Chris Dillow's Blog, page 190

December 7, 2011

Ideology, equality & democracy

If a man says he believes in God, he tells you more about himself than he does about the existence or not of the deity. We should interpret the latest British Social Attitudes survey in the same way - as telling us more about those surveyed than about external reality.

The survey suggests, says George Eaton, that "the public are increasingly individualistic and less concerned with inequality and climate change than they were a decade ago."

It shows that only 34% of the public believe the government should reduce inequality through more redistribution, 63% think child poverty is partly because parents don't want to work, whilst 55% think benefits for the unemployed are too high.

But why are the public so mean-spirited? It could be that unemployment benefits really are too high. After all, we can all live like kings on £67.50 a week, can't we?

The very question, though, hints at another possibility - that these attitudes tell us not about the facts of poverty and the benefit system, but rather about the way in which ideology is constructed. I suspect there are (at least) three mechanisms at work here:

1. Recessions make us meaner. Rob Marchant points out that "since 1918 there have been six recessions, but arguably only one economic paradigm shift to the left." There are good reasons for this.

2. The just world effect. One way people respond to injustice is by denying that it exists. Instead, people construct narratives to convince themselves that things are fair. The medieval peasant who thought his feudal lord treated him badly because it was God's will, the claim that rape victims were asking for it, and the belief that people are poor because they don't want to work are all examples of the same cognitive bias.

3. Adaptive preferences. Another response to injustice or ill-fortune is to resign oneself to it, to reduce cognitive dissonance by adpating one's preferences to what one believes (rightly or wrongly) to be feasible. As Chesterton said, "No man demands what he desires; each man demands what he fancies he can get." We see this in the survey in three ways:

- a large proportion of people (38%) say it is inevitable that people will live in need.

- the lack of demand for redistribution might be in part a reflection of the fact that seriously redistributive policies are not on offer. Folk don't want what isn't available.

- Some of the longer-term unemployed might respond to their plight by diminishing their desire to work. They will then seem lazy. But their laziness is the effect of their joblessness, not the cause. If folk confuse cause and effect, they'll blame unemployment upon laziness, rather than vice versa.

My point here is there are socio-psychological forces which generate an anti-leftist ideology, whether the facts sustain such beliefs or not.

And this has a grim implication for the left. Given public opinion, it is very difficult to be both an egalitarian and a democrat.

December 6, 2011

On uncertainty

Richard and Tim's latest spat concerns the role of uncertainty, as distinct from risk. Richard says:

Keynes pointed [that] the number of circumstances where we can make the predictions neoliberal economists think possible are remarkably limited. He said the future is not probabilistic as they suggest in most cases: it is actually uncertain.

To this, Tim replies - correctly - that Hayek was fully aware of the importance of uncertainty.

But Richard has a point, which is hidden by his silly conflation of neo-liberal and neo-classical economics: Hayek was a neoliberal economist but not a mainstream neoclassical one.

If we define neo-classical economics as stuff we learn at university (I'm using the Royal We) then it does, I suspect, emphasize probability over Knightian uncertainty. When I did my masters (25 years ago!) we learnt about expected utility theory, regret and even prospect theory. But uncertainty barely featured. Yes, the Ellsberg paradox got a mention. But like Allais' paradox, it was something we looked squarely in the face and moved on from.

Cynics might say this is because orthodox economists were wedded to a scientistic faith that economics should be mathematical. Expected utility and its variants lend themselves to a maths that is suitable for university exams, but uncertainty doesn't. Yes, Larry Epstein, among others, has done important mathematical work on ambiguity, but this is hardly good exam material.

Herein, though, lies a nasty fact. Academic economics' elevation of probability over uncertainty reinforced our human tendency to prefer risk to uncertainty. And - wishful thinking being so powerful - this preference gave rise to a belief that future outcomes really could be quantified and managed. But the banking crisis showed that this belief was an expensive mistake. Yes, Hayek could have told us this. But banks weren't listening to Hayek.

Another thing: Although Hayek saw uncertainty as a reason to reject central planning, the man who first emphasized the distinction between risk and uncertainty - Frank Knight - saw uncertainty as a reason for the existence of hierarchical, centrally-planned organizations, namely firms:

When uncertainty is present and the task of deciding what to do and how to do it takes the ascendancy over that of execution, the internal organization of the productive groups is no longer a matter of indifference or a mechanical detail. Centralization of this deciding and controlling function is imperative.

And another thing. I really can't be arsed to define neoclassical and neoliberal properly. My blog, my (rough) definitions.

December 5, 2011

Who cares what rioters say?

The Guardian's "reading the riots" project raises a general question in the social sciences: to what extent can individuals' coherently explain their own actions?

The Guardian says:

Widespread anger and frustration at the way police engage with communities was a significant cause of the summer riots…The project collected more than 1.3m words of first-person accounts from rioters, giving an unprecedented insight into what drove people to participate in England's most serious bout of civil unrest in a generation. (Emphasis added)

But why should we believe rioters' own accounts of their actions?

One reason to think not is that people are so keen to maintain a positive self-image of themselves that they engage in self-serving biases, as Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson showed in their book, Mistakes Were Made. Three aspects of this are:

1. People paint themselves as victims. Tavris and Aronson say:

Self-justification works to minimize any bad feelings we might have as doers of harm, and to maximize any righteous feelings we might have as victims.

Which poses the question: are rioters' complaints about police harassment a genuine cause of the riots, or are they simply part of this self-justification?

Note that this point is not merely about rioters. Dick Fuld tried to downplay his role in the collapse of Lehmans by claiming to be the victim of market forces and Fed meanness. The victim narrative is a standard part of self-justification.

2. People don't accept personal responsibility, and distance themselves from their actions. Rather than say "I was wrong" they say "mistakes were made" - hence Tavris and Aronson's title; Liam Fox recently used just these words. This bias means that self-explanations of the riots will naturally under-rate the importance of simple criminal impluses.

3. People don't accept often accounts which tell them they are weak. This means that peer pressure - "I did it because others did" - will be under-emphasized by self-serving accounts. And yet peer effects must be part of the explanation for the riots.

Now, you might think that, in saying this, I'm siding with those rightists who have criticized the report.

Maybe not. There is, of course, one figure above all others who warned us not to take individuals' conscious explanations of their behaviour at face value - Marx:

It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

And, he added, the fact that we are systematically unaware of this generates ideology and false consciousness. But this in turn means that individual's subjectivity is constructed by forces they don't understand. Subjective accounts of one's behaviour will, then, be partial and misleading.

I say all this not to dismiss the Guardian's work out of hand, but rather merely to pose a question about the nature of explanation. That said, two thoughts arise. One is: could it be that what we are seeing here is a form of journalistic ideology? Journalists naturally think that you can find the "truth" if you ask enough people. But this isn't self-evidently the case.

More unpleasantly, could it be that the belief that talking to rioters can explain the riots reflects a form of middle-class self-hatred - that the truth is to be found on the "street"?

December 4, 2011

In the black Labour: some issues

If I were one of the authors of In the black Labour, I'd be taking great comfort from recent US economic data.

These show that the economy is holding up well, despite the prospect of a significant tightening of fiscal policy next year. This hints at an intriguing possibility - that, maybe, expected future fiscal tightening need not be contractionary now. Maybe people are more myopic than conventional rat-max economics assumes.

This weakens one obvious objection to ITBL's proposals. Hopi says that "fiscal conservatism for the long term doesn't mean fiscal stupidity in a crisis" - in other words, that Labour should run loose policy in recessions, with the promise of tightening later.

If current US experience is right, such a policy is feasible, as the expected future tightening need not depress current activity and so offset the current loosening.

Instead, I have three other quibbles.

One concerns the mechanism for enforcing future tightenings. Hopi suggests "an obligation, policed by the OBR, to run a current spending surplus in any year when growth is projected to be over 2%."

This runs into a problem - that growth projects are often wrong. If - as is usually(pdf) the case - a recession is unexpected, such a rule could well mean the government tightens fiscal policy at the start of a recession.

I would prefer to see either stronger automatic stabilizers - higher marginal tax and benefit withdrawal rates - or state-contingent policy tightening, based upon realish-time indicators (eg VAT rises if retail sales growth exceeds x%).

My second concern is about the financial balances. Governments can only run surpluses if the private sector invests more than it saves; this is an accounting identity. But what if the dearth of investment opportunities and households' desire to pay down debt causes the private sector to run sustained financial surpluses, even if growth were around its modest trend rate? In such circumstances, government efforts to run a surplus would be counter-productive.

My biggest concern, though, is the public choice aspect. Two things will put upward pressure upon the public finances: Baumol's cost disease, which causes the relative cost of public services to rise over time; and the fact that Labour's client base - public sector unions - will demand increased spending. It's a little optimistic to hope, as ITBL do, that these can be fully offset by "prioritisation, institutional innovation and reform."

Fiscal conservatism will thus require a large, and expanding, tax burden; as ITBL say: "if we want to collectively fund something, we've got to collectively pay for it." But I detect little public appetite for collectively paying more.

How can we reconcile the two? It would be forlorn to hope that taxing the rich would be sufficient here - not because of Laffer curve considerations but simply because there are so few of the rich. One possibility is to close the "tax gap." But if this proves insufficient, the tax base might have to be broadened somehow.

Which brings us to the problem that whilst fiscal conservatism is an attractive principle - the 1945-51 government showed that ITBL are right to say that "there is nothing right wing about fiscal conservatism" - its implementation will be much tougher.

This, though, is not so much a problem for ITBL alone as for any fiscal policy.

December 2, 2011

"Osbrowne": the psychology

In the Times, Phillip Collins says of George Osborne that "it was hubris worthy of Mr Brown to trust that export growth would be as fast as it needed to be make the Treasury's growth forecasts come true." This is not the only parallel between the two; Osborne's ragbag of tricksy policies aimed at raising long-term growth also look rather Brownian.

Such similarities shouldn't surprise us. Politicians of all main parties have a lot in common simply by virtue of being politicians. In particular, they are selected to have particular cognitive biases.

What sort of person will want to be a politician? There are three related types:

- Someone who thinks that policy can change society. But - at least in the context of longer-term economic growth - this belief owes more to wishful thinking than the evidence.

- Someone who is overconfident about their chances of success - in terms of either achieving office or doing something useful when they have it. Such overconfidence reinforces the optimism bias, and leads Chancellors - be they Osborne or Brown - to believe they can transform the economy.

- Someone who thinks that individuals can make a difference; the sort of person who thinks politicians are victims of events and circumstance is unlikely to enter politics. This means politicians are prone to the fundamental attribution error, of overweighting the role of agency and underweighting that of environment. Again, this leads them to believe that their own actions can make a difference.

There's worse. Someone entering politics might have these biases. But they are highly likely to be reinforced throughout their career. The fact that you're surrounded by like-minded people who share these biases will generate a form of groupthink. And the fact that the opposing party also shares them will breed a folie a deux, in which one side's delusions are reinforced by the other. (In fact, it's a folie a trois, because the media - with its search for heroes and villains - further reinforces these biases.)

In this sense, the cliché that politicians are all the same has some validity. There are all the same in some respects because selection effects cause them to share particular cognitive biases.

Now, it would be wrong to say that politicians are unique in having these biases. Most of us are guilty of overconfidence or wishful thinking at least sometimes. It's just that politicians are selected to be more so than others.

Not that they are alone in being so selected. So are company bosses. It's small wonder, therefore, that the political and business "elites" should be so close to each other. They have a lot in common. The trouble is, they just don't have so much in common with the rest of us.

December 1, 2011

Why stagnation matters

The IFS's Paul Johnson says (pdf):

Real median household incomes will be no higher in 2015–16 they were in 2002–03, more than a decade without any increase in living standards for those in the middle of the income distribution. We estimate that in the period 2009-10 to 2012-13 real median household incomes will drop by a whopping 7.4%.

History suggests this could have nasty consequences. Benjamin Friedman has shown that (pdf):

Economic growth—meaning a rising standard of living for the clear majority of citizens—more often than not fosters greater opportunity, tolerance of diversity, social mobility, commitment to fairness, and dedication to democracy…But when living standards stagnate or decline, most societies make little if any progress toward any of these goals, and in all too many instances they plainly retrogress.

A new paper provides micro-level evidence to corroborate this. It looked at the impact of lottery wins on personality and found that money makes us nicer people:

Unearned income improves traits that predict pro-social and cooperative behaviors, preferences for social contact, empathy, and gregariousness, and reduces individuals' tendency toward negative emotional states.

The danger, then, seems clear. Economic regress might mean social regress - more conflict, anti-socialness and intolerance.

But herein lies a puzzle. There seems little evidence - so far - that this is happening (Clarkson and tram woman are of more interest to the psychiatric than the social sciences). Crime hasn't risen much, the far right is a nugatory force, and people seem to be quite happy; I'm not sure whether August's riots count as evidence here or not.

Which raises questions. Are there some mechanisms which offset the above tendencies and so cause economic stagnation to not have such adverse effects - some combination of peer effects and path dependency perhaps? Or am I misreading the evidence? Or will things change as I fear? I honestly don't know. But I do know that this, rather than a few tweaks to fiscal policy, is the key issue.

November 30, 2011

Structural deficit doubts

The OBR's new forecasts remind me why I hate the concept of a structural budget deficit.

It has reduced its estimate for trend growth in recent years and thus reduced its estimate of the output gap. Because of this, it thinks more borrowing is "structural" and less "cyclical" than it previously thought.:

By 2015-16, we expect PSNB to have fallen to £53 billion or 2.9 per cent of GDP, compared to the £29 billion or 1.5 per cent of GDP that we forecast in March. The extra borrowing is primarily structural rather than cyclical, in other words it will not disappear as the economy recovers.

This in turn has put pressure on Osborne to tighten policy in order to meet his self-imposed target of balancing the structural current budget in five years' time.

I have four problems with this:

1. It makes policy pro-cyclical. If estimates of trend growth fall when growth is weak, then the desire to balance the structural budget imposes fiscal tightening in bad times*.

And it's not just fiscal policy that becomes pro-cyclical. So does monetary policy. A lower output gap estimate means - other things equal - a higher forecast for inflation and hence, under inflation targeting, less justification for loose monetary policy.

Luckily, it's not clear that the Bank shares the OBR's pessimistic view of spare capacity; it seems more optimistic about inflation than the OBR. But this is a happy accident. A policy framework that depends upon the monetary and fiscal authorities having different views is not sustainable.

2. The distinction between "cyclical" and "structural" borrowing does nothing to answer the key question, which is: will the gilt market remain content to finance borrowing? It might be that the gilt market is happy to finance even "structural" borrowing, insofar as this is the counterpart of weak long-run growth and hence poor returns on equities. Or maybe not. Merely labelling borrowing "structural" doesn't help.

3. The concept of a structural deficit leaves unanswered the question: how, exactly, does a fiscal tightening reduce the deficit?

What I mean is that a structural deficit implies that, if the economy were at its trend level of output, the private sector would be saving more than it invests: this is the counterpart of the government's deficit. To reduce the structural deficit thus requires that private sector investment rises and/or savings fall. But how does fiscal tightening achieve this?

4. Forecasts of the structural deficit rest upon two huge uncertainties - and it's not clear that they offset each other: an uncertain estimate of the output gap (and sensitivities of spending and revenues thereto); and the usual uncertainties surrounding any fiscal forecast. I'm with Simon Ward on this: "it is troubling that the fiscal framework pivots on a concept subject to huge empirical uncertainty."

I suspect that the notion of a structural deficit is playing an ideological role - one that's a little analogous to the reasons why the Greeks and Italians have "technocratic" governments. A pseudo-scientific claim to expertise is being used to disguise what is, in fact, a judgment, that borrowing is too high and can and should be reduced by fiscal policy.

* It's not good enough to claim that Osborne's new tightening is back-end loaded, with spending cuts in 2015-17. The anticipation of future tightening might depress activity now.

November 29, 2011

What are gilts saying?

In his Autumn Statement George Osborne said that the UK government is now "borrowing more cheaply than Germany" and (par 1.39) "there is evidence that the Government's fiscal plans are contributing to improved market confidence, with UK long-term interest rates reaching a record low*.

This, though, runs into a problem. Low gilts yields - either in absolute terms or relative to overseas - are, in themselves, an ambiguous sign. Yes, they might signal confidence in the government's creditworthiness. But they might also signal that the economy is weak. How can we adjudicate between these interpretations?

One way is to look at share prices. If gilt yields fall because of better creditworthiness, share prices should rise as investors attach a lower probability to the risk of a debt crisis which causes capital flight and enforced austerity. But if gilt yields drop because of a weak economy, shares should suffer.

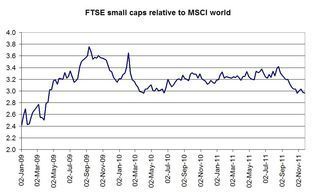

My chart tries to adjudicate between these two possibilities. It shows the FTSE small cap index (chosen because small caps are more exposed to the UK economy than the FTSE 100 which is dominated by multinationals) relative to MSCI's world index in sterling, which controls for global influences upon equity prices.

This chart is wonderfully ambiguous.

Tories can point to the rise in small caps relative to the world between May 2010 and this summer as a sign that the fall in gilt yields (from 3.8 to 2.5 per cent for 10 year ones) was accompanied by increased confidence in the UK economy - or, at least, reduced fear of a debt crisis.

However, Labourites can point to the drop in small caps since then as a sign that lower gilt yields are a sign of depressed economic confidence.

I'd stress that, in both cases, the moves are small; if I'd started my chart earlier, the last 18 months would look like a horizontal line.

The only message I'd take from this is that political disputes are rarely settled by the facts.

* I'm not sure this is strictly true. Yields on 2.5% Consols, for which we have the longest history, are 3.68%, which is higher than they were between 1934 and 1950 or in the 40 years before World War I.

November 28, 2011

Inequality, happiness & age

Is inequality worse for older societies? I ask because of this new paper. It shows that the effect of other people's incomes upon happiness varies with age.

The over 45's are unhappier the higher is other folks' income relative to their own. But the opposite is true for the under 45s; they are happier, the higher are others' incomes.

There's an obvious reason for this. When we are young, other people's high incomes tell us that we have a chance of a high income ourselves if we work hard. But when we are old, it tells us that we have failed or been unlucky.

This suggests that, as society ages then - ceteris paribus - a given level of inequality will be worse for happiness, as there'll be more people suffering the relative deprivation effect and fewer benefiting from the increased optimism effect.

You might think this runs into a paradox. It suggests that the old should be more left-wing than the young, whereas the opposite is the case. This, though, is easily resolved. (Some) older people internalize inequality; they read it as a reason to blame themselves rather than "society." (Some) young, on the other hand, have cognitive dissonance, both rebelling against inequality whilst expecting it to benefit them (this was true for me in my 20s).

This leaves us with a conflict. Utilitarians should become more egalitarian as a society ages, because inequality does more to depress happiness. But this in turn means they should become less keen on democracy - because, given the tendency of older folk to be more conservative, ageing societies are less likely to vote for egalitarian policies. To borrow Norm's phrase, the conflict between interests and political will becomes starker.

How can this conflict be mitigated? There's a leftist and rightist answer.

The leftist answer is that it is not always the case that young people are happier when others' incomes are higher. Although this is true for Germany, it does not seem true in the UK, where the impact of relative income on happiness is insignificant. There might be a simple reason for this difference. Social mobility is higher in Germany than in the UK, so inequality in Germany signals better prospects for the worse-off young than it does in the UK.

Unfortunately for the left, there's also no significant link between relative incomes and the happiness of older folk in the UK - which suggests that utilitarians needn't trouble themselves about inequality at all.*

The rightist answer would be to ditch utilitarianism, and claim that some things - the popular will, freedom, whatever - matter more than happiness. This, though comes at a cost. One cannot easily make consequentialist arguments for economic freedom - as it mightn't make an older society happier. And one has to ditch the rationalist assumption that people's expressed preferences are consistent with what makes them happy.

These issues, then, are awkward across the political spectrum.

* Curiously, though, there is a significant adverse correlation between relative income and happiness for people of all ages. This might be an example of Simpson's paradox.

November 26, 2011

The stupid right

It's become a cliché that the Occupy movement has few good ideas for improving the economy. But it is not alone. The same can be said for the Tory right, for example:

- the call to relax employment protection, despite the absence of any empirical or theoretical evidence that doing so would increase employment.

- a demand to scrap the youth minimum wage, even though this would, at best, make only a small dent in unemployment.

- a demand (pdf) to scrap the 50p tax rate on the grounds that it might eventually deter work and entrepreneurship, even though there's no evidence yet for such effects*.

What interests me here is: why should the standard of rightist argument be so low - almost wilfully ignorant of opposing evidence? Here are five theories:

1. Diminishing returns have set in. Back in the 70s, one could argue with at least some plausibility that strong workers' rights and high taxes were squeezing profits and deterring effort. By now, though, the effective policies in the neoliberal barrel have been taken, leaving its advocates to scrape the bottom.

2. Inequality breeds arrogance. The rich and their lackeys feel so smug and that they believe they don't even have to try to cloak their self-interest in the disguise of economic efficiency.

3. An anti-scientific culture. Why bother with awkward, messy, statistical evidence when your own prejudice and ego tell you all you need? This philistinistic attitude is perpetuated by the BBC, with its absurd tendency to present the bar-room talk of business people as serious proposals to raise economic growth.

4. The politicians' syllogism: "Something must be done. This is something. Therefore this must be done." Policies such as the ones above don't arise from a thorough investigation of the evidence, but rather from a desire to get growth going again, combined with (1) and (3).

5. There's a race to the bottom. If you believe that the best your opponents can do is advocate a Robin Hood tax or claim that tax evasion caused the world economic crisis, then you'll have no incentive to think hard and well - any more than Man United would need to put out their strongest team if they were drawn against Anstey Nomads third XI in the Cup. A lack of competition produces low standards.

I've said before that ability is endogenous, and so the successful don't deserve credit. But maybe a lack of ability is endogenous as well, so we shouldn't blame the right for their apparent stupidity.

* I'll concede that such evidence might eventually emerge - but this point warrants a tweet, not widespread press coverage of a report as embarrassing as the CEBR's.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers