Chris Dillow's Blog, page 189

December 18, 2011

What does religion do?

David Cameron's call to "stand up" for Christian values has led to the sort of fact-free posturing that religious debate usually provides. It confirms my prejudice that when someone says "I (don't) believe in God", the emphasis is entirely on the "I".

But there is an alternative reaction. We can ask: what are the practical, social effects of religion?

It is, of course, trite to say that one can be "good" without being religious. As Ken Binmore, among others, has shown, moral codes - reciprocal altruism - can emerge from natural selection, without invoking God.

Nevertheless, it is a legitimate question of social science to ask if the behaviour of the religious differs, on average, from that of the non-religious.

And there is evidence for this. A laboratory experiment has found that Christians are more likely than atheists to trust other Christians, and to justify this trust by behaving more trustworthily - though other research suggests such an effect might be confined to more liberal denominations. This needn't mean that Christians are inherently morally better than us; it might be an example of stereotype threat, the tendency of people to live up or down to their stereotype.

But here's a thing. We know that trust is good for an economy, because it helps overcome problems of incomplete contracts and markets for lemons; as Rabbi Jonathan Sacks said recently:

Try running a bank, a business or an economy in the absence of confidence and trust and you will know it can't be done.

Which raises the question: could it be that religious attitudes promote economic growth?

Yes - to some degree. A paper (pdf) by Luigi Giuso, Paola Sapienza and Luigi Zingales concludes:

We found on average that religion is good for the development of attitudes that are conducive to economic growth…

On average, Christian religions are more positively associated with attitudes that are conducive to economic growth, while Islam is negatively associated.

Not just Christian, though. Some economists have found that, among Buddhist Tibetan herders, religiosity is associated (pdf) with higher individual incomes.

It does not follow, however, that religion's effects are wholly benign. Religiosity is strongly correlated (pdf) with gender inequality,and Giuso's paper found that (on average) "religious people are more intolerant."

All of which raises a paradox. From the point of view of this liberal atheist, the practical effect of religious belief is the exact opposite of what people, including Cameron, suppose it to be. Whilst its moral effects are, I think, to be regretted in many ways, its economic effects are more benign.

December 16, 2011

Irrelevant politicians

One aspect of the euro area's debt crisis that hasn't had the attention it deserves is that it might accelerate the decline into irrelevance of the political class.

What I mean is that financial markets have more or less given up hope that politicians will solve the problem. Insofar as they still hope that the crisis will be resolved, such hopes lie in the expectation that the ECB, rather than politicians, will act. All Europe's "leaders" - the word is increasingly absurd - can offer is mindless slogans.

In other words, the political class seems unable to solve problems that are - in principle - soluble; I suspect one could add global climate change to this. And if they can't solve the soluble problems, there's no chance of them solving insoluble ones, such as what to do about the investment dearth, or how to create full employment when demand for unskilled workers is in secular decline in the west; feel free to add to the list.

What policy announcements that are made - such as Cameron's promise to do something about "troubled families" - usually have more to do with news management than the serious expectation that problems can be solved.

Politicians are becoming meaningless people doing meaningless posturing.

This continues a longstanding one. For years, voters have increasingly recognized politicians superfluousness by not voting. Since the 70s, turnout in parliamentary elections has declined from over 80% in Germany to under 65% at the last election, from 70%+ in France to under 44%, from over 90% in Italy to under 80%, and from 70%+ to 61% in the UK. I suspect that these numbers are only as high as they are because of a combination of force of habit and the desire to self-identify with a faction, rather than our of any expectation that politicians matter much.

One reason why "technocrats" have been able to take charge in Italy and Greece is precisely that orthodox politicians no longer offer much.

I suspect that politicians recognize this only instinctively. One reason for the increasing bitterness of political disputes - be it the vicious factionalism of much of American politics, Francois Baroin's absurd swipe at the UK or the Europhiles attacks on the Eurosceptics - is that impotence and irrelevance makes people angry. National politics is becoming like academic politics; it's so vicious because the stakes are so low.

Though they see it instinctively, however, at least three things - on top of their self-regard and self-importance - stop politicians seeing it intellectually.

One is simple self-denial. This post at Labour List gives a good example of this. It draws five lessons of the Feltham and Heston by-election without noting the important one - that seven in ten people didn't vote. Instead, the low turnout is brushed off as something "invariable" rather than as what it is - a large and growing indifference to politicians.

Another is that the media continues to give politicians more attention than their social impact would warrant. Politicians mistake this attention for public interest, when in fact the media is another faction of the political class.

There's a third thing. People confuse politics and politicians. Politics - the question of how public life should be conducted - will always matter. But it does not follow that politicians matter - especially when they have only narrow and inadequate answers to this question.

December 15, 2011

The dark side of sport

Exercise is good for you. A new paper by Andrew Clark shows that children who play sport go on to get better jobs and earn more. This corroborates earlier research by Michael Lechner.

Why? The standard answer is that sport either inculcates or reveals useful non-cognitive skills: teamwork, discipline and so on. Mens sana in corpore sano as they said in the old public schools, and probably still do.

There might, however, be a darker side to sportier people's higher earnings, which Jeremy Celse of the University of Montpellier points out in a recent paper (pdf).

He ran a simple experiment in which pairs of subjects were given small sums of money, with the subjects then told how much their counterpart had received. He found that people who played sport were almost twice as likely as non-sportsmen to say they were unhappy when they learnt that their counterpart had received more. "Practicing a sport increases significantly the probability for a subject to report a decrease in his satisfaction after being exposed to unflattering social comparisons" he says.

What's more, sporting people were almost twice as likely to cut their partner's gift, even at the expense of making themselves worse off.

This hints at a dark side of sport. It is, generally, a zero-sum game, with winners and losers. Sportsmen transfer this mindset into other aspects of life. They are therefore more likely to feel bad when they compare themselves to others, as they feel like losers. To avoid this feeling, they take measures which might hurt themseleves. This happens even in cases, such as Mr Celse's experiment, where everyone is in fact a winner, in the sense of being better off than they were before.

Herein lies a worry. It could be that sporting people's higher earnings arise not merely from their positive non-cognitive skills, but from these darker impulses. Not only does their desire to avoid feeling like a loser spurs them to work harder, but - worse still - they'll be more prepared to hurt others in order to avoid that feeling. They thus have the sharper elbows necessary to climb greasy poles (is this a mixed metaphor). As Gore Vidal (a quarterback at West Point) said, "it is not enough to succeed; others must fail."

It is, I suspect, no accident that a lot of prominent US business people were active sportspeople in their youth.

December 14, 2011

Jobs, uncertainty & ideology

What has happened to employment? The official figures seem clear. In the three months to October, it fell by 63,000 and unemployment rose by 128,000.

This does NOT mean that 63,000 people lost their jobs in the latest three months or that 128,000 became unemployed. These refer to net changes, which are much smaller than gross ones. The ONS's experimental data show that, in Q3, 903,000 people left employment: 513,000 entered economic inactivity (say because they retired) and 390,000 entered unemployment.

Even this net change, though, is only an estimate. It's drawn from a survey with large sampling error. The ONS says that the 95% confidence interval around its estimated change in employment is 134,000. This means there's a 95% chance that the net change in employment was somewhere between minus 197,000 and plus 71,000.

This, though, is not the only evidence we have about jobs. There's also a measure based on a survey of employers, rather than individuals. This shows that jobs increased by a net 150,000 between June and September; there are about 30 reasons why the two measures diverge.

And there is sampling error around this as well - though the ONS, with its infinite capacity to infuriate the hell out of us, says there is "no on-going measure" of how big this is.

The picture here, then, is murky. The worst case reading of the numbers is that the labour market is doing terribly; 197,000 is almost 0.7% of all employment. The best case is that jobs are (net) being created. Taken on their own - which they are not and should not be - today's numbers are consistent either with the view that macroeconomic policy is far too tight and is causing a disastrous fall in employment, or with the view that it is about right and in consistent with rising employment.

This confirms what all economic forecasters have known along. Not only do we not know where we're going, we don't even know where we are.

In one sense, this uncertainty doesn't matter as much as you might think. Lots of good policies do not depend upon noisy quarterly moves in jobs. The merits or not of tax and welfare policies, supply-side changes or active labour market policies can be considered independently of these uncertain data.

In another sense, though, this uncertainty does matter. Because the media almost never discuss it - see for example these otherwise reasonable write-ups of the figures - they give the impression that hard knowledge of the economy is possible when in fact it is not. They mistake precision for accuracy. And this serves a nasty ideological function. It helps to increase the credibility of those politicians, technocrats and cranks who claim to possess precise knowledge of the macroeconomic present and future when such knowledge is in fact elusive.

December 13, 2011

Why defend the CIty?

How fungible are high-earning workers? This is the question posed by David Cameron's attempt - which might not succeed - to defend the City against the EU.

To see what I mean, let's assume that regulations did force the City to shrink, causing some highly-paid people to lose their jobs. How big a loss would this be? There are two extreme possibilities:

1. Those workers would remain unemployed, so the loss to the economy would be equal to their lost earnings.

2. Those workers are highly skilled and could find employment elsewhere, or set up their own businesses. In this case, the loss to the economy would be equal to the difference between their earnings in their first-best occupation (the City) and their earnings in their second-best - whatever other jobs they do. Such a loss is likely to be small. Put it this way. Financial intermediation in London accounts for just over 4% (pdf) of GDP; this exaggerates the contribution of the City as it includes bank tellers in Acton as well as genuine City workers. This means that if the City shrinks by half - and I know of no estimate as high as this - and workers lose half their income in moving to other jobs, we'll lose 1% of GDP.

The contrast between these two positions is, of course, not confined to the debate about the City. Samuel Brittan has long argued against subsidizing jobs in the arms industry on the grounds that workers who lose their jobs if the sector shrinks would be re-employed elsewhere. To obsess about protecting jobs in a particular industry is, he says, to commit the lump of labour fallacy.

How, then, can one believe that lost jobs in the City would be a big problem? One possibility is that City workers owe their high earnings to job-specific human capital or to organizational capital that would be lost if they changed industry, and so they would suffer a big loss of earnings*.

But even if this is true, couldn't such losses be offset - at the macro level - by increasing employment by using orthodox expansionary monetary or fiscal policy?

Herein, though, lies a curiosity. When miners were threatened with pit closure in the 80s, the Tories believed argument (2) over argument (1). And when they cut public sector jobs, they also believed - maybe they still do - in argument (2), thinking that public sector workers would find private sector employment. However, when they consider City workers, they seem to believe in argument (1). Miners and civil servants, it seems, are fungible, but City workers aren't.

Which is really queer. If City workers really are so much more skilled, ingenious and industrious than idle civil servants and beer-swilling bolshy miners, shouldn't they find it easier to get well-paid work elsewhere?

It seems, then, that the Tories are being a little inconsistent.

The kindest interpretation of this is that they are so averse even to second-order temporary losses of GDP that they are prepared to jeopardize our relations with Europe to avoid them. There are, though, less generous possibilities.

* In fact, it's more likely that those high earnings are due in part to an implicit tax-payer subsidy and to an un- or under-priced externality - the fact that the City imposes the risk of financial crisis and recession onto the wider economy. Taking this into account, however, merely makes Cameron's position even more indefensible.

December 12, 2011

Leona Lewis, capitalism and the state

The most significant political event of the weekend was, of course, Leona Lewis's cover version of "Hurt" on the X Factor. This perfectly demonstrated Frederic Jameson's point that the dominant cultural form of late capitalism is pastiche - the soulless imitation of past achievements, devoid of conviction*. "Speech in a dead language" as he called it (pdf).

This pastiche arises from what we might call a contradiction of capitalism. On the one hand, growth and profitability requires that culture be commodified. For capitalists, it is useless if we merely contemplate past artistic accomplishments. We must instead buy new ones. On the other hand, though, capitalism is unable or unwilling to innovate, as the benefits of such innovation cannot be reliably captured**. This tension leads capitalists to regard the past not as part of a living tradition or of a union between past and present, but as a dressing up box from which one picks garments in the expectation they'll please some passing whim of the market.

There's also an ideological trick being played here. In downgrading tradition, capitalists reinforce their own power. The question: "Is this good work by the standards of a musical tradition?" becomes unaskable, and is replaced by "does this work please record company bosses?"

It's from this perspective that Ms Lewis is so significant. What we saw from her was a microcosm of what Harry Braverman described in Labour and Monopoly Capital - a destruction of craft traditions and standards which paves the way for an increased power of bosses.

Which brings me to Libby Purves in the Times today. She bemoans the "exam scandal", in which kids are drilled in "bite-sized, tick box knowledge" so they can "pick out the four official facts about, say, Macbeth".

What we see here is exactly what we saw with Ms Lewis. Just as she - or more accurately her corporate bosses - rip music from its tradition and present it in sanitized, approved form, so examiners do the same to literature.

In this way, state education serves the interests of capital, in a two-fold sense. In making education a "joyless obstacle course", it prepares children for the mindless drudgery of work. And in effacing tradition, it prepares them for decontextualized consumption. Schools, then, are - as Althusser said - ideological state apparatuses.

* Yes, I know Johnny Cash's version was a cover. The difference is that he put meaning into the song, whereas Ms Lewis took it out.

** Yes, in practice capitalism has produced innovations. But I suspect that many of these have been the result of an overconfident expectation of profit. If people were entirely rational, we'd have much less innovation.

December 11, 2011

Big government & equality

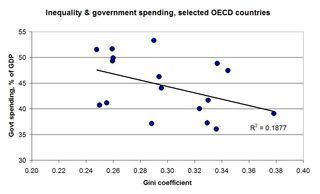

Richard Exell poses the question: can fiscal conservatives reduce inequality?

Maybe. For one thing, it is possible to make the tax system more progressive, for example through a progressive consumption tax, land taxes or inheritance tax. And we shouldn't rule out the possibility of very high top tax rates. It's also possible to both shrink the state and increase equality by cutting corporate welfare - handouts to the likes of BAe Systems, Serco, Capita, CSC and A4E.

There is, though, something else. My chart shows that the correlation between big government and equality is weak. Yes, countries with big government spending tend to be more equal, but there's a lot of variation around this. For example, France and Norway have similar levels of equality, but France spends 13 percentage points more of GDP. And the UK has the same inequality as Australia or Japan, but spends 10 percentage points more of GDP.

In fact, it could be that the positive correlation between equality and public spending doesn't reflect causality from the latter to the former at all, but rather an omitted variable. Countries that combine big government and equality tend to be high trust societies. It could be, then, that the same high trust that makes people supportive of redistribution - because they believe "welfare scroungers" aren't ripping them off - also makes them support big government as they trust politicians not to waste money.

This possibility hints at another - that perhaps it's possible to combine small government and equality if the right cultural or institutional factors are in place. I mean, for example:

- Strong trades unions. These not only raise the pay of the worst off, but also help restrain top pay.

- A collectivist culture. A society that believes that corporate performance depends upon the abilities of all its employees will be more egalitarian than one which believes that organizations can be transformed by star managers.

- Education. A highly educated workforce might be more equal, if only because it creates more competition for top jobs. There is a correlation between education levels (pdf) and equality - the egalitarian Nordics do better than the inegalitarian US and latin Americans. And the causality mightn't be entirely from inequality to poor education. However, high educational standards are achieved not by increased spending, but by a culture which values schooling - and the UK lacks this.

Herein, I fear, lies the big challenge for the Left. Although it is technically possible to reconcile small government or fiscal conservatism with greater equality, the UK lacks the cultural underpinnings which would permit this happy combination.

December 10, 2011

Unions vs legislation

We need stronger trades unions. This is my reaction to the calls at Left Foot Forward for a "living wage."

I say so because union bargaining strength is a better way of raising wages than legislation. This is because minimum wage laws are inflexible. They apply both to cash-rich firms that could raise wages without cutting jobs and investment, and to firms on the margin of profitability that would close down if labour costs rose. (Yes, the left exaggerates the prevalence of the former just as the right exaggerates that of the latter.) Living wage laws can't distinguish between these cases. But union bargaining can. Strong trades unions, then, are better able than laws to raise wages without job loss.

The same is true for other forms of labour regulation: health and safety, working time and suchlike. Union bargaining can protect workers more flexibly than "one size fits all" laws. It can distinguish between cases where regulation would be too costly and where it wouldn't.

In this sense, legislation and unions are alternatives. It is no accident that the UK introduced minimum wage laws in 1999, after trades unions were weakened, and that this weakness has been followed by more "red tape" on firms.

A paper by Philippe Aghion and colleagues formalizes this. They point out that there is a negative correlation between union strength and minimum wage laws. Scandinavian countries have traditionally had strong unions but little wage legislation, whilst Greece, France and Spain have weaker unions but tighter minimum wages. And which countries have usually had the healthier labour markets?

This is not to say that unions are a panacea. The problem with them is not so much the Thatcherite-Hayekian one that the undermine the rule of law - given the inflexibility of the law, this is a benefit of them, not a cost. It is that, in the UK, traditionally, unions were better at advancing the interests of skilled and semi-skilled workers than the most disadvantaged ones; they heyday of unions was not a great time for black or female workers.

What I am saying, though, is that we lost something valuable when unions declined. Worse still, as Aghion and colleagues point out, we might not get it back, because legislation crowds out the cooperation and self-reliance that produces healthy unions.

Herein, though, lies a paradox. Logically, one might imagine that Conservatives especially would lament the decline of unions. They represent self-help and a flexible, non-statist alternative to the heavy hand of government intervention - the "Big Society". And yet this sentiment is absent. It's enough to make one suspect that the Tories' only principle is a pig-headed hostility to working people.

December 9, 2011

Left, right & the euro

Varun Chandra's post raises a question: could it be that, in Britain at least, the left and right's attitudes to the euro are the wrong way round?

To see what I mean, imagine - which is not certain - that we eventually get a short-term fix for the debt crisis, whereby the fiscal compact (pdf) finally causes the ECB to buy sufficient bonds to reduce yields. (Nobody other than Lutheran masochists seriously thinks that fiscal restraint alone is sufficient). Even if we get this fix, the longer-term problem remains: how will southern European nations be able to grow, given that they are lumbered with both over-valued currencies and fiscal constraint?

One possibility, and the reason why technocrats have taken charge of Greece and Italy, lies in supply-side reforms. Relaxing employment protection and reforming public sectors might allow the private sector to grow.

And it's here that left and right attitudes are the wrong way round.

A standard rightist answer here might be: "fiscal policy was always a weak tool anyway, and supply-side policies do raise growth, so maybe the euro can survive." Leftists, by contrast, think the end of activist fiscal policy is a serious loss but are sceptical about supply-side policies, so they should be more pessimistic about the euro's chances of survival.

But this is not how things actually are. The noisiest forecasts of the euro's failure come from the right, whilst the left are generally either silent or more confident of its survival. This is the mirror image of what one might expect. Why the difference?

One possibility is that the right's elasticity optimism causes it to believe that floating exchange rates are a good and powerful thing, whilst the left's scepticism about the efficacy of free markets leads it to deny this and accept the feasibility of a single currency. Another possibility - which I'm less sure about - is that the right has valued national sovereignty more highly than the left and so thought its loss more grievous.

These factors might have been pretty much the limit of the British left and right attitudes to the euro for a long time. But they no longer are. I suspect, therefore, that the British left might - and should - therefore become increasingly sceptical about the viability of the euro in the long-run, even if it does survive in the short-term. Whether anyone gives a damn about the opinion of the British left on this issue is, though, another matter.

December 8, 2011

Narcissists against freedom

Take four recent developments:

- Joey Barton provokes "fury" by saying that suicide is selfish, with some of his critics invoking the weasel work "inappropriate".

- Over 30,000 people complain to the BBC about Jeremy Clarkson's "shoot the strikers" comment.

- Luis Suarez gives Fulham fans the finger, and they faint like Victorian spinsters.

- Emma West has to spend Christmas in prison, supposedly for her own safety after she gets death threats for her racist rant.

These events all tell us something sad about the British people - that many of us have become illiberal prigs, quick to take offence and to condemn. I suspect there are three related pathologies underlying this:

1. Narcissism. Events are interpreted through a me, me, me prism. They give us the opportunity to demonstrate our delicate sensibilities and our "moral compass." This approach excludes curiosity. It stops us asking: "why did s/he do that?" (The answers are, in order, because: he's got a point; he's got a book to sell; he's been abused for the last hour; she's probably mentally ill.) We are all newspaper columnists now - in the sense of having a self-absorbed moralistic incuriosity.

2. Infantilism. We have become like children, desperate to seek protection against things that upset us. We've lost Samuel Johnson's manly attitude to freedom: "Every man has a right to utter what he thinks truth, and every other man has a right to knock him down for it." Instead, we now look to the "authorities" to knock him down.

3. A hatred of disorder. Richard Sennett has described how people respond to chaos and uncertainty by constructing a "purified identity". Instead of embracing uncertainty and learning from it, "threatening or painful dissonances are warded off to preserve intact a clear and articulated image of oneself." This warding off consists of demanding that dissonant experiences be suppressed.

I say all this for a reason. When I said yesterday that the public's hostility to redistribution was due to cognitive biases, some rightists replied that this was typical lefty arrogance. But what they ignore is that public attitudes are also hostile to liberty too. For me, both are a matter for regret.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers