Chris Dillow's Blog, page 181

April 4, 2012

Demand or productivity?

Duncan worries that economists might be "misdiagnosing a serious demand problem as a productivity problem." It could be, he says - endorsing Bill Martin's view (pdf) - that productivity growth has been weak recently not because of a supply-side problem but because weak aggregate demand has caused firms to hoard labour.

This is not merely an abstruse technical argument. It matters politically. The view that we have a supply-side problem has two implications:

- it implies that the output gap is small, which in turn implies that a large part of government borrowing is structural rather than cyclical. The case for fiscal tightening is thus stronger.

- if our problem is on the supply-side, then the policy remedies are less likely to involve fiscal expansion and more likely to entail supply-side reforms which - given the dominant neoliberal ideology - mean incentivizing bosses and bashing workers.

But are Duncan's worries correct? Two things make me sympathize with him. One is that I'm an old git who's been here before. I remember in the early 80s worrying that the then-mass unemployment would lower future growth through hysteresis effects. And I remember the better times of the late 80s and late 90s leading people to revise up their estimates of trend growth. History tells me that estimates of potential growth are pro-cyclical.

I'd add another reason why this might be so. It could be that the banking crisis, allied to the cyclical element of firms' reluctance to invest, has slowed down the entry (and exit) of new establishments which is a major cause (pdf) of productivity growth.

On the other hand, however, three things make me doubt this:

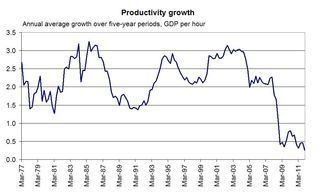

1. Productivity growth was slowing down before the recession. In the five years to December 2007 it grew by less than 2.3% a year. That's below the post-1990 average, despite what should have been a boost from a cyclical upswing.

2. Inflation has consistently been quite high since the recession began. This is consistent with the possibility that the output gap is indeed small - though as Simon says, there might be other reasons for this.

3. Even insofar as low productivity is a result of the recession, it doesn't necessarily follow that fiscal stimulus alone will raise it. If low productivity growth is due to the failure of the banking system to promote the start-up and expansion of new and (potentially) high-productivity business units, then a fiscal expansion that is unaccompanied by banking reform might not greatly raise productivity.

Rather than take a Keynesian or neoliberal supply-side view here, can I suggest an alternative? It's that, insofar as the slowdown in productivity growth is not cyclical, it reflects not the problems traditionally identified by neoliberals, but others, such as:

- the dearth of monetizable investment opportunities has lead to slower capital formation which inevitably means slower productivity growth.

- there are limits to the extent to which top-down managerialist organizational structures can identify productivity improvements and motivate workers, and we are bumping up against these limits.

- the UK banking system has always been poor at facilitating productivity-enhancing activity, and it is especially so now.

Insofar as these factors lie behind the productivity slowdown, the solution is neither Keynesianism nor orthodox supply-side reforms, but something else.

April 3, 2012

Unrepresentative, or unknowing?

Galloway's victory in Bradford West has prompted agreement that the political class is out of touch. Michael Portillo has said that politicians are separated from others by virtue have having been to "academically rigorous" institutions and that politics has become more professionalized. And Owen Jones has said that "We need not just the Labour party but the political establishment generally to be representative of the society around it."

This misdescribes the problem. Listening to Portillo, you'd think that politicians were pointy-headed technocrats. But this is not so. The problem with politicians is not that they all went to Oxford. It's that they give little impression of having learned anything whilst they were there. We have a government that is pig-ignorant of basic social science, that is unquestioningly deferential to securocrats; and which thinks tax simplification is all about VAT on pasties. And yes, Labour was little better.

Edmund Burke famously argued that MPs should not merely represent their constituents but should instead exercise judgment on their behalf. Our problem is that they are as incapable of the latter as of the former.

The question is: why is this so?

One answer would be inspired by Hayek, Kahneman, Simon and Homer-Dixon, among others. This says that there's an ingenuity gap; humans - especially those at the top of hierarchies - just lack the knowledge and rationality to tackle important but complex social problems such as poverty, mass unemployment, the investment dearth and the squeeze on living standards.

Another, more Marxian, answer is that potential solutions to such problems are ruled out even of consideration because of the political power of the ruling class and the ideology which capitalism generates.

Whatever the explanation, the upshot is that the political class - which, remember, includes much of the media - is reduced to bumbling around dealing with trivia. And I don't think things would be much different if MPs were influenced more by Gorton than Girton.

April 2, 2012

False consciousness

Norm criticizes Eliane Glaser's discussion of false consciousness. I'm not happy with either side of the argument.

Norm says false consciousness has acquired a bad name because of the way it has been used politically in defence of authoritarian politics. This is true, but irrelevant. We should judge ideas by their empirical validity, not by their consequences. People either have false consciousness or not, whether you like it or not.

But I'm not happy with Ms Glaser's view either. She says:

Members of the upper echelons of our society act against their interests too. Lots of doctors drink too much, and bankers spend their cash on tat.

This threatens to reduce the idea of false consciousness to a mere matter of taste. One person's "tat" is another's art. It surely is not helpful to ascribe false consciousness to anyone who lacks our fine aesthetic judgments.

My bigger gripe, though, is that Ms Glaser seems to equate false consciousness with being "hoodwinked and manipulated by political and corporate elites." This, though, is not the only way in which people acquire "false" beliefs. The can arise from systematic cognitive biases. Here, for example, are four ways in which such biases might generate a mindset excessively supportive of capitalist inequalities:

1. The status quo bias leads people to prefer existing evils; there's a reason why "better the devil you know" is an old saying.

2. The optimism bias leads people to over-estimate their future incomes and so oppose (pdf) redistributive taxation by more than they would if they had more accurate expectations

3. The just world illusion leads people to look for, and find, justifications for injustice.

4. A mix of the halo effect and outcome bias causes people to under-rate the role of luck and over-rate the role of agency when thinking about successful people. This leads to excessive deference towards rich businessmen.

But does all this amount to false consciousness? Not necessarily, for two reasons.

First, to know what false consciousness is, we must know what true consciousness is. And this we do not know. It is, of course, another cognitive bias (overconfidence) to think that true consciousness is what we happen to believe.

Secondly, just because beliefs are irrational does not suffice to show that they are wrong. It might be - given that a viable alternative to capitalism is not (yet) on the table - that people are right to support capitalism, even if they do so for the wrong reasons.

There is, though, a paradox in all this. On the one hand, research into cognitive biases has been fashionable in recent years. And yet on the other, as Eliane says, "false consciousness has disappeared from political debate." Do the above reasons suffice to explain this paradox, or is something else going on?

March 30, 2012

Remember unemployment?

Here are two recent findings on the link between unemployment and well-being.

First, in paper presented to this week's RES Conference, Clemens Hetschko that when unemployed men retire, they enjoy a big rise in well-being - even larger than that enjoyed by people getting married. This suggests that the unemployed are unhappy not just because they lack income, but because they feel stigmatized; when this stigma ends - nobody expects the retired to work - their happiness rises.

Secondly, Andrew Clark and Yannis Georgellis show not only that unemployment reduces well-being, but also that people do not adapt to it. People who become unemployed get unhappier the longer they are unemployed. In this sense, unemployment is worse than divorce or even widowhood, as people adapt to that and their well-being rises in the years after the event.

All this corroborates what we should know - that unemployment is a large and widespread source of misery. A political system that was serious about improving well-being would therefore have joblessness as its overwhelming priority.

Which our present system doesn't. Joblessness is just one issue jostling for attention alongside political donations and the price of pasties. And when it does get attention, our rulers only make it worse.

Is it really a surprise, therefore, that voters should opt for a dictator-loving charlatan rather than our main parties?

March 29, 2012

Cameron's consistent error

The government has been criticised for triggering panic buying of petrol. What's not been pointed out is that its mistake here is not an isolated one, but is in fact a common theme of some of its major policies.

Cameron said yesterday:

If there is an opportunity to top up your tank if a strike is potentially on the way, then it is a sensible thing if you are able to do that.

Topping up your tank is indeed sensible for any particular individual. But if everyone tries to do so, the result is chaos and petrol shortages.

What we have here, then, is an example of behaviour that is individually sensible but collectively self-defeating.

Cameron's advice thus represents a form of the fallacy of composition. He fails to see that what's rational for an individual might not benefit all individuals.

And as I say, this is not an isolated error. Take these examples.

1. Maria Miller, a minister at the DWP has said that there is a "lack of an appetite for some…jobs that are available.". Let's grant - heroically - that this is the case, and that she gets her way and the unemployed step up their job search. Some will find work. But in doing so, they'll merely get those jobs at the expense of other job-seekers; remember, there are around six unemployed for every vacancy. More intensive job search is rational for an individual - it increases their chances of getting work - but it isn't aggregatively beneficial, as it merely increases others' frustration.

2. The government has reformed benefits to "make work pay". This represents the same error Ms Miller makes. If one individual tries harder to get work, he might well succeed. But if all do, they don't*

3. The presumption that laid-off public sector workers can be rehired by the private sector might be true if you look at any particular individual public sector worker who can apply her skills elsewhere and take advantage of the vacancies that arise from the natural churn of the labour market. But it's much less likely if tens of thousands of such workers chase similar and limited private sector vacancies.

Social behaviour, then, is not simply individual behaviour writ large. In failing to see this yesterday, Cameron was repeating a consistent error of his government.

But why is? One possibility is that Tories believe in the most debased form of free market thinking - that what's good for the individual must always be socially optimal. Another possibility is that they just lack any feel for the social sciences, a large chunk of which is devoted to prisoners' dilemma-type problems where individual and collective goals conflict.

Whatever the explanation, the fact is that Cameron's remarks yesterday were not "misspeaking", but rather indicative of his government's failure of thinking.

* You might reply that the increased labour supply would force wages down and so create demand for workers. But even if this were true in theory, it is blocked by the minimum wage.

March 28, 2012

Capitalists on strike

The most significant fact in today's national accounts numbers is not the trivial downward revision to GDP growth. It is instead the fact that the UK's fundamental economic problem - capitalists' reluctance to invest - is as acute as ever.

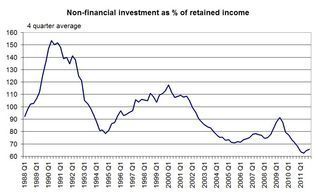

My chart shows that, last year, non-financial firms capital spending was equivalent to just 65.7% of their retained profits - the lowest share ever*. To put this another way, firms' desire to build up cash and/or reduce debt is at a record high - despite negative real interest rates.

Now, you might expect investment to be low, given weak aggregate demand and spare capacity. But my chart shows that capital spending as a share of retained profits was trending downwards before the recession. This suggests the reluctance to invest is a longish-term problem, reflecting the dearth of investment opportunities, and not just a cyclical one.

That said, I suspect this aggregate picture hides three separate things:

- Some firms are generating cash but lack investment opportunities - for either cyclical or secular reasons.

- Some, smaller, firms are forced savers, in that they'd like to invest but lack access to finance - though the Bank's credit conditions survey suggest this problem has declined since 2009.

- Some firms have been highly indebted and thus unable or unwilling to borrow; the corporate debt-income ratio is still above its long-term average.

I say this is our fundamental problem simply because it is capitalists' spending decisions that largely determine growth and employment. Also, the counterpart of firms being large net savers is that someone has to be a borrower - and that someone is the government; the public deficit is, to a large extent, the counterpart of this corporate surplus.

You can read this chart as a refutation of neoliberalism. Neoliberals thought that if only taxes could be cut and labour's bargaining power weakened, that capital spending would rise and economic growth follow. This has not happened. And it is, surely, unlikely that the corporate tax cuts Osborne announced in the Budget will significantly turn things around.

The question is: what, if anything, would turn it around? Yes, looser fiscal policy might give a cyclical kick to spending. But this doesn't address the long-term secular downtrend in companies' propensity to invest.

It might instead be that something more profound is happening. The difficulty of monetizing new innovations means that the profit motive is no longer sufficient to promote investment. This would be consistent with (though not proof of!) Marx's prediction that capitalism would eventually retard economic growth:

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production…From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution.

* My chart shows a small rise in this share recently. This is because retained profits fell in Q3, rather than because investment is picking up significantly. In Q4 alone, capital spending accounted for only 60% of retained profits, the third-lowest proportion on record.

March 27, 2012

On state funding of parties

The cash for Cameron affair, says Hopi, reignites the arguments for state funding of political parties. The economist in me finds the case ambiguous.

The case for state funding lies in the fact that private funding of parties is prone to a market failure identified by Robert Frank - that it produces too much competition.

A party's spending on an election campaign is a positional good, in that its payoff depends not on the absolute sum spent, but upon how much it spends relative to its rival; spending £20m succeeds (ceteris paribus) if your opponent spends £15m, but fails if it spends £25m.

This rank-dependence means that party funding becomes like an arms race, in which both parties compete too hard to raise funds, with socially sub-optimal consequences such as the danger of corruption. As Frank writes:

The dependence of reward on rank eliminates any presumption of harmony between individuals and collective interests, and with it, the foundation of the libertarian's case for a completely unfettered market. (The Darwin Economy, p11)

There's an analogy with drugs in sport. Under free competition, every athlete would have an incentive to take drugs. But if everyone does so, each individual's chances of winning doesn't change. All that does change is that athletes jeopardize their lives.

A cap on party donations works like a drugs ban in sport. It removes the unhealthy element of competition. The case for state funding is that the tax-payer must make up the lost money.

There are, however, three other considerations:

1. State funding would change politicians' incentives. The Telegraph says that "forcing taxpayers to pay for party politics risks making politicians lazy and out of touch." This, though, is not clear. If parties had to appeal for many small donations rather than a few large ones, they might actually try harder to stay in touch with the public.

Not that this is necessarily a good thing. If you take the Burkean view that politicians owe us not just their industry but their independent judgment, it might be no bad thing if they become out of touch with the populist mob.

The only point here is that incentives would change, and we should try to think how.

2. Political parties are not so much a public good as a public bad. They tend to limit the frame of debate - squeezing out worthwhile positions such as Marxism, libertarianism or anti-managerialism from public discourse. They encourage a narrow-minded tribalism. And they provide a career path for would-be MPs to become researchers and special advisors, thus encouraging the creation of a political class separate from the rest of society. These are negative externalities that should not be promoted with tax-payers' money.

3. A legal cap on donations is not the only way of preventing an arms race. As we saw on Sunday, a free, investigative press can also police party funding.

The economic case for state funding of parties is, therefore, not clear.

But the economic case is not all there is. There's also the matter of freedom. This speaks against capping donations - a man should be free to donate to a party, as long as he's not buying policy - and against using the tax-payers' money. I'm not sure if any argument is powerful enough to trump this.

March 26, 2012

Cash for Cameron: the Hugh Grant syndrome

My reaction to the news that businessmen paid to gain influence with Tory ministers is similar to my reaction when Hugh Grant was arrested with a prostitute: "I'm surprised he has to pay for it."

The truth is, of course, that business has for years influenced government policy - under Labour and Tory governments - even without money changing hands. For example:

- Because businessmen decide on investment and hiring - and thus determine economic growth - governments are keen to maintain "confidence". And this, as Kalecki said almost 70 years ago, "gives to the capitalists a powerful indirect control over government policy."

- Businessmen can exaggerate the extent to which capital and "managerial talent" are internationally mobile, and thus demand low taxes.

- Capitalists have long had the knack of giving the impression that their interests and the national interest coincide, whereas workers and the left have made "demands". Capitalists have thus presented themselves as more reasonable.

- Bosses present themselves as leaders and wealth creators, capable of transforming complex organizations. Politicians, wanting to learn this managerialist ju-ju themselves, have therefore deferred to the boss class.

Viewed from this perspective, the outrage in the reaction to "cash for Cameron" - insofar as it is genuine, which I doubt - is rather naïve. It reflects a belief that the state should somehow not defer to the interests of the rich. But it does.

March 25, 2012

Stagnationism, exhilarationism & beyond

Norm writes:

If a rightwing union-busting, welfare-eroding government openly assaults the living standards of working people, that presumably is an attempt, wise or otherwise, to manage the common affairs of the bourgeoisie by increasing capitalist opportunities for profit. If a reforming social-democratic government introduces labour legislation, a generous minimum wage, progressive welfare measures, that also is managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie, since a happier and healthier labour force will make capitalist firms function better.

