Julia Robb's Blog, page 3

October 21, 2016

Kit Carson, Blood and Thunder: An interview with Hampton Sides

But the book is also a tour through America’s Western conquest.

Kit Carson just happened to be the man who made acquiring everything from New Mexico to California possible, thus we get a ringside seat by just following him.

Sides, author of numerous non-fiction histories, made me feel I was there: And it was thrilling.

(By the way, Doubleday is publishing Sides’ new book in 2017. It’s about one of the most harrowing battles in American history, the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, in the Korean War. It’s tentatively titled “Mountains of Fire and Ice.”)

Here’s my interview with him.

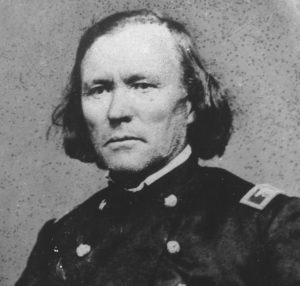

Kit Carson, by George Stuart.

Robb: As I was reading your book, it seemed to me Kit Carson’s personality was very like the Indians he associated with and fought (and sometimes married); for instance, his beliefs in omens and bad medicine, his refusal to take a second shot if his first missed an animal, his dependence on intuition in sizing up people and situations.

Is this how you see it?

HAMPTON SIDES: Absolutely. Kit Carson spent most of his young adult years living more like a Native American than an Anglo American.

From the Indians he befriended, he developed all sorts of little quirks, protocols, and superstitions, if you want to call it that. Perhaps being illiterate, as he was, forced him to rely more on his hunches and instincts, many of which were honed by his years as a mountain man, living among the tribes. He spoke a half-dozen Indian tongues.

Some of his happiest days were the ones he spent with the Arapaho, his first wife’s tribe.

Arapaho camp, 1880’s.

It’s remarkable that he’s known now, mistakenly, as this great Indian hater. Nothing could be further than the truth.

Robb: Kit Carson also seemed to be an admirable man in the way the Anglo civilization saw admirable: Modest, responsible, abstemious in his habits (he drank very little), a dry sense of humor and a great frontiersman.

You wrote he often saved people’s lives without expecting payment, was truthful and kind.

Kit Carson’s hatchet.

Yet, you called Kit Carson a “natural born killer.” You described his temper, his vengefulness (“If you crossed him, he would find you”), the way he described battles as “pretty,” and a preemptive attack on an Indian village as “a perfect butchery.”

Did the place make the man, or did the man find his natural place?

HAMPTON SIDES: Both, I think. The place accentuated the nascent tendencies that were already there in the man. Kit Carson did have this very sweet side to his personality, one that’s hard to reconcile with some of the more violent episodes throughout his career in the West.

From his family in Missouri, and from his Scotch-Irish background, he probably inherited a certain temperament, a zest for the fight, and a penchant for pursuing a grudge.

But then you plunk that personality in the vast uncharted wilderness of the West, a thoroughly violent and unpredictable world without laws, and you have a very explosive character on your hands.

Robb: You wrote that Kit Carson was not an Indian hater, but rather someone who had many Indian friends, befriended Indians, married two Indian women and always killed in what he believed were fair fights.

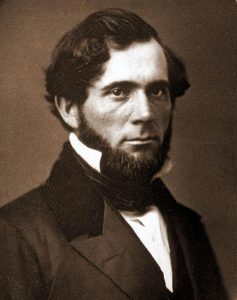

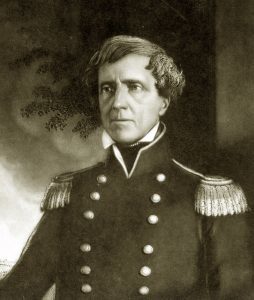

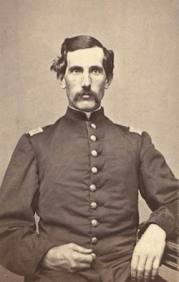

John Charles Fremont

Do you find it ironic that Kit Carson opened the West for settlement through his explorations with John Fremont (“The Pathfinder”), which in turn destroyed the Indians’ way of life? Wasn’t this inevitable? Wouldn’t another scout have done it, if Carson had not been born?

HAMPTON SIDES: It is tremendously ironic, tragically so. The great theme of Carson’s life was that, wittingly or not, he fouled his own nest, he destroyed his own paradise, he set in motion great forces that systematically dismantled the raw wilderness of the West that he knew so well and loved so much.

The Fremont explorations ignited a surge of immigration that, in turn, led to

the wholesale devastation of the Native American tribes. Carson wasn’t fully aware of it at the time, but he was at the very center of the movements that destroyed the world he held so dear.

the wholesale devastation of the Native American tribes. Carson wasn’t fully aware of it at the time, but he was at the very center of the movements that destroyed the world he held so dear.While it’s true that someone else might have done it if Carson hadn’t, it’s especially poignant and rich that it was Carson who became the leading edge, leading Fremont, and effectively the entirety of Anglo-American capitalistic-industrial society, into the Western wilds.

Said to be Navaho slaves.

Robb: I appreciated your not making any one people the bad guys. For instance, pointing out that Navahos took Hispanic slaves and the Hispanics took Navaho slaves, telling the reader what the Jicarilla Apaches did to captive Ann White (forcing her to be the band’s prostitute, then murdering her), making it plain that all the peoples fighting against each other took scalps.

Is that how you see it, that all three races (Indian,

Hispanic and Anglo) were equally savage?

Hispanic and Anglo) were equally savage?HAMPTON SIDES: I suppose so. We’re all humans, we all have the same DNA, the same capacity for good and evil. The only real difference was, Anglo Americans had the tools—the social structures, the technological advances, the guns, germs, and steel, as they say—to turn their will into a reality and transform life on a huge scale.

So, in the end, Anglo Americans were more effective in their savagery.

Robb: You have written many vivid scenes in this book, among them the murder of Charles Bent, Kit Carson’s escape at the Battle of Pasqual, the Klamath attack on Carson and the men he was traveling with, the (first) Battle of Adobe Walls, and many more. In writing this book, what historical episodes affected you most? Were you affected?

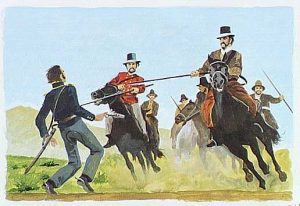

The Day After the Battle of Adobe Walls, watercolor, by an unnamed soldier with Carson’s command. Dated November 26, 1864.

HAMPTON SIDES: You can’t write a history of this period and not be affected. There was so much bloodshed, so much tragedy, so much turmoil. So many forces were colliding: Indians clashing with Mexicans. Mexicans clashing with Americans. Americans clashing with Indians. Americans clashing with fellow Americans (during the Civil War).

The Battle of Pasqual, the inconclusive battle between American forces and combined force of Mexican and loyalist Californio militias and lancers during the formers efforts to capture Los Angeles during Mexican War in December of 1846. This painting depicts the death of Capt. Benjamin Moore. Fort Moore Hill in Los Angeles is names in his honor.

What’s extraordinary is how much of all this Kit Carson witnessed and participated in. Time and time again, he’s right there, in the middle of it, a kind of Zelig figure, bouncing around all over this vast canvas of real estate.

You keep wondering: What’s he doing there? How’d he get there? He always seems to be in the thick of the action. Or if he’s not, he’s only one degree of separation from it.

Of all the episodes of his long and eventful life, I would say his conquest of the Navajo was the most difficult to write about. It’s almost as though everything in his life funneled down to that one conflict and that one place—Canyon de Chelly, in the heart of Navajo country.

Canyon de Chelly

Here a reluctant conqueror flips a switch and brutally brings this proud tribe to its knees. The destruction of those peach trees down in Canyon de Chelly—a militarily small but somehow a devastatingly powerful act—still haunts me.

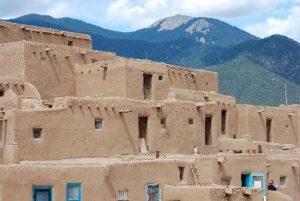

Robb: I was astonished to read about the Pueblo and Hispanic revolts in Santa Fe and Taos against the American invaders. That was pretty savage. Do the New Mexicans remember these things, or has the memory faded, or even disappeared, with time?

Taos Pueblo

HAMPTON SIDES: Oh yes, it’s still very much there, in the cultural memory here, and it’s studied to a certain extent in the schools. New Mexicans, especially those from a Native American or Hispanic background, are very clear on the fact that the United States Army came here and conquered this place by force and then occupied it against the will of the inhabitants.

They’re very clear, also, on the fact that some of those inhabitants actually rose up and tried—however crudely, however savagely—to throw out the hated occupier.

Gen. Wool entering Saltillo with his troops, 1847.

Here in New Mexico there is still hostility, sometimes overt but usually just under the surface, towards the Anglo-American presence. It’s a kind of asterisk attached to life here, that basically says: New Mexico may be part of the US of A, but make no mistake, this place was stolen.

Robb: Who was the next strongest personality in the West of that period, after Kit Carson, and why? Was it the vainglorious John Fremont? Stephen Kearny? The Navajo leader Narbona, or even President James Polk, the man who single-handedly conquered Mexico from his desk in The White House?

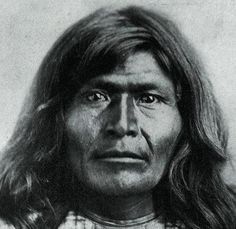

Narbona

HAMPTON SIDES: That’s a really tough one. There are so many. There are hardly any “weak” characters from this period. Something about the harsh demands of the place and the times made people resilient and strong.

That’s one of the reasons, I think, why we’re drawn to stories about the Western frontier. Life was just so hard, so raw, so unforgiving, and so violent that it brought forth unbelievably stark and stout characters.

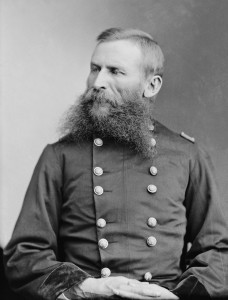

Stephen Kearny

Probably my favorite character in the book, after Carson, is General Kearny. I’m convinced he was one of the most enlightened and most professional officers in the US Army, one of the rare bright lights in the whole story of the “winning” of the West. Kearny was principled, fair-minded, and firm. He carried himself with dignity but was not haughty or arrogant.

In his writings and speeches, you see a certain empathy for Native American culture, and for Spanish-Mexican culture, that sets him apart from most of the racist thinking common in Washington. If we’d had more officers like him, I believe the story of the Western conquest, brutal and brazen as it inevitably was, might have been a lot less tragic and a lot less bloody.

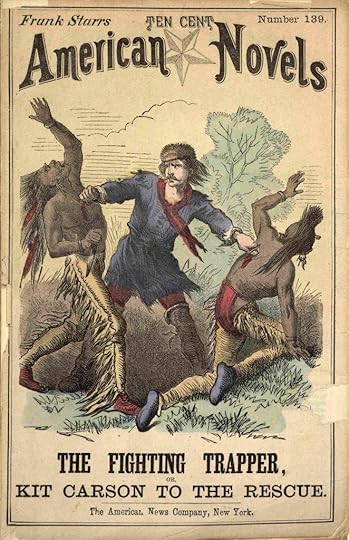

Robb: Carson and Davy Crockett had very similar lives. Both were renowned frontiersmen who became famous through fiction. Davy became famous through a play, and then his death at the Alamo. Kit Carson became famous through “blood and thunder” pulp novels.

I find this amazing. What about you?

HAMPTON SIDES: It is amazing. Carson was perpetually confused and bemused by his own celebrity. He didn’t understand why people back East seemed to need to fashion him into a hyperbolic hero, an action figure hero, a folk hero. He didn’t understand where it came from, why writers were making so much of his real exploits, and then fictionalizing them into even more fabulous tales of derring-do.

Kit Carson was the subject of countless newspaper articles, a Broadway play, numerous books. A large steamship and a clipper ship were named after him. In Moby Dick, Melville compared Carson favorably to Hercules.

And then there were all those “blood and thunder” pulp novels. Carson hated them, and spent much of his life fighting the caricatures and unrealistic expectations they raised.

The writers of those lurid tales never sought his permission to use his name, and he never saw a cent from them. He hated those books, also, because (and here’s the ultimate irony) . . . he couldn’t read them.

Carson was illiterate.

Carson carved this

Hampton Sides

The post Kit Carson, Blood and Thunder: An interview with Hampton Sides appeared first on .

August 29, 2016

Jesse James Rides Again through author Mark Gardner

Readers, Mark Gardner wrote this book about Jesse James and his gang, and it’s so fascinating I read it twice.

Gardner is a wonderful researcher and writer, and so far has also written about Billy the Kid and Teddy Roosevelt. He’s also a talented musician.

So, without further ado..

ROBB: In the book, you made it plain that the James-Younger gang, particularly Jesse, was popular with the public.

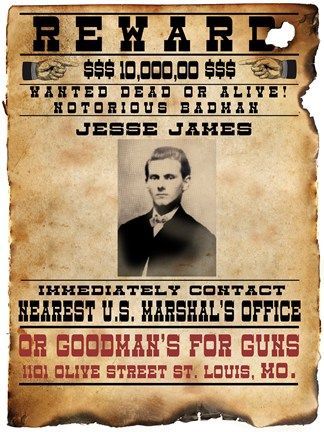

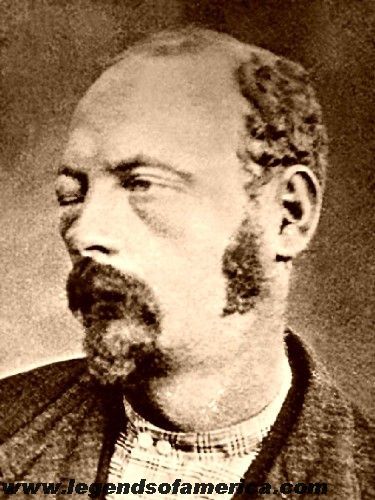

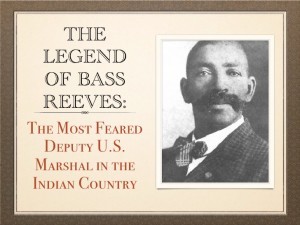

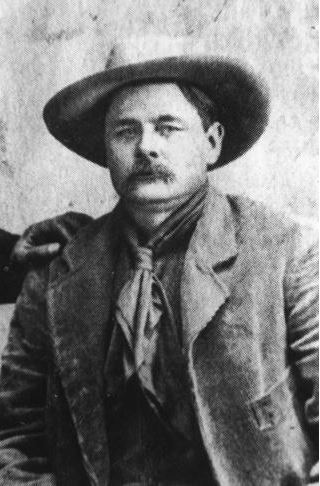

Jesse James

You wrote, “No gang of criminals were more feared, more wanted, more hated and more celebrated.” You also said a newspaper editorialized the gang who robbed the train near the Lamine River as “Cool and courageous” and “dashing knights of the road.”

Why this admiration? Although it’s true the gang were all Confederate ex-partisans, and they knew their enemies in Missouri were going to constantly harass them after the war, didn’t you also say banks were not insured in the 19th century?

Weren’t the gang stealing from the people who deposited their money in the banks they robbed?

Jesse as a teenager, when he was riding with Bloody Bill Anderson.

GARDNER: Wayman Hogue, who grew up in the Arkansas Ozarks in the 1870s and 80s, wrote in his autobiography, Back Yonder, that the mountain people not only considered Jesse James a hero, but they “held him up before their sons as an example of the ideal man.”

Hogue didn’t find this surprising: “It is one of the characteristics of human nature to worship at the shrine of anyone who excels in any line, let it be for good or for evil.”

The success of the James-Younger gang, combined with the audaciousness of their robberies, struck awe in many people, including journalists.

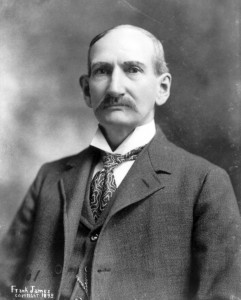

Frank James

And the fact that the gang pulled off the Rocky Cut robbery (near Otterville, Missouri, July 7, 1876), for example, without anyone being shot or killed, made it seem okay to admire what the outlaws had accomplished.

As one newspaper wrote, “No one was hurt, and no one loses anything save the express company.”

That last line is important. As long as it was someone else losing their money, it was pretty easy to idolize the “bold outlaws.”

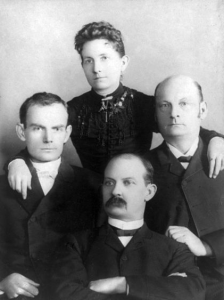

The Younger brothers, who rode with Jesse and Frank, left to right, Bob, Jim and Cole, with sister Henrietta.

As for the banks in post-war Missouri, I think you would find that few of those who admired or tolerated the James-Younger gang – ex-Confederates and Southern sympathizers – had money in the banks.

A lot of Radical Republicans did, though.

ROBB: Did bitterness about the war, and having enemies, really motivate the James-Younger gang? After all, they could have left Missouri, moved to California and started new lives.

GARDNER: I think the chance to line their pockets with lots of cash was a pretty strong motivator. But at the same time, there was bitterness and a feeling amongst the gang that they were being persecuted, especially after their run-ins with Allan Pinkerton’s detectives.

Jesse and Frank’s eight-year-old half brother was mortally wounded when the Pinkertons conducted a disastrous midnight raid on the family farm in January, 1875; their mother was maimed for life. The Youngers lost a brother in a shootout with Pinkertons in south Missouri a year earlier.

Allan Pinkerton, owner of the detective agency and Jesse’s mortal enemy.

I don’t know that we’ll ever know with one hundred percent certainty what motivated these men to live the life of outlaws, but I think it’s safe to say that most of them did it with chips on their shoulders.

ROBB: Do you have any estimate of how many banks and trains they robbed in 11 years, from 1866 to 1876, and number of men they killed?

GARDNER: Hard to say, because the gang personnel changed over time, and there are some robberies where we suspect it was the handiwork of the James-Younger gang but can’t confirm.

For example, the first robbery that, because of the evidence, there is no question that Jesse was a participant was the robbery of the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin, Missouri, on December 7, 1869 (and that may have been a planned murder disguised as a robbery).

A good website that attempts to tackle the question of who possibly took part in the several robberies associated with the different permutations of the gang is found here:

http://www.civilwarstlouis.com/Histor...

ROBB: Jesse seems like an interesting person. You described him as always laughing, light hearted and reckless and brave, but egotistical.

But why did he constantly write newspapers denying he committed such and such a robbery if he enjoyed being the most wanted man in the U.S.? Was that really his way of bragging the gang did it and taunting the law?

Jesse and Frank

GARDNER: Certainly Jesse liked the attention, but his published letters were also propaganda. By strongly professing his innocence and ranting against Missouri officials (Republicans) and especially the Pinkertons (based in Chicago), he maintained the sympathies of pro-Southern Missourians.

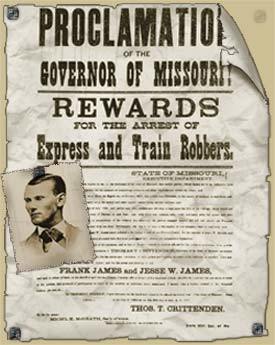

Jesse was also angling for full amnesty, and he came close. An amnesty bill was brought before the Missouri legislature in March of 1874, but was defeated by a small margin.

Jesse’s family farm in Missouri.

ROBB: Jesse seemed to glory in his notoriety, but what did he think would happen. That he would never be caught?

GARDNER: I’m guessing most Wild West outlaws believed they wouldn’t get caught.

ROBB: How did they get away with the crimes for 11 years. They seemed to stand out in a crowd. You wrote they had “striking physiques,” they dressed differently than others, pushing their pants inside knee-high boots, wore big spurs, wide-brimmed hats and all of them wore dusters, plus they had strong Missouri twangs.

Northfield, Missouri, Jesse’s downfall.

GARDNER: The outlaws did stand out in Minnesota, but the gang always had a plausible explanation for the curious: they were miners on their way to the Black Hills, or cattle drovers. The idea that these unusual-looking men were the notorious James-Younger gang was the farthest from people’s minds.

And it’s important to remember that there were no good photographs of the outlaws available at the time (the gang members’ families made it a point to keep any photos secret). Unless you went to school with Jesse or Frank, you would have no clue as to their real identity.

And it’s important to remember that there were no good photographs of the outlaws available at the time (the gang members’ families made it a point to keep any photos secret). Unless you went to school with Jesse or Frank, you would have no clue as to their real identity. In fact, so unconcerned was the gang about someone identifying them that they rode in a train to Minnesota and freely went about in public once they got there.

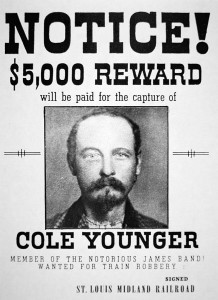

ROBB: Why was Cole Younger sent to prison for years for his part in the Northfield bank robbery, while Frank James got a pardon; particularly when it was Frank who murdered the heroic Joseph Heywood, the bank accountant who refused to open the vault.

Joseph Heywood

GARDNER: Actually, Frank was never pardoned. He was subjected to two criminal trials after his surrender to the Missouri governor in 1882 and was acquitted at both. Now, had Frank been extradited to Minnesota and been tried for the murder of Joseph Lee Heywood, he very likely would have been convicted and sentenced to death.

However, a key part of the deal for his surrender was a promise from Governor Thomas Crittenden that Frank would not be sent to Minnesota. And, indeed, Minnesota’s governor did send a requisition for Frank in January, 1883, but Crittenden declined to honor it.

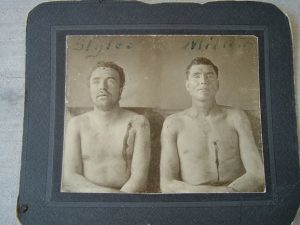

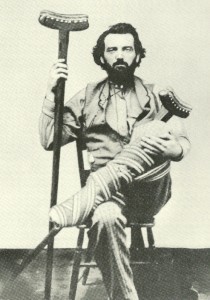

Cole Younger after being injured in the Northfield, Minnesota raid.

Cole, of course, was captured in Minnesota red handed, so to speak, along with his brothers, Jim and Bob. He and his brothers probably would not have spent so many years in Stillwater, however, if they had identified the two robbers who got away after the Northfield debacle: Frank and Jesse James.

The Youngers refused to name names – and they were asked countless times.

Cole, the last surviving Younger brother, was released from parole by the Minnesota pardon board in 1903 and allowed to return to Missouri, where he reunited with his old friend Frank James. The two toured together for a few short months as part of The Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West.

ROBB: Your chapter on the Northfield bank raid was fascinating. It seemed to shock the gang that the Northfield citizens fought back. Now remind me, why did Jesse escape? Everyone else was killed in Northfield or captured after that long chase through the Big Woods, correct?

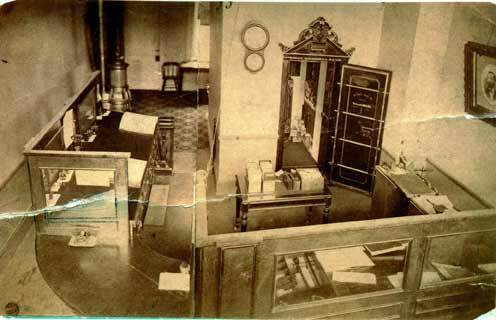

Interior of the bank in Northfield

GARDNER: During their flight across Minnesota, the surviving six members of the gang decided to split up southwest of Mankato.

Most of the men had serious wounds to contend with, but Bob’s shattered elbow was extremely painful, and he required frequent rest, which slowed everyone down (they were on foot at this time).

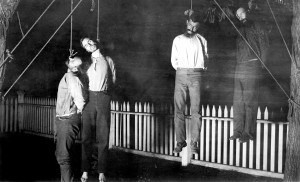

Two of the gang killed in the Northfield raid. This photo was taken after death.

So, Frank and Jesse separated from the Youngers and Charlie Pitts. The James boys stole a pair of horses almost immediately afterward and were able keep in horse flesh for the remainder of their escape, thus allowing them to stay ahead of the posses.

Had the Youngers and Pitts also been able to acquire some mounts, they might have made it out of Minnesota as well. That didn’t happen. In a shootout with a posse on the Watonwan River near Madelia, Charlie Pitts was killed and the Youngers captured.

ROBB: In the movie about Jesse James, starring Brad Pitt, Jesse gets on a ladder to hang a picture, or something like that, and sees, in the glass, Robert Ford take his gun out, preparing to shoot him in the back. And he lets Ford do it.

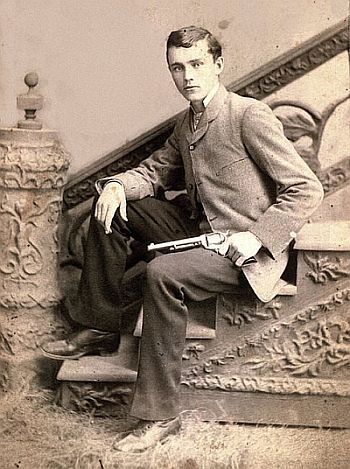

Robert Ford, the “Dirty little coward.”

Although that was just a movie, I wonder if something like that could have happened in real life? Wasn’t Jesse suspicious of Ford? Was Ford Jesse’s way out?

GARDNER: The Ford brothers later said that they believed Jesse had become suspicious of them. It would be pure speculation as to what was going through Jesse’s mind before Bob Ford pulled the trigger on his revolver.

But we do know that Jesse James had a wife and two children whom he loved. He also appeared to be planning for the future. Just a month before his assassination he had inquired about a 160-acre farm that was for sale in Nebraska.

Jesse, after death

That doesn’t sound suicidal to me.

Mark Gardner

The post Jesse James Rides Again through author Mark Gardner appeared first on .

July 29, 2016

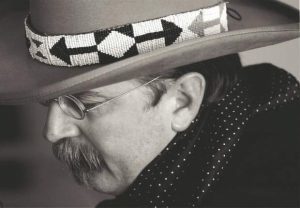

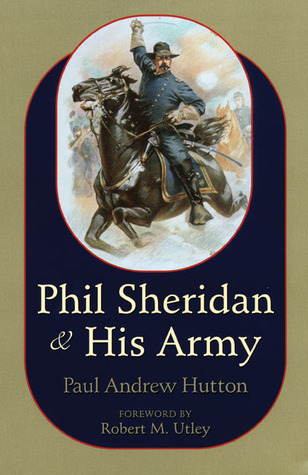

General Sheridan and the Indian Wars: Paul Hutton Speaks

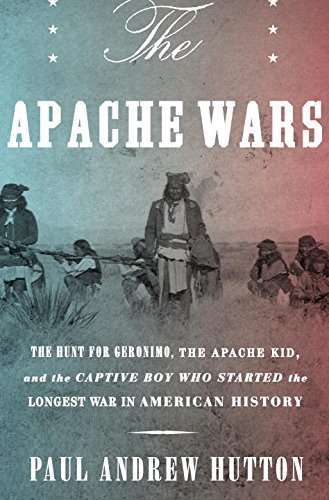

READERS, Many of you know historian and author Paul Andrew Hutton from his recent book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History.

READERS, Many of you know historian and author Paul Andrew Hutton from his recent book, The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History.

You can find my interview with him, about that book, on this website. http://juliarobb.com/blog/from-cochis...

But Hutton also wrote Phil Sheridan and His Army, (a Spur Award winner) and that’s what this interview is about.

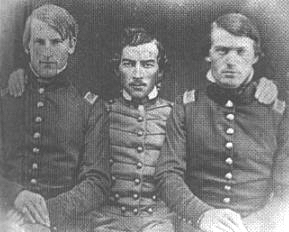

Gen. Sheridan was one of the Union’s most important heroes during the Civil War, and, from 1867 to 1883, served as commander for the Department of the Missouri, the jurisdiction of which stretched from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains and from Mexico to Canada.

Sheridan, middle, at West Point

The Northern Plains were included in his command. This, in turn, meant he was also the commander in charge of most of the Western Indian wars.

It’s not possible to discuss America’s Indian Wars unless we also discuss Sheridan.

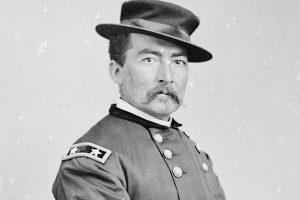

Sheridan

Robb-Welcome Paul Hutton. You wrote that Sheridan was intellectually limited. What did you mean by that? Would you use as an example Sheridan’s failure to realize the difference between the Northwestern Indians and the Great Plains’ tribes in terms of what it would take to pacify them? Wasn’t that just a learning curve?

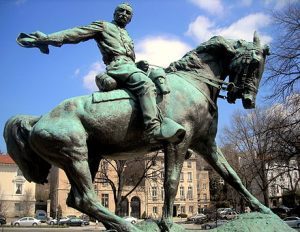

The general on his horse. Statue located at Sheridan Circle, Washington, D.C.

HUTTON–Sheridan was not a cerebral man—he was a man of action. While a brilliant tactical combat officer he had neither the patience nor the intellectual capacity necessary to comprehend the task of dealing with the wide variety of native peoples in the West.

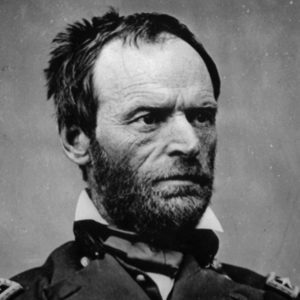

Of course General Sherman, who was clearly an intellectual giant, dealt with the Indians in much the same way.

Gen. Sherman

The bottom line was that they had a job to do—dispose of the natives and open the West to white settlement as quickly as possible.

Sheridan did that job and did not lose any sleep over its morality.

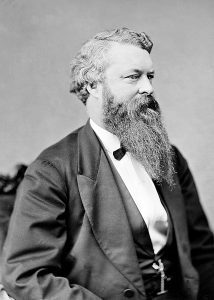

Robb-Although, overall, Sheridan seems to have been an admirable general, you fault him for many things, among them not supporting Custer in his “courageous act” of testifying against corrupt Secretary of War William Belknap.

Belknap

HUTTON-The problem for Sheridan in the West was the dual issues of administration and Indian policy. He pretended that he could not influence policy—that all he could do was fight—when in reality he had enormous influence. His knee-jerk defense of atrocities—such as Camp Grant and the Marias Massacre—undercut his position in the East. He preferred to pretend that this was not a political problem when in reality it totally was.

Robb-Sheridan seemed almost a physically challenged person, as if he had been born with birth defects; the long upper body and extra-long arms joined with super-short legs. Has medical science ever guessed what was wrong with his skull, regarding the two large bumps?

HUTTON—Sheridan was indeed oddly shaped, which may well have added to his pugnacious nature. He looked grand on horseback and was a marvel on the battlefield. The years were not kind to him as he quickly gained weight after the war. He also suffered from heart disease (undetected at the time) which carried him off prematurely.

Robb-After reading your book, it appears neither the whites or tribes had any idea what the other side meant when they were supposedly communicating. For instance, the Cheyenne failed to understand they were signing a treaty giving up a good portion of their land, as they did at Medicine Lodge in 1867.

Paper that talks two ways, by Howard Terpning.

HUTTON—Actually, neither the Indians nor the government understood how quickly the West would be settled. The railroad changed everything. Settlement that had taken 200 years to reach the Missouri River now swept over the rest of the continent in 25 years.

It was all over in a generation. Geronimo’s 1886 surrender ended nearly 400 years of the European struggle to conquer the North American continent.

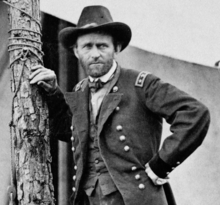

Robb-The general (uninformed) public believes Custer was ruthless, yet of the two, Sheridan seems much more punitive toward the tribes than Custer.

Custer

HUTTON—The public perception of Custer is ludicrous. He was a lieutenant colonel of cavalry and yet popular culture has made him the central character and grand villain of the Indian Wars.

He was once famous as a martyr to Manifest Destiny so it was only natural that he should become the villain of the story once societal attitudes changed in the 1970s.

Sheridan was, of course, far more brutal toward the Indians. He meant what he said with, “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Robb-Sheridan seemed to have mixed feelings about Custer, admiring his contributions in the Civil War so much he gave Elizabeth Custer the table on which Robert E. Lee signed the surrender.

Sheridan is standing with the Union officers, far left.

Yet Sheridan said Custer was as “boyish as be was brave” and (was) “always needing someone to restrain him.. too impetuous; without deliberation; he thought of himself invincible and having a charmed life.”

HUTTON—Custer was Sheridan’s pet officer. He won that position by boldness and success during the Civil War. Custer was the premier combat officer for the Union’s premier combat officer.

They were a mutual admiration society. Sheridan, however, had no illusions about war—it was a dirty business—while Custer wallowed in the romance and glory of war. That endeared Custer all the more to Sheridan.

They were a mutual admiration society. Sheridan, however, had no illusions about war—it was a dirty business—while Custer wallowed in the romance and glory of war. That endeared Custer all the more to Sheridan. Still, when Custer attacked Grant’s administration in 1876 he lost Sheridan’s support. Sheridan was devoted to Grant. It was Sherman who got Custer restored to command of the 7th.

Grant, at Cold Harbor

Nevertheless, Sheridan wanted Custer in the field, because Custer was the best the army had. Sheridan was devastated by Custer’s death.

Robb-Didn’t you note that the only successful tactics ever used against the northern tribes were the ones Sheridan dreamed up; winter campaigns and destroying the tribes stores and horses?

HUTTON—Sheridan employed the same total war tactics against the natives that he had used so successfully against the rebels in the Shenandoah. He destroyed their means of sustenance-the buffalo-and attacked them in their winter camps. The attacks on villages were a step beyond the Civil War because the Indians were viewed as a savage inferior race.

Battle of the Washita

Although there were civilian casualties in the Civil War they were either incidental or accidental, but the Indian campaigns targeted noncombatants much like the bombing raids of World War II.

Clara Blinn, white captive killed by Indians, with her son Willie, at the Battle of the Washita.

Robb-Was Sheridan the best general for the times?

HUTTON—Sheridan was in many ways the perfect general for his times. His pragmatism and elastic ethics made him a good fit for the unpleasant task of crushing the resistant natives. He was determined to destroy the enemies of Union—be they rebels, striking workers, or western Indians. And he was a success at this task, like it or not.

Capt. John Bourke

Robb-It surprises me the Sheridan assigned Capt. John Bourke (one of my favorite historical characters) and Capt. William Clark to study and publish information about the tribes and their cultures. What does this say about Sheridan?

HUTTON-He also was sensitive enough to recognize that something important was being lost and so he sponsored the work of Bourke and Clark. He also sponsored Capt. Pratt’s experiment in Indian education.

Sheridan was a complicated man, and I hope that my biography of him captured that.

Robb-In your book, as well as many others about the Indian Wars, you draw up a strong case that many of the problems between the Army and the tribes stemmed from Congressional inaction and delay. For instance, the failure to allocate money for the tribes (for a year) following the Treaty of Medicine Lodge.

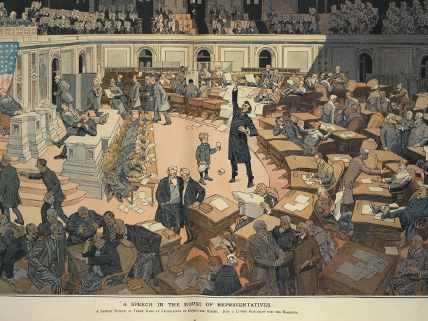

HUTTON—The level of inaction, corruption, and general stupidity on the part of the US Congress regarding the Indians is simply mind-boggling.

Congress in session, 19th century

The politicians made the mess that the soldiers then had to clean up. Then Congressional leaders condemned the army for doing its job. Nothing has changed. General Sherman once declared that “Congress should be impeached!”

Robb-As Robert Utley noted, the frontier army is accused of many things, among them wantonly slaughtering women and children. What do you think of the frontier army in terms of honor and effectiveness?

HUTTON-These were Victorian gentlemen with a high sense of honor. The slaughter of women and children was not condoned, but race nevertheless played a role in their approach to war.

These officers never would have galloped into a rebel town at dawn shooting down anyone who moved, yet they did that to Indian villages. They also took Indians as mistresses–certainly Custer did after the Washita.

So race played a key role in tempering their high moral code of conduct, just as it did with British soldiers on colonial duty in the same period.

Paul Hutton

The post General Sheridan and the Indian Wars: Paul Hutton Speaks appeared first on .

June 30, 2016

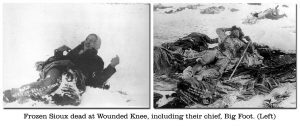

Wounded Knee was a Battle Not a Massacre–Sam Russell Interview

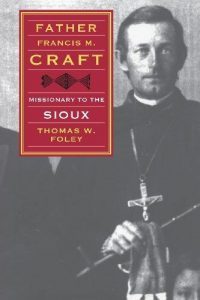

Col. Sam Russell (currently assigned to the U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute at Carlisle Barracks, PA), however, has proven previous accusations wrong with a book which compiles news stories (including eye-witness accounts) about the situation on the reservation.

The stories begin a few months prior to Dec. 29, 1890, when the battle occurred, to a few months following.

The news stories were written by Charles H. (Will) Cressey for The Omaha Bee.

Cressey was a witness to the battle, as were two other journalists, who

reported the same facts.

reported the same facts.The book is titled Sting of the Bee: A Day-By-Day Account of Wounded Knee And The Sioux Outbreak of 1890–1891 as Recorded in The Omaha Bee.

Father Francis Craft, a part-Mohawk Catholic priest, was also a witness, and Fr. Craft verified what Cressey and other reporters wrote.

Full disclosure, Sam has included a thank you to me in his introduction just because I read his manuscript and had a few editing suggestions.

He didn’t need to thank me. He did a fine job with this badly-needed corrective.

Sam, Omaha Bee reporter Will Cressey wrote the dispatches you quote in your book (and did an admirable job), and was present at the battle. He reported Wounded Knee as a battle in which the Sioux shot first.

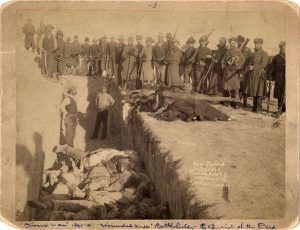

Burying Sioux bodies

Cressey wrote the Seventh Cavalry soldiers were disarming the Indians and surrounded them while others searched their tepees for weapons.

“About a dozen of the warrior had been searched when, like flash, all the rest of them jerked guns from under their blankets and began pouring bullets into the ranks of the soldiers who, a few minutes before, had moved up within almost gun length.

“Those Indians who had no guns rushed on the soldiers with tomahawk in one hand and scalping knife in the other…”

Burial party, Wounded Knee

Cressey wrote he was standing behind the Indians, close enough to touch them and the Indians “must have fired a hundred shots before the soldiers fired one.”

The Indians subsequently got away to the hills where the battle continued.

Unfortunately, when the Indians first fired, the bullets which failed to initially find a target passed the soldiers and hit the Sioux women who were standing behind the soldiers.

Robb: What did the other two reporters who witnessed the battle write about it?

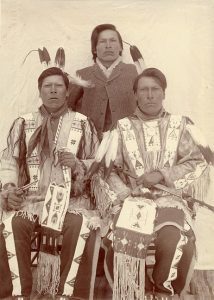

Brothers, (left to right) White Lance, Joseph Horn Cloud, and Dewey Beard, Wounded Knee warriors; Miniconjou Lakota

Russell: The three reporters that were present at Wounded Knee when hostilities broke out were Will Cressey of the Omaha Bee, Charles Allen of the Chadron Democrat, and William Kelley of the Nebraska State Journal, all were correspondents from Nebraska.

Not surprisingly, their sympathies were aligned with the settlers and residents of that state, and their three accounts were not all that different.

Kelley’s portfolio of articles was published in 1971, Pine Ridge 1890, and Allen wrote an autobiography that was published in 1997, From Fort Laramie to Wounded Knee, which included his article describing the battle.

There was a fourth reporter, Thomas Tibbles of the Omaha World Herald, who was at Wounded Knee the morning of the battle, but he departed early and wrote that he could hear the gunfire and cannons on his trip back to the Pine Ridge Agency.

Tibbles was married to an Omaha Indian, Bright Eyes, and the two of them offered the closest thing to a Native American account of the events surrounding the outbreak.

After the initial melee around the council circle concluded and the fight moved toward the ravines, Cressey, Kelley, and Allen retired to the shelter of Louis Mousseau’s trading post at the Wounded Knee Creek crossing adjacent to the cavalry camp and began writing their articles.

January 1891, Albumen Cabinet Card Photograph of a small log cabin behind the Post Office at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota – the location from which the first news reports about Wounded Knee were written. In this photo we see U.S. Marshall George Bartlett, writer / archeologist / anthropologist, Warren King Moorhead, an Indian Police sentry in full uniform and a third, unidentified white man believed to be Louis Mousseau who lived in the cabin and ran the Post Office / Store.

They had little time to write and still get their dispatches transported to a telegraph operator and submitted in time to make the evening editions. Unfortunately, that meant that none of the reporters witnessed that portion of the fight that included pursuing Indians up the ravines and into the hills.

Kelley, who won the honor by lottery of having his dispatch transmitted over the wires first, wrote, “All of a sudden they [the Indians] threw their hands to the ground and began firing rapidly at the troops, not twenty feet away. The troops were at a great disadvantage, fearing the shooting of their own comrades.”

Said to be survivors of Big Foot’s band

As Kelley recorded his perspective of the fight, the sounds of skirmishing rang out in the distance. He went on to write, “To say that it was a most daring feat, 120 Indians attacking 500 cavalry, expresses the situation but faintly. It could only have been insanity which prompted such a deed.”

Gen. Nelson Miles

Kelley concluded his article with, “Before the night I doubt if either a buck or squaw out of all Big Foot’s band will be left to tell the tale of this day’s treachery. The members of the Seventh Cavalry have once more shown themselves to be heroes in deeds of daring.”

Allen’s article was less opinionated than that of Cressey and Kelley. Describing the opening of the battle, Allen wrote, “They [the soldiers] had proceeded to disarm but some eight or ten of these [Indians], when the brave who had been inciting them jumped up and said something and fired at the soldier who was standing guard over the arms that had been secured. The first gun had no sooner been fired than it was followed by hundreds of others and the battle was on.”

Robb: Cressey reported many Sioux women attacked soldiers at the battle and the soldiers were forced to shoot them. Was Cressey correct?

Russell: There certainly were a number of firsthand accounts that detail Lakota woman and teenage boys arming themselves and fighting back against the soldiers.

Once the first shots rang out, the struggle was fight or flight, with examples of Indian men, women, and children doing both.

Some White accounts show that the soldiers were conflicted as to whether they should or could fire on women and children who had chosen to arm themselves and fight.

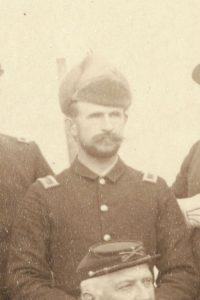

Second Lieutenant Thomas Q. Donaldson, Jr., C Troop, 7th Cavalry, present at Wounded Knee

Second Lieutenant Tommy Tompkins detailed one such incident in his testimony at General Miles’s investigation of Wounded Knee. “One of these mounted squaws was armed and fired on our line, and one of the men said then ‘There is a buck.’ And I said ‘No, it is a squaw, don’t shoot on her,’ and he said ‘Well, by God, Lieut., she is shooting at us.’ He did not fire at her.”

Robb: I was for many years a reporter and believe Cressey did an excellent job. Do you agree?

Russell: Given the period in which Cressey reported, and the newspaper for which he wrote, I believe he did an outstanding job.

Certainly his employer believed he did. He attempted to verify the myriad rumors that swirled around the agency, but, failing that verification, he still willing reported such rumors. He interviewed all comers, including Indians, particularly if they were considered hostile, and he at least presented their own words, even if it was through the lens of his own world view. That being said, Cressey’s bias is glaringly apparent.

To be fair, one can see such bias in news reporting today.

One certainly would expect to see a very different perspective from The New York Times versus the Wall Street Journal, or Fox News versus MSNBC.

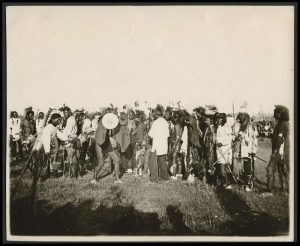

Ghost dance

Moreover, one would not expect to see an Iraqi or Syrian perspective regarding the conflict in Southwest Asia from an American news outlet.

Certainly, if there were a Lakota newspaper reporting from Pine Ridge, the accounts would be far different than those of Cressey and his peers. Still, I believe his reports are relevant, and an important historical record, as they provide the context in which Nebraskans viewed the outbreak of 1890-1891.

Robb: What happened to Father Craft, who also witnessed Wounded Knee?

Russell: Father Francis M. Craft was a very interesting witness, in that he was unfamiliar with the soldiers at Wounded Knee, albeit he was a strong advocate of the Army.

Father Craft

Many contemporary historians write off all of the testimony that 7th Cavalry and 1st Artillery officers provided with the guise that they were lying to cover up their dastardly deeds and protect their inept commander. I find this astounding, as the documentation for Wounded Knee is substantial, taken under oath, provided within days of the battle, but largely ignored by present historians.

Father Craft’s empathy lay entirely with the Lakota, to the point of directing that his body be buried with the Indians in the trench at Wounded Knee if he died of his wounds. He was part Indian; his great-grandfather was a Mohawk.

(Fr. Craft) vociferously blamed the Indian Bureau for all the ills the Lakota suffered, and early on recognized those ills–abject poverty, misery, and starvation–as the root cause of all the turbulence in Nov. and Dec. 1890.

Craft was at Wounded Knee to serve as an interpreter, as a friendly face known to the Lakota through his last ten years of missionary work, and to convince the warriors that they would be well cared for if only they peacefully surrendered their weapons.

He was positioned between the warriors and the cavalry at the opening volley. He was, according one of his later accounts, shot by soldiers and stabbed by a Brule.

Ghost dancers

Yet from his perspective on the battlefield, Fr. Craft faulted the Lakota for initiating the hostilities, for continuing to resist, for indiscriminately firing on their own village situated directly behind a troop of cavalry, and lauded the actions of the cavalry in trying to spare the lives of women and children, to the point of taking greater casualties themselves than if they had just wantonly and mercilessly shot down all of the Indians.

Fr. Craft, who was not afraid to rattle cages and was very vocal on what he believed to be the truth, provided a deposition that corroborated the soldiers’ accounts of Wounded Knee.

Moreover, he was recovering from his wounds in the Catholic Church, not the army field hospital, so was not privy to the post-battle banter and collaboration, so to speak, that occurred among the soldiers prior to giving testimony. He provided a similar account to Eli Ricker, but the judge seemed to not pay much heed to Fr. Craft’s version of events.

In addition to his sworn deposition, Fr. Craft gave a lengthy description of Wounded Knee in Feb. 1892 that is recorded in At Standing Rock and Wounded Knee, by Thomas Foley.

Foley has produced two good reads on Fr. Craft. A Quote from Foley in his closing paragraphs I think is on the mark, “Proponents who would enshrine Wounded Knee as the iconic epitome of Native American victimization diminish the heroic stand taken by Big Foot’s warriors.” (Foley, 318)

Dewey Beard’s account of his exploits at Wounded Knee are singularly impressive and unquestionably heroic… and account, in part, for why the 7th Cav. continued the battle up the ravines, to suppress such fierce resistance.

Fr. Craft recovered from his wounds, and continued his work among the Lakota. He was an energetic and visionary man, whose efforts were thwarted at every turn, even by his own Church. He was too vocal and created some very powerful and politically connected enemies along the way. Perhaps his efforts would have blossomed if he had allied himself with St. Katherine Drexel.

ghost dance

Ultimately, his twenty years of work among the Lakota bore little fruit, and he settled into a small parish in Pennsylvania until his death in 1920.

Robb: Cressey was clear the Indians were starving and plainly stated the shortage of rations caused the uprising on the reservation. Why did that situation exist and was it remedied?

Russell: There were a number of factors that caused the dire circumstances at the agencies. Drought had wreaked havoc on crops in the Midwest in 1889 and 1890. The reservation lands were not suitable for substantial farming, and even the favorable farming lands in Nebraska and South Dakota were greatly affected by the drought conditions.

Congress decided to wean the Lakota off government rations by cutting back on their annual allotment with the expectation that the Indians would become self-sustaining only if pushed in that direction.

The government purchased the designated allotment of beef on the hoof by the pound, but by the time the cattle were issued to the Indians, each steer had lost from 20% to 40% of its body mass, leaving the Lakota to deal with the shortage.

The Indian Bureau believed the reported numbers of Indians on the reservations were inflated, and conducted a census in 1890. This census reduced the population count, and thus reduced the allocation of rations. A measles epidemic swept through the reservations in the summer of 1890 with a high mortality rate, which likely was exasperated by the poor quality and scant quantity of the government rations.

