Chris Dillow's Blog, page 192

November 14, 2011

Do markets need social conservatism?

Liberal capitalism requires social conservatism. It needs the virtue-generating institutions or there'll be no thrift, no duty, no honesty, no Protestant work ethic.

I half agree. I agree that, in order to work well, a market economy does need particular personal virtues, for example, it needs:

- a strong work ethic, so that labour supply will be high. One reason why early factories employed children was that adults did not have the habit of working long hours.

- temperance, so we save and accumulate capital; one cause of the crisis is that we offshored this one.

- trust, so that the invisible handshake (pdf) can be used to solve market for lemons-type problems.

- lawfulness, so businesses can invest in the confidence their profits won't be stolen. It's the lack of this that helps explain why poor areas stay poor.

Where I have my doubts is whether socially conservative policies really do generate virtues. For example:

- Can the state really legislate morality? It's not obvious that laws against drug use have succeeded in promoting the virtue of abstemiousness.

- Should the state really promote "strong families"? Single parenthood - as distinct from poverty - is not a cause of crime or low employability. Given this, tax breaks to "promote marriage" would be more a deadweight handout to one's favourite people, rather than a means of solving social problems. There's nothing virtuous about this.

- Could it be that building virtues requires anti-conservative policies? Eric Uslaner (this pdf and this one) has shown that inequality breeds distrust. It also possible that it encourages thriftlessness as the poor borrow to keep up with the spending of the rich. If this is the case, then virtues might be promoted not by conservative policies but by egalitarian ones.

My point here is simple. Even if we accept - as we should - that a free market economy requires certain virtues to work well, it does not follow that those virtues are best promoted by conservative policies.

November 13, 2011

In praise of disengagement

The publication of Sophie Ratcliffe's P.G Wodehouse: A Life in Letters has re-opened the awkward issue of his "collaboration" with the Nazis, in the form of his notorious Berlin broadcasts.

Better people than I have defended Wodehouse on this matter. However, I want to praise his motives for those broadcasts.

Let's be clear. Wodehouse was not a Nazi sympathizer; no-one who reads his depiction of Spode's Black Shorts - "a handful of halfwits" - could possibly think that. Instead, he faced an involuntary dilemma: to accede to the Germans' invitation to broadcast and have a quiet life in which he could continue writing, or to refuse and face perhaps a more uncomfortable internment.

Choosing the easy option arose from the same motive that gave us his writing - an escapism, an urge to block out to unpleasant real world. As he said, "I haven't developed mentally at all since my last year at school." His books contain, AFAIK, barely any reference to the two wars or great depression; they are, in a way, as much a fantasy as his near-contemporary's Tolkein's. Orwell overstates things when he says there are "no post-1918 tendencies at all" in his writing, but not by much.

What's more, this disengagement from reality was perhaps necessary for his writing. Wodehouse was a workaholic of "awesome focus"; he wrote over 90 books in his lifetime (not to mention countless song lyrics), many of which he redrafted dozens of times. You can't do this - and certainly not as lightly as he did - if you trouble yourself with ugly politics. In this sense, his disengagement and his genius are two facets of the same thing.

There's a lesson here for us all. Good work can only be done by blocking out some things, by ignoring what we cannot affect and focusing upon what we can. The polar opposite of Wodehouse is Dickens' Mrs Jellyby, who devotes her life to the futile Borrioboola-Gha project, whilst neglecting everything around her.

There's another difference between the Wodehouses and the Jellybys. To have refused to broadcast would have been an empty gesture. It would not have materially weakened the Nazis or strengthened the Allies by an atom. All it would have done would be to signal Warehouse's "moral compass". It would have been an egotistical posture. Yes, we live in an era when such posturing is the norm. But this shouldn't hide the fact that some of us feel uncomfortable with the "pathetic sincerity of outrage".

The Jellybys make the noise. But it's the Wodehouses - the quiet men who choose not to take a stand but to carry on with their work - who deserve out gratitude.

