Chris Dillow's Blog, page 188

January 8, 2012

Biased towards bosses

The two main parties are promising to do something about executive pay. I don't expect much to come of this, because politicians are, by their very nature, too sympathetic to managers.

This is not simply because they come from the same social class. Nor is it because MPs are bought off by the rich. It's also because of a selection effect.

The sort of people who want to enter politics - as MPs, advisors or even reporters - are generally those who think that society and the state can be managed for the better. They are, therefore, predisposed to believe that management is, or can be, a socially useful activity, which means they are biased to think that chief executives, on average, should earn a lot.

The counterpart to this bias is that they underweight reasons to be sceptical about management. They overlook the possibility that limited knowledge, cognitive biases (big pdf) and diseconomies of scale undermine the general effectiveness of management. Even more worryingly, these biases causes them to downplay the extent to which managers are rent-seekers who use their power not to improve organizational performance but to extract cash for themselves.

Worse still, politicians don't realize they have this bias. Because they are surrounded by like-minded people, they don't see that their perspective is a biased and partial one; they are afflicted by deformation professionnelle. And the media, far from correcting this bias actually reinforce it - partly because they themselves have biases towards hierarchy, and partly because their pretence that "balance" consists in merely giving equal weight to Tory and Labour MPs squeezes out alternative views.

The upshot of all this is that we have a political-media class which is excessively sympathetic to bosses - and unreflectively so. In this sense, the state helps to protect the interests of the rich not (merely) because it has been bought, but because of selection and ideological mechanisms.

January 5, 2012

"Scroungers": what's the problem?

Ed Miliband and Liam Byrne want to get tough on "evil" benefit scroungers. This is not evidence-based policy making.

Let's look at the evidence, in the form of table 12g of the ONS's survey of subjective well-being.

This shows that the unemployed are significantly less happy than those in work. In answer to the question "overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?" the average unemployed person replied 6.3 on a 0-10 scale, whereas the average employed person replied 7.5.

This is a big difference - equivalent to six standard errors. It means the unemployed are less happy than people who are divorced, widowed or who have a longstanding illness or disability.

The overwhelming majority of unemployed people, therefore, far from being content to scrounge, are pretty miserable. Any leftist party worth anything would have this as it basic premise.

In this context, the possibility that some people don't want to work should actually be welcomed by any utilitarian. The fact is that mass unemployment is probably here to stay. If a few people don't want to work, therefore, this increases the chances of other unemployed people finding a job, and thus moving out of deep unhappiness.

Let's look at this another way. Let's assume that a million "scroungers" were to move into work; this is an utterly incredible assumption, given that there are only 455,000 job vacancies, and given that there's no evidence that there are so many scroungers. But bear with me. By how much would this raise GDP?

If they were all to get full-time minimum wage jobs - earning £11,000 per year - aggregate labour income would rise by £11bn - less than 0.8% of GDP. Add in the fact that it's profitable to employ them (ex hypothesi) and we're talking a rise in GDP of around one per cent.

But this is puny compared to loss in GDP caused by the financial crisis. Andrew Haldane at the Bank of England estimated (pdf) this to be 10%. And it's looking unlikely that we'll recoup this through faster growth any time soon.

The cost of "scroungers", then, is an order of magnitude smaller than the cost of bankers.

The evidence, then, suggests that "scroungers" are, at worst, a mild problem. So why expend political capital fretting about them? The nicest thing I can think of is that this is another example of how moralizing is displacing rational policy-making.

January 4, 2012

Challenging capitalists, or workers?

Is the pursuit of the return on equity damaging capitalism? Robert Jenkins of the Bank of England's Financial Policy Committee has already answered this in the affirmative (pdf) for banks. But might it also be true for the wider economy?

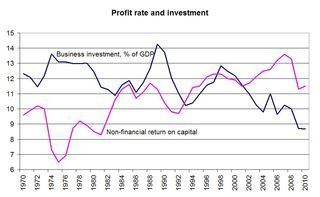

I ask because today's figures show that company profits, at least outside of manufacturing, are doing quite well. Excluding oil and financial companies, the return on capital has risen since 2009, and is now higher than it was in 2001-02 or in the early 90s or, I suspect, the mid-80s.

And a fat lot of good this is doing the economy. The volume of private sector business investment is 17.7 per cent below its pre-recession level and firms are, net, laying off workers and expected (pdf) to continue to do so. There's a marked contrast between profits, which aren't doing so badly, and the share of business investment in GDP which is near an all-time low.

Decent profits, then, are not encouraging firms to spend.

There are, of course, many reasons for this. One, I suspect, might be that firms are now much more focused on shareholder value than in the past. Until a few years ago, they would invest and hire if they had the money to do so; companies' financial surplus used to be a great lead indicator of GDP growth. But now, they don't. They pay more attention to prospective returns and less to retained profits, with the result that past profits no longer predict future corporate spending so well.

Whilst this might be rational for individual firms, it is collectively self-defeating, because as Michal Kalecki famously said, "capitalists get what they spend". Low aggregate investment means weak economic activity and thus weak profits.

Herein, though, lies a quirk. Whilst some of us are suggesting that the behaviour of capitalists is damaging the economy, Liam Byrne is obsessing about the need for a "responsible workforce". Rather than challenge the behaviour of capital, he is propagating the ridiculous myth that the workshy are a significant economic problem. In this sense, he is way to the right not just of me, but of the Bank of England. Which poses the question: is he an abominable and idiotic disgrace to the Labour party or is he instead its true face?

January 3, 2012

Entitlements & ratchets

For Christmas, I got Lucius some cat treats. Which has given me a problem. In an effort to keep his weight below a level that would distort space-time, I'm trying to ration the treats. But this leads to a irate cat meowing to demand them.

Which illustrates a problem with welfare spending. Benefits quickly become regarded as entitlements, and so reductions in them cause far more anger and resentment than we'd have if the benefits were never granted at all.

What I'm seeing with Lucius is just what we see with attempts to reduce the pensions of public sector workers or housing benefits in London, or with opposition to fiscal restraint in Greece and Italy. Payments which would be regarded as quite reasonable if they were promised instead of nothing are regarded as mean if they replace more generous payments.

It's easy to see the psychology here. There's a framing and anchoring effect.; £340 a week housing benefit is mean, when the anchor is £438. And there's the status quo bias and loss aversion; people hate losses more than they like equivalent gains.

All of this means that there is an asymmetry in public spending. It is easy to expand it, but very difficult to significantly cut it, thanks to what Vito Tanzi and Ludger Schuknecht call the "tyranny of past commitments".

As Matthew Taylor has written, there is a problem with entitlements.

All of this leads to sympathise with Daniel Sage's call for a degree of conditionality in welfare payments. My instincts say this should be a bad idea. The state should aim at setting people free from drudge work and increasing their bargaining power. Universal benefits - a basic income - would do this whereas conditional benefits mean the welfare state operates as a human resources department for capitalism.

And yet, despite this, mightn't there be a case for conditionality, slightly different from what Daniel suggests? The case is this. If governments anticipate that benefits will become entitlements, they will be loath to increase them, for fear of them becoming hard to cut should the perceived need arise. If, however, the benefits are conditional, this reluctance will be smaller; governments could figure that the lack of an entitlement culture will make it easier to reduce future spending. They might, therefore, pay larger benefits. This effect would be augmented by voters' greater willingness to pay benefits if they believe (rightly or wrongly) that they are not giving handouts to scroungers.

In other words, conditional benefits - flawed as they are in principle - might have the virtue, from a leftist point of view, of leading to more generous provision than unconditional ones.

I say this tentatively, partly because I'm arguing against my own instincts, and partly because so many of those who want more conditionality also seem to want a smaller welfare state too. My point is simply that we should compare the merits of conditionality and entitlements not just in static terms, but in dynamic ones: which would lead to greater redistribution over the long-run?

January 2, 2012

"Demands"

James Bloodworth's post, entitled "some basic demands the left must start to make" raises a longstanding peeve of mine.

This is that the use of the word "demand" - which has long been common on the left and among trades unions - is a terrible rhetorical strategy. People who make demands are tiresome - demanding! - and unreasonable. The very use of the word is therefore a turn-off.

We know that people's attitudes are shaped by the way in which options are framed. The left's use of "demands" is a counterproductive frame.

The right, and the capitalist class, knows this. Read pretty much any rightist blog, and I doubt you'll see their policy proposals regularly framed as demands, as James and the left so often do. And, of course, employers have for years made "offers" - how generous! - whilst it is unions that make demands. But this is not necessary. Unions could easily reframe pay "demands" as reasonable offers: "our members are offering to work for one-200th of the salary of the chief executive."

So, how might "demands" of the sort that James makes be reframed? Here are three possibilities:

1. An assertion of rights. James says we should have a right to recall MPs who break manifesto promises. But why frame this as a "demand"? Why not instead say that the breach of such promises is tantamount to a breach of contract and thus a violation of basic democratic rights? Framed this way, it is manifesto-breaching MPs who are making unreasonable demands - demanding to stay in office despite lying to voters.

2. Stress the benefits of the policies. For example, egalitarian policies such as taxing the rich or nationalizing utilities can - if you insist - be presented as a way of increasing aggregate demand, by redistributing income from savers to spenders.

3. Use the language of inevitability and necessity; you don't have to demand what will happen anyway. Marxists, of course, used to do this, to the chagrin of champions of free will such as Isaiah Berlin. But the trick has long since been copied by the right. It has claimed (reasonably) that bank bailouts were necessary and (less reasonably) that public spending cuts are. And of course every boss trying to justify mass layoffs does so by claiming they are necessary.

The left should relearn this trick. Rather than "demand" change, it should point out that things can't go on as they are, and so change is necessary.

Now, in saying all this I'm not picking a fight with James; his post actually comes close to doing what I've suggested. My beef is instead with the left's lazy and dangerous repetition of the "demand" frame.

December 30, 2011

Why politics fails

Sean McHale says Ed Miliband should learn from Barcelona. In doing so, he draws attention to why politics is so flawed a discipline.

Sean says that, in the Real Madrid game, Victor Valdes continued to play short balls out of goal despite the fact that doing so had gifted Madrid a goal early doors. He advises Miliband to similarly stick to one track rather than fumble around in the dark.

This misses the huge difference between Valdes and Miliband*. Valdes could draw on vast experience which shows that playing it short is, for Barcelona, a successful strategy. But Miliband has no such large evidence base to draw upon. And this makes his job far tougher. Valdes could rationally interpret a failure of a single short ball as an exception to a generally good strategy, because he had played countless such balls successfully before. He therefore had a strong Bayesian prior that short balls work, on average. But Miliband, lacking such relevant precedents, can have no such strong priors. If he sees a policy statement fail to win support, he cannot infer, Valdes-style, that this is a rare exception to a successful overall strategy. Instead, a rational Bayesian would be more likely to infer that he is on the wrong track.

In this sense, Sean's call for Miliband to stick to his instincts might be mistaken. What caused Valdes to continue playing it short was not instinct, but rather a rational judgment based upon experience. Miliband, however, is not in so happy a position.

Miliband is not unique in this. Politicians very often find themselves in positions where they have few precedents from which to form judgments - a problem exacerbated if they are ignorant of history or of other countries' experiences. It will, therefore, be far harder to find the right strategy, and even if they do an early failure might cause them to wrongly but rationally change course.

In this sense, politicians are more like entrepreneurs than managers. A defining feature of the entrepreneur - as distinct from the manager - is that, as Israel Kirzner said, he is a person who must act on the basis of limited precedent and knowledge. Such actions are liable to fail.

But there's a massive difference between entrepreneurship and politics. We have found a way of improving the odds of entrepreneurial success. We allow many entrepreneurs to compete against each other, to see who succeeds; this is why free entry into markets and access to capital are so important. In politics, however, competition is much more limited and entry restricted. So the natural selection we have in markets operates much less well.

In this sense, political activity offers us the worst of both worlds. It has neither the body of experience, evidence base and precedent that sportsmen, engineers, bureaucrats, lawyers or some artists can draw upon. Nor does it permit the ruthless natural selection that well-functioning markets do. It is, then, small wonder that, as Enoch Powell said, "all political lives end in failure."

* OK, there are other differences, not least of which is that Valdes is surrounded by geniuses. I'm confining myself to just one.

December 29, 2011

MIliband's unthinking managerialism

Ed Miliband's new year message demonstrates that the Labour leadership still has an unreflective managerialist ideology.

He starts by saying, rightly, that "many people feel politics cannot answer their problems." He continues: "My party's mission in 2012 is to show politics can make a difference. To demonstrate that optimism can defeat despair."

But this raises the obvious question: if Labour can show that "optimism can defeat despair", why has it so far failed to do so?

Miliband seems unaware of this problem. And there are some obvious cognitive biases which allow him to suppress such dissonance. One is the optimism bias: "we can do better." There's also the egocentric bias: "it's me who'll find the solution." And there's also base rate neglect: "let's ignore the fact that we've failed in the past". As Dan Hodges taunts, Miliband is simply pretending that 2011 never happened.

This belief that one can reach a happy future even though you have failed to do so in the past is a characteristic feature of managerialist ideology. As I wrote in my book:

To the managerialist, the past is irrelevant. All that matters is the future. Management is always "moving forward", "striving", "progressing". To managerialists, the best is always yet to come.

In writing that, I was, of course, echoing Alasdair MacIntyre's line that the managerialist state is "always about to, but never actually does, give its clients value for money."

Herein lies my fear. Just a a fish cannot see that water is wet, so Miliband cannot see that he is taking a profoundly ideological position here - the idea that centralized leadership can find solutions even though it hasn't done so in the past. And if you can't see that your position is ideological, you've no hope of considering that it might be wrong.

December 21, 2011

Cakes, capitalism & happiness

To celebrate the start of my Christmas holiday, I've spent the morning baking: sausage rolls and a lemon drizzle cake. Doing so reminded me of the Easterlin paradox - the puzzle that rising incomes have not greatly increased happiness.

I say so because a new paper by Maurizio Pugno has formalized one explanation for this, which draws on Tibor Scitovsky's The Joyless Economy.

The idea here is that our leisure can be spent on either comfort goods such as watching TV, shopping or drinking, or creative activities such as baking, playing guitar or gardening. However, we do too much of the former and not enough of the latter, which is detrimental to our well-being.

One reason for this is that comfort goods can be addictive, with the result that we feel guilty afterwards about over-consuming. This isn't just true of alcoholics and shopaholics; we might also feel bad about slobbing out in front of the TV.

Another reason is that pure consumption goods might invite adverse comparisons with others, which make us feel worse off. If your neighbour has an expensive car, you might feel bad in a way that you don't if your neighbour is a good guitarist or baker. Through this route, economic growth - more neighbours with fancy cars - reduces happiness.

But why do we spend too much time on comfort goods and ordinary consumer spending and not enough on creative activities? One reason, says Pugno is that the latter require investment in "leisure skills" - the ability to play an instrument, garden or appreciate art. Such investment, like any other, is costly. At any point in time, therefore, we might prefer the zero-cost option of comfort goods. But this means we never acquire the skills needed to make best use of our leisure.

I'd add three other mechanisms that exacerbate this problem:

1. The failure of affective forecasting (pdf)- our inability to predict our future happiness. Two aspects of this general failure are relevant here. One is duration neglect; we pay too much attention to the short-term costs of acquiring leisure skills (the burnt cakes or the inability to get a note out of the sax) and so prefer the easy option of watching TV. Another is immune neglect - our failure to anticipate that we'll get used to some things, and so lose satisfaction from repeating them.

2. Path dependency. If you grow up in a home where your parents came home from work too tired to do anything other than watch TV or go down the pub, you'll think of such leisure activities as normal, and so will not think of better ways of spending your time. Because of this, it was not until I was 40 that I laid a finger on a musical instrument. And even today I feel uncomfortable if the TV isn't on in the evening.

3. Lack of self-control. Even if we knew that investment in leisure skills would pay off in the future, in the sense of getting greater utility from leisure, our lack of self-control would cause us to under-invest. Bruno Frey has showed (pdf) how this causes folk to watch too much TV.

