Angela Slatter's Blog, page 79

August 3, 2015

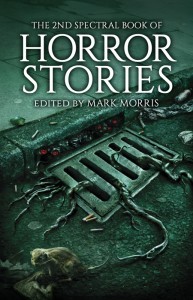

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Paul Finch

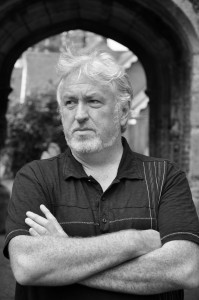

Paul Finch is a former cop and journalist, and, having read History at Goldsmiths College, London, a qualified historian, though he currently earns his living as a full-time writer.

Paul Finch is a former cop and journalist, and, having read History at Goldsmiths College, London, a qualified historian, though he currently earns his living as a full-time writer.

He cut his literary teeth penning episodes of the British TV crime drama, The Bill, and has written extensively in the field of children’s animation. However, he is probably best known for his work in thrillers, dark fantasy and horror, in which capacity he is a two-time winner of the British Fantasy Award and a one-time winner of the International Horror Guild Award.

He is responsible for numerous short stories and novellas, but also for two horror movies (a third of his, War Wolf, is in pre-production), for several full-cast Dr Who audio dramas, and a series of best-selling crime novels from Avon Books at HarperCollins, featuring the British police detective, Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg.

Paul lives in Lancashire, UK, with his wife Cathy and his children, Eleanor and Harry. His website can be found at http://paulfinch-writer.blogspot.co.uk/, and he can be followed on Twitter as @paulfinchauthor.

What inspired your story “House of the Hag”?

My love of native British folklore and mythology. Cathy and I travel as often as we can, usually trying to get into those oddball out-of-the-way places, and on one such trip to the Scottish Highlands – many years ago now, though the memory stuck – I was fascinated to learn about a series of neolithic stone monuments in a high, lonely glen, which were at the centre of all kinds of mysterious rumours. Okay, enigmatic standing stones, henges, barrows and the like are common throughout Britain, and it wouldn’t be the first time someone had written a spooky story about them, but the myths themselves are many and varied, and the particular idea I was struck with on this occasion was something I’d never encountered before, so I thought ‘what the hell’ and wrote it.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

One of the earliest I remember was “The Inn” by Guy Preston, which I first discovered in The 2nd Pan Book of Horror Stories. It’s not by any means the best horror story ever written, nor is it the most original – but I was very young at the time, and recall being utterly terrified, sitting up alone in bed and unable to turn the pages fast enough. That’s got to be the main ambition of a horror story, I suppose, in respect of which The Inn succeeded admirably with me.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

That’s a really difficult question to answer, if not impossible. There are literally hundreds who all occupy similar positions of worthiness in my mind, though for all sorts of reasons. It’s probably easier if I just tell you which current authors are names I look out for whenever I take an anthology down from a shelf and consider buying it. There are still plenty of those, but the three that most readily spring to mind are: Reggie Oliver, Adam Nevill and Steve Duffy.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

It’s ranged widely over the years and hopefully will continue to. I’ve done sci-fi in Dr Who and high fantasy in my Arthurian novels for Abaddon Books, but I’m probably best known these days for hard-edged crime. My Heck novels at Avon are easily my best-selling titles, so that’s the field I’m firmly planted in at present. Horror is still one of my greatest loves of course, and that colours everything. Quite a few reviewers have referred to my Heck novels as police-horror.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

A wide assortment. I’m a big Peter James fan. Also in crime terms, I’m getting into Craig Robertson, Steve Mosby, Stav Sherez and Deon Meyer. In horror terms, I’m a bit old-school. I’ve always got at least one Adam Nevill to read, but I’m currently recquainting myself with a few classics – Barker and Aycliffe to name two, while Dan Simmons’s The Terror is the big fat one I’m planning to take on holiday with me.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

August 2, 2015

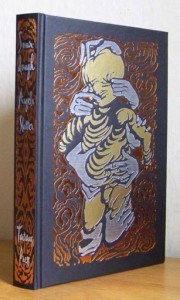

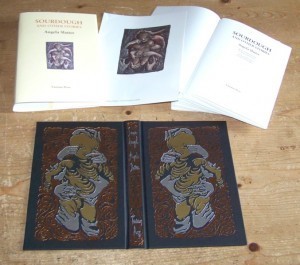

The Sourdough Posts: Under the Mountain

Image taken from page 78 of “Songs for Little People,” published in 1896. (The British Library)

The Sourdough Posts: Under the Mountain

Ah, and the last Sourdough post! “Under the Mountain” loops back to the events of “Sister, Sister” and some of the characters, but this time it focuses on Magdalene, Theodora’s daughter. When the inhabitants of the Golden Lily Inn and Brothel left Lodellan in the dead of night, to go and live on the country estate Theodora had purchased, Magdalene was still little. She had only brief memories of her father, Stellan, the prince of the city, and had been rescued by her mother from the troll-wife who’d been posing as Polly, Theodora’s lost sister.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the mother and daughter, and how their lives might be after that night, and after Theodora’s desperate race through the streets to save her stolen child. I thought that knowing that her sister, her true sister, had been stolen away also might trouble her, especially given how much bitterness and resentment had been sown in that relationship by the false Polly. I thought it would turn into guilt and eat away at Theodora. Perhaps she wouldn’t have gone off looking for her sister if things with Magdalene hadn’t become so fraught.

And I thought about Magdalene, a teenager and growing more angry and unpleasant by the day, though unable to really control herself as she wasn’t who she’d been brought up to believe she was. She was fighting against a nature she didn’t know she was heir to … yet she still loved Theodora fiercely, still had that attachment to her mother that sent her out into the world to follow her and bring her home. Of course, things seldom go as planned.

Under the Mountain [extract]

The sight of the inn picks at the stitches of my memory. The splintered shingle, emblazoned with a faded golden lily, swings in the breeze. I stare at it for a while, trying to catch at the recollection, mentally trying to scratch an itch I can’t quite locate. I push the aged door and it swings to easily. The place seems deserted, but in a corner, wedged in the angle of a padded bench beneath a hissing gaslight, is a man, pieces of parchment gathered in front of him. His hair was black and he was handsome, once. Now the hair is shot with iron-grey and he’s crumpled, body, face, and (I suspect) soul. His bearing speaks of loss.

‘Faideau?’ I ask.

He blinks, and I realise I am nothing more than a silhouette against the light. I close the door so he may see me clearly: tall and strong, long blonde locks, high cheekbones, ice-blue eyes. No sign of the unwellness, of the ache in my bones that does not come from hard riding. I find the shadowy space a relief.

‘Who wants to know?’ He is not drunk, but he is aggressive. His eyes are dark.

I did not need to come here. I had no requirement to speak to anyone but those who would have sold me fresh provisions and stabled my horse for the night. I know where I’m going, having studied Theodora’s books and the notes she left behind. I did not need to visit this place. I don’t really know why I came. I do not remember him, but this is the man Theodora mentioned with a sad amusement, a pang for what might have been. This was the one who did not take advantage of her favours after her fall from grace. When she changed from princess to whore and embraced her new calling as much to embarrass my father as to soothe her own pain, this was the one man she did not hold in utter contempt. Thus, she told me later, she did not sleep with him.

‘I’m Magdalene.’ I see him all uncomprehending. ‘Theodora’s daughter.’

‘Theodora.’ In his voice is such love and ache for my mother that I am embarrassed for him, to see his heart so naked. ‘How is she?’

How to say, to tell anyone how she was? How her night terrors had been getting worse. How thirteen years of them had made her gaunt and thin, drawn shadows under her eyes and washed their pale blue to the grey of a sickly sky. How long streaks of silver-white had threaded through her hair. How Theodora, whose beauty once made kings and clergy weak, had begun to fade.

‘Gone. She’s gone,’ I say and he misunderstands and I think the heart will flop out of his chest. ‘No, no! She is alive, but she is gone. She—left me.’

‘You? Left you?’ And I know he is thinking back to that night when Theodora ran through the streets of Lodellan and saved me from the thing posing as her sister. And he asks himself what I have asked myself: how could Theodora leave me?

‘She slipped away in the night, left me a letter. Went to search for Polly, her true sister. She said even if all she finds are the bones, it will help.’

He slumps even further down as if the mention of Polly adds weight to him. When he raises his eyes to meet mine I see secrets there, pushing their way to the surface. But I don’t want them.

‘Do you remember? Any of it? The time when childer went missing?’ he asks, peering at me. I take a seat opposite as he continues, ‘You don’t look like her, you know. Not at all.’

I shake my head. ‘I do not remember.’

But sometimes I dream of a pretty blonde woman. She grows and changes. Her voice remains honeyed even as she turns into something that will eat me; something that is all appetite. I fear my mother had similar dreams, for she would wake clutching at me, feeling to make sure my flesh was my own. That it did not shift and change into something other. He wipes a hand across his face and I see the map tattooed there. Curiosity shimmers.

‘What’s that?’

‘A reminder,’ he sighs and looks at the marks on the back of his hand as if they are foreign to him. ‘How are the others? Grammy, Kitty?’

‘Kitty and Livilla and their children left a few years ago.’ I do not tell him why. I do not tell him how they feared for their off-spring in the face of my tempers; how their last words to Theodora were bitter. ‘Fra died last spring. Grammy and Fenric are there, old but well enough. Rilka we see sometimes—she comes and goes according to her own counsel.’

He looks sad to know these things. ‘Have you gone to see your father?’

‘No, why would I?’

‘Why would you come here?’

I hesitate. ‘I don’t know. I had to stop somewhere.’ I cannot tell him about our fights, Theodora’s and mine; about the rage, about my guilt, about my last words to her, but I think he may guess. ‘I just stopped here for one night, for supplies. I remembered the inn, or at least I seemed to.’

‘You should stay then. Plenty of beds.’ He grins without humour. ‘Take your pick.’

*

The blue room has a view out over the Lilyhead fountain, but I don’t look down. Instead I stare straight ahead and concentrate on the sculptured lineaments of the palace. I have no memory of living there; I recall my father following us when we left that funny little man’s house on the night we fled Lodellan. I remember his blonde hair, and his lovely green eyes shining with tears in the lamplight. I remember how disgusted Theodora’s expression was when she gazed upon him. The sun is setting, all red-gold and raw, burning the sky as it plummets. Below I can hear the clank of pots in the kitchen like a call to arms.

*

Faideau has a disreputable apron tied around him, the lacy frills hang torn and frayed. I see no sign of the drunkard of whom Theodora spoke so sadly and fondly. His hands are steady on the knife and his movements, though slow, are assured. He sees me in the doorway and smiles. I wonder what Theodora would have said had she seen him like this.

‘Did you find everything you need?’

I nod. ‘Thank you.’ Wondering how much small talk there can be between we two.

‘Why did your mother leave you?’ he asks without preamble.

I lie. I lie because I don’t want to think about it. ‘I don’t know.’ He doesn’t believe me, begins to tell me his story, perhaps in the hope that one confidence will draw out another. ‘When I was a boy—’

‘I do not have time for this!’

‘You have plenty, missy, you’re not going anywhere in the night.’ He will reel out this tale at his own pace and I have no choice but to listen.

I’m old enough to know that secrets don’t spill quickly, they bleed, they seep.

‘When I was a boy, I was adopted by a very bad man. I was brought up by brigands but left to my own devices an awful lot. Often I’d sneak away to another part of the woods and watch a family who made their home there. Mother, father and a daughter, they were happy and loving. I’d watch all three, unseen. I was very careful never to let my foster-father or any of his men know. That family was my secret—I kept it to keep them safe.

‘I made friends with the little girl. I was treated so very well in their home. The first tenderness I ever experienced came from them. I wanted nothing in life but to be loved, to belong to that family. I would lie on my bed of bracken at night and dream of four walls and a hearth, of the sounds of people who loved me sleeping nearby.’

‘Faideau.’ I itch to shake him, to stop him, but he ignores me. I have enough shadows of my own; I do not wish to carry those of another.

‘Your mother, even then, was as beautiful as a new day. Then the baby arrived and I was displaced. The mother was preoccupied and Theodora wanted only to play with the new human doll. I interested her not at all. Perhaps if I’d been older I would have known that things would return to normal if only I’d the patience to wait. That their love hadn’t gone, merely been distracted.’ He frowns as if he could tell his younger self these things and thus avoid all that had come about.

‘In the woods, Magdalene, there are wolves, trolls, men who turn into beasts at the first sign of the moon, women who do worse. All in all, witches are the least of your worries. Things in the forest speak, things that shouldn’t, and they know what’s in your heart. A troll-wife found me hiding, watching Theodora and her mother and new sister at the stream.’

My heart clenches. His confession will hurt us both. ‘It—she—told me I could win their love if only I did her a favour. It was a joke she said, no one would get hurt—that sometimes we needed to use tricks to get what we really, really wanted.’

And he told me how he stole away the true Polly lying fresh in her basket, and took her to the doors of the kingdom under the mountain. How the troll-wife gave him another child in return, a misshapen lump of flesh, a wailing thing that she touched and moulded until it took on the appearance of the infant he had brought. How he returned it to where Theodora’s mother might find it and his head was filled with thoughts of how much this family would love him. But the guilt ate at him, night and day, so any joy he might have had was bitter. He was uncomfortable and afraid that somehow he might be discovered. That the mewling changeling might somehow betray him. His fear transmitted itself to the family and so they became ill at ease in his presence. After a while he stopped going to visit.

I could have told him, even I, that such an act will return a greater pain to the perpetrator than the victim, how selfishness is never rewarded. How, when I had screamed at my mother and wished her gone, the very next day she was. And how on the morning I found her missing I could not imagine a worse ache than that of the loss of her.

‘How could she not know you, Faideau? To meet you again?’

He shrugs. ‘When she came to Lodellan as the prince’s bride, all royal and shiny, there were so many years between us and I wore another name, once, when I was small. And I was so much less than I had been. The boy had faded from her memory; the man was a drunk. And so this,’ he gestures as if a shared history is spread before us rather than the components of a meal, ‘is all my fault.’

‘But you were only a child,’ I say. He smiles coldly.

‘Someone else said that to me once, or something very like.’ He shakes his head.

How do I judge this man? How dare I judge him? Had he been stronger, had he been better, Theodora may not have married my father and we would not have been as we were. My aunt would never have been stolen away; we would not have fled the city; we would not have had this vein of agony running through our lives. I would have had a different father; or I would not have existed at all. I do not find that last thought painful.

‘So, I ask again, Magdalene, why did your mother leave you?’ But I do not say anything, do not give him even a scrap and he hands me a plate. ‘I think you should leave very early. I don’t want to see you again.’

I almost open my mouth then, but he continues, reluctantly, as if he now gives me information against his will. ‘Your mother is known, Magdalene, in the forest. She travelled its ways long before she came to Lodellan. She knows its dangers. Be careful. Don’t stray from the path.’

***

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Cliff McNish

Cliff McNish, acclaimed as ‘one of our most talented thriller writers’ (The Times), has written numerous award-winning fantasy, SF, horror and supernatural novels for children and young adults. His initial fantasy series, The Doomspell Trilogy, was published in 26 languages worldwide. His 2006 ghost story Breathe was voted in May 2013 as one of the top 100 adult and children’s novels of all time by the Schools Network of British Librarians.

What inspired your story “Who Will Stop Me Now”?

I’ve always pitied Medusa. Perseus is such a sanctimonious ass. He’s given every advantage, the gifts the gods supply him lay Medusa’s death pathetically easily in his lap, and yet he’s remembered … as the HERO. Uh-uh. Don’t like that. And I just enjoyed the idea of a girl totally embracing terror’s destination. Exulting in chaos.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

An SF story I read when I was about 12. What appeared to be a boy walking with his father through an exhibition of aliens at a zoo. The last ‘creature’ turned out, of course, to be a real human boy – the last of his kind. Such an obvious switch, but as a kid I had no idea it was coming and was totally devastated. I’ve never been able to find out who wrote it.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Impossible. But I’ll name three I love: Steve Rasnic Tem, Melvin Burgess (not heard of him? He writes YA fiction, and his Bloodtide is one of the most impressive slices of pure horror I’ve ever read). Oh, and I’ve loved more than one Graham Masterton. His best passages are insanely good.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

“Who Will Stop Me Now” is actually my very FIRST pure adult horror story. (We’ll, I have written one more, but it’s in my drawer.) I’ve written an adult comedy-horror film script, though, and an adult ghost script.

My 14 published novels so far are for 9-12 year olds and YA, but to be honest they are (mostly) full of horror. My novel Savannah Grey is about a girl who has a weapon in her throat, and is stalked by three monsters. It’s outright horror. As (with a supernatural slant) are my YA ghost novels Breathe and The Hunting Ground. I do occasionally write nicer animals stories, though. It’s nice to pretend you have a gentling aspect.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

I’m just about to start China Miéville’s short story collection Three Moments of an Explosion. His Perdido Street Station is often classed as ‘fantasy’ but is probably the most extendedly beautiful and accomplished horror novel I’ve ever read.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 30, 2015

The Clowns on the Balcony

So, every afternoon around 3.30 I hear sounds out on the balcony, the scrape and scratch of large claws grabbing onto the metal railing. No, it’s not a monstrous attack, it’s these guys, the resident clowns. I generally go out, say hello, tell them they’re purdy, then go back to work. And they seem happy with that.

But some days I’m caught up in what I’m doing and I don’t go out. I don’t acknowledge them. That’s when crap happens.

Yesterday was one of those days. I didn’t go out and then I heard a strange noise, a crunching vegetable’ish sound. So, I went onto the balcony to find that one of my beautiful orchids (which you can see in the bottom of the above photo) was someone’s late lunch. I spent some time yelling obscenities, and of course taking actions shots. Assholes. These birds are assholes. But cute.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Paul Meloy

Paul Meloy was born in 1966. He is the author of Islington Crocodiles, Dogs With Their Eyes Shut, The Night Clock and a forthcoming collection called Electric Breakfast. He is working on his second novel, a sequel to The Night Clock. He lives in Devon with his family.

What inspired your story “Joe is a Barber”?

A haircut. I was working in Bury St Edmunds and went for a trim in a small basement barbershop off the high street. Smart young men in waistcoats and ties worked silently while their boss patrolled behind them checking their work. It was quite tense. And I’m always struck by how intimate a haircut is, how vulnerable you are in that chair, and the story came to me on the drive back to work in a complete narrative consisting of single lines.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

Probably The Interlopers by Ramsey Campbell, although it was so long ago I should probably cite the impact the whole book (Demons by Daylight) had on me. It was a cumulative effect of reading something so surreal and unsettling that I instantly knew I had discovered a depth to something I hadn’t known existed. Proper scary! Still wonderfully confusing!

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Adam Nevill

Stephen King

Justin Cronin

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

Graham Joyce defined my stuff as ‘fractured realism’, which will do for me. I tend to strive for a sense of awe, or wonder, rather than outright fear, although fear is certainly a part of the mix. I suppose it’s more magic realism, or dark fantasy with elements of horror.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

Sacrifice by Paul Finch, The Stormwatcher by Graham Joyce, Houses without Doors by Pete Straub and Song of Shadows by John Connolly.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 29, 2015

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Simon Bestwick

Having fled a life of soul-killing jobs (office worker, fast food operative, WP operator, training administrator, call centre worker), the very talented Mr Simon Bestwick is now spending his days doing what he loves: writing. Which is a fortunate thing for us all. He’s published two novels, a chapbook, and three short story collections, and now takes some time out to discuss his story from The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories.

Having fled a life of soul-killing jobs (office worker, fast food operative, WP operator, training administrator, call centre worker), the very talented Mr Simon Bestwick is now spending his days doing what he loves: writing. Which is a fortunate thing for us all. He’s published two novels, a chapbook, and three short story collections, and now takes some time out to discuss his story from The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories.

What inspired your story “Horn of the Hunter”?

I could be glib and say ‘the present government here in the UK’… but would actually also be partly true. I’d had the basic premise of the story in my mind for some time, but hadn’t been able to decide what the ‘Big Bad’ in it would be: first it was genetic mutants, then later a pack of hellhounds, but none of them seemed right. And then a couple of months ago, we had an election, and the Conservative Party got back in. As some non-UK readers might not know – but British readers will know all too well – their attitude towards anyone claiming welfare or state support, anyone poor or vulnerable, is one of depraved indifference at best, and outright sadism at worst. And just to put the tin lid on it, having got back into power, they announced they wanted to legalise fox-hunting – hunting animals with dogs for sport – which was banned some years ago. For me, that just sums these [TRIES TO FIND NON-OBSCENE WORD; FAILS] up for me… anyway, things came together very neatly after that.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

‘The Masque Of The Red Death’ by Edgar Allan Poe. I was very lucky when I was a small boy, because my Grandpa owned this big thick book called ‘A Century Of Thrillers’, which was a compendium of great horror stories. There was stuff by Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, Poe – no Lovecraft or M.R. James, though, oddly enough; I didn’t encounter them till some years later. Wilkie Collins, Sheridan Le Fanu, and some stories by lesser known writers – there was one called ‘The Lighthouse On Shivering Sands’ by J.S. Fletcher… but ‘The Masque Of The Red Death’ was the one that actually, genuinely frightened me. There’s the setting, the castle, the devastation outside, there’s the incredibly gruesome idea of the Red Death itself (to a small boy, of course, anything gory is awesome.) And then there’s that ending, and most of all that last line: And darkness and decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all. That line is The end of everything. There is no escape. It was as if the horror in the story had actually reached out from the page and touched me. It was scary, not in a sense of creepiness or pleasing terror, but in the sense of a picture of a world in which you and everything and everyone you love are annihilated.

Other stories: ‘The Pond’ by Nigel Kneale, ‘The Extra Passenger’ and ‘The Lonesome Place’ by August Derleth – the last one has the truly fascinating idea of a creature that’s shaped out of fear itself – ‘The Boorees’ by Dorothy K. Haynes, about these creature that live up a chimney… I’d better stop or I’ll be here all day.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

This is a tough one, because I’m really bad at lists – I always want to include more authors. Ramsey Campbell, because I don’t think anyone’s done as much to promote the idea of horror as a form of literature, and who’s consistently produced so much stuff of such a high standard in the field.

Next: Ray Bradbury. Some would say he’s science fiction, not horror, but for them I have three words: The October Country. Bradbury was a genius – ‘The Scythe’, ‘The Next In Line’, so many others…

Finally, Richard Matheson: Shock 3 blew me away – like Bradbury, he’s one of those writers who overlaps between horror and science fiction. That’s a provisional list, and if you ask me tomorrow I’ll have some completely different names.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

More and more at the moment, and there are a lot of reasons for that. I think horror’s a genre that kind of exists at the crossroads. It’s at this place where fantasy, science fiction and crime fiction – and most other genres, really – overlap, and you can take what you need from the others. And some of the best work happens at that overlap.

There’s a story I wrote a couple of years ago called ‘Lex Draconis’, which is in an anthology called Tales of the Nun and Dragon. You had to write a story involving either a nun or a dragon, so I decided to put both in, and somewhere along the line the phrase ‘nun-on-dragon action’ popped into my head and that story happened. It’s not something that would ever have happened if not for that anthology, but I absolutely love the result. It’s sort of fantasy, and it’s funny and odd and kind of a love story, and nothing like anything else I’ve done. At some point I’d love to write more in that sort of vein. So if anyone wants to buy a copy of that anthology… hint, hint.

There’s a novel coming out next year – inshallah! I can’t say anything else till the contracts are signed – that’s a mixture of horror, thriller and post-apocalyptic SF. I’ve also just finished a crime novel, but whether anything comes out of that remains to be seen.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

A hell of a lot. There’s loads of books I’ve bought and not read – we’ve just moved house, so a lot of them are still packed away – and then there’s the stuff on the Kindle. Right now I’m just starting on John Connolly’s The Book of Lost Things, and I’ve also got two novellas, Albion Fay by Mark Morris and Leytonstone by Stephen Volk, to hand. Also, there’s a copy of this book bought alongside them, called The Bureau Of Them by Cate Gardner – but I’ve already read that (perk of the job) and it’s brilliant. You should all read it.

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 28, 2015

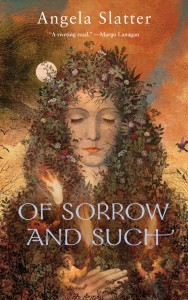

Of Sorrow and Such available for pre-order!

All of the undignified happy dancing this morning: my Tor.com novella, Of Sorrow and Such, is available for pre-order.

All of the undignified happy dancing this morning: my Tor.com novella, Of Sorrow and Such, is available for pre-order.

If you feel so moved, go here – but please note that only Amazon and Barnes and Noble currently have the pre-order thing going on.

Set in the Sourdough world, it follows Patience Gideon (Sykes that was for fans of Sourdough and Other Stories) in another adventure.

Margo Lanagan said: “Of Sorrow and Such takes you to dark, unsettling places. Angela Slatter’s magic is earthy, bodily and beleaguered; in the hands of tough, clever Patience Gideon it’s a powerful instrument for wresting justice from a hostile world. A riveting read.”

Juliet Marillier said: “Of Sorrow and Such is Angela Slatter at her best. Characters and settings spring fully alive from the page, and the storytelling provides rich nourishment for both intellect and spirit.”

And I didn’t even pay them!

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Gary Fry

Gary Fry lives in Dracula’s Whitby, literally around the corner from where Bram Stoker was staying when he was thinking about that character. Gary has a PhD in psychology, but his first love is literature. He is the author of many short story collections, novellas and novels. He was the first author in PS Publishing’s Showcase series, and none other than Ramsey Campbell has described him as “a master.” Gary warmly welcomes all to his web presence: www.gary-fry.com

Gary Fry lives in Dracula’s Whitby, literally around the corner from where Bram Stoker was staying when he was thinking about that character. Gary has a PhD in psychology, but his first love is literature. He is the author of many short story collections, novellas and novels. He was the first author in PS Publishing’s Showcase series, and none other than Ramsey Campbell has described him as “a master.” Gary warmly welcomes all to his web presence: www.gary-fry.com

What inspired your story “Scraping By”?

I find the economy and how global problems are translating into local difficulties really fascinating. It maps on to interests I had as a student, trying to figure how the individual related to society (and vice versa). The credit crunch was a bit like a fiscal earthquake, like a slippage in the structure of the social world. The tsunami of austerity which arose caught so many folk sitting out on beaches, some nonchalantly in hammocks, others sipping self-satisfied drinks, etc. And so in this story I wanted to capture that feeling of a couple’s lives in motion, and how they were suddenly swept sideways by events outside their control, and how little they could do to deal with that. Scraping By is, I hope, about the way private and public tragedy intersect.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

I’d say it was Roald Dahl’s ‘Man From the South’. It’s a perfect one-note horror story, whose terrors are located firmly offstage. I like that sense of elusive (and allusive) terror. It appealed to me powerfully as a kid, and just as much as an adult. One unusual aspect of it is, I think, the way that, unlike many horror tales which leave the reader just before some terrible event occurs (indeed, the story’s structure promises that all along), the terrible events in that tale have already occurred. If you know the piece, you’ll know what I mean. The whole tale is like a great melody: simple and resonant. Believe me, that’s hard to achieve.

Name your three favourite horror writers.

Ramsey Campbell. Stephen King. H P Lovecraft. I think those have had the most influence on me, and in that order. However, there are significant honourable mentions to Robert Aickman, M R James, Algernon Blackwood, TED Klein and Michael McDowell. I’d also include the scariest writer not described as a horror writer: Ruth Rendell (and her twisted sister Barbara Vine).

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

Almost entirely horror. I do occasionally touch upon scifi concepts, but usually within the Lovecraftian framework of alien beings summoned to earth. I don’t read much scifi or fantasy — Lord, I’ve tried, but it’s not for me, alas — and so tend to stick to what I know. My fictional preferences are very much grounded in the minutiae of everyday life, like a kitchen-sink drama with ghouls. I don’t why all that appeals to me; my north of England upbringing probably bears the guilt.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

Oh, plenty. With a little time free right now, I’m indulging in all the books I never quite got round to as a younger man. I’ve devoured with peerless pleasure the likes of Roth’s American trilogy, Ellison’s Invisible Man, the less famous Greene novels, rereads of my beloved Martin Amis, and also Atwood, Updike, Faulks (a new discovery and a welcome one!), Murakami, et al. Going forwards, I hope to try a number of other writers who’ve always been on my radar: A S Byatt is there, as are Johns Cheever and Irving, along with Hilary Mantel and many more. Every so often I intersperse such weighty stuff with a bit of comic relief like Tom Sharpe. The number of books I’d like to read staggers and dismays me, but then I look at it another way: I have all these great books to read!

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.

July 27, 2015

The Sourdough Posts: Lavender and Lychgates

Arthur Rackham, Girl Beside a Stream

Oh noes! Second last Sourdough story! Soon it will all be over.

With “Lavender and Lychgates” I wanted to draw some threads together: I wanted to see Emmeline and Peregrine from “Sourdough” in their later life together – I wanted to know they were happy. I wanted to add another dimension to Emmeline’s mother, and I realised she was one of the twins from “The Angel Wood”, all grown up and with a family and personality of her own. I wanted to continue the idea of the importance of books in this collection, and of Lodellan as a place where books were born – that, in addition to its degenerate places, it also produced some wonderful things. Sidenote: the Carabhilles who own one of the bookstores in Lodellan have gone on to appear in The Bitterwood Bible and the new novella I’m working on, The Witch’s Scale.

I wanted to continue to explore concepts about the consequences of Emmeline’s actions in “Sourdough”. I had an image in my head of a young girl playing in a graveyard, which managed to entwine itself with a garbled tale of lilacs and lychgates a friend had told me years ago, the precise details of which I cannot remember. I managed to garbled it even more, replacing lilacs with lavender. I couldn’t get the words ‘lavender and lychgates’ out of my head, nor the image of shadows swirling in the apex of a lychgate roof above the heads of people passing out underneath. Emmeline ends “Sourdough” with the words ‘My memory is true’, and I wondered what happens when you hang onto a recollection too tightly.

This story was chosen by Stephen Jones for The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror 22.

Lavender and Lychgates [extract]

My mother’s hair catches the last rays of the afternoon sun and burns. My own is darker, like my father’s, but in some lights you can see echoes of Emmeline’s bright fire buried deep.

She leans over the grave, brushing leaves, dirt and other wind-blown detritus away from the grey granite slab. A rosebush has been trained over the stone cross, and its white blooms are still tightly curled, with just the edges of the petals beginning to unfurl. Thomas Austen has rested here for fifteen years. Today would have been my brother’s birthday

To our right is one wall of the Cathedral, its length interrupted by impressive stained-glass windows that filter light and drop colours onto the worshippers within. My father, Grandma Tildy and my twin brothers, Henry and Jacoby, are among them, listening to the intoning of the mass. I can hear the service and the hymns as a kind of murmur through the thick stones. Emmeline has refused to set foot in there since Thomas’s untimely demise. I used to attend, too, but only until I was three or so, when I made plain my preference for my mother’s company over one of the hard-cushioned pews. Peregrine gave up arguing about it long ago, so I’ve been perched on the edge of Micah Bartleby’s tomb, weaving a wreath. I braid in lengths of lavender to add colour. I put the finished item beside my mother and tap her on the shoulder to draw her attention.

‘Thank you, sweetheart,’ she says, voice musical. Her face is smooth and her skin pale; only the flame-shaped streak of white at her widow’s peak shows that she’s older than you might think. Her figure remains trim and she still catches my father’s eye. ‘Don’t go too far, Rosie.’

She says this every time even though she knows the graveyard is my playground. When I was smaller, Emmeline would not let me wander on my own. She knew – knows – that things waited in the shadows, bright-eyed and hungry-souled. Now I am older she worries less for I’m aware of the dangers. Besides, the dark residents here want only to steal little children – they are easier to carry away, sweeter to the taste. She believes I am safe. I drop a kiss on the top of her head, feel how warm the sun has made her hair. She smells of strawberries.

I take my usual route, starting at Hepsibah Ballantyne, ages dead and her weeping angel tilted so far that it looks drunk and about to fall over. Under my carefully laced boots crunch the pieces of quartz making up the paths, so white it looks like a twisted spine. Beneath are miles and miles of catacombs, spreading out far beyond the aboveground boundaries of the graveyard. This city is built upon bones.

The cemetery devours three sides of Lodellan Cathedral, only the front entrance is free, its portico facing as it does the major city square. High stone walls run around the perimeter of the churchyard, various randomly located gates offer ingress and egress. The main entrance is a wooden lychgate, which acts as the threshold to the home of those-who-went-before.

No rolling acres of peaceful grass for our dead, but instead a labyrinth, a riotous mix of flora and stone, life and death. There are trees, mainly yew, some oak, lots of thick bushes and shrubs making this place a hide-and-seek haven. It’s quite hard, in parts, to see more than a few feet in front of you. You never know if the path will run out or lead over a patch of ground that looks deceptively firm, but is in fact as soft and friable as a snowdrift. You may find yourself knee-deep in crumbling dirt, your ankles caught in an ancient ribcage or, worse, twenty feet down with no one to haul you back into the air and light.

I am safe from these dangers at least, for I recognise the signs, the way the unreliable earth seems to breathe, just barely.

You might think perhaps that becoming dust would level all citizens, make social competitions null and void, but no. Even here folk vie for status. Inside the Cathedral, in the walls and under the floor, is where our royalty rests – the finest location to wait out the living until the last trumpet sounds. Where my mother sits is the territory of the merchant classes, those able to afford a better kind of headstone and a fully weighted slab to cover the spots where the dearly departed repose.

Further on, the poorer folk have simple graves with tiny white wooden crosses that wind and rain and time will decimate. Occasionally there is nothing more than a large rock to mark that someone lies beneath. In some places sets of small copper bells are hung from overhanging branches – their tinkling plaint seems to sing ‘remember me, remember me’.

Over by the northern wall, in the eastern corner, there are the pits into which the destitute and lost are piled and no one can recognise one body from another. These three excavations are used like fields: two lie fallow while one is planted for a period of two years. Lodellan does not want her dead restless, so over the unused depressions lavender is grown, a sea of purple amongst the varying greens, browns and greys. These plants are meant to cleanse spirits and keep the evil eye at bay, but rumour suggests they are woefully inadequate to the task.

In the western corner are the tombs proper, made from marble rather than granite, these great mausoleums rise over the important (but not royal) dead. Prime ministers and other essential political figures; beloved mistresses sorely missed by rich men; those self-same rich men in neighbouring sepulchres, mouldering beside their ill-contented wives, bones mingling in a way they never had whilst they breathed; parvenus whose wealth opened doors that would otherwise have remained firmly shut; and families of fine and old name, whose resting places reflected their status in life.

My father’s family has one of the largest and most elaborate of these, but he is banned from resting there – as are we. Even after all the scandal with his first wife and the kerfuffle when he set up sinful house with my mother, Peregrine had his own money. His parents saw no point, therefore, in depriving him of an inheritance and left him their considerable fortunes when they died. What they did refuse him was the right to be buried with them. They seemed to think this would upset him most, which caused Peregrine to comment on more than one occasion that it was proof they really had no idea at all.

Once upon a time I liked to play with my dolls in the covered porch that fronts the Austen mausoleum, imagining these grandparents I’d never met. But now I’m older, I don’t trouble with dolls anymore, nor do I concern myself with grands who didn’t care enough to see me when they lived. I feel myself poised for I know not what; that I stand on a brink. Grandma Tildy tells me this is natural for my age. So I simply wait, impatiently. I walk up the mould-streaked white marble steps and sit, staring into the tangled green of the cemetery.

Across the way a veil of jasmine hangs from a low yew branch, and something else besides. Something shining and shivering in the breeze: a necklace. I leave my spot and move closer to examine it without touching. There’s little finesse in its making, the blue stones with which it is set are roughly cut and older than old. The whole thing looks pretty, but raw. I know not to take it. Corpse-wights set traps for the unwary. There are things here the wise do not touch. Should you find something, a toy, a stray gift that seems lost, do not pick it up thinking to return to it for chances are its owner is already contemplating you from the shadows. There are fetishes, too, made of twigs and flowers, which catch the eye, but nettles folded within will bite. Even the lovely copper bells may be a trick, for many’s the time no one will admit to hanging them.

Across the way a veil of jasmine hangs from a low yew branch, and something else besides. Something shining and shivering in the breeze: a necklace. I leave my spot and move closer to examine it without touching. There’s little finesse in its making, the blue stones with which it is set are roughly cut and older than old. The whole thing looks pretty, but raw. I know not to take it. Corpse-wights set traps for the unwary. There are things here the wise do not touch. Should you find something, a toy, a stray gift that seems lost, do not pick it up thinking to return to it for chances are its owner is already contemplating you from the shadows. There are fetishes, too, made of twigs and flowers, which catch the eye, but nettles folded within will bite. Even the lovely copper bells may be a trick, for many’s the time no one will admit to hanging them.

There’s a rustle in the boughs above me and I see a face, wrinkled and sallow, with yellowed buck teeth, the brightest green eyes and hair that is, in the very few parts that are not white, as fiery as Emmeline’s. The creature seems a “not-quite” – part human, part something else. Troll? My heart stops for a few beats as I stare up at the funny little visage; its gnarled hands hold the leaves back so it may peer at me clearly. Then it tries a smile, a shy strangely lovely expression, which I cannot help but return. I do not think this being is associated with the shiny temptation on the branch below it.

‘Rosie! Rosamund!’ My mother’s shout reaches me. I back away and race through the bone orchard, my feet sure.

Emmeline is standing, stretching her arms up to the sky. In her hand is her sun bonnet, which she wears less than she should, its ribbons fluttering. She smiles to see me. ‘Afternoon service will be finished soon.’

I’m almost there when my foot catches on a tree root I could swear was not in existence a moment before and I fall towards my brother’s grave. My hands hit the rough-polished granite and while one stays put, merely jarring the wrist, the right one skids across the surface, catching on the letters of his name. I feel the skin peel from my palm and let out a squeal of shock and pain. A slew of hide and a scarlet stain mar the stone. The ring my mother gave me, silver vines and flowers all entwined, is embedded into the flesh of my finger and I think I feel it grind against bone. I knock my knees against the sharp edge of the slab, too, ensuring impressive bruises in spite of the padding of my petticoats and skirt.

I may be almost an adult, but for all that I wail like a child while Emmeline fusses about with her lacy handkerchief.

‘Oh, oh, oh, my girl! Come along home, we’ll get those seen too. Your grandma will have something we can put on that.’ She helps me up and dabs at the seeping blood while I howl. My abused flesh stings and burns as we pass out under the lychgate. Shadows crowd above us in the angles of its ornate roof.

As we hobble away, I remember that I forgot to whisper good wishes to my brother.

***

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories: Ray Cluley

Ray Cluley’s short stories have been published in various magazines and anthologies. He has appeared in a few ‘best of’ anthologies and a couple of his stories have been translated (into French and Polish). He won the British Fantasy Award for Best Short Story with ‘Shark! Shark!’ in 2013. Water For Drowning, from This Is Horror, is currently short listed for a British Fantasy Award for Best Novella. His most recent work includes Within the Wind, Beneath the Snow, from Spectral Press, and Bone Dry (aka Curse of the Zombie) from Hersham Horror, while his collection Probably Monsters is available now from ChiZine.

What inspired your story “Mary, Mary”?

“Mary, Mary” began life as a simple story about a somewhat taboo subject (even in the horror genre) and was inspired by my own reaction to how the subject is so often presented in fiction and the media. If that sounds a bit vague, it’s because I’m trying to avoid major spoilers. The story developed when I was asked to write for an anthology I’ve since had to withdraw from, mainly because “Mary, Mary” refused to be nurtured into a story it didn’t want to be. Thankfully the publisher was very understanding about that and I was able to prune the story back and let it grow into what it is now, which in the long run has turned out very well because now it gets a more suitable home in The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories.

What’s the first horror story you can remember making a big impact on you?

I’ve just been drafting a blog on this very subject! It wasn’t something I read, actually, but rather something I heard – the Jeff Wayne version of The War of the Worlds. It’s often considered sci-fi but for me it’s firmly a horror story and it terrified me as a kid, but in a good way (which was a weird feeling to get your head around as a child – like crying on a roller coaster then demanding “Again! Again!” afterwards.) Thirty odd years later it remains one of my favourites. I was too young to fully grasp the story, probably, but a sense of fear and panic permeates that album, thanks to Richard Burton’s wonderful narration and that evocative music – the heartbeat, the drilling electronic blasts, that drawn out Martian cry of Ulla! I used to imagine Martians skulking outside at night and knew it was only a matter of time before one of them peered in a window…

Name your three favourite horror writers.

I have so many, but to focus on newer writers I’d say Nathan Ballingrud, Helen Marshall, and Lisa Hannett. I’m excited whenever I hear one of them has new work coming and hope they never stop writing.

Is your writing generally firmly in the horror arena or do you do occasional jaunts into other areas of speculative fiction?

Oh, I do like a jaunt! Wherever I go, though, tends to end up being a suburb of horror. So the darker side of science fiction or fantasy, usually. I enjoy the crime genre, too, but it has to rise above puzzle-solving or serial killers. I think horror, any genre actually, benefits from a bit of overlap with another genre, it can help a story avoid becoming mired in tropes and clichés. Horror will always be my favourite genre, though. I feel we learn more about ourselves by looking at what scares or disturbs us.

What’s in your to-be-read pile at the moment?

Ha! What isn’t?! But the ones nearest the top, that I’m most looking forward to, are Stephen Volk’s Leytonstone, M.R. Carey’s The Girl With All The Gifts, and the latest issue of Interzone. I can’t wait to add The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories to that pile…

The 2nd Spectral Book of Horror Stories can be pre-ordered here.