Against all this, you might cite Burke's (supposed) dictum: "All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing". Sometimes, however, nothing is all that good men can do. And wise ones know it.

November 11, 2011

Strategic ignorance

It's widely thought that James Murdoch is either a liar or a fool: either he genuinely did not know about phone hacking, in which case his was failing in his job, or he did know, in which case he misled MPs. As Tom Watson said yesterday:

It is plausible that he didn't know but if he didn't know, he wasn't asking the questions that a chief executive officer should be asking…Either he wasn't doing his job properly as the chief officer of the company or he did know.

This dichotomy, however, might be a false one. It is quite possible, in theory, for a rational boss to be intentionally ignorant as a tool to increase his bargaining power.

The idea here derives from Thomas Schelling's Essay on Bargaining, wherein he shows that ""In bargaining, weakness is often strength." Ignorance - normally a weakness - can increase one's bargaining power. For example:

- If we have to share a box of chocolates and I get first grab, I might scoff all my favourites and plead: "I never knew you liked the coconut ones."

- If two cars are driving towards each other on a narrow country road, the driver who knows the danger of a collision takes the risk of swerving whilst the one who's oblivious stays on the road.

- The man who doesn't appreciate the cost of a breakdown of negotiation - say who doesn't know how much a strike will cost - will adopt a tougher negotiating stance, and so extract more concessions, than the man who doesn't.

These are no mere theoretical possibilities. A new paper by Julian Conrads and Bernd Irlenbusch provides experimental evidence that ignorance can be a useful bargaining weapon - even if that ignorance is wilful rather than accidental.

One can imagine how such strategic ignorance might strengthen a boss's position relative to his staff. Imagine an employee knows of, or has actually engaged in, wrongdoing. He approaches his boss: "If you don't give me a big pay rise, I'll speak out about this company's crimes." Who's most likely to cave in - the boss who knows what's gone on, or the one who can credibly claim to know nothing and so either face down the demand or escape ordure if the threat is realized?

Ignorance, then, can be power.

You might object here that a good CEO is a custodian of the company and so should know what's happening. This is naïve pish. The function of a CEO is not to take care of the firm, but to take care of himself. And sometimes, he does so by knowing nothing.

Now, I'm not saying this is what Murdoch did. What matters in this context is not ignorance but credible ignorance. And the best way to be credibly ignorant is to be genuinely ignorant. All I am saying is that the fool-liar dichotomy - intuitively plausible as it seems - is not necessarily correct. Sometimes, it is wise to know nothing.

November 10, 2011

Measuring inequality

Tim says that inequality falls in recessions, because top incomes are determined by market forces and so fall whilst bottom incomes are welfare benefits which, barring reforms, are fixed in real terms. The data seem to support his view; the Gini coefficient for post-tax and benefit incomes did fall slightly between 2006-07 and 2009-10.

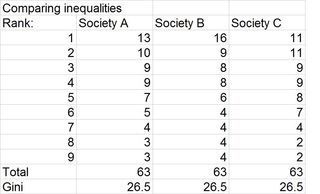

But how meaningful are Gini coefficients? Consider the three societies in my table. All are equally rich, with an average income of 7. Which is the most unequal?

If we look at the incomes of the poor, C is unequal. There, three people have an income of half or less of median income. In B, no-one has so low an income. In A only two do.

But if we look at the gap between the rich and the median, we get the opposite ranking. Society B is highly unequal, whilst C is egalitarian.

If we take the ratio of top incomes to bottom incomes, C is most unequal and B is most equal. However, if we take the absolute gap in incomes, the opposite is true.

So, which society is the equal one? Gini coefficients cannot adjudicate here. They are all the same, by construction. In society C there are small inequalities at the top, but big ones between average and bottom. In B, there are big inequalities in the top half and small ones near the bottom. These inequalities cancel out.

I don't think my example is contrived. You can think of society B as one with a "squeezed middle" - individuals ranked 2 to 6 are worse off than in society A - and with "winner take all" features that generate a very wealthy minority, but with a relatively generous welfare state. If you like, it's a New Labour society. Or if you like, it's a society in which the richest manage to get government bail-outs whilst the middle class suffers.

Society C, however, is the opposite. It's a bourgeois society, with a big middle class but a weak welfare state.

Which is preferable? Utilitarians can't adjudicate, as average incomes are the same. Nor can the egalitarian who looks only at Gini coefficients, as these too are all the same. Rawlsians would prefer society B, as this maximizes the position of the worst-off member. Others, though, might prefer C, as it gives us a six in nine chance of getting an average income or better, whilst society B gives us only a four in nine chance and A gives a five in nine chance. Still others might find B least attractive, if they fear adverse social or political consequences of having a very wealthy elite, or if they have (non-consequential) libertarian objections to the large transfers that fund the welfare state.

My only point here is perhaps a trivial one - that simple measures such as Gini coefficients (or I suppose any other single measure) tell us very little about complex phenomena such as inequality.

November 9, 2011

Probability triggers

There's a link between the question of whether John Terry should be England captain and what to do about Iran's possible development of nuclear weapons. Both raise the question: upon what level of probability should we act?

This level varies according to circumstance. At one extreme we have the criminal law, which requires that a defendant be proved guilty beyond reasonable doubt. This means we only act upon very high levels of probability - though how high is not (pdf) clear.

But in other cases, we apply the precautionary principle - a small probability of danger is sufficient to act to prevent harm. And in financial markets, a 1-2% probability suffices to trigger action - for example when the "tail risk" of a default or financial crisis causes investors to dump a financial asset.

The fact that, depending on context, we use very different probabilities tells us that our choice of "probability trigger" rests not upon epistemological grounds but rather upon cost-benefit ones.

For example, because we consider the cost of imprisoning an innocent man very high, we set the probability trigger high in criminal cases. Similarly, the cost of default might be so high that it is worth acting to avoid the small probability thereof, so we set the probability trigger low.

And the same might apply to Iran and nuclear weapons. Even if there is only a small probability of Iran getting a nuclear weapon, the cost of this might be so high as to justify military action now to prevent it.

All of this might seem trivial. It's just expected utility theory.

However, there are some non-trivial effects here.

One problem is that there's a trade-off here between efficiency and justice. In criminal justice cases, requiring proof beyond reasonable doubt allows some guilty people to go free. This is justified by Blackstone's formulation: "better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer". The converse can also apply. Expected utility might justify a pre-emptive strike on Iran's nuclear facilities, even if this entails the injustice of killing some innocent people.

And here, two other complications enter.

One is that we often misapply probability triggers. It has become a cliché to say that Terry is innocent until proven guilty. But this is wrong. There is no reason to apply the standard of criminal proof in this context. Stripping a man of the England captaincy is very different from depriving him of his liberty. We don't need proof that Terry is a racist to remove him from the captaincy. The mere possibility that a man is racist is - when combined with his other character flaws - sufficient to deny him the largely honorific position of England captain. Alan Green - a man I usually have no time for - sees this better than others.

A similar error sometimes happens in discussion of climate change policy. We don't need proof that man-made global warming is happening to justify reducing carbon emissions. All we need is for the cost of reducing emissions to be smaller than the probability-weighted cost of a climate disaster.

Secondly, our thinking about these issues is clouded by countless cognitive biases. One particular one here might be the zero-risk bias - our preference for reducing risk to zero. This might lead us to want "proof" - such as in the Terry case - even where none is needed. It might also bias us towards acting against Iran - because we might want to over-pay for reducing to zero the risk of them obtaining a nuclear weapon.

All I'm saying here is that apparently minor cases such as John Terry and major ones such as Iran's weapons programme raise awkward issues of both probability and ethics - issues which we are not necessarily well-equipped to deal with.

November 3, 2011

It's not a debt crisis

It is a cliché that the big fear for markets is that Italy will suffer a full-blown debt crisis. This leaves an important point unsaid.

Italian government debt is €1.8trn (pdf), or $2.5trn. If it were to default on 50% of this - worse, I suspect than most people's worst-case scenario - there'd be a loss of wealth of €0.9trn or $1.25trn.

This is not much. Two things tell us so.

First, the marginal propensity to consume out of financial wealth in the euro area is around 1.4c per euro. This implies that if Italian debt were held by euro area households, such a loss would lead to a drop in consumption of 0.014 x 0.9 = €0.126trn. This is 0.14 per cent of euro area GDP. Which is barely significant*.

Secondly, economies have suffered far larger losses than this and survived easily. Between March 2000 and October 2001, the Wilshire 5000 index fell from 14750 to under 9900. Holders of US shares therefore lost $4.9trn - four times that loss on Italian debt. But that led to only the mildest of recessions.

Why then are relatively small - and theoretically manageable - losses so frightening the markets?

It's not because the problem won't be confined merely to Italy. Throw in a 50% write-off of Spanish and Portuguese debt as well, and we still have a loss of only €1.3trn ($1.8trn).

One possibility is that in 2000 investors regarded high share prices as "house money" - the result of good luck - and so were more relaxed about its disappearance than they would have been had it been the "real" wealth that is government bonds.

This, though, might not be all the story. Expectations for equity returns in 2000-01 - among both households and companies - were high, so the market's fall came as a shock. That should have hit consumer spending and capital spending.

Instead, there's another reason to fear. There's a massive difference between US equities in 2000 and Italian government debt. US shares were held mostly in small sums by millions of investors. The losses were thus small and manageable for most sensible investors, and even where they weren't, the losers were not strategically significant for the economy. Italian debt, however, is heavily held by a few banks and their losses - unlike the larger losses on US shares - threaten to have multiplier effects via a reduction in bank lending.

This seems obvious. But it represents a (further?) rejection of the neoliberal pre-crash orthodoxy. This said that the virtue of freeish financial markets was that they allowed risk to be split up and borne by those best able to bear it. But the euro debt crisis shows this not to be the case. If government debt holdings were dispersed, the crisis would be trivial. But they are not, so it isn't.

What we have, then, is not a government debt crisis at all. Instead, we have a crisis of risk-bearing. The problem is that risk is borne by not by markets but is excessively concentrated in systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Which poses the question raised by Thomas Hoenig: do SIFIs have a future?

Ideally, the answer would be: no. The problem is, though, that European policy-makers are not even asking the question.

* Things aren't quite so simple. A Italian default could actually boost the wealth of Italian tax-payers (there are some) by reducing future interest payments. This might, however, be offset by higher interest rates on the remaining debt as investors require compensation for the risk of further default. I'm ignoring this complication.

November 2, 2011

Science, ego and power

Sarah Vine in the Times (£) says something quite remarkably stupid. Commenting on the IFS's research showing that people born in August tend to do less well at school than those born in September, she writes:

Some of the cleverest, most confident people I know are August babies…All of which just goes to show you can't take statistics too seriously.

You don't need me to tell you what's wrong with this. The IFS research points to smallish differences in average attainment. This is entirely consistent with some (many) August babies doing well.

The problem lies not in taking statistics too seriously, but in not taking them seriously enough.

Of course, pointing out that a newspaper columnist is writing rubbish is as revelatory as noting the religion of the Pope or ursine defecatory habits. But because columnists are paid to echo the prejudices of their readers, I fear that Ms Vine's remarks are significant, and depressing, in two ways.

First, they are indicate a philistinistic anti-intellectual culture, which elevates ego over rational inquiry: "never mind your evidence and hard work, just look at me and my chums." This attitude naturally retards the growth of public knowledge about social affairs. As I've said before, what we need is a campaign for social science.

