Chris Dillow's Blog, page 180

April 18, 2012

Why are incomes squeezed?

Today’s figures show that the squeeze on households’ real incomes is continuing. Wages rose by only 1.1% in the year to the three months ending January, whilst yesterday’s numbers showed that prices have risen faster. This poses the question: does this squeeze on real wages mean that capitalists are winning the class struggle? The answer is: yes and no.

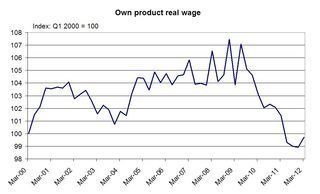

One useful measure here is the own product real wage - wages divided by the product of productivity and prices. This captures the two different ways in which capitalists can increase their exploitation of workers. One way is to reduce wages relative to prices. The other is to make workers work harder for a given real wage - to raise productivity.

My chart shows the OPRW, based upon average earnings divided by the product of the CPI and GDP per hour*. You can see that since the end of 2008, the OPRW has fallen - largely because prices rose by 10.8% whist wages rose only 4.2%.

However, its possible that the OPRW rose in Q1; I say so because the 1.4% rise in hours worked in the latest data imply that productivity fell.

What’s more striking, though, is that the post-2008 drop in the OPRW merely reverses the rise that occurred in the mid-00s.

In the mathematical sense, there’s a simple reason for this; in the five years to December 2008, real wages rose 10% whilst productivity grew by just over 2%.

Now, although I have written this in crude Marxist terms, the implication is not so crudely Marxist. What this means is that, viewed in a longer-term context, the problem of the “squeezed middle” is not so much that workers are being ripped off by high price rises. Instead, the problem is that productivity growth has stagnated for some time, and lower productivity growth must mean lower growth in real incomes for someone. In the mid-00s, workers escaped this - perhaps thanks to the temporarily relatively tight labour market then. But now, they are paying the bill. Given that mass unemployment has tipped the balance of class power in favour of capitalists, they might continue to do so.

* It starts in 2000 because this is when the ONS’s current series on average earnings begins. For the purposes of this chart, the state counts as a capitalist, because the CPI includes taxes and duties and because wages include those of the public sector.

April 17, 2012

Does personality matter?

Does personality matter in economics? Two new papers suggest not, or at least not much.

First, Julia Muller and Christiane Schwieren got people to play a trust game, in which one player (the trustor) is given some money and invited to choose how much to share with player 2, the trustee. Any gift is tripled, and the trustee then chooses how much to return.

They found that among trustors, there were correlations between the amounts they chose to give and some of the “big five” personality factors. An inclination to trust - give money to player 2 - was positively correlated (0.28) with agreeableness and negatively correlated with conscientiousness (-0.26), as well as with anxiety. Correlations with other big five factors were insignificant. And personality factors taken together explain around a quarter of the variation in trustors’ behaviour. I don’t know whether this is a lot or a little.

However, among trustees, there were no correlations between measured personality characteristics and the amounts returned. The only (very) significant predictor of the amount returned was the amount received; if people got a lot, they gave a lot.

A paper by Armin Falk and colleagues largely corroborate this. They used lab experiments to test for links between personality factors and time preference, risk aversion, trust, reciprocity and altruism. And they found weak correlations. For example, there’s a negative correlation between neuroticism and risk appetite, but only -0.12, and a positive correlation between agreeableness and altruism, but only 0.2.

They also used a different data set to look for links between wages and personality factors amongst Germans. They found that openness and, to a lesser extent, conscientiousness are positively correlated with higher wages, as are having an internal locus of control and being more inclined to trust people; see also this paper by James Heckman and colleagues. Altruism, extraversion and agreeableness are associated with lower wages; the latter corroborates a finding from the UK. However, only around 10% of the variation in wages is explained by observable personality factors.

I reckon there are (at least) two interpretations of all this. One is that personality factors are dispositions which are only weakly correlated with actual behaviour. A generous man on a bad day will be mean, a neurotic one on a good day will take a risk, and so on.

The other possibility is that Marxists (and neoclassical economists!) have a point. Behaviour is determined more by the situation we are in than by our character. When we impute character as an explanation of behaviour - as when we infer that successful men are highly motivated or that ones who give to charity are generous - we are committing the fundamental attribution error, of overweighting personality and underweighting the environment.

April 16, 2012

The tolerable cost of austerity

The Ernst & Young Item club reckon that, although the economy has escaped recession, it will grow by only 0.4% this year.

If this is right, it would mean that real GDP at the end of this year will be 4.4% less than the OBR forecast (pdf) in June 2010.

We can’t blame the euro crisis for this. For one thing, exports have held up relatively well, so far. And for another thing, one argument against austerity was and is that it gives us less “wiggle room” if the economy does suffer shocks.

Instead, the natural inference is that Osborne’s fiscal austerity has been more expensive than anticipated. One estimate of this extra cost is equivalent to £150 per month per household*.

This poses the question. If austerity has been significantly more costly than expected, why hasn’t it caused more public outrage, and more doubts about its efficacy amongst coalition supporters?

I suspect there are two reasons.

One is the status quo bias. Costs that are actually incurred by existing policies are often more tolerable than the same costs considered as potential effects of alternative policies. This bias causes people to tolerate policies which they might have rejected, had they known their actual costs.

It’s not just UK austerity for which this is true. If you had told Spaniards and Greeks that joining the euro would cause a short-lived housing boom and then years of stagnation or worse, they might well have rejected the idea. But now these costs are being borne, people are (more or less) putting up with them.

A second reason lies in the “painting the target” effect. If you fire a bullet into a wall, you can paint the bullseye onto the wall, and then claim to have hit it. In this way, supporters of austerity point to low gilt yields and claim the policy has averted a debt crisis - oblivious to the fact that low gilt yields are largely a reflection of weak economic activity.

Again, there’s nothing unusual about today’s austerity here. A similar post hoc rationalization is often applied to the Thatcher recession of 1980-81. This was not supposed to happen. The hope was that monetary targets would lead to lower inflation expectations and hence to lower inflation without a serious recession; for this reason David Smith wrote that “by the end of 1981, Britain‘s monetarist experiment appeared to have been an unmitigated disaster.” (The Rise and Fall of Monetarism, p105) It is only with hindsight that we credit Thatcher with breaking workers‘ power, thus enabling a recovery in capitalists’ animal spirits and investment. But this is a “painting the target” syndrome.

These thoughts might seem mundane. But they have an important implication. If costs and benefits, once borne, are regarded very differently from how we’d regard them in anticipation, then what use is cost-benefit analysis?

* GDP in Q1 was probably 3% below the OBR’s June 2010 forecast. That’s around £11.8bn (money GDP in Q4 was £380.5bn.) There are 26.3m households in the UK, and £11.8bn divided by 26.3m gives us £448.67. Divide by three and we can call it £150.

April 15, 2012

Abolish Budgets

The continued criticism George Osborne is getting for his proposal to limit tax relief on charitable donations highlights something many economists have thought for years - that we should abolish annual Budgets.

Osborne is, of course, not the first Chancellor to have gotten into a pickle such as this; remember Brown’s 75p rise in old age pensions and his abolition of the 10p tax band?

The problem is that the tax and benefit system is so complex, and Budgets contain so many different proposals - kaleidoscopes of trivia - that individual chancellors, surrounded by tiny groups of like-minded people, cannot fully anticipate their effects. Bounded rationality plus groupthink equals bad policy-making.

The solution is simple. Budgets should be first words, not last ones. Tax policy should be a matter for consultation, review and deliberations, not for individual statements from on high. The Budget statement should be the introduction of a green paper.

This is, of course, not a new idea. The IFS’s Green Budgets are intended to be a model for such policy-making. And we had hoped that when Brown introduced Pre-Budget Reports in 1998 that they would become the start of consultation exercises - though they swiftly became mere mini-Budgets.

Now, I suspect that most of you will regard all this as trivial common sense. However, what’s at issue here is two very different conceptions of politics. We have a conflict between politics as rational, deliberative policy-making versus a politics of theatre in which “great men” determine the nation’s economic destiny. It says something about our political system that rationality should be such a radical idea.

April 13, 2012

"Political reality" and political change

Tim says that Keynesianism doesn’t work because “there’s just no way, given political reality“ that governments can run large and sustained budget surpluses during booms.

Such a view is widely shared; it‘s one reason why euro area finance ministers want to impose fiscal discipline through constitutional rules, rather than rely upon states‘ discretion.

But it’s not just Keynesianism that is ruled out by “political reality”. As Philip Booth points out, political reality also makes lost causes of lots of policies beloved of classical liberals such as Tim. There’s little hope of liberal policies on immigration, drugs or prostitution. I suspect a flat tax is impossible because of the irresistible demands - reasonable and not - for loopholes, favours and reliefs. And there’s not much chance of massive public spending cuts, given the power and interest of bureaucrats to resist them; one of the paradoxes of libertarianism is that one of the research programmes it inspired - public choice - does much to show why libertarianism is doomed to fail as a political strategy.

I say all this not to sneer at Tim, but rather to raise a question about the nature of political change.

Part of me wants to say that a flaw in classical liberalism - regardless of its other merits or demerits - is that it places too much faith in the power of reason, as defined by its own (perhaps dim) lights. Just as some soft lefties think the world would be better if we were less greedy, so classical liberals give the impression that it would be so if only folk were more “rational.“ Both are utopian. And both can be contrasted to Marx’s view that revolutions require not (just?) people to be nice and rational, but instead a powerful constituency with an interest in achieving change. Classical liberals have no such constituency.

But that’s what half of me thinks. Another half remembers Richard Cockett’s description of how libertarian think-tanks helped - over very many years - to shift the Overton window; within my lifetime, private ownership of utilities, for example, has gone from being unthinkable by the political class to taken for granted.

There is, then, a question here of the roles of reason, power and client groups in achieving genuine political change. This question gets overlooked amidst the tribalism of day-to-day debate and a managerialism which worries about focus groups and day-to-day polling. And for me, this is a pity.

April 11, 2012

Baldynomics

Raedwald alerts us to one of the great under-reported scandals of our age - the stigmatization of bald men. This poses the question: how serious an economic problem is this?

One the one hand, baldness is a disadvantage in politics; a slaphead has little chance of becoming PM or President in the UK or US, though Russians are more enlightened. And bald men are slightly under-represented among American CEOs.

On the other hand, though, the only study I know of a link between baldness and earnings - from Brazil (pdf) - found no statistically significant relationship between the two. It seems, then, that Raedwald is wrong to claim that baldness is a "disability." It is less injurious to earnings than being ugly or short (pdf) - two things which, I suspect, are uncorrelated with slapheadery.

I suspect this is because of an omitted variables problem. Baldness is associated with high testosterone, and this has ambiguous effects upon earnings.

The good news is that it is associated (pdf) with risk-tolerance, which can lead people into high-paying financial careers; baldness is very common in the City. It is also associated with status-seeking behaviour, which can encourage people to climb greasy poles; the common claim that testosterone promotes aggression is not as true as you might think.

On the other hand, though, there's some evidence that testosterone is associated with poorer social skills. And the status-seeking that can lead to high earnings also has a downside, as it can cause boys to follow their peers into acting lairy or taking drugs, thus jeopardising their intellectual attainment.

On balance, then, I don't think baldness is either a positive or negative for earnings - though I think the cliché that "more research is required" actually applies here. I cannot therefore agree with Raedwald that baldies need positive discrimination. But equally, nor is there a case for taxing us more heavily, as there is for tall men. Of course, we should celebrate being alopecially advantaged, but our superiority does not, generally speaking, yield a labour market advantage.

April 10, 2012

If productivity hadn't fallen

In the day job, I say that if productivity hadn't fallen since the end of 2007, there would now be three million fewer people in work. This is just a simple mathematical claim. But it raises the question: what would have happened if productivity had kept growing at its pre-2007 rate? Would we really now have almost six million unemployed, or would there have been some offsetting mechanism to create jobs?

One obvious possibility is that if productivity had kept growing, we would have seen more quantitative easing. This is because inflation would have been much lower, partly because firms' labour costs would have been lower as they sacked more workers, and partly because higher unemployment would have depressed consumer spending.

But it's unlikely that QE alone would have created so many jobs. The Bank estimates (pdf) that the first £200bn of QE raised GDP by 1.5-2%. This suggests that, to create three million jobs - a rise in employment of 12% - we'd have needed almost £1.4 trillion of QE. That would have required the Bank to have bought every gilt in existence, and then some. Which is a big ask*.

Another possibility is that fiscal policy would have been looser, which would have created jobs. But again, this is unlikely. Higher unemployment might well have raised the deficit relative to what it would otherwise have been, causing the government to (wrongly) fear it was too big.

It's unlikely, therefore, that policy responses to higher unemployment would have been sufficient. But are there any endogenous responses to higher productivity and unemployment that would have tended to create jobs?

You might think that the very fact that workers are more productive in this alternative universe would cause firms to hire more of them. But things aren't so simple. Firms only hire if they anticipate sufficient demand for the additional output. And where would this demand come from? The tendency for higher unemploymentwould depress consumer spending. On the other hand, it's likely that business investment would be higher - not least because a world of growing productivity is a world in which there are more investment opportunities and easier access to finance. But as business investment is only 8.3% of GDP, it's unlikely that it would be so much higher as to create three million jobs.

Another possibility is that the tendency towards higher unemployment would have depressed wages even more, and this would have encouraged job creation. I suspect, though, that this would have been only a small benefit given that the price-elasticity of demand for labour, for given aggregate demand, is quite low; we know this because the minimum wage did not destroy that many jobs.

Another possibility is that sterling would have fallen more than it did. But again, this is little help given the low price elasticity of demand for exports - we didn't get an export boom after sterling fell 20% in late 2008 - and their relatively low labour content.

My conclusion here is simple. It's very easy to imagine that, if productivity hadn't fallen, we would have much higher unemployment now.

Such a situation, though, would probably be even worse than the one we're in. Not only would we have the human misery of greater joblessness, but we'd also quite possibly have serious political unrest.

Which brings me to a paradox. There is no question that, in the long-run, higher productivity is a huge blessing; it's this, and pretty much this alone, that makes us rich. But in the short-run, it is not such a good thing. I'm not at all sure how to reconcile these.

* A larger obstacle is that it would have required nominal corporate borrowing costs to fall below zero.

April 9, 2012

Anti-meritocracy

What do the following have in common?: newspaper columnists paid six-figure sums to echo their readers' prejudices; bosses who are overconfident and/or psychopaths; reality TV show contestants; Jedward and Samantha Brick who profit from people laughing at them; and radio show hosts employed for their controversial views.

There are two common features here. One is that these are characteristic types of our media age. The other is that they are examples of anti-meritocracy. Such people are financially successful not despite a lack of merit, but because of a lack of it.

What we have is a latter-day Bedlam. The difference is that lunatics are not displayed for a penny a view, but instead have gone viral and have their own shows.

Of course, it has always been the case that some bluffers, chancers and arse-lickers have got lucky. What is new - or perhaps more prevalent now - is that a lack of merit can now be a positive asset; people are selected for their demerits. The counterpart to this is that ability can be a drawback. Competent singers earn much less than Jedward; Tim Harford probably earns less than Boris Johnson; and some decent radio presenters less than Galloway. And so on.

If this is the case, then the tension between meritocracy and a market economy is more acute than ever*. But does this matter?

In one sense, I don't think it does. As Michael Young famously argued, a meritocratic society would be hellish because both rich and poor would think they deserve their fates. In an anti-meritocratic society, the less successful at least keep their self-respect. And I'm not sure that - bosses apart - anti-meritocratic successes claim to deserve their fortune, and if they do nobody believes them.

In another sense, though, it does matter. If young people think that success is possible without merit, then they will under-invest not just in education but also perhaps in cultivating a quiet good character. If so, then anti-meritocracy might have long-run costs.

* Some right libertarians will object that the success of these people is evidence that they do have merit. However, if we equate merit with what sells, then we drain the word "merit" of its conventional meaning, and make a free market economy meritocratic by tautology. This is silly, and intelligent defenders of a market economy do not argue this way.

April 8, 2012

Skiffle, & intergenerational justice

Tim Harford is sceptical of the arguments for giving pensioners tax breaks. There is, however, an argument for them. It lies in skiffle music.

A distinctive element of skiffle was its use of home-made instruments such as the washboard and tea-chest bass; aficionados argued over the merits of Ceylon and Assam tea. There was a reason for this; in the 50s, conventional instruments were too expensive. For example, John Lennon's first guitar, bought in 1956, cost £5'10. That was almost two-thirds of a week's pay for a skilled manual worker; today, you could probably buy a better instrument for one-third of a week's pay.

Anyone wanting to listen to music faced a similar problem; records too were expensive. Until Woolworths started a price war, single records cost nine shillings in 1954 - a third of a day's pay. And that was if you could find them; fans of the American folk music which inspired skiffle had to schlep forlornly around expensive record shops. Today, we can download it easily for nowt.

Today's pensioners - yesterday's young people - faced much narrower horizons and opportunities because real wages and technological opportunities were both low. This is true even if their income today is relatively high. In this important sense, they have suffered disadvantages relative to today's youngsters through the unavoidable bad luck of being born early. You can interpret redistribution towards pensioners as compensation for these disadvantages - just as we support children born into poor families who suffer similar bad luck.

But is this a sufficient argument? There are two, separate, lines of thought which suggest not.

One is the standard libertarian claim that differences in luck are not sufficient justification for redistribution.

The more interesting arguments, though, are utilitarian ones. One of these says that the bad luck of living at a time of low wages and lack of technology did not make people unhappy. Nobody in the 50s or 60s cried themselves to sleep because they didn't have internet access.

The other lies in the marginal utility of income. It's possible (pdf) that older people have a lower marginal utility of income than younger ones - in the sense that if their income rises by a given amount, their happiness would rise by less. If this is the case, then taxing the young to give pensioners higher incomes decreases happiness.

My point here is not so much to take sides, as to suggest that, from an egalitarian point of view, there might be a case for generous support for pensioners, to compensate for a relative disadvantage.

April 6, 2012

"Natural" economic activity

Last night's Corrie highlighted a shortcoming in some neoliberal thinking.

Karl Price has got into big debt because,having lost a little, he kept going to the casino in the hope of "one big hit, one good night on the tables" - with inevitable results.

Karl's behaviour is, of course, familiar not only to anyone who knows a gambling addict but also to behavioural economists. Prospect theory tells us that people are often (pdf) risk-seeking where losses are concerned; in their attempts to break even, they take bets they would otherwise avoid. Strictly speaking, this is irrational; the attractiveness of a bet should depend upon its expected pay-off, not upon our financial situation.

There is a neurological basis for this irrationality.Camelia Kuhnen and Brian Knutson have found (pdf) that the brain responds differently to the prospects of gains and loss.The prospect of gains is associated with activity in the nucleus accumbens - part of the brain which processes pleasure - whilst the prospect of losses is associated with activity in the anterior insula, a region associated with feelings of disgust.

This means there's a conflict between economic theory and common sense on the one hand and the structure of our brains on the other. Theory says profit and loss are just mirror images of each other. Our brains behave otherwise.

This matters, because it casts doubt upon Adam Smith's claim that all humans have a "propensity to truck, barter and exchange."* If this were so, we'd expect our brains to be structured to facilitate if not optimization then at least the avoidance of the sort of horrible error that Mr Price made. But they seem not to be so.

On this point, behavioural economics and neuroscience is corroborated by anthropology. David Graeber says it is simply a myth that primitive men truck exchange and barter among themselves:

To this day, no one has been able to locate a part of the world where the ordinary mode of economic transaction between neighbours takes the form of "I'll give you twenty chickens for that cow.(Debt: The First 5000 Years,p29)

All this matters, I think, for two reasons.

One is that it suggests that a free market economy (and its correlate, property?) is not a "natural" phenomenon, but rather an artificial creation - one greatly aided by the state. Such an economy has much to commend it. But it is not in accord with human nature.

Secondly, the fact that there's a neurological basis for bad economic decisions means that we must not assume that a free market "naturally" leads to rational optimization. It doesn't.

* Smith was unsure whether this propensity was "one of those original principles of human nature" or "one of the necessary consequences of te faculties of reason and speech".

Chris Dillow's Blog

- Chris Dillow's profile

- 2 followers