Chris Dillow's Blog, page 184

February 26, 2012

Upstairs, Downstairs & the ideology of inequality

Robert Gore-Langton in the Spectator (£) writes:

Simon Williams, star of the original Upstairs, Downstairs, once observed that the caterers and film crew treated the show's upstairs cast much more deferentially than they did the downstairs skivvies.

This is an example of priming; people's behaviour is unconsciously affected by cues. For example, an experiment at New York University found (pdf) that students primed with words associated with old age subsequently walked more slowly than others.

Such priming can often lead to deference, as the Upstairs, Downstairs case shows. In Influence, Robert Cialdini gives other examples of this. People who were asked to give loose change to a stranger were much more likely to do so if the requester were dressed as a security guard than if he were dressed ordinarily; pedestrians were more likely to follow a jaywalker wearing a smart business suit than one wearing casual clothes; motorists were quicker to honk their horns at drivers of cheap cars than expensive ones. In another experiment, people were shown a video of a child playing and judged here to be more intelligent if she were in an affluent neighbourhood than a poor one, even though her behaviour was the same in both.

The mere symbols of authority or wealth, says Cialdini, trigger an automatic "click, whirr" of deference. This can, of course, be positively dangerous - as Stanley Milgram's notorious experiment showed. Cialdini corroborates this, pointing to an experiment in which nurses were prepared to give dangerous overdoses of drugs to patients if asked to do so over the phone by someone claiming to be a doctor.

Priming, though, is by no means the only way in which people come to accept arbitrary inequality. There are other mechanisms.

One is stereotype threat. People tend to live up or down to stereotypes. The Oak school experiments show that pupils arbitrarily deemed to have high IQ subsequently did better at school. And other experiments show that American blacks (pdf) or low-caste Indians can easily be primed to do badly on intellectual tests, thus living down to their stereotype, even though their performance on the same tests in slightly different contexts is good. It might then look as if some people "deserve" to do well and others badly because of differences in ability, even if these differences are endogenous.

Another mechanism is adaptive preferences. If you're unemployed and think there's no work available, you might cease to want to work. But if you're in a job and get a promotion even at random, you might come think that hard work pays off, and so you'll work harder. Some people will thus seem lazy and undeserving and others hard-working and deserving. But their preferences might be the result of their position, not the cause.

A further mechanism is simple path dependence. If we were to randomly assign some people to managerial tasks requiring intellectual effort and others to routine manual work, the intellectual abilities of the former would improve through use and practice whilst those of the latter would atrophy. Bosses would then appear to justify their position by their superior intellect, even though this is effect, not cause. "Leadership skills" - in the rare cases where they genuinely exist - might be the result of people occupying leadership positions, not the cause.

There are, then, powerful psychological mechanisms which can cause unjust or random inequalities to become accepted, even if - as in Milgram's example - they are positively dangerous. And I haven't even mentioned the just world illusion, status quo bias or plain vested interest. The fact that people tolerate inequality is, therefore, no evidence of its justice or efficacy.

February 24, 2012

Tories against balanced budget multipliers

Simon Wren-Lewis says the idea of a balanced budget multiplier - the notion that a rise in public spending paid for by higher taxes will increase aggregate demand - is "a pretty robust bit of macroeconomic theory."

Not so robust, it would seem, as to convince Tories. This week Liam Fox and Tim Montgomerie have called for the exact opposite - cuts in taxes financed by cuts in government spending. From a balanced budget multiplier perspective, this combination would depress demand. This is simply because £100 of extra public spending is £100 of higher aggregate demand, whilst £100 of tax cuts are a smaller boost to aggregate demand to the extent that some of the cuts are saved. Net, then, aggregate demand falls.

So, how can Simon be wrong and Tim & Liam right? I can think of two possibilities, both of which in effect leverage up the tax cuts to give a marginal propensity to spend out of them of more than one:

- Households will see tax cuts now as a promise of more cuts to come. They might therefore borrow against higher expected future incomes.

- If tax cuts incentivize businesses to expand, they might borrow to invest, and so aggregate demand would rise by more than the amount of the tax cut.

Both these mechanisms would be doubtful at the best of times. And these are not the best of times. With banks reluctant to lend, it's surely less likely now than ever before that tax cuts could be leveraged up in these ways. There's not much point giving people incentives to expand their businesses if attempts to do so are met with a "no" from the bank.

From an economists point of view, then, today is the wrong time to be fighting against the balanced budget multiplier.

But are Tim and Liam thinking as economists? I suspect not. They're thinking as politicians. They seem to want to shrink the state for reasons other than likely short-run macroeconomic effects. And I guess they're betting that - given popular (or at least media) hostility to the public sector - tax and spending cuts would be popular.

Maybe they're right on both counts. But please remember that macroeconomic orthodoxy and political expediency are different things.

February 23, 2012

Greece, growth and hysteresis

Can countries get rich by free market reforms alone? One effect of the Greek crisis is that we might find out. The Eurogroup seems to think they can. It called (pdf) this week on Greece to implement a "bold structural reform agenda, in both the labour market and product and service markets, in order to promote competitiveness, employment and sustainable growth."

This, though, runs into Ha-Joon Chang's objection:

Free-trade, free-market policies are policies that have rarely, if ever, worked. Most of the rich countries did not use such policies themselves, whilst these policies have slowed down growth and increased inequality in the developing countries. (23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism, p73)

He cites the fact that the US in the 19th century had massive trade barriers. We can add to this that two of the great growth success stories of recent years - South Korea and China - were built upon massive state intervention. And post-1945 growth in Japan and Germany was aided by hand-outs (pdf) from the US and prolonged by under-valued exchange rates - two advantages Greece lacks.

You might object to this that Britain had free market policies in the 19th century. True enough. But it did not grow quickly then. Between 1846 (the repeal of the corm laws) and 1914, real per capita GDP grew just 1.1% a year. Britain is rich because we grew slowly for a long time, not because we got rich quick.

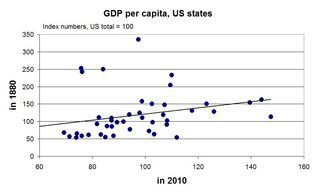

There's one other factor here that I'd mention which is under-appreciated - path dependency. Barring very radical change, relatively poor areas tend to stay relatively poor. My chart shows the point. It plots US states GDP per capita, as a percentage of the US total, for 1880 (p100 of this pdf) and 2010. The key thing here are the points in the lower part of the chart - which represent states which were relatively poor in 1880. You can see that, generally speaking, states that were relatively poor in 1880 - generally southern ones - were still relatively poor 130 years later. Of the 17 states with GDP per capita of 80% or less of the US average in 1880, only three had above-average GDP in 2010. And this, remember, is true for a much more effective fiscal union that the euro area has.

In other words, history matters. The habits and institutions that cause a region to be poor can cause it to stay poor, and the things that cause it to be rich keep it rich. One reason why Germany prospered after 1945 was that it had a great industrial tradition which it only had to rediscover. And Malcolm Gladwell would add that Japan and South Korea's history of rice cultivation inculcated habits of diligence that facilitated economic growth.

And herein lies the question. Mightn't Greece today might be more like West Virginia in 1880 than Germany in 1945 in that it lacks the culture, institutions or human capital which facilitate relative growth? If so, aren't managerialist top-down efforts to implant such features likely to fail?

Hysteresis, remember, is a Greek word.

February 22, 2012

A temporary hiccup?

There's one assumption which seems to be shared by most of Europe's ruling or would-be ruling elite which I find questionable - namely, that our present economic weakness is merely temporary. This view unites (at least) four apparently different positions:

- The ECB's long-term refinancing operations pump cash into banks but don't (directly) improve their capital bases. This makes sense if you expect economic recovery to strengthen their balance sheets and to validate the higher asset prices caused by easy money. If, however, you expect long-term weak growth, they are not sufficient.

- Ed Balls' call for a temporary tax cut makes sense if you think the economy will significantly pick up next year. If you don't believe this, you should be calling for more radical action.

- The coalition expects the private sector to create enough jobs to offset public sector job loss. That this has not yet happened is, presumably, a temporary hiccup.

- The CBI says that "corporate balance sheets hold the potential for much stronger private sector investment", and believes this potential can be fulfilled by a few tax breaks.

There is, though, an alternative possibility - that we face many years of weak growth and mass unemployment. The CBI is right to say point out that firms have lots of cash on their balance sheets. But this might be not a reason to hope for an investment boom, but rather a sign of a long-term dearth of investment opportunities. Companies in the UK have been running a financial surplus since 2002 - long before the crisis. This hints at a long-term structural problem. And it could well be that this will be exacerbated by an overhang of personal debt that restrains consumer spending and by the fact that the demand for unskilled labour in the west has long since collapsed, with the result that millions of people are unemployable from capitalists' perspective.

If I'm right - and of course the difference between "temporary" and long-term troubles is one of degree rather than either/or - then the ruling class's policy proposals just aren't sufficient. Could it be that their faith in capitalism (which in fairness has been correct for a long time) is blinding them to this possibility?

February 21, 2012

Eugenics, prayers & certainty

Reading Jonathan Freedland's piece on the soft left's dalliance with eugenics reminded me of the argument about whether town councils should say prayers at their meetings. What links these two different issues is that both sides appeal to an illusory certainty.

Take eugenics first. On the one side, eugenicists were certain that the state had the power to affect the composition of the race. Reading Sidney Webb's The Decline of the Birth Rate (pdf) one is struck not only by the vile racism - he frets about the country "falling to the Irish and the Jews" - but also by the utter absence of any doubt about the state's competence.

On the other side, though, stands a claim that people have a right to have children. And rights - being entitlements - are things we possess with certainty. Freedland writes:

What was missing was any value placed on individual freedom, even the most basic freedom of a human being to have a child. The middle class and privileged felt quite ready to remove that right from those they deemed unworthy of it.

We have here a clash of certainties - the certainty of state competence versus the certainty that a right exists.

Which is what we have in the Bideford town council case. The protagonists claim that this is a clash of rights, of certainties. Clive Bone claimed that prayers violated his right to be free of religion, whilst Eric Pickles said: "Public authorities - be it Parliament or a parish council - should have the right to say prayers before meetings if they wish."

However, in both cases the argument should not be about certainties, but rather about mundane competence.

The argument against eugenics is not that people have a right to have children. It's not clear that they do. John Stuart Mill thought they didn't. He wrote:

To bring a child into existence without a fair prospect of being able, not only to provide food for its body, but instruction and training for its mind, is a moral crime.

And at least one recent book on human rights is almost silent on whether this "right exists.

Instead, the argument is simply that the state is just not competent to adjudicate who should have children; if eugenicists ruled the world, there'd be no jazz or blues music and not just because of the colour of the musicians' skins.

Similarly, in the Bideford case, the argument against saying prayers at council meetings is not one of rights, but, again, one of competence. Quite simply, council meetings should be devoted to council business, not to prayer. In fairness, this was how the judge ruled - not that either side seems to care about that.

The fact that these two cases are separated by 80 years is depressing. It shows that experience doesn't teach us that our knowledge of public life and moral affairs is fragile and partial. Instead, we see the same appeal to a non-existent certainty in different guises.

February 20, 2012

A case for workfare

Is workfare really such a bad idea? I share the outrage over the state, in effect, giving free labour to large corporations. But mightn't there be a case for a scheme whereby the long-term unemployed, in exchange for benefits, do useful public work such as improving open spaces, building houses or whatever the local area needs? I'm thinking of five advantages of such a scheme:

1. It would improve the well-being of the jobless. It's well-known that the unemployed are less happy than the employed. This is not just because they lack income, but because of the feelings of isolation and not being wanted - being redundant. As Andrew Oswald said (pdf):

The worst thing about losing one's job is not the drop in take-home income. It is the non-pecuniary distress…an enormous amount of extra income would be required to compensate people for having no work

Workfare would address this problem by giving the unemployed useful work and the camaraderie of working with others. Evidence from Germany shows that subsidized employment can increase well-being. So why wouldn't decent workfare?

2. In getting the unemployed out into society, it would increase their circle of friends and acquaintances. This might help them get back into private sector work, not only by encouraging work habits and skills, but also by widening the social networks (pdf) through which people learn of job opportunities. In this regard, workfare might be a better alternative to the numerous courses offered to jobseekers in how to find work.

3. It would increase welfare benefits. Because the "unemployed" would be seen to be doing useful work, it would no longer be possible for them to be stigmatized as scroungers. This wouldn't just increase the well-being of the jobless by reducing the stigma, but would also remove the (mistaken) opposition to decent benefits.

4. It would reduce the fear of unemployment. Joblessness isn't just bad for those who suffer it. It also reduces (pdf) the well-being (pdf) of those in insecure jobs who fear becoming unemployed. Insofar as workfare diminishes the sting of unemployment, it reduces the fear of joblessness.

5. It would allow for more powerful counter-cyclical fiscal policy. One problem with using discretionary changes in public spending to counter recession is that there might not be many "shovel-ready" projects available to spend upon. This lack increases the "inside lag" of fiscal policy, with the result that discretionary fiscal policy takes the form of tax cuts instead, but these have higher leakages than public spending - some of the cuts are saved, or go on exports. A public works agency, whose budget could vary counter-cyclically, would mitigate this problem.

Now, you might object to all this that what I should be advocating isn't workfare at all, but rather that old leftist call, a massive programme of public works. But maybe the sort of workfare I have in mind could gradually become such a scheme. (Note that I'm not saying that the unemployed be coerced into such a scheme either).

What I'm advocating is, of course, an old idea - a form of Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration. And one problem with that - if Big Bill Broonzy is to be believed - was it worked too well.

February 19, 2012

Fiscal policy & the Overton window

Ed Balls is calling for a temporary tax cut of £12bn for one year, ideally through a lower VAT rate but failing that lower income tax. This, I fear, is an example of how policy proposals are constrained by the Overton window.

I say this because such a cut would be only mildly stimulatory.

The IFS has estimated that a temporary VAT of £12bn would increase consumer spending by just over 1.2%, relative to what would otherwise be the case; in effect, all the cut would be spent. This sounds good.

But put this into another context. £12bn is around 0.8% of this year's GDP. If employment rises proportionately to spending, it too will rise by 0.8% - equivalent to just over 230,000 jobs. Which is less than one-tenth of current unemployment.

And this probably overstates the employment impact. A lot of that rise in consumer spending would come simply because consumers pull forward spending from 2013 into 2012. It's unlikely that employers would create permanent jobs in response to what they'd believe to be temporarily higher demand. More likely, they'd just work their existing employees harder. Productivity would rise, but not so much employment.

The effect of a temporary income tax cut would be even smaller. Knowing the cut to be temporary, households would respond by saving more or paying off debt; the permanent income hypothesis is about half true (pdf) . Consumer spending would thus not rise much. Alan Blinder has estimated (pdf) that temporary tax moves are only half as effective as permanent ones.

This poses the question: why isn't Balls proposing more radical measures? I can think of two macroeconomic arguments:

1. Our economic weakness is only temporary and the economy should recover next year, so the stimulus should be withdrawn then. This would be the case if our present woes are due to business confidence being depressed by the euro area debt crisis, which might be resolved this year.

But this argument is not wholly convincing. It could be that the weakness is more permanent - say because of a dearth of investment opportunities. And the withdrawal of a fiscal stimulus should be state-dependent, not time-dependent; it should come when the economy recovers, not merely when time passes.

2. Bond markets would take fright at a permanent easing, and the subsequent rise in interest rates would offset the fiscal stimulus.

There are two competing replies to this. One would be that if market sentiment is so fragile, it might take fright at a one-off rise in debt too. The other is that the shortage of global safe assets - and failing that the power of the Bank of England to buy unlimited amounts of gilts - should keep rates low, in which case a "permanent" expansion is feasible. It's not clear to me that there's much room for Balls' midway position here.

Instead, I fear there's another reason for Balls' timidity. The coalition has successfully shifted the Overton window in favour of austerity so much that a call for fiscal expansion is no longer seen as "credible"; academic economists are powerless to prevent this shift. This puts Balls into an awkward position. As a member of the political class trying to appear "credible" to the media he cannot call for more radical policy action. But as a member of the Labour party, he cannot acknowledge either that this constraint (among others) means that policy-makers cannot offer anything close to full employment.

February 17, 2012

A cost of immigration

Immigration is almost always discussed in terms of its impact upon the host country. This is, of course, only a part of the story. There's also the question: what does immigration do to the migrant himself?

The answer is: not all good. A new paper by Alan Barrett and Irene Mosca has found that alcohol abuse is far more prevalent amongst older Irishmen who had spent time living overseas than it is amongst men who had never migrated. For men over 50, 15% of those who had spent one to nine years living overseas have a drink problem - twice the prevalence among men who never migrated.

In itself, these numbers aren't conclusive. People who have migrated are more likely to have been sexually or physically abused as a child, and it could be this abuse that is a common cause both of their migration and their drink problem. But Barrett and Mosca find that, even controlling for this - among other things - migrants are still more likely to have alcohol trouble.

Alternatively, it could be that migrants who have returned to Ireland are those that failed to settle, and this failure explains their trouble. But this is not so. Irishmen who stay in England are also more likely to be heavy drinkers than Irishmen who never migrated; the maudlin Irish drunk used to be a staple figure in North London pubs, and maybe still is.

Instead, this is consistent with the idea that migration carries a psychic cost. Migrants are often isolated, alienated and suffer some form of discrimination, which leads to worse (pdf) mental health.

This, of course, is a longstanding theme of folk music. Such bluegrass standards as Blue Ridge Mountain Blues, Old Home Place and Are You From Dixie all describe a yearning to return home. Bob Dylan picked up this old story:

I pity the poor immigrant,

Who's strength is spend in vain,

Who's heaven is like ironsides,

Who's tears are like rain.

I'm not sure if this amounts to a case for immigration controls on libertarian paternalist lines - much as I'd like to see a politician say "Immigration's good for us, but we're restricting it because we're worried about the well-being of migrants." Instead, I'd draw two inferences.

One is that what we're seeing here might be an example of how (some) people - probably only some - mis-predict (pdf) their own tastes. They move in the hope of getting a better income whilst under-estimating the drawbacks of this in terms of greater alienation. This is one reason why we should not regard, say, the migration from country to city in developing countries as necessarily in itself welfare-enhancing.

The other is that the worse mental health of migrants might be in part due to the host country's suspicious attitude towards them. Which increases the argument for greater tolerance.

February 16, 2012

Unemployment, well-being and capitalism

The call for "joined up government" is an old one. It should apply - but doesn't - to the coalition's attitude to the unemployed.

Cameron has said: "I do believe government has the power to improve wellbeing." If this is so, then you'd expect a big part of public policy to focus upon how to improve the well-being of the unemployed. This is because these are, on average, significantly unhappier than other people - even the divorced - and it is probably easier to make the unhappy averagely content than it is to make the happy ecstatic.

But the coalition is not obviously solicitous towards the well-being of the unemployed. It prioritizes placating ratings agencies over creating jobs; its lackeys insult those who have suffered unemployment; it harasses the unemployed into workfare even though such schemes are of questionable efficacy; and it does little to combat a mindset that sees the poor, rather than poverty, as disgusting.

This inconsistency between a concern for well-being and a lack of concern for the unemployed is not, however, simply an intellectual failing. It reflects the fact that capitalism* requires that there be not just unemployment but that the unemployed be unhappy. I say so for three reasons:

1. Capitalism requires an excess supply of labour in order to bid down wage growth and industrial militancy. When Norman Lamont said unemployment was a "price well worth paying" to get wage inflation down, he was just blurting out the truth seen by Kalecki 50 years earlier - that "unemployment is an integral part of the 'normal' capitalist system."

2. Capitalism needs the unemployed to look for work - to be an effective supply of labour. This requires that they be "incentivized" to seek jobs by meagre unemployment benefits and by being stigmatized. In other words, the unemployed must be made unhappy.

3. Blaming the unemployed for their plight serves a two-fold function in legitimating capitalism. It distracts attention from the fact that unemployment is caused by structural failings in capitalism, sometimes magnified by policy error. And in promoting the cognitive bias which says that individuals are the makers of their own fate, it invites the inference that, just as the poor deserve their poverty, so the rich deserve their wealth.

In short, in terms of attitudes and policies towards the unemployed, there is an ineliminable tension between capitalism and the promotion of well-being.

* Note to right-libertarians. By "capitalism" I do NOT mean "free market economy" but rather a system in which large companies are run for profit by hierarchical structures for the benefit of a minority of people (which only sometimes includes shareholders).

Why not fiscal policy?

Simon Wren-Lewis suggests there might be "other motives at work" than macroeconomic reasoning for the government's refusal to consider using fiscal policy to combat rising unemployment.

If he is anything like the Oxford macroeconomics lecturers of my day, he is hinting at Michal Kalecki's 1943 paper, Political Aspects of Full Employment:

Under a laissez-faire system the level of employment depends to a great extent on the so-called state of confidence…This gives the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy: everything which may shake the state of confidence must be carefully avoided because it would cause an economic crisis. But once the government learns the trick of increasing employment by its own purchases, this powerful controlling device loses its effectiveness... The social function of the doctrine of 'sound finance' is to make the level of employment dependent on the state of confidence….

'Discipline in the factories' and 'political stability' are more appreciated than profits by business leaders. Their class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view, and that unemployment is an integral part of the 'normal' capitalist system.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers