Julia Robb's Blog, page 9

March 23, 2014

Lucia Robson Writes Indians and Strong Women

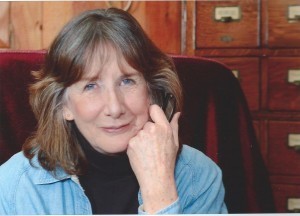

Lucia St. Clair Robson

Hi Lucia St. Clair Robson, thanks so much for talking to me. I understand you’re on deadline for a new book. You must be one of the most versatile historical novelists in the United States. You’ve written four books about America’s tribal people, (RIDE THE WIND, WALK IN MY SOUL, GHOST WARRIOR and LIGHT A DISTANT FIRE), one about a woman seeking revenge in feudal Japan (TOKAIDO ROAD), one about an indentured servant in 17th Century Maryland (MARY’S LAND), one about the American revolution (SHADOW PATRIOTS), one about famous frontier character Sarah Bowman (FEARLESS) and one about the Mexican revolution (LAST TRAIN FROM CUERNAVACA). Your novels’ strong central female characters are the only thing I find in common, except an obvious empathy with history and tribal peoples.

Q. How did your interest in tribal people develop?

Lucia (far left) with Quanah Parker’s descendants. The family portrait was taken at the Cowboy Symposium in Lubbock, TX, a few years ago. (The necklace Lucia is wearing was made for her by one of Quanah’s granddaughters who has since passed away).

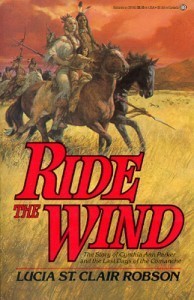

ROBSON – When neighborhood kids played cowboys and Indians I always wanted to be an Indian. I made many bows and arrows from the hibiscus hedge in the front yard. Never thought I’d write about Indians though. As a librarian in Maryland I happened to read a short article on Cynthia Ann and Quanah Parker (Cynthia Ann’s son) in the Time/Life Great Chiefs volume. When I met a DelRey editor at a science fiction convention in Baltimore I mentioned the story to him. He encouraged me write Ride the Wind, which I thought was a ridiculous idea. I didn’t know anything about Comanches, or anything about writing a novel either. But the deeper I got into their history the more fascinated I became.

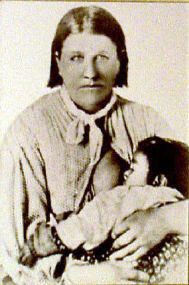

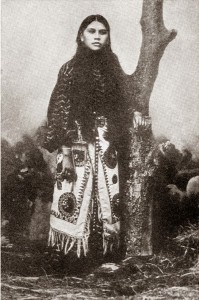

Cynthia Ann with her daughter Prairie Flower

(Cynthia Ann was captured by Comanches in 1836, at Fort Parker, her family’s outpost in Central Texas. She married a Comanche man and had children, one of them Quanah Parker. She was recaptured by white men but was unhappy and died a few years later).

Walk in My Soul, about Cherokee Tiana Rogers, was a chapter cut from WIND. For the third novel (Light a Distant Fire) I wanted to write about Osceola of the Seminoles, a hero of mine since I was a kid. Author Jeanne Williams suggested I write about Lozen of the Chiricahua Apaches (Ghost Warrior) every time I saw her at Western Writers’ conferences.

When I did some reading about Lozen I could see why Jeanne suggested her. Her life was more compelling and adventurous that anything I could make up.

Q. Since you wrote Ride the Wind (published 1982) other authors have written (non-fiction) accounts of Cynthia Ann’s life. Have you read them, can you judge the accuracy of these accounts?

A. I haven’t read the newer accounts of Cynthia Ann and Quanah’s story. I know new information has come to light, (but) I can’t go back and change Ride the Wind now anyway. Plus, there’s always so much to read in order to write the next book. Mary’s Land has the most bibliography cards — 335 sources.

A. I haven’t read the newer accounts of Cynthia Ann and Quanah’s story. I know new information has come to light, (but) I can’t go back and change Ride the Wind now anyway. Plus, there’s always so much to read in order to write the next book. Mary’s Land has the most bibliography cards — 335 sources.

(Readers: The Western Writers of America gave Lucia the Spur Award for Ride the Wind and it also made the New York Times Best Seller List and was included in the 100 best westerns of the 20th century).

Quanah Parker

Q. You began Ride the Wind with Cynthia Ann’s capture, which included some horrific killing and a suggested rape. Was it difficult to make the Comanche sympathetic when you were so truthful about Comanche warfare?

A. I figured if I didn’t show the raid on Ft. Parker as it was described by the fort’s residents, I’d be doing them an injustice.

But yes, I did worry a lot that the Comanches would be angry at me. It’s a tribute to Quanah’s descendents that they’ve been very kind and receptive. I’m welcomed at their gatherings, and Ron Parker opens his emails to me with “Nami,” sister. It was a tremendous honor to be included in the family portrait taken at the Cowboy Symposium in Lubbock, TX, a few years ago.

Q. How did you become interested in feudal Japan? Talk about a change of pace.

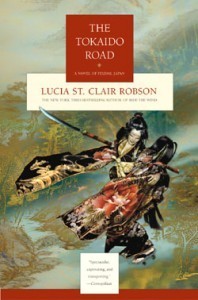

A. Toshiro Mifune. I became a fan of Samurai movies when I was in college in the early ’60′s. During Peace Corps training in 1964 I went to a theater on a rare afternoon off to see Mifune-san in Chushingura, the famous story of the revenge of the 47 ronin. The movie was 3 1/2 hours long and I sat through it twice. It changed my life. When I had a chance to live in Japan in 1970 I took it, and got to visit the temple where the 47′s ashes are enshrined.

Q. Your Amazon author’s page said you began your adult life as a Maryland librarian. Did you always want to write?

A. I never aspired to write one book, much less nine. After getting a BA in Sociology, my adult life started with a stint in the Peace Corps. Then I taught third grade in Brooklyn, NY., worked in libraries (without an MLS) in Florida and South Carolina. I held those last two jobs for part of my six years as an Army wife. In 1974 I earned my MLS and went to work as a librarian in the public library system in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Quit my day job at the end of 1981 to write full time. Ride the Wind wouldn’t hit book stores for seven more months, but I had an advance for Walk in My Soul, based on the proposal and outline. I figured I could live for most of a year on the first part of the advance.

A. I never aspired to write one book, much less nine. After getting a BA in Sociology, my adult life started with a stint in the Peace Corps. Then I taught third grade in Brooklyn, NY., worked in libraries (without an MLS) in Florida and South Carolina. I held those last two jobs for part of my six years as an Army wife. In 1974 I earned my MLS and went to work as a librarian in the public library system in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Quit my day job at the end of 1981 to write full time. Ride the Wind wouldn’t hit book stores for seven more months, but I had an advance for Walk in My Soul, based on the proposal and outline. I figured I could live for most of a year on the first part of the advance.

Q. You’ve said you’re afraid you will be regarded as a romance writer. Why would you be apprehensive about that?

A. All my books have romance in them. It makes the world go ’round, after all. But in my experience it seems many people assume any female novelist is a romance writer.  The problem in my case is that someone who buys one of my books expecting something romantic will be hit early on with mayhem. My advice to beginning writers is, “Start with a massacre. You don’t need snappy dialogue and plot development there.” (Kidding, of course, but that is how I approached WIND and FIRE and GHOST WARRIOR. TOKAIDO started with a murder in a brothel.

The problem in my case is that someone who buys one of my books expecting something romantic will be hit early on with mayhem. My advice to beginning writers is, “Start with a massacre. You don’t need snappy dialogue and plot development there.” (Kidding, of course, but that is how I approached WIND and FIRE and GHOST WARRIOR. TOKAIDO started with a murder in a brothel.

In the other books the mayhem comes a little later on. Another reason people assume (Robson’s novels) are romances is that many of the covers feature a beautiful young woman who, by the way, is never the image I had in mind. But as my guy Brian used to say, “Lots of little children don’t have covers to complain about.”

One reason for the beautiful women on the covers is when I started writing, the current statistic was that women bought 70% of fiction. I don’t know if that’s true now or even if it was then, but that was the perception. The covers were designed to appeal to women.

Q. How do you research your books and how long does it usually take?

A. As mentioned before, I do a lot of library research for each story, and I always travel to the places about which I’m writing. Each book takes from two to five years because writing doesn’t come easily for me and the research is time-consuming. The information is organized by subjects, with cross-referencing, like the old library card catalogs. I even found an antique oak, 24-drawer card catalog that holds 4×6 cards. It’s a prized possession.

Each book has its own drawers full of index cards… tens of thousands of them I would imagine. Never counted them though.

Q. The publishing world has dramatically changed since Ride the Wind was published? Writers are now self-publishing and we have ebooks. Do you have any thoughts on this?

A. We all know that technology has changed publishing as it has music and art and so many other aspects of our society. My take on it is to use it to advantage. If no one wants the contemporary novel I’m working on now I’ll put it out myself.

I’ve also gotten the rights to some of my titles and my guy Brian Daley’s too and have put them out in hard copy and as e-books. As for e-books, they’re another source of revenue for writers. I don’t have an e-reader and never will, but as a librarian and a writer, I’m happy to see people reading in whatever format they choose

Q. Which book is your favorite?

A. That’s like asking which child is one’s favorite. But I will confess that Tokaido was the most fun to write and certainly the most fun to research. I was able to return to Japan 18 years after I had lived there and travel all over the country.

Q. What are you working on now?

A. I’m working on a contemporary novel that I started 16 years ago and put away because, honestly, it was terrible. But it’s had time to marinate, and I think it’s much better now. My mother has been after me to finish it for all these years. Hint: It’s about an incubus, with a bit of a mystery story entwined. I hope it’s at least a little funny, but no one’s read this draft yet to tell me if it is or not.

Comanche girl

To reach Lucia, got to her website at http://www.luciastclairrobson.com, or buy her books at amazon.com, http://www.amazon.com/Lucia-St.-Clair...

The post Lucia Robson Writes Indians and Strong Women appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

March 9, 2014

Johnny Boggs: Western Writer Talks About His Life and Career

Hi Johnny Boggs, thanks so much for this interview.

Hi Johnny Boggs, thanks so much for this interview.

You’ve written more than forty books and won the prestigious Spur award six times. You’ve done well writing about the American West.

Q. On your website, you said you’re interested in the West because you were exposed to westerns as a child. Could you be more specific?

A. I grew up during the tail end of the western TV craze, so my introduction was from Gunsmoke, The Virginian, shows like that, and I watched as many movies as I could find on TV. I can’t tell you how many times I saw Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on the CBS Saturday night movie. I also remember reading, rereading and re-rereading comic books on Daniel Boone and Billy the Kid. And when I was older you’d find me browsing the Western selection on the shelves at Ray’s Novel Shop or in the used-book stores. That’s where I discovered Will Henry, A.B. Guthrie Jr., Dorothy M. Johnson and Jack Schaefer.

A. I grew up during the tail end of the western TV craze, so my introduction was from Gunsmoke, The Virginian, shows like that, and I watched as many movies as I could find on TV. I can’t tell you how many times I saw Gunfight at the O.K. Corral on the CBS Saturday night movie. I also remember reading, rereading and re-rereading comic books on Daniel Boone and Billy the Kid. And when I was older you’d find me browsing the Western selection on the shelves at Ray’s Novel Shop or in the used-book stores. That’s where I discovered Will Henry, A.B. Guthrie Jr., Dorothy M. Johnson and Jack Schaefer.

Q. Personally, I write (mostly) about the 19th century West because I don’t enjoy today’s physical and cultural restrictions. Do you feel at all the same way, or do other aspects attract you?

A. I’ve written what I guess you’d call contemporary Southern short fiction – dare I say autobiographical? – and some of my “westerns” are pretty much historicals set in the South. But since they’re set in the Backcountry in the 1700s, the publishers can call them frontier novels. I don’t know, but I’d guess that what really attracted me to the West when I was growing up was the fact it seemed a long, long way from the swamps and tobacco fields of South Carolina. And maybe I still feel that way.

A. I’ve written what I guess you’d call contemporary Southern short fiction – dare I say autobiographical? – and some of my “westerns” are pretty much historicals set in the South. But since they’re set in the Backcountry in the 1700s, the publishers can call them frontier novels. I don’t know, but I’d guess that what really attracted me to the West when I was growing up was the fact it seemed a long, long way from the swamps and tobacco fields of South Carolina. And maybe I still feel that way.

But what really draws me into writing a novel or short story are the characters and the land. I just find a subject that starts taking root and it becomes an obsession so that I have to write about it.

But, trust me, I know plenty of publishers and editors who put physical and cultural restrictions on what they want to see in westerns. And I don’t like rules – except in baseball – and I don’t like fences and I don’t like boundaries. I like to write about what I want to write about.

But, trust me, I know plenty of publishers and editors who put physical and cultural restrictions on what they want to see in westerns. And I don’t like rules – except in baseball – and I don’t like fences and I don’t like boundaries. I like to write about what I want to write about.

Q. While researching, have you found anything that surprised you, or would surprise others?

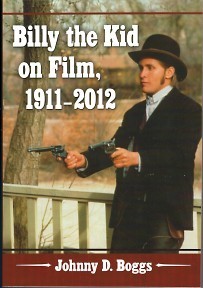

A. I love the research, and I’m always finding something new. Probably the most recent thing came when I was researching a nonfiction book, Billy the Kid on Film, 1911-2012. The first actor to play Billy the Kid in a movie was an actress. When I started, most sources credited an actor named Tefft Johnson, but it turned out to be Edith Storey.

A. I love the research, and I’m always finding something new. Probably the most recent thing came when I was researching a nonfiction book, Billy the Kid on Film, 1911-2012. The first actor to play Billy the Kid in a movie was an actress. When I started, most sources credited an actor named Tefft Johnson, but it turned out to be Edith Storey.

Q. Do you believe people who lived in the 19th century West really had a different set of values and modes of behavior than we do, or that people have always been basically the same?

As an example, 19th century western men seemed to revere women and be protective of them (that’s what we read). But is it really true?

A. I think people are people. We haven’t really changed that much. You can make a good argument that the bushwhackers who rode with Quantrill are no different than the members of urban gangs today.

A. I think people are people. We haven’t really changed that much. You can make a good argument that the bushwhackers who rode with Quantrill are no different than the members of urban gangs today.

One of the fascinating aspects of reading history is seeing how often it’s repeated. Certainly, you can find people out West who put women on a pedestal – same as you can likely find today, although that’s probably becoming more rare. But you can also find men who had absolutely no respect for women, same as today.

Going back to the previous question, I remember reading Britton Davis’s The Truth about Geronimo and discovering how he despised the words squaw and buck. Proof there were liberals even in 1880s Arizona.

Q. Is there a 19th century western man (or woman) you highly respect, (or is even your hero or heroine) and why?

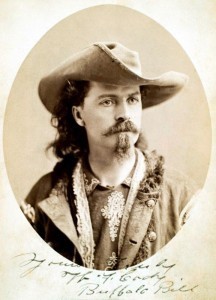

A. I’ve often said that I would have liked to have met Bill Cody – perhaps because he would have bought me a drink or two. I like John Muir, Mark Twain, Quanah Parker, Mary Goodnight, Chief Joseph, Lozen, Sam Houston, Sequoyah, Texas Jack Omohundro, Satank, Annie Oakley, and, to an extent, Cole Younger.

A. I’ve often said that I would have liked to have met Bill Cody – perhaps because he would have bought me a drink or two. I like John Muir, Mark Twain, Quanah Parker, Mary Goodnight, Chief Joseph, Lozen, Sam Houston, Sequoyah, Texas Jack Omohundro, Satank, Annie Oakley, and, to an extent, Cole Younger.

The ones I highly respect are the women and men, red, white, Hispanic, Chinese, Irish, Norwegian, Southern, Northern, etc., who nobody remembers, who never wrote a memoir, never took part in a gunfight, probably never even got their names in a paper – and maybe not even on a tombstone. Just did their jobs and brought up their families, lived and died in relative obscurity. But we wouldn’t be here without them.

The ones I highly respect are the women and men, red, white, Hispanic, Chinese, Irish, Norwegian, Southern, Northern, etc., who nobody remembers, who never wrote a memoir, never took part in a gunfight, probably never even got their names in a paper – and maybe not even on a tombstone. Just did their jobs and brought up their families, lived and died in relative obscurity. But we wouldn’t be here without them.

Q. You are a very successful author who is published the traditional way, by a publisher, printed as well as digital. What do you think of the Indie revolution?

A. Books are books. Remember, it wasn’t that long ago that stories were all told orally. And carrying my kindle onto an airplane is a whole lot easier than packing six or seven books for a trip. And I still believe that no matter how you’re published, great writing will eventually be recognized.

Q. Why have you gotten interested in particular stories? For instance, in Northfield you wrote about the “Great Northfield Raid.” Why did you choose to write about the disaster that destroyed the James gang when it tried to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota, on September 7, 1876?

Q. Why have you gotten interested in particular stories? For instance, in Northfield you wrote about the “Great Northfield Raid.” Why did you choose to write about the disaster that destroyed the James gang when it tried to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota, on September 7, 1876?

A. Northfield came out of the movies and a lot of bad fiction and nonfiction. I’d read and seen so much hogwash about what happened in Northfield, I wanted to tell the story as accurately as possible. That’s the ‘truth is stranger than fiction’ idea.

Stories come to me in different ways. A magazine article I’d read led me to do East of the Border, about the theatrical careers of Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro.

I once heard a speech by an Indian lawyer named Killstraight – which led to my Killstraight series. I just loved the name and remembered John Jakes telling me about the ‘power of the letter K.’

I wanted to experiment with Greasy Grass and see if I could turn the actual (Little Big Horn) battlefield into the character.

I wanted to experiment with Greasy Grass and see if I could turn the actual (Little Big Horn) battlefield into the character.

The Hart Brand began with a horse wreck I had on a trail ride. Some come from passages in books, from places I’ve visited, people I’ve met, newspaper articles, something I simply overheard someone say, movies I’ve seen, or even a photograph or painting.

Q. What advice would you give to other western authors, particularly those beginning their careers?

A. That’s easy. Write. Read. Write. Read. Write. Read. Edit. Edit. Edit. Edit. Rewrite. Rewrite. Rewrite. Then write and read some more.

Q. You’ve written more than 40 books, short stories, and are a photographer. How did you do that? Do you have certain writing habits?

A. It’s a job. My commute is just shorter than most people’s. I have no inheritance, no retirement, and my wife’s a realtor. I write for a living. It’s to the office in the morning and working eight to ten hours a day, five or six days a week.

A. It’s a job. My commute is just shorter than most people’s. I have no inheritance, no retirement, and my wife’s a realtor. I write for a living. It’s to the office in the morning and working eight to ten hours a day, five or six days a week.

My advice is Don’t Quit Your Day Job. That’s the advice I was given many years ago. I just didn’t listen to it. This is an incredibly hard way to make a living, but there’s nothing I’d rather be doing.

Q. What are you working on?

A. Let’s see. I have two magazine assignments I have to finish next week, and I just got another assignment that I’m trying to set up the interviews for, plus I’m trying to set up some interviews for a travel assignment in April. I’m proofing a short story for an anthology that I have to email to the editor tonight. A magazine editing job just landed on my computer, so I have to get that done in the next 10 days. There’s a novel I’m working on, and I’ll probably get proofs for another novel in the next week or so.

Baseball’s about to start and I’m on the board of directors for one of the Little Leagues and will be managing a team and umpiring.

Baseball’s about to start and I’m on the board of directors for one of the Little Leagues and will be managing a team and umpiring.

About four literary functions are coming up. I have to take my son to snowboarding lessons tomorrow, and one of the dogs needs a bath.

Q. Are the number of western readers shrinking, expanding, or has the number held steady through the years (and why)?

A. Well, I’ve always been loose with what I call a western. Mystery writers Craig Johnson, C.J. Box, Tony – and now Anne – Hillerman, I call what they’re writing westerns. I also call The Grapes of Wrath a western.

A. Well, I’ve always been loose with what I call a western. Mystery writers Craig Johnson, C.J. Box, Tony – and now Anne – Hillerman, I call what they’re writing westerns. I also call The Grapes of Wrath a western.

Jeff Guinn, a best-selling nonfiction writer, signed a three-book deal for Western novels with a major New York house, Philipp Meyer’s The Son earned phenomenal reviews, and we’re seeing more and more western nonfiction rise on the New York Times best-seller lists.

The problem is most people think of westerns as Louis L’Amour and Zane Grey, and those readers are usually older males. Most people buying books these days are women.

And for several years now I’ve tried to write at least one young adult novel to get our children – especially boys – interested in reading about their history and heritage.

I think westerns have always been that ugly stepchild when it comes to genre fiction, but it’s still there despite countless epitaphs and death songs over the past several decades. People still like those stories.

I think westerns have always been that ugly stepchild when it comes to genre fiction, but it’s still there despite countless epitaphs and death songs over the past several decades. People still like those stories.

And I’m certainly busier now than I’ve ever been. That’s a good sign, I think, for anyone who writes or reads westerns.

The post Johnny Boggs: Western Writer Talks About His Life and Career appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

August 8, 2012

All my reviews are posted here and my blogs are posted at...

All my reviews are posted here and my blogs are posted at Venturegalleries.com

August 7 Interview by Richard Weatherly, at Welcome To My Place.Hi Julia,Welcome to My Place. I’m eager to hear what you have to say about your writing in general and

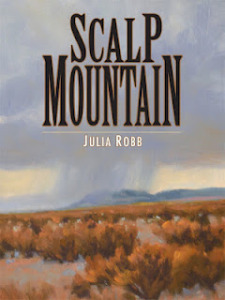

about your novel, Scalp Mountain.

Would you like to share a synopsis of your novel?

about your novel, Scalp Mountain.

Would you like to share a synopsis of your novel?

It’s 1876 and Colum McNeal’s immigrant Irish father has sent gunmen to kill him. Colum finds a refuge in a hidden Texas valley and begins ranching, but struggles to stay there: José Ortero, a Jacarilla Apache, seeks revenge for the son Colum unwittingly killed.At the same time, an old acquaintance, Mason Lohman, obsessively stalks Colum through the border country. Colum has inspired the unthinkable in Lohman. In a time and place where a man’s sexuality must stand unchallenged, Colum has ignited Lohman’s desire.Other characters include Texas Ranger William Henry, who takes Colum’s part against his father while wrestling with his own demons. Comanches murdered Henry’s family and Henry regrets the revenge he took; and Clementine Weaver, who defies frontier prejudice by adopting an Indian baby. Clementine must also choose between Colum and her husband. One thing I noticed about Scalp Mountain was the depth of your character development. Tell us how you chose your main character and describe how you like to present your characters to the readers. My novels all start the same way; I see images in my mind, but I don’t understand them. I saw Colum standing on a hill in the Davis Mountains, in Texas. When I asked myself what this man was doing, the answers came. Writers see characters through the prism of their own personalities. If my characters have depth, it’s because I want to understand them and I want readers to understand them. Nobody is simple. Personally, I want to understand everybody and spend large amounts of time trying to figure out other people and worrying about them (I know, it’s useless to worry).When we writers (including you, dear Richard) write books, we are just reproducing our brains. Therefore, readers aren’t really reading printed words on a page, they’re reading other personalities. That’s one of the reasons reading is so thrilling and why it’s so important for writers to accurately reproduce their “voice.” What is it that best represents your protagonist’s life? (Highlight the characteristics that illustrate your protagonist’s strengths.)Colum’s mother was murdered and his father rejected him. That kind of trauma usually twists people; it creates drives and motives they don’t necessarily understand. Humans must attempt full consciousness to understand themselves (I know, that’s a tall order). Luckily for Colum, when events unfold, he’s willing to face his actions and try to redeem himself. You can attribute that to inner strength, but I think God is willing to give us grace to deal with life, if we’re willing to accept it.Scalp Mountain is clearly historical fiction. While this is true, I found much in common with literary fiction. What do you think makes your novel stand out from other historical fiction?I don’t know, I don’t even know if it does stand out. I just wrote the story in my mind and heart, and wrote my style, whatever that is. I’ve studied literary technique, but that technique is mandatory for all writers, not just historical novelists, or literary novelists. How does your main character’s profession draw him into suspenseful situations, (murder, for instance?) It doesn’t. The events in the book all stem from character. Character is destiny. Colum’s father is a vengeful man. Rather than fight it out, Colum runs from his own guilt, motives and feelings. Lohman can’t handle his unrequited desire for Colum and tries to eliminate the problem the only way he knows how; killing him. Have you considered working on a sequel? No sequels. I’m working on another historical novel now and that has my attention. Besides, Scalp Mountain doesn’t lend itself to sequels. It’s pretty intense and I could never reproduce the same kind of tension in a sequel. Tell me something about your writing habits. Is there a special place where you live that you like to go to? Do you like to write at a certain time of day? This is a problem all writers deal with (unless they have superior self discipline, which I don’t). Between working on publicity, which is an endless job, doing my chores, seeing and talking to friends and family, and making myself stay in the chair, it’s hard. Like all writers, some days I just sit and stare at the computer screen and want to bang my head against the wall. Luckily, the wall is handy, it’s right by my desk.In an added note, I strongly suspect writers who brag they have unbreakable work habits are exaggerating. Please provide links to your blog, your book and other places where readers can find your work. Scalp M0untain on Amazonhttp://www.scalpmountain.comhttp://scalpmountain.blogspot.comhttp://www.venturegalleries.com

July 13, 2012

Julia Robb interview and glowing Reviews for Scalp Mountain

INTERVIEW WITH RON SCHEER

Julia Robb has generously agreed to talk here today about writing and the writing of Scalp Mountain, so I'm turning the rest of this page over to her.

Fellow Texas writer Larry McMurtry has said, “Backward is just not a natural direction for Americans to look—historical ignorance remains a national characteristic.” Would you share that opinion?

Absolutely. Americans do not know or understand their history, and they have been brainwashed to believe in good guys and bad guys: Somebody has to be right. Liberal thinkers enjoy exposing notables as imperfect and more traditional thinkers believe in the myth of the heroic.

The truth is in between. From the beginning of the world, humans have been imperfect and complicated, thus our history has been imperfect and complicated. Thomas Jefferson was an impressive person and one who, with many others, risked everything to fight the English, but he was also human and probably had a slave mistress. Was he a bad man or a good man? Do we judge him by 21st Century standards, or by the standards of his time?

Much of this ignorance stems from America’s eagerness for the future, which produces a reluctance to look back even one day. It’s easier to put things in categories and go on. Mass media also trains people to want pablum. On the other hand, Americans (and probably most of the world) have always preferred the cheap seats.

Big Bend National Park, Texas

How do you define the term “traditional western,” and isScalp Mountain an example of one?

I tried to write Scalp Mountain as a historical novel, meaning a book which helps explain events during a specific time period, and one which embodies themes. Many novels which appear to be Westerns are not; for instance, Tom Lea’s very fine The Wonderful Country.

I urge anyone interested in the frontier, Texas, Mexico and/or art, to read this book (Lea was a visual artist as well as a writer and he illustratedWonderful Country). Lea never got the recognition he deserved for The Wonderful Country.

I guess I don’t know what a traditional Western is. I just take books for what they are.

To what extent did growing up and living in Texas help or hinder the writing of this novel?

I couldn’t have written Scalp Mountain without growing up in Texas, with the distances, the sky spreading to the end of the world. It shaped my spirit, although I’m not sure what shape it took. And Texans are not like other Americans and that has to do with their history; particularly the long, barbaric Comanche wars. It shaped the culture. (Read Empire of the Summer Moon, by S.C. Gwynne, to understand this).

I was exiled in Maryland for fifteen years, working, and I can tell you Maryland is wonderful, but its people were shaped by a whole different ethos.

In reading western fiction, can you tell those who write of Texas from a lifetime of first-hand experience and those who don’t?

I’m not sure, I haven’t read that many historical novels or westerns about Texas. There’s really not a whole lot of them. I can sure tell the late Tom Lea grew up in Texas. His tone, meaning the feel of the place, is perfect.

I’ve found women and men write different kinds of books about Texas, and/or the American West. Women writers tend to be sloppily sentimental about Indians and their culture (by the way, I’ve asked many Indians what they want to be called, Native American, etc. and they always told me they are comfortable with “Indian”).

Men tend to be more rigorous, although not always. One Texas writer wrote a novel from the Comanches’ point of view and he didn’t even mention Comanche raped their women captives to death, or kept them in sexual slavery. This kind of stuff is important because it’s truth.

Santa Elena Canyon, Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park

Did any of the characters surprise you as they took shape in the writing?

Henry surprised me. He turned out to be such a character; a man willing to do what he had to do, but loving in his attitudes, poetic (although a terrible poet) and whimsical. I missed him so much after, well, you know...

How closely does the finished story compare to the way you originally conceived it?

It’s pretty much the way I thought it out. The characters grew a little. And the research produced complete surprises. It was a revelation to find that everybody on the frontier scalped everybody else; white men scalped other white men, whites scalped Indians, Indians scalped Indians, Indians scalped whites. In one instance, some Indian even scalped a white man’s dog. That’s true.

Talk about how you decided on the novel’s title.

This story is about the Indian Wars. I wanted to tell a balanced story and that meant demonstrating that both sides were right, both were wrong and everybody got hurt. The wholesale scalping was the perfect symbol for this. Do you remember the scene where Henry and Colum were riding past “Scalp Mountain,” and Colum told Henry why it was given that name?

Pima caught two Apache and crucified them on the mountain. They used real crosses and tied the Apache to the crosses with green rawhide, then left them to die in the sun. That really happened. I went a step further, to illustrate the book’s theme, by having the Pima decorate the crosses with scalps; white, Indian, Mexican.

To what extent was writing this novel influenced by western movies and TV?

I think all American writers have been influenced by film. We’ve had movies now more than one hundred years and it has trained everyone to see cinemagraphically. I know that’s the way I see, when I’m writing.

Big Bend National Park, Texas

Talk a bit about the creative decisions that went into the cover of the novel.

I looked online for Texas landscape painters and found the wonderful David Forks. When I looked through his online gallery, I found the book cover. It seemed like a perfect illustration for the book, a somber mountain in West Texas.

I’m grateful to David for letting me use his painting and for designing the book cover for me. I urge everyone to go to his online gallery and look at his work. His website is at fineartstudioonline.com, or write him at davidforks.com.

Do women writers bring something to the writing of western fiction that male writers generally don’t?

No.

How would you hope to influence other western writers?

I don’t know how to answer that. We just all do what we do. I guess I do hope writers would delve deeper into events and produce books which are more complex and nuanced about cultures and people. Some idiot, writing on Facebook, recently declared that Custer was a psychopath. Total ignorance. Custer was not a psychopath.

What can readers expect from you next?

I’m not sure. I’ve written sixty pages of a novel I’m not happy with and it’s in a drawer. I have another finished novel, about Texas in the 1960s, about the power struggle between Anglos and Hispanics, but nobody will publish it. Agents say it’s not a genre novel, it isn’t mystery, it isn’t thriller, it isn’t fantasy, it isn’t a Western, etc., so we can’t sell it. I’m almost finished with a movie script based on Scalp Mountain. No telling what will happen to it.

Anything you’d like to talk about that we didn’t cover?

Yes, I believe life is tragic, but tragedy can produce redemption. Art, at its best, produces transcendence. And that’s what I’ve tried to do with this book.

Thanks, Julia. Every success.

Book Review — Scalp Mountain

By Rich Weatherly, "Welcome to my Place" blog.

My Review

Scalp Mountain is historical fiction and I’m a big fan of this genre. Before writing this story, author Julia Robb did extensive research about the history and geography of the region. It shows.

That said, this book has much in common with literary fiction. Throughout most of the story we see the vast expanse of the southern plains, the Guadalupe and Davis Mountains, Rio Grande River and surrounding territory. Julia Robb uses vivid, lyrical prose to show us this landscape. While reading, I was transported back to the 1870s. Her writing takes readers on a ride where they experience the story through all their senses; sight, sound, touch, smell and mental imagery through the use of beautiful word pictures.

Unlike romanticized Hollywood westerns of our parents’ time, in this story you’ll find good and bad on all sides. These truly are three dimensional characters; characters based in the realities of life, not cowboys in white hats and villains in black.

Characters define this story and lead us through the plot. In these characters we see complex personalities. Most of the story is presented through the eyes of the protagonist, Colum McNeal. Colum faces life and death situations from multiple characters who would love to kill him. He understands the motivation of two of them; revenge. Another, long time acquaintance, Mason Lohman is a mystery to him.

Julia Robb relies heavily on inner dialog. You’ll spend almost as much time inside these characters heads as you do watching the action taking place around them. There is a powerful psychological feel to the story.

That said, there are well executed fight scenes; those between individuals and between larger groups; from gun battles to knife fights, you’ll be at the center of the action in these fast paced, rapidly changing scenes.

Julia will help you see touching emotions from many of the characters; not just the protagonist. Much of the story is centered on pioneer settlers and their Native American rivals; other parts between Texas Rangers and theU.S. Cavalry. You’ll get a balanced, realist portrayal of each. Clementine Weaver, the wife of one of Colum’s neighbor, has adopted an Apache orphan. This orphan child is the son of José Ortero, a Jacarilla Apache and at one point we see his love for the child. Column is drawn to her as she nurses him through recovery after a brutal attack. His feelings become much more than sentimental.

Mankind has a history of brutality during war. Scalp Mountain doesn’t look the other way when it comes to violence. These scenes of gruesome violence will make you shudder at the harsh realities we humans foist upon one another. Atrocities occurred upon and from each of the opposing groups.

You’ll find things about the white pioneers and the Apaches you admire. I think you’ll come away with a fuller, richer understanding of the real dynamics of the late 1800s in West Texas.

The author has done thorough research and that research has paid dividends in this well written story about difficult times and circumstances.

THURSDAY, JULY 5, 2012

SCALP MOUNTAIN REVIEWED BY KIRKUS, posted June 29

Robb, Julia

Amazon Digital Services (274 pp.)

$2.99 e-book

BOOK REVIEW

Family dramas propel this spare, anti-romantic western.

The title may be slightly misleading: While this Western takes place in the mountainous West Texas region, the emphasis is mostly on the “scalp” part. As a Texas Ranger explains to a friend’s Baltimore-born wife, when it comes to

scalping, “Sister, we all do it. The rangers do it, the feuding folks do it to each other, to white folks just like them, the feathered folks all do it, I know for a fact the Comanch onest scalped a white man’s dog.”

Robb’s debut doesn’t graphically describe the violence promised by this statement, but it doesn’t paper over it with any romantic notions

either. There’s more here of Cormac McCarthy than Zane Gray, especially in the character of Colum McNeal, with his fierce temper and dream of settling down to breeding horses.

Unfortunately for that dream, McNeal is hunted by an Apache who blames him for the death of his son; and by a man who may have been hired by McNeal’s father after Colum was involved in a family tragedy. The issue of parents and sons is emphasized by Colum’s more-than-friendly interest in his friend’s wife, who is raising an adopted Apache child, the last surviving son of the Apache hunting Colum.

The kidnapping and effort to rescue of this child dominates the second half of the book, giving the novel a propulsive plot that some of the earlier chapters lack. But the occasionally episodic structure allows Robb to dip in and out of characters’ heads to give their point of view: No one is a villain in their own mind and every character here has a tale to tell—often violent, potentially redemptive, at least sympathetically told.

Occasional slips may bump the reader out of the story, such as when a character refers to a “hale” of bullets, rather than a “hail”; or when a horse’s “bridle” becomes a “bridal.” Perhaps the addition of a map might also help readers unfamiliar with this territory.

Deep research and empathy for her rounded characters make this Western stand out.

Posted by Julia Robb at 8:29 AM 1 comment:

Email This

BlogThis!

Share to Twitter

Share to Facebook

SATURDAY, JUNE 23, 2012

Review: Scalp Mountain by Julia Robb

My Two Cents:

I love historical fiction but I can get tired of reading about the same places, people and events over and over again. I love when an author can take me to a new place and time. Julia Robb does just that with Scalp Mountain. The author takes us to late 1800s Texas and the surrounding areas. At that point in time, the middle part of the country was still wild. The white people who ventured out west from the East Coast were often the only people of their race for a long time. To say that there was tension between these white settlers and the Native Americans, who had been forced on to reservations by then, would be a complete understatement.

The book is really about the struggle between the white settlers and the Native Americans. I thought that Robb did a good job of making the reader feel the plight of both the white settlers and the Native Americans although the books mostly focuses on the white settlers and is therefore more sympathetic towards them.

I really liked the descriptions of life out on the frontier. There was so much going on, especially for poor Colum, one of the main characters in the book. His father sent a gunman after him after he thinks that Colum killed his own brother. Colum is also trying to flee the Native Americans. He leads an exciting life to say the least.

I also really liked Clementine's story. She is definitely a woman before her time. She's strong and resourceful and she doesn't worry too, too much about what other people say about her. She adopts a Native American child after he's found. This doesn't make her too popular with the other women around but she becomes completely dedicated to her son, James.

This is a good story about the not so pretty history of our country told in such a way that it will grab you and hold on to you until the very last page.

WEDNESDAY, MAY 30, 2012

SCALP MOUNTAIN Review and Interview

By Ron Scheer

buddiesinthesaddle@blogspot.com

This is a fine novel. If you drew a line between Lonesome Dove and All the Pretty Horses, you would find Scalp Mountainsomewhere along the way. Robb immerses you in a West that is saturated in violence and the sorrows that violence brings with it.

It is the 1870s in the border country along the Rio Grande and points west. The killing fields of the Civil War are a fresh memory, and the atrocities of the Indian Wars continue to haunt the days and nights of both whites and Apaches.

Plot. In the midst of all this, a young man, Colum McNeal, is pursued by killers. A fugitive, he has blood on his hands, having done the unspeakable, killing his own brother. He believes his pursuers are gunmen hired by his enraged father. One of them, Lohman, is a man he’s known for many years, who has mysterious reasons of his own for stalking him.

He has also been picked out for revenge by an Apache, Jose Otero, whose family has been killed by whites and his infant son taken. A fierce warrior, he thinks of himself as already dead. He is driven only by his last desire to break the hearts of those who have broken his own and his people’s spirits.

Ocotillo, Big Bend National Park, Texas

A well-meaning ranger, Captain Henry, complicates matters by saving the life of Otero’s infant son and giving him to the care of a childless couple, Michael and Clementine. When Otero abducts Clementine and his son, there follows a long chase into the Big Bend country, an arid and unpopulated desert region along the Mexican border.

Among this party of soldiers and civilians, lives are lost in firefights with Otero’s men. When Clementine is found, most of the surviviors turn back, leaving Colum and a handful of others to follow Otero. Among them are the generous and fatherly Captain Henry and the mysterious Lohman.

There are still many treacherous miles to cover and several turns of plot before the story reaches its end, steeped in more bloodshed and sorrows. Robb leaves a reader with this feeling you get sometimes from both McMurtry and McCarthy, that the West was won at a terrible cost, whether men or women, Indian or white, living or dead.

Heroism. The novel is compelling for the way it takes the elements of the traditional western and casts them in an unaccustomed light. Elmer Kelton would do something similar in his Texas Ranger trilogy, Lone Star Rising, but his focus is on the heroism found on both sides of the Indian Wars.

Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park, Texas

Robb looks past that, not to deny it, but to shake us to the core with the uncertainties and anxieties of living in those times. Also, to strip away some of the myth that obscures history. She humanizes the heroism, and doing so bonds us to her characters as people with hopes, fears, and mixed motives little different from our own.

Some might call her central character, Colum, an anti-hero. He harks back to Cain, the brother-murdering son of Adam and Eve. Alone in the world, he is haunted by guilt, regrets, and painful memories. A sexual urgency in him draws him powerfully to the wife of his friend Michael. We admire him finally for the courage to face whatever threatens to kill him, including his unforgiving father.

Wrapping up. As I began by saying, this is a fine novel. I rarely say about a novel that it was hard to put down. That’s no reflection on good writing; I’m just easily distracted. But there were times when this one had me and refused to let go. For anyone who likes their westerns well grounded in history, this is one you don’t want to miss.

Julia Robb describes herself as a former journalist and magazine writer, who grew up in small-town Texas. She now lives in Marshall, Texas, where she works as a free-lance editor. You can read about her life growing up in small-town Texas at her blog. Scalp Mountain is currently available as an ebook for the kindle.Julia Robb

JULY 13, 2012 · 10:24 AM↓ Jump to Comments Book Revi...

JULY 13, 2012 · 10:24 AM↓ Jump to Comments Book Review — Scalp Mountain

By Rich Weatherly, "Welcome to my Place" blog.

My ReviewScalp Mountain is historical fiction and I’m a big fan of this genre. Before writing this story, author Julia Robb did extensive research about the history and geography of the region. It shows.That said, this book has much in common with literary fiction. Throughout most of the story we see the vast expanse of the southern plains, the Guadalupe and Davis Mountains, Rio Grande River and surrounding territory. Julia Robb uses vivid, lyrical prose to show us this landscape. While reading, I was transported back to the 1870s. Her writing takes readers on a ride where they experience the story through all their senses; sight, sound, touch, smell and mental imagery through the use of beautiful word pictures.Unlike romanticized Hollywood westerns of our parents’ time, in this story you’ll find good and bad on all sides. These truly are three dimensional characters; characters based in the realities of life, not cowboys in white hats and villains in black.Characters define this story and lead us through the plot. In these characters we see complex personalities. Most of the story is presented through the eyes of the protagonist, Colum McNeal. Colum faces life and death situations from multiple characters who would love to kill him. He understands the motivation of two of them; revenge. Another, long time acquaintance, Mason Lohman is a mystery to him.Julia Robb relies heavily on inner dialog. You’ll spend almost as much time inside these characters heads as you do watching the action taking place around them. There is a powerful psychological feel to the story.That said, there are well executed fight scenes; those between individuals and between larger groups; from gun battles to knife fights, you’ll be at the center of the action in these fast paced, rapidly changing scenes.Julia will help you see touching emotions from many of the characters; not just the protagonist. Much of the story is centered on pioneer settlers and their Native American rivals; other parts between Texas Rangers and theU.S. Cavalry. You’ll get a balanced, realist portrayal of each. Clementine Weaver, the wife of one of Colum’s neighbor, has adopted an Apache orphan. This orphan child is the son of José Ortero, a Jacarilla Apache and at one point we see his love for the child. Column is drawn to her as she nurses him through recovery after a brutal attack. His feelings become much more than sentimental.Mankind has a history of brutality during war. Scalp Mountain doesn’t look the other way when it comes to violence. These scenes of gruesome violence will make you shudder at the harsh realities we humans foist upon one another. Atrocities occurred upon and from each of the opposing groups.You’ll find things about the white pioneers and the Apaches you admire. I think you’ll come away with a fuller, richer understanding of the real dynamics of the late 1800s in West Texas.The author has done thorough research and that research has paid dividends in this well written story about difficult times and circumstances.

My ReviewScalp Mountain is historical fiction and I’m a big fan of this genre. Before writing this story, author Julia Robb did extensive research about the history and geography of the region. It shows.That said, this book has much in common with literary fiction. Throughout most of the story we see the vast expanse of the southern plains, the Guadalupe and Davis Mountains, Rio Grande River and surrounding territory. Julia Robb uses vivid, lyrical prose to show us this landscape. While reading, I was transported back to the 1870s. Her writing takes readers on a ride where they experience the story through all their senses; sight, sound, touch, smell and mental imagery through the use of beautiful word pictures.Unlike romanticized Hollywood westerns of our parents’ time, in this story you’ll find good and bad on all sides. These truly are three dimensional characters; characters based in the realities of life, not cowboys in white hats and villains in black.Characters define this story and lead us through the plot. In these characters we see complex personalities. Most of the story is presented through the eyes of the protagonist, Colum McNeal. Colum faces life and death situations from multiple characters who would love to kill him. He understands the motivation of two of them; revenge. Another, long time acquaintance, Mason Lohman is a mystery to him.Julia Robb relies heavily on inner dialog. You’ll spend almost as much time inside these characters heads as you do watching the action taking place around them. There is a powerful psychological feel to the story.That said, there are well executed fight scenes; those between individuals and between larger groups; from gun battles to knife fights, you’ll be at the center of the action in these fast paced, rapidly changing scenes.Julia will help you see touching emotions from many of the characters; not just the protagonist. Much of the story is centered on pioneer settlers and their Native American rivals; other parts between Texas Rangers and theU.S. Cavalry. You’ll get a balanced, realist portrayal of each. Clementine Weaver, the wife of one of Colum’s neighbor, has adopted an Apache orphan. This orphan child is the son of José Ortero, a Jacarilla Apache and at one point we see his love for the child. Column is drawn to her as she nurses him through recovery after a brutal attack. His feelings become much more than sentimental.Mankind has a history of brutality during war. Scalp Mountain doesn’t look the other way when it comes to violence. These scenes of gruesome violence will make you shudder at the harsh realities we humans foist upon one another. Atrocities occurred upon and from each of the opposing groups.You’ll find things about the white pioneers and the Apaches you admire. I think you’ll come away with a fuller, richer understanding of the real dynamics of the late 1800s in West Texas.The author has done thorough research and that research has paid dividends in this well written story about difficult times and circumstances.July 5, 2012

SCALP MOUNTAIN REVIEWED BY KIRKUS, posted June 29Robb, Ju...

SCALP MOUNTAIN REVIEWED BY KIRKUS, posted June 29

Robb, JuliaAmazon Digital Services (274 pp.)$2.99 e-book

BOOK REVIEW

Family dramas propel this spare, anti-romantic western. The title may be slightly misleading: While this Western takes place in the mountainous West Texas region, the emphasis is mostly on the “scalp” part. As a Texas Ranger explains to a friend’s Baltimore-born wife, when it comes toscalping, “Sister, we all do it. The rangers do it, the feuding folks do it to each other, to white folks just like them, the feathered folks all do it, I know for a fact the Comanch onest scalped a white man’s dog.” Robb’s debut doesn’t graphically describe the violence promised by this statement, but it doesn’t paper over it with any romantic notionseither. There’s more here of Cormac McCarthy than Zane Gray, especially in the character of Colum McNeal, with his fierce temper and dream of settling down to breeding horses. Unfortunately for that dream, McNeal is hunted by an Apache who blames him for the death of his son; and by a man who may have been hired by McNeal’s father after Colum was involved in a family tragedy. The issue of parents and sons is emphasized by Colum’s more-than-friendly interest in his friend’s wife, who is raising an adopted Apache child, the last surviving son of the Apache hunting Colum. The kidnapping and effort to rescue of this child dominates the second half of the book, giving the novel a propulsive plot that some of the earlier chapters lack. But the occasionally episodic structure allows Robb to dip in and out of characters’ heads to give their point of view: No one is a villain in their own mind and every character here has a tale to tell—often violent, potentially redemptive, at least sympathetically told. Occasional slips may bump the reader out of the story, such as when a character refers to a “hale” of bullets, rather than a “hail”; or when a horse’s “bridle” becomes a “bridal.” Perhaps the addition of a map might also help readers unfamiliar with this territory. Deep research and empathy for her rounded characters make this Western stand out.

June 23, 2012

Review: Scalp Mountain by Julia RobbTitle: Scalp Mountain...

Review: Scalp Mountain by Julia RobbTitle: Scalp Mountain

Author: Julia Robb

Format: Ebook

Publisher: Self-published

Publish Date: February 19, 2012

Source: I received a copy from the author. This did not affect my review.

Why You're Reading This Book:

You're a historical fiction fan.What's the Story?:

From Goodreads.com: "It’s 1876 at Scalp Mountain and Colum McNeal is fleeing gunmen sent by his Irish-immigrant father. Colum pioneers a Texas ranch, a home which means everything to him, but struggles to stay there: José Ortero, a Jacarilla Apache, seeks revenge for the son Colum unwittingly killed.

At the same time, an old acquaintance, Mason Lohman, obsessively stalks Colum through the border country, planning to take his life. Colum has inspired the unthinkable in Lohman. In a time and place where a man’s sexuality must stand unchallenged, Colum has ignited Lohman’s desire.

Other characters include Texas Ranger William Henry, who takes Colum’s part against his father while wrestling with his own demons. Henry’s family was murdered by Comanches and he regrets the revenge he took; and Clementine Weaver, who defies frontier prejudice by adopting an Indian baby, must choose between Colum and her husband.

Scalp Mountain is based on the Southern Plains’ Indian Wars.

Those wars were morally complex, and the novel attempts to reflect those profound, tragic and murderous complications.

Everyone was right, everyone was wrong, everyone got hurt."

My Two Cents:

I love historical fiction but I can get tired of reading about the same places, people and events over and over again. I love when an author can take me to a new place and time. Julia Robb does just that with Scalp Mountain. The author takes us to late 1800s Texas and the surrounding areas. At that point in time, the middle part of the country was still wild. The white people who ventured out west from the East Coast were often the only people of their race for a long time. To say that there was tension between these white settlers and the Native Americans, who had been forced on to reservations by then, would be a complete understatement.

The book is really about the struggle between the white settlers and the Native Americans. I thought that Robb did a good job of making the reader feel the plight of both the white settlers and the Native Americans although the books mostly focuses on the white settlers and is therefore more sympathetic towards them.

I really liked the descriptions of life out on the frontier. There was so much going on, especially for poor Colum, one of the main characters in the book. His father sent a gunman after him after he thinks that Colum killed his own brother. Colum is also trying to flee the Native Americans. He leads an exciting life to say the least.

I also really liked Clementine's story. She is definitely a woman before her time. She's strong and resourceful and she doesn't worry too, too much about what other people say about her. She adopts a Native American child after he's found. This doesn't make her too popular with the other women around but she becomes completely dedicated to her son, James.

This is a good story about the not so pretty history of our country told in such a way that it will grab you and hold on to you until the very last page.

June 21, 2012

Scalp Mountain review postponed until Saturday, June 23, ...

June 20, 2012

Look for the next "Scalp Mountain" review on June 21. See...

May 30, 2012

SCALP MOUNTAIN Review and Interview

buddiesinthesaddle@blogspot.com

This is a fine novel. If you drew a line between Lonesome Doveand All the Pretty Horses, you would find Scalp Mountainsomewhere along the way. Robb immerses you in a West that is saturated in violence and the sorrows that violence brings with it.

It is the 1870s in the border country along the Rio Grande and points west. The killing fields of the Civil War are a fresh memory, and the atrocities of the Indian Wars continue to haunt the days and nights of both whites and Apaches.

Plot. In the midst of all this, a young man, Colum McNeal, is pursued by killers. A fugitive, he has blood on his hands, having done the unspeakable, killing his own brother. He believes his pursuers are gunmen hired by his enraged father. One of them, Lohman, is a man he’s known for many years, who has mysterious reasons of his own for stalking him.

He has also been picked out for revenge by an Apache, Jose Otero, whose family has been killed by whites and his infant son taken. A fierce warrior, he thinks of himself as already dead. He is driven only by his last desire to break the hearts of those who have broken his own and his people’s spirits.

Ocotillo, Big Bend National Park, TexasA well-meaning ranger, Captain Henry, complicates matters by saving the life of Otero’s infant son and giving him to the care of a childless couple, Michael and Clementine. When Otero abducts Clementine and his son, there follows a long chase into the Big Bend country, an arid and unpopulated desert region along the Mexican border.

Ocotillo, Big Bend National Park, TexasA well-meaning ranger, Captain Henry, complicates matters by saving the life of Otero’s infant son and giving him to the care of a childless couple, Michael and Clementine. When Otero abducts Clementine and his son, there follows a long chase into the Big Bend country, an arid and unpopulated desert region along the Mexican border.Among this party of soldiers and civilians, lives are lost in firefights with Otero’s men. When Clementine is found, most of the surviviors turn back, leaving Colum and a handful of others to follow Otero. Among them are the generous and fatherly Captain Henry and the mysterious Lohman.

There are still many treacherous miles to cover and several turns of plot before the story reaches its end, steeped in more bloodshed and sorrows. Robb leaves a reader with this feeling you get sometimes from both McMurtry and McCarthy, that the West was won at a terrible cost, whether men or women, Indian or white, living or dead.

Heroism. The novel is compelling for the way it takes the elements of the traditional western and casts them in an unaccustomed light. Elmer Kelton would do something similar in his Texas Ranger trilogy, Lone Star Rising, but his focus is on the heroism found on both sides of the Indian Wars.

Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park, TexasRobb looks past that, not to deny it, but to shake us to the core with the uncertainties and anxieties of living in those times. Also, to strip away some of the myth that obscures history. She humanizes the heroism, and doing so bonds us to her characters as people with hopes, fears, and mixed motives little different from our own.

Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park, TexasRobb looks past that, not to deny it, but to shake us to the core with the uncertainties and anxieties of living in those times. Also, to strip away some of the myth that obscures history. She humanizes the heroism, and doing so bonds us to her characters as people with hopes, fears, and mixed motives little different from our own.Some might call her central character, Colum, an anti-hero. He harks back to Cain, the brother-murdering son of Adam and Eve. Alone in the world, he is haunted by guilt, regrets, and painful memories. A sexual urgency in him draws him powerfully to the wife of his friend Michael. We admire him finally for the courage to face whatever threatens to kill him, including his unforgiving father.

Wrapping up. As I began by saying, this is a fine novel. I rarely say about a novel that it was hard to put down. That’s no reflection on good writing; I’m just easily distracted. But there were times when this one had me and refused to let go. For anyone who likes their westerns well grounded in history, this is one you don’t want to miss.

Julia Robb describes herself as a former journalist and magazine writer, who grew up in small-town Texas. She now lives in Marshall, Texas, where she works as a free-lance editor. You can read about her life growing up in small-town Texas at her blog. Scalp Mountain is currently available as an ebook for the kindle.

Julia RobbInterview

Julia RobbInterviewJulia Robb has generously agreed to talk here today about writing and the writing ofScalp Mountain, so I'm turning the rest of this page over to her.

Fellow Texas writer Larry McMurtry has said, “Backward is just not a natural direction for Americans to look—historical ignorance remains a national characteristic.” Would you share that opinion?Absolutely. Americans do not know or understand their history, and they have been brainwashed to believe in good guys and bad guys: Somebody has to be right. Liberal thinkers enjoy exposing notables as imperfect and more traditional thinkers believe in the myth of the heroic.

The truth is in between. From the beginning of the world, humans have been imperfect and complicated, thus our history has been imperfect and complicated. Thomas Jefferson was an impressive person and one who, with many others, risked everything to fight the English, but he was also human and probably had a slave mistress. Was he a bad man or a good man? Do we judge him by 21st Century standards, or by the standards of his time?

Much of this ignorance stems from America’s eagerness for the future, which produces a reluctance to look back even one day. It’s easier to put things in categories and go on. Mass media also trains people to want pablum. On the other hand, Americans (and probably most of the world) have always preferred the cheap seats.

Big Bend National Park, TexasHow do you define the term “traditional western,” and isScalp Mountain an example of one?I tried to write Scalp Mountain as a historical novel, meaning a book which helps explain events during a specific time period, and one which embodies themes. Many novels which appear to be Westerns are not; for instance, Tom Lea’s very fine The Wonderful Country.

Big Bend National Park, TexasHow do you define the term “traditional western,” and isScalp Mountain an example of one?I tried to write Scalp Mountain as a historical novel, meaning a book which helps explain events during a specific time period, and one which embodies themes. Many novels which appear to be Westerns are not; for instance, Tom Lea’s very fine The Wonderful Country.I urge anyone interested in the frontier, Texas, Mexico and/or art, to read this book (Lea was a visual artist as well as a writer and he illustratedWonderful Country). Lea never got the recognition he deserved for The Wonderful Country.

I guess I don’t know what a traditional Western is. I just take books for what they are.

To what extent did growing up and living in Texas help or hinder the writing of this novel?I couldn’t have written Scalp Mountain without growing up in Texas, with the distances, the sky spreading to the end of the world. It shaped my spirit, although I’m not sure what shape it took. And Texans are not like other Americans and that has to do with their history; particularly the long, barbaric Comanche wars. It shaped the culture. (Read Empire of the Summer Moon, by S.C. Gwynne, to understand this).

I was exiled in Maryland for fifteen years, working, and I can tell you Maryland is wonderful, but its people were shaped by a whole different ethos.

In reading western fiction, can you tell those who write of Texas from a lifetime of first-hand experience and those who don’t?I’m not sure, I haven’t read that many historical novels or westerns about Texas. There’s really not a whole lot of them. I can sure tell the late Tom Lea grew up in Texas. His tone, meaning the feel of the place, is perfect.

I’ve found women and men write different kinds of books about Texas, and/or the American West. Women writers tend to be sloppily sentimental about Indians and their culture (by the way, I’ve asked many Indians what they want to be called, Native American, etc. and they always told me they are comfortable with “Indian”).

Men tend to be more rigorous, although not always. One Texas writer wrote a novel from the Comanches’ point of view and he didn’t even mention Comanche raped their women captives to death, or kept them in sexual slavery. This kind of stuff is important because it’s truth.

Santa Elena Canyon, Rio Grande, Big Bend National ParkDid any of the characters surprise you as they took shape in the writing?Henry surprised me. He turned out to be such a character; a man willing to do what he had to do, but loving in his attitudes, poetic (although a terrible poet) and whimsical. I missed him so much after, well, you know...

Santa Elena Canyon, Rio Grande, Big Bend National ParkDid any of the characters surprise you as they took shape in the writing?Henry surprised me. He turned out to be such a character; a man willing to do what he had to do, but loving in his attitudes, poetic (although a terrible poet) and whimsical. I missed him so much after, well, you know...How closely does the finished story compare to the way you originally conceived it?It’s pretty much the way I thought it out. The characters grew a little. And the research produced complete surprises. It was a revelation to find that everybody on the frontier scalped everybody else; white men scalped other white men, whites scalped Indians, Indians scalped Indians, Indians scalped whites. In one instance, some Indian even scalped a white man’s dog. That’s true.

Talk about how you decided on the novel’s title.This story is about the Indian Wars. I wanted to tell a balanced story and that meant demonstrating that both sides were right, both were wrong and everybody got hurt. The wholesale scalping was the perfect symbol for this. Do you remember the scene where Henry and Colum were riding past “Scalp Mountain,” and Colum told Henry why it was given that name?

Pima caught two Apache and crucified them on the mountain. They used real crosses and tied the Apache to the crosses with green rawhide, then left them to die in the sun. That really happened. I went a step further, to illustrate the book’s theme, by having the Pima decorate the crosses with scalps; white, Indian, Mexican.

To what extent was writing this novel influenced by western movies and TV?I think all American writers have been influenced by film. We’ve had movies now more than one hundred years and it has trained everyone to see cinemagraphically. I know that’s the way I see, when I’m writing.

Big Bend National Park, TexasTalk a bit about the creative decisions that went into the cover of the novel.I looked online for Texas landscape painters and found the wonderful David Forks. When I looked through his online gallery, I found the book cover. It seemed like a perfect illustration for the book, a somber mountain in West Texas.

Big Bend National Park, TexasTalk a bit about the creative decisions that went into the cover of the novel.I looked online for Texas landscape painters and found the wonderful David Forks. When I looked through his online gallery, I found the book cover. It seemed like a perfect illustration for the book, a somber mountain in West Texas.I’m grateful to David for letting me use his painting and for designing the book cover for me. I urge everyone to go to his online gallery and look at his work. His website is at fineartstudioonline.com, or write him at davidforks.com.

Do women writers bring something to the writing of western fiction that male writers generally don’t?No.

How would you hope to influence other western writers?I don’t know how to answer that. We just all do what we do. I guess I do hope writers would delve deeper into events and produce books which are more complex and nuanced about cultures and people. Some idiot, writing on Facebook, recently declared that Custer was a psychopath. Total ignorance. Custer was not a psychopath.

What can readers expect from you next?I’m not sure. I’ve written sixty pages of a novel I’m not happy with and it’s in a drawer. I have another finished novel, about Texas in the 1960s, about the power struggle between Anglos and Hispanics, but nobody will publish it. Agents say it’s not a genre novel, it isn’t mystery, it isn’t thriller, it isn’t fantasy, it isn’t a Western, etc., so we can’t sell it. I’m almost finished with a movie script based on Scalp Mountain. No telling what will happen to it.

Anything you’d like to talk about that we didn’t cover?Yes, I believe life is tragic, but tragedy can produce redemption. Art, at its best, produces transcendence. And that’s what I’ve tried to do with this book.

Thanks, Julia. Every success.