Chris Dillow's Blog, page 186

January 31, 2012

The macroeconomics of vajazzles

The Sun says:

Fans of The Only Way Is Essex have led a £1.4billion high street bonanza.

False nails and lashes, fake tans, vajazzles, white stilettos and watches have boomed as shoppers copy Amy Childs and her TOWIE pals….

The "TOWIE effect" is having a bigger impact than the Duchess of Cambridge — because men are also buying into it. The Sun told this month how women were spending an average £250 each on clothes, shoes and jewellery like Kate's — boosting the economy by £1billion.

Is this true? There's a good reason to think not. This sort of story is the kind of anecdotal evidence that Jonathan Portes warned us against. Anecdotes might tell us that spending on vajazzle has increased. But this doesn't necessarily mean the aggregate economy has received a boost. If women are spending more on vajazzles it could be because they are spending less on other things. If so, TOWIE has caused a change in the pattern of demand, but no boost to the economy overall.

Macroeconomic data can't help us here. £1.4bn is only 0.15% of annual consumer spending, and so is lost in the margins of measurement error. And anyway, we can't observe two otherwise identical economies, one with TOWIE and one without.

You might think the answer to the question is obvious. Entrepreneurship is good for economic growth. The invention of the vajazzle is entrepreneurship. Therefore, the vajazzle is good for growth.

Not necessarily. Pamela Mueller has shown that, in both the UK and Germany, the formation of new businesses, at least in poor areas, can actually reduce overall employment as it displaces more jobs than it creates; the destruction bit of creative destruction outweighs the creative bit. This echoes Ricardo's opinion of another form of entrepreneurship, mechanization:

I am convinced, that the substitution of machinery for human labour, is often very injurious to the interests of the class of labourers.

You might object here that these are merely temporary effects and that unemployment should lead to lower wages and thus more jobs.

Not necessarily. From a macro perspective wage cuts mean lower consumer spending which impedes job creation. And from a micro perspective, gift exchange and efficiency wage models tell us that wage cuts are accompanied by lower actual or perceived productivity and hence no more hiring.

So, how can entrepreneurship of the sort that gave us the vajazzle boost growth?

One way it might do so is if spending on vajazzles increases aggregate consumer spending - say, if women reduce their savings or borrow more to pay for the vajazzle. Another way would be if policy-makers respond to job losses in non-vajazzle industries by cutting interest rates and thus boosting growth.

Either way, the vajazzle only boost the economy insofar as financial or monetary conditions permit. In a well-functioning economy, this will be the case. But the point is that entrepreneurship alone is not sufficient for growth.

January 30, 2012

The "scarce talent" con

The standard argument for CEOs' high pay, especially in banking, is that it reflects the scarcity of managerial talent. Robert Peston says: "the knowledge and talents required of someone running a bank as huge and complicated as RBS are not possessed by many." And Dan Davies tweeted that there are less than a dozen people worldwide who know to sell off toxic assets.

The simple laws of supply and demand thus require that bosses be highly paid, don't they?

Not necessarily.

Let's concede that the premise is right - that there are very few people able to run such complex organizations. This just raises the question: who made banks so complex in the first place?

The answer is: bosses themselves (collectively). Bosses who argue that the complexity of banks means that management talent is scarce and must be highly rewarded are like the boy who murders his parents and asks for leniency on the grounds that he's an orphan. They are confusing cause and effect.

Bank bosses have played a trick which countless ordinary workers do. The IT support guy who introduces lots of "security features" to his firm's IT systems, or the secretary who has an incomprehensible filing system, make themselves indispensable by inconveniencing others.

In the old days of banking's 3-5-4 model (borrow at 3%, lend at 5%, be on the golf course at 4 o'clock) bank bosses were well paid but not astronomically so. It's management's own introduction of complexity that has enabled their pay to soar. And whether this complexity is a social good or not is, to say the least, debateable.

Supply and demand are not natural, exogenous phenomena. They are social and ideological constructs. And bosses have constructed them to their own advantage.

Think of this another way. A Soviet communist official once asked Paul Seabright who was in charge of the bread supply to London, and was astonished at the answer "nobody" (or everybody). But imagine if there were such an official in charge. His job would be very complicated, and hugely pressured. Only a handful of people would have the knowledge and the talents to do it.

Does it follow that it would then be right to pay such an official a massive salary?

No, because there's an alternative way of arranging the bread supply.

And a similar thing might be true for management jobs. The assertion that bosses must be paid a fortune because their jobs are so difficult begs the question in the true sense of the phrase; it assumes that the jobs have to be so complex when this premise should be questioned.

Now, you might object here that I am conflating two things: bosses' pay generally, and that of individual bosses. Individual bosses must manage companies as they actually exist, not as they might exist.

True. If I were Chancellor, I would tell Hester that his job is to simplify RBS in such a way that it could be managed by people of moderate ability who wouldn't need huge salaries. The problem is that bosses face insufficient pressures to do this.

January 29, 2012

Overconfidence bubbles

Does the irrationality of the ruling class feed on itself? I ask because of a new paper which points out that happier people tend to be more overconfident than others - as long as they are unaware that the source of their happiness is irrelevant to the task in hand.

This raises a possibility - that overconfidence can feed on itself, with the result that people who climb to "top jobs" are even more overconfident than others.

I'm thinking of several mechanisms here. They start from the fact that overconfident people are more likely to get promotion than others because they send out competence cues that fool others into believing they are better than they are. Having won one promotion, though, the overconfident individual becomes more overconfident. This is partly because getting the promotion reinforces his high opinion of himself, but also because the better job increases his happiness and hence his overconfidence - a fact reinforced by the positive correlation (pdf) between income and happiness among individuals.

And when the individual "rises" to a certain level, these mechanisms will be reinforced by others. His subordinates will support his decisions - partly out of deference and partly because the boss selects them himself - thus further bolstering overconfidence. And we might add, following Nick Cohen, censorship, self-censorship and deference in the media will further increase his positive self-image.

In these sense, just as there can be bubbles in share prices so too can there be bubbles in individuals' self-confidence, because of positive feedback effects.

Now, you might reply here: won't these bubbles eventually get burst as incompetent but overconfident decision-makers get things wrong?

Not necessarily, for two reasons.

One is luck. Even if a decision-maker is no more likely to get decisions right than random chance, dumb luck will cause some to have successful streaks which will further inflate their self-confidence. This is especially likely if those decisions concern tail risk - that is, they consist of taking bets which have a high probability of yielding small positive pay-offs but with the small chance of catastrophe.

Secondly, rulers have immunizing strategies to protect their self-regard. Be it David Cameron blaming poor UK growth upon the euro crisis or Tesco boss Philip Clarke blaming the "challenging economic environment", they have endless excuses for not acknowledging their mediocrity.

In this sense, perhaps our rulers - bosses and politicians - live in a bubble. I don't just mean in Charles Murray's sense of having different backgrounds and lifestyles from others, important as that is. I mean that they are in a bubble of irrational overconfidence about their ability to control complex organizations and societies.

January 28, 2012

Macro amateurs, micro geniuses?

Simon Wren-Lewis says the coalition's austerity is a "major macroeconomic policy error."

It's difficult to imagine the government ever acknowledging this. On Wednesday, Cameron resorted to immunizing strategies such as blaming the euro crisis (without noting that exports to the euro area have risen by 11.3% in the last 12 months), or celebrating the "lowest interest rates for a hundred years", oblivious to the fact that these are a sign of economic weakness. I suspect that even if the GDP numbers had been much worse, he'd have used similar arguments.

Macroeconomic policy, then, is not only made by rank amateurs - not one of the five Treasury ministers in the Commons has a postgraduate qualification in economics and only one has significant experience in financial work. It is made by amateurs who seem immune to feedback. Errors are only to be expected.

Which raises a paradox. The job of running the economy is entrusted to anyone. But the job of running companies requires people of such rare and delicate talent that only multi-million salaries will attract and motivate them.

Why the inconsistency? I suppose you could argue - Robert Lucas style (pdf) - that the benefits of good macroeconomic stabilization policy are small, as are the costs of bad policy, so it doesn't matter much who runs macro policy. But the government isn't doing this. And anyway, the benefits of "good management" are also small. Even if Stephen Hester could raise RBS's value by 50%, the annuity value of this to tax-payers would be only 0.03% of GDP.

An alternative argument is that fiscal policy is not meant to be competent, but is instead meant to reflect the preferences of voters, and democracy is an intrinsic good, not an instrumental one.

There is, though, a third possibility. The purpose of macroeconomic policy is not to stabilize the economy or to raise growth, but is instead merely an ideological cover for shrinking the state. And that justification for multi-million salaries is merely ideological cover for kleptocracy. It's just class war.

January 27, 2012

On Hester's bonus

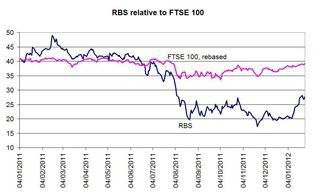

RBS's award of a £963,000 bonus to Stephen Hester has provoked anger. My chart shows one reason why. In the last 12 months, RBS's share price has underperformed the market; it has also underperformed two of its three main peers - HSBC and Barclays but not Lloyds. Insofar as Hester's job is to raise the value of RBS for the tax-payer, he has failed in the last 12 months.

But is the share price the relevant measure of performance?

In one powerful sense, yes. A share price assesses the overall value of the firm. It is (almost) always possible to point to something good that a CEO does; it would be remarkable if a base salary of £1.2m did not buy some competence. The question is: are the things he's doing sufficient to raise the overall value of the company? The share price is a good gauge of this.

For example, RBS justifies the bonus by saying, among other things, that "all core businesses are now profitable other than Ulster Bank" and that "RBS's balance sheet has been reduced by more than £600 billion since 2008" (a good thing, apparently).

But it's possible to return a company to profit and shrink its balance sheet by jeopardizing its future performance - for example, by selling off useful assets or by worsening customer service and so driving business away. The share price is a measure of whether the "improvements" a CEO has made will lead to lasting gains. RBS's price fall suggests this is in doubt.

Now, there are two objections to this.

One is that, because of investor irrationality, a share price isn't necessarily a good measure of corporate value. True. But it's not just investors who a prone to cognitive biases. So are remuneration committees; isn't it more likely that a handful of like-minded people will be systematically biased than that tens of thousands of share traders will be?

The bias I have in mind here is a halo effect. It's easy to think: "He's a nice guy, who seems like he knows what he's doing and he's working hard, therefore he must be doing a good job." But the "therefore" is a leap of logic.

Why should we believe that RBS's price is irrationally cheap, rather than that the remuneration committee is biased?

The second objection is that RBS's price reflects not just Hester's contribution, but rather the impact of the euro area's debt crisis.

Of course. But this fact has two implications.

First, it means Hester could be richly rewarded for a factor entirely out of his control. Let's suppose that the debt crisis is satisfactorily resolved and that RBS's price - along with that of other banks - thus rises. If it returns to January 2011's level of 40p, then Hester will make a profit of £477,000 - without him (ex hypothesi) doing anything. Where's the incentive here?

Secondly, this acknowledges the point I've made for years. To a large extent, the value of firms is beyond the control of CEOs. "Management" functions rather like witchcraft. It's a set of rituals which are wrongly supposed to have effects on the outside world. When, by happy chance, those effects materialize, the witchdoctor takes credit. And when they don't he blames external malevolent forces - if not the debt crisis then the "challenging economic environment", "fragile consumer confidence" or (more feebly) "operational issues (pdf)."

Now, the key phrase in that last paragraph was "to a large extent". Although CEOs might not be able to relaibly affect corporate value on the upside, they can assuredly affect it on the downside through deliberate vandalism and theft. In this sense, bosses are paid a fortune not so much to motivate them to great performance, but to buy off terrible performance. It's just an extreme manifestation of the efficiency wage argument.

And this might partly lie behind Hester's bonus. Robert Peston says the Treasury feared that Hester and the board would have resigned if it had vetoed a bonus. Now, whether this threat was serious or not, and whether the resignations would have been anything worse than a short-term inconvenience, are separate questions. The point is that this shows that bonuses are a reward for power, not performance.

January 26, 2012

Adjustment costs vs steady states

Consider four issues:

1. John McDonnell objects thusly to the EU-India Free Trade Agreement:

If multi-brand retailing is suddenly and without safeguard opened up to EU retailers such as Carrefour, Metro and Tesco, 1.8 million jobs may be created, but at the cost of up to 5.7 million people working as street vendors.

But there are reasons to agree with Peter Mandelson that those 5.7 million are only "short-term losers". Those 1.8 million new jobs will be (relatively) high productivity an high wage ones. As those workers spend their higher incomes, they'll create new demand which will create other, maybe better, opportunities for those displaced street vendors. It's not at all clear that trade liberalization leads to lasting unemployment and poverty (big pdf).

2. One justification for a benefits cap is that the squeeze on housing benefit will force landlords to reduce rents. But in the process, some people might become homeless.

3. Jonathan Portes says it is possible that immigration raises unemployment in the short term, but that in the longer-term, joblessness depends other, macro, factors.

4. A return to national currencies within Europe might be superior to monetary union. But the cost of making the return - a huge banking crisis - is huge.

These look like four different issues. But they have a similar structure. In all cases, we have a problem of adjustment costs. Free trade, limited housing benefit, free migration or floating exchange rates might be superior to the alternatives, but there are costs of making the move.

So far, so straightforward. But here's a quirk. It is, in theory, quite reasonable to say "state B is superior to state A, but the costs of moving are prohibitively high. So let's stick with A." But, I suspect, few people take this position. It's far more common to conflate the adjustment costs with the argument that B is actually inferior to A even as a steady state.

Here's another quirk. Our first three cases above all have something else in common. People who think that markets operate reasonably smoothly will believe the adjustments are small, and so in all three we have a debate between market optimists and pessimists. But the issue of adjustment costs needn't always take this form. Consider a fifth case, thus:

A "John Lewis economy" would be superior to one with external shareholders, as workers will be more productive, there'll be more effective oversight of management, and there'll be less inequality. However, a transition to a John Lewis economy requires that shareholders be expropriated and their stakes transferred to workers.

(I could add a sixth - the idea of cancelling debts).

I suspect that attitudes to this will be the opposite to that in our first three cases. The folk who think adjustment costs tolerable in those will think them intolerable in this. They might be right; if the state can violate property rights once, they can do so again, so such an expropriation might scare off future investors and thus depress economic activity. But this is arguable.

Which brings me to my concern. Could it be that popular debate about adjustment costs consists of a lot of fact-free hand waving?

I'm tempted to add - as Jonathan says - that it is overly influenced by cognitive biases such as the availability heuristic that causes us to focus too much upon lively anecdotes to the detriment of equilibrium thinking. But the complication is that the anecdotes are about real people, whereas equilibrium thinking is not.

I fear the issues here are trickier than are generally realized.

January 25, 2012

Is there an austerity curve?

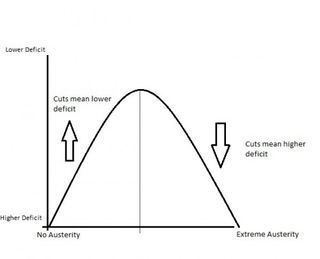

I'm intrigued by Duncan's idea of an austerity curve. - the idea that:

cutting government spending up to a certain point leads to lower deficits but beyond a certain point, the impact of lower growth and higher unemployment means that deficits get worse as the government cuts more.

If you support the Labour party's position of supporting small cuts but not large ones, you have to believe something like this*.

It seems to me that this is only possible if the multiplier varies with the size of cuts. For small cuts, the (negative) multiplier must be sufficiently small that GDP doesn't fall so much that tax revenues fall and benefit spending rises by more than the initial cuts. But for larger cuts, the multiplier gets bigger, and so big austerity backfires.

To fix ideas, let's say that a one percentage point drop in GDP leads to the deficit rising by 0.7 percentage points (pdf) of GDP. It follows that for an austerity curve to have the shape Duncan suggests, the multiplier must be less than 1.4 (1/0.7) for small cuts, but more for large ones.

I can imagine three possible reasons for this:

1. The monetary policy response. Bigger fiscal austerity requires a bigger loosening of monetary policy. But this might not work. The efficacy of quantitative easing is uncertain - partly because it works by reducing tail risk, and this varies over time. A big fiscal tightening thus increases the possibility that the monetary policy response will be inadequate, whereas a smaller fiscal tightening runs a smaller risk.

2. Labour market adjustment. With decent active labour market policies, it's possible that a few thousand redundant public sector workers can be retrained or repositioned for private sector work. But it's less possible to do this for hundreds of thousands of them. Greater austerity might therefore increase the mismatch between the unemployed and vacancies, thus worsening the Beveridge curve.

3. Signalling. Big austerity signals that there is a serious risk of a debt crisis. But business might take fright at this signal, and thus cut investment. More modest fiscal adjustment - a "touch on the tiller" - needn't have such adverse signals. (I'm thinking here of a loose analogue to Caplin and Leahy's famous paper (pdf) on monetary policy signals).

The idea of an austerity curve is, therefore, not obviously wrong - though I challenge anyone to quantify all this.

But nor is it obviously right. One could argue to the contrary, that small fiscal tightening might have bigger multiplier effects. This would happen if people think that more cuts will be needed in future, and so business investment falls as firms anticipate long years of austerity.

My point here is, I fear, merely a somewhat nihilistic and cliched one. It's that the response of economies to macro policies varies over time and place, so that there are few stable coefficients. It is therefore simply not possible to know the precisely correct macro policies. Which makes the debate between big cutters and little cutters a little like arguments about how many angels dance on the head of a pin.

* I don't think the alternative justification for such a position - that the economy can take small cuts but not large ones - is terribly persuasive, as it's not obvious that it can take even small cuts.

January 24, 2012

Should we cap bosses' pay?

As it seems unlikely that Vince Cable's plan to empower shareholders will greatly rein in bosses' pay, George Monbiot is proposing a simpler alternative - a maximum wage law. I'm not sure that either proposal is good enough.

Granted, they might be. There's an element of the arms race about bosses' pay. It's possible, therefore, that anything that can achieve co-ordinated control of pay will reverse this. If company A knows that company B is not paying silly money (either because of a law or shareholder activism), then it won't do so either. The bubble thus bursts.

And this mightn't have adverse effects on incentives. Insofar as CEOs' demand for high pay is a positional good - they want better pay than their rivals - anything that curbs their rivals' pay will curb theirs.

So far, so good. But there's an offsetting danger.

The problem is that CEOs are status-seeking animals; this is why they try to get the top job. If they cannot achieve high status through their salary, they might therefore try to achieve it by other means - for example by building corporate empires, by pursuing non-financial perks such as even more lavish head offices, company jets and suchlike. Or they might simply appropriate corporate assets for themselves; remember, the reason why high pay is necessary now is to bribe them not do so this.

In this sense, capping pay might well have adverse effects. As evidence, remember the 1970s. When high tax rates deterred bosses from getting more money, the result was overly large and inefficient conglomerates, and a management obsessed by status - the legendarily key to the executive toilet - which created a poisonous industrial relations atmosphere.

My point here is that high CEO pay is not the disease, but the symptom - of the fact that CEOs have too much power. Treating the symptom is not sufficient, and might even be counter-productive. What is needed is to rein in bosses' power. And given the difficulties of getting shareholders to do this - asymmetric information, the problem of collective action and so on - it might well be that workers are better able to do so. And I'm talking about far more than merely having employee representation on remuneration committees.

What we're seeing with the debate about bosses' pay is, I fear, a similar thing to what we saw with Clegg's call for more employee share ownership. There's a tendency for liberals and the "moderate" left to think that a halfway house between full capitalism and full socialism is better than both. This is a prejudice which is not always or necessarily true.

Now, you might object that more radical means of curbing bosses' power are just not feasible right now, whereas limits on bosses' pay are.

True. But what's feasible is not always what is efficient.

January 23, 2012

The ideology of incentives

Nick Clegg says we need a cap on benefits "not least to increase the incentives to work." This runs into an obvious objection - that the big problem right now is not so much a lack of incentives to work but a lack of opportunities to do so. There are 2.69 million unemployed chasing 459,000 vacancies - that's 5.85 unemployed per opening.

Prating about incentives when the big issue is the lack of demand for workers requires the sort of stupidity that doesn't emerge unaided. It requires the help of ideology. There are several cognitive biases which lead people to over-rate the importance of incentives to work.

For folk to the right of Clegg - and there are some - one of these is seeing what we want to see bias. If you inhabit the dreamland in which market forces always work well, one way to reduce the cognitive dissonance that arises from the fact that millions are unemployed is to emphasise incentives in an effort to diminish the significance of market failure. It's for a similar reason that libertarians overweight the importance of minimum wage laws as a cause of joblessness. Some people go to great effort to deny the fact that the labour market is probably the most inefficient of all major markets.

There are four other biases:

- The fallacy of composition. I'll concede (more so than most lefties I suspect) that many individual unemployed people would have a good chance of getting work if they tried harder - if they, ahem, brushed up their CV (as Iain Duncan Smith did) or were more flexible. But what is true for one is not true for all. If all jobseekers were to try harder, there'd still be millions out of work.

- The fundamental attribution error. If you come from the sort of background where you can do anything if you try, you will naturally come to exaggerate the importance of individual agency and to downplay the role of environmental factors, such as there being few jobs available.

- The halo effect. Clegg says it's fair that those out of work get less than those in. It is, however, a common error to believe that if something has one good quality, then it has others; which is why the good guys in the films are so often better-looking and better shots than the bad guys. It's tempting, then, to think that what's fair is also what's efficient. But it ain't necessarily so. (The left, of course, is especially prone to this error).

- The action bias. Governments can't do much to greatly increase labour demand, especially if they are committed to fiscal tightening. But they can "improve incentives." And because politicians have a bias towards doing things, they act like lonely men who exaggerate the virtues of their few friends and exaggerate the importance of incentives.

Now, I don't say this to dismiss all talk of incentives. Instead, such talk is an example of what I've called the "small truths, big errors" syndrome. And sometimes, this syndrome is motivated by bias and ideology.

January 22, 2012

Preferences in politics

A new paper by Daniel Hausman raises an important question which conventional politics ignores: why should we satisfy people's preferences?

Hausman's answer is that preferences have no intrinsic value. Instead, they matter only to the extent that, under some circumstances, they reveal people's welfare:

When people's preferences are undistorted and largely self-interested and their beliefs are true, preference satisfaction indicates welfare. It is because preferences often indicate welfare that policy-makers should aim to satisfy preferences.

This, of course, poses the question: how we can tell when preferences are undistorted and beliefs are true?

One might think that this is more likely to be the case when an issue is clear-cut, bears directly upon an individual and when he gets quick and clear feedback about his preferences.

There's one realm where this is especially unlikely - political choices. Rational ignorance and inattention, along with countless cognitive biases and ideologies, give us plenty of reason to suppose that voting preferences don't satisfy Hausman's principle. And yet politicians very rarely (in public) suggest that voters are systematically irrational. By contrast, they are keen to question the validity of preferences in areas where one might imagine that individuals are better judges of their well-being; I'm thinking here of laws against drugs and assisted suicide, and the entire nudge agenda.

However, even if voting behaviour doesn't reveal welfare, there is a justification for democracy. Welfare isn't everything. And the idea that people's preferences should be over-ridden leads swiftly to tyranny.

Strong as this argument is, it tells us that democracy is an intrinsic good (or more accurately bad avoider) rather than an instrumental one. It gives us no reason to suppose that people's actual choices within a democracy will be welfare-enhancing. And yet the political class pretends that this is not just possible, but common. Which, I suspect, betrays a confusion about the role of preferences in politics.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers