Angela Slatter's Blog, page 83

May 27, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: The Story of Ink

Kathleen’s drawing from Bitterwood’s “Spells for Coming Forth by Daylight” – works well here too.

“The Story of Ink” follows on from “Ash” in that it traces the fate of the baby Blodwen gave away in the earlier story. Her life isn’t the wonderful dream the poor witch imaged for her, but she’s got a kind of freedom for a while at least. But this story isn’t told by her, it’s told by very young Livilla (who later appears as a grown-up in “Sister, Sister”). Like Blodwen, she’s working for a powerful man, a prince of the church, with an interest in matters less ecclesiastical and more arcane.

I like Livilla; she’s a study in the lies we tell ourselves in order to do things we’re not proud of, things that, ultimately, break our hearts forever no matter what we might later do to atone.

The Story of Ink

The girl is thin, flat-chested and badly dressed, but her hair is dark and glossy and her cheekbones high. Her skin is clear and glowing. The torn sleeve of her dress shows the tiny red flash on her shoulder I’ve been told to look for – get closer, he said and it will be a tiny red crown. She’s easy to recognise, all things considered. The old man’s daughter, a runaway.

He’s paying; I’ve got instructions; he says she’s his daughter, so she’s his daughter.

I watch a while longer, the better to know my quarry. She laughs and jokes with the stall-holders in the market and the other whores – these girls work the streets, they’ve not got the protection of one of the pleasure inns. This isn’t the fancy market at Busynothings Alley. It’s just as busy but nowhere near as clean, nor as reputable. This is Half-moon Lane, out in the slums, out where people live packed on top of one another, where the truly desperate find a home in the sewers and crypts. Some even live in the hollows at the base of the city walls.

Strictly speaking, it’s far too wide for a lane, more like an avenue or a boulevard but, well, there you go. In Half-moon Lane you can buy the usual bits of food and spice, pots and pans, but there are also potions and poisons to be had. If it’s an assassin you’re after then try any of the taverns that line the pavement, and if it’s love you’re in need of and don’t want to pay the over-heads of an inn-bred whore, then Half-moon Lane will fulfil your requirements. Girls just as pretty but cheaper, and with a shared room at the top of one of the perilous staircases that cling to the sides of the buildings. Just watch out for the pimps, that’s all.

How this pampered girl came to be here is a mystery. You can see she’s had a soft start in life, it shines through whatever’s happened to her on the streets. But almost everything else is as the old man said it would be. Almost. What I didn’t expect, what he didn’t tell me, probably didn’t know, is what she’s carrying: a baby, wrapped in ragged but clean blue cloth. A boy if tradition’s anything to go by, maybe a year old.

I rap my cane on the roof of the carriage and the driver knows to gee-up the horses and  pull us over to the other side of the lane, stopping just near the girl. Pennyworth gets down and opens the door, unravelling the fine metal steps so I can descend.

pull us over to the other side of the lane, stopping just near the girl. Pennyworth gets down and opens the door, unravelling the fine metal steps so I can descend.

Around me the noise stops and I’m pleased with the effect I have. My outfit is cut like a riding habit, although I’ve never been on a horse in my life. Blue velvet the same shade as my eyes, the short jacket is fitted and detailed with silver braid; the skirt is full and falls like water. Around my wrist is a pearl bracelet and on my right index finger, a silver ring, filigreed with a moonstone setting. I love the tricorn hat that perches on my dark red curls. The silver-topped cane I clutch in my right hand was a fine gift from my employer. (He said I should be protected and showed me how to slide the blade out from the bottom section.) The fact that I’m only eleven completes the strength of the impression I make.

I take small precise paces toward the girl, holding my skirts so they won’t drag in the mess and muss. She watches me, the corner of her mouth lifting in amusement. There’s nothing unkind in it, but it annoys me, that she doesn’t take me seriously. My outfit, my poise, my position were all hard won and here’s this street-whore laughing at me.

I taste the acid of resentment, but I paste a smile on my face. No point in showing her what I feel. You catch more flies with honey than vinegar, my old mum used to say, when she was sober enough to say anything.

‘What’s your name, lovely?’ I ask and her grin lifts into a full smile. She really is beautiful.

‘Jessamyn, but for a quarter-gold it can be whatever you like,’ she laughs to let me know she’s joking. She jiggles the baby on her hip and looks at me amiably. ‘You’re a little young for my services, darling.’

‘I make you a proposition on behalf of my master,’ I tell her, lifting my hands in a magnanimous gesture, the cane twirling in the fingers of one hand, then hopping across to the other. I’m still thinking, trying to figure out what to offer her, what will tip the odds in my favour.

‘Indeed? And what does he offer, this man who sends a child into the streets?’ Her face displays distaste now and I can’t help myself.

‘What I do I do willingly. Don’t be fooled by my size, missy. I choose to be here and I am no man’s whore,’ I hiss, showing more of myself than I would like. She recoils and looks ashamed, to have shown herself judging of me when she’s the one walking the streets, some stray get on her hip.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says and I can tell she is. ‘Let’s start again, shall we? I’m Jessamyn.’

I take a deep, calming breath and smile brightly. ‘And I’m Livilla. My master asks that you come to visit. Perhaps that you will stay, if you find his house and company agreeable.’

‘And how does your master know me?’ The baby’s fat little hands curl around her fingers and she gives him a distracted smile. How hard is her life with this one to keep? But she has not let him go like so many of them do. She did not get rid of him by drinking some witch’s brew. She keeps him close; that should tell me something about her.

‘He has driven by in his carriage.’ I gesture over my shoulder at the fine black conveyance with its silver trappings, but conspicuously lacking a coats-of-arms or any device that might mark it out. ‘He’s an important man, is my master, and it wouldn’t do for him to be seen approaching a woman on the street …’

‘So he sent you?’ she says and gives a laugh. The baby giggles, too, hearing her. He grabs a handful of her lush black hair and gently plays with it. I wonder what my master will do with this grandson of his. Farm him out? Send him to one of the orphanages? Keep him at home and hold him close? I cannot tell.

‘Just come and see. One visit. A good hot meal for the boy-bee. Nice bath for you. I’ll look after the little bloke. Nothing too strenuous, for my master is venerable.’

‘Isn’t venerable just a big word for old?’ she asks, all mirth.

I ignore her and go on, ‘Just one visit and if you like it then think about staying. Better to be in one of the fancy houses. Better to raise the boy in a safe place, to let him be educated by tutors, rather than thieves. What do you want him to grow up to be? Honest man with a good trade, or a pickpocket?’

Her eyes darken. The boy rubs his face against her neck like a puppy seeking a pat. She runs a hand over him as if to check that he’s not too thin, not too deprived. He’s a fat happy baby, but I don’t tell her that; don’t offer reassurance.

‘Alright,’ she says.

I smile, trying to simply look pleased and not triumphant, as if this is a happy result for both of us. As if this won’t bring me a longed-for reward. A little place of my own, one of the tiny townhouses that border the richer cantons, newly built for the newly respectable in the row that burnt down last year in a conveniently tidy way (a most controlled conflagration, it has been noted). A little house over four floors and no one to share it with, new-fangled plumbing and tiny a little garden out the front. All my own.

Pennyworth’s waited by the coach all this time, now he bows politely as I usher the ragamuffin in and follow her quickly. I flutter my lashes at him and he knows to lock the door after he rolls up the steps. The door on the other side of the coach has been long ago fused shut.

Inside we rest on velvet red seats, comfortably firm, but soft to touch. We both sit so as to face forward when the carriage moves. In the middle of the seatback is a panel and I slide it smoothly out. A small tray with a crystal decanter and two glasses sit in their own little case. Some freshly-made sweetmeats wait in a crystal dish suspended in a kind of silver cage. I know they’re laced with an opiate, so even though they make my mouth water I cannot have one. Although, perhaps, for later, when I need to sleep, I will take one.

I pour her a drink and she accepts it graciously, nodding to me over the rim of the glass. The baby tries to grab at it and she gently shushes him. He whimpers but settles. I break off a corner of a sweetmeat and push it into his mouth; it will calm him if nothing else. I offer her a fresh piece but she shakes her head.

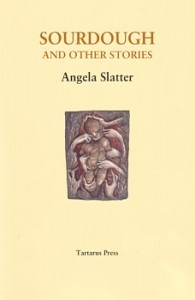

Stephen J. Clark’s cover art

‘I prefer apples. Lost my taste for sweetmeats after I gorged myself sick on them once,’ she says and I curse inwardly. The tokay isn’t drugged – the old man insisted she would take the sweetmeats, so he didn’t drug the alcohol, so I could drink it too and not raise suspicions if I insisted she drink alone.

She lifts one of the shades and looks out the window. She goes pale; she must recognise the way we’re going.

‘No,’ she says. ‘No!’

‘C’mon, love, I’m taking you home,’ I say, trying to sound sympathetic, but it doesn’t seem to help. Her eyes go wide and she’s panicking, but she still doesn’t hit me. That’s the advantage, I guess, of being a kid. She tries the door on her side and finds the handle useless, then pushes past me to get to my door, but it’s locked too.

‘You don’t understand. You don’t know what he’s like.’

‘Come now, calm down. He’s your dad and he just wants you to come home. Be a family, like.’ I twist the top of the ring and the little spike pops up. I grab for her arm and scratch the skin, carving a thin furrow that wells red. She yelps but it doesn’t take long for the poison to work. I have to grab the baby from her so she doesn’t drop him as she falls into a deep, drugged sleep.

***

Vale Tanith Lee

Last night I heard that Tanith Lee had died.

Last night I heard that Tanith Lee had died.

I was fortunate enough to meet her at WFC in Brighton in 2013 and to be on a panel with her; I was even more fortunate to have corresponded with her for some interviews for the Stephen Jones anthology Fearie Tales. I was quite nervous about meeting her – life has taught me that meeting your heroes is seldom a very good idea – but she was lovely. She was open and generous and supportive – not something one encounters every day in the writing world. She was flamboyant and divine and very, very clever. I had been reading her work since I was about fifteen, so it was a bit like getting to meet God.

I asked her if she wouldn’t mind doing another interview for the Lair of the Evil Drs Brain, and she was happy to oblige. I asked Kathleen Jennings to do a sketch, and said “You MUST draw her in the black feathered Servalan dress!” And Kathleen did – see, here? When I sent the link to Tanith, she was delighted and asked “Do you think the artist would mind if I printed the sketch off and stuck it over my desk?” I told her the artist and I would be utterly ecstatic if she did.

Quite apart from the astonishing range of her writing, her generosity to younger writers and her fans, and the trails she blazed for women writers that many of us tread a little more easily today, she was kind. And that is a rare gem of a thing, like the woman herself. I shall be re-reading Night’s Master this week, the first Tanith Lee book I ever read.

My heart still feels a little broken.

May 24, 2015

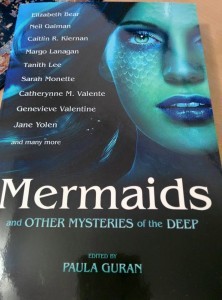

Mermaids in the Mail

So this just arrived, the very lovely Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep, edited by the delightful Paula Guran (Prime Books).

So this just arrived, the very lovely Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep, edited by the delightful Paula Guran (Prime Books).

Contains stories of awesome by the likes of Lisa L. Hannett, Margo Lanagan, Catherynne Valente, Tanith Lee, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Neil Gaiman, et al.

And I got a berth, too. Huzzah!

Available here.

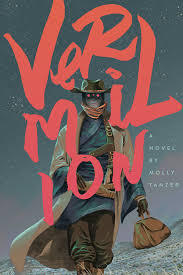

Molly Tanzer: Vermilion

The wonderful Molly Tanzer’s astonishing Vermilion is out and you should read it. Yes, you should.

The wonderful Molly Tanzer’s astonishing Vermilion is out and you should read it. Yes, you should.

Set is the Wild Weird West, Publishers Weekly described it as “…a splendid page-turner of a Weird West adventure … this hugely entertaining mixture of American steampunk and ghost story is a wonderful yarn with some of the best dialogue around.”

Here, Miz Molly talks about killer cocktails, Mr Vampire, and the parenthetical lessons of The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.

1. What do readers need to know about Molly Tanzer?

As my mother would say, “need is such a slippery word!” I’d certainly like readers to know that I’m a writer of short stories and novels, and that said fictions are available online and for purchase via various retailer and e-tailers—and that I think they will please anyone who like things such as historical fantasy, picaresque, Lovecraftiana (sometimes), gender-bending, genre-bending, and sexy times.

I’d also like them to know that I mix a killer cocktail.

2. What was the story/book that made you think ‘I want to write!’?

I have no idea! I remember getting really excited about learning about parentheses from The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe?

When I was a kid, my father read to me every evening he was home, and I think that—along with seeing him and my mother reading almost constantly—instilled in me a love of story more than any specific, individual text. That most of these books were fantasy novels—the aforementioned chronicles of Narina, Prydain, etc. I believe contributed to my desire to write speculative fiction!

3. From whence came the inspiration for Vermilion?

All over the place! Certainly the seed was planted by the 1985 kung fu horror comedy Mr. Vampire, when I saw that in grad school. Moving out to Colorado, and seeing the amazing landscape at my doorstep set the scene, and I’ve had a lifelong obsession with quack medicine and dubious curative treatments. Since the novel is definitely a salad bowl of pretty much everything I like, it’s hard to pin down one thing!

4. Who is your favourite fictional villain?

Oh man, that’s so tough! Thulsa Doom, from Conan the Barbarian, is always foremost in my mind when it comes to excellently-drawn villains, but a recent re-watch of Avatar: The Last Airbender reminded me of how wonderfully wretched Azula is. Hannibal Lecter is also a strong contender, as is Bayaz from The First Law trilogy.

5. Who is your favourite fictional hero/heroine?

That’s even tougher! Right now I’m digging Antimony from Gunnerkrigg Court, and also Thorn Bathu from Joe Abercrombie’s YA series. Finn from Adventure Time?

6. Who were/are your literary influences?

6. Who were/are your literary influences?

Roald Dahl I’d definitely say was almost a primordial influence for me, and H.P. Lovecraft needs to be on there as if I’m known at all, it’s mostly for my Lovecraftian fiction. Recently I’ve been reading a lot of Carrie Vaughn and trying like hell to learn something from it… the Kitty the Werewolf books are great, but I’m most impressed by her Golden Age series. The writing is so buoyant, and her ability to write about human problems is astonishing. I’d also point at Jeffrey Eugenides… Middlesex is probably my favorite novel, and it haunts me, knowing someone out there wrote something so perfect.

7. You are allowed to invite five people, dead or alive, to a dinner party – who are they and why?

Thomas Day: I’d like to ask him all about his Pygmalion scheme to mold the mind of a child into that of an ideal bride.

Jane Austen: The opportunity to talk to one of my favorite authors, and ask her about my weird theories about her work, is irresistible.

Laura Ingalls Wilder: I’ve loved her books since I was a wee Tanz, and I’d love to talk about the ways her daughter edited the Little House books, and not only that, but I’d love to ask how close her novels really were to her life…

Roald Dahl: The man loved food, and loved to talk—I think it would be fascinating to spend a few hours eating with him.

Cheng Pei-Pei: I’d love to talk Hong Kong cinema and martial arts with her.

8. When you’re in the mood to read, who is your first choice? Do you have a favourite you re-read?

I’m re-reading The Secret Garden right now, which I re-read almost every spring. It’s a problematic novel but a fascinating one, and my edition, which has illustrations by celebrated muralist Graham Rust, is a joy to read as the leaves start to green.

I’m not sure who my first choice is when I’m just in the mood to read… I tend to read more fantasy than anything else, which is odd as I write horror. I also always seem to have a stack of my wonderful friends’ wonderful books that I’m perpetually behind on, so that’s always helpful when it’s time to make a choice!

9. What’s your favourite short story ever and why?

Very possibly “The Beautiful Gelreesh” by Jeff Ford. It’s so lush and delicious and sad. It’s so perfect as it is, and yet I wish it was longer. Reading it now I wonder if Bryan Fuller didn’t read it when he was conceptualizing the new Hannibal show. The Gelreesh is definitely Mads Mikkelsen as Hannibal Lecter, dressed like the fop-werewolves from that one vignette in The Company of Wolves, by way of the Comte de St. Germain. So yeah, everything I like?

10. What’s next for Molly Tanzer?

10. What’s next for Molly Tanzer?

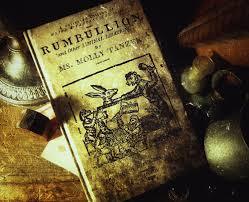

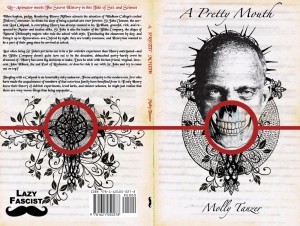

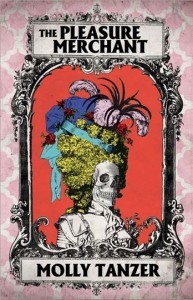

My next novel, The Pleasure Merchant, is out this November from Lazy Fascist Press. It’s the story of the ambitions of a young wigmaker’s apprentice turned personal servant, so definitely in my usual picaresque mode, but I confess there’s next to no speculative element. It’s very loosely based on Thomas Day, who I alluded to above, and his quest to train a wife. But since no novel could ever be as good as Wendy Moore’s nonfiction book about it, How To Create The Perfect Wife, I just allude to the story.

May 21, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: Ash

“Traitors-Gate” by Fluous – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fil...

The tale of Ash came from a couple of sources: I was reading a book by Alision Weir, Isabella: She-Wolf of France, in which Weir talks about a fire in one of the royal palaces that left the Queen (or Dowager Queen as she was then) burned and scarred. The historical record of this is basically an old copy of a doctor’s bill. Around the same time I was looking at pictures of the Tower of London, and the Traitors’ Gate in particular, and I had an image of a woman wrapped tightly in a cloak, sitting in a boat, floating in under such a water gate.

My characters turned up in timely fashion: Blodwen, who traded a child for eldritch knowledge and in the process lost everything; and Gwenllian, who traded her own freedom for a life of luxury, and her own child for a restoration of her beauty. This story links to “The Navigator” as Gwenllian is the woman loved by Windeyer, the woman he chased after when she agreed to go away with the Archbishop. The eagle-eyed reader will note the mention of Bitsy at the end, who appears in two more Sourdough tales later on.

This is a short short story, so I’ve posted it in full.

Ash

The water flowing beside this small, remote castle runs as cold as a serpent’s blood. The mist curls up from the surface of the river, reaching into my lungs, and drawing out deep, damp coughs. I shiver, a tremor that goes through every part of me. The autumn night gives a hint of what winter will bring. I pull the shabby fabric of my old cloak close around me.

The first time I came here I had nothing to fear, no crimes to regret, no sins to repent. I was an invited guest, honoured and, most of all, needed. But even a short span has wrought changes I could not foresee.

Eyes no longer linger on me; they slide away. Scars mar my skin, pulling tight like unevenly placed stitches. They itch and ache, remind me constantly of their presence.

Three years ago, I was still young. Three years ago, I had a face that made men pause. The last time I floated in under this stone arch, the boat rocking as we moored, the man-at-arms with brown hair and worried eyes stared a long time at the pale moon of my face, troubled by what his mistress might want with the likes of me. Then he wrapped me tightly against prying gazes and tugged the hood of the fine grey cloak I then wore far down over my features so no one would see me and later know me.

That day led to this one. I go before the same woman, by the same secret ways, under the same witch’s moon. I do not think I will walk out alive. My bones will sleep under dirt and stones somewhere within these stout walls. No one will look for me; no one will care. Some bargains, once made, should not be revisited.

Stairs are hard for me. My bones were never properly set. I ache. I might forget, sometimes, that my hair has faded, and my face is other than it was – that no man will share my bed willingly – but the pain reminds me. It is merciless. I tell myself I do not care about the loss; that it makes no mind to me, what is there and what is not. When I am alone, I can oft-times believe it. No one has been there to gainsay my lies. Until now.

The room has not changed, really – a little richer, more luxurious. Her lover, Archbishop Bigod, is generous, perhaps to make up for his long absences. He does not often leave his cathedral city and she is left to while away her time far from him. I wonder how her days pass; a loom waits silently in a corner and the walls are hung with tapestries. Perhaps my question is answered thus. How many days, how many wall hangings to measure a life? How much time in front of the tall silver mirror, watching her features change, her beauty slowly lessen?

Gwenllian occupies a comfortable chair near a wide window, and the moonlight angles in upon her. She, too, has aged, though less dramatically than I. She is older than me but looks younger. Her existence has been cushioned by wealth. There are lines on her face but her make-up cunningly disguises them. There are no flecks of silver in her dark hair. The sleeves of her dress are slashed (not so fashionably, but I know why she wears them thus) and I can see the skin there. Her face, neck and forearms are pink, youthful, expensively bought. My best work.

She surveys the cross-hatching of my face, the uneven line of my shoulders. Does she wonder why I have not healed myself? Does she think I could not? That I have lost my gift?

‘It has been a long time, Blodwen.’ The voice lilts, a flower on the breeze. I merely nod.  This is less courteous than she is used to and it makes her frown. Here in her castle, with her servants, she is queen and law. Perhaps her isolation has made her think herself God as well. ‘You have been ill?’

This is less courteous than she is used to and it makes her frown. Here in her castle, with her servants, she is queen and law. Perhaps her isolation has made her think herself God as well. ‘You have been ill?’

‘My lady is observant.’ My voice, previously sweet, is no longer so. There was a time when I could bewitch with my tone alone. Now I sound like a crow in human form.

‘Your tongue is still sharp.’

‘It’s all I have left.’

We stare at each other for a moment, the Lady Gwenllian and I. There are no attendants – just like before. No witnesses to our bargain. Her eyes drop to stare at her arms, then she raises her hands to touch her cheeks and the smooth curve of her throat. When last I came here, they were still weeping from the burns she’d suffered, the flesh red and raw like a side of half-burnt beef, and the stench septic.

The Archbishop was here three years ago, just before Gwenllian’s accident. He has sent word that a tour of the surrounding countryside and the abbeys and convents nearby will bring him this way. He wishes to see their daughter, who should be six. This much I have from my surly escorts, the men who sought me out in the cesspit of a village where I have lived these last broken years. This much and no more.

‘Your face …’ she begins.

‘I was dragged behind a wagon. My legs were broken, too. Not everyone is kind to my sort.’ I sit, without invitation, on a chair opposite her. She says nothing; she knows that this little comfort is the very least she owes me. There is the low sound of my joints cracking as I bend.

‘You did not …’ she gestures, once again not finishing her question. ‘You could not?’

I am silent, thinking of the pain of those days and months. Of the strange weight of loss – how is it that in having something taken away from us, we suddenly feel heavier? Now there is merely the lightness of ceasing to care.

‘What I do carries a price – I would not pay it,’ I say. ‘I am not you. My blood is still warmed by conscience.’

Guilt shimmers across her face then dissolves in a cloud of rage. She starts violently from her seat, looms over me, but I am a tired woman. Anything she does to me will be a lifting, a relief. I think she sees in my face that I will welcome any end.

With an effort she speaks quietly. ‘What you did for me,’ she lifts her arms (as if I do not know her skin as well as my own). ‘What you did for me was a miracle and I judged the price fair.’

‘But?’

‘But I need what I gave you. I need her back.’

I laugh so loudly it hurts my ears; the stretching of my mouth makes my jaw ache. My stomach convulses with bitter mirth. It takes me a long time to calm myself and by then her fury is palpable, uncontained. This is why she had me found, hunted like a fox and brought here. I have not strictly hidden, but I have not lived in plain sight.

‘I want the child. I need the child,’ she hisses.

The daughter she gave me as the price of her healing. Three years ago she was eager to sacrifice the little girl if only she herself could be smooth and whole and pink again.

‘I no longer have her,’ I say. ‘She is not mine to return.’

‘Her father comes and he will wish to see her.’

‘Tell him what you did.’

‘I cannot!’

‘Show him another,’ I say.

‘No other has her birthmark,’ she spits the words out. I remember the small red crown on the child’s shoulder. Her father saw her when she was born; he will know if his mistress tries to substitute another.

‘Tell him she died – he will forgive that.’

‘He will not! She was my price.’ She gestures around us, to the room, to the comfort of her surroundings. ‘He warned me to keep her safe.’

‘You should have thought of that when you were giving her to me.’

Her fingers are at my throat, strong and warm and tight.

‘Where is she? Tell me and I will send my men to collect her. I will keep you in my household for the rest of your life. You will be safe and warm.’ Her soft words belie her hard hands. If I had a child I would not give it to this woman.

‘I will not tell you.’

She presses against my windpipe. The edge of my vision blackens. She lets go, quickly. That would be too easy a release for me, and she still has hope she can pry information from me.

‘You would not have given her away. The child was the price you asked. Life is too important to you – or you would not have been able to do this.’ She throws back at me every lie I once told her as she points at her face, her neck as triumphant proof. She does not know me as well as she would like to think.

‘I will not tell.’

She snarls, and her teeth are sharp and yellow.

‘If you do not give me the child, you will burn. You’re a witch, it’s only fitting. You have until daylight.’

She sweeps from the room and the door is bolted behind her. I lean back against the soft padding of the chair and try to swallow the ache. I think of the little girl, fat and laughing, those chubby arms and the sweet smell of warm child. And gone so quickly.

In truth, I do not tell the mother what happened to her daughter, for I do not wish her to know how alike we are, Gwenllian and I. How my contempt for Gwenllian is so firmly rooted in my contempt for myself.

The child I demanded for my services I paid to another in turn. I made a deal with an old man who taught me every scrap of magic I knew. I lived in his house for two years learning everything I could, but I did not warm his bed. When first I asked him to teach me, he refused my offer of the usual favours; told me he would have his recompense but that he would name it later. Would I be prepared to not know what it would be?

Blinded by the desire for knowledge, I said yes.

When at last he said it was time for me to clear my account and sent me to Gwenllian’s lonely bower, who was I to argue? He told me what to ask for as payment. I returned to the cathedral city, in love with my own power, floating on the cloud that healing Gwenllian brought, feeling as if nothing was beyond me. The child was on my hip and my heart felt full. I wondered why he did not go to take the child himself, but who was I to question his long game? Who was I to gainsay such a powerful man?

She’d be a princess, I told myself. She’d have the best life. I handed her over with barely a qualm. And I woke the next day to find myself sleeping in the street and the house not merely empty, not merely stripped of all the familiar things I’d come to expect, but simply gone. The place I’d called home all gone in the night.

It was a big city, but I could have found them. I could have sought him out and asked Why? He’d gone to such trouble, though, to hide – it would be stupid to make him angry by following him. I did not think myself stupid. The child was not mine. She would have a good life, little Jessamyn. The best I could do was to leave her there. I was not her mother, after all.

But I know, too, that when I gave the child away, all my luck turned bad.

Now I would not ruin her life by telling her dam where to find her.

*

The first ray of light brings Gwenllian back to my prison. She sees my expression and does not ask again. My answer is plain, even among the scars. Denied what she wants, she will destroy me instead.

Out in the courtyard a pyre is waiting. They tie me to the stake and throw pitch over me and the wood, so we will burn faster. I think of the girl, how Jessamyn cannot be worse off. How even death would be preferable to life with this woman who gave birth to her with no more thought than an apple tree puts forth fruit.

A small crowd of servants have gathered. There is a little girl with the whitest of hair and dreaming blue eyes. She holds a doll that’s almost as big as she is. We smile at each other, but a woman, who might be her mother, hurries her away. ‘Bitsy, don’t look, her kind will curse you.’

The Lady Gwenllian does not come down, but I know she watches from the high tower. As the smoke reaches my lungs, I cough, this time a dry hack that gasps for air. I feel the flames nip at my toes, catch my dress, and I tell myself that I am being warmed by an inn fire. I can almost believe it until the pain licks through me. My last comfort comes with Gwenllian’s screams.

My magic lives only as long as I do. In that high room, her arms and neck and lovely face are prickling and peeling and burning, a smell of pork filling the air. When I am gone she will not forget me, nor her broken bargain.

***

May 20, 2015

SF Travel Fund: Send Haralambi Markov away!

To WFC in Saratoga Springs, NY.

To WFC in Saratoga Springs, NY.

Harry is not only a great reviewer, an informed critic, and an engaged and intelligent fan, he’s also a writer of considerable talent and vision.

So, if you’ve got a few spare dollars, throw them in the very specific direction of this initiative.

May 19, 2015

Over at Tor.com: St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls

Art by Kathleen Jennings

The lovely folk at Tor.com have reprinted my Aurealis Award winning fantasy story “St Dymphna’s School for Poison Girls” in its entirety. And with all of Kathleen’s lovely illustrations.

“St Dymphna’s” first appeared in the Review of Australian Fiction (Volume 9, Issue 3) and also forms part of The Bitterwood Bible and Other Recountings from Tartarus Press.

Read here!

May 13, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: The Angel Wood

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fil...

This story first appeared in the lovely Shimmer #5 in 2006 (and illustrated by a wondrous piece by Sandro Castelli). The title came from a late night episode of Frost, I think, in which there was indeed a place called the Angel Wood. I liked the idea of mixing something religious with something deeply pagan, as though the wrapping of the name would lull you into a false sense of security, then when you opened it you’d find a Green Man inside, staring back at you.

“The Angel Wood” began with the idea of people fleeing; the reason for their flight wasn’t important (although it was a plague in a big city), but where they washed up was. The critical thing was the crisis that began the short story and then the consequences of choices made in both the past and the present. I can’t tell you why, but I knew they were in a carriage, they were dressed in clothing that owed a lot of the period of Charles I of England. I knew there was a mother driven to save her children, so desperate that she took them back to the home she’d fled years earlier. So desperate that she’d finally face the things she’d done by her own desertion of her mother and uncles.

I had the main character in my head, the oldest child, Henrietta, called Henri. I knew her voice and her point of view; she was an excellent vessel for new experiences. She’s a girl who’s on the cusp of womanhood and also, suddenly, an entirely new life, but a life that is also old and inherited. She has the chance to rebuild her family, the Woodvilles, and reinvigorate the forest – and to save her mother’s life, even though that will drive a wedge between them.

Again, it was a story that was written before the Sourdough collection, but which I knew had a place in it – I used Tildy, one of the twins, in a later tale, “Lavender and Lychgates”.

The Angel Wood

We wake only when a sudden stop almost jerks us from the seat. Now, with the plague-ridden city just a memory, the air is so sweet it creeps up our nostrils and makes us sneeze at its strangeness.

Jeremy-Charles lies quiet in my arms while Milly and Tildy snuggle, one either side of me. Outside, Mother’s voice is tense as she says she carries only victims from the city. A man answers that she lies – who would bother to transport the dying so far from Breakwater? I bid my siblings be silent, and peek through the gap between the door frame and the curtains that cover the windows.

Two men sit astride fairly fine horses – surely stolen – their faces wrapped in scarves, and pistols casually aimed at my mother. I don’t think they’ve realized that she is a woman, tall as she is, dressed in Father’s clothes, her voice deep. Her red mane is caught up under a hat.

One of them ambles his mount toward the carriage. I slide one of the pistols from under my cloak and hold it in both hands, trying to steady it. When the door opens, the highwayman’s eyes widen in the moment before I fire and his face turns to red. A second shot, then a third, rings out and I fall from the conveyance. Behind me, the children scream.

The other man lies on the ground, victim to the pistol Mother carries. The third shot seems to have gone astray.

My siblings continue to howl until Mother yells at them to be quiet. As she has never raised her voice to any of us before, the shock has the desired effect.

‘Tie their horses to the back of the carriage, Henrietta. Hurry up about it.’

I do as bid with shaking hands. As I move to climb back in, my stomach heaves. The grass is soft when I fall and vomit as if my innards are trying to leave my body. Mother’s palms are cool on my forehead as she holds my hair back and strokes my face.

‘Is Henri sick, Mama?” Tildy’s voice trembles. Mother shakes her head, blue eyes warm and pitying.

‘No, Henri is not ill. She’s just upset. Get back in the carriage, Tildy.’ She helps me up, lowering her voice. ‘First things are always hardest, Henri. It will be easier next time.’

She bundles me in and shuts the door, hard. We rock under her weight as she climbs back into place. The horses start forward and I go back to sleep, curled around Jeremy-Charles, my sisters watching me cautiously from the opposite seat. My dreams are disturbed, patterned with shades of red.

*

The house in the Angel Wood seems to stretch forever back into the trees.

It had been an abandoned castle when my mother’s family first came here, but succeeding generations added to it without much thought for aesthetics. It is now a hybrid thing, with a tower of buttery grey stone, a white and brown E-shaped house sitting around it, and a variety of outbuildings that really belonged nowhere else. The outer walls are now tumbledown. The ancient green forest, Mother said, simply kept encroaching – whenever it was cleared away, it grew back as if nothing had happened, as if human will and action counted for naught.

Like puppies shut away for too long, we children tumble out into the late afternoon. My feet touch the earth and the ground seems to hum in welcome, a tremor passing through me. My blood dances in response, washing away the red of my dreams and any lingering distress. I belong here – I don’t know how I know this, but it comes to me with an undeniable certainty. This is my home and I will be welcome.

Jeremy-Charles takes faltering steps when I set him on his feet and the twins run almost to the entrance of the house. Mother swings down wearily from her perch, pulling hat from head, hair hanging stiff with a paste of sweat and road dust.

The door opens and what looks to be the oldest woman in the world hobbles out. She does not seem a witch, does not look malicious, merely older than anyone I have ever seen. Her skin is tanned and her hair such a white that it shines like mother-of-pearl. She is quite tall, not at all stooped, and she gives Mother a weary look.

‘Are you home, then? With all these?’ She jerks her chin toward us, her eyes catching the sun and flashing amber. I wonder who she is to speak to my mother so; none of our servants would ever have even considered a word out of place. ‘Where’s their father?’

I notice that she does not say your husband. Mother stoops to collect Jeremy-Charles, gasping as she straightens; I fear she is very tired. She faces the old woman, somewhat subdued.

‘Dead of the plague.’

‘And you thought to bring the contagion here?’ But she does not seem in the least bit fearful. I think she is afraid of nothing.

‘We are none of us sick, Agnes. I would not have come here otherwise, but I needed to get the children away. Where are my uncles?’ She looks beyond her adversary, as if expecting further welcomers.

‘Fenelon, George, and James are all dead. Old age, you see, and we’ve no young blood to continue on. We are much reduced, Susannah.’ She looks at us for a long moment, sighs and steps aside. ‘Come along. There’s plenty of room for you all.’

I am surprised by the amount of light inside; there are many windows, an expensive luxury at odds with the apparent shabbiness. Through the glass I can see the Wood; things flit from trunk to trunk in the shadows. Birds? Squirrels? I wonder if the house in the Angel Wood was like this when my mother left it or if it suffered for her leaving.

‘Do your offspring have names, Susannah?’

‘This is Henrietta-Henri. These are Millicent and Mathilda. The boy is Jeremy-Charles.’

‘How old are you, Henri?’ She addresses me directly.

‘Sixteen, madam.’ She is probably not a servant-or if she is, she is one of that strange breed who have no care for place or manners, and get away with it.

‘I’ll see to the horses,’ Susannah says-so much more Susannah than Mother now.

‘I will see to the children,’ Agnes answers, as if we, too, are animals to be fed and watered.

I take my brother from Susannah and she slips from the room. Jeremy-Charles insists on going to the old woman’s arms and I let him rather than risk screams. We tramp along to a large kitchen where fresh bread and yellow cheese are put out for us. We eat in silence until my curiosity gets the better of me.

‘Who are you?’

‘Agnes Woodville. I’m your grandmother.’ She pours milk for the girls and they happily slurp as if they’ve been ill-bred. ‘Your mother hasn’t told you about me?’

I shake my head. ‘I did not know she had any family until Father died and she said we would come here. She has never mentioned you before.’

‘No, I don’t suppose she would.’ Jeremy-Charles snuggles close to her as she feeds him bits of cheese. ‘She ran away from us. Married your father instead of staying here to do her duty by her family. She-’

‘Enough, Mother. Enough poison in my daughter’s ear.’ Mother stands in the doorway, pale and shaking.

‘When is truth poison, Susannah?’ Agnes asks. ‘If you stay they will know soon enough.’

‘For now, leave them be.’ Mother strokes my hair, red like hers. ‘Eat up, then we’ll find some bedrooms.’

Susannah sways, weary, and strangely bloodless. When she falls, her cloak opens to show a bright red stain on her white shirt.

*

I help carry Mother upstairs. She lies, pale as her pillows, while Agnes washes the wound. When my grandmother remembers I am still there, she sends me out. I am to find rooms for us, any that do not seem too full of dust, and put the children to bed. We will speak later.

I find an old nursery, with a huge bed and a cradle intricately carved and dark with age. Tildy and Milly think their new bed is a boat for sailing on the seas of sleep. I do not contradict them and bundle Jeremy-Charles into the crib where, presumably, generations of my mother’s family dreamt their earliest dreams.

Across the hall I chose a room with a four-poster hung about with green drapes and curtains. I am irrationally pleased to have a bedchamber to myself. In the city, I shared with the twins and, much though I love my little sisters, I am thoroughly sick of them stealing my ribbons, playing with my dresses, and leaving my books in a mess. The sturdy lock on the door brings a smile to my face as I turn the key, even though at this point I have no treasures to hide.

***

May 12, 2015

In the mail: Blood Sisters

I love getting books in the mail. Especially ones I’m in.

I love getting books in the mail. Especially ones I’m in.

May 11, 2015

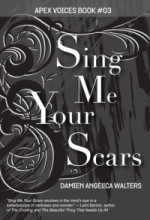

On Short Fiction by Damien Angelica Walters

Over at Layers of Thought, the very talented Damien Angelica Walters talks about one of my favourite topics: short fiction.

Over at Layers of Thought, the very talented Damien Angelica Walters talks about one of my favourite topics: short fiction.

I keep reading that short fiction is making a comeback. To that I say, did it ever go away? Looking at the books on my bookcases, I say no, but in the public eye, perhaps it did. I know I see more single-author collections on bookstore shelves now than I have in the past, and while many of the collections are by those already established, some are by debut authors. I think it’s a great time to be a fan of short fiction.

There are so many talented authors working in the field of dark fantasy and horror, and Shirley Jackson Award nominee Livia Llewelyn is one of my favorites. She writes horror, dark fantasy, and erotica and her collection, Engines of Desire: Tales of Love & Other Horrors, contains ten stories as beautiful as they are brutal. In many ways, her prose reminds me of Tori Amos’ lyrics—poetic and gorgeous with a razor-sharp edge that will cut you so carefully you won’t even notice until after you’re bleeding. Livia doesn’t pull any punches with her fiction and she goes into dark places many writers would hesitate to go.

One of my favorite passages from “Omphalos” references events between a mother and  daughter and isn’t necessarily disturbing on its own, but it holds an undercurrent of calculated cruelty which says much of the relationship of the characters.

“Long ago, like when she’d hide drawings you’d made and replace them with white paper, only to slide them out of nowhere at the last minute, when you’d worked yourself into an ecstatic frenzy of conspiracies about intervening angels or gods erasing what you’d drawn. You’d forgotten about that part of her. You’d forgotten about that part of yourself.”

daughter and isn’t necessarily disturbing on its own, but it holds an undercurrent of calculated cruelty which says much of the relationship of the characters.

“Long ago, like when she’d hide drawings you’d made and replace them with white paper, only to slide them out of nowhere at the last minute, when you’d worked yourself into an ecstatic frenzy of conspiracies about intervening angels or gods erasing what you’d drawn. You’d forgotten about that part of her. You’d forgotten about that part of yourself.”

Go here for the rest.