Of course, both of these cannot be true at the same time. But they can both be true at different times. And a large part of the story of post-war economic history and our current malaise reflect exactly this.

The key question is: what is the link between capitalist investment (and hence economic growth) and profit margins?

In the 50s and 60s, the link was positive. Social-democratic efforts to main full employment tended to squeeze profit margins. But this promoted investment because low profit margins were accompanied by high (expected) aggregate demand and high profit rates; this is what Marglin and Bhaduri called a stagnationist regime.

But in the 70s, this broke down. The profit squeeze no longer promoted aggregate demand, so profit rates fell and investment and growth slowed.

The solution - which Thatcherism and neoliberalism stumbled upon in the 80s - was union-busting, welfare-eroding government. In creating mass unemployment, profit margins were restored and with them investment and growth. We had, in Marglin and Bharduri's words, an exhilarationist regime.

Which brings us to our current plight. The exhilarationist regime might have broken down, just as the stagnationist one did in the 70s. Neoliberalism no longer promotes investment. Between 1981 and 2001 - roughly, cyclical troughs - the volume of business investment rose 5.3% a year. But since 2001, it has grown just 0.1% a year. And even if the OBR's forecasts (pdf) are right, it will grow just 2.7% between 2001 and 2016.

This might reflect the fact that the UK, more than other economies, suffers from the failure of neoliberalism to no longer promote investment: the industry in which we have a comparative advantage - financial services - is in decline; our main trading partner, the euro zone, suffers long-term sclerosis; and endogenous growth considerations mean we cannot conjure a vibrant manufacturing base from very little.

This poses a question which is insufficiently appreciated: what lies beyond exhilarationism? The right's answer is: nothing. It assumes that tax breaks and diminishing the welfare state will re-ignite investment. The statist left's answer is that we're seeing a return to stagnationism, in which case fiscal expansion and wage-led growth will work. But what if they're both wrong?

March 23, 2012

Marx, capitalists & the state

Norm has chastised me for endorsing Marx's claim that "the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie." This raises the question: what counts as evidence here?

Norm is entirely right to say that there are "important functions of contemporary democratic states that are of more general benefit than to the bourgeoisie." But this does not refute Marx's claim. Because the interests of workers and capitalists coincide to at least some (large?) extent, the state can provide such general benefits whilst at the same time promoting capitalists interests. Take some examples from Norm's list:

- Capitalists require infrastructure such as roads and sewage systems, and an educated and healthy workforce. Public goods problems mean they won't provide these themselves, and that they cannot exclude others from them.

- Capitalists want their lives and property to be protected. The easiest way to do this is for everyone's basic rights to be so protected, whether they have property or not.

- The state can benefit capitalists by underpinning aggregate demand. It does so - among other ways - by spending on welfare benefits, overseas aid and defence.

- Capitalists need to protect themselves from ruinous competition. Some regulations, such as health and safety laws, work to the benefit of larger capitalists by imposing costs upon smaller firms. As Marx wrote of the Factory Acts, "Owing to the necessity they impose for greater outlay of capital, they hasten on the decline of the small masters, and the concentration of capital."

- Capitalism requires that there be social order and little threat of revolution. The state helps provide this through a welfare state, the provision of basic justice, laws to prevent excessive exploitation and so on.

In this context, I think Norm makes a leap too far when he says:

If 'the executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie', then democracy is no more than a facade and a pretence.

I disagree. Given that there's (for now) no alternative to capitalism, it's in all our interests that the "common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie" be well managed. Democracy, then, matters - not least because it allows us to choose (within limits!) between efficiency and justice.

But this brings me to my problem. In interpreting the "common affairs of the bourgeoisie" so widely, am I not in danger of making Marx's claim unfalsifiable, in the sense of being consistent with any act of the state?

No. Falsifying evidence would be state policies which deliberately attack the interests of capitalists. (I say "deliberately" because policy mistakes are common). How many of these are there?

One example I can think of would be the high marginal tax rates we had in the 1970s - though these, as we've seen this week, do not survive for long against capitalists' attacks.

This example alone suffices to suggest that Marx overstated the case when he said the state was "but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie". But was it really much of an overstatement? By the standards of social sciences - where any glib statement fails to fully capture the messy reality - I'm not sure it scores so badly.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers