Chris Dillow's Blog, page 178

May 13, 2012

Ordering effects, luck & rationality

I point out here that people's choices can be sensitive to arbitary differences in the order in which options appear. In the Eurovision song contest, for example, the first or later performers have more chance of winning than those appearing in the middle of the show. I omitted to add that this ordering effect also matters in politics. A new paper concludes:

Alphabetic ordering effects exist in the 1977 2011 Irish general elections. The effect is significant, in both a statistical and substantive sense. The estimated effect of being listed first on an alphabetical ballot paper in an Irish general election is approximately 544 first preference votes or 1.27 percentage points for the average candidate.

This corroborates findings from the US (pdf) and Australia (pdf).

Experimental evidence (pdf) suggests such an effect might exist in UK council elections if not general elections.However, it's worth noting that 191 of our 650 MPs (29.4%) have names beginning with A-E, compared to only 54 (8.3%) with names beginning U-Z.

And it's not just in politics that an early name has an advantage; in football, acting and , early names are more likely to scoop big prizes.

All this might sound quirky. But it's not. It has two implications.

One is that it confirms the message of Ed Smith's Luck. Success depends in (large?) part not (just) upon ability and hard work, but upon fortune. Clearly, the successful have an interest in denying this. But if luck operates through subtle, smallish and non-obvious mechanisms such as naming effects, they might not be fully aware of it.

Secondly, ballot order effects suggest that electoral outcomes are not entirely the rational will of the people, but are also influenced by luck. And if something as arbitrary as alphabetical order influences elections, how many other arbitrary or non-rational factors might also do so?

May 11, 2012

Economic freedom & social tolerance

Tim professes amazement that the Guardian's new human rights site ignores economic freedoms. This raises the question: what's the link between economic liberty and social liberties?

Highfalutin talk about freedom being indivisible isn't much help here, if only because so many folk think otherwise. For every Guardianista who favours gay rights but dislikes economic liberty, there's a Conservative with the opposite preference.

Nor is UK history much guide. If we compare now to the 1970s, we probably have more economic liberty, by Tim's lights, than we did then and there's less homophobia, sexism and racism. That suggests a positive relationship between social and economic freedoms. But if we compare now to the late 19th century, we have less economic liberty but more freedom for women and gays. That suggests a negative relationship between economic and social freedom.

Luckily, a new paper by Niclas Berggren and Therese Nilsson sheds some light here. In a cross-country study of 65 countries, they find that economic freedom is significantly positively correlated with tolerance of homosexuals, but has no significant link with racial tolerance. Cynics might say this is because the selfishness generated by economic liberty causes people to care about house prices more, and gay people help to raise these, but I suspect this isn't the only story.

Curiously, there are two particular aspects of economic freedom that encourage tolerance of gays. One is legal protection of property rights, and the other is low and stable inflation; a credible inflation target reduces homophobia. The size of government, openness to trade and extent of regulation seem irrelevant. The authors say:

Stability, safety and an expectation of fairness (in the legal and monetary systems) are conducive to not regarding others as threatening.

There's something here, I think, for everyone. On the one hand, Guardianistas can point to the lack of link between economic liberty and many aspects of tolerance as evidence that economic liberty is separate from many social freedoms. But on the other hand, economic libertarians can point to the fact that there's no evidence that economic freedom reduces social liberties, and some evidence that, in one respect at least, it increases them.

May 10, 2012

Danny O'Donoghue, meet game theory

For me, one of the most interesting economic issues of recent weeks is not Greece, or the failure of Osborne's fiscal austerity, or NGDP targeting, or any of that bigthink guff. It is Danny O'Donoghue's claim that The Voice will attract more talent next year than other talent shows.

I'm not sure. Let's grant Danny's premise that The Voice is more musically credible than the X Factor. Does it follow that the best singers will go into The Voice?

No. We can think of the problem facing singers as being much like the hawk-dove game, where good singers are hawks and poor ones doves: let's rename it the Kate-Jedward game.

If Jedwards know The Voice will be populated by Kates, they'll not enter as they know they'll lose.They'd prefer to compete against other Jedwards.

But think of the expected payoff to Kates from competing against other Kates. We can write it as p(Vv) - (1-p)Cv, where p is the probability of winning, Vv is the prize on The Voice and Cv is the cost of defeat on The Voice.

The problem here is that p is low, as Kate is competing against other great singers. It's not obvious that this would be offset by a more favourable Cv; the benefits of getting exposure on a more credible music show and being tutored by better people. It's quite possible, therefore, that for reasonable values of p, Vv and Cv, some Kates would rather go onto the X Factor, where p is higher as they'll be up against more doves.

But of course, if many Kates do this, p won't be much higher on the X Factor.

The solution here is for singers to use a mixed strategy. Some will enter the tough competition - The Voice - and some the easy one. The two can therefore co-exist. In this sense, Danny is wrong.

But there are (at least) two factors here which make things more complicated than a standard hawk-dove game.

One is that singers don't know their true ability or - what is not the same thing! - their chances of winning. Overconfident singers would prefer the show with the higher pay-off to winning, whilst underconfident ones would prefer the weaker competition. This might well cause overconfident Jedwards to enter The Voice whilst underconfident Kates enter the X Factor. This would reinforce the tendency for the two to co-exist.

The other problem is that in a standard hawk-dove game, the best thing for a hawk is to be the sole hawk in a field of doves. But this is not true in our case. The best thing for a Kate is to be up against enough other Kates to make a competition attractive to viewers, but not against so many as to dilute the chances of winning.The payoff to competing against other Kates is thus n-shaped in their number.

The issues here are - of course - not about TV shows, but about the economy generally. There are (at least) three implications here:

1.Apparently quite simple choices quickly become tricky when we allow for strategic interaction, uncertainty about probabilities, payoffs and costs and cognitive biases.

2. It is not always true that a stable equilibrium will arise if identical people, facing the same incentives, choose the same behaviour. Sometimes, stability arises only when apparently identical people faced with the same incentives actually behave differently.This applies to the banking system (pdf).

3.There are costs to competition. A mixed strategy, yielding a mixed population of hawks and doves is evolutionarily stable. But this only arises after a lot of hawks and doves have been killed by entering the "wrong" competition.

May 9, 2012

Openness in policy-making

The government has refused to publish the risk assessment of its NHS reforms, claiming that doing so "could harm the quality of future advice from civil servants." Andrew Lansley says:

There...needs to be safe space where officials are able to give ministers full and frank advice in developing policies and programmes.

This makes little sense to me. Think of this in terms of incentives: how would openness reduce civil servants' incentives to give full and frank advice? Surely, the knowledge that your thinking will be publicized increases your incentives to do better, simply because it imposes an extra cost - public derision - upon bad thinking.

The counter-argument, I suppose, is that some "full and frank" advice consists of devil's advocate-type arguments - outrageous thoughts intended to clarify issues. But such arguments could be flagged as such in the minutes.

There's some quasi-experimental evidence which I think favours transparency. There's one area of policy-making which, pretty much around the world, has become more transparent in recent years - monetary policy. And whilst lots of people have complaints about central bankers, nobody AFAIK blames their failings upon excessive transparency. If openness is good enough for monetary policy, why shouldn't it be good elsewhere?

In fact, there must be a presumption of openness, simply because it is voters who pay for policy. As Joe Stiglitz said in this marvellous lecture (pdf):

Information gathered by public officials at public expense is owned by the public.

What's more, there are at least four arguments against secrecy:

1. As US Senators Moynihan and Wyden said, it "breeds inefficiency by providing cover for the influence of special interests and opening the door to corruption and bribery."

2. It allows bad thinking to escape scrutiny.

3. It breeds distrust. The public will ask: "what have you got to hide?" At a time when politicians are already deeply distrusted, this danger is especially acute.

4. It is anti-democratic. It supposes that there is some information which is only safe in the hands of an elite, and with which the public cannot be trusted.

On this last point, though, perhaps Mr Lansley is onto something. Maybe the quality of public thinking and of democratic debate is so bad, so debased by cognitive biases or by media manipulation, that the risk assessment would be misinterpreted. And maybe the government's rhetorical and political skills are so scant that it cannot correct such misinterpretations. But this poses the question: do we really want to be governed by people who are both sceptical of the value of democracy and lacking in political skills?

There is, of course, another possibility. Maybe he really has got something to hide.

May 8, 2012

The left & shareholder activism

The resignations of Andrew Moss at Aviva and Sly Bailey at Trinity Mirror suggest that investors are becoming more intolerant of high pay for poor performance. However, I'm not sure if the Left should welcome this new shareholder activism.

For one thing, if shareholders do become fussier about who they employ as CEOs, pay could rise even further, as firms chase the (vanishingly) scarce talent to add value to a company.In this sense, inequality could actually increase.

And for no good reason. There's good evidence that heightened incentives - big pay for good performance and the heave-ho for bad - do not in fact improve individuals' performance. This could be because of the Yerkes-Dodson effect; people choke under pressure. Or it could be because extrinsic motivations crowd out (pdf) intrinsic ones, and incentivize conformity rather than creativity. Or it could be because high incentives merely encourage CEOs to game the system, for example by hitting earnings expectations by using accounting tricks rather than genuinely good management. A increased threat of the sack might merely intensify these adverse effects.

But even if shareholder activism does encourage managers to raise profits, it might not benefit the wider economy.

To a very large extent, aggregate profits are due not to individual firms' endeavours but to macroeconomic conditions. Many attempts to increase profits or cashflow - for example by cutting wage or materials costs or reducing investment - thus attempt to raise profits for one firm merely at the expense of others.

And it's possible that such attempts would be collective self-defeating. If all firms try to cut costs, all that happens is that aggregate demand falls. Just as there's a paradox of thrift, there's also a paradox of profits. This helps explain the curious fact that since the 1980s there has been increased emphasis upon shareholder value, and an increased demand for management - and yet there's been no obvious increase in trend GDP growth.

Yes, it's tempting for egalitarians to crow over the fate of Moss and Bailey. But let's be clear. The pursuit of shareholder value is not oviously something we should welcome.

May 7, 2012

Expectations: a weak lever

My claim that expectations are a weak lever for policy has been questioned. Nick says:

Expectations matter a lot for the demand for long-lived assets, and hence for the price of long-lived assets. The lower the rate of interest, the more expectations matter. What happens this year doesn't matter very much at all (unless it affects expectations of future years), and it matters even less as the rate of interest gets lower.

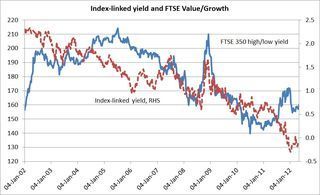

This seems reasonable. But it has an implication which doesn't always fit the facts. It implies that as long-term real interest rates fall, the price of "growth" stocks should rise relative to value stocks. This is because growth stocks - by definition - are expected to offer more future cashflows than value ones, and lower interest rates raise the value of future cashflows. But my chart shows that this isn't always so. Between 2007 and 2010, growth stocks did indeed out-perform as index-linked yields fell. But since 2011 they have not done so. This tells us that the link between longer-lived assets and interest rates isn't as simple as theory tells us. This might be because the stock market is short-termist (pdf) and so longer-term expectations just don't matter much.

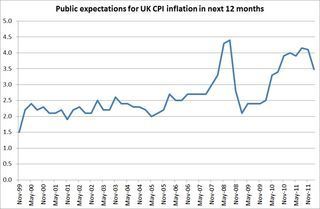

This, though, was not the main point I had in mind. I was thinking instead of my second chart, which shows NOP's survey of the public's expectations for inflation in the following 12 months.This chart shows three things:

1. Expectations are not well anchored to the 2% target. Instead, as Adam Posen has said (pdf), they are determined more by the recent data. This poses the question: if the inflation target does not much affect short-term inflation expectations, why should we suppose that an NGDP target would much affect short-term NGDP expectations?

2. Inflation expectations have been above 3% since May 2010. This implies that the public has expected sharply negative real interest rates. But this has not led to the rise in consumer spending that theory predicts.In January 2011, the consensus expected real consumer spending to grow 1.2%. In fact it fell 1.2%.

3.Nor have high inflation expectations led to higher wage growth; average earnings have risen 1.4% a year in nominal terms in the last two years.

These three facts imply that there are two weaknesses in the expectations lever; the Bank cannot easily affect short-term expectations, and such expectations don't obviously have the effects on macroeconomic aggregates that one might think.

Now, I agree that, in theory, policy credibility matters. And I don't doubt that there are times and places when policy-makers can affect expectations; I suspect they have more influence upon financial market expectations than real people's. I fear, though, that economists who invoke "expectations" and "credibility" are making the error of mistaking the tidy maps of models for the messy terrain of reality.

I do not say this to reject NGDP targets. Instead, it is to say that - insofar as these have merit for the UK economy here and now - it is because they would lead to a greater monetary stimulus, rather than because they would affect expectations and hence behaviour.

May 6, 2012

The media vs bloggers

As one of the more, ahem, seasoned bloggers, I can remember when mainstream journalists looked down upon us as "socially inadequate" angry ranters who were no replacement for serious journalism. But I'm starting to think that the opposite is increasingly the case. It is mainstream journalism that comprises linkbait (Samantha Brick), trolls ("Rod" Liddle, A.A Gill, The Mail's nastiness towards female celebs) and shallow self-absorbed diarists, whilst many bloggers are serious, intellectual and high-minded.

I suspect there are two pressures which might amplify the tendency for bloggers to go "up market" and the mainstream media down.

One is incentives. Many bloggers blog in order to build a reputation, whereas the paid media needs eyeballs. Linkbait that attracts eyeballs - if only ones connected to brains which think "this woman is a moron" - are good for the media, but no use to a blogger who wants to advance a reputation for intelligence. The (I fear distant) possibility that academics will get professional credit for blogging would exacerbate this difference.

In this context, we shouldn't bemoan newspaper paywalls too much. The virtue of these is not so much that they finance serious journalism, but rather than they disincentivize trolling and linkbait.

Secondly, there's the tendency for people to specialize in what they are best at. Mainstream journalists have an advantage over bloggers in some things - such as celebrity and Westminster gossip - but a disadvantage in other respects; such as their excessive deference and ignorance of statistics. This creates a space for intelligent blogging.

Now, of course, it would be silly to exaggerate and pretend that bloggers are all pointy-headed highbrows whilst the MSM are all trolls. Instead, I suspect blogs are a little like the BBC. There's a lot of rubbish, but the structure of incentives is such as to facilitate a minority of great work to a greater extent than is the case for the capitalist sector.

May 4, 2012

Jobs trouble

The NIESR forecasts (pdf) that unemployment will rise to almost 9% of the workforce later this year. Whilst I'm no fan of economic forecasts, there's a reason to fear it might be right. My chart shows it.

It shows that during the worst of the 2008-09 recession GDP fell far more than employment; although it was a severe recession for output, it was a relatively mild one for jobs.

We can (horribly!) roughly quantify this. If the relationship between GDP growth and employment growth had been the same since 2007Q4 as it was in the previous 20 years, the 4.3% drop in GDP since then would have caused a 3.3% fall in employment. But in fact, it fell only 1%. This means that employment is almost 700,000 higher than you'd expect, given what's happened to GDP.

Now, to some extent, this reflects a genuine slowdown in productivity, and to some extent labour hoarding. Insofar as it's the latter, we should expect two things. Some firms will respond to rising demand by increasing utilization of labour and unwinding this hoarding, rather than increasing hiring. And others, if they fail to get the recovery in demand they hope for, will trim their workforces.

On both counts, a rise in aggregate demand might not generate many net jobs.

There's a precedent for this. In the early 80s, GDP bottomed out in 1980Q4 and recovered thereafter, but it was not until early 1987 that employment returned to its 1980Q4 level.

Now, I'm not saying the jobs picture is that bad. But that episode is a warning - that even if we do get a nice recovery in output (which is a big if), jobs need not follow.

May 3, 2012

Policy utopianism

Criticism of Sir Mervyn King for his role in the banking crisis and calls for a nominal GDP target have something in common. And it's something I'm a little uncomfortable about.

What I mean is that they both have - in their more extreme forms - a tinge of utopianism, in two senses.

First, there seems an optimism about what policy can achieve. This is questionable. For example, any form of bank regulation is prone to the problem of asymmetric information - regulators know less than insiders and cannot spot bubbles in lending - and, consequently, of regulatory capture. The idea that the banking crisis might have been prevented is idealistic. Criticizing Sir Mervyn for not doing so is no more enlightening than pointing out that he's only human.

Similarly, NGDP targeting is apt to fail because a target requires a forecast and forecasts go awry at important times simply because the economy is inherently unpredictable. NGDP fell in 2008-09 not so much because the Bank was targeting inflation instead, but because it just didn't see the slump coming sufficiently far in advance to loosen policy enough.

Secondly, there seems to me an implicit presumption that, if only policy were correct, problems within the private sector could be overcome. This too is doubtful. Banks did not fail merely because they were badly regulated, but because there were (among other failings) principal-agent problems between shareholders and managers that encouraged excessive leverage and risk-taking. In other words, there was a faultline in the private sector that (conventional?) regulation, at best, could only have painted over.

Similarly, reading some calls for NGDP targeting gives me the impression that it is all we need to get full employment. I doubt this. Unemployment exists not just because of deficient demand or sticky wages (which are less (pdf) important than thought) but for other, more intractable reasons: efficiency wages, signaling problems, the shortish-run non-fungibility of labour, lack of skills or the vested interests of capitalists.

Now, I realize that I might be attacking a straw man here. I'm quite open to the possibility that policy can be improved upon, and I don't doubt that more QE - the likeliest tool of an NGDP target - would create some jobs. What I don't like is the idea that there's some magic wand of policy that can solve our problems. And what I like even less is that such talk serves a nasty ideological function, of deflecting attention from the inherent shortcomings of private sector capitalism.

May 1, 2012

The wage & profit squeeze

What is happening to profits and wages? On the one hand, Labour complains about the squeezed middle whilst the broader left complains about the fall in the share of wages in GDP since the mid-70s. But on the other hand, Allister Heath says the situation for corporate profits is "horrendous."

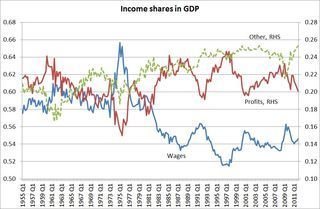

So, who's right? The answer is: both, to a point. My first chart shows income shares since quarterly ONS data began in 1955*. This shows three things:

- The wage share fell between 1975 and 1997, but recovered thereafter, only to slip back since 2009.

- The profit share tends to be cyclical, but is slightly higher now than in the low-points of the downturns of 1975, 1981, 1992 and 2001. These numbers, though, include the profits of oil companies, so might overstate the health of the non-oil sector.

- Other incomes (rent and net taxes on production) have trended upwards. They jumped after 2009, I suspect because of the rises in VAT. In this sense, both capitalists and workers have suffered because the other incomes wedge has risen.

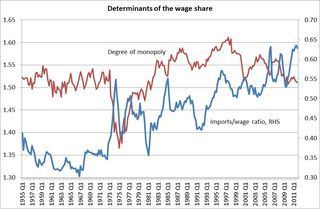

We can look at this another way. Back in 1938 Michal Kalecki proposed a simple framework for thinking about the share of wages in GDP.

Start from the national income identity that GDP equals wages (W), profits (P) and other incomes (O), and also equals gross final expenditure (what he called proceeds) minus imports (M). This means:

P + O = (k-1)(W+M)

where k is the ratio of proceeds to (W + M). He called this the degree of monopoly. You can think of it as the mark-up over costs**.

This means we can write the wage share as:

w = W/W + (k-1)(W+M)

If we let j = M/W, then this gives us:

w = 1/1+[(k-1)(j+1)]

In other words, the wage share moves inversely with the degree of monopoly, k, and the import-wage ratio, j. This is an identity. My second chart shows moves in these since 1955.

You can see that the import-wage ratio has trended upwards, reflecting the increasing globalization of the supply chain. But within this, there have been spikes, due in large part to jumps in oil prices.

The degree of monopoly slumped in the 70s, as wage militancy squeezed profits, but trended upwards until 1997 since when it has trended downwards.

You can think of this as the interplay of two factors. On the one hand, the fact that capitalists have increasingly had the whip hand over labour has tended to raise the degree of monopoly. But on the other hand, international competition has tended to erode their monopoly. Since the mid-90s, the latter force has predominated.

This chart tells us that since the mid-00s, the import-wage ratio has risen, thanks I suspect to higher commodity price whilst the degree of monopoly has fallen. This means wages have been squeezed by higher oil prices, rather than the power of capitalists.

The bottom line here is simple. Both capitalists and workers have cause for complaint. Capitalists have lost pricing power - the degree of monopoly has fallen - which has tended to depress the profit share. But this has not benefited workers because instead the "wedges" of other incomes and higher imports have depressed their share.

* The numbers come from tables C1 and D here. GDP is YBHA, imports are IKBI, wages are DTWM and profits are CGBZ. For my purposes, all the other numbers are derived from these.

** You might object that imports are not a cost for capitalists to the extent that they comprise consumer goods. You'd be wrong. If workers buy domestic consumer goods, their wages are not a cost to capitalists in aggregate. This is because what they lose through the back door in higher wage costs is recouped through the front in higher spending. If, however, workers spend their incomes overseas, then wages are a net cost. In this sense, all imports are a cost to UK capitalists, either directly (imported materials) or indirectly.

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers