Chris Dillow's Blog, page 191

November 25, 2011

Clegg's youth con

Nick Clegg says his Youth Contract will "provide hope" for the young unemployed. He omits to add that it will provide a nice little earner for employers.

He plans to give 160,000 subsidies of up to £2275 for businesses who take on an 18-24 year-old from the Work Programme.

I've got four problems here.

1. To some extent, this is paying firms to do what they would do anyway. Remember that even in a weak labour market, hundreds of thousands of jobs get created. In Q3 of this year - a time when net employment slumped - 977,000 people (pdf) moved into work. In other words, even in bad times, employers take on loads of people. Clegg is thus giving them money for what they are already doing. It's corporate welfare.

2. At the margin, the subsidy will encourage firms to take on more youngsters in the Work Programme. But to a large extent, they'll do so by hiring workers eligible for the subsidy at the expense of those ineligible ones - that is, the shorter-term young unemployed and the over-24s. Opportunities for the young long-term unemployed will thus improve, at the expense of others.

3. This is not a fiscal expansion. The BBC reports that the scheme might be financed by cuts in tax credits. But lower tax credits mean lower consumer spending and hence less employment of young people.

4. This scheme is not simply about expanding the opportunities for young people. The Telegraph reports:

Teenagers "failing to engage positively" with the Youth Contract and take up job placements could be forced to accept them. Those dropping out of the programmes might have their benefits removed.

There's an asymmetry here. Whilst there's an element of compulsion for the young unemployed, there seems no such compulsion upon firms to retain young workers when the subsidy runs out.

Which is no accident. I suspect that this scheme is much like the unlamented YTS of the 1980s - a way for employers to get subsidized cheap labour. But then, it has long been the case that one function of the state in capitalist society is to act as a human resources department, ensuring a supply of cheap and malleable workers.

Another thing: for some more serious ideas of what to do about youth unemployment, check the work of David Bell, such as this.

November 24, 2011

Class and confidence

Self-confidence plays an important role in depressing social mobility. That's the message of this new paper:

Even small differences in initial confidence can result in diverging patterns of human capital accumulation between otherwise identical individuals. As long as initial differences in the level of self-confidence are correlated with the socioeconomic background [which they are]…self-confidence turns out to be a channel through which education and earnings inequalities are transmitted across generations.

The gist of their thinking is straightforward. Say you have two people of equal cognitive skills, but one is over-confident about his ability and the other under-confident. The over-confident one is more likely to stick with a subject during the early steep phase of the learning curve - believing that "I can master this if only I apply myself" - whereas his under-confident is likely to give up, thinking the material too difficult for him. Alternatively, the over-confident student might choose "difficult" academic subjects at high school, which qualify him for entry to some elite universities, whilst the less confident one would choose less academic subjects which disqualify him.

Important and powerful as these are, they are not the only ways in which class differences in confidence can affect outcomes. There's also:

- Overconfident people might select into occupations where there's a high pay-off to the lowish probability of success, such as management, law journalism or politics. Less confident folk, under-estimating their chances, might prefer occupations which yield less skewed rewards.

- People misperceive overconfidence as actual ability. The overconfident job candidate is thus more likely to get the job than the more rational one.

- "Posh white blokes" can - perhaps unwittingly - manipulate the social awkwardness of others for their own advantage, and thus progress at work.

The bottom line here is clear. In a class-divided society, the very notion of meritocracy is incoherent, because merit in the sense of academic achievement or career success might be the product of an overconfidence which is, initially at least, irrational and unjustified.

November 23, 2011

The economic cost of the X Factor

Helen Wright of the Girls Schools Association complains that programmes such as the X Factor are contributing to a "moral abyss". I fear that they might also have unpleasant economic effects.

What I mean is that the X Factor, along with other things such as the massive pay for top footballers and for celebrities such as Katie Price, tempts young people towards winner-take-all careers and away from careers where pay-offs are more certain and less skewed. This encourages them to over-invest in football and singing skills and the pursuit of celebrity and to under-invest in academic work.

This preference is not necessarily irrational. In simple expected utility terms, a 1% chance of getting £2m a year is equal to a 50% chance of getting £40,000. Add to this the greater disutility of jobs with the latter salaries - plus the fact they won't buy you a house - it's easy to see why people might prefer the 1% chance.

However, this preference might be exacerbated by three less rational biases:

- Role model effects. Role models matter because they play upon the availability heuristic. If we see someone like us doing something, we believe that there's a chance we can do it as well. The problem is that if you're from a poor inner-city, you'll probably see more pop stars, footballers and reality show micro-celebs like you than you'll see middle-class professionals. This will bias you towards the former careers and away from the latter.

- Overconfidence. We often over-rate our chances of success. People become pop singers thinking they'll sell millions, not that they'll be embittered club singers scuffling for a £100 gig - even though the odds point to the latter.

- Probability misperception. We over-estimate the likelihood of low probabilities (pdf), which is why we buy (pdf) lottery tickets.

What's more, we know from other work that, especially where "superstar" markets exist, there is at least a possibility of a misallocation of labour; this sort of thing likes behind the decades-old complaints that the City diverts talent away from other occupations such as science or manufacturing.

All of which makes me fear that the X Factor might be contributing to what might be a serious problem, insofar as some young people do neglect their school work in favour of chasing dreams.

November 22, 2011

Fiscal policy & semi-science

What would it take for the Tories to admit that their fiscal plans are failing?

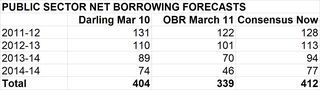

I ask because - despite today's numbers - it looks as if Osborne's austerity could fail even on its own terms, as his plans will not actually reduce borrowing. My table shows the point. The first column shows the PSNB forecasts in Alistair Darling's last Budget. The middle column shows the OBR's March forecast. And the third column shows the current consensus forecast. You can see that whilst Osborne planned to borrow £65bn less than Darling between 2011 and 2015, weaker economic growth means that forecasters now expect that he'll borrow much the same*.

This seems to vindicate Ed Balls' claim that "the danger of too rapid deficit reduction is that it proves counter-productive". Cameron is right to say that cutting the deficit is proving "harder than anyone envisaged" - if by "anyone" he means "anyone in the Tory party."

Why, then, don't the Tories admit they were wrong? They do have some defences, but these are questionable, for example:

"Growth is being depressed by the euro area crisis". However, unemployment was rising before the latest leg of that crisis. Also, the consensus expects growth to be weaker this year because of lower consumer and capital spending, not just lower exports. The consensus now forecasts a drop of 1% in consumer spending this year against the OBR's forecast of a 0.6% rise and a fall of 0.9% in investment against an OBR forecast of 2.3% growth. These two differences take 1.5 percentage points off GDP, whilst the consensus' lower export forecast (5.3% growth vs. 7.9%) takes only 0.75 percentage points off growth. This tells us that something has gone wrong with the domestic economy, and that the euro area isn't entirely to blame.

"Gilt yields are low so the market has faith in our plans." However, spreads between 10 year gilts and their US and German counterparts, at 0.24 and 0.28 percentage points respectively, are within a standard deviation of their post-2001 averages, of 0.29 and 0.53 percentage points. This means it's hard to infer that fiscal policy has led to significantly lower yields. And even if it had, I'm not sure this is a wholly good thing. Yields can be low because markets are pessimistic about growth, not just because they are optimistic about creditworthiness.

"Things would have been even worse under Labour's plan." This is just unobservable. It also runs into the problem that there isn't a massive difference between the two policies. As Fraser says, Osborne's plan is an "only-slightly-modified version of Darling's deficit reduction plan." But it's hard to have it both ways - to claim both that there's little difference between the two policies and that Osborne's plan has made a material difference in preserving market confidence. (Of course, mutatis mutandis this is an embarrassment for Labour as well).

I suspect that arguments like these are what Popper called "immunizing strategies" - they are ways of protecting yourself from admitting you were wrong.

This is not (just) a partisan point; all politicians do something similar. Instead, my point is that policy-making is a semi-science. Like science, it conducts experiments - in the sense of doing things the result of which are unknown. Unlike science, it just doesn't, and cannot, learn from such experiments.

* Of course, the forecasts are subject to huge error margin, but as it's not clear which way these work, I'm not sure this is relevant for our purposes.

November 21, 2011

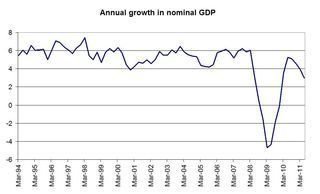

Why governments need growth

My personal income is lower now than it was 20 years ago - in nominal as well as real terms. But I'm happier in my work and life now than I was then. Which poses the question: why do the main political parties regard the threat of stagnation with such fear? Why don't they accept that they have no great ways to materially increase long-run growth - this generally witless collection of proposals highlights the paucity of thinking - and think instead about ways to improve Mill's "art of living"?

The answer, I suspect, is that governments need economic growth, for a mix of reasons:

1. Economic growth is necessary, if not perhaps sufficient, to reduce unemployment.

2. To overcome Baumol's cost disease. The relative cost of government services such as health and education tends to rise over time; this is not (just) because of public sector inefficiency - look at how private school fees have risen - but because of the nature of the beast. Without economic growth, this tendency would generate a rising tax burden and growing tax resistance.

3. To get out of a debt trap. Higher growth allows governments to run looser fiscal stances whilst stabilizing the debt-GDP ratio. It's an alternative to austerity or the embarrassment of monetizing the debt.

4. Economic growth can divert attention away from questions of equality and redistribution. If per capita GDP grows by 2.5% a year then in 25 years time we'll be 85% better off. This means that, ceteris paribus, the minimum wage will be £450 a week - not far shy of the median wage today. The passage of time, then, relieves poverty. If, however, the economy stagnates then poverty relief becomes a zero-sum game; it requires actual redistribution.

5. In a normal growing economy, a government that promises economic growth can take the credit for what probably happens anyway, as a result of private sector decisions.

All of these reasons have something in common. They all suggest that economic growth is helpful in preserving the legitimacy of the state. Sustained mass unemployment can generate riots and crime or - remember the 30s - worse. The higher taxes that points 2, 3 and 4 suggest would accompany stagnation would lead others to suddenly discover their inner libertarian, and would intensify distributional conflicts. And the absence of growth would sharpen the question: what the heck is it that governments do for us anyway?

This is no idle pessimism. The decline of growth rates in the 1970s led to serious talk of a "crisis of democracy" (pdf). Who's to rule out a repeat?

In this sense, I fear some greens under-estimate the trouble which and end of growth would cause.Maybe governments are right to fear stagnation. Which makes it all the more troubling that they can do so little to stop it.

November 20, 2011

What's wrong with positive money?

I was unusually surprised by the reaction to my post on monetary cranks; I thought I was just expressing mainstream economic opinion. I should, then, say what I don't like about the "positive money" scheme.

It proposes that banks be forbidden from creating money by making loans. Instead, only the Bank of England creates money. Bank lending, it says, should come only from the money banks can raise from stock markets, or from customers in the form of "investment accounts" (current account deposits would not be lent on), or from loans from the Bank of England.

This plan reverses the order of lending and deposits. Now, lending creates deposits; if you take out a mortgage to buy my house, my bank deposits rise. Under PM, it is deposits that create lending.

This would cause a fall in lending, relative to the boom times. For example, in 2006, banks created £191.7bn of money - that is M4 lending minus the rise in banks non-deposit liabilities. This was equivalent to 14.5% of the money stock, and was £25bn (15%) more than the rise in bank deposits, M4. And because many of those deposits were in current accounts that PM thinks shouldn't be lent, the actual fall in lending would be greater. PM says:

This reform will reduce the amount of 'credit' – or more accurately, lending – available in the economy, from around 100% of the existing money supply to around 50-60%.

This is potentially deflationary. To remedy this, they propose that the Bank print money and lends to banks.

This leaves us with two possibilities. Either the Bank completely fills the gap, in which case nothing much changes in aggregate. Or it doesn't, in which case lending does fall.

Underpinning the thinking here is the notion that this would be no bad thing, as a lot of lending is speculative rather than productive.

But it's not clear that PM would lead to a squeeze on speculative lending. I fear the opposite would happen. If banks have only a limited amount to lend, they'd surely prefer mortgage lending, which has predictable cash flows which can more easily be matched to the maturity of investment accounts, over corporate lending which tends to be lumpier and less predictable. And they'd prefer to lend to well-collateralized older people buying second homes or buy-to-lets than young first-time buyers. Yes, first-time buyers and firms might get loans, but only at higher rates.

PM thinks this problem can be solved by the Bank of England directing that loans only go to productive activity. But this runs into the classic problem of central planning; why should a central planner (the Bank) know better than individuals what the proper volume and direction of lending is? One virtue of our present system is that it allows individuals who decide how much to borrow and for what and thus makes use of fragmentary, dispersed knowledge about the best amount and direction of lending.

It is not an adequate reply to this that the crisis shows that individuals' judgment is flawed. This crisis did not happen because individual borrowers borrowed too much; loan default rates and bankruptcies have been rather low (individual bankruptcies have risen, but this might reflect legal changes as much as individual distress). Instead, it happened because of poor decisions by individual banks; to be too dependent on wholesale funding in the case of Northern Rock or Bradford & Bingley, or to take over ABN Amro in the case of RBS. These failures, however, could (with hindsight!) have been prevented by policies short of a ban on banks' printing money.

And herein lies my problem with positive money. We just don't need such a radical and potentially dangerous reform. Our banking ills are remediable by other, safer policies:

- Banks tend to take on too much risk? Insist upon higher capital or liquidity requirements.

- There's too much "speculative" mortgage lending? Impose quantitative limits.

- House prices are too high? Build more.

- Banks are socially irresponsible? Nationalize them, with democratic control.

- "Productive" firms are starved of finance? Create a state investment bank.

In this sense, there's nothing that positive money cures that couldn't be cured more easily.

* Another thing. Anyone who is arrogant enough to claim there's a "simple solution" to the crisis, as PM does, is discrediting their case from the start.

November 18, 2011

Authority vs equality

In its obituary of him, the Times says that Peter Roebuck grew disenchanted with England because he thought it lacked the right combination of egalitarianism and authority. This is a really useful way for thinking about the structure of organizations - be they sports teams, companies or whatever - because there are costs and benefits associated with both*.

The benefits of authority are:

A1. It allows for speedy, decisive decisions. Imagine how much time would be wasted if every decision in your firm required a meeting at which every whinger and windbag could vent endlessly. (You might not have to imagine.)

A2. Unilateral authority allows for conflicts of interest to be resolved quickly. It can actually prevent such conflicts, insofar as potential disputants anticipate the boss's ruling.

A3. It economizes on information -gathering. Where there's a single decision-maker, only one person need bother preparing for it. If everyone had to take decisions, huge amounts of time would be devoted to preparing papers for meetings.

A4. It allows for clear feedback, which in turn maximizes opportunities for learning. If a single boss is responsible for a decision, then if it goes wrong he learns something. If, however, a group is responsible, the error leads to buck-passing and arse-covering and so no-one learns. A similar thing is true for underlings. Feedback from a boss is clearer than that from a group; a man cannot serve two masters.

A5. Decision-making skills are like any other - they are not equally distributed. Some folk are better at managing than others, so the division of labour requires that they specialize.

Against this, there are benefits of egalitarianism:

E1. It can curb rent-seeking by opportunistic bosses.

E2. Where authoritarian monitoring is imperfect, it can improve discipline as workers police themselves. Some people have hated working for John Lewis because it's harder to skive when everyone thinks they're your boss.

E3. It can raise productivity as people work harder when they feel they have a stake (pdf) in the outcome or a say in the decision. As Tocqueville wrote, democracy "spreads throughout the body social a restless activity, superabundant force, and energy never found elsewhere."

E4. It can improve decision-making by making better use of the dispersed, fragmentary knowledge of individuals. Also, in authoritarian regimes - be it Fred Goodwin's RBS or Hitler's running of Germany's war effort - leaders are often told what they want to hear rather than what they need to, with sometimes catastrophic effects. Equality prevents this.

The right balance between these will vary from organization to organization. For example, football teams are run on authoritarian lines because A1 and A2 are important whilst E2 is insignificant and E3 - because there are other sources of motivation - is less relevant. A similar thing is true for the army.

I stress the word "balance" here because there needn't be - and rarely are - pure authority and pure egalitarian structures. In authoritarian structures bosses might pay more or less attention to workers or trades unions, thus having varying degrees of equality. And in egalitarian structures (say jury rooms), some individuals will carry more weight than others.

So, how can we tell what is the right balance? Often, it'll be hard. For one thing, simple metrics such as the number of levels in the hierarchy from CEO to shopfloor won't necessarily help; a few rigid levels might carry more costs of authority than more levels accompanied by an egalitarian ethos.

And for another thing, the balance will depend on individuals. If a boss is a genius, the organization can get away with what would otherwise be an inefficient balance of authority and equality; think of Steve Jobs' bullying at Apple.

As you know, I share Roebuck's hunch, that the balance we have is badly skewed, as we exaggerate the importance of A1-A5 and under-estimate that of E1-E4.

* I'm drawing here on Henry Hansmann's The Ownership of Enterprise and Oliver Williamson's Markets and Hierarchies.

November 17, 2011

Living with a weak economy

Hopi writes:

The moderate left is aware that it's fiscal tools to tackle the immediate crisis are horribly limited. The idealist left is uncomfortably aware they don't actually have a plan to offer, other than disbelief at the way things are now. As a result, the right tells the electorate that pain is the only way forward.

This chimes with something I've said - that mass unemployment is here to stay and there's little governments can do to raise growth much.

But this needn't be a defeatist stance. Remember John Stuart Mill:

I cannot…regard the stationary state of capital and wealth with the unaffected aversion so generally manifested towards it by political economists of the old school…

[It] implies no stationary state of human improvement. There would be as much scope as ever for all kinds of mental culture, and moral and social progress; as much room for improving the Art of Living, and much more likelihood of its being improved, when minds ceased to be engrossed by the art of getting on.

Rather than think about growth policies, where politicians have little to offer, we should instead think about policies for "mental culture" - for promoting happiness, if you like. Here are some general principles:

1. Autonomy creates happiness, as well as being a virtue in itself; this is why the self-employed (pdf) and people in direct democracies (pdf) tend to be happier than others. This represents a case for giving people greater control over their working lives - through direct democracy. But it might also suggest that there is a case for some kinds of deregulation, to the extent that this increases autonomy by getting the state off people's backs.

2. Unemployment is a big cause of unhappiness (pdf). This suggests that whilst there might not be much politicians can do to reduce aggregate unemployment, there is a case for proper active labour market policies, to ensure that the unemployed are as quickly matched to vacancies as possible. This does not, however, entail stigmatizing the unemployed as workshy. Quite the opposite. Given that unemployment is here to stay, it's a good thing that some don't want to work.

3. Social capital - trust and friendship (pdf) - also promote happiness. Although it's not obvious that government policies can help people make friends, they might be able to promote trust, insofar as they demonstrate that we really are "all in this together." Such policies might include a crackdown upon perceived rip-offs such as bankers' bonuses and utility pricing.

So much for "big think" principles. But there might be a different way of coming at this, by using the Dave Brailsford principle of the aggregation of marginal gains. Maybe policies to improve the "art of living" don't consist merely of top-down grand ideas, but also of many small things. Richard Layard has proposed (pdf) putting a higher priority upon mental health on the grounds that lifting the minority of people with acute depression out of their misery makes a good difference to aggregate well-being. I'd add that more should be done to encourage the growth of allotments, on the grounds that this would give people the chance of getting the "flow" happiness that comes from self-directed productive work.

Hopefully, more imaginative folk than I can think of other apparently tiny things that, together, add up to something big. And maybe these initiatives don't require central government at all, but can be undertaken by local authorities, voluntary groups or just groups of individuals. In which case we should wonder what use national politicians are.

November 16, 2011

Monetary cranks vs Jessie J

One effect of the crisis has been to revive that ancient beast, the monetary crank - the sort of person who thinks our economic ills can be cured simply by a reform of the monetary system. Ben Dyson illustrates this beautifully when he says that "a very simple solution to the financial crisis" would be to ban banks from creating "electronic money."

The point here is not that this is a left-wing proposal; you can find complaints about fractional reserve banking on the rococo fringes of the right. Nor is the point that it is gibbering idiocy - though it is.

Rather, the point is that this is old idiocy. It goes back through C.H. Douglas (pdf) and William Jennings Bryan and further. As David Clark wrote in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics:

Any explanation of the appeal of these ideas over generations would have to invoke sociology and psychology. Such ideas found strong support because they enabled persons to impress their peers with their apparent understanding economics, even though they had no formal training in the discipline. They offered the false hope that there were simple solutions to the complexities of modern economic life. They also transcended party allegiances - similar passages about "credit slavery" and "Shylocks" can be found in Hitler's Mein Kampf and left-wing pamphlets of the same era…"Funny money" beliefs provided a kind of ideological relief valve.

These beliefs they fly in the face of both neoclassical and Marxist economics, both of which downplay the role of money. To Marx, money was a veil which hid the real fact of workers' exploitation. And in a lot of neoclassical economics money plays little role. Early general equilibrium models got by without it at all - consistent with the "classical dichotomy" which says that, in the long-run, money affects only nominal variables (the price level) rather than real aggregate ones such as output. Yes, monetary disturbances might have real effects in the short run, but these can be corrected by orthodox monetary policy - not that it's obvious (pdf) that monetary policy needs money.

This dichotomy matters. The crisis we're in is a real phenomenon, not a monetary one:

- Debt is a real phenomenon. Debtors - government or private - have incurred a real obligation, to transfer some of their future incomes to creditors. The problem for Greece and for over-burdened households is that these real obligations are more onerous than they anticipated. That's a real problem. Yes, debt can be reduced by inflation - printing money. But this is just a backdoor way of achieving a redistribution of real resources away from creditors and towards debtors.

- Banks' misjudgements of risks - whether they arose from stupidity or from misaligned incentives - were real mistakes, not monetary ones.

- Banks' current reluctance to lend, and companies' reluctance to borrow, are also real things. The reflect genuine pessimism about future real output and hence the viability of the real obligations that debt represents.

- The sharp slowdown in UK productivity and the dearth of investment opportunities are real phenomena.

Now, I don't want to overstate the case here and completely deny a role for money. I'll concede that money illusion might have played a role in causing households to over-estimate house price returns and so over-accumulate mortgage debt. And I'll even concede that quantitative easing can have small real effects. But the point is that our problems are real ones which do not have simple solutions, and there is little that money can do about them.To quote her out of context, Jessie J got it right: "It's not about the money, money, money."

November 15, 2011

A closet NGDP targeter?

In his letter to the Chancellor, Sir Mervyn says (pdf) "it is…possible that inflation could fall back more sharply given the existing margin of spare capacity in the economy."

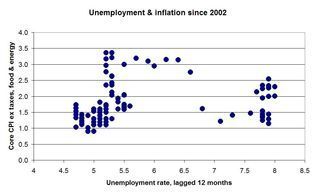

That word "possible" is doing quite a bit of work. My chart shows why. It plots core inflation (excluding energy, unprocessed food and taxes) against the unemployment rate, lagged 12 months, since 2002. If spare capacity tended to push inflation down, you'd expect to see an orthodox downward-sloping Phillips curve. But you don't. Instead, it looks as if there are two vertical curves. There the 2002-07 one, which saw unemployment around 5.3 per cent, and there's a post-2008 one, with unemployment around 8 per cent.

The data seems more consistent with the Nairu increasing in the crisis, rather than with spare capacity depressing inflation.

After all, we've had high unemployment for two years now, and yet core inflation, at 2.2 per cent on this measure, is above its 10-year average.

What's going on here? I suggest three elements:

1. There's a mismatch between spare capacity and demand. In Arnold's terms, the patterns of sustainable specialization and trade have been jumbled up. A newly unemployed civil servant in London, for example, cannot easily become an engineer in Aberdeen. Unemployment can therefore exist alongside rising cost pressures in some sectors.

2. The financial crisis was a supply shock. To see what I mean, consider why spare capacity should bear down on inflation. One reason is that it makes markets more contestable. Spare capacity enables a firm to expand quickly and cheaply. It thus encourages firms to cut prices in order to win more orders. Alternatively, it compels firms to hold prices down in order not to be undercut by potential rivals. But what if firms can't get the finance to expand or - what is overlooked - are unwilling to borrow for fear that the credit line might be later withdrawn? In this case, spare capacity won't encourage expansion and thus won't encourage price cuts.

3. Price wars are cyclical. In a famous paper (pdf) written in 1986, Julio Rotemberg and Garth Saloner showed that price wars were more likely in booms than slumps. The time to cut prices is when there are lots of customers to be won - and this is not in a recession.

If all this is right, then we shouldn't expect core inflation to collapse. Yes, overall inflation will drop for mathematical reasons as last winter's rises in VAT, food and petrol prices drop out of the comparison. But perhaps inflation will stay above target*. There is a middle way between the gold bugs who somehow think QE will be hugely inflationary and the agg demanders who expect inflation to slump.

All of which raises a question. If spare capacity isn't very disinflation, why does the Bank seem to think otherwise?

Here's a thought. Believing that a weak economy leads to significantly lower inflation allows you to relax monetary policy substantially whilst claiming to stick to inflation targets. But in fact, what you are really doing is targeting real economic growth instead. Maybe the Bank has been a closet nominal GDP targeter all along. After all, this - more than inflation - justified its superloose policy in 2008-09 and its recent resumption of QE.

* A caveat here is that the spare capacity might exist within firms, because of labour hoarding, and so not show up as unemployment.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers