Julia Robb's Blog, page 2

April 10, 2017

Our Dirty Little Secret

We cannot reproduce the past, which is made up of endless detail, social habits, ways of thought and culture we don’t even know about anymore.

And if we did, it would be impossible to reproduce all of it.

For instance, in the nineteenth century, men often used their initials rather than their given name: R.B. Clark, E.W. Robb.

For instance, how often riverboats blew up, killing everybody on board (often burning them to death); how often ships went down at sea, and even on the Great Lakes, and that was referred to as being “cast away.”

Train schedules were like today’s plane schedules. You rode “the cars,” for instance, from New York to Chicago, then changed trains to travel to Omaha.

If you were traveling west after 1869–when the last spike on the intercontinental railroad was driven–you could take the cars all the way to San Francisco, looking out the window and watching the endless buffalo herds.

The past IS a foreign country and once it’s past, nobody can return.

The above wonderful painting is “Enigmatic Long House” by Curt Walters.

April 9, 2017

Historical Novelist Despairs Because She Can’t Stop Researching

I had to rename one of my characters (in fact, had called two different characters by the same last name).

I searched for a Civil War slang term meaning “exciting,” (never found it) and had to make sure I knew how many stripes an (Indian Wars cavalry) major wore on his shoulder.

Ok, NOW I’m going to ignore everything and just continue to write my fourth novel.

They are all about men and women who lived in Texas, during the Indian Wars.

This very fine landscape is titled “Cliffs of the Green River,” by Thomas Moran (1837-1926).

Moran was an English immigrant who died in Santa Barbara, California.

April 7, 2017

What did the first people think?

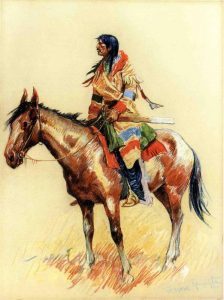

These canvases are considered romantic illustrations, thus cheap.

Personally, I’ve learned a lot from Terpning.

Tribal peoples had no science, therefore they didn’t know why it rained, or what caused thunder.

Thunder sounded like the voice of God.

Thus, Indian peoples became mystics.

Mystics are people whose understanding originates in the spirit, not the mind.

Take a look at this, “Spirit of the Rainmaker,” and you will understand why the tribal peoples believed like they did.

(By the way, Terpning’s paintings have sold for more than half a million dollars, so I doubt he cares what anyone thinks of his work).

April 6, 2017

Here’s a new thing friends

Hi, from now on, I’m posting every day, and most days my Facebook post and this blog will be identical.

Hi, from now on, I’m posting every day, and most days my Facebook post and this blog will be identical.Read ’em and weep.

Hey friends:

I wrote this morning and part of the afternoon on my new novel and then decided to take a bath.

The water was so nice and warm I went to sleep, and began dreaming scenes for my book.

When I woke up, I had just seen one 10th Cavalry trooper ride over to another one and grab his arm, shaking his head.

No, don’t do it.

Do what? Don’t do what??

And I couldn’t remember the scenes before that.

Curses! Foiled Again!

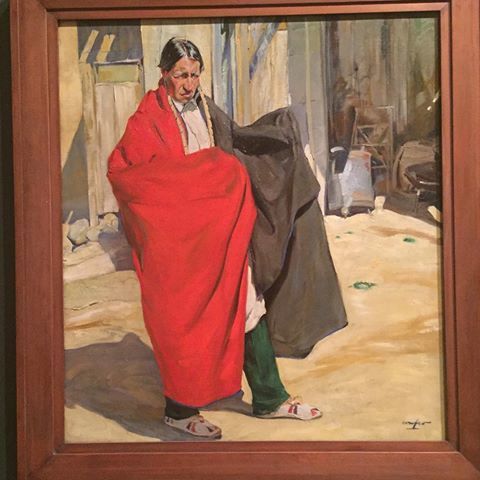

I love this painting by Walter Ufer.

March 14, 2017

SCALP MOUNTAIN

This is a portion of my novel Scalp Mountain. I have also written Saint of the Burning Heart, Del Norte and The Captive Boy. All of them can be found at Amazon.com. All except Del Norte can be purchased in print.

This is a portion of my novel Scalp Mountain. I have also written Saint of the Burning Heart, Del Norte and The Captive Boy. All of them can be found at Amazon.com. All except Del Norte can be purchased in print.You can also find me at Facebook (either Author: Julia Robb or my personal Facebook page), and Pinterest.

Chapter One

Colum was sitting on a rock, shoving beans and tortillas into his mouth, when the vaquero told him strangers were in Janos, the nearest village, stalking house to house, searching for a redheaded American.

Men on horseback chased cattle across a plain, calves bawled, and wood smoke curled up from branding fires, sweeping north on the wind.

The vaquero stared at spring grass pushing up through rocky ground.

“What do these men look like?”

“Jefe,” boss, “they are Tejano, like you.”

Snatching his hat from his sweaty forehead, Colum wiped his skin with his grimy cotton shirt sleeve. His red hair slid past his ears and clung to his neck. He used one freckled hand to scrap dirt off the other.

I could kill them before they know they’re dead, he thought, shoot them from behind the same way they plan to drill me. Or I could hire a vaquero to side me, face them from the front and avoid the rurales coming for me, after.

Or I could run again.

At the last thought, hollowness like a sun-stretched desert filled him, an unwillingness to take one more step, ride one more mile with the banshees howling behind. There’s no end to it, on the jump, my bones crumbling from the long trail, sleeping with one eye open, living on beans until I gag at the scent of them.

My life is no use to me.

“I thank you for telling me,” Colum said. He fished two pesos from his pocket, holding them out for the other man.

“No, Jefe, I don’t want nuthing,” the vaquero said, not moving. He had holes in his boots, where leather would have protected his toes.

Colum waited.

“Señor, I have heard of a place.”

“Yes?”

“This place is in Tejas,” Texas, “a valley, a..un paraíso.”

“A paradise?”

“Yes. Mens don’t go to this place. You mares would get fat, like me,” the vaquero said. He patted his stomach and tried to grin. “Water runs from mountains. Puro.”

“You’ve seen it, have you?”

“My compadre told me. He was there.”

Gray hair fell over the vaquero’s bloodshot eyes. Tiny blue moles dotted his face.

“Where is this paradise?”

“Near El Paso Del Norte, two days.”

“What’s your name?”

“Panfilo.”

“Panfilo, leaving here, it’s four days to the Rio Grande.”

“Pues,” well, “this is a good horse and you got three mares.”

I have good stock. Colum’s Appaloosa stallion, white with dark gray, spotted hindquarters and dark mane, stood a few feet away, tearing grass from the ground and gulping it down, his head swinging from side to side, greedy for the best parts.

“It’s a hide out? Not that I need one, mind you.”

“This country is sierra, nobody go there.”

“Why are you telling me about this place, I took your starving mother some groceries? You wouldn’t be making some extra pesos by luring me away from this rancho, by any chance?”

“I want to go with you.”

Oh. Let’s see, this man has been with me four weeks. He came in late, after dark, hat in hand, begging for a job. Aye, he has the running look, he needs a way to cross the river, and thinks he can trick me into riding north with him, watching his back. He has spun this place from fairy dust.

Still, Colum could see the valley in his mind, and he had never wanted anything more in his life; pastures filled with springing Appaloosa foals, waking in the morning knowing he was home, in a house he built with his own hands, believing the coming day would be like any other, like yesterday, like next week. He could feel desire on his tongue and it tasted like cabrito, goat meat, cooked over mesquite, melting in his mouth, resinous with smoke and fat.

If the manny here is lying, perhaps I can find another place for myself, he thought, imagining Texas with a rapture he usually reserved for horses and women.

“Tell the peons to load a burro for us, and I will pay the haciendado for the goods. We need corn for the stock, spare horseshoes and nails, a hammer, tortillas, side meat, canned stuff, rope, cartridges for my Winchester and for that Spencer you’re carrying, and anything else you can pack.”

“Yes, jefe,” boss.

“I’m guessing you can shoot, but can you cook?” he asked the squat vaquero, throwing himself on the stallion

“Yes, jefe.”

Riding north, they crossed the Sierra Madre, clinging to skinny trails snaking down mountainsides, leading the mares on long ropes and skidding on melted snow until they found firm ground on the plains; short, clean scrub, with two shadows moving steadily behind them.

Antelope or wild horses maybe, he thought, squinting, but the shadows did not stop to graze; they stayed on his trail like coon hounds, as if they could smell him.

Is it Panfilo, or is it me they’re after? When he was sure hunters followed, he spotted another moving smudge, a third rider hanging further back.

Ash-colored sky replaced sunlight and Colum hid Panfilo, the horses and the burro in an arroyo, then swept their tracks with a creosote bush.

Silence hummed, air cooled. A yellow moon rose, perfectly round, its color deep as a gourd, shiny against the darkening blue sky, and the riders did not appear.

Gray replaced darkness, and the world appeared around them, but they saw no movement. Panfilo held the muzzled horses, and the burro burdened with goods. Colum clung to the top of a juniper tree, his nose clogged with the smell of its sharp needles, his hands sticky with resin, his eyes sweeping back and forth like unsettled green water.

Two men passed. It took them all morning, from the first moment Colum saw them, until they disappeared over the horizon. He couldn’t see them clearly because they rode in wide circles, their heads down, searching for tracks.

Hell gate goblins, thinking we’re green and can catch us easy.

He never saw the third rider. Perhaps I dreamed it.

Colum looked back at Panfilo, at the vaquero’s chocolate skin gleaming in the light, and the Mexican raised his stumpy right hand, throwing it palm up, toward the sky. What do you want to do?

Wait, he mouthed.

The hunters returned, trotting in a widening gyre, then headed east.

Somebody knows ground, Colum thought, like vultures gliding over a corpse.

Darkness brought cold but no fire. The men huddled in their jackets, nibbling on crumbling cornmeal tamales.

“You have woman troubles?” Panfilo asked.

“No, I’m looking for a good wife, do you know a lady would do me the favor?”

“All womens are putas,” whores. “None of them is good.”

“Are you bitter, then?”

“What’s bitter?”

“Have you had bad experiences?”

“I don’t have none of those.”

“The searching men, is it you they’re looking for?”

“Nobody wants me.”

Silence gathered and Colum was relieved he could not see the other man’s face; if Panfilo was a liar, this was not a good time to find out.

Dawn, and they could see El Paso del Norte and the Rio Grande winding past the town. They rode in with rifles slung across their saddles, scanning rooftops, peering around corners.

Colum’s boots rubbed against swollen feet, his buttocks and thighs ached from days in the saddle, a warm breeze played with his black slouched hat–worn since the South threw up its arms in battered surrender.

Panfilo clapped his hand on his cheap straw sombrero.

Nothing stirred on the dirt street but the clop of hooves and a rooster’s crow.

Adobe houses crowded narrow streets shaded by cottonwood trees, leafed out with the palest of green. A squat bell tower announced the day’s first Mass while a woman with braids falling to her waist sat on her heels by a fire, patting tortilla dough in her hand, ready for customers.

Dragging her grill toward the fire, the metal clanged against the woman’s bowl and Colum’s hands twitched on his reins, spooking the stallion into a fruit cart, which still dozed under canvas.

The mares then whirled and slammed the cart again, hindquarters and legs rising and falling against the hapless wood.

Trembling like a wounded animal, the cart crumpled in a pile of kindling, the fruit rolling over the street; yellow bananas, orange mangos, green limes.

As the stallion scrambled around the cart, kicking and bucking, a bullet sped past Colum’s hat. Only then did he see the man sitting up in his saddle, on the corner, in full sight, aiming at him again. Before he could control the stallion and defend himself, Panfilo shot the ambusher high in the sternum, blasting the man backward and to the ground.

A second shooter appeared at the other corner, to Colum’s right, but Colum did not see him until it was too late. The long black barrel pointed at him, shining in the sun.

I’m dead. He waited, only to see the shooter’s head erupt in a tower of blood, as if an interior volcano lifted the man’s skull and swept him to the dirt street.

Standing by the gunman he killed, Panfilo’s eyes widened with shock.

Colum and Panfilo looked up and down the empty street. Who killed the second gunman?

The man Panfilo killed had red and white paint dotting his face and his three braids lay like black corncobs tossed on the dirt. He wore a Union-blue cavalry shirt. His eyes glared at the sky, a green fly buzzed around his face, then lit and crawled inside his open mouth.

Of course they found us, this man’s a Tonkawa. The entire tribe scouts for the U.S. Army.

The second dead man was sunburned above his beard and he smelled like unwashed long johns and leaking chamber pots. This man camped in saloons, Colum thought, helping himself to the free hard-boiled eggs and pickles, puking under the tables and throwing his money away at the faro game.

Faces peered from cracked doors, from windows. A few men slid outdoors, gathering around the bodies like vultures around a dead dog, hushed, their eyes down.

Spurring their horses, Colum and Panfilo galloped northeast, to the edge of the city–parallel to rock-covered mountains spreading morning shadows on the plain beneath–past tamarisk trees leaning over thatched huts built with wood poles, and goats penned with pricklypear cactus.

Julia Robb published the ebook edition of Scalp Mountain in 2012. Copyright by Julia Robb. All rights reserved. Digitally printed by Amazon.com. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information write juliarobbmar@aol.com.

February 2, 2017

Billy the Kid, Almost Home

Because Billy was home; the only home he had ever had.

Before Lincoln and Fort Sumner, the Kid’s mother, Catherine McCarty, moved the family from New York to Indianapolis, to Wichita and Denver, to Santa Fe and Silver City, New Mexico.

Consumption killed Catherine in Silver City, when her son was fifteen or sixteen.

Fatherless, the Kid wandered around Arizona until he killed a man in self-defense.

Then at sixteen, Billy rode to New Mexico and never left.

New Mexico casts a spell: Cedar and sage, billows of white clouds reclining on blue mountains, adobe, the Rio Peñasco and the Rio Bonito.

Spanish rolling off the tongue; amigo, corazón, compadre.

The Kid spoke Spanish and the Hispanos loved him, especially the girls.

Billito, they said at fandangos, batting their eyes above their fans.

An attempt to touch up an early tintype distorted Billy the Kid’s official face, so we see him as grotesque.

His sweetheart, Paulita Maxwell, however, told author Walter Noble Burns the Kid had “A certain sort of boyish good looks,” and in “every placeta in the Pecos some little señorita was proud to be known as his querida.”

Burns interviewed many people who knew the Kid and recorded those interviews in his 1926 book, The Saga of Billy the Kid.

Burns also interviewed the Kid’s friend, Sallie Chisum, who vowed when Billy came to see her he looked like he had “just stepped out of a bandbox.

“In broad-brimmed white hat, dark coat and vest, gray trousers wore over his boots, a gray flannel shirt and black four-in-hand tie, and sometimes–would you believe it?–a flower in his lapel..”

Sallie said, when the Kid “was an enemy, he was an enemy, but when he was a friend, he was a friend. He was brimming over with light-hearted gaiety and good humor…”

The Kid was always a gentleman around her, Sallie said, and once, when she showed him trees planted to commemorate love between three brothers, “I remember how touched Billy was..he looked so wistful and woebegone I felt called on to cheer him up.”

Although many deny it, both Sallie and Paulita said the Kid and Pat Garrett were once close friends.

Hard to lose a friend. Hard to be hunted by a friend. Hard to be killed by a friend.

Here’s proof of his feelings about New Mexico.

When Gov. Lew Wallace suggested the Kid could take care of his problems if he just left the Territory, the Kid said, “No, this is my country and I’m staying here.”

He stayed and Garrett killed him.

Burns said the Kid was faster than Garrett, but Garrett was able to kill him in that dark room, at Pete Maxwell’s house at Fort Sumner, because “It was Billy’s time to die.”

The Kid saw it coming at the last second, in a flash of light which turned out to be gunfire.

I’ve seen what purports to be his grave in Fort Sumner.

Maybe he’s there, maybe he’s not.

It’s said that the next world looks like places we love best.

In that case, the Kid is finally, really and truly, home.

The painting is “Almost Home,” by Bob Boze Bell, http://www.bobbozebell.net

The post Billy the Kid, Almost Home appeared first on Julia Robb, Author.

February 1, 2017

Texas Guitar Man

The only living buildings were churches, and convenience stores on the highway.

Then I saw a man sitting on a bench, playing a guitar. He was the only human on the street except me.

He was decorated with badges and sunglasses, a bristled face, and a hat so old the felt was worn clear through.

He could play.

Maybe it was “Desperado,” maybe “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain.” Maybe it was something he made up; half cowboy, half blues.

I don’t know who he was, and I’ve forgotten the name of the town: Someplace between Post and Sonora, Pecos and Paint Rock.

Texas. It grabs your heart.

https://www.facebook.com/Julia.RobbFa...

https://www.amazon.com/Julia-Robb/e/B...

The post Texas Guitar Man appeared first on Julia Robb, Author.

January 31, 2017

The Texas Guitar Man

I was in West Texas, driving through long stretches of nothing, then little towns where stores on the lone main street were empty and closed, windows still advertising sales ending five years ago.

I was in West Texas, driving through long stretches of nothing, then little towns where stores on the lone main street were empty and closed, windows still advertising sales ending five years ago.The only living buildings were churches and the convenience stores out on the highway.

Then I saw a man sitting on a bench, playing a guitar. He was the only human on the street except me.

He was decorated with badges and sunglasses and a hat so old the felt was worn clear through.

But he could play.

Maybe it was “Desperado,” maybe “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain.” Maybe it was something he made up; half cowboy, half blues.

I don’t know who he was, and I’ve forgotten the name of the town: Someplace between Post and Sonora, Pecos and Paint Rock.

Texas. It grabs your heart.

The post The Texas Guitar Man appeared first on Julia Robb, Author.

December 10, 2016

Rocky Mountain Christmas: John Monnett and his Yuletide Stories

Monnett filled the book with everything from the “Bill of Fare” John Fremont’s men “enjoyed” for Christmas dinner in 1848, to what prairie pioneers gave each other when pickings were slim.

Monnett, who lives in Colorado, has also written, among others: Where a Hundred Soldiers Were Killed, Massacre At Cheyenne Hole, Tell Them We Are Going Home, The Battle Of Beecher Island, Eyewitness to the Fetterman Fight and The Indian War Of 1867-1869.

Monnett, who lives in Colorado, has also written, among others: Where a Hundred Soldiers Were Killed, Massacre At Cheyenne Hole, Tell Them We Are Going Home, The Battle Of Beecher Island, Eyewitness to the Fetterman Fight and The Indian War Of 1867-1869.My first question is about Zebulon Pike, the famous explorer for whom Pike’s Peak was named. Pike attempted to climb the mountain in 1806.

ROBB TO READERS, Pike was a soldier in the U.S. Army and he explored when ordered to do so; not that he was reluctant. On his first expedition Pike and his 24 men went all the way from St. Louis to the Rockies in an attempt to “ascertain the direction, extent, and navigation of the Arkansas and Red Rivers.”

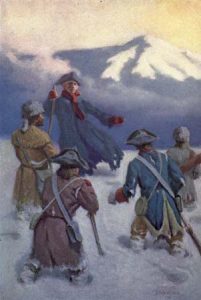

ROBB TO READERS, Pike was a soldier in the U.S. Army and he explored when ordered to do so; not that he was reluctant. On his first expedition Pike and his 24 men went all the way from St. Louis to the Rockies in an attempt to “ascertain the direction, extent, and navigation of the Arkansas and Red Rivers.”But exploring must have seemed a little challenging on Christmas Day, 1806. Pike and his men were snowed in, in the Rockies, without winter clothes or blankets.

They had already cut up their blankets to make socks and other garments.

Pike wrote he was forced to lay uncovered on the snow, “one side burning whilst the other was pierced with the cold wind.”

They had already cut up their blankets to make socks and other garments.

Pike wrote he was forced to lay uncovered on the snow, “one side burning whilst the other was pierced with the cold wind.”

Luckily, a hunting party sent out on Christmas Eve did kill eight buffalo, so the men ate.

ROBB: Zebulon Pike and his expedition really had a hard Christmas in 1806. Can you tell us more about that?

MONNETT: They were snowbound in the Sangre de Cristo mountains above modern Salida, Colorado and near the San Luis Valley, one of the coldest areas of the state with temperatures reaching 40 below zero.

MONNETT: They were snowbound in the Sangre de Cristo mountains above modern Salida, Colorado and near the San Luis Valley, one of the coldest areas of the state with temperatures reaching 40 below zero. ROBB: John Fremont and his expedition were also snowed in while traveling through Southern Colorado, but in 1848, 42 years after Pike. Was the Christmas menu for “Camp Desolation” based on reality?

ROBB TO READERS, Thomas Breckenridge, a member of the expedition, wrote explorers were having the following:

Soup: Mule tail. Meats: Mule steak, fried mule, mule chops, stewed mule, damned mule, short ribs of mule with apple sauce (without the apple sauce), etc.

Soup: Mule tail. Meats: Mule steak, fried mule, mule chops, stewed mule, damned mule, short ribs of mule with apple sauce (without the apple sauce), etc.ROBB: Was this what they were really eating?

MONNETT: Fremont’s Christmas feast is probably part truth and part sarcasm. Played out Mules often fell victim to feasts if game was not plentiful. I think the “menu” reflected the malaise and boredom, and longing to be home of the men on the expedition.

ROBB: Can you tell us about the “Mountain Man’s Christmas” of 1813 and the part Flathead Indians played? (Flatheads were really the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d’Oreilles tribes.)

ROBB: Can you tell us about the “Mountain Man’s Christmas” of 1813 and the part Flathead Indians played? (Flatheads were really the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d’Oreilles tribes.)To achieve flat foreheads, the Indians wrapped their baby’s heads in a bandage and used a board, hinged to the cradle-board, to press down on the baby’s foreheads.

MONNETT: In 1813, white fur trappers were the minority group in the mountain West. As such they married into Indian tribes like the Flatheads, often to forge a trading alliance with the band, learned and spoke the native tongues, and shared customs with the Indians.

Economically, the two races depended on each other and mutually benefitted from trade.

Economically, the two races depended on each other and mutually benefitted from trade.Customs were also exchanged. The Indians referred to the white man’s feasting at Christmas as “the big eating” and the trappers and Indians eventually shared this tradition.

ROBB TO READERS: During one shared Christmas feast, the trappers roasted a heifer, but both the whites and the Indians declared the meat inedible. They were used to the leaner buffalo.

ROBB TO READERS: During one shared Christmas feast, the trappers roasted a heifer, but both the whites and the Indians declared the meat inedible. They were used to the leaner buffalo. Also, when the Flatheads appeared that Christmas they held Blackfoot captives, who they agreed to release in return for ammunition to use against Blackfoot raiders.

ROBB: Who was Sir St. George Gore and why did he travel to the Rocky Mountains?

MONNETT: Sir St. George Gore was a British nobleman and adventurer. Colorado’s Gore Mountain Range is named for him.

There were more than a few of these guys in the early 19th century. They were quite flamboyant. The Brits were fascinated with the American West to hunt, explore, and write about their adventures. Too often they exploited the game resources of the West.

There were more than a few of these guys in the early 19th century. They were quite flamboyant. The Brits were fascinated with the American West to hunt, explore, and write about their adventures. Too often they exploited the game resources of the West.Later they monopolized land for private hunting preserves. When game became exhausted they thankfully sold their “claims” and went home.

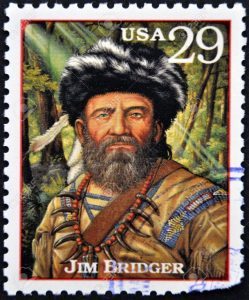

ROBB: Gore employed Jim Bridger as a guide. Can you tell us more about him?

MONNETT: Jim Bridger was perhaps the most famous Mountain Man in western history. He first came West in 1820 with the famous Ashley Expedition that opened the fur regions of the northern Rockies, thru the Dakotas, and into Wyoming and Montana.

MONNETT: Jim Bridger was perhaps the most famous Mountain Man in western history. He first came West in 1820 with the famous Ashley Expedition that opened the fur regions of the northern Rockies, thru the Dakotas, and into Wyoming and Montana. He later scouted for the U. S. Army in 1865-1866 on the Bozeman Trail.

He knew the Sioux and Cheyenne intimately.

As a teenager in 1820 with Ashley, Bridger learned the trade of the mountain man. He was depicted as the young “James” in the movie The Revenant. He is credited with the discovery of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

As a teenager in 1820 with Ashley, Bridger learned the trade of the mountain man. He was depicted as the young “James” in the movie The Revenant. He is credited with the discovery of the Great Salt Lake in Utah.ROBB to Readers: For the record, Bridger married three Indian women and died in his 70’s, on his Missouri farm.

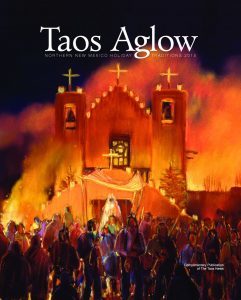

ROBB: Can you tell us how they celebrated Christmas in Taos in the 1840’s?

MONNETT: Southwestern traditions at Christmas are my favorite. They are a mixture of Anglo, Hispano, and Pueblo assimilations. The Santa Fe traders first brought paper bags to New Mexico that were used for the simple candle-lit luminaries we know today.

MONNETT: Southwestern traditions at Christmas are my favorite. They are a mixture of Anglo, Hispano, and Pueblo assimilations. The Santa Fe traders first brought paper bags to New Mexico that were used for the simple candle-lit luminaries we know today.

Passion plays, especially Las Posadas, where the community goes door to door on Christmas Eve looking for the Christ child, are a tradition still performed today.

Dances at the Pueblos mixed with Latin Mass are an age old tradition since Spanish Colonial times.

Dances at the Pueblos mixed with Latin Mass are an age old tradition since Spanish Colonial times.Some remote Hispano communities around Santa Fe and Taos still look for the Christmas spirits that dwell in the mountains and visit homes on Christmas Eve. They are both male and female beings, “Abuelos and Abuelas,” grandfathers and grandmothers.

ROBB: What did the pioneering Sutton family (who lived in a sod house, on the Dakota prairie) give each other for Christmas, and why?

ROBB: What did the pioneering Sutton family (who lived in a sod house, on the Dakota prairie) give each other for Christmas, and why? MONNETT: During hard times, pictures of desirable items were cut from the pages of the catalogs and given as gifts. Even when life was often hard, pioneer families kept the spirit of Christmas alive with their innovative traditions.

Prior to close railroad connections, when permanent houses had yet to replace sod homes, Christmas was a simple affair with isolated families.

On the treeless prairie west of the 100th meridian sage bushes were often utilized as Christmas trees (Tumbleweeds did not arrive from Russia until the 1890s when railroads would deliver real Christmas trees to rural towns).

On the treeless prairie west of the 100th meridian sage bushes were often utilized as Christmas trees (Tumbleweeds did not arrive from Russia until the 1890s when railroads would deliver real Christmas trees to rural towns).Ornaments were made from local materials and colored paper wrappers that had been saved all year. Straw dolls for girls, carved wooden toys for boys were often all that was available.

http://billingsgazette.com/news/featu...

The post Rocky Mountain Christmas: John Monnett and his Yuletide Stories appeared first on .

November 17, 2016

Trump, Wyatt Earp and Thomas Jefferson

Ben Frankin reading the Declaration of Independence, just written by Thomas Jefferson, standing.

I didn’t vote for Donald Trump, and yet I understand why many people did:

They were punishing our intellectual elites.

Since the election, pundits have said this very thing. That media, politicians and the highest paid professionals don’t understand or respect Middle America .

Maybe true, but one important aspect has been forgotten–how many elite “historians” and writers undermine America’s heroes, like Wyatt Earp, and founding fathers like Thomas Jefferson.

I don’t believe this has been a conscious assault, but it has been, nonetheless, an assault, and it has taken a huge toll on American confidence and optimism.

Wyatt Earp

No wonder so many Americans felt the need to strike back.

Their heroes, the bedrock of their country, have been devalued, so their country has been devalued, and therefore they have been devalued.

(Unfortunately, in my opinion, voters struck back the wrong way).

But let me give you two examples.

University of Virginia rotunda, designed by Thomas Jefferson.

This past week, students and professors at the University of Virginia criticized their president for quoting Thomas Jefferson, who founded their school.

Protestors said Thomas Jefferson shouldn’t be used as a “moral compass” because he was a slave owner.

This is the usual. For years, academics and writers have insisted Thomas Jefferson was repugnant and a hypocrite, not only because he was a slave owner but because he had (maybe? probably? nobody knows for sure) a slave mistress (Sally Hemings).

Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson~ from An American Scandal (2000)

First, if Thomas Jefferson and Miss Hemings did have a relationship (and DNA proves someone in Mr. Jefferson’s family fathered her children), we don’t know the nature of their relationship and it is deluded to believe we do.

Could they have loved each other?

We don’t know.

Montecello, Jefferson’s home, designed by Jefferson

Does possibly having a slave mistress mean Thomas Jefferson should be denounced; that brilliant architect, statesman, president, inventor, writer of The Declaration of Independence, that rebel who helped ignite and lead our revolution?

Here’s what I say.

It’s easy to feel morally superior in hindsight, and that must make a lot of folks feel good.

Never mind that our founding fathers knew slavery was a moral evil, but one they couldn’t erase without destroying the new country. By 1776, the colonies were already invested in slavery.

So would these pompous highbrows prefer Jefferson and his ilk not have created the United States because it could not be created perfectly?

If you’re reading this blog and feel like attacking me: Don’t.

I’m not defending slavery, which was a great evil.

I’m attacking an odious moral superiority which has a pernicious effect on The United States.

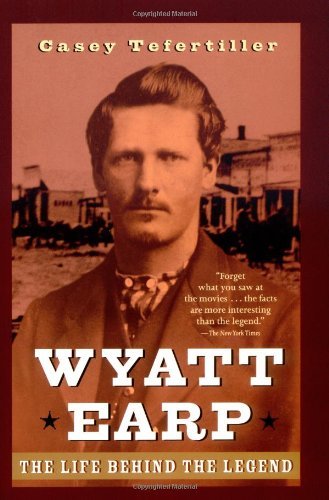

Second example, Wyatt Earp.

Earp has admirers and detractors, but his detractors usually make the same charges.

They say Earp was not a hero because he and various partners owned saloons and Earp was a professional gambler while working in law enforcement.

Earp was a scoundrel because his brother James owned brothels.

Earp was a bad man because one or more of the men killed at the gunfight might have been unarmed.

And gasp, because Earp and his brothers were ambitious and wanted to make money.

I’m not kidding. These are the things writers and “historians” say about Earp. He wanted to make money and become successful in his society.

The Gunfight at the OK Corral, by Thom Ross

But on Oct. 26, 1881, the day the Earps faced the “cowboys,” nobody condemned lawmen who owned saloons or gambled, James Earp was not a lawman, I don’t know if all three men killed at the OK Corral (actually, in the vicinity of) were armed and nobody knows to this day.

Down Front Street, by Thom Ross

And it’s the height of hypocrisy to claim Wyatt Earp was not a hero because he was ambitious. That’s the human occupation. It’s the American way and has been from the beginning.

And now it’s bad?

The Earps certainly believed they were facing fully-armed opponents.

Wyatt Earp, Morgan Earp, Virgil Earp and Doc Holliday were brave men who faced outlaws who had repeatedly threatened to kill them, including that very morning.

Doc Holliday

So there you go. Let’s destroy one of our founders and an inspiring archetype because superiority feels so good.

Criticizing ones country for genuine and recent sins is a must in a democracy.

But undermining its heroes and the people who created the Republic in the first place, by judging them by our light rather than theirs, has been highly destructive.

If they were no good, is America any good?

What is our bedrock?

Destroy a society’s belief in itself and you destroy that society.

The post Trump, Wyatt Earp and Thomas Jefferson appeared first on .