Julia Robb's Blog, page 4

January 19, 2016

Greg Michno, Sand Creek and The End of History

Mr. Michno is one of the foremost historians of the American West, having researched and written more than a dozen books about the West. But Michno is not one of the foremost historians because he wrote the books, but because he does not compromise: He tells the truth whether readers like that truth or not.

Mr. Michno’s last book, Battle At Sand Creek: A Military Perspective, does not feed us the usual dose of outrage at what happened at Sand Creek (Nov. 29, 1864), but a more balanced perspective.

Mr. Michno’s last book, Battle At Sand Creek: A Military Perspective, does not feed us the usual dose of outrage at what happened at Sand Creek (Nov. 29, 1864), but a more balanced perspective.

Now, he has expanded the first Sand Creek book and published The Three Battles of Sand Creek: The Cheyenne Massacre in Blood, in Court, and as the End of History.

The book will be released in April, and readers can order it now through Amazon.

Robb: How does The Three Battles of Sand Creek: The Cheyenne Massacre in Blood, in Court, and as the End of History differ from The Battle of Sand Creek: A Military Perspective?

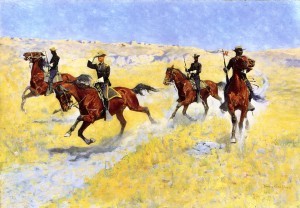

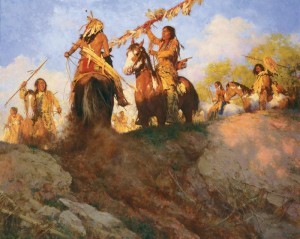

Michno: Battle at Sand Creek: The Military Perspective (Upton & Sons, 2004) was a detailed narrative history of the events preceding the Sand Creek affair and an extensive treatment of the two-day fight/massacre. I tried to present the military perspective to balance the prevailing pro-Indian viewpoint in vogue for the past half-century or more.

Sand Creek, by Howling Wolf

The evidence actually shows that the affair did have some aspects of a battle, although one accompanied by dreadful atrocities.

What I found out was that few people wanted to entertain the non-standard perspective.

Instead, I decided to try to find out what made the Sand Creek story so divisive and why facts do not seem to matter.

The Three Battles of Sand Creek (SavasBeatie, 2016) begins with a factual treatment of the two-day incident, but the focus, I believe, is in the third section, with an analysis of eyewitness testimony and memory. We find that eyewitnesses, as police have known for years, can be extremely unreliable at “remembering” what they allegedly saw. Memories are invented, tentative, and malleable; they can be created and destroyed like Frankenstein’s monster.

Since we filter the world through individual lenses, facts are personal perceptions, true only for the person doing the filtering. It is a postmodernist view, without a universal narrative, and truth is illusory. It may sound trite, but Sand Creek is in the eye of the beholder, and no amount of facts will change one’s mind. We can only see what we already believe.

Robb: According to your first book on this subject, history has overlooked that the Colorado troops at Sand Creek sustained 76 casualties, the sixth highest in the 1,450 battles fought between whites and Indians between 1850-1890, that the Cheyenne had been fighting and raiding all summer and into the fall, that warriors who had been raiding were living in the village when it was hit by soldiers, and other pertinent details.

Robb: According to your first book on this subject, history has overlooked that the Colorado troops at Sand Creek sustained 76 casualties, the sixth highest in the 1,450 battles fought between whites and Indians between 1850-1890, that the Cheyenne had been fighting and raiding all summer and into the fall, that warriors who had been raiding were living in the village when it was hit by soldiers, and other pertinent details.

But you indicated that few people believed these facts made a difference, or even agreed they were facts at all. Has anything changed since publication?

Michno: The number of soldier casualties always seems to be undercounted, which contributes to the perception of a one-sided fight. A thorough search of existing records, including remembrances and newspapers, show 25 soldiers were killed and 51 wounded, which is very high for western Indian war fights.

People have argued that the high number of soldier casualties was because they were self-inflicted by “friendly fire.”

Actually, we have descriptions of 29 of the wounds: 16 were from arrows and 13 were from bullets. The soldiers did not pick up bows and arrows and shoot themselves. Also, friendly fire is a two-way street: both sides are just as apt to mistakenly hit their own.

Many of these Indians had been raiding all summer and were in the village. But many of them were innocent. Did the women and children aid and abet the warriors? Very likely. If so, were they legitimate targets?

Consider, however, that white women and children on the frontier were killed by Indians in the same manner. They were either all legitimate targets, or none of them were.

Do any of these facts make a difference? Probably not. Remember, we are social animals and we connect to personal narratives; we love storytelling; we love anecdotes more than statistics. It doesn’t matter if there were 76 soldier casualties—that’s just a statistic. The mutilated, pregnant Indian woman is the headline. There’s our anecdote. That is our human nature; that is our gut talking.

Carl Sagan was once asked what his “gut feeling” was. He answered that he didn’t think with his gut, he used his head. Many of us don’t.

I don’t believe that anything has changed in the perception of Sand Creek, or that anything will. What I hope is that those who read the book will possibly come away with some understanding as to why they will not change their minds, no matter what the facts are.

Robb: You’ve indicated that our prejudices decide what we believe to be true. Why is that?

A. We are all controlled by subconscious psychological processes in our brains, some which may be from nature, but most from nurture; learned from our parents, teachers, churches, friends, workplace, and countless interactions. Free will may be less of a factor than determinism.

Our preconceptions, our prejudices are ingrained. We may think and act as we do not from uninhibited choice, but from an over-active amygdala. This brain area, associated with “fight or flight” and “gut” reaction, probably has more subconscious control over our thoughts and actions than we would like to admit. It’s just another reason why facts don’t make a difference.

Robb: What did you find out investigating the contradictory testimony, and what was said in court?

Col. John M. Chivington

Michno: The Denver Military Commission, the Congressional Inquiry in Washington, and Senator James Doolittle’s Commission, all sought “to inquire into and report all the facts connected with the late attack” at Sand Creek. They also wanted someone to blame.

The Denver Commission exemplified the proceedings. John Chivington, who was the defendant even though he was not supposedly on trial, objected to questions and proceedings and was sustained 37% of the time; Sam Tappan, who hated Chivington and was head of the tribunal, sustained 93% of his own motions. In addition, there were nearly 700 soldiers in the Sand Creek campaign, but only 59 were questioned, and only 28 were eyewitnesses of the actual events.

One might think that the majority of witnesses chosen would have been people who had actually been there.

Extremely poor question framing had a great impact. In Ben Wade’s committee, for instance, D. W. Gooch asked John Evans if there was “any justification for the attack made by Colonel Chivington on these friendly Indians…?” William Windom asked him if there was “any palliation or excuse for that massacre,” and James Doolittle asked Sam Colley, “Was it the First Colorado Regiment that joined in this massacre, or was it the one-hundred-day men that were raised?”

Whether or not the Indians were friendly or if they were massacred were the very things the inquiries were supposedly designed to find out, but the answers were implicit in the questions.

As for the testimony, it was so completely contradictory, that one might believe the witnesses were describing different events. Not only did different witnesses give disparate stories, but sometimes the same witnesses told different stories.

For instance, one of the key witnesses was Capt. Silas Soule. He said, “I refused to fire,” but he also said Major Anthony ordered him to fire and “some firing was done.” When Soule was asked if he saw any soldiers scalping or mutilating Indians, he once testified, “I did,” and another time he testified, “I think not.”

Captain Silas Soule

Senator Doolittle’s report is often cited as the final explanation as to what happened: lawless white men always caused all the trouble and Sand Creek was a massacre of peaceful Indians who were under army protection. Another commissioner, Oregon Senator James W. Nesmith, wrote a sub-report with a totally different view. He called the Indians the instigators of all the trouble because of “their constitutional and ingrained tendency to rob and murder.”

Nesmith’s view was just as biased as Doolittle’s—the former’s villains were Indians, and the latter’s were whites. Doolittle of Wisconsin, and Nesmith of Oregon—Easterners and Westerners—saw the facts through different lenses. Was one right and one wrong, or were they both right, or both wrong?

It could be that the evidence was completely irrelevant because they were predisposed to come to the conclusions they did regardless of the facts. Confirmation bias forced them to reinforce one set of “truths” and discount the other. One man’s fact is another man’s falsehood.

Robb: Why is this the “End of History?”

Michno: There has been much written about history’s demise. In The Republic, Plato talked about the “dialectic,” which was a type of logical process of reasoned argumentation in which opposing viewpoints are eventually solved, ending the controversy. The idea was refined by the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel. The famous Hegelian Dialectic (logical argument) posits that every attempt to formulate conceptions about the world (thesis) is contradicted by another formulation (antithesis), and the conflict between the two is eventually resolved (synthesis). The dialectic is ended—for a time—for internal inconsistencies will eventually serve as a thesis for a new dialectic.

Will the dialectic ever lead us to nirvana? Its course seems to be progressive and linearly ascendant, because each new thesis represents an advance over the previous thesis until an endpoint is reached. In the final culmination there will be a complete objectification of thought and mind into a basic independent entity, devoid of all personality. The absolute mind becomes the real universe, marching toward full self-realization. It must be like Star Trek’s Dr. Spock trying to do a mind-meld with the universe.

What would happen if the grand finale of universal enlightenment closed the curtain? For Hegel, without the active opposition of an antithesis working through the dialectic, existence would be hollow. Man would have no reason to live without a search for Reason. The entire scheme collapses. Hegel, followed by Nietzsche, are blamed for setting us on the road to postmodernism.

What would happen if the grand finale of universal enlightenment closed the curtain? For Hegel, without the active opposition of an antithesis working through the dialectic, existence would be hollow. Man would have no reason to live without a search for Reason. The entire scheme collapses. Hegel, followed by Nietzsche, are blamed for setting us on the road to postmodernism.

Nevertheless, Hegel’s Dialectic seems viable. It proceeds forward a step at a time, each new synthesis an advancement over the preceding, until the final goal of absolute Reason is realized—the end of history—which is nothing more than cognitive dissonance and its reduction.

In our postmodernist world there will also be an end of history, but only because there will be no universal truth to discover; the continuous dissonance and its constant reduction is on a personal, individual, never ending treadmill.

Discovering the final truth would end history as much as spinning in a perpetual circle, trapped in a maze with no outlet, which is the actual case when we continuously battle our psychological demons, searching for that ever elusive stasis.

Dialectic and dissonance use the same ladder. History will not end because we have reached universal Reason, it will end because we will never even agree on the rules with which to begin the search. We are in a constant dissonance-reducing battle with history either to forget it or sugar-coat it. Ours is a history filled with prejudice, intolerance, hatred, and war. We do not want to remember it as it truly was.

The act of repainting our own history is what we find on a macro scale, since that is exactly what we do with our memories on a micro scale. In the Sand Creek example, there is a constant argument and no synthesis ever occurs because the thesis-antithesis is never discussed in terms of fact, but molded while under the control of preconception, prejudice, false memory, confirmation bias, internal belief systems and more; thus there can be no valid synthesis, no reduction of dissonance, and in effect, it represents the end of all practical history.

History ends in a well of frustration among biased, eternally bickering minds.

And if you believe that, I want to sell you the Brooklyn Bridge.

Robb: Do your books sell? They are usually so different in fact and opinion than other books on the subject.

Michno: Certainly they sell, but “how many” is the question. None of them have been printed and promoted by the big New York publishers, which is where the publicity, sales, and money are to be found. So I rationalize: I would rather write about a few esoteric topics that interest me than do the same old stuff that has been done hundreds of times. Although I am guilty of writing about some of these topics, does anyone really need another book about Custer or the Little Big Horn?

I have discussed the public’s reading preferences with several agents and authors. The consensus seems to be that there are about one dozen western history topics/subjects that New York will print. They include Custer, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill, the Little Big Horn, the Alamo, and the like.

If the subject does not fall into one of those frameworks, it will not be a money-making proposition. New York knows that the American public has very limited interests and imagination. We like our traditional heroes and villains, who all belong to the mythic ideal of American exceptionalism, and we will seldom venture out into uncharted, uncomfortable territory.

The old myths have failed and faded, but New York still prints them—and will until a new mythology comes along.

Robb: It seems there is an ever enlarging strain of biased information against 19th century white settlers and the Army. Why is this?

Michno: We started seeing this change more than a half century ago, when cherished myths of American exceptionalism were being seriously questioned.

Michno: We started seeing this change more than a half century ago, when cherished myths of American exceptionalism were being seriously questioned.

The rumblings were in the civil rights and women’s rights movements, and the Viet Nam War protests. The military-industrial complex was seen as avaricious and evil. It was all a part of postmodernism, where universal, happy historical narratives were seen as unrealistic and only a tool of authority. Those who owned the discourse held the power.

When individual, minority, ethnic, and gender narratives proliferated, the Davy Crockett-John Wayne image was shattered. The “Spaghetti Westerns” were a product of the times—the good cowboy image was forever tarnished. Movies like Little Big Man or Soldier Blue, or books like Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee were part of the Zeitgeist. The white settlers and the army no longer wore the white hats.

It is all a part of the ongoing process of historical revision. History changes with the times. People re-write their history to serve their own purposes. It has been going on forever. Perhaps we were due for the change. Those white settlers and cavalrymen were heroes only to a specific segment of the population. Now, those once left out are having their turn. Perhaps it is a good thing.

The idea of American exceptionalism, of spreading Christianity and democracy all over the world may be best relegated to a distant past, because it is no longer relevant, or helpful. And it may make more enemies than friends.

Robb: Are you working on any new projects?

Michno: Yes. I recently finished Smoke over the Sangre de Cristo: Indian Depredation Claims and the Ute-Jicarilla War, 1849-1855. Oklahoma is currently reviewing it. Here, I found that a major reason for our Western Indian wars were the depredation claim sections in the various Trade and Intercourse Acts.

The fact that we allowed people to file claims against Indians with little proof required, and no penalties for false accusations, led to widespread fraud. Whites filed false claims, impelled the militia or army to investigate and chastise the marauders, innocent people were attacked, the inevitable retaliation ensued, and it snowballed into a progressive succession of conflicts.

Studying the claims and the investigations, I found scores of instances where the military searched for alleged culprits, only to find the reports extremely exaggerated or completely bogus. I found more than fifty officers’ reports that literally said that the claimants were liars.

False accusations actually led to war with the Jicarilla and Ute in New Mexico and Colorado during the period in question.

Understanding this underlying conflict between a skeptical military trying to keep the peace and avaricious frontiersmen wanting to make a dollar by fair means or foul, led to the start of another manuscript (title undecided) in which the army’s main adversary during the westward movement was not the Indian, but the frontier settler.

You see, we are constantly in a process of revision. Maybe Voltaire was right when he said: “History is a pack of lies we play on the dead.”

The post Greg Michno, Sand Creek and The End of History appeared first on .

December 18, 2015

The Captive Boy, Comanches and Me

The Captive Boy is now for sale at Amazon.

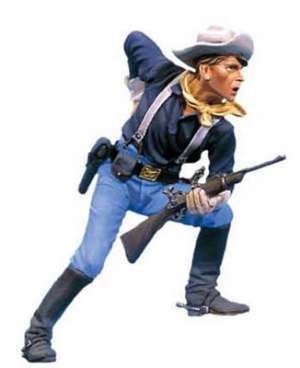

The Captive Boy is now for sale at Amazon. The novel begins when August Shiltz is recaptured by the Fourth U.S. Cavalry, after having been held captive by the Comanche since he was nine years old.

You can buy this book at Amazon, at http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B019HQO0GC?keywords=The%20Captive%20Boy&qid=1450466298&ref_=sr_1_6&sr=8-6

Chapter One

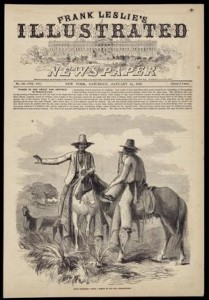

With the Fourth Cavalry in Texas: A Memoir of The Indian War, By Joseph Finley Grant, Reporter and Illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

I was sitting by Col. Theodore (Mac) McKenna’s desk when Privates Wilson and Smith dragged the kid through the door.

They wrestled him to a chair and held him down, trying to tie him up while he fought them, their hands  slipping on his greased up skin.

slipping on his greased up skin.

The kid wasn’t wearing clothes to speak of, just a breechclout barely covering his privates and deerskin leggings over his tattered moccasins.

Wood smoke, hot sweat and buffalo robe–which smells like mangy dog–radiated off the boy like heat off a campfire.

Breathing was difficult, even with the window open.

You usually smelled that particular combination of foul odors when parleying in some benighted Comanche lodge.

Finally, Major Sam Brennan and Sergeant-Major Pruitt helped, and the four of them managed to grab the boy by the shoulders and hold him down in the chair.

Even then, the kid thought his name was Eka Papi Tuinupu, or red-headed boy; but he was really August Shiltz, son of kraut-eating immigrants who were farming near Fredericksburg when they were murdered and their son taken.

A neighbor (if you can call someone who lives fifteen miles away a neighbor) took some food to the family, as the Shiltz’s were hard-luck people, and found everyone except August lying in front of the smoking cabin.

A neighbor (if you can call someone who lives fifteen miles away a neighbor) took some food to the family, as the Shiltz’s were hard-luck people, and found everyone except August lying in front of the smoking cabin.

Their naked bodies were white in the sun, scalped, mutilated, the woman and girls’ raped–which was what the savages always did.

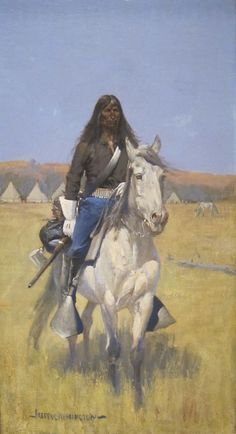

I never understood how the army spotted August during the raid on the Comanche village, as it was easy to mistake him for a Quahadi (what this band of Comanches call themselves, antelope people).

Sun had darkened his skin and his red braids were black with dirt and grease.

Only a close look revealed the Teutonic face; his long nose and long jaws below sharp cheekbones, the thin lips and narrow, defiant blue eyes.

Also, at sixteen, he was already taller and heavier than most fully-grown Comanche warriors.

On horseback, the Comanches were magnificent, but standing on level ground with the rest of us they usually failed to exceed five feet six inches tall, much like jockeys one sees at Saratoga, and their bowed legs made them appear even shorter.

August was already four or five inches taller than most of his compatriots.

I’ve been to the university at Heidelberg and seen students dueling–their facial scars are marks of honor and proof of their dubious manhood–and August looked just like them; minus the scars.

As soon as the men dragged August into Mac’s office, I snatched my sketching pencils from my pocket and went to work.

I still have that sketch, which came in handy a few years later when I wrote about the war: August, perching on the chair like a bound hawk, his eyes slit in rage and fear.

Colonel McKenna watched the boy, his hands folded on his desk, light from the window shining on his

blue cavalry uniform, glinting off the silver eagles sitting on his shoulders.

Army command sent McKenna to Fort Richards eight months previously to command the Fourth Cavalry. He fought in the War of the Rebellion and was a decorated war veteran, wounded six times and brevetted seven times on the field, climbing from second lieutenant to colonel to brevet major general: Not even George Custer was promoted that rapidly.

Brevet means holding a rank without being given that rank’s responsibilities and pay; which was a way to reward good officers without actually doing anything for them.

Mac was a handsome man. He had long, thin jaws, a full, well-curved mouth and a square chin. But he also had a perpetual squint around his blue eyes, as if his head hurt.

Although he looked calm that day, Mac McKenna was probably not calm all the way through.

Sometimes Mac’s hands shook, like he vibrated inside, though he carried himself like an iron rod on parade. He had a pleasant tenor voice, but it was controlled, as if his feelings were in the guardhouse and he had thrown the key away.

His men were in terror of him, and for excellent reasons.

“Are you August Shiltz?” Mac asked.

No reaction.

Mac said to Ben Washington, the black Seminole scout standing by his desk, “Tell August if he stops struggling he will not be restrained.”

Now here’s something odd. When Ben first came in, the kid straightened to attention and said something urgent in Comanche.

I assumed they knew each other.

Ben answered him, and the kid looked confused.

Then Ben mumbled something else to the boy, pushing Comanche words out of his chest like rocks, and August quieted.

You would never mistake Ben for a soldier, or for a regular Seminole, for that matter. The Black-Seminoles were descended from runaway slaves who took refuge with the Seminoles in Florida and sometimes intermarried.

You would never mistake Ben for a soldier, or for a regular Seminole, for that matter. The Black-Seminoles were descended from runaway slaves who took refuge with the Seminoles in Florida and sometimes intermarried.

Ben was typical of that ilk. Kinky hair fell to his shoulders but his skin was lighter than his slave ancestors. And he had slim lips and Indian cheekbones perching under his eyes like iron bars.

Ben would have been nice-looking, for a half-breed, but a round scar on his face puckered his left cheek and I suspect some teeth were missing. Obviously shot from his mouth.

Mac sat with his hands clasped on his desk, staring at the kid.

That was another thing about Mac, he didn’t exude warmth or empathy. Cross him in any way and you would live to regret it.

“You have been identified as August Shiltz, taken from your father’s farm when you were nine years old,” Mac said, waiting while Ben translated.

August looked coiled to pounce.

“The raiders killed your parents and your sisters. Do you have other family here in Texas?”

Silence.

“How much English do you remember?”

Silence.

I pulled out my notebook and writing pencil.

This might make two columns in the newspaper: White Child Rescued From Savages. Years of Brutal  Captivity.

Captivity.

I usually wrote about the joyous reunions though the joyous reunions were usually on the relatives’ side.

If captives lived with a tribe more than five years, once we got them back they didn’t remember their own mothers, assuming those mothers escaped being raped to death in the raid.

Assuming anyone survived.

Assuming the captive was adopted into the tribe.

If you were a woman and not adopted, life was a hell of sexual slavery and endless toil.

Sometimes returned captives became good white citizens: A few pined away until they died, longing for God knows who or what.

“Ask the boy if he remembers his white name or his family,” Mac said.

After Ben translated, August sneered and rattled back.

“He says he is Comanche, not white,” Ben said, his expression unchanged.

Mac wasn’t surprised. None of us were. That’s what captive kids usually said.

“Tell him the raiders who killed his family captured him on December 25, 1864.”

“Tell him the raiders who killed his family captured him on December 25, 1864.”

August shook his head, his face indifferent.

“Tell him the squaws we took in the raid confirm he was a captive.”

August shook his head.

“Ask him to explain his eye color.”

“Tabernacle my father,” August said, blurting the words in English.

That was startling, as we believed the boy had forgotten his English.

Mac leaned back in his chair, contemplating the kid and snapping his stumps, the three partially amputated fingers on his left hand. Everything was gone below the first joints, thanks to rebel artillery.

The men called the colonel, among other things, “Three-finger Jack.”

They also referred to him as “hard ass,” and they weren’t joking.

While McKenna pondered, the kid jumped from his chair and dove for the open window behind Mac’s desk.

A flash and he was almost gone, but Mac threw himself at the kid and caught his leg, then the troopers grabbed the other leg and they pulled him back inside.

“Tie him to the chair,” Mac told his men, and one of them reached for a lariat and wrapped it around the boy until he couldn’t move.

August’ eyes were wide, his pupils dilated until they looked black.

“Do you remember if your family got mail, letters?” Mac asked, as if nothing had happened.

“Tabernacle my father.”

“I can’t allow you to run back to the Comanches.”

“I want.”

Mac shook his head, glancing at Sam Brennan: “Remind me Major. Where did the Comanche capture this boy?”

Sam glanced at Mac, his eyes brimming with good-humored interest at the situation (as he viewed most situations), and said, “His parents were farming beyond the safe line sir, twenty miles west of Fredericksburg. We believe the Comanche fired the family’s cabin and then killed them when they ran outside.”

Sam glanced at Mac, his eyes brimming with good-humored interest at the situation (as he viewed most situations), and said, “His parents were farming beyond the safe line sir, twenty miles west of Fredericksburg. We believe the Comanche fired the family’s cabin and then killed them when they ran outside.”

“No reported sightings until now?”

“No sir.”

“Do you have relatives in Germany,” Mac asked the boy.

Silence.

Mac turned to Ben and said, “Explain Germany to him, that it’s a country across a big body of water, tell him that’s where his parents came from.”

Ben translated.

“I Quahadi,” August said.

“Major, what would you do with August, had you the decision?” Mac asked Sam.

“Send him to the reserve Sir.”

“He’s not a Comanche.”

“Find a foster family.”

“He would run the first day.”

“That would be his decision. He’s a big boy.”

“We don’t need another fighting Comanche.”

You could watch Mac’s eyes and see him thinking, planning, and you would never mistake the colonel for anyone else. Nothing escaped his attention.

McKenna snapped out orders and woe was the trooper who failed to muck out a stall or neglect his weapons.

Woe to the officers who did not turn in reports, or did not properly drill men, or allowed his troopers to sleep in the saddle on a long patrol.

Patrols could last months, and troopers could ride thirty-six hours straight when they were on the hunt. You couldn’t let them sleep or they would fall behind the column.

By the time they were found, they were usually dead.

A trooper went to sleep on patrol a few months previously and fell out of his saddle.

Back at Richards, Mac ordered the man spread-eagled on an artillery cartwheel, and then left that poor trooper on the wheel until the bugle blew retreat.

The kid stared at Mac’s hair, and Mac watched the kid stare at his hair.

Mac had the kind of brown hair that has red glints in it, and those glints shone in the sunlight pouring in the window behind him.

“Pruitt, do you remember those troopers I sent to the guardhouse?” Mac asked the sergeant major, an older man whose stomach stuck out in front of him, though hardly more than mine, I venture to guess.

“Pruitt, do you remember those troopers I sent to the guardhouse?” Mac asked the sergeant major, an older man whose stomach stuck out in front of him, though hardly more than mine, I venture to guess.

“Which ones?”

“They were drunk in the barracks and peed in the wood stove.”

“Yes sir, Privates Johnny O’Donovan and Abner Bullis.”

“What is their sentence?”

“Two weeks, then kitchen duty until discharge.”

“Release and reassign. I want them to guard our young man wherever he goes. And he is forbidden to walk off post. And tell the troopers if August escapes, they will carry a log chained to their shoulders until I say otherwise.”

“Sir, not O’Donovan, I need him for my team. Please, sir.”

Pruitt loved his baseball team.

If McKenna had a favorite besides Sam Brennan, it was Pruitt. Both served under him in the war, and he needed both of them to run the garrison.

“Very well, release O’Donovan, assign Bullis and any other trooper to our young man, and find two Sunday reliefs.”

“Where will we quarter him?” Sam asked.

“Put him in the room next to mine, at my quarters. Put a cot in there. Board up the window and order Bullis to sleep immediately outside the door.”

Sam looked amazed.

The boy understood. He jerked the chair, it toppled over, and his nose slammed against the splintered wood floor.

Sam and the troopers lifted him the chair and blood ran from the kid’s nose to his neck and chest, like the river of blood yet to come.

“Major, wipe his nose,” Mac told Sam.

Sam took off his neckerchief and swiped the kid’s face, but blood trickled down his lips.

The kid sucked the blood into his mouth, leaned as far forward as the lariat permitted and spit blood at Mac.

“I Quahadi,” the kid said, his nose and mouth running with blood.

Mac did not flinch, though blood splattered his desk.

After a moment, Mac said, “And Major, enroll August in the post school. I want him bathed and clothed like a white boy. I want him eating at the enlisted men’s mess.”

The troopers dragged August from the office, and everyone else filed from Mac’s office except me.

Nobody noticed me. They had no idea what an Eastern newspaper could do to them.

I sat looking out the window, wondering what kind of story to write.

It was April, the rainy season had lingered and the prairie was green.

Richards sat on a rise where the wind was always moving, and you could see up to a mile.

Cottonwood trees dotting the creek were leafed out, their heart-shaped leaves shining in the sun, and I could see miles of prairie flowers beyond the thin curve of green water.

Cottonwood trees dotting the creek were leafed out, their heart-shaped leaves shining in the sun, and I could see miles of prairie flowers beyond the thin curve of green water.

Looking for anything else of beauty was futile.

Even the post buildings were crude; frame buildings so frail the wind shook them and sent never-ending dust through cracks in the warped boards; picket huts made from long cottonwood sticks, mud packed between the sticks, with sod roofs sprouting grass each spring; framed-up tents that snapped in the wind, threatening to fly away; adobe storehouses and shops.

One unfortunate second lieutenant and his wife (just transferred from the east, and what must they have thought of Richards) were forced to live in a converted chicken coop until another officer vacated his quarters.

That’s true and not in the least hyperbole.

I assure you, there was nothing decent to live or work in.

Picket buildings crawled with scorpions, spiders and snakes. Scorpions and dirt fell from the ceiling. Nasty places.

The only real building was the two-story stone hospital.

It wasn’t long before Mac appeared outside, playing with his pet buffalo calf.

I turned a new page in my sketchbook and began to draw the colonel and the calf. A few strokes and there he was, a slight man, severely underweight due to his war wounds, taller than the calf but a lot thinner.

At two months, the calf weighed at least two hundred pounds.

At the colonel’s orders, one of the troopers was keeping the orphan alive by feeding it some kind of mash.

The calf butted its woolly head on Mac’s shoulder, and Mac staggered backward.

As far as I could tell, Mac was attached to the beast.

McKenna rubbed the calf’s head and reached in his pocket, pulled something out and fed it to the buffalo, then walked toward his quarters.

The post The Captive Boy, Comanches and Me appeared first on .

The Captive Boy and Me

The Captive Boy is now for sale at Amazon.

The Captive Boy is now for sale at Amazon. The novel begins when August Shiltz is recaptured by the Fourth U.S. Cavalry, after having been held captive by the Comanche since he was nine years old.

You can buy this book at Amazon, at http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B019HQO0GC?keywords=The%20Captive%20Boy&qid=1450466298&ref_=sr_1_6&sr=8-6

Chapter One

With the Fourth Cavalry in Texas: A Memoir of The Indian War, By Joseph Finley Grant, Reporter and Illustrator for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

I was sitting by Col. Theodore (Mac) McKenna’s desk when Privates Wilson and Smith dragged the kid through the door.

They wrestled him to a chair and held him down, trying to tie him up while he fought them, their hands  slipping on his greased up skin.

slipping on his greased up skin.

The kid wasn’t wearing clothes to speak of, just a breechclout barely covering his privates and deerskin leggings over his tattered moccasins.

Wood smoke, hot sweat and buffalo robe–which smells like mangy dog–radiated off the boy like heat off a campfire.

Breathing was difficult, even with the window open.

You usually smelled that particular combination of foul odors when parleying in some benighted Comanche lodge.

Finally, Major Sam Brennan and Sergeant-Major Pruitt helped, and the four of them managed to grab the boy by the shoulders and hold him down in the chair.

Even then, the kid thought his name was Eka Papi Tuinupu, or red-headed boy; but he was really August Shiltz, son of kraut-eating immigrants who were farming near Fredericksburg when they were murdered and their son taken.

A neighbor (if you can call someone who lives fifteen miles away a neighbor) took some food to the family, as the Shiltz’s were hard-luck people, and found everyone except August lying in front of the smoking cabin.

A neighbor (if you can call someone who lives fifteen miles away a neighbor) took some food to the family, as the Shiltz’s were hard-luck people, and found everyone except August lying in front of the smoking cabin.

Their naked bodies were white in the sun, scalped, mutilated, the woman and girls’ raped–which was what the savages always did.

I never understood how the army spotted August during the raid on the Comanche village, as it was easy to mistake him for a Quahadi (what this band of Comanches call themselves, antelope people).

Sun had darkened his skin and his red braids were black with dirt and grease.

Only a close look revealed the Teutonic face; his long nose and long jaws below sharp cheekbones, the thin lips and narrow, defiant blue eyes.

Also, at sixteen, he was already taller and heavier than most fully-grown Comanche warriors.

On horseback, the Comanches were magnificent, but standing on level ground with the rest of us they usually failed to exceed five feet six inches tall, much like jockeys one sees at Saratoga, and their bowed legs made them appear even shorter.

August was already four or five inches taller than most of his compatriots.

I’ve been to the university at Heidelberg and seen students dueling–their facial scars are marks of honor and proof of their dubious manhood–and August looked just like them; minus the scars.

As soon as the men dragged August into Mac’s office, I snatched my sketching pencils from my pocket and went to work.

I still have that sketch, which came in handy a few years later when I wrote about the war: August, perching on the chair like a bound hawk, his eyes slit in rage and fear.

Colonel McKenna watched the boy, his hands folded on his desk, light from the window shining on his

blue cavalry uniform, glinting off the silver eagles sitting on his shoulders.

Army command sent McKenna to Fort Richards eight months previously to command the Fourth Cavalry. He fought in the War of the Rebellion and was a decorated war veteran, wounded six times and brevetted seven times on the field, climbing from second lieutenant to colonel to brevet major general: Not even George Custer was promoted that rapidly.

Brevet means holding a rank without being given that rank’s responsibilities and pay; which was a way to reward good officers without actually doing anything for them.

Mac was a handsome man. He had long, thin jaws, a full, well-curved mouth and a square chin. But he also had a perpetual squint around his blue eyes, as if his head hurt.

Although he looked calm that day, Mac McKenna was probably not calm all the way through.

Sometimes Mac’s hands shook, like he vibrated inside, though he carried himself like an iron rod on parade. He had a pleasant tenor voice, but it was controlled, as if his feelings were in the guardhouse and he had thrown the key away.

His men were in terror of him, and for excellent reasons.

“Are you August Shiltz?” Mac asked.

No reaction.

Mac said to Ben Washington, the black Seminole scout standing by his desk, “Tell August if he stops struggling he will not be restrained.”

Now here’s something odd. When Ben first came in, the kid straightened to attention and said something urgent in Comanche.

I assumed they knew each other.

Ben answered him, and the kid looked confused.

Then Ben mumbled something else to the boy, pushing Comanche words out of his chest like rocks, and August quieted.

You would never mistake Ben for a soldier, or for a regular Seminole, for that matter. The Black-Seminoles were descended from runaway slaves who took refuge with the Seminoles in Florida and sometimes intermarried.

You would never mistake Ben for a soldier, or for a regular Seminole, for that matter. The Black-Seminoles were descended from runaway slaves who took refuge with the Seminoles in Florida and sometimes intermarried.

Ben was typical of that ilk. Kinky hair fell to his shoulders but his skin was lighter than his slave ancestors. And he had slim lips and Indian cheekbones perching under his eyes like iron bars.

Ben would have been nice-looking, for a half-breed, but a round scar on his face puckered his left cheek and I suspect some teeth were missing. Obviously shot from his mouth.

Mac sat with his hands clasped on his desk, staring at the kid.

That was another thing about Mac, he didn’t exude warmth or empathy. Cross him in any way and you would live to regret it.

“You have been identified as August Shiltz, taken from your father’s farm when you were nine years old,” Mac said, waiting while Ben translated.

August looked coiled to pounce.

“The raiders killed your parents and your sisters. Do you have other family here in Texas?”

Silence.

“How much English do you remember?”

Silence.

I pulled out my notebook and writing pencil.

This might make two columns in the newspaper: White Child Rescued From Savages. Years of Brutal  Captivity.

Captivity.

I usually wrote about the joyous reunions though the joyous reunions were usually on the relatives’ side.

If captives lived with a tribe more than five years, once we got them back they didn’t remember their own mothers, assuming those mothers escaped being raped to death in the raid.

Assuming anyone survived.

Assuming the captive was adopted into the tribe.

If you were a woman and not adopted, life was a hell of sexual slavery and endless toil.

Sometimes returned captives became good white citizens: A few pined away until they died, longing for God knows who or what.

“Ask the boy if he remembers his white name or his family,” Mac said.

After Ben translated, August sneered and rattled back.

“He says he is Comanche, not white,” Ben said, his expression unchanged.

Mac wasn’t surprised. None of us were. That’s what captive kids usually said.

“Tell him the raiders who killed his family captured him on December 25, 1864.”

“Tell him the raiders who killed his family captured him on December 25, 1864.”

August shook his head, his face indifferent.

“Tell him the squaws we took in the raid confirm he was a captive.”

August shook his head.

“Ask him to explain his eye color.”

“Tabernacle my father,” August said, blurting the words in English.

That was startling, as we believed the boy had forgotten his English.

Mac leaned back in his chair, contemplating the kid and snapping his stumps, the three partially amputated fingers on his left hand. Everything was gone below the first joints, thanks to rebel artillery.

The men called the colonel, among other things, “Three-finger Jack.”

They also referred to him as “hard ass,” and they weren’t joking.

While McKenna pondered, the kid jumped from his chair and dove for the open window behind Mac’s desk.

A flash and he was almost gone, but Mac threw himself at the kid and caught his leg, then the troopers grabbed the other leg and they pulled him back inside.

“Tie him to the chair,” Mac told his men, and one of them reached for a lariat and wrapped it around the boy until he couldn’t move.

August’ eyes were wide, his pupils dilated until they looked black.

“Do you remember if your family got mail, letters?” Mac asked, as if nothing had happened.

“Tabernacle my father.”

“I can’t allow you to run back to the Comanches.”

“I want.”

Mac shook his head, glancing at Sam Brennan: “Remind me Major. Where did the Comanche capture this boy?”

Sam glanced at Mac, his eyes brimming with good-humored interest at the situation (as he viewed most situations), and said, “His parents were farming beyond the safe line sir, twenty miles west of Fredericksburg. We believe the Comanche fired the family’s cabin and then killed them when they ran outside.”

Sam glanced at Mac, his eyes brimming with good-humored interest at the situation (as he viewed most situations), and said, “His parents were farming beyond the safe line sir, twenty miles west of Fredericksburg. We believe the Comanche fired the family’s cabin and then killed them when they ran outside.”

“No reported sightings until now?”

“No sir.”

“Do you have relatives in Germany,” Mac asked the boy.

Silence.

Mac turned to Ben and said, “Explain Germany to him, that it’s a country across a big body of water, tell him that’s where his parents came from.”

Ben translated.

“I Quahadi,” August said.

“Major, what would you do with August, had you the decision?” Mac asked Sam.

“Send him to the reserve Sir.”

“He’s not a Comanche.”

“Find a foster family.”

“He would run the first day.”

“That would be his decision. He’s a big boy.”

“We don’t need another fighting Comanche.”

You could watch Mac’s eyes and see him thinking, planning, and you would never mistake the colonel for anyone else. Nothing escaped his attention.

McKenna snapped out orders and woe was the trooper who failed to muck out a stall or neglect his weapons.

Woe to the officers who did not turn in reports, or did not properly drill men, or allowed his troopers to sleep in the saddle on a long patrol.

Patrols could last months, and troopers could ride thirty-six hours straight when they were on the hunt. You couldn’t let them sleep or they would fall behind the column.

By the time they were found, they were usually dead.

A trooper went to sleep on patrol a few months previously and fell out of his saddle.

Back at Richards, Mac ordered the man spread-eagled on an artillery cartwheel, and then left that poor trooper on the wheel until the bugle blew retreat.

The kid stared at Mac’s hair, and Mac watched the kid stare at his hair.

Mac had the kind of brown hair that has red glints in it, and those glints shone in the sunlight pouring in the window behind him.

“Pruitt, do you remember those troopers I sent to the guardhouse?” Mac asked the sergeant major, an older man whose stomach stuck out in front of him, though hardly more than mine, I venture to guess.

“Pruitt, do you remember those troopers I sent to the guardhouse?” Mac asked the sergeant major, an older man whose stomach stuck out in front of him, though hardly more than mine, I venture to guess.

“Which ones?”

“They were drunk in the barracks and peed in the wood stove.”

“Yes sir, Privates Johnny O’Donovan and Abner Bullis.”

“What is their sentence?”

“Two weeks, then kitchen duty until discharge.”

“Release and reassign. I want them to guard our young man wherever he goes. And he is forbidden to walk off post. And tell the troopers if August escapes, they will carry a log chained to their shoulders until I say otherwise.”

“Sir, not O’Donovan, I need him for my team. Please, sir.”

Pruitt loved his baseball team.

If McKenna had a favorite besides Sam Brennan, it was Pruitt. Both served under him in the war, and he needed both of them to run the garrison.

“Very well, release O’Donovan, assign Bullis and any other trooper to our young man, and find two Sunday reliefs.”

“Where will we quarter him?” Sam asked.

“Put him in the room next to mine, at my quarters. Put a cot in there. Board up the window and order Bullis to sleep immediately outside the door.”

Sam looked amazed.

The boy understood. He jerked the chair, it toppled over, and his nose slammed against the splintered wood floor.

Sam and the troopers lifted him the chair and blood ran from the kid’s nose to his neck and chest, like the river of blood yet to come.

“Major, wipe his nose,” Mac told Sam.

Sam took off his neckerchief and swiped the kid’s face, but blood trickled down his lips.

The kid sucked the blood into his mouth, leaned as far forward as the lariat permitted and spit blood at Mac.

“I Quahadi,” the kid said, his nose and mouth running with blood.

Mac did not flinch, though blood splattered his desk.

After a moment, Mac said, “And Major, enroll August in the post school. I want him bathed and clothed like a white boy. I want him eating at the enlisted men’s mess.”

The troopers dragged August from the office, and everyone else filed from Mac’s office except me.

Nobody noticed me. They had no idea what an Eastern newspaper could do to them.

I sat looking out the window, wondering what kind of story to write.

It was April, the rainy season had lingered and the prairie was green.

Richards sat on a rise where the wind was always moving, and you could see up to a mile.

Cottonwood trees dotting the creek were leafed out, their heart-shaped leaves shining in the sun, and I could see miles of prairie flowers beyond the thin curve of green water.

Cottonwood trees dotting the creek were leafed out, their heart-shaped leaves shining in the sun, and I could see miles of prairie flowers beyond the thin curve of green water.

Looking for anything else of beauty was futile.

Even the post buildings were crude; frame buildings so frail the wind shook them and sent never-ending dust through cracks in the warped boards; picket huts made from long cottonwood sticks, mud packed between the sticks, with sod roofs sprouting grass each spring; framed-up tents that snapped in the wind, threatening to fly away; adobe storehouses and shops.

One unfortunate second lieutenant and his wife (just transferred from the east, and what must they have thought of Richards) were forced to live in a converted chicken coop until another officer vacated his quarters.

That’s true and not in the least hyperbole.

I assure you, there was nothing decent to live or work in.

Picket buildings crawled with scorpions, spiders and snakes. Scorpions and dirt fell from the ceiling. Nasty places.

The only real building was the two-story stone hospital.

It wasn’t long before Mac appeared outside, playing with his pet buffalo calf.

I turned a new page in my sketchbook and began to draw the colonel and the calf. A few strokes and there he was, a slight man, severely underweight due to his war wounds, taller than the calf but a lot thinner.

At two months, the calf weighed at least two hundred pounds.

At the colonel’s orders, one of the troopers was keeping the orphan alive by feeding it some kind of mash.

The calf butted its woolly head on Mac’s shoulder, and Mac staggered backward.

As far as I could tell, Mac was attached to the beast.

McKenna rubbed the calf’s head and reached in his pocket, pulled something out and fed it to the buffalo, then walked toward his quarters.

The post The Captive Boy and Me appeared first on .

December 9, 2015

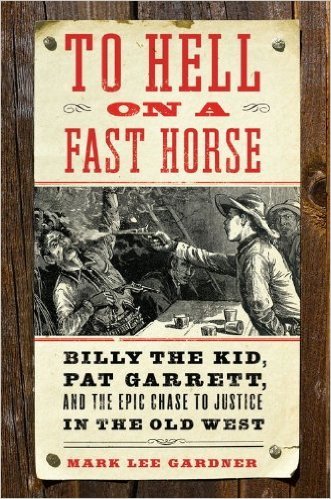

Billy The Kid–To Hell on a Fast Horse

True West magazine named Mark “Best Author” in its annual “Best of the West” issue for 2014.

Moreover, Mark is an award-winning performer of 19th and early 20th-century western music.

Mark’s latest CD is Outlaws: Songs of Robbers, Rustlers, and Rogues,which includes ballads such as “Cole Younger,” “Jesse James,” “Billy the Kid,” and “Sam Bass.”

Question: Mark, when I read To Hell on a Fast Horse I was amazed to find so many facts about Billy that I’ve never seen before, and I thought I knew everything. How did you unearth this much information?

For instance, that Billy had a brother and he visited that brother before he was killed, and that Billy was armed the night he was killed?

Mark Gardner: Mostly it was your traditional “digging” in manuscript archives in various states, from Texas to Utah. I also benefited from amateur and professional historians who have been studying the Kid for decades. Some of these scholars’ vast research collections have ended up in public institutions.

A good example is Leon Metz, who wrote an excellent biography of Pat Garrett in the early 70s. Leon donated all of his papers to the University of Texas at El Paso Library. Making use of his research saved me countless hours of work.

Bob Utley graciously gave me copies of all his research notes on Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War, which also saved me considerable time.

Additionally, I made use of recent technology that has not been previously available to those studying the Kid. I’m referring specifically to the millions of pages of digitized nineteenth-century newspapers that can be accessed online.

Q: Why did you write the book?

Gardner: I wanted to write a book on a western subject that would appeal to a New York publisher. I was fascinated by Pat Garrett’s story and believed I could turn out a fresh biography, but my literary agent suggested I do a dual biography of Garrett and the Kid. It was an excellent suggestion, for the two men are forever linked in history and legend.

Q: Why does Garrett’s story fascinate you?

Q: Why does Garrett’s story fascinate you?

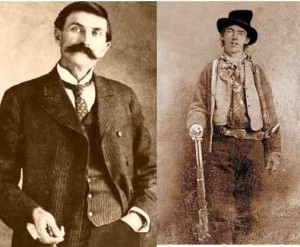

Gardner: Because he is the more tragic figure of the two. He was a hero throughout the territory after he killed Billy, but as the Kid’s legend grew, Garrett slowly became the villain of the story, a true travesty.

The controversy surrounding Garrett’s 1908 murder near Las Cruces also fascinated me (he was shot in the back of the head while urinating). No one believes that Wayne Brazel, the man tried for killing Garrett, committed the deed. But as for who did, we’re still debating it.

Q: Most authors have assumed the old legend of Pat and Billy once being close friends (or at least buddies) is true, but you discount that. Why?

Gardner: Primarily because Garrett denied they were friends. And I was suspicious of those who said they were bosom buddies. It seemed that the claim of a friendship might have been an attempt to demonize Garrett, make him more of the bad guy: he had turned on his friend and shot him down in the dark. It does make a good story.

(In another interview, Gardner said James E. Sligh, a White Oaks newspaper editor, who came from the same Louisiana parish as Garrett, claimed Garrett told him that while he knew the Kid well, they were neither friends nor enemies: “He minds his business, and I attend to mine.”)

The Arrest of Billy the Kid, by Thom Ross

Q: Many people, including me, have assumed Pat Garrett was a bad man, or at least uncaring and merciless. But you have unearthed a different Pat. He seemed like a good guy. Is that what you think?

Gardner: I do think he was a good guy. That doesn’t mean he didn’t have flaws. He certainly did – we all do. But he deserves tremendous credit for taking on a very dangerous job in becoming sheriff of Lincoln County and hunting down the Kid, something no one else in the territory was willing to do.

Garrett with Apolonaria, his second wife, in 1880

I also look at his family life and see a very loving and caring father and husband. His children absolutely adored him.

Q: Robert Utley told me he didn’t believe Billy was a good person. What do you think?

Gardner: I guess I’m more sympathetic toward the Kid than Bob. Billy lived in a very dangerous place and time. It was sometimes kill or be killed.

It should be pointed out, too, that he was well liked by the native New Mexicans, and we know there were several young ladies, including Paulita Maxwell, who were quite fond of him. He must have had some good in him.

Paulita Maxwell, according to The Ruidoso News. Paulita was Billy’s girlfriend.

Q: I have thought about Billy a lot, and have concluded he was an orphan who had no father to guide him or protect him, so he became rough out of need and vulnerability. What do you think?

Gardner: I think that’s absolutely correct. After his mother’s death, he was on his own and did what he could to get by. If he’d had a stable home life, I don’t believe we’d be talking about a young New Mexico outlaw named Billy the Kid.

Q: Did Billy stay in Lincoln after the Lincoln County War, and after he became a wanted man, because he (unconsciously perhaps) believed it was his home? What do you think? Did his decision make sense?

Gardner: He had at least one sweetheart at Fort Sumner, and he had lots of friends in that area, especially among the Hispanic population. I think Billy felt he was safe there, but I also think that because he had outsmarted New Mexico’s lawmen so many times before, he didn’t believe there was anybody who could get him.

Q: Do you believe the most recent (purported) Billy photo, taken when he and friends were playing croquet, is authentic?

Gardner: It’s indeed a genuine tintype from the nineteenth century, but it’s not Billy and the Regulators.

The February 2016 issue of True West magazine will have a ten-page section devoted to the controversy surrounding the tintype. All the problems historians have with the image are explained in detail. I suggest your readers check it out.

Q: Do you believe Billy actually advised someone (forgotten who) not to begin killing?

Gardner: He told a newspaper reporter for the Mesilla News in 1881, “Advise persons never to engage in killing.”

Q: Did he really do a jig on the courthouse balcony in Lincoln (after he killed Olinger and the deputy) before he galloped out of Lincoln?

Billy Disguised as a Sheepherder, by Bob Boze Bell

Billy Disguised as a Sheepherder, by Bob Boze BellGardner: That’s what Garrett claims in his 1882 biography of Billy.

Q: Why couldn’t Pat Garrett find a steady place for himself? He seemed to go from one career to another.

Gardner: I don’t know that we’ll ever know the answer to that. I think he encountered some hard luck, a lot of which he brought on himself.

Garrett had a nice federal job as collector of customs at El Paso, Texas, an appointment from President Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1905, Roosevelt was visiting San Antonio for a reunion of his Rough Riders. Garrett was there and brought along a buddy of his, Tom Powers, who owned an El Paso saloon and gambling establishment.

Garrett lied to Roosevelt about Powers, telling the president that Powers was a cattleman. A group photograph was taken with the president that included Garrett and Powers.

Roosevelt found out later about Powers’ reputation as a professional gambler and was quite upset that Garrett had deceived him. When Garrett’s four-year term as collector came to an end eight months later, Roosevelt chose not to reappoint him.

Garrett probably should have remained a lawman – he really excelled at it – but there wasn’t a lot of money to be made in that line of work.

The Arrest of The Kid, by Thom Ross

Q: I believe Billy was destined to become a legend. I can’t explain that. What do you believe?

Gardner: I guess it’s easy for us to look back now and say that, but I don’t think any of his contemporaries saw that coming. They didn’t have the faintest notion their buddy, William Bonney, would become a legend or folk hero.

Q: Billy has always impressed me as being a person who was a lot brighter than the people around him. What do you think?

Gardner: He was brighter in some ways, and one of those ways was in making the people around him think they were brighter! And it got some of them killed.

Q: What are you working on?

Gardner: I’m just putting the finishing touches on a book on Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders for William Morrow/HarperCollins. It’s scheduled to be released on May 10.

Mark (on the right) and Rex Rideout

(Featured image is Pat Garrett – The Making of a Legend* by Don Crowley)

The post Billy The Kid–To Hell on a Fast Horse appeared first on .

November 16, 2015

Comanches and The Captive Boy

Many of the settlers were hard-scrabble poor, spoke no English and had no clue how to farm or ranch, or even how to build a cabin.

They also had no idea Comanche raiders could swoop down on them, murder the grown males, rape the women (and often carry them off to sexual slavery) and carry off many of the children; leaving everything in flames.

Those children were called The Captives.

Most of the children were adopted into the tribe and grew up on the Plains’ vast distances, believing themselves Comanche.

Many times, the captives were never heard from again.

But not always.

The U.S. Army recaptured many captive children, or the Indians themselves brought them to Army posts to trade for Indian captives, or because warriors wanted to take military pressure off their tribe.

That’s what happened to August Shiltz. When he was nine-years-old the Comanche murdered his drunk of a father and raped and killed his sisters and mother.

Tabernacle, a Comanche leader, adopted August, calling him Eka Papi Tuinupu, or Red-headed Boy.

August was Tabernacle’s son until he was sixteen.

Then Col. Mac McKenna’s Fourth Cavalry raided a Comanche village and discovered a white boy: August.

If you want to know what happened after that, you either have to wait a month or so until the novel is published, or you can read the first three chapters and a description of some of the remainder of The Captive Boy by visiting https://kindlescout.amazon.com/p/7378....

The Captive Boy is in the Amazon Scout program, which means if I get enough votes, or nominations, Amazon will offer me a publishing contract.

I can self-publish on Amazon, no matter what, but if Amazon offers me a contract, the company will also promote me and pay me hard cash.

I can live with that.

And I can hardly wait for this issue to be resolved because I have another novel in mind and am itching to write it. This one is also set in the nineteenth century (as most of mine are).

You can contact me with the form on this website, or visit Author: Julia Robb (on Facebook) or just friend me on Facebook.

I also have a Pinterest board titled “Good Books.”

Or, if you have a taste for novels about frontier America, you can read Scalp Mountain, which I published in 2012, or Del Norte, which I published in 2013.

by Michael Goettee

The post Comanches and The Captive Boy appeared first on .

October 5, 2015

Mass Shooters Are Paranoid Schizophrenics

THIS INTERVIEW WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN JANUARY, BUT IN LIGHT OF OUR LATEST MASSACRE, (aka mass shooting) at Umpqua Community College in Oregan, I’m running it again .

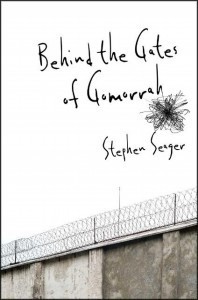

Dr. Stephen Seager’s memoir, Behind the Gates of Gomorrah: A Year with the Criminally Insane, may be the most important book published in the last ten years.

Seager, a psychiatrist at Napa State (forensic) Hospital, in California, has told America two things it very much needs to know.

One: Mass shooters are primarily paranoid schizophrenics .

Two: Forensic hospitals house violent criminals, including serial killers and child molesters, and those patients are free to mingle with staffers and each other.

Therefore, forensic hospitals are the most dangerous places in this country, both to patients and staffers.

Gomorrah is also a fantastical, almost surreal book that I found hard to put down, rubbing my eyes at 3 a.m.

Stephen Seager

Seager has changed names to protect privacy.

Dr. Seager, thank you for the interview.

Q. You began the book with the character you called Boudreaux (who was hospitalized after walking into the place he worked and gunning down his former co-workers) cornering you and threatening to kill you, calling you a “bloodsucker.”

Then when you briefly talked to him, he snapped back to sanity. He said he had killed his closest friends, and “What kind of a man does that?”

How can the insane snap back to sanity so fast? How does it happen?

A. As it turned out later, Boudreaux suffered from what’s called a “delirium” meaning he was actually medically ill. People who suffer from delirium frequently have florid symptoms of psychosis (think of DT’s – delirium tremens) when people withdraw from alcohol.

Dr. Richard Frishman, a psychiatrist at Napa State Hospital, photographed after he was attacked by a patient.

But delirium can be caused by many things – infections, drug intoxications and withdrawal just to name a few.

Another hallmark symptom of delirium is a rapid shifting from psychosis to normal, which proved to be the case with Boudreaux.

Q. The character you call McCoy is a career criminal, who killed somebody in the hospital. You say he isn’t mentally ill. Then he threatened to kill you because you testified against him in court, to keep him in the hospital.

Is McCoy still at Napa State?

A. Yes. But testifying against your patient and then having to care for them again is a frequent occurrence, certainly not limited to McCoy and I.

Testifying against a patient is the single most dangerous thing a psychiatrist at a state hospital can do.

Q. You say all forensic hospitals are full of violence, patients against staff, and patient against patient. How did the United States put itself in this position?

Napa State staffers, in 2011, protesting violence at the hospital, following the murder of psychiatric technician Donna Gross and the beating of rehabilitation therapist George Anderson

A. During the 1960’s, a series of court decisions seriously restricting the grounds for involuntary admission to a mental hospitals coincided with President Kennedy championing the 1963 “Community Mental Health Centers Act (CMHCA)” which easily passed congress.

The CMHCA was based on the premise that if mental illness could be attacked early and in the community, that chronic mental illness could be prevented and state mental hospitals would no longer be needed.

This sweeping change was not based on a single shred of scientific evidence and, tragically, has proven to be a total disaster.

Based on the wishful thinking of the CMHCA, state mental hospitals were essentially emptied.

The released patient’s got no better in the community – whether treated early or not – and became the homeless mentally ill that we so often see, sick and dying on the streets of American big cities today.

The released patient’s got no better in the community – whether treated early or not – and became the homeless mentally ill that we so often see, sick and dying on the streets of American big cities today.State mental hospitals with lots of empty beds (then) decided to take in “forensic” patients. Those people who had both committed crimes and were mentally ill.

Specifically to answer your question: few Americans actually care what happens to the mentally ill.

Whether these sick individuals are assaulted in state mental hospitals or whether they die on the streets, doesn’t seem to really much matter.

Napa State employees protesting violence at the hospital.

It’s been going on for decades: Did you know about it?

Q. Why have you stayed at Napa?

A. I stayed at Napa because my patients, who absorb most of the abuse and beatings, and the staff – mainly female nurses – really have no voice. No TV cameras, radios, newspapers, documentary film makers or anyone has ever been inside Napa State Hospital.

The BBC has tried. The New York Times has tried, 60 Minutes has tried, and they have all been stonewalled.

Forensic mental hospitals are shrouded in a conspiracy of silence.

My book gives my patients and staff at least one voice. If I had quit, my book would have been easily discounted. But since I’m still there, their voice is still there.

Jess Willard Massey, the Napa State Hospital patient who murdered psychiatric technician Donna Gross, is led out of Napa Superior Court following his 2011 sentencing. Massey was sentenced to 25 years to life.

Q. You say all mass shooters are (primarily) paranoid schizophrenics.

Why doesn’t everyone know about this and why hasn’t law enforcement done something about admitting all paranoid schizophrenics to a hospital?

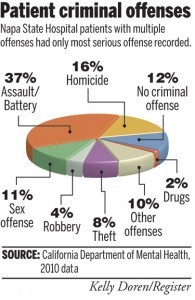

A. Here’s some figures: 1% of the population everywhere on earth is schizophrenic so in the US that’s 3.25 million people of which maybe 1 million or so are paranoid. There are 50,000 state hospital beds nationally.

The real question is why aren’t they in mandatory out patient treatment?

People know about mass shooters and they know about mental illness but nothing is ever done, which you have noticed. If you figure out why that is, please let me know.

When I said that people don’t care about the mentally ill, I wasn’t kidding.

Q. Is the U.S. more concerned about individual rights than mass murder? Why?

Sandy Hook Elementary, Newtown, Connecticut, 2012

A. For the past fifty years, US courts have been clear that individual “liberty” interests trump pretty much everything else. Including, apparently, mass murders .

For American courts, it’s a bigger deal to force someone to take a shot once a month in the arm against their will than to gun down two dozen first grade students in an elementary school.

Q. What causes paranoid schizophrenia? Brain chemicals? Then why do all paranoid schizophrenics have the same symptoms?

A. Schizophrenia is a medical illness which has a variety of symptoms – as do most illnesses. One of the symptoms is delusions. Delusions are beliefs impervious to reason.

People who have schizophrenia and are primarily delusional are called paranoid schizophrenics.

Schizophrenia is a genetic disorder that produces abnormal brain chemistry. All disease groups have the same symptoms. Like all types of pneumonia pretty much produce fever and cough.

All paranoid schizophrenics have paranoid delusions by definition.

Q. As you noted in the book, many psychologists and psychiatrists do not believe in psychiatric drugs. They deny there’s evidence chemicals in the brain cause mental illness (and some deny there’s any such thing as mental illness).

Yet you believe in their effectiveness?

A. There is no serious debate about the efficacy of modern psychiatric drugs. There are remnant groups – left over from the days of Freudian analysis and the “Anti-Psychiatry Movement” of the 1960’s – who still infect mental health policy, unfortunately at some of the higher government levels.

If I stated that there was any serious doubt about psychiatric medications among the vast majority of psychiatrists and psychologists practicing today, I have given the wrong impression. There are a few well-placed hold outs, but they will pass.

Q. You began one chapter quoting a story in the Bible regarding possession. Do you believe such a thing exists?

Courtyard at Napa State

A. No. But I come from a religious background. I was born in Utah. I am a seventh generation descendant of Mormon pioneers, so I understand that many people do believe this and that’s okay.

What’s not okay is when people try to “exorcise” the demons from the mentally ill or see mental illness as “sin” – as was common in Medieval times.

People once thought pretty much all disease was caused by demons or was sent as a punishment from God.

Unfortunately, this stain tends to linger on the mentally ill, along with many other myths.

Q. You say it’s easy to forget any particular patient is a mass murderer or child molester, and some of your closest friends are mass murderers. Can you tell us more about that?

A. As a physician, you have a natural affinity for the patients entrusted to your care. You can’t help it. My patients and I are locked in together all day almost everyday. I like a lot of them. A lot of them are murderers.

It makes me uncomfortable when I think about it, but that’s the way it is.

Q. You said a majority of doctors who work in America’s forensic hospitals are foreigners. How do they do at places like Napa? Do they experience it any differently?

Q. You said a majority of doctors who work in America’s forensic hospitals are foreigners. How do they do at places like Napa? Do they experience it any differently?A. I’m not exactly certain how they experience it but they get traumatized by all the violence just like everyone else.

The reason foreign doctors are over represented at state mental hospitals is because most American doctors won’t do it. It’s the same reason inner city clinics are populated by international physicians as well.

Americans don’t care about the mentally ill, so we have out-sourced their care.

Q. You repeatedly talk about the violence (including the doctor who was murdered and the attempted rapes and assaults). How many acts of serious violence have occurred at Napa since you began working there?

A. Hospital administration will admit to 3,000 assaults per year on patients and staff. I think the number is probably higher. I’ve been at Napa for four years so that’s 12,000 assaults.

Q. The character you called McCoy has “Hell” tattooed on his forehead. That seems about right. Can you tell us more about this?

One of the first buildings at Napa State, since demolished.

A. You picked up on the same theme as The New York Times. They entitled my Nov 11th Op/Ed piece,”When Hell is the Other Patients.”

One of the first things a veteran nurse called Napa when I first began working there was, “Thunderdome,” which is about right.

HYPERLINK “https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/h/t5...” – Show quoted text –

The post Mass Shooters Are Paranoid Schizophrenics appeared first on .

September 15, 2015

Dan O’Brien, Buffalo Ranching and Books

Cheyenne River Ranch: photo by Bonny Fleming

Readers, Dan O’Brien is a Western Renaissance man. He raises buffalo on his Cheyenne River Ranch in South Dakota, and sells his “100% grass fed, non-confined, free-roaming and humanely, field-harvested animals” for meat (no hormones or antibiotics) .

He also writes books and trains hunting falcons.

![meetdan[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1442530571i/16247144.jpg)

The ranch is just west of Badlands National Park and North of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Two of Dan O’Brien’s memoirs are about falcons and ecology (he was one of the prime movers in the restoration of peregrine falcons in the Rocky Mountains in the 1970s and 80s), and they include The Rites of Autumn: A Falconer’s Journey Across the American West (1988) and Equinox: Life, Love, and Birds of Prey (1997).

Some of his novels are historical novels exploring Indian/white relations, and they include

The Contract Surgeon

and

The Indian Agent

.

Some of his novels are historical novels exploring Indian/white relations, and they include

The Contract Surgeon

and

The Indian Agent

.Buffalo for the Broken Heart: Restoring Life to a Black Hills Ranch (published 2001), and Wild Idea: Buffalo and Family in a Difficult Land (2014), are his ranching memoirs.

I found Buffalo for the Broken Heart particularly fascinating, because it’s about converting a cattle ranch to a buffalo ranch.

His other novels include The Spirit of the Hills, In the Center of the Nation, Brendan Prairie and Stolen Horses.

Hi Dan: How many sections, or acres, do you have on the Cheyenne River Ranch?

Dan O’Brien: The Cheyenne River ranch is a unique property. The deeded land is not large – about 3,000 acres. But the ranch is surrounded by the Buffalo Gap National Grasslands which is a huge piece of federal land administered by the US Forest Service. This is public land that belongs to all Americans.

We lease about 20,000 acres of it where we run our buffalo in the wintertime. We also help manage a partner’s ranch which about 10 miles away and even larger.

We lease about 20,000 acres of it where we run our buffalo in the wintertime. We also help manage a partner’s ranch which about 10 miles away and even larger.It too is a combination of deeded and leased government land.

Q: I know you’ve written you got into the buffalo business in order to help reintroduce buffalo into the West, and show other buffalo ranchers they could raise grass-fed buffalo and not put the animals in feedlots, plus help with Western ecology, but if you had it to do over, would you have gotten in the buffalo business?

O’Brien: That is a damned good question. I ask myself that often and can only answer it by saying that all of us who are paying attention know that humans have created a crisis that dwarfs all other crisis, for all time.

If you care about what we have done, and continue to do, and you are not a coward and a quitter, you have to do something.

I am a Great Plains guy. I would not be any good at battling the forces that are ruining the oceans or the rain forests. I really have had no choice but to pitch in for what I hold dear and know something about.

Q: While reading your latest memoir, Wild Idea , I suspected you see buffalo in spiritual terms. Can you tell us more about that?

O’Brien: Yes, I see buffalo in spiritual terms, but I see most things in

spiritual terms. I suppose that I am a Pantheist but I am not all touchy feely about any of it.

spiritual terms. I suppose that I am a Pantheist but I am not all touchy feely about any of it. To me the spiritual is really a kind of practicality. Buffalo and everything else that makes up an ecosystem is holy – regarding it as such is very practical.

Q: I was fascinated with both your ranch

memoirs. They were so detailed. Did you base them on a journal you kept?