While the Ghost Dance was not meant as a protest per say, the wide media coverage that it garnered brought the plight of the Lakota to the attention of Congress and the American people.

In that context, the Ghost Dance did have a positive impact on the Lakota, as the government took steps in late

Wounded knee dead

November and December 1890 to correct the poor rations.

The Indian Bureau’s efforts to remedy the situation—only after pressure from the Army and negative publicity in the media—were complicated when the “hostile” bands scattered over 3,000 head of cattle from the government herd at Pine Ridge. The steers that these bands were able to rustle sustained them in their stronghold in the Badlands, which inflamed the crisis and allowed it to continue through December and into January.

Robb: I assume the Army could have brought overwhelming force against the Sioux, but chose not to. Why not?

Russell: President Harrison’s instructions to the War Department and General Miles was to protect the agencies and resolve the crisis without bloodshed, if possible.

Said to be Ghost Dance shirt

General Brooke arrived at Pine Ridge at the end of November with a small contingent of forces expressly to protect the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies. As more forces arrived, like the 6th Cavalry Regiment from Arizona and New Mexico, 7th Cavalry Regiment from Kansas, and 1st Infantry Regiment from California, Brooke had the ability to assume the offensive, which he at times seemed almost desperate to do.

He had even issued orders and had all forces (over 27 troops of cavalry a battery of artillery and 100 Indian scouts) in readiness to move on the Indians in the Stronghold of the Badlands.

General Miles delayed the order to move when Sitting Bull was killed precipitating many of his Hunkpapa followers to scatter toward the Cheyenne River. Miles was concerned that, if attacked, the Indians would break out of the reservations and kill settlers. He focused most of his attention on the Sitting Bull remnants and Big Foot’s band precisely because they fled from their reservations. His correspondence with Brooke shows him restraining his subordinate from assuming the offensive.

The Hotchkiss Gun fired into the Sioux camp at Wounded Knee Creek

As long as the Indians were not attacking settlers, General Miles was content to wait them out and cajole their leaders to return to the agencies. He hoped winter would set in and force the Indians to return.

Ultimately, General Miles’s patience paid off, and his strategy to encircle the Indians that refused to return to the agencies and slowly constrict his lines succeeded in bringing all the tribes back to the Pine Ridge Agency.

Following Wounded Knee, General Miles eventually resolved the outbreak without further bloody engagements, excepting White Clay Creek the following day, due largely to a hard lesson learned, by both Lakota and soldier alike, at Wounded Knee: that to force the Indians to relinquish their arms would result in conflict.

General Miles came up with the solution that ultimately worked, only after he had seen the result of Wounded Knee, namely, to have the Indian chiefs collect the firearms and surrender them, and to look the other way when they knowingly relinquished only a token few weapons.

War dance, 1890

Unfortunately, for all concerned, that lesson had yet to be learned on December 29, 1890.

Robb: What happened to the two Sioux babies adopted by whites, one by an army officer?

Russell: One of the infants died within days of being found on the battleground. The other infant was indeed  adopted. The child was christened Zintkala Nuni, or Lost Bird. Her adopted mother, Clara Bewick Colby, was a 44-year-old suffragist and wife of Brig. Gen. Leonard W. Colby, commander of the Nebraska National Guard.

adopted. The child was christened Zintkala Nuni, or Lost Bird. Her adopted mother, Clara Bewick Colby, was a 44-year-old suffragist and wife of Brig. Gen. Leonard W. Colby, commander of the Nebraska National Guard.

The Colbys were residents of Beatrice, Neb., and Mrs. Colby became the unwitting, albeit caring and affectionate, mother of an adopted Lakota infant found on the battleground of Wounded Knee when her husband secured the child during the campaign and brought home his small curio for his wife to raise.

Unfortunately for Lost Bird, the Colbys separated and eventually divorced.

Mrs. Colby struggled with poverty and raised her adopted daughter as best she could within her limited means.

Lost Bird, as a teenager, miscarried a child—rumored to be Gen. Colby’s.

She went on to perform on Vaudeville and married her co-star. Lost Bird died of syphilis at the age of 29. She struggled during her short life with her identity and was rejected by both White and Indian cultures.

In 1991, her remains were repatriated from California to the Pine Ridge Reservation at the Wounded Knee Memorial where she was buried next to the mass grave of her kinsmen that fell at Wounded Knee a century earlier.

Lost Bird as an adult

Renee Flood wrote a well-researched book, Lost Bird of Wounded Knee, detailing the lives of the Colbys and Zintkala Nuni.

Robb: Was there more than one Sioux Ghost Dance belief? Some seemed to expect Jesus Christ to appear again and restore them to a pristine wilderness.

Russell: It took months, if not years, for the government to determine exactly what the Ghost Dance really was, how it started, and how it spread so rapidly and expansively among almost every tribe of the Midwest.

James Mooney’s anthropologic work for the Smithsonian was the first real in-depth study of this phenomenon, and really was the first historical look at the root causes of Wounded Knee from an Indian perspective. There were similar instances during the nineteenth century of Native tribes that adopted a messianic religion with similar overtones, e.g. resurrection of dead warriors and family members, return of buffalo and other wild game, removal of Whites, resistance to Americanization, etc.

Hope Springs Eternal, by Howard Terpning

I included one article that touched on this topic detailing Smohalla of the Wanapams. There were several other articles printed in the Omaha Bee during that winter that delved into cases of messianic religions among American Indians. It was certainly an aspect of the 1890 outbreak that interested the readers of the Bee.

Robb: What happened to the white man who claimed to be the Christ the Indians were waiting for?

Russell: Albert C. Hopkins was one of the stranger characters of that winter’s outbreak, and served almost as comic relief for what was otherwise a very serious, and ultimately, deadly series of events.

Officers serving at Pine Ridge reservation

Cressey described Hopkins as a “little daft,” which was an apt characterization. Hopkins was the founder and president of the Pansy Society of America. He lobbied Congress to recognize the pansy as the national flower, and even received support to redesign the U.S. Flag by arranging the white stars into the shape of a Pansy.

The design appeared in several papers, but ultimately the Congressman who introduced the bill also realized that Hopkins was a “little daft” and dropped support for the bill after being ridiculed in the press.

Hopkins died in 1904 in Canton, S.D. His death announcement was titled “’Pansy’ Hopkins Dead” and explained that, “His mind has not been right for some years.” Hopkins was a Union veteran and served in the 11th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment during the Civil War.

Sam Russell

ArmyAtWoundedKnee.com.

The post Wounded Knee was a Battle Not a Massacre–Sam Russell Interview appeared first on .

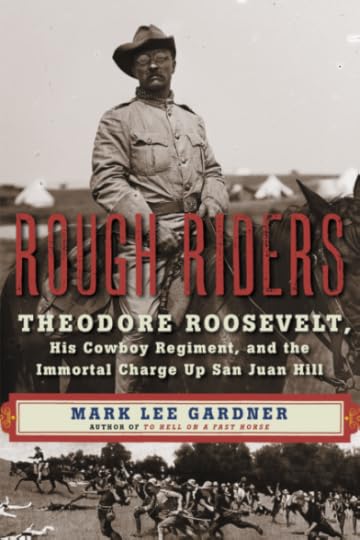

May 26, 2016

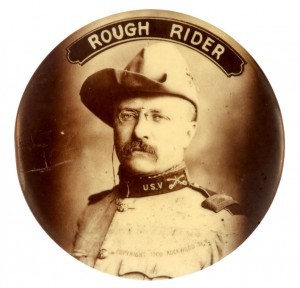

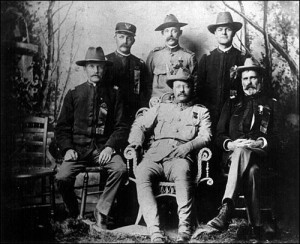

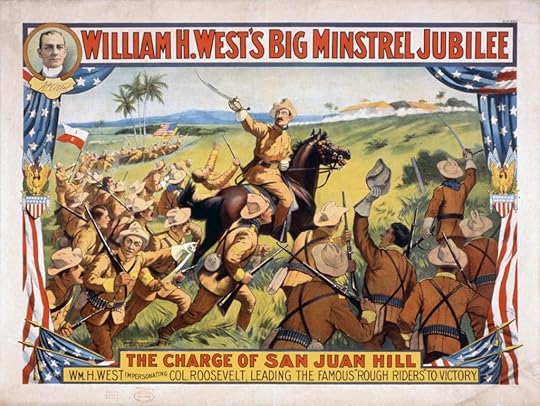

Teddy and his Rough Riders: Yes they did take San Juan Hill

Readers, Mark Lee Gardner has written a fascinating book about Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, names everyone knows, but no one knows much about.

Here’s the first interesting fact. Although some writers have claimed Teddy did not storm San Juan Hill, or Heights, in fact he and his men did that very thing.

With the declaration of war with Spain in April 1898, Theodore Roosevelt conceived the idea of raising a cavalry regiment recruited from Western businessmen, cowboys and outdoorsmen.

Roosevelt then inspired men to join the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, better known as the “Rough Riders.”

Roosevelt, a former New York National Guardsman, helped to organize the regiment and was appointed its lieutenant colonel.

Roosevelt, a former New York National Guardsman, helped to organize the regiment and was appointed its lieutenant colonel.

After training in Texas and Florida, the Rough Riders landed in Cuba, without their horses.

It was during the Battle of San Juan Hill, on July 1, 1898, that the Rough Riders, under Roosevelt, made their mark in American military history.

Teddy and some of his Rough Riders

Ordered to seize Kettle Hill in support of the main attack, the Rough Riders fought their way to the top despite heavy enemy fire.

After taking the hill, the Rough Riders continued their attack, seizing San Juan Heights, which overlooked the city of Santiago.

The American victory led to the Spanish surrender two weeks later.

Here’s the interview.

ROBB: The thing that first impressed me about the Rough Riders was their innocence, their naivety, their eagerness to fight in a war in which they could be killed. It seems the national nightmare, the Civil War, would have made them somewhat wary. Did you get the same impression while researching?

GARDNER: The young men who enlisted in the Rough Riders were definitely naïve. They had grown up with the  stories of the great Civil War (several were sons of Civil War veterans), and they longed for their own war and their own chance to win laurels on a battlefield. But as one Rough Rider wrote later, “To those who never soldiered in war times there is a halo that is inviting, but to those who have, there is no halo. It only comes with the years afterward when all things are softened as into a dream.”

stories of the great Civil War (several were sons of Civil War veterans), and they longed for their own war and their own chance to win laurels on a battlefield. But as one Rough Rider wrote later, “To those who never soldiered in war times there is a halo that is inviting, but to those who have, there is no halo. It only comes with the years afterward when all things are softened as into a dream.”

ROBB: I compare the Rough Riders to soldiers today and they do not seem to be the same kind of people. Roosevelt’s men were like men playing on a college football team while the soldiers today are seemingly aware of the horrors of war; they seem more sophisticated.

GARDNER: Television, beginning with the coverage of the Vietnam War, and, in more recent years, the Internet, have made us aware, and in the most graphic ways possible, of the true horrors of combat. So, yes, it’s not surprising that the soldiers of today are savvier about what they are getting into than the volunteers of 118 years ago. However, the fighting in Cuba was no sporting event, and the Rough Riders were as brave and steady as any soldiers on a battlefield before or after.

ROBB: I got the same impression about American culture in the Spanish-American War era; it was cohesive, innocent and shallow. For instance, nobody seemed to ask why Cuba was our war. That’s not how it is today.

ROBB: I got the same impression about American culture in the Spanish-American War era; it was cohesive, innocent and shallow. For instance, nobody seemed to ask why Cuba was our war. That’s not how it is today.

GARDNER: I didn’t delve deeply into the politics of the Spanish-American War in my book simply because there are plenty of volumes out there that treat that subject. My aim was to tell the story of this legendary volunteer regiment and its charismatic leader through the eyes of the participants.

There were many in the United States who questioned the war, but there were many more who supported it. The cause of Cuba Libre found much sympathy with Americans, who easily recalled the history of their own struggle for independence. It was the sinking of the USS Maine in February of 1898, however, that most shaped popular support for war against Spain.

ROBB: Who sank the Maine? Did the Spaniards sink the ship or ?????

GARDNER: The exact cause of the explosion of the Maine is still debated. I think most historians believe the powder magazine of the ship ignited accidentally.

However, the U.S. Navy assembled a board of inquiry to determine the cause, and it concluded that the Maine “was destroyed by the explosion of a submarine mine.” The vast majority of Americans accepted this report and pointed their fingers at Spain as the perpetrator.

ROBB: Did you find it ironic that the Rough Riders seemed to disdain the Cuban rebels, yet were in Cuba to ostensibly help them defeat the Spanish?

GARDNER: Most Rough Riders, including Roosevelt, were disappointed in what they saw of the Cuban insurrectos. Their clothing was in tatters, and their arms varied greatly in quality. It didn’t help that the Cubans failed to come through with the promised support in the subsequent fighting.

GARDNER: Most Rough Riders, including Roosevelt, were disappointed in what they saw of the Cuban insurrectos. Their clothing was in tatters, and their arms varied greatly in quality. It didn’t help that the Cubans failed to come through with the promised support in the subsequent fighting.

At least one Rough Rider, though, recognized what the Cubans had been up against, writing that “after all, they kept three hundred thousand Spaniards guessing for three years – no slight achievement.”

ROBB: The 10th cavalry (African-Americans) seemed to fight well, yet I never heard anything about their assistance in fighting the Spanish.

GARDNER: There were four regiments of Buffalo Soldiers, two of cavalry and two of infantry, in Cuba, and each of those regiments displayed real fighting spirit during the campaign.

The Spaniards called these black soldiers Yankees ahumados: smoked Yankees. They may not have gotten much press in the States, but they certainly impressed the Rough Riders who fought alongside them. “I tell you,” wrote one Rough Rider in a letter home, “the black boys set a pace that is damn hard to keep up with, for they fight like demons and never know when to stop.”

ROBB: I got the impression that Roosevelt and other officers just marched into fights and there was little planning or tactics, or strategy, involved. Is that true?

GARDNER: There was little strategic planning or direction. The commanding American general in Cuba, William Shafter, weighed more than three hundred pounds and suffered from gout.

(Shafter) was sick in his tent for the Battle of San Juan Heights of July 1, 1898, and communications between his headquarters and the battlefield took far too long, forcing subordinates to issue orders on their own initiative. As Roosevelt wrote later, the battle was “essentially a troop commanders’, indeed, almost a squad leaders’, fight.”

ROBB: Did having so many upper crust soldiers, Harvard men, etc. make a difference in what happened in Cuba?

GARDNER: The millionaires and Ivy Leaguers, for the most part, pulled their own weight in the regiment. The only real difference came from some of these men and their families donating money and supplies for the entire outfit.

GARDNER: The millionaires and Ivy Leaguers, for the most part, pulled their own weight in the regiment. The only real difference came from some of these men and their families donating money and supplies for the entire outfit.

Woodbury Kane, a wealthy New Yorker, had his sister send to Cuba six hundred tins of premium Golden Sceptre tobacco and several cases of canned peaches for the troopers. He instantly became, as one Rough Rider wrote, “the most popular man in camp.”

ROBB: Teddy Roosevelt was an unusual person, wasn’t he? It seems hard to compare him to anyone else in American history.

GARDNER: No American, living or dead, can compare to Theodore Roosevelt. He is endlessly fascinating. One Rough Rider commented to his mother that Roosevelt was “the most magnetic man I ever saw.” He inspired his men to no end, and they would literally follow him anywhere.

ROBB: Would Teddy have been elected president if he hadn’t organized and ridden up San Juan Hill with the Rough Riders?

GARDNER: Well, TR ran up San Juan Hill, his horse, Little Texas, having been left behind at a barbed wire fence.

But to answer your question, he may still have become president, but I don’t think it would have happened nearly as quickly. His heroics in Cuba (he was nominated for the Medal of Honor by all his commanding officers) put him in the national spotlight. This led directly to his being elected governor of New York in November, 1898, which was followed two years later with his spot on the Republican ticket in 1900 as vice president under McKinley.

ROBB: The Rough Riders also seemed different from other men you’ve written about. For instance, the men who fought in the Lincoln County War, and the James Gang and the lawmen who hunted them. What do you think about that?

GARDNER: There were actually a few wanted men, and even a couple of murderers, in the Rough Riders. But you’re right, most were not anything like the outlaws I have written about in the past. Billy the Kid and Jesse James were charismatic, and they seem to have been natural-born leaders, but Roosevelt was both charismatic and a genius to boot.

I think Jesse and Billy would have been drawn to TR, but not vice versa.

Frank James actually volunteered to serve as a personal bodyguard to Roosevelt after an assassination attempt on the former president during his Bull Moose campaign of 1912.

Gardner

The post Teddy and his Rough Riders: Yes they did take San Juan Hill appeared first on .

May 6, 2016

From Cochise to Geronimo, Paul Hutton narrates The Apache Wars

In The Apache Wars, Paul Hutton takes us from 1861, when a bungling Army lieutenant began the war by attempting to take Cochise captive, to exchange him for 12-year-old Felix Ward (later Mickey Free), until the late 1880’s, when Geronimo surrendered for the last time.

It’s a remarkable, enthralling narrative history, and Hutton is going to tell us about it, right now.

ROBB: Was the American military effort against Apaches greatly hampered by men who knew nothing about Apaches? For instance, Lt. Bascom’s mistaken efforts to capture Cochise?

HUTTON: The Bascom affair at Apache Pass is but one of many bungling acts by young army officers during the Indian wars. Two other examples are Lt. John Lawrence Grattan (probably responsible for the Grattan massacre during the first Sioux war) and Capt. William J. Fetterman (who led his men into an ambush during Red Cloud’s War on December 21, 1866) on the northern Plains.

George Bascom

The nature of the military at the time meant that few experienced officers remained in station for very long. Some of these officers—like Ewell, Randall, and Emmet Crawford—were excellent. The same was true for civilian Indian agents. As soon as they finally began to understand Apache culture they were removed by a new political administration.

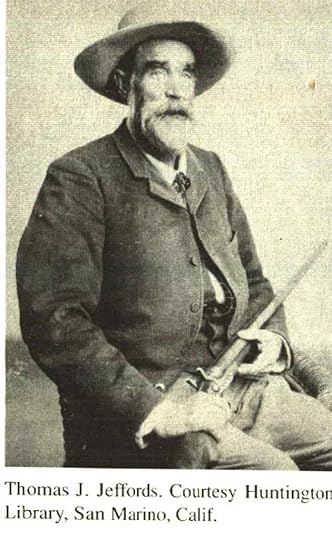

Of course many of the civilian agents were also corrupt and were bilking both the Apaches and the government. Men like Tom Jeffords, (friend to Cochise and peace negotiator) John Clum (Indian agent) and Kit Carson (army scout) were rigidly honest, but they were unfortunately but rare exceptions to the crooked dealings that so marked the Indian Bureau during the Gilded Age.

ROBB: Do you believe Apache leaders Mangas, Cochise and Victorio really appeared to their people after death?

Victorio

HUTTON: In my book I attempted to establish a tone of respect for cultural belief systems. I do not know with any certainty if Lozen, Geronimo, or the Dreamer had mystical power, but I certainly do know that many Apaches believed that they did. I respect those beliefs, and they help explain the actions of the Apaches.

ROBB: I’ve wondered if the American army could have won the Apache wars without Apache scouts. What do you think?

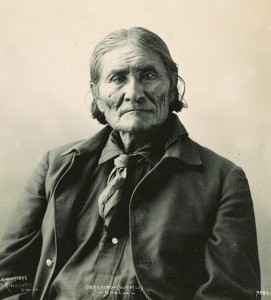

Geronimo

HUTTON: General George Crook’s adoption of the Apache scout program was essential to the American army’s success against the Apaches. This was made possible by the lack of any sense of Apache tribal unity.

The eventual betrayal of the Apache scouts by the U.S. government was a terrible wrong. It was, however, the 1886 final removal of the Chiricahua and Warm Springs people from Arizona to Florida that finally broke Geronimo’s ability to resist the “White Eyes.”

ROBB: Why did these Apaches agree to work against their own people? Did members of one band sometimes work against their own people (for instance, White Mountain against White Mountain) or just against other bands (White Mountain against Chiricahuas, for instance).

Mickey Free with his two wives

HUTTON: Certainly White Mountain Apaches scouted against Chiricahuas without the slightest compunction. There was no sense of tribal unity, and in fact there were many old scores to settle. When the government attempted to settle many separate Apache bands at San Carlos Reservation it caused great trouble—there were old feuds.

Apaches had a great sense of honor and carried grudges for a long time. These were Hatfield/McCoy type grudges.

Blood feuds were a great problem on the reservations. When members of the same band scouted against each other it became much more problematical.

This is where government scouts like Mickey Free, Tom Horn, and Al Sieber proved invaluable. Many army officers suspected the Apache scouts of assisting their band members and they were correct in this—although not always, for honor often trumped even family with the scouts.

General Phil Sheridan, however, never trusted the scouts and this finally led him to sack General Crook from his Arizona command.

Gen. George Crook

ROBB: I was shocked when I read the American government even sent the faithful Apache scouts to Florida. That’s right, isn’t it? How do you feel about that?

HUTTON: I was horrified by this act of unfathomable deceit. I never had much respect for Grover Cleveland, but this was really the nail in the coffin of my disdain for him. To meet with these people, shake their hands, smile at them and give them peace medals—and then secretly order them imprisoned. Incredible.

ROBB: I’ve read other accounts of Gen. Crook, but yours was more personal and realistic. I think of the time the Apaches and the Mexican families were fighting over the captive children (whether the foster parents would be able to keep them or if the kids would be returned to their own people), and the children were hysterical.

Crook left because he said he couldn’t stand to hear more. Was Crook a more sensitive person than he seemed?

HUTTON: Well, I’m pretty rough on Crook—certainly he was a somewhat compassionate man, but I think his reaction at the conference had more to do with his contempt for Gen. Otis Howard than any feelings he had for the Apache children.

ROBB: Why was Crook upset when Lt. Royal Whitman stopped the Tucson posse, which was determined to attack the Apaches?

Royal Whitman

HUTTON: Whitman’s action was a major breach of the delicate division between military and civilian authority. Unless you have declared martial law you can’t interfere with civilian movements. Whitman was right in what he did but it was certainly illegal.

Crook was just looking for anything to use against Whitman. All of this seems so odd when you consider Crook’s later defense of the Indians—but it was reflective of his professional position at that time.

ROBB: You mentioned that the valiant Howard Cushing, (captain, third cavalry, killed in 1871 while fighting Apaches), was attempting to make up for something he had done in the past. What did he do?

Howard Cushing

HUTTON: Cushing had disgraced his storied family name by a drunken prank at the end of the Civil War. He was a man in search of redemption. He made a reputation for valor in Arizona but he is pretty much forgotten today. He reminded me of Custer.

ROBB: Gen. Crook not only demanded Apache heads, he put them up on sticks!! Really!?!

HUTTON: Crook wanted to make a point and he certainly did. Years later, Geronimo commented on how easy it was to lose one’s head in Apache country if you did not follow the rules.

ROBB: What did you mean when you wrote about Vincent Colyer’s “paternalistic racism?” (Colyer was a Quaker who attempted to assist the Apaches).

HUTTON: Colyer, and most of his fellow “humanitarians” were only interested in converting the Indians into “white Christian farmers,” with an emphasis on Christian. General Otis Howard was much the same. This was a despicable form of cultural genocide. At least the soldiers just wanted to fight the Apaches man to man. The so-called “friends of the Indians” were far worse than the soldiers.

Gen. Otis Howard

ROBB: The Apache wars remind me of our American misadventures in the Middle East, bumbling into what we don’t really understand, constantly adopting new policies, which often work against other policies, changing commanders in the middle of the war, feeding them and bombing them, feeding them and bombing them. What do you think about that?

HUTTON: Well, the comparison to our current misadventure is a compelling one. In both cases we are dealing with tribal societies which we seem to have a rather detached understanding of. In both cases we seem to want to introduce among them our cultural and political values. Guess what? It does not work. We are always surprised by this.

ROBB: You write about a lot of frontier characters most Americans know nothing about. It’s the style now to attack and denigrate American historical figures, but you haven’t done that. You show Capt. John Bourke, third cavalry, (one of my personal favorites), Lt. Howard Cushing (third cavalry), Eugene Carr, Kit Carson, Thomas Jeffords, Scout Al Seiber, Gen. Otis Howard, and many others, as outstanding men.

Army Scout Al Seiber

HUTTON: I do not see much value in sitting in judgement on Americans from a different century with entirely different values. It is not as if we have done such a great job with the modern world that we are allowed to judge those who came before. These frontiersmen did the best they could in a very difficult environment. I found them both heroic and tragic, but I have no right to judge them. I leave that to my readers.

ROBB: Were you aware you were writing against the fashion? Among these men, which do you admire most? Which is the most interesting?

HUTTON: Well I admire Tom Jeffords and Cochise immensely. They both fought for peace in a world consumed by war and racial hatred. They were my childhood heroes and it was wonderful to discover how close the reality of their lives were to my childhood fantasies.

ROBB: Before you did your research, were you aware Apache women had so much influence over the men? I am thinking of what John Bourke had to say about that. Have you found that to be true?

ROBB: Before you did your research, were you aware Apache women had so much influence over the men? I am thinking of what John Bourke had to say about that. Have you found that to be true?

HUTTON: Well, humans are humans in any place or time. Lozen, of course, (the highly respected sister of Cochise, said to have psychic powers) was an exception to the normal role of a woman in Apache society.

John Bourke, adjutant to Gen. Crook and author of several memoirs and anthropological works. He was a friend to the Apache.

But Apache women held enormous influence over all aspects of life. Once, while Geronimo was fleeing from pursuing troops, the band halted to observe a young girl’s puberty ceremony. I think that says everything about the importance of women. They were the givers of life. The Apache people were nothing without them.

ROBB: Democracy seemed to have gotten in the way of Indian policy. Officials seemed to always do what earned them the most points with the voters rather than the right thing. Is that correct?

HUTTON: The bottom line was that settlers voted and Indians did not. It was that simple.

ROBB: It occurred to me while reading Apache Wars , that the Apaches got what they deserved from the Americans considering what they did to the Mexicans for so many years. What do you think about that?

The Apache Kid, first an Army scout, then later a sought-after renegade.

HUTTON: The Apaches certainly made life a living Hell on the northern frontier of New Spain and then the Mexican Republic. Santa Anna agreed to the Gadsden Purchase because the Mexican northern frontier was indefensible.

The Apaches actually assisted American expansion. The unrelenting Apache war on the Mexicans grew out of necessity (they lived by raiding) but then out of a quest for revenge.

The Mexican slavery system and the hiring of professional scalphunters (some of whom were Americans) was outrageous. In many ways the Mexicans brought the Apache revenge raids on themselves.

Kit Carson

HUTTON continued: It is interesting that much of the conflict between the Americans and the Apaches was over Apache raids into Mexico. The Apaches refused to halt these raids and so the American government moved in to stop them.

It was the American determination to protect the Mexicans that contributed to the continued warfare. That is often forgotten in the historical record of those dark days.

Paul Hutton

The post From Cochise to Geronimo, Paul Hutton narrates The Apache Wars appeared first on .

March 22, 2016

Tom Rizzo and His Stories: You Can’t Stop With One

Hello readers: I began to read The Lawbreakers, by Tom Rizzo, a few days ago and couldn’t stop, so I finished and bought The Law Keepers.

Real-life stories about the West’s lawmen and their opponents are like popcorn, once you start you don’t want to stop.

So, of course, my next move was to interview author Tom Rizzo and see what else I can find out.

Julia Robb: Why did you write these

books?

books?Tom Rizzo: I wanted to provide an entertaining snapshot of at the good, the bad, and the ugly of the American West—characters and events that shaped our rich history.

Volume 1, The Unexpected , deals with some of the more bizarre stories of the frontier—ghosts, con men, a headless horseman, a phantom train. Stories, in many instances, that couldn’t be explained.

Volume 2, The Law Keepers , deals with those whose job was to keep the peace—to the extent it was possible on such expansive territories—unique individuals who wore badges, but who often walked both sides of law and order. Courageous and daring lawmen who were passionate about their responsibility to make their corner of the frontier a safe place to live and rear a family.

Volume 3, The LawBreakers , was the most fun. I confess that when I was a kid, I enjoyed playing the outlaw in our neighborhood street plays of Cowboys and Indians. But fun aside, many lawbreakers were mean-spirited, vicious, quick to kill, and committed to taking what wasn’t theirs.

Robb: Did you learn anything personally by researching the lawmen and the outlaws?

Tom Rizzo: I’m struck by the courage of the lawmen I encountered. These guys put their lives on the line to carry out a responsibility to keep the peace. Some went to extraordinary lengths to do so and many simply had no quit in them.

For example, a lawman by the name of Orlando “Rube” Robbins tracked an escaped prisoner across the Dakota Territory and into the Oregon Territory, finally captured him, and returned him to prison—a journey of over twelve hundred miles.

Harvey Whitehill

Grant County Sheriff Harvey Whitehill of Silver City, New Mexico, happened to be the first lawman every to arrest Billy the Kid—twice.

He let the Kid off with a warning the first time, but put him behind bars the second. He did escape, the first prisoner ever to do so from Whitehall’s jail.