Custer’s Last Stand and The Strategy of Defeat

Hi Fred, thanks so much for the interview.

Hi Fred, thanks so much for the interview.You’ve done pretty amazing work on Custer’s Last Stand.

First, you wrote “Participants in the Battle of the Little Big Horn: A Biographical Dictionary of Sioux, Cheyenne and United States Military Personnel,” a 2011 reference work identifying every participant in the Little Big Horn battle, published by McFarland & Company.

The biographical dictionary is so thorough it includes civilians, civilian employees, scouts, horses, uniforms and weapons, among other things.

Now, you’re produced “The Strategy of Defeat at the Little Big Horn: A Military and Timing Analysis of the Battle,” also to be published by McFarland.

The latest book, headed for a January release, contains 53 pages of charts and 18 pages of source notes. Another 1,200 or 1,300 endnotes are included as well as 23 photos, four appendices, seven additional charts and 12 maps.

The latest book, headed for a January release, contains 53 pages of charts and 18 pages of source notes. Another 1,200 or 1,300 endnotes are included as well as 23 photos, four appendices, seven additional charts and 12 maps. Fred spent ten years as a Regular Army officer and an officer in the New York Army National Guard. He’s a former paratrooper, Army ranger, and Special Forces-trained psychological operations expert as well as a decorated Vietnam combat veteran and company commander. He wrote the divisional Standing Operating Procedures (SOP) manual for convoy operations in a guerilla warfare environment, First Infantry Division, Di-An, Vietnam, 1966 – 1967. Following that, he spent twenty-four years on Wall Street. He’s now on the Little Big Horn Associate Research Review editorial board.

Fred spent ten years as a Regular Army officer and an officer in the New York Army National Guard. He’s a former paratrooper, Army ranger, and Special Forces-trained psychological operations expert as well as a decorated Vietnam combat veteran and company commander. He wrote the divisional Standing Operating Procedures (SOP) manual for convoy operations in a guerilla warfare environment, First Infantry Division, Di-An, Vietnam, 1966 – 1967. Following that, he spent twenty-four years on Wall Street. He’s now on the Little Big Horn Associate Research Review editorial board.Q. How did you gather this much information? Did you have a method?

A. I have always been a prolific note-taker… probably because of my Catholic education, but maybe because I have always been interested in collecting “names” associated with certain events.

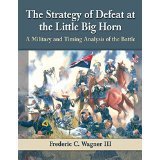

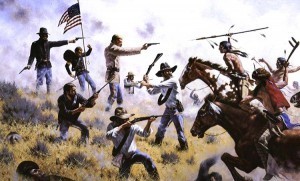

“Before The Little Big Horn” by Howard Terpning

“Before The Little Big Horn” by Howard Terpning

Whenever I find interesting anecdotes associated with a name or event, I add to it and after a while compelling stories develop. Today’s computers and their programs facilitate this collection process and the organizing of the data becomes fun for me.

Q. What did you conclude about the battle? What WAS the strategy of defeat?

A. The “strategy” of George Armstrong Custer’s defeat at the Little Big Horn lies in the interpretation of the orders he received from his boss, Brigadier General Alfred Howe Terry.

Gen. Alfred Terry

Controversy rages here, for there are some who feel Custer, because of a certain operational latitude Terry granted him in his orders… this, despite Terry’s expressed wishes to the contrary, was justified in not ascending the full length of the Rosebud Creek valley once he discovered the direction of the Indian trail.

Others feel that latitude did not pertain to subverting Terry’s desires, especially in light of the commander’s known wishes for concerted action involving his infantry forces.

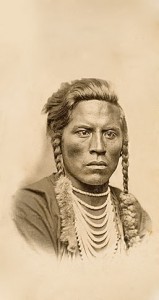

Curley, Custer’s Crow scout

Custer’s tactics must be viewed with this in mind, for had he followed the letter of his instructions his tactics would have been invariably different.

The strategy employed to accomplish his mission was sound—as were the ultimate tactics employed—but it was the subversion of that strategy—leading to those tactics—and then the subversion of the tactics that led to his defeat.

Chief Brave Bear of the Southern Cheyennes, was “elected” by other Indians as the man who killed Custer, although nobody really knew.

Had George Custer followed his orders as intended, his tactics would have changed, clearly, and while no guaranty of success, the outcome could have very well been different.

Q. Custer has many critics and many defenders. Which are you?

A. I am a critical defender of George Custer.

His orders aside, Custer performed as many military men would have… with some exceptions.

Unfortunately, those exceptions got him killed, but they were exceptions within the man’s make-up, within the man’s history, and within the man’s experience.

Unfortunately, those exceptions got him killed, but they were exceptions within the man’s make-up, within the man’s history, and within the man’s experience.Custer was an aggressive commander, but on this day he took too many risks and committed the classic blunders of an over-confident commander: refusal to heed the signs his scouts warned him about; underestimating the size and intentions of his enemy; not keeping his subordinate commanders informed; and allowing his divided command to fall away from mutual support.

Too many people blame both this division of command and his tactics for the regiment’s defeat, but neither, specifically, is the case.

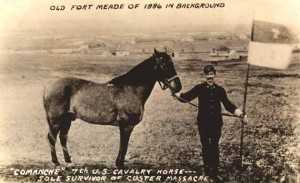

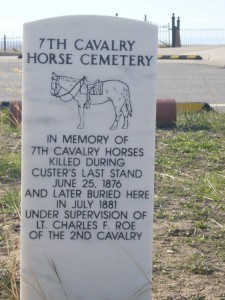

Comanche, one of only two or three horses which survived the battle

As he subverted the strategic plans, so he subverted his tactical plans by allowing these subordinates to fall away with no support.

Q. How did you figure out when each event occurred in the battle?

A. This was a long, hard, time-consuming process, aided substantially by organizing within computer software.

For some time I have believed if you do not understand the time events occurred—as precisely as possible—you cannot understand the battle of the Little Big Horn: too many events and too many personalities are interwoven.

Therefore, I set out to accumulate as much primary source material as I could find, and I developed 233 individual “profiles” (more than 80 of which are Native Americans)—some 810 pages—of battle participants and contemporaries, making a record of what they had to say.

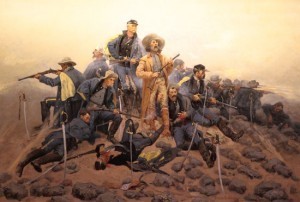

Kicking Bear’s visual depiction of Little Big Horn.

Kicking Bear’s visual depiction of Little Big Horn.

From there, I broke the battle into 37 separate events which I labeled “incident reports” and culled the “profiles” to fill the “incident reports.”

This turned into some 605 Excel pages of 5,583 lines forming 33,498 separate Excel modules of data and descriptive explanations to draw from.

Armed with all this, I set out to draw up a time study for every significant occurrence of June 25, 1876, including the movements of single individuals.

Julia Robb, Novelist.

Julia Robb, Novelist.

Published on August 09, 2014 18:38

No comments have been added yet.