Secondly, there is a class aspect here. Ms Vine ignores the fact that the odds are biased against August babies and so invites readers to believe that their relative (average) lack of educational attainment is their own fault. And this error generalizes. Some inequalities do their damage by working as statistical tendencies - for example, people from poor homes are more likely to suffer ill-health and less likely to do well at school. Relying on anecdotal evidence can serve to disguise these tendencies: "When I was at Oxford I once met someone from a poor home." In doing so, the costs of disadvantage are diminished.

In this sense, an ignorance of the very basics of social science can serve a reactionary function. Rejecting empirical enquiry means accepting the prejudices that sustain inequality.

November 1, 2011

Criminals like us

Criminals are just like the rest of us. This is the finding of a fascinating new paper.

Researchers at the Norwegian School of Economics got inmates of a medium-security prison to play a dictator game, in which they were given 1000NKr (about £175) and the option of giving 0, 20, 40, 60, 80 or 100% to a randomly-selected partner. On average, prisoners gave away 36.2%. This is statistically indistinguishable from the 34% given by non-prisoners of the same age and gender.

This similarity is not driven by honour among thieves. When the partner was a non-prisoner, prisoners gave an average of 34.2% whilst non-prisoners sent an average of 32.2%.

Much the same is true when subjects were asked to play a trust game. In this, the experimenter trebled the money the giver handed over to the recipient, and the recipient then chose to return some of the cash to the giver. Again, there were no differences in the behaviour of prisoners and non-prisoners, whether they were givers or recipients.

The message here is stark. Prisoners have almost identical pro-social preferences to the general population. Criminals are not unusually anti-social. There are three possible interpretations here:

1. This corroborates the economic view of crime, as inspired by Gary Becker (pdf). Criminals differ from the rest of us not by being anti-social or "feral" but by facing different incentives. On this view, criminals are criminals because - for them - the expected benefit of crime exceeds the expected cost.

2. Maybe preferences are not the issue here. Some people might be criminals because they lack self-control, and can't go straight even though they'd like to. (The difference between this and point (1) might be slender for practical purposes, if criminals are easily tempted).

3. Social preferences are not consistent across individuals, but rather differ from context to context. Some people might be averagely pro-social in front of a computer screen and an academic, but not so when they are on the street.

Whatever the explanation, the fact seems to be that differences in behaviour cannot be easily explained by differences in observable preferences. It might be, then, that our attitudes to crime are contain an element of the fundamental attribution error - we over-rate the role of individual agency, and under-rate other forces.

October 31, 2011

Politics & the crisis: two narratives

Paul raises a significant and surprisingly under-appreciated point - that there's a worryingly wide gap between economic explanations of the crisis and political responses.

My preferred explanation for the crisis draws heavily upon Ravi Jagannathan's (pdf). Put simply, the combination of China's export-driven growth and the desire to build up FX reserves to prevent a repeat of the 1998 currency crises generated a glut of savings which was invested in western bonds, causing a fall in their yields.

In principle, this drop in interest rates might have triggered a boom in real capital spending. But it didn't, perhaps because the "great stagnation" meant there was a dearth of investment opportunities. Instead, lower rates unleashed a bubble in house prices, the bursting of which brought down banks.

There are five features of this account which politicians ignore:

1. This is a global story, not a parochial one.

2. The squeeze on workers' living standards is not merely due to high inflation (which is temporary) or to the legacy of the crash. It is also the result of the increased supply of labour created by China's entry into the world economy.

3. Banks are not the prime mover here, but rather a conduit for these global forces. I mean this is in two senses. First, their creation of mortgage-backed securities was a response to demand; falling yields on proper AAA securities led to a "hunt for yield" which bankers thought they could satisfy by bundling up mortgages. Secondly, the counterpart of current account surpluses in Asia is current account deficits in the west. And a current account deficit, by definition, is an excess of investment over savings; investment here means house purchase, not just capital spending. But if a nation has an excess of investment over saving then it is likely that its banks will have to rely upon wholesale funding, because deposits (savings) will fall short of loans (investment). It is no accident that the "UK" domiciled banks that weathered the crisis were those that were properly globalized such as HSBC and Standard Chartered, and so able to call upon a large Asian deposit base. And it's no accident that the banks that failed - Northern Rock, Bradford and Bingley - were dependent upon retail deposits, which were lacking.

4. The fact that the government was running a fiscal deficit before the crisis was not its fault. It was instead a simple accounting identity. If foreigners and companies are net savers, then other sectors must be net borrowers. This was partly the household sector, but also the government.

5. Policy can do little to raise growth. This is not merely because the effect of financial crises is to depress growth rates. It is because the crisis has its origin in large part in a decline in potential growth, which is what the dearth of investment opportunities represents. Deregulation or a "plan B" might ameliorate this problem, but they are unlikely to solve it.

What we have here, then, are two narratives between which there is an almighty gulf. There's the economic narrative of the crisis. And there's the party political narrative, which blames bankers' greed, neoliberal economics, regulatory failure or Labour's profligacy - all of which are only incidental features.

This, I suspect, helps explain or justify why there is so much apathy towards party politics, even amongst the most intelligent.

As for what could be done to change this, I would recommend that politicians stop pretending to have ways of getting us out of the mess, and focus instead upon how to more equitably distribute the hardship. A first step here would be to stop stigmatizing the unemployed.

October 30, 2011

GMT, ideology and power

The ideology that supports the power of the ruling class does not consist merely of explicit propositions. It also comprises silences and blind spots - things that are not seen or said. The debate about whether to turn the clocks back or not illustrates this.

Rick thinks our existing arrangement is "bonkers":

Shifting the middle of our daylight hours to 12 noon means that for almost everyone, there will be light in the morning when they don't need it and darkness in the evening when they do.

The argument against this is that if we don't put the clocks back, it would stay dark in Scotland until mid-morning, causing more accidents as people travel to work in the dark.

This debate is daft. Whatever we do to the clocks, we'll only get eight hours of daylight in the winter. The only way to increase hours of daylight is to winch the country southwards.

Which raises the question. Instead of changing the clocks, why don't we adjust our hours of work and schooling instead? If it's dangerous or unpleasant to go to school or work in the dark mornings, just start the school or working day later. In the lighter south, the school day could start at eight and finish at three. In the darker north, it could start at ten and finish at five.

Businesses could do a similar thing. A northern one could weigh the convenience to its employees of starting later against the desire to keep the same hours as southern customers, and choose the optimum hours accordingly.

Granted, it would be a little inconvenient for schools and businesses to change hours twice a year. But this would be mitigated by the convenience of having the same clocks as our European trading partners.

This seems obvious. So why isn't it being considered, and why are we faffing around with talking about changing the clocks instead?

Enter the ideological blindspot. Working hours are not chosen for the convenience and safety of employees. They are instead a means whereby the capitalist asserts his power over workers, and whereby workers are dehumanized and turned into mere means of production. As Andre Gorz wrote:

The scientific organization of industrial labour consisted in a constant effort to separate labour, as a quantifiable economic category, from the workers themselves. This effort initially took the form of the mechanization, not of labour, but of the actual workers…

Time for working and time for living became disjointed; labour, its tools, its products, acquired a reality distinct from that of the worker and were governed by decisions taken by someone else. (Critique of Economic Reason, p 21-22)

And the school day is imposed upon children in order to inculcate into them the discipline of capitalist work.

So successful has capitalism become in normalizing this discipline that we do not even see it. The strongest powers are those we take for granted. And this blindness leads to the madness of changing the clocks when we could instead change our behaviour.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers