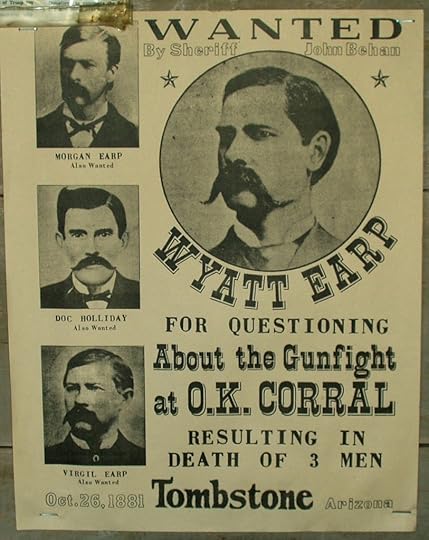

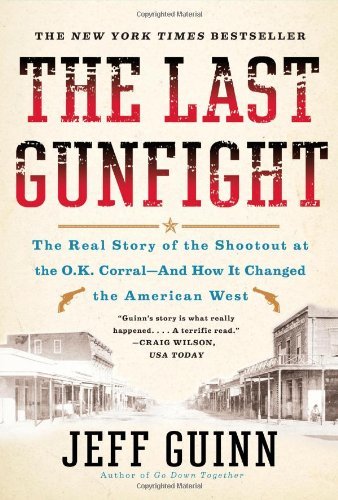

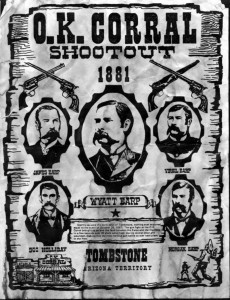

Jeff Guinn Talks Wyatt Earp and The Last Gunfight

People have argued about the Gunfight at the OK Corral since Oct. 26, 1881.

People have argued about the Gunfight at the OK Corral since Oct. 26, 1881.

Some say Wyatt Earp, his brothers and Doc Holliday, were bad guys.

Others believe the Earps were honest lawmen doing their job.

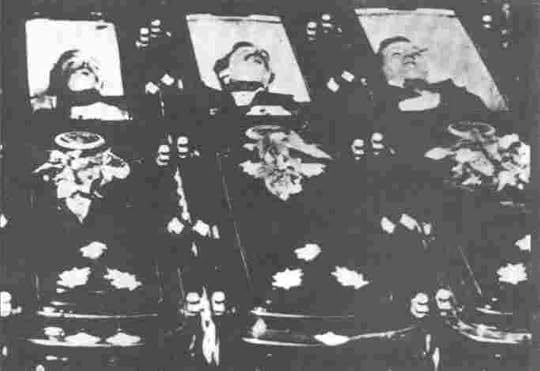

The men the Earps and Holliday gunned down, Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury and Billy Clanton, some say, were not as bad as they’ve been painted and were victims.

Jeff Guinn–a former journalist who lives in Fort Worth, Texas–has written a non-fiction OK Corral account titled The Last Gunfight and is here to set us straight.

Q. Jeff, you seemed to avoid calling anyone a hero, or a bad guy, and explained everything from the various protagonists’ point of view, but at the end of the book, Wyatt and Virgil Earp looked better than anyone else you wrote about.

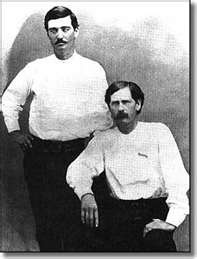

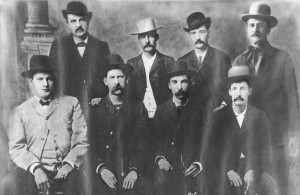

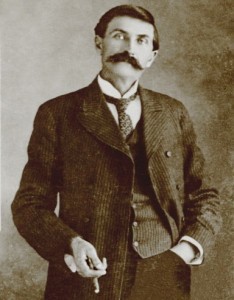

Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. Wyatt is seated.

The “cowboys” were obviously thieves, liars, and back-shooters, Tombstone’s citizens were unreliable and mercenary and Johnny Behan was a manipulating, dishonest coward and serial betrayer.

But Wyatt and Virgil did their duty as they saw it, and were honest men. And Wyatt was loyal to Doc when it cost him in Tombstone.

Did you think about this as you were writing the book? That these people proved what they were by their actions?

Johnny Behan

Guinn: I think it’s almost always dangerous to completely categorize people. There were no saints anywhere in or around Tombstone.

Wyatt and Virgil certainly did their duty as they saw it – but so did Johnny Behan. He was just more flexible in terms of what he was willing to do.

Most of the cow-boys felt themselves justified in breaking laws – in their minds, no one had the right to tell them what they could or couldn’t do.

They were wrong, of course, but that’s what they thought. (And it was an open secret that some laws could be broken with impunity – local authorities turned a blind eye toward rustling if the cattle were stolen from Mexicans.)

The challenge in writing this book, at least to me, was acknowledging this specific period ambiguity and still telling an objective story. Hopefully that allowed readers to draw their own conclusions.

The Mclaurys and Billy Clanton in their coffins. Billy at right.

Q. Why have so many writers/historians attempted to destroy Wyatt’s reputation, accusing him of everything from dishonesty to murder?

Last year, one such man accused Wyatt of being a horse thief based on the fact Wyatt was one of the men accused of the crime. Yet he was never convicted.

Guinn: I think some writers approach researching nonfiction books with the aim of proving what they already believe.

A self-proclaimed historian who already detests Wyatt will find and emphasize plenty of facts supporting his/her opinion. Admirers of Wyatt can focus on lots of other material indicating he was a paragon.

This is why I always try to write about subjects that are initially new to me. That way I don’t have to battle any pre-prejudices as I research and write.

Q. Many writers/historians have claimed (including yourself) that the Earps craved social status. What is that based on? If a person wants money and opportunity, is that the same thing as wanting status?

Guinn: The Earps didn’t just want to be rich. They wanted to be important. That’s critical in understanding what they did and why.

I don’t fault them for this. But I think that any objective study of the Earp family demonstrates that many of them had ambition beyond hefty bank accounts.

Frank McLaury

They consistently sought public office, usually with disappointing results. On the frontier, money did not always guarantee authority, which is what the Earps craved. (Not that they didn’t want money, too.)

Q. Why was Wyatt such a hard luck guy? Nothing much ever worked for him.

Guinn: Wyatt could be devious – for example, his scheme to catch the stage robbers and position himself to run against Johnny Behan – but he wasn’t subtle, and he also tended to believe that people would always honor their political and business obligations.

The trait that I most admired in him was his constant loyalty to family and friends. He kept his word when he gave it, a rare quality then and now.

Wyatt and Josephine in 1906, on their California property

Q. Did you systematically think about Wyatt’s character, and Doc’s, and Ike’s, etc? You seem to have excellent insight to their various characters.

Guinn: I hope that insight resulted in presenting real people to readers, not caricatures. Acceptable behavior changes from era to era. Wyatt, Doc, Ike and everyone else in The Last Gunfight can’t be judged by modern-day standards. They were men of their specific time and place.

I think it’s required of historians to give readers context, a sense of how and why people did things.

The late Stephen Ambrose once told me that all of his books were intended to answer one question: “How did they do that?” My books attempt to take it a little further: “WHY did they do that?”

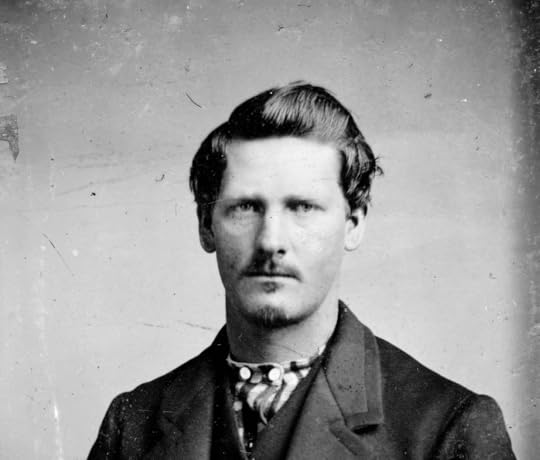

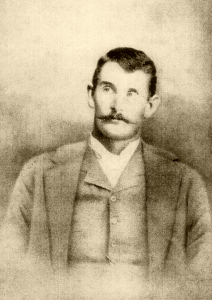

Wyatt, at about 21-years-old.

Q: Was Wyatt a dour man or an unhappy man? He looks unhappy in his photographs.

Guinn: Like the rest of us, I think Wyatt had his up and down moods. But he was also exceptionally driven, and the jolly gene isn’t usually dominant in such people.

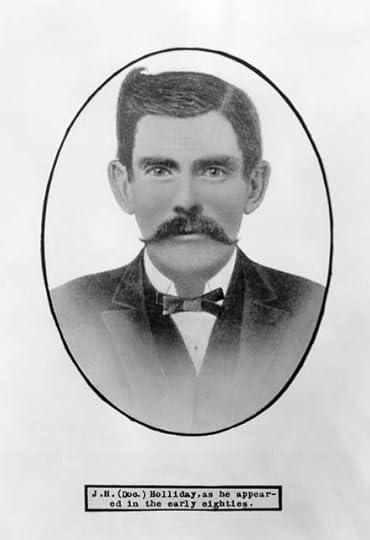

Q: At one point you wrote that Doc thrived on tension, excitement and drama, and he was an extremely dangerous man. What do you base that on?

Guinn: Even casual study of Doc’s life indicates that he often sought confrontation. It must be unsettling to know during every waking minute that you’re a dying man, that you’ll never reach old age. I suspect Doc would have preferred dying in a fight rather than in bed – this is just my opinion.

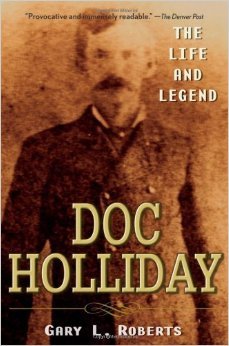

And, in every way, he is certainly an interesting man. I would have been tempted to write another book just about Doc Holliday, but Gary Roberts (in

Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend

), wrote the definitive one. Good for Gary.

And, in every way, he is certainly an interesting man. I would have been tempted to write another book just about Doc Holliday, but Gary Roberts (in

Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend

), wrote the definitive one. Good for Gary.Q: What did Wyatt see in Doc? He could have been grateful but kept his distance, but he didn’t. And why do you find Doc fascinating? That implies you believe there’s an element of mystery in Doc.

Guinn: I don’t think Wyatt Earp let political considerations affect his personal relationships. Doc Holliday was his friend, and he wouldn’t sacrifice that friendship even to achieve his own burning desire for status and personal power. This speaks well of him.

Tombstone before the 1881 fire.

Doc Holliday is such a protean figure. The more you learn about him, the less easily he can be categorized.

Some very questionable facts (i.e., that Doc was born with a cleft palate, with successful experimental surgery performed by a relative) have often been presented in books and accepted by readers.

Gary Roberts did an admirable job of research and writing. We can’t imagine many variations on Wyatt Earp or Ike Clanton – after careful, objective study, we can essentially know them, understand who they were. But there’s some eternal mystique about Doc.

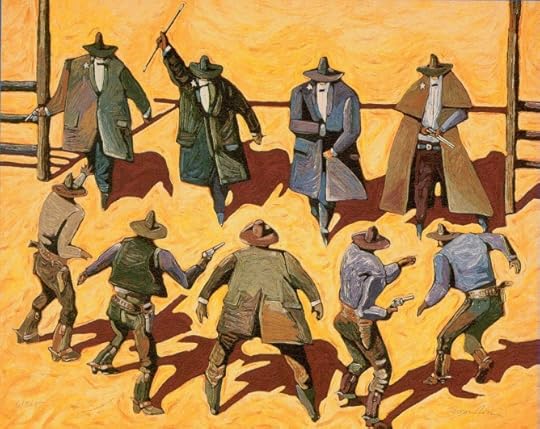

Artist Thom Ross has painted this depiction of the OK Corral gunfight.

Q: I’ve read Doc did not kill that many men; what’s true?

Guinn: That’s certainly true. As in the case of Billy the Kid, the number of notches on the handle of Doc’s gun have been greatly exaggerated. For one thing, he was a terrible shot.

Innocent bystanders were probably in more danger than whoever Doc might be aiming at.

Q: Many writer/historians find it contemptible that the Earp men’s common-in-law wives were former prostitutes and that Wyatt was a professional gambler? Is that how you feel?

Ike Clanton

Guinn: Wyatt Earp was a man of his times. Gambling was a respectable way to make a living.

Women were scarce on the frontier. Many turned to prostitution to survive until a better way to support themselves (or, more preferably, a husband) turned up.

I personally find no cause for contempt.

Q: Considering the number of men compared to the number of women in the West, could the Earps have found “nice” women if they had looked hard enough?

Guinn: Wyatt’s eventual choice of Josephine calls into question whether he had any long-term attraction to “nice.”

In general, men on the frontier were grateful for almost any female companionship. “Availability” was often much more important than “nice.”

This is said to be Big Nose Kate Elder, who periodically lived with Doc Holliday. The identification is not authenticated, as far as I know.

I think “nice” reflects specific modern-day moral standards. As I mentioned in an earlier response, we need to see people in the context of their own times.

Q: Do you believe Tom McLaury was armed during the gunfight?

Guinn: I do not believe that Tom McLaury was armed during the gunfight.

Q: You said Wyatt was a “genuinely tough man,” but also indicated he was not discerning about politics or human motivation. Is that a good summing up?

Guinn: I think so.

Q: How much did Wyatt make running his gambling games?

Guinn: Not enough, clearly.

Q: We think of the West as a highly egalitarian place, but that’s not necessarily true is it? Tombstone seemed as socially structured as San Francisco or New York.

Wells Spicer, the judge who ruled there was no reason to put the Earps and Doc Holliday on trial.

Guinn: If anything, most significant towns in the West were even more socially structured.

Consider the guest lists for Tombstone’s major dances and balls – no Earps, male or female, were invited. The whole image of the West as egalitarian was as misguided in 1881 as it is today.

Q: Do you find it as sad as I do that Tombstone pitted the Earps against the cowboys and then turned on them?

Guinn: It’s sad but, I think, also inevitable. The Earps were used as tools by town leadership. When they were no longer useful, they were discarded.

Q: I was stunned to read how many people turned out for the cowboy’s funeral. Where did all those people come from?

“What Billy Allen Saw,” by Thom Ross. Billy was a OK Corral witness.

Guinn: We forget that Tombstone was surrounded by small ranches. The McLaurys and Billy Clanton were part of that social strata.

Lots of townspeople were attracted by the spectacle of an elaborate funeral procession.

And, almost immediately, public opinion began turning against the Earps and Doc Holliday.

Q: To change the subject to your Bonnie and Clyde book, Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde . What do you think of them?

Bonnie and Clyde

Guinn: They were the antithesis of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway (who starred in Bonnie and Clyde , released in 1967).

Essentially, they were two poor kids who through perfect timing briefly became national entertainment in a time when many Americans considered cops and bankers to be enemies.

Q: You’ve written a novel titled Glorious . What’s it about?

Guinn: I’m writing a Western series for Putnam, trying to use real history as the basis for fictional storytelling. Glorious , the first in the series, is set in Arizona Territory in 1872.

Buffalo Trail , which will be published this October, takes the protagonist into Texas and the second battle of Adobe Walls.

I want to entertain readers while still giving them a solid sense of the real frontier.

Q: What (else) are you working on?

Guinn: I’m finishing up the third Western for Putnam, and getting ready to start writing my next nonfiction for Simon & Schuster. That book will be titled, The Bitter Cup: The Life and Times of Jim Jones and Peoples Temple .

I hope to keep alternating nonfiction and novels, with all of them in some way or another concerned with real history as opposed to mythology.

Jeff Guinn

The post Jeff Guinn Talks Wyatt Earp and The Last Gunfight appeared first on .

May 29, 2015

Lawmen Who Died With Their Boots On

Readers, our society pays attention to a few Old West Lawmen while the majority, who acted heroically, are unknown and generally unsung.

But someone is paying attention.

But someone is paying attention. J.R. Sanders recently published Some Gave All: Forgotten Old West Lawmen Who Died With Their Boots On, and now you too can find out about these good men.

Sanders–who now lives in California–said his interest in the Old West began when he and his family visited the Dalton Gang hideout, Abilene, and Dodge City, Kansas.

Those famous Wild West hangouts were not a long trip, since the Sanders’ family lived in Newton, Kansas, one of the original “Wild and Woolly” cowtowns.

Sanders later became a police officer and served for fifteen years, but these days he writes, contributes to Wild West magazine, and is a member of the Western Writers of America and the Wild West History Association.

Q. Hi J.R., thanks for talking to us. I’m assuming you were interested in writing this book because you were a policeman. Is this correct?

A. Partly, I guess, although I’ve always been interested in Old West lawmen. I did hope, through the  book, to give readers a little different perspective on law enforcement, and its practitioners, in the West.

book, to give readers a little different perspective on law enforcement, and its practitioners, in the West.

There’s a great old quote by Elmer Kelton: “I can’t write about heroes seven feet tall and invincible. I write about people five foot eight and nervous.” Too often Western “law dogs” are portrayed as larger-than-life, near-invincible Terminators of the West.

I wanted to show that they were in reality normal flesh and blood folks, with the same concerns and failings we all have. I also wanted to tell some stories that hadn’t really been told before.

Q. How long did the research take, and the writing?

A. The book was about five years in the making. Research and writing were intertwined pretty much from the start, but if I were to separate them out I’d say it was four years of research and a year of writing, give or take.

Q. Did you learn anything about Western violence or law enforcement that you didn’t previously know?

Dodge City lawmen

A. Although I knew this in general, the one thing that jumped out at me as I studied these cases, and that was constantly reinforced, was that the justice system of that time functioned – some would say malfunctioned – pretty much as it does today.

We tend to have an image of Old West justice, fed by a century-plus of novels, films and television shows, as ever swift and sure. The gavel comes down, the judge pronounces sentence in somber tones, and the guilty party’s marched out back to the gallows.

But that’s hardly the case. Of the ten incidents I cover in the book, only one resulted in the lawman’s killer paying the ultimate price for his crime, and that was a year and a half later, after a mistrial, a failed insanity plea and an appeal.

Q. Who became your favorite historical character, and why?

A. I picked up a few new favorites. But if there’s one guy I could have spent a lot more time on, and may at some point write a lot more about, it would be Johnny Manning. He was on the train with Hal Gosling and shot it out toe-to-toe with two escaping prisoners.

His revolver’s ejector jammed up when he was reloading, and he couldn’t use it to knock out the empty casings. He squatted down while still taking fire from not more than ten or twelve feet away, used a pencil to punch the empties out so he could reload, then came back shooting. That’s some cool nerve. That’s a fellow I’d like to know more about.

New Castle (Co) Marshal John Morgan Rennix killed in 1910. Courtesy of the New Castle Historical Society.

Q. Many writers have attacked the Earp Brothers and their friends, accusing them of everything from assassinating their opponents (at what was later referred to as the Gunfight at the OK Corral) to being pimps and criminals. Do you agree with this assessment? (I do not and you can read my take at my website, at juliarobb.com/blog/truth-tombstone/).

A. I have to be careful when I discuss the Earps. Whatever you say about them you’re bound to tick someone off, and my views – on Wyatt, at least – tend to be outside the mainstream. But you’ve asked the question in good faith, so I’ll try and answer it without getting on too much of a rant.

I have to preface, though, with the opinion that most often gets me in hot water – that there’s no more overrated figure in all of Western history – lawman history, anyway – than Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp. That said, I think a lot of what’s said to damn him is as partisan as much of what’s said to praise him.

Whatever we think of the Earp party’s actions in O.K. Corral fracas, the evidence supports that if all the players on the other side weren’t armed, the Earps had reason to believe they were, so no one was assassinated.

At the same time, badges or no badges, I don’t believe the Earps and Holliday were acting in the interests of law and order, but rather using that pretext to settle a long-standing feud.

As for the pimps and criminals thing, Wyatt was involved in some pretty questionable dealings both before and after the Tombstone days (including an arrest in L.A., when he was in his 60s, for defrauding a faro bank).

On the whole, I think he was probably no better or worse than any Westerner whose income came largely from gambling.

Q. What fascinated you when doing the research?

A. It was all fascinating; I’m a research hound, anyway, so I had a ball. One of the most interesting and rewarding things that came out of it, though, was the opportunity to connect with several relatives and descendants of the lawmen I was writing about.

Not only were they a big help with pictures and information – though family lore and history don’t always mesh – but it was rewarding to meet people for whom the incidents I was writing about were not just stories, but a personal and cherished part of their families histories.

Q. Did you find anything that surprised you, when doing the research?

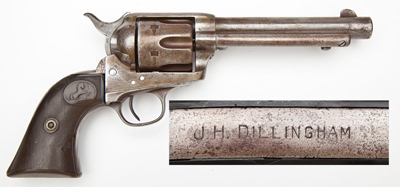

A. There were surprises with every new bit of information that I found. But my favorite surprise came after the book was released. I’d been in touch with a great-grandson of John Dillingham, the Missouri sheriff whose story I tell in Chapter 8.

Lawman John Dilliingham

I got an email from him just a couple of weeks ago and he’d learned by pure chance that Sheriff Dillingham’s Colt revolver and gunbelt, along with his handcuffs and pocket watch, had been sold at auction back in November.

They’d been in the hands of a gun collector in Florida and were sold to another collector in Ohio. So now I have a new Dillingham story to research; we’re hoping to backtrace those items from the  collectors to the family, and to the sheriff himself.

collectors to the family, and to the sheriff himself.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. I’m working on something that’s new for me – my first novel. It’s a sort of half 1930s private eye story, half Western. It takes place in Hollywood, in the world of the B-movie cowboys, but has a sort of traditional Western backstory/subplot.

It’s in final edits now and due to be released later this year by High Hill Press. The title is Cowboy Moon.

Q. Why haven’t you published on kindle?

A. I have, actually. My 2010 children’s book, The Littlest Wrangler, is available as a Kindle title. Some Gave All is not yet (published on Kindle), due to some technical issues I don’t fully understand (there’s a lot about e-books/e-readers I don’t get). The book’s pretty heavily illustrated with historical photos and other images, and apparently those present some tricky formatting issues. The publisher’s working on it.

A. I have, actually. My 2010 children’s book, The Littlest Wrangler, is available as a Kindle title. Some Gave All is not yet (published on Kindle), due to some technical issues I don’t fully understand (there’s a lot about e-books/e-readers I don’t get). The book’s pretty heavily illustrated with historical photos and other images, and apparently those present some tricky formatting issues. The publisher’s working on it.

As a confirmed Luddite who’s also a writer with a living to make, I’ll admit I’m pretty ambivalent about the whole e-book trend. That’s probably enough said.

Q. Was writing the book difficult?

A. There were challenges, as there are with any writing project. Research was a big one here. It’s a book about mostly unknown or forgotten figures, so for many of these fellows it took me a considerable amount of sleuthing to find reliable information about them.

A lot of what had been written about these incidents in the past – which was pretty limited, anyway – amounted to romanticized, dime-novelish accounts that didn’t quite match up with the known facts. On some, there was plenty of primary source material, but on others very little. In some cases, there was more data available on the killers than the lawmen.

Also, since each man’s story ended much the same – they were each killed in the line of duty, after all – it was a challenge to try and give each chapter a little different feel.

J.R.’s website can be found at jrsanders.com and you can buy the book at Amazon.com

J.R. Sanders

The post Lawmen Who Died With Their Boots On appeared first on .

May 1, 2015

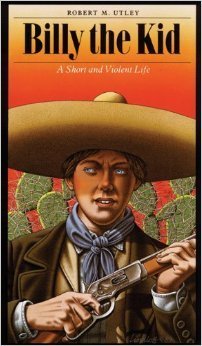

Robert Utley Talks Billy, Custer and Sitting Bull

Readers, I’m honored Robert Utley agreed to this interview. He’s a fine historian who has written many books about the American West and has been universally recognized as an authority.

Readers, I’m honored Robert Utley agreed to this interview. He’s a fine historian who has written many books about the American West and has been universally recognized as an authority.

Q–Mr. Utley, I read your book on Billy the Kid, A Short and Violent Life, published in 1989. You seemed sympathetic toward the Kid and somewhat admiring. Is that the way you feel?

A–I didn’t mean to appear sympathetic. I just wanted to find who he really was. He was not an admirable boy, in my judgment. One can admire several events in his life, such as when he took a leadership role in the burning McSween house in Lincoln in 1879 and led the group in a dash to safety amid heavy gunfire from surrounding deputy sheriffs.

Q–I recently read some historian (can’t remember who) who claimed no one really knows what Billy did and didn’t do. For instance, there’s no evidence he was the one who killed Olinger and Bell when he escaped from a room at the Lincoln County Courthouse where he was being held.

Robert Olinger

It was pointed out that an accomplice could have killed the lawmen.

A–This is all part of the clouds of myth that settled on Billy in the 20th century. I know many things Billy did and didn’t do and wrote them down in a book. Billy did kill Bell and Olinger. There is ample evidence of that.

The people in the Wortley Hotel ran to the front porch as Olinger ran under the window from which Billy shot him.

They were eyewitnesses, and some left their recollections, including Godfrey Gauss, the old German who lived behind the courthouse.

And nearly the whole town gathered to hear Billy’s speech from the courthouse balcony.

The Lincoln County courthouse. Billy gave his speech from the balcony, seen here.

(Readers, according to Utley, Billy told witnesses, “..he did not want to kill Bell but, as he ran, he had to. He said he had grabbed Bell’s revolver and told him to hold up his hands and surrender; that Bell decided to run and he had to kill him. He declared he was ‘standing pat’ against the world; and, while he did not wish to kill anybody, if anybody interfered with his attempt to escape he would kill him.”)

Q–It has also been alleged that Billy was not necessarily the same person who was born in New York City (as many believe) and no evidence who his mother was.

Pat Garrett

What do you think?

A–I believe he was born in New York City of Irish immigrant parents, but much of this story has been shown to rest on almost no evidence.

Q–Then why do you believe it?

A–I believe it because it is the most plausible explanation derived from all the meticulous research done by those who want it all in detail.

Lew Wallace

Q–Why didn’t Governor Lew Wallace keep his word to give the kid amnesty?

A–He lacked the power to grant amnesty but could have issued a pardon, which he failed to do immediately. Then Billy turned to outlawry, which made it impossible for the governor to honor his promise.

Also, the only evidence we have for the meeting between Billy and the governor is a 1901 newspaper interview with Wallace. Nothing in his papers touches on the subject. His memory may have dimmed, and he may have exaggerated because Billy had become a well-known personage.

I believe Wallace failed to keep his promise while Billy honored his.

Q–Where did the letters from the kid to Wallace come from?

A–They were obtained from Wallace’s son by historian Maurice Garland Fulton. The text appears Fulton’s book and several others.

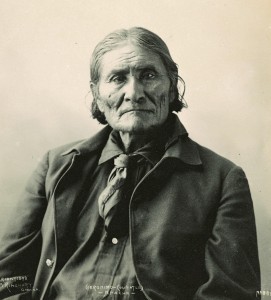

Q–How do you assess Geronimo? Some see him as a hero and some as a liar and murderer.

A–Geronimo was an Apache, a vastly different culture than our own. So he was a hero to some of his people and a villain to others. Of course he was a killer; that was the Apache way.

And he did lie on occasion. But you have to distinguish between the Geronimo before his surrender and the celebrity Geronimo became after his surrender.

One of many examples (of lying): The final Chiricahua outbreak from the reservation. The other chiefs did not want to go. Geronimo told them he had arranged to have the lieutenant in charge assassinated, then told them it had been accomplished. The chiefs knew what would happen next, so went in the outbreak.

Geronimo

As Mangas said, Geronimo “tricked them.”

Q–I’ve interviewed historians who believe George Custer was a good general who fell into unfortunate circumstances at the Little Big Horn (too many Sioux, too many unreliable officers) and some who believe Custer made disastrous decisions at the Little Big Horn.

Q–I’ve interviewed historians who believe George Custer was a good general who fell into unfortunate circumstances at the Little Big Horn (too many Sioux, too many unreliable officers) and some who believe Custer made disastrous decisions at the Little Big Horn.

Then there are the Custer haters who believe Custer was a Indian-hating psychopath.

How do assess this historical situation?

A–Custer was not an Indian-hating psychopath or even a psychopath. In fact, he wrote of his admiration of Indians. He was an exceptional general in the Civil War–major general at 24. On the plains, he scored a couple of triumphs but was excellent at self-promotion, which created an image for the people back east.

At the Little Bighorn, I believe he might have won had he been properly supported by Major Reno and Captain Benteen.

Marcos Reno

One must take into account the nature of Indian warfare. When surprised, as the Sioux and Cheyenne were at Little Bighorn, they scatter to take care of their families rather than fight in a unified manner. That makes them vulnerable to a smaller, organized force.

In all battles, however, if defeated the commander is at fault. And so Custer must be judged at the Little Bighorn.

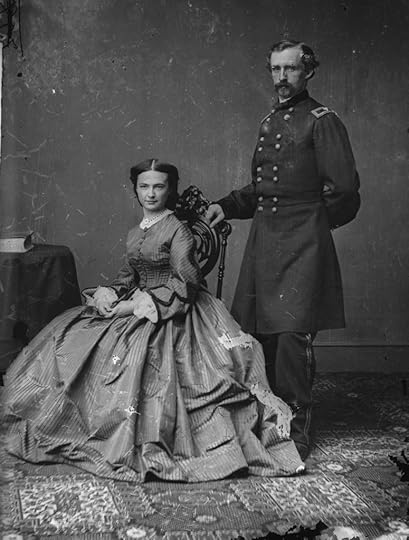

Q–Was Custer really unfaithful to Libbie and was he unfaithful with an Indian woman?

A–This is controversial. I believe, and so contended in my biography of Custer, that he was sleeping with the Cheyenne Monaseeta while in camp after the Washita fight.

George and Libbie

Q–Why do you believe it?

A–Cheyenne oral tradition, Benteen, who was in the camp, and interpreter Raphael Romero, who was Custer’s “procurer.”

Benteen

Q–Some historians believe Reno and Benteen were good officers and some believe one or both made cowardly decisions at LBH, leading to the massacre.

Which do you believe?

A–This historian believes that they were mediocre officers who disliked Custer enough to fail to give him proper support. They didn’t make “cowardly” decisions, but they did not act as they should have.

I do not believe they were good officers, although Benteen had a fine record in the Civil War.

Q–You wrote Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot. Did you choose this title? Why is Sitting Bull referred to as an American Patriot?

A–No, I did not choose the cover or the title. The book was first published in 1993 as The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull.

After a run with hardcover, it was published in the same format by Ballantine as a paperback. When that ran out, the advance on royalties had also run out, so I receive full royalty for every book sold.

But the original publisher, Henry Holt, put it out as an Owl Paperback. The size is greatly reduced, the title is changed, and the cover is much less effective.

Q–Many historians have written books about Sitting Bull, and some of them have said he was a medicine man who acted in an inspirational role at Little Big Horn, and some have said he was a war chief who laid plans for the Sioux war against the cavalry.

What do you believe?

A–Sitting Bull was indeed a medicine man, but far more. He was one of the few who practiced the four cardinal virtues of the Lakotas: Bravery, fortitude, generosity, wisdom. He was an inspiration in whatever context. At the Little Bighorn, Crazy Horse was the leading warrior.

by Thom Ross

As an “old man” in his fifties, Sitting Bull was not expected to fight; leave that to the young men.

But of course he ranged the battlefield and was an inspiration.

He laid no plans for the Great Sioux War of 1876-77. By this time had counseled his people to act simply in a defensive mode–to fight only when attacked. Earlier he led in war against the encroaching whites.

This is the point of the real title of the book: the lance for active war, the shield for defensive war.

Q–Some historians admire The Texas Rangers, like, seemingly, Sam Gwynne (Empire of the Summer Moon), and some believe the rangers were cold-blooded prejudiced killers.

Which do you believe?

A–I believe the Texas Rangers, both then and now, were fine lawmen. I have written two books with essentially that theme.

Texas Rangers

Q–Did the Rangers really attack a Mexican town during the Mexican war and kill civilians and did they really tend to shoot down Hispanics more than White men?

(Personally, I believe the rangers practiced La Ley De Fuga with all fugitives)

A–You are not referring here to Rangers as lawmen.

A regiment of Rangers was federalized to fight in the Mexican War.

With other army units, this Texas regiment (they were referred to as the Texas Regiment) fought in the Battle of Monterey, in which they played a conspicuous part.

Battle of Monterey

If civilians were killed it was part of battle in which non-Texans also participated. And no I think you are wrong in your assessment of “La Ley De Fuga.” As lawmen they did not single out Hispanics.

Q–In your book Indian Wars, written with a co-author, you have this to say: “Washburn and I breasted the popular tide by trying to show that both Indians and Whites were products of their time and place, not ours…If war resulted, it was the collision of two ways of life, not the malevolent  determination of one to overcome and victimize the other.”

determination of one to overcome and victimize the other.”

Do you still believe that?

A–Yes, I do. Washburn and I wrote at a time that Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee conditioned the public to weep for the fate of the poor Indian against the aggressions of the white people.

Rather it was as we wrote then and still is.

Robert Utley

The post Robert Utley Talks Billy, Custer and Sitting Bull appeared first on .

April 22, 2015

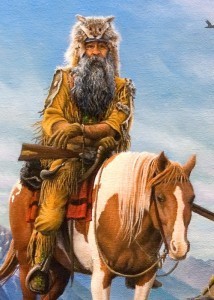

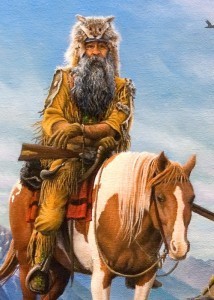

Rendezvous

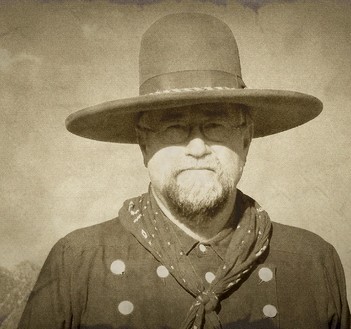

Grizzly Jim Hawthorn swaggered through Mountain Man Rendezvous, roaring “Nothing can beat this child, I’ll raise your hair, I’ll palaver you to the ground, I’m half-alligator, half-horse and all man.”

Grizzly Jim Hawthorn swaggered through Mountain Man Rendezvous, roaring “Nothing can beat this child, I’ll raise your hair, I’ll palaver you to the ground, I’m half-alligator, half-horse and all man.”

Re-enactors swarmed between hundreds of tepees and campfires, costumed in fur hats, buckskin leggings, moccasins, beards to their chests, muzzleloaders in hand and tomahawks on their hip.

Blue Rocky Mountains reared in the distance, while mountain men stooped over blankets covered with turquoise jewelry for sale, get your hand-hewn scalp poles and Arkansas toothpick knives.

Jim was happy.

In the skills competition, “Grizzly Jim” was champion. He loaded his rifle faster and threw his tomahawk closer to the target than any other mountain man.

Luckily for him, Jim didn’t begin guzzling tanglefoot whiskey–straight from his authentic earthenware jug–until he had thrown his last tomahawk and the sponsors presented his certificate of excellence.

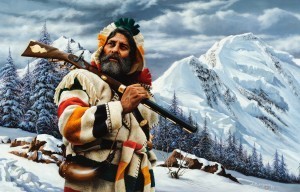

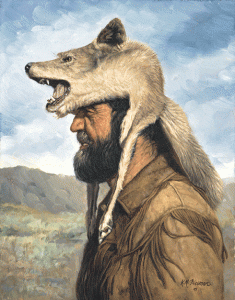

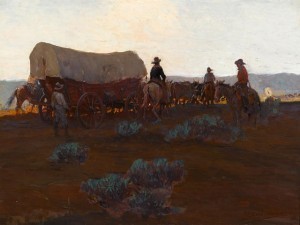

Mountain man, by Kenneth Freeman

He was Mountain Man of the Year.

Jim took a happy breath. This was the only place he felt at home and never wanted to leave.

From Monday through Friday, twelve months per year, Jim toiled at his desk in Cleveland, Ohio, at “We’ve Got Your Back” insurance agency.

Wife Kimberly had to commute further, so Jim got home first, fed the kids, plunked them in front of the TV and had dinner on the table when his wife walked in the door.

“Did you have a good day?” she asked him, nibbling Marie Callender’s (formerly frozen) lasagna.

“Well, I’m going to the gym. Can you put the kids to bed?”

“Sure.”

“I’ll just help you with the dishes.”

“I can do them.”

Truth was, he wanted her to go.

The sooner she left, the faster he could pick up one of Louis L’Amour’s Sackett stories, the ones about mountain men.

Or pop a DVD in the player, watch old Grizzly Adams episodes and plan where he would practice shooting his muzzlerloader.

Vivid dreams, in which he was the star, swam through his nights.

There he was, saving the wagon train from Indians, guiding whites through the mountains, dodging hostiles.

When he woke, he sighed, stared at his face in the mirror while he tightened his tie and tried to imagine one good thing which could possibly happen to him.

Kimberly wanted him to take her on a cruise, or just anywhere, Hawaii for God’s sake, she said.

But Jim counted the hours and days until he could leave for the rendezvous: Alone.

Finally there (“Three Days of Rip–Snorting Fun”), in the middle of his brag about being half alligator, Jim suddenly felt annoyed.

Comanche, by Thom Ross.

The enemy danced on the other side of the rendezvous–dancing to restore the buffalo, dancing to banish White civilization, dancing to bring the tribes back, to bring vanquished warriors to life.

The Snake Indians, the Nez Perće, the Sioux and the Cheyenne were meeting for an inter-tribal pow wow.

He could hear the drum and see them stomping and swaying in their one hundred percent authentic buckskin shirts and leggings, the feather bonnets, their handcrafted buffalo-hide moccasins.

Nobody asked the redskins to the rendezvous, Jim grumbled.

Trying to make white men feel sorry for them, those welfare queens, got what they deserved, why don’t they stay on the reservations, and what about all the pretty white ladies who lost their hair?

by Thom Ross

If I’d been there, I could have saved the pioneers from the savages, Jim thought.

Buckskin gripped his muscles and his tomahawk swayed at his side.

He ought to tell those injuns a thing or two, he thought and strode toward the dancers, breaking them apart.

Tribal men stumbled back, staring at him. The drum stopped.

“Come on dude, what’d you doing!” an Indian asked him, a young man with braids.

“I’m laying down the law. I want you redskins out.”

Warriors began bunching toward him, dark eyes narrowing.

“This is our powwow, what the hell are you doing, you pussy white man?” an older Indian asked, a Sioux who could have passed for Sitting Bull.

“Wait a minute, maybe he’s crazy and needs help,” the young man said, pushing the other Indians back with his arms.

“I’m the law west of the Pecos,” Jim roared, the joy of heroic combat filling his heart.

Jim reached for his knife and before the young man could dodge, he brought it down and slashed the Indian’s bare arm.

“What the hell,” the young man exclaimed, scuttling backward and clutching his bleeding arm.

Seeing the blood, Jim felt a lightning bolt of joy hit him, and he remembered he had never taken a scalp.

So Jim charged and grabbed the top of the young man’s hair.

It was an awkward scalping position.

It was an awkward scalping position.

Before he could slash at the Indian’s scalp, however, the other men grabbed Jim, punched him in the stomach and face, forced him to the ground and yelled, “9-11, 9-11, police, help.”

Later, when Jim tried to explain what happened, he couldn’t do it.

He didn’t know.

But he was so embarrassed.

He tried to scalp that injun when they were both standing up, when the only way to scalp an enemy is to knock them to the ground, make a cut on their scalp and rip the whole thing off.

What if the other mountain men saw him do something like that? They would think he didn’t know how to scalp someone.

They would think he was a fool.

He was never returning to the rendezvous, Jim thought, grateful the court let him use his credit card to post bond.

by Michael Goettee

The post Rendezvous appeared first on .

The Rendezvous

Grizzly Jim Hawthorn swaggered through the Mountain Man Rendezvous, roaring “Nothing can beat this child, I’ll raise your hair, I’ll palaver you to the ground, I’m half-alligator, half-horse and all man.”

Grizzly Jim Hawthorn swaggered through the Mountain Man Rendezvous, roaring “Nothing can beat this child, I’ll raise your hair, I’ll palaver you to the ground, I’m half-alligator, half-horse and all man.”

Re-enactors swarmed between hundreds of tepees and campfires, costumed in fur hats, buckskin leggings, moccasins, beards to their chests, muzzleloaders in hand and tomahawks on their hip.

Mountain men stooped over blankets covered with turquoise jewelry for sale, get your hand-hewn scalp poles and Arkansas toothpick knives.

Jim was happy.

In the skills competition, “Grizzly Jim” had loaded his rifle faster and throw his tomahawk closer to the target than any other mountain man.

Luckily for him, Jim didn’t begin guzzling tanglefoot whiskey–straight from his authentic earthenware jug–until he had thrown his last tomahawk and the sponsors gave him his certificate of excellence.

Mountain man, by Kenneth Freeman

He was Mountain Man of the Year.

Jim took a happy breath. This was the only place he felt at home and never wanted to leave.

From Monday through Friday, twelve months per year, Jim toiled at his desk in Cleveland, Ohio, at “We’ve Got Your Back” insurance agency.

Wife Kimberly had to commute further, so Jim got home first, fed the kids, plunked them in front of the TV and had dinner on the table when his wife walked in the door.

“Did you have a good day?” she asked him, nibbling Marie Callender’s (formerly frozen) lasagna.

“Well, I’m going to the gym. Can you put the kids to bed?”

“Sure.”

“I’ll just help you with the dishes.”

“I can do them.”

Truth was, he wanted her to go.

The sooner she left, the faster he could pick up one of Louis L’Amour’s Sackett stories, the ones about mountain men.

Or pop a DVD in the player, watch old Grizzly Adams episodes and plan where he would practice shooting his muzzlerloader.

Vivid dreams, in which he was the star, swam through his nights.

There he was, saving the wagon train from Indians, guiding whites through the mountains, dodging hostiles.

When he woke, he sighed, stared at his face in the mirror while he tightened his tie and tried to imagine one good thing which could possibly happen to him.

Kimberly wanted him to take her on a cruise, or just anywhere, Hawaii for God’s sake, she said.

But Jim counted the hours and days until he could leave for the rendezvous: Alone.

Finally there (“Three Days of Rip–Snorting Fun in Jackson Hole, Wyoming), in the middle of his brag about being half alligator, Jim suddenly felt annoyed.

by Howard Terpning

The enemy danced on the other side of the rendezvous–dancing to restore the buffalo, dancing to banish White civilization, dancing to restore the tribes.

The Snake Indians, the Nez Perće, the Sioux and the Cheyenne were meeting for an inter-tribal pow wow.

He could hear the drum and see them stomping and swaying in their one hundred percent authentic buckskin shirts and leggings, the feather bonnets, their handcrafted buffalo-hide moccasins.

Nobody asked the redskins to the rendezvous, Jim grumbled.

Trying to make white men feel sorry for them, those welfare queens, got what they deserved, why don’t they stay on the reservations, and what about all the pretty white ladies who lost their hair?

by Thom Ross

If I’d been there, I could have saved the pioneers from the savages, Jim thought.

Buckskin gripped his muscles and his tomahawk swayed at his side.

He ought to tell those Indians a thing or two, he thought and strode toward the dancers, breaking them apart.

Indian men stumbled back, staring at him. The drum stopped.

“Come on dude, what’d you doing!” an Indian asked him, a young man with braids.

“I’m laying down the law. I want you redskins out.”

Indian men began bunching toward him, dark eyes narrowing.

“This is our powwow, what the hell are you doing, you pussy white man?” an older Indian asked, a Sioux who could have passed for Sitting Bull.

“Wait a minute, maybe he’s crazy,” the young man said, pushing the other Indians back with his arms.

“I’m the law west of the Pecos,” Jim roared, the joy of heroic combat filling his heart.

Jim reached for his knife and before the young man could dodge, he brought it down and slashed the Indian’s bare arm.

“What the hell,” the young man exclaimed, scuttling backward and clutching his bleeding arm.

Seeing the blood, Jim felt a lightning bolt of joy hit him, and he remembered he had never taken a scalp.

So Jim charged and grabbed the top of the young man’s hair.

It was an awkward scalping position.

It was an awkward scalping position.

Before he could slash at the Indian’s scalp, however, the other men grabbed Jim, punched him in the stomach and face, forced him to the ground and yelled, “9-11, 9-11, police, help.”

Later, when Jim tried to explain what happened, he couldn’t do it.

He didn’t know.

The only thing he told the police, as they handcuffed him, was, “I’m half alligator and all man.”

The post The Rendezvous appeared first on .

STORYTELLER’S 7: JULIA ROBB, WAR GAMES AND OTHER ADVENTURES

If you ever have a chance to sit down with Julia Robb and chat about her award-winning days as a journalist, you’ll leave laughing, shaking your head, or gawking in astonishment.

A storyteller in every sense of the word, Julia now writes novels and works as a freelance editor. She also squeezes in time to speak and conduct workshops about all things Texas.

A storyteller in every sense of the word, Julia now writes novels and works as a freelance editor. She also squeezes in time to speak and conduct workshops about all things Texas.

Among her presentations is one where she reveals “amazing” historical anecdotes she discovered while researching her novels.

Julia did single out what she considered one of the most fascinating facts and puzzling things that ever happened in the West.

“Following the Battle of Little Big Horn (Custer’s Last Stand), a bunch of Cheyenne came to Crazy Horse’s Camp asking for help. Crazy Horse was a Sioux, one of the most famous warriors and one who helped defeat Custer.

“These Cheyenne had participated in the Little Big Horn battle and were Sioux allies. They were hungry and had nothing to feed their families.

“Crazy Horse desperately needed every man he could get, to help defeat the OTHER white soldiers, who were now after him–as the U.S. Army didn’t appreciate what the Sioux did to Custer and his command. But what did Crazy Horse do? He turned these warriors away and wouldn’t help them.

And what did the Cheyenne do? They rode to the nearest U.S. Army command and offered to scout against Crazy Horse and the other Sioux. Which they did.”

Julia has written three novels. One review describes her writing and “exciting and excellent.”

Another remarked that “Julia Robb proves that she has mastered more than just the craft of writing: she also possesses the art.”

STORYTELLER’S 7

1. You spent 20 years in the newspaper business. In fact, you’ve won several awards. What did you do and how much do you miss it?

I covered everything from jalapeño eating contests—most of the contestants immediately threw up every pepper in their stomachs in full sight of the spectators—to cops.

Like the time one drug dealer chased another down the street with a butcher knife, stabbing the victim every step of the way, finally cutting the poor guy’s throat.

I was also sent to Florida with the Maryland National Guard, to play war games.I was forced to hold my notebook above my head when we forded swamps, to keep it dry.

The first morning out, the “enemy” ambushed our camp and the guy with whom I was sharing a foxhole exclaimed “I just love the smell of gun smoke in the morning.” Right, he stole that line, with a slight variation, from Apocalypse Now.

Can you imagine saying that! I quoted him. Of course, the enemy was shooting blanks.

Once, a murderer—who was convicted and sent to prison—confessed to me. Can you imagine my astonishment? And then the cops called me up and accused me of ruining their case.

I guess they were afraid they could not enter the story in court evidence and the defense could ask for a dismissal based on something or another.

I enjoyed writing features and hated covering politics. I was able to interview many famous people, which was instructive.

California Governor Jerry Brown was fun. This was when he was governor the first time, in the 70’s, and he was a big flirt.

Sometimes, reporting provided thrills that not everyone would understand. Covering a Maryland anthropologist who reconstructed faces allowed me to touch ancient bones.

But I don’t miss reporting: Too much stress, every day in every way.

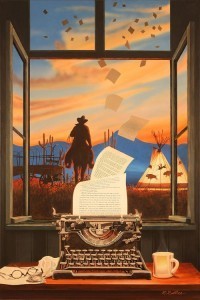

2. There are quite a few journalists turned novelists. What inspired you to start writing fiction—and especially Westerns.

I believe novelists are born, not made. Many born novelists mistake the call and enter journalism.

I believe novelists are born, not made. Many born novelists mistake the call and enter journalism.

Only later do they understand they want to tell imaginary stories, to empty the contents of their unconscious minds and force the world to make sense, on their terms.

That’s what we do. The characters’ conflicts are our conflicts. We transfigure those conflicts, but they are ours.

Writers are usually triggered by something; and this is where my Westerns come from.

The sea triggered Joseph Conrad and the cultures he observed in his ports of call. The Great Plains triggered Willa Cather. And, I was triggered by Texas—and I hate to write my name in the same sentence as Conrad and Cather, as they were great, great writers.

That’s why I wrote Scalp Mountain. I was attempting to say something about the Indian Wars waged here in Texas—what both sides did to each other.

I was also inspired by West Texas, where I grew up, the plains reaching for an ever-receding horizon, and its tiny, dying towns. That’s where Del Norte came from.

The long struggle between Texas Hispanics and Texas Anglos inspired Saint of the Burning Heart. Finally, about Saint, why can’t Nicki just give Frank up?

3. If someone asked you to describe the kind of stories you write, how would you answer them?

That’s hard because there’s a difference between what we think we write and how other people perceive it.

I think I write historical novels but most people refer to them as Westerns.

Even the Kirkus reviewer called Scalp Mountain a Western. I believe a historical novel explains the why of a place and a Western explains the how. But, whatever.

Many of my reviewers have said my novels are “dark.” Huh? I consider them full of light and redemption.

4. What is your approach to the storytelling process? Once you’ve got the ideas, walk us through what kind of steps follow.

I start with an image I see in my mind and that’s all I have.

I start with an image I see in my mind and that’s all I have.

Scalp Mountain began with seeing Colum searching for a place to establish a horse ranch, alas, a doomed idea.

Del Norte began with seeing a tombstone propped against the back wall in Magdalena’s saloon.

Saint of the Burning Heart Saint began for me with the last scene. (Can’t tell you about that).

From there, it’s like growing vegetables. Who is this guy Colum? Why did Magdalena put her father’s tombstone in the saloon rather than the graveyard?

5. What’s the best piece of writing advice you every received?

I was struggling with a novel and my sister-in-law, Vicki, said, “Just tell the story, Julia, just tell the story.”

Admirable advice, highly helpful, yes indeed that’s why we have sisters-in-law, so someone will give us advice like that.

6. If you could travel back in time to the American Frontier, what would you be doing and what three characters would you be eager to meet and why?

Being an Indian scout for the Army has its attractions. Being out in the open yet having a task which provides structure—I enjoy searching for things— or perhaps establishing a ranch and making it into a home, or even being an itinerant gambler. I also enjoy playing games.