There is, therefore a strong bias towards over-consumption of comfort goods and under-investment in creative activities - which contributes to the Easterlin paradox.

Herein, though, lies a point which is under-estimated. A healthy capitalism probably requires that this be the case. The shopaholic who feels guilty about her purchases does more good for capitalism that the man who tends to his allotment instead. And the person who's desperate for work so they can spend is more use to capitalists than the guy who doesn't mind being unemployed for a while because he can practice his guitar.

In its small way, my lemon drizzle cake sticks it to The Man.

December 20, 2011

History matters

The US is still suffering from the legacy of slavery. This new paper (pdf) shows that states which had lots of slave labour in 1860 have today larger racial inequalities in educational attainment and - because of the lower human capital of its black population - have also suffered slower income growth.

This adds to the evidence economists have accumulated which shows (pdf) that quite distant (pdf) socio-economic circumstances (pdf) have material effects today. History, then, matters more than you might think.

This, in turn, should matter for how we think about ourselves. I am one of the richest humans who ever lived. This is not because I am uniquely hard-working or intelligent; such notions are only slightly less cretinous than the idea that I owe my wealth to my great social skills. Instead, I'm rich because I had the good fortune to have born in England in the late 20th century* - in a time and place where history has been kind.

We are not self-made men, but rather creatures of history.

And if history is so powerful an influence, other things are less so - one of these being the managerialist whims of politicians.

It's in this context that we should regret the decline of history teaching.

Herein lies a paradox. I get the impression that those who would most like to see history given more importance in schools are Tory traditionalists who want to teach some Sellar and Yeatman-style story of our sceptre'd isle. However, Sellar and Yeatman were wrong**. History is not just "what you can remember." It has effects whether you know it or not. We are who we are because our ancestors did what they did. Knowing this, however, undermines right-wing fairy tales about people being the products of their own decisions. In this sense, Tories are the last people who should want history taught.

* Pedants might claim that I was born nearer to the middle of the century. Dull empiricism isn't everything.

** Yes, I know Sellar and Yeatman were parodists, but I'm not sure about Michael Gove.

December 19, 2011

Economists' influence

Arnold Kling is wondering why economists have so little influence in the White House. But it's not just the White House where they go unheard. A feature of the euro area's debt crisis has also been that economists' many ideas for solving the problem have been ignored. Economists' lack of influence is not a local US phenomenon.

Why is this?

One reason , I fear, is that voters just don't want to hear from economists. If you think the US deficit can be cut painlessly by cutting government spending without touching Medicare or Social Security, or by taxing the very rich alone, you'll not want to listen to people who say things aren't so simple. And if you think feckless borrowers and lenders should be punished, you'll not be interested in those who think that moral hazard is only part of the euro area's problem.

This is magnified by one of the curses of our age - narcissism. Too many people think that all that matters is their own opinion, and shut out the dissonance that economists should provide; in many contexts, the fundamental principles of economics are "it's not that simple" and "we can't be sure."

It's further magnified by another problem - the media. As Dr Dr says:

News reports must be less than two minutes long and preferably attention grabbing. Information has to be condensed, ideally dramatically…There is no room for complexity, for untidiness. Just as the documentary is a simplification, so too is the news.

Such an approach is not value-neutral. It sustains a bias against social science.

However, economists' lack of influence isn't just a demand-side failure. There's also a supply-side problem. The predominant image the public have of economists is that they are forecasters. For years, whenever I told anyone I was an economist, the immediate reaction was: "What's going to happen to my mortgage rate?" But of course, forecasts go wrong and so economists' reputation suffers.

In this sense, we economists present the very worst aspects of our discipline to the public. Which is the opposite of what the natural scientists do. Cosmologists invite us to wonder at their discoveries, whilst glossing over the fact that they haven't a clue what most of the universe consists of. And medics crow more about their latest cures than the fact that medical errors kill tens of thousands each year.

This, though, is no accident. Economists make forecasts for the same reason that Willie Sutton apocryphally robbed banks - because that's where the money is.

In this sense, economists' disrepute and lack of influence merely vindicates one of the fundamental insights of our discipline - that incentives have effects, and sometimes unintended and adverse ones.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers